Abstract

Background:

The eating in the absence of hunger (EAH) experimental paradigm measures intake of highly palatable, highly processed foods when sated. However, no studies have examined EAH in pregnant women.

Objective:

The objectives were to investigate whether EAH in pregnant women differs by level of food processing and to examine relationships of EAH with hedonic hunger, addictive-like eating, and impulsivity.

Design:

EAH was assessed in a counterbalanced crossover feeding substudy in which participants completed two free access eating occasions following a standardized meal during their 2nd pregnancy trimester. Hedonic hunger (Power of Food Scale, PFS), addictive-like eating (modified Yale Food Addiction Scale, m-YFAS), and impulsivity (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-15, BIS) were assessed by self-report in early pregnancy.

Participants/settings:

Data were collected from March 2015 through September 2016 from a subsample of participants (n=46) enrolled at ≤12 weeks gestation in an observational, prospective cohort study (the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study) in North Carolina.

Intervention:

Participants were presented with highly processed (HP) and minimally processed (MP) foods in two separate assessments.

Main outcome measures:

Energy intake (EAH-kcal) and percent consumed (EAH-%, calculated as 100[amount consumed (g) /amount served (g)]) was measured overall and separately for sweet and savory foods.

Statistical analyses performed:

Linear mixed models estimated the effect of condition on EAH. PFS, m-YFAS, and BIS and their interaction terms were examined separately.

Results:

EAH-% was similar across conditions (16.3% ± 1.1% HP versus 17.9% ± 1.2% MP, p = 0.76), resulting in 338.5 ± 34.2 kcal greater energy intake in the HP versus MP condition (p < 0.001). PFS was not significantly associated with EAH; m-YFAS was positively associated with EAH-kcal and EAH-% of savory foods, and BIS was positively associated with EAH-kcal and EAH-% overall, and with EAH-% of sweet foods (p < 0.05). There was little evidence of an interaction of BIS with PFS or m-YFAS.

Conclusions:

EAH in pregnant women occurs for both highly processed and minimally processed foods and correlates positively with self-reported addictive-like eating, but not hedonic hunger. Impulsivity did not modify associations of addictive-like eating with EAH in this sample.

Keywords: eating in the absence of hunger, diet quality, pregnancy, appetite, food intake, impulsivity, food addiction, hedonic hunger, crossover study

INTRODUCTION

Dietary intake during pregnancy is characterized by insufficient intake of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and seafood/plant protein, and excessive intake of sodium and discretionary foods that contribute mostly energy and minimal nutritional value1,2. Additionally, women commonly exceed recommendations for gestational weight gain3, likely reflecting excessive energy intakes4,5. Understanding determinants of dietary intake during pregnancy is critical given the implications of diet for numerous maternal and child health outcomes6.

In the general population, the sensitivity of the brain reward system to food cues (food reward sensitivity) has been identified as an important contributor to reward-related eating behaviors such as hedonic hunger7,8, the appetitive motivation for food consumption in the absence of metabolic need9, and addictive-like eating, the pathological dependence on food intake aligned with substance dependence diagnostic criteria10. Reward-related eating behaviors may incentivize individuals to prefer and overconsume highly palatable foods, typically described as highly processed, energy dense foods made with added sugar, fat, and sodium11–16. Highly processed foods have also been associated with addictive properties17 and addictive-like eating12. Such preferences may, in turn, contribute to eating beyond energy requirements18,19. In young adults, higher self-reported hedonic hunger, as measured by the Power of Food Scale (PFS)20,21, is associated with greater frequency of non-hunger-related snacking22, and with more frequent intake of discretionary foods including sweets and salty snacks23. Similarly, addictive-like eating, as measured by the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS), is associated with a greater proportion of intake from highly processed foods24 and more frequent intake of nutrients found in highly processed foods (e.g., trans fat, added sugar)25. Research in this area has been predominantly observational and cross-sectional, focusing on how reward-related eating relates to intake of highly palatable and processed foods. There is currently no experimental evidence to inform whether reward-based eating extends to minimally processed foods, for which palatability is not enhanced by added sugar, fat, or sodium (but may undergo some types of processing such as removal of inedible portions or processing to meet safety regulations)25,26.

Evidence in non-pregnant adults further suggests that impulsivity, the tendency to act on impulse with little consideration for consequences27, may interact with reward-related eating tendencies to impact eating behavior. Greater impulsivity, an indicator of lower self-control, is positively associated with engaging in rewarding behaviors in general28,29, and specifically with food intake30–33. Additionally, greater self-control can attenuate the positive association of reward-related eating with food intake11, while greater impulsivity is associated with enhanced behavioral response to food cravings34 and external cues33. However, little is known regarding the relationship of impulsivity with eating behavior during pregnancy, when women often report relaxing efforts to control eating35,36 potentially due to emotional needs, pregnancy-related health considerations or increased food cravings37–40.

Understanding the impact of reward-based eating and impulsivity on eating behavior during pregnancy is critical for developing behavioral interventions to improve pregnancy diet quality41. To address this knowledge gap, this substudy used an eating in the absence of hunger (EAH) experimental paradigm to examine whether the level of food processing influences EAH in pregnant women, to investigate the independent relationships of self-reported reward-related eating (i.e., hedonic hunger and addictive-like eating) and impulsivity with EAH, and to test whether the association of EAH with reward-related eating becomes stronger as impulsivity increases (self-control decreases). The hypotheses were that (1) EAH would be greater in the presence of highly processed (HP) versus minimally processed (MP) foods, (2) self-reported reward-related eating and impulsivity would be positively associated with EAH, and (3) greater impulsivity would strengthen the association of reward-related eating with EAH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and recruitment

