Abstract

Background:

Adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) improves outcomes in women with hormone-receptor positive (HR+) breast cancer (BC). Suboptimal AET adherence is common but data are lacking about symptoms and adherence in racial/ethnic minorities. We evaluated adherence by race and the relationship between symptoms and adherence.

Methods:

The Women’s Hormonal Initiation and Persistence (WHIP) study included women diagnosed with non-recurrent HR+ BC who initiated AET. AET adherence was captured using validated items. Data regarding patient (e.g., race), medication-related (e.g., symptoms), cancer care delivery (e.g., communication), and clinicopathologic factors (e.g., chemotherapy) were collected via surveys and medical charts. Multivariable logistic regression models were employed to calculate odds ratios and 95% CIs associated with adherence.

Results:

Of the 570 participants, 92% were privately insured and nearly 1/3 were Black. Thirty-six percent reported nonadherent behaviors. In multivariable analysis, women less likely to report adherent behaviors were Black (vs. White) (OR: 0.43, 95%, CI: 0.27–0.67, p<0.001) and with greater symptom burden (OR: 0.98, 95%, CI: 0.96–1.00,p<0.05). Participants more likely to be adherent were overweight (vs. normal weight) (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.04–2.43, p<0.05), sat ≤ 6 hours a day (vs.≤ 6 hours) (OR:1.83, 95% CI: 1.25–2.70, p<0.01), and were taking aromatase inhibitors (vs. Tamoxifen)(OR: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.28–2.87, p<0.01).

Conclusion:

Racial differences in AET adherence were observed. Longitudinal assessments of symptom burden are needed to better understand this dynamic process and factors that may explain differences in survivor subgroups.

Impact:

Future interventions should prioritize Black survivors and women with greater symptom burden.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy, Symptoms, Disparities, Adherence

Introduction

Adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) has made dramatic progress in the treatment of hormonal receptor positive (HR+) breast cancer (BC). Thus, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends AET [tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors] for hormone receptor positive (HR+) breast cancer (BC).1, 2 Adherence to the full course of AET (≤5 years) is critical to reduce the risk of BC recurrence by 40% and to improve mortality by 31%.3, 4 Despite these benefits, up to 50% of women prematurely discontinue AET. Given the high rate of premature treatment discontinuation during the minimum 5-year course, identifying women at risk of discontinuation (i.e. non-adherence) early in their treatment regimen may provide insight to inform timely interventions.5, 6 Additionally, non-adherence to daily AET regimens is suboptimal and ranges from 50% to 91%.5, 7

Medication adherence is “the process by which medication is taken as prescribed and encompasses phases of ‘initiation’ (i.e., first dose), ‘implementation’ (taking prescribed doses and taking doses for required length of time) and ultimately ‘discontinuation’.8 Non-adherence in these phases is linked to poor outcomes.9 Explanations for non-adherence behaviors are complex and vary depending on the phase (e.g., implementation, discontinuation, etc.).10, 11 Thus, it is important to have studies that examine adherence across the spectrum of behaviors. AET medication related symptoms, such as hot flushes or bone pain, are commonly reported reasons for non-adherence,12, 13 yet many large-scale adherence studies have not captured patients’ reported symptoms or implementation behaviors in samples that include substantial numbers of minority women.14–16 As a result, little is known about symptom burden in minority women prescribed AET.

Though not always consistent across studies, reports suggest that African American (Black) women, are more likely to be non-adherent than their Non-Hispanic White (White) counterparts.17–19 Suboptimal AET adherence in Black women is characterized by lower rates of treatment initiation, greater delays to initiate therapy after prescription (implementation), and failure to complete the full course of therapy (persistence).20, 21 However, little is known about Black women’s adherence to their treatment regimens; particularly early in their treatment experience or whether if accounting for medication (i.e., symptom burden) and psychosocial factors such as medication beliefs would diminish some of the previously observed disparities. Addressing these areas will aid in the development of future interventions that seek to improve AET adherence. This report will fill important gaps regarding implementation adherence behaviors among Black and White women to inform interventions that can be implemented early in their treatment course. Using a multifaceted framework of adherence, aims are to: 1) test differences in adherence by race, 2) identify factors related to adherence and 3) understand how symptoms impact AET adherence.

