Abstract

Whereas attachment dimensions (i.e., anxiety and avoidance) are generally associated with lower levels of relationship evaluations (e.g., satisfaction, commitment), research has not yet fully incorporated how partner attachment is related to these evaluations, nor how dyadic patterns (actor × partner attachment interactions) are associated with evaluations. Across two dyadic studies (N = 185, 123 dyads), we examine how actor, partner, and actor × partner interactions of attachment anxiety and avoidance are associated with reports of trust, satisfaction, and commitment. Results generally revealed that actor effects of attachment anxiety on lower relationship evaluations were weaker when partners were more anxious and stronger when partners were more avoidant. Moreover, actor effects of attachment avoidance on lower trust and satisfaction were stronger when partners were more anxious. Finally, own avoidance was more strongly negatively related to commitment in the presence of a more avoidant partner. These results suggest that the combination of attachment within relationships is important to consider for both close relationships researchers and clinicians.

Keywords: Attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, commitment, relationship satisfaction, trust

Attachment theory provides a lens through which romantic behavior can be viewed as systematic and somewhat predictable. Although past research has primarily focused on implications of individuals’ own attachment insecurity dimensions (i.e., anxiety and avoidance) for how they perceive, interpret, and remember relationship-related information, researchers have only recently begun to account for partner characteristics in these associations. Further, this research utilizes a dyadic approach to characterize the dyadic pattern of how each partner’s attachment dimensions might interact with each other in their association with relationship evaluations—in other words, how own attachment links with trust, satisfaction, and commitment might differ as a function of partner attachment.

Attachment theory and links to relationship functioning

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969, 1982) is a theoretical framework that explains how interpersonal experiences are interpreted and how emotions related to these experiences are regulated. In adults, attachment anxiety—stemming from a hyperactivated attachment system—reflects relatively high levels of worry and concern about rejection from romantic partners and a hypervigilance to relationship threats. Conversely, attachment avoidance—stemming from a deactivated attachment system—reflects a discomfort with intimacy and interdependence, emphasizing self-reliance and a preference for low investment in romantic relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003). As such, these attachment dimensions may predispose individuals to process information and engage with others in systematically different ways, creating biases in relationship expectations and perceptions of partner behavior which are important in shaping how attachment anxiety and avoidance can interfere with healthy relationship processes (Collins & Allard, 2001; Collins & Feeney, 2004; Hazan & Shaver, 1994; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003; Rodriguez et al., 2019; Rusbult et al., 2001). Specifically, more anxiously attached (henceforth termed “anxious”) individuals’ desire for closeness and consistent concerns surrounding abandonment and rejection make them hypervigilant to threat-related cues, which elicit beliefs that partners care about them less (Murray et al., 2001) and escalate conflict (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003). Further, more avoidantly attached (henceforth termed “avoidant”) individuals’ history of caregiver neglect and rejection heightens the belief that close others cannot be relied upon in times of need (e.g., Tucker & Anders, 1999), and as such, these individuals avoid dependence and intimacy, and distance themselves from threat-related cues in an attempt to keep the attachment system deactivated (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003). As a result, attachment anxiety and avoidance are generally related to poorer evaluations of the relationship. Although this research has provided valuable insight, the interdependent nature of how the dimensions are inter-twined between partners in a relationship is a relatively untapped topic.

In this research, we examine three key global relationship-related constructs—trust, relationship satisfaction, and commitment. These constructs are classic indicators of relationship functioning, have been previously linked with attachment (described below), and have demonstrated moderate-to-strong associations with relationship persistence in a meta-analysis (Le et al., 2010). First, trust characterizes perceptions about partners’ dependability and beliefs regarding the future of the relationship (Rempel et al., 1985). As such, trust is central to attachment processes (Mikulincer, 1998) and its link with attachment dimensions has been established in previous work. Specifically, individuals higher in insecure dimensions tend to believe others to be less altruistic and trustworthy (Collins & Read, 1990; Mikulincer, 1998; Simpson, 1990).

Second, relationship satisfaction—one’s level of happiness in the relationship—is a central construct in romantic relationship processes (Funk & Rogge, 2007). Previous work has established robust associations between own and partner attachment dimensions and lower relationship satisfaction (see Hadden et al., 2014 for meta-analysis; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016 for review), as well as potential mediating factors for the individual-level associations, including more negative partner attributions for anxiety (Gallo & Smith, 2001; Sümer & Cozzarelli, 2004), problems resolving conflict for both anxiety and avoidant (Feeney, 1994; Marchand, 2004), and deficits in emotional expressivity for avoidant (Feeney, 1999).

Third, commitment is one’s desire to continue and maintain the relationship for the future, with an inherent focus on cognitive interdependence (Agnew et al., 1998). Given anxious individuals’ ambivalence about relationships and avoidant individuals’ preference for independence, it is not surprising that previous work has also found attachment dimensions linked to lower commitment (see Hadden et al., 2014 for meta-analysis; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016 for review), though the reasons may differ for anxious and avoidant subgroups (i.e., lower commitment may occur as a function of higher relationship costs, disappointment, or frustration for anxious individuals in contrast to lower desire to invest in a long-term relationship for avoidant individuals; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2014).

Interdependence in close relationships and the importance of a dyadic perspective

Recent research has begun to explore how a partner’s attachment relates to a person’s relationship evaluations through partner effects in Actor-Partner Interdependence Models (APIM; Kenny et al., 2006). These studies generally support the notion that, in addition to an individual’s own attachment orientations, a partner’s attachment orientations have implications for an individual’s relationship experiences. In particular, a partner effect of avoidance on relationship satisfaction and commitment suggests that individuals with partners higher in avoidance are less satisfied and committed compared to individuals with partners lower in avoidance (e.g., Davila et al., 1999; Fitzpatrick & Lafontaine, 2017; Karantzas et al., 2014; Rodriguez et al., 2019). These dyadic approaches further clarify the nature of attachment in romantic relationships, but stop short in one critical way: Examining the unique combinations of both partners’ attachment through dyadic patterns of attachment. Despite calls for this research (Campbell & Simpson, 2013; Simpson & Howland, 2012), little research has actually explored this dynamic, particularly with continuously measured attachment dimensions.

