Abstract

There is limited research exploring how daily and formal care decision making occurs within African American dementia dyads as well as how these dyads navigate decision making across the dementia trajectory. Through semi-structured interviews, five African American dementia dyads shared their decision-making processes. We used a multimethod approach to the analysis of data, including qualitative and quantitative content analysis and the creation of I Poems. This novel use of I Poems provided a uniquely personal account of the lived experiences of the African American persons living with dementia, while other analyses revealed that within dyads, daily care decision making was led by African American persons living with dementia, whereas formal care decision making varied between dyads. There was intra-dyad congruence regarding who the final decision maker was in daily and formal care. Clinicians and researchers may be able to tailor interventions based on the dyad’s involvement in these decision-making processes.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, decision making, Black American, Qualitative

Introduction

The overall population of older adults is increasing, with the proportion of African American older adults estimated to double by the year 2050 in the United States.1 Research suggests African American older adults in the United States may be more likely to develop dementia than non-Hispanic White or Hispanic older adults– related in part to a greater prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and stroke.2 Despite the increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias within the African American population, there has been limited research focused on daily care (e.g., grooming, cooking, driving, managing finances) and formal care (e.g., use of paid healthcare services) decision making within African American dementia dyads (i.e., African American persons living with dementia and their African American care partners). African American older adults are less likely to receive a formal diagnosis of dementia early in the illness trajectory,3,4 which has been asssociated with receiving formal care that is not culturally sensitive or tailored to their needs. 5 As a result, African American persons living with dementia experience delays in treatment,2,6 which further limit time for care planning and, consequently, increases the risk of morbidity for African American persons living with dementia.4,7,8

Decision-making involvement of persons living with dementia and their care partners

In African American families, both daily and formal care decision making often include the African American dementia dyad and other family members.9,10 Taking a closer look at how decision making occurs within these dyads is important when the goal is to deliver person- and/or family-centered care.

Daily care decision making

Daily care decision making by persons living with dementia has been previously studied within dementia dyads 11–13 and has been shown to be influenced by the person living with dementia’s own cognitive impairment, their relationship with the care partner(s), and their desired level of autonomy.14 When persons living with dementia perceived greater involvement in their own daily care decisions, their well-being, and the well-being of their care partners, was improved.11,15,16 In an integrative review focused on daily care decision making in persons living with early-stage dementia, findings underscore the importance of persons living with dementia being included in daily care decision making because 1) it reinforces their sense of self,17,18 2) it is associated with improved quality of life for persons living with dementia,14–16 and 3) it is associated with improved quality of life for their family care partners.11 Further, care partners report lower levels of depression and less relationship strain when they involve persons living with dementia in daily care decision making.11 In one pilot study in which persons living with dementia were interviewed, authors highlighted the importance of family care partners supporting persons living with dementia’s involvement in daily care decision making as a strategy to combat the symptoms of dementia, indicating the benefit of shared decision making.19 However, family care partners are significantly more likely to have incongruent perspectives when compared with persons living with dementia regarding how involved the person living with dementia is in their own daily care decision making.11,12,20 Each of these studies highlight a missed opportunity to tailor care or provide person-centered care.

Despite evidence supporting incongruent perceptions between care partners and persons living with dementia often result in worse quality of life for these care partners and/or persons living with dementia,21,22 African American persons living with dementia have only been the explicit focus in two recent studies.15,20 These studies highlight that, similar to studies of predominantly non-Hispanic White dementia dyads, there is significant incongruence within dementia dyads regarding how involved persons living with dementia are with daily care decision making,20 but the level of (in)congruence within the dyads and level of daily care decision-making involvement of African American persons living with dementia varies. Three distinct patterns were noted: 1) Incongruent, PLWD Low Involvement, 2) Incongruent, PLWD Moderate Involvement, and 3) Congruent, PLWD High Involvement.20 Other than this study, there has been little research focused on daily care decision making in African American dementia dyads17 and none to our knowledge focused on how these daily care decisions occur within the dyad.

