Abstract

A total of 251 Dura cross Pisifera (DxP) hybrid palms from six populations descending from six parental African Pisifera origins and involving 12 progenies were analyzed with 19 selected Simple Sequence Repeats (SSR) markers. A total of 110 alleles were produced, ranging from three to eight per SSR, with a mean of 5.8 alleles per SSR locus. Of these, 68.5% were considered shared alleles by more than one population and the remaining 31.5% were population specific alleles. They generated between six and 21 haplotypes in all populations, and depending on the SSR marker, between one and 10 haplotypes within populations. Various parameters for analyzing genetic variability, differentiation and genetic structure were computed using GenAlEx, Structure and Darwin software. The obtained results confirmed microsatellites as a robust, feasible and trustful method for obtaining DNA fingerprints, tracing the source of oil palm samples. With respect to the authenticity of materials or for solving legitimacy issues, accession belonging to each population by SSR markers could be distinguished, but additional SSR should be screened for improving this process.

Keywords: Elaeis guineensis, fingerprint, pisifera, DxP, diversity, SSR markers

Introduction

The oil palm (Elaeis guineensis, Jacq.) is a perennial crop that is expected to reach a production of 75 million tons of vegetable oil in the coming years (Foreign Agricultural Service. USDA, 2020). This tropical palm, originally from West Africa, is nowadays the biggest vegetable oil source in the world. The revolution of the crop breeding started with the discovery of the dominant monogenic inheritance of the Shell thickness gene (Beirnaert and Vanderweyen 1941). The so-called Sh gene determines the three existing fruit variety types in the oil palm: the Dura genotype (D, homozygote dominant with a thick shell), Pisifera (P, homozygote recessive and usually, female sterile shell-less genotype) and the hybrid Tenera (T). The heterozygous Tenera is the product from DxP crosses, has a shell with 30% more mesocarp than dura and produces significantly more oil (Corley and Tinker 2016). The Sh gene has been very well characterized (Singh et al. 2013a), and it became a priority for oil palm research with the subsequent application in breeding programs. Currently, most oil palm high productive varieties represent mixtures of closely related Tenera genotypes derived from Dura by Pisifera crosses, designated for both oil and seed production. The mother palms represent several selected individuals of DxD selfings and the pollen donors are recovered Pisifera palms derived from TxT or TxP crosses. Particularly, the selected D palms may change over time for seed production (Setiawan 2017). Semi-clonal and bi-clonal parental palms are entering slowly in this process, due to frequently observed malformation of bunches in the resulting Tenera palms, if the parents are multiplied in vitro (Ong-Abdullah et al. 2015).

Indonesian producers entered years ago into a new stage of applied research in the field of molecular genetics, for demonstrating that sustainable palm oil production is possible. This does not only improve the quality of the plant material that can be obtained, but facilitates also the process of seed production and monitoring (Barcelos et al. 2015). These techniques promote seeds or plants which have been selected by long experience and well-established breeding methods, giving an added value of quality and reliability, together with a molecular certification. Plant information can be reinforced with molecular information reflecting the potential of each individual. In addition, the uniqueness of each individual may not be distinguished from the phenotype, but can be seen from molecular information. Each individual has its own “fingerprint” that shows the individual’s uniqueness, kinship with other individuals and the parental origin of that individual (Corley and Tinker 2016). Sometimes fraudulent seed trade has been detected, where oil palm seeds are sold with a false variety name (Cheyns and Rafflegeau 2005). Normally, falsification of seeds cannot be detected and may be possible when palms are growing, but it is generally difficult to distinguish varieties phenotypically with certainty. However, with genetic marker analysis revealing variety-specific fingerprints, the parental origin and the authenticity of these seeds can be known in a short time (Teh et al. 2019).

One of the molecular marker types used to analyze diversity and kinship relationships are Simple Sequence Repeats or SSRs (Singh et al. 2007). SSR markers amplify the scattered DNA sequences in the genome and produce often highly polymorphic DNA fragments between accessions. Microsatellites form part of a wide database of molecular resources in oil palm, which is increasing continuously, and even the genome sequence has been available for some years (Singh et al. 2013b). However, nowadays large sets of new markers, such as SNPs (Cros et al. 2018), are applied for these purpose and analyses can be refined even more considering additional genomic regulatory factors such as epigenetics (Kawakatsu and Ecker 2019). Although SSR markers may be considered classic, in the case of crops where genetic resources are limited, they are still useful, as shown in a recent example of sago palm, a close relative of the oil palm (Purwoko et al. 2019).

Billotte et al. (2005) published some SSR markers in oil palm, which were also relevant for this study. Singh et al. (2007) reported a set of 12 informative SSR markers for fingerprinting oil palm accessions. Since then, SSR markers have been used in different studies related to the analysis of germplasm diversity or for differentiating oil palm populations (Cochard et al. 2009, Okoye et al. 2018, Ting et al. 2014). Microsatellites also provide a powerful method to evaluate different origins of plant material. More diversity gives a wider range of genetic variability, which is the success of any crop improvement program, something needed in perennial trees such as oil palm with a narrow genetic base (Kumar et al. 2018). Previously, SSRs have been regularly used for the development of molecular breeding strategies (Billotte et al. 2010, Cros et al. 2015, Marchal et al. 2016) and character studies (Montoya et al. 2013, Morcillo et al. 2013, Singh et al. 2014).

There are important companies that are oil palm seed producers in Indonesia. Innovation and genetic resources are needed by these companies to become trustful producers and to gain good positions in this highly competitive market. Currently, there are specific seed varieties as achievements of breeding programs that contain outstanding phenotypes among their variants. Moreover, the released varieties are continuously monitored and evaluated for validating the selection of the parental material in the breeding program and for producing a superior next generation in the future. The uniqueness of varieties can be seen phenotypically but a more detailed genotypic analysis was not available. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a preliminary DNA fingerprint system in order to analyze genetic variation, the structure of breeding populations and to identify markers for specific DxP varieties, which later on, can be used to prevent counterfeiting of seeds in the field.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