Seminal work on dyadic patterns (e.g., Kirkpatrick & Davis, 1994) suggests these patterns offer a unique perspective into understanding relationship functioning. However, this early research is limited in that it either used a categorical typology for looking at congruence in attachment (Kirkpatrick & Davis, 1994), used a single-item categorical attachment variable (Senchak & Leonard, 1992; Volling et al., 1998), or collapsed across both types of insecure attachment (e.g., Ben-Ari & Lavee, 2005; Senchak & Leonard, 1992). Previous work has also generally focused more on how secure individuals fare with insecure (versus secure) partners (e.g., Senchak & Leonard, 1992; Volling et al., 1998), rather than on nuances in pairs of insecure individuals, which is more the focus of the current research. Researchers have more recently decided to adopt a continuous (rather than categorical) operationalization of attachment insecurity with separate dimensions for anxiety and avoidance, with individuals relatively low in both being considered secure (Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley & Waller, 1998; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002). In this case, operationalizing attachment dimensionally (rather than categorically) can provide for more nuanced and precise examination of dyadic patterns of attachment within partnerships. For example, it may be a worthwhile empirical question to evaluate whether an individual considered somewhat avoidant evinces different relationship evaluations in their dyadic pattern with their partner compared to someone who is highly avoidant. Combining this dimensional approach with use of the APIM accomplishes two important objectives: (1) it provides a stronger understanding of how both partners’ attachment anxiety and avoidance can be linked to relationship evaluations and, (2) through actor × partner interactions, it demonstrates that associations between one’s attachment dimensions and evaluations can be mitigated or exacerbated as a function of one’s partner’s attachment dimensions.

Combinations of attachment in dyadic relationships

The literature provides some foundation for how partners’ combinations of attachment dimensions might synergistically interact in their associations with trust, satisfaction, and commitment. First, more anxious individuals tend to have a more intense desire for closeness (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). As such, these individuals may have poorer outcomes with a more avoidant partner, as this partner’s aloof, distant, and generally non-responsive behavior (Shallcross et al., 2011) might exacerbate worries or fears that more anxious individuals have, undermining trust and satisfaction. Kirkpatrick and Davis’ (1994) early work supports the idea that such pairings are unsatisfactory, yet stable. While speculative, this suggests that these pairings include a match of partners’ internal working models and mental schemas regarding relationships and partners that binds the partners, despite being unhappy with the relationship. This pattern was supported in work on couples early in their marriage (Feeney, 1994), with results showing wife anxiety paired with husband avoidance to be particularly dissatisfying for both partners. One study has examined dyadic patterns between the continuously measured attachment dispositions of partners (Hadden et al., 2016), with outcomes being fulfillment of needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence in the relationship, constructs which are strongly related to relationship evaluations (Patrick et al., 2007). Although anxious individuals paired with a more avoidant partner reported greater autonomy need fulfillment, this need is less valued by anxious individuals (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), and would seem to support the idea that this combination might result in a less satisfying relationship.

Second, a more anxious person coupling with a more anxious partner may promote greater comfort in that their mutual desire for closeness may provide each with the reassurance they seek, resulting in greater relationship evaluations. Specifically, Hadden and colleagues (2016) found that anxious individuals who paired with another anxious individual reported higher levels of relatedness fulfillment (i.e., feeling related to and connected with one’s partner), but not autonomy (i.e., feeling like one’s actions are self-derived and one has a say in what happens when with the partner). However, as the latter is less valued by anxious individuals (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), this would also support the notion that anxious individuals find relationships with more anxious partners more satisfying.

Third, individuals higher in attachment avoidance generally seek to avoid intimacy (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016) as they hold negative expectations for relationship partners (Collins & Read, 1990). When paired with more anxious partners, avoidant individuals may be less satisfied with the relationship because such partners may push avoidant individuals beyond the amount of intimacy with which they feel comfortable. Indeed, more anxious individuals disclose more about their relationship compared to less anxious individuals (Tan et al., 2012). Such perceived violations of autonomy for avoidant individuals may also result in less trust toward their partner. However, as noted previously, these relationships were previously found to be stable (Kirkpatrick & Davis, 1994)—likely because it fits the schema highly avoidant individuals have for relationships. Therefore, highly avoidant individuals with highly anxious partners may actually report greater commitment.

Finally, the combination of a highly avoidant individual being paired with a highly avoidant partner may be less predictable. Hadden and colleagues (2016) found that avoidant individuals in relationships with other avoidant individuals reported the greatest levels of competence need fulfillment (i.e., feeling capable and effective when with the partner), suggestive of greater satisfaction. Similarly, Mikulincer and Shaver (2007) note that there is surprisingly little evidence to suggest that couples comprising primarily avoidant members function poorly, which may suggest that the desires of two more avoidant individuals are relatively similar or that, like anxious-anxious pairings, there is a match of internal working models about relationships and partners. Although these individuals may feel comfortable and satisfied in such relationships—as they are not being pushed to be intimate or emotionally vulnerable—it is also possible such partners may feed the underlying schema that others cannot be trusted, resulting in lower levels of trust and commitment.

Current research

This research aims to incorporate a dyadic perspective by examining actor and partner effects of attachment dimensions on relationship evaluations of trust, satisfaction, and commitment. We also explore dyadic patterns of attachment—that is, how actor and partner attachment dimensions interact in their association with relationship evaluations. We extend existing work by considering the role of partner attachment dimensions in these associations and, importantly, exploring whether and how actor effects of attachment anxiety and avoidance on relationship evaluations are moderated by partner attachment anxiety and avoidance.

In line with past research, we generally expect that own anxiety and avoidance will evince negative associations with relationship evaluations (Hypotheses 1 and 2). Moreover, based on research highlighting how anxious individuals find greater relatedness from more anxious partners (Hadden et al., 2016) and how limited support and intimacy from avoidant partners might confirm negative relationship schemas of anxious individuals (Kirkpatrick & Davis, 1994), we expect that actor effects of anxiety will be mitigated when partners are more anxious (Hypothesis 3a) and exacerbated when partners are more avoidant (Hypothesis 3b). Finally, based on research suggesting that more avoidant couples reported higher need fulfillment (Hadden et al., 2016) and the differences in the degree to which more anxious and avoidant individuals disclose information in their relationship (Tan et al., 2012), we generally expect that actor effects of avoidance on lower relationship evaluations will be mitigated when partners are more avoidant (Hypothesis 4a) and exacerbated when partners are more anxious (Hypothesis 4b). We will explore the role of gender in these associations, although we make no specific predictions. To address the issue of replication, a concern in psychological science (Open Science Collaboration, 2012), we test our hypotheses in two samples: one of predominantly dating couples and one of married couples. Specific hypotheses are as follows:

Own (i.e., actor) attachment anxiety will be related to lower levels of relationship evaluations (i.e., trust, satisfaction, and commitment; H1). Because so little research has explored this question, we are agnostic about partner anxiety on a person’s relationship evaluations.

