Abstract

Objectives:

The study aims were to explore stakeholder perceptions about cognitive screening in a rural, ethnically diverse, underserved setting, and to examine whether perceptions varied by years lived in a rural area, career, health literacy, willingness to be screened, ethnicity, education, or age.

Methods:

Twenty-one rural, ethnically diverse stakeholders completed an open-ended interview of five questions and a measure regarding perceptions about cognitive screening (PRISM-PC, Boustani, et al., 2008). Open coding using the in vivo process (Saldaña, 2015) to “derive codes from the actual participant language” (p. 77) was used to analyze the qualitative data. We used Pearson correlation to examine relationships between the PRISM-PC and sociodemographics including age, years of education, health literacy, years lived in rural areas, and willingness to participate in cognitive screening.

Results:

Eight codes and two themes were identified from the in vivo analysis. The eight codes were “a sentence being pronounced over the lives”, “keep everybody at home”, “Education is big”, the trust issues is everything here”, “identify support systems”, “access to care”, and “there is a cost to do that”. The two themes were “Trust is the essential component of connecting with Community”, and (2) “The Community recognizes the importance of knowledge in improving care. PRISM-PC results added new information in that persons were concerned about the emotional and financial burden on their families. Overall, regardless of age, careers, care involvement, health literacy, or education, 81% of stakeholders indicated they would seek annual cognitive screening.

Discussion:

It is important for rural health professionals to consider that contrary to previous stigma concerns, stakeholders may support earlier dementia detection.

Keywords: Screening and diagnosis, beliefs/attitudes, cultural aspects, psychological and social aspects, mild cognitive impairment

Despite the rapidly growing number of older adults at risk for cognitive impairment, many persons do not receive screening or follow-up diagnostic evaluations. Researchers recently cited estimates that more than 50% of patients with dementia do not receive a cognitive assessment prior to institutionalization (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016). Recognizing the risk of increased morbidity from delayed dementia detection, the Institute of Medicine designated early detection of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias as one of six aims for improving the quality of the health care system (Whittington, Nolan, Lewis, & Torres, 2015). Since that time, other health agencies, including the Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s Foundation of America, the American Medical Association and the Association of Family Physicians have released statements recommending cognitive assessment for older adults at risk for dementia, which is now mandated as part of the Medicare/Medicaid Annual Wellness visit (National Institute of Aging, 2017) by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Shaw, Asomugha, Conway, & Rein, 2014).

Background

Persons who live in rural areas experience a greater incidence of hypertension, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses that place them at higher risk for AD (Mattos et al., 2017). Residents with undiagnosed dementia experience higher rates of falls and unintentional harm while performing activities of daily living, including driving, cooking, and managing medications (Amjad, Roth, Samus, Yasar, & Wolff, 2016). Persons living in less populated rural areas may experience additional harm related to living in isolation. Lack of access to current knowledge regarding the benefits of early AD detection lead to uninformed perceptions regarding cognitive screening (Fowler, Perkins, & Turchan, 2015).

Benefits of early dementia detection

In addition to decreasing the burden of delayed dementia diagnosis, of which AD is the most prevalent type, there are benefits to earlier awareness of disease or disease risk (Alzheimer’s Association, 2018; Livingston et al., 2017). These benefits provide (1) an opportunity for earlier care planning, (2) the identification of potentially reversible causes such as medication side effects, sleep disorders and clinical depression (Barnett, Lewis, Blackwell, & Taylor, 2014) (3) incentive to increase social engagement that may help to delay onset (DiNapoli, Wu, & Scogin, 2014), (4) education and treatment (Beydoun et al., 2014, and end-of-life planning (Ashton, Roe, Jack, & McClelland, 2016)). Knowledge of risk also offers the opportunity to improve adherence to medical regimens for chronic illness such as diabetes (de Bruijn & Ikram, 2014) and hypertension (Huang et al., 2014) that are known to increase AD risk and adopt healthier lifestyles by modifying unhealthy dietary regimens and increasing exercise patterns (Sherzai et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2016; Watson, 2016). There is growing evidence pointing to greater efficacy of dementia medications when started earlier in the disease process (Morley et al., 2015).

Literature review

Despite the latest findings regarding increased AD risk among underserved populations, (Cassarino, O’Sullivan, Kenny, & Setti, 2016; Contador, Bermejo-Pareja, Puertas-Martin, & Benito-Leon, 2015; Ervin, Pallant, Terry, et al., 2015), recent research is scant regarding cognitive screening in underserved rural populations. Likewise, no recent studies could be located regarding rural stakeholder perceptions about cognitive screening. In a systematic review of 720 abstracts and 185 full-text articles, Martin and colleagues (Martin et al., 2015) examined general public and health care professionals’ perceptions regarding cognitive screening. Findings were that the available literature regarding attitudes about community screening is “diverse and fragmented and difficult to draw conclusions” (p.10). Rurality and ethnicity were not addressed.

Recent studies investigating cognitive screening behaviors among culturally diverse populations are also limited, although the risk of AD is increased in underserved populations (Barnes & Bennett, 2014; Lines, Sherif, & Wiener, 2014; Mattos et al., 2017; Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry, & Whitmer, 2016; Mehta & Yeo, 2017). Boustani et al. (2008) and Dale, Hougham, Hill, and Sachs (2006; Dale, Hemmerich, Hill, Hougham, & Sachs, 2008) found that African Americans would be more likely to seek cognitive screening than Whites if it were offered, while Demirovic and colleagues (Demirovic et al. 2003) found that African Americans were more likely to seek evaluation than Hispanics or non-Hispanic Whites. Fowler et al. (2012, 2015) found that the overwhelming majority of 558 urban-dwelling residents of all ethnicities and education were willing to be screened if benefits to screening were understood. In a study of 200 African Americans and Whites in the Atlanta, GA area, Howell and colleagues (Howell et al., 2016) recently concluded that a “better understanding of the knowledge and attitudes toward AD among older adults is critical in enhancing research participation, designing education programs, and accelerating AD prevention and cure” (p. 364).

Need for cognitive screening in rural settings

Researchers have cited that cognitive screening is especially needed in underserved rural areas where the majority of older adults reside (Abner, Jicha, Christian, & Schreurs, 2016; Meit et al., 2014; Winblad et al., 2016). In recent meta-analyses, researchers highlighted root causes for increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common type of dementia, in rural underserved groups (Mehta & Yeo, 2017; Prince et al., 2013; Weden, Shih, Kabeto, & Langa, 2017). These root causes of rural health disparities include low employment, low income, poor nutrition, lack of insurance, language barriers, limited education, inadequate knowledge of navigating a limited health care system, low health literacy, and insufficient access to primary and specialty providers (Abner et al., 2016; Dubois, Padovani, Scheltens, Rossi, & Dell’Agnello, 2016; Lines et al., 2014; Mayeda et al., 2016; Sayegh & Knight, 2013; Wiese, Williams, & Tappen, 2014).

The lack of trained providers in rural areas who can offer a timely dementia diagnosis leads to delayed disease recognition, increase in comorbid conditions, earlier admission to and lengthier stays in healthcare institutions. This delay in dementia detection results in soaring healthcare costs (Dubois et al., 2016; Lines et al., 2014; Knudson & Meit, 2017).

Earlier education and screening interventions for other chronic diseases such as diabetes (Aponte, Jackson, Wyka, & Ikechi, 2017), cancer (Schoenberg, Howell, & Fields, 2012; Schoenberg, Studts, Hatcher-Keller, Buelt, & Adams, 2013) and cardiovascular disease (Fahs et al., 2013) have resulted in earlier diagnosis of these conditions in rural populations. However, formalized education and screening programs for rural and/or underserved older adults facing increased risk of cognitive impairment are lacking (Adler, Lawrence, Ounpraseuth, & Asghar-Ali, 2015; National Alzheimer’s Project Act, 2016; Yaffe et al., 2013). The authors of this paper were interested in exploring rural stakeholder perceptions toward cognitive screening as a first step in developing a cognitive screening program for community-dwelling rural older adults.

