Abstract

Tissue engineering is an evolving multi-disciplinary field with cutting-edge technologies and innovative scientific perceptions that promise functional regeneration of damaged tissues/organs. Tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs) are biomaterial-cell products or a cell-drug combination which is injected, implanted or topically applied in the course of a therapeutic or diagnostic procedure. Current tissue engineering strategies aim at 3D printing/bioprinting that uses cells and polymers to construct living tissues/organs in a layer-by-layer fashion with high 3D precision. However, unlike conventional drugs or therapeutics, TEMPs and 3D bioprinted tissues are novel therapeutics and need different regulatory protocols for clinical trials and commercialization processes. Therefore, it is essential to understand the complexity of raw materials, cellular components, and manufacturing procedures to establish standards that can help to translate these products from bench to bedside. These complexities are reflected in the regulations and standards that are globally in practice to prevent any compromise or undue risks to patients. This review comprehensively describes the current legislations, standards for TEMPs with a special emphasis on 3D bioprinted tissues. Based on these overviews, challenges in the clinical translation of TEMPs & 3D bioprinted tissues/organs along with their ethical concerns and future perspectives are discussed.

Keywords: TEMPs, regulations & standards, 3D bioprinting, stem cells, ethical concerns, tissue engineering

Introduction

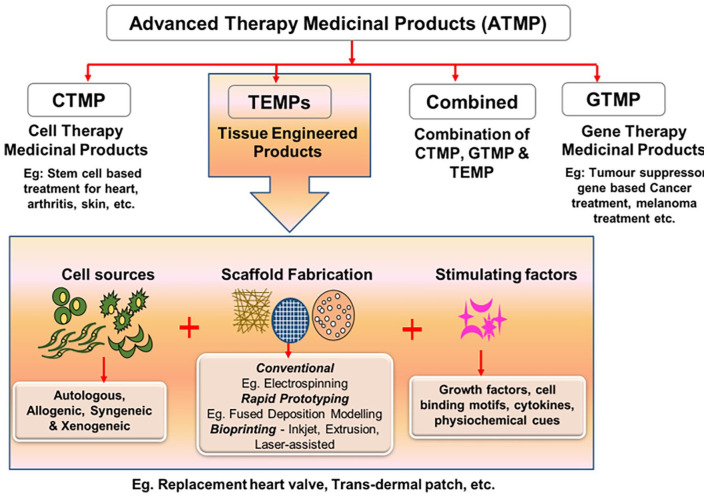

Tissue engineered products including naturally derived or synthetic biomaterial-based scaffolds with/without autologous or allogeneic cells are utilized to replace or restore the functions of damaged tissues and organs. 1 Advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) are considered as medicines for the treatment of disease or injuries in humans using genes, tissues or cells. ATMPs are classified into categories such as gene therapy medicinal products (GTMP), cell therapy medicinal products (CTMP), tissue-engineered medicinal products (TEMPs) and sometimes a combination of these categories. 2 In some countries like the US, a group of biological medicinal products are categorized as Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-based Product (HCT/P).1,3 ATMPs have several applications in the clinical arena to improve the quality of patients life. Organ transplantation is the terminal-stage treatment strategy for conditions like myocardial infarction, acute liver failure, chronic kidney disease, and Type 1 diabetes, etc. and may replace the need for TEMPs 4 However, shortage of organ donors, high cost and immunological complications limit the affordability and clinical success of organ transplantation around the globe.5,6 Thus, there is a need for artificial organ fabrication through tissue engineering approaches to overcome the limitations of organ transplantation. 7 Although various approaches have been used to develop engineered tissues, only a limited number of TEMPs are approved and commercialized for clinical uses (Table 1). This may be attributed to the fact that engineered tissues have high risks, more uncertainties in safety, efficacy and very expensive for commercialization. 8

Table 1.

List of approved tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs) commercialized in various countries.

| Product name | Description | Intended application | Year of commercialization | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omnigraft™ | Bilayer graft comprising upper silicone layer and lower collagen and chondroitin layer for chronic diabetic foot ulcers | Skin1,3,9,10 | 2016 | US (United States) |

| ReNovaCell™ | Skin autologous (epithelial cell) harvesting device as skin graft for vitiligo | 2016 | Europe | |

| Hyalograft 3D™ | Cultured autologous (skin fibroblast) on hyaluronic derivative scaffold for diabetic foot ulcer | 2007 | South Korea | |

| Dermagraft® | Cultured neonatal dermal fibroblast on bioresorbable scaffolds for foot ulcer treatment | 2001 | US | |

| Ossron™ | Autologous (bone marrow stem) implantation-based cell therapy for new bone formation | Bone 1 | 2009 2017 |

South Korea, India |

| INFUSE® bone graft | Recombinant human bone morphometric protein—2 on an absorbable collagen sponge for bone grafting (spine and orthopedic) | 2015 | US | |

| MACI® | Cultured autologous cell source (chondrocytes) on porcine collagen scaffold for treating damaged cartilage tissue | Cartilage1,11,12 | 2016 | US |

| Ortho-ACI™ | Autologous chondrocytes seeded with the scaffold for cartilage defect | 2017 | Australia | |

| Spherox | Human autologous (chondrocyte) spheroids for cartilage defect in adults | 2007 2017 |

Germany Europe |

|

| JACC® | Cultured autologous (chondrocytes) cells on collagen for cartilage defect | 2012 | Japan | |

| Novocart 3D | Autologous chondrocytes on 3D collagen chondroitin sulfate scaffold for cartilage defect | 2003 | EU | |

| CardioCel® | Acellular collagen matrix-based scaffold for cardiovascular treatment | Heart1,13 | 2013 2014 2014 2015 |

Europe US Canada Singapore |

| HeartSheet® | Autologous skeletal myoblast derived cellular sheets for ischemic heart disease | 2015 | Japan | |

| Avance® nerve graft | Decellularized ECM based 3D scaffold (allograft) for bridging nerve gap | Nerve 14 | 2015 | US |

| Neurotube® | Polyglycolic acid (PGA) based mesh tube for small pheripheral nerve lesions | 1999 | US |

TEMPs are the latest therapeutics that involve one or more complex manufacturing processes, varied constituents and different characteristic features, which demands unique standards and regulations for approval processes. 15 Global regulatory agencies evaluate the quality, safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of TEMPs for healthcare applications and regulate through various steps involved from commercialization to clinical practice.8,16 Tissue engineered medical products are regulated based on exclusively framed legislations in different countries. These legislations have the same set of objectives and rules but follow different regulatory terms/approval processes for commercialization. 15

TEMPs submitted under clinical transformation approval need to be manufactured in Good Manufacturing Facilities (GMP) setup using clinical-grade raw materials with defined Quality Attributes (QAs) and also need to be tested clinically with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidance. 17 Regulatory authorities of medicinal product approval generally focus on the criteria mentioned above and more specifically, on its benefits and risk involvement. 8