Own avoidance will be related to lower levels of trust, satisfaction, and commitment (H2). We are similarly agnostic about partner effects of avoidance on relationship evaluations.

Dyadic patterns of attachment will be associated with relationship evaluations. In other words, actor effects on evaluations will be moderated by partner attachment dimensions. Specifically, actor anxiety effects on more negative relationship evaluations will be weaker when one’s partner is also more anxious (H3a) and stronger when one’s partner is more avoidant (H3b).

Dyadic patterns will also show that actor effects of avoidance on more negative relationship evaluations will be weaker when one’s partner is also more avoidant (H4a) and stronger when one’s partner is more anxious (H4b).

Method

Participants and procedure

In both samples, participants were recruited through flyers, research assistants visiting classrooms, and an online research system at a large southern university in the United States. In both samples, at least one member of the dyad must have been a university student to participate. Participants were directed to complete the study at a time and place convenient for them by clicking a link, which directed them to the study on the Qualtrics survey platform. Students indicated their partner’s name and email address in the survey, and these partners were contacted via email. If partners desired to participate, they could complete the survey online as well via an email invitation. In Sample 1, participants were compensated with course credit and they received more credit if their partners also completed the survey. Partners could receive course credit as well if desired. In Sample 2, all participants were compensated $15 in giftcards and those who were students could receive course credit if desired. Participants in both samples were instructed to complete the survey independently of their partner.

Sample 1. Participants included 185 couples (N = 370) who reported dating or being married to someone of the opposite sex. On average, participants were 22.7 (SD = 4.5) years old and had been together 2.8 (SD = 2.6) years. Most participants (81.5%) indicated they were either exclusively dating, seriously dating, or nearly engaged, 6.4% were engaged, 11.3% married, and 0.8% casually dating. The sample was racially diverse, with 26.6% non-Hispanic Caucasian, 36.6% Hispanic/Latino, 17.7% Asian/Pacific Islander, 11.3% Black, 3.1% Middle Eastern, and 4.7% Other.

Sample 2. Participants included 123 couples (N = 246) wherein at least one partner consumed alcohol one or more times per week (as data were drawn from the baseline assessment of a larger study of alcohol use among heterosexual married couples). Almost all spouses (93.3% of husbands; 90.2% of wives) reported meeting the drinking inclusion criteria, however only a relatively small subset of the individuals met criteria for being considered an at-risk or hazardous drinker according to the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (Saunders et al., 1993). The majority (69.6%) were White, with 9.2% Black, 7.7% Asian, 0.8% Native American/American Indian, 0.4% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 12.3% Multi-ethnic/Other. Approximately one-quarter (26.5%) was Hispanic/Latino. On average, participants were 29.8 (SD = 6.2) years old and had been married 4.3 (SD = 5.1) years.

Measures

Attachment anxiety and avoidance.

In Sample 1, attachment dimensions were measured via the Revised Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire (ECR-R; Fraley et al., 2000). Participants were instructed to indicate their agreement on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) with 36 items assessing attachment anxiety (e.g., “I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me,” “I’m afraid that I will lose my partner’s love”) and avoidance (e.g., “I get uncomfortable when a romantic partner wants to be very close,” “I prefer not to show a partner how I feel deep down”). Both dimensions showed high reliability (αanxiety = .94 and αavoidance = .91). In Sample 2, attachment dimensions were measured via the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale–Short Form (ECR-SF; Wei et al., 2007). This measure includes 12 items asking participants to indicate their agreement on a 7-point scale with response options from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Scores were highly reliable for anxiety (e.g., “I worry that romantic partners won’t care about me as much as I care about them”; α = .73) and avoidance (e.g., “I try to avoid getting too close to my partner”; α = .79). Whereas the ECR-R is a longer measure, the two measures include highly overlapping content: Nine of the 12 items in the ECR-SF are also found in the ECR-R. The ECR-SF was developed by Wei and colleagues (2007), using items from the original Experiences in Close Relationships (Brennan et al., 1998) measure, to create a short form.

Trust.

Trust in partner was assessed with the Rempel et al. (1985) Trust measure. Participants indicated their agreement on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) with 17 items asking about their perceptions of their partner (e.g., “I am certain that my partner would not cheat on me, even if the opportunity arose and there was no chance that he/she would get caught,” “I can rely on my partner to keep the promises he/she makes to me”). Reliability was high (αsample1 = .85; αsample2 = .86).

Satisfaction.

Relationship satisfaction was measured with the satisfaction subscale of Rusbult’s Investment Model Scale (Rusbult et al., 1998). Participants responded to 5 items asking about their relationship (e.g., “My relationship is close to ideal,” “Our relationship makes me very happy”) on a 0 (do not agree at all) to 8 (agree completely) scale (αsample1 = .96; αsample2 = .95).

Commitment.

Commitment to the relationship was also measured with the Investment Model Scale (Rusbult et al., 1998). Participants responded to 7 items asking about their relationship (e.g., “I want our relationship to last for a very long time,” “I am committed to maintaining my relationship with my partner”) on a 0 (do not agree at all) to 8 (agree completely) scale (αsample1 = .90; αsample2 = .86).

Analysis plan

Dyadic model estimation.

Primary hypotheses were evaluated using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (Kenny et al., 2006). This analytic technique models an individual’s outcomes as a function of their own predictors (i.e., actor effects) as well as their partner’s predictors (i.e., partner effects). As we were largely interested in how actor and partner attachment dimensions interacted with each other, main effects were included in a first step and actor × partner interactions were added in a second step. All predictors were grand mean centered. Gender was effect-coded (−1 = female, 1 = male). All analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 PROC MIXED. Non-independence was estimated by the correlation between partner reports. Tests of distinguishability were performed for each sample and were used to evaluate whether information is lost by treating dyad members as indistinguishable. If distinguishability test results preferred a distinguishable model, results were presented as distinguishable across all outcomes for the dataset and ancillary tests examine whether all effects are moderated by gender.

Results

Distinguishability, descriptive statistics, and preliminary associations

Distinguishability.

