Abstract

Objective:

Couples with concordant drinking patterns have higher relationship satisfaction and greater relationship stability over time. Emerging evidence suggests that episodes of drinking with one’s intimate partner can have positive immediate consequences for relationship functioning whereas drinking episodes without partner do not. The present ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study examined the impact of drinking with partner (DWP) and drinking without partner (DWOP) events on immediate and next-day self-reported relationship harmony and discord.

Method:

Heterosexual, cohabiting community couples with congruent drinking patterns, ages 21 – 35 (N = 191), made three random reports each day for 30 days. Multilevel modeling was used to examine the impact of DWP and DWOP events on momentary relationship functioning, controlling for quantity of alcohol consumed and for functioning at the previous report.

Results:

As hypothesized, harmony increased immediately after DWP (but not after DWOP) compared with no drinking for men and women. There were no immediate effects of drinking on discord. There were also positive effects of DWP on next morning harmony but these were specific to women’s drinking reports. Women’s DWP and DWOP predicted reduced next morning discord for men; however, men’s and women’s discord increased as women consumed more drinks the previous evening.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that concordant drinking couples may achieve immediate benefits for couple harmony from drinking together. Women’s drinking appears to be more impactful than men’s on next-day harmony and discord, with greater harmony following women’s evening DWP but increased discord associated with heavier evening drinking by women.

Keywords: alcohol drinking, relationship quality, ecological momentary assessment, intimacy

Alcohol use within marriage and intimate relationships has traditionally been associated with poor relationship functioning, including divorce and partner aggression (see Marshal, 2003 for a review). Yet, a growing number of studies find that couples with congruent drinking patterns and couples who drink together (as opposed to apart) enjoy better long-term relationship outcomes than couples with discordant drinking patterns (Foulstone et al., 2016; Homish & Leonard, 2005; 2007; see Rodriguez & Derrick, 2017 for a review). Examining the short-term positive and negative consequences of partner drinking episodes may help in understanding longer-term relationship outcomes associated with couple drinking. Do couples experience improved – or impaired – relationship functioning immediately or shortly after drinking? The present ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study examined the short-term effects of drinking events – with and without partner - on same-day and next-day relationship functioning within a sample of moderate-to-heavy drinking community couples.

Positive Acute Effects of Alcohol Consumption on Social Functioning

Alcohol is widely believed to enhance and facilitate social interactions. These expectancies contribute positively to consumption (Brown et al., 1980; Cooper et al., 2016) and enhance the perceptions of pleasure that result from drinking (Treloar et al., 2015). Experimental research supports the rewarding and anxiety-attenuating effects of administered alcohol (Gilman et al., 2008). In a rare study of the acute effects of alcohol on social interaction, Sayette and colleagues (2012) found that participants who consumed alcohol in groups of unacquainted people displayed increased smiling and behaviors associated with positive affect and reported greater social bonding.

Daily report studies also support the notion that drinking events increase short-term positive affect and reduce negative affect (e.g., Treloar et al., 2015; Trull et al., 2016). In a series of studies involving event-contingent recording over several days, aan het Rot and colleages (2008) found that social interactions that followed alcohol consumption included more positive affect and agreeable behavior compared with interactions without alcohol. Cronce and colleagues (2020) also used EMA to examine the same-day and next-day effects of drinking events, social events, and the interaction of drinking with social events on affect. College student participants reported more positive and less negative affect on days in which they drank alcohol and on days they reported a social interaction. Not surprisingly, there was a high overlap between the two kinds of events. However, in apparent contrast to aan het Rot et al. (2008), alcohol did not enhance the positive effects of social interaction. The positive immediate consequences of drinking did not extend to the next day. However, social interactions led to more positive and less negative affect both the same day and the next day, suggesting that it may be the social interaction rather than the alcohol often included in those events, that has the more robust positive consequences.

Do the positive acute effects of drinking on affect and social interactions in general extend to couples’ drinking and functioning? Because alcohol is usually consumed with others (Cronce et al., 2020), and intimate couples spend a lot of time together, it is not surprising that partners drink with each other more often than they drink with other people (Birditt et al., 2019). Drinking quantity and frequency are usually concordant within intimate partnerships (Meiklejohn et al., 2012), and congruent drinking patterns are associated with higher relationship satisfaction (Homish & Leonard, 2007; Meiklejohn et al., 2012). Conversely, discrepant couple drinking patterns are associated with lower relationship satisfaction (Homish & Leonard, 2007; Homish et al., 2009) and divorce (Leonard et al., 2014; Torvik et al., 2013). The positive consequences of congruent relative to discrepant couple drinking patterns may reflect partner similarity (Gonzaga et al., 2007) or the positive impact of spending time together engaged in shared leisure activities including drinking (Girme et al., 2014).

It is also plausible that the positive long-term effects of congruent drinking partnerships result from positive short-term consequences of individual occasions of drinking with one’s partner, such as increased intimacy. These positive immediate consequences may reinforce drinking together and accumulate over time to contribute to higher relationship satisfaction. A few daily report studies support the hypothesis that drinking with partner (DWP), but not drinking without partner (DWOP), contributes to positive short-term couple outcomes. Among community couples with congruent drinking patterns, Testa and colleagues (2019) found that DWP episodes, but not DWOP episodes, increased the likelihood of reporting a partner intimacy experience in the next three hours compared with no drinking. Intimacy experiences were defined as a meaningful conversation or experience of emotional or physical intimacy with partner. Many intimacy experiences occurred at the same hour as drinking, suggesting a close or even deliberate coupling of the two events, for example, drinking in order to achieve intimacy. Relatedly, Levitt and Cooper (2010) found that when women felt less close to their partner in the morning, they were more likely to report drinking with partner later that day.

There is also evidence for positive next-day effects of DWP on relationship functioning. In a daily report study of college student couples, morning reports of perceived intimacy with partner were higher the day after DWP compared with days following DWOP or no drinking (Levitt & Cooper, 2010). Intimacy on days following DWOP did not differ from days of no drinking. Similarly, Levitt et al. (2014) found that DWP compared to DWOP events predicted higher ratings of closeness and getting along with partner and lower ratings of anger and arguing with partner the next day. Days of no drinking were not included in this analysis.

Negative Acute Consequences of Alcohol Consumption on Relationship Functioning

Despite evidence for positive relationship consequences following couple drinking events, a separate body of research maintains that alcohol consumption has short-term negative consequences, including conflict and interpersonal aggression. Laboratory analog studies support a positive effect of administered alcohol on aggression following provocation for men and women (see Crane et al., 2016; Crane et al., 2017 for meta-analytic reviews). Daily diary studies also provide evidence that drinking episodes increase the likelihood that an episode of psychological or physical partner aggression will follow later that day (Moore et al., 2011; Rothman et al., 2018; Shorey et al., 2014; Stappenbeck et al., 2016). Among a sample of community couples, Crane and colleagues (2014) found that evening reports of arguing with partner were higher than typical on days that included an episode of heavy episodic drinking (4 drinks for women, 5 for men) relative to days of no heavy drinking. Using the same dataset, Testa and Derrick (2014) found that a drinking episode by either partner increased the likelihood of conflict, psychological, and physical aggression in the next four hours. Although they did not consider the impact of drinking together versus apart on subsequent conflict, they did consider the interaction between male and female reports of drinking within each four-hour block and found none; drinking together had no unique contribution (either exacerbation or mitigation) beyond drinking by either partner.

It is curious that couple drinking episodes contribute both to intimacy and to discord in the short term. Drinking together as opposed to drinking apart from partner may play a role, and not all studies have considered this distinction. However, given that aggression occurs when partners are physically together and often involves alcohol (Reingle et al., 2014), it is likely that under some circumstances (e.g., a stressful day, an earlier disagreement), drinking episodes contribute to arguments. Because acute alcohol consumption reduces cognitive and behavioral inhibition as well as anxiety, it may increase the likelihood of either increased intimacy or conflict, depending upon the circumstances surrounding a particular drinking episode and the most salient cues (Giancola et al., 2009).

The amount of alcohol consumed may also contribute to the outcome of a drinking episode. A drink or two with one’s partner may facilitate feelings of intimacy; however, high levels of consumption may compromise cognitive processing and inhibition (Steele & Southwick, 1985), increasing the likelihood of arguments and aggression (Leonard & Quigley, 2017). Accordingly, Levitt and Cooper (2010) found that consuming fewer drinks was associated with increased perceptions of relationship intimacy, whereas consuming heavier amounts was associated with decreased intimacy. The match between partner drinking amount was also relevant in that study. Consuming large amounts of alcohol resulted in greater perception of negative relationship events when the partner drank lightly but not when the partner also drank large amounts. High female consumption coupled with low male consumption led to particularly poor outcomes relative to other partner consumption combinations.

