Abstract

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a severe, ongoing, novel pandemic that emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. As of January 21, 2021, the virus had infected approximately 100 million people, causing over 2 million deaths. This article analyzed several time series forecasting methods to predict the spread of COVID-19 during the pandemic’s second wave in Italy (the period after October 13, 2020). The autoregressive moving average (ARIMA) model, innovations state space models for exponential smoothing (ETS), the neural network autoregression (NNAR) model, the trigonometric exponential smoothing state space model with Box–Cox transformation, ARMA errors, and trend and seasonal components (TBATS), and all of their feasible hybrid combinations were employed to forecast the number of patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and the number of patients hospitalized in the intensive care units (ICU). The data for the period February 21, 2020–October 13, 2020 were extracted from the website of the Italian Ministry of Health (www.salute.gov.it). The results showed that (i) hybrid models were better at capturing the linear, nonlinear, and seasonal pandemic patterns, significantly outperforming the respective single models for both time series, and (ii) the numbers of COVID-19-related hospitalizations of patients with mild symptoms and in the ICU were projected to increase rapidly from October 2020 to mid-November 2020. According to the estimations, the necessary ordinary and intensive care beds were expected to double in 10 days and to triple in approximately 20 days. These predictions were consistent with the observed trend, demonstrating that hybrid models may facilitate public health authorities’ decision-making, especially in the short-term.

Keywords: COVID-19, Outbreak, Italy, Hybrid forecasting models, ARIMA, NNAR, TBATS

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a severe, ongoing, novel pandemic that officially emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. As of January 21, 2021, it had affected 219 countries and territories with almost 100 million cases and over 2 million deaths [77]. At the time of writing, the countries most significantly affected include both advanced and developing countries, such as Brazil, France, India, Italy, Russia, Spain, the UK, and the US. From October to December 2020, several European countries, including Italy, saw a worrisome surge of COVID-19 infections.

Italy was the first European country to be severely impacted by COVID-19, and it remained one of the main epicenters of the pandemic for approximately 2 months, i.e., from mid-February 2020 to mid-April 2020. After that first peak, the pandemic curve progressively decreased until mid-August 2020. However, the spread of infection accelerated again in the late Summer and early Fall of 2020, and this second surge continues today. As of January 21, 2021, Italy has suffered 84,202 deaths and 2,428,221 cases.

The likelihood of new and consecutive COVID-19 waves is real, and efforts to study the pandemic’s trajectory are imperative to purchase medical devices and healthcare facilities and to manage health centers, clinics, hospitals, and ordinary and intensive care beds.

Thus, the first goal of this paper is to provide short-term and mid-term forecasts for the number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during the second wave of COVID-19 infections, i.e., during the period after October 13, 2020. COVID-19-related hospitalization trends offer a clear picture of the overall pressure on the national healthcare system. Moreover, models fitted to hospitalized patients are usually more reliable and accurate than models fitted to confirmed cases [30].1 The paper’s second goal is to compare and investigate the accuracy of several statistical methods.

In particular, I estimated four time series forecast techniques and all of their feasible hybrid combinations: the autoregressive moving average (ARIMA) model, innovations state space models for exponential smoothing (ETS), the neural network autoregression (NNAR) model, and the trigonometric exponential smoothing state space model with Box–Cox transformation, ARMA errors, and trend and seasonal components (TBATS).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. “Related literature” reviews the relevant literature while “Materials and methods” presents the data used in the analysis and discusses the empirical strategy. “Evaluation metrics” presents the evaluation metrics used to measure the performance of the models. “Results and discussion” discusses the main findings and policy implications. Finally, “Conclusions” provides some conclusive considerations.

Related literature

From the beginning of 2020, an increasing body of literature has employed various approaches to forecast the spread of the COVID-2019 outbreak [9, 22, 26, 58, 73, 78, 79, 83, 85]. The most frequently used were ARIMA models [3, 8, 14, 62], ETS models [13, 44], artificial neural network (ANN) models [55, 75], TBATS models [68, 71], models derived from the susceptible–infected–removed (SIR) basic approach [22, 26, 58, 78, 85], and hybrid models [15, 29, 68, 69]. The implementation and comparison of these approaches—with the exception of mechanistic–statistical models (such as SIR)—represents the core of this paper.

Ala’raj et al. [2] utilized a dynamic hybrid model based on a modified susceptible–exposed–infected–recovered–dead (SEIRD) model with ARIMA corrections of the residuals. They provided long-term forecasts for infected, recovered, and deceased people using a US COVID-19 dataset, and their model had a remarkable ability to make accurate predictions. Using a nonseasonal ARIMA model, Ceylan [14] made short-term predictions of cumulative confirmed cases after April 15, 2020, for France, Italy, and Spain. The forecasts showed low mean absolute percentage errors (MAPE) and seemed to be sufficiently reliable and suitable for the short-term epidemiological analysis of COVID-19 trends.

Hasan [29] proposed a hybrid model that incorporates ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD) and neural networks to forecast real-time global COVID-19 cases for the period after May 18, 2020. The analysis showed that the ANN-EEMD approach was quite promising and outperformed traditional statistical methods, such as regression analysis and moving average.

Ribeiro et al. [65] provided short-term estimates of COVID-19 cumulative confirmed cases in Brazil by employing multiple approaches and selecting several models, such as ARIMA, cubist regression (CUBIST), random forest (RF), ridge regression (RIDGE), support vector regression (SVR), and stacking-ensemble learning (SEL). The models’ reliabilities were evaluated based on the improvement index, mean absolute error (MAE), and symmetric MAPE criteria. The analysis demonstrated that SVR and SEL performed best, but all models exhibited good forecasting performances.

Using ARIMA, TBATS, their statistical hybrid, and a mechanistic mathematical model combining the best of the previous models, Sardar et al. [68] attempted to forecast daily COVID-19 confirmed cases across India and in five different states (Delhi, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu) from May 17, 2020, until May 31, 2020. The ensemble model showed the best prediction skills and suggested that COVID-19 that daily COVID-19 cases would significantly increase in the considered forecast window and that lockdown measures would be more effective in states with the highest percentages of symptomatic infection.

Wieczorek et al. [75] implemented deep neural network architectures, which learned by using a Nesterov-accelerated adaptive moment (Nadam) training model, to forecast cumulative confirmed COVID-19 cases in several countries and regions. The predictions, which referred to different time windows, revealed that the models had an extremely high level of accuracy (approximately 87.7% for most regions but, in some cases, reaching almost 100%).

Talkhi et al. [71] attempted to forecast the number of COVID-19 confirmed infections and deaths in Iran between August 15, 2020, and September 14, 2020, using several single and hybrid models. The extreme learning machine (ELM) and hybrid ARIMA–NNAR models were the most suitable for forecasting confirmed cases, while the Holt–Winters (HW) approach outperformed the others in predicting death cases.

Finally, Table 1 reports 30 international studies that utilized single or hybrid ARIMA, ETS, neural network, and TBATS models to forecast the transmission patterns of COVID-19 across the world.

Table 1.

30 selected international studies that utilized single or hybrid ARIMA, ETS, neural network, and TBATS models.

| Authors | Data | Method | Country/region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abotaleb [1] | Confirmed, deceased, and recovered | ARIMA and EGM | China, Italy, and the US |

| Ala’raj et al. [2] | Confirmed, deceased, and recovered | SEIRD-ARIMA | US |

| Alzahrani et al. [3] | Confirmed | ARIMA | Saudi Arabia |

| Aslam [4] | Active, confirmed, deceased, and recovered | KF-ARIMA, HW, and SutteARIMA | Pakistan |

| Awan and Aslam [5] | Confirmed | ARIMA | France, Germany, Italy, and Spain |

| Cao et al. [13] | Confirmed | ARIMA, ARIMAX, ETS, and SEIQDR | China |

| Ceylan [14] | Confirmed | ARIMA | France, Italy, and Spain |

| Chakraborty and Ghosh [15] | Confirmed | ARIMA–WBF | Canada, France, India, and South Korea |

| Dhamodharavadhani et al. [18] | Deceased | RBFNN, GRNN, NARNN, and PNN | India |

| Fantazzini [23] | Confirmed | ARIMA, ARIMAX, ETS, HVAR, SIR, and VAR | 158 countries |

| Hasan [29] | Confirmed | ANN-EEMD | World (aggregate) |

| Ilie et al. [41] | Confirmed | ARIMA | nine countries |

| Joseph et al. [44] | Confirmed | ARIMA, ETS, INGARCH, and hybrid | nine countries |

| Katoch and Sindhu [45] | Confirmed | ARIMA | India |

| Kırbaş et al. [48] | Confirmed | ARIMA, LSTM, and NARNN | Eight European countries |

| Melin et al. [55] | Confirmed | ME-ANN | Mexico |

| Moftakhar and Seif [56] | Confirmed | ARIMA | Iran |

| Papastefanopoulos et al. [61] | Confirmed | ARIMA, DeepAR, FB, HWAAS, and N-Beats | 10 countries |

| Perone [63] | Confirmed and deceased | ARIMA | Italy, Russia, and the US |

| Ribeiro et al. [65] | Confirmed | ARIMA, CUBIST, RF, RIDGE, SVR, and SEL | Brazil |

| Sardar et al. [68] | Confirmed | ARIMA, TBATS, hybrid, and mechanistic model | India |

| Sahai et al. [67] | Confirmed | ARIMA | Brazil, India, Russia, Spain, and the US |

| Singh et al. [69] | Deceased | ARIMA–WBF | France, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US |

| Wang et al. [74] | Confirmed and deceased | ARIMA and ETS | India, Russia, the UK, and the US |

| Wieczorek et al. [75] | Confirmed | ANN | Many countries/regions |

| Yonar et al. [80] | Confirmed | ARIMA and B/W LES | G8 countries |

| Ganiny and Nisar [25] | Confirmed | ARIMA | India |

| Katris [46] | Confirmed | ARIMA, ETS, FFANN, MARS, their combinations, and SIR | Greece |

| Lee et al. [51] | Confirmed | ARIMA | South Korea |

| Talkhi et al. [71] | Confirmed and deceased | ARIMA, BSTS, ELM, HW, MLP, NNAR, Prophet, TBATS, and hybrid | Iran |

ANN artificial neural network, ARIMA autoregressive integrated moving average, ARIMAX ARIMA with exogenous variables, BSTS Bayesian structural time-series, B/W LES Brown/Holt linear exponential smoothing method, CUBIST cubist regression, DeepAR probabilistic forecasting with autoregressive recurrent networks, EEMD ensemble empirical model decomposition, EGM exponential growth model, ELM extreme learning machines, ETS innovations state space models for exponential smoothing, FB Facebook’s prophet, FFANN feed-forward artificial neural network, GRNN generalized regression neural network, HVAR hierarchical vector autoregression, HW Holt–Winters method, HWAAS Holt–Winters additive model, INGARCH integer-valued generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedastic, KF Kalman filter, LSTM long-short term memory, MARS multivariate adaptive regression splines, ME-ANN multiple ensemble artificial neural network, MLP multilayer perceptron, NARNN nonlinear autoregressive neural network, N-Beats neural basis expansion analysis, NNAR neural network autoregression, PNN probabilistic neural network, RBFNN radial basis function neural network, RF random forest, RIDGE ridge regression, SEIQDR susceptible–infected but undetected–infected quarantined–suspected–discharged, SEIRD susceptible–exposed–infected–recovered–dead, SEL stacking-ensemble learning, SIR susceptible–infected–recovered, SutteARIMA α-Sutte Indicator and ARIMA, SVR support vector regression, TBATS trigonometric exponential smoothing state space model with Box–Cox transformation, ARMA errors trend and seasonal components, VAR vector autoregression, WBF Wavelet-based forecasting

