Abstract

Hostile resistance (clients’ openly combative behavior directed at therapists) predicts poor outcomes in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for panic disorder, but its origins are poorly understood. It is important to have a holistic understanding of the etiology of hostile resistance that incorporates the therapeutic context if these behaviors—and their negative consequences—are to be prevented and effectively addressed. Of 71 adults who received CBT for panic disorder as part of larger trial, 8 exhibited hostile resistance. Grounded theory methodology was used to develop a theoretical framework to understand why these patients became hostile in session. The 10 minutes of session preceding instances of hostile resistance and matched portions of sessions from five never hostile controls were coded. Two pathways to hostile resistance emerged—one in which patient characteristics were primary, and one wherein therapist failures (particularly of empathy) were primary. Being a challenging patient (i.e., narcissistic, obsessive, angry, resistant) moderated which pathway was followed. However, even among challenging patients, rarely was hostile resistance attributable to patients’ dispositions alone. Most often, patient factors interacted with therapist (e.g., displays of frustration) and treatment (e.g., directiveness, degree of structure) factors to produce such resistance. Contrary to the view of hostile resistance as simply a product of a hostile patient, the picture is more complex. Findings indicate that greater attention to common factors in CBT and more flexible applications of treatment protocols is warranted.

Keywords: panic disorder, hostile resistance, resistance, process in cognitive-behavioral therapy, grounded theory

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) represented a breakthrough in efficacious treatment of panic disorder; still, approximately 40% of patients do not respond (Loerinc et al., 2015). Who are these patients? While few predictors have been identified (Porter & Chambless, 2015), a recent study found that panic clients observed to express hostile resistance in CBT sessions went on to have significantly worse outcomes than their non-hostile counterparts (redacted). Resistance in a CBT framework refers to verbal or nonverbal client behaviors that go against the direction set by the therapist (e.g., homework noncompliance, arguing, not answering; Miller & Rollnick, 2012). Hostile resistance is defined as resistance delivered in an openly combative manner that communicates a personal attack on the therapist (e.g., disparaging the therapist’s competence, methods, or personal qualities; Westra, Aviram, Kertes, Ahmed, & Connors, 2009). In [redacted’s] sample, hostile resistance was coded in 10% of sessions and included such statements as angrily asking: “Do you realize who you’re speaking with?”

Although other studies have shown that resistance in general impedes treatment progress (e.g., Westra & Norouzian, 2018), [redacted] found that the detrimental effects of resistance may be specific to its hostile form: While overall resistance was unrelated to outcome in this study, hostile resistance early in treatment predicted drop out, and at mid-treatment predicted poor subsequent panic symptom improvement—even after established predictors of outcome in this sample (e.g., expectancy; redacted) were controlled. Though [redacted] is the only study to examine the relation between hostile resistance and symptomatic outcome, these findings align with the wider literature identifying anger and hostility as difficult emotions that can derail treatment and maintain psychopathology, as well as with outcome research in related areas. For instance, unresolved ruptures in the working alliance—which might be a consequence of hostile resistance (redacted)—predict worse outcomes (Eubanks, Muran, & Safran, 2018). Moreover, hostility directed at the therapist has been linked to poor therapist competence in interpersonal therapy (IPT) for depression (Foley, O’Malley, Rounsaville, Prusoff, & Weissman, 1987) and worse introject change in dynamic therapy for general outpatients (Henry, Schacht, & Strupp, 1990). Other research has investigated hostile behavior more generally (i.e., hostility not necessarily directed at the therapist), and similarly found that client hostility impedes treatment. For instance, higher patient-reported aggression has been linked to worse therapist competence/adherence and anxiety reduction in CBT for panic (Boswell et al., 2013; Cassiello-Robbins et al., 2015). This research also suggests that therapists treating panic disorder may be at an especially heightened risk of encountering hostility, as panic patients exhibit elevated levels of anger and aggression compared to depressed (Gould et al., 1996), healthy (Fava et al., 1993), and other anxiety (Moscovitch, McCabe, Antony, Rocca, & Swinson, 2008) populations.

Therefore, client hostility is an important negative prognostic marker that may be especially detrimental to the treatment of panic disorder. To the extent that hostile resistance is an indication that something is awry in the treatment process or plays a causal role in derailing therapy, it is imperative to understand the etiology of hostile resistance if these behaviors, the factors that contribute to them, and their negative sequelae are to be prevented or effectively addressed. However, very little is known about the factors that contribute to hostile resistance in CBT. No studies have examined predictors of hostile resistance in CBT for panic disorder specifically, and the few studies that have examined hostile resistance in other populations have been limited by a narrow focus on dispositional qualities of the patient alone, without accounting for the broader therapeutic context. While certain patient characteristics have been linked to hostile resistance (e.g., personality pathology, low expectancy for improvement, low beliefs in treatment’s credibility; Ahmed, Westra, & Constantino, 2012; redacted), in a therapeutic context such factors do not exist in a vacuum. Rather, therapists might have strong emotional reactions to these qualities (i.e., countertransference; Jacobs, 1999), or responsively adapt treatment according to clients’ behavior and individual needs (Aviram, Westra, Constantino, & Antony, 2016; Westra, Aviram, Connors, Kertes, & Ahmed, 2012). In other words, given the inherently interpersonal, reciprocal, and dynamic nature of both resistance (Miller & Rollnick, 2012) and psychotherapy, the assumption that hostile resistance is simply a product of a hostile patient may be overly reductionist; instead, we might reasonably expect that patient qualities are related to hostile resistance by way of complex interactions with therapist or treatment factors.

As support, the CBT framework conceptualizes resistance not as a trait that resides in the patient, but rather as the product of a complex and fluid interpersonal process in which patient, therapist (e.g., empathy, responsivity), and treatment (e.g., directiveness, patient-treatment fit) factors all play a role. In fact, persistent resistance is typically viewed as a therapist, rather than patient, failing (Miller & Rollnick, 2012), and different treatments have been shown to elicit distinct types of resistance (Watson & McMullen, 2005). Further disputing the notion that hostile resistance strictly reflects a patient trait, hostile resistance was only modestly correlated within patients over time in [redacted’s] sample (κ = .34), suggesting that contextual factors may contribute or interact in determining whether patients become hostile in session.

While it may therefore be most useful to conceptualize hostile resistance as a complex relational phenomenon, the contributions of therapist and treatment characteristics to client hostility nevertheless remain poorly understood. It is possible that therapist and relational factors related to resistance more broadly may play a role in hostile resistance, as well, such as early feelings of anger toward clients (Westra et al., 2012), fewer empathic statements (Hara, Westra, Constantino, & Antony, 2018), and lower working alliance (e.g., Watson & McMullen, 2005). We also might expect competence and adherence considerations to play a role, given that these factors have been linked to observer- and self-rated patient hostility in IPT for depression (Foley et al., 1987) and CBT for panic (Boswell et al., 2013). As for treatment factors, none have been identified as predictors of hostile resistance. Only one such factor—treatment directiveness—has been examined in relation to resistance broadly, with several studies finding that more directive interventions lead to higher resistance, while more supportive strategies reduce resistance (Beutler, Moleiro, & Talebi, 2002). Beyond directiveness, it is unknown how other features of a given intervention may contribute to resistance in general and hostile resistance in particular, as well as how treatment or therapist factors might interact with patient characteristics to affect the likelihood of hostility’s occurrence.