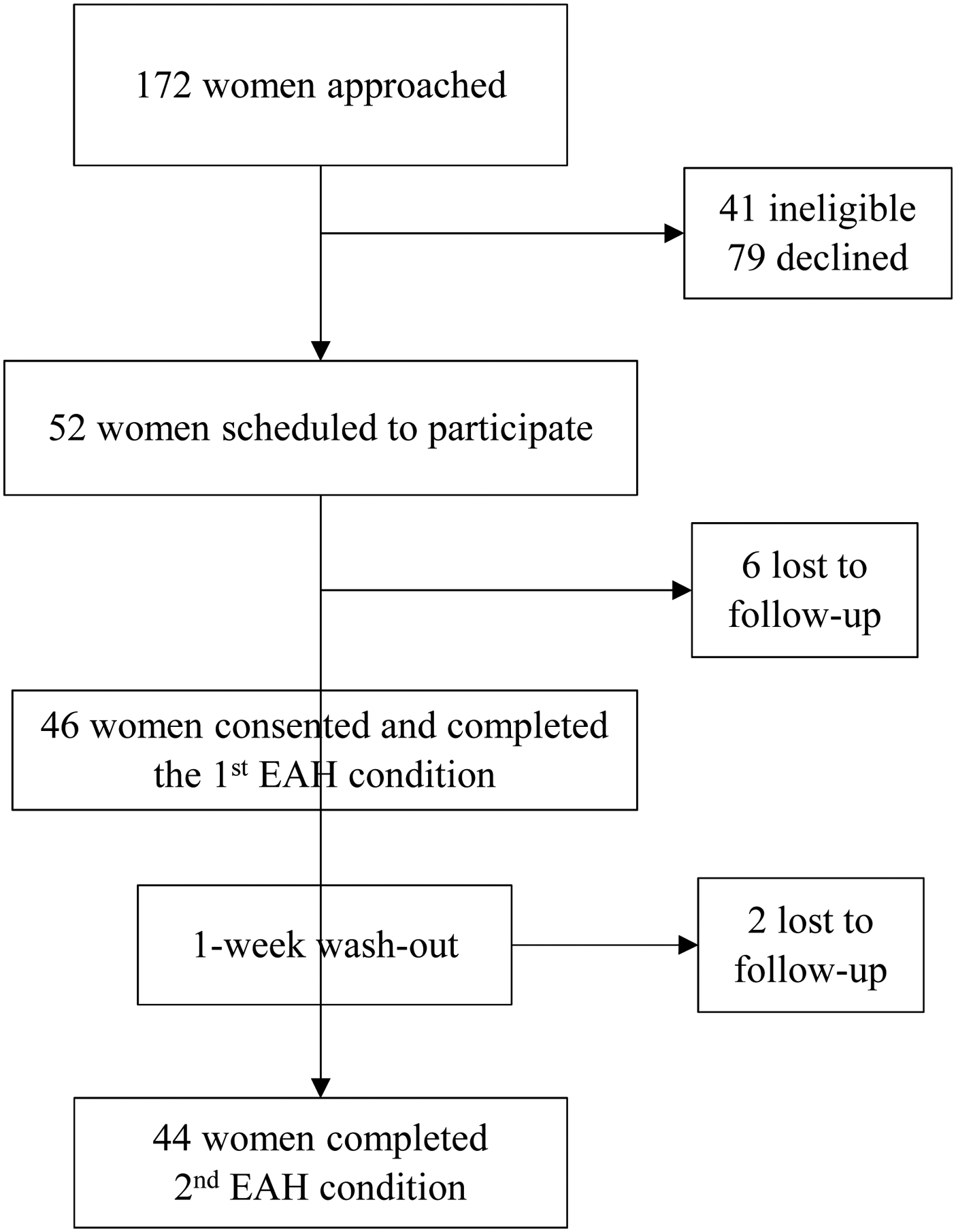

Participants for the substudy were recruited from women enrolled in the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study (PEAS), an observational prospective cohort study of women from early pregnancy (≤12 weeks gestation) through 1 year postpartum conducted from November 2014 through June 201842 (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02217462). Eligibility criteria for PEAS included uncomplicated singleton pregnancy, age ≥ 18 and < 45 years at screening, ability to provide informed consent, BMI ≥ 18.5, ability to complete assessments in English, internet and email access, and planning to deliver at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Women’s Hospital and to reside near the clinical site until 1 year postpartum. Exclusion criteria included pre-existing type 1 or type 2 diabetes, multiple pregnancy, participant-reported eating disorder, and any contraindicating medical or psychological condition or medications affecting diet or weight, e.g., serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Additional eligibility criteria for the EAH substudy included active participation in PEAS (completion of at least 75% of baseline surveys), ≥ 16 and < 27 weeks gestation, and willingness to consume all foods served in the protocol. The target sample size was 50 women. Of 172 women approached, 41 were deemed ineligible, 79 declined, 52 were scheduled to participate and assigned to treatment order, and 46 attended the first assessment and were enrolled; 44 women completed both EAH assessments (Figure 1). None of the participants had a gestational diabetes diagnosis at the time of the EAH assessments. There have been no comparable studies to facilitate a priori power calculations. The sample size was chosen based on similar studies assessing EAH in adults (e.g.,11). Post-hoc power calculations performed in StataSE version 14.243 indicate that for a paired t-test with a sample size of 44 and α = 0.05 there was 80% power to detect a standardized effect size = 0.42, which reflects a difference of 61 kcal between the high and minimally processed conditions. There were no differences in age (p = 0.55), BMI category (p = 0.58), household income-poverty ratio (p = 0.74), or race/ethnicity (p = 0.59) between EAH participants and non-participants within PEAS. All participants provided informed consent. Participants received $20 remuneration after completing the 1st EAH test condition and $30 after completing the 2nd EAH test condition. Procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram of 46 pregnant women in North Carolina participating in an Eating in the Absence of Hunger crossover substudy (March 2015 – September 2016) of the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study.

Experimental design and procedures

Women completed self-administered online surveys assessing reward-related eating and impulsivity in the first two pregnancy trimesters, and self-reported household income, household composition and race/ethnicity at baseline. The income-poverty ratio was calculated with respect to 2016 poverty thresholds44 accounting for household size and composition; greater values reflect higher income relative to the poverty threshold. Baseline age and gestational age were obtained from the electronic medical record. Early pregnancy BMI was calculated from height and weight measured at baseline using a wall-mounted stadiometer and calibrated scale to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg. Participants removed shoes, jackets, and extra clothing, and emptied pockets prior to weight measurements. Height and weight were measured in triplicate and the mean of the two closest measurements were used in analyses. Directly measured weight at the first prenatal visit was used since self-reported pre-pregnancy weight is prone to bias, especially in women with overweight and obesity45, and since measured first pregnancy weight is used for the basis of determining recommended gestational weight gain4.

Self-reported reward-related eating measures

The PFS20 was used to assess hedonic hunger, the appetitive motivation for palatable foods in the environment (Cronbach’s α = 0.82). Example items of this 18-item measure include: ‘If I see or smell a food I like, I get a powerful urge to have some’ and ‘It seems like I have food on my mind a lot;’ and ‘I think I enjoy eating a lot more than most other people’. Response options are on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = don’t agree at all to 5 = strongly agree). The total score is calculated as the mean of three component scores, which are calculated from the mean of responses to the relevant items21. Higher scores reflect greater responsiveness to foods in the environment. The psychometrics of the PFS have been described elsewhere20,21. PFS scores positively relate to food reinforcement value, neural response in brain regions implicated in reward and gustatory processing during food intake, and predicted increases of binge eating episodes over one year46.

The modified Yale Food Addiction Scale (m-YFAS, Cronbach’s α = 0.68) is a 9-item self-report measure of symptoms of addictive-like eating10. Questions, adapted from the Yale Food Addiction Scale, correspond to each of the seven substance dependence criteria in the DSM-IVTR47 plus two items assessing clinically significant impairment and distress. Example items include ‘I find myself consuming certain foods even though I am no longer hungry’ (response options range from 1 = never to 5 = 4 or more times per week or daily) and ‘I kept consuming the same types or amounts of food despite significant emotional and/or physical problems related to my eating’ (yes/no response). The measure was dichotomized as ≥ 1 versus = 0 due to the skewed distribution of responses.

Impulsivity

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-15, Cronbach’s α = 0.75) total score was used to assess impulsive personality traits27. This is a 15-item measure rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = rarely/never, 4 = almost always). Higher scores reflect greater impulsivity. The measure comprises three subscales (nonplanning, motor, and attention) and a total score (sum of all items). It has shown internal consistency (α = .79 – .83) and 2-week test-retest reliability (r = .88), and discriminates between psychiatric patients and controls27. Individuals with inhibitory control deficits show elevated future weight gain48–50 and poorer response to weight loss treatment51,52.