Materials and methods

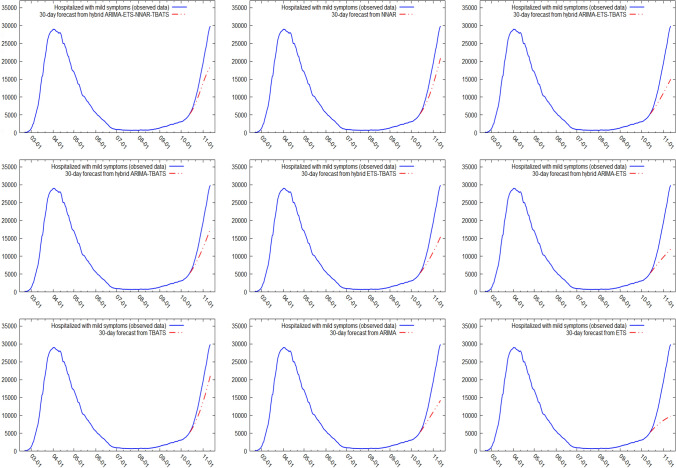

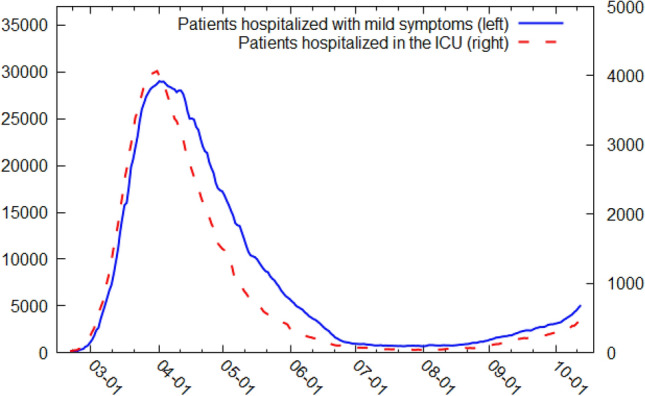

The data used in this article, which include 236 observations, referred to the real-time number of COVID-19 hospitalizations of patients with mild symptoms and patients assigned to the ICU in Italy from February 21, 2020, to October 13, 2020. I extracted the data from the official Italian Ministry of Health’s website (www.salute.gov.it). The confirmed COVID-19-related hospitalization trends appear in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and in the ICU from February 21, 2020 to October 13, 2020.

Source: Italian Ministry of Health [43]

The data showed that the number of COVID-19 patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and the number of COVID-19 patients assigned to the ICU reached an initial peak on April 4, 2020. They then followed a downward trend until mid-August before accelerating again from the end of September 2020 to mid-October 2020. Recognizing that the use of only one model is never wise and may lead to unreliable forecasts [68], I computed the forecasts by employing different statistical techniques and their combinations. Specifically, linear ARIMA models, ETS models, linear and nonlinear NNAR models, TBATS models, and their feasible hybrid combinations were examined.

ARIMA models, which were first proposed by Box and Jenkins [11], represent one of the most widely used frameworks for epidemic/pandemic and disease time series predictions [66, 84]. Considering only the linear trend of a time series, they are able to capture both nonseasonal and seasonal patterns of that series. The following should be noted regarding the nonseasonal component of ARIMA models: (i) the autoregressive (AR) process aims to forecast a time series using a linear combination of its past values; (ii) the differencing (I) is required to make the time series stationary by removing (or mitigating) trend or seasonality (if any), and (iii) the moving average (MA) process aims to forecast future values using a linear combination of previous forecast errors. The seasonal component is similar to the nonseasonal component, but implies backshifts of the seasonal period, i.e., adding the seasonal parameters to the AR, I, and MA components, which allows the model to handle most of the seasonal patterns in the real-world data. Therefore, the final seasonal model can be denoted as ARIMA (p,q,d)(P,Q,D)m, where m is the seasonal period and the lowercase and uppercase letters indicate the number of nonseasonal and seasonal parameters for each of its three components, respectively [34], Sect. 8).

The ETS class of models was introduced in the late 1950s [12, 31, 76] to consider different combinations of trend and seasonal components. The basic ETS model consists of two main equations: a forecast equation and a smoothing equation. By integrating these two equations into an innovation state space model, which may correspond to the additive (A) or multiplicative (M) error assumption, it is possible to obtain an observation/measurement equation and a transition/state equation, respectively.2 The first equation describes the observed data while the second equation describes the behavior of the unobserved states. The states refer to the level, trend, and seasonality. The trend and seasonal components may be none (N), additive (A), additive damped (Ad),3 or multiplicative (M), resulting in a wide range of model combinations. The final model assumes the form of a three-character string (Z,Z,Z), where the first letter identifies the error assumption of the state space model, the second letter identifies the trend type, and the third letter identifies the season type. These models are able to produce a time series forecast by using the weighted average of its past values and adding more weight to recent observations [34], Sect. 7, [40].

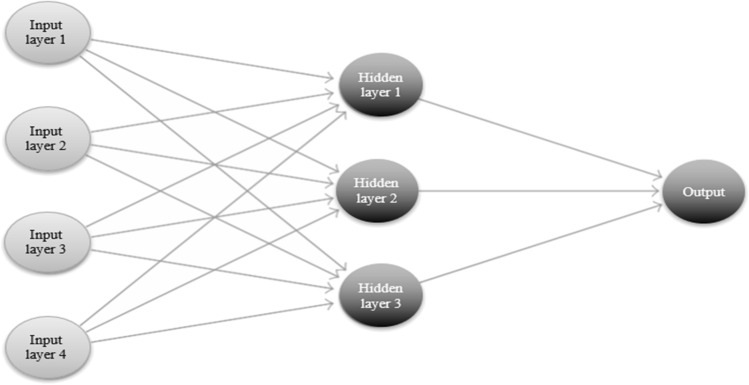

NNAR models can be viewed as a network of neurons or nodes that depict complex nonlinear relationships and functional forms. In a basic neural network framework, the neurons are organized in two layers: (i) the bottom layer identifies the original time series, and (ii) the top layer identifies the predictions. The resulting model is equivalent to a simple linear regression and becomes nonlinear only when an intermediate layer with “hidden neurons” is included. For seasonal data, NNAR models can be described with the notation NNAR (p,P,k)m, where m is the seasonal period, p denotes the number of nonseasonal lagged inputs for the linear AR process, P represents the seasonal lags for the AR process, and k indicates the number of nodes/neurons in the hidden layer [34], Sect. 11.3).

Finally, TBATS models are a class of models that combine different approaches: trigonometric terms for modeling seasonality, Box–Cox transformation [10] for addressing heterogeneity, ARMA errors for addressing short-term dynamics, damping (if any) trends, and seasonal components. Therefore, TBATS models have several properties: (i) they deal well with very complex seasonal patterns, which might, for example, exhibit daily, weekly, and annual patterns simultaneously; (ii) they are able to consider time series nonlinear patterns, and iii) they can handle any type of autocorrelation in the residuals [34], Sect. 11.1, [71].

The combination of different times series forecast methods maximizes the chance of capturing seasonal, linear, and nonlinear patterns [60, 82] and is especially useful for predicting real-world phenomena, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which are characterized by complex dynamics [7]. Well established from the seminal work of Bates and Granger [6], combining techniques with unique properties could allow models to achieve better performance and forecast accuracy.4 The models were calculated by using the following analytical procedures:

ARIMA models were detected by applying the “auto.arima()” function included in the package “forecast” (in the R environment) and developed by Hyndman and Khandakar [35]. This function followed sequential steps to identify the best model, i.e., the number of p parameters of the autoregressive process (AR), the order i of differencing (I), the number of q parameters of the MA, and the number of the parameters of the seasonal component. It combined unit root tests5 and the minimization of the following estimation methods: the bias-corrected Akaike’s information criterion (AICc)6 and the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). The unit root tests identified the order of differencing while the AICc and the MLE methods identified the order and the values of the parameters (respectively) of the seasonal and nonseasonal AR and MA processes;

ETS models were identified by using the “ets()” function included in the package “forecast” (in the R environment) and developed by Hyndman et al. [39].7 In particular, I applied the Box–Cox [10] transformation to the data before estimating the model and then used the AICc metric to determine if the trend type was damped or not. The final three-character string identifying method (Z,Z,Z) was selected automatically;

NNAR models were identified via the “nnetar()” function included in the package “forecast” (in the R environment) written by Hyndman [33].8 I proceeded as follows: (i) first, the Box–Cox transformation [10] was applied to the data before estimating the model; (ii) second, the optimal number of nonseasonal p lags for the AR(p) process was obtained by using the AICc metric; (iii) third, the seasonal P lags for the AR process were set to 19; and (iv) finally, the optimal number of neurons was identified using the formula [34], Sect. 11.3);

TBATS models were identified using the “tbats()” function included in the package “forecast” (in the R environment) as described in De Livera et al. [17]. The optimal Box–Cox transformation parameter, ARMA (p,q) order, damping parameter, and number of Fourier terms were selected using the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) metric;10

Hybrid models were identified via the “hybridModel()” function included in the “forecastHybrid” package (in the R environment) developed by Shaub and Ellis.11 The individual time series forecasting methods were combined as follows: (i) first, the Box–Cox power transformation [10] was applied to the inputs to increase the plausibility of the normality assumption; and (ii) then, the individual models were combined using both equal weights and cross-validated errors (“cv.errors”), which gave greater weight to the models that performed relatively better. In fact, since the best weighting procedure has not been established, I adopted a parsimonious approach and chose the one that performed better. Specifically, I tested the overall goodness-of-fit of all models with four common forecast accuracy measures: MAE, MAPE, mean absolute scaled error (MASE), and root mean square error (RMSE).

The estimated basic equation for the ARIMA was the following [16]:

| 1 |

where is the second difference operator, indicates the predicted values, p is the lag order of the AR process, is the coefficient of each parameters p, q is the order of the MA process, is the coefficient of each parameter q, and denotes the residuals of the errors at time t.

The estimated equations for the basic ETS (A,N,N) model with additive errors were the following [34], Sect. 7):

| 2 |

| 3 |

where is the new estimated level, denotes each one-step-ahead prediction for time t+1 which results from the weighted average of all the observed data, is the smoothing parameter, which controls the rate of decrease of the weights, and is the error at time t. Hence, each forecasted observation is the sum of the previous level and an error, and each type of error, additive or multiplicative, corresponds to a specific probability distribution. For a model with additive errors, as is this case here, errors are assumed to follow a normal distribution. Thus, Equations (2) and (3), respectively, can be rewritten as follows:

| 4 |

| 5 |

Equations (4) and (5) represent the innovation state space models that underlie the exponential smoothing methods.

The basic form of the neural network autoregression equation was the following [34], Sect. 11.3):

| 6 |

where indicates the predicted values, is a vector containing the lagged values of the observed data, f is the neural network with n hidden neurons in a single layer, and is the error at time t. A simple graphical example of a nonlinear neural network is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A neural network with four inputs and an intermediate layer with three hidden neurons

Finally, the basic equation of the TBATS model took the following form [17]:

| 7 |

where indicates the Box–Cox transformation parameter (ω) applied to the observation at time t, is the local level, is the damped trend, b is the long-run trend, T denotes the seasonal pattern, is the ith seasonal component,12 denotes the seasonal periods, and indicates an ARMA (p,q) process for residuals.

