Abstract

Background

Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS) is one of the leading causes of bacteraemia in sub-Saharan Africa. We aimed to provide a better understanding of the genetic characteristics and transmission patterns associated with multi-drug resistant (MDR) iNTS serovars across the continent.

Methods

A total of 166 iNTS isolates collected from a multi-centre surveillance in 10 African countries (2010–2014) and a fever study in Ghana (2007–2009) were genome sequenced to investigate the geographical distribution, antimicrobial genetic determinants and population structure of iNTS serotypes–genotypes. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in the context of the existing genomic frameworks for various iNTS serovars. Population-based incidence of MDR-iNTS disease was estimated in each study site.

Results

Salmonella Typhimurium sequence-type (ST) 313 and Salmonella Enteritidis ST11 were predominant, and both exhibited high frequencies of MDR; Salmonella Dublin ST10 was identified in West Africa only. Mutations in the gyrA gene (fluoroquinolone resistance) were identified in S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium in Ghana; an ST313 isolate carrying blaCTX-M-15 was found in Kenya. International transmission of MDR ST313 (lineage II) and MDR ST11 (West African clade) was observed between Ghana and neighbouring West African countries. The incidence of MDR-iNTS disease exceeded 100/100 000 person-years-of-observation in children aged <5 years in several West African countries.

Conclusions

We identified the circulation of multiple MDR iNTS serovar STs in the sampled sub-Saharan African countries. Investment in the development and deployment of iNTS vaccines coupled with intensified antimicrobial resistance surveillance are essential to limit the impact of these pathogens in Africa.

Keywords: epidemiology, medical microbiology, typhoid and paratyphoid fevers, cross-sectional survey

Key questions.

What is already known?

Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS) disease is an emerging pathogen in sub-Saharan Africa.

iNTS is now a leading cause of bacteraemia in sub-Saharan Africa.

The disease is associated with specific sequence types of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium.

Key questions.

What are the new findings?

iNTS disease is widespread across the sampled locations.

Salmonella Typhimurium sequence-type (ST) 313 and Salmonella Enteritidis ST11 are the predominant pathogens.

There is a high frequency of multi-drug resistant (MDR) phenotypes.

The incidence of MDR-iNTS disease exceeded 100/100 000 person-years-of-observation in children aged <5 years in several West African countries.

What do the new findings imply?

Sustained disease surveillance of MDR-iNTS organisms is essential.

There is a need for acceleration of iNTS vaccines.

We need a better understanding of the disease reservoir and human-to-human transmission.

Background

The non-typhoidal members of Salmonella enterica are archetypal zoonotic pathogens typically associated with self-limiting diarrhoea in humans. However, certain non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars are also a recognised cause of invasive disease in specific geographical regions. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella (iNTS) is most commonly observed in infants and young adults with HIV, malaria and malnutrition.1 Annually, there are an estimated 3.4 million cases of iNTS globally, 20% of which are fatal.2 3 The vast majority of iNTS disease is reported in sub-Saharan Africa, where annual incidence rates of 175–388 cases per 100 000 person-years and case fatality rates as high as 25% have been reported in young children.4–6 A recent multi-centre study across 10 countries in sub-Saharan Africa identified iNTS as a major cause of bacteraemia in febrile patients, with incidence rates exceeding 100 cases per 100 000 person-years recorded in multiple sampling locations.7

Various Salmonella serovars have been associated with iNTS disease, including S. Isangi,8 S. Concord,9 S. Stanleyville and S. Dublin.10 However, the majority of iNTS infections in sub-Saharan Africa can be attributed to S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis.11 12 Salmonella Typhimurium iNTS in sub-Saharan Africa is largely associated with a multi-drug resistant (MDR; resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole) variant of ST313, which comprised two major lineages (I and II).11 Salmonella Enteritidis account for approximately one-third of the iNTS cases reported in sub-Saharan Africa and are primarily associated with genotype ST11. There are three major clades of S. Enteritidis ST11 (Global epidemic, West African and Central/East African clades) co-circulating in this region, in which MDR phenotypes are common.13

Ampicillin, chloramphenicol and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole) have traditionally served as first-line treatment for iNTS and typhoid fever in Africa.14 The widespread use of these antimicrobials likely led to the emergence and spread of MDR iNTS organisms. Several sub-Saharan African countries have reported MDR iNTS, including Malawi,15–17 Kenya,18–20 Ghana,21 Gambia,5 Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC),22 Mozambique,23 24 Tanzania,25 Burkina Faso,7 Guinea-Bissau7 and Nigeria.26 Consequently, alternative treatments, such as ciprofloxacin, azithromycin and ceftriaxone, are used increasingly to manage bloodstream infections. However, these drugs may be unavailable or costly, and resistance is emerging to these antimicrobial agents.17 Concerningly, extensively drug-resistant (XDR) (MDR plus resistance to fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins) S. Typhimurium ST313 organisms have been reported in Kenya,14 27 Malawi28 and DRC.29 These new resistance phenotypes pose a significant challenge for the control of iNTS disease.14

Here, we subjected a contemporaneous collection of iNTS organisms from multiple sites in sub-Saharan Africa to whole genome sequencing to investigate the phylogenetic distribution of these organisms and their corresponding sequence types (STs) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) determinants. We also estimated the incidence rates of MDR iNTS disease in the sampling locations and performed phylogenetic analyses of S. Typhimurium ST313 and S. Enteritidis ST11 in a global context.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was conducted under the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The IVI Institutional Review Board (IRB), the national ethical review committees in each participating country, and local research ethics committees approved the study protocol. All eligible patients meeting the study inclusion criteria were provided with a detailed explanation of the study purpose, and written informed consent was obtained prior to study enrolment. For children, written informed consent was obtained from parent or guardian.30

Study design and inclusion criteria

The majority of iNTS isolates (117/166) in this study originated from the Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program (TSAP),30 conducted in 13 sites in 10 countries between 2010 and 2014. Febrile patients from all age groups (except in Ghana, where only children aged <15 years were enrolled) with a tympanic or axillary temperature of ≥38.0℃ or ≥37.5℃, respectively, living in a defined study catchment area were eligible for recruitment. For inpatients, reported fever within 72 hours of admission was also necessary for inclusion. Written informed consent/assent was obtained. Clinical assessments of patients included history of illness, physical examination and clinical appraisal. Blood samples (5–10 mL for adults; 1–3 mL for children) were collected for microbiological testing and diagnosis. An additional 49 iNTS isolates were obtained from a febrile surveillance study conducted at the Presbyterian Hospital of Agogo in Ghana, between 2007 and 2009.31

Patient and public involvement statement

This TSAP study was performed under a single protocol with some site-specific and country-specific details; these details were developed with the study sites and local patient groups and communities attending the healthcare facilities. These data were essential for establishing the demographic framework of the sites and understanding how patients accessed healthcare and disease diagnosis. Therefore, these patient/community groups informed the study design to address issues regarding healthcare access and practices. Local communities and patients acted as communicators in the local communities to encourage people to attend healthcare facilities when symptomatic. Data from the studies have been provided to study sites to inform the local community and patients of the study findings.

