Abstract

Accrediting bodies for Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm.D.) and postgraduate residency training programs recognize the importance of research and scholarship training. However, specific guidance on how research and scholarship fundamentals should be delivered to trainees have not been provided. As a result, competing priorities often create barriers for trainees to develop research and scholarship skills and limit the trainees’ ability to conduct and participate in high-quality, meaningful research experiences. The purpose of this “how-to” guide is to assist pharmacy school faculty and pharmacy residency program directors with strategies to overcome programmatic, trainee, and project barriers to providing a high-quality training experience in research and scholarship. Programmatic topics addressed include institutional support and program oversight, expertise and number of research mentors, incentives for mentor engagement, and competing priorities that diminish time for research activities. Trainee topics include lack of trainee interest in the assigned project, trainee departure prior to project completion, lack of knowledge of the publication process, and time constraints to work on the project. Project topics addressed include time needed to initiate a project, training on methodology relevant to a project, selection of projects that lack rigor, depth, or feasibility, and resource constraints to disseminate project results. A summary of specific recommended actions is provided to effectively overcome these common barriers encountered in research and scholarship training programs.

Keywords: pharmacy student, pharmacy residency, research, training

1. INTRODUCTION

Numerous pharmacy professional organizations emphasize the creation and dissemination of new knowledge to guide clinical decision-making and optimize medication use as critical for advancing the pharmacy profession.1–3 Ideally, pharmacists begin learning the fundamental skills of research and scholarship while enrolled in a Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm.D.) program and continue to develop them through postgraduate training programs. This sentiment aligns with the accreditation requirements for Pharm.D. programs and postgraduate residency training. Both the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) and the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) recognize the importance of research and encourage student engagement in faculty research programs.4,5 Related, the accreditation standards for residency programs through the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) have long highlighted the value and importance of scholarly pursuit during pharmacy residency training.6

While these accrediting bodies recognize the importance of research and scholarship in pharmacy training, neither ACPE nor ASHP have provided specific recommendations on how research and scholarship training should be delivered to trainees. Furthermore, neither body defines the type of project or deliverables that trainees should engage in during their program. Therefore, competing priorities in Pharm.D. curricula and postgraduate residency training programs often create barriers for trainees to develop research and scholarship skills and limit the trainee’s ability to conduct and participate in high-quality, meaningful research experiences.

Schools of pharmacy and pharmacy residency training programs offer a wide variety of research and scholarship training opportunities.7,8 Additionally, substantial variability in the quality and depth of research experiences for trainees and high rates of attrition before completing the research experience have been demonstrated within Pharm.D. programs.8 Previous studies have reported publication rates from Pharm.D. and pharmacy residency research projects at less than 15%.8–10 A previous ACCP commentary by Deal and colleagues, in addition to several other publications, highlight the programmatic and project barriers to providing trainees with a research opportunity of sufficient depth and quality to obtain fundamental skills during training.2,11,12

In recent years, there have been several examples of successful pharmacy research training opportunities published.13–16 Students in these programs reported an improved ability to work independently, evaluate literature, distinguish themselves from peers, and build faculty-student mentoring relationships in addition to these programs reporting a higher than average publication rate. Graduates of these programs have also reported improved problem-solving skills, better marketability, and more effective functioning in their careers.13 Ideally, honing research fundamentals during training will translate to increased scholarly productivity as faculty members and/or clinicians and allow the trainee to become an effective research mentor themselves.

Two such examples of research training programs are affiliated with our institution. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Eshelman School of Pharmacy underwent a curricular transformation and launched a new Pharm.D. curriculum in 2015.17 One of the four defining elements of the new curriculum was fostering scientific inquiry and innovation. To meet this goal, an elective Research and Scholarship in Pharmacy (RASP) pathway built around a longitudinal, faculty-mentored scholarly project was developed and implemented within the curriculum.18 Additionally, in 2013, the University of North Carolina Medical Center implemented the flipped residency research model within the pharmacy residency program.19 This model modified the residency research timeline to better align research activities with residents’ abilities at specific time points during the year.

