Abstract

With the wide spread of electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring during surgery or in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), clinicians can sometimes face the pattern of burst suppression (BS). The BS pattern corresponds to the continuous quasi-periodic alternation between high-voltage slow waves (the bursts) and periods of low voltage or even isoelectricity of the EEG signal (the suppression) and is extremely rare outside ICU and the operative room. BS can be secondary to increased anesthetic depth or be a marker of cerebral damage, as a therapeutic endpoint (i.e. refractory status epilepticus or refractory intracranial hypertension). In this review, we reported the neurophysiological features of BS in order to better define its role during intraoperative and critical care settings.

Keywords: Electroencephalogram, Burst Suppression, Brain Protection, Postoperative cognitive disorders

Introduction

The Central Nervous System (CNS) is profoundly affected by anesthetic drugs which have significant effects on the cerebral cortex and subcortical structures (1–3). Since the brain is the primary organ of general anesthetic effects, it is not surprising that the electroencephalogram (EEG) has entered into the clinical practice (4). As such, anesthesiologists are now better able to distinguish the electroencephalographic signatures of the different anesthetic drugs (5).

Roughly, induction of anesthetic unconsciousness is characterized by changes in the EEG similar to the changes occurring during natural sleep: with increasing doses of general anesthetic agents there is a decrease in the high frequency power toward slow oscillations, although some exceptions and paradoxical effects may be seen with drugs, such as ketamine or nitrous oxide (5). For example, propofol, which is widely used in the operating rooms and critical care settings, has well defined EEG signatures characterized by slow oscillations and alpha activity (6), resembling the sleep spindles of stage 2 of non-rapid eye movements (NREM) sleep (7–8) translating thalamocortical sensory blockade (9).

The electroencephalographic pattern of burst suppression (BS) is commonly found during the general anesthetic state as a result of increased anesthetic depth, but in opposition to the other EEG rhythms and oscillations, which may be seen during sedation and general anesthesia, BS does not appear during physiological sleep or normal EEG recordings (10).

The occurrence of BS during the intraoperative period and in critical care patients has been a focus of research: is it a signal or mediator of cerebral frailty, a cause of neurological damage, an epiphenomenon of anesthetic agents actions on the neural physiology or a necessary surrogate endpoint of pharmacological treatment in several pathological conditions, such as refractory status epilepticus (SE) and uncontrolled high intracranial pressure (ICP).

The present paper reviews the neurophysiological features of BS in order to better define its role during intraoperative and critical care settings.

Burst Suppression: definition and neurological background

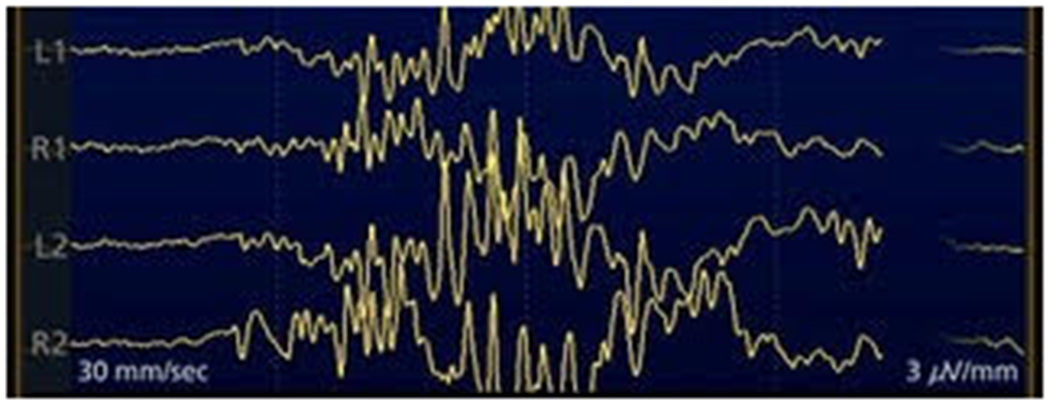

The BS pattern corresponds to the continuous quasi-periodic alternation between high-voltage slow waves (the bursts) and periods of low voltage or even isoelectricity of the EEG signal (the suppression) (10–13) (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

4 EEG channels showing the pattern of BS.

BS was recently defined by the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) as a background with more than 50% of attenuation (≥10μV but <50% of the background voltage) or suppression (<10μV); of note, bursts should have at least 4 phases and last for a minimum of 0.5 sec (up to 30 sec) (14). A slightly differing definition applies to neonates, in whom the ACNS describes BS as a burst of activity separated by a “prolonged” low-voltage (defined as <5μV) inter-burst interval; importantly, neonatal BS should be monotonous and devoid of normal appearing activity within the bursts (15).