Given our limited understanding of how hostile resistance arises, this paper will employ grounded theory (GT; Glaser & Strauss, 2017) qualitative methods to identify patient, therapist, treatment, and relational factors that contribute to hostile resistance in the context of CBT for panic: Which clients become hostile, why, and what role might therapists and the treatment play? GT is concerned with constructing, rather than testing, hypotheses and theory by remaining “grounded” in the data. For new and developing areas of research, such as hostile resistance’s etiology, this methodology confers the advantage of being unconstrained by preconceptions as to which variables will prove important. It also allows us to incorporate the complexities of the therapeutic context and the interactional nature of patient, therapist, and treatment factors, thereby promoting the development of a rich and nuanced understanding of hostile resistance’s origins. By developing a holistic theoretical framework that incorporates the broader therapeutic context to explain the emergence of hostile resistance, our aim is to guide efforts to prevent and address such resistance and its contributing factors, and ultimately improve outcomes.

Method

Session recordings were collected as part of a two-site RCT comparing the efficacy of three different therapies for panic disorder (redacted). The CBT arm, which followed a modified version of Panic Control Therapy (PCT; Craske, Barlow, & Meadows, 2000), is the focus of the present study and produced an overall response rate of 63% (defined a priori as > 40% reduction Panic Disorder Severity Scale score; Shear et al., 1997). Patients randomized to CBT participated in up to 24 biweekly 45-minute sessions over 12 weeks. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, as was approval of the Institutional Review Boards of both sites.

Therapists

Of eight clinicians who administered CBT in this trial (6 women, 8 White), five (3 women, 2 men) had at least one client who expressed hostile resistance. All therapists had doctoral degrees and at least one year of experience treating panic disorder with CBT. Therapists who encountered hostile resistance did not differ from those who did not on post-graduate clinical experience (overall M = 9.95, SD = 6.1; redacted).

Participants

Patients in this trial were adults with primary panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. Those who were acutely suicidal, substance dependent, in concurrent therapy, or had a history of psychosis or mania were excluded. Seventy-one patients were coded for resistance as part of a sister study (redacted): 56% were female, 66% White, 25% Black, 7% Asian, and 20% Hispanic, and the mean age was 39 (SD = 12.7). Thirty-six (51%) were treated at [site 1] and 35 at [site 2].

Ever hostile patients.

Of the 71 CBT patients coded for resistance, 8 were found to exhibit hostile resistance at least once, representing 14 instances of hostility over 10 distinct sessions (5 Session 2s, 5 Session 10s).1 As part of [redacted] (which contains greater detail on procedures related to resistance coding), in-session hostile resistance was reliably coded using the Client Resistance Code (Westra et al., 2009). Coders watched Sessions 2 (psychoeducation) and 10 (cognitive restructuring) in their entirety and rated 30-second bins for peak resistance severity, from 0 (none) to 3 (hostile resistance). Patients were identified as ever hostile if either session contained at least one code of 3. The ever hostile group had a mean age of 45 (SD = 12.6) and consists of 6 White and 2 Black patients (1 identifying as Hispanic); 6 were male and 2 female.

Never hostile controls.

Of the remaining (never hostile) patients, five—one for each therapist who encountered hostile resistance—were selected to form a never hostile control group. Patients in this group had not expressed hostile resistance in either Session 2 or 10. The never hostile group includes 4 White, 1 Black, 3 male, and 2 female patients, as well as 3 Session 10s and 2 Session 2s—such that groups were approximately matched on gender, race, therapist, and session composition.

Procedure

Transcripts and videos of the 10 minutes of session preceding instances of hostile resistance, as well as matched portions of sessions for never hostile controls, were analyzed using a GT framework in NVivo 12 software. Open coding of all materials in randomized order was completed by the first two authors, who first applied codes independently and then met after coding each session to resolve disagreements through consensus. During the open coding phase, all therapist and client behaviors in the 10-minute interval were coded, with codes capturing concepts (of any length of text) with similar meanings and themes (see Appendix). These codes were refined and grouped into higher-order categories as more sessions were coded. Over time, certain concepts emerged as particularly relevant to the presence of hostile behavior. Only these codes are discussed in the present manuscript, but the full codebook is presented in the Appendix to illustrate our process. After all sessions had been coded, both coders reviewed and reached consensus on all materials a second time to ensure that coding decisions had remained consistent throughout. Throughout coding, the first author recorded emerging ideas about theory in a session-specific memo—the collection of which formed the basis for much of the theory presented in this paper. Theory was also derived using constant comparison, particularly comparisons of ever hostile versus never hostile patients, and of sessions within a given therapist. Once a comprehensive theory was developed using these methods, the first author presented it to the second author for modification and verification.

Coders

Coder 1 is a clinical psychology Ph.D. candidate and Coder 2 a Professor of Psychology at [site 1]. Both study psychotherapy process and outcome predictors and have received advanced training in CBT for anxiety; Coder 2 also has training in psychodynamic and process-experiential psychotherapy. Having served as the CBT supervisor at [site 1] in the parent trial, Coder 2 had extensive familiarity with patients (six ever hostile, four never hostile) who received treatment at [site 1]. The qualitative tradition recognizes that researcher bias cannot be eliminated, and should thus be monitored and used judiciously to inform data analysis and interpretation (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). As such, the impact of Coder 2’s prior exposure was continuously reflected upon, and her observations from viewing an extensive sample of CBT sessions were cautiously harnessed as a source of knowledge at times.