Materials and Methods

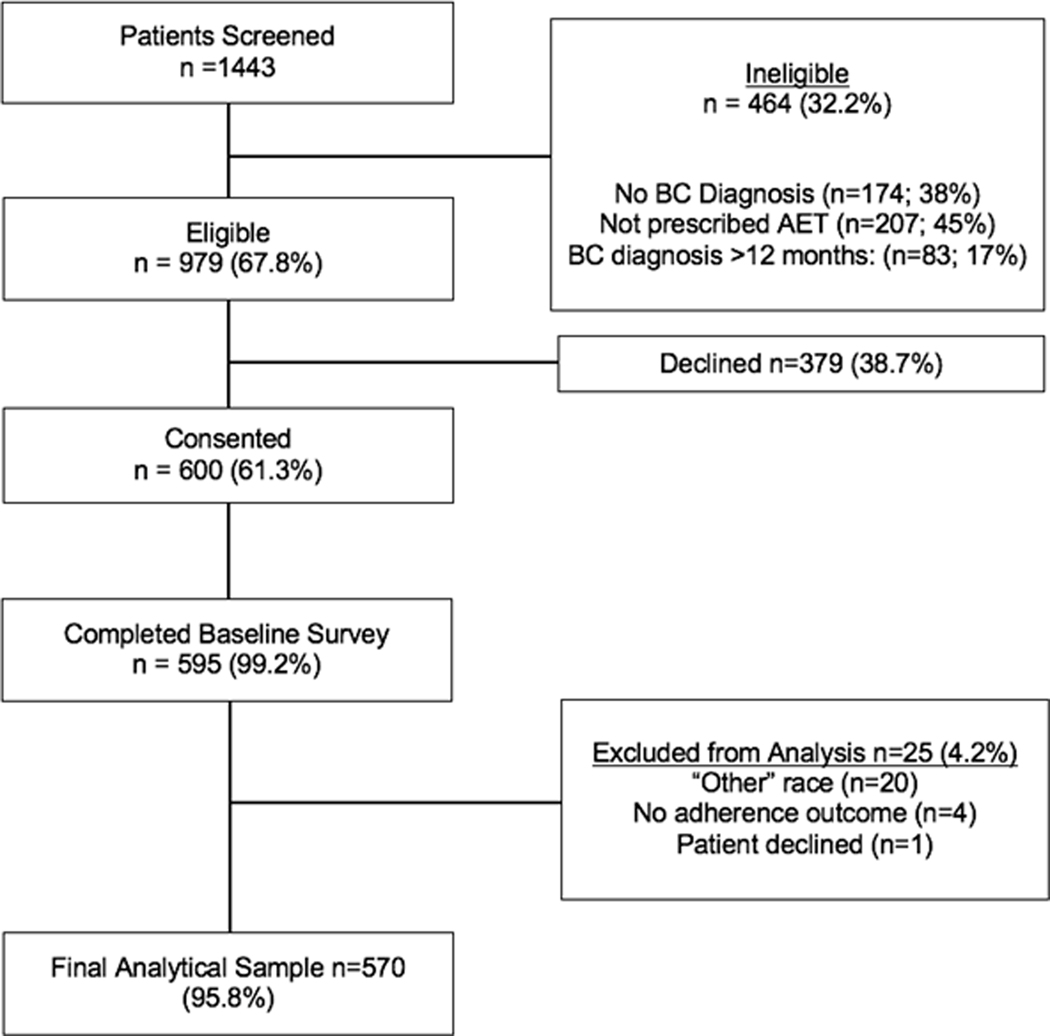

The Women’s Hormonal Initiation and Persistence (WHIP) study is a prospective study of Black and White women prescribed AET.22 This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov and approved by the institutional review boards (IRB) at participating sites and were conducted in accordance with recognized ethical guidelines; study protocols met the standards of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The study design, recruitment strategies, and study sample have been previously described.22 Briefly, eligibility criteria included being diagnosed with HR+ breast cancer within one-year of study enrollment, ≤21 years of age, and having filled a prescription script based on pharmacy records for any type of AET (e.g. tamoxifen) within one-year post-diagnosis and within three months of the baseline interview. Pharmacy records were used to confirm that women had current AET prescription at the time of interview. Trained clinical research assistants (CRA) screened and obtained written informed consent from patients. CRAs completed standardized computer-assisted telephone interviews with some women while others elected to complete the survey on-line via a secured link. As displayed in Figure 1, 1,443 women registered for the study; 464 were ineligible and 379 declined; 600 women consented and 595 completed baseline interviews (Figure 1). The analytical samples for this study focused solely on women who self-identified as either Black or White (N=570).

Figure 1.

WHIP Study Schema

Measures

Selection of measures was guided by our adaption of the Adherence Model by DiMatteo and colleagues and key domains from the WHO Medication Adherence Model.23, 24 The primary outcome of implementation adherence assessed if women missed a dose of their medications for reasons identified in prior literature 13, 25–28 and with validated items.29, 30 Unlike prescription-based adherence measures, such as proportion of days covered and medication possession ratio, our outcome offered insight to women’s experiences taking AET once in their possession. In other words, this measure assessed women’s medication taking behaviors. Participants answered three validated items (yes/no) adapted for our population regarding their medication adherence behaviors within the past two weeks. Queries included if they had stopped their medication due to several reasons (e.g., forgetting, feeling worse, or an inconvenience). Responses were yes versus no; yes responses were coded as “1” and No responses coded as “0.” Total scores ranged from 0 to 3 and the mean score was 0.5; therefore, we categorized the outcome for analysis as either “Adherent” (score = 0; no non-adherent behaviors) or ‘Nonadherent’ (scores = 1–3).

Medication-related factors

were key predictors of interest and included (1) AET drug class (Tamoxifen or Aromatase inhibitors [AI]) and (2) patient-reported AET-related symptoms. Patient-reported AET symptoms were assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Endocrine Symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha=0.79).31–33 The scale includes Likert items that asked how frequently they experienced symptoms in the seven days prior to survey completion. In accordance with published reports,34–36 symptoms were grouped according to five clusters; gastrointestinal symptoms (i.e., weight gain or loss, vomit, diarrhea, bloating, appetite increase, high cholesterol), gynecologic symptoms (i.e., vaginal discharge, vaginal itching/irritation, vaginal bleeding/spotting, vaginal dryness, pain or discomfort during intercourse, loss of interest in sex, breast sensitivity), neuropsychological symptoms (e.g. lightheadedness, dizziness, headaches, mood swings, irritability), vasomotor symptoms (e.g. hot flashes, cold sweats, night sweats), and bone symptoms (e.g. bone loss, joint pain or stiffness).

Individual patient-level factors

included demographic, clinicopathologic, psychosocial, and lifestyle factors. Demographic factors were age, race, income level (total household income before taxes), insurance type (public vs. private), and employment status (working vs. not working). Clinicopathologic factors were abstracted from medical records and included data on cancer stage, surgery type (lumpectomy, mastectomy), and therapy (radiation, hormonal). Psychosocial factors. Total self-efficacy was measured using a 12-item scale that assessed women’s level of confidence regarding understanding and obtaining health information (Cronbach’s alpha=0.87).37 We also employed two subscales of the self-efficacy scale – understanding and participating in care (Cronbach’s alpha=.72), and maintaining a positive attitude (Cronbach’s alpha=0.85). A three-item scale measured women’s health literacy, with higher scores indicating higher literacy (Cronbach’s alpha=0.76).38 Beliefs about AET were measured using the Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire (BMQ) 39 and were comprised of two subscales – perceived necessity of medication (e.g. my health in the future will depend on my endocrine therapy) (Cronbach’s alpha=0.84) and perceived concerns of taking medication (e.g. my endocrine therapy medications are a mystery to me) (Cronbach’s alpha=0.75). Spirituality was measured using Lukwago’s Religiosity Scale (Cronbach’s alpha=0.95).40 Social support and subdomains, emotional and tangible support, were assessed (Cronbach’s alpha=0.94, 0.94, and 0.92, respectively).41 Women reported their level of medical mistrust of the healthcare system using validated scales employed in cancer patients (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80).42 Lifestyle factors were measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).43 Physical activity was classified as low, moderate, or high based on Metabolic Equivalents (METS). Daily sitting time was classified by the median (>6 hours and ≤6 hours).

Cancer Care Delivery

variables included patients’ satisfaction, ratings regarding patient-provider communication, and overall trust in their cancer provider. The patient satisfaction questionnaire, which incorporates multiple domains (e.g. provider communication, access to care), was used to assess women’s levels of satisfaction with their care.44 An eight-item validated communication scale was adapted to measure women’s communication with the provider about AET 45 (Cronbach’s alpha=0.80). Lastly, women rated their trust in their doctors who provided their cancer care (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81).46

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (such as mean and standard deviation, relative frequency) were evaluated for each variable. T-tests were conducted to assess mean differences between AET adherence groups of continuous variables (e.g. religiosity), and chi-square tests were used to assess the relationships between AET adherence and categorical variables (e.g. race). Summary statistics and p-values are provided in Table 1. All variables in Table 1 superscripted with an ‘a’ were considered for inclusion in the logistic regression model; those selected to the final model are shown in the Table 3. A stepwise selection forcing the variables race, medication and Endocrine Symptom (ES) total score into the model was used to select variables. The Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to test model fit and AIC was used to compare the fit across models. All models led to a c-statistic of 0.68, indicating similar in-sample predictive performance. Interaction effects between race and ES total symptom score, between race and medication, and between medication and ES total symptom score were tested. The data analysis was based on the complete dataset. Data was treated as missing if less than 70% of item showed response. Furthermore, the analysis was repeated for each ES subscale score using the same procedure. All tests were based on a Type I error of 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (TS1M3).

