Abstract

Recent evidence indicates that niclosamide is an anti-cancer compound that is able to inhibit several signaling pathways. Although niclosamide has previously been identified by high-throughput screening platforms as a potential effective compound against several cancer types, no direct binding interactions with distinct biological molecule(s) has been established. The present study identifies key signal transduction mechanisms altered by niclosamide in ovarian cancer. Using affinity purification with a biotin-modified niclosamide derivative and mass spectrometry analysis, several RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) were identified. We chose the two RBPs, FXR1 and IGF2BP2, for further analysis. A significant correlation exists in which high-expression of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 is associated with reduced survival of ovarian cancer patients. Knockdown of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 in ovarian cancer cells resulted in significantly reduced cell viability, adhesion, and migration. Furthermore, FXR1 or IGF2BP2 deficient ovarian cancer cells exhibited reduced response to most doses of niclosamide showing greater cell viability than those with intact RBPs. These results suggest that FXR1 and IGF2BP2 are direct targets of niclosamide and could have critical activities that drive multiple oncogenic pathways in ovarian cancer.

Keywords: niclosamide, ovarian cancer, RNA-binding protein, FXR1 and IGF2BP2

FXR1 and IGF2BP2 are direct targets of niclosamide and could have critical activities that drive multiple oncogenic pathways in ovarian cancer.

Introduction

Niclosamide is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug, used for decades in the treatment of helminths in humans [1–3]. In the past several years, mounting evidence has accumulated from us and others that niclosamide is an inhibitor that is able to target several signaling pathways such as WNT/CTNNB1, mTORC1, STAT3, NFκB, Notch, and Hedgehog signaling [4–17]. The anticancer activities of niclosamide contribute to its action against multiple cancers, such as colon, prostate, ovarian, breast, and lung, indicating that niclosamide can be developed for novel treatments beyond helminthiasis [18]. We have reported that niclosamide most efficiently abrogated WNT7A/β-catenin signaling, inhibiting β-catenin transcriptional activity, cell viability, and increased cell death [11]. Furthermore, niclosamide decreased cell migration following an increase in E-cadherin subsequent to decreased levels of SLUG. Oral niclosamide treatment inhibited tumor growth and progression in an intraperitoneal xenograft mouse model representative of human ovarian carcinoma (OvCa) [11]. Several groups have also reported that niclosamide is active against cancer cells targeting WNT/β-catenin signaling [10, 12–15], and can target chemoresistant stem-like cancer cells [6, 15, 17, 19, 20], leading us to consider it as a promising drug for OvCa therapy.

Niclosamide is a potent inhibitor of several biological signaling pathways, which when inactivated in vitro and in vivo elicit anti-cancer effects [16, 18]. However, it is unclear if a specific interaction with biological molecule(s) directly or indirectly drives these observations as no direct binding interaction between niclosamide and distinct biological molecule(s) has been established [18]. It is likely that niclosamide’s ability to inhibit oncogenic pathways [4–17] stems from its ability to directly interfere with biological core molecule(s) within signal transduction pathways. Niclosamide is a member of the salicylanilide class of pharmacologic agents and is a derivative of salicylic acid. Direct binding targets and inhibitory mechanisms interacting with other agents of this molecular class have been identified [18]. Therefore, we sought to identify target proteins that niclosamide directly binds to OvCa using biotinylated niclosamide derivatives as affinity reagents. We report niclosamide’s potential biological targets and assess their oncogenic activates with the target’s underlying mechanisms of action.

Materials and methods

Cells

ES2, OV90, OVCAR3, and SKOV3, and OVCAR4 and OVCAR5 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and Millipore, respectively. A2780, IP1 and OVCAR8 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, the MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Covance, respectively. KURAMOCHI and OVSAHO were obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (JCRB). A2780, ES2, OVCAR5, OVCAR8, SKOV3, and IP1 were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 200 mM glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin, OVCAR4, Kuramochi and OVSAHO were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 200 mM glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin, OV90 was M199 with 15% FBS and 200 mM glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin, OVCAR3 was RPMI 1640 with 20% FBS and 200 mM glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. All cells were routinely tested for cell proliferation and mycoplasma contamination, and they showed similar growth rates and were negative for mycoplasma throughout the experiments. All experiments were performed in four independent trials with triplicate measurement for each treatment and time point.