Results

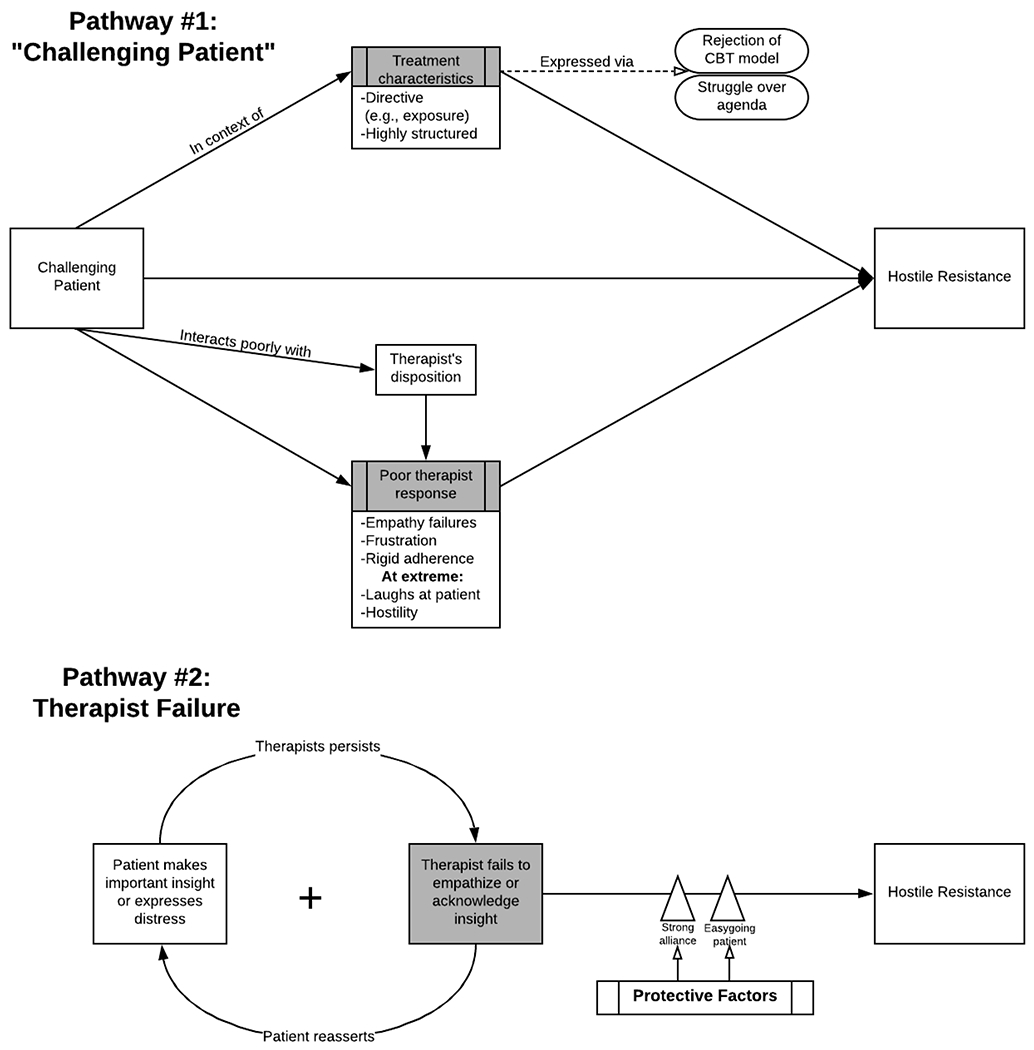

As depicted in Figure 1, two overall pathways to hostile resistance emerged, moderated by whether the patient was judged to be challenging (i.e., narcissistic, obsessive, angry, or generally resistant). In the first, and more common, pathway, patient qualities were primary; in the second, therapist failures—particularly in empathy—were primary. Each pathway and its subsidiary arms are described below, with illustrative examples from session transcripts. To maintain confidentiality, anonymized identifiers are used: P1-P8 refers to ever hostile patients, T1-T5 to therapists, and C1-C5 to never hostile controls (whose numerical identifiers match those of their therapists). Some quotations have been modified slightly to enhance readability or remove identifying information. Codes and concepts relevant to Figure 1 are marked in bold.

Figure 1.

A grounded-theory model of the pathways to hostile resistance.

Pathway 1: Challenging Patient is Primary

The first pathway starts with the presence of a challenging patient, by which we mean patients who pose difficulties for therapists in the management of the session. Challenging patients possess at least one of the following dispositions: (a) Narcissism, as evidenced by frequent expressions of one’s own specialness and entitlement; (b) Obsessiveness, as evidenced by over-concern with perfect accuracy of reports and detailed monologues; (c) Anger, or frequently expressing disparaging, offensive, or dismissive comments, humor, or body language; (d) Consistent resistance, or persistently exhibiting clear yet non-hostile forms of non-cooperation and treatment-interfering behaviors (i.e., homework noncompliance, tardiness/poor attendance, clear opposition/arguing, not answering questions, setting own agenda). Qualities were judged to be dispositional, rather than a product of therapist or treatment factors, when they were observed frequently (over one or multiple sessions) and/or they were temporally positioned in such a way that they appeared unprompted (e.g., if a patient walked into session angry). Of the eight ever hostile patients, six (across eight sessions) were judged to be challenging (3 angry, 2 obsessive, 3 narcissistic, 4 resistant).2 In contrast, there were no challenging patients in the never hostile group. Rather, control patients were overwhelmingly cooperative, engaged, and attentive, exhibiting minimal resistance of any kind. Some appeared dispositionally easygoing, in that they responded cooperatively and non-defensively even in the face of therapists’ mistakes and difficult tasks (e.g., exposures). As shown in Figure 1 (Pathway #1), challenging patients became hostile through a number of distinct sub-paths, discussed in turn.

Direct pathway to hostile resistance

In at least one case (P1/T1), a patient’s challenging disposition appeared sufficient to produce hostility, irrespective of the therapist’s behavior or qualities of the intervention being employed. P1 exhibited dispositional anger and narcissism: He entered the room in Session 2 already relaying anger (towards a woman making a complex order at the coffee shop: “‘Lady, just get a cup of coffee. There’s nine people in line.’”), and then went on to make several disparaging comments about women to his female therapist (e.g., referring to his girlfriend as “the bitch”). Throughout the segment, the patient persistently attempted to assert his dominance, using dismissive humor and body language (e.g., smirks, power poses), cutting the therapist off to redirect the agenda, and telling his therapist that he “wouldn’t care” if he were “in trouble” in therapy or “give a shit” about what she thinks. That this patient displayed four instances of hostility within 7 minutes, and that the first of these occurred within the first minute of session, strongly suggests a direct pathway to hostile resistance, whereby the patient became hostile simply because he was already predisposed to angry, hostile behavior. Our impression is bolstered by his offensive behavior to members of the research staff, especially to women.

Interaction with therapist behaviors

More commonly, being a challenging patient led to hostile resistance by way of eliciting poor responses from therapists. Often these responses took the form of empathy failures (i.e., missed opportunities to express empathy or acknowledge an important insight/achievement, empathic expressions that were non-accurate or emotionally disconnected), displays of therapists’ own annoyance (e.g., forcefully cutting off patients), and rigid adherence to the protocol at the expense of empathy. At the extreme, challenging patients’ behavior was even found to evoke hostility/severe criticism and laughter at the patient’s expense from therapists. These responses exacerbated a situation that might have otherwise been defused with more empathy, supportiveness, or flexibility—leading to clients’ hostility.

Grounded example.

One therapist (T2) had such a strong emotional reaction to a challenging patient (P2) that—unable to mask her frustration—she actually laughed at the patient’s expense in Session 2, was herself hostile in Session 10, and committed a series of empathy failures. P2 was dispositionally obsessive and resistant, which often translated into excessively detailed monologues, agenda-setting struggles, and clear opposition to the therapist’s direction. The therapist’s frustration with these behaviors appeared to impede her ability to offer empathy in Session 2, when P2 repeatedly expressed his “malaise” and “very deep despair.” The therapist either did not attempt empathy at all (“We could just keep an eye on it”) or, when she did, only managed empathic statements that were emotionally disconnected or non-accurate, which the patient swiftly disputed. These empathy shortcomings formed the foundation for the rupture that followed, when the therapist laughed at the patient’s response to a question—embarrassing him and prompting him to respond forcefully, defensively, and hostilely. P2’s hostility in Session 10 followed a similar pattern. The therapist, clearly irritated with the patient’s persistent opposition to exposure ideas, showed her frustration with hostility of her own:

T2: What would it be like to start a car right now?