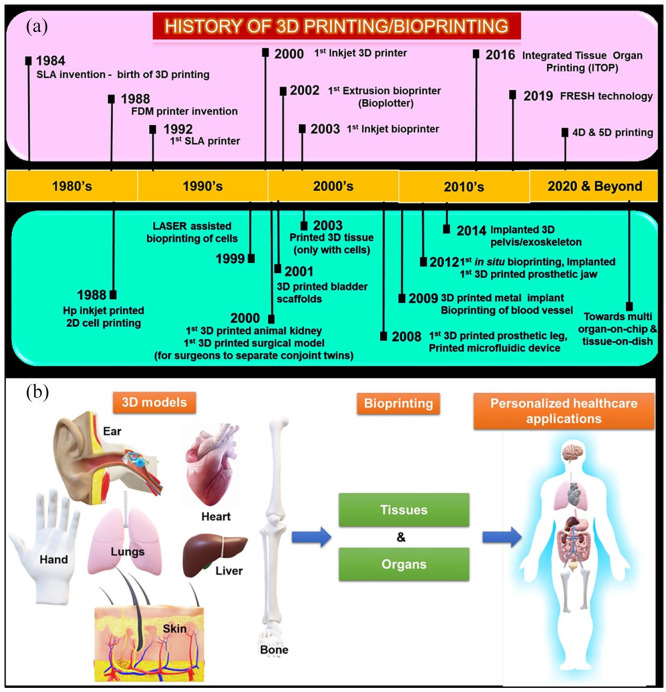

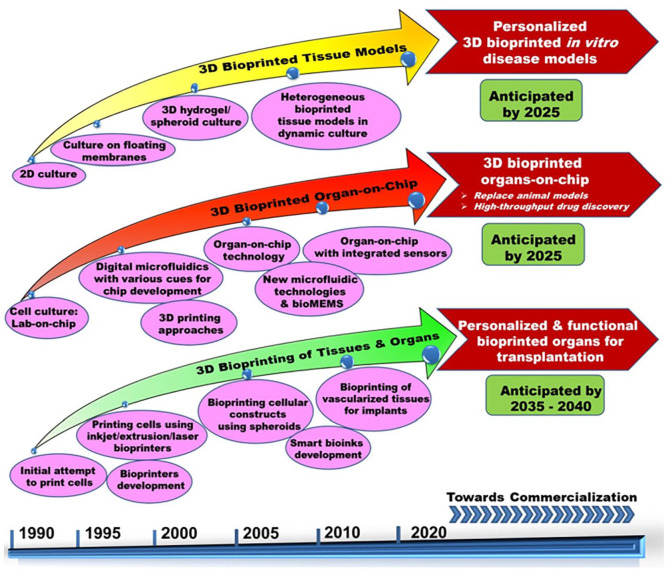

In the current decade, TEMPs fabricated through conventional tissue engineering approaches have a wide range of potential applications, such as congenital heart disease (CHD), heart valve replacement, bone fracture healing, severe burn injuries, cartilage defect, acute/chronic liver problems, etc., are now considered as a safer and efficient clinical solution. 4 Figure 1 shows the classification of ATMPs with emphasis on TEMPs, which falls under the main scope of this review. Further, bottom-up and reverse engineering approaches for fabricating patient-specific three-dimensional cellular/biomaterial scaffold with autologous cells (stem cells/other cells) using 3D bioprinting technique has become a better strategy in fabricating organs with biomimetic geometries and other physiological features of native tissues without any immune complications.15,16,18–20 3D printing has greatly evolved as an efficient technology especially for various applications in regenerative medicine. The progress and applications of 3D printing and bioprinting in regenerative medicine were broadly represented in Figure 2(a). Hence, computerized fabrication of multi-functional human 3D organs could facilitate the ease of organ transplantation and 3D tissue/organ model fabrication for pre-clinical drug/biological testing in the future (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of components and classification of ATMPs and their applications.

Figure 2.

(a) Chronological history of 3D printing/bioprinting in potential biomedical applications, (b) imagined future of 3D bioprinting—3D models obtained through CT or MRI images and computationally redesigned according to the personalized requirements.

From the above perspectives, this review mainly focuses on all the legislations, regulations, guidelines and standards followed worldwide for clinical trial approval and commercialization of the tissue engineered products. Further, the current tissue fabrication process with the advancement of additive manufacturing approaches for engineering personalized 3D printed tissues, components & types of 3D bioprinting, and the potential of bioprinting technology to fabricate tissues/organs for transplantation applications are also discussed. Additionally, the characteristics of bioprinted constructs, their applications and how they stand in comparison with tissue engineered medical products from an ethical and regulatory standpoint are elaborated. Further insights into the regulatory aspects of tissue engineered and bioprinted organs/tissues that greatly hamper the widespread clinical translations are discussed. Additionally, the ethical issues revolving around tissue engineered and bioprinted products and challenges in commercial success are also discussed. Finally, future perspectives of tissue engineered constructs are discussed and compared with the projected future of 3D bioprinting in regenerative medicine applications.

Tissue engineered medical products (TEMPS)

Tissue engineering (TE) is an interdisciplinary field that employs the principles of life sciences and engineering to restore and regenerate the physiological activity of damaged tissues or organs. This has led to the rapid development of tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs) using conventional tissue engineering strategies for diagnostic and therapeutic applications in various tissues such as skin, cartilage, bone, blood vessels, heart valves, etc., using components such as cells, scaffolds, biomolecules, processed tissues and their derivatives. 21 Notably, there are several TEMPs for cartilage defects and skin substituents which are currently in phase II and III clinical trial stages and so far provided the confirmations on therapeutic value, regenerative activity, safety and long-term biological effects.22,23 Moreover, the increase in clinical demands for organ transplantation, specifically for aging populations has propelled the exponential need for TEMPs on a larger scale and at affordable prices. However, limitations in conventional fabrication techniques such as lack of three-dimensional architecture, cellular positioning at the desired locations, variable cellular density, template requirement, difficulty in complex shape fabrication suggest the usage of advanced fabrication techniques to engineer tissues or organs for transplantation applications.24,25

An additive manufacturing approach: 3D printed TEMPS

3D printing has now gained huge attention from many users of different fields due to the layer-by-layer deposition, feasibility in fabricating complex models, ease of operation, low cost and multi-material deposition. 26 Various 3D printing techniques have been employed to develop patient-specific scaffolds and tissues using polymers such as polylactic acid (PLA), titanium, ceramics, polycaprolactone (PCL), polyurethane, etc. and most of them are evaluated for durability and functionality in both in vitro and in vivo studies for tissues such as bone, heart valves, skin, intestines, etc. 27 Currently in clinical surgery, 3D printing technology plays a major role by providing different technical and visual or physical support in the form of pre-operative surgical guides (cutting/drilling/planning), surgical tools, custom specific implants and prostheses. 28 3D printing offers a wide range of materials selection approach to create 3D structures as support or major implant for spinal surgery, maxillofacial, cranial, dental, orthopedic surgery, etc. Undoubtedly, for all these surgical approaches, medical surgeons collaborate with additive manufacturing based medical device companies or bioengineers to assist in the design and 3D printing for specific requirements. Additionally, 3D planning software makes patient-specific virtual surgery model to provide the clear-cutting plane and drilling trajectories to limit damages for nerves and blood vessels and improves positioning accuracy to place the implant. 29 Subsequently, the printing of different sized models can help to overcome the limitation of using cadaver-based surgical planning where specificity and availability are a major issue. 30

In a recent study of tissue regeneration to mimic native tissue structure, 3D printed bone graft made from PCL impregnated chitosan loaded with rabbit bone marrow stem cells showed improved differentiation activity and increased expression of osteogenic specific genes such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP), collagen type I (COL1), osteocalcin (OCN), and Runt-related transcription factor (RUNX2) after 14 days in vitro. This graft was also subcutaneously implanted in nude mice and observed that the 3D printed scaffold exhibited stronger osteogenesis and bone-matrix formation after 3 weeks of surgery. 31 Similarly, Zhang et al. have developed 3D printed navigational template using Computer Aided Design (CAD) software to facilitate the localization of small peripheral lung nodules and reduces the radiation exposure for lung cancer patients (ID: NCT02952261). The results of about 200 patients demonstrated that the personalized 3D printed template guided percutaneous localization was achieved with better accuracy and omits computed tomographic (CT) analysis during treatment. 32

3D bioprinting of tissues and organs

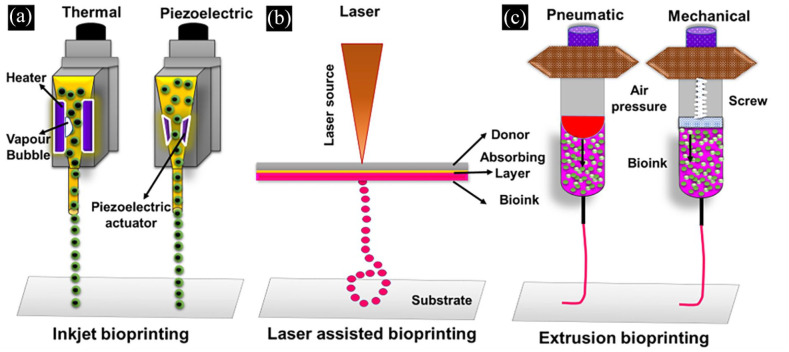

3D bioprinting technique is a 3D tissue fabrication technique where the cells are integrated into a cross-linkable hydrogel matrix called bioink to create 3D tissue equivalent constructs in the desired pattern.33,34 3D bioprinting requires essential components such as 3D imaging, CAD/CAM software, bioink, and bioprinter to carry out the fabrication process. Bioink is a combination of cells, polymers (biomaterials) and signaling molecules like growth factors with adequate viscoelastic and cell supportive functionalities that are suitable for the printing of tissues and organs in a bioprinter platform. 35 Further, the development of novel biomaterials or chemical modification of existing materials helps to customize bioinks for tissue-specific applications. Moreover, bioinks are deposited in a layer-by-layer manner at desired locations to enable the fabrication of vascularized 3D structures for tissue or organ regeneration applications. Bioink made of fibrous proteins such as collagen and fibrin contains more than 90% water, allowing them to create cell supportive and biocompatible tissue constructs. 36 Natural polymers such as collagen, Matrigel, gelatin, alginate, agarose, methylcellulose, fibrinogen and synthetic polymers such as pluronics, carbopol, nanoclay, hydroxyapatite and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) have been used as bioinks for the fabrication of various tissues like cardiac patches, bone, cartilage, and cornea. 37 Bioprinters capable of achieving ideal print speed, human-scale resolution, and also equipped to operate multi-material print heads could be beneficial in the fabrication of patient-specific tissues or organs. Bioprinting is divided into three types based on the bioink dispensing mechanism such as inkjet bioprinting, laser-assisted bioprinting and extrusion-based bioprinting. Inkjet bioprinting requires less viscous bioinks to dispense through micron-sized nozzles either by thermal or piezoelectric stimulus (Figure 3). 38 Laser-assisted bioprinting methods employ focusing the laser pulse on the metal-coated plate with low—medium viscosity bioinks to create 3D tissues (Figure 3). 39 These two printing systems have good printing resolution (20–40 µm) and cell viability (>90%). However, these methods are not widely preferred for fabricating human scale 3D tissues due to the difficulties in layer-by-layer stacking ability beyond a particular build volume. Extrusion bioprinters can dispense a variety of bioinks with a wide range of viscosities either through pneumatic or mechanical screw-based mechanisms (Figure 3). In recent years researchers have successfully fabricated various 3D tissues and organ models as a proof-of-concept using extrusion bioprinting. 40

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of different types of bioprinting. (a) Inkjet bioprinting, (b) laser-assisted bioprinting and (c) extrusion bioprinting.