The Present Study

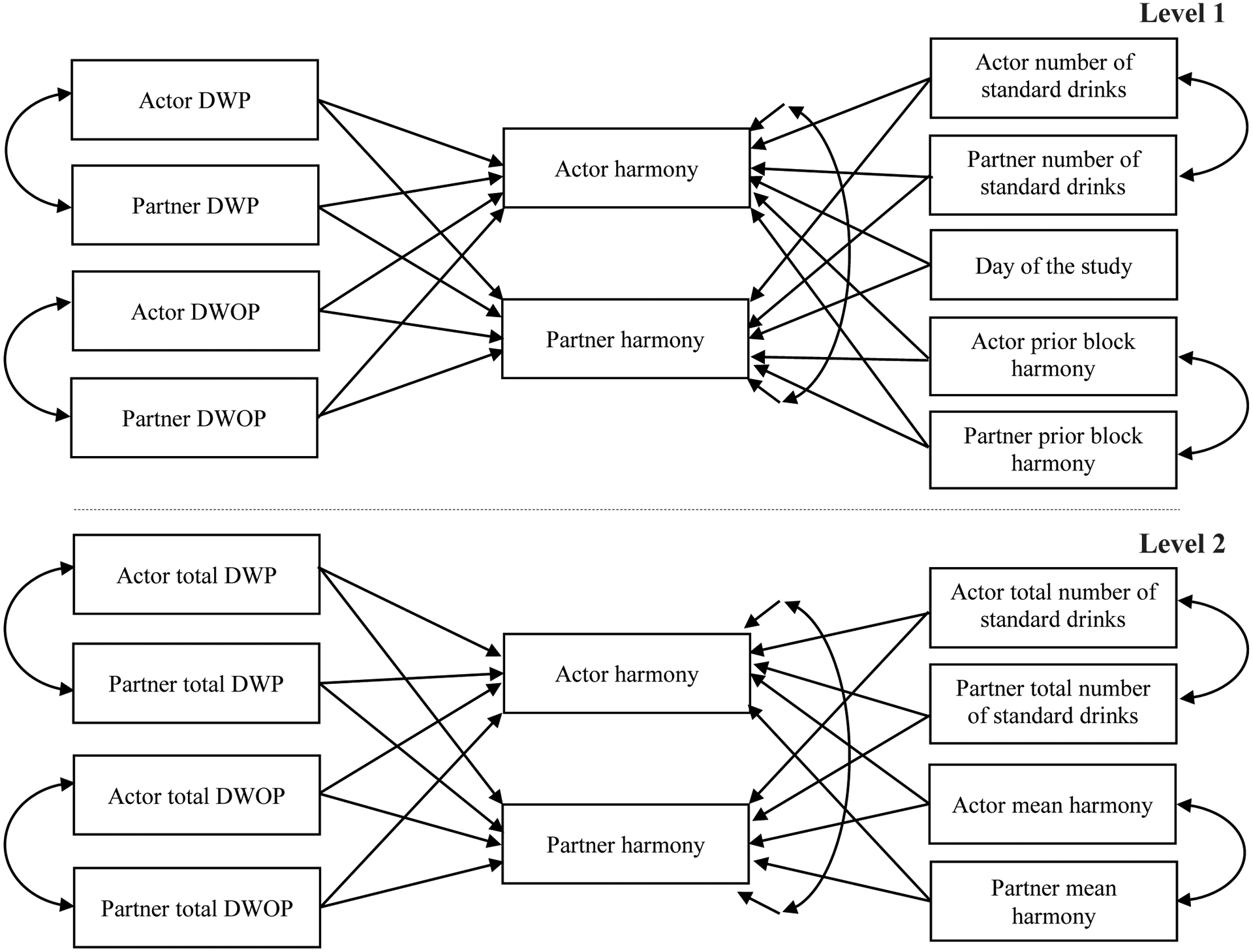

The present dyadic ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study was designed to expand upon limited existing knowledge regarding the acute effects of drinking episodes on relationship functioning: feelings of closeness and harmony with one’s partner as well as relationship discord (anger and arguing). We considered the impact of drinking with partner (DWP) events separate from the effects of drinking without partner (DWOP) events. The availability of independent reports from each partner allowed us to consider the effects of partner drinking reports in addition to self-reports of drinking (see Figure 1) on each partner’s perceived couple functioning. We hypothesized that DWP events would result in immediate positive effects on self-reported relationship harmony (Hypothesis 1) and negative effects on discord (Hypothesis 2) relative to no drinking. Prior studies have not documented any effects of DWOP relative to no drinking (Levitt et al., 2014; Testa et al., 2019), hence we offered no hypothesis regarding DWOP. We controlled for number of drinks in all analyses, anticipating that greater consumption would result in more negative relationship outcomes (Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Stappenbeck et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Level 1 and Level 2 predictors of Actor and Partner Positive Relationship Functioning

Prior studies using once-daily reports examined next-day consequences (Levitt & Cooper, 2010) or immediate consequences (i.e., next few hours) of drinking episodes on specific couple events (e.g., conflict, Testa & Derrick, 2014; intimacy, Testa et al., 2019). Our EMA data allowed us to consider both immediate and next-day effects of drinking events. Consistent with studies documenting positive effects of DWP relative to DWOP on next-day functioning (Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Levitt et al., 2014), we hypothesized that evening DWP would have positive effects on next morning harmony (Hypothesis 3) and negative effects on morning discord (Hypothesis 4), We offered no hypotheses regarding DWOP relative to no drinking. Although we hypothesized the same pattern of results for immediate and next-day consequences of drinking, the availability of data for both timepoints allowed us to consider whether any differences in patterns emerged. For example, DWP effects on harmony may be more prominent immediately after drinking relative to the next morning.

Although the primary focus was on relationship functioning, concurrent reports of affect at each report allowed us to explore the acute effects of DWP and DWOP on positive and negative affect and to consider whether effects mirror those observed for harmony and discord. Drinking has been associated with short-term increases in positive affect (aan het Rot et al., 2008) and decreases in negative affect (Treloar et al., 2015). However, because no prior studies have considered DWP and DWOP events separately, we offered no hypotheses regarding effects of DWP and DWOP on affect.

Method

Recruitment and Participants

Participants included 191 married or cohabiting heterosexual couples recruited from the community to participate in a 30-day EMA study involving randomly signaled, independent partner reports completed 3 times daily. Facebook advertisements sought couples, ages 21–35, who drink alcohol, for a study of daily couple interactions. Clicking the ad allowed respondents to complete a brief online screener (assessing age, relationship status, and alcohol use). If initial eligibility criteria were met, the respondent was given the opportunity to provide contact information. All couples were screened fully for eligibility by telephone. If the first partner met eligibility criteria, the second partner was screened independently for eligibility and interest. Most couples were recruited directly via Facebook (160/191, 83.8%); the rest were referred by previous participants (22/191, 11.5%) or by others (9/191, 4.7%).

To be eligible, both partners had to be between 21 and 35 years old and either married or cohabiting for at least six months. Gender was assessed during screening (male or female) but gender composition of the couple was not a criterion for exclusion. Both partners were required to drink at least twice weekly, with at least two episodes of heavy episodic drinking (4+ drinks for women, 5+ for men) per month; thus, the sample consists of congruent heavy drinking couples. In addition, both partners had to report perpetrating or receiving verbal aggression within the past year (e.g., yelled) or at least one partner had to report perpetrating or receiving physical aggression (pushed/shoved, threw something at partner, other physical aggression) in the past year (Subramani et al., 2017). These criteria were chosen to ensure a sample with sufficient episodes of drinking and variability in daily relationship functioning. Because psychopathology or stimulant use may increase violence, couples were excluded if either partner reported psychiatric treatment or use of cocaine or stimulants. Pregnant women were excluded. For safety reasons, couples were excluded if either partner reported intimate partner aggression that caused fear for one’s life or required medical care; they were provided referral information. Of 609 couples screened by telephone, 252 (41.4%) met eligibility criteria and 197 participated in the study. The most common reasons for ineligibility were absence of aggression (45%) or insufficient drinking (34%). Same-sex couples were eligible to participate; however, because only one same-sex male couple and five same-sex female couples did so, we opted to omit them from analyses, allowing us to analyze the data as distinguishable dyads (based on gender, Kashy & Donnellan, 2012; Kenny et al., 2006).