Interaction models where the paths, means, and variances were free to vary across gender were compared with models where they were constrained to be equal. Results from these analyses revealed that constraining men and women to be equal resulted in a poorer fitting model for most outcomes in Sample 1 (i.e., trust and satisfaction: trust Δχ2(10) = 43.60, p < .001; satisfaction Δχ2(10) = 23.80, p = .008). Similarly, in Sample 2, the constrained model fit worse for most outcomes (i.e., satisfaction and commitment: satisfaction Δχ2(10) = 13.50, p = .034; commitment Δχ2(10) = 21.00, p = .021). As such, we considered men and women to be distinguishable in both samples.

Descriptive statistics and preliminary associations.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations are provided separately by gender and sample in Tables 1 and 2. Generally, anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions were negatively correlated with all three relationship evaluations, with the exception of anxious attachment and trust among men in Sample 1 and anxious attachment and commitment among women in Sample 2.

Table 1.

Correlations among all study variables—sample 1.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxious attachment | .34*** | .53*** | .07 | −.25*** | −.40*** |

| 2. Avoidant attachment | .62*** | .40*** | −.42*** | −.62*** | −.61*** |

| 3. Trust | −.27*** | −.46*** | .16** | .62*** | .36*** |

| 4. Satisfaction | .43*** | −.57*** | .69*** | .49*** | .55*** |

| 5. Commitment | −.51*** | −.56*** | .36*** | .59*** | .46*** |

| M | 3.13 | 2.57 | 5.07 | 6.76 | 6.98 |

| SD | 1.44 | 1.02 | .82 | 1.57 | 1.35 |

| Range | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 0–8 | 0–8 |

*Note. Correlations are provided above the diagonal for men and below the diagonal for women (collapsed descriptives below). Correlations between male and female responses are presented along the diagonal.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Table 2.

Correlations among all study variables—sample 2.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxious attachment | −.02 | .40*** | −.38*** | −.31** | −.17t |

| 2. Avoidant attachment | .34*** | .32*** | −.61*** | −.61*** | −.51*** |

| 3. Trust | −.50*** | −.46*** | .19** | .60*** | .47*** |

| 4. Satisfaction | −.36*** | −.54*** | .67*** | .58*** | .58*** |

| 5. Commitment | −.03 | −.49*** | .32*** | .55*** | .23*** |

| M | 3.22 | 1.87 | 5.88 | 6.84 | 7.48 |

| SD | 1.22 | .88 | .86 | 1.60 | .93 |

| Range | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 0–8 | 0–8 |

*Note. Correlations are provided above the diagonal for men and below the diagonal for women (collapsed descriptives below). Correlations between male and female responses are presented along the diagonal.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Actor-partner interdependence models: Main effects

Hypotheses 1 and 2 posited there would be actor effects of attachment anxiety and avoidance on more negative (i.e., lower) relationship evaluations. APIM main effects results across both samples can be seen in Step 1 results presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Actor-partner interdependence moderation results.

| Outcome | Step | Hyp. | Predictor | Sample 1 |

Sample 2 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | LLCI | ULCI | p | b | t | LLCI | ULCI | p | ||||

| Trust | 1 | — | Gender | .129 | 3.49 | .056 | .201 | <.001 | .004 | .08 | −.097 | .104 | .940 |

| H1 | Actor anxiety | .134 | 4.10 | .070 | .198 | <.001 | −.158 | −3.66 | −.244 | −.073 | <.001 | ||

| — | Partner anxiety | .041 | 1.26 | −.023 | .104 | .207 | .057 | 1.32 | −.028 | .143 | .188 | ||

| H2 | Actor avoidance | −.459 | −9.78 | −.552 | −.367 | <.001 | −.389 | −6.32 | −.511 | −.268 | <.001 | ||

| — | Partner avoidance | −.067 | −1.44 | −.159 | .024 | .150 | −.188 | −3.05 | −.309 | −.066 | .003 | ||

| 2 | H3a | Actor anxiety × Partner anxiety | .084 | 3.34 | .034 | .133 | .001 | .076 | 2.28 | .010 | .142 | .025 | |

| H3b | Actor anxiety × Partner avoidance | .022 | .58 | −.053 | .097 | .565 | −.108 | −2.51 | −.192 | −.023 | .013 | ||

| H4a | Actor avoidance × Partner avoidance | −.047 | −.84 | −.156 | .063 | .399 | .083 | 1.38 | −.037 | .204 | .172 | ||

| H4b | Actor avoidance × Partner anxiety | −.136 | −3.57 | −.212 | −.061 | <.001 | −.073 | −1.71 | −.158 | .011 | .089 | ||

| Satisfaction | 1 | — | Gender | .024 | .44 | −.084 | .132 | .661 | .095 | 1.46 | −.034 | .224 | .149 |

| H1 | Actor anxiety | .047 | .83 | −.063 | .156 | .405 | −.138 | −1.71 | −.297 | .022 | .090 | ||

| — | Partner anxiety | .091 | 1.61 | −.020 | .202 | .107 | .006 | .08 | −.148 | .160 | .939 | ||

| H2 | Actor avoidance | −.891 | −11.11 | −1.048 | −.733 | <.001 | −.748 | −7.33 | −.949 | −.547 | <.001 | ||

| — | Partner avoidance | −.291 | −3.62 | −.449 | −.133 | <.001 | −.436 | −4.23 | −.639 | −.232 | <.001 | ||

| 2 | H3a | Actor anxiety × Partner anxiety | .104 | 2.10 | .006 | .202 | .037 | .125 | 1.75 | −.016 | .267 | .083 | |

| H3b | Actor anxiety × Partner avoidance | −.012 | −.18 | −.151 | .126 | .861 | −.170 | −2.11 | −.329 | −.011 | .037 | ||

| H4a | Actor avoidance × Partner avoidance | −.159 | −1.45 | −.377 | .058 | .149 | −.082 | −.62 | −.343 | .179 | .534 | ||

| H4b | Actor avoidance × Partner anxiety | −.164 | −2.33 | −.302 | −.026 | .020 | −.234 | −2.93 | −.391 | −.076 | .004 | ||

| Commitment | 1 | — | Gender | −.041 | −.80 | −.140 | .059 | .423 | .030 | .59 | −.070 | .130 | .557 |