In a seminal experiment, researchers applied isoflurane to cats and noted cortical phasic depolarizations associated with bursts of EEG waves, alternating with electrical silence during suppressed epochs; during the latter, neuronal responsiveness was markedly reduced, likely following increase of potassium conductance. In the thalamus, however, only 2/3 of cells were completely silent: the remaining ones discharged rhythmic spike bursts during cortical EEG silence; thalamic cells became silent only when cortical suppression lasted longer than 30 sec (16). This and other observations have contributed to consider that BS may arise when the cortex is disconnected from the underlying structures, particularly the thalamus. However, further studies disclosed that excitability increases during cortical bursts since the brain might be generating bursts to subliminal sensory stimulations that involve the thalamus (17). Abolished inhibition may also represent an underlying mechanism (18): namely the transient depletion of extracellular calcium triggers the alternating cortical EEG suppression (19). It is unclear if these BS observations are readily applicable to humans where BS is usually related to the administration of general anesthetics. In fact, while BS is often encountered in severely ill patients in the ICU, it mostly results from heavy and prolonged sedative administration or as a consequence of prolonged SE (20).

With newborns and infants, early-onset epileptic encephalopathies with BS represent a spectrum of severe conditions arising within the first three months of life (most typically within four weeks). These comprise of two entities: Ohtahara syndrome, characterized by epileptic spasms, at times focal seizures, and an asymmetric EEG (21), and early myoclonic encephalopathy, in which myoclonic discharges clearly predominate (22–23). Etiologically, structural brain malformations, inborn errors of metabolism, such as disorders of pyridoxine (24), or genetic causes (accounting to up to 60% of etiologies in subjects lacking malformations, and most commonly involving potassium channel dysfunction) are involved (23). It is not uncommon to assist to transitions into West syndrome at the age of 3-6 months, and later to Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (22); this suggests an age-specific epileptic reaction to heterogeneous brain insults (21). BS is rarely observed in epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures, another very severe condition related to psychomotor retardation, where multifocal spikes superimposed on background slowing represent the most common EEG finding (25).

In older children or adults, BS is sometimes encountered as a spontaneous occurrence on EEG, and in these cases it is mostly related with severe encephalopathies of structural, metabolic, toxic or infectious origin, which may be reversible. For example, it was reported as an incidental occurrence during behavioral sleep of a three years old child who sustained brain injury two years earlier (26). Discontinuous or burst-suppressed EEG recordings can reflect severe metabolic encephalopathy, of hepatic or other origins, where milder forms classically induce diffuse delta slowing patterns (27). Hypothermia, with temperatures below 24.4°C (28), and severe cerebral hypoxia (29) are common causes of BS in humans.

In conclusion, BS represents a rare finding outside the Intensive Care Unit or Operating Room environment; it has been described in neonates and infants with extreme severe epileptic encephalopathies where its occurrence is part of the syndromic definition, as well in patients with various toxic, metabolic or at times infectious causes.

Burst Suppression and anesthesia

In spite of a profound state of functional inactivation, the brain under deep anesthesia keeps a baseline neuro-electrical dynamic which may be translated by the occurrence of BS. BS during anesthesia results from the administration of high doses of anesthetic agents that act primarily by enhancing GABAA receptors whereas NMDA antagonists rarely induce BS (30).

Mechanisms of BS induced by general anesthetic drugs are the subject of several studies (30). It was suggested to be paradoxically associated with a state of cortical hyperexcitability and that the bursts may be triggered by subliminal stimuli reaching the hyperexcited cortex (17). Ching et al (31), constructing a biophysical computational model, showed that BS may originate from the interaction between neuronal dynamics and brain metabolism: a decrease in cerebral metabolic rate coupled with functional ATP-gated potassium channels leads to the periods of suppression. An alternative mesoscopic model (32) views BS as a result of various origins involving several slow modulating neural circuits.

A remarkable study done in patients undergoing epilepsy surgery showed that the alternation between bursts and periods of suppression induced by propofol can occur in limited cortical areas, while continuous non-BS activity persists in other regions and that when the entire cortex is under a “global burst”, there are differences in the timing of onset of bursts between different cortical regions (33).

Interestingly, different drugs induce distinct electrophysiological patterns of BS. Sevoflurane and propofol were compared in rats (30), showing that propofol causes shorter periods of suppressions and bursts and that the peak-to-peak amplitudes of propofol induced suppressions and bursts that were lower than those induced by sevoflurane.

Independently of the possible mechanisms behind the BS induced by anesthetic agents, there are some questions to be answered and with important implications for the clinical practice.

How to quantify burst suppression?

Taking into account all the possible associations between the presence of BS during general anesthesia and sedation, it is important to be able to quantify its occurrence. There are two essential methods: burst suppression ratio ( BSR) and burst suppression probability (BSP).

The BSR is calculated by dividing the EEG into epochs of bursts and suppressions by a voltage-based scale. Suppression is commonly defined as a voltage less than 5 μV for more than 0.5 s (13). The value of BSR ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no suppression and 1 a suppressed EEG.

The BSP represents the instantaneous probability of the brain being in a suppressed state based on a state-space model (34).

The current EEG monitors, aimed to monitor anesthetic depth, incorporate BSR detection and calculation features, although calculation of absolute duration of suppressed EEG by BSR may be underestimated when compared with visual analysis of intra-operative by skilled neurologists (35).

Are there indications for intra-operative induction of burst-suppression?

For decades, intra-operative brain protection relied on the maximal reduction in cerebral metabolic rate (CMR) with induction of electroencephalographic isoelectricity (36): the decrease in the CMR, the neuronal survival would improve during periods of decreased cerebral blood flow, assuming intact coupling between cerebral metabolism and the cerebral blood flow (37).

