Abstract

Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has emerged as an important cause of infection. We conducted a longitudinal study to evaluate changes in clinical and microbiological characteristics as well as outcomes of sequence type (ST) 72 MRSA bacteremia. We reviewed adult patients enrolled in a prospective cohort with ST72 MRSA bacteremia from August 2008 to December 2018 at Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea. Changes in clinical characteristics, outcomes, and microbiological characteristics of patients over time were evaluated. Generalized linear and linear regression models were used to evaluate changes. Of the 1,760 isolates, 915 (62%) were MRSA bacteremia and 292 (31.9%) were ST72 MRSA. During the study period, the relative risk (RR) of MRSA bacteremia decreased annually by 3.7%; however, among MRSA bacteremia, RR of ST72 MRSA increased annually by 8.5%. Vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) decreased over the study period. Metastatic infection, persistent bacteremia, and recurrence of bacteremia within 12 weeks decreased significantly. There were no significant changes in 30-d and 12-week mortality. Antibiotic susceptibility of ST72 MRSA was evaluated, and the resistance rate to erythromycin decreased significantly. ST72 MRSA incidence increased annually; its vancomycin MIC and erythromycin resistance rate decreased over the 11 years.

Subject terms: Medical research, Pathogenesis

Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a leading cause of community- and healthcare-associated infections. Hospital-acquired (HA) MRSA and community-acquired (CA) MRSA clones are genetically distinct and their distribution varies in different regions1. However, in recent years, CA-MRSA has spread and emerged as an important cause of healthcare-associated infection2,3. USA300-sequence type (ST)8, a highly prominent Panton-Valentine leucocidin (PVL)-positive CA-MRSA, is the dominant CA-MRSA in North America and is progressively increasing in nosocomial settings4,5.

In Korea, PVL-negative ST72-SCCmec type IV MRSA is a major CA-MRSA strain6,7. The ST72 MRSA strain has also become an important pathogen in hospitals as well as in the community8–10. There have been several studies regarding the prevalence and characteristics of ST72 MRSA, but no previous study has analyzed longitudinal changes in ST72 MRSA. We hypothesized that there were changes in the properties of ST72 MRSA and analyzed changes in the clinical characteristics of patients with ST72 MRSA bacteremia as well as changes in microbiological characteristics and the genotype of ST72 MRSA isolates in our institution over 11 years.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

This prospective study with a cohort of patients with S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) was conducted at the Asan Medical Center, a 2,700-bed tertiary referral center in Seoul, South Korea. From July 2008 to December 2018, all adult patients with SAB were prospectively enrolled in a cohort and observed over a 12-week period. Patients were excluded if they (1) had polymicrobial bacteremia or (2) were discharged before positive blood culture results were available. Of the patients with MRSA bacteremia, only those with ST72 MRSA isolates were included in the study. This study consisted of two sets of analysis; a longitudinal analysis to evaluate changes in the clinical characteristics and outcomes of ST72 MRSA bacteremia, and a comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes in the first 3 years (2008–2010) and final 3 years (2016–2018). We also evaluated subgroup analysis in patients with community-onset and HA infection. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the research. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the Asan Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Data collection and study definitions

The following data were recorded: age, gender, demographic characteristics, underlying diseases, severity of underlying disease or condition, bacteremia severity, location of acquisition, initial source of SAB, susceptibility to antibiotics, and clinical outcomes. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and Pitt bacteremia scores were used to evaluate the severity of bacteremia, and the Charlson comorbidity index were used to evaluate the severity of comorbid conditions11–13.

Location of acquisition was categorized as CA, healthcare-associated, or HA infection14. Catheter-related infection and infective endocarditis were defined in accordance with widely accepted criteria15,16. Prosthetic devices included orthopedic devices, prosthetic valves, cardiovascular electronic devices, and vascular grafts. Septic shock was defined according to the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock sepsis17. Persistent bacteremia was defined as bacteremia for ≥ 3 d while receiving appropriate antibiotic therapy. Recurrent bacteremia was defined as the occurrence of SAB within 12 weeks following clinical resolution; 30-day mortality and 12-week mortality mean all-cause deaths within 30 days and 12 weeks after bacteremia, respectively. Infection-attributable mortality was death due to ST72 MRSA infection in a previously healthy individual or when ST72 MRSA infection hastened death in the presence of an underlying medical condition.

Microbiology analysis

The first bloodstream isolates from each patient were used for microbiological and molecular assessments. All isolates were confirmed as MRSA by polymerase chain reaction detection of the mecA gene, and multi-locus sequence typing was performed as described elsewhere18. The vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined using a broth microdilution method based on the manufacturer's protocol. Antimicrobial susceptibilities were tested by standard techniques according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

The staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type, agr functionality, and spa sequence typing were identified using previously described methods19,20. The agr disfunction was determined by analyzing δ-hemolysin activity as described previously21. The assignment of spa type was performed using BIONUMERICS (APPLIED MATHS).

Statistical analysis

All variables for each year's clinical characteristics, agr functionality, SCCmec type, and spa type were summarized, and annual changes were analyzed using a generalized linear model. Continuous variables were analyzed using a linear regression model. We compared patients in the first 3 years (2008–2010) and in the final 3 years (2016–2018). Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using Student's t test and the Mann–Whitney U-test. A two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the hospital ethics committee.

