Abstract

Stratiform fissured layer within basement aquifers has increasingly been tapped because of its good transmissivity and groundwater storage capacity. This study aims to determine the hydrodynamic properties and thickness of the fissured layer of granitoids in the Tchologo region where access to drinking water has deteriorated over the years. Statistical analysis of the vertical distribution of the linear discharge from 148 boreholes measured from the length below the base of the saprolites has made it possible to characterize the geometry of fissured layer. The useful thickness of the fissured layer was determined from the 80% percentile method. Linear discharge range from 0.0087 to 0.678 m3 h−1.m−1. The thickness of the most transmissive part of the fissured layer is between 20 and 40 m. The 40 m depth is the useful thickness of the hard-rock aquifer. The mean linear discharge and mean discharge for this useful thickness are 0.129 m3 h−1.m−1 and 5.21 m3.h-1, respectively. These results will improve the success rate of drilling in the region because it will be possible to define the average useful depth of the boreholes to be drilled.

Keywords: Hard-rock aquifer, Conducive fissures, Fracture connectivity, Groundwater occurrence, Borehole linear discharge, Côte d’Ivoire

Hard-rock aquifer; Conducive fissures; Fracture connectivity; Groundwater occurrence; Borehole linear discharge; Côte d’Ivoire.

1. Introduction

In regions where geological formations are mainly composed of crystalline basement as is the case in Côte d'Ivoire (more than 97%), the identification of drainage and groundwater accumulation areas is fundamental for aquifer research. Works carried out in crystalline basement environments in Africa, Asia and Europe (Holland and Witthüser, 2011; Jaunat et al., 2016; Roques et al., 2016; Douagui et al., 2018; Tagnon et al., 2020; Kouamé et al., 2019; Maurice et al., 2019; Hasan et al., 2020) show that these areas generally have fissured and fractured aquifers that provide sufficient water flows for population water supplies. However, these aquifers, due to the significant spatial variability of their hydrodynamic properties, are considered discontinuous and therefore complex. The characterization of the main factors influencing borehole productivity and the development of methods for selecting areas suitable for drilling are therefore of major interest.

Recent works (Maréchal et al., 2003; Courtois et al., 2010; Lachassagne et al., 2011; Wyns et al., 2015) have shown that the weathering profile within basement rocks consists, from top to bottom, of a weathering cover, a fissured and fractured zone, and a fresh basement, permeable only locally, where deep tectonic fractures are present. These fractures are generally the drainage and groundwater accumulation areas. It is now accepted that the fissured layer also plays a capacitive and transmissive role by collecting and distributing water from the overlying medium (Leray et al., 2013; Guihéneuf et al., 2014; Dewandel et al., 2017; Koïta et al., 2017). It has a significant porosity from 1 to 5% and a higher permeability from 10–4 to 10-6 m s−1 (Marechal et al., 2003; Mougin et al., 2008; Lachassagne et al., 2011). The origin of fracturing at the fissured zone results from stresses caused by the expansion of minerals during the weathering process (Cho et al., 2003; Wyns et al., 2004; Lachassagne and Wyns, 2005). The existence and intensity of the crack network is controlled by the mineralogy, texture and structure of the rocks (Lachassagne and Wyns, 2005). This horizon is therefore attained by most drilling in basement regions in North America, South America, India, China, Korea, Japan, France, Australia and Africa (Migon and Lidmar-Bergström, 2002; Wyns, 2002; Maréchal et al., 2003; Courtois et al., 2010).

In the Tchologo Region, access to drinking water remains difficult with increasing pressures on water resources due to growing demographics, agricultural activities and the impacts of climate change. Groundwater is the main resource used to meet the needs of populations in this region which is dominated by granitic and granodioritic rocks. However, hydraulic water drillling expeditions have a high failure rate, making living conditions of the population difficult (Kouakou et al., 2016).