A total of 251 individual DxP palms from 16 progenies were analyzed. All pisifera parents were from six different African origins which determine varieties with specific superior characters called Siriwijaya (SJ) 1 to 6. These elite parents were collected in the 90’s to form part of the Bina Sawit Makmur (BSM) breeding program and since that time they were continuously evaluated and selected. Each of the six Sriwijaya DxP varieties has beside a general favorable agronomic performance, different superior characteristics. For example: SJ 1 DxP has advantages in fresh fruit bunch (FFB) productivity, SJ 3 is outstanding in terms of bunch numbers per year and SJ 6 has a high yield potential. The characteristics of the DxP varieties used in this research are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of variety samples based on the male parent origin and its superior characters

| No | Pisifera origin | Variety | Total palms | No of DxP progenies | Superior characters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nigeria | SJ 1 | 52 | 2 | VIR, PO, FFB, HT, BW |

| 2 | Ghana | SJ 2 | 50 | 3 | FL, HT, FFB |

| 3 | Ekona | SJ 3 | 50 | 4 | BN, FFB |

| 4 | Avros | SJ 4 | 19 | 2 | Drought M/F, BW |

| 5 | Dami | SJ 5 | 57 | 2 | SF, IER, FL |

| 6 | Yangambi | SJ 6 | 23 | 3 | OB, OM, BW |

| Total | 251 | 16 | |||

* Bunch number (BN), bunch weight (BW), Drought tolerance, fresh fruit bunch (FFB), fruit color virescens (VIR), frond length (FL), height increment (HT), mesocarp to fruit (MF), oil to wet mesocarp (OWM), oil to bunch (OB), palm oil yield (PO), palm oil industrial extraction rate (IER), shell to fruit (SF).

DNA isolation and SSR analyses

Genomic DNA of E. guineensis plant material was extracted using a modified Cetyl-trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Orozco-Castillo et al. 1994) from spare leaves of every accession grown at the Surya Adi Research Station at OKI (South Sumatra, Indonesia).

Thirty microsatellites covering all chromosomes of oil palm were preselected from the publication of Billotte et al. (2005) and finally, nineteen unlinked SSRs showing clear polymorphisms were used in this study (Table 2). The SSRs fragments were amplified in a C100 BioRad thermocycler and the PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 25 μL containing: 1× Promega GoTaq® Green master mix (Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl2 and reaction buffer), 15 μmol forward primer, 15 μmol reverse primer and 10 ng of genomic DNA. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturing at 94°C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing step at 53°C for 45 seconds, extension step at 72°C for 1 minute and a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 minutes. The amplified products were separated on 8% polyacrylamide gel in 1× SB buffer (Brody and Kern 2004). The gels were pre-run until constant temperature (50–60°C) was reached. After the electrophoresis process, the DNA bands were visualized using Gelred@ Biotium staining in a Bio Rad Gel DocTM UV-Transiluminator. The polyacrylamide gels were processed via Image Lab Software (version 6.0) along with 50 bp DNA ladder as a standard. Allele sizes were estimated and counted objectively by two different persons for consistency scoring. Unclear bands were discarded and in the case of double or stutter bands, only the upper size band was recorded. Ambiguous genotypes were repeated for verification.

Table 2.

Primer information and allele ranges revealed by microsatellite SSR markers

| No | Locus name | Repeat motif | Sequence | Linkage group | EMBL accession number | Allele range size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primer (5ʹ-3ʹ) | Primer (3ʹ-5ʹ) | ||||||

| 1 | mEgCIR3392 | (GA)21 | AGCAAGGGAGAAAGATG | CGAGCAATCAACCTGACTA | 1 | AJ578660 | 238–250 |

| 2 | mEgCIR3328 | (GA)22 | GAGGGGGTTGGGACATTAC | TAGCTCACAACCCAGAATCTAT | 1 | AJ578648 | 198–224 |

| 3 | mEgCIR3775 | (GA)18 | TCTTGATATTAAAAGGTCAGGAGAA | CGTTCCCTTTTTCCATAGAT | 2 | AJ578724 | 160–198 |

| 4 | mEgCIR3693 | (GA)16 | TGCACACAGGCACACATA | AAAATGGGGTGTAGAGTTG | 2 | AJ578706 | 280–306 |

| 5 | mEgCIR3533 | (GA)15 | TCTATGGCTCTGTCGTGTAT | CGAGCCGGTAGAAACTAT | 2 | AJ578674 | 134–144 |

| 6 | mEgCIR3428 | (GA)15 | GACAGCTCGTGATGTAGA | GTTCTTGGCCGCTATAT | 3 | AJ578667 | 150–168 |

| 7 | mEgCIR0802 | (GA)12 | CTCCTTTGGCGTATCCTTTA | TACGTGCAGTGGGTTCTTTC | 3 | AJ578549 | 214–250 |

| 8 | mEgCIR3382 | (GA)24 | TGTAGGTGGTGGTTAGG | TGTCAGACCCACCATTA | 4 | AJ578655 | 108–130 |

| 9 | mEgCIR2422 | (GA)16 | GCCCTCCCTCAACTCAAAAA | ATGGTGTCTGGGACTCTGAGTA | 5 | AJ578597 | 214–264 |

| 10 | mEgCIR3785 | (GA)21 | AAGCAATATAGGTTCAGTTC | TCATTTTCTAATTCCAAACAAG | 6 | AJ578726 | 314–332 |

| 11 | mEgCIR0788 | (GA)13 | ACATTCCCTCTATTATTCTCAC | GTTTTGTTTGGTATGCTTGT | 6 | AJ578543 | 126–150 |

| 12 | mEgCIR3683 | (GA)23 | GTAGCTTGAACCTGAAA | AGAACCACCGGAGTTAC | 8 | AJ578703 | 128–164 |

| 13 | mEgCIR0894 | (GA)18 | TGCTTCTTGTCCTTGATACA | CCACGTCTACGAAATGATAA | 9 | AJ578562 | 200–238 |

| 14 | mEgCIR2600 | (GA)15 | GGGGATGAGTTTGTTTGTTC | CCTGCTTGGCGAGATGA | 9 | AJ578612 | 280–300 |

| 15 | mEgCIR3362 | (GA)19 | CCCATCATCTGCTCAGGATAGAC | ACCCTCTCCTCTTGGGAAGA | 11 | AJ578652 | 150–168 |

| 16 | mEgCIR3607 | (GA)14 | ATTGCAGAGATGATGAGAAG | GAGATGCTGACAATGGTAGA | 11 | AJ578691 | 190–238 |

| 17 | mEgCIR2427 | (GA)14 | GAAGGGGCATTGGATTT | TACCTATTACAGCGAGAGTG | 11 | AJ578599 | 118–140 |

| 18 | mEgCIR2569 | (GA)16 | TAGCCGCACTCCCACGAAGC | CCAGAATCATCAGACTCGGACAG | 12 | AJ578607 | 226–276 |

| 19 | mEgCIR3544 | (GA)14 | AGCAGGGCAAGAGCAATACT | TTCAGCAGCAGGAAACATC | 14 | AJ578679 | 178–198 |

Data analysis

SSR marker alleles were scored by allele band sizes in each genotype and treated as co-dominant markers. These bi-allelic marker data were used to estimate the diversity in the populations. For each SSR standard genetic parameters were computed using GenAlEx 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse 2012). These included total number of generated haplotypes and haplotypes per population, allele distributions in terms of population specific, shared and total alleles, polymorphic information content (PIC) values, probability of identity (PI) and gene flow (Nm). PI values were calculated as Nei’s genetic identity for each pairwise combination of populations (Nei 1973).