Evaluation metrics

The main metrics used to compare the performances of the single and hybrid prediction models were MAE, MAPE, MASE, and RMSE. The formulae used to calculate each of these metrics appear below (Eqs. 8–11):

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

where n represents the number of observations, denotes the actual values, and indicates the predicted values. Specifically, MAE and RMSE are both scale-dependent measures, although based on different errors. MAE is easier to interpret because minimizing it leads to predictions of the median, while minimizing RMSE leads to predictions of the mean. In fact, if the first metric is based on absolute errors, the second is based on squared errors. MAPE is probably the most widely employed error measure [27, 47], and unlike MAE and RMSE, it is not scale-dependent because it is based on percentage errors. Thus, it has the advantage of being a unit-free metric. However, it also requires some critical considerations. For example, it can lead to biased forecasts because it gives infinite or undefined results when one or more time series data point equals 0, and it puts a heavier penalty on negative errors (i.e., when predicted values are higher than actual values) than on positive errors. Finally, MASE, which was proposed by Hyndman and Koehler [36], is a scale-free error metric and probably the most versatile and reliable measure of forecast accuracy. It is superior to MAPE in that it does not give infinite or undefined values and can be used to compare forecast accuracy both on single and multiple time series.13 Since each model thus entails specific strengths and disadvantages, I opted for the prudent approach—evaluating the output of all of them.

Results and discussion

Table 2 reports the best selected parameters for the single models14 while Tables 3 and 4 include the forecast accuracy measures for the single and hybrid models.15 For patients hospitalized with mild symptoms (Table 2), the optimal single models were the seasonal ARIMA (1,2,3) (0,0,1)7, ETS (A,Ad,N),16 NNAR (7,1,4)7, and TBATS (0.428, {2,2}, 1, {< 7,2 >}).17 For patients hospitalized in the ICU (Table 2), the optimal single models were the seasonal ARIMA (1,2,2)(0,0,1)7, ETS (A,A,N),18 NNAR (6,1,4)7, and (T)BATS (0.427,{0,0},1,−).19 The hybrid models were derived by combining the optimal single models with equal weights, which proved to be more suitable than weights based on error values.20

Table 2.

Structure of the single models for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and in the ICU

| Models | AICc | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Patients hospitalized with mild symptoms | ||

| ARIMA | 3170.61 | Seasonal (1, 2, 3) (0, 0, 1)7 |

| ETS | 3846.92 | (A, Ad, N) |

| NNAR | – | (7, 1, 4)7 |

| TBATS | 3550.91 | (0.428, {2,2}, 1, {< 7,2 >}) |

| Patients hospitalized in the ICU | ||

| ARIMA | 2106.46 | Seasonal (1, 2, 2) (0, 0, 1)7 |

| ETS | 2775.88 | (A, A, N) |

| NNAR | – | (6, 1, 4)7 |

| (T)BATS | 2506.27 | (0.427, {0,0}, 1, –) |

Notes: TBATS models were chosen using AIC metric

Table 3.

Forecast accuracy measures for the single and hybrid models (patients hospitalized with mild symptoms)

| Models | MAE | MAPE | MASE | RMSE | ACF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA | 116.2616 | 2.6125 | 0.0631 | 204.8225 | − 0.0064 |

| ETS | 121.7029 | 4.3186 | 0.066 | 219.6733 | 0.0787 |

| NNAR | 111.0185 | 1.9759 | 0.0602 | 195.4126 | − 0.051 |

| TBATS | 115.428 | 2.8267 | 0.0626 | 204.2566 | 0.1902 |

| A–E | 115.0882 | 3.4033 | 0.0624 | 207.1205 | 0.0234 |

| A–N | 105.4098 | 2.1634 | 0.0572 | 184.3577 | − 0.0706 |

| A–T | 113.5426 | 2.6625 | 0.0616 | 200.8143 | 0.0803 |

| E–N | 107.3794 | 2.1219 | 0.0583 | 191.0452 | − 0.037 |

| E–T | 114.7241 | 3.4622 | 0.0622 | 204.5928 | 0.0886 |

| N–T | 104.7705 | 2.0966 | 0.0568 | 183.9314 | 0.0228 |

| A–E–N | 108.655 | 2.1419 | 0.059 | 193.672 | − 0.0355 |

| A–E–T | 113.0137 | 3.1372 | 0.0613 | 202.3212 | 0.0553 |

| A–N–T | 106.6527 | 2.1255 | 0.0579 | 189.0073 | 0.0579 |

| E–N–T | 108.3242 | 2.0805 | 0.0588 | 192.7942 | 0.0146 |

| A–E–N–T | 108.8197 | 2.1105 | 0.059 | 194.1662 | 0.006 |

Notes: A ARIMA, E ETS, N NNAR, T TBATS. Hybrid models were combined using equal weights

Table 4.

Forecast accuracy measures for the single and hybrid models (patients hospitalized in the ICU)

| Models | MAE | MAPE | MASE | RMSE | ACF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA | 12.5828 | 3.5411 | 0.0495 | 21.1697 | 0.0375 |

| ETS | 13.3832 | 3.59 | 0.0527 | 22.8157 | 0.0181 |

| NNAR | 11.6316 | 2.8082 | 0.0458 | 19.2895 | − 0.1636 |

| TBATS | 14.226 | 3.5832 | 0.056 | 24.2076 | 0.3122 |

| A–E | 12.5388 | 3.47 | 0.0493 | 21.5479 | 0.0072 |

| A–N | 11.4917 | 3.0443 | 0.0452 | 18.7476 | − 0.0513 |

| A–T | 12.8579 | 3.4874 | 0.0506 | 21.953 | 0.159 |

| E–N | 11.9035 | 3.064 | 0.0468 | 19.5496 | − 0.0947 |

| E–T | 13.3764 | 3.5436 | 0.0526 | 22.9583 | 0.1504 |

| N–T | 11.9856 | 2.9767 | 0.0472 | 19.695 | 0.0627 |

| A–E–N | 11.8861 | 3.0595 | 0.0468 | 19.8477 | − 0.0521 |

| A–E–T | 12.4876 | 3.3605 | 0.0491 | 21.3983 | 0.1502 |

| A–N–T | 12.0046 | 3.009 | 0.0472 | 19.9841 | 0.0474 |

| E–N–T | 12.383 | 3.0362 | 0.0487 | 20.7628 | 0.0377 |

| A–E–N–T | 12.188 | 3.0256 | 0.048 | 20.538 | 0.0277 |

Notes: A ARIMA, E ETS, N NNAR, T TBATS. Hybrid models were combined using equal weights

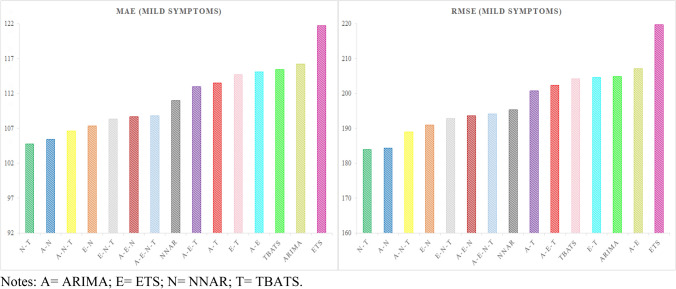

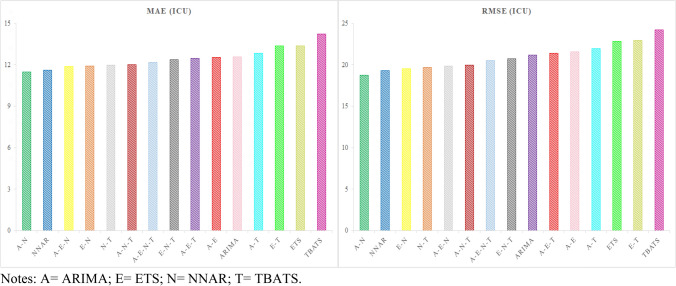

In particular, for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms, the most accurate single model was NNAR, followed by seasonal ARIMA, while the best hybrid model was NNAR–TBATS, followed by ARIMA–NNAR, and ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS. For patients hospitalized in the ICU, the best single model was NNAR, followed by ARIMA, while the best hybrid model was ARIMA–NNAR, followed by ARIMA–ETS–NNAR, and ETS–NNAR.21

Autocorrelation function (ACF) indicated that current values were not correlated with previous values at lag 1 (Tables 2 and 3). In fact, the correlation coefficient between one point and the next in the time series ranged from − 0.07 to 0.19 for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and from − 0.16 to 0.31 for patients in the ICU. The highest values (0.19 and 0.31) were obtained for the TBATS model.22

According to Lewis’ [52] interpretation, since MAPE was always significantly lower than 10, all predictive models can be considered as highly accurate. Moreover, MASE was much lower than 1 for all models; therefore, all the proposed forecasting approaches performed significantly better than the forecasts from the (no-change) “naïve” methods, i.e., the forecasts with no adjustments for casual factors (Hyndman and Koehler 2006), which justifies the use of more complex and sophisticated models.

Tables 5 and 6 compare the hybrid models with the respective single models considering the minimization of MAE, MAPE, MASE, and RMSE metrics. For patients hospitalized with mild symptoms, the hybrid models outperformed the respective single models in 98 out of 112 metrics, i.e., on 87.5% of all the forecast accuracy measures. For patients hospitalized in the ICU, the hybrid models outperformed the respective single models in 81 out of 112 metrics, i.e., on 72.3% of all measures. In the latter case, however, almost all losses of efficiency (25 out 31) were attributable to NNAR.23 Thus, the hybrid models generally increased forecast accuracy, but this increase was more evident for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms.

Table 5.

Comparison between hybrid models and respective single models considering the minimization of MAE, MAPE, MASE, and RMSE metrics (in percentage), for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms

| Hybrid | Single | MAE | MAPE | MASE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A–E | ARIMA | − 1.01 | 30.26 | − 1.11 | 1.12 |

| ETS | − 5.44 | − 21.19 | − 5.45 | − 5.71 | |

| A–N | ARIMA | − 9.33 | − 17.19 | − 9.35 | − 9.99 |

| NNAR | − 5.05 | 9.49 | − 4.98 | − 5.66 | |

| A–T | ARIMA | − 2.34 | 1.91 | − 2.38 | − 1.96 |

| TBATS | − 1.63 | − 5.81 | − 1.6 | − 1.69 | |

| E–N | ETS | − 11.77 | − 50.87 | − 11.67 | − 13.03 |

| NNAR | − 3.28 | 7.39 | − 3.16 | − 2.23 | |

| E–T | ETS | − 5.73 | − 18.83 | − 5.76 | − 6.86 |

| TBATS | − 0.6 | 22.48 | − 0.64 | 0.16 | |

| N–T | NNAR | − 5.63 | 6.11 | − 5.65 | − 5.88 |

| TBATS | − 9.23 | − 25.83 | − 9.27 | − 9.95 | |

| A–E–N | ARIMA | − 6.54 | − 18.01 | − 6.5 | − 5.44 |

| ETS | − 10.72 | − 50.4 | − 10.61 | − 11.84 | |

| NNAR | − 2.135 | 8.4 | − 1.99 | − 0.89 | |

| A–E–T | ARIMA | − 2.79 | 20.08 | − 2.85 | − 1.22 |

| ETS | − 7.14 | − 27.36 | − 7.12 | − 7.9 | |

| TBATS | − 2.09 | 10.98 | − 2.08 | − 0.95 | |

| A–N–T | ARIMA | − 8.26 | − 18.64 | − 8.24 | − 7.72 |

| NNAR | − 3.93 | 7.57 | − 3.82 | − 3.28 | |

| TBATS | − 7.6 | − 24.81 | − 7.51 | − 7.47 | |

| E–N–T | ETS | − 10.99 | − 51.82 | − 10.91 | − 12.24 |

| NNAR | − 2.43 | 5.29 | − 2.33 | − 1.34 | |

| TBATS | − 6.15 | − 26.4 | − 6.07 | − 5.61 | |

| A–E–N–T | ARIMA | − 6.4 | − 19.22 | − 6.5 | − 5.2 |

| ETS | − 10.59 | − 51.13 | − 10.61 | − 11.61 | |

| NNAR | − 1.98 | 6.81 | − 1.99 | − 0.64 | |

| TBATS | − 5.73 | − 25.34 | − 5.75 | − 4.94 |

Notes: A ARIMA, E ETS, N NNAR, T TBATS. Negative (positive) values show the percentage efficiency gain (loss) from using hybrid models

Table 6.

