Abstract

Objective:

To perform an epidemiologic profile of pancreatic cancer (PC) in Puerto Rico (PR) with data gathered from 2001 to 2015.

Methods:

Using data from the PR Central Cancer Registry we estimated incidence and mortality rates and trends of PC in PR, and performed survival analyses. We also compared the age-standardized incidence and mortality rates of PC in people in PR with those of Hispanics, non-Hispanic whites, and non-Hispanic blacks in the United States (US).

Results:

From 2011 to 2015, 7.8 per 100,000 persons were diagnosed with PC in PR; higher rates were observed in men than in women (9.2 vs. 6.7 per 100,000, respectively) and in persons 65 years old and older (42.7 per 100,000 persons). For the same period, 6.7 per 100,000 persons died from PC; men and persons 65 years and older had higher mortality rates. Incidence and mortality trends of PC in PR increased from 2001–2015 (annual percent change [APC] = 3.8% and 1.9%, respectively (p<0.05). Lower risk of being diagnosed with and dying from PC was seen in PR than in members of several racial/ethnic groups in the US. The median survival time for PC cases diagnosed in PR during the period of 2008 to 2012 was 5.3 months.

Conclusion:

We observed increasing mortality rates and low survival in PC patients in PR. Research on access and response to treatment is needed to elucidate the reasons for the observed results and have a positive impact on PC burden and survival.

Keywords: Incidence, Mortality, Pancreatic cancer, Epidemiology, Puerto Rico

Resumen

Objetivo:

Elaborar un perfil epidemiológico para cáncer de páncreas (CP) en Puerto Rico (PR) de 2001 al 2015.

Metodología:

Utilizando datos del Registro Central de Cáncer de PR (RCCPR) estimamos las tasas y tendencias de incidencia y mortalidad de CP en PR, y realizamos análisis de sobrevida. Además las tasas de incidencia y mortalidad estandarizadas por edad en PR fueron comparadas con hispanos, blancos no hispanos y negros no hispanos en los Estados Unidos (EU). Tendencias de incidencia y mortalidad de CP fueron estimadas además de análisis de sobrevivencia.

Resultados:

Del 2011–2015, 7.8 por 100,000 personas fueron diagnosticadas con CP. La tasa de incidencia fue mayor en los hombres que en las mujeres (9.2 vs. 6.7 por 100,000, respectivamente), y en personas de 65 años o más (42.7 por 100,000 personas). Para el mismo periodo, 6.7 por 100,000 personas murieron de CP, los hombres y las personas de 65 años o más tuvieron mayores tasas de mortalidad. Las tendencias de incidencia y mortalidad de CP en PR aumentaron del 2001 al 2015 (cambio porcentual anual (APC [por sus siglas en inglés]=3.8% y 1.9%, respectivamente (p<0.05). Los puertorriqueños mostraron menor riesgo de ser diagnosticados y morir por CP en comparación con personas de otros grupos raciales/étnicos en los EU. La mediana de tiempo de sobrevivencia para las personas diagnosticadas con CP en PR durante 2008 al 2012 fue de 5.3 meses.

Conclusiones:

Observamos un aumento en mortalidad y una sobrevida baja de CP en PR. Hace falta investigación adicional sobre acceso y respuesta a tratamiento, para elucidar los resultados observados e impactar positivamente la sobrevivencia del CP en PR.

Despite low incidence rates, pancreatic cancer (PC) is a highly fatal malignancy. Globally, PC is the fourteenth and seventh most common cancer in terms of incidence and mortality, respectively (1). PC is more common in developed countries, the rates are 3-fold to 4-fold higher, with the incidence rates being the highest in Europe, North America, and Australia/New Zealand (1). In the United States (US), it is the third most frequent cause of cancer death after lung and colorectal cancer (2, 3). The survival of patients with PC is low, with only 8.5% of patients surviving 5 years, post-diagnosis (3). It is expected that PC will be the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the US by 2030 (2). Although the reasons for the observed increase in the incidence of this disease are unknown, changes in the prevalence of PC risk factors could help explain its increase, especially given that effective strategies to screen the general population for PC are still unavailable (4).

In Puerto Rico (PR), PC is also a common cause of cancer deaths, being the fifth (5.0% of all deaths) and the fourth (6.0% of all deaths) most common cause of cancer death among men and women, respectively, in 2014 (5). In PR, one of the cancer sites most associated with significant losses of labor productivity is the pancreas. The productivity loss in the labor market due to PC in PR in 2004 was $1,701,248, which represented 2.65% of total cancer costs for that year (6). However, despite the public health burden that PC imposes, there are no recent detailed reports of the epidemiology of PC in PR. The aim of this study was to describe PC incidence, mortality, and survival in PR, and thus, describe the burden of the disease in the island’s population. In addition, we compared the data of various racial/ethnic groups living in the US, with the data of the Puerto Rican population. The results of this study should be useful for health education and health promotion, both of which are necessary for the creation of prevention programs and public policy that will increase the awareness of PC and reduce its burden in PR.