Results

Sample Characteristics

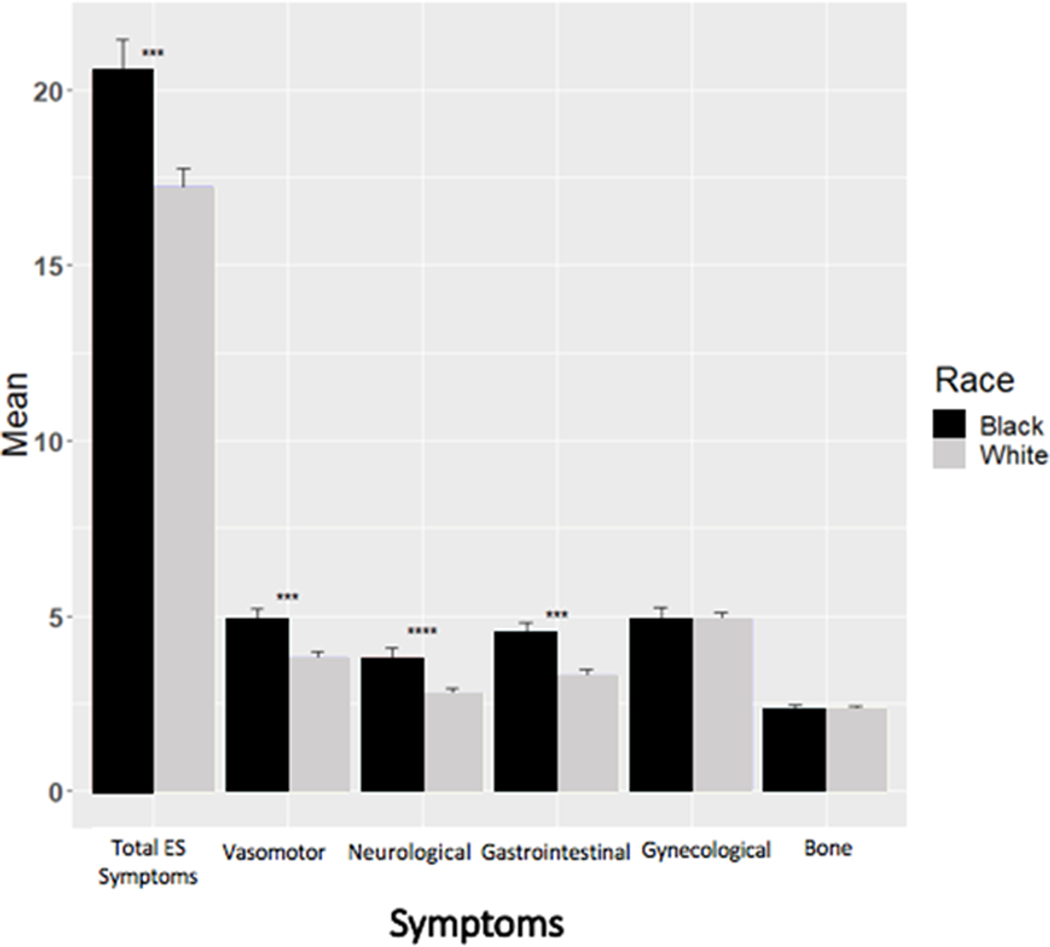

Participants’ ages ranged from 26 to 91 (mean=59, SD=11). Most were employed (58.7%), overweight (66.6%) and 69.5% reported moderate to high levels of physical activity (Table 1). Nearly a third of study participants were Black. Some differences were noted in sample characteristics by race (Table 2). Black participants tended to be younger (mean= 57.4 vs. 59.4, p=0.044) and be in a lower category of household income (67.5% vs. 43.0%, p<0.0001) than White patients. When compared to their White counterparts, fewer Black women were privately insured (88.2% vs. 93.5%; p=0.048), were married (46.3% vs. 71.4%, p<0.0001), and had college levels of education or higher (80.9% vs. 87.8%, p=0.033). Compared to white women, more black women had chemotherapy (48.3% vs. 36.2%, p=0.011) and had a higher BMI (mean=32.1 vs. 27.3, p<0.0001). Regarding symptom burden, Black women reported greater overall symptoms (mean= 20.5 vs. 17.2, p=0.0023), vasomotor (mean = 4.9 vs. 3.8, p=0.0018), neuropsychological (mean= 3.8 vs. 2.8, p=0.0017), and gastrointestinal (mean= 4.5 vs. 3.3, p=0.0015) symptoms. No differences in bone or gynecological symptom severity were found by race (p>.05).

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics by medication adherence (N=570)

| Medication Adherence |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

Nonadherent (N=203) |

Adherent (N=367) |

|

|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p-value | |

| Racea | ||||

| Black | 162 (28.4) | 78 (48.1) | 84 (51.9) | <0.001 |

| White | 408 (71.6) | 125 (30.6) | 283 (69.4) | |

| Agea | ||||

| 50+ years | 438 (76.8) | 136 (31.1) | 302 (68.9) | <0.001 |

| ≤50 years | 132 (23.2) | 67 (50.8) | 65 (49.2) | |

| Insurance | ||||

| Both | 22 (4.3) | 7 (31.8) | 15 (68.2) | 0.38 |

| Private | 470 (92.0) | 170 (36.2) | 300 (63.8) | |

| Public | 19 (3.7) | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | |

| Marriage | ||||

| Married or living with a partner | 365 (64.3) | 129 (35.3) | 236 (64.7) | 0.99 |

| Single | 203 (35.7) | 72 (35.5) | 131 (64.5) | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than college | 80 (14.2) | 30 (37.5) | 50 (62.5) | 0.81 |

| College or higher | 483 (85.8) | 171 (35.4) | 312 (64.6) | |

| Incomea | ||||

| <100,000/year | 267 (49.9) | 101 (37.8) | 166 (62.2) | 0.51 |

| ≥100,000/year | 268 (50.1) | 93 (34.7) | 175 (65.3) | |

| Home | ||||

| Apartment | 49 (9.2) | 20 (40.8) | 29 (59.2) | 0.44 |

| House | 485 (90.8) | 166 (34.2) | 319 (65.8) | |

| Working Statusa | ||||

| No | 224 (41.3) | 60 (26.8) | 164 (73.2) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 318 (58.7) | 133 (41.8) | 185 (58.2) | |

| Stage | ||||

| I | 308 (59.8) | 103 (33.4) | 205 (66.6) | 0.19 |

| II | 164 (31.8) | 63 (38.4) | 101 (61.6) | |

| III | 43 (8.3) | 20 (46.5) | 23 (53.5) | |

| Surgery type | ||||

| Lumpectomy | 237 (51.1) | 77 (32.5) | 160 (67.5) | 0.62 |

| Mastectomy | 198 (42.7) | 76 (38.4) | 122 (61.6) | |

| Both | 25 (5.4) | 11 (44.0) | 14 (56.0) | |

| No surgery | 4 (0.8) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Chemotherapya | ||||

| Yes | 211 (39.5) | 89 (42.1) | 122 (57.8) | 0.024 |

| No | 323 (60.5) | 104 (32.2) | 219 (67.8) | |

| Radiation | ||||

| Yes | 340 (67.2) | 124 (36.5) | 216 (63.5) | 0.614 |

| No | 166 (32.8) | 56 (33.7) | 110 (66.3) | |

| Medicationa | ||||

| AIs | 350 (61.8) | 102 (29.1) | 248 (70.9) | <0.001 |

| Tamoxifen | 216 (38.2) | 100 (46.3) | 116 (53.7) | |

| BMIa | ||||

| Overweight or Obese | 355 (66.6) | 124 (34.9) | 231 (65.1) | 0.368 |

| Underweight or Normal | 178 (33.4) | 70 (39.3) | 108 (60.7) | |

| Physical Activity Level | ||||

| Low | 163 (30.5) | 60 (36.8) | 103 (63.2) | 0.900 |

| Moderate | 280 (52.4) | 102 (36.4) | 17 (63.6) | |

| High | 91 (17.1) | 31 (34.1) | 60 (65.9) | |

| Daily sitting timea | ||||

| ≤ 6 hours | 327 (57.4) | 94 (28.7) | 233 (71.3) | <0.001 |

| > 6 hours | 243 (42.6) | 109 (44.9) | 134 (55.1) | |

| Distressa | ||||

| Under control | 321 (56.8) | 97 (30.2) | 224 (69.8) | 0.009 |

| Some distress | 168 (29.7) | 70 (41.7) | 98 (58.3) | |

| High level of distress | 76 (13.5) | 34 (44.7) | 42 (55.3) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value | |