Biotinylated niclosamide

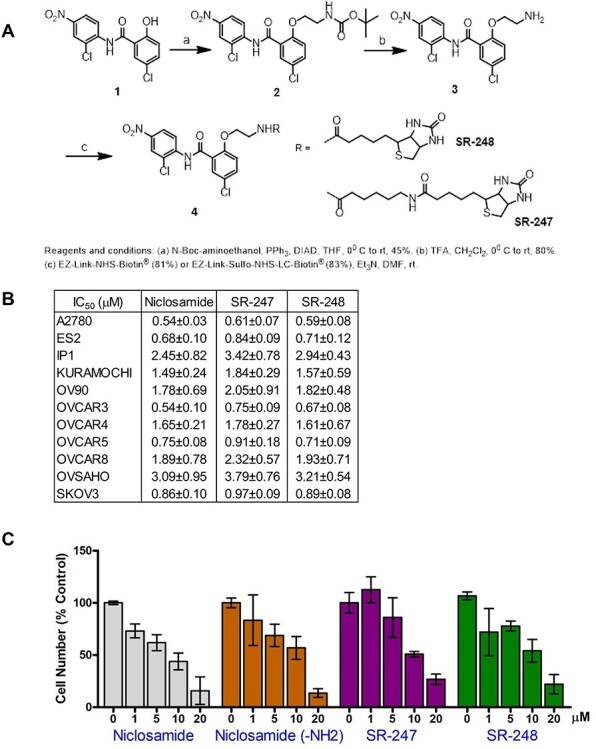

Biotinylated niclosamide was synthesized following a modified procedure from the previous report ([21] and Figure 1A). Figure 1A, 1: Niclosamide. Figure 1A, 2: Tert-butyl (2-(4-chloro-2((2-chloro-4 nitrophenyl)carbamoyl)phenoxy)ethyl)carbamate. To a solution of niclosamide in Figure 1A, 1 (100 mg, 0.30 mmol) and PPh3 (120 mg, 0.46 mmol) in dry tetrahydrofuran anhydrous (THF, 5 mL) at 0°C was added N-Boc-aminoethanol (49 mg, 0.30 mmol) in dry THF (5 mL) followed by diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD) (93 mg, 0.46 mmol) slowly. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h and was then concentrated. The crude residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate and washed with 1 N NaOH followed by brine solution. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated and the crude product was purified by silica gel column (20 → 100% CH2Cl2 in hexane) to afford 65 mg (45%) of 2 as a white solid. 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR, 400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.45 (s, J = 20.1 Hz, 1H), 8.89 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.28–8.12 (m, 2H), 7.49 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.87 (s, 1H), 4.47–4.31 (m, 2H), 3.72–3.48 (m, 2H), 1.40 (s, J = 20.6 Hz, 9H). Figure 1A, 3: 2-(2-aminoethoxy)-5-chloro-N-(2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl)benzamide. To a solution of 2 (65 mg, 0.14 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added TFA (1 mL) at 0°C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h and was concentrated. The residue was partitioned between ethyl acetate (100 mL) and 1 N NaHCO3 (10 mL) and separated. The organic layer was washed with water and brine solution. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The solid was washed with 5 mL of ethyl acetate and was filtered to give 41 mg (80%) of 3 as a pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.50 (s, 1H), 8.88 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.26–8.19 (m, 2H), 7.49 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 5.30 (s, J = 20.0 Hz, 2H), 4.33 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.26 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H). Figure 1A, 4: 5-chloro-N-(2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl)-2-(2-(5-(2-oxo-hexahydro-thieno[3,4-d]imidazol-4-yl)pentanoylamino)ethoxy)benzamide (SR-248). To a solution of EZ-Link-NHS-Biotin® (100 mg, 0.29 mmol) and Et3N (82 μL, 0.58 mmol) in DMF (3 mL) was added 3 (108 mg, 0.29 mmol) at room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture (25% of total crude) was then purified by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a solvent mixture of acetonitrile:water (0.1% TFA) that was ramped linearly (20 → 70% acetonitrile in water) over a 30 min period to give 36 mg (81%) of 4 as a light yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.38 (s, 1H), 8.89 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.29–8.13 (m, 2H), 7.51 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.05 (s, 1H), 5.80 (s, 1H), 5.14 (s, 1H), 4.61–4.20 (m, 4H), 3.76 (dd, J = 11.4, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.12 (dd, J = 11.9, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 3.01–2.84 (m, 1H), 2.73 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 2.26–2.10 (m, 2H), 1.65–1.59 (m, 4H), 1.47–1.31 (m, 2H). HRMS: m/z for C25H27Cl2N5O6S calc: 595.106, found: 595.928. Figure 1A, 4: 5-chloro-N-(2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl)-2-(2-(6-(5-(2-oxo-hexahydro-thieno[3,4-d]imidazol-4-yl)pentanoylamino)hexanoylamino)ethoxy)benzamide (SR-247). To a solution of EZ-Link-Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin® (100 mg, 0.18 mmol) and Et3N (51 μL, 0.36 mmol) in DMF (2.5 mL) was added 3 (67 mg, 0.18 mmol) at room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture (25% of total crude) was then purified by reverse phase HPLC with a solvent mixture of acetonitrile:water (0.1% TFA) that was ramped linearly (20 → 70% acetonitrile in water) over a 30 min period to give 27 mg (83%) of 4 as a light yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.48 (s, 1H), 8.90 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.26–8.14 (m, 2H), 7.50 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (s, 1H), 6.37 (s, 1H), 5.76 (s, 1H), 5.50 (s, 1H), 4.63–4.28 (m, 4H), 3.74 (dd, J = 10.4, 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.33–3.01 (m, 2H), 2.94 (dd, J = 13.0, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H), 2.29–2.21 (m, 1H), 2.16 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.67–1.54 (m, 6H), 1.51–1.38 (m, 4H), 1.35–1.23 (m, 4H). HRMS: m/z for C31H38Cl2N6O7S calc: 708.190, found: 709.097. NMR spectra are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 1.

Biotinylated niclosamide (A) The O-ethylamino niclosamide, 3, was prepared by Mitsunobu coupling of niclosamide with N-Boc-aminoethanol followed by Boc deprotection using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) followed by Chen et al. [21]. Then, 3 was biotinylated through amide bond formation with either EZ-Link-NHS-Biotin® (SR-248) or EZ-Link-Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin® (SR-247) in presence of Et3N in DMF at room temperature. (B) IC50 of niclosamide, SR-247 and SR-248 in OvCa cell lines. (C) Effects of niclosamide, niclosamide-NH2, (3 in Figure 1A), SR-247, and SR-248 on proliferation of OVCAR4.

