This meta-analysis reviews placebo-controlled phase 2 and 3 studies of 10 antiseizure medications approved since 2008 to evaluate the risk of suicidality of these drugs compared with placebo.

Key Points

Question

Does evidence support the US Food and Drug Administration class warning of increased risk of suicidality for antiseizure medications approved since 2008?

Findings

In this meta-analysis of phase 2 and 3 randomized placebo-controlled epilepsy trials of antiseizure medications approved since 2008, suicidality was evaluated prospectively in trials of 5 antiseizure medications (eslicarbazepine, perampanel, brivaracetam, cannabidiol, and cenobamate), including 17 trials involving 5996 patients, including 4000 patients treated with antiseizure medications and 1996 treated with placebo. There was no evidence of increased risk of suicidality (ideation or behavior) overall or for any individual drug.

Meaning

There is no current evidence that newer antiseizure medications increase suicidality in epilepsy; therefore, a suicidality class warning is not warranted.

Abstract

Importance

Most antiseizure medications (ASMs) carry a US Food and Drug Administration–mandated class label warning of increased suicidality risk, based on a meta-analysis comparing suicidality between individuals treated with medications vs placebo in randomized clinical trials done before 2008. ASMs approved since then carry this warning although they were not similarly studied.

Objective

To review all placebo-controlled phase 2 and 3 studies of 10 ASMs approved since 2008 to evaluate the risk of suicidality of these drugs compared with placebo.

Data Sources

Primary publications and secondary safety analyses in PubMed of all phase 2 and 3 randomized placebo-controlled epilepsy trials of ASMs approved since 2008, using keywords epilepsy, antiepileptic drugs, seizures, suicidality, suicidal ideation, and the names of individual drugs.

Study Selection

All phase 2 and 3 randomized clinical trials of adjunctive treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy and their secondary safety analyses.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Articles were reviewed for frequency of suicidality (ideation, attempts, and completed suicides). Mode of suicidality ascertainment included treatment-emergent adverse event reports, Standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities queries for events in prespecified categories including suicidal ideation and behavior, prospective collection of suicidality data as a prespecified safety outcome using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, and retrospective evaluation by blinded review using the Columbia-Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment. A meta-analysis compared risk for drugs vs placebo of each outcome for all drugs overall and by individual drugs and trials.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Suicidality (total and by ideation), attempts, and completed suicides.

Results

Excluding studies that did not evaluate suicidality (everolimus and fenfluramine) or did not evaluate it prospectively (lacosamide, ezogabine, and clobazam), 5 drugs were analyzed: eslicarbazepine, perampanel, brivaracetam, cannabidiol, and cenobamate. Suicidality was evaluated in 17 randomized clinical trials of these drugs, involving 5996 patients, of whom 4000 patients were treated with ASMs and 1996 with placebo. There was no evidence of increased risk of suicidal ideation (drugs vs placebo overall risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.35-1.60) or attempt (risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.30-1.87) overall or for any individual drug. Suicidal ideation occurred in 12 of 4000 patients treated with ASMs (0.30%) vs 7 of 1996 patients treated with placebo (0.35%) (P = .74). Three patients treated with ASMs and no patients treated with placebo attempted suicide (P = .22). There were no completed suicides.

Conclusions and Relevance

There is no current evidence that the 5 ASMs evaluated in this study increase suicidality in epilepsy and merit a suicidality class warning.

Introduction

In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert that antiseizure medications (ASMs) increase suicidality based on a meta-analysis of 199 randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials including 11 ASMs: carbamazepine, felbamate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, pregabalin, tiagabine, topiramate, valproate, and zonisamide. Among 43 892 patients treated for epilepsy (31% of trials), psychiatric diseases (28%), and other diseases (mainly pain, 41%), suicidality was increased 1.80 fold with ASMs compared with placebo.1 Suicidality occurred in 4.3 of 1000 patients treated with ASMs compared with 2.2 per 1000 patients treated with placebo, with a risk difference of 2.1 per 1000. Among patients with epilepsy, suicidality rates were 3.4 of 1000 with ASM treatment vs 1 of 1000 with placebo.1 All 4 completed suicides were in the active treatment arms: 2 patients with epilepsy and 2 psychiatric patients. The FDA advisory board concluded that all ASMs “pose an increased risk of suicidality (defined as suicidal ideation and behavior), and prescriptions should be accompanied by a patient medication guide describing this risk.”2 Subsequently approved ASMs were required to have a warning for suicidality.

The FDA recommendations have greatly influenced prescribing and development of new ASMs, with suicidality prominently listed among ASM-related adverse events. The mandated suicidality warning may affect patients’ willingness to take ASMs, potentially reducing adherence, a major driver of seizure recurrence, which is associated with increased risk of injury and death. It has also affected ASM investigational trial designs.

The recommendations were subject to methodological limitations, including (1) heterogeneously and retrospectively collected suicidality data, with no standardized suicidality definition; (2) post hoc analyses without prespecified outcome measures; (3) grouping all ASMs together although their risks varied, including statistically nonsignificant increase for 7 of 11 and decrease for 2 of 11 medications; (4) combining monotherapy and adjunctive trials and (5) trials of different disease indications with different suicidality risks; and (6) not accounting for baseline suicidality risk, which may vary between studies, diseases, and medications.3

Patients with epilepsy have increased depression and suicidality compared with the general population, especially in patients with uncontrolled seizures.4,5,6 The warnings suggest additional risk attributable to the treatment itself. Since 2008, 10 new-molecule ASMs have been approved by the FDA: lacosamide, (2010), retigabine/ezogabine (2011), clobazam (2011), perampanel (2012), eslicarbazepine (2013), brivaracetam (2016), everolimus (2016), cannabidiol/Epidiolex (Greenwich Biosciences; 2018), cenobamate (2019), and fenfluramine (2020). Stiripentol’s 2018 approval was based on earlier European data. In addition, midazolam and diazepam were approved in new formulations (intranasal Nayzilam [UCB] and Valtoco [Neurelis]). The FDA mandated warnings of suicidality for all but 1 of the new drugs, although none were part of the 2008 study. The suicidality warning tops the warnings and precautions section of prescribing information for lacosamide, perampanel, eslicarbazepine, and brivaracetam, although no evidence supports it.