Although there is poor evidence supporting the suppression of metabolism as a strategy for brain protection (38–40), it is still widely used by clinicians in a small group of procedures, for example cerebral aneurysm repair with temporary arterial ligation. Drugs like pentobarbital, propofol and etomidate induce BS, allowing for a safe occlusion of the medial cerebral artery, particularly if more than 10 minutes of occlusion time was required. (41)

The use of metabolic suppression guided by EEG burst suppression during surgery when an ischemic insult is expected is no longer viewed as a viable tool for brain protection. Evidence shows that there are regional differences in the coupling between the cerebral blood flow and the cerebral metabolism (42–45), in addition to heterogeneity in the BS occurrence across the entire brain (33).

To protect the brain peri-operatively the clinician should aim for a normal physiological state, with normotension, normovolemia, normocapnia, normoxemia, normoglycemia and normothermia. Nonetheless, hypothermia which is a known cause of burst suppression, remains a key strategy for brain protection in some cardio-vascular surgical procedures and in traumatic brain injury, notwithstanding the trend towards mild hypothermia (46–48).

Burst suppression and postoperative outcomes

Harmful neurocognitive change after anesthesia and surgery is a common occurrence. Perioperative cognitive disorders (PND) includes acute- [postoperative delirium and delayed cognitive recovery] and long-term cognitive changes occurring in the perioperative period (49). PND leads to longer hospital and ICU stays, additional days of mechanical ventilation, and increase in hospital costs (50). After discharge, these patients are at an increased risk of dementia and death.

Basic and clinical studies have yet to identify effective strategies to completely halt the development of brain changes after surgery. While several risk factors have been identified, surgery-induced inflammation is clearly one of the major issues related to the development of PND (51–52). Clearly, its etiology is multifactorial (53), with anesthetic management seated among the many culprits. A number of sedatives induce a “pharmacologically-induced sleep”, with several important differences to natural sleep. While natural sleep normally cycles through a predictable series of phases, general anesthesia is procedure dependent, with sometimes extreme changes in the EEG not seen during physiologic sleep (54). Still, no single EEG pattern characterizes the anesthetized state (55). General anesthetics target the brain and EEG monitoring shows some promise in preventing the development of PND (56).

Early studies attempted to link the depth of anesthesia with the presence of PND but failed to detect significant associations (57–58). In fact, they suggested that cognitive processing speed could be improved with deeper anesthetic levels (59), and that burst suppression could be protective against PND (60). Several other randomized trials attempted to reproduce these initial findings(61–64), but they relied on simple, reductive processed EEG monitors, using dimensionless indexes, such as Bispectral Index (BIS) monitor (Medtronic/Covidien, USA), cerebral state monitor (CSM), SedLine monitor (Masimo Corporation, USA) and others. These studies raised the possible benefits of using EEG monitors to titrate anesthetic drug delivery, including avoidance of specific EEG parameters (65). In general, anesthetic plans were guided by the index values recommended by each manufacturer. By avoiding extreme low values, or by assessing BS ratio in these monitors, the authors were able to demonstrate a decrease in the rate of POD. The results were not consistent, as some studies did not show difference in long term changes (62–63), while others demonstrated that BIS-guided anesthesia could decrease the risk of cognitive decline at three months (61) and 12 months after surgery (66).

By quantifying real-time EEG suppression, it was shown that BS is an independent risk factor for the development of PND (67). Further, the longer the patients remain in intraoperative EEG suppression, the higher the likelihood of developing POD and delayed cognitive recovery (63,67). These studies focused on EEG suppression ratio, a nonproprietary measure, instead of relying on proprietary low EEG indexes. Low values correlated with BS. Of note, these machine-generated values still underestimate the precise time period of EEG suppression, making it necessary to continuously monitor the EEG in order to achieve a more accurate and real-time guidance of the anesthetic plan (35). Of note, distinct intraoperative EEG patterns, such as slower frequencies that correlate with BS, were associated with delirium (68–69).

When looking at the intraoperative management, the B-Unaware Trial (70) and the BAG-RECALL (71) trials showed no reduction in anesthetic administration, when clinicians used processed EEG monitors to guide their practice. The CODA trial showed a decrease in propofol and volatile anesthetics administration (61). Further still, patients had a faster discharge from PACU.3 The effects of intraoperative BS on outcomes is not exclusive for PND. Several other retrospective studies demonstrated the relationship of BS with worse outcomes (63,67), including poorer functional independence, increased PACU stay, myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality (67,72–73). One of the limitations of using intraoperative neuromonitoring is that by changing the anesthetic management (61), it is possible that other components involved in the etiology of PND are also altered. Retrospective studies suggest that a combination of low BIS values, in combination with low arterial pressure (74) and low anesthetic delivery, was associated with an increase of mortality (75). This scenario suggests that a specific phenotype could be at play and that the differentiation between direct effects of anesthetic agents on the brain versus patient’s baseline vulnerability is necessary. If on the one hand, EEG suppression indicates excessive depth of anesthesia with prolonged exposure to general anesthetics, it is possible that there are specific at-risk populations for EEG suppression.