| Age | 58.9(11.0) | 55.9 (11.1) | 60.5 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI | 28.7 (7.5) | 28.8 (7.3) | 28.6 (7.6) | 0.817 |

| Self-efficacya | 44.7 (4.0) | 44.3 (4.3) | 44.9 (3.9) | 0.098 |

| Understand Participate in Care | 15.0 (1.4) | 14.9 (1.5) | 15.1 (1.4) | 0.046 |

| Maintain Positive Attitude | 14.4 (2.0) | 14.3 (2.1) | 14.5 (2.0) | 0.242 |

| Obtaining information | 15.2 (1.4) | 15.2 (1.6) | 15.3 (1.4) | 0.293 |

| Medication Concernsa | 11.2 (2.9) | 11.7 (3.1) | 10.9 (2.8) | 0.001 |

| Medication Necessitya | 13.9 (3.0) | 13.5 (2.9) | 14.1 (3.1) | 0.027 |

| Religiosity | 26.7 (7.5) | 27.7 (7.2) | 26.2 (7.7) | 0.018 |

| Health Literacy Screeninga | 0.9 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.6) | 0.8 (1.6) | 0.193 |

| Perceived Severitya | 37.5 (14.4) | 38.3 (14.0) | 37.0 (14.6) | 0.307 |

| Perceived Susceptibilitya | 37.8 (16.4) | 39.0 (15.9) | 37.1 (16.7) | 0.2 |

| Social support | 81.8 (18.2) | 79.6 (18.9) | 83.0 (17.8) | 0.031 |

| Emotional Supporta | 82.4 (18.5) | 80.8 (18.8) | 83.4 (18.2) | 0.106 |

| Tangible Supporta | 80.5 (23.6) | 77.4 (24.9) | 82.2 (22.7) | 0.02 |

| Trust in primary carea | 78.6 (15.1) | 76.8 (14.4) | 79.6 (15.5) | 0.04 |

| Communicationa | 33.9 (4.9) | 33.3 (5.1) | 34.2 (4.7) | 0.025 |

| Medical Mistrusta | 20.4 (4.9) | 20.2 (4.5) | 20.4 (5.1) | 0.639 |

| Total Endocrine Symptoms | 18.2 (11.3) | 20.2 (11.0) | 17.0 (11.3) | 0.001 |

| Vasomotor Symptoms | 4.1 (3.7) | 4.4 (3.4) | 3.9 (3.8) | 0.128 |

| Neuropsychological Symptoms | 3.1 (3.0) | 3.5 (3.0) | 2.9 (3.0) | 0.014 |

| Gastrointestinal Symptoms | 3.7 (3.4) | 3.9 (3.4) | 3.5 (3.4) | 0.152 |

| Gynecological Symptoms | 4.9 (3.9) | 5.8 (4.1) | 4.4 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Bone Symptoms | 2.3 (1.9) | 2.4 (2.1) | 2.3 (1.9) | 0.614 |

Note: N=sample size; SD=standard deviation

Percentages are by columns for all participants and by rows across medication adherence.

T-tests used for continuous variables and chi-square tests used for categorical variables

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

represents the variables considered for inclusion in the logistic regression model and had to earn their way into the models with stepwise selection.

Table 2:

Descriptive statistics by Race (N=570)

| Race |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Black (N=162) |

White (N=408) |

|

|

| N (%) | N (%) | p-value | |

| Age | |||

| 50+ years | 118 (72.8) | 320 (78.4) | 0.15 |

| ≤50 years | 44 (27.2) | 88 (21.6) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Both | 7 (4.9) | 15 (4.1) | 0.048* |

| Private | 127 (88.2) | 343 (93.5) | |

| Public | 10 (6.9) | 9 (2.4) | |

| Working Status | |||

| No | 60 (40.0) | 164 (41.8) | 0.7 |

| Yes | 90 (60.0) | 228 (58.2) | |

| Distress | |||

| Under control | 88 (55.3) | 233 (57.4) | 0.29 |

| Some distress | 44 (27.7) | 124 (30.5) | |

| High level of distress | 27 (17.0) | 49 (12.1) | |

| Medication | |||

| AIs | 96 (60.4) | 254 (62.4) | 0.65 |

| Tamoxifen | 63 (39.6) | 153 (37.6) | |

| BMI (categorized) | |||

| Overweight or Obese | 130 (86.7) | 225 (58.7) | <0.0001*** |

| Underweight or Normal | 20 (13.3) | 158 (41.3) | |

| Physical Activity Level | |||

| Low | 57 (38.5) | 106 (27.5) | 0.0065* |

| Moderate | 76 (51.4) | 204 (52.8) | |

| High | 15 (10.1) | 76 (19.7) | |

| Stage | |||

| I | 72 (52.9) | 231 (64.0) | 0.075 |

| II | 51 (37.5) | 101 (28.0) | |

| III | 13 (9.6) | 29 (8.0) | |

| Surgery type | |||

| Lumpectomy | 55 (42.3) | 182 (54.5) | 0.18 |

| Mastectomy | 65 (50.0) | 133 (39.8) | |

| Both | 8 (6.2) | 17 (5.1) | |

| No surgery | 2 (1.5) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 71 (48.3) | 140 (36.2) | 0.011* |

| No | 76 (51.7) | 247 (63.8) | |

| Radiation | |||

| Yes | 87 (64.4) | 253 (68.2) | 0.43 |

| No | 48 (35.6) | 118 (31.8) | |

| Daily sitting time | |||

| ≤ 6 hours | 90 (55.6) | 237 (58.1) | 0.58 |

| > 6 hours | 72 (44.4) | 171 (41.9) | |

| Marriage | |||

| Married or living with a partner | 75 (46.3) | 290 (71.4) | <0.0001*** |

| Single | 87 (53.7) | 116 (28.6) | |

| Education | |||

| Less than college | 31 (19.1) | 49 (12.2) | 0.033* |

| College or higher | 131 (80.9) | 352 (87.8) | |

| Income | |||

| <100,000/year | 102 (67.5) | 165 (43.0) | <0.0001*** |

| >=100,000/year | 49 (32.5) | 219 (57.0) | |

| Home | |||

| Apart | 30 (20.0) | 19 (4.9) | <0.0001*** |

| House | 120 (80.0) | 365 (95.1) | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p-value | |

| Age | 57.4 ± 11.6 | 59.4 ± 10.8 | 0.044* |

| BMI | 32.1 ± 7.1 | 27.3 ± 7.3 | <0.0001*** |

| Self-efficacy | 45.0 ± 3.4 | 44.6 ± 4.3 | 0.32 |

| Understand Participate in Care | 14.9 ± 1.3 | 15.1 ± 1.5 | 0.25 |

| Maintain Positive Attitude | 14.7 ± 1.8 | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 0.038* |