EAH

EAH was assessed using a within-subjects crossover design to enable women to serve as their own controls. Women completed assessments individually at the University of Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for Women’s Health Research between March 2015 and September 2016. During the consent process, women were told that the purpose of the substudy was to investigate taste preferences during pregnancy and how taste preferences are related to food intake. Visits were scheduled between the hours of 18:00–19:30. On arrival, women rated subjective feelings of hunger and fullness on visual analog scales (VAS) ranging from −100 to 100 in response to questions phrased as “how [hungry/full] are you right now”, with anchors at “I am not [hungry/full] at all” and “I have never been more [hungry/full]”. Women were next presented with a standardized meal (dinner) (Table 1). Participants were instructed to eat until they were “no longer hungry.” Women were informed that more food would be provided if they were still hungry after finishing the standardized meal; however, none of the participants requested additional food. Women then rated their post-meal hunger and fullness by VAS. Ten minutes after finishing the standardized meal, test foods (Table 2) were presented and participants were asked to taste a small amount (approximately 1g; “one bite”) and evaluate pleasantness (“how pleasant does this taste”) and desirability (“how much would you want to eat these”) for each food item by VAS ranging from −100 to 100 anchored at “most unpleasant/least desire imaginable” to “most pleasant/desire imaginable”. Pleasantness and desirability ratings for all food items for each participant were combined to calculate each participant’s average pleasantness and desirability for each condition. For the free access period (EAH assessment), research assistants explained that the leftovers would be discarded after the visit, and that participants were free to eat as much of the food as they wished. Participants were not permitted to bring any food out of the room. The room also contained magazines and a sitting area for participants to use. Participants were left alone for a 15-minute period for the free access period. All food items were presented in equal volumes in standardized 1/2-pint containers and comparable consumable units (e.g., apple slices, bite-size brownies), and volume was held constant across conditions given the robust influence of volume on food intake53. PEAS research staff prepared all standardized meal and free access foods following standardized procedures. Foods were covertly weighed and recorded before and after the experiment to the nearest 0.1g.

Table 1.

Nutrient composition of the standardized meal for an Eating in the Absence of Hunger crossover substudy (March 2015 – September 2016) of 46 pregnant women in North Carolina enrolled in the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study.

| Food item | Weight, g | % carbohydrate | % protein | % fat | Energy, kcal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheese tortellini | 960 | 48.0 | 14.0 | 38.0 | 840 |

| Caesar salad | 390 | 69.0 | 11.0 | 20.0 | 250 |

| Bread stick | 30 | 71.0 | 13.0 | 16.0 | 100 |

| Total | 1650 | 54.3 | 13.3 | 32.4 | 1190 |

Table 2.

Serving amounts and characteristics of foods presented after a standardized meal for an Eating in the Absence of Hunger crossover substudy (March 2015 – September 2016) of pregnant women in North Carolina enrolled in the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study (n=46).

| Condition HPf | Food item | Amount served, g | Energy served, kcal | Intake, ga | Intake, %a,b | Energy density (kcal/100g) | Added sugarc, tspd/100g | Solid fatc, g/100 g | Total fate, g/100g | Sodiume, mg/100g | Typical serving sizee, g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet | Cookies | 112 | 525 | 14.6 ± 8.2 | 13.1 ± 7.3 | 469 | 7.7 | 24.3 | 21.9 | 359.4 | 32 |

| Brownies | 204 | 922 | 28.0 ± 22.7 | 13.7 ± 11.1 | 452 | 8.6 | 15.3 | 17.7 | 241.9 | 62 | |

| Peanut butter cups | 128 | 640 | 23.0 ± 25.7 | 18.0 ± 20.1 | 500 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 31.0 | 357.1 | 42 | |

| Savory | Potato chips | 50 | 286 | 7.8 ± 15.7 | 15.6 ± 31.4 | 571 | 0 | 0 | 35.7 | 571.4 | 28 |

| Nacho chips | 50 | 250 | 14.8 ± 11.6 | 29.6 ± 23.2 | 500 | 0 | 0 | 28.6 | 750.0 | 28 | |

| Popcorne,g | 30 | 171 | 5.9 ± 6.9 | 19.8 ± 23.0 | 571 | 0 | 5.8 | 35.7 | 1035.7 | 28 | |

| Total- HP | 574 | 2794 | 487 | ||||||||

| MPh | |||||||||||

| Sweet | Grapes | 204 | 141 | 46.1 ± 44.2 | 22.6 ± 21.7 | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 2 | 151 |

| Apples | 130 | 68 | 35.6 ± 27.5 | 27.4 ± 21.1 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1 | 182 | |

| Clementines | 140 | 74 | 40.2 ± 35.2 | 28.7 ± 25.2 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 88 | |

| Savory | Grape tomatoes | 140 | 25 | 17.6 ± 20.9 | 12.6 ± 14.9 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 5 | 149 |

| Peanutsi | 106 | 643 | 7.1 ± 8.0 | 6.7 ± 7.5 | 607 | 0 | 0 | 49.7 | 6 | 28 | |

| Baby carrots | 146 | 60 | 9.9 ± 7.8 | 6.8 ± 5.4 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 69 | 90 | |

| Total- MP | 866 | 1011 | 233 |

Mean ± SD

Calculated as 100 multiplied by amount consumed (g) divided by amount provided (g).

Information obtained from the manufacturer’s nutrition facts panel or the Food Patterns Equivalents Database (2017)59.

tsp, teaspoon

Information obtained from the manufacturer’s nutrition facts panel or the Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (2015–2016)60.

HP, highly processed experimental condition.

Cheese popcorn.

MP, minimally processed experimental condition.

Unsalted dry roasted peanuts.

EAH was assessed in each participant individually under two experimental conditions with at least a 1-week wash-out period to mitigate carryover effects, although those were anticipated to be minimal given the acute effect of the experimental manipulation. The two experimental conditions differed by the types of foods presented during the post-meal EAH assessment (free access period). The objective was to test whether the degree of food processing resulted in differences in EAH in pregnant women. The highly processed (HP) condition consisted of snacks and sweets, similar to typical EAH studies54,55. These foods meet the definition of ultra-processed foods according to the NOVA classification system26, that is, foods made mostly or entirely from additives and food derivatives with minimal if any intact unprocessed or minimally processed food. The minimally processed (MP) condition included unsalted dry roasted peanuts and raw fruit and vegetables, which meet the definition of unprocessed or minimally processed foods in the NOVA system26. To account for differences in individual preferences for sweet versus salty foods56–58, EAH test foods for both conditions were selected to include three sweet and three savory (i.e., non-sweet) options. Serving amounts, intake, and nutrient content59,60 are provided in Table 2. Ultra-processed foods are characteristically high in energy density due to added sugar and fat; however, this procedure was not intended to test the effect of energy density per se on EAH, and one of the food items presented in the MP condition (unsalted dry roasted peanuts) had the highest energy density of all items presented in both conditions. To account for period effects, the condition order was counterbalanced by alternating order assignment at the time of participant scheduling (prior to obtaining in-person consent) such that 26 women were scheduled to complete the conditions in either HP-MP or MP-HP order. Of the 6 women who were no-shows, 4 had been assigned to the MP-HP order and 2 to the HP-MP order. Additionally, due to scheduling changes, two participants assigned to the MP-HP order completed the assessments in the HP-MP order, such that 26 women completed the assessments in HP-MP order, and 20 completed the assessments in MP-HP order. Participants were blind to assigned treatment order.