Theoretical framework

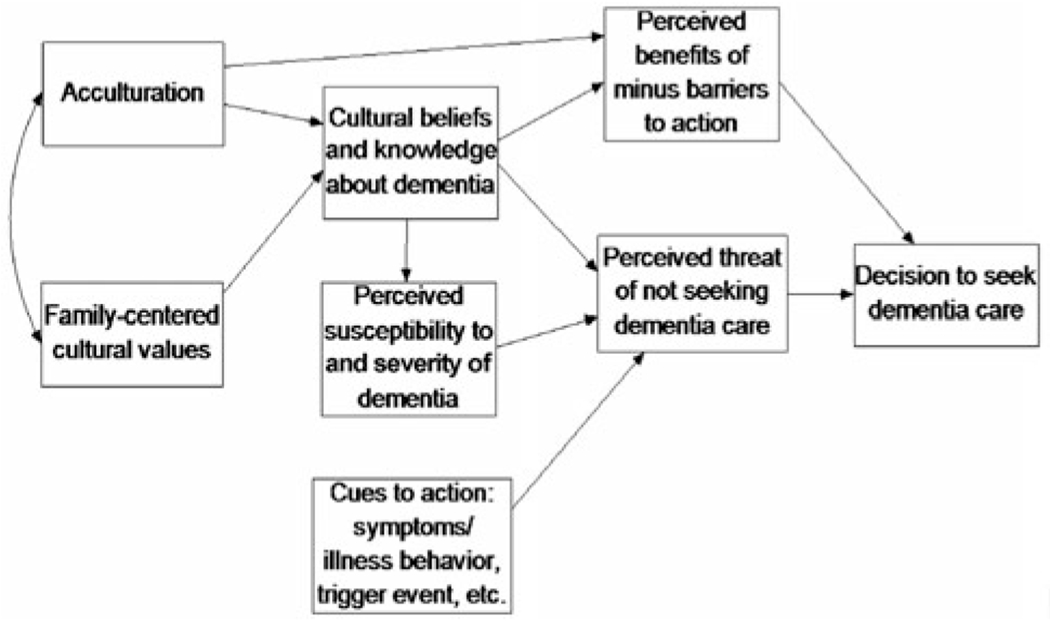

The Sociocultural Health Belief Model (SCHBM) by Sayegh and Knight (2013) (Figure 1) was the framework used in guiding this research to explore cognitive screening perceptions among rural stakeholders. Sayegh and Knight modified the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, Strecher, & Becker, 1988) to improve the explanatory model of dementia for use in underserved groups. Specifically, Sayegh and Knight (2013) describe the SCHBM as a framework for identifying cross-cultural patterns of seeking dementia evaluation and care. They identified barriers to cognitive screening in minority ethnic adults which are also barriers for rural residents. These barriers include lower levels of acculturation, lack of knowledge about the disease, cultural beliefs about dementia, and lack of healthcare access. Sayegh and Knight point out that these barriers ultimately influence perceptions about dementia susceptibility and severity. Outdated perceptions about dementia detection may diminish cues to action and prevent residents from participating in earlier cognitive screening (2013).

Figure 1.

The Sociocultural Health Belief Model for dementia care-seeking*.

Note: from Sayegh and Knight (p. 518, 2013): Though the model we present here includes only key variables, demographic variables (e.g. age, education) should be included as background variables in any analysis plan. It should also be noted that acculturation only applies to immigrants and certain minority ethnic individuals (e.g. those with fewer generations of US residency). All variables need not be examined at once in any individual analysis or study. In addition, the correlations among the endogenous variables should be examined before running any analyses; the relations presented in this model are hypothesized based on prior research and theory. Finally, this model can also be adapted for conditions other than dementia for which the key variables may be relevant.

*Sayegh P, Knight BG. (2013). Cross-cultural differences in dementia: the Sociocultural Health Belief Model. International psychogeriatrics/IPA. 2013;25:517. doi:10.1017/S104161021200213X

The purpose of this study was to explore perceptions about cognitive screening among a group of south Florida ethnically diverse rural stakeholders, and examine if those perceptions influenced willingness to be screened. The research questions addressed through qualitative inquiry were (1) What are the community stakeholders’ perceptions toward cognitive screening? (2) Were there significant correlations between sociodemographic variables (education, health literacy, age, or years lived in a rural area) and stakeholder perceptions about screening? (3) Do perceptions about cognitive screening impact stakeholder willingness to be screened? Answers to the research questions will inform the development of a culturally congruent intervention to increase cognitive screening rates among rural older underserved adults.

Method

To answer research questions one and three regarding community stakeholders’ perceptions toward cognitive screening, an open-ended, semi-structured interview was conducted, and the PRISM-PC (Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care) instrument by Boustani et al. (2008) was administered. The PRISM-PC measures attitudes and perceptions about cognitive screening. To answer research question two regarding the influence of education, health, literacy, age, years lived in a rural area on stakeholder support of cognitive screening, sociodemographic data was collected including a health literacy assessment, and compared with results of the PRISM-PC items using Pearson’s r correlations. Data from the PRISM-PC was also compared and contrasted with the overall themes of the qualitative interviews.

Setting and sample recruitment

The setting included the towns of Belle Glade (pop. 19,130) and Pahokee, FL (pop. 6,094) in an area known as “The Glades”, designated as a “rural area of opportunity”, southcentral Florida region by the Rural Economic Development Initiative (2017), as a Medically Underserved Area (MUA), Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA)., and secondary RUCA Code 7.2 by HRSA’s Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (2013The Glades has a higher percentage of residents over age 65 (26.5%) compared with the national average of 18%. More than a third of the residents live below the poverty level and only 65% received a high school diploma. This community is also culturally diverse, as 78% of the residents are African American, Afro-Caribbean, and Hispanic (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017).

To be included in this study, potential stakeholders were sought from among those living or working in Belle Glade or Pahokee Florida for at least five years. Stakeholders were defined as “a person or group not owning shares in an enterprise but affected by or having an interest in its operations, such as the employees, customers, local community, etc.” (Collins English Dictionary (2004, p. 1274). Potential stakeholders were excluded if they were not able to understandand speak English, or expressed that they did not know the community well. Data were collected until saturation was reached and no new findings emerged from the initial data analysis. After the interview, stakeholders completed quantitative measures; a sociodemographic survey including a measure of health literacy (REALM-SF)) (Arozullah, et al., 2007) and a perceptions of cognitive screening scale (PRISM-PC) (Boustani et al., 2008).

Data collection procedures

Recruitment

Community stakeholders were recruited by referral from local service organizations, physician offices, church councils, and the senior center. Emails were sent inviting stakeholders to participate. Attendees of the local senior center were invited through an announcement and sign-up sheet.

Interviews

Dates and times for the interviews were agreed upon between the researcher and stakeholder. The researcher traveled to places of business (n = 16) or senior centers (n = 5) where the interviews were held in private settings, and recorded after obtaining informed consent. The interview recordings were transcribed into a Word 2010 document by an online transcription service, corrected by a trained research assistant, and verified for accuracy by the primary investigator.

An open-ended semi-structured interview guided the descriptive exploration of stakeholders’ perceptions of cognitive screening. The open-ended questions were guided by the SCHBM (Sayegh & Knight, 2013) as seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exploring perceptions interview questions framed by Sayegh and Knight (2013) Sociocultural Health Belief Model*.

| Interview Question | Sociocultural Health Belief Barrier: Knowledge | Sociocultural Health Belief Barrier: Acculturation | Sociocultural Health Belief Barrier: Health Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| “What do you see as benefits to routine screening for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) for older adults over age 65? | X | ||

| In what ways would cognitive screening be beneficial to persons at risk for AD/their families/the community? | X | X | |

| What do you see as reasons to not do regular screening for AD in your community”? | X | X | |

| What do you think may prevent people from seeking routine screening for AD in your community? | X | X | X |

| To Lay Members Only: “Please give me some suggestions for making it easier for older adults to be screened for AD” | X | X | |

| To Professionals Only: “What could people in your position do to make it easier for older adults to be screened earlier for AD? | X | X | |

| What fears do you have related to the subject of cognitive screening”? | x | x |

Measures

Sociodemographic survey

This survey included thirteen questions about sex, gender, race, ethnicity, education, as well as questions regarding years lived in a rural area, caregiver status, if a health care provider had tested their memory during an office or emergency room visit, and if they would be willing to participate in cognitive screening.