Pull-down and LC–MS/MS

OVCAR4 cells were harvested and cell pellets were sonicated. Cell lysates were incubated with niclosamide (20 μM) and SR-248 (20 μM) for 30 min. at 4 C. M280 streptavidin beads (Thermo Fisher) were then added and incubated for 30 min. at 4 C. Beads were captured, washed, and loaded into gel prepared for sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The eluted proteins were visualized with Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining, excised into five gel pieces based on molecular size and digested with trypsin. Tryptic peptides were then subjected to nanoflow liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) analysis with a nano-LCII (Thermo Fisher) coupled to Q Exactive mass spectrometer (There Fisher). The Q Exactive instrument was operated in the data-dependant mode acquiring fragmentation spectra of the top 50 strongest ions and under direct control of Xcalibur software (Thermo Scientific). Obtained tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) spectra were searched against target-decoy human refseq database in Proteome Discoverer 1.3 interface (Thermo Fisher) with Mascot algorithm (Mascot 2.4, Matrix Science). The precursor mass tolerance was confined within 20 ppm with fragment mass tolerance of 0.5 dalton and a maximum of two-missed cleavage allowed. Assigned peptides were filtered with 5% false discovery rate (FDR) and subject to manual verifications. The Spectral assignments from PD1.4 are then converted to the MS-platform independent mzXML format and channeled through a custom pipeline for peptide quantification (integrated Peak Alignment Corrector, iPAC) and protein identification and quantification (grouper, which utilizes iPAC results). iPAC is an in-house built and actively managed program, developed at the Center for Drug Discovery (Baylor College of Medicine), that is employed to obtain optimal area-under-the-curve estimates for the detected peptide peaks. Grouper is an in-house built and actively developed program that assigns detected peptides into gene products and tags corresponding experimental measurements, sum spectral counts, sum protein areas, qualitative bins by peptide FDR and Mascot ion scores, and homology groups by distribution of unique and shared peptides. Finally calculated gene product amount from each group was compared to figure out specific binding proteins for niclosamide and SR-248 compounds.

Cell proliferation

The cell proliferation assay was performed following our previously described methods [11, 22]. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates, and then dose-dependently treated with niclosamide on the next day (18–20 h later). Cell viability was assessed after 48 h of treatment or time-dependently (24–144 h) using a Countess II FL Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher, USA) with trypan blue exclusion to determine viable cell percentage. IC50 was determined using Prism software (Ver. 5.0, GraphPad).

Colony formation

Colony formation was performed using standard method [23]. Briefly, under-layers with 0.6% agar medium were prepared in sex-well plates by combining equal volumes of 1.2% Noble agar and ×2 RPMI-1640 with 20% FBS. Cells (1 × 104/well) were plated in 0.3% agar medium. The surface was kept wet with a small amount of growth media. After 3 weeks, the plates were stained with methylene blue and colonies were photographed and counted.

Cell adhesion, wound healing and migration

Cell adhesion: Cells were seeded in 24-well plates and allowed to attach for 1 or 4 h. Adhered cells were assessed by Amido Black absorbance as described previously [11, 24]. Wound healing using standard method [25] was assessed 24 h after scratch and expressed as the percentage of gap closure. Cell migration assays were performed using a modified Boyden Chamber method with 8-μm pore size polycarbonate membrane 24-well transwells as described previously [11, 24]. Cells were plated with serum-free medium into upper wells, and placed in lower wells containing 500 μL serum-free medium to determine unstimulated migratory ability.

Western blot

A total of 10 μg of protein from whole cell lysates was separated on NuPage Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, USA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked and incubated overnight with primary antibodies: anti-FXR1 (1:1000 dilution, ab129089, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP2 (1:1000 dilution, ab124930, Abcam), anti-ECT2 (1:1000 dilution, 07–136-4MI, Fisher Millipore), anti-TP63 (1:500 dilution, SC-8431, SantaCruz Biotechnology), anti-PRKCI (1:1000 dilution, 2998, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-SOX2 (1:1000 dilution, 3579, Cell Signaling Technology), or anti-actin (1:2000 dilution, 3700, Cell Signaling Technology). Immunoreactivity was visualized with IRDye680 (1:10000 dilution, 926–32222, Li-COR, USA) or IRDye800 (1:10000 dilution, 926–32211, Li-COR, USA) conjugated affinity-purified secondary antibodies using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-COR, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Dunnett or Tukey multiple-comparison post-test was used to identify differences between individual means using Prism software (Ver. 5.0, GraphPad). All data met necessary criteria for the ANOVA analysis including equal variance as determined by Bartlett’s test. All experimental data are presented as mean with standard error of the mean. Unless otherwise indicated, a P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate the survival rates and was evaluated by the log-rank test using GEO datasets: GSE9891 [26] that contained 276 patient samples.

Results

Biotinylated niclosamide and its bioactivity

To identify niclosamide’s direct binding targets, we have prepared “tagged” niclosamide for affinity purification (pull-down) and the LC–MS/MS. We chose the biotin–streptavidin tagging system, because biotin rarely interferes with the function of the labeled component, and the strong interaction between avidin and biotin persists under conditions such as extreme pH, elevated temperatures, and other denaturing environments [27]. As shown in Figure 1A, we synthesized O-ethylamino niclosamide 3 that installs a reactive primary amine that was biotinylated with activated ester reagents to give two biotin-modified niclosamide derivatives (SR-247 and SR-248) connected through relatively-stabilized amide linkages using EZ-Link™ NHS- or Sulfo-NHS-biotin (Thermo Fisher). Modification at the hydroxyl group has been shown not to greatly diminish bioavailability and was chosen due to its simplicity of functionalization vs. alternative modification at the nitro group [21, 28, 29]. To confirm whether SR-247 and SR-248 possess the same biological activity as parental niclosamide, we first evaluated anticancer effects of both compounds on the proliferation of OvCa cell lines (Figure 1BC). These results revealed that both SR-247 and SR-248 showed anti-proliferative activities with nanomolar to low micromolar IC50 that were not significantly different compared with those of parental niclosamide in any of the 11 OvCa cell line examined (Figure 1B). Dose-dependent effects of SR-247 and SR-248 including niclosamide-NH2 (3 in Figure 1A) on proliferation showed similar patterns to niclosamide (Figure 1C). Although both SR-247 and SR-248 showed similar biological activity, SR-248 was chosen for further analysis owing to its smaller size, which may elicit lower steric hindrance with target protein interaction.