Most couples were cohabiting (61.5%) rather than married (38.5%), with average length of cohabitation (or marriage) of 3.88 years (range = 0.33 – 15.17, SD = 3.12). Men averaged 29.03 (SD = 3.56) and women 27.81 (SD = 3.39) years of age. Most participants self-identified as White (350/382, 91.6%), were employed full- or part-time (94.8% of men and 88.5% of women), and had a bachelors’ degree or higher (59.2% of men, 77.0% of women). Median personal income was $35,000 – $44,999 for both men and women.

Procedures

Eligible couples completed an in-person orientation that lasted about 1.5 hours. Partners were escorted to separate, private interview rooms for informed consent procedures and completion of baseline questionnaires. Couples were reunited for instruction on how to make independent, confidential daily reports on a secure web-based portal via smartphone. Most used their own phone (358/382, 93.7%), but participants could borrow a study-provided phone if necessary. Participants were instructed to respond to three random prompts each day for 30 consecutive days. Each report took an average of 3.13 minutes (SD = 3.83) to complete. Random prompts were typically sent between 10 AM – 2 PM, 2 PM – 6 PM, and 6 PM – 10 PM, with no less than 2 hours between them, and could be delayed up to 60 minutes if necessary. In a small number of cases, times of the reports were adjusted to conform to personal schedules (e.g., night shift). Partners were prompted independently; hence the times of their reports do not coincide. Participants were compensated $50 for completion of baseline questionnaires plus $1 for each random report completed and a bonus based on random report completion rate (e.g., 90% complete reports yielded $140 bonus) for a possible maximum of $280. All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board.

Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA)

EMA items have been used previously in daily report studies of substance use and couple functioning (e.g., Crane et al., 2014; Testa et al., 2019a; 2019b).

Couple functioning was assessed on each report. Two items assessed harmony: “How close do you feel toward your partner right now?” and “Since your last report, how well have you been getting along with your partner?” Two items assessed relationship discord: “How angry or irritated do you feel toward your partner right now?” and “Since your last report, how much did you argue with your partner?” Items were assessed using 7-point scales ranging from not at all (0) to very much/very well (6). The close and getting along items were combined as an indicator of harmony (r = 0.73), and the anger and argue items were combined as an indicator of discord (r = 0.61). Harmony and discord were negatively correlated (r = −0.57) within report.

Positive and negative affect.

Each report also included items assessing current positive (happy, energetic; r = 0.46) and negative affect (angry, sad, anxious; α = 0.75), measured on 0 (not at all) to 6 (very much) scales. Within-report positive and negative affect composites were negatively correlated (r = −0.42).

Alcohol consumption.

In each report, participants were asked whether they had consumed alcohol since their last report. If so, follow-up questions assessed the time drinking began, number of drinks consumed, and whether partner was present and drinking at the time. This permitted categorization of drinking episodes as drinking with partner (DWP, partner present and drinking) or drinking without partner (DWOP, partner not present or present but not drinking).

Questionnaire Measures

The questionnaire completed during orientation included the following demographic questions: date of birth, gender (male or female), race, education, employment status, personal income, marital status (cohabiting or married), and length of marriage or cohabitation.

Analytic Strategy

Given the interdependent nature of partners’ reports within couples, we modeled equations for men and women simultaneously. We performed multivariate multilevel modeling with random intercepts using MPlus Version 8.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Bayesian estimation was chosen because it neither requires nor assumes that parameters are normally distributed (Muthén et al., 2016; van de Schoot et al., 2014). The Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM, Kashy & Snyder, 1995; Kenny et al., 2006) permitted modeling of the effects of each person’s own drinking (Actor paths) and the effects of partner’s drinking (Partner paths) on each person’s self-reported couple functioning. Agreement in dyadic reports of relationship events is typically low (e.g., Testa et al., 2019a) but was further limited in this case because times of partner reports did not coincide. Actor reports of drinking events are more relevant as predictors of one’s own relationship functioning, given that they represent the individual’s own perception and recollection of recent drinking events. Accordingly, some researchers have chosen to omit Partner effects from analyses (Levitt et al., 2014). Because these are dyadic data, we include Partner effects for completeness, but note their limitations.

At Level 1 (the event level), we included as predictors of current relationship functioning each partner’s report of DWP and DWOP since the last EMA. DWP and DWOP episodes were categorical variables (versus no drinking) and uncentered. We also controlled for number of drinks consumed since the last report (person-mean centered). Since reports close in time are likely to be correlated (Wickham & Knee, 2013), we controlled for lagged Actor and Partner self-reported functioning from the prior EMA report, person-mean centered. Thus, relationship functioning levels represent deviations from one’s own respective mean. Day of the study (1 – 30, grand mean centered) was entered at Level 1 to control for potential unmeasured temporal confounds. At Level 2 (the couple level), we controlled for each partner’s mean harmony and discord and number of DWP and DWOP episodes over the 30 study days, allowing us to account for between-person effects and to distinguish within-person effects from between-person effects. All Level-2 variables were grand mean centered (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Level 1 and Level 2 effects are depicted in Figure 1.

Results

Descriptive Data

Table 1 presents descriptive data for the morning, afternoon, and evening daily reports which were completed, on average, at 11:22 AM, 3:35 PM, and 7:41 PM, respectively. EMA compliance was excellent; 31,279/34,380 possible reports were completed (91.0%). Women completed more reports (83.64/90, SD = 5.49; 92.9%) than men (81.69/90, SD = 7.51; 90.8%), t(31,277) = −26.311, p < .001; however, there was no difference in completion by time of report. Across the three daily reports, average harmony ratings were high (M = 4.89/6, SD = 1.39) and discord ratings were low (M = 0.54/6, SD = 1.07). Within each individual’s report, harmony and discord were negatively correlated, −0.59 < r < −0.54. Male and female partner functioning were correlated (0.37 < r < 0.42) for harmony and (0.28 < r < 0.37) for discord within reports.

Table 1.

Alcohol Use and Couple Relationship Functioning: Morning, Afternoon, Evening Reports

| Variable | Morning (N = 10,399) | Afternoon (N = 10,410) | Evening (N = 10,470) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Time completed (1–24 Hour), M (SD) | 11.43 (1.50) | 11.29 (1.51) | 15.67 (1.50) | 15.51 (1.50) | 19.77 (1.48) | 19.59 (1.47) |

| Relationship harmony1, M (SD) | 4.87 (1.41) | 4.89 (1.38) | 4.88 (1.40) | 4.91 (1.37) | 4.88 (1.42) | 4.91 (1.37) |

| Relationship discord2, M (SD) | 0.58 (1.07) | 0.60 (1.13) | 0.47 (0.98) | 0.46 (1.03) | 0.56 (1.10) | 0.55 (1.12) |

| Positive affect | 3.66 (1.40) | 3.50 (1.38) | 3.69 (1.40) | 3.50 (1.36) | 3.60 (1.39) | 3.45 (1.37) |

| Negative affect | 0.82 (1.07) | 0.93 (1.16) | 0.81 (1.08) | 0.93 (1.16) | 0.75 (1.08) | 0.86 (1.15) |

| Alcohol use episodes, N | 1,660 | 1,560 | 796 | 671 | 2,021 | 1,939 |

| Time drinking began3 (1–24 Hour), M (SD) | 19.00 (3.94) | 18.95 (3.67) | 14.68 (2.99) | 14.82 (2.90) | 17.79 (2.50) | 17.80 (2.34) |

| Drink with partner (DWP) episodes, N | 998 | 1,135 | 428 | 451 | 1,199 | 1,373 |

| Number of standard drinks, DWP episodes, M (SD) | 4.94 (2.94) | 3.81 (2.55) | 3.29 (2.42) | 2.77 (2.03) | 3.48 (2.39) | 2.75 (1.94) |

| Drink without partner (DWOP) episodes | 662 | 425 | 368 | 219 | 821 | 565 |

| Number of standard drinks, DWOP episodes, M (SD) | 3.62 (2.51) | 3.05 (2.30) | 2.80 (2.19) | 2.19 (1.90) | 2.95 (2.13) | 2.21 (1.46) |

Average of how close to partner, how well get along with partner

Average of anger toward partner, arguing with partner

Drinking episodes since completing the prior report

Descriptive data are provided in Table 1. Across the 30 days of reporting, men reported 4,477 drinking episodes (M = 23.44) and women reported 4,170 (M = 21.83). Most drinking episodes were classified as DWP (n = 5,584, 64.6%). The remainder, labeled DWOP events, included drinking when partner was not present (n = 1,962, 22.7%) and drinking when partner was present but not drinking (n = 1,098, 12.7%). The proportion of DWP episodes reported by women (71.0%) was higher than that reported by men (58.6%) but varied little by time of report (67.3 – 72.8% for women; 53.8 – 60.1% for men). On average, each drinking episode included 3.65 drinks (SD = 2.59) for men and 2.97 (SD = 2.19) for women. DWP events included more drinks than DWOP events (M = 3.56, SD = 2.52 versus M = 2.90, SD = 2.19), t(8,632) = −12.103, p < .001. Morning reports of drinking, which included primarily prior evening drinking events, involved more drinks (M = 4.02, SD = 2.72) than afternoon (M = 2.84, SD = 2.20) and early evening reports (M = 2.94, SD = 2.11).