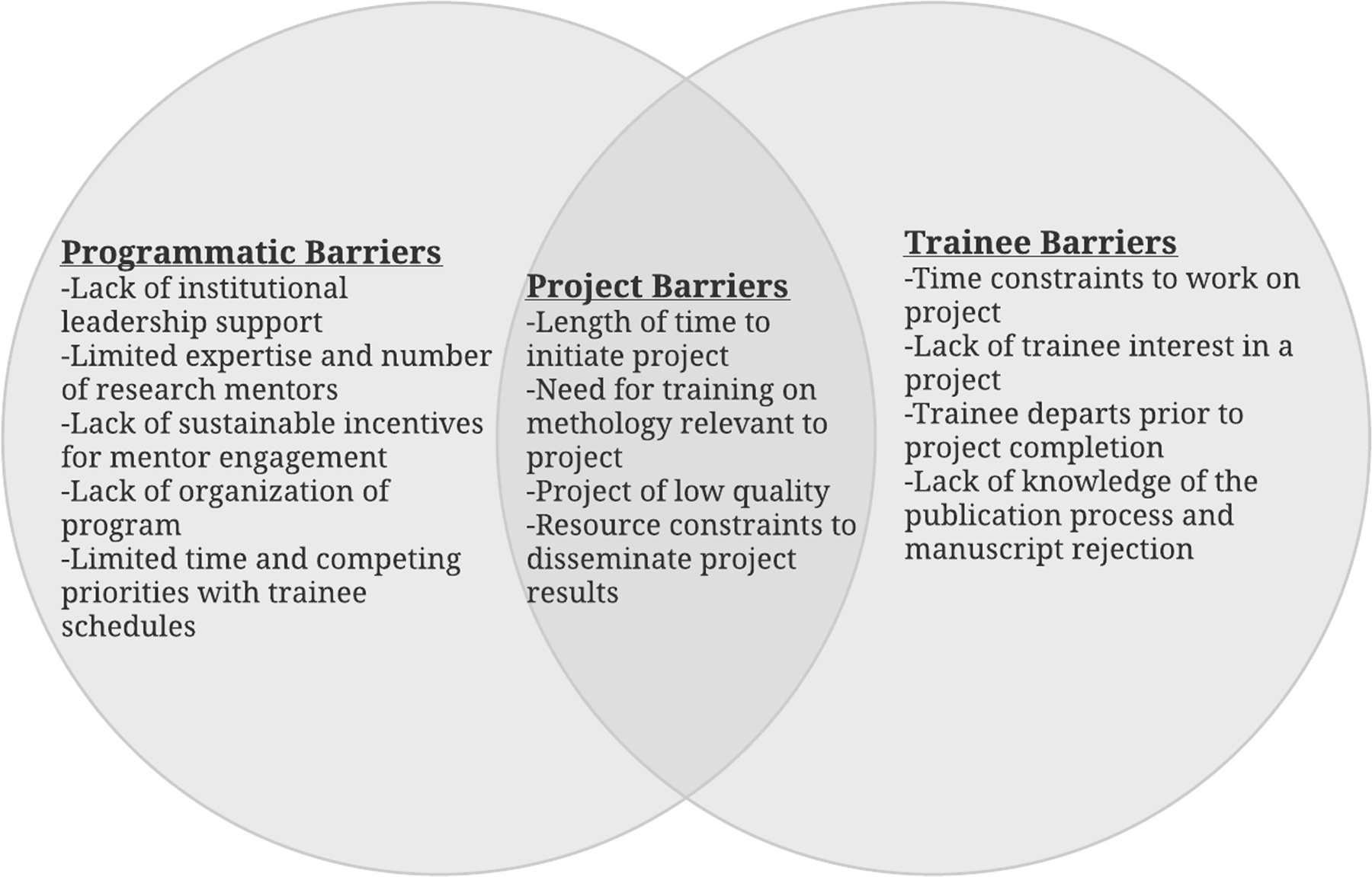

Although the importance of research and scholarship training is well-recognized, numerous barriers remain in operationalizing a quality experience for students and residents. These barriers can impede a high-quality training experience aimed at promoting skill development, creating opportunities for scholarship in the form of presentations and publications, and differentiating trainees when they apply for subsequent positions. Based on our experience with the design, implementation, and evaluation of these two programs, in addition to our review of other programs in the literature, we broadly divide barriers into three categories: programmatic, individual trainee, and research project (Figure 1).2,18,19 All three types of barriers can significantly hinder the potential to provide a high-quality research and scholarship training experience. The purpose of this “how-to” guide is to provide pharmacy school faculty and pharmacy residency program directors with strategies to overcome barriers to providing a high-quality training experience in research and scholarship. Tables 1, 2, and 3 provide specific recommendations that institutions can take to overcome barriers to research and scholarship training. These strategies were derived from those successfully employed at our own institutions and supported by literature published from programs implemented at other institutions.18,19

Figure 1.

Relationship between programmatic, individual trainee, and research project barriers in research and scholarship training.

Table 1.

Summary of Recommended Actions to Effectively Overcome Program Barriers in Research and Scholarship Training Programs

| Barrier | Recommended Actions to Overcome Barrier |

|---|---|

| Lack of institutional leadership support |

|

| Limited expertise and number of research mentors | |

| Lack of sustainable incentives for mentor engagement |

|

| Lack of organization of program |

|

| Limited time and competing priorities within trainee schedules |

Applies to both student and resident training programs.

Primarily applies to student training programs.

Primarily applies to resident training programs.

Table 2.

Summary of Recommended Actions to Effectively Overcome Individual Trainee Barriers in Research and Scholarship Training Programs

| Barrier | Strategies to Overcome Barrier |

|---|---|

| Time constraints to work on research project |

|

| Lack of trainee interest in a research project |

|

| Trainee departs prior to research project completion |

|

| Lack of knowledge of the publication process and manuscript rejection |

|

Applies to both student and resident training programs.

Primarily applies to student training programs.

Primarily applies to resident training programs.

Table 3.

Summary of Recommended Actions to Effectively Overcome Research Project Barriers in Research and Scholarship Training Programs

| Barrier | Strategies to Overcome Barrier |

|---|---|

| Length of time to initiate research project |

|

| Need for training on methodology relevant to research project, including statistical analysis training or support |

|

| Selection of research project that lacks rigor, depth, or feasibility |

|

| Resource constraints to complete research project and disseminate results |

|

Applies to both student and resident training programs

Primarily applies to student training programs

Primarily applies to resident training programs

IRB, Institutional Review Board

2. PROGRAMMATIC BARRIERS TO RESEARCH AND SCHOLARSHIP TRAINING

Described in this section are programmatic barriers, which refer to limitations or constraints of the training program. Please see Table 1 for a summary of specific actions that institutions can take to effectively overcome programmatic barriers to research and scholarship training, and whether each strategy is applicable to student training programs or residency training programs.