Binding targets of niclosamide

Using niclosamide and SR-248, we performed pull-down and the LC–MS/MS to identify unknown target proteins using cell lysate of OVCAR4, which has been characterized as one of the high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) cell lines. Briefly, protein lysates were incubated with SR-248 or unlabeled niclosamide as a negative control prior to pull-down. The eluted proteins were subsequently analyzed by the SDS-PAGE, stained, excised based on the molecular sizes, and fragments generated by trypsin digested. Niclosamide and SR-248 show similar IC50 in multiple cell lines, indicating they possess similar affinities. We thus performed two sets of binding and pull-down with protein lysate, unlabeled parental niclosamide and SR-248. Sequences identified using unlabeled niclosamide were subtracted from the SR-248 results as non-specific. Subsequently, the SR-248 pull-down was subjected to competition with parental niclosamide to identify additional false signals. The obtained MS/MS spectra were matched against the human RefSeq database and a total of 2395 proteins were identified (Supplementary Table 1). Of these, 295 proteins had >1.5-fold binding affinity with SR-248 vs. unlabeled niclosamide. Interestingly, 56 of the 295 proteins were categorized as RNA-binding proteins (RBPs). Representative candidates with their binding affinity (fold-change), incidence of copy number amplification and increased messenger RNA (mRNA) expression (altered %), and poor survival outcome (P-value) in OvCa are shown in Table 1. FXR1, RPL8, RPL6, YTHDF3, TIA1, HNRNPUL1, PABPC4, YTHDF2, YTHDF1, UBAP2L, and IGF2BP2 are RBPs, whereas SCRIB is a scribbled planar cell polarity protein, and PRSS1 is a cationic trypsinogen.

Table 1.

Binding targets of niclosamide.

| Protein | Folda | Altered (%)b | Survival (P-value)c | GO annotations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FXR1 | 1.6E+09 | 33% | 0.0276 | RNA binding and nucleic acid binding |

| RPL8 | 5.8E+08 | 36% | n.s. | poly(A) RNA binding and structural constituent of ribosome |

| RPL6 | 2.4E+08 | 5% | n.s. | poly(A) RNA binding and structural constituent of ribosome |

| YTHDF3 | 24.4 | 22% | 0.0286 | poly(A) RNA binding and m6A-containing RNA binding |

| TIA1 | 20.6 | 6% | n.s. | RNA binding and nucleic acid binding |

| HNRNPUL1 | 8.7 | 15% | 0.0037 | RNA binding and nucleic acid binding |

| PABPC4 | 6.9 | 15% | n.s. | RNA binding and nucleic acid binding |

| YTHDF2 | 5.5 | 10% | 0.0485 | poly(A) RNA binding and m6A-containing RNA binding |

| YTHDF1 | 5.5 | 30% | 0.0083 | poly(A) RNA binding and m6A-containing RNA binding |

| UBAP2L | 3.8 | 17% | 0.0009 | poly(A) RNA binding |

| IGF2BP2 | 2.7 | 30% | 0.0039 | RNA binding and nucleic acid binding |

| SCRIB | 2.5 | 40% | 0.0191 | cellular component, cell polarity |

| PRSS1 | 2.3 | 13% | n.s. | serine-ttee endoeeetidase activitt |

aFold change of binding affinity analyzed by mass-spectrometry (biotinylated niclosamide/niclosamide).

b% of genetic alteration (amplification and mRNA upregulation only) from 591 samples (TCGA, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma) according to the cBioPortal database.

cGene association with poor survival outcome in 276 patients from GSE9891 by Kaplan–Meier method using Prism 7. n.s. = not significant.

Genetic alteration and prognostic impact of FXR1 and IGF2BP2 in OvCa

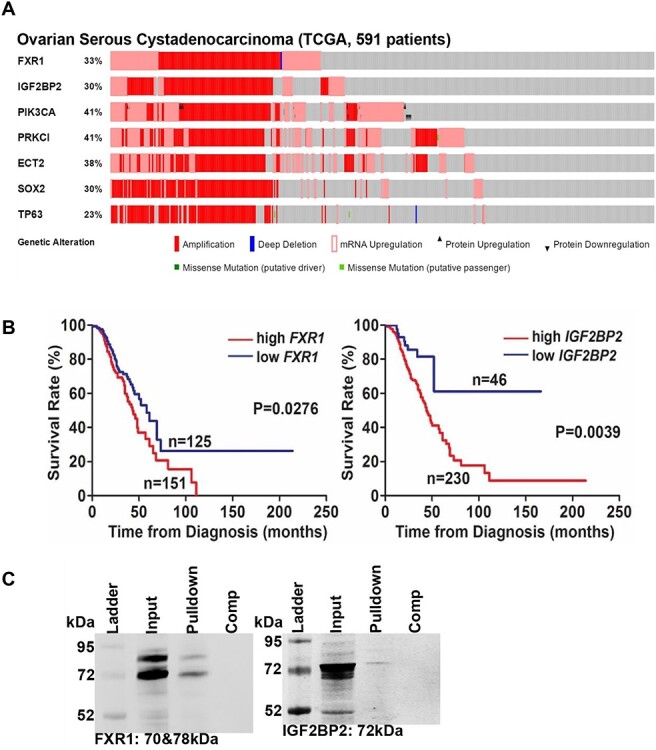

We next examined the genetic alteration of 13 of our identified target proteins, listed in Table 1, using ovarian cystadenocarcinoma data sets (591 patients) from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). FXR1, RPL8, YTHDF1 and IGF2BP2 showed >30% genetic alteration in OvCa, and 7 of 11 RBPs are associated with poor survival outcome in OvCa (double underline and underline in Table 1). Combining the results of binding affinity, genetic alteration and poor survival, we chose two RBPs (FXR1 and IGF2BP2, double underline in Table 1) for further analysis. Both FXR1 and IGF2BP2 have been recently identified as oncogenes, and are located in 3q26–33, which includes frequent genomic alteration with PIK3CA, PRKCI, ECT2, SOX2, and TP63 in lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and other cancers [30, 31]. Figure 2A shows the correlation of amplification and mRNA upregulation of FXR1 and IGF2BP2 with PIK3CA, PRKCI, ECT2, SOX2, and TP63 in OvCa from total 591 patients (TCGA). The prognostic impact of FXR1 and IGF2BP2 in OvCa is shown in Figure 2B. A significant correlation in which high-expression of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 was associated with reduced survival of OvCa patients by log-rank test (P = 0.0276 or P = 0.0039, respectively, Figure 2B). We also performed pull-down/western blot analyses to confirm biotinylated niclosamide’s direct binding to FXR1 and IGF2BP2. Streptavidin Dynabeads successfully pulled down FXR1 or IGF2BP2 complexed with biotinylated niclosamide (SR-248). This interaction was competed away with excess unlabeled niclosamide (Figure 2C), suggesting that both RBPs could be specific direct targets of niclosamide and possess important core functions that drive oncogenic pathways in OvCa.