Does Drinking Predict Immediate Relationship Functioning?

The first set of analyses considered the immediate consequences of DWP and DWOP events on relationship harmony and discord, controlling for the number of drinks consumed. These analyses used afternoon and evening reports combined; however, results were identical when analyzed separately for afternoon and evening reports. Drinking episodes reported in these EMAs occurred on average about 2 hours prior, and generally not more than four hours prior, to self-reported relationship functioning (see Table 1). In contrast, morning reports typically included drinking episodes that occurred the previous evening, 12 or more hours prior to the report.

As shown in Table 2, and consistent with Hypothesis 1, there were significant positive Actor effects of DWP on immediate male- and female-reported relationship harmony. The Partner DWP effect was also significant for female reports though not for male reports. DWOP did not have any significant effects on immediate harmony; however, there was a significant negative effect of Partner drinking quantity on female harmony. In contrast, there were no significant effects of DWP, DWOP, or number of drinks on immediate discord, providing no support for Hypothesis 2. Thus, the pattern of results for discord was not merely the reverse of the effects on harmony.

Table 2.

Short-Term Relationship Functioning as a Function of Drinking With and Without Partner (Afternoon and Evening Reports)

| Variable | Male-reported harmony | Female-reported harmony | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 4.824 (0.012)*** | [4.805, 4.851] | 4.840 (0.011)*** | [4.818, 4.862] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.169 (0.042)*** | [0.087, 0.250] | 0.183 (0.041)*** | [0.104, 0.264] |

| Partner alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.066 (0.040) | [−0.013, 0.144] | 0.163 (0.042)*** | [0.081, 0.244] |

| Actor alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.070 (0.038) | [−0.004, 0.145] | −0.019 (0.044) | [−0.107, 0.069] |

| Partner alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | −0.006 (0.043) | [−0.090, 0.079] | 0.075 (0.039) | [−0.002, 0.151] |

| Actor number of standard drinks | −0.006 (0.008) | [−0.022, 0.011] | −0.010 (0.011) | [−0.031, 0.011] |

| Partner number of standard drinks | −0.020 (0.011) | [−0.042, 0.000] | −0.020 (0.008)* | [−0.037, −0.004] |

| Actor prior report relationship harmony | 0.308 (0.011)*** | [0.287, 0.329] | 0.375 (0.010)*** | [0.355, 0.394] |

| Partner prior report relationship harmony | 0.100 (0.010)*** | [0.080, 0.119] | 0.085 (0.011)*** | [0.063, 0.107] |

| Day of the study1 | −0.004 (0.001)*** | [−0.006, −0.002] | −0.006 (0.001)*** | [−0.008, −0.004] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total DWP episodes over 30 days | −0.004 (0.003) | [−0.010, 0.002] | −0.004 (0.003) | [−0.010, 0.003] |

| Partner total DWP episodes over 30 days | 0.000 (0.004) | [−0.007, 0.006] | −0.003 (0.002) | [−0.008, 0.002] |

| Actor total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.001 (0.003) | [−0.007, 0.004] | 0.000 (0.004) | [−0.007, 0.007] |

| Partner total DWOP episodes over 30 days | 0.001 (0.003) | [−0.008, 0.006] | −0.002 (0.003) | [−0.007, 0.004] |

| Actor total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] |

| Partner total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] | 0.000 (0.000) | [−0.001, 0.001] |

| Actor mean relationship harmony over 30 days | 0.993 (0.011)*** | [0.976, 1.016] | 0.998 (0.013)*** | [0.974, 1.023] |

| Partner mean relationship harmony over 30 days | 0.002 (0.010) | [−0.018, 0.023] | 0.000 (0.011) | [−0.022, 0.020] |

| Variable | Male-reported discord | Female-reported discord | ||

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 0.529 (0.013)*** | [0.501, 0.549] | 0.501 (0.014)*** | [0.477, 0.526] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.039 (0.039) | [−0.039, 0.117] | −0.002 (0.041) | [−0.080, 0.079] |

| Partner alcohol use with partner (DWP) | −0.017 (0.038) | [−0.092, 0.058] | 0.040 (0.042) | [−0.043, 0.126] |

| Actor alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.047 (0.035) | [−0.023, 0.116] | 0.016 (0.042) | [−0.066, 0.101] |

| Partner alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.007 (0.041) | [−0.071, 0.089] | 0.050 (0.039) | [−0.028, 0.129] |

| Actor number of standard drinks | −0.003 (0.008) | [−0.018, 0.013] | 0.014 (0.010) | [−0.007, 0.034] |

| Partner number of standard drinks | 0.013 (0.010) | [−0.007, 0.033] | −0.002 (0.008) | [−0.018, 0.014] |

| Actor prior report relationship discord | 0.204 (0.011)*** | [0.182, 0.225] | 0.218 (0.010)*** | [0.198, 0.239] |

| Partner prior report relationship discord | 0.058 (0.010)*** | [0.039, 0.078] | 0.063 (0.012)*** | [0.041, 0.087] |

| Day of the study1 | −0.002 (0.001) | [−0.004, 0.000] | −0.002 (0.001) | [−0.004, 0.000] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total DWP episodes over 30 days | −0.002 (0.003) | [−0.006, 0.004] | 0.000 (0.004) | [−0.007, 0.007] |

| Partner total DWP episodes over 30 days | 0.000 (0.003) | [−0.006, 0.006] | −0.001 (0.003) | [−0.006, 0.007] |

| Actor total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.002 (0.002) | [−0.005, 0.003] | 0.001 (0.003) | [−0.007, 0.007] |

| Partner total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.001 (0.003) | [−0.007, 0.006] | −0.001 (0.003) | [−0.006, 0.005] |

| Actor total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] |

| Partner total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] |

| Actor mean relationship discord over 30 days | 0.995 (0.017)*** | [0.963, 1.030] | 1.000 (0.019)*** | [0.960, 1.037] |

| Partner mean relationship discord over 30 days | −0.001 (0.019) | [−0.032, 0.040] | 0.005 (0.020) | [−0.033, 0.046] |

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Day of the study (1–30)

DWP = drink with partner, DWOP = drink without partner

In this analysis and in others reported below, level of Actor and Partner relationship functioning reported at the prior report was a significant and robust contributor to current functioning indicating that perceived harmony and discord tend to persist from one report to the next. Also, men’s and women’s reports reflect their Partner’s prior functioning as well as their own. In this and all subsequent analyses, there were also robust Level 2 Actor effects of mean harmony and discord (e.g., those with higher overall harmony reported higher harmony at a given EMA). At Level 2 we also considered the between-person (Level 2) effects of number of DWP and DWOP events over 30 days but found no significant effects in any analysis. Thus, Level 1 DWP and DWOP effects are within-person effects and not the result of between-participant differences in the frequency of these events.

Affect was assessed at the same time as relationship functioning and was moderately correlated (e.g., positive affect correlated r = 0.40 with harmony and r = −.25 with discord; negative affect correlated r = −0.35 with harmony and r = 0.44 with discord). Although we offered no a priori hypotheses regarding the effects of DWP and DWOP events on positive and negative affect, these data allowed us to explore whether effects of drinking events on affect mirrored their effects on relationship functioning. As shown in Table 3, DWP but not DWOP increased immediate positive affect for men and women, mirroring Table 2 results for harmony. For negative affect the pattern was quite different from the corresponding pattern for discord (where we observed no significant effects). Actor DWP and female DWOP reduced negative affect for men and women. Also, women’s DWOP decreased negative affect for men and women whereas women’s drinking quantity increased negative affect. Thus, drinking had broader consequences for immediate positive and negative affect than it did for relationship functioning.