Formal care decision making

Formal care decision making is defined as the decision-making process about using and/or receiving paid services for older adults from a healthcare institution.23 Current dementia caregiving research lacks an emphasis on formal care decision making that is person- and/or family-centered. Instead, most formal care decision making research focuses on the capacity of persons living with dementia to make decisions rather than their engagement or level of involvement in decision making.19 Focusing on capacity centers on the ability of persons living with dementia to make decisions, specifically related to cognitive impairment and dementia illness stage,24 while involvement centers on the person living with dementia being engaged and/or included in the decision-making process.11 Many persons living with mild to moderate dementia report wanting to be a part of making treatment decisions, and most of their care partners agree.25 Yet despite persons living with dementia’s desire to be included in the decision-making process, care partners emphasize the persons living with dementia’s perceived (in)capacity to participate in formal care decisions.25 This focus hinders shared decision making.26

Demographic characteristics of dementia dyads (e.g., sex/gender, age) and the disease stage (e.g., mild) of persons living with dementia are significantly associated with the involvement of persons living with dementia in formal care decision making. Persons living with dementia are more likely to be involved in formal care decision making when they are in the mild stages of the dementia trajectory.27 Compared to men, women care partners are significantly more likely to include the persons living with dementia in formal care treatment decision making,25,27 but are also more likely to overrule male person living with dementia’s formal care decisions.28 In addition, spousal care partners, when compared to non-spousal care partners, are more likely to include the person living with dementia in formal care decision making.27 Furthermore, persons living with dementia are less likely to be included in formal care decision making when they seem to be older, have cognitive impairment beyond mild symptoms, and have care partners who report worse caregiving burden.29 Beyond the mild stage of the dementia trajectory, the final decision maker for formal-care decisions is recommended to be the care partner.29,30 Of note, in each of these data-based studies, African American dementia dyads were less than 20% of the sample.

The lack of inquiry into formal care decision making of African American dementia dyads has important implications. On average, African American dementia dyads lack access and/or underuse most formal care services for persons living with dementia when compared to non-Hispanic white dementia dyads in the United States.5,7,31 Formal-care decision making within African American dementia dyads often involves both members of the dyad, the health care provider, and other trusted family members,5,9,10 which has been found to decrease ethical dilemmas for family care partners and clinicians.19,20 Within African American cultures, older persons living with dementia continue to be perceived as greatly respected family resources.32,33 In one small study of African American family care partners, persons living with dementia’s presence was valued despite their diagnosis of dementia.33 However, there has been little investigation into whether these value-added perceptions translate into increased engagement with the person living with dementia in daily and formal care decision-making.

While there are some studies focused on persons living with dementia being more central to decision-making processes, 17,18,34,35 there are limited firsthand accounts from the perspective of the person living with dementia and/or how they perceive their involvement. This study focused on how decision-making involvement occurred from accounts from both members of African American dementia dyads surrounding daily and formal care for the persons living with dementia. Accordingly, the aims of the current study were to:

Describe how daily and formal care decision-making involvement occurs within African American dementia dyads.

Explore the perspectives of African American persons living with dementia about the decision-making process.

Methods

Design

This qualitative descriptive exploratory study36,37 was conducted from February to August 2019. Design features included purposive snowball sampling,38 semi-structured dyadic interviews,39 and a triangulated approach to analysis, including quantitative40 and qualitative41 content analysis and the novel use of I Poems42,43 using the Listening Guide approach.44

Setting and participants

Using purposive snowball sampling, we recruited African American persons living with dementia and African American family care partners. Given previous research that African American persons living with dementia may not use formal care services,7,31,45 the first author not only advertised for study participants at a large academic health center in the Pacific Northwest, but also in the communities where more African American older adults lived. Recruitment flyers were posted at churches, community centers, beauty salons, and barber shops. Each member of the dyad was compensated ($25 cash) after completing the interviews. Most participants were recruited from the community.

Inclusion criteria for the persons living with dementia included: (a) self-identified as African American, (b) 60 years of age or older, and (c) had a formal diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment/dementia or scored ≤ 26 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a brief, standardized screening tool.46,47 Exclusion criteria included: (a) non-English speaking, and/or (b) self-identified as having a comorbid diagnosis (currently or previously) of a serious mental condition (e.g., bipolar or schizophrenia).48

Inclusion criteria for the care partners included: (a) self-identified as African American, (b) at least 18 years of age, (c) assisting with activities of daily living and/or instrumental activities of daily living for the person living with dementia, and (d) self-identified as a care partner. In one dyad, two care partners were deemed eligible, with one care partner responsible for daily care decisions and the other responsible for formal care decisions. Both care partners were present during the dyadic interviews and only answered the questions related to their established responsibility.

