Abstract

Our objective was to estimate the prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) eligibility, characterize self-perceived and quantified human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk, and assess PrEP knowledge and receptiveness of initiating PrEP among emergency department (ED) patients. We performed an IRB-approved cross-sectional study from two urban EDs. Patients were eligible if ≥18 years of age and not known to have HIV. Research staff obtained verbal consent and used a structured 29-item instrument to assess HIV risk, PrEP eligibility based on 2017 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, and general PrEP knowledge among unselected and enriched patient samples, the latter informed by the Denver HIV Risk Score (DHRS). We enrolled 1002 patients with a median age of 39 years; 54.8% were male, 30.9% White/non-Hispanic, 29.5% Black/non-Hispanic, and 22.5% Hispanic. In the full cohort, 119 [11.9%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 9.9–14.0%] were PrEP eligible, and among the unselected cohort, 36 (7.1%, 95% CI: 5.1–9.8%) were PrEP eligible. Using the DHRS, 100 patients were considered “high risk” with 32 (32.0%) reporting zero perceived risk. Correlation between the DHRS and self-perceived HIV risk was low (r = 0.13). Of the full cohort, 203 (20.3%) had heard of PrEP, and of these, 33 (16.3%) were PrEP eligible with 25 (75.8%) willing to start PrEP immediately. Yet, of the 119 patients who were PrEP eligible, only 34 (28.6%) had heard of PrEP. In summary, among a heterogeneous ED population, there was discordance in self-perceived and quantified HIV risk. HIV PrEP eligibility was ∼7% with the highest eligibility among those identified as DHRS “high risk.” A significant opportunity exists to identify and initiate PrEP among ED patients.

Keywords: HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis, prevalence, HIV risk, prevention, emergency department, identification, Denver HIV Risk Score

Introduction

In the United States, ∼1.2 million individuals are living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and about 14% remain undiagnosed.1 While diagnosis and treatment for those with HIV remain an important public health priority,2,3 prevention of transmission is also a critical focus.4 Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV is highly effective and has become a mainstay of primary HIV prevention such that the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy has prioritized expanded access to PrEP for those most at risk of acquiring HIV.5

Emergency departments (EDs) provide care to large numbers of underserved and socially vulnerable patients with substantial HIV risk. For many of these patients, the ED serves as their only source of contact with the health care system.6 While EDs provide an important opportunity to identify patients at risk for HIV, the vast majority of work in this area has focused on diagnosis rather than primary prevention.7–12 As such, EDs may serve as an untapped opportunity to identify patients eligible for PrEP (Table 1), while also facilitating PrEP initiation.

Table 1.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Eligibility Criteria

| In the previous 6 months |

| Sex with an HIV-positive partner |

| Sex with a partner who injects drugs and shares injection equipment |

| High-risk non-monogamous MSM, defined as condomless anal intercourse |

| High-risk non-monogamous heterosexual sex, defined as infrequent condom use with vaginal or anal intercourse and a partner of unknown HIV status and at substantial risk of HIV (i.e., IDU or bisexual male) |

| Bacterial STI |

| Commercial sex work |

| IDU with shared equipment |

Adapted from guidelines from the CDC.21

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

As the number and proportion of patients with undiagnosed HIV declines, HIV screening and prevention strategies will need to evolve. Of those identified as highest risk, the vast majority (>95%) test negative for HIV,13,14 these individuals are likely most susceptible to acquiring the virus and, thus, most likely to benefit from PrEP. While risk characteristics and HIV risk assessment has been studied in ED settings,13–16 limited research has been performed to characterize PrEP eligibility among ED patients.17–19

The goals of this study were to: (1) estimate the prevalence of PrEP eligibility among representative samples of ED patients; (2) characterize self-perceived and quantified HIV risk, using a validated HIV risk score,14 among PrEP-eligible patients; and (3) estimate PrEP knowledge and receptiveness among ED patients. In doing so, this study would provide a critical foundation for how best to identify ED patients who are eligible for PrEP.

Methods

Study design

We performed a prospective observational study using a cross-sectional survey design at two acute care medical centers in the United States. This study was approved by each institution's local Institutional Review Board, all participants provided verbal informed consent before participation, and no incentives were provided to participants. This study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement.20

Setting

We performed this study in the EDs at Denver Health Medical Center in Denver, Colorado and Highland Hospital in Oakland, California. Both institutions are high-volume, urban, safety-net medical centers and Level 1 trauma centers with a combined annual ED census of >150,000 visits. Both institutions serve large, heterogeneous populations that are predominantly socioeconomically disadvantaged and with high proportions of racial/ethnic minorities.