Some studies set out to investigate whether previously reported association between intraoperative EEG suppression and PND could be explained by an underlying phenotype (such as a preoperative subclinical neural pathology), predisposing patient to worse outcomes (76). Surgery and anesthesia serve as a neural “stress test”, pushing patients with underlying brain pathology to develop cognitive deficits. In fact, several patient-related factors were associated with a larger probability of developing increased intraoperative suppression ratio (74,77). Low average anesthetic dose is also as an independent risk factor for delirium (74). A recent study showed the prognostic value of quantitative EEG recorded before surgery (68). Preoperatively slower mean frequency (mobility) and slower peak frequency in the occipital leads were associated with cognitive dysfunction after surgery (68). It also describes how a decrease in anesthesia-induced frontal alpha power was associated with an increased propensity for burst suppression and ultimately higher risk for PND (78). Using BIS, a retrospective cohort study found that patients who experienced EEG suppression at relatively lower concentrations of volatile anesthetics (defined as sensitivity to volatile anesthetic agents) had a higher incidence of delirium (67). This phenotype appears to be a stronger predictor of delirium than the duration of intraoperative EEG suppression. Interestingly, patients with a history of smoking were more likely to demonstrate a heightened sensitivity to volatile agents (56). This raises the question whether microvascular disease could be the mechanism at play underlying this phenotype (73) and if an increased sensitivity to anesthetic is a marker of underlying organ dysfunction and hypoperfusion.

A recent large prospective, multi-institutional study, identified BS and emergence trajectories as predictive of PACU delirium and long-term negative outcomes (73). The changes in EEG suggest the wave morphology contains important information about brain function and health that goes beyond visually scored waveforms or a single processed number. For example, a retrospective analysis indicated that the use of BIS was associated with worse outcomes, without articulating how the information was handled and distilled(79).Interestingly, the recent ENGAGES trial demonstrated that EEG-guided anesthesia, using BIS, did not reduce the incidence of delirium, but did show a decrease in 30-day mortality(80). The study concluded that the use of intraoperative EEG as a physiological variable for clinical management is unnecessary. Some groups perceive these results as a reinforcement that there are major individual differences in the EEG that can relate to a patient’s underlying state of brain health; in fact, in healthy volunteers exposed to BS for over 3h, the authors found no decrements in cognitive task performance(81). What is somewhat less cogent and compelling is the argument that monitoring the brain, toward the advancement of patient health and cognitive outcomes, is unwarranted and pointless.

In conclusion, clinical judgment is crucial when interpreting EEG physiological data. Patient assessment should include evaluation and correlation of EEG data with hemodynamic and other monitoring data, as well as observation of clinical signs that are tailored to the individual. EEG information is additive, providing clinicians with valuable signals for their practice, observation and care. Despite the conflicting, often controversial and complicated use of EEG data, these are still early days in its staging and evaluation, offering many exciting channels for scientific exploration.

Burst suppression in the intensive care unit

Induced burst suppression; burst suppression as a target

Over the last decades, pharmacologic BS has been an area of tremendous interest in the intensive care unit (ICU). (82–83)

The attractive potential of anesthetic drugs (such as barbiturates, propofol, and inhalation agents) to reduce cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen advances their application in the clinical practice to protect the brain in situations of low cerebral blood flow and altered metabolism (83).

Current potential indications for pharmacologic burst suppression, which are based on low-quality studies and unclear evidence, include refractory intracranial hypertension (such as in traumatic brain injury) and the treatment of refractory status epilepticus (84)

Barbiturate coma induction has been traditionally used to lower intracranial pressure (ICP) by suppressing cerebral metabolism and reducing cerebral blood volume in head injured patients when conventional strategies and therapies (such as mannitol, hypothermia and hyperventilation) have failed (85). Results from a meta-analysis of the Cochrane database(85) showed that the use of barbiturates is associated to a pooled risk ratio of death and disability of 1.15 (CI=0.81-1.64), with an increased occurrence of hemodynamic instability and hypotension (RR=1.80, CI=1.19-2.20). Therefore, because of the lack of evidence supporting a beneficial effect on outcome and the risk of complications, at present, the use of barbiturates is restricted only to specific situations of refractory intracranial hypertension, such as a bridge to the decompressive craniectomy to reduce ICP (86–87). In these cases, barbiturate coma should be titrated on ICP and not electroencephalography (EEG), and probably also evaluating the risks and the benefits of treatment.

In refractory status epilepticus, when indicated, therapy with anesthetic drugs need to be titrated to an EEG end point. In general, a 1:10 burst to suppression ratio is chosen as an arbitrary endpoint, with a 10 second screen of EEG, 1 second of burst activity, and 9 seconds of flat-line EEG. However, optimal target and dosing is controversial, and there is no strong evidence to guide therapy (88). Also, maintenance of homeostasis and hemodynamic instability is paramount when barbiturate coma is induced, and arterial blood pressure monitoring, advanced monitoring and frequent blood chemistries are required in this setting.