Results

Annual change in clinical characteristics and outcomes of ST72 MRSA

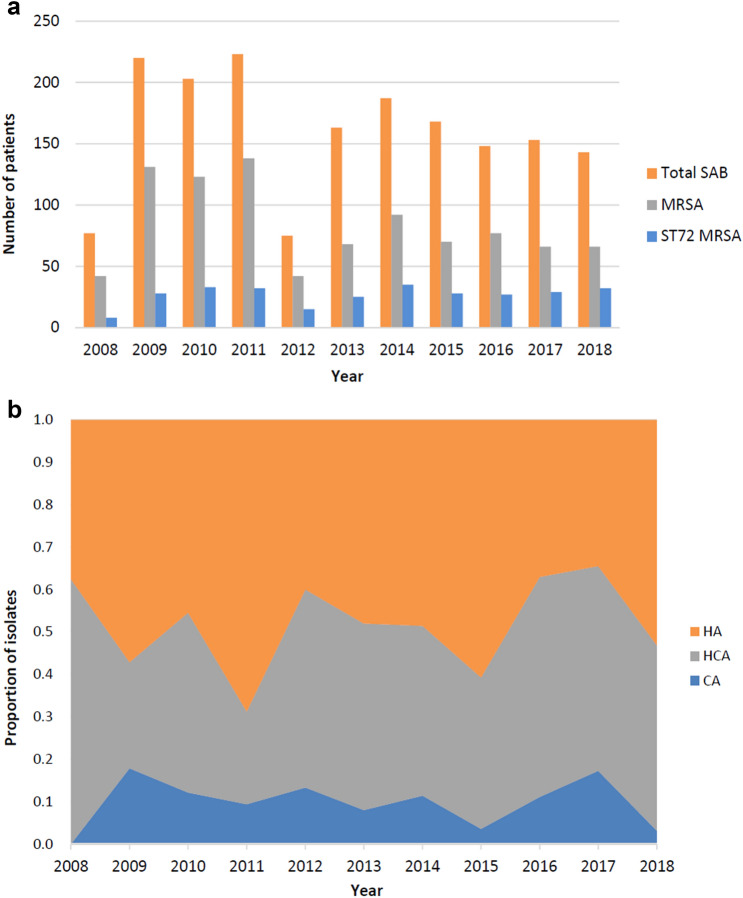

From July 2008 to December 2018, there were 1,760 episodes of SAB, and 915 (62%) were MRSA bacteremia. Among the 915 MRSA isolates, 292 (31.9%) were ST72 MRSA. During the study period, the relative risk (RR) of MRSA bacteremia decreased annually by 3.7% (p < 0.01) and among MRSA bacteremia, the RR of ST72 MRSA increased annually by 8.5% (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1a). Locations of acquisition of ST72 MRSA over an 11-year period are shown in Fig. 1b. The clinical and microbiological characteristics of ST72 MRSA are shown in Table 1. HA bacteremia was found in 49.7% (145/292) of cases and CA bacteremia in 10.3% (30/292) of cases. Most common comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (37.0% [108/292]), solid tumor (36.6% [107/292]), liver cirrhosis (14.4% [42/292]), and end state renal disease (14.0% [41/292]). The site of acquisition of MRSA bacteremia and underlying diseases did not show significant change during the study period.

Figure 1.

(a) Annual distribution of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB), MRSA, and ST72 MRSA in Asan Medical Center over an 11-year period. (b) Locations of acquisition of ST72 MRSA over an 11-year period. MRSA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; ST sequence type; HA Hospital-acquired; HCA healthcare-associated; CA community-acquired.

Table 1.

Annual changes in clinical and microbiological characteristics of 292 patients with sequence type 72 MRSA bacteremia.

| Characteristic | Number of patients (%) | Annual change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Age (year), median (IQR) | 64 (53–72) | NA | NA |

| Male | 175 (59.9) | NA | NA |

| Place of acquisition | |||

| Community-onset | 147 (50.3) | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) | 0.47 |

| Community-acquired | 30 (10.3) | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 0.47 |

| Healthcare-associated | 117 (40.1) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 0.24 |

| Hospital-acquired | 145 (49.7) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.47 |

| Underlying disease | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 108 (37.0) | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 0.94 |

| Solid tumor | 107 (36.6) | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.76 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 42 (14.4) | 1.08 (0.98–1.20) | 0.14 |

| End state renal disease | 41 (14.0) | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 0.86 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (2–4.8) | 0.05* | 0.30 |

| APACHE II, median (IQR) | 16 (11–20) | − 0.03* | 0.83 |

| Pitt bacteremia score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | − 0.01* | 0.82 |

| Septic shock | 33 (11.3) | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | 0.45 |

| Central venous catheter | 88 (30.1) | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 0.93 |

| Prosthetic devicea | 58 (19.9) | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 0.75 |

| Characteristics of infection | |||

| CVC-related infection | 58 (19.9) | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) | 0.16 |

| Primary bacteremia | 42 (14.4) | 0.98 (0.89–1.09) | 0.72 |

| Bone and joint infection | 33 (11.3) | 0.96 (0.86–1.08) | 0.48 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 26 (8.9) | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 0.26 |

| Pneumonia | 24 (8.2) | 1.17 (1.02–1.35) | 0.03 |

| Infective endocarditis | 14 (4.8) | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 0.91 |