Comparison between hybrid models and respective single models considering the minimization of MAE, MAPE, MASE, and RMSE metrics (in percentage), for patients hospitalized in the ICU

| Hybrid | Single | MAE | MAPE | MASE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A–E | ARIMA | − 0.35 | − 2.01 | − 0.4 | 1.79 |

| ETS | − 6.31 | − 3.34 | − 6.45 | − 5.56 | |

| A–N | ARIMA | − 8.67 | − 14.03 | − 8.69 | − 11.44 |

| NNAR | − 1.2 | 8.41 | − 1.31 | − 2.81 | |

| A–T | ARIMA | 2.19 | − 1.52 | 2.22 | 3.7 |

| TBATS | − 9.62 | − 2.67 | − 9.64 | − 9.31 | |

| E–N | ETS | − 11.06 | − 14.65 | − 11.2 | − 14.32 |

| NNAR | 2.34 | 9.11 | 2.18 | 1.35 | |

| E–T | ETS | − 0.05 | − 1.29 | − 0.19 | 0.63 |

| TBATS | − 5.97 | − 1.11 | − 6.07 | − 5.16 | |

| N–T | NNAR | 3.04 | 6 | 3.06 | 2.1 |

| TBATS | − 15.75 | − 16.93 | − 15.71 | − 18.64 | |

| A–E–N | ARIMA | − 5.54 | − 13.6 | − 5.45 | − 6.24 |

| ETS | − 11.19 | − 14.78 | − 11.2 | − 13.01 | |

| NNAR | 2.19 | 8.95 | 2.18 | 2.89 | |

| A–E–T | ARIMA | − 0.76 | − 5.1 | − 0.81 | 1.08 |

| ETS | − 6.69 | − 6.39 | − 6.83 | − 6.21 | |

| TBATS | − 12.22 | − 6.22 | − 12.32 | − 11.61 | |

| A–N–T | ARIMA | − 4.6 | − 15.03 | − 4.65 | − 5.6 |

| NNAR | 3.21 | 7.15 | 3.06 | 3.6 | |

| TBATS | − 15.62 | − 16.02 | − 15.71 | − 17.45 | |

| E–N–T | ETS | − 7.47 | − 15.43 | − 7.59 | − 9 |

| NNAR | 6.46 | 8.12 | 6.33 | 7.64 | |

| TBATS | − 12.96 | − 15.27 | − 13.04 | − 14.23 | |

| A–E–N–T | ARIMA | − 3.14 | − 14.56 | − 3.03 | − 2.98 |

| ETS | − 8.93 | − 15.72 | − 8.92 | − 9.98 | |

| NNAR | 4.78 | 7.74 | 4.8 | 6.47 | |

| TBATS | − 14.33 | − 15.56 | − 14.29 | − 15.16 |

Notes: A ARIMA, E ETS, N NNAR, T TBATS. Negative (positive) values show the percentage efficiency gain (loss) from using hybrid models

The best hybrid model for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms—NNAR–TBATS—outperformed the single NNAR and TBATS models by 5.63–9.23% on MAE and 5.88–9.95% on RMSE. While, the best hybrid model for patients hospitalized in the ICU—ARIMA–NNAR—outperformed the single ARIMA and NNAR models by 1.2–8.67% on MAE, and 2.81–11.44% on RMSE. Figures 3 and 4 graphically represent the models for both time series ranked by the MAE and RMSE metrics.

Fig. 3.

Models ranked by the MAE and RMSE metrics for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms

Fig. 4.

Models ranked by the the MAE and RMSE metrics for patients hospitalized in the ICU