Data collection

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Oregon Health & Science University prior to the initiation of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to data collection, which was conducted in the homes of the persons living with dementia. Persons living with dementia ability to provide consent for the study was measured by their ability to describe the purpose of the study and their expected contribution. Using dyadic interviewing,39 the first author conducted all the interviews using a semi-structured interview guide (Table 1). Each interview began with African American dementia dyads being interviewed together, followed by each member being interviewed separately.39,49 To prevent fatigue, the separate interview with the person living with dementia occurred first. Dyadic interviews lasted on average 45 minutes, with a range from 20–120 minutes. Dyadic vignette field notes,50 created to describe impressions of the dyads individually and as a unit, were collected after each data interview session. In addition, the first author collected demographic information. All interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and reviewed for accuracy.

Table 1.

Semi-structured Interview Guide with Prompts

| Focus Area | Interview Guide |

|---|---|

| Get Acquainted | What is your relationship with each other? What would you like for me to call you during this interview? |

| Formal Care | I am interested in understanding how you two figure out what care [you] need when it comes to [your] memory loss. Who do [you] seek out for help? Probes: Do [you] have a particular doctor you go to for help? Do [you] ever go the emergency room or been hospitalized? Do [you] use paid assistance in the home/home assistance? Do [you] use respite care? How do [you] two make these [formal care] decisions? Probes: what kind of things do [you] think about when [you] make a decision about using [formal care]? Any past experience (good/bad) influenced how [you] decided [regarding formal care use]? |

| Daily Care | When [you] two make day-to-day decisions, is it any different? Probes: Such as with food or meals? Hygiene or bathing? Getting dressed/clothing or going to the beauty salon/barber shop? When it comes to making [formal care and day-to-day] decisions specifically for [name of older adult with memory loss], how are they made? Probes: By the older adult? By family member(s)? Together? |

| Decision Making | Overall, what i think I hear you saying is [describe level of decision-making involvement], is that correct? |

Data analysis

Using a multimethod approach to analysis, each dyadic interview transcript underwent three distinct analyses: qualitative content analysis, the novel use of I Poems, and quantitative content analysis. The findings were then combined.

Qualitative content analysis

Directed qualitative content analysis41 was used to identify the various decision-making matrices, each of which illustrates the involvement within the dyad and the final decision maker for both daily and formal care decisions. The matrices were based on predetermined categories of either shared decision making or the absence of shared decision making, and final decision maker. Shared decision making was described as the person living with dementia and the care partner both being included in the decision-making process and working as a team to make decisions about daily or formal care. Absence of shared decision making was when either member of the dyad decided alone. During analysis, an additional category of dyadic communication emerged, which reflected discussion between both members of the dyad with only one member making the decision. All categories were agreed upon by the first and last author.

I Poems

The creation of I Poems is a systematic way of working with interview data, by highlighting statements that begin with the pronoun “I,” as well as the verbiage that follows.42,43 Once identified, the Listening Guide44 approach was used, with both the first and last authors, conducting two “listenings,” the first, listening for the story plot, and the second focusing on the storyteller’s voice. Every first-person “I” phrase was identified and pulled, creating a new transcript that maintained the sequence in which these statements appeared in the transcripts. Each phrase became a single line in the I Poem. Next, these phrases were divided into stanzas, each grouping reflected either a shift in meaning, a change in the participanťs cadence, or a pause in their speech.44 This process was completed individually by the first and last authors, then agreed upon for consistency. The novel use of I Poems provide unique insights into the persons living with dementia’s perceived involvement in daily and formal care decision making.

Quantitative content analysis

Quantitative content analysis (word count) was used as one measure of the persons living with dementia’s contribution to the interview. The first author completed the word count. A percentage of the persons living with dementia’s words were calculated by dividing the persons living with dementia’s word frequency by the total word frequency of each entire dyadic interview.

Multimethod approach to analysis

Using a multimethod approach to analysis provided unique insights into daily and formal care decision-making patterns, while ensuring the voices of the persons living with dementia are not only heard but prioritized. Results are presented individually, then combined results are presented.