| Metastatic infection | 57 (19.5) | 0.89 (0.82–0.97) | 0.01 |

| Persistent bacteremia (≥ 3 d) | 116 (39.7) | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) | 0.045 |

| Recurrent bacteremia within 12 weeks | 13 (4.5) | 0.70 (0.56–0.89) | < 0.01 |

| 30-d mortality | 34 (11.6) | 1.08 (0.97–1.21) | 0.17 |

| 12-week mortality | 65 (22.3) | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 0.60 |

| Infection-attributable mortality | 38 (13.0) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) | 0.17 |

| In-hospital crude mortality | 39 (13.4) | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 0.34 |

| Vancomycin MIC (BMD), mean ± SD (mg/L) | 1.08 ± 0.20 | − 0.01*b | 0.01 |

| agr dysfunction | 31 (10.6) | 1.02 (0.90–1.14) | 0.79 |

| SCCmec type | |||

| SCCmec IV | 291 (99.7) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.96 |

| SCCmec IVa | 251/291 (86.3) | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.64 |

| spa type | |||

| t324 | 139 (47.6) | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.19 |

| t664 | 42 (14.4) | 0.96 (0.87–1.06) | 0.39 |

| t148 | 33 (11.3) | 0.98 (0.88–1.10) | 0.72 |

| Others | 49 (16.8) | NA | NA |

| Antibiotic resistance | |||

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanate | 271 (92.8) | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 0.85 |

| Clindamycin | 58 (19.9) | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) | 0.68 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 23 (7.9) | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 0.05 |

| Erythromycin | 75 (25.7) | 0.89 (0.82–0.96) | < 0.01 |

| Fusidic acid | 3 (1.0) | 1.11 (0.75–1.63) | 0.60 |

| Gentamicin | 39 (13.4) | 0.95 (0.86–1.06) | 0.35 |

| Rifampin | 5 (1.7) | 1.12 (0.83–1.51) | 0.47 |

| Quinupristin/Dalfopristin | 0 | NA | NA |

| TMP/SMX | 2 (0.7) | 0.85 (0.53–1.39) | 0.52 |

| Tetracycline | 8 (2.7) | 1.07 (0.85–1.35) | 0.58 |

IQR interquartile range; APACHE II acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II; CVC central venous catheter; MIC minimum inhibitory concentration; BMD broth microdilution method; SCC staphylococcal cassette chromosome; TMP/SMX trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

*A linear regression model was used for analysis.

aProsthetic device included orthopedic devices (14 patients), cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (4 patients), prosthetic valves (11 patients), and vascular grafts (30 patients) in patients with persistent bacteremia.

bResult of linear regression: R2 = 0.025, vancomycin MIC = 22.07 + (− 0.01) × year.

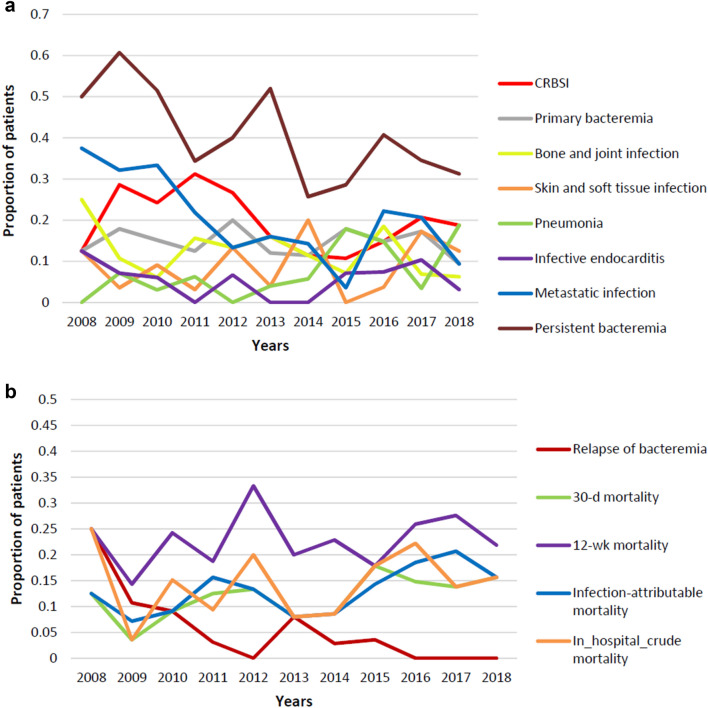

There were no significant changes in Charlson comorbidity index, APACHE II score, or Pitt bacteremia score. Characteristics of infection were identified as central venous catheter (CVC)-related infection (19.9% [58/292]), primary bacteremia (14.4% [42/292]), bone and joint infection (11.3% [33/292]), skin and soft tissue infection (8.9% [26/292]), pneumonia (8.2% [24/292]), and infective endocarditis (4.8% [14/292]). The RR of pneumonia increased annually by 15.9% (p = 0.03) (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Clinical characteristics of ST72 MRSA bacteremia over the study period. (b) Clinical outcomes of ST72 MRSA bacteremia over the study period. CRBSI, catheter-related blood stream infection.