Population and sampling

Patients ≥18 years of age were eligible for inclusion if not known to be or self-identified as living with HIV and able to provide consent and participate in a structured survey during their ED stay. Patients were excluded if they were unable to consent, acutely ill, or clinically unstable as determined by their ED provider, known to already be living with HIV, prisoners, or had already participated in this study.

During dedicated enrollment hours that varied from 7 a.m. through 2 a.m., 7 days a week, trained research assistants screened ED patients for participation. Participants from Highland Hospital were approached in an unselected manner in an effort to generate a study sample that reflected an unenriched, general ED population. However, recognizing the importance of including individuals across the spectrum of HIV risk and specifically ensuring sufficient number of participants with higher HIV risk, enriched sampling occurred at Denver Health Medical Center. Research assistants from Denver Health Medical Center approached patients in both unselected and selected manners, the former based on eligibility criteria alone, and the latter based on eligibility criteria among patients identified as being at increased risk for HIV using a Denver HIV Risk Score (DHRS) ≥40 from an embedded HIV screening program in the ED.14 All potentially eligible patients were approached during enrollment hours.

Survey instrument development

A 29-item closed-response survey instrument was designed by our team for use in this study (Supplementary Fig. S1). Development of the instrument and assessment of face validity was performed by a group of investigators with expertise in emergency medicine, infectious diseases, epidemiology, HIV prevention, PrEP, and public health. The survey was developed in an iterative manner, targeting appropriate literary level for our populations, and piloted with revisions before being finalized.

The instrument included: (1) patient demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity); highest education level; past HIV testing; whether the patient endorsed having HIV (if the patient indicated he or she was living with HIV the survey was stopped); (2) self-perceived HIV risk using a 100 mm line anchored with “no risk for getting HIV” and “very high risk for getting HIV; (3) history of injection drug use (IDU) and, if so, whether the patient ever shared equipment; (4) sexual practices, including sexual orientation, number of sexual partners, type of sex (i.e., vaginal, anal, oral), condom use, and if so, frequency of use, knowledge about sexual partners' sexual practices, HIV status, and injection drug history; (5) past diagnosis or treatment for a bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) (i.e., chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis); and (6) general knowledge and understanding of PrEP.

Data collection

Between May 28, 2019 and October 25, 2019, research assistants trained in the conduct and administration of the survey collected all data for this study using electronic tablets linked to REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). Surveys were performed in person during convenience hours in private settings during the ED visit.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was PrEP eligibility, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),21 which specifically included any of the following: (1) sex with an HIV-positive partner; (2) sex with a partner who injects drugs and shares equipment; (3) high-risk non-monogamous men who have sex with men (MSM); (4) high-risk high risk non-monogamous heterosexual sex; (5) recent bacterial STI; (6) commercial sex work; or (7) IDU with shared equipment (Table 1).

Other outcomes included quantified HIV risk, as measured by the DHRS, and self-perceived HIV risk. The DHRS is a validated quantitative risk instrument that includes age, sex, race/ethnicity, sex with a male, IDU, and past HIV testing; each variable includes a unique score that, when combined into a composite score, characterizes a patient's HIV risk (Supplementary Table S1). The DHRS ranges from −4 to 73 and has been categorized into the following five risk groups: very low risk (−4 to 19); low risk (20–29); moderate risk (30–39); high risk (40–49); and very high risk (50–73) (Supplementary Fig. S2).14

Data management and statistical analyses

All data were electronically captured and stored in REDCap at Denver Health and transferred into native SAS format for analyses. Analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide Version 7.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata Version 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics for continuous data are reported as mean with standard deviations (SDs) for normally distributed data and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical data are reported as proportions or percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Absolute differences with 95% CIs were used to compare variables by PrEP eligibility. Chi-square test was used to compare percentages of those determined to be PrEP eligible across DHRS categories, and Spearman rank correlation was used to compare quantified versus self-perceived HIV risk as continuous variables. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Sample size