Methods

Study design and study subjects

A secondary data analysis was conducted using the database of the PR Central Cancer Registry (PRCCR). This database was used to estimate the incidence, mortality, and survival of diagnosed PC cases (ICD-O-3: C25.0–C25.4; C25.7–C25.9) in PR during the period of 2001 to 2015. The study population consisted of all individuals residing in PR who were diagnosed with PC throughout the aforementioned period. This study was approved by the IRB of the University of PR Medical Sciences Campus.

Statistical analysis

The incidence and mortality rates of PC were analyzed by socio-demographic (age and sex) and tumor characteristics (tumor stage, histology, and tumor location). For most of the analyses, we included all diagnosed PC cases, including those found by death certificate only, except for the calculations of tumor stage, since these cases do not have additional information regarding the type of tumor diagnosed. Rates were calculated per 100,000 persons and age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (19 age groups - Census P25–1130). Incidence rates were estimated using the PRCCR database, based on the PC cases that were diagnosed in residents of PR from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2015. To calculate the variable of tumor stage, we used the Derived Summary Stage 2000. Mortality rates were estimated using death certificates from the Demographic Registry of the Department of Health of PR. Statistics were calculated using the SEER*Stat software, version 8.3.5 (7–9). In order to compare the incidence and mortality rates of PC in the Puerto Rican population with those of racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic whites [NHWs], non-Hispanic blacks [NHBs], and Hispanics that live in the US [USHs]), we used data from the SEER 18 Registry (8). Rates were also calculated per 100,000 persons and age-standardized to the 2000 US standard population for the period of 2011 to 2015; the rates were stratified by sex. Because PR is part of the US, for the purposes of this article, the term “United States” and the initialism “US” are being used to refer to the 48 contiguous states, Alaska, and Hawaii, not including PR or any of the other insular areas of the US; all references to PR are considering the island as a discrete region, and not as a part of the US.

Standardized rate ratios (SRRs), using PR age-adjusted rates as the reference, were calculated in order to determine the statistical differences between Puerto Ricans and the members of the previously named racial/ethnic groups; the results were also stratified by sex. Age-adjusted temporal trends of the incidence and mortality of PC in PR were also evaluated for the period of 2001 to 2015. Estimations of time trends were performed overall and by sex. The annual percent change (APC) was calculated using the Joinpoint Regression Program (version 4.6.0.0) (10).

Relative and observed survival proportions were calculated using the incidence case file database of PR, which was merged with the death certificate database (up to and including 2015) from the Demographic Registry of the Department of Health of PR. The cohort of PC patients for this analysis included cases that were diagnosed from 2008 to 2012; these cases were followed for 3 years in order to determine the proportion of cases that survived by the end of the period (December 31, 2015). Persons that had not died by the end of the follow-up period (December 31, 2015) were assumed to be alive. For survival analyses, persons identified by a death certificate only or with an autopsy only were excluded from this analysis. We also excluded those whose age was unknown, those who had secondary primary tumors, and those with no microscopic confirmation of disease. Relative survival is defined as the ratio of the proportion of observed survivors (all causes of death) in a cohort of PC patients to the proportion of expected survivors in a comparable cohort of cancer-free individuals (11). We also calculated overall observed survival time in months from date of diagnosis to date of death. Observed survival is equivalent to the number of patients remaining alive for a specific time-span divided by the total number of patients at risk of death during that specific time period (12). We estimated survival by histologic type (adenocarcinomas and mucinous and endocrine tumors) and disease stage at diagnosis (localized, regional, or distant) using the Kaplan–Meier method, and 1-and 3-year survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. We also compared survival time by period of PC diagnosis (1987–1991 [the end of the follow-up period for this group was December 31, 1994], vs. 2008–2012). STATA software (version 15.1) was used to calculate the relative and median survival times (13).