| H1 | Actor anxiety | −.129 | −2.68 | −.223 | −.034 | .008 | .089 | 1.77 | −.010 | .188 | .078 | ||

| — | Partner anxiety | −.133 | −2.77 | −.227 | −.039 | .006 | −.030 | −.60 | −.129 | .068 | .546 | ||

| H2 | Actor avoidance | −.553 | −.800 | −.689 | −.417 | <.001 | −.509 | −7.47 | −.644 | −.375 | <.001 | ||

| — | Partner avoidance | −.113 | −1.64 | −.248 | .023 | .103 | −.063 | −.92 | −.198 | .071 | .356 | ||

| 2 | H3a | Actor anxiety × Partner anxiety | −.015 | −.38 | −.092 | .062 | .702 | .086 | 2.13 | .006 | .167 | .036 | |

| H3b | Actor anxiety × Partner avoidance | −.025 | −.43 | −.139 | .089 | .666 | .011 | .23 | −.085 | .108 | .819 | ||

| H4a | Actor avoidance × Partner avoidance | −.211 | −2.44 | −.381 | −.040 | .016 | −.196 | −2.64 | −.344 | −.049 | .010 | ||

| H4b | Actor avoidance × Partner anxiety | −.044 | −.76 | −.158 | .070 | .451 | −.043 | −.87 | −.140 | .054 | .384 | ||

Note. Hyp = hypothesis. Statistically significant (p < .05) associations are bolded.

We first explored actor and partner effects on trust. Significant actor effects of anxiety emerged in Samples 1 and 2. Anxiety was associated with higher trust in Sample 1, but lower trust in Sample 2, supporting H1 in Sample 2. In both samples, significant negative actor effects of avoidance suggested avoidance was related to lower trust, supporting H2. In Sample 2, a partner avoidance effect also emerged, suggesting individuals with more avoidant partners trusted their partner less. Results exploring satisfaction did not support H1 but did support H2 in both samples: Although neither actor nor partner anxiety was significantly related to satisfaction, both actor and partner avoidance were negatively related to satisfaction (ps < .001). For commitment, H1 was supported in Sample 1 as actor and partner effects of anxiety suggested more anxious individuals and those with more anxious partners were less committed to the relationship. Further, across both samples, actor avoidance was related to lower relationship commitment, again supporting H2.

Actor-partner interdependence models: Actor × Partner interactions

Hypotheses 3 and 4 posited there would be significant actor × partner attachment dimension interactions on relationship evaluations, such that actor effects of attachment anxiety would be mitigated when partners were more anxious (H3a) and exacerbated when partners are more avoidant (H3b), and that actor effects of avoidance would be mitigated when partners were more avoidant (H4a) and exacerbated when partners were more anxious (H4b). APIM interaction results across both samples can be seen in Step 2 results presented in Table 3.

Trust.

Results from a model including all actor × partner attachment interactions on trust revealed a significant actor anxiety × partner anxiety interaction in both samples (H3a) and a significant actor anxiety × partner avoidance interaction emerged in Sample 2 (H3b). A significant actor avoidance × partner anxiety also emerged Sample 1 (H4b). Thus, effects of own attachment anxiety were moderated by both partner anxiety and partner avoidance, and the effect of own avoidance was moderated by partner anxiety.

We first looked at simple effects of actor anxiety at high and low (+/−1 SD) levels of partner anxiety (H3a; Figure 1a for Sample 1 and Figure 1b for Sample 2). In Sample 1, among those with more anxious partners, own anxiety was associated with higher trust, b = .22, p < .001, an association not seen among those with less anxious partners, b = −.02, p = .724. Similarly, in Sample 2, among those with less anxious partners, those with higher anxiety themselves trusted their partner less, b = −.23, p < .001, an association not seen among those with more anxious partners, b = −.04, p = .517. Taken together, these results suggest that partner anxiety buffered trust for those who were more anxious themselves. In other words, anxious individuals trust their partner more when their partner is more anxious as well.

Figure 1a.

Sample 1: Actor × partner anxiety on trust. ***p < .001. b. Sample 2: Actor × partner anxiety on trust. ***p < .001.

Second, in Sample 2, a significant actor anxiety × partner avoidance interaction emerged (H3b). We examined the simple effects of actor anxiety at high and low levels of partner avoidance (Figure 2). Among those with more avoidant partners, own anxiety was negatively related to trust, b = −.23, p < .001, an association not seen among those with less avoidant partners, b = −.04, p = .530. This interaction suggests that own anxiety effects on trust are present only when partners are higher in avoidance.

Figure 2.

Sample 2: Actor anxiety × partner avoidance on trust. **p < .01.

Finally, we disentangled the actor avoidance × partner anxiety interaction (H4b) by examining simple effects of actor avoidance at high and low levels of partner anxiety in Sample 1 (Figure 3). The main effect of actor avoidance suggested that more avoidant individuals trust their partner less than less avoidant individuals, and the moderation results suggested that this was stronger among those with more anxious partners, b = −.62, p < .001, compared to those with less anxious partners, b = −.22, p = .003.

Figure 3.

Sample 1: Actor avoidance × partner anxiety on trust. **p < .01 ***p < .001.

Satisfaction.

The pattern of results with satisfaction was essentially identical to results examining trust. Models including interactions revealed significant actor anxiety × partner anxiety (H3a) in Sample 1, another actor anxiety × partner avoidance (H3b) interaction in Sample 2, and actor avoidance × partner anxiety (H4b) interactions in both samples. First, simple effects of actor anxiety at high and low levels of partner anxiety (H3a; Figure 4) showed a pattern wherein for individuals paired with more anxious partners, their own anxiety was positively related to their satisfaction in Sample 1, b = .16, p = .067, a slope which did not reach statistical significance and in a different direction than among those with less anxious partners, b = −.15, p = .137, which also did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 4.

Sample 1: Actor × partner anxiety on satisfaction. †p < .10.

Second, regarding the actor anxiety × partner avoidance interaction (H3b), we examined simple effects of actor anxiety at high and low levels of partner avoidance (Figure 5). Consistent with trust results, among those with more avoidant partners, own anxiety was negatively related to satisfaction, b = −.30, p = .003, an association not seen among those with less avoidant partners, b = −.01, p = .972.

Figure 5.

Sample 2: Actor anxiety × partner avoidance on satisfaction. **p < .01.