P2: I don’t wanna, I don’t wanna start a car…. Yeah, I won’t do it.

T2: So, just starting a car, that would be uncomfortable? What about just getting behind the driver’s seat without even putting the key in the ignition?

P2: Let’s go somewhere else. I don’t wanna start with the car ‘cause I’m not gonna do it.

T2: You’re not gonna do what?

P2: Go drive.

T2: Well, you don’t have to drive. You could just do something that’s minor for now.

P2: I’m not gonna get there.

T2: You’re not gonna, you wouldn’t even get behind the wheel?

P2: Nope.

T2: Not even behind the wheel and not start the ignition?

P2: No….

T2: It sounds like there are a number of potential options. Another option would be to speak in public, no?

P2: (shaking head “no”) I don’t want to do that.

T2:(hostilely) Well, of course, you don’t wanna do anything…

Shortly thereafter, P2 responded with his own hostility. In both of P2’s sessions, then, the therapist engaged in damaging behaviors—apparently stemming from very understandable frustration—that escalated rather than defused an already tense dynamic, leading to hostility.

Grounded examples involving therapists’ dispositions.

Occasionally, poor responses were the product of an interaction between therapists’ own dispositional qualities and those of challenging patients. In one case (P3/T3), a challenging patient’s chronic resistance exacerbated the therapist’s hectoring/critical transactional style, characterized by a directive, and at times patronizing, finger-wagging tone. This style was evident in all three sessions rated for the therapist, but did not always lead to a hostile escalation. In fact, with her easygoing control (C3), this style came across as jovial: With a cooperative patient, the therapist’s tendency to offer the occasional, figurative slap on the wrist, and address her client as a teacher might her student (e.g., “young man”) amounted to a mild, even playful, rebuke. When T3 seemed frustrated with a patient’s persistent noncompliance, however, this critical style became genuinely harsh and scolding. At one point in P3’s Session 10, the therapist responded to the patient’s not having completed her homework—apparently a regular occurrence—with overtly hostile criticism:

T3: Did you do your panic diaries? Did you fill them out?

P3: No. No (laughs). No, I didn’t.

T3: And…

P3: Don’t be mad at me, please.

T3:(in a cold voice tone) Listen, I’m neither mad nor happy, I’m like neutral.

P3: I mean, I have them in my head… I’ll go back and, you know, fill [the diaries] in.

T3: I know, but let me tell you what the problem is with doing it retrospectively. Retrospectively, sometimes the situation can look far worse than it actually was. And so you don’t have an accurate perspective of what’s actually happening. The second thing you have to know is you’re here in this treatment for you, not for me, not for anybody else. And you ’re the loser if you don’t do the homework. Because then you don’t gain the skills in the given period of time. So that’s what you have to remember.

The therapist’s exasperation with P3’s chronic resistance also appears to interfere with her ability to offer praise and empathy in the limited opportunities available. For instance, after uncovering more homework noncompliance, the therapist misses an opportunity to empathize with the patient’s distress about her health, mental state, and worsening panic—instead doubling down on a critical style that, in the context of frustration, no longer seemed jovial:

P3: I have that [log] in here somewhere. Umm, this week’s been bad. I don’t know where I put [my homework]. It’s with my panic diaries… I’m focusing on this health issue again.

T3: Well here’s my question, why do you focus on that when what you really need to be focusing on is mastering the panic?

P3: Yeah, I don’t know why I’m focusing on that, that’s why I’m here, I guess. I’m nutty.

T3: No, seriously, why do you think you focus on the, on the…

P3: On the health? I don’t know. I have no idea. ‘Cause I remember even doing it before my mom died so it’s not… like I think maybe it’s worse after that. Ten times worse.

Finally, apparently unable to contain her frustration, the therapist laughs at the patient’s expense, making light of a symptom the patient experienced as distressing: “So, you experienced two particular symptoms and then the third one you kind of confabulated (laughs) in terms of talking weird.” Seemingly in response to T3’s empathy failures, hostility, and unwelcome laughter, the patient becomes increasingly defensive, apprehensive, and quick to act out—ultimately hostilely. Just as with T2/P2, had the therapist been better able to conceal her frustration, or overcome it enough to praise or empathize with the patient in key moments before pressing for a change in behavior, in our view the overall tone of the session would have been greatly improved, and hostile resistance prevented.

A second poor temperamental fit was detected between one therapist (T4), who was dispositionally rather matter of fact rather than overtly warm in interactions with clients, and a challenging patient with dispositional anger (P4). P4 was visibly upset throughout her Session 2 segment, crying and even panicking as she delivered long, off-protocol monologues. In an appropriate effort to stay on protocol, the therapist made several attempts to curtail these monologues and redirect the patient. However, his delivery of these redirections was not particularly warm or empathic. For instance, as the patient wept after relaying a particular insecurity about her daughter, the therapist responded: “Right. Right. I might have to corral you a bit.” As we see with T4’s never hostile control (C3), this matter of fact style was not inherently problematic—so long as clients were not often in a state where warmth might be desired. However, in the context of a patient like P4, who was in acute distress, prone to anger, and veered extensively away from the session protocol, it constituted rigid adherence at the expense of empathy that led to significant fallout. Clearly irritated and possibly feeling condescended to, P4 responded forcefully, defensively and, ultimately, hostilely to T4’s inattentiveness to her distress and efforts to rush her along and get her back on track. She dropped out of treatment.

Interaction with treatment characteristics

In other cases, hostile resistance resulted from a poor fit between challenging patients’ characteristics and those of the treatment. Two aspects of the treatment were particularly at odds with challenging patients’ dispositions. First, the treatment, and especially its emphasis on exposure, was very directive: Among narcissistic clients, being told what to do risked triggering anger or being viewed as a challenge to one’s intelligence. Second, whereas some CBT protocols are flexible or principle-driven, this treatment was highly structured: Each session had a standardized agenda, and the mandate of adherence in the context of a study afforded minimal flexibility. As a result, obsessive patients could become frustrated with the inability to talk at length and off-protocol, and narcissistic patients could grow angry with a standardized protocol that did not fully recognize their specialness. These clashes were often expressed via struggles over the agenda and rejections of the CBT model—sometimes at a level that constituted hostile resistance. In contrast, such rejections and agenda struggles were notably absent among controls, who instead tended to express agreement with the model and cooperate willingly with directions—even exposures. Thus, neither the treatment as a whole, nor its most directive element (exposure), always or necessarily elicited resistance—let alone hostile resistance. Rather, the interaction was important: The directive and structured nature of the treatment produced hostility only in the context of challenging patients.

Grounded examples.