Genetic variability parameters for all six groups were computed as average and effective number of alleles per locus (A and Ae) and the percentage of polymorphic loci (P). Gene diversity for observed and expected heterozygotes (Ho and He), as well as inbreeding coefficients (Fis) were calculated according to Hamrick and Godt (1996).

The evaluation of gene diversity and distribution were calculated using the formulas of Nei (1977) for total genetic diversity (HT), genetic diversity within population (HS), average genetic diversity among subgroups (DST) and partial of total genetic diversity partitioned among population (GST). The genetic structure within and among populations was evaluated using F-statistics FIT, FIS, and FST according to Wright (1965). The FIT and FIS coefficients were measured from homozygotes or heterozygotes, relative to the total expectations (within the entire sample and within population). The FST coefficient was estimated relative to the population differentiation and was determined at the locus level. Gene flow was estimated through two approaches; the first was calculated from Nm (number of migrants per generation) based on GST and the second from the average of rare alleles found only in one population (Slatkin 1985).

A principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was conducted using the GenAlEx program (Peakall and Smouse 2012) to evaluate inter-population relationships based on allele frequency distributions, considering only polymorphic loci in these analyses. Cluster analysis was conducted on genetic identities applying the unweighted pairwise group method using an arithmetic average (UPGMA) with DARwin V6 (Perrier and Jacquemoud-Collet 2006). AMOVA (Analysis on Molecular Variance) analysis was also performed with the GenAlEx program.

Structure V2.3 (Pritchard et al. 2000) was used for assigning the individuals into subpopulations when the number of groups is unknown (K value). The optimal K value was determined using Structure Harvester (http://taylor0.biology.ucla.edu/struct_harvest/, Earl and vonHoldt 2012). Additional in silico analyses were performed by (i) combining all alleles of all SSR loci, (ii) by combining all specific alleles of each population and (iii) SSR loci containing population specific alleles for each variety using Microsoft Excel.

Results

SSRs polymorphisms

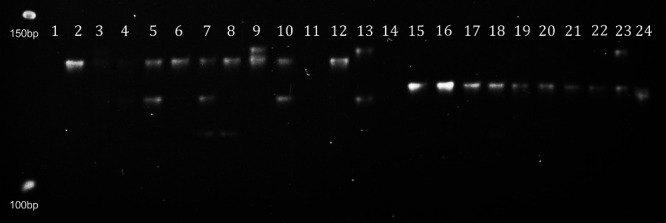

SSR markers produced different band sizes which were scored for each genotype obtaining co-dominant patterns (Fig. 1). The analysis results are presented in the Table 3 for each SSR. Nineteen SSRs produced a total of 110 polymorphic alleles, ranging from 3 (mEgCIR3392) to 8 (mEgCIR0802, mEgCIR3328 and mEgCIR3607) per SSR with an average of 5.8 SSR alleles per locus. Considering all populations, these markers distinguished between six and twenty one haplotypes. Within populations, from one to ten haplotypes were generated depending on the SSR marker.

Fig. 1.

Gel example for SSR mEgCIR2427 where it is shown five out of six alleles produced by this marker in twenty four palms. Line one: 50 bp DNA ladder.

Table 3.

Characteristics of individual and combined SSR markers and observed polymorphisms. Total, specific and shared alleles, polymorphic information content (PIC), probability identity (PI), partial of total genetic diversity (GST), genetic differentiation (Fst) among populations, gene flow (Nm)

| Locus name | Haplotypes (Specific alleles) in ... | Shared alleles | Total alleles | PIC | PI | Fst | Gst | Nm | Total haplo-types | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SJ 1 n = 52 | SJ 2 n = 50 | SJ 3 n = 50 | SJ 4 n = 19 | SJ 5 n = 57 | SJ 6 n = 23 | |||||||||

| mEgCIR3328 | 7(1) | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 5(1) | 6 | 8 | 0.80 | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 0.62 | 21 |

| mEgCIR3362 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.78 | 11 |

| mEgCIR3382 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 14 |

| mEgCIR2600 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3(1) | 5 | 3(1) | 5 | 7 | 0.81 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 17 |

| mEgCIR2427 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.50 | 16 |

| mEgCIR3785 | 3 | 3(1) | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.87 | 8 |

| mEgCIR3607 | 6 | 6 | 6(1) | 1 | 5(1) | 5(2) | 4 | 8 | 0.83 | 0.36 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 19 |

| mEgCIR0802 | 4 | 6 | 5(1) | 1(1) | 4 | 3(1) | 5 | 8 | 0.84 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.26 | 16 |

| mEgCIR3693 | 3(1) | 3(1) | 3 | 6(1) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 0.71 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 11 |

| mEgCIR2569 | 3 | 2(1) | 5(1) | 4 | 4(1) | 4 | 3 | 6 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 12 |

| mEgCIR0788 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 16 |

| mEgCIR0894 | 6(1) | 7(1) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 13 |

| mEgCIR2422 | 2 | 2 | 4(1) | 3 | 3 | 1(1) | 3 | 5 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 1.10 | 7 |

| mEgCIR3683 | 3(1) | 2(1) | 4 | 1 | 3(1) | 5(1) | 3 | 7 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 11 |

| mEgCIR3544 | 3(1) | 3 | 3 | 3(1) | 4(2) | 3 | 3 | 7 | 0.73 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 13 |

| mEgCIR3775 | 5 | 1 | 3(1) | 2 | 7 | 3(1) | 3 | 5 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.55 | 11 |

| mEgCIR3428 | 2(1) | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 6 |

| mEgCIR3533 | 1 | 6(1) | 4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.09 | 12 |

| mEgCIR3392 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0.39 | 0.74 | –0.11 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 6 |

| Total (SA) | (6) | (6) | (5) | (4) | (5) | (8) | 76 | 110 | 12.6 | 6.97 | 7.20 | 8.83 | 240 | |

| Tot com HT | 52 | 50 | 44 | 17 | 55 | 22 | 240 | |||||||

| Tot com SA | 47 | 49 | 49 | 19 | 57 | 23 | 244 | |||||||

| Mean | 5.8 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.465 | 12.6 | |||||||

* Tot com HT = Total haplotypes of all combined SSR.

* Tot com SA = Total haplotypes for combined specific SSR alleles.