Bacterial isolates and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Blood specimens were inoculated into an aerobic blood culture bottle and incubated in systems with automated growth detection (BACTEC Peds Plus Medium/BACTECT Plus Aerobic-F, BACTEC, Becton-Dickinson, New Jersey; or BacT/ALERT PF Paediatric FAN/BacT/ALERT FA FAN Aerobic, bioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Blood cultures with bacterial growth were sub-cultured on blood and chocolate agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK), and biochemical tests were conducted (API 20E; bioMerieux) to identify suspected Salmonella isolates.30 Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using agar diffusion tests according to the Clinical Laboratory and Standards Institute guidelines.30

Data sources and bacterial isolates

A total of 166 iNTS isolates were used for this investigation, which comprised 94 iNTS isolates from the TSAP study, an additional 23 iNTS isolates obtained from outside predefined TSAP study catchment areas and 49 iNTS isolates from other studies. In order to place these S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis isolates into a global phylogenetic context, the existing datasets were incorporated: 147 iNTS serotype Typhimurium ST313 isolates from seven countries (Malawi, Kenya, Mozambique, Uganda, DRC, Nigeria and Mali),11 Nigeria and DRC,12 Malawi,28 Kenya,14 Malawi32 and 594 iNTS serotype Enteritidis ST11 isolates (selected from Feasey et al13; online supplemental table 1).

bmjgh-2021-005659supp001.pdf (550.3KB, pdf)

Whole genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from all Salmonella isolates using the Wizard Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Promega, Wisconsin, USA). Two micrograms of genomic DNA from each organism was subjected to indexed-tagged pair-end sequencing on an Illumina Hiseq 2000 platform (Illumina, CA, USA) at the Wellcome Sanger Institute to generate 100 bp paired-end reads. Data quality control was performed using in-house pipelines. Raw sequence data are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (Project number: ERP009684, ERP010763, ERP013866) (online supplemental table 2).

bmjgh-2021-005659supp002.pdf (63.7KB, pdf)

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling and analyses

Raw Illumina reads were used to create multiple assemblies using Velvet V.1.233 with parameters optimised using VelvetOptimiser V.2.2.5,34 35 and automated annotation was performed using PROKKA V.1.5.36 Roary37 was used to define the pan genome of 166 iNTS isolates with blastp percentage identity of 99% and a core definition of 99%. In total, 3450 core genes were identified (genes that were present in ≥99% strains) and 86 765 SNP sites were extracted from the core gene alignment using SNP-sites V.2.1.3.35

For S. Typhimurium ST313, raw Illumina reads of 99 isolates from this study and 147 S. Typhimurium ST313 from previous studies11 12 29 33 38 were mapped to the reference sequence of S. Typhimurium strain SL1344 (accession: FQ312003.1), using SMALT V.0.7.4 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/smalt/). Candidate SNPs were called against the reference sequence using SAMtools38 and filtered with a minimum mapping quality of 30 and minimum consensus base agreement of 75%. The allele at each locus in each isolate was determined by reference to the consensus base in that genome using SAMtools mpileup and removing low confidence alleles with consensus base quality ≤20, read depth ≤5 or a heterozygous base call. The repeat finding program in NUCmer V.3.139 was used to identify exact repetitive regions of ≥20 bp in length in the reference genome and SNPs called in these regions were excluded. SNPs called in phage sequences and recombinant regions identified using Gubbins40 were further removed, resulting in a final set of 1960 chromosomal SNPs. The identification of SNPs for S. Enteritidis ST11 was performed following the same procedure as S. Typhimurium ST313. Briefly, the raw Illumina reads of 28 S. Enteritidis ST11 isolates from this study and 594 additional isolates from a global collection13 were mapped to the reference sequence of S. Enteritidis strain P125109 (accession: NC_011294.1), using SMALT followed by SNP calling and filtering as described previously, resulting in a final set of 25 121 SNPs.

Phylogenetic analyses

A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was constructed from the 86 765 SNP alignment of all 166 iNTS isolates using RAxML V.8.2.8 with a generalised time-reversible model and a Gamma distribution to model the site-specific rate variation (GTRGAMMA).41 Clade support for this tree was assessed through a bootstrap analysis with 100 pseudo-replicates. To investigate the molecular epidemiology of the S. Typhimurium ST313 and S. Enteritidis ST11 isolates sequenced here in a global context, a ML tree was inferred from an alignment of 1960 SNPs for 246 S. Typhimurium ST313 (99 from this study and 147 from previous studies11 12 29 33 38) and an alignment of 25 121 SNPs for 622 S. Enteritidis ST11 isolates (28 from this study and 594 from a global collection13), using RAxML with GTRGAMMA model. Support for these phylogenetic trees was assessed through a 100 bootstrap pseudo-analysis. Tree annotation was visualised using ITOL.42

Antimicrobial resistance gene and plasmid analyses

From raw Illumina reads, Short Read Sequence Typing-SRST243 was used to identify acquired AMR genes and their precise alleles using the ARG-Annot database,44 as well as plasmid replicons using the PlasmidFinder database.45 Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of all iNTS isolates was also determined using SRST2 together with the MLST database for Salmonella enterica downloaded from pubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/salmonella-spp).46 Salmonella serotypes were identified using conventional serology as well as MLST-based approach47 and SeqSero (genome-based approach)48; the final interpretation followed a consensus of MLST and SeqSero. Bandage49 was used to investigate the assembled contigs carrying the AMR cassettes. Mutations in fluoroquinolone resistance genes (gyrA, gyrB, parC, parE) were identified using SeaView.50

Incidence analyses of MDR iNTS disease

Incidence rates of MDR iNTS were estimated for study sites in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya and Senegal. Statistical methodology used previously to calculate the incidence of S. Typhi and iNTS disease in the TSAP study was used to calculate MDR iNTS incidence.7 30 51 Demographic data from Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) sites were used to estimate population denominators where available. In non-HDSS sites, health-seeking behaviour as reported by randomly administered healthcare utilisation surveys were used to estimate population denominators for each study site. Crude incidence rates were adjusted to account for the proportion of surveyed individuals who reported seeking care for a febrile episode at a study facility to yield adjusted incidence rates. Adjusted incidence rates of MDR iNTS cases per 100 000 per person-years-of-observation (PYO) were estimated with 95% CIs using these adjustment factors and crude MDR iNTS case numbers. The previously established multi-country database (Microsoft Visual FoxPro 7.0, Redmond, Washington) for TSAP was used for the countries with MDR iNTS isolates.

Results

Geographical distribution of iNTS serotypes and sequence types

The majority (66%; 110/166) of iNTS organisms in the sampled sub-Saharan African countries were S. Typhimurium, of which 90% (99/110) were ST313 and 10% (11/110) were ST19. S. Enteritidis accounted for 18% (30/166) of the isolates, composed of ST11 (93.3%; 28/30), ST183 (3.3%; 1/30) and ST2107 (3.3%; 1/30). S. Dublin (ST10) comprised a further 11% (18/166) of isolates. Several other serotype STs, including S. Choleraesuis ST145 (3/166), S. Muenster ST321 (1/166), S. Poona ST308 (1/166), S. Stanleyville ST339 (1/166) and S. Virchow ST359 (1/166), were also identified. S. Typhimurium ST313 was mostly limited to West Africa (table 1), whereas S. Enteritidis ST11 appeared to be pervasive in both West and Southern Africa. S. Dublin ST10 was identified in West Africa and S. Typhimurium ST19 was distributed across the continent.

Table 1.