Table 3.

Short-Term Positive and Negative Affect as a Function of Drinking With and Without Partner (Afternoon and Evening Reports)

| Variable | Male-reported positive affect | Female-reported positive affect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 3.587 (0.018)*** | [3.555, 3.621] | 3.405 (0.015)*** | [3.374, 3.431] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.132 (0.045)** | [0.042, 0.220] | 0.207 (0.046)*** | [0.117, 0.300] |

| Partner alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.127 (0.046)** | [0.036, 0.216] | 0.170 (0.047)*** | [0.079, 0.265] |

| Actor alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.025 (0.042) | [−0.060, 0.107] | 0.077 (0.047) | [−0.016, 0.170] |

| Partner alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.099 (0.049)* | [0.001, 0.193] | −0.028 (0.045) | [−0.113, 0.062] |

| Actor number of standard drinks | 0.020 (0.009)* | [0.003, 0.037] | 0.017 (0.012) | [−0.007, 0.040] |

| Partner number of standard drinks | −0.027 (0.012)* | [−0.050, −0.003] | −0.006 (0.010) | [−0.025, 0.013] |

| Actor prior report positive affect | 0.267 (0.010)*** | [0.247, 0.288] | 0.317 (0.010)*** | [0.298, 0.337] |

| Partner prior report positive affect | 0.039 (0.009)*** | [0.021, 0.057] | 0.034 (0.011)** | [0.012, 0.056] |

| Day of the study1 | −0.006 (0.001)*** | [−0.008, −0.004] | −0.005 (0.001)*** | [−0.007, −0.002] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total DWP episodes over 30 days | −0.002 (0.003) | [−0.008, 0.004] | −0.004 (0.005) | [−0.013, 0.004] |

| Partner total DWP episodes over 30 days | −0.002 (0.004) | [−0.010, 0.006] | −0.002 (0.003) | [−0.008, 0.005] |

| Actor total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.001 (0.003) | [−0.006, 0.005] | −0.003 (0.004) | [−0.011, 0.005] |

| Partner total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.002 (0.003) | [−0.008, 0.005] | 0.002 (0.004) | [−0.005, 0.009] |

| Actor total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] |

| Partner total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.002] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.001] |

| Actor mean positive affect over 30 days | 1.003 (0.010)*** | [0.983, 1.023] | 0.999 (0.016)*** | [0.967, 1.030] |

| Partner mean positive affect over 30 days | −0.004 (0.014) | [−0.030, 0.025] | 0.002 (0.012) | [−0.025, 0.023] |

| Variable | Male-reported negative affect | Female-reported negative affect | ||

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 0.839 (0.011)*** | [0.816, 0.859] | 0.950 (0.013)*** | [0.924, 0.974] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use with partner (DWP) | −0.170 (0.033)*** | [−0.234, −0.104] | −0.243 (0.037)*** | [−0.317, −0.173] |

| Partner alcohol use with partner (DWP) | −0.073 (0.034)* | [−0.139, −0.002] | −0.006 (0.039) | [−0.081, 0.072] |

| Actor alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | −0.047 (0.028) | [−0.104, 0.007] | −0.144 (0.039)*** | [−0.222, −0.072] |

| Partner alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | −0.121 (0.036)*** | [−0.195, −0.049] | 0.009 (0.035) | [−0.060, 0.079] |

| Actor number of standard drinks | −0.005 (0.007) | [−0.018, 0.008] | 0.020 0.009)* | [0.002, 0.039] |

| Partner number of standard drinks | 0.024 (0.009)** | [0.006, 0.040] | −0.008 0.008) | [−0.024, 0.006] |

| Actor prior report negative affect | 0.353 (0.010)*** | [0.333, 0.373] | 0.358 (0.009)*** | [0.339, 0.376] |

| Partner prior report negative affect | 0.045 (0.009)*** | [0.028, 0.062] | 0.048 (0.011)*** | [0.025, 0.070] |

| Day of the study1 | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] | 0.001 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total DWP episodes over 30 days | 0.003 (0.003) | [−0.003, 0.009] | 0.004 (0.003) | [0.000, 0.011] |

| Partner total DWP episodes over 30 days | 0.001 (0.003) | [−0.004, 0.007] | 0.000 (0.003) | [−0.004, 0.005] |

| Actor total DWOP episodes over 30 days | 0.000 (0.003) | [−0.005, 0.005] | 0.003 (0.003) | [−0.002, 0.009] |

| Partner total DWOP episodes over 30 days | 0.002 (0.002) | [−0.002, 0.007] | −0.001 (0.002) | [−0.005, 0.003] |

| Actor total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.000) | [−0.001, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.001] |

| Partner total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.000) | [−0.001, 0.001] |

| Actor mean negative affect over 30 days | 1.000 (0.009)*** | [0.984, 1.019] | 0.998 (0.009)*** | [0.980, 1.015] |

| Partner mean negative affect over 30 days | 0.002 (0.008) | [−0.014, 0.017] | 0.003 (0.011) | [−0.020, 0.021] |

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Day of the study (1–30)

DWP = drink with partner, DWOP = drink without partner

Does Drinking Predict Next-Day Relationship Functioning?

Next, we considered whether evening drinking events influence next-day relationship harmony and discord. Because the first report of the day was made, on average, at about 11:30 AM, most drinking events reported in the morning (2,732/3,213; 85.1%) took place the prior evening (5:00 PM to 1:00 AM; median 8:00 PM). Analyses used all drinking events reported at this EMA; however, the pattern of results was identical when we excluded the small proportion of drinking events that occurred at other times. Providing some support for Hypothesis 3, there were positive effects of DWP on next morning harmony (see Table 4). However, only the Actor DWP effect was significant for women and the Partner DWP effect for men, indicating that only women’s evening drinking increased harmony. In addition, there was a significant negative effect of Actor drinking quantity on women’s harmony and Partner drinking quantity on men’s harmony. That is, as women’s consumption increased, men’s and women’s harmony decreased. There were no significant effects of DWOP.

Table 4.

Morning Relationship Functioning as a Function of Prior Evening Drinking With and Without Partner

| Variable | Male-reported harmony | Female-reported harmony | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 4.793 (0.022)*** | [4.746, 4.832] | 4.809 (0.019)*** | [4.775, 4.850] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.100 (0.060) | [−0.020, 0.214] | 0.187 (0.053)*** | [0.085, 0.294] |

| Partner alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.178 (0.054)*** | [0.076, 0.289] | 0.091 (0.061) | [−0.029, 0.210] |

| Actor alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.041 (0.054) | [−0.070, 0.144] | 0.103 (0.060) | [−0.016, 0.223] |

| Partner alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.080 (0.062) | [−0.040, 0.200] | 0.028 (0.056) | [−0.084, 0.132] |

| Actor number of standard drinks | 0.002 (0.009) | [−0.016, 0.020] | −0.036 (0.011)*** | [−0.057, −0.015] |

| Partner number of standard drinks | −0.063 (0.011)*** | [−0.085, −0.042] | −0.010 (0.010) | [−0.029, 0.009] |

| Actor prior report relationship harmony | 0.280 (0.014)*** | [0.252, 0.309] | 0.326 (0.014)*** | [0.299, 0.354] |

| Partner prior report relationship harmony | 0.078 (0.014)*** | [0.051, 0.104] | 0.088 (0.015)*** | [0.058, 0.117] |

| Day of the study1 | −0.003 (0.001)* | [−0.006, 0.000] | −0.002 (0.002) | [−0.005, 0.001] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total DWP episodes over 30 days | −0.005 (0.006) | [−0.016, 0.008] | −0.006 (0.005) | [−0.016, 0.004] |

| Partner total DWP episodes over 30 days | −0.004 (0.005) | [−0.014, 0.006] | −0.004 (0.007) | [−0.016, 0.010] |

| Actor total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.002 (0.006) | [−0.012, 0.009] | −0.003 (0.007) | [−0.017, 0.009] |

| Partner total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.002 (0.007) | [−0.015, 0.012] | 0.000 (0.006) | [−0.011, 0.011] |