In general, the molecular markers used in this study were very informative with an average PIC value of 65%. The highest PIC value was observed for SSR mEgCIR0802 (0.844) and the less informative SSR was mEgCIR3392 (0.389). Only four out of 19 loci have PIC values below 50%. The probability of identity (PI) was calculated to quantify the ability of an SSR to distinguish between two individuals. SSR marker mEgCIR3328 was very informative, with a high PIC value as well. The smallest PI value of 0.74 was observed for SSR mEgCIR3392.

With respect to the power of discrimination, a total of 76 alleles out of the 110 SSR alleles were observed in more than one population (shared alleles, 68.5%). Among them, five SSR markers with a total of 24 alleles revealed only shared alleles (mEgCIR3392, mEgCIR3362, mEgCIR3382, mEgCIR0788 and mEgCIR2427). A total of thirty four alleles (31.5%) revealed population specific SSR alleles, which were absent in all other populations, but generally not present in all accessions of the target population. Three SSR markers revealed population specific alleles only for one population (mEgCIR3428 for SJ1, mEgCIR3785 and mEGCIR3533 for SJ2). The other 11 SSRs showed specific alleles in two to four populations. Combinations of population specific SSR alleles could be used to identify specific haplotypes in each population. They could be considered as significant markers, since most of them showed values above 0.25 in two approaches for measuring genetic differentiation among populations (GST and FST). In both cases, the average degree of differentiation surpassed 0.36, indicating high genetic divergence among SJ origins. Only three markers (mEgCIR3785, mEgCIR3362 and mEgCIR2422) revealed a lower GST value. This low genetic differentiation effect is also reflected for these three loci in high gene flow (Nm) values, but does not affect the average Nm value of 0.47, which is considered as low for the transfer of genetic variation (Godt et al. 2005).

The combination of all alleles of all SSR loci (that is, 110 total alleles) generated a total of 240 haplotypes distinguishing all accessions from populations SJ1 and SJ2 (see row “Tot com HT” in Table 3). A total of 244 haplotypes were generated for the combination of individual specific alleles per population (that is, 34 specific alleles). In this case all accessions from populations SJ4, SJ5 and SJ6 could be distinguished (see row “Tot com SA” in Table 3). For the other populations SJ1, SJ2, SJ3 a total of five, one and one uninformative haplotypes of the type “0 0 0 0 ....” remained, respectively. Supplemental Table 1 shows in detail all haplotypes estimation.

Genetic variability and differentiation

The genetic diversity was evaluated for each population. Table 4 summarizes the results. The average number of alleles per locus (A) was 2.41 across population, ranging from 1.79 for the lowest number of alleles in population SJ4 to 2.63 for the highest in populations SJ2 and SJ5. Population SJ4 revealed also the lowest percentage of polymorphic loci (P = 64%), while the other populations revealed P values of 95% or above. Based on the observed P values, the 19 loci could identify a unique individual with around 90% probability on average (Table 4). The set of SSR markers used in the analysis revealed more allelic polymorphisms in all populations than the expected mean Ae = 1.89 based on the observed heterozygosity. The observed heterozygosity (Ho) ranged between 0.301–0.486 and the expected heterozygosity (He) ranged between 0.254 and 0.469. In three populations, the value of He is higher than the Ho with positive Fis values (Ghana, Ekona and Dami) indicating a deficit of heterozygotic individuals. In the other three populations (Nigeria, Avros and Yangambi), Ho was higher than He showing more diversity and no deficit of heterozygosity.

Table 4.

Genetic variability parameters of the populations. Average number of alleles per population (A), average number of effective alleles (Ae), percentage of polymorphic loci (P), observed heterozygosity (Ho), Hardy-Weinberg expected heterozygosity (He), inbreeding coefficient within individuals (Fis)

| Pop | Na | A | Ae | P | Ho | He | Fis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SJ1 | 52 | 2.53 | 2.05 | 95% | 0.49 | 0.47 | –0.036 |

| SJ2 | 50 | 2.63 | 2.03 | 95% | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.018 |

| SJ3 | 50 | 2.47 | 1.96 | 95% | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.123 |

| SJ4 | 19 | 1.79 | 1.48 | 64% | 0.30 | 0.25 | –0.185 |

| SJ5 | 57 | 2.63 | 1.93 | 90% | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.135 |

| SJ6 | 23 | 2.42 | 1.91 | 100% | 0.47 | 0.45 | –0.045 |

| Mean | 2.41 | 1.89 | 90% | 0.408 | 0.415 | 0.002 |

a Number of individuals in the population.

The genetic differentiation between populations is shown in Table 5. The average genetic diversity among groups (HS) and total genetic diversity (HT) was 0.41 and 0.68, respectively, indicating that accessions from each origin contributed notably to the increase in total genetic diversity. The average genetic diversity among subgroups (DST) of 0.54 reflects high variability within groups. The analysis shows also a high coefficient of genetic differentiation (GST and FST values). These values were almost the same (around 0.38) between populations. The distribution of each group within populations was measured by inbreeding coefficient (GIS). This value was very low and close to zero, but positive and significant 0.03 (p < 0.001) and showed some deficiency of heterozygotes relative to Hardy-Weinberg expectations. The GST is also used as indirect estimator of the gene flow (Nm). The value was low 0.423 and very similar to the estimated gene flow based on polymorphic alleles (0.465). This trend is also reflected in the F statistics, showing significant values of 0.37, 0.46 and 0.14 for inbreeding coefficients of FST, FIT and FIS, respectively.

Table 5.

Genetic differentiation based on Nei’s diversity, differentiation coefficients and F-statistics. Average genetic diversity within groups (HS), total genetic diversity (HT), average genetic diversity among subgroups (DST), coefficient of genetic differentiation (GST), inbreeding coefficient (GIS), gene flow (Nm)

| HS | HT | DST | GST | GIS | Nm | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.423 | ||

| FST | 0.372* | ||||||

| FIT | 0.461* | ||||||

| FIS | 0.142* |

* p = 0.001 statistical significance level.