Pivotal ASM epilepsy trials since 2008 have evaluated suicidality prospectively, and, since 2011, have included the validated Columbia Suicidality Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).7 Here, we review all randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 and 3 studies of new ASMs to compare suicidality rates between patients treated with ASMs vs with placebo to determine whether these agents are associated with increased risk for suicidality. We have confined the analysis to epilepsy studies to avoid potential confounders such as possible differences in suicidality risks between different diseases.

Methods

We reviewed publications in PubMed of all phase 2 and 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled adjunctive treatment studies in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy for ASMs approved since 2008, using epilepsy, antiepileptic drugs, seizures, suicidality, suicidal ideation, and the names of individual drugs as keywords. Primary articles were reviewed for frequency of suicidality: total and divided into suicidal ideation, attempts, and completed suicides. Studies were evaluated for mode of suicidality ascertainment, categorized as reporting treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE), using Standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities queries for classification of events in prespecified categories including suicidal ideation and behavior, prospective collection of suicidality data as a prespecified safety outcome using validated suicidality questionnaires such as the C-SSRS, and retrospective evaluation by blinded review using the Columbia-Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment. We included all studies that evaluated suicidality with any of these modalities. We also reviewed all secondary articles of safety evaluation of the pivotal studies. The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.

A formal meta-analysis was performed using published clinical trial results of ASMs approved by the FDA since 2008. The meta procedure in Stata version 16 (StataCorp) produced forest plots summarizing results overall and by study drug comparing risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide death for study drug vs placebo. Analysis used random effects–restricted maximum likelihood models and included a test of evidence of heterogeneity of results overall and by study drug and included tests of evidence of publication bias. Results are presented as relative risks (ASM/placebo) of each outcome overall, by ASM and by trial. Statistical analysis also included χ2 comparison between patients treated with ASMs and placebo. Two-sided P values were statistically significant at less than .05.

Results

Of the 10 new-molecule ASMs approved by the FDA since 2008, 2 completed all pivotal phase 2-3 studies before or in 2008 (lacosamide8,9,10 and ezogabine11,12,13) and 1 completed the studies by 2008 or shortly after (clobazam14,15). Studies of these 3 ASMs did not assess suicidality prospectively. Therefore, they were omitted from our analysis (eFigure in the Supplement). Of the 7 remaining ASMs, 2 (everolimus and fenfluramine16,17) did not evaluate suicidality in their pivotal studies and were also excluded. Therefore, 5 ASMs were included in the analysis: eslicarbazepine, perampanel, brivaracetam, cannabidiol, and cenobamate. These 5 ASMs were evaluated in 19 studies: 16 pivotal phase 2 or 3 studies,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 2 nonpivotal phase 2 studies,34,35 and 1 nonpivotal phase 3 study.36

There were 3 eslicarbazepine, 4 perampanel, 6 brivaracetam, 4 cannabidiol, and 2 cenobamate studies.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 Two of the cannabidiol studies did not include information on suicidality and were omitted from the analysis,29,31 leaving 17 studies. Two phase 3 placebo-controlled studies, 1 each for eslicarbazepine19 and for brivaracetam,36 did not include suicidality data in the primary articles. However, the data were included in subsequent comprehensive safety analyses of the placebo-controlled phase 2-3 studies37,38; these studies were therefore included. Three medications, eslicarbazepine,37 perampanel,39 and brivaracetam,38 had such analyses. We reviewed these analyses in addition to individual studies. The final analysis included 17 studies of 5 ASMs involving 5996 patients, including 4000 patients treated with ASMs and 1996 treated with placebo. Table 1 summarizes these studies.

Table 1. Summary of Studiesa.

| Drug | Source | Study dates | Epilepsy type | Age, y | Prescription duration (titration/maintenance), wk | No. | Suicidality scale used | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASM | Placebo | |||||||

| Brivaracetam | French et al,34 2010 | 2005-2006 | Focal | 16-65 | 7 (0/7) | 52 | 54 | None |

| Van Paeschen et al,35 2013 | 2005-2006 | Focal | 16-65 | 10 (3/7) | 105 | 52 | None | |

| Ryvlin et al,25 2014 | 2007-2009 | Focal | 16-70 | 12 (0/12) | 199 | 100 | None | |

| Biton et al,26 2014 | 2007-2009 | Focal | 16-70 | 12 (0/12) | 101 | 98 | None | |

| Kwan et al,36 2015 | 2010-2013 | Focal, PGE (10%) | 16-70 | 16 (8/8) | 311b | 121 | None | |

| Klein et al,27 2015 | 2010-2013 | Focal | 16-80 | 12 (0/12) | 503 | 261 | C-SSRS | |

| Cannabidiol | Devinsky et al,28 2017 | NS | DS | 2-18 | 14 (2/12) | 61 | 59 | C-SSRS |

| Thiele et al,30 2018 | 2015-2016 | LGS | 2-55 | 14 (2/12) | 86 | 85 | C-SSRS | |

| Cenobamate | Krauss et al,32 2020 | 2013-2015 | Focal | 18-70 | 18 (6/12) | 329 | 108 | C-SSRS |

| Chung et al,33 2020 | 2011-2013 | Focal | 18-65 | 12 (6/6) | 113 | 108 | C-SSRS | |

