Abstract

Introduction:

The technologies used to treat the millions who receive care in intensive care unit (ICUs) each year have steadily advanced. However, the quality of ICU-based communication has remained suboptimal, particularly concerning for Black patients and their family members. Therefore we developed a mobile app intervention for ICU clinicians and family members called ICUconnect that assists with delivering need-based care.

Objective:

To describe the methods and early experiences of a clustered randomized clinical trial (RCT) being conducted to compare ICUconnect vs. usual care.

Methods and analysis:

The goal of this two-arm, parallel group clustered RCT is to determine the clinical impact of the ICUconnect intervention in improving outcomes overall and for each racial subgroup on reducing racial disparities in core palliative care outcomes over a 3-month follow up period. ICU attending physicians are randomized to either ICUconnect or usual care, with outcomes obtained from family members of ICU patients. The primary outcome is change in unmet palliative care needs measured by the NEST instrument between baseline and 3 days post-randomization. Secondary outcomes include goal concordance of care and interpersonal processes of care at 3 days post-randomization; length of stay; as well as symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder at 3 months post-randomization. We will use hierarchical linear models to compare outcomes between the ICUconnect and usual care arms within all participants and assess for differential intervention effects in Blacks and Whites by adding a patient-race interaction term. We hypothesize that both compared to usual care as well as among Blacks compared to Whites, ICUconnect will reduce unmet palliative care needs, psychological distress and healthcare resource utilization while improving goal concordance and interpersonal processes of care. In this manuscript, we also describe steps taken to adapt the ICUconnect intervention to the COVID-19 pandemic healthcare setting.

Enrollment status:

A total of 36 (90%) of 40 ICU physicians have been randomized and 83 (52%) of 160 patient-family dyads have been enrolled to date. Enrollment will continue until the end of 2021.

Keywords: Racial health disparities, critical illness, intensive care units, palliative care, mobile app, electronic health record (EHR) systems, randomized clinical trial (RCT)

Introduction

The quality of care delivered to the critically ill remains highly variable, particularly among Black patients and their family members.[1–6] Black patients are more likely than White patients to be both admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) in the last year of life and to die in the ICU.[7–9] Compared to White patients, Black patients who die in the intensive care unit (ICU) are less likely to have symptoms effectively managed and more likely to die receiving aggressive care such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and mechanical ventilation.[10, 11] While these observations are often explained by differences in disease stage, access to care, clinical management, and treatment preferences, it is also likely that differences in the quality of communication among clinicians, patients, and family members acting as surrogate decision makers are important.[12]

Poor quality of communication in the ICU is common among family member surrogates from all backgrounds.[13] Yet Black family members often report particularly poor interactions and therapeutic alliance building, especially during encounters with clinicians whose race is different from their own—the norm in ICU settings.[14–16] Families commonly report feeling unsupported in their surrogate decision making tasks, which promotes widely prevalent psychological distress and values-discordant treatments.[17–20] In addition, when compared to Whites, surrogates of Black patients often report less satisfaction with both end of life care in general and the extent to which providers listen and share information.[10, 21–24] Even though White and Black family member surrogates are equally likely to have a family meeting in the first 72 hours of their ICU stay, Black surrogates are less likely to have their care preferences documented and more likely to experience conflict with clinicians over treatment decisions.[25, 26] Furthermore, critical gaps in palliative care delivery (e.g., limited palliative care providers, poor family engagement, limited focus on family needs, suboptimal provider communication) may augment these race-based disparities in communication seen in Black patients and family members.

Therefore, we developed ICUconnect to remediate the poor quality communication and variable quality of palliative care delivered in the ICU setting. ICUconnect provides a digital infrastructure to guide the needs-focused interaction between family members and clinicians, promotes family engagement by providing a question coaching feature, and links families to reliable information on ICU practices and therapies. By using this systems approach to address key gaps in quality palliative care and communication, we aimed to improve patient, family, and systems outcomes and reduce disparities by overcoming common barriers to care. In a pilot trial including a historical palliative care control, the intervention prototype was acceptable to participants and was associated with reductions in unmet needs, family members’ symptoms of psychological distress, and patients’ receipt of goal discordant care.[27]

In this manuscript, we describe the design, methods, and planned analyses of an ongoing randomized clinical trial (RCT) testing the ICUconnect intervention. We also describe how the communication-focused intervention was adapted by necessity in response to the COVID-19 pandemic’s halting of family visitation to ICUs in the United States.

Materials and methods

How ICUconnect fits within the REACH Equity conceptual model.

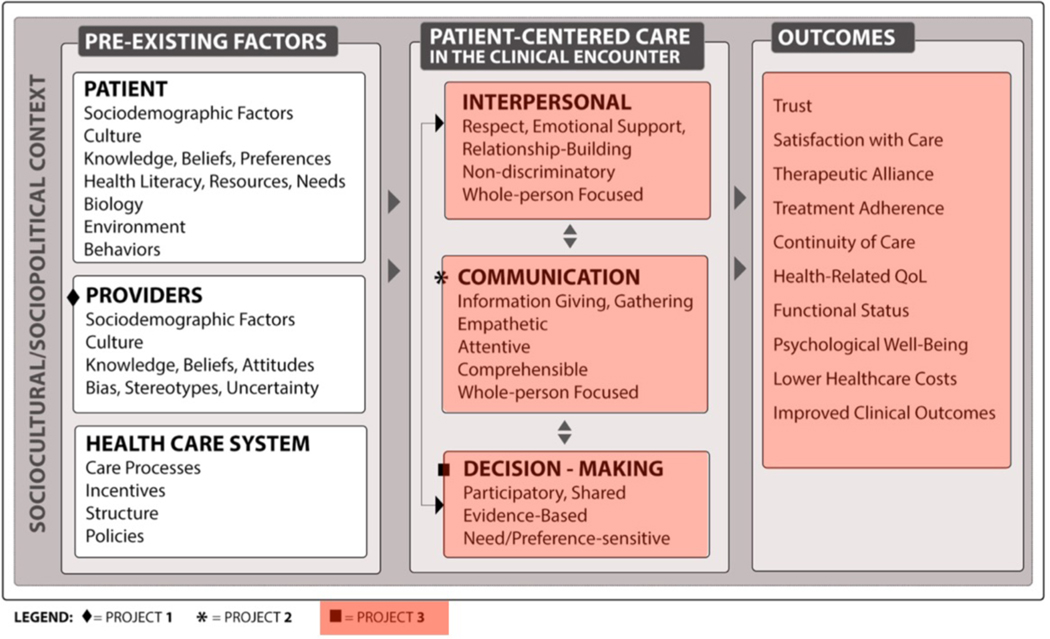

The ICUconnect trial is one of three ongoing trials within the Duke University Center for Research to Advance Healthcare Equity (REACH Equity) (sites.duke.edu/REACHequity). REACH Equity is one of the NIMHD Funded Specialized Centers of Excellence on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research. The overall theme of REACH Equity is to develop and test interventions that reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health by improving the quality of patient-centered care in the clinical encounter through better provider communication, high quality interpersonal processes of care, and shared decision making. ICUconnect addressed key domains of patient-centered care included in the REACH Equity conceptual model including communication and interpersonal relationships (project 3 in Figure 1). By improving these domains, ICUconnect aims to improve patient-centered care in the ICU clinical encounter and reduce racial disparities in areas where Blacks receive lower quality care.[10]

Figure 1:

Conceptual model for REACH center

Specific aims and hypotheses of the ICUconnect trial

The ICUconnect trial has two specific aims and one exploratory aim:

Primary aim:

To determine the effect of the ICUconnect intervention versus usual care on unmet needs (primary outcome) and perceptions of the quality of patient-centered care (secondary outcome) in the ICU, both overall and within Black and White patients and families.

Hypothesis 1a:

As compared to usual care, the intervention will improve unmet needs in both Black and White patients and families in the ICU.

Hypothesis 1b:

As compared to usual care, the intervention will improve quality of patient-centered care in both Black and White patients and families in the ICU.