Distribution of iNTS serovars and genotypes circulating in the sampled countries in sub-Saharan Africa

| Country (number of iNTS*) (a) |

Serovars | Number of iNTS per serovar (b) |

% of total number of iNTS per country (b)/(a) |

Genotype (sequence type) |

Number of iNTS per genotype (c) |

% of total number of iNTS per country (c)/(a) |

| Burkina Faso (12) | Typhimurium | 7 | 58 | 313 | 6 | 50 |

| 19 | 1 | 8 | ||||

| Enteritidis | 4 | 33 | 11 | 4 | 33 | |

| Dublin | 1 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 8 | |

| Ghana (133) | Typhimurium | 92 | 69 | 313 | 90 | 68 |

| 19 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Enteritidis | 20 | 15 | 11 | 18 | 14 | |

| 183 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2107 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Dublin | 17 | 13 | 10 | 17 | 13 | |

| Muenster | 1 | 1 | 321 | 1 | 1 | |

| Poona | 1 | 1 | 308 | 1 | 1 | |

| Stanleyville | 1 | 1 | 339 | 1 | 1 | |

| Virchow | 1 | 1 | 359 | 1 | 1 | |

| Guinea-Bissau (9) | Typhimurium | 5 | 56 | 313 | 2 | 22 |

| 19 | 3 | 33 | ||||

| Enteritidis | 1 | 11 | 11 | *1 | 11 | |

| Choleraesuis | 3 | 33 | 145 | 3 | 33 | |

| Kenya (1) | Typhimurium | 1 | 100 | 313 | 1 | 100 |

| Madagascar (4) | Typhimurium | 1 | 25 | 19 | *1 | 25 |

| Enteritidis | 3 | 75 | 11 | ‡3 | 75 | |

| Senegal (2) | Typhimurium | 1 | 50 | 19 | *1 | 50 |

| Enteritidis | 1 | 50 | 11 | *1 | 50 | |

| South Africa (1) | Enteritidis | 1 | 100 | 11 | *1 | 100 |

| Tanzania (4) | Typhimurium | 3 | 75 | 19 | 3 | 75 |

| Unknown | 1 | 25 | 2533 | 1 | 25 |

| Total 8 countries† (166 iNTS isolates) (d) | Serovars | Number of iNTS per serovar (e) | % of total number of iNTS in all 8 countries (e)/(d) | Genotype (sequence type) | Number of iNTS per genotype (f) | % of total number of iNTS in all 8 countries (f)/(d) |

| Typhimurium | 110 | 66 | ST313 | 99 | 60 | |

| ST19 | 11 | 7 | ||||

| Enteritidis | 30 | 18 | ST11 | 28 | 17 | |

| Other STs‡ | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Dublin | 18 | 11 | ST10 | 18 | 11 | |

| Others | 8 | 5 | Other STs§ | 8 | 5 |

*iNTS: invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella.

†Total 8 countries: Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Madagascar, Senegal, South Africa and Tanzania presented in this table. No iNTS isolates were yielded in Sudan and Ethiopia.

‡Other sequence types of S. Enteritidis detected: 1 ST183 (isolate yielded from Ghana; age/sex unknown due to missing data) and 1 ST2107 (from Ghana; a 22-year-old woman); both non-MDR and no antimicrobial resistant genes detected.

§Sequence types of the other NTS serovars: 1 Muenster ST321 (yielded from Ghana; age/sex/year unknown due to missing data), 1 Poona ST308 (yielded from Ghana in 2008; age/sex unknown due to missing data), 1 Stanleyville ST339 (yielded from Ghana; age/sex/year unknown due to missing data), 1 Virchow ST359 (from Ghana; age/sex/year unknown due to missing data), 3 Choleraesui ST145 (two isolates yielded from 1-year-old female infants in 2010 and 2011 and 1 from a 3-year-old female infant in 2012; all from Guinea-Bissau), 1 unknown ST2533 from Tanzania.

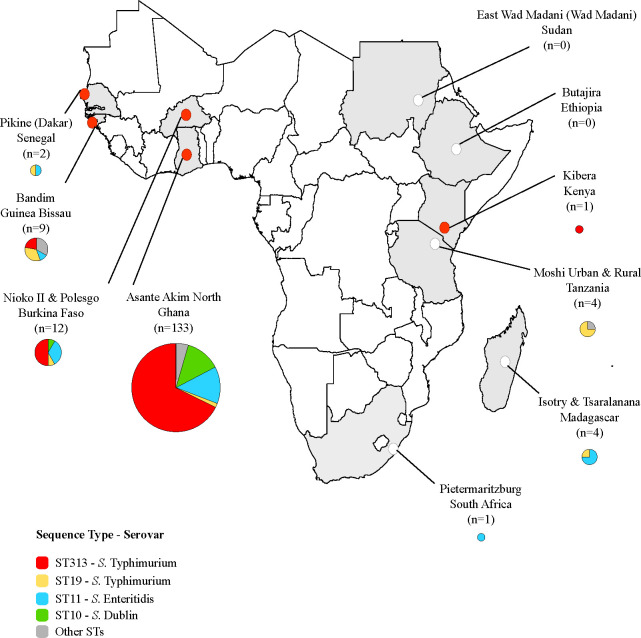

Overall, 61% (102/166) of the iNTS organisms described here were MDR. These were isolated in Burkina Faso (83%; 10/12), Ghana (66%, 88/133), Guinea-Bissau (22%; 2/9), Kenya (100%; 1/1) and Senegal (50%; 1/2). S. Typhimurium exhibited the highest prevalence of MDR (85%; 94/110); 95% (94/99) of the ST313 isolates were MDR. In total, 23% (7/30) of S. Enteritidis and 6% (1/18) S. Dublin organisms were MDR; none of the S. Typhimurium ST19 were MDR (figure 1, table 2).

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of iNTS genotypes and serotypes in the sampled countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Different colours in the pie charts correspond to different sequence types and serovars of iNTS isolates in our study sites. The size of the pie charts corresponds to the numbers of isolates in each country. Countries coloured in grey highlight the study sites, while red and white circles indicate countries with and without MDR iNTS isolates, respectively.

Table 2.

Distribution of MDR iNTS and gyrA mutation (fluoroquinolone resistance) in the sampled countries in sub-Saharan Africa

| Serovars (number of isolates) n=166 |

MDR iNTS isolates per serovar* | MDR iNTS serovar per country (%, number) |

MDR iNTS per genotype (%, number) |

| Typhimurium (n=110) | 85% (94/110) | Burkina Faso (50, 6/12) | ST313 (95, 94/99) |

| Ghana (64, 85/133) | ST19 (0, 0/11) | ||

| Guinea-Bissau (22, 2/9) | |||

| Kenya (100, 1/1) | |||

| Enteritidis (n=30) | 23% (7/30) | Burkina Faso (33, 4/12) | ST11 (25, 7/28) |

| Ghana (2, 2/133) | |||

| Senegal (50, 1/2) | |||

| Dublin (n=18) | 6% (1/18) | Ghana (1, 1/133) | ST10 (6, 1/18) |

| Others (n=8) | 0% (0/8) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Countries (number of iNTS) |

Number of MDR iNTS (n=102) | % of MDR iNTS | gyrA |

| Burkina Faso (n=12) | 10 | 10/12 (83) | 0 |

| Ghana (n=133) | 88 | 88/133 (66) | S83Y (ST313, 2 isolates) D87G (ST11, 6 isolates) D87Y (ST11, 2 isolates) D87N (ST11, 3 isolates) |

| Guinea-Bissau (n=9) | 2 | 2/9 (22) | 0 |

| Kenya (n=1) | 1 | 1/1 (100) | 0 |

| Senegal (n=2) | 1 | 1/2 (50) | 0 |

*Multidrug resistance (MDR) definition used for the analysis presence of resistant genes for at least one agent in all three antimicrobial categories listed below (detected in this study): ampicillin (blaCTX_M, blaOXA, blaTEM), chloramphenicol (catA1), trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (sulfonamide (sul1, sul2) and trimethoprim (dfrA, dfrA1, dfrA14, dfrA8)).

†Refer to table 1 for the number of iNTS isolates per country used as a denominator to calculate the % of MDR per country in this table.

‡The 2 MDR iNTS isolates with gyrA mutation (fluoroquinolone resistance) were yielded from a 1-year-old female infant and a 10-month-old female infant in Agogo in 2011 (TSAP: Typhoid Fever Surveillance Program).