| Eslicarbazepine | Elger et al,18 2009 | 2004-2005 | Focal | 16-75 | 14 (2/12) | 300 | 102 | C-CASA, retrospective |

| Ben Menachem et al,19 2010 | 2004-2005 | Focal | 16-75 | 14 (2/12) | 295 | 100 | C-CASA, retrospective | |

| Sperling et al,20 2015 | 2008-2012 | Focal | 16-75 | 14 (2/12) | 426 | 224 | C-SSRS | |

| Perampanel | French et al,21 2012 | 2008-2010 | Focal | ≥12 | 19 (6/13) | 267 | 121 | No |

| French et al,22 2013 | 2008-2011 | Focal | ≥12 | 19 (6/13) | 250 | 136 | No | |

| Krauss et al,23 2012 | 2008-2010 | Focal | ≥12 | 19 (6/13) | 521 | 185 | No | |

| French et al,24 2015 | 2011-2014 | PGE | ≥12 | 19 (6/13) | 81 | 82 | C-SSRS | |

| Total | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4000 | 1996 | NA |

Abbreviations: ASM, antiseizure medications; C-CASA, Columbia-Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment; C-SSRS, Columbia Suicidality Severity Rating Scale; DS, Dravet syndrome; LGS, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome; NA, not applicable; NS, not stated; PGE, primary generalized epilepsy.

For patients treated with eslicarbazepine, perampanel, and brivaracetam, data analysis also included published safety analysis of pooled pivotal and phase 3 studies.37,38,39

This was a flexible dose study: 359 patients were treated with brivaracetam, 48 were treated with <50 mg/d, and 311 were treated with 50 to 150 mg/d. Only the latter patients are included in the analyses. No suicidality occurred in patients treated with a lower dose.

Before 2011, suicidality (ideation and behavior/attempts) was reported as self-reported TEAEs. Three medications included studies that were completed before 2011: perampanel (3 of 4 studies), eslicarbazepine (2 of 3 studies) and brivaracetam (2 of 4 studies). In these studies and in the pooled analysis of safety (perampanel39) and or psychiatric and behavioral adverse events (eslicarbazepine,37 brivaracetam38), suicidality TEAEs were further identified by standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities queries for suicide/self-injury (TEAEs with the preferred terms suicide, suicidal, or self-injury). For eslicarbazepine, suicidality was also evaluated retrospectively by blinded review using the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment.18,19,37

In February 2011, the FDA issued a guidance for suicidality evaluation in clinical trials, “Draft Guidance for Suicidality: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials,”2 and mandated that suicidal ideation and behavior assessment based on the C-SSRS be added to all studies of central nervous system drugs. All ongoing and subsequent studies used the C-SSRS in addition to suicidality TEAE reporting. These included 7 ASM studies, 1 each of eslicarbazepine, perampanel, and brivaracetam and 2 each of cannabidiol and cenobamate,20,24,27,28,30,32,33 totaling 2526 patients (42.13% of the total 5996 evaluated), including 1599 patients treated with ASMs and 927 treated with placebo.

Two studies included 1 treatment arm each with active medication doses that were ineffective and are not approved for treatment: 2 mg of perampanel23 and 400 mg of eslicarbazepine.18 These groups were included in the analysis. One case of perampanel-treated suicidal ideation occurred in the 2-mg arm. None of the patients treated with 400 mg of eslicarbazepine had suicidality. Three brivaracetam studies25,26,36 included treatment arms with doses less than the approved 50- to 200-mg dose. No suicidality was reported in patients treated with the lower doses. Patients treated with the lower doses were not included in the comprehensive safety review of all 5 double-blind brivaracetam phase 2 and 3 studies and were therefore not included in our analysis. Two studies, both of cannabidiol, included patients with epilepsy associated with severe cognitive impairment, Dravet syndrome,28 and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.30 Both studies used the C-SSRS in addition to spontaneous adverse event reporting.

For brivaracetam, a discrepancy existed between the primary study articles, which reported 3 cases of suicidality among 6 studies, and a comprehensive safety review of those studies that reported 6 cases (all suicidal ideation, no attempts). Detailed review of the articles, clinical study reports, and discussion with authors showed that the discrepancy was due to inclusion in the safety review of 1 patient treated with brivaracetam in a nonpivotal phase 3 study36 and 2 patients treated with placebo in 2 pivotal phase 3 studies25,26 whose suicidal ideation occurred not during the placebo phase but during the open-label extension. The discrepancy resulted from the adjudication rules used in the safety review, eg, events reported during the open-label extension without a date of onset were assumed to start during the double-blind phase. We included the first (brivaracetam treatment) case because suicidality occurred during the blinded placebo-controlled study but not the other 2 (placebo treatment) cases because suicidality occurred during the open-label extension, not the placebo-controlled study. FDA safety analysis reported suicidality for both the controlled and extension-study patients and included all 6 cases.40 Thus, our review has fewer placebo-related suicidality cases than the FDA review.

In all studies, either intent-to-treat or safety populations (studies with safety population > intent-to-treat population) were used to determine patient numbers. Across the studies, patients treated with ASMs and with placebo were matched for sex, age, epilepsy duration, baseline seizure frequency, and number of concomitant ASMs as well as specific concomitant ASMs. In all studies, the new treatment, ASM or placebo, was adjunctive to other ASMs that remained stable during the study.