Secondary aim:

To determine the effect of the ICUconnect intervention versus usual care on racial disparities in both unmet needs (primary outcome) and in the quality of patient-centered care (secondary outcome).

Hypothesis 2a:

Racial disparities in unmet needs will be reduced among patients and families in the ICU in the intervention group as compared to usual care.

Hypothesis 2b:

Racial disparities in the quality of patient-centered care will be reduced among patients and families in the ICU in the intervention group as compared to usual care.

Exploratory aim:

Using mixed methods, characterize the impact of ICUconnect across a variety of family- and patient-implementation contexts, with a goal of understanding intervention mechanisms.

Approach & goal:

We will integrate content analysis of semi-structured interviews with family members and clinicians as well as quantitative family, patient, and care process outcomes. This will provide insight into mechanisms of action and help to inform intervention optimization, replicability, and scalability.

Study design

This is a prospective, two-arm, parallel group mixed methods clustered RCT with 3-month follow up that includes ICU patients, family members, and ICU attending physicians. Randomization occurs at the level of the ICU attending physician, within whom patients are clustered.

Study sites

This study is being conducted in six medical and surgical ICUs at two hospitals within the Duke University Health System: Duke University Medical Center (Durham, NC; 152 adult ICU beds) and Duke Regional Hospital (Durham, NC; 22 ICU beds).

Participant eligibility

We aim to randomize 40 ICU attending physicians, 20 per treatment group, with a target of 2 Black and 2 White patient-family member dyads enrolled per physician (target total n=160 dyads). The inclusion and exclusion criteria for all participant groups are shown in Table 1, with the key eligibility factor being a baseline score of 15 or greater on the family member-completed Needs; Existential concerns; Symptoms; and Therapeutic interaction (NEST) scale adapted to use in the ICU setting.[28] Patients ≥18 years of age who receive mechanical ventilation in a study ICU for ≥48 hours continuously under the care of an enrolled study physician are eligible. Also required for each patient is one family member, defined as an individual (related or unrelated) who provides the most support and with whom the patient has a significant relationship.[29]. A key trial objective is to reduce disparities in unmet palliative care needs that have been described in past literature among the family members of Black ICU patients. To help achieve that aim, the intervention was culturally adapted for Black participants with qualitative input from Black clergy and community advisory board members serving the Black community. Although cultural differences in end-of-life beliefs also may vary among non-Black race and/or ethnic minority groups, we excluded these non-Black family members because the intervention was not directly informed by the input of relevant communities (e.g., Asian, Native American, Hispanic/Latinx). All participants who self-identified as Black, regardless of their other racial identities (e.g., multiracial, biracial, selecting more than one race), were potentially eligible for the trial.

Table 1:

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| Patients |

| Age ≥18 years |

| Received mechanical ventilation in a study ICU for ≥48 hours under care of a study ICU physician |

| Managed in an adult medical, cardiac, trauma, surgical, or neurological ICU for ≥48 hours |

| Family members |

| ≥18 years of age |

| Self-described as the individual (related or unrelated) who provides the most support and with whom the patient has a significant relationship (per definition of ‘family’ described in the Society of Critical Care Medicine 2016 Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU) |

| ICU physician |

| ≥18 years of age |

| Attending physician in a study ICU for at least 8 weeks per year |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Patients |

| Pre-consent |

| Decisional capacity |

| Death expected within 24 hours |

| Admission to an ICU at the index hospital >14 days |

| Comfort care or withdrawal of treatment planned |

| Imprisoned |

| Extubated and possess decisional capacity prior to informed consent |

| Died before T2 survey complete |

| No known family or surrogate |

| Care assumed by a non-study ICU attending after consent by patient/family but before T1 |

| Care assumed by non-study ICU attending <3 days after T1 but before T2 |

| Study ICU attending physicians from different groups (i.e., intervention or control) caring for patient change <3 days after T1 completed by family |

| Post-consent |

| Patient regains decision making capacity before T2 |

| Patient dies before T2 |

| Family members |

| Pre-consent |

| Lack a knowledge of English such that the potential participant is not confident that they could complete study tasks (app viewing, surveys) |

| Imprisoned |

| Unable to complete surveys for any reason |

| Describe their race as neither White nor Black* |

| Describe their ethnicity as Hispanic* |

| Post-consent |

| If the assigned randomized ICU attending physician either leaves ICU service or is replaced by a nonparticipating ICU physician <= 2 calendar days after family member completes T1 survey |

| Low need burden (NEST score <15)* |

| ICU physicians |

| None |

Note that this study explicitly targets issues of racial disparities in healthcare, particularly of Black / African-Americans. Hispanics are excluded because of the pervasive nature of US residents’ general belief that ‘Hispanic’ is a racial category.

Duration of subject participation and RCT

Three months from the time of randomization are required for each patient and family member to complete the entire study. Enrollment and follow up will occur over 42 months, with 3 months expected for data analyses.

Recruitment

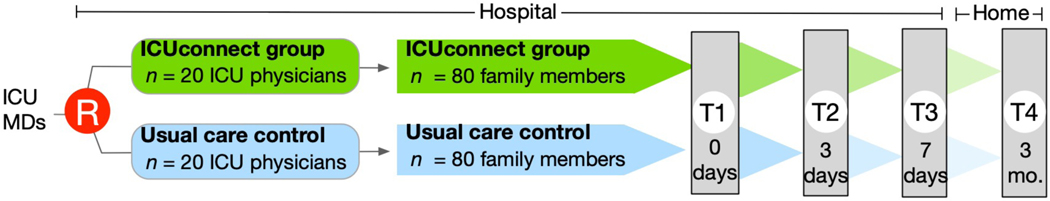

Figure 2 demonstrates an overview of the study flow, which is also described below.

Figure 2:

Trial flow

Step 1—identification and randomization of eligible physicians:

Before patients and family members were enrolled in the trial, study staff enrolled attending ICU physicians from study ICUs. After physicians provided written informed consent and completed a baseline study survey, they were randomized to intervention or control groups. A computer algorithm dynamically allocates ICU physicians in a 1:1 ratio via a method of minimization to ensure balance across strata. The strata include clinician characteristics known to be correlated with study outcomes including physician gender at birth (male vs. female), years of practice (<10 years vs. ≥10 years), and discipline (medical vs. surgical).

Step 2—identification of eligible patients:

Each morning the study team uses the EHR to screen study ICUs for eligible physicians and patients. Physician staffing records and the EHR are also used to ensure that a randomized physician is on service in each study ICU.

Step 3—enrollment of patient-family member dyads:

After approval is given by the ICU attending, trained study staff approach a family member (or surrogate with healthcare power of attorney if this designation doesn’t apply to the family member) for informed consent. Staff utilize an informational study video to quickly describe the trial to prospective participants (Appendix video material 1). After a patient-family member dyad has been enrolled, the ICUconnect platform generates a PHI-free secure text providing information about their assigned study group as well as a schedule for upcoming study milestones.

Intervention

Background and rationale:

By focusing ICU clinicians’ communication on patients’ and family members’ prioritized unmet palliative care needs, the ICUconnect mobile web app is designed to improve patient and family member outcomes. The intervention facilitates family members’ prospective reporting of unmet needs through the ICU course of their loved one, displays these needs in a simple data visualization for the ICU clinician, and provides advice and tips on discussing needs to both family members and ICU clinicians. ICUconnect is completely automated and uses unique URLs embedded in SMS text messaging and emails to quickly link family members and clinicians to the task at hand. Before the trial was initiated, a formal pre-testing protocol was followed that ensured that ICUconnect achieved acceptable usability by its target users as recommended by guidelines (Appendix 1).[30]

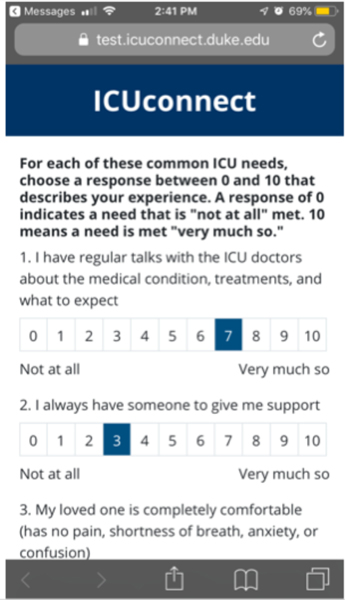

ICUconnect interactions by family members:

After enrollment to the intervention group, the study data system automates either a SMS text message or email (as preferred) to the family member that prompts T1 e-survey completion online (Figure 3). Subsequent study e-surveys are also sent in an automated, timed manner. Intervention family members can view the question prompt list by clicking on any message from the study data system.