2.1. Lack of Support from Institutional Leadership

Institutional leadership support is critical to the success of student and resident research and scholarship training programs. Effective institutional support can result in incentivizing both learners and research mentors to participate in the program while also providing the personnel and resources required for successful program sustainability.

Some institutions have chosen to require a research experience for their trainees, which demonstrates the significance that the institution places on the development of those skills.9,15,20–22 However, it may not be feasible for every program to accommodate all of their trainees in research endeavors. This is particularly true for student training programs as the number of students within Pharm.D. programs is greater than the number of residents. Other reported ways that institutional leadership has demonstrated support includes communicating the value of the training experience to the institutional mission, providing administrative support to the training program, providing service credit for those who serve on the oversight committee, providing administrative days to practitioners who serve as research mentors, and providing teaching credit to faculty who serve as research mentors.18

2.2. Limited Expertise and Number of Research Mentors

The personnel needed to sustain a research and scholarship program for trainees can be challenging to maintain. The incentive and benefits for faculty to participate in a research mentoring role for trainees may not always be clear to the faculty member or explicitly acknowledged by the institution. Additionally, pharmacy residency programs that do not have a focus on research and scholarship due to departmental constraints or other priorities may not be able to adequately allocate the personnel necessary for continual research endeavors. This is not only with respect to idea generation and methodological design, but also with research committees to oversee the progress of projects.

Incorporating trainees into already existing research programs within the institution can lessen the burden on research mentors, as there is a clear benefit associated with mentoring the trainee. This may be more difficult for pharmacy residency programs as developing research programs may not be a priority for hospital practitioners and administrators. However, residency programs affiliated with universities have reported partnering with faculty to provide a robust research experience for the trainee.23 To alleviate a capacity issue, programs have also reported combining trainees together (e.g., team-based approach with 2–5 trainees per research mentor) on the same project in order to lessen the number of projects and research mentors needed in a given year.19,24 Programs might also consider having multiple trainees work together, including across sites, to increase the sample size and rigor of the project. In instances where trainees are working together on the same project, particularly across sites, it is important to note that very clear planning, timelines, and expectations (e.g., roles and responsibilities) should be established to ensure the project moves forward in a timely fashion.

One program described a process where two faculty members were assigned as research mentors, one experienced faculty member and a new faculty member.25 This provided a layered learning-type approach where the experienced faculty member mentored the trainee on the research project and also mentored the new faculty member on being a research mentor. While this may not be feasible for programs where Pharm.D. students are required to engage in a research experience, this type of approach ultimately increased the pool of potential research mentors, where the previously new faculty member became the experienced faculty mentor.25 A model with two research mentors also has enormous potential for collaborations between schools of pharmacy and health-systems where school-based faculty (i.e., experts in methodology and scholarship) can partner with health-system practitioners (i.e., experts in identifying relevant clinical problems and study populations) to effectively create a platform for research and scholarship that facilitates training opportunities for students and residents.23 Furthermore, cross-collaboration between non-affiliated institutions with researchers of common interests has the potential to provide additional resources, create a more robust experience, and increase the project scope and quality.

2.3. Lack of Sustainable Incentives for Mentor Engagement

Mentors may be unclear of what the incentives are for them to engage in the research and scholarship training program. For these training programs, it is important to flip the mindset from a program needing to develop new research projects to accommodate trainees to leveraging already existing research programs and existing or new institutional initiatives as the foundation for the program. Incorporating the trainee into the research mentor’s already existing research program provides the mentor access to trainees that can help advance the mentor’s research agenda. This incentivizes the mentor to participate while also advancing student/resident training. Leveraging existing programs and initiatives also opens new project avenues beyond hypothesis testing, such as quality improvement/assessment projects, institutional effectiveness, method development/validation, and predictive analytics.

Utilizing a layered learning approach that involves graduate students, fellows, residents, and Pharm.D. students also has the potential to lessen the burden of one individual (i.e., research mentor) being responsible for overseeing the research and scholarship training, while providing mentorship opportunities for more senior trainees. As not all institutions have access to trainees with multiple levels of research experience, this strategy can again serve as a stimulus for programs to foster cross-collaborations and increase the resource pool. Receiving teaching credit for faculty members, that is recognized and contributes towards promotion, reappointment, and/or tenure, or administrative days for practitioners by serving as research mentors, can provide additional incentive for involvement in the training program.18

2.4. Lack of Program Organization and Oversight

Pharm.D. and residency programs encourage research and scholarship but may not have the internal organization within the school or pharmacy department to ensure and sustain a robust research experience for trainees. In a previous review of capstone assessments in pharmacy education, several capstones involved the completion of a research project.26 A common reason found for discontinuation of the capstone at an institution was that the person overseeing the capstone left the institution and replacement personnel were not available.26 Additionally, with strong organization of the training program, many project-specific barriers can be prevented or alleviated before the trainee starts work on the project.

Several programs report the use of oversight committees to manage the organization of the program.18,19,27 The implementation of an oversight committee ensures the burden for overseeing and sustaining the training program does not fall on one individual. The risk for burnout is also lowered as the responsibilities are shared among a group of people.