Figure 2.

RNA-binding proteins in OvCa. (A) Genetic alterations of FXR1, IGF2BP2, PIK3CA, PRKCI, ECT2, SOX2, and TP63 in OvCa. OncoPrint was created by cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics using total 591 OvCa patients from TCGA, which are aligned by genetic alteration side-by-side on the X axis. (B) FXR1 and IGF2BP2 are associated with poor outcome in OvCa. Overall survival rate was calculated in 276 patients from GSE9891 by Kaplan–Meier method using Prism 7. The graphs were shown at the lowest P-value/cutoff which was determined by PrognoScan. (C) OVCAR4 cell lysate was incubated with SR-248 or SR-248 + niclosamide (10-fold competitor) for 16 h, and then M-280 Streptavidin Dynabeads were added and incubated for 1 h. Unbound proteins were removed by washing the beads, and the bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE gel followed by western blot using anti-FXR1 or IGF2BP2.

Oncogenic activity of FXR1 and IGF2BP2 in OvCa

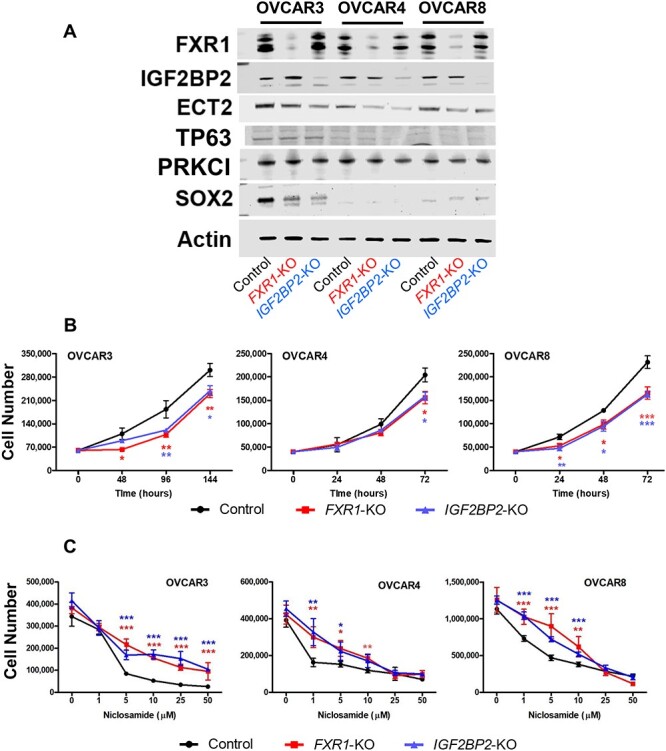

To determine whether FXR1 and IGF2BP2 possess oncogenic activity in OvCa by utilizing a series of in vitro cell culture experiments, we have generated stably ablated FXR1 or IGF2BP2 OvCa cells using the lentiviral CRISPR/Cas9 following manufacturer’s instructions (System Biosciences). Note: OVCAR3, OVCAR4, and OVCAR8 cells were selected, as they have recently been verified as HGSOC cell lines [32, 33], and display the desired HGSOC growth and dissemination parameters [34], as well as express abundant endogenous FXR1 and IGF2BP2. Loss of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 were verified by western blots in each cell line. Although FXR1 and IGF2BP2 are closely located, each gene was solely deleted by CRISPR/Cas9 system using specific gRNAs. Loss of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 did not affect ECT2, TP63, PRKCI and SOX2 that are located nearby in 3q26–33 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Oncogenic activity of FXR1 and IGF2BP2 in OvCa. (A) Generation of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 deficient HGSOC cell lines. The CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to ablate FXR1 or IGF2BP2 in OVCAR3, OVCAR4, and OVCAR8 cells. Two gRNAs were cloned to a lentiviral vector for each gene. After drug selection (puromycin, Cas9) and (blasticidin, gRNA), loss of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 was verified by western blot. (B) Cell proliferation: Cells were seeded in 24-well plates and grown for the indicated culture time. Viable cells were counted using a Countess II FL Automated Cell Counter with trypan blue exclusion. (n = 4 per time). (C) Sensitivity to niclosamide in FXR1 or IGF2BP2 deficient OvCa cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs control at the same time points or doses.