§Spv locus was detected in all MDR iNTS isolates.

n.a., not available.

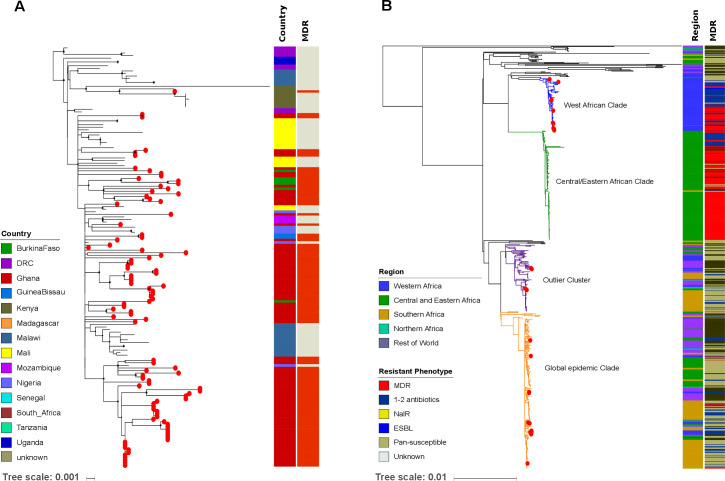

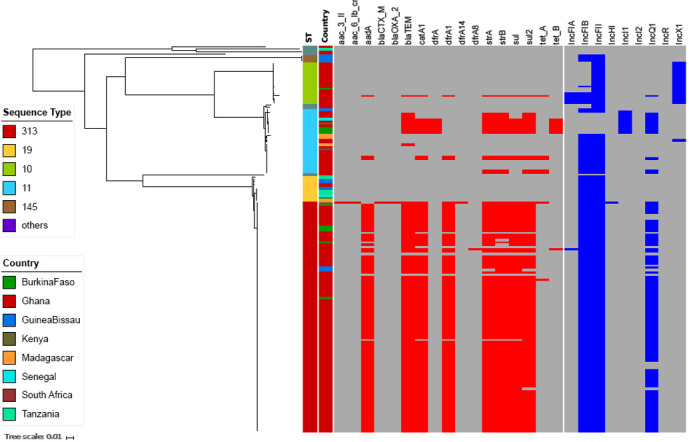

Phylogenetics and AMR of iNTS

A phylogenetic reconstruction of all iNTS isolates showed that the three major serovar STs—S. Typhimurium (ST313), S. Enteritidis (ST11) and S. Dublin (ST10)—formed independent clusters with dissimilar AMR gene profiles (figure 2). Almost all of the MDR S. Typhimurium ST313 (95%; 94/99) carried the Tn21 transposon-associated MDR-loci (sulII-strAB-dfrA1-aadA1-sulI-cat-blaTEM) on an IncF virulence-resistance plasmid (pSLT-BT).11 A single MDR S. Typhimurium ST313 from Kenya additionally carried two copies of blaCTX-M-15, conferring resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. One copy of blaCTX-M-15 was located on the 300 kb IncHI2 plasmid, pKST313 (accession number: LN794248), and the other on the chromosome disrupting the ompD locus. Reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones in S. Typhimurium ST313 was uncommon, with 2% (2/99) of Ghanaian ST313 isolates possessing a single mutation (S87Y) in gyrA (table 2).

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial resistance genes and plasmids associated with iNTS isolates circulating in sampled sub-Saharan African countries. Midpoint-rooted maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the core genes of iNTS isolates sequenced in this study and their corresponding metadata. The first column shows the sequence types in different colours. The second column corresponds to the countries where our iNTS isolates were detected. The remaining columns exhibit a heatmap of detected AMR genes and plasmid replicons. The tree scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per variable site.

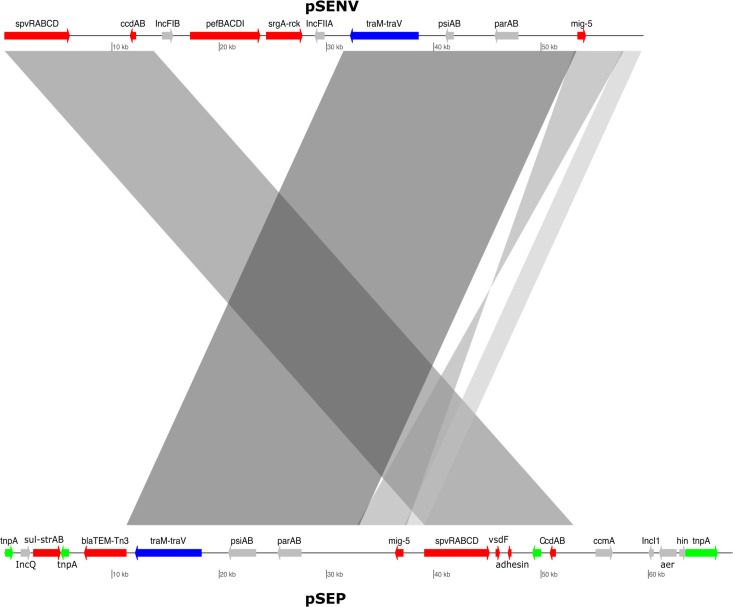

The majority of S. Enteritidis ST11 (19/28; 68%) harboured the typical IncF virulence plasmid (60 kb), which was comparable with pSENV (accession number NC_019120.1, coverage 100%, identity 99%). The remaining S. Enteritidis ST11 (9/28; 32%) harboured a novel IncI1 virulence-resistance plasmid (pSEP, accession number: ERP121368) of approximately 68 kb (figure 3), of which 7/28 (25%) isolates (4 from Burkina Faso, 2 from Ghana, 1 from Senegal) carried the MDR-encoding Tn21-like transposon (sulII-strAB-tetB-dfrA1-sulI-cat-blaTEM), and 2/28 (7.1%) isolates carried a different AMR cassette (TnpA-sulII-strAB-blaTEM-Tn3). The novel IncI plasmid exhibited 60% homology to pSENV but did not harbour the IncF replicon, the pefBACD fimbriae-encoding operon, or the virulence-associated genes srgA and rck (figure 3). In addition, two non-MDR Ghanaian S. Enteritidis ST11 possessed an AMR cassette (sul2-strAB-tetA) carried on a small (11 kb) non-conjugative IncQ plasmid conferring resistance against sulfonamides, streptomycin and tetracyclines. This IncQ plasmid exhibited a similar genetic structure to pSTU288-2 from S. Typhimurium (accession number CP004059.1, coverage 98%, identity 99%). Two further non-MDR Ghanaian isolates carried a Tn21-mediated AMR cassette (sulII-strAB-dfrA1-aadA1-sulI-cat) on the virulence plasmid, and a single non-MDR isolate from Madagascar carried a blaTEM Tn3 integrated into the virulence plasmid. Reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones was predicted by the sequences in 39% (11/28) of the S. Enteritidis-ST11, all of which originated from Ghana and displayed a variety of gyrA mutations (D87G: 6 isolates, D87N: 3 isolates, D87Y: 2 isolates) (table 2).

Figure 3.

Novel IncI1 virulence-resistance plasmid (pSEP) in an S. Enteritidis ST11 isolate. Plasmid comparison analyses between the novel virulence-resistance IncI1 plasmid pSEP (bottom) and the reference virulence IncF plasmid pSENV (top). The grey blocks show the BLASTn comparison between the two plasmids using the bl2seq feature from the web-based BLAST. Some annotations are added for both plasmids. Red-coloured arrows are genes associated with virulence and AMR. Blue-coloured arrows are genes associated with conjugation. Grey-coloured arrows correspond to plasmid replication and stability. Green-coloured genes are associated with transposon elements.