Genetic structure analysis

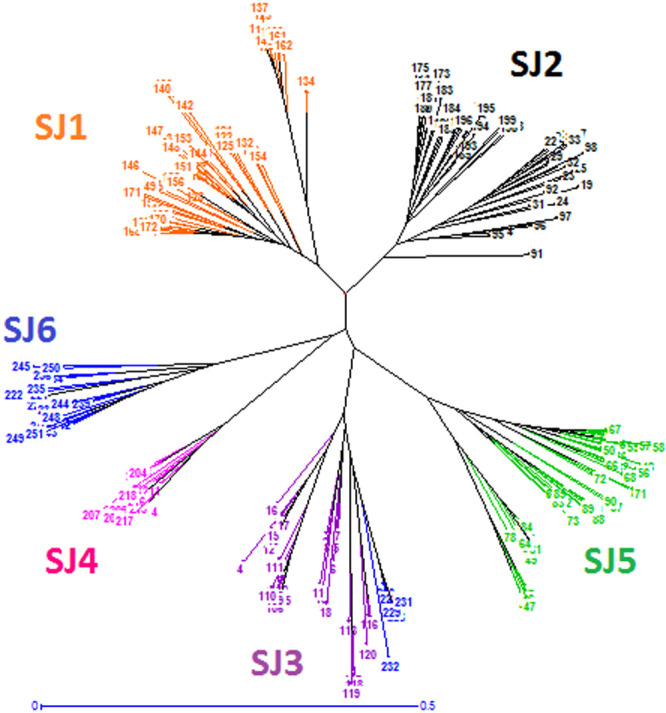

The phylogenetic relationships between populations are shown in the dendrogram of Fig. 2. This dendrogram was calculated based on Jaccard´s similarity coefficient and using UPGMA and the Neighbor joining algorithm. Three main clusters divided in six sub-clusters are visible. One of the main clusters separated specially the West African origins (Nigeria and Ghana) and the other two clusters matched the origins of the central belt (Congo and Cameroon). The coefficients of similarity varied between 0.263 and 1.000 in all analyzed samples. The highest distance of 0.659 was observed between SJ1 and SJ2, while the lowest value of 0.334 was obtained between SJ1 and SJ6.

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-joining tree showing the phylogenetic relationships among the populations based on genetic distance data.

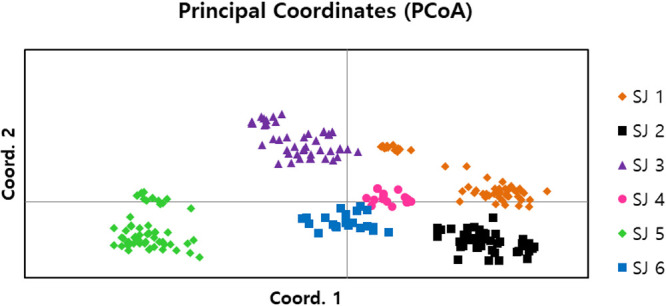

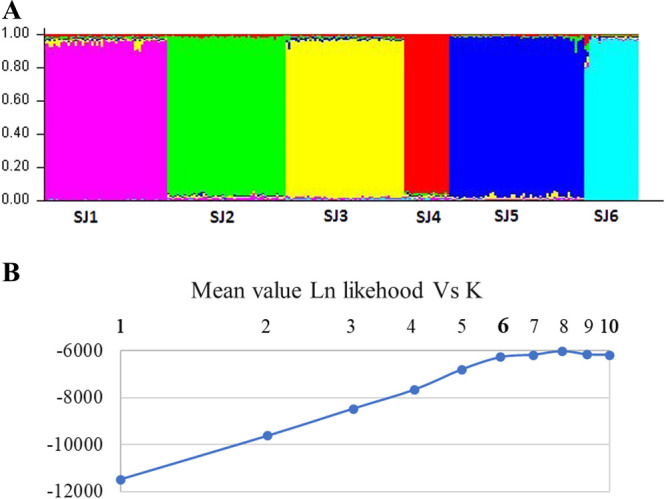

Also, a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was used for evaluating the phylogenetic relationship among population. The PCoA showed a significant grouping of the populations that were plotted into six subgroups (Fig. 3). The first and second coordinates explained 17.75 and 15.96% of the total variance, respectively. These results were in accordance with those of the AMOVA analysis (Table 6) where 38% of the total variance was explained by the variation among populations based on the allelic distance matrix. However, the highest variance of 56% resulted from the variation within all individuals. An additional analysis with Structure software confirmed six components in our set of individuals (Fig. 4A) and validated the K value of 6 using Structure harvester (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

Two-dimensional plot of principal coordinates analysis (PCoA), depicting the genetic relatedness among six populations.

Table 6.

Results of the Analysis of Molecular Variance, AMOVA

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among populations | 5 | 994.788 | 198.958 | 2.388 | 38% |

| Among individuals | 245 | 1048.819 | 4.281 | 0.385 | 6% |

| Within individuals | 251 | 881.000 | 3.510 | 3.510 | 56% |

| Total | 501 | 2924.608 | 6.283 | 100% |

Fig. 4.

Population structure results. (A) Distruct plots for K = 6. Overall proportion of memberships of the samples in each of the 6 clusters. (B) Structure harvester result for optimal K. X axis displays units in logarithmic scale base 10 showing the stabilization at K = 6.

Discussion

Large efforts were made in the past by classical breeders to select the best elite trees, to establish comprehensive breeding programs and to obtain improved genetic materials. In this context, molecular approaches are becoming important tools to support trustworthy variety production (Kumar et al. 2018). We have used microsatellite markers to investigate the level of genetic diversity, the distribution of genetic variation and the genetic relatedness in DxP palms of different parental Pisifera origins. The selected SSRs were highly informative and have been widely applied in previous studies not only for diversity analyses, but also for fingerprinting, for linkage map construction (Billotte et al. 2010, Seng et al. 2011, Ting et al. 2013) and for analyzing associations between microsatellite variation and interesting characters in oil palm, such as oil production and vegetative traits (Hama-Ali et al. 2015a, Jeennor and Volkaert 2014, Montoya et al. 2014, Xiao et al. 2014). Historically, SSR markers are considered as robust, since they are co-dominant, highly polymorphic, show a good reproducibility and particularly due to their simplicity of use (Collard et al. 2005). Moreover, they map in different genetic backgrounds to the same genome location and some can be even transferred to related species (Arias et al. 2015, Ithnin et al. 2017, Zaki et al. 2012). Elaies guineensis SSRs markers for example were successfully tested in a diversity study of the closely related species Elaeis oleifera, the American oil palm. Nowadays, there are modern molecular marker databases, which are highly informative and have free access, such as OpSatdb from the Indian Institute of Oil Palm Research (Babu et al. 2019, https://ssr.icar.gov.in/index.php). This database includes beside genomic SSRs also genic SSR markers (EST-SSR). Other genomic resources represent for example PalmXplore from Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) with exhaustive information about palm oil biosynthesis genes, resistance genes and other genes of interest, including the whole genome sequence of this tropical palm (Sanusi et al. 2018, http://palmxplore.mpob.gov.my/palmXplore).

In our case, the use of highly polymorphic SSRs from Billotte et al. (2005) was sufficient for the variability study in our set of analyzed samples. Our set of SSR markers revealed on average 5, 8 alleles per locus. This number is lower compared for example, with the 13.1 alleles/locus obtained by Bakoume et al. (2015). However, this result was obtained in a much larger set of populations. Higher values were also obtained in other studies, where large germplasm collections from Asia, Africa and Latin America were characterized (Cochard et al. 2009). The number of polymorphic alleles per locus is obviously influenced by the number of analyzed samples and the number of origins.