Given the observational nature of this study, no formal power calculation was performed. However, in an effort to include both a large, heterogeneous sample and a sample representative of an ED population with balanced enrollment from both sites, this study planned to enroll 500 participants from each site for a total of 1000 participants. Further, as part of our approach to enrich the sample with participants at increased risk for HIV, we planned to include a minimum of 100 participants with a DHRS ≥40, which represents “high risk,” to provide sufficient precision for estimates of PrEP eligibility, while also providing sufficient precision for HIV risk subgroups.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

During the 5-month study period, 1002 patients were enrolled (unenriched = 504 from Highland Hospital and enriched = 498 from Denver Health Medical Center) with a median age of 39 (IQR: 29–54; range: 18–87) years; and, of these, 54.8% were male, 30.9% White/non-Hispanic, 29.5% Black/non-Hispanic, 22.5% Hispanic, 50.1% had completed some college or higher, and 78.1% had previously been tested for HIV.

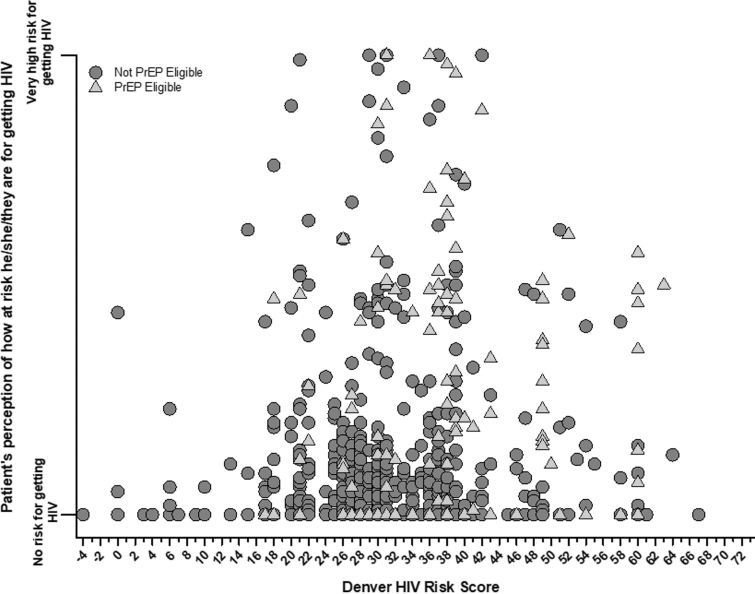

HIV risk

Of all patients, the median DHRS was 31 (IQR: 27–36; range: −4 to 67) with 64 (6.4%) considered very low risk (DHRS <20), 335 (33.4%) low risk (DHRS 20–29), 503 (50.2%) moderate risk (DHRS 30–39), 63 (6.3%) high risk (DHRS 40–49), and 37 (3.7%) very high risk (DHRS ≥50). Of the 1002 total patients, 977 (97.5%) completed self-perceived HIV assessments with a median perceived risk of 0 (IQR: 0–11; range: 0–100) and a mean perceived risk of 10 (SD: 19). Of the 977 patients, 532 (54.5%) perceived themselves as having zero risk for acquiring HIV, and 200 (20.5%) perceived themselves as being low risk (defined as reported risk between 1% and 10% of acquiring HIV) (Fig. 1). Correlation between the DHRS and perceived probability of acquiring HIV was low (Spearman r = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.07–0.19).

FIG. 1.

Self-perceived versus quantified HIV risk (as defined by the DHRS), stratified by PrEP eligibility among ED patients from Denver, Colorado and Oakland, California (n = 1002). DHRS ranges from −4 (lowest risk) to 73 (highest risk). DHRS, Denver HIV Risk Score; ED, emergency department; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

HIV risk characteristics and PrEP eligibility

Overall, of the 1002 patients, 119 (11.9%, 95% CI: 9.9–14.0%) were PrEP eligible. Of the 504 patients included from Highland Hospital, 36 (7.1%, 95% CI: 5.1–9.8%) were PrEP eligible, whereas of the 498 patients included from Denver Health Medical Center, which included enriched sampling for individuals with higher DHRS scores, 83 (16.7%, 95% CI: 13.5–20.2%) were PrEP eligible.