Further, the features and limitations of these various bioprinting techniques such as inkjet, extrusion and laser-assisted bioprinting methods are briefly tabulated in Table 2. Printing of multiple cell types with variable cell densities (1 × 106 cells/mL to 1 × 108 cells/mL) at desired locations made 3D bioprinting one of the most advanced techniques for tissue or organ fabrication. 41 A comprehensive literature review of 3D tissues/organs fabricated using different bioprinting strategies for tissue regeneration application has been tabulated in Table 3.

Table 2.

Comparison of different techniques utilized in 3D bioprinting of tissues.

| Inkjet bioprinting | Laser-assisted bioprinting | Extrusion bioprinting | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contact | Non-contact | Non-contact | Contact |

| Dispensing form | Droplets | Droplets/continuous deposition | Filament |

| Dispensing mechanism | Thermal and piezoelectric | Laser | Pneumatic or mechanical |

| Printing speed | 1–10,000 droplets/s | 1–2000 mm/s | 0.1–150 mm/s |

| Viscosity | <10 mPa s | 1–300 mPa s | 30–1 × 106 mPa s |

| Resolution | 20–100 µm | 40–100 µm | 40–1200 µm |

| Materials used as bioinks | Alginate, gelatin, collagen type I, fibrin, polyethylene glycol (PEG) and gelatin methacrylate, etc. | Alginate, collagen type 1, gelatin, fibrin, etc. | Alginate, gelatin, gellan gum, guar gum, methylcellulose, collagen type 1, matrigel, fibrinogen, collagen methacrylate, gelatin methacrylate, elastin, polycaprolactone, polyethylene glycol, polyvinyl alcohol, polyvinyl acetate, etc. |

| Cell viability | ⩾85% | ⩾90% | 60%–90% |

| Fabrication level | Cells and tissues | Cells and tissues | Cells, tissues and organs |

| Printed tissues | Cardiac, liver, muscle, and bladder | Bone, cardiac, skin, cornea and nerve, etc. | Cardiac, pancreas, bone, skin, intestine, liver, kidney, and nerve, etc. |

| Advantages | Fast and cost-effective | Cytocompatibility, single-cell and multiple cell types printing | Printing of viscous materials, the printing of multiple cell types, and ease of 3D structures fabrication |

| Disadvantages | Clogging, non-uniformity in droplet size and difficulty to dispense viscous materials | Low efficient to form 3D structures, unable to dispense viscous materials and affordability | Low resolution, needle clogging and shear-induced cell death |

| References | Derakhshanfar et al. 42 and Ding et al. 43 | Koch et al. 44 and Guillotin et al. 45 | Lee et al. 46 and Gaetani et al. 47 |

Table 3.

Various types of tissue/organ constructs fabricated using 3D bioprinting methods.

| Tissues/organs | Bioink | Printing method/printer type | Cell’s type | Cell viability | Significant observations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve | Alginate, RGD—alginate, hyaluronic acid (HA), fibrin | Extrusion bioprinting (3D bio-plotter, EnvisionTEC) | Schwann cells from the sciatic nerve | ⩾89% | Schwann cell incorporated constructs showed good viability, elongation and directional growth of neurites in the longitudinal axis of strands and supported peripheral nerve regeneration after injury | Ning et al. 48 |

| Nerve | Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) | Digital light processing (DLP)-printer | Schwann cells (S16) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) | – | Nanoparticles-in-hydrogel nerve conduit that releases drug to facilitate peripheral nerve regeneration via Hippo pathway | Tao et al. 49 |

| Intestine | Collagen type-I | Vertically moved 3D printing | Caco-2 cells | 90% | Cell laden collagen/SIS villi showed significant cell proliferation, glucose uptake, tight-junction proteins and permeability coefficient | Kim and Kim 50 |

| Skeletal muscle | Fibrinogen, gelatin, HA, glycerol, polycapro-lactone (PCL) | Extrusion bioprinting (3D ITOP) | Human muscle progenitor cell (hMPC) | 90% | Bioprinted skeletal muscle tissue exhibited organized multi-layered muscle bundles with aligned myofiber-like structures showed 82% of functional recovery in a rodent model 8 weeks of post-implantation | Kim et al. 51 |

| Skin | Collagen | Extrusion bioprinting (integrated composite tissue/organ building system (ICBS)) | Human primary dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) and epidermal keratinocytes (HEKs) | The hybrid 3D cell printing system has extrusion and inkjet modules. Printed structures showed dermis and stratified epidermis layers after 14 days in vitro | Kim et al. 52 | |

| Bone | Collagen and bioceramic (β-tricalcium phosphate) | Extrusion bioprinting (3-axis printing system) | Pre-osteoblast cells (MC3T3-E1) and human adipose stem cells (hASC) | ⩾92% | The hASC-laden β-TCP composite structure showed significant osteogenic gene expression levels | Kim and Kim 53 |

| Bone | Endothelial cell growth medium | Laser-assisted bioprinting | Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) | – | In situ printing of HUVECs improved vascularization and bone regeneration of critical sized bone defects in mice | Kérourédan et al. 54 |

| Cartilage | Nanofibrillated cellulose | Extrusion bioprinting (INKREDIBLE 3D Bioprinter) | Human chondrocytes and human MSC | – | Printed constructs displayed 17.2% surface area covered with proliferating chondrocytes after 60 days of culture in vitro | Apelgren et al. 55 |

| Liver | Lung derived human extracellular matrix (hECM), gelatin and sodium alginate | Extrusion bioprinting (INKREDIBLE+) | Human bipotent hepatic progenitor cells and human epithelial lung carcinoma cells | – | Alginate/gelatin bioink with hECM enhances cell viability and liver-specific metabolic activities | Hiller et al. 56 |

| Cardiac | GelMA, CdECM | Extrusion bioprinting (EnvisionTEC 3D-bioplotter developer series) | Neonatal human cardiac progenitor cells | 75% | Printed GelMA patch with dECM have shown better proliferation, differentiation and angiogenic potential | Bejleri et al. 57 |

| Cardiac | Alginate Geltrex, and fibrin, HA | Laser-assisted bioprinting | hiPSC and iPSC—cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CM) | 82% | Laser printing does not affect the pluripotency, differentiation and proliferation ability of iPSC | Chichkov et al. 58 |

| Cornea | Collagen type 1, hyaluronic acid, laminin | Laser-assisted bioprinting | Human embryonic stem cell-derived limbal epithelial stem cells and human adipose-derived stem cells (hASC) | – | Successfully used laser bioprinting for corneal applications using human stem cells and showed layered 3D bioprinted tissues mimicking the structure of native corneal tissues | Sorkio et al. 59 |

| Cornea | Gelatin, alginate and type 1 collagen | Extrusion bioprinting | Human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs) | ⩾94% | The bioprinted cells showed good cell proliferation and expression of cytokeratin 3 (CK3) with the developed bioink of collagen, gelatin and alginate | Wu et al. 60 |

| Nose | Poly(ε-caprolactone) and gelatin | Extrusion bioprinting | hiPSC-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) | 86% | This double gelation mechanism and developed constructs showed good layer stacking ability and it was able to print nose as proof of concept | Hsieh and Hsu 61 |

| Blood vessels | GelMA and alginate | Extrusion bioprinting (Novogen MMX bioprinter) | HUVECs and human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) | ⩾80% | GelMA/alginate blended bioink exhibited good biological characteristics that supported the spreading and proliferation of encapsulated endothelial and stem cells | Jia et al. 62 |

| Blood vessels | Agarose and collagen type 1 | Microvalve-based (drop-on-demand bioprinting) | Human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) and HUVECs | – | Agarose/collagen hydrogel blend can be 3D printed and printed constructs exhibit cell-induced vascularization capability | Kreimendahl et al. 63 |