Rigor, credibility, and trustworthiness

Member checks were conducted with the African American dyads to confirm accuracy of their responses in the results. Dyadic vignette field notes were taken by the first author during each visit and expanded upon immediately after interviews.36,51,52 In addition, the first author maintained a reflective journal throughout the study. The journal recorded reactions to the dyad, emotional responses within and across interviews, awareness of assumptions regarding race and decision making in caregiving; and my role as an African American researcher.53 The data transcripts and analyses were evaluated during peer debriefings and disagreements that occurred with the coding of categories were discussed among authors (KBJ and MD) until there was 100% consensus. In addition, an audit trail of procedures and data analysis were maintained.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the fifteen dyads approached, five dyads participated in this study (5 persons living with dementia; 6 care partners). One dyad was ineligible, 4 refused, 1 was eligible but lost to follow up, and 3 were lost to follow up before screening. All persons living with dementia were women between the ages of 69 to 90+ years of age (M=81, SD=9). The persons living with dementia who were 90 years or older were all recorded as 90+ to protect identity. On average, MoCA scores were 20 with a range of 16 to 26. The level of cognitive impairment for the persons living with dementia ranged from mild cognitive impairment to late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Over half of the family care partners were adult children (67%; n=4) and were women (83%; n=5). The age of family care partners ranged from 38 to 78 years (M=57, SD=15). Refer to Table 2 for additional sample demographics.

Table 2.

Sample Demographics of African American Dementia Dyads

| Dyad | PLWD | Age | Gender | MoCA | Dementia Stage | Care Partner(s) | Age | Gender | Caregiving (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mother | 90+a | F | 11b | Severe | Daughter 1 | 70 | F | 22 |

| Daughter 2 | 78 | F | 22 | ||||||

| 2 | Mother | 90+a | F | 23 | Moderate | Son | 57 | M | 0.5 |

| 3 | Mother | 79 | F | 21 | Early | (Fictive kin) Daughter | 58 | F | 2 |

| 4 | Godmother | 77 | F | 16 | MCI | Goddaughter | 43 | F | 5 |

| 5 | Mother | 69 | F | 26 | MCI | Daughter | 38 | F | 10 |

Note.

Ages 90 years or older were all recorded as 90+ to protect identity.

Used the MoCA without visual elements, scored out of 22. Fictive kin= considered family but not related by blood or marriage; F= female;; M= male; MCI= mild cognitive impairment; MoCA= Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PLWD= person living with dementia.

Decision-making matrices

Decision-making involvement

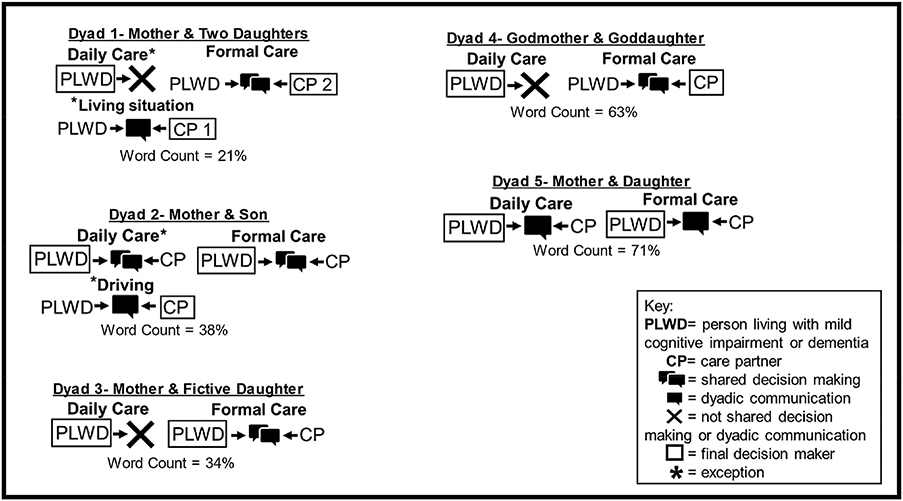

Dementia dyads were involved in daily and/or formal care decision making through shared decision making, absence of shared decision making, or dyadic communication (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Decision-Making Matrices of the African American Dementia Dyads

Note. Schematic drawing of the decision-making matrices of each African American dementia dyad in the study with exceptions.