| Actor total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.002] |

| Partner total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.003, 0.002] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.001] |

| Actor mean morning relationship harmony over 30 days | 1.002 (0.014)*** | [0.974, 1.031] | 1.002 (0.015)*** | [0.975, 1.030] |

| Partner mean morning relationship harmony over 30 days | 0.003 (0.017) | [−0.031, 0.036] | 0.004 (0.014) | [−0.023, 0.032] |

| Variable | Male-reported discord | Female-reported discord | ||

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 0.619 (0.018)*** | [0.584, 0.653] | 0.608 (0.024)*** | [0.560, 0.653] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use with partner (DWP) | −0.009 (0.055) | [−0.116, 0.098] | 0.032 (0.058) | [−0.085, 0.139] |

| Partner alcohol use with partner (DWP) | −0.108 (0.050)* | [−0.203, −0.009] | −0.058 (0.062) | [−0.170, 0.077] |

| Actor alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | −0.001 (0.049) | [−0.096, 0.098] | −0.033 (0.065) | [−0.157, 0.094] |

| Partner alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | −0.123 (0.057)* | [−0.235, −0.010] | −0.056 (0.057) | [−0.162, 0.061] |

| Actor number of standard drinks | 0.009 (0.008) | [−0.007, 0.026] | 0.030 (0.011)** | [0.009, 0.052] |

| Partner number of standard drinks | 0.056 (0.010)*** | [0.036, 0.075] | 0.025 (0.010)* | [0.005, 0.043] |

| Actor prior report relationship discord | 0.186 (0.015)*** | [0.157, 0.216] | 0.223 (0.015)*** | [0.194, 0.252] |

| Partner prior report relationship discord | 0.091 (0.014)*** | [0.065, 0.118] | 0.082 (0.016)*** | [0.050, 0.113] |

| Day of the study1 | −0.008 (0.001)*** | [−0.011, −0.005] | −0.005 (0.002)** | [−0.008, −0.002] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total DWP episodes over 30 days | 0.001 (0.006) | [−0.011, 0.011] | −0.001 (0.007) | [−0.013, 0.013] |

| Partner total DWP episodes over 30 days | 0.004 (0.005) | [−0.005, 0.015] | 0.002 (0.006) | [−0.009, 0.015] |

| Actor total DWOP episodes over 30 days | 0.000 (0.005) | [−0.010, 0.009] | 0.002 (0.007) | [−0.012, 0.017] |

| Partner total DWOP over 30 days | 0.004 (0.006) | [−0.006, 0.016] | 0.002 (0.006) | [−0.009, 0.014] |

| Actor total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.002] |

| Partner total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] |

| Actor mean morning relationship discord over 30 days | 1.009 (0.026)*** | [0.962, 1.066] | 1.003 (0.032)*** | [0.937, 1.061] |

| Partner mean morning relationship discord over 30 days | 0.011 (0.025) | [−0.041, 0.058] | 0.000 (0.026) | [−0.051, 0.050] |

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Day of the study (1–30)

DWP = drink with partner, DWOP = drink without partner

Although we observed no significant effects of drinking on immediate ratings of discord (see Table 2), several effects, mostly involving women’s drinking emerged when we examined next-morning reports of discord. As shown in Table 4, there was a significant negative effect of Partner DWP on men’s discord, providing some support for Hypothesis 4, but, unexpectedly, a negative effect of Partner DWOP on men’s morning discord as well. There were also robust negative effects associated with consuming more drinks; women’s discord was higher when they or their partner consumed more drinks and men’s was higher when their partner consumed more drinks.

We repeated the next-day analyses using positive and negative affect, instead of relationship functioning, as the outcomes (see Table 5). Actor evening drinking events, both DWP and DWOP, predicted greater positive and lower negative affect the next morning. There were also some positive effects of women’s drinking events on men’s positive affect (partner DWP and DWOP effects). Thus, next-day effects of couple drinking on affect were broader than the more specific effects on couple functioning. Heavier consumption by women was associated with less positive and more negative affect for men and women, echoing the negative effects of women’s heavier drinking on relationship functioning.

Table 5.

Next Morning Positive and Negative Affect as a Function of Prior Evening Drinking With and Without Partner (morning reports)

| Variable | Male-reported positive affect | Female-reported positive affect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 3.533 (0.020)*** | [3.488, 3.572] | 3.405 (0.027)*** | [3.356, 3.457] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.318 (0.061)*** | [0.200, 0.442] | 0.256 (0.062)*** | [0.135, 0.375] |

| Partner alcohol use with partner (DWP) | 0.130 (0.054)* | [0.024, 0.236] | 0.074 (0.069) | [−0.059, 0.213] |

| Actor alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.253 (0.057)*** | [0.139, 0.364] | 0.176 (0.068)* | [0.044, 0.309] |

| Partner alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | 0.131 (0.064)* | [0.005, 0.253] | 0.052 (0.066) | [−0.072, 0.185] |

| Actor number of standard drinks | −0.068 (0.010)*** | [−0.087, −0.049] | −0.075 (0.012)*** | [−0.098, −0.053] |

| Partner number of standard drinks | −0.037 (0.011)*** | [−0.059, −0.015] | −0.012 (0.011) | [−0.034, 0.009] |

| Actor prior report positive affect | 0.160 (0.015)*** | [0.130, 0.190] | 0.190 (0.015)*** | [0.161, 0.218] |

| Partner prior report positive affect | −0.003 (0.013) | [−0.030, 0.023] | 0.030 (0.016) | [−0.002, 0.062] |

| Day of the study1 | −0.007 (0.002)*** | [−0.011, −0.004] | −0.004 (0.002)* | [−0.008, −0.001] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total DWP episodes over 30 days | −0.012 (0.006)* | [−0.022, −0.001] | −0.009 (0.007) | [−0.023, 0.005] |

| Partner total DWP episodes over 30 days | −0.003 (0.006) | [−0.016, 0.008] | −0.002 (0.007) | [−0.015, 0.013] |

| Actor total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.009 (0.005) | [−0.019, 0.003] | −0.006 (0.007) | [−0.021, 0.008] |

| Partner total DWOP episodes over 30 days | −0.005 (0.007) | [−0.019, 0.009] | −0.001 (0.006) | [−0.012, 0.010] |

| Actor total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.002] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.003] |

| Partner total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.002] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.001] |

| Actor mean of positive affect over 30 days | 1.008 (0.017)*** | [0.976, 1.038] | 0.995 (0.018)*** | [0.957, 1.030] |

| Partner mean of positive affect over 30 days | −0.010 (0.018) | [−0.046, 0.025] | 0.005 (0.016) | [−0.026, 0.032] |

| Variable | Male-reported negative affect | Female-reported negative affect | ||

| Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | Estimate (S.D.) | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 0.875 (0.018)*** | [0.832, 0.897] | 0.980 (0.023)*** | [0.935, 1.029] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use with partner (DWP) | −0.110 (0.047)* | [−0.197, −0.012] | −0.128 (0.050)** | [−0.227, −0.031] |

| Partner alcohol use with partner (DWP) | −0.064 (0.043) | [−0.144, 0.024] | −0.079 (0.058) | [−0.194, 0.033] |

| Actor alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | −0.111 (0.044)* | [−0.192, −0.021] | −0.013 (0.058) | [−0.123, 0.101] |

| Partner alcohol use without partner (DWOP) | −0.067 (0.051) | [−0.164, 0.036] | −0.081 (0.054) | [−0.183, 0.030] |

| Actor number of standard drinks | 0.015 (0.007)* | [0.000, 0.029] | 0.012 (0.010) | [−0.007, 0.031] |

| Partner number of standard drinks | 0.008 (0.009) | [−0.009, 0.025] | 0.006 (0.009) | [−0.012, 0.024] |

| Actor prior report negative affect | 0.243 (0.014)*** | [0.216, 0.271] | 0.279 (0.015)*** | [0.251, 0.308] |

| Partner prior report negative affect | 0.002 (0.013) | [−0.022, 0.027] | 0.042 (0.016)** | [0.011, 0.072] |

| Day of the study1 | 0.003 (0.001)* | [0.001, 0.005] | −0.002 (0.001) | [−0.004, 0.001] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total DWP episodes over 30 days | 0.005 (0.004) | [−0.004, 0.011] | 0.004 (0.005) | [−0.005, 0.015] |

| Partner total DWP episodes over 30 days | 0.001 (0.005) | [−0.007, 0.011] | 0.003 (0.006) | [−0.007, 0.014] |

| Actor total DWOP episodes over 30 days | 0.004 (0.004) | [−0.007, 0.011] | 0.000 (0.007) | [−0.014, 0.012] |

| Partner total DWOP over 30 days | 0.001 (0.005) | [−0.008, 0.013] | 0.003 (0.005) | [−0.007, 0.012] |

| Actor total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.002] |

| Partner total number of standard drinks over 30 days | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.002, 0.002] | 0.000 (0.001) | [−0.001, 0.001] |

| Actor mean of negative affect over 30 days | 1.001 (0.015)*** | [0.977, 1.031] | 1.001 (0.016)*** | [0.968, 1.029] |

| Partner mean of negative affect over 30 days | −0.002 (0.013) | [−0.024, 0.032] | −0.005 (0.017) | [−0.042, 0.028] |