Phylogenetics of S. Typhimurium ST313 and S. Enteritidis ST11 isolates in global context

To investigate the population structures of S. Typhimurium ST313 and S. Enteritidis ST11 in a broader context, we constructed global phylogenies. All S. Typhimurium ST313 isolates from our study fell into lineage II (figure 4A). The single Kenyan ST313 isolate carrying two copies of blaCTX-M-15 was part of the previously described clonal expansion of MDR ceftriaxone-resistant ST313 sub-lineage.14 Notably, the Ghanaian ST313 isolates did not form a single cluster, but were associated with multiple clusters from Mali, Burkina Faso and Nigeria, indicating multiple introduction events (figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetics of S. Typhimurium ST313 lineage II and S. Enteritidis ST11 in sub-Saharan Africa. (A) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of S. Typhimurium-ST313 lineage II isolates from this study in the context of the sub-Saharan African continent; lineage I was pruned to enhance the visualisation of the tree. Red circles at the terminal leaves correspond to our study isolates. The first column shows different colour-coded countries from where all analysed isolates originate. The second column shows MDR and non-MDR isolates in red and grey, respectively. (B) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of our S. Enteritidis-ST11 isolates in the global context of S. Enteritidis. Red circles at the terminal leaves correspond to our study isolates. The first and second columns show regions and resistant phenotypes in different colours. The tree scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per variable site.

A detailed phylogenetic investigation of S. Enteritidis ST11 demonstrated that 11/28 (40%) (Ghana: 5, Burkina Faso: 4, Senegal: 1, Guinea Bissau: 1) isolates fell into the West African clade.13 The ST11 organisms within this West African clade displayed either MDR (seven isolates) or other non-MDR AMR phenotypes (two isolates). We found evidence that some Ghanaian isolates within this clade clustered alongside organisms from Burkina Faso and Mali, again suggesting international transmission. In addition, 13/28 (46%) of the S. Enteritidis ST11 (Ghana: 11, Madagascar: 1, South Africa: 1) belonged to the Global epidemic clade.13 These isolates had phylogenetic links with their country-specific clusters, with the exception of two Ghanaian isolates that clustered with organisms from neighbouring Cameroon and Senegal. Lastly, 4/28 (14%) (2 from Ghana, 2 from Madagascar) of the ST11 isolates grouped within the outlier cluster (figure 4B).

Incidence of MDR iNTS disease in sub-Saharan Africa

We calculated the age-stratified incidence rates of MDR iNTS in previously described study catchment areas in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau and Kenya (table 3). The adjusted incidence of MDR iNTS disease exceeded 100/100 000 PYO in children <15 years of age in all West African countries: Burkina Faso (Nioko II, 274/100 000 PYO, 95% CI 185 to 406; Polesgo, 255/100 000 PYO, 95% CI 138 to 470), Ghana (Asante Akim North: Ghana-AAN, 414/100 000, 95% CI 333 to 515) and Guinea-Bissau (Bandim, 105/100 000, 95% CI 69 to 161). Among children <15 years, younger children (<2–4 years) exhibited the highest MDR iNTS incidence rates in both sites in Burkina Faso: 753/100 000 PYO (95% CI 460 to 1233) in Nioko II and 630/100 000 PYO (95% CI 288 to 1380) in Polesgo. In both settings in Burkina Faso, the incidence of MDR iNTS disease in the infant age group was slightly lower than in the group aged 2–4 years, but children <5 years old exhibited a high burden of MDR iNTS disease. In Ghana-AAN, infants aged <2 years had the highest incidence of MDR iNTS disease (1435/100 000; 95% CI 1110 to 1854) followed by children aged between 2 and 5 years (747/100 000; 95% CI 491 to 1135). Similarly, in Guinea-Bissau, infants <2 years old exhibited the highest incidence of MDR iNTS disease (291/100 000; 95% CI 176 to 482). The incidence rate of MDR iNTS in older age groups (≥15 years) was relatively low, ranging between 0 (Guinea-Bissau) to 11 (Kenya) and 54 (Burkina Faso) per 100 000 PYO.

Table 3.

Incidence estimates of MDR iNTS disease in sub-Saharan Africa

| Country* | Age group in years | PYO estimation† | Recruitment proportion† | Genome-sequenced iNTS cases | Crude MDR iNTS cases | Crude MDR iNTS incidence per 100 000 PYO | Adjusted MDR iNTS cases | Adjusted MDR iNTS incidence per 100 000 PYO (95% CI)‡ |

|||

| Proportion of catchment population visiting study facility in case of fever (95% CI) | Catchment population | Catchment population adjusted by health-seeking behaviour | PYO | ||||||||

| Burkina Faso | |||||||||||

| Nioko II | 0–1 | 81% (74 to 88) | 2208 | 1788 | 2097 | 247/1297 (19) | 2 | 1 | 48 | 5 | 251 (107 to 590) |

| 2–4 | 81% (75 to 86) | 1823 | 1477 | 2097 | 235/1259 (19) | 3 | 3 | 143 | 16 | 753 (460 to 1233) | |

| 5–14 | 81% (78 to 84) | 4295 | 3479 | 4889 | 228/889 (26) | 2 | 1 | 20 | 4 | 79 (29 to 214) | |

| <15 | n.a. | 8326 | 6744 | 9083 | n.a. | 7 | 5 | 55 | 25 | 274 (185 to 406) | |

| ≥15 | 81% (79 to 83) | 9428 | 7637 | 10 676 | 208/759 (27) | 1 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 35 (13 to 96) | |

| All | n.a. | 17 754 | 14 381 | 19 759 | n.a. | 8 | 6 | 30 | 29 | 145 (100 to 209) | |

| Polesgo | 0–1 | 92% (86 to 99) | 896 | 824 | 929 | 117/475 (25) | 1 | 1 | 108 | 4 | 431 (162 to 1147) |

| 2–4 | 83% (76 to 89) | 856 | 710 | 992 | 148/466 (32) | 2 | 2 | 202 | 6 | 630 (288 to 1380) | |

| 5–14 | 87% (83 to 91) | 1734 | 1509 | 2104 | 252/510 (49) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| <15 | n.a. | 3486 | 3043 | 4025 | n.a. | 3 | 3 | 75 | 10 | 255 (138 to 470) | |

| ≥15 | 87% (84 to 89) | 4088 | 3557 | 4917 | 239/629 (38) | 1 | 1 | 20 | 3 | 54 (16 to 179) | |

| All | n.a. | 7574 | 6600 | 8942 | n.a. | 4 | 4 | 45 | 13 | 144 (83 to 249) | |

| Ghana§ | |||||||||||

| AAN | 0–1 | 16% (14 to 18) | 11 222 | 1760 | 4080 | 41 | 88 | 24 | 588 | 59 | 1435 (1110 to 1854) |

| 2–4 | 16% (13 to 18) | 8086 | 1268 | 2940 | 41 | 23 | 9 | 306 | 22 | 747 (491 to 1135) | |

| 0–4 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 111 | 33 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| 5–14 | 16% (15 to 17) | 34 439 | 5415 | 12 554 | 623/1657 (38) | 6 | 6 | 48 | 16 | 126 (77 to 206) | |

| <15 | n.a. | 53 747 | 8443 | 19 574 | n.a. | 117 | 39 | 147 | 81 | 414 (333 to 515) | |

| ≥15 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 16 | 10 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| All_TSAP | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 133 | 49 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Non_TSAP¶ | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 49 | 39 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| All | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a | n.a. | 182 | 88 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Guinea-Bissau | |||||||||||