As disparities in health literacy often parallel disparities in health outcomes (Rikard, Thompson, McKinney, & Beauchamp, 2016), health literacy was added as a variable using the The Rapid Estimate of Literacy in Medicine, short form (REALM-SF) by Arozullah et al., 2007. This seven word recognition test has been used in multiple settings. The REALM-SF has strong reliability with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of .91 (Imoisili et al., 2017).

Stakeholders were asked if they recognized any words, and to read those out loud. The seven words were Menopause, Antibiotics, Exercise, Jaundice, Rectal, Anemia, and Behavior. The results were analyzed by grade levels from below third grade to high school and functional ability. For example, if the subject was unable to read any of the seven words, a score of zero would be assigned. This score would place the subject in the category of “third grade and below; will not be able to read most low-literacy materials; will need repeated oral instructions, materials composed primarily of illustrations, or audio or video tapes.” The REALM-SF categorizes health literacy as low (≤ 6th grade), marginal (7th–8th grade), or adequate (≥ 9th grade).

Perceptions regarding investigational screening for memory in primary care (PRISM-PC) scale

(Boustani et al., 2008). This scale was developed after an extensive literature review and opinions of 16 clinician investigators with experience in cognitive screening (Boustani et al., 2008). The intent of the items is to assist the researcher in identifying both the patients’ acceptance of dementia screening and the perceived benefits or harms of dementia screening. Thirty-five questions in the PRISM-PC that were scored on a Likert Scale of 1-5 ranging from “strongly disagree to “strongly agree”. Items were reverse scored so that a higher score indicated greater agreement with the statement. These items addressed benefits of dementia screening (8 items), stigma of dementia screening (ten items), negative impact of dementia screening on independence (five items), suffering related to dementia screening (four items), perceived acceptance of different types of dementia screening (six items), and concern the belief that a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease is not currently available (two items).The PRISM-PC instrument has been used multiple times since the original study (Boustani et al., 2008) in both (primary and community care settings with over 800 patients, with the most recent demonstrating similar internal consistency of the subscales with previous studies, reaching 0.85 (Fowler et al., 2015).

Data analysis

To gain understanding regarding perceptions about cognitive screening among 21 rural FL stakeholders, open coding and the in vivo process (Saldaña, 2014, 2015) was used to analyze the results of the open-ended interview style of qualitative inquiry. Correlations between results of the PRISM-PC instrument and sociodemographics of age, years of education, health literacy, years lived in rural areas, and willingness to participate in cognitive screening were examined.

Qualitative analysis

The research questions addressed through qualitative inquiry were (1) What are the community stakeholders’ perceptions toward cognitive screening? (2) Were there significant correlations between the sociodemographic variables (education, health literacy, age, years lived in a rural area, willingness to participate in screening) and stakeholder perceptions about screening? (3) Did perceptions impact stakeholder willingness to be screened?

To investigate community stakeholders’ perceptions toward cognitive screening and “capture the essence of stakeholders’ meanings”, transcripts of recorded interviews were analyzed using the in vivo process described by Saldaña (2014; 2015). In vivo is defined as using the stakeholder’s own key word or phrase to create a coding category (Saldaña, 2014). An in vivo approach is advantageous because it helps to prevent the researcher from infusing their own meaning into the data (Saldaña, 2015).

Prior to beginning data analysis and recognizing that it would be important to first identify personal beliefs, biases, and interests that could influence findings, the researchers met and made a conscious decision to bracket stigmatizing ideas that are sometimes seen in the literature (Sorsa, Kiikkala, & Åstedt-Kurki, 2015). These included the beliefs that persons in rural areas might consider dementia to be a private family matter, or not want to know because of “what could be done anyway” or “everyone gets it eventually” fatalistic attitudes.

Bracketing was followed by establishing codes using the stakeholders’ own words, rather than “researcher-generated words/phrases as a method of attuning oneself to the stakeholder language, perspectives, and world view” (Saldaña, 2015, p. 71). After using NVivo11 (Adu, 2015) computerized software to identify trends, our efforts centered on exploring the potential for contrasting or complementary patterns in the data (Tappen, 2015). To do this, answers to the interview questions and survey items were analyzed for patterns of consistency and variation. Researchers coded the data individually at first, and then met to discuss the findings until consensus was reached regarding which code best represented the data.

Memo-ing

Memo-ing is a technique used by qualitative researchers to stimulate further questions, seek answers, structure hypotheses, and identify areas for further analysis and investigation (Creswell 2017, Saldaña, 2015). The researchers recorded reflective notes during the process of reading and coding the transcripts (Lucas & D’Enbeau, 2013).

Quantitative analysis

To investigate the impact of sociodemographics on perceptions of cognitive screening, the central tendencies and Pearson’s r correlations of the PRISM-PC (Table 2) and sociodemographic, including the REALM-SF data, (Table 3) were analyzed. To investigate the impact of perceptions on willingness to be screened, results from the descriptive summaries of the qualitative inquiry, the sociodemographic variable of willingness to participate in qualitative screening, and the PRISM-PC measure were considered.

Table 2.

Responses to Selected Items of PRISM-PC Survey (Boustani et al., 2008).

| PRISM-PC SURVEY* Frequency / Percent% | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| QUESTION (AD = Alzheimer’s disease) | No | Yes | Maybe |

| 1. I would like to know if I am at higher risk than others for developing AD | 2/9.5 | 18/85.7 | 1/4.8 |

| 2. I would like to know if I have AD | 1/4.8 | 19/90.5 | 1/4.8 |

| 3. I would like to know if I have a problem with memory | 1/4.8 | 20/95.2 | – |

| 4. I would like to be tested for AD with a short questionnaire | 2/9.5 | 19/90.5 | – |

| 5. I would like to be tested for AD with a blood sample | 2/9.5 | 16/76.2 | 3/14.3 |

| 6. I would like to be tested for AD with pictures of my head or brain | 2/9.5 | 16/76.2 | 3/14.3 |

| 7. I would like a doctor to examine me every year to know if I have developed memory problems | 2/9.5 | 17/81 | 2/9.5 |

| 8. I would like a doctor to examine me every year to know if I have developed AD | 2/9.5 | 17/81 | 1/4.8 |

| 9. I do not believe treatment for AD is currently available | 14/67 | 4/19 | 3/14.3 |

| 10. Early detection of AD increases the chance to treat the disease better | – | 20/95.2 | 1/14.8 |

| *11. If I knew that I have AD, my family would suffer financially | 7/33.3 | 10/47.6 | 4/19 |

| *12. If I knew earlier that I have AD, my family would suffer emotionally | 5/23.8 | 13/61.9 | 3/14.3 |

| 13. If knew earlier that I have AD, my family would have a better chance to take care of me | 1/4.8 | 18/85.7 | 2/9.5 |

| *14. If I have AD, I would not want my family to know | 16/76.2 | 5/23.8 | – |

| *15. If I knew I have AD, I would feel humiliated by family members and others. | 19/90.5 | 1/4.8 | – |

| *16. If my friends knew I have AD, I would no longer taken seriously | 8/38.1 | 4/19 | 9/42.9 |

| *17. If I knew I have AD, I would be considered stupid and unable to do things | 15/71.4 | 2/9.5 | 4/19 |