In the Pharm.D. program setting, these committees are generally comprised of faculty and support staff, whereas pharmacy residency program committees are normally made up of practitioners and administrators in the department.18,19 Described roles of the committee include ensuring the projects are feasible and of appropriate scope for a trainee, providing oversight and feedback on the project timeline and deliverables, and supporting the trainee through the research process in conjunction with the project team. Several programs also describe having pre-determined check-ins with the trainee and mentor at various points throughout the research process to discuss progress made, provide feedback, and examine barriers the trainee or mentor may be encountering.18,19

Published research and scholarship training programs also highlight the importance of there being a built-in structure to the program. This varies from the programs being credit-bearing courses with specific assignments, deliverables, and class times to programs having timelines with research milestones to ensure the trainee is progressing at an appropriate pace.18,24,28–32 Several programs also reported the creation of a research training program handbook, which describe in detail the program process (e.g., registration information, advisor selection, reporting flow, deadlines, deliverables format, potential troubleshooting) and content (e.g., goals, objectives, overall description, proposal writing tips, recommended readings).33

Utilizing best practices in course design (e.g., backward design with well-defined objectives and deliverables formulated first) can also promote quality of learning, rigor, and alignment across research fundamentals taught through a project-based approach.34 For example, the University of North Carolina (UNC) Eshelman School of Pharmacy RASP pathway was developed via a reverse-engineering design approach.18 Guiding principles that aligned with an overarching guiding principle of the Pharm.D. curriculum were created and endorsed by School leadership prior to implementation of the program. The RASP oversight committee then built its program curriculum around standardized project objectives, deliverables, and assessments.18 This structure resulted in positive student perceptions regarding the value and satisfaction of RASP and scholarly productivity in the form of nationally presented posters and published abstracts and original research manuscripts.18

2.5. Limited Time and Competing Priorities within Trainee Schedules

Perhaps the most challenging situation for trainees is the limited time and competing priorities within their required curricular and/or clinical schedules. Given the numerous required programmatic obligations that trainees must balance, the addition of research project work may become overwhelming. Program requirements for trainees can also fluctuate throughout the academic/residency year; therefore, it is important to provide the trainee with a timeline and milestone or deliverable deadlines to ensure the trainee is progressing at an appropriate pace. Programs have also reported the importance of a longitudinal training experience that takes place over several months/years, with applicable and dedicated time within the program for trainees to conduct research and scholarship activities.15,18,35–38 For student training programs with course credit associated with them, this has included providing dedicated class time in the course schedule for trainees to work on activities associated with their research.18,24,28–32,37,38 Other resident training programs have described providing the trainees with administrative days in their rotation schedule for reserved time to work on research activities.19

3. INDIVIDUAL TRAINEE BARRIERS TO RESEARCH AND SCHOLARSHIP TRAINING

Described in this section are barriers that are related to the individual trainee. Please see Table 2 for a summary of specific actions that programs can take to effectively overcome individual trainee barriers to research and scholarship training, and whether each strategy is applicable to student training programs or residency training programs.

3.1. Lack of Trainee Interest in a Research Project

Lack of trainee interest is highly detrimental to the ultimate completion of the project because when inevitable obstacles arise while conducting the project, the trainee may not remain as committed. When possible, obtaining potential research projects from a wide variety of disciplines and areas of interest (e.g., from basic sciences to clinical and outcomes research) provides trainees with options that align with their individual interest area. As described earlier, promoting collaboration with other institutions can increase the project types available. Having trainees then meet with a variety of research mentors and rank the projects that they are interested in can help mitigate the issue of lack of interest. Some programs even report allowing trainees the opportunity of developing their own project, although this has the potential to result in project quality and feasibility barriers in addition to requiring the trainee to find a research mentor and build in the necessary time to develop the project.27 The flipped residency research model takes the approach of reinforcing the desired outcomes of the research training program (i.e., the project serving as a conduit for trainees to develop fundamental skills) while providing trainees with the experience of developing a research idea later in the program.19 For programs in which a research experience is not required, it is advisable to have a path for trainees to exit the research experience and hand off the project back to the mentor for potential assignment to another learner. This prevents forcing a poor fit that is unlikely to be productive for the trainee or mentor by obliging the trainee to continue the project.

3.2. Time Constraints to Work on Research Project

Trainees often have limited time and competing priorities within their schedules. Given the numerous obligations that trainees frequently encounter, the additional work of a research project may become overwhelming. Competition for trainees’ time also occurs via elective experiences and extra-curricular activities (e.g., co-curricular organizations, leadership opportunities) that trainees choose to engage in. A key strategy to overcome traditional time constraints is to make the experience longitudinal.18 Programs that try to fit the completion of a research project in a one-year time period will either sacrifice rigor or need to accept that trainees will not see the entire research process from study design to data collection and analysis to dissemination of results. Through a longitudinal experience, trainees are able to spread the time commitment required for the research process over multiple months/years and, therefore, devote the time and attention needed for doing the research well and doing it right. When more time is available, trainees are able to provide an in-depth investment of time and feeling of ownership to advance the project. The benefits of a longitudinal experience may also make it more attractive for faculty to invest time in mentoring the student. It is important to note that a longitudinal experience requires advance planning and flexibility. Consequently, a longitudinal experience may be a more feasible design for pharmacy students, but not conducive for the more constrained pharmacy residency timeline.