| Bandim | 0–1 | 46% (39 to 54) | 10 852 | 4992 | 5198 | 206/631 (33) | 7 | 2 | 96 | 15 | 291 (176 to 482) |

| 2–4 | 43% (37 to 48) | 7307 | 3142 | 3866 | 175/359 (49) | 1 | 0 | 26 | 2 | 53 (13 to 208) | |

| 5–14 | 42% (41 to 48) | 19 905 | 8360 | 11 101 | 187/380 (49) | 1 | 0 | 18 | 4 | 37 (14 to 97) | |

| <15 | n.a. | 38 064 | 16 494 | 20 165 | n.a. | 9 | 2 | 40 | 21 | 105 (69 to 161) | |

| ≥15 | 45% (43 to 47) | 62 694 | 28 212 | 37 109 | 105/163 (64%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| All | n.a. | 100 758 | 44 706 | 57 274 | n.a. | 9 | 2 | 14 | 21 | 37 (24 to 57) | |

| Kenya | |||||||||||

| Kibera | 0–1 | 42% (38 to 47) | 3467 | 1456 | 2031 | 99/99 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2–4 | 39% (36 to 43) | 3070 | 1197 | 2039 | 312/312 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5–14 | 43% (39 to 47) | 7514 | 3231 | 5722 | 539/539 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| <15 | n.a. | 14 051 | 5884 | 9792 | n.a. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ≥15 | 35% (32 to 38) | 15 263 | 5342 | 9228 | 301/301 (100) | 1 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 11 (2 to 77) | |

| All | n.a. | 29 314 | 11 227 | 19 020 | n.a. | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 (1 to 37) | |

| Senegal** | |||||||||||

| Pikine | 0–1 | 39% (32 to 46) | 20 120 | 7837 | 11 194 | n.a. | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2–4 | 37% (33 to 41) | 30 180 | 11 097 | 15 851 | n.a. | 1 | 1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| 5–14 | 31% (28 to 34) | 96 152 | 29 807 | 42 577 | n.a. | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| <15 | n.a. | 146 452 | 48 741 | 69 623 | n.a. | 1 | 1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| ≥15 | 30% (28 to 31) | 195 726 | 58 718 | 83 874 | n.a. | 1 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| All | n.a. | 342 178 | 107 459 | 153 496 | n.a. | 2 | 1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

*TSAP was performed in 10 countries, of which 8 countries (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Madagascar, Senegal, South Africa and Tanzania in alphabetical order) exhibited positive iNTS isolates confirmed via whole genome sequencing. MDR iNTS were found in 5/8 countries presented in this table. No MDR iNTS were detected via whole genome sequencing from the isolates yielded from Madagascar, South Africa and Tanzania.

†PYO estimation methodologies have been published in detail in the TSAP typhoid burden paper (Marks et al, Lancet Global Health, 2017).

‡Adjusted MDR iNTS incidence per 100 000 PYO (95% CI): adjustments for case recruitment and error factors.

§Ghana samples included in this estimation of MDR iNTS are from the TSAP only.

¶Non-TSAP includes other fever surveillance performed in Agogo (‘IsolateAgogo’, ‘FISA’ and ‘zTYSA’). Refer to the Methods section.

**Adjusted MDR incidence of iNTS per 100 000 PYO could not be estimated for the study site in Senegal due to unavailable data on the recruitment proportion. The one MDR iNTS patient confirmed and presented in this table (crude MDR iNTS case) was a male infant aged 17 months, infected in 2012 with S. Enteritidis ST11. The one non-MDR iNTS patient presented in this table (genome-sequenced iNTS case) was a male adult aged 66 years, infected in 2012 with S. Typhimurium.

n.a., not available; PYO, person-years-of-observation.

Table 4.

All iNTS organisms analysed

| All iNTS isolates from TSAP† and non-TSAP projects‡ in Ghana (N=166) | ||||||||

| iNTS isolates analysed (N=945) | Burkina Faso | Ghana§ | Guinea-Bissau | Kenya | Madagascar | Senegal | South Africa | Tanzania |

| 12 | 133 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| 4 (Polesgo) 8 (Nioko II) |

84 (Asante Akim North) 49 (Agogo)¶ 36 (‘IsolateAgogo’) 5 (‘FISA’) 3 (‘TYSA’) 5 (unidentified) |

6 (Simao Hospital) 2 (Bandim) 1 (Belem) |

1 (Kibera) | 3 (CHU Tsaralalana) 1 (Isotry) |

1 (IPS) 1 (Dominique hospital) |

2 (Moshi urban) 1 (Moshi rural) 1 (Moshi other) |

||

| Published iNTS Typhimurium ST313 Lineage II isolates (N=102)** | ||||||||

| DRC†† | Kenya | Malawi | Mali | Mozambique | Nigeria | Uganda | ||

| 8 | 9 | 55 | 18 | 3 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Published iNTS Enteritidis ST11 isolates (N=677)‡‡ | ||||||||

| Western Africa | Central and Eastern Africa | Southern Africa | Northern Africa | Rest of the World | ||||

| 90 | 262 | 131 | 11 | 183 | ||||

*Total 945 iNTS organisms were analysed in this manuscript: 166 iNTS isolates from the TSAP and other Ghana projects; sequenced and published 102 iNTS serovar Typhimurium ST313 Lineage II isolates from seven countries (DRC/Kenya/Malawi/Mali/Mozambique/Nigeria/Uganda); and sequenced and published 594 (out of 677) iNTS serovar Enteritidis ST11 isolates (see online appendices for the metadata).

†TSAP: Typhoid Fever Surveillance Program.7 30 Of the 10 countries under the TSAP, no iNTS was found in Sudan and Ethiopia. 4 and 1 iNTS strains were identified from Madagascar and South Africa, respectively, through the whole genome sequencing; no iNTS isolates were reported from Madagascar and South Africa based on the blood culture result. Few analysed iNTS isolates, which may have been detected outside the strictly predefined surveillance catchment area, are considered for the bacterial genomic analysis, but excluded from the incidence estimation of the multidrug resistant iNTS in respective sites in table 4. The 166 iNTS isolates included for the final genomic analyses are based on the screening of whole genome sequenced results.

‡Non-TSAP projects in Ghana include the ‘Febrile Illnesses Surveillance in Africa (FISA)’, ‘Typhoid Surveillance in Africa (TYSA)’ and ‘IsolateAgogo’ conducted in Agogo.

§Ghana: 133 iNTS isolates analysed in this manuscript include 84 iNTS detected through the TSAP in Asante Akim North and 49 iNTS from several non-TSAP projects conducted in Agogo.

¶49 (Agogo): 49 iNTS isolates detected from various non-TSAP projects in Agogo, Ghana as listed in this table.

**Total 102 iNTS Typhimurium ST313 Lineage II isolates, which had been collected in seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa and whole genome sequenced, were published and raw sequence data accessible at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Global collection of S. Typhimurium and additional S. Typhimurium from Malawi, Kenya, Mozambique, Uganda, DRC, Nigeria and Mali11; Nigeria and DRC12; Malawi28; Kenya (Kariuki et al 2015b); Malawi.32 Whole genome sequenced 166 iNTS isolates from TSAP and non-TSAP projects in Ghana listed in this table included 99 iNTS Typhimurium ST313 Lineage II. This 99 ST313 Lineage II was combined with the raw sequence data of 102 ST313 Lineage II published isolates listed in this footnote. Total 201 ST313 Lineage II isolates were further analysed.

††DRC: Democratic Republic of Congo.