Results

Incidence and mortality rates

A total of 1,753 new PC cases were reported from 2011 to 2015 in PR; 52.5% were males and 70.5% were aged 65 years old or older (Table 1). Approximately one third of the tumors that were found (32.3%) were located in the head of the pancreas. Around 52% of the incident cases were classified under the histological category of adenocarcinoma. After excluding the cases reported by death certificate, we found that 14.3% of the PC cases were staged as being localized, 24.0%, as being regional, and 44.5%, as being distant (Table 1). The results for the incidence and mortality rates are divided into 3 periods: 2001 to 2005, 2006 to 2010, and 2011 to 2015 (Table 2). During the last period (2011–2015), 7.8 per 100,000 persons were diagnosed with PC; the incidence was higher for males than females (9.2 per 100,000 males vs. 6.7 per 100,000 females). Significant differences were observed by age group, with an elevated incidence among persons 65 years old or older (42.7 per 100,000) compared to those under 65 years old (2.8 per 100,000). In terms of mortality, a total of 1,514 deaths were reported during the period ranging from 2011 to 2015; 52.0% were males and 74.6% were persons aged 65 years old or older (Table 1). From 2011 to 2015, 6.7 per 100,000 persons of all ages died from PC. The mortality rates were similar for males (7.9 per 100,000) and females (5.8 per 100,000). In addition, the mortality rates were higher among people aged 65 years old or older (39.5 per 100,000) than they were for those who were less than 65 years old (2.0 per 100,000) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Pancreatic cancer incident cases and deaths in Puerto Rico, 2011–2015

| Incident cases N (%) | Deaths N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 913 (52.5) | 788 (52.0) |

| Female | 840 (47.5) | 726 (48.0) |

| Age | ||

| ≤ 64 years | 518 (29.5) | 385 (25.4) |

| ≥ 65 years | 1,235 (70.5) | 1,129 (74.6) |

| Tumor location | ||

| Head | 678 (38.7) | -- |

| Body | 153 (8.7) | -- |

| Tail | 163 (9.3) | -- |

| Pancreatic duct | 16 (0.9) | -- |

| Other specified parts of the pancreas | 20 (1.1) | -- |

| Overlapping lesions of the pancreas | 42 (2.4) | -- |

| Pancreas, NOS | 681 (38.8) | -- |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 906 (51.6) | -- |

| Mucinous | 65 (3.7) | -- |

| Endocrine | 51 (2.9) | -- |

| Other | 731 (41.7) | -- |

| Stage* (N = 1,575) | ||

| Localized | 225 (14.3) | -- |

| Regional | 378 (24.0) | -- |

| Distant | 701 (44.5) | -- |

| Unknown | 271 (17.2) | -- |

| Total | 1,753 (100) | 1,514 (100) |

Data for incidence and mortality include known age only.

Incident cases obtained by death certificate only were excluded.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted incidence and mortality of pancreatic cancer by sex, age group, and period: Puerto Rico, 2001–2015

| Sex | Age group | INCIDENCE |

MORTALITY |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2005 |

2006–2010 |

2011–2015 |

2001–2005 |

2006–2010 |

2011–2015 |

||||||||

| Rate | Count | Rate | Count | Rate | Count | Rate | Count | Rate | Count | Rate | Count | ||

| Male | ≤ 64 years | 1.9 | 159 | 2.5 | 219 | 3.5 | 301 | 1.8 | 148 | 2.0 | 177 | 2.6 | 232 |

| ≥ 65 years | 36.1 | 343 | 36.6 | 400 | 48.5 | 612 | 41.7 | 390 | 35.6 | 379 | 44.8 | 556 | |

| Overall* | 6.3 | 502 | 6.8 | 619 | 9.2 | 913 | 6.8 | 538 | 6.2 | 556 | 7.9 | 788 | |

| Female | ≤ 64 years | 1.2 | 113 | 1.7 | 171 | 2.2 | 217 | 1.0 | 96 | 1.2 | 127 | 1.5 | 153 |

| ≥ 65 years | 28.6 | 362 | 30.9 | 441 | 38 | 623 | 30.3 | 384 | 31.3 | 447 | 35.2 | 573 | |

| Overall* | 4.7 | 475 | 5.4 | 612 | 6.7 | 840 | 4.7 | 480 | 5.0 | 574 | 5.8 | 726 | |

| Overall | ≤ 64 years | 1.5 | 272 | 2.1 | 390 | 2.8 | 518 | 1.4 | 244 | 1.6 | 304 | 2.0 | 385 |

| ≥ 65 years | 31.9 | 705 | 33.5 | 841 | 42.7 | 1,235 | 35.1 | 774 | 33.2 | 826 | 39.5 | 1,129 | |

| Overall* | 5.4 | 977 | 6.0 | 1,231 | 7.8 | 1,753 | 5.6 | 1,018 | 5.6 | 1,130 | 6.7 | 1,514 | |

Rates are per 100,000 and age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (19 age groups - Census P25–1130). Incidence Data Source: Incidence case files of Puerto Rico from the Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry (August 14, 2018). Mortality Data Source: Mortality case files provided by the Demographic Registry of Puerto Rico (October, 2017). Population Source: Vintage 2016 estimate series from the population division of the United States Census Bureau.

Data include known and unknown age.