Shared decision making was identified when both members of the dementia dyad described being included (from the person living with dementia) or including the person living with dementia (from care partner) in making decisions together and working as a team. Shared decision making was intentional by the care partner. Shared decision making was identified with daily care decisions in Dyad 2 and with formal care decisions in Dyads 1, 2, 3, and 4. One care partner described how shared decision making occurred within the dyad:

…I said, Mother, what do you want? And then she stresses, THIS is what I want. So, we started doing that piece, so when it gets, when she canť make the decision, ’cause her, ’cause her memory comes and goes, then we sit down and say, These are the options.

Dyadic communication, conversations between both members of the dyad with only one member deciding, was identified in just one dyad (Dyad 5) but was used for both daily and formal care decisions. In other dyads (Dyads 1, 2), dyadic communication was used infrequently for selected decision regarding the person living with dementia’s living situation (Dyad 1) and driving (Dyad 2), respectively.

The absence of shared decision making was exhibited in three dyads (Dyads 1, 3, & 4). In these dyads, daily care decisions were made solely by the person living with dementia. As one participant shared, she was adamant about daily care decisions being hers to make and expressed, “It’s mine.” In Dyad 1, daily care decisions were typically completed by the person living with dementia in the absence of shared decision making. However, as noted earlier, dyadic communication was used when deciding about her living situation.

Final decision maker

In each dyad, the person living with dementia and their care partner(s) were asked about who makes the final decision regarding both daily and formal care. The person living with dementia was the final decision maker for daily decisions across all dyads, regardless of their decision-making involvement; however, the final decision maker for formal care varied. In three dyads (Dyads 2, 3, & 5), the person living with dementia was the final decision maker for formal care decisions in the remaining dyads (Dyads 1 & 4), the care partner was the final decision maker. Of note, while the decision maker varied across the dyads, there was congruence within the dyads about who was the final decision maker. Also, of note was when exceptions in decision-making involvement were present, the person living with dementia in Dyad 1 agreed with the living arrangement and with her care partner being the final decision maker. In Dyad 2, the person living with dementia disagreed with the decision not to drive but agreed with the care partner being the final decision maker.

I Poems

As noted earlier, the I Poems are drawn entirely from the person living with dementia’s narratives. Selected stanzas from the I Poems regarding daily and formal care are included in Table 3.

Table 3.

I Poems- Selected Excerpts Supporting Daily and Formal Care Decision Types

| Daily Care | I Poem Excerpts |

|---|---|

| Shared Decision Making |

Mother of Dyad 2 I still have a say I still make the decisions I feel very comfortable with the decisions that I make I have no problem; they know how far to go I listen to what they want, what they need |

| Absence of Shared Decision Making |

Mother of Dyad 1 I ask can I have what I want I’ll get a chicken sandwich I can eat I say, what are we having for dessert? I say, okay give it to us Mother of Dyad 3 I get what I wanna get I don’t really like to be told, oh you can’t have this, and you can’t have that when it’s my money Godmother of Dyad 4 I don’t want to go I don’t even get up I need to get up I don’t have nothing to do I don’t want to get up I don’t want to put no clothes on I may not want to eat nothing I’m not going to do it I got this |

| Formal Care | |

| Shared Decision Making |

Mother of Dyad 1 I depend on her [Daughter 2] making decisions I just kind of went to pieces [when my husband died] I turned all my papers over to [Daughter 2] I said, do whatever you want to I just I say, okay, I will sign them I did read them, I say yes, but lots of time I won’t read them I just pretend I was reading I was just, I was just worn out Mother of Dyad 3 I had [DNR] on paper at the hospital it [says] that if I’m not gonna make it, don’t put me on no life support I’d be suffering and you should let me go I left it in her [POA] hands, because I know that she’ll do it and tell the rest of them to jump off Godmother of Dyad 4 I ask her [Goddaughter] something I might go ahead and do it anyway I may not agree |

| Dyadic Communication |

Mother of Dyad 5 I wanna know I can’t run from it, so don’t hide it from me, tell me what’s going on I let her [Daughter] know |

Quantitative content analysis

The quantitative content analysis included a word count to identify the balance of participation in the interview as an indirect assessment of the balance of participation in decision making. All persons living with dementia participated in the interviews; however, their level of participation (e.g., overall % of total word count) varied: Dyad 1=21%, Dyad 2=38%, Dyad 3=34%, Dyad 4=63%, and Dyad 5=71%.