Regulatory roles and responsibilities of approving authorities

The main goal of regulatory agencies is to produce laws and regulations by following different regulatory frameworks to allow safer medicinal products for clinical trials and marketing purposes. Globally tissue-based products (TEMPs) are identified differently based on the categorizing condition for the regulatory approval. Likewise, TEMPs have been considered as drugs in the EU, a medical device in Japan and biologic/combined products in the U.S through their regulations/directives and further their approval pathways are decided by assessing the quality, safety and efficacy through nonclinical and clinical studies.3,12,64 The regulatory agencies of different countries that deal with clinical trial approval and permission for commercialization are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

List of regulatory agencies authorized in various countries for medicinal product regulation.

| Regulatory agency | Country |

|---|---|

| FDA’s (Food and Drug Administration)—established Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) for medical device regulation, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and Center for Drug Evaluation and Research for drug regulation | USA |

| Pharmaceuticals and Medical Device Agency (PMDA) and Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) | Japan |

| European Medicines Agency (EMA) | Europe |

| Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Central Drug Standards Control Organization, Indian Council of Medical Research | India |

| Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation | Russia |

| State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA) | China |

| Department of Health, Health Protection Agency, Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency | United Kingdom |

| Ministry of Health, National Institute of Pharmacy and Medicines, National Authority of Medicines and Health Products | Portugal |

| Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finish Medicines Agency | Finland |

| Korean Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) | South Korea |

Identically, Gene and Cell-based Therapies (GCTs) regulatory frameworks are outlined to assess product characteristics, evidentiary and non-evidentiary reasons for approval and post-marketing risk management studies. 8 It is identified that clinical translation of products is approved based on confirmed evidential benefit results for US and EU applications while regulations of Japan follow non-confirmed beneficial results. US, EU and Japan regulatory agencies are now approving Gene and Cell-based Therapies (GCTs) with scientific uncertainties and safety risks to allow the clinical transformation based on medical needs. 8 Oftentimes, approval processes for new products are based on the standards available on the technical details of pre-existing relevant products.

PROVENGE was the first commercialized cell therapy treatment for prostate cancer treatment in the United States and Transcyte for third degree skin replacement graft was the first FDA approved tissue graft in 1997. 12 Activskin, a skin graft was the first approved TEMP in China by 2013. 15 In 2001, the first cell therapy and tissue engineered product (chondrocyte-based product) was successfully commercialized in South Korea. Relatively, South Korea has more number of cell therapies in clinical practice as on 2018 status. 1 Totally 10 ATMPs were approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the Europe Union and likewise, the first commercialized tissue engineered product in Europe is ChondroCelect (for treating cartilage defects) in 2009, but this product was discontinued in 2016 due to commercial reason from its marketing authorization TiGenix NV. 12 As discussed earlier, in comparison with the last decade, more tissue-based therapies are approved by the authorities in consideration to produce these high therapeutically efficient TEMPs for the unmet medical needs. 10 As a result, several products for skin, cartilage, bone, heart, neural and several other complex organs have been commercialized in recent times.

Current regulations for TEMPs

Recently updated tissue engineered product regulations, approval requirements and rules enforced so far in U.S, India and European Union for the currently available TEMPs are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of current regulations followed by U.S., India and European Union for approval of clinical trials and commercialization of tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs).

| Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—US 65 | Central Drug Standards Control Organization (CDSCO)—India 66 | European Medicines Agency (EMA)—EU 67 | ||||

| Legislations related to the tissue engineered products commercialization for clinical practice in humans | FDA tired and risk based regulatory criteria for human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based product (HCT/P) are followed by Centre for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) | Import, manufacture, distribution and sale of drug and cosmetics in India tissue engineered products are also regulated by this act in consideration as therapeutic drugs | Advance therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) including gene, somatic therapies and tissue engineered product-based therapies and treatment enforced by committee for advanced therapies (CAT) and EU marketing authorization by regulating it as biological products | |||

| Regulated under | Objective | Regulated under | Objective | Regulated under | Objective | |

| 21 CFR part 1271 and section 361 of the public health service act (PHS Act) (42 U.S.C. 264) (regulation for HCT/Ps found under criteria mentioned in 1271.10(a)) | Establish the product requirements, details regarding registration, listing details, donor eligibility, good tissue practice (GTP), marketing details and steps/procedures to prevent the spread of communicable disease to patients No need of premarket approval |

Drug and cosmetic act 1940 and Rules 1945 (Amendment, 2016) | Regulation of new drug/cosmetics, assist its manufacture, import and marketing in India with high standards and assured safety for human health care application through licensing. It also regulates Ayurvedic, siddha and Unani drug manufacture and import | REGULATION (EC) No C(2017) 7694 | To regulate manufactured ATMP for clinical trials and exploring new possibilities of diagnosis and treatment in evaluation of its quality, safety and efficacy in order to provide approval for marketing in EU areas | |

| Section 351 of the PHS Act (42 U.S.C. 262) and/or federal food, drug, and cosmetic act (FD&C Act) (HCTPs regulation as other drugs, devices, and/or biological products) | Establish product requirements, details regarding biologics license (with respect to the product risk & safety analysis), clinical evaluation, post-market studies, labeling and marketing | |||||

| Final rule | Scope | Rule (schedule Y) | Scope | Regulations/directive | Scope | |

| Rules to be followed further | 66 FR 5447, January 19, 2001 69 FR 3823, January 27, 2004 | Registration and listing requirements and procedures | Rule 122 A | Application of permission to import new drug (licensing authority approval) | Article 11 of directive 2001/83/EC | Product characteristics and technical requirements to demonstrated product safety, quality and efficacy |

| 69 FR 29786, May 25, 2004 70 FR 29949, May 25, 2005 (Revised) | Cell source donor eligibility details and criteria (screening and testing mandatories) | Rule 122 DA | Requirement of permission from DCG(I) to conduct clinical trial for new drug/investigational new drug | Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 | Centralized authorization procedure—scientific valuation of safety, efficacy and quality | |

| Rule 122 DAB | Provision of examining serious adverse event (SAE) of death/injury and compensation payment details and debarment in case of failure | Directive 2004/23/EC | Comprises standards of quality and safety for the donation, procurement, testing, processing, preservation, storage and distribution of human tissues and cells | |||

| 69 FR 68612, November 24, 2004 | Includes the establishment, inspection of the product GCTP | Rule 122 DAC | Mandatory requirement of comprising good clinical practice (GCP) guidelines and specified rules in schedule Y of drug and cosmetics rules Provision of debarment of applicant in case of non-compliance |

Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 and directive 2001/20/EC | Comprises principle and guidelines for clinical trials and good manufacturing practice applicable to investigational medicinal products | |

| Rule 122 DD | Registration of ethical committee to safety, rights and well beings of human subjects under clinical trial study | Directive 2005/28/EC directive 2003/94/EC | Good clinical practice good manufacturing practice | |||

US based regulations

Unites States (US) authorized Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is a regulatory agency, which enforces Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), Kefauver-Harris Amendments, Medical Device Amendments and Public Health Service Act (PHS) for rules and conditions to evaluate product safety and efficacy in the United States of America (USA) medical care. 68 In this current decade, to utilize the safer health care innovations with an involvement to technically advance innovative medicinal therapy, several expedited approval pathways, alternative pathways with exemptions and special situation based decisions have been structured and enacted into legislations for further approval at a short period of time. 69 Recently FDA guidance expedited program includes Fast Track designation and Breakthrough Therapy designation were created through regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation program by 21st Century Cures Act for the sponsors of regenerative medicine products. 12

The regulatory criteria for human cells, tissues, and cellular & tissue-based products (HCT/P) issued by the FDA of the US are followed by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) under section 361 of the Public Health Service Act (PHS) provided in 21 CFR (Code of federal regulations) Parts 1270 and 1271 regulations. 3 Additionally, for some HCT/Ps not found in the mentioned criteria of 1271.10(a), it could be regulated as drugs, devices or biologics under section 351 of the Public Health Service Act (PHS) and Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C 23Act). 70 Due to the interdisciplinary landscape, HCT/Ps products with some exemptions such as cryopreserved femoral vein for AV shunt, cultured cells on biomaterial/decellularized scaffolds are regulated as a medical device with tissues or combination products through Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). 71 These regulations include HCT/P criteria for minimal manipulation (possibilities of processing method to induce alteration characteristics of the cells or tissue to replace/restore the function), homologous usage (without the combination of other articles which could give rise to new clinical application), its ability of with or without systemic effect having a dependency on cells metabolic activity. 70 Moreover, this can also regulate the usage of only FDA-registered resource materials for medical application. Further, it also states that manufacturers of HCT/P should register and list the product for approval from the authorities for the license, permission of preclinical, clinical data approval evaluation (Table 6). To facilitate updating, electronic submission is also possible using electronic HCT/P establishment registration (eHCTERS) system with all the submission of requirements.