Figure 3:

Screenshot of family member’s view of mobile app

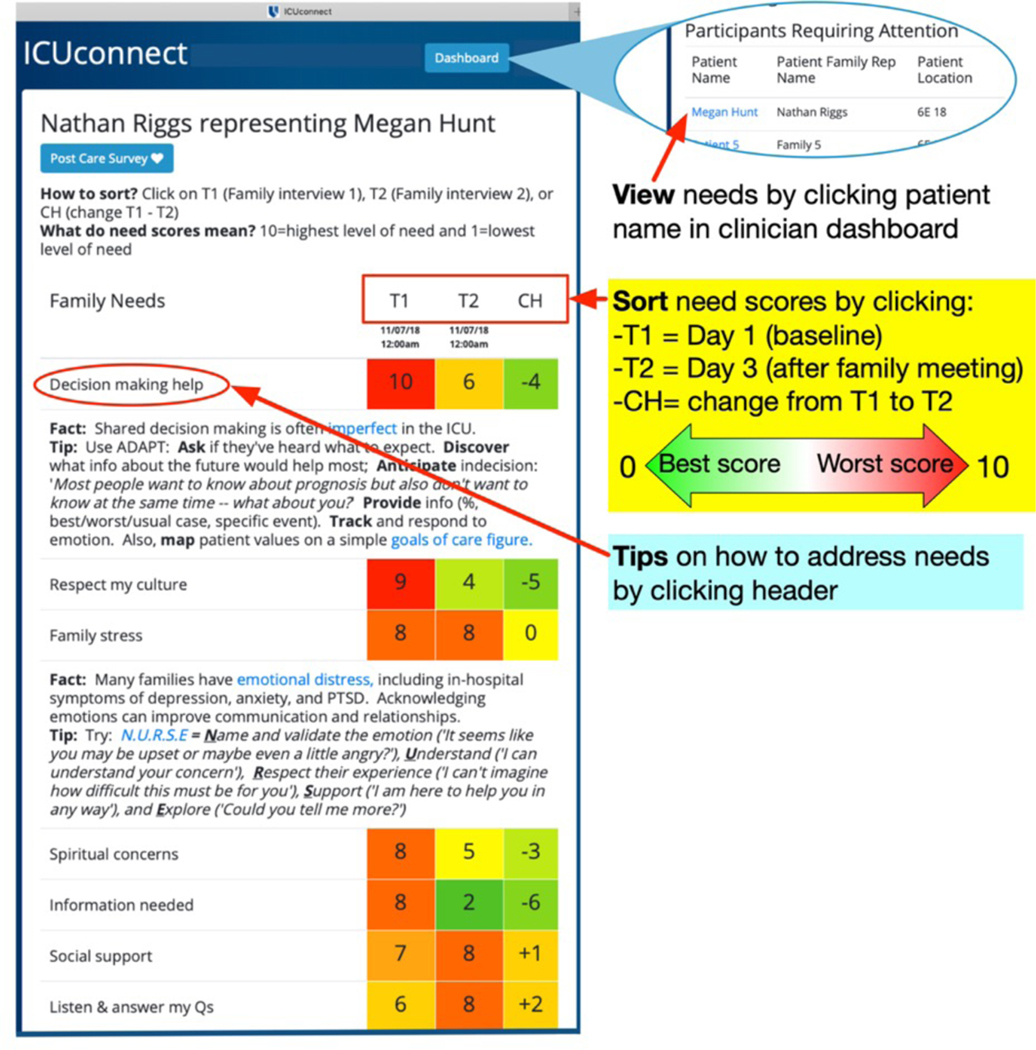

ICU physician role and procedures:

Study staff review all study procedures and train each ICU physician at the time they provide informed consent. At this time, the physician also completes a brief survey that characterizes their age, role, discipline, experience, and attitudes and beliefs about ICU-based palliative care derived from Wysham, et al.[31] Following this, ICU clinicians will interact with the ICUconnect app each time that an enrolled patient-family member dyad under their care completes a needs survey. They are able to view needs by clicking a unique URL link embedded in an SMS message automatically generated by the ICUconnect platform and then logging into the system using a secure Shibboleth authentication procedure. Figure 4 demonstrates the physician view. Usual care control patients will not be visible in the ICUconnect dashboard. ICU physicians are also prompted to discuss the patient’s and family member’s greatest unmet needs within 48 hours in a face-to-face family meeting. Within the ICUconnect platform, ICU clinicians can click on a need category header to view tips for addressing needs successfully. Following the family meeting, physicians click a box in the app noting they completed the interaction.

Figure 4:

Screenshot of clinician view of mobile app

ICU physician training and support:

In-person training aided by a variety of standardized materials was used to train ICU physicians, including a quick reference card (eFigure 1) and a quick start instructional video (Appendix video material 2).

Usual care condition

Patient-family member dyads enrolled under the care of an ICU physician randomized to the control group receive usual ICU care that does not include a prompted formal family meeting. Control group participants however complete e-surveys that are identical to the intervention group using the procedure described above.

Outcomes measures

Data are collected at pre-randomization baseline (T1 Data Collection) as well as 3 days (T2 Data Collection), 7 days (T3 Data Collection), and 3 months (T4 Data Collection) post-randomization (Figure 2). Data to be collected in the trial from all participants are shown in Table 2. The timing of the ICUconnect app’s messaging that prompts survey completion is shown in eFigure 2. While we anticipate that the majority of participants will still be in an ICU setting at study day 7 (T3), those who have been transferred to a hospital ward are to respond with a focus on experiences in the ICU.

Table 2:

Data collection and timing

| A. Clinical / patient information | T1 Baseline | T2 3 days post-enrollment | T3 7 days post-enrollment | T4 3 months post-enrollment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Baseline

General information Comorbidities Diagnoses APACHE II illness severity CPR information / baseline ICU type & admission source |

x | - | - | - |

|

Across entire hospitalization

CPR information / changes Palliative care consults Procedures and therapies Dates (mechanical ventilation, hospital, ICU) |

(x) | - | - | - |

|

3 months

3-month disposition |

- | - | - | (x) |

|

3 months

Readmitted during follow up |

- | - | - | (x) |

| Patient & family member information | ||||

| Contact info Gender DOB, race, gender, marital status, children Employment Financial distress Education Insurance Relation to patient Social support |

x | - | - | - |

| NEST (primary outcome) | x | x | x | - |

| Goal concordant care | x | x | x | - |

| Quality of communication | x | x | x | - |

| IPC (communication, decision making, interpersonal style domains) | - | - | x | - |

| PHQ-9 | x | - | x | x |

| GAD-7 | x | - | x | x |

| PTSS | x | - | x | x |

| Relationship with physician | x | x | x | - |

| Physician discussed needs (intervention group only) | x | x | x | - |

| Clinician information | ||||

| Gender Age Race / ethnicity Rank Service |

Study initiation | - | - | - |

| Physician responses | ||||

| I did family meeting | - | X | X | - |

CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; GAD-7: generalized anxiety disorder 7-item instrument; ICU: intensive care unit; IPC: Interpersonal Processes of Care survey; NEST: Needs; Existential concerns; Symptoms; and Therapeutic interaction scale; PHQ-9: patient health questionnaire 9-item depression instrument; PTSS: post-traumatic stress scale

Primary outcome

The primary trial outcome is family member-completed The Needs; Existential concerns; Symptoms; and Therapeutic interaction (NEST) scale assessed at T2.[28] The 13-item NEST (range from 0 reflecting no need to 130 reflecting highest need) samples each of the 8 National Consensus Project domains of palliative care quality including structure and processes of care, physical symptoms, psychological and emotional symptoms, social processes of care, spiritual needs, cultural needs, care of the dying patient, and ethical aspects of care.[32] In pilot work, we found that NEST scores correlated strongly with symptoms of psychological distress and the instrument itself was responsive to change over 1 week.[27] Trial eligibility requires a baseline NEST score of 15 or greater because while there is no consensus on the NEST’s minimal clinically important difference, a score ≥15 represents the clinically important equivalent of the presence of severe need in 1 or moderate need in 3 or more of its 13 items. Family members will complete the NEST at T1, T2, and T3.