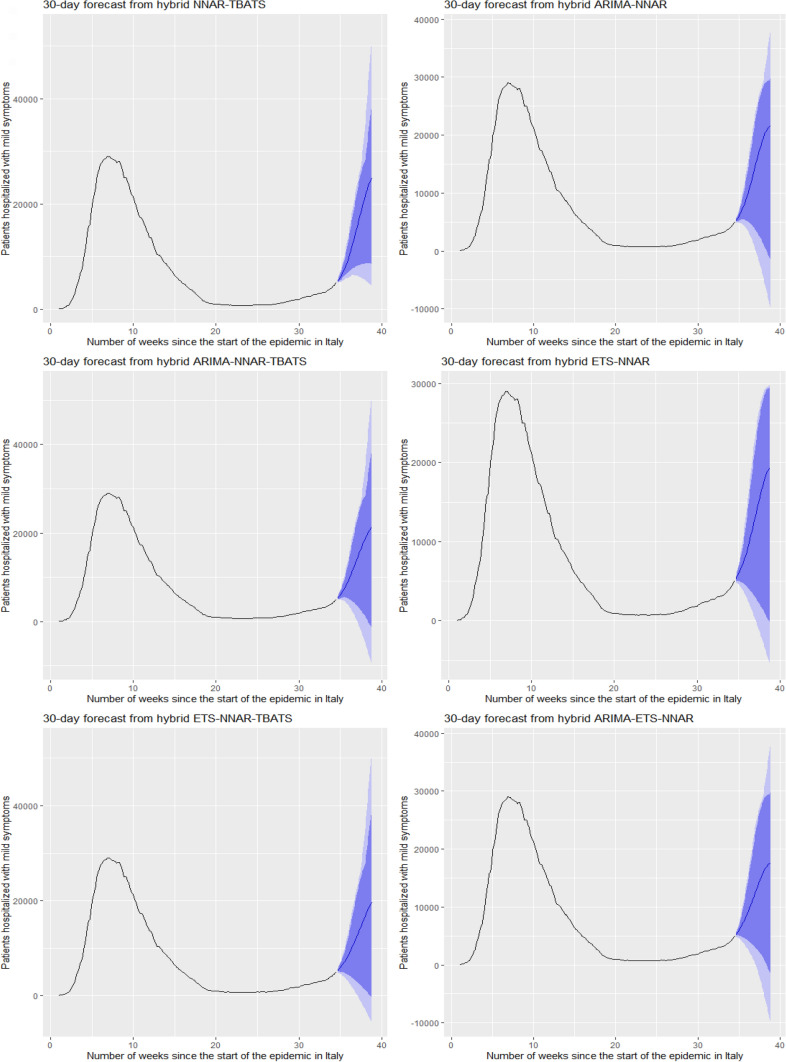

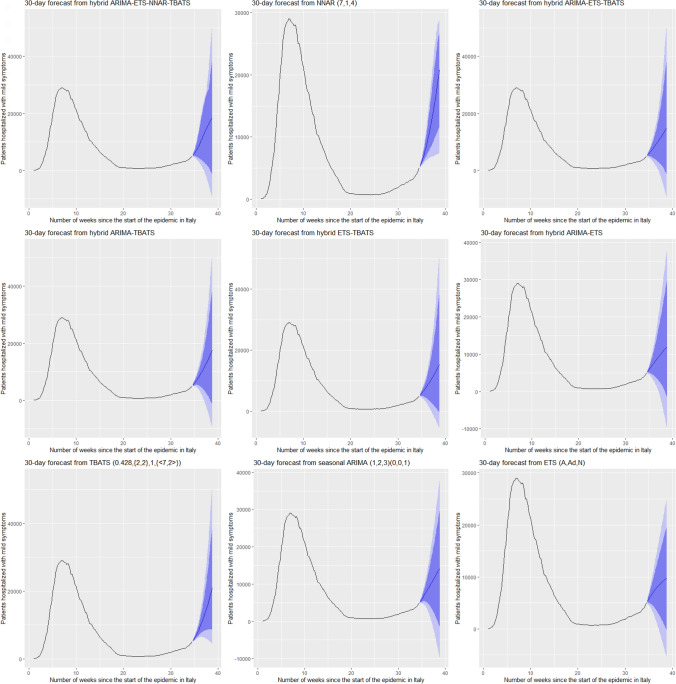

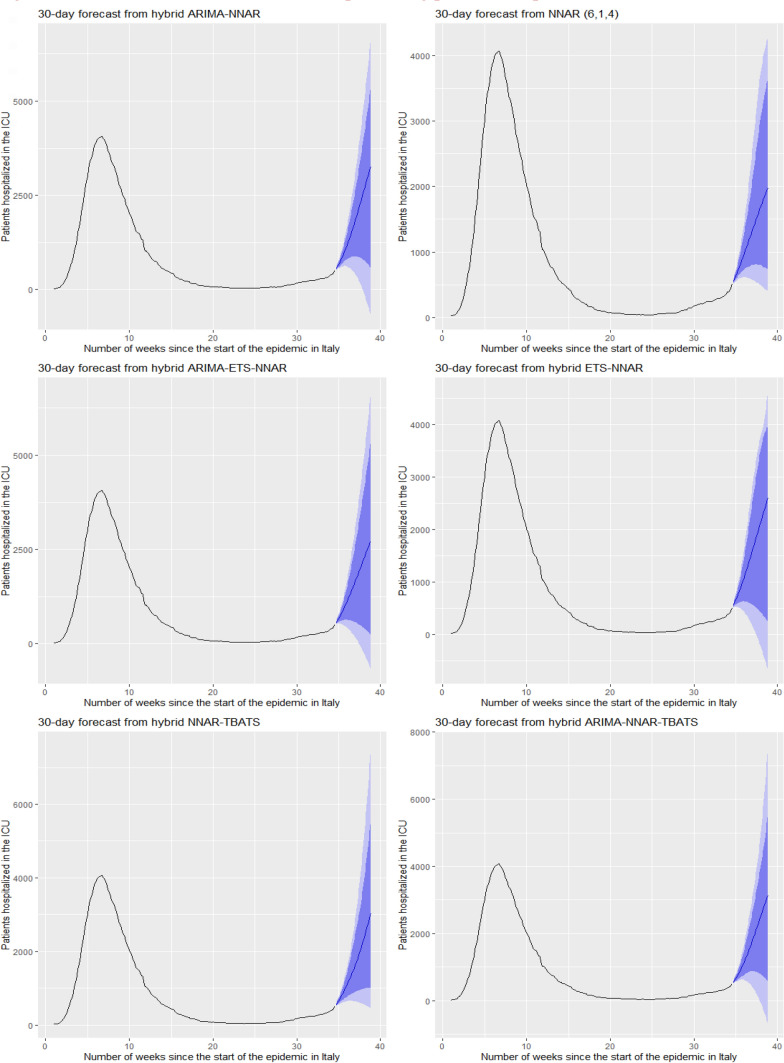

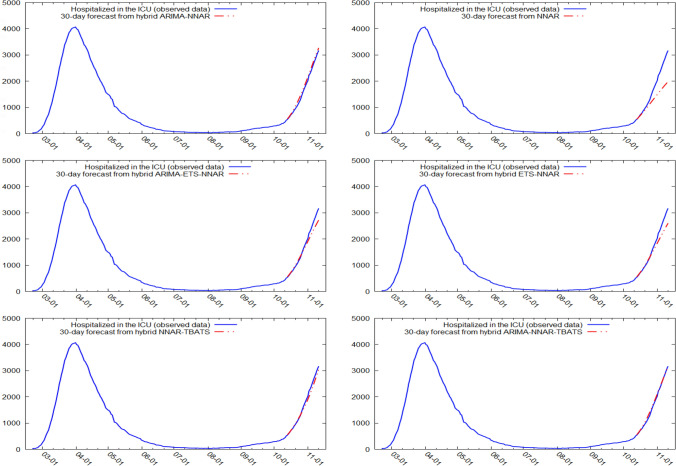

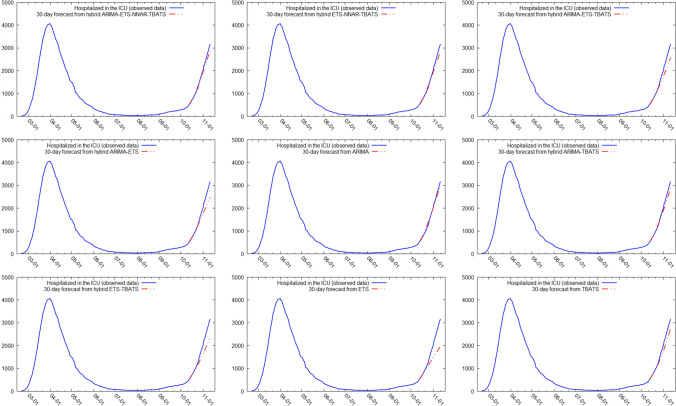

Figures 5 and 6 show the best six models and the remaining nine models for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms, respectively. Similarly, Figs. 7 and 8 show the best six models and the remaining nine models for patients hospitalized in the ICU, respectively. The light blue area in each graph shows the prediction intervals at 80%, while the dark blue area shows the prediction intervals at 95%.24 The forecasts of the best single and hybrid models anticipated an increase in the number of patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and in the number of patients admitted to the ICU over the next 30 days, i.e., from October 14, 2020, to November 12, 2020. This predicted trend was also confirmed by the remaining estimated models.

Fig. 5.

The six best forecast models for predicting patients with mild symptoms. Notes: the models were ranked (from first to sixth place) on the MAE metric

Fig. 6.

The remaining nine forecast models for predicting patients hospitalized with mild symptoms. Notes: The models were ranked (from seventh to fifteenth place) on the MAE metric

Fig. 7.

The six best forecast models for predicting patients hospitalized in the ICU. Notes: the models were ranked (from first to sixth place) on the MAE metric

Fig. 8.

The remaining nine forecast models for predicting patients hospitalized in the ICU. Notes: the models were ranked (from seventh to fifteenth place) on the MAE metric

Specifically, the NNAR–TBATS, ARIMA–NNAR, and ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS models predicted that: (i) after 10 days (October 23), the number of patients hospitalized with mild symptoms should have been 9624, 9397, and 9259, respectively; (ii) after 20 days (by November 2), the number should have been 18,000, 16,986, and 16,062, respectively; and (iii) after 30 days (by November 12), the number should have been 25,039, 21,669, and 21,430, respectively (Fig. 5). Regarding the number of patients hospitalized in the ICU, the ARIMA–NNAR, NNAR, and ARIMA–ETS–NNAR models predicted that: (i) after 10 days, the required number of intensive care beds should have been 1175, 972, and 1114, respectively; (ii) after 20 days, the required number should have been 2164, 1493, and 1915, respectively; and (iii) after 30 days, the number should have been 3270, 1985, and 2726, respectively (Fig. 7).25

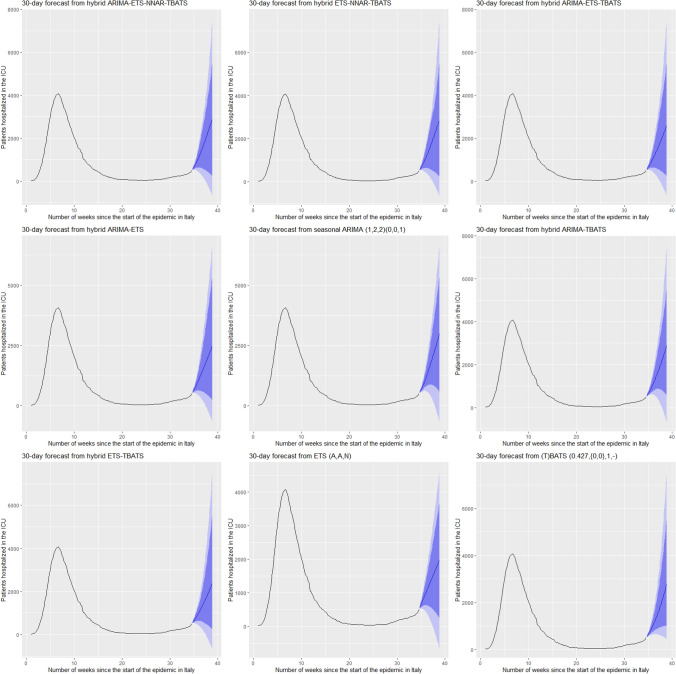

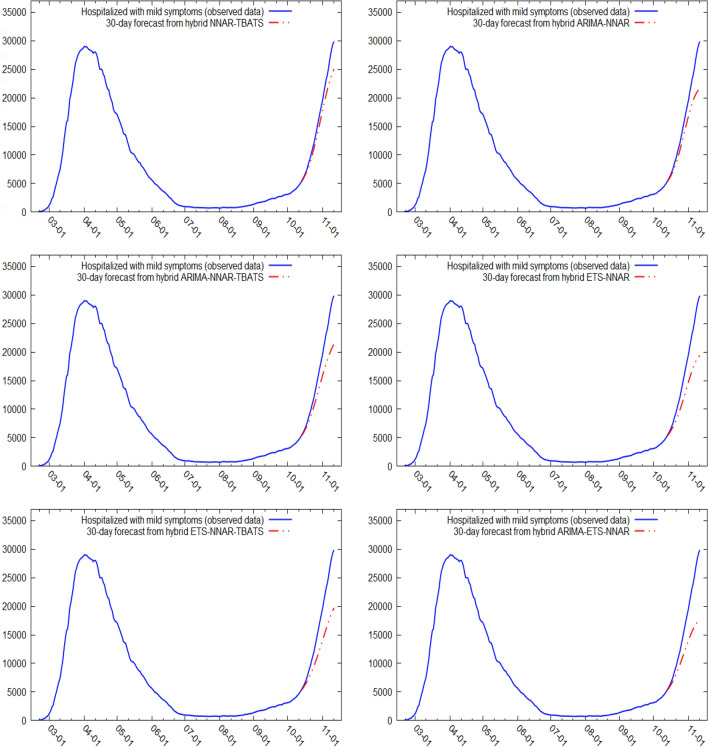

Figures 9, 10, 11 and 12 compare all 15 of the estimated models and the observed data over the period October 14, 2020, to November 12, 2020. For patients hospitalized with mild symptoms, the NNAR–TBATS models best fit the observed data (Fig. 9). Of the remaining models, predictions from ARIMA–NNAR, ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS, and NNAR most closely approximated the observed data (Figs. 9, 10). For patients hospitalized in the ICU, Fig. 11 reveals that ARIMA–NNAR, NNAR–TBATS, and ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS hybrid models also fit the observed data quite well. All estimated models generally exhibited a strong match between predictions and observed data, except for ETS, NNAR, and ETS–TBATS, where the trends differed (Figs. 11 and 12). Notably, the models with lowest loss of efficiency adapted better to the observed data, which confirms the consistency and robustness of the statistical approach.

Fig. 9.

Comparison between forecasts and real data during the period October 14, 2020, to November 12, 2020, for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms (six best models)

Fig. 10.

Comparison between forecasts and real data during the period October 14, 2020, to November 12, 2020, for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms (nine remaining models)

Fig. 11.

Comparison between forecasts and real data during the period October 14, 2020, to November 12, 2020, for patients hospitalized in the ICU (six best models)

Fig. 12.

Comparison between forecasts and real data during the period October 14, 2020, to November 12, 2020, for patients hospitalized in the ICU (nine remaining models)

Thus, a second wave of COVID-19 was predicted for the period following October 13, 2020, which could have several policy implications both for the national healthcare system and the economy. In particular, the predictions underscored the importance of implementing adequate containment measures and increasing the number of ordinary and intensive care beds, hiring additional healthcare personnel, and buying care facilities, protective equipment, and ventilators to fight the infection and reduce deaths.26 Meanwhile, the opportunity to implement more or less restrictive non-pharmaceutical interventions (NIPs) to tackle the pandemic—such as social distancing, travel bans, the use of face masks, hand hygiene, and bar and restaurant restrictions [20]—should be evaluated carefully in light of these measures’ potentially negative economic impacts. In fact, according to Fitch Rating’s [24] previsions, the first wave of COVID-19 and the consequent massive lockdown measures may already have caused up to a 9.5% contraction in Italy’s 2020 GDP.

While the models with the lowest loss of efficiency seemed to adapt substantially well to the observed data in the forecast window, the predictions should, in general, be treated with caution and employed mainly to inform short-term decisions. In fact, pandemic forecasting has raised many doubts in the last year due to several issues that can affect its accuracy and reliability, including, for example, (i) high interval predictions and sensitivity of the estimates, especially with long-term forecasts; (ii) inaccurate modeling assumptions, and (iii) the lack of or difficulty in measuring and identifying biological features of COVID-19 transmission [30, 42]. These limitations—and the possibility for misleading forecasts—may erode public trust in science and thus affect compliance with policies intended to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 [49]. Indeed, the inevitable uncertainty associated with this novel disease and the general failure of long-term and even mid-term forecasts require a different scientific approach toward model predictions. More prudent and balanced communication with the public is crucial if the field of science desires to maintain its leading role in human development and policymaking.

Conclusions

This paper attempted to forecast the short-term dynamics of real-time patients hospitalized from COVID-19 in Italy. In particular, it employed both single time series forecast methods and their feasible hybrid combinations. The results demonstrated that (i) the best single models were NNAR and ARIMA for both patients hospitalized with mild symptom and patients admitted to the ICU, (ii) the most accurate hybrid models were NNAR–TBATS, ARIMA–NNAR, and ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and ARIMA–NNAR, ARIMA–ETS–NNAR, and ETS–NNAR for patients hospitalized in the ICU, (iii) hybrid models generally outperformed the respective single models by offering more accurate predictions, and (iv) finally, predictions for the number of patients hospitalized in the ICU generally better fit the observed data than did predictions for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms. Notably, the best hybrid models always included a NNAR process, confirming the extensive and successful use of this algorithm in the COVID-19 related literature [56, 57, 71, 72, 81].

Compared to the single models, the hybrid statistical models captured a greater number of properties in the data structure, and the predictions seemed to offer useful policy implications. In fact, consistent with real-time data, the models predicted that the number of patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and admitted to the ICU would grow significantly until mid-November 2020. According to the estimations, the necessary ordinary and intensive care beds were expected to double in 10 days and to triple in approximately 20 days. Thus, since new waves of COVID-19 infections cannot be excluded, it may be necessary to strengthen the national healthcare system by buying protective equipment and hospital beds, managing healthcare facilities, and training healthcare staff.