Combined analysis

The final step was to combine the findings across the three approaches. The decision-making matrices highlight the subtle differences in the types of decision making, as well as identify the final decision maker within the dyads. The creation of I Poems infused the raw emotion and complexity of daily and formal care decision making from the perspective of each African American person living with dementia.18 The quantitative content analysis using a simple word count percentage reflected (in real time) the involvement of the person living with dementia in the conversation. While there were similarities among dyads’ decision making in terms of word count distribution and degree of shared decision making, the I Poems provided a unique picture from the perspective of the person living with dementia.

Discussion

To date, research focused on African American families and cultures have emphasized the role often bestowed to older adults within the family,33,54 which is often one of respect and leadership, but little is known about the effects of dementia on this respect or leadership or how it affects decision-making processes. Using a multimethod approach, our results highlight how daily and formal care decision-making involvement occurs within and across African American dementia dyads, while providing a firsthand account of the perspectives of African American persons living with dementia’s decision-making processes. In this study, I Poems were employed not only to retain the voice of African American persons living with dementia, but to call it out. This study is the first to include the use of I Poems to explore daily and formal care decision making within African American dementia dyads.

Formal care decision making has been studied in dementia care partners and dyads.5,25,28,30 These studies support the care partner being more involved in formal care and making final decisions;25,27,29,30,35 however, the majority of participants were non-Hispanic white persons living with dementia and/or their care partners. Our findings emphasize the potential variability between the formal-care decision making process of non-Hispanic white and African American dementia dyads. Within African American dementia dyads, formal-care decision making often requires additional input from other family members10 and health care providers.5 Yet, prior to this study, there has been little to no research on how formal care decisions within families are affected by dementia.

In this study, the decision-making matrices provide visual representations of the nuanced differences in daily and formal care decision-making processes and the final decision maker within these African American dementia dyads. Daily care decisions were predominantly not shared decisions, except within Dyad 1. This finding is in keeping with previous research that supports persons living with dementia making daily care decisions,34 as it supports their sense of personhood. In two instances, daily care decisions were made by the care partner after dyadic communication (i.e., Dyad 1 – living situation; Dyad 2 – driving), which were safety concerns. Safety concerns can be a major point of tension in dementia caregiving, and care partners often value safety needs of their persons living with dementia over the person living with dementia’s sense of personhood.28 In both dyads, the care partners had support from other family members and were knowledgeable about the dementia trajectory, which may have reinforced the care partners prioritizing the safety of the person living with dementia.55 Future research is needed to better understand the effects of prioritizing the person living with dementia’s safety over their autonomy in African American dementia dyads.

Formal-care decision making was predominantly shared within dementia dyads and the person living with dementia was the final decision maker. For example, both members of Dyad 4, shared their perspectives regarding formal care decision making. Sometimes that means making an appointment and other times the agreed decision is to wait and not move forward. While the care partner is the final decision maker, the formal care decision is agreed upon by both members of the dyad. In comparison, in Dyad 5, formal care decision making occurs through dyadic communication. The person living with dementia is the final decision maker; she makes the formal care decision and then informs her care partner. Our findings are contrary to previous research that supports persons living with dementia having limited involvement in decision making,19 which may reflect the limited participation of African American families.

The current study identified the prominent role of African American persons living with dementia in both daily and formal care decision making, which is contrary to previous research that points to care partners aa the final decision makers.30 In this study, the African American person living with dementia was integral to the decision-making process, in part because of the effort of their care partners. Practice and research focused on daily and formal care should be mindful of the potential need to acknowledge and include African American persons living with dementia in decision making throughout the dementia trajectory.56 For nursing and other healthcare providers, this understanding may be important when determining effective treatments and developing care plans for African American persons living with dementia. Shared decision making in patient/care partner dyadic caregiving research often refers to congruence of both members of the dyad. However, in patient/provider dyadic research, shared decision making refers to the congruent perspectives of the patient and provider. African American care partners look for input of healthcare providers when making formal care decisions.5 We suggest expanding the concept of shared decision making to include both dyadic perspectives, especially with African American persons living with dementia. Using this approach may improve planning for future daily and formal care needs. Although additional time may be needed for this shared decision making,10 it is worthwhile for improved health outcomes of both members of the dyad.