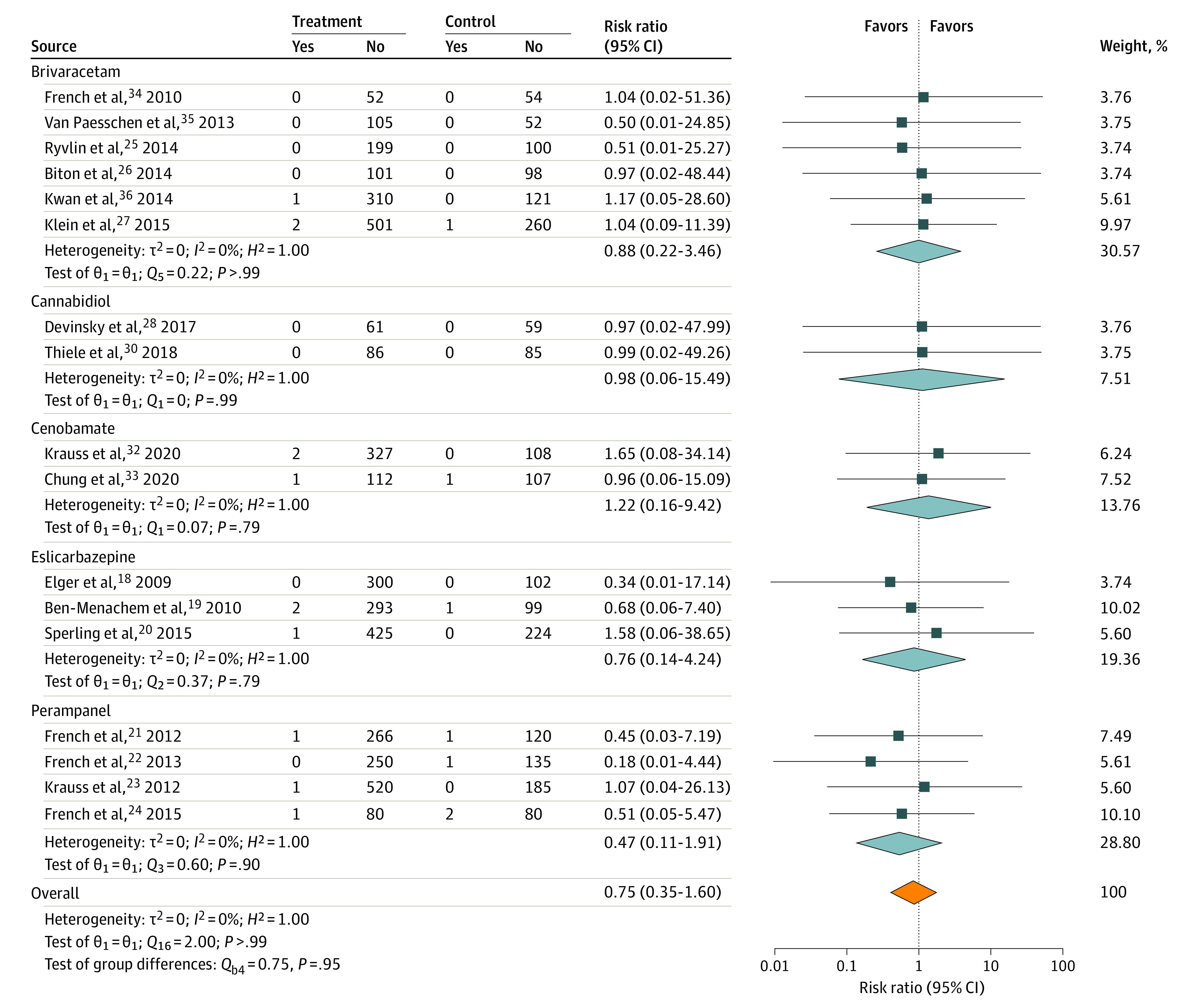

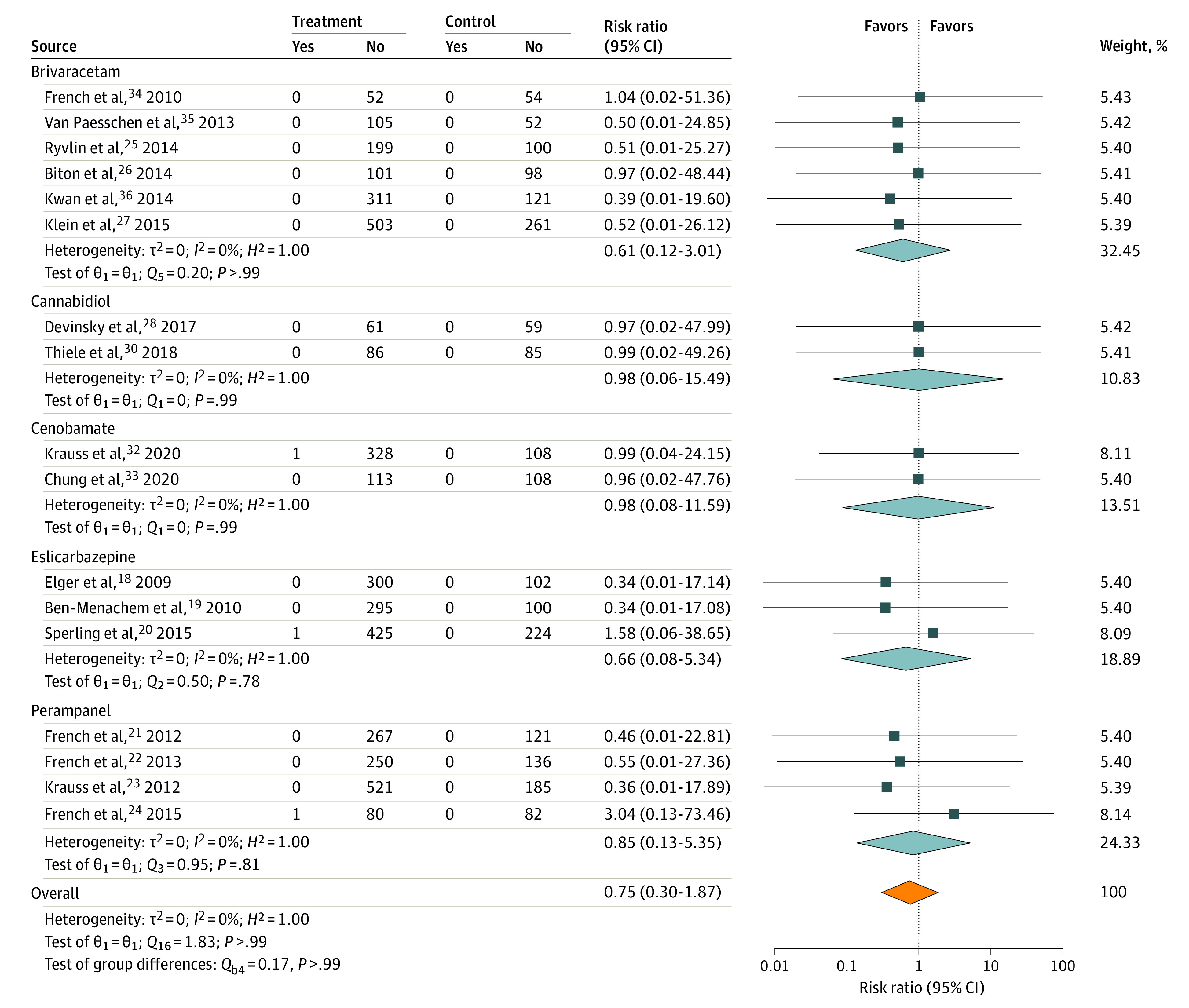

There were 4000 patients who received active treatment compared with 1996 patients treated with placebo. Twelve of 4000 patients treated with ASM (0.30%) had suicidal ideation, compared with 7 of 1996 patients treated with placebo (0.35%) (χ2 = 0.108; P = .74). Three patients who received active treatment and no patients treated with placebo attempted suicide (χ2 = 1.498; P = .22). There were no completed suicides (Table 2). Results of meta-analysis indicate that overall there is no evidence of statistically significantly increased risk of suicidal ideation (Figure 1; overall risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.35-1.60) or suicide attempt (Figure 2; risk ratio, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.30-1.87) in participants randomized to receive study ASM vs placebo. There was no evidence of bias54 or heterogeneity55 (Figure 1).

Table 2. Suicidality in Patients Treated With ASM and Placebo.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients treated with ASM | Patients treated with placebo | ||

| Total patient No. | 4000 | 1996 | NA |

| Suicidal ideationb | 12 (0.30) | 7 (0.35) | .74 |

| Suicide attempt | 3 (0.08) | 0 | .22 |

| Suicide | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

Abbreviations: ASM, antiseizure medications; NA, not applicable.

χ2.

Includes 3 patients with suicide attempt.

Figure 1. Risk of Suicidal Ideation.

RR indicates risk ratio.

Figure 2. Risk of Suicide Attempt.

RR indicates risk ratio.

Suicidal ideation and attempts for individual drugs are shown in Table 3. No statistically significant difference was seen between patients treated with ASMs and with placebo for suicidal ideation or suicide attempts for any 1 drug. Risk ratios of suicidal ideation for individual drugs vs placebo were 0.88 for brivaracetam, 1.22 for cenobamate, 0.76 for eslicarbazepine, and 0.47 for perampanel. There were no suicidalities reported with cannabidiol. With perampanel, there was numerically greater suicidal ideation among patients treated with placebo (4 of 524) than among patients treated with perampanel (3 of 1119; χ2 = 2.063; P = .15).