Although the hybrid models proved to be sufficiently accurate, it is nevertheless important to stress that statistical methods may lead to unavoidable uncertainty and bias, which tend to grow over time, due, for example, to public authorities’ progressive implementation of NIPs, such as the closure of public spaces and national or local lockdown measures, which the forecasts cannot adequately incorporate. Combining hybrid models with mechanistic mathematical models may partially overcome these issues by considering the effects of lockdowns on epidemiological parameters [68]. Thus, future research could proceed along these lines. Ultimately, since other factors may have affected COVID-19 dynamics, especially as the pandemic progressed, these predictions should be treated with caution and utilized only to inform short-term decision-making processes.

Acknowledgements

I thank three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The parameter values of the ARIMA models for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and in the ICU

| Parameters | Coefficients (mild symptoms) |

Coefficients (ICU) |

|---|---|---|

| AR (1) |

0.5963*** [0.1675] |

0.8857*** [0.0542] |

| MA (1) |

− 1.0742*** [0.1737] |

− 1.4961*** [0.0829] |

| MA (2) |

− 0.0392 [0.1492] |

0.6093*** [0.07] |

| MA (3) |

0.3376*** [0.0685] |

|

| Seasonal MA (1) |

0.2226*** [0.0742] |

0.2707*** [0.0725] |

Notes: standard errors in brackets. ***p value < 0.01

Table A2.

The parameters values of the ETS models for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and in the ICU

| Parameters | Coefficients (mild symptoms) | Coefficients (ICU) |

|---|---|---|

| Smoothing parameters | ||

| α | 0.9999 | 0.9071 |

| Β | 0.4553 | 0.5871 |

| ϕ | 0.9709 | |

| Initial states | ||

| l | − 182.0547 | 20.9541 |

| b | 117.7546 | 3.4623 |

Table A3.

The parameters values of the TBATS models for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and in the ICU

| Parameters | Coefficients (mild symptoms) | Coefficients (ICU) |

|---|---|---|

| λ | 0.428 | 0.4267 |

| α | 0.2345 | 0.8384 |

| Β | 0.0794 | 0.371 |

| Damping parameter | 1 | 1 |

| − 0.000198 | ||

| − 0.000184 | ||

| AR (1) | 0.1077 | |

| AR (2) | 0.6249 | |

| MA (1) | 0.8727 | |

| MA (2) | 0.0074 |

Appendix B

Table B1.

Forecast accuracy measures of the single and hybrid models for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms

| Models | MAE | MAPE | RMSE | ACF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA–ETS | 115.344 | 3.4616 | 207.6742 | 0.0266 |

| ARIMA–NNAR | 109.0832 | 2.2002 | 191.1117 | − 0.0571 |

| ARIMA–TBATS | 113.3802 | 2.6759 | 200.8599 | 0.0963 |

| ETS–NNAR | 113.8125 | 2.159 | 204.3447 | 0.0091 |

| ETS–TBATS | 114.5352 | 3.396 | 203.9591 | 0.0938 |

| NNAR–TBATS | 110.5257 | 2.0911 | 193.8955 | 0.1055 |

| ARIMA–ETS–NNAR | 111.9864 | 2.1656 | 200.0585 | − 0.0109 |

| ARIMA–ETS–TBATS | 113.0631 | 3.1329 | 202.0993 | 0.0639 |

| ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS | 110.9721 | 2.1299 | 196.0419 | 0.0602 |

| ETS–NNAR–TBATS | 112.0909 | 2.0855 | 199.0529 | 0.0562 |

| ARIMA–ETS–NNAR–TBATS | 111.9338 | 2.1212 | 199.1672 | 0.0369 |

Notes: Models were combined using cross-validation errors. MASE is omitted because “cv.errors” function currently does not support it.

Table B2.

Forecast accuracy measures of the single and hybrid models for patients hospitalized in the ICU

| Models | MAE | MAPE | RMSE | ACF1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA–ETS | 12.63 | 3.4796 | 21.7734 | 0.0064 |

| ARIMA–NNAR | 11.7107 | 3.0801 | 19.3024 | − 0.0314 |

| ARIMA–TBATS | 13.0852 | 3.4932 | 22.3627 | 0.1946 |

| ETS–NNAR | 12.4014 | 3.112 | 20.7011 | − 0.0554 |

| ETS–TBATS | 13.3746 | 3.5436 | 22.9559 | 0.1498 |

| NNAR–TBATS | 12.8183 | 2.9997 | 21.5416 | 0.1691 |

| ARIMA–ETS–NNAR | 12.2468 | 3.0877 | 20.7276 | − 0.0316 |

| ARIMA–ETS–TBATS | 12.9046 | 3.4813 | 22.2089 | 0.1127 |

| ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS | 12.465 | 3.0191 | 21.0507 | 0.1209 |

| ETS–NNAR–TBATS | 12.7829 | 3.0591 | 21.7172 | 0.0892 |

| ARIMA–ETS–NNAR–TBATS | 12.62 | 3.0555 | 21.4791 | 0.0732 |

Notes: Models were combined using cross-validation errors. MASE is omitted because “cv.errors” function currently does not support it

Table B3.

Comparison between hybrid models derived using equal weights and weighted errors considering minimization of MAE, MAPE and RMSE (patients hospitalized with mild symptoms)

| Models | MAE (%) | MAPE (%) | RMSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA–ETS | − 0.22 | − 1.68 | − 0.27 |

| ARIMA–NNAR | − 3.37 | − 1.67 | − 3.53 |

| ARIMA–TBATS | 0.14 | − 0.5 | − 0.02 |

| ETS–NNAR | − 5.65 | − 1.72 | − 6.51 |

| ETS–TBATS | 0.16 | 1.95 | 0.31 |

| NNAR–TBATS | − 5.21 | 0.26 | − 5.14 |

| ARIMA–ETS–NNAR | − 2.97 | − 1.09 | − 3.19 |

| ARIMA–ETS–TBATS | − 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS | − 3.89 | − 0.21 | − 3.59 |

| ETS–NNAR–TBATS | − 3.36 | − 0.24 | − 3.14 |

| ARIMA–ETS–NNAR–TBATS | − 2.78 | − 0.5 | − 2.51 |

Notes: roman values indicated that equal weights were better, while italic values indicate that weighted errors were better.

Table B4.

Comparison between hybrid models derived using equal weights and weighted errors considering minimization of MAE, MAPE and RMSE (patients hospitalized in the ICU)

| Model | MAE (%) | MAPE (%) | RMSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA–ETS | − 0.72 | − 0.28 | − 1.04 |

| ARIMA–NNAR | − 1.87 | − 1.16 | − 2.87 |

| ARIMA–TBATS | − 1.74 | − 0.17 | − 1.83 |

| ETS–NNAR | − 4.01 | − 1.54 | − 5.56 |

| ETS–TBATS | − 0.01 | − | 0.01 |

| NNAR–TBATS | − 6.5 | − 0.77 | − 8.57 |

| ARIMA–ETS–NNAR | − 2.95 | − 0.91 | − 4.25 |

| ARIMA–ETS–TBATS | − 3.23 | − 3.47 | − 3.65 |

| ARIMA–NNAR–TBATS | − 3.69 | − 0.33 | − 5.07 |

| ETS–NNAR–TBATS | − 3.13 | − 0.75 | − 4.39 |

| ARIMA–ETS–NNAR–TBATS | − 3.42 | − 0.98 | − 4.38 |

Notes: roman values indicated that equal weights were better, while italic colored values indicated that weighted errors were better.

Appendix C

Table C1.

The Ljung–Box’s test results for autocorrelation in the models (patients hospitalized with mild symptoms)

| Models MILD Symptoms | Lags 2 | Lags 5 | Lags 8 | Lags 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA | 0.8093 | 0.437 | 0.6336 | 0.6986 |

| ETS | 0.1105 | 0.0157 | 0.001 | 0.0022 |

| NNAR | 0.0993 | 0.1274 | 0.0003 | 0.001 |

| TBATS | 0.6925 | 0.9045 | 0.5567 | 0.7197 |

| A–E | 0.1102 | 0.1444 | 0.2007 | 0.281 |

| A–N | 0.2038 | 0.2678 | 0.1012 | 0.1296 |

| A–T | 0.2129 | 0.3416 | 0.5749 | 0.6488 |

| E–N | 0.0519 | 0.0991 | 0.0139 | 0.044 |

| E–T | 0.0091 | 0.0398 | 0.0737 | 0.07 |

| N–T | 0.2428 | 0.2627 | 0.1088 | 0.1514 |

| A–N–T | 0.4573 | 0.4601 | 0.3396 | 0.4048 |

| A–E–N | 0.074 | 0.254 | 0.1631 | 0.229 |

| A–E–T | 0.0938 | 0.1763 | 0.2701 | 0.3763 |

| E–N–T | 0.0518 | 0.0986 | 0.0535 | 0.0925 |

| A–E–N–T | 0.1105 | 0.2543 | 0.2225 | 0.3068 |

Notes: A ARIMA, E ETS, N NNAR, T TBATS

Table C2.

The Ljung–Box’s test results for autocorrelation in the models (patients hospitalized in the ICU)

| Models ICU | Lags 2 | Lags 5 | Lags 8 | Lags 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIMA | 0.2477 | 0.3673 | 0.5745 | 0.7385 |

| ETS | 0.1565 | 0.063 | 0.0502 | 0.000 |

| NNAR | 0.0713 | 0.1089 | 0.0004 | 0.0014 |

| TBATS | 0.3775 | 0.5861 | 0.002 | 0.0052 |

| A–E | 0.1415 | 0.2366 | 0.0652 | 0.1353 |

| A–N | 0.0632 | 0.1105 | 0.11 | 0.2279 |

| A–T | 0.0985 | 0.0618 | 0.000 | 0.0000 |

| E–N | 0.0648 | 0.1036 | 0.1591 | 0.001 |

| E–T | 0.0199 | 0.0006 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| N–T | 0.2137 | 0.7283 | 0.8108 | 0.0041 |

| A–N–T | 0.1884 | 0.6286 | 0.0682 | 0.1397 |

| A–E–N | 0.0959 | 0.2094 | 0.0787 | 0.174 |

| A–E–T | 0.1257 | 0.0755 | 0.0002 | 0.0004 |

| E–N–T | 0.1832 | 0.5328 | 0.6055 | 0.0505 |

| A–E–N–T | 0.1807 | 0.5352 | 0.0549 | 0.0673 |

Notes: A ARIMA, E ETS, N NNAR, T TBATS

Appendix D

Table D1.