Table 6.

Regulations and process details of FDA based Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER)72,73.

| FDA approval process | Functions |

|---|---|

| Investigational new drug (IND) or device exemption (IDE) Process | Request FDA to grant permission to administer drug/medical products to humans |

| Expanded access to experimental biologics | Request access for the use of non-FDA approved medical products |

| Biologics license application (BLA) process | Request to obtain a license by a manufacturer or an applicant before marketing after submitting manufacturing methods, pre-clinical and clinical data for evaluating safety, quality and efficacy |

| Premarket notification (510 k) process | Submission to FDA to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of the product to market it |

| Premarket approval (PMA) process | Process of FDA to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the approached medical product (mostly Class III medical devices) |

FDA is also providing special protocol assessment (SPA) guidance by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) to help in study designs animal studies and clinical studies and trials. Under section 505(b)(5)(B) of the FD&C Act, under SPA, drug stability or animal efficacy protocols should apply for approval with study designs and statistical analysis. Submission of SPA request is a process that involves (i) Informing FDA of an upcoming request; (ii) Timing of a request for review process up to 45 days which includes documents submission and resubmission of additional required documents; (iii) The request format should contain the cover letter with bold block letters mentioning “REQUEST FOR SPECIAL PROTOCOL ASSESSMENT”; (iv) The SPA should submit to the appropriate CDER or CBER division, using standard or electronic submission. FDA will start analyzing the submissions to see whether it is suitable under SPA and communicate decision by mail within 45 days of the review timeline. 74

EU based regulations

In the EU (European Union), classification of tissue engineered products are clearly explained and regulated well and Regulation (EC)No 1394/2007 was designed and amended on December 30, 2008 for Advanced therapy and medicinal products (ATMP including cell therapy, gene therapy and tissue engineered medicinal products) for evaluation of product quality, efficacy and safety.17,75 Product description, scientific and technical requirements for improved quality, safety and efficacy are followed through Directive 2001/83/EC, which states that cells are considered to be engineered if it is manipulated including cutting, shaping, centrifugation, sterilization procedures, cryopreservation, lyophilization, etc. Likewise, Directive 2004/23/EC and Directive 2001/20/EC, Regulation (EC) No 726/2004, Directive 2005/28/EC, 2003/94/EC are followed by European Medicines Agency (EMA) for marketing authorization requirements and regulation procedure. 76 These directives state that the applicants producing product specifications should provide the product details clearly including, name, composition, quantitative & qualitative details, clinical particulars, its interaction with other substance & molecule, precautions steps if any, usage during pregnancy & lactation details, pharmacological, pharmacodynamics & pharmacokinetic properties, pre-clinical safety data, shelf life, storage condition and its procedure, marketing details, etc. In addition, packaging should mention the marketing authorization, manufacture batch number 2004/23/EC, expiry date, method of use, special warnings, etc. 76 Further, all the clinical data analysis, proper GMP and GLP activities are expected. Particularly, conditional approval has been described by the regulation (EC)N 507/2006 with some difference in the regulatory framework of EU. 17 EU regulatory implements adaptive approach regulatory pathways mostly for the cellular and tissue-based products. Besides, other pathways are also there such as standard pathway, conditional pathway, adaptive licensing and PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) are framed to regulate products of different categories.8,12

India based regulations

In India, Drug and Cosmetic Act 1940 and Rules 1945 were enacted to regulate drug approval by Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO). 66 Especially Cell Biology Based Therapeutic Drug Evaluation Committee (CBBTDEC) by CDSCO was formed in 2010 for cell therapy related clinical approval. 77 Additionally in India, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) involve in providing guidelines for conducting biomedical and clinical research activities for clinical regulation. Briefly, the Drugs & Cosmetics Act 1940 was legislated by Indian law in concern with the importing, manufacturing and marketing drugs and cosmetics commercially to all over India with assured safety and high quality in their role. In accordance with this act, CDSCO has established Drugs Technical Advisory Board (DTAB) and Drugs Consultative Committee (DCC) with the main objective to maintain and follow common standards in commercializing, clinically practicing the new drug/existing drug for human disease treatment. Tissue engineered products including stem cell-based products are categorized as a drug in evaluating its clinical practice application, regulation and for its clinical practice by CBBTDEC. Importantly, requirements governing the clinical trial approvals, license and permissions are covered under the Schedule Y, Rules 122 A, 122 B, 122 DA, 122 DB, 122 DAC, 122 DD. 66 Product safety and efficacy is evaluated through the Chemistry, Manufacturing and Control (CMC) data, pre-clinical data and clinical trial data (phase I, phase II, and phase III). Moreover, ICMR had launched ethical guidelines for biomedical research on a human subject in 2000 (revised in 2006 and 2017) and good clinical laboratory practice guidelines (2008) for the conduct of clinical trials in India. 77 Good clinical practice (GCP) guidelines provide standards for obtaining quality data by designing reproducible clinical work protocol in the research laboratories to obtain the same quality, reliable results, meanwhile saving money, time and complexity involved in experiments.

Regulations followed by other countries

Likewise in Japan, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) regulates the tissue engineered products to clinical practice through the Safety and Regenerative Medicine Act (RM Act) and Pharmaceuticals, Medical Devices and Other Therapeutic Products Act (PMD Act). 78 In China, Tissue Engineered Medical Products (TEMP) are regulated through different categories as class III medical device based on the classification mentioned in the Medical Devices Classification Rule (MDCR, CFDA Order No. 15) by China Food and Drug Administration(CFDA). 15 In China, the regulatory approach is mainly focused on the final product utility in treating the medical need and it does not mainly depend on the raw material and processing method.

A cohort study conducted by Coppens on the approval of GCTs between 2008 and 2017 by US, EU and Japan regulatory concluded that Japan showed higher acceptance of GCT in consideration with uncertainties and safety risks followed by EU and US. In the majority of cases, unmet medical needs are considered for its regulatory approval by the EU and Japan clinical transformation regulatory system. While considering post-marketing characteristics, product safety, quality and risks are analyzed in Japan and EU, but in US safety is the main focus. 8 However, US and EU have many alternative pathways and regulations to facilitate the approval process relatively faster. Japan follows time limited approval pathways to overcome some of the already existing limitations. 64

Regulations for 3D printed/bioprinted TEMPs

3D printed (additive manufactured) products in medical applications are fabricated as whole device/part which could be utilized as prosthesis or an implant or other medical assistance devices. 73 In recent times, 3D printed prostheses for hip, knee, skull, jaw bone or joint implant, limb prostheses, orthopedic implants, heart valves, etc., are developed and currently under extensive clinical research. These 3D printed prostheses have the potential to create personalized implants of complex structures with precisely controlled material and structural properties within short time when compared to other implant fabrication methods.2,53,79,80 Further, additive manufactured metal implants have added advantage in controlling internal porous structures to promote biological fixation with long-term stability. Although 3D-printed implants (including metal implants) are devoid of cellular materials, they are also regulated as medical devices. 81 However, bioprinted TEMPs with complex cell source and bioink composition for regenerative medicinal application could be regulated either as biologics or drugs/medical devices based on the regulatory authorities. 82 3D bioprinted tissues fall between the categories of living materials & technology and hence do not fall directly into the existing categories of regulations. In order to bring this to light, experts have developed a concept called “bio-objects,” which means that all kinds of biotechnologies fall “in-between” the existing categories of living and non-living matter.83,84 These “bio-objects” do not fall into the standard regulatory frameworks which are based on the clinically well-established medicinal product categories. Consequently, these products require new regulations/laws for clinical trials and commercialization.

In the US, personalized 3D printed medical devices are regulated under the medical device category or with some custom device exemptions to evaluate their safety and efficacy through pre-market/post-market requirements. 85 However, generic medical devices are categorized into 16 special domains (based on their usage and risk) and each device is considered among one of the three regulatory classes based on its safety level and efficacy. These medical devices are classified through de novo classification—a risk-based classification for the regulations as mentioned in Table 7. Based on these categorical classifications, 510 k regulation is required for class I and II devices while for class III, premarket approval application (PMA) is required for the FDA approval process. All these classification systems are subject to common control requirements of Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and additional market approval as a design control model from regulatory agencies. 69

Table 7.