Table 2 shows patient demographic and risk profile characteristics by PrEP eligibility. Of the 119 PrEP-eligible patients, 46 (38.7%, 95% CI: 29.9–48.0%) perceived themselves as having low risk of acquiring HIV and 35 (29.4%, 95% CI: 21.4–38.5%) perceived themselves as having zero risk of acquiring HIV. Of the 119 PrEP-eligible patients, 74.8% endorsed some form of high-risk sexual behavior, 29.4% a recent bacterial STI, 18.5% IDU and shared equipment, and 13.4% commercial sex work (Table 3). Finally, PrEP eligibility increased significantly across DHRS categories: among the 399 patients determined to be low risk, 24 (6.0%, 95% CI: 3.9–8.8%) were PrEP eligible; among the 503 patients determined to be moderate risk, 61 (12.1%, 95% CI: 9.4–15.3%) were PrEP eligible; and among the 100 patients determined to be high risk, 34 (34.0%, 95% CI: 24.8–44.2%) (p < 0.001) were PrEP eligible (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Eligibility, Denver Health Medical Center, Denver, Colorado (n = 498), and Highland Hospital, Oakland, California (n = 504)

| PrEP eligiblea |

Difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

No |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Total (n = 1002) | 119 (12) | 883 (88) | |

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 34 (27–44) | 41 (29–55) | −7 (−8 to −3) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 39 (33) | 398 (45) | −12 (−3 to −21) |

| Male | 76 (64) | 473 (54) | 10 (1 to 20) |

| Transgender MTF | 1 (0.8) | 4 (0.5) | 0.3 (−1 to 2) |

| Transgender FTM | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | −0.2 (−1 to 0.1) |

| Nonbinary | 3 (3) | 4 (0.5) | 2.5 (−1 to 5) |

| Unknown/not answered | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | −0.2 (−1 to 0.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| African | 0 (0) | 10 (1) | −1 (−2 to −0.4) |

| American Indian, Alaskan Native | 4 (3) | 17 (2) | 1 (−2 to 5) |

| Asian | 3 (3) | 30 (3) | 0 (−4 to 2) |

| Black/African American | 27 (23) | 269 (31) | −8 (−16 to 0.3) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 14 (12) | 211 (24) | −12 (−19 to −6) |

| Multiple/mixed | 11 (9) | 77 (9) | 0 (−5 to 6) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (0.8) | 3 (0.3) | 0.5 (−2 to 2) |

| White | 59 (50) | 251 (28) | 22 (12 to 31) |

| Unknown/not answered | 0 (0) | 15 (2) | −2 (−3 to −0.1) |

| Education | |||

| Did not complete high school | 24 (20) | 110 (13) | 7 (0.2 to 15) |

| High school, GED | 32 (27) | 313 (36) | −9 (−17 to 0) |

| Trade school | 4 (4) | 14 (2) | 2 (−2 to 5) |

| Some college | 33 (28) | 232 (26) | 2 (−7 to 10) |

| College degree or higher | 26 (22) | 211 (24) | −2 (−10 to 6) |

| Unknown/not answered | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) |

| HIV risk | |||

| Previously tested for HIV | 107 (90) | 676 (77) | 13 (7 to 19) |

| Self-perceived HIV risk (mean, SD) | 27 (28) | 8 (17) | 19 (17 to 19) |

| Quantified HIV riskb (median, IQR) | 37 (30–41) | 30 (26–36) | 7 (4 to 8) |

PrEP eligibility defined in Table 1.

Defined by the DHRS.

CI, confidence interval; DHRS, Denver HIV Risk Score; FTM, female-to-male; GED, general education development; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; MTF, male-to-female; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SD, standard deviation; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Table 3.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Risk Characteristics and HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Eligibility, Denver Health Medical Center, Denver, Colorado (n = 498), and Highland Hospital, Oakland, California (n = 504)

| PrEP eligiblea |

Difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

No |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Total (n = 1002) | 119 (12) | 883 (88) | |