Table 3. Suicidality by Individual ASMs.

| ASMs | No. (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients treated with ASM | Patients treated with placebo | ||

| Brivaracetam | |||

| Total No. of patients | 1271 | 686 | NA |

| Suicidal ideation | 3 (0.24) | 1 (0.15) | .67 |

| Suicide attempt | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Suicide | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Cannabidiol | |||

| Total No. of patients | 147 | 144 | NA |

| Suicidal ideation | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Suicide attempt | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Suicide | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Cenobamate | |||

| Total No. of patients | 442 | 216 | |

| Suicidal ideationb | 4 (0.91) | 1 (0.46) | .54 |

| Suicide attempt | 1 | 0 | .48 |

| Suicide | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Eslicarbazepine | |||

| Total No. of patients | 1021 | 426 | |

| Suicidal ideationb | 3 (0.29) | 1 (0.24) | .85 |

| Suicide attempt | 1 | 0 | .56 |

| Suicide | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

| Perampanel | |||

| Total No. of patients | 1119 | 524 | |

| Suicidal ideationb | 3 (0.27) | 4 (0.76) | .15 |

| Suicide attempt | 1 | 0 | .49 |

| Suicide | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

Abbreviations: ASM, antiseizure medications; NA, not applicable.

χ2.

Includes patient with suicide attempt.

One of the 3 eslicarbazepine studies included suicidality as an adverse event when it appeared on the C-SSRS but was not reported by the patient.20 In this study, there was a difference between verbal reports of suicidality and suicidality as assessed by the C-SSRS. None of the 426 patients treated with eslicarbazepine and none of the 224 patients treated with placebo reported suicidal ideation, and 1 of 426 patients treated with eslicarbazepine and none of the 224 patients treated with placebo reported suicide attempts. On the C-SSRS, 15 of 426 patients treated with eslicarbazepine and 10 of 224 patients treated with placebo had suicidal ideation (χ2 = 0.353; P = .55), and 4 of 426 and 2 of 224 patients treated with eslicarbazepine and placebo, respectively, had suicidal behavior (χ2 = 0.003; P = .95).