Classifications of medical devices (TEMPs) based on risk levels.

| US—medical device 86 | |||

| Class I—General control (with/without exemptions) | Class II—General control and specific control (with/without exemptions) | Class III—General control with premarket approval | |

| • Low risk For example, breast pump, stethoscope, etc. |

• Moderate risk device For example, catheter, bone plate, joint implant, etc. |

• Highest risk devices For example, Mechanical heart valve, implantable infusion pump, heart stent, hip prostheses, etc. |

|

| EU—medical device 87 | |||

| Class I | Class IIa | Class IIb | Class III |

| • Low risk • Noninvasive device For example, stethoscopes, electrodes (EEG/ECG), etc. |

• Low to medium risk Surgically invasive/noninvasive, active and nonhazardous to patient For example, infusion cannula, surgical swabs, needle for suturing, etc. |

• Medium to high risk • Invasive/noninvasive, active devices, implantable • (Has some hazardous effect) For example, catheters, peripheral vascular graft and stent, maxillofacial implants, etc. |

• High risk Supports human life in direct connection with health system For example, Neuro-endoscopes, cardiovascular catheter, biological heart valve, etc. |

The FDA has provided guidelines for the 3D printed materials under two different considerations such as Design and Manufacturing Considerations (device design/patient match design, software process, material, printing process & control, post-process and validation) and Device Testing Considerations (device description and measurements, material characterization and mechanical testing) to ensure product quality, efficacy and determination of classification for regulations. 88 Currently, 3D printed medical devices are regulated through premarket notification, New Drug Application (considering as new drug) and Biologics License Application (considering as biologics). 73 The FDA has so far approved the AXIOM 20 3D printer for manufacturing medical devices and one 3D printed drug named Spritam® tablets for epilepsy treatment. 89

On the other hand, EU follows legislation such as AIMDD 90/385/EE (Active Implantable Medical Device Directive), MDD 93/42/EEC (Medical Device Directive) and IVDMDD 98/79/EC (In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Device Directive) for 3D printed medical device products. Further, as per the standards mentioned in directive 93/42/EEC, medical devices are classified into four categories such as Class I (Noninvasive devices), Class IIa, Class IIb and Class III ranked from lowest to higher risk (Table 7). Higher rank classes require higher safety assessment levels and such classification levels are decided based on the consideration of patient contact duration, degree of invasiveness and place of the implantation/contact in human body part. These rules have been followed by effectively implementing as a set of 18 rules presented in Table 8. A titanium based (Ti-6Al-4V) 3D printed implant called iFuse-3D is clinically used as structural support for sacroiliac joint to promote bone growth. This implant has received market clearance under conventional medical devices regulations in both US and EU. Post-market evaluation of this implant has assessed patient safety and efficacy of the product similarly to a machined implant. The clinical outcomes had revealed that iFuse-3D reduced the pain related complaints, thereby avoided secondary corrective surgeries. In addition, this implant did not show any unanticipated clinical complaints after treatment and hence is efficient in creating patient-specific implants using 3D printing technology. 90 Likewise, Ackland et al. fabricated personalized 3D printed prosthetic temporomandibular joint (TMJ) for a 58-year female patient. This prosthetic was modeled using patient musculoskeletal modeling for assessing implant stress and strain, applied load, screw stress and other physiological loadings. Further, the modeled prosthetic was analyzed, fabricated and finally implanted into the patient to study its efficacy. It was observed that a normal jaw opening distance of 40.0 mm was achieved with less pain after 6 months of postoperative surgery. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of personalized 3D printed complex joint replacement prosthetics developed through several modeling and computational analysis. 91 Hyun Ho Han et al. have fabricated patient-specific, 3D printed biodegradable scaffolds using medical-grade polycaprolactone and implanted them in three patients with complex maxillary defects. This implant is registered as a medical device in South Korea (registration No. 14–1337) and manufactured according to Good Manufacturing Practice provisions (registration No. KTC-ABB-170177). In the follow-up period of 16 months, implanted scaffolds promoted neo-tissue ingrowth which was confirmed by CT images compared between pre and post-surgery images (2711 mm3) and Hounsfield unit values (preoperative - −76.269; after 6 and 16 months of implantation - +63.7825 and +73.0488). 92

Table 8.

EU directives and classification rules for medical devices as per annexure IX of directive 93/42/EEC 87 .

| Category | Rules | Indications | Medical device class category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive | Rule 1 | Do not touch patient/contact only skin | Class I |

| Rule 2 | Channeling or storing for eventual administration | Class I | |

| Class IIa (if it is used with blood or used along with active device of class IIa and higher classes) | |||

| Rule 3 | Modify biological or chemical composition of blood, body fluid, etc. for infusion | Class IIb | |

| Class IIa (only filtration, centrifugation, or gas exchange) | |||

| Rule 4 | In contact with injured skin | Class I | |

| Class IIa (intended to manage micro environment of skin) | |||

| Class IIb (intended for wounds which breach dermis and needs secondary intent for healing) | |||

| Invasive | Rule 5 | Invasive in body orifice or stoma (not surgically invasive) | Class I (transient use, sort term use only in oral cavity/ear canal/nasal cavity) |

| Class IIa (short term use, connected to active medical device in class IIa and higher device, long term use in oral cavity/ear canal/nasal cavity) | |||

| Class IIb (long term use) | |||

| Rule 6 | Surgically invasive Transient use |

Class I (reusable surgical instrument) | |

| Class IIb (supply energy/ionizing radiation, biological effect mainly/wholly absorbed, intended to administer medicine in a potentially hazardous manner) | |||

| Class III (to monitor/control/diagnose/correct defect in heart or central nervous system (CNS) by direct contact | |||

| Rule 7 | Surgically invasive Short term use |

Class IIb (supply energy/ionizing radiation, undergo chemical change in body or administer medicines) | |

| Class III (to monitor/control/diagnose/correct defect of heart or central nervous system (CNS) by direct contact) | |||

| Rule 8 | Surgically invasive Long term use and implantable device |

Class IIa (placed in teeth) | |

| Class III (in direct contact with heart or CNS, biological effect or mainly absorbed, undergo chemical change in body or administer medicine, breast implant, hip, knee and shoulder joint replacement | |||

| Active devices | Rule 9 | Active therapeutic devices intended to administer or exchange energy | Class IIa |

| Class IIb (if it is hazardous way, intended to control/monitor/influence directly the performance of class IIb active therapeutic devices) | |||

| Rule 10 | Active device for diagnosis, is intended to supply energy, to image in vivo distribution of radiopharmaceuticals or for direct diagnosis or monitoring of vital physiological process | Class IIa | |

| Class IIb (intended to monitor vital physiological parameters where variations could result in immediate danger, all devices emitting ionizing radiations and intended for diagnostic and therapeutic interventional radiology | |||

| Rule 11 | Active devices to administer or remove medicines and other substances to or from the body | Class IIa | |

| Class IIb (if it is in a potentially hazardous way) | |||

| Rule 12 | All other active devices | Class I | |

| Special rules | Rule 13 | Device incorporating integral medicinal substance liable to act in ancillary way on human body | Class III |

| Rule 14 | Device used for contraception or prevention of sexually transmitted diseases | Class IIb | |

| Class III (if implantable or long-term invasive) | |||

| Rule 15 | Specifically, to be used for disinfecting medical devices | Class IIa | |

| Class IIb (specifically to be used for disinfecting invasive devices, disinfecting, cleaning, rinsing or hydrating contact lenses) | |||

| Rule 16 | Devices intended for recording of X-ray diagnostic images | Class IIa | |

| Rule 17 | Device utilizing non-viable animal tissues or derivatives (not devices in contact with intact skin) | Class III | |

| Rule 18 | Blood bags | Class IIb |

Universal standards for tissue engineered products

Standards for TEMPs are established to ensure product characteristics and all associated analytical procedures to ensure common quality results worldwide with improved repeatability and reliability of the data. The International Organization of Standards (ISO) and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) International are the recognized organizations for presenting standardization of biomaterials and medical devices. 93 ASTM International is an organization that provides resources, technical expertise to develop universal standards and guidelines for a wide range of developing fields. It comprises several committees and subcommittees with respect to specific technical areas to frame the standards and guidelines including material characteristics, test methods, system, etc. Specifically for tissue engineered medical products, the F04 committee on “Medical and Surgical Materials and Devices” with other subcommittees named Division IV “Tissue-Engineered Medical Products (TEMPs)” was established in 1997 and the up to date standards published by these committees (Table 9). 94 Further, ASTM has established the F42 committee on “Additive Manufacturing Technologies” in 2009 with eight technical committees to formulate standards for 3D printed medical products. 89

Table 9.