Several studies (Tié et al., 2014; Kouakou et al., 2016) have been carried out on the crystalline basement aquifer in the Tchologo region. But none of them focus on the characteristics of the fissured layer. This work aims to determine the thickness and hydrodynamic properties of the fissured layer within the granitoids of the Tchologo Region.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study area

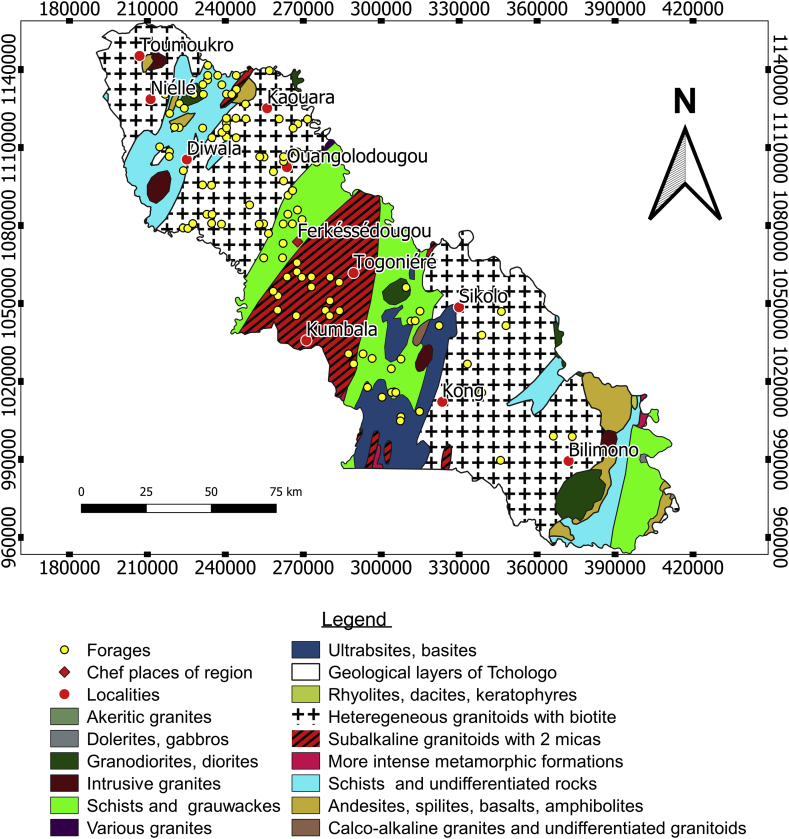

The study area is the Tchologo Region, located in the North of Côte d'Ivoire between longitudes 5°49′800 and 3°46′200 West and latitudes 10°28′200 and 8°37′800 North (Figure 1). It is part of the Savannah District and has a population of 467,958. It covers an area of 17,728 km2, with a density of about 26.39 hts/km2. It is bordered to the North by Burkina Faso and Mali, to the South by the Hambol Region, to the East by the Bounkani Region, and to the West by the Poro Region.

Figure 1.

Geological map of the study area showing borehole locations.

In terms of climate, the Tchologo Region is dominated by the subtropical climate regime. This regime is characterized by two seasons: a rainy season from April to October (7 months) and a dry season from November to March (5 months) which is affected by the Harmattan (Ardoin, 2004).

The geological bedrock consists of volcano-sedimentary rocks and granitoids (Figure 1). The latter are mainly composed of granite and granodiorite. Volcanosedimentary formations consist of metasediments mainly composed of shale introduced by several generations of granitoids. They are covered with metavulcanites, composed of amphibolite, metainesite, rhyolite, meta-basalt, metagabbro and metadolérite.

Two aquifers are indicated in the study area for groundwater extraction. The most important aquifers are the fissured-fractured aquifers. Over the fissured and fractured rocks, the weathered layer may be a porous aquifer.

2.2. Data collection

The dataset for the study consisted of 148 boreholes drilled into the granitoid basement from the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) project database of Tchologo Region in 2008 and 2009. The parameters taken into account are rock type, borehole depth (m), thickness of saprolites, water table and borehole discharge Q (m3.h−1). Q is the airlift flow measured at the end of the drilling by blowing air under pressure at the bottom of the borehole.

The value of borehole discharges are supposed to depend on natural conditions of the study site as opposed to depth data of boreholes that undergo human constraints. These constraints are linked to the depth not to cross and/or to the technician's appreciation on the site. However, the failures observed on the level of technical equipments of boreholes can negatively impact the discharges provided with. On the other hand, the second category of errors within the datasets of boreholes discharges are from grading erros or value estimates. In this study, data credibility of borehole discharges used has been tested by Benford's law as described by Nigrini and Miller (2007). The appearance frequencies of the first digits of the discharges values have been calculated and compared with the ones from the empirical law of Benford. The first digit of a number is the leftmost non-zero digit; any minus sign or decimal point is ignored. The Chi-square test was used to measure the goodness-of-fit to Benford's Law. Chi-square test (χ2) tests a null hypothesis and the relative occurrence frequencies for observed events following a specified frequency distribution. Chi-square statistic is calculated as follows (Mercier et al., 2011) (Equation (1)):

| (1) |

where Oi are the observed values and Ci are the expected values. The numerical value of is then compared with , with n-1 degrees of freedom (n-1 = 8 in this study). We tested the null hypothesis to check if Q value is distributed randomly.