The predicted values of patients hospitalized with mild symptoms in Italy, from October 14, 2020 to November 12, 2020 (six best models)

| Date | Patients hospitalized with mild symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N–T | A–N | A–N–T | E–N | E–N–T | A–E–N | |

| 14-10-2020 | 5336.86 | 5347.71 | 5337.33 | 5338.38 | 5324.25 | 5336.2 |

| 15-10-2020 | 5651.95 | 5654.09 | 5644.54 | 5619.01 | 5602.82 | 5619.39 |

| 16-10-2020 | 6010.62 | 5990.28 | 5987.29 | 5916.08 | 5906 | 5921.66 |

| 17-10-2020 | 6393.93 | 6361.31 | 6358.13 | 6229.25 | 6218.18 | 6246.44 |

| 18-10-2020 | 6812.83 | 6766.48 | 6750.66 | 6573.92 | 6.548.27 | 6593.6 |

| 19-10-2020 | 7276.66 | 7209.03 | 7183.44 | 6934.69 | 6900.21 | 6965.03 |

| 20-10-2020 | 7779.26 | 7687.39 | 7643.35 | 7324.16 | 7268.47 | 7359.22 |

| 21-10-2020 | 8321.9 | 8209.49 | 8131.61 | 7746.5 | 7653.02 | 7781.47 |

| 22-10-2020 | 8932.9 | 8779.31 | 8668.44 | 8202.94 | 8071.92 | 8233.28 |

| 23-10-2020 | 9624.15 | 9397.23 | 9259.27 | 8698.68 | 8531.95 | 8713.3 |

| 24-10-2020 | 10,357.4 | 10,061.49 | 9877.39 | 9235.54 | 9012.85 | 9218.5 |

| 25-10-2020 | 11,117.49 | 10,764.26 | 10,511.98 | 9805.32 | 9510.84 | 9740.9 |

| 26-10-2020 | 11,917.57 | 11,500.99 | 11,168.61 | 10,401.09 | 10,039.3 | 10,275.97 |

| 27-10-2020 | 12,733.97 | 12,264.65 | 11,834.96 | 11,013.84 | 10,585.59 | 10,819.94 |

| 28-10-2020 | 13,550.94 | 13,047.27 | 12,508.36 | 11,637.78 | 11,139.26 | 11,370.28 |

| 29-10-2020 | 14,406.58 | 13,842.35 | 13,212.81 | 12,272.34 | 11,723.14 | 11,925.53 |

| 30-10-2020 | 15,305.39 | 14,642.62 | 13,942.71 | 12,919.64 | 12,338.97 | 12,482.49 |

| 31-10-2020 | 16,202.31 | 15,439.95 | 14,660.76 | 13,581.66 | 12,955.84 | 13,037.2 |

| 1-11-2020 | 17,093.01 | 16,224.71 | 15,361.98 | 14,252.71 | 13,571 | 13,585.9 |

| 2-11-2020 | 17,999.69 | 16,985.92 | 16,061.7 | 14,919.48 | 14,200.33 | 14,124.03 |

| 3-11-2020 | 18,888.69 | 17,712.48 | 16,739.24 | 15,570.64 | 14,826.46 | 14,645.62 |

| 4-11-2020 | 19,736.72 | 18,393.74 | 17,376.33 | 16,198.52 | 15,435.74 | 15,143.07 |

| 5-11-2020 | 20,573.69 | 19,020.32 | 17,996.11 | 16,794.27 | 16,051.78 | 15,608.2 |

| 6-11-2020 | 21,397.74 | 19,585.29 | 18,602.42 | 17,346.33 | 16,674.35 | 16,033.46 |

| 7-11-2020 | 22,153.42 | 20,085.04 | 19,162.8 | 17,843.65 | 17,265.48 | 16,413.91 |

| 8-11-2020 | 22,837.29 | 20,519.42 | 19,677.54 | 18,279.44 | 17,820.17 | 16,749.2 |

| 9-11-2020 | 23,480.72 | 20,890.96 | 20,169.1 | 18,651.09 | 18,355.65 | 17,041.07 |

| 10-11-2020 | 24,059.64 | 21,203,59 | 20,622.78 | 18,958.25 | 18,852 | 17,291.64 |

| 11-11-2020 | 24,560.39 | 21,461.63 | 21,030.51 | 19,202.09 | 19,296.82 | 17,503.69 |

| 12-11-2020 | 25,038.65 | 21,669.2 | 21,429.73 | 19,385.22 | 19,724.79 | 17,680.5 |

Notes: A ARIMA, E ETS, N NNAR, T TBATS

Table D2.

The predicted values of patients hospitalized in the ICU in Italy, from October 14, 2020 to November 12, 2020 (six best models)

| Date | Patients hospitalized in ICU | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A–N | N | A–E–N | E–N | N–T | A–N–T | |

| 14-10-2020 | 561.38 | 552.34 | 560.63 | 560.17 | 556.32 | 558.3 |

| 15-10-2020 | 609.88 | 587.43 | 609.54 | 607.84 | 601.59 | 606.11 |

| 16-10-2020 | 666.55 | 632.77 | 663.35 | 659.77 | 651.81 | 660.22 |

| 17-10-2020 | 724.24 | 678.52 | 717.5 | 714.29 | 705.48 | 715.95 |

| 18-10-2020 | 788.99 | 724.27 | 776.18 | 770.55 | 761.81 | 777.22 |

| 19-10-2020 | 858.45 | 774.31 | 838.26 | 830.93 | 822.91 | 842.98 |

| 20-10-2020 | 935.13 | 822.37 | 905.24 | 892.93 | 885.85 | 915.27 |

| 21-10-2020 | 1011.28 | 870.49 | 971.93 | 956.76 | 950.42 | 988.64 |

| 22-10-2020 | 1091.55 | 921.35 | 1041.7 | 1023.48 | 1017.24 | 1066.22 |

| 23-10-2020 | 1174.99 | 972.36 | 1113.99 | 1092.27 | 1085.73 | 1147.44 |

| 24-10-2020 | 1261.29 | 1023.36 | 1188.17 | 1162.67 | 1157.32 | 1231.88 |

| 25-10-2020 | 1350.75 | 1075.3 | 1264.1 | 1234.94 | 1231.24 | 1319.65 |

| 26-10-2020 | 1442.95 | 1127.25 | 1341.38 | 1308.44 | 1306.6 | 1410.39 |

| 27-10-2020 | 1537.98 | 1179.26 | 1420 | 1382.99 | 1383.99 | 1503.89 |

| 28-10-2020 | 1636.04 | 1231.7 | 1500.11 | 1458.61 | 1463.84 | 1600.11 |

| 29-10-2020 | 1736.85 | 1284.11 | 1581.46 | 1534.79 | 1546.25 | 1698.67 |

| 30-10-2020 | 1840.25 | 1336.37 | 1663.8 | 1611.31 | 1631.76 | 1799.19 |

| 31-10-2020 | 1946.12 | 1388.63 | 1747.01 | 1688.29 | 1720.53 | 1901.4 |

| 1-11-2020 | 2054.19 | 1440.7 | 1830.84 | 1765.57 | 1812.69 | 2004.94 |

| 2-11-2020 | 2164.21 | 1492.51 | 1915.1 | 1843.02 | 1908.64 | 2109.52 |

| 3-11-2020 | 2275.92 | 1544.08 | 1999.58 | 1920.59 | 2008.61 | 2214.94 |

| 4-11-2020 | 2388.88 | 1595.3 | 2083.98 | 1998.12 | 2112.68 | 2320.88 |

| 5-11-2020 | 2502.67 | 1646.09 | 2168.03 | 2075.54 | 2220.81 | 2427.05 |

| 6-11-2020 | 2616.77 | 1696.44 | 2251.46 | 2152.8 | 2332.7 | 2533.12 |

| 7-11-2020 | 2730.57 | 1746.27 | 2334.01 | 2229.78 | 2447.86 | 2638.73 |

| 8-11-2020 | 2843.41 | 1795.51 | 2415.46 | 2306.34 | 2565.64 | 2743.53 |

| 9-11-2020 | 2954.55 | 1844.11 | 2495.56 | 2382.29 | 2685.18 | 2847.15 |

| 10-11-2020 | 3063.22 | 1891.99 | 2574.1 | 2457.4 | 2805.52 | 2949.16 |

| 11-11-2020 | 3168.58 | 1939.08 | 2650.86 | 2531.37 | 2925.64 | 3049.14 |

| 12-11-2020 | 3269.82 | 1985.3 | 2725.65 | 2603.83 | 3044.52 | 3146.65 |

Notes: A ARIMA, E ETS, N NNAR, T TBATS

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli studi di Bergamo within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. None.

Availability of data and material

I extracted the data from the official Italian Ministry of Health’s website (www.salute.gov.it).

Code availability

The statistic software and codes are mentioned in the manuscript (“Materials and methods”).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

In fact, the number of infected people presents a high degree of uncertainty, especially because the number of infected but asymptomatic people is high [59].

It is valid only for the trend component.

See also, for example, Fallah et al. [21].

Both the augmented Dickey–Fuller test [19] and the Kwiatkowsky, Phillips, Schmidt, and Shin test [50] were used. In fact, as stated by Gujarati and Porter [28], there is no recognized uniformly powerful test for detecting unit roots.

The AICc is a bias-corrected version of the original Akaike information criterion (AIC) proposed by Sugiura [70] and Hurvich and Tsai [32]. The former performed significantly better than the latter in both small and moderate sample sizes [32]. Thus, it is suitable for this study.

A description of the “ets()” function is provided by Hyndman and Athanasopoulos [34], Sect. 7.6).

A description of the “nnetar()” function is provided by Hyndman and Athanasopoulos [34], Sect. 11.3).

This was the default value for the seasonal time series in the “nnetar()” function.

In fact, AICc is not included in the “tbats()” function.

A detailed description of the “forecastHybrid” package was provided at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/forecastHybrid/forecastHybrid.pdf.

To this regard, it is important to stress that Livera et al. [17] introduced a specific trigonometric representation of seasonal components based on Fourier series.

Hyndman [37] and Hyndman and Athanasopoulos [34], Sect. 3.4) offer a more detailed explanation of these metrics.

The parameter values of the ARIMA, ETS, and TBATS models were reported in Tables A1, A2, and A3 (Appendix A).

As suggested by Hyndman [38], since the time series covered less than year and had daily observations, the frequency was set to 7, which allowed for weekly seasonality.

The selected ETS model is also known as the damped trend method with additive errors.

The estimated TBATS model was derived by applying a Box–Cox transformation of 0.428, an ARMA{2,2} process for modeling errors, a damping parameter of 1 (doing nothing), and two Fourier pairs with seasonal periods of 7.

The selected ETS model is also known as Holt’s linear trend method. In this case, both error and trend were additive.

In this case, the “tbats()” algorithm gave a BATS model that differed from TBATS only in the way that it modeled seasonality. In particular, it did not implement the Fourier series to model seasonality. For simplicity, the notation TBATS was used for the discussion of hybrid models forecasting patients hospitalized in the ICU. This model employed a Box–Cox transformation of 0.427, no ARMA {0,0} errors, and a damping parameter of 1 (doing nothing).

The forecast performance measures of the hybrid models combined with the cross-validation procedure were reported in the Appendix B (Tables B1 and B2). With regard to patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and patients hospitalized in the ICU, the models derived using equal weights outperformed those obtained with cross-validated errors in 26 and 31 (out of 33) performance accuracy metrics, respectively Tables B3 and B4.

In particular, ARIMA–ETS–NNAR and ETS–NNAR models exhibited nearly identical accuracy.

Tables C1 and C2 (Appendix C) also reported the results of Ljung–Box’s [54] test for residual autocorrelation using no more than 10 lags, as suggested by Ljung [53] when the sample size is not large. The output showed that for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms, ARIMA, TBATS, and all hybrid models, except for ETS-TBATS, had no autocorrelation issue, while single ETS and NNAR exhibited some autocorrelation, especially at lags 8 and 10. With regard to patients hospitalized in the ICU, ARIMA and most of hybrid models, except for ARIMA–TBATS, ETS–TBATS, and ARIMA–ETS–TBATS, had no particular signs of autocorrelation. In contrast, single ETS, NNAR, and TBATS showed some problems at lags 8 and 10.

This did not change the meaning of the results because, as confirmed by Table C2 (Appendix C), the residuals of the hybrid model’s output were generally less affected by autocorrelation than were those for NNAR.