‡‡Raw sequence data of the published global collection of 594/677 S. Enteritidis isolated from human and animal samples (Feasey et al 2016) were accessible at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. The associated metadata were publicly available online. These samples were collected and whole genome sequenced across the African continent and the world: Western Africa: Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger and Senegal. Central and Eastern Africa: Central African Republic, Comoros, Congo, Djibouti, Ethiopia, HPA, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda and Uganda. Southern Africa: Republic of South Africa. Northern Africa: Algeria, Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia. Rest of the World: Angola, Argentina, Colombia, Germany, Italy, Japan, PTG, Ratin-manufactured rat poison, Slovakia, Spain, Thailand, UK, Uruguay, USA and unknown.

Discussion

Our study shows that MDR iNTS is highly prevalent in several sub-Saharan African countries. Specifically, we found that MDR S. Typhimurium ST313 is the most common cause of iNTS disease, but that other iNTS serovars, principally S. Enteritidis ST11 and S. Dublin ST10 in West Africa, also constitute a major proportion of the disease burden.52 53 Our phylogenetic analyses provide further evidence for the regional transmission of two MDR serovars/STs (S. Typhimurium ST313 and S. Enteritidis ST11) between Ghana and neighbouring countries Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Mali and Senegal. These transmission events highlight the need for intensified AMR surveillance, the coordination of AMR reporting, and sustained public health control measures between these and other African countries.

We calculated a particularly high incidence of MDR iNTS disease in the West African countries of Burkina Faso, Ghana (<5 years) and Guinea-Bissau (<2 years). The incidence rates of MDR iNTS disease presented here generally correspond with the incidence of iNTS disease in other African countries.7 Effective antimicrobial therapy is an essential component of iNTS management; however, the effectiveness of first-line treatments has been diminished due to the emergence and spread of MDR and XDR NTS strains.13 29 54 Our data also depict the emergence of reduced fluoroquinolones susceptibility in both MDR ST313 and ST11 in Ghana, as well as the circulation of a ceftriaxone-resistant ST313 sub-lineage in Kenya. Invasive Salmonella with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin have been reported in Burkina Faso,7 Ghana,7 21 Nigeria,55 Senegal,56 Mozambique,23 the Congo,29 57 Kenya58 and South Africa.59 This increasing trend in resistance against clinically important classes of antimicrobials in differing iNTS serovars across Africa is of major concern.14 The growing use of ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin for the treatment of febrile illnesses in Africa may lead to an increase in of MDR and XDR pathogens in this continent, which has already been observed across Asia in the last two decades.

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting and generalising these data beyond our study sites. While we are able to illustrate the magnitude of the problem of MDR iNTS in West Africa, there are relatively few genomic data points available from countries in East and Southern Africa. Previous studies showed high prevalence of MDR iNTS disease in Kenya27 58 and a recent meta-analysis suggested that MDR iNTS has emerged across four regions of sub-Saharan Africa.60 The generation and analysis of additional epidemiological and genomic iNTS data in Eastern/Southern Africa would help facilitate comparison of incidence rates and AMR profiles of iNTS-associated organisms between African regions. Further, the estimated incidence rates of MDR iNTS disease in our study should be interpreted with caution as the number of cases in some countries were relatively small. In parallel, the original study design may also have led to some underestimation of iNTS burden, as afebrile patients with other clinical symptoms associated with iNTS disease were not enrolled. As a result, the true incidence of MDR iNTS disease in some settings need to be further monitored with more systematic disease surveillance.

Despite the identified limitations, our study provides enhanced insights into the population structure and transmission dynamics of major MDR iNTS serovars in sub-Saharan Africa and identified countries with a high burden of MDR iNTS. There is an urgent need to expand clinical and genomic surveillance for pathogens causing bloodstream infections across continental Africa to improve our understanding of disease incidence and to monitor AMR trends. Such data can better inform antimicrobial stewardship to extend the life of existing antimicrobial therapies and prioritisation of preventative interventions including vaccines. The development and deployment of a safe, low-cost, highly efficacious multivalent vaccine should be prioritised for the management and prevention of iNTS disease in Africa, particularly in countries with high prevalence of MDR iNTS infections, as well as HIV, malaria and malnutrition.61 62 Meanwhile, further investigations of household transmission dynamics and human and non-human reservoirs of infection are warranted to inform better iNTS control measures and, ultimately, optimal programmatic use of future vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank all staff and partners involved in obtaining and processing the data and samples including healthcare facility and laboratory staff at the TSAP network countries. We also thank the WTSI Pathogen Informatics team for help with whole genome sequencing.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @DrSeEunPark, @DuyPham_Oucru, @meganecarey

SEP and DTP contributed equally.

Contributors: Conceiving and designed experiments: SEP, GD, SB, FM. Performed experiments: SEP, DTP. Analysed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysing tools: SEP, DTP, GDP, UP, LMCE, VvK, JI, ODM, HSG, JAP, RFB, YAS, EOD, RR, ABS, AA, NG, AS, KHK, JM, PA, HMB, JTH, JMM, LC, BO, BF, NS, TJLR, TMR, LPK, ES, MT, BY, MAET, RK, DMD, AJ, AT, AN, MBA, SVL, JFD, JKP, FK, MEC, SVP, MA, JDC, GD, SB, FM. Funding acquisition: GD, FM. Writing original draft: SEP. Writing review and editing: SEP, DTP, SB, FM.

Funding: This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant: OPPGH5231). The findings and conclusions are our own and do not necessarily reflect positions of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation or the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The International Vaccine Institute acknowledges its donors, including the Government of Republic of Korea and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). Research infrastructure at the Moshi site was supported by the US National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01TW009237; U01 AI062563; R24 TW007988; D43 PA-03-018; U01 AI069484; U01 AI067854; P30 AI064518), and by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [grant number BB/J010367]. Stephen Baker is supported by a Wellcome senior research fellowship (215515/Z/19/Z). DTP is funded as a leadership fellow through the Oak Foundation [grant number OCAY-15-547].