| Obtaining information | 15.3 ± 1.3 | 15.2 ± 1.5 | 0.29 |

| Medication Concerns | 11.8 ± 3.1 | 10.9 ± 2.9 | 0.0012** |

| Medication Necessity | 14.1 ± 3.0 | 13.8 ± 3.0 | 0.29 |

| Religiosity | 32.2 ± 4.2 | 24.6 ± 7.5 | <0.0001*** |

| Health Literacy Screening | 1.3 ± 2.0 | 0.7 ± 1.4 | <0.0001*** |

| Perceived Severity | 40.9 ± 13.3 | 36.2 ± 14.6 | 0.0005*** |

| Perceived Susceptibility | 35.4 ± 15.4 | 38.7 ± 16.8 | 0.035* |

| Social support | 83.3 ± 18.0 | 81.1 ± 18.3 | 0.2 |

| Emotional Support | 83.7 ± 18.0 | 81.9 ± 18.7 | 0.3 |

| Tangible Support | 82.8 ± 23.2 | 79.6 ± 23.7 | 0.15 |

| Trust in primary care | 76.0 ± 15.6 | 79.6 ± 14.8 | 0.0092*** |

| Communication | 33.0 ± 4.5 | 34.2 ± 5.0 | 0.0076** |

| Medical Mistrust | 22.1 ± 5.2 | 19.7 ± 4.6 | <0.0001*** |

| Total Endocrine Symptoms | 20.5 ± 11.7 | 17.2 ± 11.0 | 0.0023* |

| Vasomotor Symptoms | 4.9 ± 3.6 | 3.8 ± 3.7 | 0.0018** |

| NeuropsychologicalNeuropsychological Symptoms | 3.8 ± 3.3 | 2.8 ± 2,8 | 0.0017** |

| Gastrointestinal Symptoms | 4.5 ± 3.7 | 3.3 ± 3.2 | 0.0015** |

| Gynecological Symptoms | 4.9 ± 3.9 | 4.9 ± 4.0 | 0.94 |

| Bone Symptoms | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.3 ± 2.0 | 0.88 |

Note: N=sample size; SD=standard deviation

T-tests were used for continuous variables and chi-square tests were used for categorical variables

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

AET Adherence

Most (65.0%) women did not report any non-adherent behaviors. For the remaining women, 22.2% reported one nonadherent behavior, 11.2% reported 2 nonadherent behaviors, and 1.6% reported three nonadherent behaviors.. The most common non-adherent behavior was due to forgetting to take medications (26.4%) followed by missing their medications for reasons other than forgetting (17,3%). It was uncommon for women to cite non-adherence due to feeling worse after taking their medication (5.4%).

Women who were adherent reported lower scores of overall AET symptoms (mean=17.0 vs. 20.2, p=0.001) (Table 1). Medication type was associated with regimen adherence, with women on AIs having higher adherence compared to women on tamoxifen (70.9% vs. 53.7%; p<.0001). Several patient-level factors were associated with regimen adherence. White women and women over 50 years of age were more likely to be adherent compared to women who were Black and 50 years old and younger (69.4% vs. 51.9%, p<0.001 and 68.9% vs. 49.2%, p<0.001, respectively). Compared to women who were employed, those who were not working were more likely to be adherent (73.2% vs. 58.2%, p<0.0001). No association was observed between adherence and type of surgery or receipt of radiation, but women who received chemotherapy were less likely to be adherent compared to those without chemotherapy (57.8% vs. 67.8%, p=0.0241). Although physical activity was not associated with adherence, adherence was higher among women with ≤ 6 hours per day of sitting than those with > 6 hours per day of sitting (71.3% vs. 55.1%, p<0.001).

Several psychosocial factors were associated with adherence, including tangible support (p=0.020), medication necessity beliefs (p=0.027), medication concerns (p=0.001), and religiosity (p=0.018). Women’s ratings of their communication with their provider was associated with regimen adherence (p=0.025).

Table 3 displays six multivariable models for adherence that includes a model adjusting for overall AET symptoms and models accounting for each of the specific five symptom domains (vasomotor, neuropsychological, gynecologic, gastrointestinal, and bone). Each model assessed the odds of adherence (ref: nonadherence). Findings from all models revealed that Black women were less likely to be adherent when compared to White women. For example, in the model that included total AET symptoms, Black women were less likely to be adherent than White women (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.27 to 0.67; p<0.0001). Medication type was significant in all models; women taking AI were more likely to be adherent than those taking Tamoxifen (OR=1.91, 95% CI: 1.28 to 2.87; p < 0.01). Overweight women had a higher odds of adherence compared to normal weight women (OR=1.58, 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.43; p<0.05). Women who were unemployed were more likely to be adherent than employed women (OR=1.57, 95% CI: 1.03 to 2.40; p<0.05).

Table 3:

Multivariable Logistic regression Models for Adherence by AET Symptom Domains

| Odds ratio estimates (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary model | Subset models | |||||

| Parameters | Total Endocrine Symptoms | Vasomotor Symptoms | Neuropsychological Symptoms | Gynecologic Symptoms | Gastrointestinal Symptoms | Bone Symptoms |

| Symptom score | 0.98 (0.96, 0.995)* | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 0.93 (0.87,0.994)* | 0.92 (0.87, 0.96)*** | 0.96 (0.91, 1.02) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.11) |

| Race (Black vs White) | 0.43 (0.27, 0.67)*** | 0.43 (0.28, 0.68)*** | 0.42 (0.27, 0.66)*** | 0.42 (0.27,0.65)*** | 0.42 (0.27,0.78)*** | 0.46 (0.27, 0.78)** |

| Working status (No vs. Yes) | 1.57 (1.03,2.40)* | 1.65 (1.08, 2.52)* | 1.60 (1.05, 2.44)* | 1.62 (1.06, 2.47)* | 1.62 (1.06,2.46)* | - |

| Medication (AI vs. Tamoxifen) | 1.91 (1.28, 2.87)** | 1.95 (1.29, 2.94)** | 1.94 (1.29,2.93)** | 1.98 (1.31, 2.98)** | 1.92 (1.28,2.88)** | 2.59 (1.52, 4.40)*** |

| BMI (Overweight vs. Normal) | 1.58 (1.04, 2.43)* | 1.50 (0.98, 2.30) | 1.50 (0.98, 2.29) | 1.43 (0.93, 2.18) | 1.59 (1.03,2.44)* | - |

| Daily sitting time (≤6 hours vs. >6 hours) | 1.83 (1.25, 2.70)** | 1.77 (1.20, 2.62)** | 1.86 (1.27, 2.74)** | 1.78 (1.21,2.63)** | 1.83 (1.24, 2.68)** | 2.01 (1.22,3.32)** |

| Chemotherapy (No vs. Yes) | - | - | - | - | - | 1.62 (0.94, 2.71) |

| Medication Concerns | - | 0.92 (0.86, 0.99)* | - | - | ||

| Goodness-of-Fit (p-value) | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.88 | 0.57 | 0.39 |

| AIC | 660.80 | 650.93 | 657.88 | 657.88 | 662.63 | 395.52 |

| C-statistic | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

Note: Each model controls for race, age, medication and Total Endocrine symptoms or one of the endocrine symptom subscales by default. Stepwise selection was performed in order to determine the inclusion of additional variables.

CI=confidence interval

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Greater symptom burden was negatively associated with adherence in the total AET symptom and gynecological symptom logistic regression models. For example, in the AET total model the odds of being adherent decreased by a factor of 0.98 for every 1 unit increase in AET total symptoms (95% CI: 0.96 to 1.00; p<0.05), while in the AET gynecologic model, the odds of being adherent decreased by a factor of 0.92 for every 1 unit increase in AET gynecologic symptoms (95% CI: 0.87 to 0.96; p<0.0001).