The choice of these percentages was consistent with Hyndman and Athanasopoulos (34, Sect. 3.5).

Values are rounded to the nearest integer. The predicted values of the six best models for patients hospitalized with mild symptoms and in the ICU were reported in Table D1 and D2 (Appendix D), respectively.

This is consistent with my recent paper [64] in which I demonstrated that the Italian healthcare system’s saturation played a key role in explaining the variability of COVID-19 mortality. In particular, the saturation of ordinary and intensive care beds explained almost 90% of the COVID-19 mortality across Italian regions at the first peak of the pandemic.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abotaleb MSA. Predicting COVID-19 cases using some statistical models: an application to the cases reported in China Italy and USA. Acad. J. Appl. Math. Sci. 2020;6(4):32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ala’raj M, Majdalawieh M, Nizamuddin N. Modeling and forecasting of COVID-19 using a hybrid dynamic model based on SEIRD with ARIMA corrections. Infect. Dis. Model. 2021;6:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzahrani SI, Aljamaan IA, Al-Fakih EA. Forecasting the sSpread of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia using ARIMA prediction model under current public health interventions. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020;13(7):914–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aslam M. Using the kalman filter with Arima for the COVID-19 pandemic dataset of Pakistan. Data Brief. 2020;31:105854. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awan TM, Aslam F. Prediction of daily COVID-19 cases in European countries using automatic ARIMA model. J. Public Health Res. 2020 doi: 10.4081/jphr.2020.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates JM, Granger CW. The combination of forecasts. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1969;20(4):451–468. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batista, M.: Estimation of the final size of the COVID-19 epidemic. MedRxiv (2020)

- 8.Benvenuto D, Giovanetti M, Vassallo L, Angeletti S, Ciccozzi M. Application of the ARIMA model on the COVID-2019 epidemic dataset. Data Brief. 2020;29:105340. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhardwaj R. A predictive model for the evolution of COVID-19. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s41403-020-00130-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Box GE, Cox DR. An analysis of transformations. J. Roy. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.) 1964;26(2):211–243. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Box G, Jenkins G. Time series analysis: forecasting and control. San Francisco: Holden-Day; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown RG. Statistical forecasting for inventory control. New York: McGraw/Hill; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao J, Jiang X, Zhao B. Mathematical modeling and epidemic prediction of COVID-19 and its significance to epidemic prevention and control measures. J. Biomed. Res. Innov. 2020;1(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ceylan Z. Estimation of COVID-19 prevalence in Italy, Spain, and France. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138817. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chakraborty T, Ghosh I. Real-time forecasts and risk assessment of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) cases: a data-driven analysis. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109850. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson J. Econometric theory. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Livera AM, Hyndman RJ, Snyder RD. Forecasting time series with complex seasonal patterns using exponential smoothing. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2011;106(496):1513–1527. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhamodharavadhani S, Rathipriya R, Chatterjee JM. Covid-19 mortality rate prediction for India using statistical neural network models. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:441. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickey DA, Fuller WA. Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica. 1981;49(4):1057–1072. [Google Scholar]

- 20.ECDC. Guidelines for the implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19 (2020). Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/covid-19-guidelines-non-pharmaceutical-interventions. Accessed 10 Oct 2020

- 21.Fallah SN, Deo RC, Shojafar M, Conti M, Shamshirband S. Computational intelligence approaches for energy load forecasting in smart energy management grids: state of the art, future challenges, and research directions. Energies. 2018;11(3):596. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fanelli D, Piazza F. Analysis and forecast of COVID-19 spreading in China, Italy and France. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;134:109761. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fantazzini D. Short-term forecasting of the COVID-19 pandemic using Google Trends data: evidence from 158 countries. Appl. Econometr. 2020;59:33–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitch Rating.: Fitch Affirms Italy at 'BBB-'; Outlook Stable (2020). https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-affirms-italy-at-bbb-outlook-stable-10-07-2020. Accessed 17 Oct 2020

- 25.Ganiny S, Nisar O. Mathematical modeling and a month ahead forecast of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an Indian scenario. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021;7(1):29–40. doi: 10.1007/s40808-020-01080-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giordano G, Blanchini F, Bruno R, Colaneri P, Di Filippo A, Di Matteo A, Colaneri M. Modelling the COVID-19 epidemic and implementation of population-wide interventions in Italy. Nat. Med. 2020;26:855–860. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0883-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodwin P, Lawton R. On the asymmetry of the symmetric MAPE. Int. J. Forecast. 1999;15(4):405–408. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gujarati DN, Porter DC. Basic econometrics. 5. New York: McGraw Hill Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasan N. A methodological approach for predicting COVID-19 epidemic using EEMD-ANN Hybrid Model. Intern. Things. 2020;11:100228. doi: 10.1016/j.iot.2020.100228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmdahl I, Buckee C. Wrong but useful—what covid-19 epidemiologic models can and cannot tell us. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(4):303–305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2016822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holt CE. Forecasting seasonals and trends by exponentially weighted averages (O.N.R. Memorandum No. 52) Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute of Technology; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurvich CM, Tsai CL. Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika. 1989;76(2):297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyndman.: New in forecast 4.0. https://robjhyndman.com/hyndsight/forecast4/ (2012)

- 34.Hyndman, R. J. and Athanasopoulos, G.: Forecasting: principles and practice, OTexts, Melbourne. OTexts.com/fpp2 (2018)

- 35.Hyndman RJ, Khandakar Y. Automatic time series forecasting: the forecast package for R. J. Stat. Softw. 2008;27(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyndman RJ, Koehler AB. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. Int. J. Forecast. 2006;22(4):679–688. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyndman RJ. Another look at forecast-accuracy metrics for intermittent demand. Foresight. 2006;4(4):43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyndman, R. J.: Forecasting with daily data, September 13, 2013. https://robjhyndman.com/hyndsight/dailydata/ (2013)

- 39.Hyndman RJ, Koehler AB, Ord JK, Snyder RD. Forecasting with exponential smoothing: the state space approach. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyndman RJ, Koehler AB, Snyder RD, Grose S. A state space framework for automatic forecasting using exponential smoothing methods. Int. J. Forecast. 2002;18(3):439–454. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ilie OD, Cojocariu RO, Ciobica A, Timofte SI, Mavroudis I, Doroftei B. Forecasting the spreading of COVID-19 across nine countries from Europe, Asia, and the American continents using the ARIMA models. Microorganisms. 2020;8(8):1158. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8081158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ioannidis JP, Cripps S, Tanner MA. Forecasting for COVID-19 has failed. Int. J. Forecast. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Italian Ministry of Health (Open Data). http://www.salute.gov.it/ (2020)

- 44.Joseph O, Senyefia BA, Cynthia NC, Eunice OA, Yeboah BE. Covid-19 projections: single forecast model against multi-model ensemble. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Appl. Math. 2020;5(2):20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katoch R, Sidhu A. An application of ARIMA model to forecast the dynamics of COVID-19 epidemic in India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1177/0972150920988653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katris C. A time series-based statistical approach for outbreak spread forecasting: application of COVID-19 in Greece. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;166:114077. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim S, Kim H. A new metric of absolute percentage error for intermittent demand forecasts. Int. J. Forecast. 2016;32(3):669–679. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kırbaş İ, Sözen A, Tuncer AD, Kazancıoğlu FŞ. Comparative analysis and forecasting of COVID-19 cases in various European countries with ARIMA, NARNN and LSTM approaches. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;138:110015. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kreps SE, Kriner DL. Model uncertainty, political contestation, and public trust in science: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Adv. 2020;6(43):eabd4563. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwiatkowski D, Phillips PCB, Schmidt P, Shin Y. Testing the Null Hypothesis of Stationarity against the Alternative of a Unit Root. J. Econometrics. 1992;54(1–3):159–178. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee DH, Kim YS, Koh YY, Song KY, Chang IH. Forecasting COVID-19 confirmed cases using empirical data analysis in Korea. Healthcare. 2021;9(3):254. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis CD. Industrial and Business Forecasting Methods: A Practical Guide to Exponential Smoothing and Curve Fitting. Boston, London: Butterworth Scientific; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ljung GM. Diagnostic testing of univariate time series models. Biometrika. 1986;73(3):725–730. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ljung GM, Box GE. On a measure of lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika. 1978;65(2):297–303. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melin P, Monica JC, Sanchez D, Castillo O. Multiple ensemble neural network models with fuzzy response aggregation for predicting COVID-19 time series: the case of Mexico. Healthcare. 2020;8(2):181. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moftakhar L, Seif M. The Exponentially Increasing Rate of Patients Infected with COVID-19 in Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 2020;23(4):235–238. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Namasudra, S., Dhamodharavadhani, S., and Rathipriya, R.: Nonlinear Neural Network based forecasting model for predicting COVID-19 cases. Neural Process. Lett. 1–21 (2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Nesteruk I. Statistics-based predictions of coronavirus epidemic spreading in Mainland China. Innov. Biosyst. Bioeng. 2020;4(1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;173(5):362–367. doi: 10.7326/M20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Panigrahi S, Behera HS. A hybrid ETS–ANN model for time series forecasting. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2017;66:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Papastefanopoulos V, Linardatos P, Kotsiantis S. Covid-19: A comparison of time series methods to forecast percentage of active cases per population. Appl. Sci. 2020;10(11):3880. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perone, G.: An ARIMA model to forecast the spread and the final size of COVID-2019 epidemic in Italy (No. 20/07). HEDG, c/o Department of Economics, University of York (2020)

- 63.Perone, G.: ARIMA forecasting of COVID-19 incidence in Italy, Russia, and the USA. http://arxiv.org/abs/2006.01754 (2020)

- 64.Perone G. The determinants of COVID-19 case fatality rate (CFR) in the Italian regions and provinces: an analysis of environmental, demographic, and healthcare factors. Sci Total Environ. 2021;755:142523. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ribeiro MHDM, da Silva RG, Mariani VC, dos Santos Coelho L. Short-term forecasting COVID-19 cumulative confirmed cases: perspectives for Brazil. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109853. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rios M, Garcia JM, Sanchez JA, Perez D. A statistical analysis of the seasonality in pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2000;16(5):483–488. doi: 10.1023/a:1007653329972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sahai AK, Rath N, Sood V, Singh MP. ARIMA modelling and forecasting of COVID-19 in top five affected countries. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(5):1419–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sardar T, Nadim SS, Rana S, Chattopadhyay J. Assessment of lockdown effect in some states and overall India: A predictive mathematical study on COVID-19 outbreak. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139:110078. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh S, Parmar KS, Kumar J, Makkhan SJS. Development of new hybrid model of discrete wavelet decomposition and autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models in application to one month forecast the casualties cases of COVID-19. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109866. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sugiura N. Further analysts of the data by Akaike's information criterion and the finite corrections: further analysts of the data by Akaike's. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods. 1978;7(1):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Talkhi N, Fatemi NA, Ataei Z, Nooghabi MJ. Modeling and forecasting number of confirmed and death caused COVID-19 in IRAN: a comparison of time series forecasting methods. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2021;66:102494. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Toğa G, Atalay B, Toksari MD. COVID-19 Prevalence Forecasting using Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): case of Turkey. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14(7):811–816. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tuite AR, Ng V, Rees E, Fisman D. Estimation of COVID-19 outbreak size in Italy. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):537. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30227-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Y, Xu C, Yao S, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang L, Zhao X. Estimating the prevalence and mortality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the USA, the UK, Russia, and India. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019;13:3335–3350. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S265292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]