Metastatic infection was found in 19.5% (57/292) of cases and persistent bacteremia in 39.7% (116/292) of cases. Metastatic infection (RR 0.89; p = 0.01) and persistent bacteremia (RR 0.94; p = 0.045) showed significant annual decrease (Fig. 2a). During the study period, 34 (11.6%) patients died within 30 d after the index day and 258 (88.4%) patients survived. There were no significant changes in 30-d and 12-week mortality. Recurrent ST72 MRSA bacteremia occurred in 13 (4.5%) cases and decreased over the study period (RR 0.7; p < 0.01) (Fig. 2b).

Annual changes in microbiological characteristics and antibiotic susceptibility of ST72 MRSA

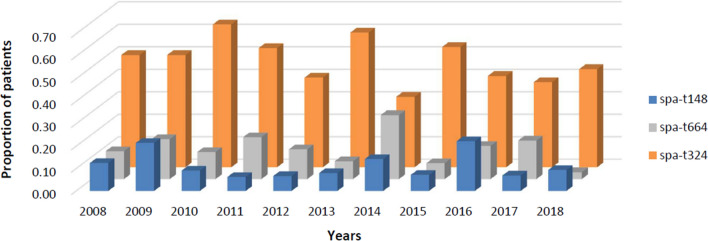

The mean vancomycin MIC was 1.08 mg/L, and this decreased annually by 0.01 (R2 = 0.025; p = 0.01). agr dysfunction was 10.6% (31/292). SCCmecIV was 99.7% (291/292), and most SCCmecIV was SCCmecIVa (86.3%, [251/291]). Common spa types were t324 (47.6% [139/292]), t664 (14.4% [42/292]), and t148 (11.3% [33/292]) (Fig. 3). The proportions of agr dysfunction, SCCmec type, and spa type did not differ over the study period. Antibiotic susceptibility tests were conducted on 10 antibiotics. There was no change in the resistance rate to most antibiotics, but that to erythromycin decreased significantly during the study period (RR 0.89; p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

The spa type over the study period.

Comparison of ST72 MRSA between the first 3 years and final 3 years of study

In the first 3 years (2008–2010), 296 patients had MRSA bacteremia and 69 (23.3%) of these cases were ST72 MRSA. In the final 3 years (2016–2018), 209 patients had MRSA bacteremia and 88 (42.1%) of these cases were ST72 MRSA. The proportions of ST72 MRSA bacteremia was significantly higher in patients in the final 3 years of study than in those in the first 3 years of study (p < 0.01). Comparisons of the two groups are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in the location of acquisition, underlying disease, and characteristics of infection between the two groups. The patients in the first 3 years were more likely to have metastatic infection (33.3% [23/69] vs. 17.0% [15/88], p = 0.02) and persistent bacteremia (55.1% [38/69] vs. 35.2% [31/88], p = 0.01) than patients in the final 3 years. Recurrent bacteremia occurred more frequently in patients in the first 3 years (11.6% [8/69] vs. 0% [0/88], p < 0.01). There was no difference in 30-d and 12-week mortality between the two groups.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of clinical and microbiological characteristics of 157 patients with sequence type 72 MRSA bacteremia.

| Characteristic | 2008–2010 (n = 69) No. (%) | 2016–2018 (n = 88) No. (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), median (IQR) | 64 (55–72.5) | 64.5 (52.3–74) | 0.89 |

| Male | 36 (52.2) | 56 (63.6) | 0.15 |

| Place of acquisition | |||

| Community-onset | 35 (50.7) | 51 (58.0) | 0.42 |

| Community-acquired | 9 (13.0) | 9 (10.2) | 0.58 |

| Healthcare-associated | 26 (37.7) | 42 (47.7) | 0.21 |

| Hospital-acquired | 34 (49.3) | 37 (42.0) | 0.37 |

| Underlying disease | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 (43.5) | 40 (45.5) | 0.81 |

| Solid tumor | 25 (36.2) | 31 (35.2) | 0.90 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 8 (11.6) | 15 (17.0) | 0.34 |

| End state renal disease | 10 (14.5) | 12 (13.6) | 0.88 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 2.5 (1–5) | 0.59 |

| APACHE II, median (IQR) | 16 (10.5–20) | 16 (11–19.8) | 0.88 |

| Pitt bacteremia score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.69 |

| Septic shock | 9 (13.0) | 9 (10.2) | 0.58 |

| Central venous catheter | 21 (30.4) | 28 (31.8) | 0.85 |

| Prosthetic device | 10 (14.5) | 14 (15.9) | 0.81 |

| Characteristics of infection | |||

| CVC-related infection | 17 (24.6) | 16 (18.2) | 0.32 |

| Primary bacteremia | 11 (15.9) | 12 (13.6) | 0.69 |

| Bone and joint infection | 7 (10.1) | 9 (10.2) | 0.99 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 5 (7.2) | 10 (11.4) | 0.38 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (4.3) | 11 (12.5) | 0.08 |