Incidence and mortality rates and SRR by US racial/ethnic group and by Puerto Rican population group

The age-adjusted incidence and mortality rates of PC are presented by US racial/ethnic group and by Puerto Rican population for the period of 2011 to 2015 (Table 3). Puerto Ricans had lower incidence rates of PC compared to those of the members of several racial/ethnic groups residing in the US. During the period defined previously, 8.2 per 100,000 males in PR were diagnosed with PC; this incidence rate is lower than that of USH (11.2 per 100,000), NHW (14.0 per 100,000), and NHB (16.3 per 100,000) males in the US. The incidence of PC for all racial/ethnic groups and including the population of PR was higher among men than women. For the same period, 6.1 per 100,000 Puerto Rican females were diagnosed with PC; this incidence rate is lower than that of NHW (10.5 per 100,000), USH (9.7 per 100,000), and NHB (13.9 per 100,000) females living in the US. NHBs had the highest incidence rate of all the populations studied. Moreover, results from the standardized rate ratios show that NHW males (SRR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.6 – 1.8) and females (SRR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.6 – 1.9) had a higher excess risk of PC in comparison to their counterparts in PR. USH males (SRR = 1.4; 95% CI: 1.3 – 1.5) and females (SRR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.5 – 1.7) also had a higher risk of PC in comparison to males and females living in PR. Furthermore, NHB males (SRR = 2.0; 95% CI: 1.9 – 2.2) and females (SRR = 2.3; 95% CI: 2.1 – 2.5) also had an excess risk of the disease in comparison to their counterparts in PR (Table 3).

Table 3.

Age-adjusted incidence and mortality (per 100,000) and SRRs of pancreatic carcinoma by sex and racial/ethnic group, Puerto Rico and US: 2011–2015

|

Age-Adjusted Incidence |

SRR (95% CI) |

||||||

| PR | NHW | USH | NHB | NHW vs. PR† | USH vs. PR† | NHB vs. PR† | |

| Male | 8.2 | 14.0 | 11.2 | 16.3 | 1.7 (1.6, 1.8)* | 1.4 (1.3, 1.5)* | 2.0 (1.9, 2.2)* |

| Female | 6.1 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 13.9 | 1.7 (1.6, 1.9)* | 1.6 (1.5, 1.7)* | 2.3 (2.1, 2.5)* |

| Overall | 7.0 | 12.1 | 10.4 | 15.0 | 1.7 (1.6, 1.8)* | 1.5 (1.4, 1.6)* | 2.1 (2.0, 2.3)* |

|

Age-Adjusted Mortality |

SRR (95% CI) |

||||||

| PR | NHW | USH | NHB | NHW vs. PR† | USH vs. PR† | NHB vs. PR† | |

| Male | 7.9 | 12.8 | 9.5 | 15.2 | 1.6 (1.5, 1.7)* | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3)* | 1.9 (1.8, 2.1)* |

| Female | 5.8 | 9.5 | 7.7 | 12.5 | 1.7 (1.5, 1.8)* | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4)* | 2.2 (2.0, 2.3)* |

| Overall | 6.7 | 11.0 | 8.6 | 13.7 | 1.6 (1.5, 1.7)* | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4)* | 2.0 (1.9, 2.1)* |

SRR: standardized rate ratio

reference group

statistically significant (p<0.05)

In terms of mortality, the results show that Puerto Ricans had lower mortality rates of PC than did the members of the racial/ethnic groups residing in the US that were being compared. During the period described previously, 6.7 per 100,000 persons in PR diagnosed with PC died; in that same time period, the estimates for USHs (8.6 per 100,000), NHWs (11.0 per 100,000), and NHBs (13.7 per 100,000) living in the US were all higher. The mortality of PC for all the populations studied was higher for males than for females. For the same period, 5.8 per 100,000 Puerto Rican females diagnosed with PC died, this compared to higher estimates for NHW (9.5 per 100,000), USH (7.7 per 100,000) and NHB (12.5 per 100,000) females. NHBs had the highest mortality rate of all the groups that were compared. Moreover, results from the standardized rate ratios show that NHW males (SRR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.5 – 1.7) and females (SRR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.5 – 1.8) had a higher risk of PC death in comparison to their counterparts in PR. USH males (SRR = 1.2; 95% CI: 1.1 – 1.3) and females (SRR = 1.3; 95% CI: 1.2 – 1.4) also had a higher risk of PC death in comparison to like individuals living in PR. Furthermore, NHB males (SRR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.8 – 2.1) and females (SRR = 2.2; 95% CI: 2.0 – 2.3) also had an excess risk of death from the disease in comparison to their counterparts in PR (Table 3).