2.3. Determination of the characteristics of the fissured layer

Analysis of the vertical distribution of linear discharge with reference to the borehole length below the base of the saprolites determined the thickness and hydrodynamic characteristics of the fissured and fractured horizon within the granitoids. This method has already been used in recent works (Mougin et al., 2008; Courtois et al., 2010; Douagui et al., 2021) to characterize the fissured layer within plutonic and metamorphic rocks. The discharge linearization takes into account the intrinsic properties of aquifers, including the vertical variation of their properties. Unlike linear discharge, instantaneous discharge integrates the hydraulic input of the entire cross-section of the aquifer (Courtois et al., 2010). Therefore, linear discharge was preferred over air lift discharge in this study to determine the properties of fissured layers.

The useful thickness and productivity of the fissured layer are determined using the statistical method of the cumulative percentage of linear discharge developed by Courtois et al. (2010) and recently applied by Douagui et al. (2021) to evaluate the hydrodynamic properties of the fissured layers of granites and schists aquifers in the Gbêkê Region (Côte d’Ivoire). This method has three main steps. Firstly, the vertical distribution of linear discharge with reference to the borehole length below the base of the saprolites and the cumulative percentage of linear discharge are defined as follows (Equation (2) and Equation (3)):

| (2) |

( (m3.h−1.m−1) is the linear discharge of the borehole a; ( is determined with the borehole length b below the base of the saprolites, and t is the number of boreholes. (m3.h−1) is the borehole discharge; (m) represents the length of the borehole a below the base of the saprolites.]

| (3) |

( (m3.h−1.m−1) is the linear discharge of borehole a. Pq(B) (%) is the cumulative percentage of linear discharge. The calculation of Pq(B) implies taking into account the sample composed by boreholes whose length below the base of the saprolites is less than B (m).

Secondly, the thickness of the most fissured part (the useful thickness) is determined from the length below the base of the saprolites for 80% cumulative percentile of linear discharge below the base of the saprolites over which the lowest slope of the Pq(B) plot occurs. This thickness determined is interpreted as the most transmissive part of the hard-rock aquifer.

Thirdly, the mean productivity of the most transmissive part of the aquifer is calculated as follows (Equation (4) and Equation (5)):

| (4) |

| (5) |

In equations (4) and (5), Bu (m) and qN (Bu) (m3.h−1.m−1) represent the useful thickness of the fissured layer and the mean linear discharge evaluated for Bu, respectively. QN (Bu) is the mean discharge for boreholes that would intersect the length Bu. QN (Bu) is expressed in m3.h−1. k(Bu) is the number of boreholes.

2.4. Mapping the geological cross-section of the weathering profile in the granitoid aquifers

The weathering profile in the granitoid aquifers is established. The mapping is focused on the thickness of the most productive part of the fissured layer, using the 80% linear discharge percentile.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. General statistics on borehole discharge and borehole depth

The boreholes have depths ranging from 52.88 m to 91 m with an mean depth of about 62 m (Table 1). Weathered zones represent on average 44.2% of the total borehole depth. Borehole discharges range from 0.3 to 24 m3 h−1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistical parameters on borehole discharge, borehole depth and weathering thickness in the study area.

| Parameter | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borehole depth (m) | 52.88 | 91.00 | 61.97 | 7.63 |

| Weathering thickness (m) | 2.00 | 63.40 | 27.42 | 11.02 |

| Borehole depth below the base of the saprolites (m) | 13.65 | 74.59 | 34.55 | 11.40 |