Statistics

EAH was calculated for all foods consumed, and separately for sweet and savory foods. Given the large difference in total energy, energy density, and food weight across assessments and food items (Table 2), the outcome of EAH intake was evaluated both in units of energy (EAH-kcal) as well as the proportion of test foods consumed (EAH-%, calculated as 100[amount consumed (g)/amount served (g)])). Baseline sample characteristics were compared by condition order using Student’s t-tests and Pearson’s χ2. Differences in standardized meal intake across test conditions, subjective ratings of hunger and fullness before and after the test meal, hunger and fullness ratings between test conditions, and differences in mean pleasantness and desirability between conditions were evaluated using paired-sample t-tests. Pearson correlations using the Sidak adjustment for multiple comparisons examined bivariate associations of participant characteristics, hunger and fullness ratings with meal intake and EAH, associations of food ratings with EAH, and associations of meal intake and EAH within participants across conditions. The effect of condition on EAH was estimated using linear mixed models accounting for the within-person correlation (random effect for subject), and fixed effects for condition, time, and the interaction of condition and time. The model estimates the effects of condition (difference in mean EAH between the two conditions) controlling for period effects (time) and carryover effects (interaction of condition and time). The model also allows for unbalanced data using maximum likelihood estimation. Relationships of each self-reported reward-related eating measure and BIS with EAH were examined separately by including the variable as a covariate in the linear mixed models for the main analyses; standardized meal intake was not included as a covariate since it was considered along the causal pathway between self-reported reward-related eating, BIS and EAH. Multiplicative interaction terms were included to investigate whether BIS moderated associations of reward-related eating with EAH. Statistical significance was presumed when p < 0.05. StataSE version 14.243 was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Mean early pregnancy BMI was greater than 25 kg/m2 and did not differ by condition order (Table 3). The majority of participants were non-Hispanic white. Mean age was approximately 2.4 years younger in the group who received the HP condition first; there were no other sociodemographic differences by condition order.

Table 3.

Baseline sample characteristics of 46 pregnant women in North Carolina participating in an Eating in the Absence of Hunger crossover substudy (March 2015 – September 2016) of the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study.

| Condition order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | MPa-HPb | HP-MP | ||

| Characteristic | n=46 | n=20 | n=26 | Pc |

| Baseline age, y | 30.9 ± 3.4d | 32.3 ± 3.5 | 29.9 ± 3.0 | 0.02 |

| Early pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 25.7 ± 5.2 | 25.3 ± 4.9 | 26.0 ± 5.5 | 0.66 |

| Household income-poverty ratioe | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 3.8 ± 1.8 | 4.1 ± 1.9 | 0.61 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%)e | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 33 (73) | 15 (75) | 18 (72) | 0.67f |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (8) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 3 (7) | 1 (5) | 2 (8) | |

| Multi-race | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (8) | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 5 (11) | 4 (20) | 1 (2) | |

| Gestational age, weeks | 23.8 ± 5.4 | 24.9 ± 7.4 | 22.9 ± 2.9 | 0.22 |

| Power of Food Scale scoreg | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0.13 |

| Modified Yale Food Addiction Scale scoreh (n, %) | ||||

| ≥ 1 | 16 (35) | 15 (75) | 15 (58) | 0.22 |

| < 1 | 30 (65) | 5 (25) | 11 (42) | |

| Barratt Impulsivity Scale-15 scorei | 24.5 ± 4.7 | 25.5 ± 4.8 | 23.6 ± 4.6 | 0.19 |

MP, minimally processed condition

HP, highly processed condition.

Student’s t-test or Pearson’s χ2.

Mean ± SD (all such values).

Missing data for 1 participant.

Comparison of proportion of non-Hispanic white participants between condition order.

Min=1, max=5, higher values reflect greater self-reported hedonic hunger.

n, % of participants with responses at or above 1, reflective of higher endorsement of addictive-like eating.

Min=16, max=54, higher values reflect greater impulsivity. Missing data for 2 participants.

Average standardized meal intake was similar between conditions (Table 4), and was correlated within subjects (r = 0.74, p < 0.001). Hunger ratings significantly decreased, and fullness increased, from pre-meal to post-meal (p < 0.001), and there were no significant differences between test conditions in pre-meal or post-meal hunger or fullness. Mean pleasantness of the free access foods was higher in the HP versus MP condition (p = 0.02), whereas mean desirability was similar in the HP and MP condition (p = 0.14). Pleasantness was not correlated with EAH-kcal or EAH-% in the MP condition (p > 0.99) or HP condition (r = 0.33, p = 0.14 and r = 0.34, p = 0.13, respectively), but EAH-kcal and EAH-% in the HP condition were positively correlated with desirability (r = 0.41, p = 0.03 for both outcomes). There were no correlations (all p > 0.55) of meal or EAH-kcal with early pregnancy BMI, baseline age, gestational age at the time of first EAH assessment, household income-poverty ratio, post-meal hunger or post-meal fullness (Table 5). EAH in the HP condition was uncorrelated with EAH in the MP condition (EAH-kcal: r = 0.04, p > 0.99; EAH-%: r = −0.14, p > 0.99).

Table 4.

Mean ± SD meal intake, pre- and post-meal hunger and fullness, and pleasantness and desirability ratingsa of all test food items presented in the minimally processed (MP) and highly processed (HP) conditions in an Eating in the Absence of Hunger crossover substudy (March 2015 – September 2016) of pregnant women in North Carolina enrolled in the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study (n=44).

| Study variable | MP | HP | Differenceb | P-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meal intake, kcal | 820.1 ± 339.3 | 861.1 ± 313.2 | −41.0 ± 238.2 | 0.26 |

| Pre-meal hunger | 19.3 ± 36.4 | 16.2 ± 39.5 | 3.1 ± 37.9 | 0.59 |

| Post-meal hungerd | −65.1 ± 35.9 | −62.5 ± 40.9 | −2.5 ± 44.3 | 0.71 |

| Pre-meal fullness | −38.2 ± 41.5 | −45.0 ± 43.6 | 6.8 ± 45.9 | 0.33 |

| Post-meal fullnesse | 51.0 ± 24.9 | 46.1 ± 32.1 | 5.0 ± 30.1 | 0.28 |

| Pleasantness | 18.2 ± 15.0 | 25.4 ± 16.3 | −7.2 ± 19.9 | 0.02 |

| Desirability | 5.9 ± 18.7 | 12.6 ± 23.6 | −6.6 ± 29.2 | 0.14 |

Visual analogue scale ranging from −100 to 100. Participants were asked “how [hungry/full] are you now” to assess hunger and fullness. Participants were asked “how pleasant does this taste” to assess pleasantness of each food item, and “how much would you want to eat these” to assess desirability of each food item. Mean pleasantness and desirability for all food items within each condition was calculated for each participant.