Our batch of SSR markers revealed a high level of polymorphic information content (PIC) of up to 85%, higher than that obtained with other kind of markers such as AFLP or isoenzymes (Barcelos et al. 2002, Purba et al. 2000). It is comparable with the PIC values of other studies in oil palm using similar sources of markers evaluated on six different crosses (Budiman et al. 2019), as well as with similar plant material origins (Arias et al. 2014).

With respect of the power of discrimination, the markers can distinguish a unique individual with more than 95% of probability and interestingly, fourteen of them can detect specific patterns in the DxP varieties, representing informative loci. Chee et al. (2015) used microsatellites as a discrimination tool applying a set of only eleven polymorphic SSRs to separate related oil palm populations. Other SSR fingerprint evaluations were used to perform parentage analysis and for solving illegitimacy issues in commercial materials and breeding programs. Thongthawee et al. (2010) could reach a level of less than one percentage of planting errors with a combination of only four SSR markers and Hama-Ali et al. (2015b) reported sixteen useful microsatellites for detecting illegitimacy in oil palm. Both authors proposed the use of some additional microsatellites markers for the detection of pollination errors. Nowadays, legitimacy in breeding and genetic diversity analyses are also performed with high throughput markers such as SNPs were required (Cros et al. 2017, Teh et al. 2019, Xia et al. 2019).

In this context, the distinction of all accessions belonging to each population was one aim of this study, in view of seed certification or for solving legitimacy issues. In principle this purpose has been achieved. With respect to the combination of alleles from all SSR loci (110), the 11 repeated haplotypes, ordered in 8 groups of 2 or 3 repeated haplotypes were detected. Fortunately, the accessions of each group belong to the same population in each case. In this way, it is possible to assign unambiguously all accessions from each population to the corresponding variety. With respect to the combination of all population specific SSR alleles (34), only seven accessions in three populations cannot be distinguished. However, considering that for practical applications not single alleles, but whole SSR primers will be used, all previously unidentified samples will disappear. This option requires the use of only four to maximal eight SSR primer combinations (PC) instead of the 19 PC from the previous approach, following the trend of effective reduction of SSR markers mentioned by authors above.

The high genetic divergence at locus level was reflected by GST and FST values reaching 0.3, together with a low gene flow for the transfer of genetic variation among populations. This trend was confirmed by the Nei’s diversity index and by F statistics. Similar values were reported in previous authors with material from the central belt of Africa (Arias et al. 2014, Hayati et al. 2004), suggesting strong differentiation in the populations mainly due to larger distances between places and limited pollen and seed dispersion via weevil and animals/humans, respectively (Corley and Tinker 2016). In all mentioned studies, low gene flow supported this level of differentiation as in our study.

For Ghana, Ekona and Dami, the value of He is higher than the Ho with positive Fis values, indicating a deficit of heterozygotic individuals. This plant material shows some level of inbreeding as reported also by Bakoume et al. (2015) or the presence of null alleles in the population that could not be detected (Arias et al. 2013). For Nigeria, Avros and Yangambi, an excess of heterozygosity was observed indicating more variability in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Historically, these origins were more diverse and Avros or Yangambi palms have been used commonly as Pisifera pollen donors (Alvarado et al. 2010, Barcelos et al. 2015). Nigeria is also considered as the center of diversity of the African oil palm (Maizura et al. 2006). Although we saw some differences among origins in the Fis values, low but significant inbreeding coefficients were observed. Actually, some level of inbreeding was expected giving the fact that less heterogenic and improved Deli mothers were used to produce our set of samples, as also mentioned by Cochard et al. (2009).

The major source of variation was observed between individuals, followed by 38% variation among populations. This AMOVA results evidenced a differentiation between origins in the present study suggesting certain genetic structure. Both, similarity coefficients and cluster analyses, as well as genetic relatedness based on principal coordinates analyses, separated the samples in accordance with the six origins from which the parental lines were selected. In the case of PCoA, the variance of the first two coordinates distinguished six clusters explaining more than thirty percent of the total variation, in accordance with the AMOVA results. Our set of SSRs verified the six different origins of the Pisifera parents which were used to produce the DxP palms at a commercial scale. Other examples with similar clear clustering of African origins were also reported previously (Arias et al. 2014, Cochard et al. 2009). The structure of these 6 geographical origin was clearly validated by K = 6 subpopulations and confirmed again the used phenotypic selection strategy.

Nevertheless, it is convenient to screen additional SSR primers for simplifying the detection of the population to which an accession belongs, preferably with only one SSR PC. We provide our SSRs result that could be used or summed to other markers for future verification by other authors in terms of finding the best formula for identification. In the oil palm breeding, since the polymorphisms result from the Pisifera pollen donor and only a few palms are used as pollen donor, this reduced set of all Pisifera palms should be used for massive SSR screenings. In addition, also the set of accessions in this study should be increased for validating the results. As we show in the manuscript, the applicability for the breeding community can be not only for accession legitimacy of different populations but also for the germplasm management via genetic diversity certification.

Conclusion

The conclusions of this study can be summarized in three points: i) The use of microsatellites is a robust, feasible and trustful method for obtaining DNA fingerprints and for tracing the source of oil palm samples; ii) The molecular analysis validated the good phenotypic selection of breeding materials made by company breeders based only on phenotypic traits, matching with the arrangement as shown in Table 1; iii) SSR markers offer an important support for seed production by providing a molecular certification. SSRs give an improved value as a quality control for determining authenticity of materials or for solving legitimacy issues. The distinction of all accessions belonging to each population by SSR markers has been achieved. However, the screening of additional SSRs could improve this process and also the set of accessions should be increased for validating the results.

Author Contribution Statement

U.S. and J.H. are the main contributors of the paper. They were in charge of the project design, laboratory analysis, results evaluation and the manuscript writing.

P.E., N.I., F.W. and B.S. were involved in plant material management, data analysis and writing contributions.

E.R., Z.S and D.A. are the responsible for the project management and were involved in the results analysis, manuscript revision/writing and the contribution of applicability objectives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the valuable work of all people involved in this study from the field to the laboratory. This study is integrated in the “Parent Analysis Project” of the Molecular Laboratory of PT. Sampoerna Agro. Tbk (Palembang, Indonesia).