All three of P5’s hostile resistance expressions represent clashes between his dispositional narcissism and obsessiveness, and the treatment’s directiveness or standardized structure. In both Sessions 2 and 10, hostility was directly preceded by the mention of exposure—the most directive piece of treatment; in both, moreover, hostile resistance ensued from P5’s belief that the standard CBT model did not apply to him given his specialness, and corresponding rejections of key components of the treatment. In Session 2, this rejection was focused on the notion that his avoidance behaviors—of which there were many—could possibly be related to his panic; in Session 10, he rejected the relevance of feared physical sensations and, by extension, interoceptive exposures—an integral part of treatment. Convinced that physical sensations had “nothing to do with [his] panic,” P5 immediately resisted the rationale for interoceptives (asking repeatedly, “Why are we doing this again?”) and nearly refused to attempt the exposures planned for that session. Instead, in this session’s first instance of hostility, he accused interoceptives of being purely for the purpose of torture: “This may be like the Milgram experiment… none of the[se exercises] have anything to do with anything…. they just sound very unpleasant without any possible benefit.” With the therapist’s encouragement, the patient reluctantly agreed to try “a couple” of exposures. However, as the session progressed, his rejection of, and frustration with, the CBT protocol intensified. At one point, P5 even posited an alternative, psychodynamic interpretation of his symptoms—the ultimate rejection of the CBT model, especially in one’s tenth session: “It has nothing to do with the physical sensation. It is psychological and related to something that happens when I’m sleeping… There’s a trigger, and it’s not a physical sensation. What this session has caused me to see is that this has some sort of psychoanalytical sort of thing. Something is hooked onto the sinus, the night problems I had breathing as a kid. I think I’m linking it somehow to my father.”3

P5’s preference for an idiographic framework, such as psychodynamic theory, is consistent with his desire to be viewed as unique. In taking this stance, however, P5 initiates a struggle not only over the agenda, but also over the very theoretical framework within which he and his therapist are operating. The therapist’s subsequent attempts to redirect to the standardized protocol only appear to further fuel P5’s frustration with a treatment that lumps him in with a larger group. Ultimately, his irritation with the treatment’s inability to capture his specialness culminates in a second expression of hostile resistance, wherein the client laughs dismissively at the therapist’s suggestion of completing an interoceptive for homework—“I could (laughs)”—as though the idea were silly or beneath him. It is worth noting that the therapist (T5) acted competently throughout, given that he had an agenda to work through. He validated the client’s concerns before redirecting to the protocol, and whereas other therapists (e.g., T2) let their own emotional reactions show in response to patients’ difficulty, this therapist notably did not. This lends support to the theory that, here, hostile resistance was not a function of the therapist’s behavior, but rather of a poor fit between patient and treatment characteristics.

With the same therapist, a similar clash was observed between a second dispositionally narcissistic patient (P6) and the highly structured nature of the treatment. P6 appeared to reject the very idea of participating in a study—the epitome of standardization. He entered Session 10 saying he was “angry and offended” at study personnel for asking assessment questions that felt “not really relevant,” and for giving him insufficient time to elaborate on his answers in a way that could adequately capture his specialness (for which he indicated he would need “all day”). Feeling disrespected due to a desire to have his uniqueness recognized, he went on to accuse the study personnel, and indirectly his therapist, of caring more about getting their “paperwork in order” and their grant funding than understanding him “as an individual.” The therapist masterfully handled this client’s frequent angry outbursts and his tendency to come into sessions with a head of steam about some perceived slight that he had to discuss immediately. As a result, the dyad maintained good rapport, but the therapy was often derailed from its focus on panic.

Pathway 2: Therapist Failure is Primary

Not all patients who exhibited hostile resistance were challenging. Rather, in two cases, the primary cause of hostility was a persistent therapist failure. A common pattern emerged in these cases (Figure 1, Pathway #2): In situations that warranted empathy or acknowledgement, therapists instead responded with persistent applications of the protocol (rigid adherence) at the expense of adequate empathy or acknowledgement (empathy failures). These errors prompted otherwise non-challenging patients to express hostile resistance.

Grounded examples

In the first case, the therapist’s error was in failing to acknowledge an important insight. P7 bore a striking resemblance to controls: Far from being challenging, he had strong buy-in to the CBT model, good rapport with his therapist, and was doing well in therapy. In Session 10, P7 reported a highly meaningful insight about his intrinsic self-worth, sharing his realization that he is not “inferior, stupid, [or] not worthy,” but rather “confident, capable” and “deserving.” He went on to link his feelings of inferiority to his relationship with his brother: “Here’s the real thinking error: People that I fear are not my older brother. That’s a unique relationship. It’s not the relationship I have with everyone in a position of authority. My challenge to the scary thought is: ‘Free yourself from this and hold yourself high. You deserve it.’ It’s a liberating feeling realizing that everyone in positions of authority are not my brother.”

Instead of supporting the significance of this insight and encouraging the patient to develop it further, the therapist (T3) goes backwards with a misguided attempt to apply cognitive therapy, asking the patient to justify his worth as a human being: “Could you add actual data that supports that alternative thought?”; “What about evidence that points to you being deserving?” The patient responds with continuous reassertions of his original insight, rejecting the therapist’s direction as a step backward. Despite strong signaling from the patient, the therapist persists:

T3: I deserve it because…

P7: Um, because of everything, I don’t wanna use a scale to say I am competent because of X, Y, Z accomplishments. I mean it’s just…

T3: What if you said ‘I deserve it ‘cause I work hard, I set meaningful goals for myself?’

After several such exchanges, the therapist does recognize her mistake. She suggests discussing P7’s insight in greater depth (“Well, tell me more about it, let’s take a little time and really talk about it”). It is at this point that P7 replies with hostile resistance—“This isn’t your area though”—as though in retaliation for the failure to acknowledge his insight for so long.

In the second case (P8/T2) also, the therapist expresses insufficient acknowledgement. In Session 2, P8 reports an important achievement when he describes how, despite his anxiety about doing so, he disposed of his tranquillizers, recognizing the medication as an unnecessary crutch. Although this action—especially so early in the therapeutic process—deserves significant praise and reinforcement, the therapist instead responds with only mild congratulations before prematurely changing the topic. Soon thereafter, the therapist commits a second, and perhaps more consequential, error by responding to the patient’s growing distress with inadequate empathy. Throughout this segment, P8 repeatedly expressed distress about the meaning of his panic symptoms. In addition to worrying that his “loud” and “irregular” heartbeats were indicative of a serious cardiac issue, he was self-conscious that his complaints would not be taken seriously and that he would be viewed as crazy. Rather than respond to the patient’s visible distress empathically, however, the therapist directively applied psychoeducation:

P8: I don’t know if I’m gonna come off—I’m not crazy—I could actually, when I go to sleep, I could hear my heartbeat. And I don’t think that’s normal.

T2: Well, sure it’s normal. If you’re listening for your heart, we can all find our pulse.

P8: No, but I could just lay down in my bed, I could hear my heart pounding, like, I could count, how many times, every time it pounds. So I don’t think that’s normal.

T2: Well, what’s going on is that people with panic, they become very good at monitoring their bodily sensations, their heartbeat, so you’re able to notice your heart beating, but most people can do that if they actually bring their attention to…

P8: But, I mean, you could listen to it, like, like-?…

Even as the patient’s distress intensified, the therapist’s default response was matter of fact, non-empathic exposition of the “correct” interpretation. However, by disputing the patient’s belief that his symptoms were due to a physical issue without first validating his experience and distress, the therapist may have inadvertently triggered the client’s fear of being viewed as crazy:

T2: We’re going to talk more about [the cause of your symptoms], but it’s not exactly…

P8: That’s where, that’s where the thought comes from.