| IDU | |||

| Ever | 43 (36) | 99 (11) | 25 (16 to 34) |

| In prior 6 months | 29 (24) | 28 (3) | 21 (13 to 29) |

| Shared equipmenta | 22 (19) | 0 (0) | 19 (12 to 26) |

| Sexual practicesb | |||

| No sex | 11 (9) | 264 (30) | −21 (−27 to −15) |

| Monogamous sex | 10 (8) | 482 (55) | −47 (−52 to −40) |

| Non-monogamous sex | 98 (82) | 133 (15) | 67 (60 to 75) |

| Multiple sex partners | 74 (62) | 85 (10) | 52 (44 to 62) |

| Always uses condoms | 22 (19) | 59 (7) | 12 (5 to 19) |

| High-risk sexa | 89 (75) | 0 (0) | 75 (67 to 83) |

| High-risk non-monogamous hetero sexa | 58 (49) | 0 (0) | 49 (40 to 58) |

| High-risk non-monogamous MSMa | 16 (13) | 0 (0) | 13 (7 to 20) |

| High-risk monogamous sexa | 7 (6) | 0 (0) | 6 (2 to 10) |

| Sex with partner living with HIVa | 8 (7) | 0 (0) | 7 (2 to 11) |

| Sex worka | 16 (13) | 0 (0) | 13 (7 to 20) |

| STIa | 35 (29) | 0 (0) | 29 (21 to 38) |

| Self-Perceived HIV Risk | |||

| Zero risk | 35 (29) | 497 (56) | −27 (−36 to −18) |

| Low risk | 46 (39) | 711 (81) | −42 (−51 to −33) |

| Quantified HIV riskc | |||

| Very low risk (DHRS <20) | 4 (3) | 60 (7) | −4 (−7 to 0.2) |

| Low risk (DHRS 20–29) | 20 (17) | 315 (36) | −19 (−26 to −11) |

| Moderate risk (DHRS 30–39) | 61 (51) | 442 (50) | 1 (−8 to 11) |

| High risk (DHRS 40–49) | 20 (17) | 43 (5) | 12 (5 to 19) |

| Very high risk (DHRS ≥50) | 14 (12) | 23 (3) | 9 (3 to 15) |

PrEP eligibility defined in Table 1.

“No sex” indicates current abstinence from sexual intercourse; “monogamous” indicates current monogamous sexual relationship; “non-monogamous” indicates current sexual relationship with less than one partner; “no sex,” “monogamous” and “non-monogamous” are mutually exclusive; “multiple sex partners” indicates less than one sex partner in the preceding 6 months; “high-risk sex” indicates those currently having (1) “high-risk non-monogamous hetero sex” (female or transgender female-to-male who has sex with a male who participates in vaginal or anal intercourse without condom use with partners with unknown HIV status or who inject drugs and share injection equipment or unknown if they inject drugs and share injection equipment or sex with MSM or unknown MSM, or male or transgender male-to-female who has sex with a female who participates in vaginal or anal intercourse without condom use with partners with unknown HIV status or who inject drugs and share injection equipment or unknown if they inject drugs and share injection equipment); (2) high risk non-monogamous MSM (male or transgender male-to-female who has sex with another male who participates in insertive or receptive anal intercourse without condom use); (3) “high risk monogamous sex” (partner with HIV or who injects drugs and shares injection equipment); (4) sex with known HIV-infected partner.

Defined by the DHRS.

CI, confidence interval; DHRS, Denver HIV Risk Score; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; IQR, interquartile range; MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SD, standard deviation; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

FIG. 2.

Self-perceived versus quantified HIV risk (as defined and categorized into five distinct risk groups using the DHRS), stratified by PrEP eligibility among ED patients from Denver, Colorado and Oakland, California (n = 1002). DHRS <20 = very low risk; DHRS 20–29 = low risk; DHRS 30–39 = moderate risk; DHRS 40–49 = high risk; and DHRS ≥50 = very high risk. DHRS, Denver HIV Risk Score; ED, emergency department; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

PrEP knowledge

Of the 1002 patients, 203 (20.3%) had knowledge of PrEP, and of these, 96 (47.3%) were willing to initiate PrEP immediately, if eligible. Of the 203 patients with prior knowledge of PrEP, 33 (16.3%) were PrEP eligible, and of these, 25 (75.8%, 95% CI: 57.7–88.9%) indicated they would be willing to start PrEP immediately, 18 (8.9%) had sexual partners who were currently using PrEP, and 11 (5.4%) were themselves currently using PrEP. Of the 192 patients who were not currently using PrEP, 108 (56.3%, 95% CI: 48.7–63.1%) indicated they would be willing to talk to someone in the ED about PrEP and 96 (50.0%, 95% CI: 42.5–57.0%) indicated they would be willing to start PrEP immediately, if determined to be eligible for PrEP. Yet, of the 119 patients who were PrEP eligible, only 34 (28.6%) had knowledge of PrEP.