| *18. If knew I have AD, would be ashamed or embarrassed | 15/71.4 | 3/14.3 | 3/14.3 |

| *19. If knew I have AD, I would be depressed | 7/33.3 | 7/33.3 | 7/33.3 |

| *20. If knew I have AD, I would be anxious | 7/33.3 | 9/42.9 | 5/23.8 |

| *21. If knew I have AD, I would give up on life | 20/95.2 | 1/14.8 | – |

| 22. If I found out early that I have AD, I would have more time to plan for the future | – | 21/100 | – |

| 23. If I found out early that I have AD, I would have more time to talk with family about my health care | 1/14.8 | 20/95.2 | |

| 24. If I found out early that I have AD, I would have more time to talk with family about my finances | – | 21/100 | – |

| 25. If I found out early that I have AD, I would sign my advance directive | 1/4.8 | 15/71.4 | 5/23.8 |

| *26. If I was diagnosed with AD, my doctor would not provide the best care for my medical condition problems | 1/4.8 | 14/66.7 | 6/28.6 |

| 27. If I knew earlier that I have AD, I would be motivated to have a healthier lifestyle | 2/9.5 | 17/81. | 2/9.5 |

| *28. If I am diagnosed with AD, my doctor and other health professionals would not listen to me | 14/66.7 | 2/9.5 | 5/23.8 |

| 29. If I knew earlier that I have AD, I would be more willing to participate in research about this disease | – | 21/100 | – |

| *30. If I am diagnosed with AD, I would not be able to get health insurance | 17/81 | 1/4.8 | 3/14.3 |

| *31. If I am diagnosed with AD, I am concerned that my health insurance company would find out | 17/81 | 1/4.8 | 2/9.5 |

| *32. If I am diagnosed with AD, I am concerned my employer would find out | 12/57.1 | 6/28.6 | 1/4.8 |

| *33. If I am diagnosed with AD, I will not be able to get life insurance | 11/52.4 | 2/9.5 | 7/33.3 |

| *34. If I am diagnosed with AD, I would lose my home | 18/85.7 | 3/14.3 | – |

| *35. If I am diagnosed with AD, I would be living in a nursing home | 10/47.6 | 7/33.3 | 4/19 |

These items are classified under the “Perceived Harms of Screening” construct. Those unmarked belong to the “Acceptance of Screening” construct.

Table 3A.

Stakeholder sociodemographics; categorical variables.

| Total Sample n = 21 |

Professionals n = 16 |

Laypersons n = 5 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Male | 5 | 24 | 3 | 19 | 2 | 40 |

| Female | 16 | 76 | 13 | 81 | 3 | 60 |

| Memory Checked | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 29 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 100 |

| No | 15 | 71 | 15 | 94 | 0 | 0 |

| Caregiver | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 43 | 10 | 63 | 2 | 40 |

| No | 9 | 57 | 6 | 37 | 3 | 60 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5 | 24 | 4 | 25 | 1 | 20 |

| African American | 11 | 52 | 9 | 57 | 2 | 40 |

| Afro Caribbean | 2 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 20 |

| Hispanic American | 2 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 20 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 7 | 33 | 6 | 37 | 1 | 20 |

| Widowed | 8 | 38 | 4 | 25 | 4 | 80 |

| Married | 2 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Divorced | 4 | 19 | 4 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

Results

Sociodemographic data

Twenty-five stakeholders were invited to participate by email or in face-to-face encounters; 23 accepted, and 21 completed the interviews and quantitative measures. The sociodemographic results are available in Tables 3(A–C). These stakeholders included social workers (4), healthcare administrators, including one manager and director at a local senior center, (3), nurses (2), nurses’ aides (2), ministers (2), kitchen aides (2), farmworkers (2), auto mechanic (1), church worker (1), clerical worker (1), and physician (1).

Table 3C.

Stakeholder sociodemographics; health literacy levels.

| Grade Level | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0-1 | 3 | 14.3 |

| 2-3 | 2 | 9.5 |

| 4-6 | 1 | 4.8 |

| 7 or greater | 15 | 71.4 |

| 21 | 100.0 |

The sample consisted of 21 rural, ethnically diverse Glades stakeholders. Residents were 21.7% Hispanic, 14% African American, 5.6% American or, Native American Indian, and 68.7% White. Other ethnicities represented less than 1% each. Adults 65 or older comprised 33.8% of the community. Over 20% of residents were living below the poverty level and did not have health insurance. Agriculture was the primary means of employment, with a 62% high school graduation rate (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). The investigators’ university Institutional Review Board approved the study prior to initiating research.

Health literacy was evaluated as a sociodemographic value to understand the characteristics of the sample and to explore if level of health literacy impacted willingness to screen. The majority of the sample tested at a 5.5 level (SD = .7).

Pearson’s R correlations

In examining relationships between sociodemographic variables, significant negative correlations (p = .01) were found between health literacy and years in the Glades, (r = −.83) and health literacy and age (r = −.67). No significant relationships were found between health literacy and ethnic background. There were no significant correlations between any of the sociodemographic variables and willingness to screen: Neither age, years lived in a rural area, years of education, or health literacy level impacted support of routine cognitive screening.

Qualitative findings

Engaging the in vivo process (Saldaña (2014; 2015) resulted in discovery of the eight codes and two themes described below. Credibility of results is discussed.

Codes

Eight codes (Saldaña, 2014) identified through the qualitative analysis. and examples of statements supporting them, are available in Table 4. The code “It [cognitive screening] gives families a chance”, was supported by additional statements such as “Because the fact that you’re learning wha’s going on earlier that it could be treated, and “So they can make any lifestyle changes”. The code “There’s a cost to do that” included stakeholder input such as “I don’t have any money to do anything about it” and “That attitude of, you know, I don’t need to know because I can’t afford to fix it”, and “As a person who has worked with Alzheimer’s, there is no real negative but there are emotional negatives. Many times, family members are very unaccepting of that and they do not treat that person well when they find this out.” The code “Keep everybody at home”, related to subjects’ comments such as “I don’t think you can prevent having the disease, but it is beneficial for you to make the proper arrangements so you can deal with the disease in a better way.” The “Access to care”, code was based on statements such as “Especially for people who are undocumented if they don’t have routine care. So they might not get that screening”, and “I would say in this area it’s because there’s no services available.” The need to “Identify support systems” was emphasized with statements such as “Not only that there’s treatment but also a way to kind of help those type of patients” and “Well, you know, they help me … well they call me and they take me to get treatment and stuff, you know”. In regards to fear, the code “A sentence being pronounced over their lives”, included other comments such as “Some people are afraid to find out, some people are afraid for other people to find out, you know”, and “she’s afraid; she don’t want to have it”. The code “The trust issues is everything here” was only mentioned by the caregivers in the community, with statements such as “This community may surprise you. The issue is trust. If trust can be established it might work” and “The people here; you do need the contact, you need to kind of hold their hands, you know”. “Education is big” or similar phrase was one of the most commonly offered. One of the memorable statements was “But if someone tells you and helps you to understand and to know that because of this, this is why this is happening, then you know, you, you understand it better. And, and you embrace it I think a bit more.”

Table 4.