| Infective endocarditis | 5 (7.2) | 6 (6.8) | > 0.99 |

| Metastatic infection | 23 (33.3) | 15 (17.0) | 0.02 |

| Persistent bacteremia (≥ 3 d) | 38 (55.1) | 31 (35.2) | 0.01 |

| Recurrent bacteremia within 12 weeks | 8 (11.6) | 0 | < 0.01 |

| 30-d mortality | 5 (7.2) | 13 (14.8) | 0.14 |

| 12-week mortality | 14 (20.3) | 22 (25.0) | 0.49 |

| Infection-attributable mortality | 6 (8.7) | 16 (18.2) | 0.09 |

| In-hospital crude mortality | 8 (11.6) | 15 (17.0) | 0.34 |

| Vancomycin MIC (BMD), mean ± SD (mg/L) | 1.11 ± 0.21 | 1.03 ± 0.17 | < 0.01 |

| agr dysfunction | 6 (8.7) | 8 (9.1) | 0.93 |

| spa type | |||

| t324 | 39 (56.5) | 36 (40.9) | 0.05 |

| t664 | 10 (14.5) | 10 (11.4) | 0.56 |

| t148 | 10 (14.5) | 11 (12.5) | 0.72 |

| Others | 7 (10.1) | 16 (18.2) | NA |

| Antibiotic resistance | |||

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanate | 67 (97.1) | 81 (92.0) | 0.30 |

| Clindamycin | 12 (17.4) | 14 (15.9) | 0.80 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4 (5.8) | 10 (11.4) | 0.22 |

| Erythromycin | 29 (42.0) | 14 (15.9) | < 0.01 |

| Fusidic acid | 0 | 1 (1.1) | > 0.99 |

| Gentamicin | 11 (15.9) | 7 (8.0) | 0.12 |

| Rifampin | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 0.50 |

| Quinupristin/Dalfopristin | 0 | 0 | NA |

| TMP/SMX | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 0.44 |

| Tetracycline | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.3) | > 0.99 |

Vancomycin MIC of patients in the first 3 years was higher than that in patients in the final 3 years (1.11 mg/L vs. 1.03 mg/L, p < 0.01). No significant difference was noted in agr dysfunction and spa type. When comparing the antibiotic resistance of the two groups, the rates of resistance to erythromycin were significantly higher in patients in the first 3 years (42.0% [29/69] vs. 15.9% [14/88], p < 0.01).

Annual changes in clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with community-onset vs. hospital-acquired infection

We analyzed patients with community-onset and HA infection (Tables 3 and 4). Metastatic infection (RR 0.89; p = 0.04) and recurrent bacteremia (RR 0.64; p = 0.01) decreased in patients with community-onset infection, but no change was noted in those with HA infection. The resistance rate to erythromycin decreased significantly during the study period (RR 0.87; p = 0.01) in patients with community-onset infection but there was no significant change in those with HA infection. Vancomycin MIC decreased annually by 0.01 (R2 = 0.032; p = 0.03) and resistance rate to ciprofloxacin increased (RR 1.24; p = 0.03) in patients with HA infection during the study period.

Table 3.

Annual changes in the clinical and microbiological characteristics of 147 patients with community-onset infection.

| Characteristic | Number of patients (%) | Annual change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Age (year), median (IQR) | 65 (54–73) | NA | NA |

| Male | 92 (62.6) | NA | NA |

| Underlying disease | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 61 (41.5) | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 0.81 |

| Solid tumor | 48 (32.7) | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | 0.67 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 18 (12.2) | 1.06 (0.91–1.24) | 0.47 |

| End state renal disease | 27 (18.4) | 0.96 (0.85–1.09) | 0.54 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 0.04* | 0.56 |

| APACHE II, median (IQR) | 15 (11–19) | 0.01* | 0.97 |

| Pitt bacteremia score, median (IQR) | 0 (0–2) | 0.01* | 0.86 |

| Septic shock | 13 (8.8) | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) | 0.34 |

| Central venous catheter | 22 (15.0) | 1.03 (0.89–1.18) | 0.72 |

| Prosthetic devicea | 37 (25.2) | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | 0.43 |

| Characteristics of infection | |||

| CVC-related infection | 15 (10.2) | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) | 0.41 |

| Primary bacteremia | 19 (12.9) | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) | 0.34 |

| Bone and joint infection | 22 (15.0) | 0.96 (0.84–1.10) | 0.54 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 22 (15.0) | 1.06 (0.92–1.22) | 0.44 |

| Pneumonia | 14 (9.5) | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) | 0.34 |

| Infective endocarditis | 10 (6.8) | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.55 |

| Metastatic infection | 36 (24.5) | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 0.04 |

| Persistent bacteremia (≥ 3 d) | 69 (46.9) | 0.94 (0.87–1.02) | 0.14 |

| Recurrent bacteremia within 12 weeks | 9 (6.1) | 0.64 (0.47–0.87) | 0.01 |

| 30-d mortality | 15 (10.2) | 1.10 (0.93–1.32) | 0.27 |

| 12-week mortality | 29 (19.7) | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 0.95 |

| Infection-attributable mortality | 21 (14.3) | 1.05 (0.91–1.21) | 0.49 |

| In-hospital crude mortality | 15 (10.2) | 1.08 (0.91–1.28) | 0.39 |

| Vancomycin MIC (BMD), mean ± SD (mg/L) | 1.10 ± 0.02 | − 0.01*b | 0.06 |

| agr dysfunction | 18 (12.2) | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) | 0.85 |

| SCCmec type | |||

| SCCmec IV | 147 (100.0) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | > 0.99 |

| SCCmec IVa | 129/147 (87.8) | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 0.81 |

| spa type | |||

| t324 | 67 (45.6) | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | 0.35 |

| t664 | 20 (13.6) | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) | 0.90 |

| t148 | 19 (12.9) | 0.99 (0.86–1.15) | 0.93 |

| Others | 25 (17.0) | NA | NA |

| Antibiotic resistance | |||

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanate | 139 (94.6) | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | 0.97 |