Discussion

The FDA has extrapolated the findings of the 2008 meta-analysis to subsequently approved ASMs, requiring warning of increased risk of suicidality for 9 of 10 new-molecule ASMs. Our meta-analysis shows no increased risk of suicidality in patients with refractory epilepsy in randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials of 5 ASMs approved since the 2008 FDA study. These 5 ASMs, eslicarbazepine, perampanel, brivaracetam, cannabidiol, and cenobamate, were evaluated in 17 studies including 5996 patients, of which 4000 patients were treated with ASM and 1996 were treated with placebo. No difference in suicidality was observed for either the group as a whole or for any individual medication. While there was a numerical difference in suicide attempts among patients treated with ASM (3 of 4000) compared with patients treated with placebo (0 of 1996), the difference was not significant. There were no completed suicides. Among the individual ASMs, there was greater suicidal ideation in patients treated with placebo vs perampanel (P = .15). Three ASMs had suicidal ideation risk ratio of less than 1 and 1 ASM had a risk ratio of less than 1, all statistically nonsignificant. One medication, cannabidiol, had no associated suicidality.

These results differ from the 2008 FDA meta-analysis, whose methodological shortcomings were discussed above.3 The main limitations were retrospective analysis of spontaneous, nonstandardized reports of suicidality as adverse events, inconsistent ascertainment and definitions of suicidal ideation and behavior, and diagnostically heterogenous trials and patient populations. All ASMs were grouped together even though their risks varied, with increase in 2 of 11 ASMs and nonsignificant increase or decrease in 7 and 2. Studies of adjunctive treatment and of monotherapy (vs placebo) were lumped together, as were studies of patients with different diseases and therefore possibly different suicidality risks.3 The study did not analyze suicidality before participation in the trials and did not adjust for previous suicidal behavior, the most significant risk factor for attempted and completed suicides.3,41,42

In contrast with the ASMs evaluated prior to 2008, suicidality was studied in a systematic and standardized way with the newer drugs. Eleven of the 17 randomized clinical trials of the 5 drugs reviewed here started in 2008 or later. They included targeted prespecified measures of suicidality with prospectively collected data. Since 2011, all studies have included structured evaluation of suicidality using a validated scale, the C-SSRS. These included 7 studies, with 2526 of 5996 patients (42.13%) and the 2 largest studies, eslicarbazepine20 (n = 650) and brivaracetam27 (n = 764). These methodological modifications make our findings robust.

Our analyses broadly agree with suicidality reports among patients treated with ASM vs placebo in the published FDA safety reviews of perampanel, brivaracetam, cenobamate, and cannabidiol.40,43,44 The FDA concluded that the ASM suicidality class effect should be applied. This conclusion was largely based on the 2008 analysis. It did not include a statistical evaluation of the trial data and included in the ASM vs placebo comparisons were ASM cases from uncontrolled, open-label treatment periods in which suicidality was reported only for ASM and following longer treatment exposures. The FDA suggested that suicidality symptoms may potentially be associated with other psychiatric adverse events, such as hostility and agitation, but provided no evidence for this. They included medication overdoses as possible signs of suicidality. They also noted that suicidality symptoms usually resolved when ASMs were discontinued. These associations are worth exploring but were outside of the analysis of the double-blind study data.

The FDA suicidality risk warnings for ASMs as a class has affected epilepsy practice and antiseizure drug development. In the FDA drug label warnings and precautions sections, suicidality risk tops the list for lacosamide, perampanel, eslicarbazepine, and brivaracetam and is third from the top for cenobamate, cannabidiol/epidiolex, and fenfluramine even though there were no suicidalities in cannabidiol randomized clinical trials and suicidality was not assessed in fenfluramine randomized clinical trials. Some patients may refuse to take the medication because of the warning, forgoing the medications’ potential benefits, which may include seizure freedom or amelioration with reduction in risk of mortality, including sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Although we are not aware of any studies documenting this, all 6 clinician authors (P.K., O.D., J.F., C.H., G.K. M.S.) have seen such patients. Notably, the risk of death from sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, status epilepticus, and drowning due to a seizure (>4/1000 per year)45,46,47,48,49 exceeds the 2.1/1000 per year suicide risk in the 2008 FDA meta-analysis. New ASMs reduce the risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy49; failure to take an ASM may increase sudden unexpected death in epilepsy risk.50 Patients may worry about suicidality risk, possibly adding to their anxiety and disease burden. The prominent ASM suicidality warning since 2008 may do more harm than benefit. Our analysis found no evidence to support such warning for the 5 new ASMs we evaluated.

The FDA labeling suicidality warning for ASMs is also inconsistent. The recently approved intranasal diazepam acute repetitive seizure rescue treatment, Valtoco (Neurelis), has suicidal behavior and ideation listed second in the warning and precaution category. Diastat (Bausch Health), the older rectally formulated diazepam, used for the same indication, has no such warning.

The focus on suicidality has affected clinical research of new ASM development. Since 2013, all phase 1-3 studies have excluded patients with suicidal risks. As suicidality is higher among patients with uncontrolled epilepsy,51,52 excluding patients at greatest risk limits knowledge of how new ASMs affect suicidality risk in a high-risk population. A 2019 international meta-analysis of suicidality among patients with epilepsy found a 23.2% prevalence for suicidal ideation and 7.4% for suicide attempts.6 Excluding these patients from pivotal ASM studies leaves out a significant proportion of patients with epilepsy and limits the studies’ relevance. Further, suicidality evaluation is now mandatory in studies where it may be inappropriate. Recent ASM studies of patients with epilepsy with severe cognitive impairment, such as Dravet syndrome (cannabidiol), Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (cannabidiol, fenfluramine, perampanel, and carisbamate), or epileptic encephalopathy (soticlestat) all included the C-SSRS.28,29,30 This scale was never validated in patients with severe cognitive impairment or in young children. Mandating structured suicidality evaluations without a valid measure adds time and cost to drug development without benefit.