Examples of in vivo coding of participant responses.

| In Vivo Code | Participant Responses to Interview Questions |

|---|---|

| Interview Question: “What do you see as benefits to routine screening for Alzheimer’s disease for older adults over age 65? | |

| It gives family a chance | To learn more about Alzheimer’s. Now at early age while we have the chance. |

| Prevention screening and prevention is really absolutely critical in terms of almost any health or behavioral health mental health | |

| I also think that once you test it earlier and find out any health issue it is beneficial to the patient. | |

| Yes, you know I would like to know … | |

| I believe that the routine screenings would help figure out who is, uh, in danger at this point. And that would allow people to make plans for the future. | |

| I’m willing to participate in some new, you know, testings, and then I would I’m sure be benefitting. | |

| I feel like many of their treating physicians don’t get in to the sort of, like, preventive kind of underlying issues with cognitive decline until people are really, really symptomatic | |

| Well that would get - be what a cold - in my brain … is good to get tested early for it cause lately you could take a medication | |

| I think it’s important for people to have that helpful information so they can make any lifestyle changes. Um, to try to improve their memory too | |

| Because the fact that you’re learning what’s going on earlier that it could be treated. | |

| It gives family a chance. | |

| Interview Question: In what ways would cognitive screening be beneficial to persons at risk for AD/their families/the community? | |

| Keep everybody at home | Well, if you know what you got then they know how to treat you. |

| I don’t know right now, I ain’t got no idea about that. | |

| It just makes you aware of what you may be dealing with and what resources you may need and support. | |

| Personally, yes, because I have family members who have, um, dementia or had dementia. | |

| Yeah, I like for my children to know if I got it. | |

| I also think it will help the community because everyone doesn’t know about Alzheimer’s. And I think it’s important for them to know. | |

| Well working with the community, um, is a blessing because if you’re close with the members of your community they are able to look out for you. And help, you know, and care for you. | |

| I also think that it’d be beneficial for the community to find out early because same as an individual, you know, anything that we can find out early we can, uh, quickly act upon it. | |

| And I think, um, you know, getting together with some of the community organizations will help | |

| It’ll also help them [caregiver], let them know what’s the next step that they need to do for them. | |

| I also think it will help the community because everyone doesn’t know about Alzheimer’s. And I think it’s important for them to know. | |

| I don’t think you can prevent having the disease, but it is beneficial for you to make the proper arrangements so you can deal with the disease in a better way | |

| Well, it could help address.um, community outreach, what kind of strategies you could help people, um, to try to get everyone. | |

| I think that particular population is grateful for any health care that they get. I think more than other communities where you work, I think, they are responsive to any type of screening that you can offer. | |

| Because the community can plan to better serve those individuals. | |

| To be able to plan for their future care and make their own choices while they’re able to do so with good intent. | |

| Because it allows you to plan. It allows you to identify what other lifestyle you to changes even health, financially, emotionally and identify what support system do you need. | |

| would appreciate it and, um, instead of waiting until the last minute when nothing can be done. You know where you find it in earlier stages. You can work with it a little bit more or slow the process down. | |

| Just that early diagnosis so that they can get some help. | |

| A big benefit for the community is to try to keep everybody at home as long as possible. | |

| Interview Question: “What do you see as reasons to not do regular screening for Alzheimer’s disease in your community”? | |

| There’s a cost to do that | At that point you’ve already missed the opportunity to treat them and to start linking them to services. |

| They don’t have money. I can’t tell you how many times people come to the emergency room: I’ve been sick for six months. | |

| Why didn’t you come? Well so if I have breast cancer what difference does it make? I don’t have any money to do anything about it. That attitude of, you know, I don’t need to know because I can’t afford to fix it. | |

| I don’t think there’s any bad to finding it. | |

| Probably the same, same reasons that they don’t do screenings for anything. They don’t want to know. | |

| I would say in this area it’s because there’s no services available | |

| I don’t see a reason to not do. I’m sure finances will fit in there somehow, who’s going to pay for it, or you know, is insurance going to cover it, or if you, if you diagnose it and recognize that, the next step is going to be huge. | |

| You know there’s nothing you really can do about any kind of disease that you acquire because of the fact that, as we live, as we grow older these things happen that we can’t do anything about. | |

| As we heard earlier today in our meeting, the community may not understand. They [community] may not know how to react to persons, gosh, who are struggling, who see them [persons with dementia] in the store, and also in the community, nagging. | |

| It could be also financial. I personally don’t know if there is a cost to do that uh screening, if the insurance pays for it, so, lack of knowledge. | |

| Interview Question: What do you think may prevent people from seeking routine screening for Alzheimer’s disease in your community? | |

| Access to care | Well, now some people don’t have a clear mind and the community don’t know. |

| The community to be educated about what, what’s going on, or what happened and they, they, they are functional people; need to have that great support system. | |

| As a person who has worked with Alzheimer’s, there is no real negative but there are emotional negatives. Many times family members are very unaccepting of that and they do not treat that person well when they find this out. And I would like to change that personally, but it is true. | |

| I think access to care can be a big problem. Especially for people who are undocumented if they don’t have routine care. So they might not get that screening. And it’s going to be stressful in the long term on the community for resources and family members. Absolutely. Participant Responses to Interview Questions | |

| Interview Questions: To Lay Members: “Please give me some suggestions for making it easier for older adults to be screened for Alzheimer’s disease” To Professionals: “What could people in your position do to make it easier for older adults to be screened earlier for Alzheimer’s disease?” | |

| The trust issue is everything here | Now in particular in rural areas or areas that don’t have the full spectrum of services it is extremely important to bring services to the community and to be available and, and start developing the trust in relationships so that persons know that they can come |

| I think that Alzheimer’s need to have a one to one contact. And you need to read the body language you know, it’s a lot of things | |

| Uh, well the culture in the Glades community is very close. People need to trust you. People need to know you, for they to be able to open up. It’s like it’s challenging to do a research here in the community. | |

| This community may surprise you. The issue is trust. If trust can be established it might work. | |

| The people here; you do need the contact, you need to kind of hold their hands, you know. | |

| And I think, um, you know, getting together with some of the community organizations | |

| Sounds like a very nice thing it’s just that … the trust issue is everything here. | |

| Education is really big | I think education is absolutely critical. Um, education and awareness. |

| Make sure that people are understanding | |

| It’s not even about acceptance but it’s like, you know, they understand it, they understand, | |

| But if someone tells you and helps you to understand and to know that because of this, this is why this is happening, then you know, you, you understand it better. And, and you embrace it I think a bit more. | |

| It’s best to know what’s, what’s going on with them at that moment. - And do we up-lift them or do we down them. | |

| It is important to know how the Alzheimer’s works with each and every one and it’s important to know what next step they need to take during Alzheimer’s or knowing about Alzheimer’s. | |

| Because we based on my basic knowledge about AD, um, it’s very important for me to educate people. | |

| Without education we’re not going to really make such an impact on people’s community. | |

| Education on this subject is the best. And that’s really the only way. Um, the other fear will go away with education and that would be the primary purpose that you would have, I would hope. | |

| Um, lack of knowledge is one of them. Not enough resources in the community. Education is really big. | |

| Identify Support Systems | Set up a relationship with them where as people come in they could be screened. I think that would improve access tremendously |

| I think public awareness, uh, is really important. Doing things like health fairs, getting that information out there to people is very important. | |

| Transportation to doctor’s office or whatever the case may be, even financial support may be needed. | |

| Think they appreciate whatever can be made available to them in ways that are accessible to them. | |

| Well I think that having that information available in your practice but also doing community outreach, doing health fairs, setting up information booths outside not just in the community health fairs but like going to local businesses, letting people know that information is available. | |

| Not only that there’s treatment but also a way to kind of help those type of patients | |

| First of all more data will be collected and that will allow for the politicians or people in the health field to come up with more decision more help, to help those people. | |

| Well, the preparation involves financial health-wise, family support and make all kinds of arrangements, necessary arrangements. | |

| I’ve never seen so many churches in such an you know kind of small geographic area. And I think you know, getting together with some of the community organizations that offer health fairs, and adding that as an additional service, I think would be really beneficial for that community. | |

| Yeah, having a nurse come here, that would help. | |

| I don’t know anything but those doctors told us what to do and where to come | |

| And I’m sure there’s a gap accessing services in the community so that persons can have social interaction and relieve caregiver distresses. | |

| I think the biggest barrier is how to access it whether it’s by transportation or where to go. | |

| So, if we had some kind of a program or we had a person to do screening I could help that person get patients to be screened. That wouldn’t be a problem. | |

| We could, uh, I don’t know, set up meetings in our church for folks or somebody to come out. To, uh, I guess, do a presentation to help people be more aware as to, you know, this disease. | |