Mean ± SD difference (MP – HP).

Differences between the MP and HP conditions were compared using paired t-tests.

Post-meal hunger significantly lower than pre-meal hunger in each condition (p < 0.001).

Post-meal fullness significantly higher than pre-meal fullness in each condition (p < 0.001)

Table 5.

Pearson’s r correlations (p-valuesa) of participant characteristics with standardized meal and EAHb intake from a crossover substudy (March 2015 – September 2016) of pregnant women in North Carolina enrolled in the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study (PEAS) (n=46).

| Meal intake, kcal | EAHb intake, kcal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | MPc | HPd | MPc | HPd |

| Early pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 0.16 (>0.99) | 0.13 (> 0.99) | 0.04 (> 0.99) | 0.14 (> 0.99) |

| Age, y | 0.17 (>0.99) | 0.14 (> 0.99) | 0.08 (> 0.99) | −0.13 (> 0.99) |

| Gestational age, weeks | −0.08 (>0.99) | −0.05 (>0.99) | 0.12 (>0.99) | 0.12 (> 0.99) |

| Household income-poverty ratio | 0.02 (>0.99) | −0.05 (> 0.99) | 0.05 (> 0.99) | 0.05 (> 0.99) |

| Post-meal hunger | −0.09 (>0.99) | −0.11 (> 0.99) | 0.15 (> 0.99) | 0.15 (> 0.99) |

| Post-meal fullness | 0.31 (0.55) | 0.02 (> 0.99) | −0.05 (> 0.99) | −0.05 (>0.99) |

| Pleasantness | -- | -- | −0.07 (>0.99) | 0.33 (0.14) |

| Desirability | -- | -- | −0.01 (> 0.99) | 0.41 (0.03) |

P-values are Sidak-adjusted for multiple comparisons.

EAH, eating in the absence of hunger.

MP, minimally processed experimental condition.

HP, highly processed experimental condition.

Based on marginal estimates from the linear mixed model examining EAH, holding order and standardized meal intake constant, EAH-kcal was higher in the HP versus MP condition overall (mean difference ± SE = 338.5 ± 34.2 kcal), and for sweet (mean difference ± SE = 238.3 ± 30.1 kcal) and savory (mean difference ± SE = 100.2 ± 15.8 kcal) foods (Figure 2). EAH-% overall was similar across conditions (mean difference ± SE = −1.6 ± 1.6) but was higher in the MP vs. HP condition for sweet foods (mean difference ± SE = −10.7 ± 2.3) and higher in the HP versus MP condition for savory foods (mean difference ± SE = 8.5 ± 2.5). In all models, the interaction of time with condition was not statistically significant (p>0.05), indicating that the effect of condition on EAH did not differ according to the order of assessments. The estimate for time (period effects) was also not statistically significant except for EAH-% overall (β ± SE = 5.0 ± 2.3, p=0.03) and EAH-% for sweet foods (β ± SE = 7.8 ± 3.3, p=0.02), indicating there was no period effect other than participants consumed a greater proportion of food (specifically sweet foods) at the second EAH assessment. This result likely reflects the greater proportion of sweet MP foods consumed by the larger proportion of participants who completed the MP condition at the second visit. Intraclass correlation coefficients were approximately equal to 0 for all models except those estimating EAH-kcal (ICC = 0.17) and EAH-% (ICC=0.14) of savory foods, indicating that subject-specific characteristics explained very little of the variance in EAH.

Figure 2.

Energy and percent consumed by 46 pregnant women when presented with highly processed (HP) and minimally processed (MP) snack foods during an Eating in the Absence of Hunger crossover substudy (North Carolina, March 2015 – September 2016) of the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study.

Sweet foods included cookies, brownies, and peanut butter cups in the highly processed (HP) condition, and grapes, apples, and clementines in the minimally processed (MP) condition. Savory foods included potato chips, nacho chips, and cheese popcorn in the HP condition, and grape tomatoes, dry roasted unsalted peanuts, and baby carrots in the MP condition. Overall intake reflects intake of all sweet and savory foods in each respective condition (p-values are presented for the effect of condition on EAH intake). Values were estimated from linear mixed models controlling for time, the interaction of condition with time, and intake at the standardized meal (n=46). Mean ± SE EAH overall was 461.3 ± 24.5 kcal (16.3 ± 1.1 %) for HP, 122 ± 25.0 kcal (17.9 ± 1.2 %) for MP; mean ± SE EAH for sweet was 309.7 ± 21.0 (14.7 ± 1.6 %) for HP, 71.3 ± 21.5 kcal (25.4 ± 1.7 %) for MP; mean ± SE EAH for savory was 151.6 ± 51.4 kcal (21.9 ± 1.9 %) for HP, 51.4 ± 12.3 kcal (13.3 ± 1.9 %) for MP.

In linear mixed models adjusted only for condition, time, and condition*time, there were no statistically significant associations of PFS with EAH (Table 6). EAH-kcal and EAH-% of savory foods were positively associated with m-YFAS. BIS was positively associated with EAH-kcal and EAH-% overall, and with EAH-% of sweet foods (the positive associations with EAH-kcal of sweet foods was not statistically significant, p = 0.06). Estimates from the interaction models indicated there was little evidence of effect modification of PFS or m-YFAS with BIS on EAH, except that the positive association of m-YFAS with EAH-kcal of savory foods decreased with increasing BIS (Table 6).

Table 6.

Associations of EAHa intake with self-report measures of reward-based eating and impulsivity in 46 pregnant women in North Carolina participating in a crossover substudy (March 2015 – September 2016) of the Pregnancy Eating Attributes Study.b

| EAH-kcalc | EAH-%d | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overalle | Sweetf | Savoryg | Overalle | Sweetf | Savoryg | |||||||

| Unadjusted Models | β ± SE | P | β ± SE | P | β ± SE | P | β ± SE | P | β ± SE | P | β ± SE | P |

| PFSh | 38.3 ± 32.6 | 0.24 | 45.6 ± 27.2 | 0.09 | −6.5 ± 17.2 | 0.71 | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 0.13 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 0.05 | −1.3 ± 2.7 | 0.63 |

| mYFASi | 5.5 ± 38.6 | 0.89 | −36.6 ± 32.0 | 0.25 | 42.0 ± 19.0 | 0.03 | 0.9 ± 1.8 | 0.24 | −0.6 ± 2.5 | 0.82 | 6.6 ± 2.9 | 0.02 |

| BISj | 8.0 ± 3.9 | 0.04 | 6.1 ± 3.3 | 0.06 | 1.9 ± 2.1 | 0.37 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.01 | −0.02 ± 0.3 | 0.94 |

| Interaction Model 1 | ||||||||||||

| PFSh | 43.7 ± 188.5 | 0.82 | −38.2 ± 158.1 | 0.81 | 86.9 ± 98.7 | 0.38 | 0.4 ± 8.7 | 0.96 | −1.2 ± 12.1 | 0.92 | 6.7 ± 15.7 | 0.67 |