Limitations

Our study limitations include sample size and lack of use of standardized suicidality questionnaires in studies conducted before 2011. Lack of formal suicidality assessment in studies from 2008 to 2011 prevents a more accurate ascertainment of risk for those drugs. The number of evaluable individuals in our study is sizable but smaller than the FDA’s 2008 analysis, which included 10 942 individuals with epilepsy. Suicide is a low-frequency event, and confidence intervals for the 5 ASMs we evaluated were wide. Because individuals with suicidality and uncontrolled psychiatric disease were excluded from more recent studies, our data cannot evaluate whether ASMs affect suicidality in high-risk individuals. Cannabidiol was mostly tested in children, who have lower suicide risks. Three of the 10 new-molecule ASMs approved by the FDA since 2008 (lacosamide, ezogabine, and clobazam) did not assess suicidality prospectively and were therefore left out of our analysis. Two more, everolimus and fenfluramine, did not evaluate suicidality. Therefore, our analysis was limited to 5 of 10 ASMs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study shows that in patients with epilepsy without a history of suicidality, there is no evidence that any of the 5 recently approved ASMs prospectively evaluated using FDA suicidality evaluation guidelines increase the risk of suicidality. Therefore, the FDA-mandated suicidality class warning for these drugs is not warranted. Determination and labeling of suicidality risk should be based on evidence from randomized clinical trials and individualized for each new ASM.

eFigure. PRISMA Flow Diagram

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Statistical review and evaluation: antiepileptic drugs and suicidality. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Statistical-Review-and-Evaluation--Antiepileptic-Drugs-and-Suicidality.pdf

- 2.Busko M. FDA advisory members agree antiepileptics pose suicidality risk, nix need for black-box warning. Medscape. Published July 11, 2008. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/577432

- 3.Hesdorffer DC, Kanner AM. The FDA alert on suicidality and antiepileptic drugs: fire or false alarm? Epilepsia. 2009;50(5):978-986. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Mortensen PB, Sidenius P, Agerbo E. Epilepsy and risk of suicide: a population-based case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(8):693-698. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70175-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamid H, Liu H, Cong X, et al. Long-term association between seizure outcome and depression after resective epilepsy surgery. Neurology. 2011;77(22):1972-1976. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823a0c90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham N, Buvanaswari P, Rathakrishnan R, et al. A meta-analysis of the rates of suicide ideation, attempts and deaths in people with epilepsy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1451. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16081451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266-1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Menachem E, Biton V, Jatuzis D, Abou-Khalil B, Doty P, Rudd GD. Efficacy and safety of oral lacosamide as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2007;48(7):1308-1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halász P, Kälviäinen R, Mazurkiewicz-Beldzińska M, et al. ; SP755 Study Group . Adjunctive lacosamide for partial-onset seizures: efficacy and safety results from a randomized controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2009;50(3):443-453. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01951.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung S, Sperling MR, Biton V, et al. ; SP754 Study Group . Lacosamide as adjunctive therapy for partial-onset seizures: a randomized controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2010;51(6):958-967. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter RJ, Partiot A, Sachdeo R, Nohria V, Alves WM; 205 Study Group . Randomized, multicenter, dose-ranging trial of retigabine for partial-onset seizures. Neurology. 2007;68(15):1197-1204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259034.45049.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodie MJ, Lerche H, Gil-Nagel A, et al. ; RESTORE 2 Study Group . Efficacy and safety of adjunctive ezogabine (retigabine) in refractory partial epilepsy. Neurology. 2010;75(20):1817-1824. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fd6170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.French JA, Abou-Khalil BW, Leroy RF, et al. ; RESTORE 1/Study 301 Investigators . Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ezogabine (retigabine) in partial epilepsy. Neurology. 2011;76(18):1555-1563. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182194bd3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conry JA, Ng Y-T, Paolicchi JM, et al. Clobazam in the treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2009;50(5):1158-1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng YT, Conry JA, Drummond R, Stolle J, Weinberg MA; OV-1012 Study Investigators . Randomized, phase III study results of clobazam in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Neurology. 2011;77(15):1473-1481. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318232de76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagae L, Sullivan J, Knupp K, et al. ; FAiRE DS Study Group . Fenfluramine hydrochloride for the treatment of seizures in Dravet syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10216):2243-2254. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32500-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nabbout R, Mistry A, Zuberi S, et al. ; FAiRE, DS Study Group . Fenfluramine for treatment-resistant seizures in patients with Dravet syndrome receiving stiripentol-inclusive regimens: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(3):300-308. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elger C, Halász P, Maia J, Almeida L, Soares-da-Silva P; BIA-2093-301 Investigators Study Group . Efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treatment in adults with refractory partial-onset seizures: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase III study. Epilepsia. 2009;50(3):454-463. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Menachem E, Gabbai AA, Hufnagel A, Maia J, Almeida L, Soares-da-Silva P. Eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive therapy in adult patients with partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2010;89(2-3):278-285. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sperling MR, Abou-Khalil B, Harvey J, et al. ; 304 Study Team . Eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive therapy in patients with uncontrolled partial-onset seizures: results of a phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2015;56(2):244-253. doi: 10.1111/epi.12894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.French JA, Krauss GL, Biton V, et al. Adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial-onset seizures: randomized phase III study 304. Neurology. 2012;79(6):589-596. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182635735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.French JA, Krauss GL, Steinhoff BJ, et al. Evaluation of adjunctive perampanel in patients with refractory partial-onset seizures: results of randomized global phase III study 305. Epilepsia. 2013;54(1):117-125. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krauss GL, Serratosa JM, Villanueva V, et al. Randomized phase III study 306: adjunctive perampanel for refractory partial-onset seizures. Neurology. 2012;78(18):1408-1415. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318254473a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.French JA, Krauss GL, Wechsler RT, et al. Perampanel for tonic-clonic seizures in idiopathic generalized epilepsy: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2015;85(11):950-957. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryvlin P, Werhahn KJ, Blaszczyk B, Johnson ME, Lu S. Adjunctive brivaracetam in adults with uncontrolled focal epilepsy: results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):47-56. doi: 10.1111/epi.12432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biton V, Berkovic SF, Abou-Khalil B, Sperling MR, Johnson ME, Lu S. Brivaracetam as adjunctive treatment for uncontrolled partial epilepsy in adults: a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):57-66. doi: 10.1111/epi.12433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein P, Schiemann J, Sperling MR, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, parallel-group study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive brivaracetam in adult patients with uncontrolled partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2015;56(12):1890-1898. doi: 10.1111/epi.13212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devinsky O, Cross JH, Wright S. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):699-700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1708349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devinsky O, Patel AD, Cross JH, et al. ; GWPCARE3 Study Group . Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1888-1897. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiele EA, Marsh ED, French JA, et al. ; GWPCARE4 Study Group . Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1085-1096. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30136-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller I, Scheffer IE, Gunning B, et al. ; GWPCARE2 Study Group . Dose-ranging effect of adjunctive oral cannabidiol vs placebo on convulsive seizure frequency in Dravet syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(5):613-621. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krauss GL, Klein P, Brandt C, et al. Safety and efficacy of adjunctive cenobamate (YKP3089) in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-response trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(1):38-48. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30399-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung SS, French JA, Kowalski J, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of adjunctive cenobamate in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures. Neurology. 2020;94(22):e2311-e2322. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.French JA, Costantini C, Brodsky A, von Rosenstiel P; N01193 Study Group . Adjunctive brivaracetam for refractory partial-onset seizures: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;75(6):519-525. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7f7f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Paesschen W, Hirsch E, Johnson M, Falter U, von Rosenstiel P. Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in adults with uncontrolled partial-onset seizures: a phase IIb, randomized, controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2013;54(1):89-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwan P, Trinka E, Van Paesschen W, Rektor I, Johnson ME, Lu S. Adjunctive brivaracetam for uncontrolled focal and generalized epilepsies: results of a phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose trial. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):38-46. doi: 10.1111/epi.12391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andermann E, Biton V, Benbadis SR, et al. ; Study 301, 302 and 304 Investigators . Psychiatric and cognitive adverse events: a pooled analysis of three phase III trials of adjunctive eslicarbazepine acetate for partial-onset seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;82:119-127. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandt C, Klein P, Badalamenti V, Gasalla T, Whitesides J. Safety and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in epilepsy: in-depth pooled analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;103(pt A):106864. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.106864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinhoff BJ, Ben-Menachem E, Ryvlin P, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive perampanel for the treatment of refractory partial seizures: a pooled analysis of three phase III studies. Epilepsia. 2013;54(8):1481-1489. doi: 10.1111/epi.12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application number: 205836Orig1s000, 205837Orig1s000, 205838Orig1s000. Accessed June 11, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2016/205836Orig1s000_205837Orig1s000_205838Orig1s000MedR.pdf