| I think we could do some good presentations, some education. We could do some outreach in terms of our newsletter. There’s certain events that are happening, or any ongoing screening that’s available. | |

| It allows you to identify what other lifestyle you to changes even health, financially, emotionally and identify what support system do you need. | |

| A sentence being pronounced over their lives | Interview Question: “What fears do you have related to the subject of cognitive screening”? |

| Some people are afraid to find out, some people are afraid for other people to find out, you know | |

| No, I don’t have any fear because I be hoping what they said they working on a medication. | |

| Personally, yes, because I have family members who have, um, dementia or had dementia. And now those people are now passed. So there’s always, um, a fear that that will happen to your family member or to you. So I think the more information that’s available, personally and for the community, is important. | |

| They don’t, they just don’t worry about the future, you know | |

| Being afraid of the answers they might get | |

| No I have no fears. | |

| There was a time you know, before the Affordable Care Act, um, was upheld by the Supreme Court, people who might have been denied health insurance coverage because of the identification of certain types of illnesses. And so there was a hesitation, | |

| I think, a resistance to getting, you know, screened for things like that. I think that barrier is down, um, at least for the time being. | |

| We’ll see what the political landscape, you know, looks like moving forward but any more that barrier [fear of knowing AD dx] at least has been, I think, addressed because no longer can people be denied health care coverage on the basis of, you know, medical conditions they have. So I think those issues, um, come into play and I think there were people that didn’t necessarily want to go on the radar as, you know, having screened for something like Alzheimer’s. | |

| I think people generally are concerned about, afraid of and they fear things that they don’t know about or they don’t understand. And that’s why I think that education is so important, you know, to you to make sure that people are understanding and that it’s not, um, it’s not a sentence that’s being pronounced over you know, their lives. | |

Themes

From analyzing the data using the eight codes, two themes emerged that addressed the study’s purpose of gaining a greater understanding of influences on willingness to participate in cognitive screening in the target population. These two themes were (1) Trust is the essential component of connecting with Community, and (2) The Community recognizes the importance of knowledge in improving care. The first theme indicates that the researcher or educator must either be from the community or have been engaged in it long enough that he/she is recognized and trusted by the stakeholders. The second theme demonstrates the importance of providing resources to the Community; they believe that understanding can lead to action. A salient finding in the data that was derived from memo-ing was the word “appreciate”. It was mentioned four times by stakeholders in response to the question “So how do you think that residents would perceive knowing earlier that they had Alzheimer’s Disease? Upon inspection, “appreciation” was found to be a more powerful word than “thanking someone”. The interviewees used this term to indicate that persons would welcome knowledge about the diagnosis in many cases: “And then when they [patients] actually get into it [cognitive screening] they sort of appreciate that you asked about their memory, because if you identify something, then it’s very helpful.” “They are challenged sometimes I think in accessing care but I think they appreciate whatever can be made available to them in ways that are accessible to them.” “I think they’d be aprec. … would appreciate it and, um, instead of waiting until the last minute when nothing can be done. You know where you find it in earlier stages. You can work with it a little bit more or slow the process down.”

Credibility of results

Confidence in the trustworthiness of the study findings is the most important criterion of quality in qualitative research (Connelly & Peltzer, 2016; Cope, 2014; Polit & Beck, 2018). Trustworthiness points to the credibility and generalization of the results. For qualitative reporting, writing reflective notes and conducting member-checking are two methods to insure credibility (Connelly & Peltzer, 2016). In addition to the memo-ing discussed earlier, member-checking was conducted in this study to determine if the investigators’ findings were representative of their perceptions. All stakeholders were offered feedback in a second interview. Stakeholders were provided a summary of the findings and asked to write or call with comments. Of the eleven (55%) who provided feedback, the response was overwhelmingly favorable, with comments such as “education and trust are the keys”, “people here will indeed accept help if they think it will make a difference”, “there are a couple of doctors here who will help you in this”, and “people want to know so they can plan.” However, two of the stakeholders (the community nurse and an administrator) cautioned “when there are families, you have to get the families to understand that this will help”, and “families are the ones you have to work through.”

Quantitative results

Representative findings from the PRISM-PC results are presented below and in Table 2. Similar to previous investigations (Fowler et al., 2012; Fowler et al., 2015), the scale constructs identified included (1) the perceived harms of cognitive screening and (2) the acceptance of screening.

Perceived harms of screening

A minority of stakeholders indicated that they would be viewed less favorably by others if diagnosed with AD, such as being considered “stupid” or unable to communicate (9.5%), feeling “ashamed” or “embarrassed” (14.3%), or not taken seriously by family or friends (20%). About half of the respondents indicated that if their family members knew about an AD diagnosis, it would create financial (47.6%) or emotional distress (61.9%) for the family. Although a third of those interviewed indicated their belief that they would be depressed (33.3%) and even more would be anxious (42.9%) if they were aware of an AD diagnosis, 95% stated that they “would not give up on life.”

Acceptance of screening

Based on the stakeholder“s responses to the PRISM items, 81% indicated that they would want an examination annually to determine if they developed memory problems or AD. The majority (85%) of persons that had previously been screened would want to know if they were at higher risk of AD. All stakeholders responded that earlier cognitive testing would provide the opportunity for better treatment. Similarly, regardless of effects on the family or perceived stigma, 86% believed that family would be able to provide better care if they knew of an AD diagnosis earlier.

Discussion

This study investigated a group of ethnically diverse, rural south-central Florida stakeholder perceptions regarding cognitive screening. Four major findings emerged from evaluating the study results: (1) Fear was defined as the emotional and financial impact on families from knowing of the disease. Of note is that only the quantitative results revealed that this was especially concerning among those with more responsibility for family members, due to concerns of losing the ability to provide for their families - and therefore were hesitant to inform employers; (2) Regardless of the level of education or health literacy, type of ethnicity, or years in a rural area, community gatekeepers were strikingly similar in their desire for the community to be educated regarding cognitive screening; (3) Despite the economic or psychological concerns, family members would be supportive toward persons with dementia; (4) Support was defined in the qualitative findings as access to care, but support was synonymous with planning by the family and community in only the qualitative findings.

Stakeholders’ low level of education and health literacy were consistent with the large migrant populations found in the targeted area who often do not progress past middle or even elementary school. Neither caregiver status, years of formal education, health literacy level, or ethnic background negatively influenced perceptions of the need for cognitive screening. These findings are congruent with recent research by Boustani et al. (2008) and Fowler et al. (2012, 2015) who found that ethnicity did not hinder willingness to be screened, and caregivers were less likely to refuse screening than non-caregivers. In contrast to our findings, Fowler et al. (2015) identified that age was a factor; persons over age 70 were not as willing to be screened prior to an educational intervention. These studies and this current work highlight the need to increase awareness of the benefits of earlier detection in all groups.Almost all stakeholders (95%) in this ethnically diverse sample wanted to know about an AD diagnosis, which is in alignment with Neumann and colleagues (Neumann et al. 2001) sentinel public health survey that almost 90% of Americans would want to know if the cause of memory loss was AD, and in those aged 60 and over, 95% would want to know. In the current study, 97% of the interviewees stated that they would want their family members to see a provider for symptoms of memory loss to ascertain if the cause was AD. This is congruent with Green and associates’ (Green et al. 2015) study of urban and some ethnically diverse residents. The stakeholders who were informed of testing positive for the APOE4 gene, a genetic marker for increased AD risk, did not experience more anxiety or depression than those who were not informed.

Relating findings to the theoretical framework

Key findings related to the importance of family and community. Family was mentioned 27 times in the qualitative arm of this study. It is through family and/or community support that acculturation is most likely to occur (Herrmann et al., 2017). Community was the prevailing concept throughout the interviews, referred to over 40 times. Looking through the lens of the SCHBM by Sayegh and Knight (2013), family and community can be seen as a way to navigate past the barriers of lack of knowledge, acculturation, and care access.