| Clindamycin | 27 (18.4) | 0.99 (0.87–1.12) | 0.86 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 10 (6.8) | 1.06 (0.86–1.30) | 0.60 |

| Erythromycin | 38 (25.9) | 0.87 (0.78–0.96) | 0.01 |

| Fusidic acid | 1 (0.7) | NA | NA |

| Gentamicin | 25 (17.0) | 0.92 (0.81–1.10) | 0.23 |

| Rifampin | 3 (2.0) | 1.24 (0.80–1.93) | 0.34 |

| Quinupristin/Dalfopristin | 0 | NA | NA |

| TMP/SMX | 1 (0.7) | NA | NA |

| Tetracycline | 4 (2.7) | 1.02 (0.74–1.41) | 0.91 |

*A linear regression model was used for analysis.

aProsthetic device included orthopedic devices (8 patients), cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (1 patients), prosthetic valves (5 patients), and vascular grafts (24 patients) in patients with persistent bacteremia.

bResult of linear regression: R2 = 0.025, vancomycin MIC = 22.07 + (− 0.01) × year.

Table 4.

Annual changes in clinical and microbiological characteristics of 145 patients with hospital-acquired infection.

| Characteristic | Number of patients (%) | Annual change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Age (year), median (IQR) | 62 (49.5–70.5) | NA | NA |

| Male | 83 (57.2) | NA | NA |

| Underlying disease | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 47 (32.4) | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.79 |

| Solid tumor | 59 (40.7) | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) | 0.37 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 24 (16.6) | 1.10 (0.96–1.26) | 0.16 |

| End state renal disease | 14 (9.7) | 1.09 (0.91–1.30) | 0.34 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 2 (2–5) | 0.06* | 0.36 |

| APACHE II, median (IQR) | 16 (11–21) | − 0.04* | 0.85 |

| Pitt bacteremia score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | − 0.02* | 0.74 |

| Septic shock | 20 (13.8) | 0.99 (0.86–1.15) | 0.92 |

| Central venous catheter | 66 (45.5) | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | 0.99 |

| Prosthetic devicea | 21 (14.5) | 1.02 (0.89–1.18) | 0.75 |

| Characteristics of infection | |||

| CVC-related infection | 43 (29.7) | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) | 0.38 |

| Primary bacteremia | 23 (15.9) | 0.91 (0.79–0.15) | 0.19 |

| Bone and joint infection | 11 (7.6) | 0.95 (0.78–1.16) | 0.59 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 4 (2.8) | 1.09 (0.79–1.52) | 0.61 |

| Pneumonia | 10 (6.9) | 1.21 (0.97–1.52) | 0.09 |

| Infective endocarditis | 4 (2.8) | 1.19 (0.84–1.68) | 0.32 |

| Metastatic infection | 21 (14.5) | 0.88 (0.76–1.03) | 0.11 |

| Persistent bacteremia (≥ 3 d) | 47 (32.4) | 0.93 (0.84–1.02) | 0.12 |

| Recurrent bacteremia within 12 weeks | 4 (2.8) | 0.84 (0.59–1.20) | 0.34 |

| 30-d mortality | 19 (13.1) | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | 0.37 |

| 12-week mortality | 36 (24.8) | 1.05 (0.94–1.17) | 0.41 |

| Infection-attributable mortality | 17 (11.7) | 1.11 (0.94–1.30) | 0.22 |

| In-hospital crude mortality | 24 (16.6) | 1.05 (0.92–1.19) | 0.51 |

| Vancomycin MIC (BMD), mean ± SD (mg/L) | 1.06 ± 0.01 | − 0.01*b | 0.03 |

| agr dysfunction | 13 (9.0) | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 0.57 |

| SCCmec type | |||

| SCCmec IV | 144 (99.3) | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | 0.95 |

| SCCmec IVa | 122/144 (84.7) | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 0.65 |

| spa type | |||

| t324 | 72 (49.7) | 0.97 (0.89–1.04) | 0.37 |

| t664 | 22 (15.2) | 0.93 (0.80–1.07) | 0.30 |

| t148 | 14 (9.7) | 0.95 (0.80–1.14) | 0.60 |

| Others | 24 (16.6) | NA | NA |

| Antibiotic resistance | |||

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanate | 132 (91.0) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 0.78 |

| Clindamycin | 31 (21.4) | 0.98 (0.87–1.01) | 0.73 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 13 (9.0) | 1.24 (1.02–1.52) | 0.03 |

| Erythromycin | 37 (25.5) | 0.91 (0.82–1.02) | 0.10 |

| Fusidic acid | 2 (1.4) | 1.16 (0.72–1.86) | 0.56 |

| Gentamicin | 14 (9.7) | 0.99 (0.83–1.18) | 0.92 |

| Rifampin | 2 (1.4) | 0.98 (0.61–1.55) | 0.92 |

| Quinupristin/Dalfopristin | 0 | NA | NA |

| TMP/SMX | 1 (0.7) | NA | NA |

| Tetracycline | 4 (2.8) | 1.12 (0.80–1.57) | 0.50 |

*A linear regression model was used for analysis.

aProsthetic device included orthopedic devices (six patients), cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (three patients), prosthetic valves (six patients), and vascular grafts (six patients) in patients with persistent bacteremia.

bResult of linear regression: R2 = 0.032, vancomycin MIC = 21.57 + (− 0.01) × year.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the clinical, microbiological, and genotypic changes in ST72 MRSA bacteremia over 11 years. The RR of MRSA bacteremia decreased and among these, the RR of ST72 MRSA increased during the study period. S. aureus pneumonia increased. Metastatic infection, persistent bacteremia, and recurrent bacteremia decreased during the study period. The rate of erythromycin resistance decreased significantly over the 11 years.