Discussion

While HIV PrEP is an effective and important primary preventive intervention,22–26 to date, very little research has been performed to understand PrEP eligibility among ED patients. Although the first PrEP regimen was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012, delivery of this intervention has lagged.27 Our study, which included prospective enrollment of large, heterogeneous ED populations from two safety-net hospitals, demonstrated a relatively high prevalence of PrEP eligibility, ranging from 7% to 17%. Among those included using an unselected sampling frame, PrEP eligibility was estimated at 7%, and with a lower 95% confidence limit of 5%; as such, our results demonstrate that at least one in 20 ED patients is likely eligible for PrEP.

Although participants who were PrEP eligible had higher self-perceived and quantified HIV risk, our study further demonstrates a high degree of discordance between perceived and quantified HIV risk, including poor correlation between the two. A large proportion of patients consider themselves at low risk for HIV despite having moderate or high-risk scores, and ∼40% of PrEP-eligible patients perceived themselves at low risk. Additionally, prior reports have indicated that certain subpopulations (e.g., Black MSM and women) may not be easily identified due either to the knowledge of risk or varying sensitivities of PrEP eligibility guidelines.28,29 Finally, a large majority of patients had not heard of PrEP, but over half of those who were familiar with PrEP were willing to talk to a care provider about PrEP and nearly half of those were willing to initiate PrEP immediately if determined to be eligible. Moreover, of those determined retrospectively to be PrEP eligible, a large proportion indicated they would be willing to initiate PrEP immediately, highlighting the opportunity for ED-based PrEP information and educational initiatives, and interventions.

EDs not only serve as an important clinical site for identification of individuals with HIV, but also for those at risk of acquiring HIV, the same individuals who may benefit from PrEP. Unfortunately very little evaluation of PrEP implementation has been performed from an ED perspective,16–18,30 and a recent critical review of PrEP implementation in the United States reported no evaluation of PrEP implementation in ED setting.27 To our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically assess PrEP eligibility and patient knowledge of PrEP, and to do so in the context of perceived and quantified HIV risk, among unselected patients who present for care to the ED. Diagnosis of HIV and viral suppression are critical for reducing transmission, and those with undiagnosed HIV or those who are not virally suppressed contribute to most transmissions annually.

Our results provide a strong basis for developing systems to identify ED patients at risk for HIV. This is particularly important in settings where there are high proportions of patients without primary care, where PrEP may be initiated, or in instances where the population is at a higher risk. In addition to PrEP initiation, a significant opportunity exists for the implementation of services to inform and educate patients, especially given the relatively high prevalence of PrEP eligibility in conjunction with a relatively low prevalence of PrEP knowledge, while also working to mitigate barriers for PrEP initiation among marginalized populations (e.g., youth, racial/ethnic minorities, MSM). EDs may also consider comprehensive HIV harm reduction strategies for eligible patients, which may include condoms, sterile syringes for patients who inject drugs, and integration of substance use treatment or case management strategies when indicated.

Recently, Ridgway et al. published a study to help understand differences in PrEP knowledge and risk behavior among men and women who tested negative for HIV in an ED in Chicago, Illinois.18 Inclusion of 702 patients who completed HIV prevention counseling, either in the ED or by phone after the ED visit, demonstrated similar discordance in self-perceived risk when compared with actual endorsed risk behaviors, the latter based on PrEP eligibility criteria put forth by the CDC.21 Moreover, the investigators reported a relatively large PrEP-eligible proportion (37%). Unfortunately, the population included a largely selected group (only 13% surveyed of 5317 who tested negative for HIV during their ED visits, and only 30% of those contacted for HIV prevention counseling), and consisted predominantly of Black/African American (91%) and female (72%) patients, making it difficult to generalize their findings.

Kulie et al. also recently reported a study from two EDs in Washington DC, describing research assistants performing targeted screening of patients who presented with chief complaints related to HIV risk.19 Of the 410 participants, the majority were Black and/or heterosexual females with PrEP eligibility reported in 20%, driven principally by condomless sex with a person of unknown HIV status. Also, similar to our results, a low proportion had heard of PrEP. The results of this study support the use of staff working in parallel to clinical staff in the ED (in this case, research assistants), which limits our ability to extrapolate these findings to an ED that does not have this resource. Although use of a computer-assisted survey may have mitigated challenges in assessing risk, broader adoption of HIV prevention efforts in EDs, including identification and initiation of PrEP, will likely require development of systems that allow for an approach that is more integrated into routine emergency care.