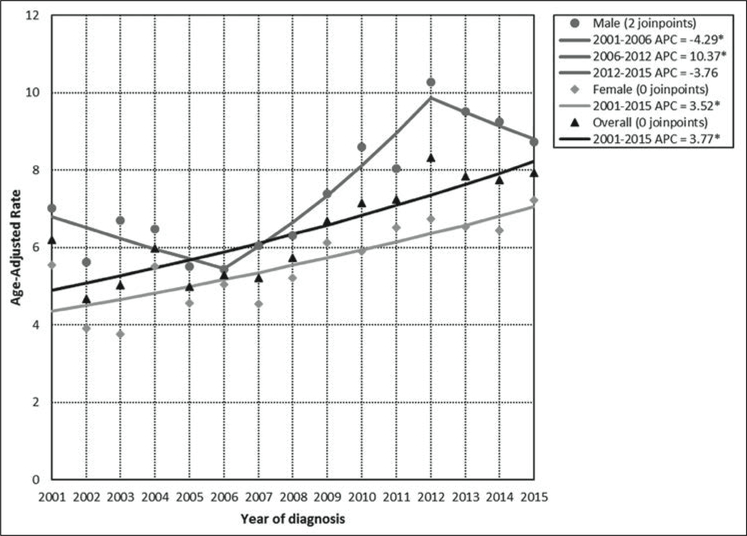

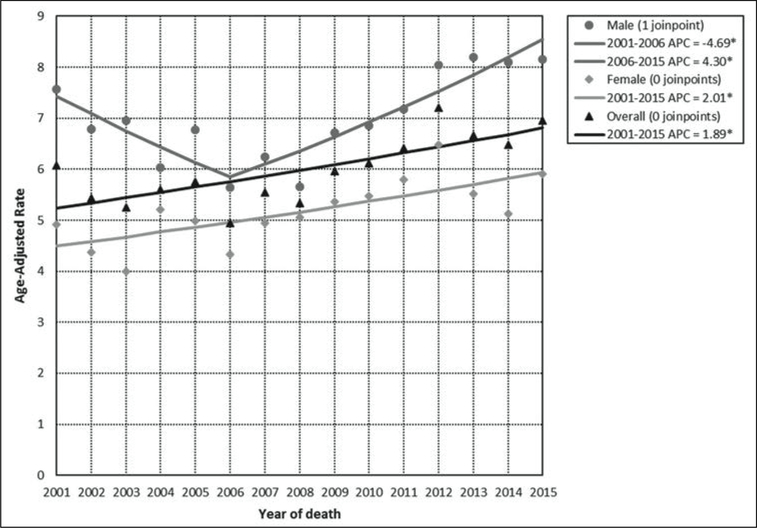

Incidence and mortality trends

The APC for the total incidence demonstrates a statistically significant (p<0.05) annual increase of 3.8% in PR for the period 2001 to 2015. For men, the incidence APC experienced an annual increase of 10.4% (p<0.05) from 2006 to 2012. For women, the incidence APC experienced a statistically significant (p<0.05) annual increase of 3.5% from 2001 to 2015 (Figure 1). Mortality overall had an annual increase in the period 2001 to 2015 (APC 1.9%); males had a mortality annual increase in the period 2006 to 2015 (APC = 4.3%) and females showed an increase in the mortality APC of 2.0% in the period covering 2001 to 2015. These changes were also statistically significant (p<0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Age-adjusted incidence rates and annual percent change (APC) for pancreatic cancer by sex: Puerto Rico, 2001–2015.

*statistically significant (p<0.05) annual percent change (APC)

Figure 2. Age-adjusted mortality rates and annual percent changes (APC) for pancreatic cancer by sex: Puerto Rico, 2001–2015.

*statistically significant (p<0.05) annual percent change (APC)

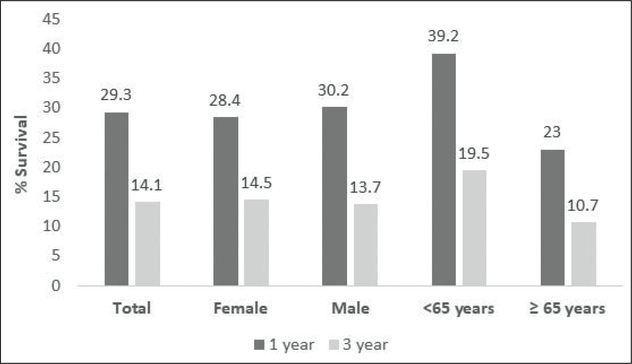

Relative survival

Relative survival was 29.3% at the end of the first year and 14.1% at the end of the third year in those diagnosed with PC (Figure 3). Meanwhile, a year after having been diagnosed, relative survival was slightly higher in males than females (30.2% vs. 28.4%). However, relative survival was slightly higher in females (14.5%) than males (13.7%) the third year after having been diagnosed. Assessed in terms of age, those who were less than 65 years of age had a higher relative survival (39.2%) 1 year after having been diagnosed, compared to those who were 65 years old or older (23.0%). Similar results were observed 3 years after having been diagnosed (19.5% vs. 10.7%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