Finally, we examined simple effects of actor avoidance at high and low levels of partner anxiety (H4b; Figure 6a for Sample 1 and Figure 6b for Sample 2). Again, own avoidance was negatively related to satisfaction, and this was again stronger among those with more anxious partners, bsample1 = −1.08, p < .001, bsample2 = −.90, p < .001, compared to those with less anxious partners, bsample1 = −.61, p < .001, bsample2 = −.33, p = .040.

Figure 6a.

Sample 1: Actor avoidance × partner anxiety on satisfaction. ***p < .001. b. Sample 2: Actor avoidance × partner anxiety on satisfaction. ***p < .001.

Commitment.

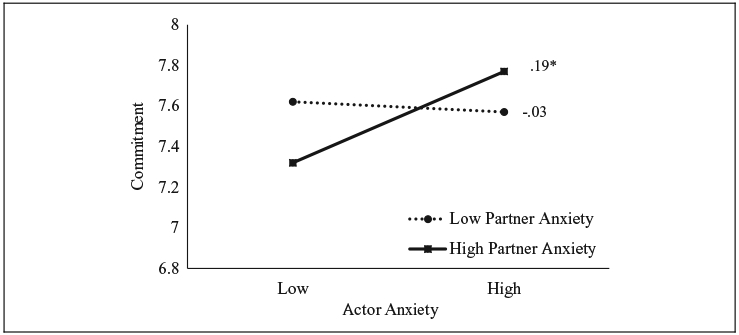

Results examining commitment revealed a significant actor × partner interaction of anxiety (H3a) in Sample 2 and significant actor × partner interactions of avoidance in both samples (H4a). As shown in Figure 7, actor anxiety was positively related to commitment for individuals with more anxious partners, b = .19, p = .018, and was unrelated to commitment for those with less anxious partners, b = −.03, p = .692.

Figure 7.

Sample 2: Actor × partner anxiety on commitment. *p < .05.

As presented in Figures 8a (Sample 1) and 8b (Sample 2), simple effects analyses showed that actor avoidance was negatively related to commitment, and this was stronger among those with more avoidant partners, bsample1 = −1.01, p < .001, bsample2 = −.61, p < .001, compared to those with less avoidant partners, bsample1 = −.68, p < .001, bsample2 = −.26, p = .017.

Figure 8a.

Sample 1: Actor × partner avoidance on commitment. ***p <.001. b. Sample 2: Actor × partner avoidance on commitment. *p < .05 ***p < .001.

Discussion

This research sought to replicate previous findings indicating that attachment anxiety and avoidance are generally associated with poorer relationship outcomes (Fitzpatrick & Lafontaine, 2017; Karantzas et al., 2014; Rodriguez et al., 2019), and further explore how (a) partner attachment contributes to relationship evaluations and (b) combinations of attachment dimensions interact between partners to be systematically related to relationship evaluations. It is important to note that although we discuss main effects, several of them were qualified by actor × partner interactions and should be interpreted with this in mind. Results from main effects models were somewhat mixed with anxiety and more consistent with avoidance in associations with relationship evaluations. Specifically, actor anxiety was related to lower trust in Sample 2 and lower commitment in Sample 1. However, actor anxiety was unrelated to satisfaction in both samples and was related to higher trust in Sample 1. Thus, results were less clear for actor anxiety. Partner anxiety was related to lower commitment in Sample 1 but otherwise unrelated to relationship evaluations. Results with avoidance were more straightforward: Actor avoidance was negatively linked with all three relationship evaluations in both studies. In other words, in all cases, more avoidant individuals were less trusting, satisfied with, and committed to their partner. Partner avoidance effects were significant on lower satisfaction in both samples and on lower trust in Sample 2, indicating individuals with more avoidant partners were less happy and, in Sample 2, trusted their partner less also.

Novel to the current study was a focus on dyadic patterns of attachment. Results revealed support for three of four hypothesized combinations of actor × partner interactions. For trust and satisfaction, interactions emerged for actor anxiety × partner anxiety in both samples, for actor anxiety × partner avoidance in Sample 2, and for actor avoidance × partner anxiety in both samples. Further, significant actor × partner anxiety interaction and actor avoidance × partner avoidance interactions emerged for commitment. We consider each of these separately here.

First, the pattern of actor anxiety × partner anxiety interactions that emerged for all three outcomes showed that among those with more anxious partners, own anxiety was either more positively related—or less negatively related—to trust and satisfaction compared to those with less anxious partners. This pattern also emerged for commitment in Sample 2. While this might seem like the results were divergent, the underlying pattern is consistent. In other words, the general trend across outcomes and samples suggested that the associations between own anxiety and relationship evaluations was either more positive with a more anxious partner or more negative with a less anxious partner. It appears that partner anxiety can provide an additional sense of contentment with the relationship among those who are more anxious themselves, which is consistent with Hadden and colleagues’ (2016) findings that individuals in these pairings reported greater need fulfillment for relatedness. A similar pattern was also reported in a study on parent-teen dyads (Chow et al., 2017): Parent-reported closeness was highest when both were low or when both were high in anxiety. A mismatch between levels of anxiety for parents and teens was related to lower closeness.

Second, the actor anxiety × partner avoidance interaction that emerged in Study 2 for both trust and satisfaction suggests that anxious individuals experience poorer relationship quality when paired with an avoidant partner. In contrast to the previous interaction described above, anxious individuals were less happy with the relationship and trusting when paired with a more avoidant partner. Again, this is consistent with theory indicating that this is not what anxious individuals desire in a relationship (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Third, the actor avoidance × partner anxiety interactions reliably demonstrated that actor avoidance was negatively associated with trust and satisfaction, an association exacerbated when one’s partner was more anxious. This is consistent with a theoretical perspective of attachment, with partner anxiety creating additional stress in the face of own avoidance (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Specifically, the desire for intimacy and closeness from anxious partners may challenge an avoidant individuals’ desire for autonomy. In sum, across both actor × partner interactions, the pattern of results for anxious—avoidant pairings suggests that this is a particularly dissatisfying combination for both individuals.