PVL-negative ST72 MRSA is a major CA-MRSA strain in South Korea and is an important cause of nosocomial infection. The incidence of infections caused by ST72 MRSA is increasing in both community and healthcare settings. Kim et al.6 reported that ST72 MRSA isolates constituted 34.7% of CA-MRSA infection and 4.2% of HA-MRSA infection. In blood stream infection, 22.5–25.0% of MRSA bacteremia were ST72 MRSA and 21.0% of HA-MRSA bacteremia were ST72 MRSA22,23. In this study, MRSA bacteremia levels decreased over 11 years, but ST72 MRSA increased significantly. ST72 MRSA levels of patients were significantly higher in the final 3 years than in the first 3 years. A large proportion of ST72 MRSA bacteremia were HA infections.

Previous studies have reported conflicting results regarding the effect of ST72 MRSA on the clinical outcome of MRSA infection24,25. Park et al.23 reported that ST72-SCCmecIV was associated with reduced mortality compared with ST5-SCCmecII. In this study, 30-d and 12-week mortality did not differ over the study period. CVC-related infection, bone and joint infection, and infective endocarditis have been suggested as risk factors for bacteremia complication26–28. In the present study, there were no changes in CVC-related infection, bone and joint infection, and infective endocarditis, but the incidence of bacteremia complications, such as metastatic infection, persistent bacteremia, and recurrent bacteremia, decreased. In subgroup analysis, metastatic infection and recurrent bacteremia only decreased in community-onset infection. These results suggest changes in community-onset MRSA, and further research is warranted.

A high vancomycin MIC is associated with worse clinical outcomes and treatment failure29–31. Rybak et al.32 reported an increase in the vancomycin MIC of S. aureus from 1986 to 2007. The cell wall-active antibiotics inhibit bacterial growth by inhibiting peptidoglycan biosynthesis33. Molecular events of bacteria occur after treatment with cell wall-active antibiotics34,35. S. aureus activates a protective cell wall stress stimulons in response to the inhibition of cell envelope damage or cell wall synthesis caused by several antibiotics34,36,37. These factors probably increase the vancomycin MIC. In this study, the vancomycin MIC decreased over the 11-year study period, and the change was significant in HA infection. This may be due to the difference in the study period or study lesions. Additionally, there may be changes in microbiological and genomic factors of S. aureus. Further studies are necessary to assess changes in the microbiological and genomic factors of S. aureus that are associated with vancomycin MIC.

In Korea, resistance rates to clindamycin, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin were lower in ST72-SCCmecIV MRSA than in ST5-SCCmecII MRSA strain6,9,23. The resistance rate of ST72 MRSA to erythromycin was from 35.4% to 60.0%9,23. In this study, the erythromycin resistance rate of ST72 MRSA decreased over the 11-year study period significantly. The resistance rate of ST72 MRSA in the final 3 years was significantly lower than ST72 MRSA in the first 3 years (15.9% vs. 42.0%, p < 0.01). In subgroup analysis, the erythromycin resistance rate of ST72 MRSA decreased only in community-onset infection. Several mechanisms cause erythromycin resistance to S. aureus; the presence of multicomponent macrolide efflux pumps (msrA, msrB) and enzymatic modification (EreA, EreB) of the antibiotics by enzymes38–41. In addition, macrolide resistance genes are present in erythromycin-resistant S. aureus42. Reduced use of macrolides or altered resistance genes of ST72 MRSA may contribute to decreased erythromycin resistance. Further studies are needed regarding changes in the mechanisms of erythromycin resistance.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center study and our findings cannot be generalized to South Korea. Second, we evaluated ST72 MRSA types only, but analysis with other MRSA types, such as ST5 and ST239, may be helpful for understanding changes in S. aureus in Korea. However, this was the first large-scale study to analyze longitudinal changes in ST72 MRSA in Korea. This study will benefit future studies in their analysis of changes in S. aureus in community and nosocomial environments.

In conclusion, ST72 MRSA is an important pathogen in both community and nosocomial settings and its incidence increased over the 11-year study period. Bacteremia complication, vancomycin MIC, and resistance rate to erythromycin decreased, and these results suggest changes in the characteristics of ST72 MRSA. Further studies, including genome-wide studies, are needed to understand the reasons for changes of ST72 MRSA.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank BO MIN KWON and Kyeongmi Lee for their support with the data collection.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design of the study. Data collection was performed by E.M.Y., E.S.K., H.M.C., Y.W.L., and S.M.B. E.M.Y. analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. J.W.J., M.J.K., Y.P.C., S.H.K., S.H.C., S.O.L., and Y.S.K. commented and revised previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea [grant number HI15C2918].