Only one psychosocial factor was associated with adherence. Beliefs about AET medication, specifically concern beliefs, was significant in the vasomotor model only. Higher concern beliefs were associated with lower odds of adherence (OR=0.92, 95% CI: 0.86 to 0.99; p<0.05). While physical activity was not associated with adherence, women who sat for ≤ 6 hours a day were more likely to adhere to AET in all models.

Discussion

This observational study examined numerous factors that have been hypothesized to be associated with AET adherence in largely White samples but relatively unexamined within the context of racial disparities in adherence. Most of the foundational work related to AET adherence has been drawn from largely administrative data sources.14–16, 47 Guided by our adapted Adherence Model by Bastani and colleagues,23 this study expands the scope of factors generally examined by collecting data related to patient reported symptoms, psychosocial variables (e.g., medication beliefs, medical mistrust), perceptions of cancer care delivery, and lifestyle factors (physical activity, sitting time). We observed notable differences in regimen adherence behaviors by race, medication-related symptoms, and type of medication that persisted in multivariable models. No interaction effect between race and each symptom domain, or between race and medication, or between medication and each symptom was statistically significant in the models relating symptoms to adherence. Inclusion of data about lifestyle factors suggested opportunities to examine the relationship between BMI, sitting time and adherence among women taking AET. Study findings enhance knowledge about Black women with HR+ BC taking AET and have implications for future approaches to improve cancer prevention and control for BC survivors.

Addressing adherence to AET among Black women will be important for future research and clinical practice. Racial disparities have been reported in some studies of adherence outcomes based on pharmacy and medical records,48, 49 but limited information has been available about women’s reports of their adherence related to their medication behaviors. We found that in contrast to their White peers, Black women were less likely to be adherent when controlling for AET symptoms. While results about racial disparities in AET adherence have been mixed, particularly in Medicare insured samples,7 findings are in concert with those that found that Black women had higher rates of non-persistence.11 Explanations of lower pharmacy fills have been attributed in part to financial factors, specifically, lacking insurance or an inability to pay a copay.20, 50 In our sample of largely insured women we did not find evidence related to the financial factors measured in our study (e.g., income, concerns about medication affordability). While our findings are in line with those that have relied on pharmacy records to assess prescription refill rates, limited studies have compared racial/ethnic differences in patients’ adherence to their daily regimen. Regimen adherence is important because even if women have filled their prescriptions, they may fail to take the medication as prescribed for various reasons (forgetting, etc.).

Although medication symptoms are often widely cited as a reason for premature discontinuation,12, 13 there have been relatively few studies that have empirically examined this relationship outside of clinical trials particularly, in samples that include Black women 51 and limited information is available about relationships of symptom severity with AET adherence behaviors. Our study filled research gaps in these areas. The presence of more severe AET symptoms was associated with non-adherence. While studies have focused on the presence (vs. absence) of symptoms 52, 53 there is emerging data providing information about symptom severity. 52 In our sample of women, overall severity of AET-related symptoms including, neuropsychological and gynecological symptoms were significantly related to adherence. In the model that included total AET symptoms, the odds of Black survivors’ adherence was 56% less than that of White women. These findings warrant future examination to understand the onset of symptoms and symptom management by race, which were beyond the scope of this study (Figure 2). Conversely, Bowels and colleagues found that while most women reported AET-related symptoms, most of those symptoms were not associated with AET non-adherence.54 It is possible that severity of effects may relate more to adherence behaviors than the actual presence or absence of a side effect; however, supporting evidence is mixed 55 and deserves further exploration. Moreover, women may also have differential thresholds that could be influenced by numerous other factors.

Figure 2.

AET Symptom Severity by Race

Figure 2.: ES total and subscale scores by race. Y-axis shows the mean of ES total and subscale scores. The bar represents standard error. The red represents Black patients, and the blue represents White patients. The x-axis is labelled by the name of ES total and subscales symptoms. T-tests are performed.

* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Symptom management is critical in the administration of AET yet empirical data are lacking about its influence on AET adherence. However, Blanchette and colleagues reported that survivors who had a follow-up with their medical oncologists within 4 months of initiating AET were more likely to be high adherers than women who did not. Additionally, measures of symptom management range from a woman’s perception of her control over the symptoms 56, 57 to having a physician’s permission to terminate treatment.58 We did not collect information on how patients and/or physicians managed AET-related symptoms in this study. We did however, assess women’s perceptions of their self-efficacy to manage aspects of their treatment, and interpersonal aspects of care, both of which were significant in bivariate but not in multivariable analyses.

Novel findings related to weight and sedentary behavior were noted in the sample. Women who were overweight or obese and women who are less sedentary were more likely to be adherent. There are several possible explanations for these findings. First, weight gain is a known side effect of AET.59, 60. More work in this area is needed to understand the complex relationship between weight and symptoms.

While several factors (i.e., social support) were associated with medication taking behaviors among study participants in bivariate analysis, the strength of these relationships was diminished in multivariable models.11 Women’s health beliefs and attitudes toward AET influenced their medication adherence behaviors. Negative attitudes and greater AET concerns are found to be associated with lower adherence, 61 while positive attitudes are positively associated with adherence.62 Surprisingly, during the early stages of their treatment regimen, interpersonal aspects of care (e.g. communication) were not strongly associated with regimen adherence. Reports on patient-provider communication and other interpersonal factors have been inconsistent across studies.63 Lower self-efficacy in physician communication was negatively associated with adherence.64 Poorer relationships with oncologists are also reported to relate with non-adherence.61 Provision of information from providers about side effects has been found to be important to women. Qualitative data from Hurtado and colleagues suggested that women reported that they were unprepared about potential side effects, and would have preferred that their providers prepare them for potential issues but more empirical data are needed in this area.65 One study of multidisciplinary providers who prescribe AET found that while providers have conversations with their patients about side effects and side effect management, they express concern that there are no widely available systematic side effect assessment tools which contributes to the variation in care BC patients may receive with regard to their AET.66 Conversely, in another qualitative study, providers were not particularly concerned about non-adherence although, side effects, considered a rarity, were attributed to non-adherence.67 Additional research is needed to understand communication patterns between providers and patients, specifically with regard to adherence and side effects. Further, there is a need to understand the type of information shared with patients and the ways in which this information is presented.

This study has several strengths such as 1) inclusion of substantial proportion of both black and white survivors in the sample, 2) collection of groups of factors hypothesized to be associated with adherence as well as variables reported to be significant in other studies, inclusion of factors not-previously collected in diverse samples, 3) focus on both regimen adherence and AET-symptoms, and 4) measurement of sociocultural factors and patient-reported symptoms in a diverse population of women with breast cancer. There are limitations in our study that should be acknowledged. First, most study participants (89.6%) were insured; therefore, results may not be generalizable to uninsured or underinsured populations. Additionally, our sample is limited to black and white women, limiting the ability to assess adherence in other ethnic or racial groups (e.g. Latinas, Asians). Finally, the study did not include other measures of adherence such as persistence or discontinuation from pharmacy records. However, initiation of AET was confirmed via pharmacy reports and the purpose of this study was to examine medication taking behaviors. Important next steps will be to examine multiple dimensions of adherence.