| Borehole discharge (m3/h) | 0.3 | 24 | 3.45 | 3.79 |

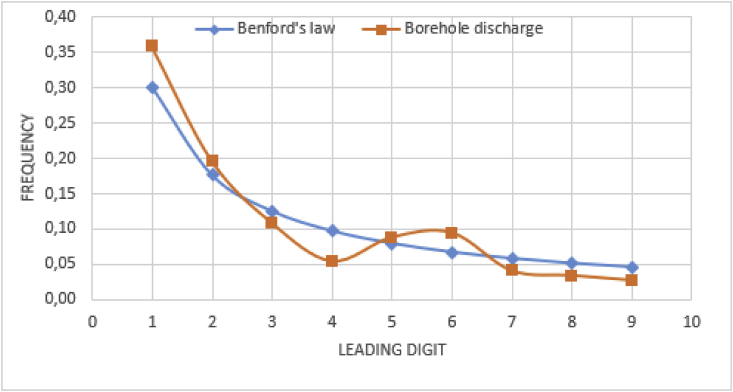

Figure 2 shows the frequency curve of the discharge values in connection with the first digit values according to Benford's law. This seems to follow the pace of the Benford curve. The application of the Chi-square test confirms this trend since (9.69) < (13.36) with p = 0.29. Benford's law can therefore adjust the observed distribution. The information shows that this discharge dataset can be used to model the productivity of the fissured layer.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the pace of borehole discharge curve with Benford's law.

3.2. Vertical distribution of linear discharges below the base of the saprolites

Boreholes in granitic formations and granodiorites have linear discharges ranging from 0.0087 to 0.678 m3 h−1.m−1. Figure 3 shows the vertical distribution of the linear discharge below the base of the saprolites. In general, there is a decrease in linear discharge with depth. This is because the stratiform fissured horizon below the base of the saprolites is characterized by dense fracturing in its first few meters and a decrease in fracture density with depth. It is also notable that the highest values of linear discharges are recorded between 10 and 48 m below the base of the saprolites, while their low levels are found beyond 48 m. This is consistent with the knowledge of basement hydrogeologists who have shown that the fissured layer, located under the saprolites, is the zone that provides the best subsoil permeability and therefore the best dicharges (Cho et al., 2003; Dewandel et al., 2006). Several studies carried out in crystalline basement zones in Africa, Asia and Europe (Guihéneuf et al., 2014; Wyns et al., 2015) have shown that fracture connectivity and, consequently, the great permeability of the fissured zone thereby decrease rapidly with depth. This is linked, as Lachassagne et al. (2014) attest, to the presence of subhorizontal fractures in granite. Wyns et al. (2015), who also share this explanation, point out that fractures of the stratiform fissured layer result more from the weathering process of certain minerals than from stresses generated by magma cooling, later tectonic activity or lithostatic decompression processes. Thus, the weathering of a biotite in granite, by transforming into chlorite or vermiculite, causes a potential increase in crystal volume of about 40%. This transformation takes place within the fissured layer, at a depth of several tens of meters. Under these conditions, expansion is impossible (except in the vicinity of pre-existing cracks) because the medium is rigid, and can be considered infinite in the horizontal plane. This results in an increase in horizontal stresses. In the vertical plane, swelling is only possible when the vertical stress is greater than or equal to the lithostatic load. As soon as the lithostatic load is offset, vertical stress no longer increases and is replaced by expansion, while the horizontal stress continues to increase. The maximum stress is therefore horizontal, while the minimum stress is vertical. When the intensity difference between maximum horizontal and vertical stress exceeds the yield strength of this isotropic rock, cracks (tension slots) appear, which run parallel to the two maximum components of the stress tensor. The authors also explain that in isotropic rocks such as granite, the cracks created will be mainly horizontal. In this study, the majority of the rocks collected are biotite granitoids (granite, granodiorite). They are therefore sandstone geological formations that contain high proportions of expansive minerals. Their likelihood of developing a fissured layer during lateritic weathering is therefore significant.

Figure 3.

Graph showing the correlation between linear discharge and borehole depth below the base of the saprolites for the granitoid rocks. The dashed line shows the shape of linear discharge distribution with the borehole depth.

3.3. Thickness and hydrodynamics of the stratiform fissured layer

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the cumulative percentage of linear discharge values from the base of the saprolites. The graph shows a insignificant rise in the first 20 m. This reflects the low values or even the absence of linear discharges in this area and therefore the absence or non-conductive nature of the cracks within it. These low linear discharge values could also reflect the uncertainty associated with the location of the saprolites-fissured zone interface. In this case, the boreholes may not yet have reached the cracked environment. From 20 to 40 m, the linear discharge values decrease with depth in a linear way. Using the method in relation with slope as described by Courtois et al. (2010), this linear evolution is put in relation with the presence of conductive fissures within the altered and fissured layer.

Figure 4.