Secondary outcomes

Psychological distress symptoms among family members are assessed with three surveys that all have strong evidence of validity, reliability, and responsiveness. Depression symptoms will be assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (PHQ-9).[33] Summed item scores range from 0 (no distress) to 27 (high distress). Anxiety symptoms will be quantified with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7).[34] Summed item scores can range from 0 (no distress) to 21 (high distress). The minimal clinically important difference for both the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 is 5 units. The 10-item Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome inventory (PTSS) will be used to rate family members’ post-traumatic stress symptoms (total score range 10 [no symptoms] to 70 [high burden of symptoms]).[35] A PTSS score ≥34 suggests a likely clinical diagnosis of PTSD and a 5-unit difference in score is generally accepted as clinically relevant. These surveys will be administered at T1, T3, and T4.

Patient receipt of goal concordant care is a dichotomous outcome (present or absent) that compares a family member’s perceptions of the patient’s treatment goal preferences (extend survival using any means possible, extend survival if possible but avoid prolonged life support that could lead to worse quality of life, or ensure comfort above all else) with the actual care they are receiving at T1, T2, and T3.[36]

The patient-centeredness of care will be assessed at T3 using the Elicited Concerns (1 item), Patient-centered Decision Making (3 items), and Discrimination (3 items) domains from the 29-item Interpersonal Processes of Care instrument which serves as the common measure used across all three REACH Equity center research projects.[37]

Clinical measures

Characteristics describing patients and their care will be recorded from the EHR including ICU admission diagnoses; illness severity); medical vs. surgical ICU service; post-enrollment duration of mechanical ventilation, duration of vasopressor use, receipt of major surgery, receipt of aggressive medical care (cardiopulmonary resuscitation, acute dialysis, tracheotomy, surgical feeding tube placement), and change in code status; ICU and hospital lengths of stay; receipt of palliative care consultation; and discharge disposition.

Data collection and management

Most data entry will be self-completed by participants online via timed, automated protected health information-free links sent via text from the mobile app platform. Study staff will complete electronic case report forms securely integrated within the data system. Using tested password-based customization strategies, the data system will allow only the Study Manager to view patient-level data such as treatment group assignment; all others will be blinded both to treatment group and to other sites’ participants. We will use a parallel study operations workflow tracking application to manage participants’ contact history log, survey schedule, and recorded adverse events.

Human subjects and regulatory oversight

The ICUconnect trial is approved by the Duke University institutional review board (protocol number 00090202), overseen by a 4-member independent data safety monitoring board (DSMB), and supervised by Duke University technology security representatives. The study data system includes an automated real-time alert system that sends an email to the core trial staff if any participant responds affirmatively to the PHQ-9’s suicidal ideation item. For each such alert, the PIs can click on the link to see contact information they then use to directly contact the participant for determination of an active plan and for support provision (subsequently documenting the interaction in the study data system). Participants also receive an email or text message that provides a list of phone numbers to distress hotlines and local resources for distress assistance. All reactions to the extreme distress alert are guided by a systematic approach codified within the trial manual of procedures. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03506438).

Statistical analysis

The goal of the primary hypothesis is to determine the efficacy of the ICUconnect intervention versus usual care on reduction in unmet needs from T1 to T2. We are also interested in the intervention effect within Black families and White families separately. Unmet needs will be assessed at T1 and T2 with the total NEST score, a continuous, normally distributed measure. Because each family member is surveyed at multiple time points and the same ICU physician sees several patients, outcome variable measurements will not be independent. Therefore hierarchical linear models will be used as the primary analytic strategy because they appropriately account for the multiple types of correlation inherent in our study design.

The experience of Black patients and family members in ICUs is relatively understudied, particularly in the context of palliative care. This trial also includes an exploratory aim that will use a qualitative analytic strategy to use family members’ own words to understand their perceptions of the intervention, facilitators and barriers to its use, and their particular palliative care needs (Appendix 2). As events unfolded in 2020 that included nationwide protests for racial equality and the reality of stark race-based disparities in COVID outcomes, we expanded the planned semi-structured interviews to explore these topics of contemporary importance in depth.

Sample size and power considerations

The effect of primary interest is the T1 – T2 difference between the intervention and usual care groups. Additional effects focus on the overall difference and the difference within Black and White patients separately as well as the difference within Black families compared to White families.

Sample size calculations on the mean difference score using tests for two means in a cluster randomized design. Based on preliminary studies, the standard deviation of the change in NEST score is estimated as 12 points and a reasonable range of intraclass correlation coefficients is 0.01 to 0.1 (eTable 1). For all calculations, the type-I error is 5% and power is 80%. We plan to enroll and randomize 40 physicians (20 in each group). With a sample size of 160 families (assuming 4 [2 Black patients and 2 White patients] per physician), we will be able to detect differences of 5.4 to 6.1 points in the overall test and 7.7 to 8.0 for Black or White patients separately. While the NEST’s minimal clinically important difference is unclear, this difference is likely of clinical significance given that the total NEST scored from 0 – 130 and a 7-unit change represents a marked change in score for a single NEST item. Additionally, pilot work demonstrates that this amount of change in the NEST total score was strongly correlated with changes in depression and anxiety symptom scores.[27] The sample size requirements are greatest for the secondary aim. As discussed by Leon and Heo,[38] the needed sample size for the family race by intervention group interaction is four times that needed for the overall test. Therefore, there may be limited power to detect this interaction effect given the impact of COVID-19 and other factors on trial enrollment.

Results

Trial progress

The trial began screening and enrollment on April 10, 2019. To date, 52 of 52 (100%) eligible ICU attending physicians have provided consent and 36 (90%) of the targeted 40 have been randomized (eTable 2, Table 3). Additionally, 83 family members (52% of target) have been enrolled (eTable 3, Table 4).

Table 3:

Demographics for randomized ICU physicians to date

| Characteristic | Total N=36 |

Intervention N=19 |

Control N=17 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender at Birth* | |||

| Male | 22 (61%) | 12 (63%) | 10 (59%) |

| Female | 14 (39%) | 7 (37%) | 7 (41%) |

| Gender Described | |||

| Man | 22 (61%) | 12 (63%) | 10 (59%) |

| Woman | 14 (39%) | 7 (37%) | 7 (41%) |

| Transgender | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Do not identify | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Years of Practice* | |||

| Less than 10 Years | 19 (53%) | 10 (53%) | 9 (53%) |

| 10 Years and Over | 17 (47%) | 9 (47%) | 8 (47%) |

| Type of Practice* | |||

| Medical | 22 (61%) | 12 (63%) | 10 (59%) |

| Surgical | 14 (39%) | 7 (37%) | 7 (41%) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 5 (14%) | 3 (16%) | 2 (12%) |

| Black or African American | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White | 31 (86%) | 16 (84%) | 15 (88%) |

| Another race | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (8%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (12%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 33 (92%) | 18 (95%) | 15 (88%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| How to handle palliative care issues | |||

| Myself | 13 (36%) | 8 (42%) | 5 (29%) |

| Team | 2 (6%) | 0 | 2 (12%) |

| Most myself, team for difficult cases | 21 (58%) | 11 (58%) | 10 (59%) |

| Practice Specialty | |||

| Medicine/Neurology | 22 (61%) | 12 (63%) | 10 (59%) |

| Surgery | 4 (11%) | 2 (11%) | 2 (12%) |

| Anesthesia | 10 (28%) | 5 (26%) | 5 (29%) |

| Weeks Attending in an ICU | |||

| <= 4 weeks | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5–8 weeks | 21 (58%) | 9 (47%) | 12 (71%) |