Given the growth of ED-based HIV screening over the past two decades and the declining numbers of individuals with undiagnosed HIV, implementation of strategies for identification of those eligible for PrEP and PrEP initiation in the ED is likely a critical next step in furthering HIV prevention in clinical settings with unscheduled, episodic care. Extending HIV screening to include PrEP screening, and PrEP initiation for those identified as PrEP eligible, will provide an opportunity to further focus prevention efforts on individuals who seek care in ED settings, who may not have access to health care otherwise, and who are at increased risk for HIV. Recognizing challenges with PrEP uptake, development of standardized procedures (e.g., automated order sets, same-day PrEP initiation,31 standardized and facilitated refers into prevention and care settings, use of designated health educators or “preventionists,” etc.) will likely be required to optimize these efforts in EDs.

It is insufficient to rely on self-perceived HIV risk to drive identification of patient who may be PrEP eligible given the strong discordance in self-perceived versus quantified HIV risk, and the relatively low general knowledge about PrEP among ED patients. Given the specificity of identifying those eligible for PrEP, use of the DHRS alone would be insufficient, and use of a different DHRS threshold would likely be needed to maximize sensitivity. However, identification of patients eligible for PrEP will likely require an objective approach to targeted PrEP screening,19 one that does not rely on a patient's perception of risk to drive discussion about PrEP, but one, for example, where use of the DHRS as a first-step screen followed by more PrEP-specific questions to efficiently identify PrEP-eligible patients occurs. To our knowledge, formal PrEP screening in an ED environment has been limited to the early stage studies by Ridgway et al. and Kulie et al.18,19 Additional work is required to understand the sensitivity and specificity of the DHRS, and other potential tools, as they may inform PrEP strategies in ED settings.

An important limitation of this study included the possibility of selection and response biases. Patients were approached and provided verbal consent to participate, and although a large sample was obtained from two distinct institutions that provide care to relatively heterogeneous populations with diverse demographic and HIV risk characteristics, the final study sample represented a convenience sample. It is also possible that certain patients specifically did not participate, did not understand HIV risk, or misrepresented HIV risk, while other at-risk populations (e.g., prisoners, youth) were not included or sparsely represented (e.g., Black MSM). While future research will be required to better understand such populations and how best to identify, initiate, and engage them in PrEP care, if reporting bias did occur, it is likely the prevalence of PrEP eligibility was biased toward the null, suggesting that our reported prevalence may have been an underestimation. In an effort to minimize bias, research assistants had experience with and were specifically trained in conducting sensitive interviews, and all interviews were performed after consent and in the privacy of the patients' rooms. Further, although the survey was developed de novo for this study, it was designed using a group of content and methodologic experts, and piloted to optimize validity and completion; we also used electronic data capture methods to ensure high-quality data collection. Further, the use of the DHRS as a tool to quantify HIV risk may have been limited in that it was originally developed and validated to identify individual point-in-time risk and not necessarily future risk. While the DHRS may not be a perfect assessment of risk, it has been extensively validated using a national cohort of individuals tested for HIV, and has demonstrated strong association with HIV risk. Finally, this study may suffer from lack of generalizability in that it was conducted at two sites, both of which are considered safety-net institutions, and that serve a predominantly minority population; as such, results may not generalize to all EDs.

In summary, among a heterogeneous, predominantly minority ED population, there was significant discordance and variation between self-perceived and quantified HIV risk. Overall HIV PrEP eligibility was ∼7% with the highest eligibility (34%) among the subgroup of those identified as DHRS “high risk.” A significant opportunity exists to identify and initiate PrEP among ED patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following individuals for their assistance in various parts of this project: Alicia Cupelo, MSW (Denver Health); Aaron Graves, MS (Denver Health); Clay Hoffman, BS (Denver Health); Scott LeBeau, MS (Denver Health); Katherine Ling, BA (Denver Health); Taylor McCormick, MD, MS (Denver Health); Rishi Patel, BS (Alameda Health System); Alex Randazzo, BA (Alameda Health System); Carly Russell, MS (Alameda Health System); Stacy Trent, MD, MPH (Denver Health); and Tamara Todorovic, MPH (Alameda Health System). None of the individuals received compensation for their work on this project.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: for the HIV PrEP-ED Investigators

Authors' Contributions

J.S.H. and D.A.E.W. conceived and designed the study, and supervised conduct and data collection; J.S.H., D.A.E.W., S.E.R., K.K., E.H., and E.A. drafted and revised the survey instrument; C.L., S.G., and K.B. performed recruitment of patients and data collection; J.S.H. and E.H. performed analyses; J.S.H. drafted the article and all authors contributed substantially to its revisions. J.S.H. takes responsibility for the article as a whole.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

J.S.H. was supported, in part, by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA042982), and the CDC (R01CE003006); D.A.E.W. was supported, in part, by NIDA (R01DA049282), and Gilead Sciences, Inc.; S.E.R. was supported, in part, by NIDA (R01DA042982); and E.A. was supported by Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS: Basic Statistics. 2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html (Last accessed February15, 2020).