Statistical evaluation depth of fissured layer in granitoid formations from Tchologo Region.

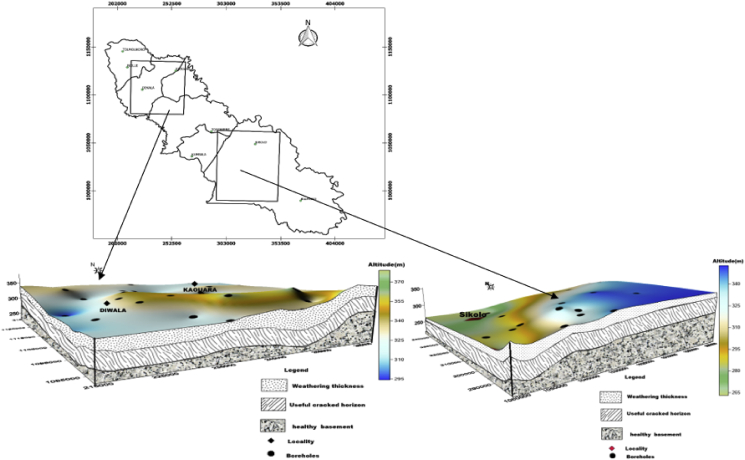

It is the stratum of the horizon which contains the most cracks and is therefore the most productive. At 40 m below the base of the saprolites, a thickness defined by the 80% linear discharge threshold is reached. This depth corresponds to the useful thickness of the fissured layer (Bu). Its productivity deduced from equation (5) is QN(Bu) equal to 5.21 m3 h−1. Above this point, a rapid decrease in linear discharge with depth is apparent. This area of the fissured aquifer is characterized by a low density of conductive cracks. Figure 5 shows the resulting geological cross-sections of the weathering profile in the granitoid aquifers. These are defined as the 80% percentile of cumulative linear discharge.

Figure 5.

Geological cross-sections of the weathering profile in the granitoid aquifers from Tchologo Region. Diwala, Kaoura and Sirkolo are the three sub-prefectures of the mapped areas of the study site.

The properties of the fissured layer within the granitoids of the study area fall within the range of values determined within the granite in Burkina Faso. Indeed, Courtois et al. (2010) who mapped the spatial variations of the fissured layer within the crystalline aquifers of Burkina Faso showed that the useful thickness of fissured zones is between 22 and 40 m. The mean linear discharge and the mean discharge of this productive part are respectively between 0.17 and 0.32 m3 h−1.m−1 and between 4.46 and 8.48 m3 h−1.

The productivity of the useful thickness of the fissured layer of our study is also consistent with those obtained by Mougin et al. (2008) at Bretagne in France (Missillac formation: QN(Bu) = 5.8 m3 h−1 Lanvaux massive: QN(Bu) = 5.8 m3 h−1; Moncontour massive QN(Bu) = 5.1 m3 h−1).

4. Conclusion

The main parameter used in this study to measure the thickness and mean productivity of the most transmissive part of granitoid aquifers in the Tchologo region was the linear discharge. The 40 m depth was the useful thickness of the aquifer. The mean linear discharge and mean discharge for this useful thickness were 0.129 m3 h−1.m−1 and 5.21 m3 h−1, respectively.

Having defined the properties of the fissured layer, it was possible to establish the geological cross-section of the weathering profile in the granitoid aquifers.

These results are important for mapping the region's groundwater potential and for the implementation of water drilling. It is now possible to plot the success rate of new drilling campaigns, the number of boreholes required to supply water to a given population and the average useful depth of the boreholes to be drilled both a priori and statistically. In addition, it should be noted that in areas where the stratiform fissured layer has been eroded or is not saturated with water, discontinuities affecting the hard rock aquifers such as the deep tectonic fractures, may provide an alternative to the stratiform fissured layer for water drilling.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Innocent Kouassi Kouamé, Aristide Gountôh Douagui: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Désiré Kouassi Bouatrin: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Sylvestre Kouakou Assoué Kouadio, Issiaka Savané: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to the “Art and Engineering” research department for providing us with the borehole dataset used for this study. Thanks are also given to the reviewers and editors whose comments on the manuscript are greatly appreciated.