List of published ASTM standards framed by committee F04 and sub-committee IV for TEMPs. 95

| ASTM subcommittee | Category | Published standards (ASTM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F04.41 | Classification and terminology for TEMPs | ASTM F2211-13 | Standard specification for general classification for tissue engineered medical products |

| ASTM F2312-11(2020) | Standard terminology relating to tissue engineered medical products | ||

| F3163-16 | Standard guide for classification of cellular and/or tissue-based products (CTPs) for skin wounds | ||

| F04.42 | Biomaterials and biomolecules for TEMPs | F2027-08(TG13 WK9442) | Standard guide for characterization and testing of raw or starting biomaterials for tissue engineered medical products |

| F2027-16 | Standard guide for characterization and testing of raw or starting materials for tissue-engineered medical products | ||

| F2064-17 | Standard guide for characterization and testing of alginates as starting materials intended for use in biomedical and tissue engineered medical product applications | ||

| F2103-18 | Standard guide for characterization and testing of chitosan salts as starting materials intended for use in biomedical and tissue-engineered medical product applications | ||

| F2131-02(2012) & WK67352 | Standard test method for in vitro biological activity of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) Using the W-20 mouse stromal cell line | ||

| F2150-19 | Standard guide for characterization and testing of biomaterial scaffolds used in regenerative medicine and tissue-engineered medical products | ||

| F2212-20, WK68915 and WK70847 | Standard guide for characterization of Type I collagen as starting material for surgical implants and substrates for tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs) | ||

| F2259-10(2012)e1 | Standard test method for determining the chemical composition and sequence in alginate by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy | ||

| F2260-18 | Standard test method for determining degree of deacetylation in chitosan salts by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy | ||

| F2347-15 | Standard guide for characterization and testing of hyaluronan as starting materials intended for use in biomedical and tissue engineered medical product applications | ||

| F2450-18 | Standard guide for assessing microstructure of polymeric scaffolds for use in tissue-engineered medical products | ||

| F2602-18 | Standard test method for determining the molar mass of chitosan and chitosan salts by size exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering detection (SEC-MALS) | ||

| F2603-06(2020) | Standard guide for interpreting images of polymeric tissue scaffolds | ||

| F2605-16 | Standard test method for determining the molar mass of sodium alginate by size exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering detection (SEC-MALS) | ||

| F2791-15 | Standard guide for assessment of surface texture of non-porous biomaterials in two dimensions | ||

| F2952-14 | Standard guide for determining the mean darcy permeability coefficient for a porous tissue scaffold | ||

| F3089-14 | Standard guide for characterization and standardization of polymerizable collagen-based products and associated collagen-cell interactions | ||

| F3142-16 | Standard guide for evaluation of in vitro release of biomolecules from biomaterials scaffolds for TEMPs | ||

| F3259-17 | Standard guide for micro-computed tomography of tissue engineered scaffolds | ||

| F3354-19 | Standard guide for evaluating extracellular matrix decellularization processes | ||

| F3510-21 | Standard guide for characterizing fiber-based constructs for tissue-engineered medical products | ||

| F04.43 | Cells and tissue engineered constructs for TEMPs | F2149-16 | Standard test method for automated analyses of cells—the electrical sensing zone method of enumerating and sizing single cell suspensions. document to be reviewed for possible updating of data evaluation section |

| F2315-18 | Standard guide for immobilization or encapsulation of living cells or tissue in alginate gels | ||

| F2664-19e1 | Standard guide for assessing the attachment of cells to biomaterial surfaces by physical methods | ||

| F2944-20 | Standard practice for automated colony forming unit (CFU) assays—image acquisition and analysis method for enumerating and characterizing cells and colonies in culture | ||

| F2997-13 | Standard practice for quantification of calcium deposits in osteogenic culture of progenitor cells using fluorescent image analysis | ||

| F3088-14 | Standard test method for use of a centrifugation method to quantify/study cell-material adhesive interactions | ||

| F3106-14 | Standard guide for in vitro osteoblast differentiation assays | ||

| F3206-17 | Standard guide for assessing medical device cytocompatibility with delivered cellular therapies | ||

| F3369-19e1 | Standard guide for assessing the skeletal myoblast phenotype | ||

| F3209-16 | Standard guide for autologous platelet-rich plasma for use in tissue engineering and cell therapy | ||

| F2739-19 | Standard guide for quantitating cell viability within biomaterial scaffolds | ||

| F04.44 | Assessments for TEMPs | F2451-05 | Standard guide for the assessment of implantable devices intended to repair or regenerate articular cartilage |

| F2529-13 | Standard guide for in vivo evaluation of osteoinductive potential for materials containing demineralized bone (DBM) | ||

| F2884-12 | Standard guide for pre-clinical in vivo evaluation of spinal fusion | ||

| F3207-17 | Standard guide for in vivo evaluation of rabbit lumbar intertransverse process spinal fusion model | ||

| F3223-17 | Standard guide for characterization and assessment of tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs) for knee meniscus surgical repair and/or reconstruction | ||

| F3224-17 | Standard test method for evaluating growth of engineered cartilage tissue using magnetic resonance imaging | ||

| F3225-17 | Standard guide for characterization and assessment of vascular graft tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs) | ||

| F3368-19 | Standard guide for cell potency assays for cell therapy and tissue engineered products | ||

| F2721-09(2014) | Standard guide for pre-clinical in vivo evaluation of critical size segmental bone defects | ||

| F04.45 | Safety | WK70143 (proposed) | Sampling methods of tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs) for sterility assurance |

Similarly, ISO comprises a Technical Committee (TC) and Sub Committee (SC) to provide standards and guidelines for different fields. In particular, for fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, technical committee 150 “Implants for surgery” with subcommittee SC7 “Tissue-engineered medical products,” which was established in 2001 covers TEMPs based on published standards (International organization of standards/Technical committee/Subcommittee ISO/TC 150/SC7) (Table 10). Other technical committees such as TC194 (Biological and clinical evaluation of medical devices), TC210 (Quality management and corresponding general aspects for medical devices), TC212 (Clinical laboratory testing and in vitro diagnostic test systems), TC261 (Additive manufacturing) and TC266 (Biomimetics) are established with several standards which are widely utilized for health care applications. 124 Periodically, each committee could establish the new standards or revised version of published standards for evaluation. For example, TC150 has published 165 standards and TC 194 has published 32 ISO standards in 2020. An informative list of ASTM and ISO standards followed by world regulatory authorities for commercializing medical products are tabulated (Table 11). These standards and updated protocols could help to establish a uniform approach and assessment procedure for validating medical products including tissue engineering products while ensuring high quality and more safety to humans. 115 This is imperative because cellular and acellular synthetic/natural constructs need specific standards for characterization and in vitro, in vivo and clinical trial analyses with respect to the raw material used. 114

Table 10.

List of published ISO standards of technical committee 194 and 150 for the regulation of medical device and tissue engineered products (TEMPs).

| TC/SC | Published standards | |

|---|---|---|

| TC 194/SC1 Tissue product safety (“ISO—ISO/TC 194/SC 1—tissue product safety) 96 |

ISO 13022:2012 | Medical products containing viable human cells—application of risk management and requirements for processing practices |

| ISO 22442-1:2015 | Medical devices utilizing animal tissues and their derivatives—part 1: application of risk management | |

| ISO 22442-2:2015 | Medical devices utilizing animal tissues and their derivatives—part 2: controls on sourcing, collection and handling | |

| ISO 22442-3:2007 | Medical devices utilizing animal tissues and their derivatives—part 3: validation of the elimination and/or inactivation of viruses and transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) agents | |

| TC 150/SC7 Tissue engineered medical products (TEMP) (“ISO—ISO/TC 150/SC 7—tissue-engineered medical products) 97 |