Limitations

There are limitations related to the sample. Our study sample size was small. There was only one male care partner, and none of person living with dementia were men. While the prevalence of care partners in general, as well as in the African American culture, is predominantly women, it is important to note there may be differences when either or each dyad member is a man. Each dyad had its own unique decision-making matrix. It is not known if other variations exist or if indeed these variations will hold with an increased, varied sample size. Finally, the sample was collected in the Pacific Northwest, introducing regional differences that may not transfer to other areas of the country. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to use I Poems to explore the decision-making involvement of African American persons living with dementia.

Conclusion

The current study identified several key aspects of daily and formal care decision making within African American dementia dyads such as the level of involvement (shared decision making, absence of shared decision making, and dyadic communication) of African American persons living with dementia and the final decision maker of these decision-making processes. We argue the importance of understanding the role of African American persons living with dementia in daily and formal care decision making is essential to support daily care planning and formal care use for African American persons living with dementia.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by awards to the primary author (K.B.) from the SAMHSA-ANA [1H79SM080386-01], Sigma Theta Tau, International Naomi Ballard Research Award, Jonas Foundation (Jonas Veterans Healthcare Scholar) and Oregon Health & Science School of Nursing (Dean’s Alumni Scholarship & Pierce Scholarship). This work was also supported through the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research [2T32NR012715 (K.B.)] and National Institute on Aging [K23AG065452 (F.E)]. The views expressed in written training materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services or the National Institutes of Health; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