References

- Ardoin . Thèse présentée pour l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université Montpellier II; 2004. Variabilité hydroclimatique et impacts sur les ressources en eau de grands bassins hydrographiques en zone soudano-sahélienne; p. 441P. [Google Scholar]

- Cho M., Choi Y., Ha K., Kee W., Lachassagne P., Wyns R. International Association of Hydrogeologists IAH Conference on ‘‘Groundwater in Fractured Rocks’’. 2003. Relationship between the permeability of hard rock aquifers and their weathering, from geological and hydrogeological observations in South Korea. Prague 15–19 September 2003, Prague. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois N., Lachassagne P., Wyns R., Blanchin R., Bougaïre F.D., Some S., Tapsoba A. Large-scale mapping of hard-rock aquifer properties applied to Burkina Faso. Ground Water. 2010;48:269–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6584.2009.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewandel B., Alazard M., Lachassagne P., Bailly-Comte V., Couëffé R., Grataloup S., Ladouche B., Lanini S., Maréchal J.C., Wyns R. Respective roles of the weathering profile and the tectonic fractures in the structure and functioning of crystalline thermo-mineral carbo-gaseous aquifers. J. Hydrol. 2017;547:690–707. [Google Scholar]

- Dewandel B., Lachassagne P., Wyns R., Marechal J.C., Krishnamurthy N.S. A generalized 3-D geological and hydrogeological conceptual model of granite aquifers controlled by single or multiphase weathering. J. Hydrol. 2006;330:260–284. [Google Scholar]

- Douagui G.A., Kouamé K.I., Kouamé K.B., Savané I. Characterization of the fissured layer properties in crystalline bedrock aquifers of Gbêkê region in the central area of Côte D’Ivoire. In: Ksibi M., Ghorbal A., Chakraborty S., Chaminé H.I., Barbieri M., Guerriero G., Hentati O., Negm A., Lehmann A., Römbke J., Duarte A., Xoplaki E., Khélifi N., Colinet G., Miguel Dias J., Gargouri I., Van Hullebusch E.D., Sánchez Cabrero B., Ferlisi S., Tizaoui C., Kallel A., Rtimi S., Panda S., Michaud P., Sahu J.N., Seffen M., Naddeo V., editors. Recent Advances in Environmental Science from the Euro-Mediterranean and Surrounding Regions. second ed. Vol. 2019. 2021. pp. 1645–1650. (Proceedings of 2nd Euro-Mediterranean Conference for Environmental Integration (EMCEI-2)). Tunisia. [Google Scholar]

- Douagui G.A., Kouassi K.A., Kouamé K.B., Kouadio A.K.S. Using geophysical anomalies for locating rural groundwater supplies in crystalline basement environments of Gbêkê Region, center of Côte d’Ivoire. Env.Wat. Sci. pub. H. Ter. Int. J. 2018;2(4):69–82. http://revues.imist.ma/?journal=ewash-ti/ [Google Scholar]

- Guihéneuf N., Boisson A., Bour O., Dewandel B., Perrin J., Dausse A., Viossanges M., Chandra S., Ahmed S., Maréchal J.C. Groundwater flows in weathered crystalline rocks: impact of piezometric variations and depth-dependent fracture connectivity. J. Hydrol. 2014;511:320–334. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan M., Shang Y., Jin W., Akhter G. Estimation of hydraulic parameters in a hard rock aquifer using integrated surface geoelectrical method and pumping test data in southeast Guangdong, China. Geosci. J. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Holland M., Witthüser K.T. Evaluation of geologic and geomorphologic influences on borehole productivity in crystalline bedrock aquifers of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Hydrogeol. J. 2011;19:1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Jaunat J., Dupuy A., Huneau F., Le Coustumer P. Groundwater flow dynamics of weathered hard-rock aquifers under climate-change conditions: an illustrative example of numerical modeling through the equivalent porous media approach in the north-western Pyrenees (France) Hydrogeol. J. 2016;24:1359–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Koïta M., Yonli H., Soro D., Dara A., Vouillamoz J.-M. Taking into account the role of the weathering profile in determining hydrodynamic properties of hard rock aquifers. Geosciences. 2017;7(3):89. [Google Scholar]

- Kouakou E.G.K., Sombo A.P., Bie G.R., Aka E., Kouamé L.N. Etude comparative de résultats de sondages électriques et des coupes lithostratigraphiques de forages en région de socle (nord de la Côte d’Ivoire) Larhyss J. 2016;(n°25):101–119. ISSN 1112–3680. [Google Scholar]