The qualitative results demonstrated another area of importance to the stakeholders: culturally specific beliefs. For example, “cold in the brain” was a stakeholder phrase in this study. The researchers noted that this term to describe AD was also used by rural Appalachian residents during a study to investigate AD knowledge.51 Another example of culturally specific terminology was “we have to up them, not down them” when referring to supporting persons with AD. This statement suggested the belief that persons with dementia needed to maintain a sense of self-esteem. Applying the SCHBM (Sayegh & Knight, 2013) can result in providers engaging these culturally specific beliefs as a strength, rather than a barrier, to cognitive screening.

Many of the codes identified in the qualitative analysis were similar to items in the PRISM-PC (Boustani et al., 2008) survey. These topics included fear, education, planning, support, and detection by providers, which were mirrored in the stakeholder statements as “a sentence being pronounced over their whole lives”, “education is really big”, “identifying support systems”, “trust issue is everything here”, “access to care”, and “there is a cost to do that [screening]”. Addressing these concerns as guided by the SCHBM can provide a framework for cues to action (Sayegh & Knight, 2013), and are illustrated in Figure 1.

Additional findings

Findings from the PRISM-PC (Boustani et al., 2008) results added new information in that persons were concerned about the burden emotionally and financially on their families. This concern did not emerge in the open-ended interviews. Another difference found in the PRISM-PC but not in interviews was that stakeholders responded that they would be “depressed” or “sad” if they were diagnosed with AD. These terms did not surface in responses to the qualitative questions. Similarly, concerns about losing their health insurance or notifying employers of an AD diagnosis, which were items on the PRISM-PC, were not found in the qualitative interviews. Other than one reference to caregiver depression and another to caregiver anxiety, the stakeholders did not use these words in the open-ended interviews. The PRISM-PC (Boustani et al., 2008) also included specific questions regarding the type of testing the research subject would be willing to participate in and consequences of diagnosis, e.g. eventual nursing home placement. These topics did not emerge during the interviews, possibly due to the scope of the interview questions.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of this exploratory study included the diversity of the stakeholders’ positions, member-checking to support credibility of the results, the administration of a quantitative measure to add information that may have not been addressed in the qualitative inquiry, and the primary investigator’s previously established and trusted presence in the community. An important study limitation was the lower proportion of male participants and exclusion of potential stakeholders who did not speak or understand English. They could be the stakeholders who needed to have their perceptions and voices heard most. Other limitations of the qualitative inquiry included the small sample size, and use of a convenience sample of adults who agreed to be interviewed and may have a vested interest in expanding health care access. This threat was minimized by asking a wide variety of stakeholders to participate in the study. To gain the benefit of adding a mixed methods analysis using the quantitative PRISM-PC measure, future research would need to include a larger sample size of n = 150, to meet the recommended standards of 5-10 of stakeholders for every test item (Tappen, 2015).

In summary, findings from both the qualitative and quantitative data revealed the willingness to be informed of a dementia diagnosis even while considering potential associated burdens. Commitment of the community toward its members was only revealed through the qualitative exploration.

Research implications

Member checking identified the importance of including family members in plans for increasing awareness of the need for screening. It would be helpful to interview family members of older residents experiencing memory loss to discern their perceptions. Barriers to screening may be revealed only through the experience of being a caregiver for someone with dementia (Wiese et al., 2014). Targeting informal caregivers could inform future programs to improve access to cognitive screening. Future studies should also target diverse rural communities and include those who do not speak or comprehend English to identify specific barriers.

Practice implications

It is important for healthcare providers to be aware that cognitive screening is now a required component of the Annual Wellness Visit for Medicare/Medicaid patients. Education regarding the importance of cognitive screening and ways to conduct screening need to be incorporated into preparatory or continuing education for students and practitioners. An article is available that includes a review of the updated 2011 definition of Alzheimer’s disease and tools for conducting cognitive assessment (Wiese & Williams, 2015).

Determining dementia detection and treatment knowledge gaps and offering relevant education for both lay and provider members of rural communities is needed. Any plans to increase public awareness of the need for screening should include outreach to underserved families at schools and health fairs. This is important in light of a promising new technology to detect AD earlier through a simple and cost-effective retinal scan (Koronyo, et al., 2017).

Another knowledge gap emerged from results of the PRISM-PC (Boustani et al., 2008). Two-thirds of those interviewed did not understand the meaning of the term “Advance Directives” and only one of the 20 stakeholders had an Advance Directive. Education is also needed in this arena to prevent unnecessary costs associated with poor planning of terminal illness.

Conclusion

Analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data in this study revealed that diverse rural stakeholders, including those with language barriers and low levels of education, were supportive of memory screening. The importance of community in navigating sociocultural barriers emerged, as seen in the themes (1)“Trust is the essential component of connecting with Community”, and (2) “The Community recognizes the importance of knowledge in improving care. Codes included “a sentence being pronounced over the lives”, “keep everybody at home”, “Education is big”, the trust issues is everything here”, and “there is a cost to do that”. Results of the current study support optimism for improved early identification of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

Increasing AD detection and management is a directive of the National Alzheimer’s Plan Act (NAPA) (Khachaturian, Khachaturian, & Thies, 2012). The NAPA directive is strongly supported by the National Institute of Aging (NIA) and the Alzheimer’s Association. Their websites offer multiple detection and treatment resources, such as “Instruments to Detect Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults” (2012) and “New Diagnostic Criteria and Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease” (Alz.Org Research Center, 2015). Results of the current study indicate optimism for NAPA’s goal of preventing and effectively treating Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias by 2025 (Borson et al., 2016), characterized by one sakeholder’s statement; “Alzheimer’s disease is not a sentence that’s being pronounced over, you know, their lives.”

Table 3B.

Stakeholder sociodemographics; continuous variables.

| Total Sample n = 21 |

Professionals n = 16 |

Laypersons n = 5 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Age in Years | 58.2 | 15.4 | 76.85 | 7.89 | 73.6 | 7.01 |

| Education in Years | 14.4 | .9 | 10.9 | 3.13 | 8.4 | 5.37 |

| Years in Belle Glade | 30.1 | 21.9 | 4.85 | 4.73 | 61.2 | 14.3 |

| REALM Score | 4.95 | 3.62 | 5.20 | 3.00 | 0.5 | 1.00 |

Footnotes

Diclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abner EL, Jicha GA, Christian WJ, & Schreurs BG (2016). Rural-urban differences in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders diagnostic prevalence in Kentucky and West Virginia. The Journal of Rural Health, 32(3), 314–320. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler G, Lawrence BM, Ounpraseuth ST, & Asghar-Ali AA (2015). A survey on dementia training needs among staff at community-based outpatient clinics. Educational Gerontology, 41(12), 903–915. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2015.1071549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adu P (2015). Qualitative Data Analysis: When to Utilize Manual Coding or Software-aided Coding such as Nvivo, National Center for Academic & Dissertation Excellence (NCADE). The Chicago School of Professional Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 12(4), 459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2018). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 14(3), 367–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alz.Org Research Center (2015). New Diagnostic Criteria and Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease Retrieved from: http://www.alz.org/research/diagnostic_criteria/