1- & 3-year relative survival of pancreatic cancer in Puerto Rico by sex and age (2008–2012)

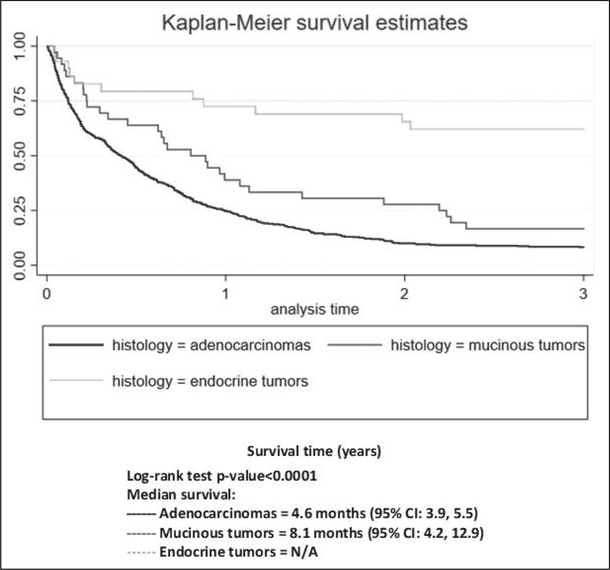

Observed survival

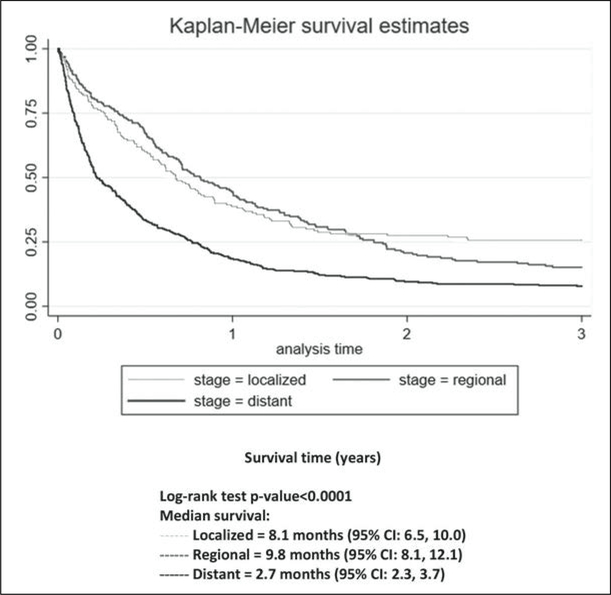

The median survival time for people diagnosed with PC from 1987 to 1991 in PR was 3.4 months, while the median survival time for people diagnosed from 2008 to 2012 was 5.3 months (log rank test, p>0.05). Kaplan–Meier curves by histology type and stage are presented; the survival rates for endocrine tumors were the highest followed by those for mucinous tumors and adenocarcinomas (log rank test, p<0.05; Figure 4). At all time points, the survival rates for distant-stage patients were the lowest of the 3 stages (log rank test, p<0.05, Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing percent survival for 3 years by histologic type of pancreatic cancer

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing percent survival for 3 years by stage at diagnosis

Discussion

Our study provides the first comprehensive epidemiological profile of PC in PR, with comparisons with several US populations. Compared to NHWs, NHBs, and USHs, Puerto Ricans living in PR have a significantly lower risk of developing and dying from PC. Trends for PC for the years 2001 to 2015 show that the incidence of this disease increased during the study period. Possible explanations for the observed increase in the incidence of PC might be improvements in the collection of PC cases by the PRCCR, the elevated exposure of the population to risk factors associated with the disease in PR (e.g. smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, alcohol), the increased life expectancy of the population, the availability of endoscopic interventions for the detection of PC, such as endoscopic ultrasound (since 2008, in PR), and the genetic predisposition of the newer generations (2, 14, 15). The incidence and mortality rates of pancreatic cancer in the US have also increased significantly in the past decades (16). Regarding PC risk factors (17, 18), these are common in the population of PR. Based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS-PR) (19), the prevalence of diabetes was 10.8% in 1996, increasing to 15.3% in 2016. Meanwhile, the prevalence of obesity is also very high in PR, and it has increased dramatically during the past decades (being 16.8% in 1996 and increasing to 30.7% in 2016). Meanwhile, although a slight decrease has been observed for tobacco use (being 14.5% in 1996 and falling to 10.6% in 2016), this high-risk behavior, as well as alcohol consumption (26.7% in 1997 and 28.0% in 2016), is common in PR. Analytical studies should further evaluate the reasons for the observed disease trends in order to develop appropriate prevention and control strategies in the future.