It is important for the trainee to be aware of timing considerations associated with the project’s design as this will allow them to ascertain their availability before committing to the project and understand that their responsibilities may focus on a specific facet of a larger project. For example, projects with a prospective study design may have more rigid timing required if the trainee is involved in study recruitment and time-specific data collection, among other activities. Moreover, laboratory-based experimental research may necessitate the trainee to be present in the laboratory at specific times and/or extended periods of time that do not align with the trainee’s course or rotation schedule. Projects with a retrospective study design, or involving analysis of existing data, may be associated with more flexible timing and settings for research activities.

For some programs, particularly pharmacy residency programs, it may not be possible to extend the research experience beyond one year. In these instances, the flipped residency research model offers a solution to enhance the efficiency and depth of the experience.19 The flipped residency research model modifies the research timeline to better align research activities with trainee abilities at specific time points during the year. The flipped model maintains the residents’ exposure to all of the key steps of the research process but in a modified format, which begins with data collection, analysis, presentation, and dissemination on one project followed by ideation and methodology development on a second project. The first project was initiated during the previous year by another resident and the second project is handed off to an incoming resident at the completion of the residency year.

3.3. Trainee Departs Prior to Research Project Completion

In the literature, there are consistent examples of programs setting research timelines for trainees with milestones to help ensure project completion within the designated timeframe.18,19,35,39,40 Specific deliverables can also be required by the program to guide the trainee through the different phases of the research process. In some instances, programs have even required completion of a manuscript and submission to a journal to meet graduation requirements.19,24,41 Yet circumstances may occur where the trainee completes their degree or residency training prior to completion of their research project. It can be detrimental to the project if this occurs with no follow-up or transition plan to continue and complete the project. The trainee should be strongly encouraged to engage in post-training correspondence with their research mentor to ensure a smooth transition to onboard a new trainee and/or develop a timeline to complete the project and manuscript submission (and resubmission if necessary) post-training. It may also be beneficial for the program to include the completion of a goals and expectations agreement between the mentor and trainee describing the expected transition plan. Team-based research projects and layered learning models may also allow senior trainees to serve as the project lead and connectors between new junior members of the project team. When feasible, a longitudinal design may be the most optimal strategy to mitigate this barrier as it allows for built-in time to complete the project or come to near completion, hand-off the project, and/or submit (and revise and resubmit) a manuscript.

3.4. Lack of Knowledge of the Publication Process and Manuscript Rejection

Barriers exist related to lack of knowledge of the publication process, such as submission and revision guidelines. A cross-sectional survey to pharmacy residents indicated low self-perceived ability to publish, leading to low scholarly productivity.42 Accordingly, manuscript rejection also provides a challenging situation for trainees. Academic journals routinely receive more manuscript submissions than they editorially accept.43 The rejection of a manuscript can be disappointing and demoralizing for trainees, especially if the submission is their first one and they do not understand that resubmission of a manuscript is common and should be expected and/or that the peer review process is important to ensure scientific rigor and rejections are part of that process.

The project that the trainee is working on in the training program may be the first one that they will submit for publication. Therefore, published programs have described research seminars held on the publication process and have provided trainees with successful examples of abstracts, cover letters, and components of a manuscript.18,19,22,44 Having experienced research mentors, and senior trainees who have gone through the process, available to the trainees is also important as they can offer guidance and support through the publication process.45

If abstract or manuscript rejection occurs, it is important for the trainee to understand that constructive feedback and rejection is part of the peer-review process and being able to withstand rejection and its associated comments dispassionately will be a beneficial learning opportunity. Trainees should understand – and internalize – that the research and scholarship field rewards persistence and iteration, and the results of the peer review process are shared by all authors and not just the trainee. Moreover, the peer review process is intended to improve the quality of the manuscript. Experienced research mentors can discuss their own academic rejection experience and help guide the trainee through the resubmission process. Mentors should also be encouraged to invite trainees to participate in manuscript peer review opportunities, when possible. This provides another avenue for trainees to gain appreciation of the peer review process and improve the quality of the manuscripts that they prepare.

4. RESEARCH PROJECT BARRIERS TO RESEARCH AND SCHOLARSHIP TRAINING

In addition to programmatic and individual trainee barriers, project-related barriers may also hinder the potential to provide a high quality research and scholarship training experience. Please see Table 3 for a summary of specific actions that institutions can take to effectively overcome project barriers to research and scholarship training, and whether each strategy is applicable to student training programs or residency training programs.

4.1. Length of Time to Initiate a Research Project

Several activities can cause barriers to initiate a project – idea synthesis, connecting trainees with research mentors and projects, and obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) or other regulatory approval.42 In order to expedite this process, several programs have commenced activities prior to the research timeline of the trainee.18,22,24,27,36,39,44,46,47 This includes soliciting project ideas from mentors several months prior to the start of the training program and/or having the trainee formulate their research project ideas while participating in the orientation of their program. It is also efficient to have a formal connection process for trainees and research mentors that is facilitated by the program’s oversight committee. This process may encompass the trainee meeting with several potential mentors to discuss the project and assess fit between both parties. Several programs describe having a ranking process where the trainee submits their rank of projects/mentors that they would like to work with and the mentors either submitting their own rankings or confirming their agreement of the connection.18,19