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Day of the study (1–30)

DWP = drink with partner, DWOP = drink without partner

Discussion

The present EMA study provided a more detailed examination of the effects of couple drinking on short-term relationship functioning than has previously been possible. We found support for the hypothesis that DWP, compared with no drinking, increases self-reported relationship harmony for men and women. These effects were apparent within a few hours of drinking (Hypothesis 1) as well as the morning after evening DWP events (Hypothesis 3). Increases in self-reported closeness and getting along with partner are consistent with the immediate positive effects of DWP on intimacy events found in prior research (Testa et al., 2019a) and with next-day positive effects on intimacy (Levitt & Cooper, 2010). The short-term positive effects underscore how drinking with partner may be reinforcing for couples with concordant drinking patterns, providing an immediate boost to relationship functioning and contributing to positive expectancies about alcohol and intimacy and to subsequent drinking (e.g., Levitt & Leonard, 2013).

Whereas immediate and next morning effects of drinking events on harmony were similar, we observed different patterns for immediate and next-day effects of drinking events on discord. We failed to support Hypothesis 2; there were no immediate effects of DWP (or DWOP) on relationship discord. Thus, despite the high correlation between harmony and discord within report (r = −0.57), they are not simply reciprocals of each other. In contrast, there were some significant effects of evening drinking on morning discord. Men reported less morning discord following women’s prior evening DWP, providing some support for Hypothesis 4, but also after women’s DWOP. This unexpected effect is not easily explained and requires replication. There were no corresponding effects of DWP or DWOP on women’s morning discord. However, there were robust positive effects on men’s and women’s morning discord associated with heavier prior evening consumption by the female partner, consistent with Levitt and Cooper (2010).

The failure to observe any immediate increase in relationship discord following drinking seems inconsistent with evidence that drinking by either partner increases the likelihood of an episode of partner conflict and aggression later that day (de Bruijn & de Graaf, 2016) or even within the next few hours (Testa & Derrick, 2014). The apparent inconsistency may reflect differences in outcome. The present study considered subtle changes in mean levels of discord, controlling for the strong effects of discord reported a few hours earlier. Mean ratings of anger and arguing were very low across the 30 days of reports (0.54 on a 0–6 scale; SD = 1.07), indicating that an absence of discord is normative and potentially making it difficult to detect effects. However, it is possible that episodes of IPA, a relatively rare event, are more likely to occur after drinking, particularly under certain circumstances or for certain people. On the other hand, the delayed effect of heavier evening consumption by women on increased morning discord for men and women suggests a mechanism other than alcohol-impaired inhibition contributing to conflict, for example, hangover symptoms leading to morning irritability or perhaps conflict over the partner’s evening drinking. More research is needed to separate and understand immediate versus next-day effects of couple drinking.

In next-day analyses, women’s drinking appeared to be more influential than men’s for relationship functioning. That is, there were Actor and Partner effects of women’s drinking on men’s and women’s harmony. The greater importance of women’s drinking for relationship functioning has been shown in previous daily (Levitt & Cooper 2010) and survey studies (Homish & Leonard, 2005). Moreover, there is some evidence that women may drink with their partners to facilitate intimacy (Levitt & Cooper, 2010), and that women who drink concordantly with their heavy drinking partners maintain stronger alcohol-intimacy expectancies than do other women (Derrick et al., 2010). Women are traditionally thought to bear a greater burden for relationship maintenance (Umberson et al., 2015) and these studies suggest that women’s DWP may be in service of that goal. Conversely, we observed negative effects associated with heavier drinking by women that were not apparent to the same degree with male consumption. The greater adverse effects of women’s drinking have been documented in previous research (Torvik et al., 2013) and are consistent with the perspective that women’s heavy drinking is more problematic because it is viewed by men as violating female gender roles (Leonard et al., 2014; Levitt & Cooper, 2010).

Although not the focus of the study, we were able to consider whether effects of drinking on positive and negative affect mirrored effects on couple harmony and discord. Some effects were comparable, for example, heavier consumption had negative consequences for affect and for relationship functioning. Also, men and women reported increased positive affect and relationship harmony immediately after DWP but not after DWOP, suggesting that DWP is particularly rewarding. However, both DWP and DWOP reduced immediate negative affect (see Table 3) whereas neither reduced immediate relationship discord. Likewise, both DWP and DWOP improved next-day positive affect whereas next-day harmony effects were specific to women’s DWP. Findings suggest that the two outcomes are distinct and relationship functioning is not simply a reflection of alcohol’s influence on positive and negative affect. Relationship consequences of drinking events tended to be more specific than the broader effects on affect. A caution in interpreting these results that morning affect is reported an average of 16 hours after drinking, and hence may not be a direct reflection of alcohol’s influence on affect.

Strengths and Limitations

The present analyses took into consideration several important covariates, allowing us to better isolate the “pure” effects of drinking events on momentary self-reported relationship harmony and discord. First, we accounted for the robust effects of relationship functioning at the prior report, so that increases or decreases are interpreted as changes from the most recent, pre-drinking levels. Moreover, we controlled for between-person differences in relationship functioning and for number of DWP and DWOP events so that findings represent within-person changes following specific drinking events and not the effects of drinking together more frequently or overall functioning. Importantly, we also accounted for the number of drinks within the same analyses, allowing us to distinguish the positive effects of DWP from the negative effects of heavier drinking. Whereas previous studies have defined DWP as drinking while partner was present (Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Levitt et al., 2014), we limited DWP events to those in which partner was present and also drinking, to better reflect the shared activity thought to underlie the positive effects of drinking together (Homish & Leonard, 2005).

Despite the rigorous methods, results should be considered in light of some limitations. In order to consider the temporal effects of drinking events on daily relationship functioning, we deliberately selected a sample in which both partners drank regularly and hence were likely to report multiple episodes of drinking over 30 days. As a result, the sample consists of couples with congruent drinking patterns, and presumably, greater relationship satisfaction and functioning compared with couples with discrepant drinking patterns (Homish & Leonard, 2007). We did not find any Level 2 effects of DWP or DWOP; couples who reported more episodes of DWP or DWOP did not report better (or worse) relationship outcomes than those with fewer episodes. However, the range was truncated by our selection criteria. Generalizability is limited by the deliberately narrow eligibility criteria (congruent heavy drinking couples with a history of partner aggression) as well as by the fact that the sample was heterosexual, primarily White, limited to one geographic location, and recruited via Facebook.

Assessing drinking and relationship functioning three times daily was an advance from earlier studies that used once-daily reports, allowing us to consider immediate effects separate from the next-day effects of drinking. However, to ensure good compliance, we kept the random reports quite short, with limited indicators of each construct. Relationship functioning varied little from one EMA to the next; harmony was generally high and discord very low. Thus, effects are based on small changes in these measures. Although EMA reports are thought to increase accuracy and reduce memory error, it is unknown to what degree omissions or errors in reporting influenced findings. For example, correspondence in partner reports of drinking or other events is typically low in dyadic studies (e.g., Testa & Derrick, 2014), making it unfeasible to try to match partner reports of drinking. However, this limitation is mitigated by our use of the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM). APIM permits consideration of the effects of each partner’s independent report on the other’s outcome while accounting for the relationship between them, and Partner effects were observed.