Our study also showed significant differences by age group, with a higher incidence of and mortality from PC among persons 65 years old or older. Consistent with previous studies, these results indicate that younger individuals are less likely to develop PC than older individuals are and that the incidence and mortality of PC increase with age (4). Similarly, the results of the present study show that males are more likely to develop PC than females are. In the US, the American Cancer Society indicates that males are about 30% more likely to develop PC than are females and suggests that this could be explained, at least in part, by an elevated use of tobacco by men, which use is one of the most influential risk factors for PC. The American Cancer Society highlights that, in fact, differences in the incidence of PC were, by sex, more pronounced in the past, when tobacco use was more frequent among men than women (20). Nonetheless, this gap has closed in recent years, as cigarette use is rising among females, specifically women 45 years old or older (20–22). In PR, although historical data are limited, the prevalence of tobacco use has remained relatively constant in women in the past years (23, 24), although data from the BRFSS-PR show that this use continues to be lower in women than men (8.0% vs. 13.6%, respectively, in 2016) (19).

Results from the present study also suggest that Puerto Ricans have a lower incidence of and mortality from PC in comparison to NHBs, NHWs, and USH. A lower incidence of PC was also reported in the years of 1998 to 2002 in a comparison of island Puerto Ricans with Puerto Ricans living in various US states (24), although in that study, no differences were observed between mainland Puerto Ricans and NHWs. Ho and colleagues suggested that the protective effect on Puerto Ricans of living in PR, with respect to PC risk, is lost once they move to the mainland US, supporting the clear importance of social and lifestyle risk factors over genetic ones. Previous studies conducted in the US evidence disparities in PC occurrence by race/ethnicity, with higher incidence rates for African Americans (25), which may be explained by a greater exposure to risk factors for PC in this racial/ethnic group, which risk factors include smoking, diabetes, alcohol consumption, and obesity (26). Nonetheless, the excess of PC incidence and mortality in this group cannot be attributed only to currently known risk factors, suggesting that genetic predispositions for mutations leading to PC might be present. However, further research is needed in this area in order to elucidate the reasons behind these differences (27).

Regarding survival, the results of this study showed that relative survival at the end of the third year after a diagnosis of PC was low in PR (14.0%); however, the population that lives in the US presents an even lower relative survival (8.0%) (28). Furthermore, the median survival time for persons diagnosed with PC in PR during the period 2008 to 2012 was only 5 months. This low survival could be explained by the fact that 33% of the patients’ tumors were in areas relatively distant from the pancreas and 44% of the patients’ tumors were adenocarcinomas (at the time of diagnosis); at this point, the malignancy would have progressed beyond the possibility of surgical cure. We also found that PC in a distant area and adenocarcinomas have lower survival rates. Similar results have been found in other studies, which results indicate that patients with endocrine pancreatic cancer survive longer than patients with exocrine tumors (29). Nonetheless, the high proportion of PC cases with an unstaged tumor in the PRCCR limits our ability to hypothesize on this factor. Despite this limitation, the reduced survival of PC is of concern and needs to be further addressed by research and intervention efforts, as, although uncommon, PC is highly fatal. In fact, PC is one of the few cancers for which survival has not improved substantially over the last 40 years (20). Therefore, research efforts have to focus on performing more research on PC, across the cancer-control continuum, in order to improve the prevention of and treatment options for PC, as well as improving the prognosis of those patients who get it.

This study was performed in the presence of some limitations. First, the assessment of risk factors that could explain the patterns of PC occurrence in PR was limited, as much of the relevant information is not collected by the PRCCR. Second, given the observational nature of our study, an evaluation of the possible factors that could explain the differences observed in the incidence and mortality rates of Puerto Ricans and of various racial/ethnic groups that live in the US could not be performed. These limitations should be addressed by future multi-centric analytical studies.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study describes the burden of PC in PR, providing essential data both for the assessment of research priorities and for public health efforts on behalf of this population. The incidence and mortality rates of PC in PR are lower than rates among other racial/ethnic groups in the US. Nonetheless, incidence trends are increasing among both men and women, and relative survival is low in PR. These trends should continue to be monitored in upcoming years, in order to determine if they persist. In addition, further studies are necessary in order to elucidate the reasons for the observed differences in disease occurrence between the population in PR and several racial/ethnic groups living in the US. Furthermore, an assessment of PC risk factors and characteristics, access, and response to treatment is required if we are to better understand these results. Future analytical studies are needed and should focus on further understanding the social, lifestyle, genetic, and environmental risk factors of PC, to achieve a decrease in its incidence and mortality. Moreover, efforts should be made to obtain early stage diagnoses to thereby improve later prognoses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a federal grant from the National Program of Cancer Registries (grant 1 NU58DP006318-02-00) to the PR Central Cancer Registry (PRCCR) at the UPR Comprehensive Cancer Center. The collection of cancer-incidence data by the Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry (PRCCR), as part of the statewide cancer-reporting program mandated by Puerto Rico State Law No. 28 of March 20, 1951, and Law No. 113 of July 30, 2010 (Law of the Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry), was supported, in part, by the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR, award 1 NU58DP006318-02-00) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s), and endorsement by the PRCCR is not intended, nor should it be inferred.