In regard to improving IRB efficiency, project delays can be avoided through timely submissions early in the training years and communication with the project team during the IRB process. The project team previewing the IRB submission documents and providing feedback prior to submission may help facilitate a timely approval. There have also been instances where faculty have facilitated mock IRB review sessions to provide teams with feedback and refinement recommendations prior to submission.25 The institution’s IRB may also require training and certification of each personnel member listed, so providing formal guidance to the trainee early in their program on the certification required to complete or transfer from a prior institution is advantageous. IRB submission to acceptance can take anywhere from days to months and should be factored into the research timeline. Many resident and student research projects may be characterized as “exempt” or “expedited” by the IRB, shortening the review time, but each institution may contain different requirements and should be examined prior to submission.48

4.2. Need for Training on Methodology Relevant to the Research Project, Including Statistical Analysis Training or Support

The methodology required for meaningful project results vary from project to project. Methodological training must occur before one can generate data for analysis. For example, laboratory experiments require a multitude of environmental and health safety training as well as developing comfort with instrumentation usage and troubleshooting. For clinical research, it is necessary to define the variables for electronic health record data extraction and training is required for use of the data management tool. Different methods are also utilized for quantitative and qualitative research projects. Although different data collection, management, and analysis methods and software needs exist for different projects, a common theme reported is the need for statistical analysis training or support.49–52

Ensuring that the projects have the necessary methodological resources available, including for the statistical analysis phase of the project either through mentor guidance or additional support available at the institution, prior to project initiation is critical. Completing the statistical analysis phase, for example, can often present significant barriers for student and resident research training programs. For this phase, institutions will have to first determine whether their goal is for the trainee to lead the data analysis phase or to provide collaborator support for data analyses.

For institutions seeking to have their trainees perform some or all of the analyses, successful programs and/or research mentors may provide research fundamental sessions in data collection and analysis with hands-on training, empowering the trainee to perform the statistical analyses for their project and appropriately interpret and accurately communicate results.18,19,24,27,33,35,39,41,53–56 There are also free tutorials and resources online that the trainee may use to learn how to perform the statistical analyses for their project. For institutions seeking to provide support to their trainees for data analysis, schools of pharmacy and residency programs associated with academic institutions or through collaborations may be able to engage faculty, data analysts, or graduate students with expertise in biostatistics or qualitative analysis to support the trainee. Institutions may also have access to other units on their campus that are able to provide statistical support to trainees (e.g., biostatistics department on an academic campus, data informatics unit within a health-system). Regardless of the option taken, decisions regarding the analysis plan need to occur early in the project to ensure that all of the data needed is collected in the correct format and the statistical analysis is conducted and interpreted appropriately.

4.3. Selection of Research Project that Lacks Rigor, Depth, or Feasibility

Given the traditional fixed time frame for a research and scholarship training program, it can be common for projects to lack scientific rigor, particularly if the program requires a research project, must accommodate a large number of trainees, and/or the trainee develops a project with little guidance from a research mentor.11 As an example, a common barrier resulting in a lack of scientific rigor includes the project having a limited sample size due to a myriad of reasons, minimizing the ability to produce generalizable knowledge. These may be contributing factors to trainee research project publication rates being less than 15% and/or the project often having no meaningful next step.11,57–59

It is encouraged to integrate trainees into already existing research and scholarly agendas of well-trained and experienced research mentors to help ensure the novelty of the project in advancing already existing literature in the area. This may include integrating trainees into multiyear and/or multisite projects where the trainee can make a significant contribution to a component of the overall project. Many published research and scholarship training programs also describe the use of a research advisory-type group to review the project options to determine feasibility, novelty, rigor, and impact prior to becoming available to trainees.18,19,39,45,46,54

4.4. Resource Constraints to Complete Research Project and Disseminate Results

In addition to support through the development and execution of the research project, trainees often need resources in order to complete the research and/or disseminate the project results. This includes support for laboratory materials, software licenses, additional personnel, publication fees, poster printing, and travel to conferences, among other items. It is advisable to have the trainee research potential journal options early to examine costs of publishing and ensure sufficient funds are available and/or steer the trainee towards relevant journals without publication costs. Many organizations offer trainee research grants and travel awards to help offset costs associated with research activities and attending and presenting at annual meetings and conferences. Often trainees need to be made aware of these awards and are encouraged to apply. As stated above, it can also be advantageous to integrate trainees into already existing research and scholarly agendas of the mentor. In addition to helping to ensure the novelty of the project, the mentor may also have access to funds to support the dissemination of the research. Programs have also reported setting aside institutional funds or contributions through endowments to help offset costs associated with the research process.37,38,60

5. CONCLUSION

This “how-to” guide serves to assist pharmacy school faculty and residency program directors with effectively providing a research and scholarship experience to their trainees. Common programmatic, individual trainee, and project barriers within research and scholarship training programs, along with strategies for overcoming those barriers, based on our own experiences and those described in the literature, have been described herein. It is important to note that the applicability of the strategies to individual student and/or resident training programs is dependent on the local infrastructure, resources, and goals of each institution. Additionally, residency programs tend to be more constrained by time limits of programs and not all residency programs may be affiliated with universities in which they are able to utilize academic resources and/or personnel. We offer the following overarching recommendations below to overcome barriers previously described in this manuscript. These strategies were utilized in the design and implementation of our student and resident training programs at UNC, which resulted in an increase in scholarly output and trainee confidence in research fundamentals.18,19 Both student and resident training programs should be able to incorporate most, if not all, of the following recommendations to provide high-quality and feasible research and scholarship training that promotes trainee skill development, advancement of impactful research projects, and presentation and publication opportunities for trainees:

Obtain institutional leadership support for the training program and its alignment with the research and scholarship mission of the organization

Utilize a reverse-engineering approach to design the program and develop clearly defined guiding principles, learning outcomes, and assessments, which will be used to inform subsequent design and implementation decisions for the program

Establish an oversight committee to provide programmatic leadership, facilitate the connection of trainees and mentors, and provide support of trainee-mentor pairs throughout the experience

Integrate trainees into existing research programs of active investigators and high-priority organizational initiatives instead of asking mentors to create projects outside of their scope or interest to accommodate learners

Solicit research project ideas from mentors in advance that carefully consider the trainee’s role in the project and feasibility to execute within the program timeline; layered-learning mentorship and trainee contributions to larger, ongoing projects should be encouraged when feasible

Incentivize trainee participation by providing a high value experience with opportunities to select a project/mentor of interest, obtain programmatic (e.g., certificate, honors) recognition, and disseminate their work through national meeting presentations and/or publications

Incentivize mentor participation by providing access to trainees that can advance their own research program, institutional teaching and service credit, and administrative days for practitioners serving as research mentors

Create a structured timeline for project initiation and completion of scholarly deliverables such as a project proposal, poster presentation, and draft original research manuscript

Include dedicated time within the training program for trainees to conduct research and scholarship activities and, if feasible, provide a longitudinal experience

Deliver educational sessions to trainees on fundamental topics common to most research projects such as biostatistics, study design, scientific writing, poster presentations, and the publication process

Provide research and financial support to facilitate project execution and dissemination such as access to data analysis services, poster printing and travel support to professional meetings, and promotion of trainee travel or research awards

Perform frequent assessment of the student experience, mentor experience, and program outcomes as a means towards continuous quality improvement of the program and execution of its stated objectives.

Acknowledgements:

ASD is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under Award Number T32GM086330. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.American College of Clinical Pharmacy, Lee MW, Clay PG, et al. The essential research curriculum for doctor of pharmacy degree programs. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;9:966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deal EN, Stranges PM, Maxwell WD, et al. The importance of research and scholarly activity in pharmacy training. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(12):e200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobaugh DJ. A professional imperative: developing pharmacy residents as the next generation of practice-based researchers. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015; 72:615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Available from https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 5.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) 2013 Educational Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP). Required competency areas, goals, and objectives for postgraduate year one (PGY1) pharmacy residencies. Available from https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/professional-development/residencies/docs/required-competency-areas-goals-objectives. Accessed November 6, 2020.