Data availability

The data of this study are available by contacting the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.DeLeo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2010;375:1557–1568. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61999-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song JH, et al. Spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus between the community and the hospitals in Asian countries: An ANSORP study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011;66:1061–1069. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otter JA, French GL. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains as a cause of healthcare-associated infection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011;79:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diekema DJ, et al. Continued emergence of USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States: Results from a nationwide surveillance study. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014;35:285–292. doi: 10.1086/675283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seybold U, et al. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;42:647–656. doi: 10.1086/499815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim ES, et al. A survey of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Korea. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:1108–1114. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park C, et al. Predominance of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec type IVA in South Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:4021–4026. doi: 10.1128/jcm.01147-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joo EJ, et al. Community-associated Panton-Valentine leukocidin-negative meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone (ST72-MRSA-IV) causing healthcare-associated pneumonia and surgical site infection in Korea. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012;81:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung JY, Lee J, Choi EH, Lee HJ. Changes in molecular epidemiology of community-associated and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Korean children. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;74:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joo EJ, Choi JY, Chung DR, Song JH, Ko KS. Characteristics of the community-genotype sequence type 72 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates that underlie their persistence in hospitals. J. Microbiol. 2016;54:445–450. doi: 10.1007/s12275-016-6157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow JW, et al. Enterobacter bacteremia: Clinical features and emergence of antibiotic resistance during therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991;115:585–590. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-8-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman ND, et al. Health care–associated bloodstream infections in adults: A reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002;137:791–797. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mermel LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the infectious diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1–45. doi: 10.1086/599376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li JS, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000;30:633–638. doi: 10.1086/313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000;38:1008–1015. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.3.1008-1015.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2155–2161. doi: 10.1128/aac.46.7.2155-2161.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shopsin B, et al. Prevalence of agr specificity groups among Staphylococcus aureus strains colonizing children and their guardians. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:456–459. doi: 10.1128/jcm.41.1.456-459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweizer ML, et al. Increased mortality with accessory gene regulator (agr) dysfunction in Staphylococcus aureus among bacteremic patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1082–1087. doi: 10.1128/aac.00918-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SH, et al. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains as a cause of healthcare-associated bloodstream infections in Korea. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2009;30:146–155. doi: 10.1086/593953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park KH, et al. Community-associated MRSA strain ST72-SCCmecIV causing bloodstream infections: Clinical outcomes and bacterial virulence factors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015;70:1185–1192. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chong YP, et al. Persistent Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: A prospective analysis of risk factors, outcomes, and microbiologic and genotypic characteristics of isolates. Medicine (Baltimore) 2013;92:98–108. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318289ff1e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang HC, et al. Difference in agr dysfunction and reduced vancomycin susceptibility between MRSA bacteremia involving SCCmec types IV/IVa and I-III. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkins C, et al. Persistent Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: An analysis of risk factors and outcomes. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167:1861–1867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YM, et al. Long-term methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia persisting for more than 2 weeks: Risk factors and outcomes. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020;39:773–781. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03795-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang FY, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: Recurrence and the impact of antibiotic treatment in a prospective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:333–339. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000091184.93122.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bae IG, et al. Heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate susceptibility phenotype in bloodstream methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from an international cohort of patients with infective endocarditis: Prevalence, genotype, and clinical significance. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;200:1355–1366. doi: 10.1086/606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kullar R, Davis SL, Levine DP, Rybak MJ. Impact of vancomycin exposure on outcomes in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: Support for consensus guidelines suggested targets. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:975–981. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lodise TP, et al. Relationship between vancomycin MIC and failure among patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia treated with vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3315–3320. doi: 10.1128/aac.00113-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rybak MJ, et al. Characterization of vancomycin-heteroresistant Staphylococcus aureus from the metropolitan area of Detroit, Michigan, over a 22-year period (1986 to 2007) J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:2950–2954. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00582-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gale EF, Cundliffe E, Reynolds PE, Richmond MH, Waring MT. The Molecular Basis of Antibiotic Action. 2. New York: Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Utaida S, et al. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the response of Staphylococcus aureus to cell-wall-active antibiotics reveals a cell-wall-stress stimulon. Microbiology (Reading) 2003;149:2719–2732. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyle-Vavra S, Yin S, Challapalli M, Daum RS. Transcriptional induction of the penicillin-binding protein 2 gene in Staphylococcus aureus by cell wall-active antibiotics oxacillin and vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1028–1036. doi: 10.1128/aac.47.3.1028-1036.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jordan S, Hutchings MI, Mascher T. Cell envelope stress response in Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32:107–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuroda M, et al. Two-component system VraSR positively modulates the regulation of cell-wall biosynthesis pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:807–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross JI, Eady EA, Cove JH, Baumberg S. Identification of a chromosomally encoded ABC-transport system with which the staphylococcal erythromycin exporter MsrA may interact. Gene. 1995;153:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00833-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wondrack L, Massa M, Yang BV, Sutcliffe J. Clinical strain of Staphylococcus aureus inactivates and causes efflux of macrolides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996;40:992–998. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milton ID, Hewitt CL, Harwood CR. Cloning and sequencing of a plasmid-mediated erythromycin resistance determinant from Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1992;76:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90377-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitz FJ, et al. Distribution of macrolide-resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus blood-culture isolates from fifteen German university hospitals. M.A.R.S. Study Group Multicentre Study on Antibiotic Resistance in Staphylococci. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2000;19:385–387. doi: 10.1007/s100960050500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are available by contacting the corresponding author upon reasonable request.