| 9–16 weeks | 13 (36%) | 10 (53%) | 3 (18%) |

| >16 weeks | 2 (6%) | 0 | 2 (12%) |

| Confidence in New Technology | |||

| Low | 2 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (6%) |

| Moderate | 21 (58%) | 12 (63%) | 9 (53%) |

| High | 13 (36%) | 6 (32%) | 7 (41%) |

| Enthusiasm for a Mobile App | |||

| Low | 6 (17%) | 2 (11%) | 4 (24%) |

| Moderate | 23 (64%) | 12 (63%) | 11 (65%) |

| High | 7 (19%) | 5 (26%) | 2 (12%) |

| Orientation Patient Care | |||

| Social and emotional primarily | 20 (56%) | 11 (58%) | 9 (53%) |

| Technical and scientific primarily | 16 (44%) | 8 (42%) | 8 (47%) |

| Preferred Style for a Decision | |||

| Lead patients and families | 5 (14%) | 4 (21%) | 1 (6%) |

| Engage as an equal partner | 25 (69%) | 12 (63%) | 13 (76%) |

| Provide information to patients and families for them to make their own decisions | 6 (17%) | 3 (16%) | 3 (18%) |

| Confidence in Communicating | |||

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate | 11 (31%) | 5 (26%) | 6 (35%) |

| High | 25 (69%) | 14 (74%) | 11 (65%) |

stratification variables

Table 4:

Family members enrolled to date by treatment arm

| Total N=83 |

Intervention N=42 |

Control N=41 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 51 (15) | 50 (15) | 52 (15) |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 52 (43, 61) | 50 (43, 62) | 55 (42, 61) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sex at Birth | |||

| Male | 14 (17%) | 9 (21%) | 5 (12%) |

| Female | 69 (83%) | 33 (79%) | 36 (88%) |

| Gender Described | |||

| Man | 13 (16%) | 9 (21%) | 4 (10%) |

| Woman | 68 (82%) | 33 (79%) | 35 (85%) |

| Transgender | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Do not identify | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 2 (2%) | 0 | 2 (5%) |

| Race | |||

| Black or African American | 33 (40%) | 14 (33%) | 19 (46%) |

| White | 50 (60%) | 28 (67%) | 22 (54%) |

| Education | |||

| Completed High School or Below | 18 (22%) | 12 (29%) | 6 (15%) |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Other College-Related Education | 40 (48%) | 20 (48%) | 20 (49%) |

| Graduate or Professional Degree | 18 (22%) | 7 (17%) | 11 (27%) |

| Missing | 7 (8%) | 3 (7%) | 4 (10%) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married or Live With a Partner | 40 (48%) | 22 (52%) | 18 (44%) |

| Separated, divorced | 17 (20%) | 8 (19%) | 9 (22%) |

| Widowed | 4 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) |

| Singled | 15 (18%) | 7 (17%) | 8 (20%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 7 (8%) | 3 (7%) | 4 (10%) |

| Employment | |||

| Working Full Time or Part Time | 51 (61%) | 23 (55%) | 28 (68%) |

| Homemaker Full Time | 3 (4%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (2%) |

| Unemployed | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Retired | 15 (18%) | 10 (24%) | 5 (12%) |

| Disabled | 6 (7%) | 4 (10%) | 2 (5%) |

| Student | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 7 (8%) | 3 (7%) | 4 (10%) |

| Insurance | |||

| Plan Purchased via Employer or Union | 43 (52%) | 18 (43%) | 25 (61%) |

| Plan, Self or Family Purchased | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medicare | 16 (19%) | 9 (21%) | 7 (17%) |

| Medicaid | 6 (7%) | 4 (10%) | 2 (5%) |

| TRICARE | 4 (5%) | 4 (10%) | 0 |

| Alaska Native, Indian or Tribal Health Services | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Some Other Source | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| None | 6 (7%) | 3 (7%) | 3 (7%) |

| Missing | 7 (8%) | 3 (7%) | 4 (10%) |

| Income | |||

| After paying the bills, you still have enough money for special things that you want | 30 (36%) | 13 (31%) | 17 (41%) |

| You have enough money to pay the bills, but little spare money to buy extra or special things | 32 (39%) | 18 (43%) | 14 (34%) |

| You have money to pay the bills, but only because you have cut back on things | 6 (7%) | 4 (10%) | 2 (5%) |

| You are having difficulty paying the bills, no matter what you do | 8 (10%) | 4 (10%) | 4 (10%) |

| Missing | 7 (8%) | 3 (7%) | 4 (10%) |

| Relationship to the Patient | |||

| Spouse or Partner | 30 (36%) | 16 (38%) | 14 (34%) |

| Child | 18 (22%) | 10 (24%) | 8 (20%) |

| Parent | 17 (20%) | 8 (19%) | 9 (22%) |

| Brother or Sister | 7 (8%) | 4 (10%) | 3 (7%) |

| Friend | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 4 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (7%) |

| Missing | 7 (8%) | 3 (7%) | 4 (10%) |

Adaptations made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, clinical research bans, and visitation limitations

The COVID-19 pandemic began to impact clinical research operations across the United States beginning in March 2020. Duke University, the site of the ICUconnect trial, instituted a ban on all non-COVID-19 clinical research in April 2020 as ICU beds began to be filled with COVID-19 patients. As COVID-19 infection rates decreased during the summer, restrictions were relaxed somewhat to allow the resumption of clinical research that did not involve direct contact with research participants. Not until September 2020 was direct contact allowed by research staff, and this contingent on the participant having no evidence of COVID-19.

Concurrent with the pandemic was the broad institution of visitation restrictions in hospitals across the nation. Beginning in April, no family visitors were allowed in the hospitals of Duke University. As medical teams gained more experience with COVID-19 and infection rates declined, visitation rules were relaxed gradually. First a family member was allowed to visit a dying family member patient. By November 2020, two visitors per patient could enter a room together, though during limited daytime hours.

Taken together, the research conduct and visitation restrictions were substantial challenges to the conduct of a trial with specific timeline-driven enrollment targets that was testing an intervention focused on promoting family member-ICU team communication through enhanced face-to-face family meetings.

To overcome barriers to our team’s standard of in-person informed consent conversations preceded by research introductions provided by ICU staff, we focused on optimizing a telephone-based approach beginning in April 2020. First, the PIs met with each study ICU’s physician and nurse leadership to raise awareness of the problem and to ask for help making phone-based research introductions and to conduct family meetings by phone. Second, we created scripted language for ICU staff to use to describe the trial in the research introduction. Third, we utilized a short self-produced ‘infomercial’ that allowed prospective participants to get a quick overview of the trial (Appendix 1). Last, we partnered with the Duke Institutional Review Board to create an electronic informed consent document that participants could complete online within a REDCap data platform via links sent in either email or text messages.

To overcome the fact that the face-to-face family meetings recommended as part of the trial could not be completed, we reframed the trial requirements for the busy clinicians by systematically re-educating randomized ICU attending physicians about the ways the ICUconnect intervention could help them to improve communication at a time when it was so difficult. We reminded them that given time constraints and their own bandwidths, the ICUconnect data visualization of family-prioritized needs could in fact be a valuable time saver during telephone conversations.

Discussion

ICUconnect aims to improve the quality of ICU-based palliative care by overcoming gaps relevant to race-based disparities in communication.