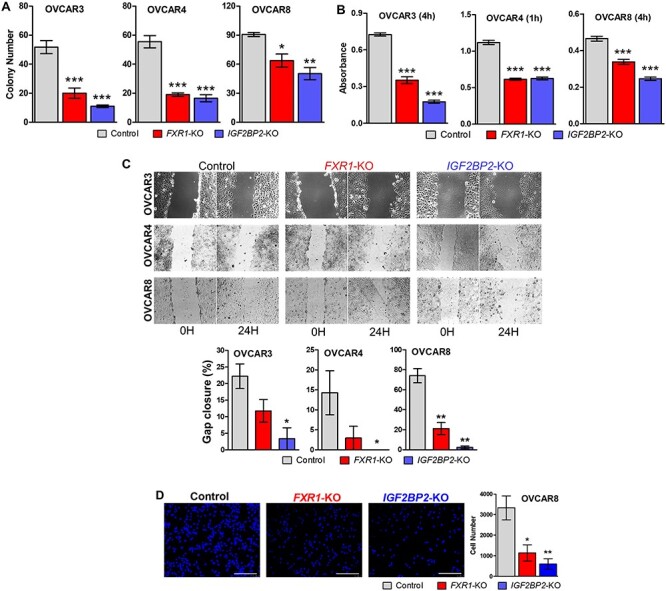

Using these stable cell lines, we examined the effects of FXR1 and IGF2BP2 on oncogenic cell functions. Stably ablated FXR1 or IGF2BP2 time-dependently decreased cell number after 48, 96, and 144, 72, or 24, 48, and 72 h in OVCAR3, OVCAR4, or OVCAR8, respectively (Figure 3B). We next assessed whether loss of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 alters sensitivity to niclosamide in OvCa cells (Figure 3C). FXR1 or IGF2BP2 deficient OvCa cells were more resistant to reduced cell viability induced by niclosamide. However, OVCAR4 and OVCAR8 cells deficient for FXR1 and IGF2BP2 did display similar sensitivity to niclosamide at the highest doses examined. To further assess the potential role of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 in oncogenic cellular function, we performed colony formation, cell adhesion, cell migration. Consistent with cell proliferation results, loss of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 reduced colony formation in all cell lines (Figure 4A). In the cell attachment assay, ablation of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 inhibited cell attachment in all cell lines compared with control (Figure 4B). In OVCAR8 cells, the wound healing scratch assay showed significantly reduced ability to recover after ablation of either FXR1 or IGFBP2 (Figure 4C). In OVCAR3 and OVCAR4 cells, loss of IGFBP2 significantly reduced wound healing capability of the mutant cell lines. However, recovery after ablation of FXR1 was highly variable and while there was a trend towards reduced migration, it did not reach the level of significance in these cell lines. We found that OVCAR3 and OVCAR4 cells did not migrate using a modified Boyden Chamber method with an 8-μm pore size polycarbonate membrane 24-well (Corning). However, the loss of either FXR1 or IGF2BP2 inhibited the migration capability of OVCAR8 cells (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Oncogenic activity of FXR1 and IGF2BP2 in OvCa. (A) Colony formation: Cells (10 000/well) were seeded on 0.6% agar media in 6-well plates and overlaid with 0.3% agar media. After 3 weeks, wells were stained with methylene blue, and colonies were counted (n = 5). (B) Cell adhesion: cells were seeded in 24-well plates and allowed to attach for 1 or 4 hr. Cell adhesion was assessed by Amido Black absorbance (n = 4). (C) Wound healing capability: Wound healing was assessed 24 h after scratch (n = 4) and expressed as the percentage of gap closure. (D) Cell migration: Cell migration assay was performed using a modified Boyden Chamber method with an 8-μm pore size polycarbonate membrane 24-well transwell (n = 4) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs control.

Discussion

In the present study, we have identified niclosamide’s potential biological targets using OvCa cells and a biotin-modified niclosamide derivative. The biotinylated niclosamide (=modified) used to perform pull-down analysis, both SR-247 and SR-248, showed similar bioactivity compared to parental niclosamide. The O-ethylamino niclosamide (3 in Figure 1A) that installed a reactive primary amine at the location of the phenol group also showed similar activity on cell viability in OvCa cells. Thus, modification at the hydroxyl group was shown to not greatly diminish bioavailability, and was acceptable for its modification owing to its simplicity of functionalization versus alternative modification at the nitro group [28, 29]. Indeed, O-ethylamino niclosamide has been reported to possess anticancer activities [21]. Importantly, unaltered niclosamide was able to compete away proteins pulled down by SR-248, showing that the interactions observed are not an artifact of the modification.

Using SR-248 and niclosamide, several RBP were identified as niclosamide’s potential targets. RBPs are key components in RNA metabolism including RNA maturation, surveillance, nucleocytoplasmic transportation, translation and degradation [35, 36]. Recent genetic and proteomic studies have shown that aberrant RBPs contribute to the progression of human diseases including cancer [36]. Because RBPs control post-transcriptional gene expression without concomitant gene mutation, the changes in gene expression are able to contribute to tumor development and confer competitive advantages to cancerous cells. We chose two RBPs, FXR1 and IGF2BP2, for further characterization. Our results showed that FXR1 or IGF2BP2 deficient OvCa cells reduced oncogenic activities such as proliferation, colony formation, adhesion, and migration. Furthermore, high FXR1 or IGF2BP2 expression indicated a poor overall survival rate in OvCa patients, suggesting that aberrant expression of FXR1 and IGF2BP2 are associated with OvCa progression and prognosis. Additionally, niclosamide potentially targets their oncogenic activities. In support of our results, FXR1 has been identified as a new driver in the amplification of 3q26–33 and a poor prognosis marker in lung SCC [37]. FXR1 interacts with PRKCI and ECT2 in lung SCCs [37] and colon cancers [38]. Oncogenic function and clinical relevance of IGF2BP2 has also been reported in various cancers [39–45]. Interestingly, FXR1 and IGF2BP2 are closely located in 3q28 and 3q27.2, respectively. Amplification of both genes, as well as PIK3CA, PRKCI, ECT2, SOX2, and TP63 is significantly correlated in OvCa. While the above-listed genes are closely located in 3q26–33, ablation of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 did not affect the protein levels of those factors.

The present study did not identify niclosamide’s known critical signaling regulators (STAT3 or β-catenin etc.) in our pull-down screen. The results led us to hypothesize that RBPs possess oncogenic functions and subsequently activate oncogenic signaling pathways, i.e. WNT, mTORC1, STAT3 and NFĸB activities as post-transcriptional regulators. Because many RBPs were identified as niclosamide’s direct binding targets, niclosamide likely binds to RNA-binding domains (RBDs) such as the RNA recognition motif (RRM), K homology (KH) domain and/or Piwi/Argonaute/Zwille (PAZ) domain [36]. Indeed, FXR1 and IGF2BP2 possess several common KH domains. Specific direct binding sites of niclosamide to RBPs remain to be studied.