| BISj | 10.4 ± 15.7 | 0.51 | −0.5 ± 13.2 | 0.97 | 11.3 ± 8.3 | 0.17 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.67 | 0.2 ± 1.0 | 0.81 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 0.56 |

| PFSh * BISj | −1.4 ± 7.1 | 0.85 | 2.5 ± 6.0 | 0.67 | −4.0 ± 3.7 | 0.28 | 0.02 ± 0.3 | 0.96 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.77 | −0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.58 |

| Interaction Model 2 | ||||||||||||

| mYFASi | 350.8 ± 208.0 | 0.09 | 87.3 ± 176.5 | 0.62 | 261.6 ± 102.5 | 0.01 | 13.8 ± 9.7 | 0.16 | 14.3 ± 13.5 | 0.29 | 23.7 ± 16.7 | 0.16 |

| BISj | 12.8 ± 4.8 | 0.007 | 8.5 ± 4.0 | 0.04 | 4.3 ± 2.4 | 0.07 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.31 | 0.005 | 0.11 ± 0.4 | 0.78 |

| mYFASi * BISj | −14.3 ± 8.2 | 0.08 | −5.3 ± 6.9 | 0.45 | −9.0 ± 4.0 | 0.03 | −0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.16 | −0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.22 | −0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.30 |

EAH, eating in the absence of hunger.

Linear mixed models adjusted for condition, time, and condition*time. Unadjusted Models: separate models estimating relationships of EAH intake with PFS, mYFAS, and BIS. Interaction Model 1: model estimating the relationship of EAH intake with PFS, BIS, and the interaction of PFS with BIS. Interaction Model 2: models estimating the relationship of EAH intake with mYFAS, BIS, and the interaction of mYFAS with BIS.

EAH-kcal, energy consumed during EAH

EAH-%, percent of EAH food consumed (100[amount consumed (g)/amount served (g)])

Intake of all EAH test foods.

Intake of sweet EAH test foods (highly processed: cookies, peanut butter cups, brownies; minimally processed: grapes, apples, clementines)

Intake of savory EAH test foods (highly processed: potato chips, nacho chips, cheese popcorn; minimally processed: grape tomatoes, dry roasted unsalted peanuts, baby carrots)

PFS, Power of Food Scale

mYFAS, modified Yale Food Addiction Scale

BIS, Barratt Impulsivity Scale

DISCUSSION

This experimental substudy assessed EAH in pregnant women using a cross-over experimental design in which participants were presented in one condition with highly processed (HP) snack foods typical of EAH studies (cookies, brownies, peanut butter cups, potato chips, nacho chips, cheese popcorn) and in the other condition with minimally processed (MP) foods (unsalted dry roasted peanuts, grape tomatoes, baby carrots, grapes, apple slices, clementines). The percent of free access foods consumed across the HP and MP conditions was similar, resulting in large differences in energy intake. Self-reported addictive-like eating and impulsivity were associated with greater EAH, but impulsivity did not modify associations of reward-related eating with EAH.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare EAH of highly processed versus minimally processed foods. The observed similarity in the proportion of foods consumed across the HP and MP conditions is unexpected given that overeating is hypothesized to occur primarily in the presence of highly rewarding, palatable foods that overwhelm homeostatic signals19,61–63. Rather, these results indicate that pregnant women consumed food in the absence of hunger across a wide range of food flavor and food processing level, and that the mere presence of foods can contribute to eating beyond satiation. Due to the similar proportion of food consumed across conditions and the large difference in energy density (kcal/g), energy intake was substantially greater in the HP versus MP condition, consistent with laboratory feeding studies assessing meal intake that have shown a direct effect on total energy intake of altering energy density while maintaining constant volume53. The present findings extend this literature by demonstrating the same effect on intake after meal termination in the absence of physiological hunger. Findings are also consistent with those of a controlled feeding study in which participants consumed greater total energy intake when presented with diets consisting of ultra-processed versus minimally processed foods, wherein energy density of foods was higher in the ultra-processed condition7. While that study did not explicitly report the proportion of foods consumed, it can be inferred from the data that participants consumed approximately 20% of presented snacks in both the ultra-processed and minimally processed experimental conditions, similar to the proportion of foods consumed during EAH in the present study (approximately 17% in both conditions). In the current study, micronutrient intake would similarly be expected to be greater in the MP versus HP condition, given that the foods across conditions differed on multiple characteristics aside from energy density. The implication of these results is that manipulation of available foods could have a large impact on energy intake and diet quality in pregnant women.

Of note, EAH across conditions was not correlated within subjects and the intraclass correlation coefficients from the mixed models were very low, suggesting that within-subject characteristics explained very little of the variance in EAH. Findings further indicate that EAH-kcal of sweet foods was greater than that of savory foods in both conditions, which may reflect the tendency to consume sweet rather than savory foods after an evening meal64. Simultaneously, the proportion of sweet foods was lower than that of savory foods in the HP condition and higher than that of savory foods in the MP condition, which may be partly attributable to the differences in total weight and energy of the sweet and savory foods resulting from holding volume constant across conditions. Manipulating different aspects of quantity would help clarify mechanisms underlying differences in EAH for HP and MP sweet and savory foods. The differential associations of m-YFAS and BIS with EAH overall and of savory versus sweet foods in this study are similar to a previous study that demonstrated differential associations of BIS subscales and external eating with sweet versus savory food intake33 and suggest that these related measures may reflect different aspects of reward-based eating.

Previous studies have demonstrated positive associations of EAH with motor impulsivity (a subscale of the BIS) in adult males and females65 and with the PFS in normal weight college females66. These findings are somewhat consistent with the current study, except that associations herein were not observed for all EAH variables, and associations were not statistically significant for PFS. Positive associations of laboratory-measured energy intake with alternative indicators of reward-related eating67–69 and impulsivity70,71 have been reported in studies of adults and children. Collectively, findings across multiple studies in participants of varying ages indicate that self-reported reward-related eating, impulsivity and other indicators of self-control are important proximal influences on intake within individual eating occasions. Whether these observations from laboratory studies translate to long-term dietary intake, and how to incorporate these findings into effective behavioral interventions to prevent eating beyond satiation, are important areas of future investigation.

In this study, there was no interaction between impulsivity and reward-related eating behaviors on EAH, as previously reported11. In that study, PFS in overweight and obese non-pregnant women was positively associated with EAH only in the presence of low inhibitory control as measured by a delay discounting task (measuring preference for smaller proximal rewards versus larger delayed rewards). Results presented here also differ from a study reporting that greater self-control attenuated the effect of high food reinforcement on energy intake during ad libitum eating in non-obese, non-pregnant women72. It is plausible that this difference may be due to pregnancy-related stress63,73 or the tendency of pregnant women to reduce efforts to inhibit reward-based eating decisions, as previously reported35,36,40.