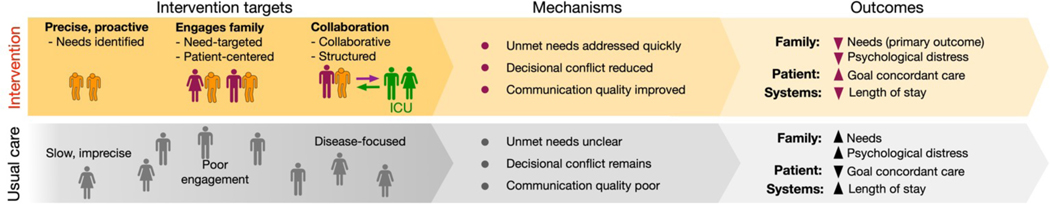

Our conceptual framework demonstrates four key gaps that limit rapid improvement in the quality of ICU-based palliative care (Figure 5):

Figure 5:

Conceptual model for intervention

1. Infrastructure gap:

The palliative care specialist workforce alone is too small to address the enormous ICU need.[39, 40] Also, there are delays in palliative care delivery [41–43] and high variability in palliative and end of life care practice at both the hospital level [44, 45] and the ICU physician level.[46, 47] To fill the gap, ICU teams need reliable and simple, yet usable, infrastructure that can help them deliver patient- and family-centered ‘primary palliative care.’[48] ICUconnect is a mobile app platform for family members and clinicians that provides reliable digital infrastructure that guides the interaction between family members and clinicians.

2. Family engagement gap:

It is essential to engage family members as partners in palliative care because nearly all seriously ill ICU patients require surrogate decision makers.[49] However, misunderstandings still persist such as equating palliative care with ‘giving up.’[4, 50] This may be even more true for Blacks who have less knowledge of palliative care and less positive beliefs and attitudes toward palliative care.[10] ICUconnect promotes family engagement by providing needs assessments, a question coaching feature, and links to reliable information on ICU practices and therapies.

3. The needs gap:

A focus on unmet basic palliative care needs is intuitive. However, this strategy is largely missing in all ICU-based palliative care trials conducted to date, most of which focus instead on ‘triggers’ based on a disease or illness severity.[44] Needs focused palliative care is relevant for disparities since Blacks may have greater unmet needs for communication, symptom management, and decision support, and may be more likely to see the presence of palliative care specialists as an attempt to prematurely terminate curative care.[10] ICUconnect allows self-report of patient and family needs as framed by quality domains, thereby allowing clinicians to know precisely and proactively what to prioritize in subsequent discussions. It also includes decision supports for handling specific needs that still exist after a family meeting.

4. Clinician communication content gap:

While there is evidence that many ICU clinicians fail to reliably elicit and address ICU patients’ palliative care needs,[51, 52] there is competing evidence that shows that when given proper communication supports, they can succeed and improve patient and family outcomes.[43, 53] Yet the feasibility and scalability of these supportive interventions, which provided rounding advisors and facilitators, are seriously limited by their requirement for additional staff. In addition, improving ICU clinician communication may be especially useful in reducing disparities given providers’ greater discomfort with end-of-life conversations among patients and families whose race and ethnicity differ from their own.[54] ICUconnect enhances clinicians’ communication content by displaying family need types and severity, as well as changes over time, in a visually understandable manner. It also provides tips on how to respond to common questions.

By using this systems approach to address key research gaps, we hypothesize that ICUconnect can improve patient, family, and systems outcomes and reduce disparities by overcoming barriers to care that are more common among blacks—hypotheses supported by our preliminary data.

Innovative features

There have been few recent ICU-based palliative care interventions that assessed patient-centered outcomes or focused on interventions to reduce disparities.[44] ICUconnect’s conceptual innovations represent a different direction in ICU-based palliative care delivery. While many have noted the inability of the specialist palliative care workforce to address all palliative care needs,[48] few have focused on scalable methods by which to assist ICU clinicians in delivering primary palliative care. ICUconnect is unique in its focus on actual patient and family needs as reported themselves—not diseases, illness severity, prognosis, or clinician perceptions—a highly innovative conceptual advance that is also singularly patient-centered. This framework enhances ICU generalists’ skills in assessing, communicating about, and intervening on patient and family palliative care needs and thus is more likely to align values with treatment as it improves continuity of care and opportunities for assessment and high quality interaction.

ICUconnect’s technological innovations enhance scalability. ICUconnect was developed to be a highly usable, adaptable app accessible on any digital device. By virtue of its web app build, it can be freely disseminated online. Yet ICUconnect also includes innovative functionalities that allow its integration with electronic health records systems and data registries. Its electronic patient-reported outcomes system, integrated with REDCap and upfitted with a customized scheduling system, allows automated survey completion by participants without study staff effort.

We envision ICUconnect as a digital hub for future palliative and end of life care supportive interventions to improve patient-centered care. Its family-facing aspect could easily be expanded to include more sophisticated decision aids, libraries of video content, and crowd-sourcing of questions from larger communities. Its clinician-facing features could also be enhanced to include video tutorials, advice, and tips. All of these features could grow organically as the app itself is more widely used and the user community grows.

Potential limitations and plans for addressing them in this clinical trial

Treatment diffusion is possible in a RCT. However, the risk of contamination from learned behaviors is low because ICU attendings generally work alone in a single ICU; passive uptake of complex communication skills is unlikely.[55, 56] Refusals, though low in our pilot and in our past ICU trials, would likely bias toward the null with a less distressed population. Increased mortality in the ICUconnect group is possible should comfort care be provided more often, an outcome however that has not been observed in an ICU-based trial.[41, 57] Such an outcome however would be acceptable if it reflected patients’ values,[58] as we will measure with the Interpersonal Processes of Care Scale and report to the DSMB.[59] Should the trial be negative, our study would still provide rich data in families’ and clinicians’ own words that could generate new hypotheses and inform different treatment approaches.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ICUconnect is an innovative intervention designed to improve the quality of ICU-based palliative care delivery (i.e., infrastructure, family engagement, focusing on needs, provider communication) across domains where racial disparities in care are documented. The current RCT aims to establish its efficacy in reducing unmet palliative care needs, reducing psychological distress, improving patient-centered care, and reducing disparities in palliative care outcomes between Blacks and Whites. Last, we have been able to continue the trial during the COVID-19 pandemic by reframing our intervention as a way to inform clinicians’ telephone interactions with family members as well as previously planned face-to-face meetings.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1: Quick reference for ICUconnect app for ICU physicians

eFigure 2: Study flow and ICUconnect alert system

Supplementary video 1: Informational video for patients and family members

Supplementary video 2: Instructional intervention training video for ICU clinicians

eTable 2: ICU physician screening and enrollment

eTable 1: Sample size calculations

eTable 3: Enrollment of family members

HIGHLIGHTS.

The quality of intensive care unit (ICU)-based palliative care is disproportionately poor for Black patients and their families, in part because of difficulties identifying those with unmet needs, coordinating care, and engaging participants in decision making.

ICUconnect is a mobile app-based intervention that systematically engages families and helps ICU clinicians deliver needs-targeted ‘primary’ palliative care.

This randomized clinical trial (RCT) tests the impact of ICUconnect vs. usual care on unmet needs, psychological distress symptoms, and clinical outcomes among a cohort of Black and White participants.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Andrew Corcoran (Duke OASIS), Smashing Boxes, ICU staff members, and the participating patients and family members.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) award 1U54MD012530.

Role of the funding source

This project was funded by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) award 1U54MD012530. The funder had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations:

- ICU

intensive care unit

- EHR

electronic health record system

- RCT

randomized clinical trial

Appendix 1: Usability testing procedures and results

Rationale

We conducted a formal usability study in February 2019 before the RCT began. The goal of this study was to optimize the ICUconnect mobile app before the trial by ensuring that it was understandable and functional to users.

Usability, the quality of the user’s experience, has a critical impact on the effect and uptake of a technology.[1, 2] As such, suboptimal app usability could negatively impact the success of the RCT. We conducted a formal usability study to optimize ICUconnect usability by improving user interface features based on clinician and family member interaction/response feedback as well as (b) to refine app security to contemporary standards.

Methods

First, our programmer consultants added ICUconnect features including: simpler secure login for clinicians, more navigable user interface, automated alerts to staff related to task completion, and enhanced dashboard views unique to study role (e.g., research coordinator vs. clinical teams vs. family members). During this process, enterprise-level security features were added per Duke’s standard requirements. Next, we will evaluated the usability of the enhanced ICUconnect web app among clinicians and family members using a mixed methods approach framed by our past experience in app development as well as Usability.gov guidelines. We performed prospective stratified purposive sampling from all study ICUs per criteria to enroll a diverse group of 6 ICU clinician and 6 family member testers.[3] During the 30-minute one-on-one evaluation sessions participants: (1) participated in a ‘think aloud’ protocol in which CRCs record participants’ comments in real-time as they use ICUconnect for group-relevant tasks; (2) completed the Systems Usability Scale (SUS), a well-validated usability measure; and (3) provided feedback in a semi-structured discussion.