Abbreviations

- PR

Puerto Rico

- PRCCR

Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry

- USH

Hispanic

- NHW

non-Hispanic white

- NHB

non-Hispanic black

- US

United States

- APC

annual percent change

- PC

pancreatic cancer

Footnotes

The author/s has/have no conflict/s of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting Cancer Incidence and Deaths to 2030: The Unexpected Burden of Thyroid, Liver, and Pancreas Cancers in the United States. Cancer Res 2014;74:2913–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Pancreatic Cancer. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Available at: Url: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html. Accessed September 17, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Epidemiology and Prevention of Pancreatic Cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004;34:238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres-Cintrón CR, Alvarado-Ortiz M, Román-Ruiz Y, Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Zavala-Zegarra D, Tortolero-Luna G. Cancer in Puerto Rico, 2010–2014. Puerto Rico Central Cancer Registry. San Juan, PR. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Pérez-Irizarry J, Marín-Centeno H, et al. Productivity Loss in Puerto Rico’s Labor Market due to Cancer Mortality. P R Health Sci J. 2010;29:241–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surveillance Research Program [computer program]. National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software (www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat), version 8.3.5. Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2017 Sub (2000–2015) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2016 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2018, based on the November 2017 submission [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: mortality - all COD, aggregated with state, total U.S. (1990–2015) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment>, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released December 2017. Underlying mortality data provided by NCHS (www.cdc.gov/nchs).

- 10.Joinpoint Regression Program [computer program]. Version 4.6.0.0. April 2018; Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surveillance Research Program. Measures of Cancer Survival. Available at: Url: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/survival/measures.html. Accessed April 3,2018.

- 12.Goel MK, Khanna P, Kishore J. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int J Ayurveda Res 2010;1:274–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.StataCorp. 2017. [computer program]. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Majed HT, El-Basmi AA, Al-Mohannadi SH, Govindan R, Rajakumari GB. Pancreatic cancer: Incidence, clinical profile, and frequency of associated factors in Kuwait. Alexandria J Med 2013;49:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaid YH, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of pancreatic cancer in the United States: changes below the surface. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu W, He X, Yang L, et al. Rising trends in pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality in 2000–2014. Clin Epidemiol [online]. 2018;10:789–797 [vid. 2019–01-25]. ISSN 1179–1349. Dostupné z: doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S160018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghadirian P, Lynch HT, Krewski D. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: an overview. Cancer Detect Prev 2003;27:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, Abbruzzese JL. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2004;363:1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. BRFSS Survey Data and Documentation. Available at: Url: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2016.html. Accessed May 25, 2018.

- 20.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, et al. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults! United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Lung Association. Trends in Tobacco Use. 2011. Available at: Url: http://www.lung.org/assets/documents/research/tobacco-trendreport.pdf. Accessed.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). State-Specific Prevalence of Cigarette Smoking and Smokeless Tobacco Use Among Adults United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;16:180362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho GYF, Figueroa-Vallés NR, De La Torre-Feliciano T, et al. Cancer disparities between mainland and island Puerto Ricans. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2009;25:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saad AM, Turk T, Al-Husseini MJ, Abdel-Rahman O. Trends in pancreatic adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality in the United States in the last four decades; a SEER-based study. BMC Cancer 2018;18:688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eibl G, Cruz-Monserrate Z, Korc M, et al. Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity as Risk Factors for Pancreatic Cancer. J Acad Nutr Diet 2018;118: 555–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institute of Health. Investment in Pancreatic Cancer Research: Action Plan for Fiscal Year 2011. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD; 2011. Available at: Url: https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/pancreatic-action-plan.pdf. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnold LD, Patel AV, Yan Y, et al. Are racial disparities in pancreatic cancer explained by smoking and overweight/obesity? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:2397–2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fesinmeyer MD, Austin MA, Li CI, De Roos AJ, Bowen DJ. Differences in Survival by Histologic Type of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1766–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]