- Kouamé K.B., Douagui G.A., Kouamé K.I., Yéo W.E., Savané I. Borehole productivity controlling factors in crystalline bedrock aquifer of Gkêkê region, Center of Côte d’Ivoire. J. Water Res. Protection. 2019;11:728–739. [Google Scholar]

- Lachassagne P., Wyns R. Aquifères de socle. Nouveaux concepts. Application à la prospection et la gestion de la ressource en eau. Geosciences. 2005;2:99. [Google Scholar]

- Lachassagne P., Wyns R., Dewandel B. The fracture permeability of Hard Rock Aquifers is due neither to tectonics, nor to unloading, but to weathering processes. Terra. Nova. 2011;23:145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lachassagne P., Dewandel B., Wyns R. The conceptual model of weathered hard rock aquifers and its practical applications. In: Sharp J.M. Jr., editor. Fractured Rock Hydrogeology", N°20 International Association of Hydrogeologists Selected Papers. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group; 2014. pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- Leray S., De Dreuzy J.-R., Bour O., Bresciani E. Numerical modeling of the productivity of vertical to shallowly dipping fractured zones in crystalline rocks. J. Hydrol. 2013;481:64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal J.C., Wyns R., Patrick Lachassagne P., Subrahmanyam K., Touchard F. Anisotropie verticale de la perméabilité de l’horizon fissuré des aquifères de socle: concordance avec la structure géologique des profils d’altération. C. R. Geosci. 2003;335:451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Maurice L.R.G., Taylor C., Tindimugaya A.M., Macdonald P., Johnson A., Kaponda M., Owor H., Sanga H.C., Bonsor W.G., Darling, Gooddy D. Characteristics of high-intensity groundwater abstractions from weathered crystalline bedrock aquifers in East Africa. Hydrogeol. J. 2019;27(2):459–474. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier M., Morin J.F., Viel J.F., Jolly D., Daures J.P., Benazeth S., Meyer N. Collection PACE; Paris: 2011. Biostatistique et probabilités; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Migon P., Lidmar-Bergström K. Deep weathering trough time in central and northwestern Europe: problems of dating and interpretation of geological record. Catena. 2002;49:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mougin B., Allier D., Blanchin R., Carn A., Courtois N., Gateau C., Putot E., Jegou J.-P., Lachassagne P., Stollsteiner P., Wyns R. BRGM/RP-56457-FR; 2008. SILURES, Bretagnes. Rapport Final, Année 5; p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- Nigrini J.M., Miller J.S. Benford’s law applied to hydrology Data: results and relevance to other geophysical data. Math. Geol. 2007;39:469–490. [Google Scholar]

- Roques C., Bour O., Aquilina L., Dewandel B. High-yielding aquifers in crystalline basement: insights about the role of fault zones, exemplified by Armorican Massif, France. Hydrogeol. J. 2016:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tagnon O.B., Assoma T.V., Mangoua O.M.J., Douagui G.A., Fernand Koffi Kouamé K.F., Savané I. Contribution of SAR/RADARSAT-1 and ASAR/ENVISAT images to geological structural mapping and assessment of lineaments density in Divo-Oume area (Côte d’Ivoire). Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2020;23(2):231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Tié Y.H., Ouédraogo M., Kouassi K.L., Kamagaté B., Yao B., Biémi J. Géomorphologie et productivité des forages dans le nord du bassin du fleuve Comoé en Côte d’Ivoire. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2014;8(2):755–765. [Google Scholar]

- Wyns R. Climat, eustatisme, tectonique : quels contrôles pour l’altération continentale ? Exemple des séquences d’altération cénozoïques en France. Bull. Inf. Géol. Bass. Paris. 2002;39(2):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wyns R., Baltassat J.M., Lachassagne P., Legtchenko A., Vairon J. Application of proton magnetic resonance soundings to groundwater reserves mapping in weathered basement rocks (Brittany, France) Bull. Soc. Geol. Fr. 2004;175:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wyns R., Dewandel B., Lachassagne P. Actes de la Conférences « Aquifères de socle: le point sur les concepts et les applications opérationnelles ». 20èmes Journées techniques du Comité Français d'Hydrogéologie de l'Association Internationale des Hydrogéologues. 11-13 Juin 2015, Auditorium ICES, La Roche-sur-Yon. 2015. Origine de la fracturation des aquifères de socle : quels sont les facteurs qui contrôlent les propriétés de l'horizon fissuré? p. 8. Vendée, France. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.