Results

The mean SUS score was 77.5 (SD 5.5) units for family members and 89.6 (SD 8.1) units for ICU physicians. Users identified no notable functionality issues. As such, no further revisions were required.

Appendix 2: Qualitative analysis plan

Exploratory aim:

Using mixed methods (semi-structured interviews and quantitative process measures), to characterize the impact of ICUconnect across a variety of family- and patient-implementation contexts, with a goal of understanding intervention mechanisms.

Goal:

Using content analysis, we aim to get insight into ICUconnect’s mechanisms of action, relate outcomes to unique case contexts, and ultimately optimize the impact and scalability of the intervention.

This aim’s mixed methods analyses will explore and describe user experiences with the intervention to understand both mechanisms of action and how outcomes may be related to unique case contexts. This knowledge can also guide future intervention optimization through enhanced personalization, replicability, and scalability. [1–3] Interview transcripts will be analyzed using a content qualitative analysis technique that combines structural (e.g., intervention component, care process barriers) and magnitude coding (e.g., theme intensity) with inductive coding (e.g., variations in outcomes not captured by instruments).[4] The investigators will separately code the same 5 family member and clinician interviews, discuss the generated codes to create an initial code book by consensus. Next, they will each code 5 different interviews with further refinements made to the code book which will then be used by the investigators to code remaining 15 family member and clinician transcripts. While the final code book will be organized into categories used to generate themes of mechanistic and process elements from across all participants, within-case themes generated from family member and clinician interviews will be used to write case profiles. Case profiles will merge data from case context descriptors (family and clinician race, patient illness, etc), within-case qualitative themes, and quantitative process measures. A visual ‘ethnoarray’ matrix will be constructed to display key case findings in relation to every other case.[5] The ethnoarray, loosely adapted from a graphical heatmap approach, is a powerful way to present complex data and is a flexible method for blending narrative and quantitative data to facilitate the discovery of patterns, relationships and understand the contextual richness of the data. These procedures will enhance comparative analyses and theoretical interpretation.[6, 7] For example, case comparisons could be made by needs (needs met vs. needs unmet) or patient-centeredness of care (high vs. low). Process tracing will be used to explore how particular case outcomes (e.g., need, distress, goal concordance) may have been related to intervention components (e.g., needs assessment, family meeting) and to their effect on barriers in our conceptual model (Figure 1).[8, 9] ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software will be used for analyses.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

No author has conflicts of interest to report relevant to this manuscript.

6 potential peer reviewers:

Thanh Neville (UCLA), tneville@mednet.ucla.edu

Daryl Thornton (Case Western Reserve University), jdt13@case.edu

Donald Sullivan (Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland, OR), sullivad@ohsu.edu

Rebecca Aslakson (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA), aslakson@standford.edu

May Hua (Columbia University, New York, NY), mh2633@cumc.columbia.edu

Richard Mularski (Kaiser Health, Portland, OR), Richard.A.Mularski@kpchr.org

Erin Kross (University of Washington), ekross@uw.edu

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03506438

References

- [1].Danziger J, Angel Armengol de la Hoz M, Li W, Komorowski M, Deliberato RO, Rush BNM Mukamal KJ, Celi L, Badawi O. Temporal Trends in Critical Care Outcomes in U.S. Minority-Serving Hospitals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. 201: 681–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].DeCato TW, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, Back AL, Shannon SE, Kross EK, Curtis JR. Hospital variation and temporal trends in palliative and end-of-life care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2013. 41: 1405–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Meier D, Morrison RS. Center to Advance Palliative Care: Report Card. http://reportcard.capc.org/pdf/state-by-state-report-card.pdf

- [5].Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016. 315: 284–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Sharma R, Downey L, Fausto JA, Sibley J, Lober W, Khandelwal N, Loggers ET, Curtis JR. Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Healthcare Intensity at the End of Life. Journal of palliative medicine. 2018. 21:1308–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, Rubenfeld GD, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICUE-O-LPG. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004. 32: 638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Barnato AE, Berhane Z, Weissfeld LA, Chang CC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICUE-o-LPG. Racial variation in end-of-life intensive care use: a race or hospital effect? Health Serv Res. 2006. 41: 2219–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barnato AE, Chang CC, Saynina O, Garber AM. Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2007. 22: 338–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. Journal of palliative medicine. 2013. 16: 1329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Johnson RW, Newby LK, Granger CB, Cook WA, Peterson ED, Echols M, Bride W, Granger BB. Differences in level of care at the end of life according to race. Am J Crit Care. 2010. 19: 335–43; quiz 344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Soto GJ, Martin GS, Gong MN. Healthcare disparities in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2013. 41: 2784–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Burns KEA, Misak C, Herridge M, Meade MO, Oczkowski S, Patient, Family Partnership Committee of the Canadian Critical Care Trials G. Patient and Family Engagement in the ICU. Untapped Opportunities and Underrecognized Challenges. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018. 198: 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Elliott AM, Alexander SC, Mescher CA, Mohan D, Barnato AE. Differences in Physicians’ Verbal and Nonverbal Communication With Black and White Patients at the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016. 51: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003. 139: 907–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lane-Fall MB, Miano TA, Aysola J, Augoustides JGT. Diversity in the Emerging Critical Care Workforce: Analysis of Demographic Trends in Critical Care Fellows From 2004 to 2014. Crit Care Med. 2017. 45: 822–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cameron JI, Chu LM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Chan L, Thomas C, Friedrich JO, Mehta S, Lamontagne F, Levasseur M, Ferguson ND, Adhikari NK, Rudkowski JC, Meggison H, Skrobik Y, Flannery J, Bayley M, Batt J, dos Santos C, Abbey SE, Tan A, Lo V, Mathur S, Parotto M, Morris D, Flockhart L, Fan E, Lee CM, Wilcox ME, Ayas N, Choong K, Fowler R, Scales DC, Sinuff T, Cuthbertson BH, Rose L, Robles P, Burns S, Cypel M, Singer L, Chaparro C, Chow CW, Keshavjee S, Brochard L, Hebert P, Slutsky AS, Marshall JC, Cook D, Herridge MS, Investigators RP, Canadian Critical Care Trials G. One-Year Outcomes in Caregivers of Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016. 374: 1831–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cox CE, Martinu T, Sathy SJ, Clay AS, Chia J, Gray AL, Olsen MK, Govert JA, Carson SS, Tulsky JA. Expectations and outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2009. 37: 2888–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, Mor V. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004. 291: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of End-of-Life Care Provided to Patients With Different Serious Illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016. 176: 1095–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gordon HS, Street RL Jr., Sharf BF, Souchek J. Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer. 2006. 107: 1313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lee JJ, Long AC, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. The Influence of Race/Ethnicity and Education on Family Ratings of the Quality of Dying in the ICU. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016. 51: 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Long AC, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Kross EK, Reinke LF, Cecere Feemster L, Dotolo D, Ford DW, Back AL, Curtis JR. Race, income, and education: associations with patient and family ratings of end-of-life care and communication provided by physicians-in-training. Journal of palliative medicine. 2014. 17: 435–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Smith AK, Davis RB, Krakauer EL. Differences in the quality of the patient-physician relationship among terminally ill African-American and white patients: impact on advance care planning and treatment preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2007. 22: 1579–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Muni S, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Dotolo D, Curtis JR. The influence of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2011. 139: 1025–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL, Soares M, Rusinova K, Lafabrie A, Abizanda R, Svantesson M, Rubulotta F, Ricou B, Benoit D, Heyland D, Joynt G, Francais A, Azeivedo-Maia P, Owczuk R, Benbenishty J, de Vita M, Valentin A, Ksomos A, Cohen S, Kompan L, Ho K, Abroug F, Kaarlola A, Gerlach H, Kyprianou T, Michalsen A, Chevret S, Schlemmer B. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the CONFLICUS study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009. 180: 853–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cox CE, Jones DM, Reagan W, Key MD, Chow V, McFarlin J, Casarett D, Creutzfeldt CJ, Docherty SL. Palliative Care Planner: A Pilot Study to Evaluate Acceptability and Usability of an Electronic Health Records System-integrated, Needs-targeted App Platform. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2018. 15: 59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Scandrett KG, Reitschuler-Cross EB, Nelson L, Sanger JA, Feigon M, Boyd E, Chang CH, Paice JA, Hauser JM, Chamkin A, Balfour P, Stolbunov A, Bennett CL, Emanuel LL. Feasibility and effectiveness of the NEST13+ as a screening tool for advanced illness care needs. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010. 13: 161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, Netzer G, Kentish-Barnes N, Sprung CL, Hartog CS, Coombs M, Gerritsen RT, Hopkins RO, Franck LS, Skrobik Y, Kon AA, Scruth EA, Harvey MA, Lewis-Newby M, White DB, Swoboda SM, Cooke CR, Levy MM, Azoulay E, Curtis JR. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017. 45: 103–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Department of Health and Human Services. Research-Based Web Design & Usability Guidelines. 2013. http://www.usability.gov/sites/default/files/documents/guidelines_book.pdf?post=yes