ACCIDENTAL BS = BS AS A CONSEQUENCE OF THE DISEASE OR THERAPY

Accidental burst suppression on EEG in ICU generally results as an unintended consequence of unnecessarily high cumulative doses of sedative and analgesic medications (89). Indeed, critically ill patients often receive large doses of sedative and analgesic medications that frequently lead to deep sedation. However, growing evidence show that deep sedation has a detrimental effect on various clinical outcome variables, such as prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation, length of ICU and hospital stays, and healthcare costs (90). Also, deep sedation and burst suppression are independent risk factors for post-ICU delirium and cognitive impairment (91–92).

Thus, recent recommendations suggest titrate sedation to the minimal level required to achieve pain relief, comfort, tube tolerance, and to allow valid and frequent clinical assessment (94). Despite the potential clinical relevance of EEG monitoring to determine depth of sedation in ICU patients, its use remains limited in this setting. EEG is often not feasible and difficult to perform routinely as it is expensive and requires a neurophysiologist or trained staff member to interpret it. In this context, processed EEG monitors may be a useful alternative as complementary aids for clinical management (94–95). Among these, the Bispectral Index (BIS) monitor, generally used in the operating room to assess the depth of anesthesia, is a feasible alternative. It uses an algorithm to convert raw EEG data to a readable scale of 0–100, and is also able to detect and demonstrate the presence of burst suppression, and calculate the burst suppression ratio(96). Recently, a fully automatic method, able to provide real time quantitative measure of burst suppression has been validated in a large multicenter study, showed a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 84% (97); similarly, bedside computer algorithms have shown to be useful in reducing the workload of EEG analysis with accuracy (98). In ICU patients, many artifacts coming from patients’ movements or electrical interference with other devices, may occur and lead to inappropriate EEG diagnosis or therapies. As such, a basic knowledge of the raw EEG signal is required to implement its use as a routine monitoring tool in this setting.

Finally, burst suppression can be observed in patients suffering from post-anoxic brain injury. In the absence of confounders, such as high-dose propofol or volatile anesthetics, and if the appropriate nomenclature is used, BS is considered as an ominous sign and is associated with poor neurological outcome in most of the patients (28, 99–101).

Practice Points

|Burst Suppression is an electroencephalographic pattern occurring in distinct neurological disorders and when patients are under the effects of high doses of anesthetic drugs.

|Clinical judgment is crucial when interpreting EEG physiological data. Patient assessment should include evaluation and correlation of EEG data with hemodynamic and other monitoring data, as awell as observation of clinical signs that are tailored to the individual in order to avoid development of perioperative neurocognitive disorders

|Currently, the potential indications for pharmacologic burst suppression in intensive care include the treatment of refractory intracranial hypertension or status epilepticus

|Accidental burst suppression in ICU is the result of unnecessarily high cumulative doses of sedative and analgesic medications and may be associated with poor outcome.

Research Agenda

|Further work is needed to determine the mechanisms of BS and the dynamics of BS during anesthesia.

|We need evidence of benefits of induction of BS when perioperative ischemic insults are expected to happen

|We need to understand specific at-risk populations for EEG suppression and development of perioperative neurocognitive disorders.

|Adequately powered observational data or pragmatic trials evaluating the effect of BS on critical patients’ outcome are needed.

Acknowledgments

• Stefano Romagnoli MD, PhD for the Figure 1

• Susana Vacas is supported by grants R21AG07269, K23 GM132795

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests

-None

Contributor Information

Francisco Almeida Lobo, Anesthesiology Department, Centro Hospitalar de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Avenida da Noruega – Lordelo, 5000-508 Vila Real, Portugal

Susana Vacas, Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, 757 Westwood Plaza #3325, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States

Andrea O Rossetti, Department of Neurology, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, CH-1011 Lausanne, Switzerland.

Chiara Robba, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria San Martino di Genova, Largo Rosanna Benzi,15, 16100 Genova, Italy.

Fabio Silvio Taccone, Hopital Érasme, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Route de Lennik 808, 1070 Brussels, Belgium.