T2: Right, but it’s not like…

P8: (raises voice) ‘Cause I know I’m not making [my symptoms] up…. I know I’m not making it up ‘cause I know what I-, I’m listening to it.

Although the therapist’s application of psychoeducation was appropriate in isolation, the real misstep was in her failure to first provide empathy to a patient who was distressed and increasingly sensitive to insinuations that his symptoms were in his head. Had the therapist taken a moment to empathize with P8’s discomfort, and acknowledge that his response was understandable rather than crazy given how scary panic symptoms can be, she might have been able to put him at ease rather than provoking a defensive, and ultimately hostile, escalation.

Protective factors

Therapists’ errors were observed in control sessions as well, but did not result in hostile resistance. Though no guarantee that hostility would not ensue, two factors made this outcome less likely, protecting against the negative effects of therapists’ mistakes:

Working alliance.

Stronger working alliances—as indicated by shared laughter/positive affect, expressions of positive regard, quickly reestablishing agreement after a conflict, and agreement on goals—cushioned against the negative effects of therapists’ errors.4 For example, T2—who encountered hostility with P8 after applying psychoeducation at the expense of adequate empathy—made a similar error with her control patient, C2. C2 had just finished describing her tendency to be an overprotective parent when the therapist commented on the risks of this parenting style (“You know, overprotective parents are one of the things that are related to anxious children… so how you behave communicates to your kids at any given moment that Armageddon might come, right?”). As with P8, this application of psychoeducation was risky: It might have come off as judgmental or critical. However, the dyad’s markedly strong alliance buffered against subsequent hostility: Rather than seeming offended, C2 even laughed in agreement: “(laughs) Yeah, which I think is what my parents did to me you know. So, that’s why in my head I do think the worst case scenario all the time.”

Easygoing patient.

Dispositionally easygoing (i.e., non-defensive, cooperative) patients were less likely to respond to therapists’ mistakes with hostile resistance. C3’s easygoing temperament was protective when his therapist, T3, made two errors analogous to those she made with P7: First, the therapist continuously asserted her interpretation over the patient’s about the meaning of a particular automatic thought. Although C3 pushed back, he did so in a calm, non-defensive manner, and eventually the therapist deferred to his interpretation without eliciting hostile resistance. Soon thereafter, T3 failed to adequately acknowledge an important insight, when the patient realizes that his automatic thoughts about panic are “absurd.” Once again, the patient’s easygoing disposition appeared to shield him from insult and subsequent hostility. Errors that might have resulted in a defensive or hostile escalation with less easygoing patients proved, instead, to have little impact on the relationship or session flow.

Discussion

Given the relation between hostile resistance and poor outcome in CBT for panic, this study employed grounded theory methods to elucidate the origins of such resistance. We developed a theoretical framework positing that hostile resistance is the product of complex interactions between patient, therapist, and treatment factors. Consistent with quantitative reports of personality pathology being elevated in resistant and hostilely resistant samples (redacted; Zickgraf et al., 2015), personality factors emerged as key: Hostile resistance was primarily exhibited by dispositionally challenging patients, with high trait levels of anger, narcissism, obsessiveness, and overall resistance often playing a central role. Nevertheless, this study highlights that a purely patient-centric account of hostile resistance is insufficient. Contrary to the view that hostile behavior is simply the product of a challenging patient, in only one case was hostile resistance attributable to patient qualities alone: Rather, most often, patient factors interacted with therapist and treatment factors to produce this behavior. Even when clients were observably challenging, therapists’ behaviors appeared instrumental in provoking hostile resistance. Moreover, a second pathway to hostile resistance was uncovered in which therapist failures—particularly of empathy—were the primary cause of client hostility. In this pathway, otherwise non-challenging clients appeared driven to hostile expressions by persistent therapist errors, with patient contributions appearing negligible.

Findings underscore the importance of understanding hostile resistance as a complex relational phenomenon. Although previous studies have identified certain patient variables as related to hostile resistance (e.g., low expectancy; Ahmed et al., 2012), the contributions of therapist, treatment, and relational factors have hitherto been overlooked in the empirical literature, perhaps due to the difficulty of capturing or contextually situating these constructs quantitatively. Nevertheless, qualitative analyses revealed that challenging patients’ behavior often elicited poor responses from therapists, ranging from empathy failures, clear displays of annoyance, and rigid adherence, to laughing at patients’ expense and even hostility on the part of therapists themselves. These behaviors, in turn, exacerbated situations that might have otherwise been defused. That therapists’ behaviors were observed to contribute to hostile resistance—whether or not a patient was dispositionally challenging—is consistent with evidence that, when asked why they were resistant in session, clients themselves cite reasons pertaining to therapists (e.g., ambivalence about the therapist’s competence or approach; Rennie, 1994).

Our emphasis on the mutual influence of clients’ and therapists’ behavior is consistent with research indicating that difficult client behaviors negatively impact therapists’ performance. Resistance impedes therapists’ competence and adherence (Boswell et al., 2013; Zickgraf et al., 2015), and confrontational client behaviors cause therapists to provide less encouragement and praise (Francis et al., 2005). Of particular relevance given the principal role of empathy failures in our framework, resistant behaviors have also been shown to result in fewer (Hara et al., 2018) and more “hollow” (Francis et al., 2005) empathic statements from therapists. Therapists so commonly respond to resistance in a confrontational or argumentative manner that this response type has been given a name—counter-resistance (Moyers & Rollnick, 2002). In addition, just as our theory posits that therapists’ poor responses can reciprocally escalate an already tense dynamic, evidence suggests that therapists’ reactions to patients have a large bearing on subsequent client behavior. For instance, therapists’ early negative feelings towards patients (e.g., anger, helplessness, frustration) lead to higher levels of resistance (Westra et al., 2012).

While therapists’ behaviors can have a large impact on those of clients, we observed that clinician errors do not always lead to hostile resistance. Rather, the examination of non-hostile controls highlighted two protective factors that buffered against the negative effects of clinician errors: Patients’ easygoing disposition and a strong working alliance. The protective function of the therapeutic relationship is consistent with evidence that a stronger working alliance predicts positive therapy outcomes more generally (Norcross & Lambert, 2019). Moreover, these results further highlight the relational and context-dependent nature of hostile resistance, which only seems likely to occur if certain factors are (or are not, in the case of a strong alliance) in place.

The importance of treatment characteristics—and the way in which they interact with patients’ dispositions—represents another addition to the literature on resistance in CBT. In particular, the directive and highly structured nature of this trial’s protocol appeared to provoke frustration, and ultimately hostility, among challenging patients. While the role of directiveness is consistent with research showing that more directive approaches produce higher resistance and worse outcomes (Aviram et al., 2016; Beutler et al., 2002), the contribution of a treatment’s degree of structure is novel in the literature.