Finally, while not hypothesized, the actor avoidance × partner avoidance interaction on commitment suggested that avoidance was negatively related to commitment, and this was stronger among those with more avoidant partners. Although actor avoidance was significantly negatively related to all three relationship evaluations in both samples, it was only exacerbated by a more avoidant partner in the case of relationship commitment. We did not expect avoidant-with-avoidant pairings to report the lowest levels of relationship commitment, but we can speculate that the general evasion of discussing future activities, plans, and dreams indicative of commitment typical of avoidantly attached individuals may become intensified when one’s partner is also more avoidant. Moreover, avoidant individuals tend to expect close others to be unreliable and unresponsive to their needs (Collins & Read, 1990), negative expectations which, when considered with more self-focused goals and motivations as evidenced during relationship discussions (or a lack thereof), result in perceptions of lower relationship commitment. Future studies may wish to explore this further. In Chow and colleagues’ (2017) research, parents reported the lowest closeness when both they and their teen were higher in avoidance.

Implications for clinicians and researchers

For clinicians working with distressed couples, it is possible that one or both partners may be highly anxious, avoidant, or both. Our findings suggest that those with higher anxiety and avoidance scores tended to have worse relationship outcomes than those lower in anxiety or avoidance. This was consistent with previous research and theory indicating that secure individuals are more resilient in the face of challenges to intimacy or autonomy (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016) and generally true regardless of partner attachment. Clinicians may wish to incorporate ways of preventing immediate insecurity from damaging relationship quality (e.g., during diagnostic situations) as well as find ways the couple can enhance secure working models in both partners over time.

Clinicians’ understanding of how dyadic patterns are linked to trust, satisfaction, and commitment, as well as other potential factors such as responsiveness, communication styles, and conflict management may suggest different avenues for treatment. Our dyadic pattern results generally suggested that for anxious individuals, being paired with a more anxious partner was beneficial for their relationship, whereas being paired with a more avoidant partner detrimental. For avoidance, results generally suggested that being paired with a more anxious individual resulted in even lower trust and satisfaction whereas being paired with a more avoidant individual resulted in even lower commitment. Given the tendency for romantic partners to pair with a similarly secure or insecure partner (Feeney, 1994; Senchak & Leonard, 1992), clinicians may wish to be especially aware of partnerships that appear to be in greatest need—that of two insecurely attached partners. Clinicians working with these couplings may wish to help each person understand that their partner has different internal working models or schemas, as well as the ways in which they can behave toward their partner to make them feel more versus less supported. Helping these couples be less myopic from their own perspective and instead see the relationship from their partner’s point of view may help them come to a “middle ground” of understanding, which in turn may be particularly helpful in read-justing expectations about what each partner wants and needs for the relationship to be satisfying and stable. For example, individuals who have more anxious partners will likely have more constructive outcomes from approaching sensitive topics differently than individuals with more avoidant partners (Arriaga et al., 2018).

Importantly, the current study heeded the call for research exploring dyadic patterns of attachment (Simpson & Howland, 2012). Despite the relative explosion of dyadic research over the last several decades, most of this work has focused on how partners affect each other without accounting for dyadic patterns—in other words, emergent dyadic interactions. Our findings point to the importance of considering dyadic patterns of attachment, as partners’ particular insecurities can in some cases mitigate—and in other cases exacerbate—the negative implications of each other’s insecurities on relationship quality. More broadly, the findings presented here highlight the importance of considering such actor × partner interactions when theoretically appropriate, as it is beneficial for gaining a more comprehensive, nuanced, and precise understanding of romantic relationships.

Limitations and future directions

This research should be considered in light of its limitations. First, there are differences in the way attachment was scored in Samples 1 and 2, with a short form (albeit validated) used in Sample 2. Second, Sample 2 used an inclusion criterion related to alcohol use as it was data utilized from a study whose primary aims were about relationship processes and alcohol use, and as such, findings may not be generalized to all married couples. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the results presented limits our ability to determine temporal or causal nature of the associations between attachment dimensions and relationship evaluations. Indeed, attachment dimensions can fluctuate over time and as a function of relationship characteristics (Arriaga & Kumashiro, 2019). Additionally, many results presented were consistent across samples, but future research can further point to the consistency and replicability of findings as well as potentially address discrepant findings (e.g., anxiety associated with higher trust in Sample 1 but lower trust in Sample 2) as a function of sample characteristics (e.g., Sample 1 was largely dating and Sample 2 was exclusively married).

Future research may also wish to explore mechanisms through which these processes occur. Possible mechanisms include those previously established as mediators of associations between own insecurity and poorer evaluations (see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016, for review): greater negative attributions (Gallo & Smith, 2001; Sumer & Cozzarelli, 2004), emotional reactions and reactivity to daily events (Campbell et al., 2005), and perceptions of partner relationship evaluations (Rodriguez et al., 2019). For example, those higher in anxiety and those higher in avoidance displayed a pessimistic bias for both relationship satisfaction and commitment. In other words, they perceived their partners to have more negative relationship evaluations than their partners actually did. Longitudinal research will be able to more closely disentangle processes of—for example—how a more avoidant person’s relatively low commitment might intensify his or her partner’s anxiety. Finally, it is interesting that dyadic pattern interactions were primarily evident for relationship evaluations related to trust and satisfaction and not for commitment. Although speculative, it is possible that evaluations of trust and satisfaction are more sensitive to attachment-related processes than commitment. Indeed, Etcheverry and colleagues (2013) tested how attachment dimensions related to the investment model, with results showing that attachment anxiety and avoidance were more strongly related to satisfaction than to commitment (and that anxiety’s path to commitment was significant via satisfaction). Future research should seek to further unravel intricacies among attachment and different types of relationship evaluations, especially in the context of interdependence.

Conclusion

This research provides initial support for a dynamic model of conceptualizing attachment patterns as a function of the combination of both relationship partners. Whereas individuals’ attachment dimensions were related to their own relationship evaluations, partners’ dimensions were as well, and importantly, links between own dimensions and evaluations were different as a function of partner characteristics. In some cases, partner characteristics mitigated negative effects of attachment, whereas in other cases partner characteristics exacerbated them. We hope this research can move the field toward a more interdependent way of approaching relationship processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Open research statement