Strengths of this study design that support the internal validity of the findings include the counterbalanced cross-over design, which minimizes period effects and enables participants to serve as their own controls, and the 1-week wash-out period, which minimizes carryover effects. Additionally, the laboratory-controlled experimental conditions enabled direct observation and precise assessment of intake. Limitations include the loss to follow-up of 2 participants and the lack of evidence regarding the generalizability of laboratory eating behaviors assessed at two occasions to long-term dietary intake, although the use of maximum likelihood estimation enables inclusion of all available data in the analysis examining the primary research question, minimizing bias from participant drop-out74. Due to study logistics, there was an unequal number of participants completing each condition order. However, age was the only characteristic that differed by order, and the pre-determined adjustment for time in the analyses along with the null association of time with EAH intake and null interaction of time with condition mitigates this potential limitation and indicates that condition order did not modify the effect of condition on EAH intake. Additionally, although the sample size is comparable to other EAH studies (n=46), the size and sociodemographic homogeneity limit generalizability to all pregnant women or women who are not pregnant.

CONCLUSIONS

In this experimental feeding study, the proportion of food consumed in the absence of hunger was similar for highly processed and minimally processed foods, resulting in substantial differences in energy intake. These findings add to a large literature indicating that altering the attributes of available foods can impact nutrient intake but challenge the hypothesis that eating beyond satiation occurs only in the presence of foods enhanced by added sugar and fat. Additionally, there was minimal evidence that inhibitory control modified the positive association of reward-related eating with EAH in pregnant women. Further examination of the psychosocial predictors of EAH in pregnant women is an important area of future investigation.

Research Snapshot.

Research question:

Does food processing level affect eating in the absence of hunger (EAH) in pregnant women, and is EAH associated with hedonic hunger, addictive-like eating, and impulsivity?

Key findings:

In this crossover feeding substudy, women consumed a similar proportion of minimally and highly processed foods, leading to a large difference in energy intake due to the higher energy content of highly processed foods. Greater addictive-like eating and impulsivity were related to greater EAH, whereas EAH was not related to hedonic hunger. Impulsivity did not modify the association of addictive-like eating with EAH.

Funding:

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Intramural Research Program (contract #HHSN275201300015C and #HHSN275201300026I/HHSN27500002).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Clinical Trial Registry: Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02217462. Date of registration: August 13, 2014.

Contributor Information

Leah M Lipsky, Social and Behavioral Sciences Branch, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child health and Human Development. 6710B Rockledge Dr. MSC 7004, Bethesda MD 20817. 301-435-6951..

Kyle S Burger, Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2204 McGavran-Greenberg Hall CB# 7461 Chapel Hill, NC 27599..

Myles S Faith, Department of Counseling, School and Educational Psychology, University at Buffalo Graduate School of Education. 420 Baldy Hall, Buffalo, NY 14288..

Anna Maria Siega-Riz, Current affiliation and contact information: School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. 109 Arnold House, University of Massachusetts, 715 N. Pleasant St., Amherst MA 01003-9304. Previous affiliation: Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC..

Aiyi Liu, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Branch, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child health and Human Development. 6710B Rockledge Dr. MSC 7004, Bethesda MD 20817..

Grace E Shearrer, Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2202 McGavran-Greenburg Hall CB# 7461 Chapel Hill, NC 27599..

Tonja R Nansel, Social and Behavioral Sciences Branch, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child health and Human Development. 6710B Rockledge Dr. MSC 7004, Bethesda MD 20817..