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ending the HIV Epidemic. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/default.html (Last accessed February15, 2020).

- 3. Hoover KW, Huang YA, Tanner ML, et al. HIV testing trends at visits to physician offices, community health centers, and emergency departments—United States, 2009–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:776–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chou R, Evans C, Hoverman A, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2019;321:2214–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Office of HIV/AIDS Strategy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020. Available at: files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/nhas-update.pdf (Last accessed November20, 2020).

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017. Emergency Department Summary Tables. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf (Last accessed November20, 2020)

- 7. Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Conroy AA, et al. Routine opt-out rapid HIV screening and detection of HIV infection in emergency department patients. JAMA 2010;304:284–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haukoos JS, Lyons MS, Rothman RE. The evolving landscape of HIV screening in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2018;72:54–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haukoos JS, Lyons MS, White DA, Hsieh YH, Rothman RE. Acute HIV infection and implications of fourth-generation HIV screening in emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64:547–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White DA, Scribner AN, Vahidnia F, et al. HIV screening in an urban emergency department: Comparison of screening using an opt-in versus an opt-out approach. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58(Suppl. 1):S89–S95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haukoos JS. The impact of nontargeted HIV screening in emergency departments and the ongoing need for targeted strategies. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:20–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Montoy JCC, Dow WH, Kaplan BC. Patient choice in opt-in, active choice, and opt-out HIV screening: Randomized clinical trial. BMJ 2016;352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Bender B, et al. Comparison of enhanced targeted rapid HIV screening using the Denver HIV risk score to nontargeted rapid HIV screening in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2013;61:353–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Bucossi MM, et al. Validation of a quantitative HIV risk prediction tool using a national HIV testing cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68:599–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haukoos JS, Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Derivation and validation of the Denver Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) risk score for targeted HIV screening. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175:838–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lockard A, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, et al. Constrasting self-perceived need and guideline-based indication for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among young, black men who have sex with men offereed pre-exposure prophylaxis in Atlanta, Georgia. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2019;33:112–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ridgway J, Almirol E, Schmitt J, et al. Exploring gender differences in PrEP interest among individuals testing HIV negative in an urban emergency department. AIDS Educ Prev 2018;30:382–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ridgway JP, Almirol EA, Bender A, et al. Which patients in the emergency department should receive preexposure prophylaxis? Implementation of a predictive analytics approach. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018;32:202–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kulie P, Castel AD, Zheng Z, et al. Targeted screening for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis eligibility in two emergency departments in Washington, DC. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2020;34:516–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Public Health Service: Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States -2017 update: A clinical practice guideline. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2017.pdf (Last accessed November20, 2020).

- 22. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:399–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:2083–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2587–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grohskopf LA, Chillag KL, Gvetadze R, et al. Randomized trial of clinical safety of daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2012;367:423–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mayer KH, Chan PA, R RP, Flash CA, Krakower DS. Evolving models and ongoing challenges for HIV preexposure prophylaxis implementation in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77:119–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lancki N, Almirol E, Alon L, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis guidelines have low sensitivity for identifying seroconverters in a sample of young Black MSM in Chicago. AIDS 2018;32:383–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Calabrese SK, Willie TC, Galvap RW, et al. Curreent US guidelines for prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophlaxis (PrEP) disqualify many women who are at risk and motivated to use PrEP. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019;81:395–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moore KL Jr., Dell S, Oliva MK, et al. Do confidentiality concerns impact pre-exposure prophylaxis willingness in emergency department adolescents and young adults? Am J Emerg Med 2019;37:1206–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kamis KF, Marx GE, Scott KA, et al. Same-day HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) initiation during drop-in sexually transmitted diseases clinic appointments is a highly acceptable, feasible, and safe model that engages individuals at risk for HIV into PrEP care. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:ofz310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.