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Raw sequence data are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (Project number: ERP009684, ERP010763, ERP013866).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Morpeth SC, Ramadhani HO, Crump JA. Invasive non-typhi Salmonella disease in Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:606–11. 10.1086/603553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. The Lancet 2012;379:2489–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ao TT, Feasey NA, Gordon MA, et al. Global burden of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease, 2010(1). Emerg Infect Dis 2015;21:941–9. 10.3201/eid2106.140999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon MA. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease – epidemiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012;24:484–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enwere G, Biney E, Cheung YB, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of community-acquired invasive bacterial infections in children aged 2–29 months in the Gambia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006;25:700–5. 10.1097/01.inf.0000226839.30925.a5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkley JA, Lowe BS, Mwangi I, et al. Bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Kenya. N Engl J Med 2005;352:39–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa040275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks F, von Kalckreuth V, Aaby P, et al. Incidence of invasive Salmonella disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicentre population-based surveillance study. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e310–23. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30022-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feasey NA, Archer BN, Heyderman RS, et al. Typhoid fever and invasive nontyphoid salmonellosis, Malawi and South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16:1448–51. 10.3201/eid1609.100125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyene G, Nair S, Asrat D, et al. Multidrug resistant Salmonella Concord is a major cause of salmonellosis in children in Ethiopia. J Infect Dev Ctries 2011;5:023–33. 10.3855/jidc.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tennant SM, Diallo S, Levy H, et al. Identification by PCR of non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica serovars associated with invasive infections among febrile patients in Mali. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010;4:e621. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okoro CK, Kingsley RA, Connor TR, et al. Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Genet 2012;44:1215–21. Available at http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/ng.2423 10.1038/ng.2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leekitcharoenphon P, Friis C, Zankari E, et al. Genomics of an emerging clone of Salmonella serovar typhimurium ST313 from Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Infect Dev Ctries 2013;7:696–706. 10.3855/jidc.3328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feasey NA, Hadfield J, Keddy KH, et al. Distinct Salmonella enteritidis lineages associated with enterocolitis in high-income settings and invasive disease in low-income settings. Nat Genet 2016;48:1211–7. 10.1038/ng.3644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kariuki S, Gordon MA, Feasey N, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and management of invasive Salmonella disease. Vaccine 2015;33:C21–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musicha P, Cornick JE, Bar-Zeev N, et al. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in bloodstream infection isolates at a large urban hospital in Malawi (1998–2016): a surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:1042–52. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30394-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molyneux EM, Mankhambo LA, Phiri A, et al. The outcome of non-typhoidal Salmonella meningitis in Malawian children, 1997–2006. Ann Trop Paediatr 2009;29:13–22. 10.1179/146532809X401980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a GM, Graham SM, Walsh AL. Epidemics of invasive Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis and S. enterica serovar typhimurium infection associated with multidrug resistance among adults and children in Malawi. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:963–9. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18444810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kariuki S, Okoro C, Kiiru J, et al. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium sequence type 313 from Kenyan patients is associated with the bla CTX-M-15gene on a novel IncHI2 Plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;59:3133–9. 10.1128/AAC.00078-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oneko M, Kariuki S, Muturi-Kioi V, et al. Emergence of community-acquired, multidrug-resistant invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease in rural Western Kenya, 2009–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:S310–6. 10.1093/cid/civ674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akullian A, Montgomery JM, John-Stewart G, et al. Multi-drug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella associated with invasive disease in Western Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018;12:e0006156. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen MV, Sarpong N, Krumkamp R, et al. Incidence and characteristics of bacteremia among children in rural Ghana. PLoS One 2012;7:e44063. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalonji LM, Post A, Phoba M-F, et al. Invasive Salmonella infections at multiple surveillance sites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2011–2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:S346–53. 10.1093/cid/civ713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandomando Inácio, Jaintilal D, Pons MJ, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility and mechanisms of resistance in Shigella and Salmonella isolates from children under five years of age with diarrhea in rural Mozambique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:2450–4. 10.1128/AAC.01282-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sigaúque B, Roca A, Mandomando I, et al. Community-acquired bacteremia among children admitted to a rural hospital in Mozambique. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28:108–13. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318187a87d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blomberg B, Manji KP, Urassa WK, et al. Antimicrobial resistance predicts death in Tanzanian children with bloodstream infections: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2007;7:43. 10.1186/1471-2334-7-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obaro SK, Hassan-Hanga F, Olateju EK, et al. Salmonella bacteremia among children in central and northwest Nigeria, 2008–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61 Suppl 4:S325–31. 10.1093/cid/civ745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kariuki S, Mbae C, Van Puyvelde S, et al. High relatedness of invasive multi-drug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella genotypes among patients and asymptomatic carriers in endemic informal settlements in Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020;14:e0008440. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feasey NA, Cain AK, Msefula CL, et al. Drug resistance in Salmonella enterica ser. typhimurium bloodstream infection, Malawi. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20:1957–9. 10.3201/eid2011.141175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Puyvelde S, Pickard D, Vandelannoote K, et al. An African Salmonella typhimurium ST313 sublineage with extensive drug-resistance and signatures of host adaptation. Nat Commun 2019;10:1–12. Available at. 10.1038/s41467-019-11844-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Kalckreuth V, Konings F, Aaby P, et al. The typhoid fever surveillance in Africa program (TSAP): clinical, diagnostic, and epidemiological methodologies. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:S9–16. 10.1093/cid/civ693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frickmann H, Dekker D, Boahen K, et al. Increased detection of invasive enteropathogenic bacteria in pre-incubated blood culture materials by real-time PCR in comparison with automated incubation in sub-Saharan Africa. Scand J Infect Dis 2013;45:616–22. 10.3109/00365548.2013.777777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Msefula CL, Kingsley RA, Gordon MA, et al. Genotypic homogeneity of multidrug resistant S. typhimurium infecting distinct adult and childhood susceptibility groups in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS One 2012;7:e42085. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 2008;18:821–9. 10.1101/gr.074492.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gladman S, Seemann T, optimiser V. Available: https://github.com/Victorian-Bioinformatics-Consortium/VelvetOptimiser.git

- 35.Page AJ, Taylor B, Delaney AJ, et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb Genom 2016;2:e000056. 10.1099/mgen.0.000056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014;30:2068–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015;31:3691–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009;25:2078–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol 2004;5:R12. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:e15. 10.1093/nar/gku1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014;30:1312–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 2007;23:127–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inouye M, Dashnow H, Raven L-A, et al. SRST2: rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med 2014;6:90. Available at http://genomemedicine.com/content/6/11/90 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta SK, Padmanabhan BR, Diene SM, et al. ARG-annot, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58:212–20. 10.1128/AAC.01310-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58:3895–903. 10.1128/AAC.02412-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res 2018;3:124. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Achtman M, Wain J, Weill F-X, et al. Multilocus sequence typing as a replacement for serotyping in Salmonella enterica. PLoS Pathog 2012;8:e1002776. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang S, Yin Y, Jones MB, et al. Salmonella serotype determination utilizing high-throughput genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53:1685–92. 10.1128/JCM.00323-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wick RR, Schultz MB, Zobel J, et al. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2015;31:3350–2. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol 2010;27:221–4. 10.1093/molbev/msp259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panzner U, Pak GD, Aaby P, et al. Utilization of healthcare in the typhoid fever surveillance in Africa program. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:S56–68. 10.1093/cid/civ891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sow AG, Wane AA, Diallo MH, et al. Genotypic characterization of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enteritidis isolates in Dakar, Senegal. J Infect Dev Ctries 2007;1:284–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keddy KH, Takuva S, Musekiwa A, et al. An association between decreasing incidence of invasive non-typhoidal salmonellosis and increased use of antiretroviral therapy, Gauteng Province, South Africa, 2003–2013. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173091. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, et al. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res 2009;19:2279–87. 10.1101/gr.091017.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akinyemi KO, Bamiro BS, Coker AO. Nigeria: incidence co-infection, patterns of antimicrobial resistance, and emergence of reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. J Heal Popul NUTR 2007;25:351–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harrois D, Breurec S, Seck A, et al. Prevalence and characterization of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing clinical Salmonella enterica isolates in Dakar, Senegal, from 1999 to 2009. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20:O109–16. 10.1111/1469-0691.12339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lunguya O, Lejon V, Phoba M-F, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in invasive non-typhoid Salmonella from the Democratic Republic of the Congo: emergence of decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility and extended-spectrum beta Lactamases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7:e2103. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kariuki S, Onsare RS. Epidemiology and genomics of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella infections in Kenya. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61 Suppl 4:S317–24. 10.1093/cid/civ711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keddy KH, Musekiwa A, Sooka A. Clinical and microbiological features of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella associated with HIV-infected patients, Gauteng Province, South Africa. Med 2017;96:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tack B, Vanaenrode J, Verbakel JY, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review on antimicrobial resistance and treatment. BMC Med 2020;18. 10.1186/s12916-020-01652-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piccini G, Montomoli E. Pathogenic signature of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella in Africa: implications for vaccine development. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020;16:2056–71. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1785791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kariuki S, Owusu-Dabo E. Research on invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease and developments towards better understanding of epidemiology, management, and control strategies. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:S127–9. 10.1093/cid/ciaa315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2021-005659supp001.pdf (550.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-005659supp002.pdf (63.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Raw sequence data are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (Project number: ERP009684, ERP010763, ERP013866).