In summary, we are the first to identify verified direct targets of niclosamide. Two potential targets, FXR1 and IGF2BP2, possess oncogenic activities from a series of cellular analyses. Importantly, loss of FXR1 or IGF2BP2 in OvCa cells exhibited reduced sensitivity to niclosamide. Although it remains to be studied how niclosamide inhibits multiple signaling pathways, identifying niclosamide’s direct biological targets provides a better understanding of niclosamide’s inhibitory mechanisms. The present results suggest that both FXR1 and IGF2BP2, are direct binding targets of niclosamide and have critical functions that drive multiple oncogenic pathways in ovarian cancer.

Author contributions

N.S., J.A.M, and K.H. designed research; N.S., J.A.M., S.B., Z.Y., C. P., and K.H. performed research; K.P. and M.M. assisted research techniques; N.S., J.A.M, Z.Y. H.O., and K.H. analyzed data; K.H. wrote the paper; all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

† Grant support: This work was supported by NIH grant CA179214 (to K.H.).

Contributor Information

Nikola Sekulovski, Department of Physiology, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL, USA.

James A MacLean, II, Department of Physiology, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL, USA; Center for Reproductive Biology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA.

Sambasiva R Bheemireddy, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, USA.

Zhifeng Yu, Center for Drug Discovery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA.

Hiroshi Okuda, Tsuruoka Metabolomics Laboratory, National Cancer Center, Tsuruoka, Yamagata, Japan.

Cindy Pru, Center for Reproductive Biology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA.

Kyle N Plunkett, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, USA.

Martin Matzuk, Center for Drug Discovery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA.

Kanako Hayashi, Department of Physiology, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Carbondale, IL, USA; Center for Reproductive Biology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA.