- [31].Wysham NG, Hua M, Hough CL, Gundel S, Docherty SL, Jones DM, Reagan O, Goucher H, McFarlin J, Cox CE. Improving ICU-Based Palliative Care Delivery: A Multicenter, Multidisciplinary Survey of Critical Care Clinician Attitudes and Beliefs. Crit Care Med. 2017. 45: e372–e378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 2018. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

- [33].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001. 16: 606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006. 166: 1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Stoll C, Kapfhammer HP, Rothenhausler HB, Haller M, Briegel J, Schmidt M, Krauseneck T, Durst K, Schelling G. Sensitivity and specificity of a screening test to document traumatic experiences and to diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder in ARDS patients after intensive care treatment. Intensive Care Med. 1999. 25: 697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV. Medical care inconsistent with patients’ treatment goals: association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002. 50: 496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Stewart AL, Napoles-Springer AM, Gregorich SE, Santoyo-Olsson J. Interpersonal processes of care survey: patient-reported measures for diverse groups. Health Serv Res. 2007. 42: 1235–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Heo M, Leon AC. Sample size requirements to detect an intervention by time interaction in longitudinal cluster randomized clinical trials. Stat Med. 2009. 28: 1017–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kamal AH, Maguire JM, Meier DE. Evolving the Palliative Care Workforce to Provide Responsive, Serious Illness Care. Ann Intern Med. 2015. 163: 637–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lupu D. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010. 40: 899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, Hanson LC, Danis M, Tulsky JA, Chai E, Nelson JE. Effect of Palliative Care-Led Meetings for Families of Patients With Chronic Critical Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016. 316: 51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Le BH, Watt JN. Care of the dying in Australia’s busiest hospital: benefits of palliative care consultation and methods to enhance access. Journal of palliative medicine. 2010. 13: 855–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Villarreal D, Restrepo MI, Healy J, Howard B, Tidwell J, Ross J, Hartronft S, Jawad M, Sanchez-Reilly S, Reed K, Espinoza SE. A model for increasing palliative care in the intensive care unit: enhancing interprofessional consultation rates and communication. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011. 42: 676–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Aslakson R, Cheng J, Vollenweider D, Galusca D, Smith TJ, Pronovost PJ. Evidence-based palliative care in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of interventions. Journal of palliative medicine. 2014. 17: 219–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hart JL, Harhay MO, Gabler NB, Ratcliffe SJ, Quill CM, Halpern SD. Variability among us intensive care units in managing the care of patients admitted with preexisting limits on life-sustaining therapies. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015. 175: 1019–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Garrouste-Orgeas M, Tabah A, Vesin A, Philippart F, Kpodji A, Bruel C, Gregoire C, Max A, Timsit JF, Misset B. The ETHICA study (part II): simulation study of determinants and variability of ICU physician decisions in patients aged 80 or over. Intensive Care Med. 2013. 39: 1574–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hua M, Halpern SD, Gabler NB, Wunsch H. Effect of ICU strain on timing of limitations in life-sustaining therapy and on death. Intensive Care Med. 2016. 42: 987–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013. 368: 1173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Haines KJ, Kelly P, Fitzgerald P, Skinner EH, Iwashyna TJ. The Untapped Potential of Patient and Family Engagement in the Organization of Critical Care. Crit. Care Med. 2017. 45:899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2014. 42: 2418–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, Downey L, Shannon SE, Doorenbos AZ, Kross EK, Reinke LF, Feemster LC, Edlund B, Arnold RW, O’Connor K, Engelberg RA. Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013. 310: 2271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nelson JE, Puntillo KA, Pronovost PJ, Walker AS, McAdam JL, Ilaoa D, Penrod J. In their own words: patients and families define high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010. 38: 808–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Braus N, Campbell TC, Kwekkeboom KL, Ferguson S, Harvey C, Krupp AE, Lohmeier T, Repplinger MD, Westergaard RP, Jacobs EA, Roberts KF, Ehlenbach WJ. Prospective study of a proactive palliative care rounding intervention in a medical ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2016. 42: 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sanders JJ, Robinson MT, Block SD. Factors Impacting Advance Care Planning among African Americans: Results of a Systematic Integrated Review. Journal of palliative medicine. 2016. 19: 202–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Tulsky JA. Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. Journal of palliative medicine. 2005. 8: S95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, Downey L, Shannon SE, Braungardt T, Owens D, Steinberg KP, Engelberg RA. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008. 178: 269–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Cox CE, White DB, Hough CL, Jones DM, Kahn JM, Olsen MK, Lewis CL, Hanson LC, Carson SS. Effects of a Personalized Web-Based Decision Aid for Surrogate Decision Makers of Patients With Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019. 170: 285–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Holloway RG, Quill TE. Mortality as a measure of quality: implications for palliative and end-of-life care. JAMA. 2007. 298: 802–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000. 49: 796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References for Appendix 1

- [1].Nielsen J. Usability 101: Introduction to usability, (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [2].Usability.gov. Research-Based Web Design & Usability Guidelines, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Greysen SR, Chin Garcia C, Sudore RL, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE Functional impairment and Internet use among older adults: implications for meaningful use of patient portals. JAMA Intern Med 174 (2014) 1188–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References for Appendix 2

- [1].Sandelowski M. Unmixing mixed-methods research. Res Nurs Health 37 (2014) 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bazeley P. Integrative analysis strategies for mixed data sources. Am Behav Scientist 56 (2012) 814–828. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Results in Health Science Mixed Methods Research Through Joint Displays. Annals of family medicine 13 (2015) 554–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 3rd edition. ed., Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Abramson CM, Dohan D. Beyond Text: Using Arrays to Represent and Analyze Ethnographic Data. Sociol Methodol 45 (2015) 272–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Beach D, Rohlfing I. Integrating Cross-case Analyses and Process Tracing in Set-Theoretic Research Strategies and Parameters of Debate. Soc Meth Res doi: 10.1177/0049124115613780 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Docherty SL, Vorderstrasse A, Brandon D, Johnson C. Visualization of Multidimensional Data in Nursing Science. West J Nurs Res (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bennett A, Checkel JT Process Tracing: From Metaphor to Analytic Tool (Strategies for Social Inquiry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bennett A. Process Tracing: a Bayesian Perspective. in: Box-Steffensmeier JM, Brady HE, Collier D. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1: Quick reference for ICUconnect app for ICU physicians

eFigure 2: Study flow and ICUconnect alert system

Supplementary video 1: Informational video for patients and family members

Supplementary video 2: Instructional intervention training video for ICU clinicians

eTable 2: ICU physician screening and enrollment

eTable 1: Sample size calculations

eTable 3: Enrollment of family members