This study had limitations, most notably its small sample. Though the number of hostilely resistant patients in our study may appear small, it is important to note that these eight patients do not make up the universe of patients who were hostilely resistant in treatment; rather, they represent only a subset of the larger population of patients who were hostilely resistant but in sessions other than the two sampled in this study. Another limitation is that this study does not pinpoint why hostile resistance is related to poor outcome. We have previously demonstrated that hostile resistance’s negative relationship to outcome is not due to its overlap with expectancy (redacted). It is possible that for some patients, hostile resistance may simply be a marker for another process that already interferes with treatment (e.g., of patients who are challenging and unlikely to improve in short-term, highly structured CBT protocols such as that used in the present study). For others, hostile resistance may be an indication that something is awry in the therapeutic process or play a causal role in derailing treatment. For instance, hostile resistance may exert its impact by impeding therapists’ ability to implement the intervention (Zickgraf et al., 2015) or by degrading the working alliance—hypotheses we plan to examine. Overall, given GT’s focus on generating, rather than testing, hypotheses, it is our hope that the present research provides the impetus and foundation for future empirical research.

Clinical Implications

Having a more complete understanding of how hostile resistance emerges has significant clinical implications. To the extent that preventing hostile resistance and correcting the factors that contribute to its emergence might improve outcomes, the present theory highlights several potential targets where intervention could alter the therapeutic trajectory. The first is in the way therapists respond to challenging clients’ behaviors. Recent work has demonstrated that the way in which a therapist responds to resistance has a significant bearing on patient outcomes (Aviram et al., 2016). Nevertheless, therapists’ own emotional reactions were often observed to produce unhelpful responses. While an emphasis on countertransference has long been part of dynamic tradition (e.g., Jacobs, 1999), CB therapists are less likely to receive training in how to manage their emotional reactions to challenging clients. Given that therapists’ own displays of frustration often precipitated client hostility, additional training in providing adequate empathy, supportiveness, and flexibility while experiencing powerful emotional reactions may help to alleviate tension, avert hostile displays, and improve outcomes (Markowitz & Milrod, 2011).

Moreover, given the importance of empathy failures in producing hostile resistance—whether or not a patient was challenging—and the protective function of the therapeutic alliance, findings point to the value of additional training focused on empathic expression and building rapport. These skills cut across therapeutic schools of thought and are critical to therapy’s success (common factors; e.g., Frank & Frank, 1991; Wampold, 2015); yet, in our experience, CB trainers often assume that therapists have skills in common factors and thus focus primarily on technical interventions. Findings indicate that therapists may benefit from more explicit training in competently delivering accurate and appropriate empathy, and responsively tailoring the therapeutic relationship to enhance therapy’s efficacy (e.g., Norcross & Lambert, 2019).

Improving the treatment-patient fit might also mitigate the risk of inciting hostile resistance and the tensions that precede it. If interpreted through the lens of a treatment matching approach, results indicate that patients with pronounced personality dysfunction may be more content with idiographic, and less directive and structured, forms of therapy (e.g., panic-focused psychodynamic therapy; Milrod et al., 2016). That said, it is important to clarify that our theory does not describe CBT per se, but only highly structured CBT. Step-by-step manuals such as that used in the present study (Craske et al., 2000) have significant benefits in ease of training, dissemination efforts, and clarity for the development of adherence and competence measures. However, there are also principle-driven CBT manuals that likely promote greater flexibility and idiographic approaches (e.g., Clark & Salkovskis, 2009). Such an approach might avoid provoking hostile reactions from at least some challenging clients. To be clear, it is also not the case that CBT possesses no potential benefit for patients with personality disorders. Indeed, treating personality dysfunction is an active area of interest and practice in CBT (e.g., Beck, Davis, & Freeman, 2015). Our findings only suggest that in a time-limited, highly structured treatment with panic as the focus, wherein therapists are expected to adhere to a detailed protocol, therapists may encounter difficulties managing such patients and carrying out panic-focused interventions. This problem might arise not only in the context of a research trial, but in any setting where therapy is time-limited due to institutional guidelines, clients’ financial constraints, or the dictates of third-party payers. As such, findings underscore the importance of a flexible approach to treatment manuals, and the need to adapt protocols and adherence expectations to individual needs (Kendall, Gosch, Furr, & Sood, 2008).

One way in which CBT might be applied more flexibly is if therapists were to use hostile resistance as a process marker that signals a need to depart from the protocol and responsively modify one’s approach (Constantino, Coyne, & Muir, 2020). Indeed, to the extent that hostile resistance reflects a reaction to the therapist behaviors and interventional styles identified here (e.g., insufficient empathy, rigid adherence, directive strategies), hostile resistance might alert therapists to the need to correct these dynamics. For instance, client hostility might prompt therapists to consider applying more empathy, supportiveness, or other evidence-based protocol departures (see Constantino et al., 2020 for a more extensive discussion of marker-driven responsivity). Although it remains to be tested what specific protocol departures should be used to address hostile resistance in particular, there is substantial evidence for the benefits of integrating motivational interviewing (MI) into CBT in the presence of client resistance, more generally (Westra, Constantino, & Antony, 2016). That directiveness contributed to client hostility in the present study further suggests that MI may be indicated for hostile resistance, as responding to resistance with MI produces better CBT outcome than therapist responses that are more directive (Aviram et al., 2016). Therefore, while more research is needed in this area, an if (marker)-then (departure) approach might help therapists address hostile resistance effectively and sensitively, thereby attenuating its relationship to poor outcome. That rigid adherence to the CBT protocol was a cause of hostile resistance further aligns with this view, pointing to the potential value of more flexible and theoretically integrated treatment approaches (e.g., Gold & Strieker, 2001).

Supplementary Material

Clinical Impact Statement.

Question: Hostile behavior in the therapy room is related to worse outcomes in cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder, but the origins of such behavior remain poorly understood: Which patients become hostile, and why?

Findings: Contrary to the assumption that hostile behavior is simply a product of a hostile patient, the picture is much more complex, with factors related to the therapist and therapy also playing a central role.

Meaning: By identifying several targets for intervention (e.g., empathy failures, inflexible applications of treatment protocols), this study can guide efforts to prevent and address patients’ hostility, and improve clinical outcomes.

Next steps: This investigation presents a novel theoretical framework that can serve as the impetus and foundation for future empirical research.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Sam Rosenberg for his assistance with transcriptions and early development of the qualitative coding system.

Declaration of Interest/Funding: The authors report no conflicts of interest. This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01 MH70918 to Barbara Milrod and R01 MH070664 to Jacques Barber and Dianne Chambless.

Footnotes

Given our aim of elucidating the phenomenon of hostile resistance in the context of a small sample, we implemented an additional review process to ensure that our sample comprised cases for which there was strong agreement that clients’ behavior represented clear hostile resistance. The first and second authors independently reviewed each hostile resistance code from [redacted] and rated whether the behavior rose to the level of hostility. If both raters agreed that the incident did not constitute clear hostile resistance, the code was removed. This resulted in the elimination of 2 of the 10 ever hostile patients in [redacted]. Subsequently, relevant outcomes (attrition, responder status) were consulted for these two patients: Both were found to have good outcomes—bolstering our confidence in the decision to re-designate these patients in order to elucidate the intended effect.