- 7.Bulkley CF, Miller MJ, Draugalis JR. Developing and improving residency research training. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slack MK, Martin J, Worede L, Islam S. A systematic review of extramural presentations and publications from pharmacy student research programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(6):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKelvey RP, Hatton RC, Kimberlin CA. Pharmacy resident project publication rates and study designs from 1981, 1991, and 2001. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010:830–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Dell KM, Shah SA. Evaluation of pharmacy practice residents’ research abstracts and publication rate. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003. 2012(4):524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasegawa GR. Publication of residency projects: another perspective. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:77–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irwin AN, Olson KL, Joline BR, Witt DM, Patel RJ. Challenges to publishing pharmacy resident research projects from the perspectives of residency program directors and residents. Pharm Pract. 2013;3:166–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ascione FJ. Research requirement for PharmD students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClendon KS, Bell AM, Ellis A, et al. Pathways to improve student pharmacists’ experience in research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(4):58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kao DJ, Hudmon KS, Corelli RL. Evaluation of a required senior research project in a doctor of pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SE, Whittington JI, Nguyen LM, Ambrose PF, Corelli RL. Pharmacy students’ perceptions of a required senior research project. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth MT, Mumper RJ, Singleton SF, et al. A renaissance in pharmacy education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. N C Med J. 2014;75(1):48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morbitzer KA, McLaughlin JE, Ozawa S, et al. Implementation and initial evaluation of a research and scholarship training pathway in a PharmD curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020. DOI: 10.5688/ajpe8079. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morbitzer KM, Rao KV, Rhoney DH, et al. Implementation of the flipped residency research model to enhance residency research training. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76:608–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assemi M, Ibarra F, Mallios R, Corelli RL. Scholarly contributions of required senior research projects in a Doctor of Pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(2):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooley J, Nelson M, Slack M, Warholak T. Outcomes of a multi-faceted educational intervention to increase student scholarship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(6):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velluratti RP, Puglisi MP, Johnson CL, Slonek J. Introduction of a capstone research program in a new college of pharmacy: Student perceptions. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2014;6:429–436. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vest MH, Petrovskis MG, Savage SW, et al. Impact of an innovative partnership in patient care between an academic medical center department of pharmacy and a school of pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76:2070–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spooner JJ, Kennedy DR. An elective course to foster interest in acacemic pharmacy career opportunities. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuentes D, DeGuire N, Patel R, Boyce E. A team public health research project for first-year pharmacy students to apply content from didactic courses. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(6):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minshew LM, Yi J, Morbitzer KA, McLaughlin JE. A review of capstones that synthesize and apply knowledge and skills in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020. DOI: 10.5688/ajpe8060. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pruchnicki MC, Rodis JL, Beatty SJ, et al. Practice-based research network as a research training model for community/ambulatory pharmacy residents. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slack MK, Warholak T, Murray JE. Writing a research proposal: A workshop course developed for PharmD students. Pharmacy Education. 2015;15(1):10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao PS, Endicott R, Mullins R, Rao US. A 6-week laboratory research rotation in pharmacogenomics: a model for preparing pharmacy students to practice precision medicine. Pharmacogenomics J. 2018;18:601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez A, Rabionet S, Bleidt B. Teaching research skills to student pharmacists in one semester: An applied research elective. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Overholser BR, Foster DR, Henry JR, Plake KS, Sowinski KM. The influence of an elective introductory clinical research course on pharmacy student interest in pursuing research-based careers. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(9):165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McRae M, Salgado TM, Patterson JA, et al. Educational outcomes resulting from restructuring a scholarship course for doctor of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(8):7246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaidean GD, Vansal SS, Moore RJ, Feldman S. Student scientific inquiry in the core curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds HL, Kearns KD. A planning tool for incorporating backward design, active learning, and authentic assessment in the college classroom. College Teaching. 2017;65(1):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swanoski MT, Akers MF, Amaro ML, Huot KL, Lutifiyya MN. Incorporating research into a postgraduate year 1 pharmacy residency. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(9):175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puglisli MP, Johnson CL, Vellurattil R, Wilcox M, Slonek J, Mukherjee K, Gentry E. Mentor perceptions of the value of a fourth year research project for doctor of pharmacy students. Pharmacy Education. 2018;18(1):217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harirforoosh S, Stewart DW. A descriptive investigation of the impact of student research projects arising from elective research courses. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estes FG. A collaborative clinical pharmacy research assistant programme for pharmacy students. Pharmacy Education. 2014;14(1):44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker JW, Bean J, Benge C, McFarland MS. Designing a resident research program. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71:592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dagam JK, Iglar A, Kindsfater J. Development and implementation of a residency project advisory board. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:919–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandl K, Adler D, Kelly C, Taylor P, Best BM. Effect of a dedicated pharmacy student summer research program on publication rate. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(3):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pinelli NR, Sikora AN, Witherspoon LA, Rao KV, Rhoney DH. Impact of pharmacy residency research training on residents’ actual versus perceived ability and interest to identify and solve practice-related problems. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29:421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bauman JL, Jackevicius C, Zillich AJ, Parker RB, Phillips BB. On the methodology of retrospective chart reviews. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2019;2:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLaughlin MM, Short E, Prusi R, Masic D, Chapman NRM, Postelnick M. Implementation of a pharmacy research committee to enhance the pharmacy resident research experience. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9:1141–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swanson JM, Shafeeq H, Hammond DA, Li C, Devlin JW. Association between postgraduate year 2 residency program characteristics and primary project publication. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(6):384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dick TB, Moorman KL, MacDonald EA, Raines AA, Matthews Cox KD. Defining and implementing a model for pharmacy resident research projects. Pharm Pract. 2015;13(2):562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirwin JL, Burton D, Maddali N, Gonyeau MJ. Implementation of a research capstone course with expanded flexibility. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2019;11:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michalets EL, Williams C, Park I. Ten year experience with student pharmacist research within a health system and education center. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10:316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee R, Dahri K, Lau TTY, Shalansky S. Perceptions of hospital pharmacists concerning clinical research: A survey study. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2018;71:105–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shafeeq H, Hammond DA, Swanson JM, Li C, Devlin JW. Critical care PGY-2 graduate perceptions and practices regarding residency project publication. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(2):6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bookstaver PB, Miller AD, Felder TM, Tice DL, Norris LB, Sutton SS. Assessing pharmacy residents’ knowledge of biostatistics and research study design. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:991–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newsome C, Ryan K, Bakhireva L, Sarangarm P. Breadth of statistical training among pharmacy residency programs across the united states. Hosp Pharm. 2018;53:101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Billups SJ, Olson KL, Saseen JJ, Irwin AN, Touchette DR, Chennault RR, Kurz D. Evaluation of the effect of a structured program to guide residents’ experience in research (ASPIRE) on pharmacy residents’ knowledge, evidence, confidence, and attitude toward research. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(6):631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coons JC, Benedict N, Seybert A, et al. A pharmacotherapy scholars program to provide intensive training to enhance pharmacy students’ postgraduate readiness. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83:7327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghoneim O, Alper RH, Szollosi DE, Sweezy MA, Vadlapatla R, Edafiogho IO. Implementation of an elective course to introduce pharmaceutical sciences research. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2016;8:501–508. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Newsome C, Ryan K. Cultivating statistical knowledge in pharmacy residents’ research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(7):434–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olson KL, Holmes M, Dang C, Patel RJ, Witt DM. Publication rates of abstracts presented by pharmacy residents at the Western States Conference. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stranges PM, Vouri SM, Bergfeld F, et al. Pharmacy resident publication success: Factors of success based on abstracts from a regional meeting. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2015;7:780–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hung M, Duffett M. Canadian pharmacy practice residents’ projects: publication rates and study characteristics. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66:86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banks ML, Haynes K, Sprague JE. A model for motivating PharmD students to pursue a PhD degree. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2009;1:93–97. [Google Scholar]