- Amjad H, Roth DL, Samus QM, Yasar S, & Wolff JL (2016). Potentially unsafe activities and living conditions of older adults with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64, 1223–1232. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte J, Jackson TD, Wyka K, & Ikechi C (2017). Health effectiveness of community health workers as a diabetes self-management intervention. Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research, 14(4), 316–326. doi: 10.1177/1479164117696229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, Soltysik RC, Wolf MS, Ferreira RM, … Davis T (2007). Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Medical Care, 45(11), 1026–1033. doi: doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180616c1b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton SE, Roe B, Jack B, & McClelland B (2016). End of life care: the experiences of advance care planning amongst family caregivers of people with advanced dementia – A qualitative study. Dementia, 15(5), 958–974. DOI: 10.1177/1471301214548521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, & Bennett DA (2014). Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans: Risk factors and challenges for the future. Health Affairs, 33(4), 580–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04444.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JH, Lewis L, Blackwell AD, & Taylor M (2014). Early intervention in Alzheimer’s disease: A health economic study of the effects of diagnostic timing. BMC Neurology, 14(1), 101–101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Gamaldo AA, Teel A, Zonderman AB, & Wang Y (2014). Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 14, 643. doi: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fau.edu/10.1186/1471-2458-14-643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Boustani MA, Buckwalter KC, Burgio LD, Chodosh J, Fortinsky RH, … Phillips C (2016). Report on milestones for care and support under the US National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 12(3), 334–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boustani M, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, Fox C, Watson L, Hopkins J, … Hendrie HC (2008). Measuring primary care patients’ attitudes about Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(8), 812–820. doi: 10.1002/gps.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassarino M, O’Sullivan V, Kenny RA, & Setti A (2016). Environment and cognitive aging: A cross-sectional study of place of residence and cognitive performance in the Irish longitudinal study on aging. Neuropsychology, 30(5), 543–557. doi: 10.1037/neu0000253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly LM, & Peltzer JN (2016). Underdeveloped themes in qualitative research: Relationship with interviews and analysis. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 30(1), 52–57. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contador I, Bermejo-Pareja F, Puertas-Martin V, & Benito-Leon J (2015). Childhood and adulthood rural residence increases the risk of dementia: NEDICES Study. Current Alzheimer Research, 12(4), 350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins H (2004). Collins English Dictionary. Glassgow: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Cope DG (2014). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(1):89–91. Doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.89-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dale W, Hemmerich J, Hill EK, Hougham GW, & Sachs GA (2008). What correlates with the intention to be tested for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in healthy older adults? Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 22(2), 144–152. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318161103c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale W, Hougham GW, Hill EK, & Sachs GA (2006). High interest in screening and treatment for mild cognitive impairment in older adults: A pilot study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(9), 1388–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00852.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn RF, & Ikram MA (2014). Cardiovascular risk factors and future risk of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Medicine, 12(1), 130–130. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0130-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirovic J, Prineas R, Loewenstein D, Bean J, Duara R, Sevush S, & Szapocznik J (2003). Prevalence of dementia in three ethnic groups: The South Florida program on aging and health. Annals of epidemiology, 13(6), 472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNapoli EA, Wu B, & Scogin F (2014). Social isolation and cognitive function in Appalachian older adults. Research on Aging, 36(2), 161–179. doi: 10.1177/0164027512470704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Padovani A, Scheltens P, Rossi A, & Dell’Agnello G (2016). Timely diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: A literature review on benefits and challenges. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 49(3), 617–631. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervin K, Pallant J, Terry DR, Bourke L, Pierce D, & Glenister K (2015). A descriptive study of health, lifestyle and sociodemographic characteristics and their relationship to known dementia risk factors in rural Victorian communities. AIMS Medical Science, 2(3), 246–260. Article · August 2015. doi: 10.3934/medsci.2015.3.246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fahs PS, Pribulick M, Williams IC, James GD, Rovynak V, & Seibold-Simpson SM (2013). Promoting heart health in rural women. The Journal of Rural Health, 29(3), 248–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler NR, Boustani MA, Frame A, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, Gao S, … Hendrie HC (2012). Effect of patient perceptions on dementia screening in primary care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(6), 1037–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-541503991.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler NR, Perkins AJ, & Turchan HA (2015). Older primary care patients’ attitudes and willingness to screen for dementia. Journal of Aging Research, 1, 7. doi: 10.1155/2015/423265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RC, Christensen KD, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, Whitehouse PJ, Royal CD, …, Fasaye GA (2015). A randomized noninferiority trial of condensed protocols for genetic risk disclosure of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 11(10), 1222–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann L, Welter E, Leverenz J, Lerner A, Udelson N, Kanetsky C, & Sajatovic M (2017). A systematic review of Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia stigma research: How might we move the stigma dial?. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(3), S128. Doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.01.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell J, Soyinka CO, Parker M, Jarrett R, Roberts D, Dorbin C, & Hu W (2016). Knowledge and attitudes in Alzheimer’s disease in a cohort of older African Americans and Caucasians. American. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementiasr, 31(4), 361–367. doi: 10.1177/1533317515619037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C-C, Chung C-M, Leu H-B, Lin L-Y, Chiu C-C, Hsu C-Y, … Chan W-L (2014). Diabetes mellitus and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A nationwide population-based study. PloS One, 9(1), e87095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imoisili OE, Levinsohn E, Pan C, Howell BA, Streiter S, & Rosenbaum JR (2017). Discrepancy between patient health literacy levels and readability of patient education materials from an electronic health record. HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice, 1(4), e203–e207. 10.3928/24748307-20170918-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturian KS, Khachaturian AS, & Thies W (2012). The draft “National Plan” to address Alzheimer’s disease-National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA). Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 8(3), 234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz(2012).04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson A, & Meit M (2017). Rural America: aging faster, with fewer resources. Aging Today, 38(5), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Koronyo Y, Biggs D, Barron E, Boyer DS, Pearlman JA, Au WJ, … Koronyo-Hamaoui M (2017). Retinal amyloid pathology and proof-of-concept imaging trial in Alzheimer’s disease. JCI Insight, 2(16). doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas K, & D’Enbeau S (2013). Moving Beyond Themes. Departures in Critical Qualitative Research, 2(2), 213–227. doi: 10.1525/qcr.2013.2.2.213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lines LM, Sherif NA, & Wiener JM (2014). Racial and ethnic disparities among individuals with Alzheimer’s disease in the United States: A literature review. US Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. RTI Press Publication, Vol RR-0024-1412; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston S, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C … Mudadem N (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet, 390(10113), 2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Kelly S, Khan A, Cullum S, Dening T, Rait G, … Lafortune L (2015). Attitudes and preferences towards screening for dementia: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattos MK, Snitz BE, Lingler JH, Burke LE, Novosel LM, & Sereika SM (2017). Older Rural-and Urban-Dwelling Appalachian adults with mild cognitive impairment. The Journal of Rural Health, 33(2), 208–216. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, & Whitmer RA (2016). Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 12(3), 216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta KM, & Yeo GW (2017). Systematic review of dementia prevalence and incidence in United States race/ethnic populations. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 13(1), 72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meit M, Knudson A, Gilbert T, Yu ATC, Tanenbaum E, Ormson E, & Popat MS (2014). The 2014 update of the rural-urban chart-book. Rural Health Reform Policy Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE, Morris JC, Berg-Weger M, Borson S, Carpenter BD, del Campo N, … Ganguli M (2015). Brain health: The importance of recognizing cognitive impairment: An IAGG consensus conference. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 16(9), 731–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Aging. (2017). Instruments to detect cognitive impairment in older adults. Retrieved from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/assessing-cognitive-impairment-older-patients#how%20is

- Neumann PJ, Hammitt JK, Mueller C, Fillit HM, Hill J, Tetteh NA, & Kosik KS (2001). Public attitudes about genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease. Health Affairs, 20(5), 252–226. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.5.252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit & Beck (2018). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia: Wolters Klewer. [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, & Ferri CP (2013). The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 9(1), 63–75.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikard RV, Thompson MS, McKinney J, & Beauchamp A (2016). Examining health literacy disparities in the United States: a third look at the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). BMC Public Health, 16(1), 975. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3621-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, & Becker MS (1988). Social learning theory and the health belief model., Health Education & Behavior, 15(2), 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rural Economic Development Initiative. (2017). Rural Areas of Opportunity. State of Florida Department of Economic Opportunity. Retrieved from: http://www.floridajobs.org/business-growth-and-partnerships/rural-and-economic-development-initiative/rural-areas-of-opportunity

- Saldaña J (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]