The narcissistic and obsessive designations do not necessarily signify the presence of narcissistic (NPD) or obsessive-compulsive (OCPD) personality disorders, respectively. These codes were based on the observation of behaviors in session, not on diagnostic interviews. Nevertheless, cross-checking these codes with diagnostic data revealed that 2 of 3 qualitatively narcissistic clients met criteria for NPD at baseline, and 2 of 2 obsessive patients met criteria for OCPD.

P5 had in fact had psychodynamic therapy in the past without benefit for his PD. However, he had not had symptom-focused psychodynamic therapy (e.g., Milrod et al., 2016).

P7 enjoyed a strong alliance with his therapist yet went on to become hostile. In our view, their rapport would have been protective had P7’s insight not been so important. Interestingly, the alliance may have protected the patient, who went on to be a therapy responder, from the repercussions of hostile resistance: Being so foreign to their dynamic, P7’s hostility functioned as a wake-up call to his therapist, who subsequently responded by changing course. Their positive working relationship was quickly restored.

Contributor Information

Rachel A. Schwartz, University of Pennsylvania, Dept. of Psychology, 425 S. University Ave., Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Dianne L. Chambless, University of Pennsylvania, Dept. of Psychology, 425 S. University Ave., Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Barbara Milrod, Weill Cornell Medical College, 525 East 68th St., New York, NY 10065, USA.

Jacques P. Barber, Adelphi University, Gordon F. Derner School of Psychology, 158 Cambridge Ave., Garden City, NY 11530-0701.

References

- Ahmed M, Westra HA, & Constantino MJ (2012). Early therapy interpersonal process differentiating clients high and low in outcome expectations. Psychotherapy Research, 22(6), 731–745. 10.1080/10503307.2012.724538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach C, & Silverstein LB (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis: NYU press. [Google Scholar]

- Aviram A, Westra HA, Constantino MJ, & Antony MM (2016). Responsive Management of Early Resistance in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 783–794. 10.1037/ccp0000100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Davis DD, & Freeman A (2015). Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders (Third ed.): Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE, Moleiro C, & Talebi H (2002). Resistance in psychotherapy: What conclusions are supported by research. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(2), 207–217. 10.1002/jclp.1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Gallagher MW, Sauer-Zavala SE, Bullis J, Gorman JM, Shear MK, … Barlow DH (2013). Patient characteristics and variability in adherence and competence in cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 443–454. 10.1037/a0031437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassiello-Robbins C, Conklin LR, Anakwenze U, Gorman JM, Woods SW, Shear MK, & Barlow DH (2015). The effects of aggression on symptom severity and treatment response in a trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 60, 1–8. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, & Salkovskis P (2009). Panic disorder: Manual for Improving Access to Psychological Therapy High Intensity CBT Therapists. Retrieved from https://oxcadatresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Cognitive-Therapy-for-Panic-Disorder_IAPT-Manual.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Constantino MJ, Coyne AE, & Muir HJ (2020). Evidence-based therapist responsivity to disruptive clinical process. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Barlow DEL, & Meadows EA (2000). Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic. Therapist Guide for Anxiety, Panic, and Agoraphobia: TherapyWorks. [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks CF, Muran JC, & Safiran JD (2018). Alliance rupture repair: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 508–519. 10.1037/pst0000185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Grandi S, Rafanelli C, Saviotti FM, Ballin M, & Pesarin F (1993). Hostility and irritable mood in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 29(4), 213–217. 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90010-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley SH, OMalley S, Rounsaville B, Prusoff BA, & Weissman ΜM (1987). The relationship of patient difficulty to therapist performance in interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 12(3), 207–217. 10.1016/0165-0327(87)90029-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis N, Rollnick S, McCambridge J, Butler C, Lane C, & Hood K (2005). When smokers are resistant to change: Experimental analysis of the effect of patient resistance on practitioner behaviour. Addiction, 700(8), 1175–1182. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JD, & Frank JB (1991). Persuasion and healing . Baltimore, MD: J: Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gold J, & Stricker G (2001). A relational psychodynamic perspective on assimilative integration. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 11(1), 43–58. 10.1023/A:1026676908027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RA, Ball S, Kaspi SP, Otto MW, Pollack MH, Shekhar A, & Fava M, (1996). Prevalence and correlates of anger attacks: A two site study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 39(1), 31–38. 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00017-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara KM, Westra HA, Constantino MJ, & Antony MM (2018). The impact of resistance on empathy in CBT for generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 28(4), 606–615. 10.1080/10503307.2016.1244616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry WP, Schacht TE, & Strupp HH (1990). Patient and therapist introject, interpersonal process, and differential psychotherapy outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58(6), 768–774. 10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs TJ (1999). Countertransference past and present: A review of the concept. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 80(3), 575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Gosch E, Furr JM, & Sood E (2008). Flexibility within fidelity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(9), 987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loerinc AG, Meuret AE, Twohig MP, Rosenfield D, Bluett EJ, & Craske MG (2015). Response rates for CBT for anxiety disorders: Need for standardized criteria. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 72–82. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz JC, & Milrod BL (2011). The importance of responding to negative affect in psychotherapies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(2), 124–128. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change: Guilford press. [Google Scholar]

- Milrod B, Chambless DL, Gallop R, Busch FN, Schwalberg M, McCarthy KS, … Barber JP (2016). Psychotherapies for panic disorder: A tale of two sites. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(7), 927–935. 10.4088/JCP.14m09507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch DA, McCabe RE, Antony MM, Rocca L, & Swinson RP (2008). Anger experience and expression across the anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 25(2), 107–113. 10.1002/da.20280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, & Rollnick S (2002). A motivational interviewing perspective on resistance in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(2), 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC, & Lambert MJ (2019). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Volume 1: Evidence-based therapist contributions: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porter E, & Chambless DL (2015). A systematic review of predictors and moderators of improvement in cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder and agoraphobia. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 179–192. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie DL (1994). Clients' accounts of resistance in counselling: A qualitative analysis. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 28(1), 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, … Papp LA (1997). Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(11), 1571–1575. 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE (2015). How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 270–277. 10.1002/wps.20238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JC, & McMullen EJ (2005). An examination of therapist and client behavior in high-and low-alliance sessions In cognitive-behavioral therapy and process experiential therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 42(3), 297. [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Aviram A, Connors L, Kertes A, & Ahmed M (2012). Therapist emotional reactions and client resistance in cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychotherapy, 49(2), 163–172. 10.1037/a0023200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Aviram A, Kertes A, Ahmed M, & Connors L (2009). Manual for coding resistance in CBTfor anxiety. Unpublished manual. Department of Psychology, York University. Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, & Norouzian N (2018). Using motivational interviewing to manage process markers of ambivalence and resistance in cognitive behavioral therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(2), 193–203. 10.1007/s10608-017-9857-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Constantino MJ, & Antony MM (2016). Integrating motivational interviewing with cognitive-behavioral therapy for severe generalized anxiety disorder: An allegiance-controlled randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(9), 768–782. 10.1037/ccp0000098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickgraf HF, Chambless DL, McCarthy KS, Gallop R, Sharpless BA, Milrod BL, & Barber JP (2015). Interpersonal factors are associated with lower therapist adherence in cognitive-behavioural therapy for panic disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 272–284. 10.1002/cpp.1955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.