References

- 1. Craig P, Ito A. Intestinal cestodes. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2007; 20:524–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Merschjohann K, Steverding D. In vitro trypanocidal activity of the anti-helminthic drug niclosamide. Exp Parasitol 2008; 118:637–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tanowitz HB, Weiss LM, Wittner M. Diagnosis and treatment of intestinal helminths. I. Common intestinal cestodes. Gastroenterologist 1993; 1:265–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balgi AD, Fonseca BD, Donohue E, Tsang TC, Lajoie P, Proud CG, Nabi IR, Roberge M. Screen for chemical modulators of autophagy reveals novel therapeutic inhibitors of mTORC1 signaling. PLoS One 2009; 4:e7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fonseca BD, Diering GH, Bidinosti MA, Dalal K, Alain T, Balgi AD, Forestieri R, Nodwell M, Rajadurai CV, Gunaratnam C, Tee AR, Duong F et al. Structure-activity analysis of niclosamide reveals potential role for cytoplasmic pH in control of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:17530–17545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jin Y, Lu Z, Ding K, Li J, Du X, Chen C, Sun X, Wu Y, Zhou J, Pan J. Antineoplastic mechanisms of niclosamide in acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells: Inactivation of the NF-kappaB pathway and generation of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res 2010; 70:2516–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li R, Hu Z, Sun SY, Chen ZG, Owonikoko TK, Sica GL, Ramalingam SS, Curran WJ, Khuri FR, Deng X. Niclosamide overcomes acquired resistance to erlotinib through suppression of STAT3 in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2013; 12:2200–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. You S, Li R, Park D, Xie M, Sica GL, Cao Y, Xiao ZQ, Deng X. Disruption of STAT3 by niclosamide reverses radioresistance of human lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2014; 13:606–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wieland A, Trageser D, Gogolok S, Reinartz R, Hofer H, Keller M, Leinhaas A, Schelle R, Normann S, Klaas L, Waha A, Koch P et al. Anticancer effects of niclosamide in human glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19:4124–4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arend RC, Londono-Joshi AI, Samant RS, Li Y, Conner M, Hidalgo B, Alvarez RD, Landen CN, Straughn JM, Buchsbaum DJ. Inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway by niclosamide: A therapeutic target for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 134:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. King ML, Lindberg ME, Stodden GR, Okuda H, Ebers SD, Johnson A, Montag A, Lengyel E, MacLean Ii JA, Hayashi K. WNT7A/beta-catenin signaling induces FGF1 and influences sensitivity to niclosamide in ovarian cancer. Oncogene 2015; 34:3452–3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu W, Lin C, Roberts MJ, Waud WR, Piazza GA, Li Y. Niclosamide suppresses cancer cell growth by inducing Wnt co-receptor LRP6 degradation and inhibiting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. PLoS One 2011; 6:e29290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Osada T, Chen M, Yang XY, Spasojevic I, Vandeusen JB, Hsu D, Clary BM, Clay TM, Chen W, Morse MA, Lyerly HK. Antihelminth compound niclosamide downregulates Wnt signaling and elicits antitumor responses in tumors with activating APC mutations. Cancer Res 2011; 71:4172–4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sack U, Walther W, Scudiero D, Selby M, Kobelt D, Lemm M, Fichtner I, Schlag PM, Shoemaker RH, Stein U. Novel effect of antihelminthic Niclosamide on S100A4-mediated metastatic progression in colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103:1018–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yo YT, Lin YW, Wang YC, Balch C, Huang RL, Chan MW, Sytwu HK, Chen CK, Chang CC, Nephew KP, Huang T, Yu MH et al. Growth inhibition of ovarian tumor-initiating cells by niclosamide. Mol Cancer Ther 2012; 11:1703–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li Y, Li PK, Roberts MJ, Arend RC, Samant RS, Buchsbaum DJ. Multi-targeted therapy of cancer by niclosamide: A new application for an old drug. Cancer Lett 2014; 349:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang YC, Chao TK, Chang CC, Yo YT, Yu MH, Lai HC. Drug screening identifies niclosamide as an inhibitor of breast cancer stem-like cells. PLoS One 2013; 8:e74538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen W, Mook RA Jr, Premont RT, Wang J. Niclosamide: beyond an antihelminthic drug. Cell Signal 2018; 41:89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu C, Lou W, Zhu Y, Nadiminty N, Schwartz CT, Evans CP, Gao AC. Niclosamide inhibits androgen receptor variants expression and overcomes enzalutamide resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20:3198–3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim SY, Kang JW, Song X, Kim BK, Yoo YD, Kwon YT, Lee YJ. Role of the IL-6-JAK1-STAT3-Oct-4 pathway in the conversion of non-stem cancer cells into cancer stem-like cells. Cell Signal 2013; 25:961–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen H, Yang Z, Ding C, Chu L, Zhang Y, Terry K, Liu H, Shen Q, Zhou J. Discovery of O-Alkylamino tethered niclosamide derivatives as potent and orally bioavailable anticancer agents. ACS Med Chem Lett 2013; 4:180–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sekulovski N, Whorton AE, Shi M, MacLean JA II, Hayashi K. Endometriotic inflammatory microenvironment induced by macrophages can be targeted by niclosamidedagger. Biol Reprod 2019; 100:398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hendrix ND, Wu R, Kuick R, Schwartz DR, Fearon ER, Cho KR. Fibroblast growth factor 9 has oncogenic activity and is a downstream target of Wnt signaling in ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 2006; 66:1354–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoshioka S, King ML, Ran S, Okuda H, MacLean JA 2nd, McAsey ME, Sugino N, Brard L, Watabe K, Hayashi K. WNT7A regulates tumor growth and progression in ovarian cancer through the WNT/beta-catenin pathway. Mol Cancer Res 2012; 10:469–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodriguez LG, Wu X, Guan JL. Wound-healing assay. Methods Mol Biol 2005; 294:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tothill RW, Tinker AV, George J, Brown R, Fox SB, Lade S, Johnson DS, Trivett MK, Etemadmoghadam D, Locandro B, Traficante N, Fereday S et al. Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:5198–5208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ziegler S, Pries V, Hedberg C, Waldmann H. Target identification for small bioactive molecules: finding the needle in the haystack. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2013; 52:2744–2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mook RA Jr, Chen M, Lu J, Barak LS, Lyerly HK, Chen W. Small molecule modulators of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2013; 23:2187–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang YW, Yeh TK, Lin KT, Chen WC, Yao HT, Lan SJ, Wu YS, Hsieh HP, Chen CM, Chen CT. Pharmacokinetics of anti-SARS-CoV agent niclosamide and its analogs in rats. J Food Drug Anal 2006; 14:329–333. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qian J, Massion PP. Role of chromosome 3q amplification in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2008; 3:212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, Lawrence MS, Zhsng CZ, Wala J, Mermel CH, Sougnez C, Gabriel SB et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet 2013; 45:1134–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Domcke S, Sinha R, Levine DA, Sander C, Schultz N. Evaluating cell lines as tumour models by comparison of genomic profiles. Nat Commun 2013; 4:2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anglesio MS, Wiegand KC, Melnyk N, Chow C, Salamanca C, Prentice LM, Senz J, Yang W, Spillman MA, Cochrane DR, Shumansky K, Shah SP et al. Type-specific cell line models for type-specific ovarian cancer research. PLoS One 2013; 8:e72162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mitra AK, Davis DA, Tomar S, Roy L, Gurler H, Xie J, Lantvit DD, Cardenas H, Fang F, Liu Y, Loughran E, Yang J et al. In vivo tumor growth of high-grade serous ovarian cancer cell lines. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 138:372–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Glisovic T, Bachorik JL, Yong J, Dreyfuss G. RNA-binding proteins and post-transcriptional gene regulation. FEBS Lett 2008; 582:1977–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lukong KE, Chang KW, Khandjian EW, Richard S. RNA-binding proteins in human genetic disease. Trends Genet 2008; 24:416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qian J, Hassanein M, Hoeksema MD, Harris BK, Zou Y, Chen H, Lu P, Eisenberg R, Wang J, Espinosa A, Ji X, Harris FT et al. The RNA binding protein FXR1 is a new driver in the 3q26-29 amplicon and predicts poor prognosis in human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:3469–3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jin X, Zhai B, Fang T, Guo X, Xu L. FXR1 is elevated in colorectal cancer and acts as an oncogene. Tumour Biol 2016; 37:2683–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Allen WL, Jithesh PV, Oliver GR, Proutski I, Longley DB, Lenz HJ, Proutski V, Harkin P, Johnston PG. The colorectal cancer disease-specific transcriptome may facilitate the discovery of more biologically and clinically relevant information. BMC Cancer 2010; 10:687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Janiszewska M, Suva ML, Riggi N, Houtkooper RH, Auwerx J, Clement-Schatlo V, Radovanovic I, Rheinbay E, Provero P, Stamenkovic I. Imp2 controls oxidative phosphorylation and is crucial for preserving glioblastoma cancer stem cells. Genes Dev 2012; 26:1926–1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kessler SM, Laggai S, Barghash A, Schultheiss CS, Lederer E, Artl M, Helms V, Haybaeck J, Kiemer AK. IMP2/p62 induces genomic instability and an aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma phenotype. Cell Death Dis 2015; 6:e1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kessler SM, Pokorny J, Zimmer V, Laggai S, Lammert F, Bohle RM, Kiemer AK. IGF2 mRNA binding protein p62/IMP2-2 in hepatocellular carcinoma: antiapoptotic action is independent of IGF2/PI3K signaling. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013; 304:G328–G336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li Y, Francia G, Zhang JY. p62/IMP2 stimulates cell migration and reduces cell adhesion in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2015; 6:32656–32668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu W, Li Z, Xu W, Wang Q, Yang S. Humoral autoimmune response to IGF2 mRNA-binding protein (IMP2/p62) and its tissue-specific expression in colon cancer. Scand J Immunol 2013; 77:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Degrauwe N, Schlumpf TB, Janiszewska M, Martin P, Cauderay A, Provero P, Riggi N, Suva ML, Paro R, Stamenkovic I. The RNA binding protein IMP2 preserves glioblastoma stem cells by preventing let-7 target gene silencing. Cell Rep 2016; 15:1634–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1).