None to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: The older population in the United States. United States Census Bureau;2014. P25–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Association. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2020;16(3):391–460. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinton L, Franz C, Friend J. Pathways to dementia diagnosis: evidence for cross-ethnic differences. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2004;18(3):134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukadam N, Cooper C, Livingston G. Improving access to dementia services for people from minority ethnic groups. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(4):409–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonds K, Lyons KS. Formal Service Use by African American Individuals With Dementia and Their Caregivers: An Integrative Review. Journal of gerontological nursing. 2018;44(6):33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuckerman IH, Ryder PT, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of dementia among Medicare beneficiaries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63(5):S328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin AL, Negash S, Hamilton R. Diversity and disparity in dementia: the impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2011;25(3):187–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayegh P, Knight BG. Cross-cultural differences in dementia: the Sociocultural Health Belief Model. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(4):517–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epps F, Skemp L, Specht JK. How Do We Promote Health?: From the Words of African American Older Adults With Dementia and Their Family Members. Research in gerontological nursing. 2016;9(6):278–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potter EC, Roberto KA, Brossoie N, Blieszner R. Decisions, Decisions. Res Aging. 2017;39(4):476–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menne HL, Tucke SS, Whitlatch CJ, Feinberg LF. Decision-making involvement scale for individuals with dementia and family caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(1):23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reamy AM, Kim K, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Understanding discrepancy in perceptions of values: Individuals with mild to moderate dementia and their family caregivers. Gerontologist. 2011;51(4):473–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samsi K, Manthorpe J. Everyday decision-making in dementia: findings from a longitudinal interview study of people with dementia and family carers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(6):949–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menne HL, Whitlatch CJ. Decision-making involvement of individuals with dementia. Gerontologist. 2007;47(6):810–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonds K, Whitlatch CJ, Song M, Lyons KS. Factors influencing quality of life in African-American dementia dyads. Aging & Mental Health. 2020:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menne HL, Judge KS, Whitlatch CJ. Predictors of quality of life for individuals with dementia: Implications for intervention. Dementia. 2009;8(4):543–560. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis R, Ziomkowski MK, Veltkamp A. Everyday Decision Making in Individuals with Early-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Research in gerontological nursing. 2017;10(5):240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitwood T. The experience of dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 1997;1(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, Lyons KS. Shared decision-making in dementia: A review of patient and family carer involvement. Dementia (London) 2016;15(5):1141–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonds K, Song M, Whitlatch CJ, Lyons KS, Kaye JA, Lee CS. Patterns of Dyadic Appraisal of Decision-Making Involvement of African American Persons Living with Dementia. Gerontologist. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moon H, Townsend AL, Dilworth-Anderson P, Whitlatch CJ. Predictors of Discrepancy Between Care Recipients With Mild-to-Moderate Dementia and Their Caregivers on Perceptions of the Care Recipients’ Quality of Life. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31(6):508–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon H, Townsend AL, Whitlatch CJ, Dilworth-Anderson P. Quality of Life for Dementia Caregiving Dyads: Effects of Incongruent Perceptions of Everyday Care and Values. Gerontologist. 2017;57(4):657–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Song Y. Formal and Informal Care. In: Gu D, Dupre ME, eds. Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brechling BG, Schneider CA. Preserving Autonomy in Early Stage Dementia. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1993;20(1–2):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirschman KB, Joyce CM, James BD, Xie SX, Karlawish JH. Do Alzheimer’s disease patients want to participate in a treatment decision, and would their caregivers let them? Gerontologist. 2005;45(3):381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taghizadeh Larsson A, Österholm JH. How are decisions on care services for people with dementia made and experienced? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis of recent empirical findings. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(11):1849–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirschman KB, Joyce CM, James BD, Xie SX, Casarett DJ, Karlawish JH. Would caregivers of Alzheimer disease patients involve their relative in a decision to use an AD-slowing medication? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(11):1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horton-Deutsch S, Twigg P, Evans R. Health care decision-making of persons with dementia. Dementia. 2007;6(1):105–120. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirschman KB, Xie SX, Feudtner C, Karlawish JH. How does an Alzheimer’s disease patienťs role in medical decision making change over time? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17(2):55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlawish JH, Casarett D, Propert KJ, James BD, Clark CM. Relationship between Alzheimer’s disease severity and patient participation in decisions about their medical care. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2002;15(2):68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dilworth-Anderson P, Gibson BE. The cultural influence of values, norms, meanings, and perceptions in understanding dementia in ethnic minorities. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2002;16(SUPPL. 2):S56–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Billingsley A. Black Families in White America. New York, New York: Touchstone Books; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindauer A, Harvath TA, Berry PH, Wros P. The meanings African American caregivers ascribe to dementia-related changes: The paradox of hanging on to loss. Gerontologist. 2016;56(4):733–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fetherstonhaugh D, Tarzia L, Nay R. Being central to decision making means I am still here!: the essence of decision making for people with dementia. Journal of aging studies. 2013;27(2):143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smebye KL, Kirkevold M, Engedal K. How do persons with dementia participate in decision making related to health and daily care? a multi-case study. BMC health services research. 2012;12:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in nursing & health. 2000;23(4):334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandelowski M. Whaťs in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in nursing & health. 2010;33(1):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan DL. Essentials of Dyadic Interviewing. Taylor & Francis; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kondracki NL, Wellman NS, Amundson DR. Content analysis: review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34(4):224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koelsch LE. I poems: Evoking self. Qualitative Psychology. 2015;2(1):96–107. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koelsch LE, Goldberg SG, Bennett E. “Am I Telling the Story Right?” Poetry, Community, and Trauma. The Qualitative Report. 2020;26(6):1540–1554. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilligan C, Spencer R, Weinberg MK, & Bertsch T. On the listening guide: A voice-centered relational method. In: Hesse-Biber SNL P, ed. Emergent Methods in Social Research. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dilworth-Anderson P, Pierre G, Hilliard TS. Social Justice, Health Disparities, and Culture in the Care of the Elderly. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. 2012;40(1):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldstein FC, Ashley AV, Miller E, Alexeeva O, Zanders L, King V. Validity of the montreal cognitive assessment as a screen for mild cognitive impairment and dementia in African Americans. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2014;27(3):199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 1982;140:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eisikovits Z, Koren C. Approaches to and outcomes of dyadic interview analysis. Qualitative health research. 2010;20(12):1642–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solomon DN, Hansen L, Baggs JG. Iťs all about the relationship: Cognitively intact mother-daughter care dyads in hospice at home. Gerontologist. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation. 1986;1986(30):73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC medical research methodology. 2009;9:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tufford L, Newman P. Bracketing in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Social Work. 2010;11(1):80–96. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams SW, Dilworth-Anderson P. Systems of social support in families who care for dependent African American elders. Gerontologist. 2002;42(2):224–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lach HW, Chang YP. Caregiver perspectives on safety in home dementia care. Western journal of nursing research. 2007;29(8):993–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navin M, Wasserman JA, Stahl D, Tomlinson T. The capacity to designate a surrogate is distinct from decisional capacity: normative and empirical considerations. Journal of medical ethics. 2021:medethics-2020–107078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]