- 41.Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193-199. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mula M, Kanner AM, Schmitz B, Schachter S. Antiepileptic drugs and suicidality: an expert consensus statement from the Task Force on Therapeutic Strategies of the ILAE Commission on Neuropsychobiology. Epilepsia. 2013;54(1):199-203. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application number: 202834Orig1s000. Accessed June 11, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2012/202834Orig1s000MedR.pdf

- 44.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application number: 212839Orig1s000. Accessed June 11, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/210365Orig1s000SumR.pdfhttps://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212839Orig1s000MedR.pdf

- 45.Devinsky O, Spruill T, Thurman D, Friedman D. Recognizing and preventing epilepsy-related mortality: a call for action. Neurology. 2016;86(8):779-786. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thurman DJ, Hesdorffer DC, French JA. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: assessing the public health burden. Epilepsia. 2014;55(10):1479-1485. doi: 10.1111/epi.12666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cihan E, Hesdorffer DC, Brandsoy M, et al. Dead in the water: epilepsy-related drowning or sudden unexpected death in epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2018;59(10):1966-1972. doi: 10.1111/epi.14546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thurman DJ, Logroscino G, Beghi E, et al. ; Epidemiology Commission of the International League Against Epilepsy . The burden of premature mortality of epilepsy in high-income countries: a systematic review from the Mortality Task Force of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2017;58(1):17-26. doi: 10.1111/epi.13604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryvlin P, Cucherat M, Rheims S. Risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy in patients given adjunctive antiepileptic treatment for refractory seizures: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomised trials. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(11):961-968. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70193-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verducci C, Hussain F, Donner E, et al. SUDEP in the North American SUDEP Registry: the full spectrum of epilepsies. Neurology. 2019;93(3):e227-e236. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nilsson L, Ahlbom A, Farahmand BY, Asberg M, Tomson T. Risk factors for suicide in epilepsy: a case control study. Epilepsia. 2002;43(6):644-651. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.40001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamed SA, Elserogy YB, Abdou MA, Abdellah MM. Risks of suicidality in adult patients with epilepsy. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(2):33-42. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v2.i2.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application number: 210365Orig1s000. Accessed June 11, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/210365Orig1s000SumR.pdf.

- 54.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. , eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.2.0. Cochrane; 2017, https://training.cochrane.org/handbook

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. PRISMA Flow Diagram