References

- 1.Ries CR, Puil E. Mechanisms of anesthesia revealed by shunting actions of isoflurane on thalamocortical neurons. J Neurophysiol 1999; 81(4):1795–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antognini JF, Carstens E, Sudo M et al. Isoflurane depresses electroencephalographic and medial thalamic responses to noxious stimulation via an indirect spinal action. Anesth Analg 2000. 91(5):1282–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velly LJ, Rey MF, Bruder NJ et al. Differential dynamic of action on cortical and subcortical structures of anesthetic agents during induction of anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2007; 107(2):202–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montupil J, Defresne A, Bonhomme V. The raw and processed electroencephalogram as a monitoring and diagnostic tool. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019; 33 Suppl 1: S3–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purdon PL, Sampson A, Pavone KJ et al. Clinical Electroencephalography for anesthesiologists: Part I: background and basic signatures. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(4): 937–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purdon PL, Pierce ET, Mukamel EA et al. Electroencephalogram signatures of loss and recovery of consciousness from propofol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(12): E1142–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferenets R, Lipping T, Suominen P et al. Comparison of the properties of EEG spindles in sleep and propofol. Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006; 2006:6356–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy M, Bruno MA, Riedner BA et al. Propofol anesthesia and sleep: a high-density EEG study. Sleep 2011; 34(3): 283–91A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soplata AE, McCarthy MM, Sherfey J et al. Thalamocortical control of propofol phase-amplitude coupling. PLoS Comput Biol 2017; 13(12):e1005879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amzica F What does burst suppression really mean? Epilepsy Behav 2015; 49:234–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swank RL, Watson CW. Effects of barbiturates and ether on spontaneous electrical activity of dog brain. J Neurophysiol 1949; 12(2):137–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry CE, Scoville WB. Suppression-burst activity from isolated cerebral cortex in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1952; 4(1): 1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rampil IJ. A primer for EEG signal processing in anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1998; 89(4):980–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch LJ, LaRoche SM, Gaspard N et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society standardized critical care EEG terminology: 2012 version. J Clin Neurophysiol 2013; 30(1):1–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuchida TN, Wusthoff CJ, Shellhaas RA et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society standardized EEG terminology and categorization for the description of continuous EEG monitoring in neonates: report of the American Clinical Society Critical care monitoring committee. J Clin Neurophysiol 2013; 30(2): 161–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steriade M, Amzica F, Contreras D. Cortical and thalamic cellular correlates of electroencephalographic burst-suppression. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1994; 9081):1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroeger D, Amzica F. Hypersensitivity of the anesthesia-induced comatose brain. J Neurosci 2007; 27(39): 10597–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferron JF, Kroeger D, Chever O et al. Cortical inhibition during burst suppression induced with isoflurane anesthesia. J Neurosci 2009; 29(31): 9850–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amzica F Basic physiology of burst suppression. Epilepsia. 2009;50 Suppl 12:38–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treiman DM. Electroclinical features of status epilpeticus. J Clin Neurophysiol 1995; 12(4):343–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamatogi Y, Ohtahara S. Early-infantile epilpetic encephalopathy with suppression-bursts, Ohtahara syndrome; its overview referring t our 16 cases. Brain Dev 2002; 24(1):13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalser J, Cross JH. The epileptic encephalopathy jungle - from Dr West to the concepts of aetiology-related and developmental encephalopathies. Curr Opin Neurol 2018; 31(2): 216–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson HE, Kelly M, LaCoursiere CM et al. Genetics and genotype-phenotype correlations in early onset epileptic encephalopathy with burst suppression. Ann Neurol 2017; 81(3): 419–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerin A, Aziz AS, Mutch C et al. Pyridox(am)ine-5-phosphate oxidase deficiency tretable cause of neonatal epileptic encephalopathy with burst suppression: case report and review of the literature. J Child Neurol 2015; 30(9):1218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshitomi S, Takahashi Y, Imai K et al. Different types of suppression-burst patterns in patients with epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures (EIMFS). Seizure. 2019; 65:118–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kheder A, Bianchi MT, Westover MB. Burst suppression in sleep in a routine outpatient EEG. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2014; 2:71–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foley JM, Watson CW, Adams RD. Significance of the electroencephalographic changes in hepatic coma. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1950; 51:161–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stecker MM, Cheung AT, Pochettino A et al. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest: I. Effects of cooling on electroencephalogram and evoked potentials. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(1):14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toet MC, Hellstrom-Westas L, Groenendaal F et al. Amplitude integrated EEG 3 and 6 hours after birth in full term neonates with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999; 81(1): F19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenny JD, Westover MB, Ching S et al. Propofol and sevoflurane induce distinct burst suppression patterns in rats. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014; 8:237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ching S, Purdon PL, Vijayan S et al. A neurophysiological-metbaolic model for burst-suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012; 109(8):3095–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liley DT, Walsh M. The mesoscopic modeling of burst suppression during anesthesia. Front Comput Neurosci 2013; 7:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis LD, Ching S, Weiner VS et al. Local cortical dynamics of burst suppression in the anaesthetized brian. Brain. 2013; 136:2727–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chemali J, Ching S, Purdon PL et al. Burst Suppression probability algorithms:state-space methods for tracking EEG burst suppression. J Neural Eng. 2013; 10(5):056017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muhlhofer WG, Zak R, Kamal T et al. Burst-suppression ratio underestimates absolute duration of electroencephalogram suppression compared with visula analysis of intraoperative electroencephalogram. Br J Anaesth. 