AET adherence is a modifiable factor to reduce morbidity and mortality in breast cancer survivors. To better address AET non-adherence, a full picture of the continuum of adherence behaviors at differential time-periods during the course of treatment is crucial. This can inform appropriate intervention changes as adherence likely changes over time, and is influenced by different factors pending the treatment course. Addressing early non-adherence behaviors may provide an opportunity to mitigate long-term problems of persistence. The impact of symptoms on adherence and the higher symptom report among black women need further investigation. Interventions to manage symptoms and address racial differences are needed.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute R01CA154848 (to V.B. Sheppard). It was also funded, in part by NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA016059), NCI T32CA093423 (to V.B. Sheppard and A.L. Sutton), and by the VCU Center for Clinical and Translational Science Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program (UL1TR002649). Effort on this project was also supported by the Georgetown-Howard Universities CTSA KL2TR001432 (to A. Hurtado-de-Mendoza).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, E., Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet (London, England) 2005, 365 (9472), 1687–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer, N., NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandelblatt JS; Cronin KA; Bailey S; Berry DA; de Koning HJ; Draisma G; Huang H; Lee SJ; Munsell M; Plevritis SK; Ravdin P; Schechter CB; Sigal B; Stoto MA; Stout NK; van Ravesteyn NT; Venier J; Zelen M; Feuer EJ; Breast Cancer Working Group of the Cancer, I.; Surveillance, Effects of mammography screening under different screening schedules: model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009, 151 (1539–3704; 0003–4819; 10), 738–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Society AC Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019–2020; 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chlebowski RT; Geller ML, Adherence to endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Oncology 2006, 71 (0030–2414; 1–2), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luschin G; Habersack M, Oral information about side effects of endocrine therapy for early breast cancer patients at initial consultation and first follow-up visit: an online survey. Health Commun 2014, 29 (4), 421–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershman DL; Shao T; Kushi LH; Buono D; Tsai WY; Fehrenbacher L; Kwan M; Gomez SL; Neugut AI, Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment 2011, 126 (2), 529–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vrijens B; De Geest S; Hughes DA; Przemyslaw K; Demonceau J; Ruppar T; Dobbels F; Fargher E; Morrison V; Lewek P; Matyjaszczyk M; Mshelia C; Clyne W; Aronson JK; Urquhart J; Team, A. B. C. P., A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012, 73 (5), 691–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCowan C; Shearer J; Donnan PT; Dewar JA; Crilly M; Thompson AM; Fahey TP, Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. British journal of cancer 2008, 99 (11), 1763–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheppard VB; de Mendoza AH; He J; Jennings Y; Edmonds MC; Oppong BA; Tadesse MG, Initiation of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Black and White Women With Breast Cancer. Clinical breast cancer 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler SB; Spencer J; Pinheiro LC; Murphy CC; Earp JA; Carey L; Olshan A; Tse CK; Bell ME; Weinberger M; Reeder-Hayes KE, Endocrine Therapy Nonadherence and Discontinuation in Black and White Women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bright EE; Petrie KJ; Partridge AH; Stanton AL, Barriers to and facilitative processes of endocrine therapy adherence among women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016, 158 (2), 243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry NL; Azzouz F; Desta Z; Li L; Nguyen AT; Lemler S; Hayden J; Tarpinian K; Yakim E; Flockhart DA; Stearns V; Hayes DF; Storniolo AM, Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30 (9), 936–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hershman DL; Tsui J; Wright JD; Coromilas EJ; Tsai WY; Neugut AI, Household net worth, racial disparities, and hormonal therapy adherence among women with early-stage breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2015, 33 (9), 1053–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Partridge AH; Wang PS; Winer EP; Avorn J, Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003, 21 (0732–183; 4), 602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weaver KE; Camacho F; Hwang W; Anderson R; Kimmick G, Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy and its relationship to breast cancer recurrence and survival among low-income women. American journal of clinical oncology 2013, 36 (2), 181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheppard V, He J, Sutton AL, Cromwell L, Adunlin G, Salgado TM, Tolsma D. Trout M, Robinson BE, Edmonds MC, Bosworth HB, & Tadesse MG, Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Insured Black and White Breast Cancer Survivors: Exploring Adherence Measures in Patient Data. Journal of managed care & specialty pharmacy 2019. (In press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheppard VB; Faul LA; Luta G; Clapp JD; Yung RL; Wang JH; Kimmick G; Isaacs C; Tallarico M; Barry WT; Pitcher BN; Hudis C; Winer EP; Cohen HJ; Muss HB; Hurria A; Mandelblatt JS, Frailty and adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in older women with breast cancer: CALGB protocol 369901. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2014, 32 (22), 2318–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesmodel SB; Goloubeva OG; Rosenblatt PY; Heiss B; Bellavance EC; Chumsri S; Bao T; Thompson J; Nightingale G; Tait NS; Nichols EM; Feigenberg SJ; Tkaczuk KH, Patient-reported Adherence to Adjuvant Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy Using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale: An Evaluation of Predictors. Am J Clin Oncol 2018, 41 (5), 508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hershman DL; Kushi LH; Shao T; Buono D; Kershenbaum A; Tsai WY; al, e., Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2010, 28 (1527–7755; 0732–183; 27), 4120–4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimmick G; Anderson R; Camacho F; Bhosle M; Hwang W; Balkrishnan R, Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2009, 27 (21), 3445–3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheppard VB; Hurtado-de-Mendoza A; Zheng YL; Wang Y; Graves KD; Lobo T; Xu H; Jennings Y; Tolsma D; Trout M; Robinson BE; McKinnon B; Tadesse M, Biospecimen donation among black and white breast cancer survivors: opportunities to promote precision medicine. J Cancer Surviv 2018, 12 (1), 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gritz ER; Bastani R, Cancer prevention--behavior changes: the short and the long of it. Preventive medicine 1993, 22 (5), 676–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiMatteo MR; Hays RD; Gritz ER; Bastani R; Crane L; Elashoff R; Ganz P; Heber D; McCarthy W; Marcus A, Patient Adherence to Cancer Control Regimens: Scale Development and Initial Validation. Psychological assessment 1993, 5 (1), 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith SG; Sestak I; Howell A; Forbes J; Cuzick J, Participant-Reported Symptoms and Their Effect on Long-Term Adherence in the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study I (IBIS I). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2017, 35 (23), 2666–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nestoriuc Y; von Blanckenburg P; Schuricht F; Barsky AJ; Hadji P; Albert US; Rief W, Is it best to expect the worst? Influence of patients’ side-effect expectations on endocrine treatment outcome in a 2-year prospective clinical cohort study. Annals of Oncology 2016, 27 (10), 1909–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy CC; Bartholomew LK; Carpentier MY; Bluethmann SM; Vernon SW, Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012, 134 (2), 459–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihalko SL; Brenes GA; Farmer DF; Katula JA; Balkrishnan R; Bowen DJ, Challenges and innovations in enhancing adherence. Controlled clinical trials 2004, 25 (0197–2456; 0197–2456; 5), 447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wassermann J; Gelber SI; Rosenberg SM; Ruddy KJ; Tamimi RM; Schapira L; Borges VF; Come SE; Meyer ME; Partridge AH, Nonadherent behaviors among young women on adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Cancer 2019, 125 (18), 3266–3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stirratt MJ; Dunbar-Jacob J; Crane HM; Simoni JM; Czajkowski S; Hilliard ME; Aikens JE; Hunter CM; Velligan DI; Huntley K; Ogedegbe G; Rand CS; Schron E; Nilsen WJ, Self-report measures of medication adherence behavior: recommendations on optimal use. Transl Behav Med 2015, 5 (4), 470–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cella D; Fallowfield LJ, Recognition and management of treatment-related side effects for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast cancer research and treatment 2008, 107 (0167–6806; 2), 167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fallowfield LJ; Leaity SK; Howell A; Benson S; Cella D, Assessment of quality of life in women undergoing hormonal therapy for breast cancer: validation of an endocrine symptom subscale for the FACT-B. Breast cancer research and treatment 1999, 55 (2), 189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brady MJ; Cella DF; Mo F; Bonomi AE; Tulsky DS; Lloyd SR; Deasy S; Cobleigh M; Shiomoto G, Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 1997, 15 (3), 974–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mortimer JE, Managing the toxicities of the aromatase inhibitors. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology 2010, 22 (1), 56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dent SF; Gaspo R; Kissner M; Pritchard KI, Aromatase inhibitor therapy: toxicities and management strategies in the treatment of postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011, 126 (2), 295–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kyvernitakis I; Ziller V; Hars O; Bauer M; Kalder M; Hadji P, Prevalence of menopausal symptoms and their influence on adherence in women with breast cancer. Climacteric : the journal of the International Menopause Society 2014, 17 (3), 252–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolf MS; Chang CH; Davis T; Makoul G, Development and validation of the Communication and Attitudinal Self-Efficacy scale for cancer (CASE-cancer). Patient education and counseling 2005, 57 (0738–3991; 3), 333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chew LD; Bradley KA; Boyko EJ, Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 2004, 36 (0742–3225; 0742–3225; 8), 588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pellegrini I; Sarradon-Eck A; Ben Soussan P; Lacour AC; Largillier R; Tallet A; Tarpin C; Julian-Reynier C, Women’s perceptions and experience of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy account for their adherence: breast cancer patients’ point of view . Psycho-oncology 2009, (1099–1611; 1099–1611). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukwago SN; Kreuter MW; Bucholtz DC; Holt CL; Clark EM, Development and validation of brief scales to measure collectivism, religiosity, racial pride, and time orientation in urban African American women. Family & community health 2001, 24 (3), 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherbourne CD; Stewart AL, The MOS social support survey. Social science & medicine (1982) 1991, 32 (6), 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaVeist TA; Nickerson KJ; Boulware LE; Powe NR In The Medical Mistrust Index: A Measure of Mistrust of the Medical Care System, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee PH; Macfarlane DJ; Lam TH; Stewart SM, Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011, 8, 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gn M; Rd H, The patient satisfaction questionnaire short-form (PSQ-18), P-7865. 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makoul G; Arntson P; Schofield T, Health promotion in primary care: physician-patient communication and decision making about prescription medications. Social science & medicine (1982) 1995, 41 (9), 1241–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Safran DG; Kosinski M; Tarlov AR; Rogers WH; Taira DH; Lieberman N; Ware JE, The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Medical care 1998, 36 (5), 728–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farias AJ; Du XL, Racial differences in adjuvant endocrine therapy use and discontinuation in association with mortality among Medicare breast cancer patients by receptor status. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farias AJ; Du XL, Association Between Out-Of-Pocket Costs, Race/Ethnicity, and Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Adherence Among Medicare Patients With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017, 35 (1), 86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hershman DL; Tsui J; Wright JD; Coromilas EJ; Tsai WY; Neugut AI, Household net worth, racial disparities, and hormonal therapy adherence among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015, 33 (9), 1053–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nekhlyudov L; Li L; Ross-Degnan D; Wagner AK, Five-year patterns of adjuvant hormonal therapy use, persistence, and adherence among insured women with early-stage breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment 2011, 130 (2), 681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kidwell KM; Harte SE; Hayes DF; Storniolo AM; Carpenter J; Flockhart DA; Stearns V; Clauw DJ; Williams DA; Henry NL, Patient-reported symptoms and discontinuation of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy. Cancer 2014, 120 (16), 2403–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Y; Malin JL; Diamant AL; Thind A; Maly RC, Adherence to adjuvant hormone therapy in low-income women with breast cancer: the role of provider-patient communication. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013, 137 (3), 829–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan X; Camacho F; Marshall VD; Donohoe J; Anderson RT; Balkrishnan R, Geographic disparities in adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in Appalachian women with breast cancer. Res Social Adm Pharm 2017, 13 (4), 796–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aiello Bowles EJ; Boudreau DM; Chubak J; Yu O; Fujii M; Chestnut J; Buist DS, Patient-reported discontinuation of endocrine therapy and related adverse effects among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract 2012, 8 (6), e149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moon Z; Moss-Morris R; Hunter MS; Carlisle S; Hughes LD, Barriers and facilitators of adjuvant hormone therapy adherence and persistence in women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017, 11, 305–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wickersham K; Happ MB; Bender CM, “Keeping the Boogie Man Away”: Medication Self-Management among Women Receiving Anastrozole Therapy. Nursing research and practice 2012, 2012, 462121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pellegrini I; Sarradon-Eck A; Soussan PB; Lacour AC; Largillier R; Tallet A; Tarpin C; Julian-Reynier C, Women’s perceptions and experience of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy account for their adherence: breast cancer patients’ point of view. Psycho-oncology 2010, 19 (1099–1611; 1057–9249; 5), 472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harrow A; Dryden R; McCowan C; Radley A; Parsons M; Thompson AM; Wells M, A hard pill to swallow: a qualitative study of women’s experiences of adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. BMJ Open 2014, 4 (6), e005285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nyrop KA; Williams GR; Muss HB; Shachar SS, Weight gain during adjuvant endocrine treatment for early-stage breast cancer: What is the evidence? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016, 158 (2), 203–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Honma N; Makita M; Saji S; Mikami T; Ogata H; Horii R; Akiyama F; Iwase T; Ohno S, Characteristics of adverse events of endocrine therapies among older patients with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stanton AL; Petrie KJ; Partridge AH, Contributors to nonadherence and nonpersistence with endocrine therapy in breast cancer survivors recruited from an online research registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014, 145 (2), 525–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hershman DL; Kushi LH; Hillyer GC; Coromilas E; Buono D; Lamerato L; Bovbjerg DH; Mandelblatt JS; Tsai WY; Zhong X; Jacobson JS; Wright JD; Neugut AI, Psychosocial factors related to non-persistence with adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with breast cancer: the Breast Cancer Quality of Care Study (BQUAL). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016, 157 (1), 133–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin JJ; Chao J; Bickell NA; Wisnivesky JP, Patient-provider communication and hormonal therapy side effects in breast cancer survivors. Women Health 2017, 57 (8), 976–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kimmick G; Edmond SN; Bosworth HB; Peppercorn J; Marcom PK; Blackwell K; Keefe FJ; Shelby RA, Medication taking behaviors among breast cancer patients on adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2015, 24 (5), 630–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hurtado-de-Mendoza A; Jensen RE; Jennings Y; Sheppard VB, Understanding Breast Cancer Survivors’ Beliefs and Concerns About Adjuvant Hormonal Therapy: Promoting Adherence. J Cancer Educ 2018, 33 (2), 436–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turner K; Samuel CA; Donovan HA; Beckjord E; Cardy A; Dew MA; van Londen GJ, Provider perspectives on patient-provider communication for adjuvant endocrine therapy symptom management. Support Care Cancer 2017, 25 (4), 1055–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eraso Y, Oncologists’ perspectives on adherence/non-adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy and management strategies in women with breast cancer. Patient Prefer Adherence 2019, 13, 1311–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]