Literature Cited

- Alvarado, A., Escobar R. and Peralta F. (2010) El programa de mejoramiento genético de palma aceitera de ASD Costa Rica y su contribución a la industria. ASD Oil Palm Papers 35: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, D., Montoya C. and Romero H. (2013) Molecular characterization of oil palm Elaeis guineensis Jacq. materials from Cameroon. Plant Genet. Resour. 11: 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, D., Ochoa I., Castro F. and Romero H. (2014) Molecular characterization of oil palm Elaeis guineensis Jacq. of different origins for their utilization in breeding programmes. Plant Genet. Resour. 12: 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, D., González M., Prada F., Ayala-Diaz I., Montoya C., Daza C. and Romero H.M. (2015) Genetic and phenotypic diversity of natural American oil palm (Elaeis oleifera (H.B.K.) Cortés) accessions. Tree Genet. Genomes 11: 122. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, K., Mary Rani K.L., Sahu S., Mathur R.K., Kumar N., Ravichandran G., Anitha P. and Bhagya H.P. (2019) Development and validation of whole genome-wide and genic microsatellite markers in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.): First microsatellite database (OpSatdb). Sci. Rep. 9: 1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakoume, C., Wickneswari R., Siju S., Rajanaidu N., Kushairi A. and Billotte N. (2015) Genetic diversity of the world’s largest oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) field genebank accessions using microsatellite markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 62: 349–360. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelos, E., Amblard P., Berthaud J. and Seguin M. (2002) Genetic diversity and relationship in American and African oil palm as revealed by RFLP and AFLP molecular markers. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 37: 1105–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelos, E., Rios S.D.A., Cunha R.N.V., Lopes R., Motoike S.Y., Babiychuk E., Skirycz A. and Kushnir S. (2015) Oil palm natural diversity and the potential for yield improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 6: 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirnaert, A. and Vanderweyen R. (1941) Contribution a l’étude génétique et biométrique des variétés d’Elaeis guineensis Jacq. Publ. Inst. Nat. Etude agron. Congo Belge. Ser. Sci. 27: 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Billotte, N., Marseillac N., Risterucci A.M., Adon B., Brottier P., Baurens F.C., Singh R., Herrán A., Asmady H., Billot C.et al. (2005) Microsatellite-based high density linkage map in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 110: 754–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billotte, N., Jourjon M.F., Marseillac N., Berger A., Flori A., Asmady H., Adon B., Singh R., Nouy B., Potier F.et al. (2010) QTL detection by multi-parent linkage mapping in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 120: 1673–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody, J.R. and Kern S.E. (2004) Sodium boric acid: a Tris-free, cooler conductive medium for DNA electrophoresis. BioTechniques 36: 214–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman, L.F., Apriyanto A., Pancoro A. and Sudarsono S. (2019) Genetic diversity analysis of Tenera × Tenera and Tenera × Pisifera Crosses and D self of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) parental populations originating from Cameroon. Biodiversitas 20: 937–949. [Google Scholar]

- Chee, W.W., Jit T.C., Kien W.C., Mayes S., Singh R. and Chin S. (2015) Development of an effective SSR-based fingerprinting system for commercial planting materials and breeding applications in oil palm. J. Oil Palm Res. 27: 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cheyns, E. and Rafflegeau S. (2005) Family agriculture and the sustainable development issue: possible approaches from the African oil palm sector. The example of Ivory Coast and Cameroon. OCL - Oilseeds and fats, Crops and Lipids 12: 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cochard, B., Adon B., Rekima S., Billotte N., de Chenon R.D., Koutou A., Nouy B., Omoré A., Purba R.A., Glazsmann J.C.et al. (2009) Geographic and genetic structure of African oil palm diversity suggests new approaches to breeding. Tree Genet. Genomes 5: 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Collard, B.C.Y., Jahufer M.Z.Z., Brouwer J.B. and Pang E.C.K. (2005) An introduction to markers, quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping and marker-assisted selection for crop improvement: The basic concepts. Euphytica 142: 169–196. [Google Scholar]

- Corley, R.H.V. and P.B. Tinker (2016) The Oil Palm. Hoboken. NJ: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cros, D., Denis M., Bouvet J.M. and Sánchez L. (2015) Long-term genomic selection for heterosis without dominance in multiplicative traits: case study of bunch production in oil palm. BMC Genomics 16: 651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cros, D., Bocs S., Riou V., Ortega-Abboud E., Tisné S., Argout X., Pomies V., Nodichao L., Lubis Z., Cochard B.et al. (2017) Genomic preselection with genotyping-by-sequencing increases performance of commercial oil palm hybrid crosses. BMC Genomics 18: 839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cros, D., Tchounke B. and Nkague-Nkamba L. (2018) Training genomic selection models across several breeding cycles increases genetic gain in oil palm in silico study. Mol. Breed. 38: 89. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, D.A. and vonHoldt B.M. (2012) STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 4: 359–361. [Google Scholar]

- Godt, M.J.W., F. Caplow and J.L. Hamrick (2005) Allozyme diversity in the federally threatened golden paintbrush, Castilleja levisecta (Scrophulariaceae). pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hama-Ali, E.O., Panandam J.M., Tan S.G., Alwee S.S.R.S., Sheong T.J., Ling H.C., Namasivayam P. and Peng H.B. (2015a) Association between basal stem rot disease and simple sequence repeat markers in oil palm, Elaeis guineensis Jacq. Euphytica 202: 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hama-Ali, E.O., Alwee S.S.R.S., Tan S.G., Panandam J.M., Ling H.C., Namasivayam P. and Peng H.B. (2015b) Illegitimacy and sibship assignments in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) half-sib families using single locus DNA microsatellite markers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 42: 917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick, J.L. and Godt M.J.W. (1996) Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 351: 1291–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Hayati, A., Wickneswari R., Maizura I. and Rajanaidu N. (2004) Genetic diversity of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) germplasm collections from Africa: implications for improvement and conservation of genetic resources. Tree Genet. Genomes 108: 1274–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ithnin, M., Teh C.K. and Ratnam W. (2017) Genetic diversity of Elaeis oleifera (HBK) Cortes populations using cross species SSRs: implication’s for germplasm utilization and conservation. BMC Genet. 18: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeennor, S. and Volkaert H. (2014) Mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for oil yield using SSRs and gene-based markers in African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.). Tree Genet. Genomes 10: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakatsu, T. and Ecker J.R. (2019) Diversity and dynamics of DNA methylation: epigenomic resources and tools for crop breeding. Breed. Sci. 69: 191–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.N., B.K. Babu, R.K. Mathur and D. Ramajayam (2018) Genetic engineering of oil palm. In: Gyana Ranjan Rout and K.V. Peter (eds.) Genetic Engineering of Horticultural Crops, Academic Press, pp. 169–191. [Google Scholar]