Conclusions

Couple drinking events have measurable effects on self-reported relationship functioning within the next few hours and the next morning. Findings provided additional evidence for the positive effects of DWP and for the deleterious effects of women’s heavier drinking for relationship functioning within a community sample (Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Levitt et al., 2014; Testa et al., 2019a). Research on the short-term effects of couple drinking events is in its infancy and additional studies are needed to better understand the complex ways in which alcohol influences relationship functioning and vice versa (Rodriguez & Derrick, 2017; Rodriguez et al., 2014). For example, drinking events may function differently among couples with discrepant drinking patterns or who are maritally distressed. There may also be developmental differences as well, for example, between dating and married or cohabiting couples. It will also be important to consider how momentary couple functioning influences subsequent drinking (e.g., Derrick & Testa, 2017) and potential reciprocal or cyclical effects.

Public Health Significance:

Within cohabiting heterosexual couples, episodes of drinking alcohol together resulted in increases in perceived relationship harmony, suggesting that drinking may be reinforcing. However, heavier consumption, particularly by female partners, led to increased relationship discord the next day.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by R01AA022946 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

The authors have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- aan het Rot M, Russell JJ, Moskowitz DS, & Young SN (2008). Alcohol in a social context: Findings from event-contingent recording studies of everyday social interctions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(3), 459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Polenick CA, & Antonucci TC (2019). Drinking together: Implications of drinking partners for negative marital quality. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(2), 167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Goldman MS, Inn A, & Anderson LR (1980). Expectations of reinforcement from alcohol: Their domain and relation to drinking patterns. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48(4), 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, & Wolf S (2016). Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. In Sher KJ (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of substance use and substance use disorders., Vol. 1. (pp. 375–421). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Godleski SA, Przybyla SM, Schlauch RC, & Testa M (2016). The proximal effects of acute alcohol consumption on male-to-female aggression: A meta-analytic review of the experimental literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(5), 520–531. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Licata ML, Schlauch RC, Testa M, & Easton CJ (2017). The proximal effects of acute alcohol use on female aggression: A meta-analytic review of the experimental literature. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(1), 21–26. doi: 10.1037/adb0000244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Testa M, Derrick JL, & Leonard KE (2014). Daily associations among self-control, heavy episodic drinking, and relationship functioning: An examination of actor and partner effects. Aggressive Behavior, 40(5), 440–450. doi: 10.1002/ab.21533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Zimmerman L, Rhew IC, Cadigan JM, Atkins DC, & Lee CM (2020). Does it work and does it last? Effects of social and drinking behavior on same- and next-day mood. Addictive Behaviors, 100. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn DM, & de Graaf IM (2016). The role of substance use in same-day intimate partner violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 27, 142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2016.02.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick JL, Leonard KE, Quigley BM, Houston RJ, Testa M, & Kubiak A (2010). Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies in couples with concordant and discrepant drinking patterns. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71, 761–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick JL, & Testa M (2017). Temporal effects of perpetrating or receiving intimate partner aggression on alcohol consumption: A daily diary study of community couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78, 213–221. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulstone AR, Kelly AB, Kifle T, & Baxter J (2016). Heavy alcohol use in the couple context: A nationally representative longitudinal study. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(11), 1441–1450. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1178295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Josephs RA, Dewall CN, & Gunn RL (2009). Applying the attention-allocation model to the explanation of alcohol-related aggression: Implications for prevention. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(9–10), 1263–1279. doi: 10.1080/10826080902960049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman JM, Ramchandani VA, Davis MB, Bjork JM, & Hommer DW (2008). Why we like to drink: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of the rewarding and anxiolytic effects of alcohol. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28(18), 4583–4591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0086-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girme YU, Overall NC, & Faingataa S (2014). ‘Date nights’ take two: The maintenance function of shared relationship activities. Personal Relationships, 21(1), 125–149. doi: 10.1111/pere.12020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga GC, Campos B, & Bradbury TN (2007). Similarity, convergence, and relationship satisfaction in dating and married couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 34–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, & Leonard KE (2005). Marital quality and congruent drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66(4), 488–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, & Leonard KE (2007). The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(1), 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Kozlowski LT, & Cornelius JR (2009). The longitudinal association between multiple substance use discrepancies and marital satisfaction. Addiction, 104(7), 1201–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, & Donnellan MB (2012). Conceptual and methodological issues in the analysis of data from dyads and groups. In Deaux K & Snyder M (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of personality and social psychology (pp. 209–238): Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, & Quigley BM (2017). Thirty years of research show alcohol to be a cause of intimate partner violence: Future research needs to identify who to treat and how to treat them. Drug and Alcohol Review, 36, 7–9. doi: 10.1111/dar.12434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Smith PH, & Homish GG (2014). Concordant and discordant alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use as predictors of marital dissolution. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(3), 780–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, & Cooper ML (2010). Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(12), 1706–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Derrick JL, & Testa M (2014). Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and gender moderate the effects of relationship-drinking contexts on daily relationship functioning. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(2), 269–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, & Leonard KE (2013). Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and relationship-drinking contexts: Reciprocal influence and gender-specific effects over the first 9 years of marriage. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 986–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP (2003). For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(7), 959–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiklejohn J, Connor JL, & Kypri K (2012). Drinking concordance and relationship satisfaction in New Zealand couples. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 47(5), 606–611. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Elkins SR, McNulty JK, Kivisto AJ, & Handsel VA (2011). Alcohol use and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: Assessing the temporal association using electronic diary technology. Psychology of Violence, 1(4), 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK, & Asparouhov T (2016). Regression and mediation analysis using Mplus. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Reingle JM, Jennings WG, Connell NM, Businelle MS, & Chartier KG (2014). On the pervasiveness of event-specific alcohol use, general substance use, and mental health problems as risk factors for intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(16), 2951–2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, & Derrick JL (2017). Breakthroughs in understanding addiction and close relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C, & Knee CR (2014). Problematic alcohol use and marital distress: An interdependence theory perspective. Addiction Research & Theory, 22(4), 294–312. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2013.841890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Stuart GL, Temple JR, & Heeren T (2018). Alcohol, marijuana, and dating abuse perpetration by young adults: Results of a daily call study. Violence Against Women, 24, 1187–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Creswell KG, Dimoff JD, Fairbairn CE, Cohn JF, Heckman BW, Kirchner TR, Levine JM, & Moreland RL (2012). Alcohol and group formation: A multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding. Psychological Science, 23(8), 869–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Stuart GL, McNulty JK, & Moore TM (2014). Acute alcohol use temporally increases the odds of male perpetrated dating violence: A 90-day diary analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 365–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, Gulati NK, & Fromme K (2016). Daily associations between alcohol consumption and dating violence perpetration among men and women: Effects of self-regulation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77(1), 150–159. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, & Southwick L (1985). Alcohol and social behavior I: The psychology of drunken excess. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 18–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani OS, Parrott DJ, & Eckhardt CI (2017). Problematic drinking mediates the association between urgency and intimate partner aggression during acute intoxication. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental, 41(9), 1602–1611. doi: 10.1111/acer.13437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Derrick JL (2014). A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(1), 127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Wang W, Derrick JL, & Leonard KE (2019a). Does drinking together promote relationship intimacy? Temporal effects of daily drinking events in intimate couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(5), 537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Wang W, Derrick JL, & Leonard KE (2019b). Marijuana use episodes and partner intimacy experiences: A daily report study. Cannabis 2(1): 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik FA, Røysamb E, Gustavson K, Idstad M, & Tambs K (2013). Discordant and concordant alcohol use in spouses as predictors of marital dissolution in the general population: Results from the HUNT study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(5), 877–884. doi: 10.1111/acer.12029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar HR, Piasecki TM, McCarthy DM, Sher KJ, & Heath AC (2015). Ecological evidence that affect and perceptions of drink effects depend on alcohol expectancies. Addiction, 110(9), 1432–1442. doi: 10.1111/add.12982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Wycoff AM, Lane SP, Carpenter RW, & Brown WC (2016). Cannabis and alcohol use, affect and impulsivity in psychiatric out‐ patients’ daily lives. Addiction, 111(11), 2052–2059. doi: 10.1111/add.13471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Thomeer MB, & Lodge AC (2015). Intimacy and emotion work in lesbian, gay, and heterosexual relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 77, 542–556. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Schoot R, Kaplan D, Denissen J, Asendorpf JB, Neyer FJ, & van Aken MAG (2014). A gentle introduction to Bayesian analysis: Applications to developmental research. Child Development, 85, 842–860. 10.1111/cdev.12169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham RE, & Knee CR (2013). Examining temporal processes in diary studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(9), 1184–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]