2017; 118(5): 755–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michenfelder JD. The interdependency of cerebral functional and metabolic effects following massive doses of thiopental in the dog. Anesthesiology. 1974; 41(3):231–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall R, Murdoch J. Brain Protection: physiological and pharmacological considerations. Part II: the pharmacology of brain protection. Can J Anaesth 1990; 37(7): 762–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drummond JC. Brain Protection during anesthesia. A reader’s guide. Anesthesiology. 1993;79(5): 877–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badenes R, Gruenbaum SE, Bilotta F. Cerebral protection during neurosurgery and stroke. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015; 28(5):532–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bilotta F, Gelb AW, Stazi E et al. Pharmacological perioperative brain neuroprotection: a qualitative review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Anaesth. 2013; 110 Suppl 1:i113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavine SD, Masri LS, Levy ML et al. Temporary occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in intracranial aneurysm surgery: time limitation and advantage of brain protection. J Neurosurg 1997; 87(6): 817–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lou HC, Edvinsson L, MacKenzie ET. The concept of coupling blood flow to brain function: revision required? Ann Neurol. 1987; 22(3): 289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gur RC, Ragland JD, Reivich M et al. Regional differences in the coupling between resting cerebral blood flow and metabolism indicate action preparedness as a default state. Cereb Cortex. 2009; 19(2): 375–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buxton RB, Griffeth VEM, Simon AB et al. Variability of the coupling of blood flow and oxygen metabolism responses in the brain: a problem for interpreting BOLD studies but potentially a new window on the underlying neural activity. Front Neurosci. 2014; 8:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ances BM, Leontiev O, Perthen JE et al. Regional differences in the coupling of cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism changes in response to activation: implications for BOLD-fMRI. Neuroimage. 2008; 39(4): 1510–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reed H, Berg KB, Janelle GM. Aortic Surgery and deep-hypothermic circulatory arrest: anesthetic update. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014; 18(2): 137–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hessel EA 2nd. What’s new in cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019; 33(8): 2296–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Engelman R, Baker RA, Likosky DS et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and The American Society of ExtraCorporeal Technology: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Bypass--Temperature Management During Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015; 100(2):748–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evered L, Silbert B, Knopman DS, et al. Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Cognitive Change Associated With Anaesthesia and Surgery-2018. Anesthesia Analgesia. 2018;127(5):1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, et al. Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vacas S, Degos V, Feng X, Maze M. The neuroinflammatory response of postoperative cognitive decline. British medical bulletin. 2013;106:161–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vacas S, Degos V, Tracey KJ, Maze M. High-mobility group box 1 protein initiates postoperative cognitive decline by engaging bone marrow-derived macrophages. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(5):1160–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons - Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 1996;275:852–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watson PL. Measuring sleep in critically ill patients: beware the pitfalls. Crit Care. 2007;11(4):159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vacas S, Kurien P, Maze M. Sleep and anesthesia: Common mechanisms of action. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2013;8(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vacas S, Hudson AE. Seen and Ignored: Are We Undermining Studies of Brain Health Interventions Before We Start? Anesthesia and analgesia. 2020;131(2):464–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steinmetz J, Christensen KB, Lund T, Lohse N, Rasmussen LS. Long-term consequences of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(3):548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shu AH, Wang Q, Chen XB. Effect of different depths of anesthesia on postoperative cognitive function in laparoscopic patients: a randomized clinical trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(10):1883–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farag E, Chelune GJ, Schubert A, Mascha EJ. Is depth of anesthesia, as assessed by the Bispectral Index, related to postoperative cognitive dysfunction and recovery? Anesthesia and analgesia. 2006;103:633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deiner S, Luo X, Silverstein JH, Sano M. Can Intraoperative Processed EEG Predict Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction in the Elderly? Clin Ther. 2015;37(12):2700–2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chan MTV, Cheng BCP, Lee TMC, Gin T, Grp CT. BIS-guided Anesthesia Decreases Postoperative Delirium and Cognitive Decline. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. 2013;25(1):33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Radtke FM, Franck M, Lendner J, Krüger S, Wernecke KD, Spies CD. Monitoring depth of anaesthesia in a randomized trial decreases the rate of postoperative delirium but not postoperative cognitive dysfunction. British journal of anaesthesia. 2013;110 Suppl i98–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soehle M, Dittmann A, Ellerkmann RK, Baumgarten G, Putensen C, Guenther U. Intraoperative burst suppression is associated with postoperative delirium following cardiac surgery: a prospective, observational study. BMC anesthesiology. 2015;15:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Punjasawadwong Y, Chau-In W, Laopaiboon M, Punjasawadwong S, Pin-On P. Processed electroencephalogram and evoked potential techniques for amelioration of postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction following non-cardiac and non-neurosurgical procedures in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018;5:Cd011283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamada T, Vacas S, Gricourt Y, Cannesson M. Improving Perioperative Outcomes Through Minimally Invasive and Non-invasive Hemodynamic Monitoring Techniques. Frontiers in Medicine. 2018;5(144). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon BC, Sigl JC. Anesthetic management and one-year mortality after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2005;100:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fritz BA, Kalarickal PL, Maybrier HR, et al. Intraoperative Electroencephalogram Suppression Predicts Postoperative Delirium. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2016;122(1):234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hofsté WJ, Linssen CA, Boezeman EH, Hengeveld JS, Leusink JA, de-Boer A. Delirium and cognitive disorders after cardiac operations: relationship to pre- and intraoperative quantitative electroencephalogram. Int J Clin Monit Comput. 