- Maizura, I., Rajanaidu N., Zakri A.H. and Cheah S.C. (2006) Assessment of genetic diversity in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 53: 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Marchal, A., Legarra A., Tisné S., Carasco-Lacombe C., Manez A., Suryana E., Omoré A., Nouy B., Durand-Gasselin T., Sanchez L.et al. (2016) Multivariate genomic model improves analysis of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) progeny tests. Mol. Breed. 36: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, C., Lopes R., Flori A., Cros D., Cuellar T., Summo M., Espeout S., Rivallan R., Risterucci A.M., Bittencourt D.et al. (2013) Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) analysis of palm oil fatty acid composition in an interspecific pseudo-backcross from Elaeis oleifera (H.B.K) Cortés and oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.). Tree Genet. Genomes 9: 1207–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, C., Cochard B., Flori A., Cros D., Lopes R., Cuellar T., Speout S., Syaputra I., Villeneuve P., Pina M.et al. (2014) Genetic architecture of palm oil fatty acid composition in cultivated oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) compared to its wild relative E. oleifera (H.B.K) Cortés. PLoS ONE 9: e95412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcillo, F., Cros D., Billotte N., Ngando-Ebongue G.F., Domonhédo H., Pizot M., Cuéllar T., Espéout S., Dhouib R., Bourgis F.et al. (2013) Improving palm oil quality through identification and mapping of the lipase gene causing oil deterioration. Nat. Commun. 4: 2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M. (1973) Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70: 3321–3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M. (1977) F-statistics and analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Ann. Hum. Genet. 41: 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoye, M.N., Bakoume C., Uguru M.I. and Singh R. (2018) Genetic diversity and relatedness of oil palm progenies determined by microsatellite and agronomic markers. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 17: 614–625. [Google Scholar]

- Ong-Abdullah, M., Ordway J.M., Jiang N., Ooi S.E., Kok S.Y., Sarpan N., Azimi N., Hashim A.T., Ishak Z., Rosli S.K.et al. (2015) Loss of Karma transposon methylation underlies the mantled somaclonal variant of oil palm. Nature 525: 533–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Castillo, C., Chalmers K.J., Waugh R. and Powell W. (1994) Detection of genetic diversity and selective gene introgression in coffee using RAPD markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 87: 934–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall, R. and Smouse P.E. (2012) GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics 28: 2537–2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier, X. and J.P. Jacquemoud-Collet (2006) DARwin software. https://darwin.cirad.fr/

- Pritchard, J.K., Stephens M. and Donnelly P. (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155: 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purba, A.R., Noyer J.L., Baudouin L., Perrier X., Hamon S. and Lagoda P.J.L. (2000) A new aspect of genetic diversity of Indonesian oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) revealed by isoenzyme and AFLP markers and its consequences for breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 101: 956–961. [Google Scholar]

- Purwoko, D., Cartealy I.C., Tajuddin T., Dinarti D. and Sudarsono S. (2019) SSR identification and marker development for sago palm based on NGS genome data. Breed. Sci. 69: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanusi, N.S.N.M., Rosli R., Halim M.A.A., Chan K.L., Nagappan J., Azizi N., Amiruddin N., Tatarinova T.V. and Low E.T.L. (2018) PalmXplore: oil palm gene database. Database (Oxford) 2018: bay095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng, T.Y., Saad S.H.M., Chin C.W., Ting N.C., Singh R.S.H., Zaman F.Q., Tan S.G. and Alwee S.S.R.S. (2011) Genetic linkage map of a high yielding FELDA Deli × Yangambi oil palm cross. PLoS ONE 6: e26593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, K. (2017) Pemuliaan kelapa sawit, Untuk Produksi Benih Unggul: Tanaman Pendek, Kompak, dan Minyak Tak Jenuh Tinggi. Plantaxia, first edition: 15. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R., Nagappan J., Tan S.G., Panandam J.M. and Cheah S.C. (2007) Development of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers for oil palm and their application in genetic mapping and fingerprinting of tissue culture clones. Asia-Pac. J. Mol. Biol. Biotechnol. 15: 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R., Low E.T.L., Ooi L.C.L., Ong-Abdullah M., Ting N.C., Nagappan J., Nookiah R., Amiruddin M.D., Rosli R., Manaf M.A.A.et al. (2013a) The oil palm SHELL gene controls oil yield and encodes a homologue of SEEDSTICK. Nature 500: 340–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R., Ong-Abdullah M., Low E.T.L., Manaf M.A.A., Rosli R., Nookiah R., Ooi L.C., Ooi S.E., Chan K.L., Halim M.A.et al. (2013b) Oil palm genome sequence reveals divergence of interfertile species in Old and New worlds. Nature 500: 335–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R., Low E.T.L., Ooi L.C.L., Ong-Abdullah M., Nookiah R., Ting N.C., Marjuni M., Chan P.L., Ithnin M., Manaf M.A.A.et al. (2014) The oil palm VIRESCENS gene controls fruit colour and encodes a R2R3-MYB. Nat. Commun. 5: 4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin, M. (1985) Rare alleles as indicators of gene flow. Evolution 39: 53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teh, C.K., Lee H.L., Abidin H., Ong A.L., Mayes S., Chew F.T. and Appleton D. (2019) A practical genome-enabled legitimacy assay for oil palm breeding and seed production. BMC Plant Biol. 19: 470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting, N.C., Jansen J., Nagappan J., Ishak Z., Chin C.W., Tan S.G., Cheah S.C. and Singh R. (2013) Identification of QTLs associated with callogenesis and embryogenesis in oil palm using genetic linkage maps improved with SSR markers. PLoS ONE 8: e53076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting, N.C., Jansen J., Mayes S., Massawe F., Sambanthamurthi R., Ooi L.C.L., Chin C.W., Arulandoo X., Seng T.Y., Alwee S.S.R.S.et al. (2014) High density SNP and SSR-based genetic maps of two independent oil palm hybrids. BMC Genomics 15: 309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongthawee, S., Tittinutchanon P. and Volkaert H. (2010) Microsatellites for parentage analysis in an oil palm breeding population. Thai J. Genet. 3: 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S. (1965) The interpretation of population structure by F‐statistics with special regard to systems of mating. Evolution 19: 395–420. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, W., Luo T., Zhang W., Mason A.S., Huang D., Huang X., Tang W., Dou Y., Zhang C. and Xiao Y. (2019) Development of high-density SNP markers and their application in evaluating genetic diversity and population structure in Elaeis guineensis. Front. Plant Sci. 10: 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y., Zhou L., Xia W., Mason A.S., Yang Y., Ma Z. and Peng M. (2014) Exploiting transcriptome data for the development and characterization of gene-based SSR markers related to cold tolerance in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis). BMC Plant Biol. 14: 384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, N.M., Singh R., Rosli R. and Ismail I. (2012) Elaeis oleifera genomic-SSR markers: exploitation in oil palm germplasm diversity and cross-amplification in Arecaceae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13: 4069–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.