As part of IARR’s encouragement of open research practices, the author(s) have provided the following information: This research was not pre-registered. The data used in the research are cannot be publicly shared but are available upon request. The data can be obtained by lrodriguez12@usf.edu. The materials used in the research cannot be publicly shared but are available upon request. The materials can be obtained by lrodriguez12@usf.edu.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Agnew CR, Van Lange PA, Rusbult CE, Langston CAJJOP, & Psychology S (1998). Cognitive interdependence: Commitment and the mental representation of close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 939. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, & Kumashiro M (2019). Walking a security tightrope: Relationship-induced changes in attachment security. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 121–126. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, Kumashiro M, Simpson JA, & Overall NC (2018). Revising working models across time: Relationship situations that enhance attachment security. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(1), 71–96. 10.1177/1088868317705257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari A, & Lavee Y (2005). Dyadic characteristics of individual attributes: Attachment, neuroticism, and their relation to marital quality and closeness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(4), 621–631. 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume I: Attachment (2nd ed.). Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664–678. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, & Shaver PR (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In Simpson JA & Rholes WS (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, & Simpson JA (2013). The blossoming of relationships science. In Simpson JA & Campbell L (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of close relationships (pp. 3–10). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398694.013.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson JA, Boldry J, & Kashy DA (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: the role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 510–531. 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CM, Hart E, Ellis L, & Tan CC (2017). Interdependence of attachment styles and relationship quality in parent-adolescent dyads. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 77–86. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, & Allard LM (2001). Cognitive representations of attachment: The content and function of working models. In Fletcher GJ & Clark MS (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Interpersonal processes (Vol. 2, pp. 60–85). Blackwell Publishers. 10.1002/9780470998557.ch3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, & Feeney BC (2004). Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: Evidence from experimental and observational studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 363–383. 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, & Read SJ (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 644–663. 10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Karney BR, & Bradbury TN (1999). Attachment change processes in the early years of marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(5), 783–802. 10.1037//0022-3514.76.5.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etcheverry PE, Le B, WU TF, & Wei M (2013). Attachment and the investment model: Predictors of relationship commitment, maintenance, and persistence. Personal Relationships, 20(3), 546–567. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA (1994). Attachment style, communication patterns, and satisfaction across the life cycle of marriage. Personal Relationships, 1(4), 333–348. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1994.tb00069.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA (1999). Adult romantic attachment and couple relationships. In Cassidy J & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 355–377). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick J, & Lafontaine M-F (2017). Attachment, trust, and satisfaction in relationships: Investigating actor, partner, and mediating effects. Personal Relationships, 24(3), 640–662. 10.1111/pere.12203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley CR, & Waller NG (1998). Adult attachment patterns: A test of the typological model. In Simpson JA & Rholes WS (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 77–114). Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley CR, Waller NG, & Brennan KA (2000). An Item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 350–365. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk JL, & Rogge RD (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the couples satisfaction index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, & Smith TW (2001). Attachment style in marriage: Adjustment and responses to interaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18(2), 263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hadden BW, Rodriguez LM, Knee CR, DiBello AM, & Baker ZG (2016). An Actor–partner interdependence model of attachment and need fulfillment in romantic dyads. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(4), 349–357. 10.1177/1948550615623844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadden BW, Smith CV, & Webster GD (2014). Relationship duration moderates associations between attachment and relationship quality: meta-analytic support for the temporal adult romantic attachment model. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(1), 42–58. 10.1177/1088868313501885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, & Shaver PR (1994). Attachment as an organizational framework for research on close relationships. Psychological Inquiry, 5(1), 1–22. 10.1207/s15327965pli0501_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karantzas GC, Feeney JA, Goncalves CV, & McCabe MP (2014). Towards an integrative attachment-based model of relationship functioning. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 413–434. 10.1111/bjop.12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). Dyadic data analysis. The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA, & Davis KE (1994). Attachment style, gender, and relationship stability: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(3), 502–512. 10.1037/0022-3514.66.3.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le B, Dove NL, Agnew CR, Korn MS, & Mutso AA (2010). Predicting nonmarital romantic relationship dissolution: A meta-analytic synthesis. Personal Relationships, 17(3), 377–390. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01285.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M (1998). Attachment working models and the sense of trust: An exploration of interaction goals and affect regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1209–1224. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2003). The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In Zanna MP (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 35., pp. 53–152). Elsevier Academic Press. 10.1016/s0065-2601(03)01002-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2007). Individual differences in attachment-system function: Development, stability, and change. In Mikulincer M & Shaver PR (Eds.), Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (pp. 116–146). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2016). Attachment processes and couple functioning. In Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (2nd ed., pp. 299–346). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW, Bellavia G, & Rose P (2001). The mismeasure of love: How self-doubt contaminates relationship beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(4), 423–436. 10.1177/0146167201274004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Open Science Collaboration. (2012). An open, large-scale, collaborative effort to estimate the reproducibility of psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 657–660. 10.1177/1745691612462588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick H, Knee CR, Canevello A, & Lonsbary C (2007). The Role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 434. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempel JK, Holmes JG, & Zanna MP (1985). Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(1), 95–112. 10.1037/0022-3514.49.1.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Fillo J, Hadden BW, Øverup CS, Baker ZG, & DiBello AM (2019). Do you see what I see? Actor and partner attachment shape biased perceptions of partners. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(4), 587–602. 10.1177/0146167218791782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Arriaga XB, & Agnew CR (2001). Interdependence in close relationships. In Fletcher GJO & Clark MS (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Vol. 2. interpersonal processes. Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Martz JM, & Agnew CR (1998). The Investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5(4), 357–387. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senchak M, & Leonard KE (1992). Attachment styles and marital adjustment among newlywed couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9(1), 51–64. 10.1177/0265407592091003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shallcross SL, Howland M, Bemis J, Simpson JA, & Frazier P (2011). Not “capitalizing” on social capitalization interactions: The role of attachment insecurity. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 77–85. 10.1037/a0021876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, & Mikulincer M (2002). Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attachment & Human Development, 4(2), 133–161. 10.1080/1461673021015417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA (1990). Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 971–980. 10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, & Howland M (2012). Bringing the partner into attachment theory and research. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(4), 282–289. 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00134.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sümer N, & Cozzarelli C (2004). The impact of adult attachment on partner and self-attributions and relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 11(3), 355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Tan R, Overall NC, & Taylor JK (2012). Let’s talk about us: Attachment, relationship-focused disclosure, and relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 19(521–534). 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01383.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, & Anders SL (1999). Attachment style, interpersonal perception accuracy, and relationship satisfaction in dating couples. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(4), 403–412. 10.1177/0146167299025004001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, Notaro PC, & Larsen JJ (1998). Adult attachment styles: Relations with emotional well-being, marriage, and parenting. Family Relations, 47(4), 355–367. 10.2307/585266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, & Vogel DL (2007). The experiences in close relationship scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(2), 187–204. 10.1080/00223890701268041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.