ISO 13019:2018 | Tissue-engineered medical products—quantification of sulfated glycosaminoglycans (sGAG) for evaluation of chondrogenesis |

| ISO/TR 16379:2014 | Tissue-engineered medical products—evaluation of anisotropic structure of articular cartilage using DT (diffusion tensor)—MR Imaging | |

| ISO 19090:2018 | Tissue-engineered medical products—bioactive ceramics—method to measure cell migration in porous materials | |

| ISO/CD TS 21560.2020 | General requirements of TEMPs | |

| ISO 7198:2016 | Cardiovascular implants and extracorporeal systems—vascular prosthesis—tubular vascular grafts and vascular patches | |

| TC168 prosthetics and orthotics (“ISO—ISO/TC 168—prosthetics and orthotics) 98 | ISO 13405-1:2015 | Prosthetics and orthotics—classification and description of prosthetic components—part 1: Classification of prosthetic components |

| ISO 13405-2:2015 | Prosthetics and orthotics—classification and description of prosthetic components—part 2: Description of lower limb prosthetic components | |

| ISO 13405-3:2015 | Prosthetics and orthotics—classification and description of prosthetic components—part 3: Description of upper limb prosthetic components | |

| ISO 21065:2017 | Prosthetics and orthotics—terms relating to the treatment and rehabilitation of persons having a lower limb amputation | |

| ISO 8549-1:2020 | Prosthetics and orthotics—vocabulary—part 1: general terms for external limb prostheses and external orthoses | |

| ISO 8549-2:2020 | Prosthetics and orthotics—vocabulary—part 2: terms relating to external limb prostheses and wearers of these prostheses | |

| ISO 8548-1:1989 | Prosthetics and orthotics—limb deficiencies—part 1: method of describing limb deficiencies present at birth | |

| ISO 8548-2:2020 | Prosthetics and orthotics—limb deficiencies—part 2: Method of describing lower limb amputation stumps | |

| ISO 8548-3:1993 | Prosthetics and orthotics—limb deficiencies—part 3: Method of describing upper limb amputation stumps | |

| ISO 8548-4:1998 | Prosthetics and orthotics—limb deficiencies—part 4: Description of causal conditions leading to amputation | |

| ISO 8548-5:2003 | Prosthetics and orthotics—limb deficiencies—part 5: Description of the clinical condition of the person who has had an amputation | |

| ISO 29783-1:2008 | Prosthetics and orthotics—vocabulary—part 1: normal gait | |

| ISO 29783-2:2015 | Prosthetics and orthotics—vocabulary—part 2: Prosthetic gait | |

| ISO 8549-3:2020 | Prosthetics and orthotics—vocabulary—part 3: terms relating to orthoses | |

| ISO 8549-4:2020 | Prosthetics and orthotics—vocabulary—part 4: terms relating to limb amputation | |

Table 11.

Established ISO & ASTM standards applied for global tissue engineered product regulation from basic pre-clinical research to clinical trial research.

| Published ISO standards | Ref | |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 14155:2020 | Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects—Good clinical practice | Bosiers et al. 99 |

| ISO 22442-1:2020 | Medical devices utilizing animal tissues and their derivatives—part 1: Application of risk management | ISO 100 |

| ISO 22442-2:2020 | Medical devices utilizing animal tissues and their derivatives—part 2: Controls on sourcing, collection and handling | ISO 101 |

| ISO 10993-1:2018 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 1: evaluation and testing within a risk management process | Parente 102 |

| ISO 10993-2:2006 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 2: animal welfare requirements | Singh et al. 103 |

| ISO 10993-3:2014 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 3: tests for genotoxicity, carcinogenicity and reproductive toxicity | De Moura and Van Houten 104 |

| ISO 10993-7:2008/AMD 1:2019 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 7: ethylene oxide sterilization residuals—amendment 1: applicability of allowable limits for neonates and infants | Gimeno et al. 105 |

| ISO 10993-9:2019 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 9: framework for identification and quantification of potential degradation products | Reeve and Baldrick 106 |

| ISO 10993-12:2012 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 12: sample preparation and reference materials | Coleman et al. 107 |

| ISO 10993-13:2010 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 13: identification and quantification of degradation products from polymeric medical devices | Deliversky et al. 108 |

| ISO 10993-14:2001 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 14: identification and quantification of degradation products from ceramics | Deliversky et al. 108 |

| ISO 10993-15:2019 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 15: identification and quantification of degradation products from metals and alloys | Horicsányi et al. 109 |

| ISO 10993-18:2020 | Biological evaluation of medical devices—part 18: chemical characterization of medical device materials within a risk management process | Jóźwicka et al. 110 |

| ISO 22196:2011 | Measurement of antibacterial activity on plastics and other non-porous surfaces | Qureshi et al. 111 |

| ISO13314:2011 | Mechanical testing of metals—ductility testing—compression test for porous and cellular metals | Zaharin et al. 112 |

| ISO 13485:2016 | Medical devices—quality management systems—requirements for regulatory purposes | Bhat et al. 89 |

| ISO 7198:1998 | Specific requirement for tubular prostheses for vascular functions | Aussel et al. 113 |

| ISO 21536:2007/AMD 1:2014 | Non-active surgical implants—joint replacement implants—specific requirements for knee-joint replacement implants—amendment 1 | Marchiori et al. 114 |

| ISO 14630:2012 | Non-active surgical implants—general requirements | |

| ISO 5840-1:2015 | Cardiovascular implants—cardiac valve prostheses—part 1: general requirements | Zhang et al. 115 |

| ISO 9001:2015 | Quality management systems—requirements | Bt Hj Idrus et al. 16 |

| ISO/IEC 17025:2017 | General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories | |

| ISO 13019:2018 | Tissue-engineered medical products—quantification of sulfated glycosaminoglycans (sGAG) for evaluation of chondrogenesis | ISO 116 |

| ISO/TR 16379:2014 | Tissue-engineered medical products—evaluation of anisotropic structure of articular cartilage using DT (Diffusion Tensor)-MR Imaging | Tensor 117 |

| ISO 19090:2018 | Tissue-engineered medical products—bioactive ceramics—method to measure cell migration in porous materials | ISO 118 |

| ISO/TS 21560:2020 | General requirements of tissue-engineered medical products | ISO 119 |

| Active ASTM standard | ||

| ASTM F2150-19 | Standard guide for characterization and testing of biomaterial scaffolds used in tissue-engineered medical products | Tesk 93 |

| ASTM F2211-13 | Standard classification for tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs) | Tesk 93 |

| ASTM F2312-11 | Standard terminology relating to tissue engineered medical products | Lee et al. 72 |

| ASTM F2739-19 | Standard guide for quantitating cell viability within biomaterial scaffolds | Oyama et al. 120 |

| ASTM F2315-18 | Standard guide for immobilization or encapsulation of living cells or tissue in alginate gels | Lee et al. 72 |

| ASTM F3142-16 | Standard guide for evaluation of in vitro release of biomolecules from biomaterials scaffolds for TEMPs | Garcia et al. 121 |

| ASTM F1635-16 | Standard test method for in vitro degradation testing of hydrolytically degradable polymer resins and fabricated forms for surgical implants | Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon 122 |

| ASTM F2027-1.6 | Standard guide for characterization and testing of raw or starting biomaterials for tissue-engineered medical products | Amato 123 |

| ASTM F2211-13 | Standard classification for tissue engineered medical products (TEMPs). | Tesk 93 |

| ASTM F2450-18 | Standard guide for assessing microstructure of polymeric scaffolds for use in tissue engineered medical products | Garcia et al. 121 |

| ASTM F2603-06(2012) | Standard guide for interpreting images of polymeric tissue scaffolds | Amato 123 |

TC 261 published ISO/ASTM 52910:2018 standard “Additive manufacturing—Design—Requirements, guidelines and recommendations,” which describes the design consideration that needs to be taken while manufacturing different types of products or components through the additive manufacturing approach. This standard will provide necessary guidance to the engineers and students to carry out the basic design of additive manufactured products for clinical translation. These design guidelines facilitate the manufacturers to decide on optimal cost, quality and delivery time. Further, this could also be applied to identify the potential of additive manufacturing techniques by assessing the choice of material, its availability, build volume and print volume comparison. 125

ISO in liaison with the governmental, non-governmental and international organizations have also been facilitated to further raise the standards with more expertise in the field. For instance, ISO 261 and ASTM F47 have jointly framed general standards (framing additive manufacturing requirements, guidelines, safety, definition and concepts) and specific/broad category of material based standards (framing material, process or application details) to continuously improve worldwide standards and quality of additive manufactured products without any confusions 126 This also enables the development of new inventions in all fields related to additive manufacturing spanning from the industrial sector to medicine. ISO TC 261 has a group of field expertise called a working group such as WG 1, WG 2, WG 3, WG 4, and WG 6 for the development of standards for manufacturing additive manufactured products. Similarly, several joint groups have been established with different titles such as ISO/TC 261/JG 57 “Joint ISO/TC 261-ASTM F 42 Group: Process-specific design guidelines and standards”, ISO/TC 261/JG 54 “Joint ISO/TC 261-ASTM F 42 Group: Fundamentals of Design”, ISO/TC 261/JG 59 “Joint ISO/TC 261-ASTM F 42 Group: NDT for Additive Manufacturing part”, ISO/TC 261/JG 60 “Joint ISO/TC 261-ASTM F 42 Group: Additive manufacturing—Non-destructive testing and evaluation—Standard guideline for intentionally seeding flaws in parts”, etc. 127 However, all these established standards of ISO are maintained as a catalog where the standards are classified into different ICS (International classification of standards) with specific description level (field, group, subgroup) with codes for better understanding and followed as required.

Clinical research guidelines