1997;14(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arom KV, Cohen DE, Strobl FT. Effect of intraoperative intervention on neurological outcome based on electroencephalographic monitoring during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48(4):476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al. Anesthesia awareness and the bispectral index. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whitlock EL, Torres BA, Lin N, et al. Postoperative delirium in a substudy of cardiothoracic surgical patients in the BAG-RECALL clinical trial. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2014;118(4):809–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leslie K, Myles PS, Forbes A, Chan MT. The effect of bispectral index monitoring on long-term survival in the B-aware trial. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2010;110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hesse S, Kreuzer M, Hight D, et al. Association of electroencephalogram trajectories during emergence from anaesthesia with delirium in the postanaesthesia care unit: an early sign of postoperative complications. British journal of anaesthesia. 2019;122(5):622–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Willingham M, Ben Abdallah A, Gradwohl S, et al. Association between intraoperative electroencephalographic suppression and postoperative mortality. British journal of anaesthesia. 2014;113(6):1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sessler DI, Sigl JC, Kelley SD, et al. Hospital stay and mortality are increased in patients having a ‘Triple Low’ of low blood pressure, low bispectral index, and low minimum alveolar concentration of volatile anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2012;116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fritz BA, Maybrier HR, Avidan MS. Intraoperative electroencephalogram suppression at lower volatile anaesthetic concentrations predicts postoperative delirium occurring in the intensive care unit. British journal of anaesthesia. 2018;121(1):241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Besch G, Liu N, Samain E, et al. Occurrence of and risk factors for electroencephalogram burst suppression during propofol-remifentanil anaesthesia. British journal of anaesthesia. 2011;107(5):749–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shao YR, Kahali P, Houle TT, et al. Low Frontal Alpha Power Is Associated With the Propensity for Burst Suppression: An Electroencephalogram Phenotype for a “Vulnerable Brain”. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Susano MJ, Scheetz SD, Grasfield RH, et al. Retrospective Analysis of Perioperative Variables Associated With Postoperative Delirium and Other Adverse Outcomes in Older Patients After Spine Surgery. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. 2018:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wildes TS, Mickle AM, Ben Abdallah A, et al. Effect of Electroencephalography-Guided Anesthetic Administration on Postoperative Delirium Among Older Adults Undergoing Major Surgery. Jama. 2019;321:473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shortal BP, Hickman LB, Mak-McCully RA, et al. Duration of EEG suppression does not predict recovery time or degree of cognitive impairment after general anaesthesia in human volunteers. British journal of anaesthesia. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Claassen J, Mayer SA, Kowalski RG et al. Detection of electrographic seizures with continuous EEG monitoring in critically ill patients. Neurology. 2004; 62(10):1743–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Friedman D, Claassen J, Hirsch LJ. Continuous electroencephalogram monitoring in the intensive care unit. Anesth Analg. 2009. 109(2):506–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnson EL, Martinez NC, Ritzl EK. EEG Characteristics of Successful Burst Suppression for Refractory Status Epilepticus. Neurocrit Care 2016; 25(3):407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roberts I, Sydenham E. Barbiturates for acute traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 12(12): CD000033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.guidelines for the management of severe TBI, 4th Edition. Brain Trauma Foundation, available at www.braintrauma.org [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stocchetti N, Maas AIR. Traumatic intracranial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2121–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Akrawi WP, Drummond JC, Kalkman CJ et al. A comparison of the electrophysiologic characteristics of EEG burst-suppression as produced by isoflurane, thiopental, etomidate, and propofol. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1996; 8(1): 40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Azabou E, Magalhaes E, Braconnier A et al. Early Standard Electroencephalogram Abnormalities Predict Mortality in Septic Intensive Care Unit Patients. PLoS One. 2015; 10(10):e0139969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hosokawa K, Gaspard N, Su F et al. Clinical neurophysiological assessment of sepsis-associated brain dysfunction: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2014; 18(6):674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Watson PL, Shintani AK, Tyson R et al. Presence of electroencephalogram burst suppression in sedated, critically ill patients is associated with increased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36(12) 3171–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Andresen JM, Girard TD, Pandharipande PP et al. Burst suppression on processed electroencephalography as a predictor of postcoma delirium in mechanically ventilated ICU patients. Crit Care Med. 2014; 42(10):2244–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reade MC, Finfer S. Sedation and delirium in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370(5):444–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cloostermans MC, de Vos CC, van Putten MJAM. A novel approach for computer assisted EEG monitoring in the adult ICU. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011; 122(10): 2100–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Putten MJAM, Kind T, Visser F et al. Detecting temporal lobe seizures from scalp EEG recordings: a comparison of various features. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005; 116(10): 2480–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bruhn J, Bouillon TW, Shafer SL. Bispectral index (BIS) and burst suppression: revealing a part of the BIS algorithm. J Clin Monit Comput. 2000; 16(8): 593–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Furbass F, Herta J, Koren J et al. Monitoring burst suppression in critically ill patients: Multi-centric evaluation of a novel method. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127(4):2038–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Herta J, Koren J, Furbass F et al. Applicability of NeuroTrend as a bedside monitor in the neuro ICU. Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128(6):1000–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Young GB. The EEG in coma. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2000; 17(5):473–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Backman S, Cronberg T, Friberg H et al. Highly malignant routine EEG predicts poor prognosis after cardiac arrest in the Target Temperature Management trial. Resuscitation. 2018; 131: 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Amorim E, Rittenberger JC, Baldwin ME et al. Malignant EEG patterns in cardiac arrest patients treated with targeted temperature management who survive to hospital discharge.Resuscitation. 2015; 90: 127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]