REFERENCES

- 1.Bodnar LM, Simhan HN, Parker CB, et al. Racial or Ethnic and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Adherence to National Dietary Guidance in a Large Cohort of US Pregnant Women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(6):867–877 e863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin D, Lee KW, Song WO. Pre-Pregnancy Weight Status Is Associated with Diet Quality and Nutritional Biomarkers during Pregnancy. Nutrients. 2016;8(3):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JL, Farr SL, Dietz PM, Sharma AJ, Barfield WD, Robbins CL. Trends in gestational weight gain: the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 2000–2009. Am J Obstet & Gynecol. 2015;212(6):806.e801–806.e808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kominiarek MA, Peaceman AM. Gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet & Gynecol. 2017;217(6):642–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilmore LA, Butte NF, Ravussin E, Han H, Burton JH, Redman LM. Energy Intake and Energy Expenditure for Determining Excess Weight Gain in Pregnant Women. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(5):884–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramakrishnan U, Grant F, Goldenberg T, Zongrone A, Martorell R. Effect of women’s nutrition before and during early pregnancy on maternal and infant outcomes: a systematic review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26 Suppl 1:285–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall KD, Hammond RA, Rahmandad H. Dynamic interplay among homeostatic, hedonic, and cognitive feedback circuits regulating body weight. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1169–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenny PJ. Reward mechanisms in obesity: new insights and future directions. Neuron. 2011;69(4):664–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthoud HR, Munzberg H, Morrison CD. Blaming the Brain for Obesity: Integration of Hedonic and Homeostatic Mechanisms. Gastroenterol. 2017;152(7):1728–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flint AJ, Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD, Field AE, Rimm EB. Food-addiction scale measurement in 2 cohorts of middle-aged and older women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3):578–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appelhans BM, Woolf K, Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Whited MC, Liebman R. Inhibiting food reward: delay discounting, food reward sensitivity, and palatable food intake in overweight and obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(11):2175–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulte EM, Avena NM, Gearhardt AN. Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein LH, Carr KA, Lin H, Fletcher KD. Food reinforcement, energy intake, and macronutrient choice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(1):12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berridge KC, Ho CY, Richard JM, DiFeliceantonio AG. The tempted brain eats: pleasure and desire circuits in obesity and eating disorders. Brain Res. 2010;1350:43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taha SA. Preference or fat? Revisiting opioid effects on food intake. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(5):429–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith DG, Robbins TW. The neurobiological underpinnings of obesity and binge eating: a rationale for adopting the food addiction model. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulte EM, Sonneville KR, Gearhardt AN. Subjective experiences of highly processed food consumption in individuals with food addiction. Psychol Addict Behav. 2019;33(2):144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poti JM, Mendez MA, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Is the degree of food processing and convenience linked with the nutritional quality of foods purchased by US households? Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1251–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Small DM, Difeliceantonio AG. Processed foods and food reward. Science. 2019;363(6425):346–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe MR, Butryn ML, Didie ER, et al. The Power of Food Scale. A new measure of the psychological influence of the food environment. Appetite. 2009;53(1):114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Gerber RA, et al. Evaluating the Power of Food Scale in obese subjects and a general sample of individuals: development and measurement properties. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(8):913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuz B, Schuz N, Ferguson SG. It’s the power of food: individual differences in food cue responsiveness and snacking in everyday life. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nansel TR, Lipsky LM, Eisenberg MH, Haynie DL, Liu D, Simons-Morton B. Greater Food Reward Sensitivity Is Associated with More Frequent Intake of Discretionary Foods in a Nationally Representative Sample of Young Adults. Front Nutr. 2016;3:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pursey KM, Collins CE, Stanwell P, Burrows TL. Foods and dietary profiles associated with ‘food addiction’ in young adults. Addict Behav Rep. 2015;2:41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulte EM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Gearhardt AN, Naar S. Food addiction prevalence and concurrent validity in African American adolescents with obesity. Psychol Addict Behav. 2018;32(2):187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac J-C, Levy RB, Louzada MLC, Jaime PC. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(1):5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spinella M NORMATIVE DATA AND A SHORT FORM OF THE BARRATT IMPULSIVENESS SCALE. Int J Neurosci. 2007;117(3):359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(9):1441–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedel JE, DeHart WB, Madden GJ, Odum AL. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: discounting of monetary and consumable outcomes in current and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(23):4517–4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guerrieri R, Nederkoorn C, Jansen A. How impulsiveness and variety influence food intake in a sample of healthy women. Appetite. 2007;48(1):119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerrieri R, Nederkoorn C, Stankiewicz K, et al. The influence of trait and induced state impulsivity on food intake in normal-weight healthy women. Appetite. 2007;49(1):66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guerrieri R, Nederkoorn C, Jansen A. The interaction between impulsivity and a varied food environment: its influence on food intake and overweight. Int J Obes. 2008;32(4):708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kakoschke N, Kemps E, Tiggemann M. External eating mediates the relationship between impulsivity and unhealthy food intake. Physiol Behav. 2015;147:117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meule A, Kubler A. Double trouble. Trait food craving and impulsivity interactively predict food-cue affected behavioral inhibition. Appetite. 2014;79:174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark M, Ogden J. The impact of pregnancy on eating behaviour and aspects of weight concern. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(1):18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies K, Wardle J. Body image and dieting in pregnancy. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38(8):787–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blau LE, Orloff NC, Flammer A, Slatch C, Hormes JM. Food craving frequency mediates the relationship between emotional eating and excess weight gain in pregnancy. Eat Behav. 2018;31:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groth SW, Morrison-Beedy D, Meng Y. How Pregnant African American Women View Pregnancy Weight Gain. JOGNN. 2012;41(6):798–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forbes EL, Graham EJ, Berglund C, Bell CR. Dietary Change during Pregnancy and Women’s Reasons for Change. Nutrients. 2018;10(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Padmanabhan U, Summerbell CD, Heslehurst N. A qualitative study exploring pregnant women’s weight-related attitudes and beliefs in UK: the BLOOM study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emery RL. A Perspective on the Potential Associations among Impulsivity, Palatable Food Intake, and Weight Gain in Pregnancy: Arguing a Need for Future Research. Current Addiction Reports. 2018;5(2):251–256. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nansel TR, Lipsky LM, Siega-Riz AM, Burger K, Faith M, Liu A. Pregnancy eating attributes study (PEAS): a cohort study examining behavioral and environmental influences on diet and weight change in pregnancy and postpartum. BMC Nutr. 2016;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stata Statistical Software: Release 14 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorpLP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Semega JL, Fontenot KR, Kollar MA. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2016. Washington, D.C.2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson CM, Strawderman MS. Modifiable behavioral factors in a biopsychosocial model predict inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burger KS, Sanders AJ, Gilbert JR. Hedonic Hunger Is Related to Increased Neural and Perceptual Responses to Cues of Palatable Food and Motivation to Consume: Evidence from 3 Independent Investigations. J Nutr. 2016;146(9):1807–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Francis LA, Susman EJ. Self-regulation and Rapid Weight Gain in Children From Age 3 to 12 Years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(4):297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kishinevsky FI, Cox JE, Murdaugh DL, Stoeckel LE, Cook EW, 3rd, Weller RE. fMRI reactivity on a delay discounting task predicts weight gain in obese women. Appetite. 2012;58(2):582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seeyave DM, Coleman S, Appugliese D, et al. Ability to Delay Gratification at Age 4 Years and Risk of Overweight at Age 11 Years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(4):303–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nederkoorn C, Jansen E, Mulkens S, Jansen A. Impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in obese children. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(5):1071–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pauli-Pott U, Albayrak O, Hebebrand J, Pott W. Association between inhibitory control capacity and body weight in overweight and obese children and adolescents: dependence on age and inhibitory control component. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;16(6):592–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ledikwe JH, Ello-Martin JA, Rolls BJ. Portion Sizes and the Obesity Epidemic. The Journal of Nutrition. 2005;135(4):905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls’ eating in the absence of hunger. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(2):215–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fisher JO, Birch LL. Eating in the absence of hunger and overweight in girls from 5 to 7 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(1):226–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chamoun E, Mutch DM, Allen-Vercoe E, et al. A review of the associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms in taste receptors, eating behaviors, and health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58(2):194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desor J, Greene L, Maller O. Preferences for sweet and salty in 9- to 15-year-old and adult humans. Science. 1975;190(4215):686–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drewnowski A Taste preferences and food intake. Annu Rev Nutr. 1997;17(1):237–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Food Patterns Equivalents Database 2015–2016: Methodology and User Guide. Food Surveys Research Group, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2017. http://www.ars.usda.gov/nea/bhnrc/fsrg. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- 60.USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies 2015–2016. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Food Surveys Research Group; 2018. https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/food-and-nutrient-database-dietary-studies-fndds. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- 61.Amin T, Mercer JG. Hunger and Satiety Mechanisms and Their Potential Exploitation in the Regulation of Food Intake. Curr Obes Rep. 2016;5(1):106–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sclafani A Gut–brain nutrient signaling. Appetition vs. satiation. Appetite. 2013;71:454–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Volkow ND, Wise RA. How can drug addiction help us understand obesity? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(5):555–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jaeger SR, Bava CM, Worch T, Dawson J, Marshall DW. The food choice kaleidoscope. A framework for structured description of product, place and person as sources of variation in food choices. Appetite. 2011;56(2):412–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fay SH, White MJ, Finlayson G, King NA. Psychological predictors of opportunistic snacking in the absence of hunger. Eat Behav. 2015;18:156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feig EH, Piers AD, Kral TVE, Lowe MR. Eating in the absence of hunger is related to loss-of-control eating, hedonic hunger, and short-term weight gain in normal-weight women. Appetite. 2018;123:317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mallan KM, Nambiar S, Magarey AM, Daniels LA. Satiety responsiveness in toddlerhood predicts energy intake and weight status at four years of age. Appetite. 2014;74:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carnell S, Wardle J. Measuring behavioural susceptibility to obesity: validation of the child eating behaviour questionnaire. Appetite. 2007;48(1):104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Epstein LH, Temple JL, Neaderhiser BJ, Salis RJ, Erbe RW, Leddy JJ. Food reinforcement, the dopamine D₂ receptor genotype, and energy intake in obese and nonobese humans. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121(5):877–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nederkoorn C, Dassen FC, Franken L, Resch C, Houben K. Impulsivity and overeating in children in the absence and presence of hunger. Appetite. 2015;93:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hughes SO, Power TG, O’Connor TM, Orlet Fisher J. Executive functioning, emotion regulation, eating self-regulation, and weight status in low-income preschool children: how do they relate? Appetite. 2015;89:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rollins BY, Dearing KK, Epstein LH. Delay discounting moderates the effect of food reinforcement on energy intake among non-obese women. Appetite. 2010;55(3):420–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fowles ER, Stang J, Bryant M, Kim S. Stress, depression, social support, and eating habits reduce diet quality in the first trimester in low-income women: a pilot study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(10):1619–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allison PD. Handling Missing Data by Maximum Likelihood. SAS Global Forum 2012; 2012; Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]