Abstract

Background

Current research suggests that the glial scar surrounding penetrating brain injuries is instrumental in preserving the surrounding uninjured tissue by limiting the inflammatory response to the injury site. We recently showed that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-stimulated gene-6 (TSG-6), a well-established anti-inflammatory molecule, is present within the glial scar. In the present study we investigated the role of TSG-6 within the glial scar using TSG-6 null and littermate control mice subjected to penetrating brain injuries.

Results

Our findings show that mice lacking TSG-6 present a more severe inflammatory response after injury, which was correlated with an enlarged area of astrogliosis beyond the injury site.

Conclusion

Our data provides evidence that TSG-6 has an anti-inflammatory role within the glial scar.

Keywords: TSG-6, Glial scar, Astrocytes, Glycosaminoglycans and inflammation

Background

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major medical concern that affects over 10 million people in the world each year [1, 2]. A variety of injuries can cause TBI leading to a range of injury severities [3–7]. With improved medical interventions over the years, the mortality rate due to TBI has decreased, resulting in a significant number of people living with the long-term effects of TBI. It is well accepted that in addition to the immediate effects of TBI there are also multiple potential long-term gradually evolving sequelae that are influenced by the type of injury, severity of the injury and medical interventions at the time of injury [8, 9]. Additionally, a link between mild traumatic brain injuries and Alzheimer’s disease or chronic traumatic encephalopathy has long been suspected [10]. At present, long-term effects of repeated TBI have been seen in multiple sports-related injuries, including post-traumatic parkinsonism, post-traumatic dementia and chronic post-concussion syndrome [11–14]. Thus, studying the short- and long-term consequences of TBI at a cellular and molecular level may lead to a new understanding and perhaps better long-term management of such injuries via new and/or refined treatment strategies.

Astrogliosis is a hallmark of TBI, which commences hours after injury and leads to an abnormal increase in the number of activated astrocytes in and around the injury site [15, 16]. Immediately after injury (acute phase), astrocytes are activated, becoming highly proliferative and up-regulating the production of extracellular proteins [17–19]. These astrocytes and their deposited extracellular matrix in and around the injury site form a glial scar. Over the years, a significant body of evidence has demonstrated that the glial scar contains molecules, such as chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), that impede axonal growth, thus inhibiting neuronal regeneration [15, 20–23]. The intensity of the acute and chronic reactive astrogliosis, including the quantity and composition of the glial scar, affects immediate and long-term effects of TBI [6, 16, 24, 25]. Penetrating brain injuries (PBIs) cause direct parenchymal laceration, neuronal cell loss and hemorrhage, which lead to focal tissue damage at the injury site. Astrogliosis is triggered after TBIs forming a glial scar in and around the injury site [26–29]. Importantly, uninjured tissue bordering the injury site is also subject to astrogliosis, and the process of glial scarring therefore extends beyond the injury site [30]. Given the fact that glial scarring limits regeneration after injury, many studies have investigated whether limiting astrogliosis after injury, with particular focus on limiting deposition, could potentially promote regeneration [23, 27, 31–34]. Although many studies were able to demonstrate beneficial effects of limiting glial scarring on neuronal regeneration, many others were inconclusive or actually found there was an increased inflammatory response culminating in tissue damage beyond the injury site and an increase in neuronal loss. Thus, mounting evidence indicates that reactive astrocytes surrounding the injury site are instrumental in preserving the surrounding uninjured tissue by forming scar borders, which separate damaged and inflamed tissue from adjacent viable neural tissue [15, 16, 24, 35–40]. Sofroniew and colleagues elegantly demonstrated that targeting astrocytes after brain and spinal cord injury leads to increased inflammation, delayed recovery and increased neuronal loss [39, 41–44]. Moreover, the inhibition of astrocyte proliferation prolongs the healing period following central nervous system (CNS) injury [45]. Data from Hermann et al. show that GFAP-driven ablation of STAT3 in astrocytes leads to the loss of lesion demarcation and subsequent glial scar formation, and, in turn, results in increased invasion of inflammatory cells into adjacent viable tissue and further spread of inflammation [46]. This suggests that early glial scar formation by astrocytes restricts movement of inflammatory cells located within the lesion site into adjacent healthy tissue, thereby restricting tissue damage to the injury site. Thus, a recent body of evidence suggests scar tissue bordering the injury site is necessary for limiting inflammation and tissue damage to the injury site [37, 41]. There is currently a significant number of studies investigating how reactive astrocytes regulate and limit inflammation to the injury site, and which cellular components and major pathways could play a role in this process [20, 35, 41, 45, 47].

We recently found that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-stimulated gene-6 (TSG-6) is secreted by astrocytes after injury and is a major constituent of the glial scar, but the role it plays within the glial scar remains to be established [48]. TSG-6 is a 35-kDa protein that is secreted by a wide range of cell types in response to inflammatory mediators and growth factors [49], and was originally identified as a gene product induced in fibroblasts by TNF [12]. TSG-6 contains a link module domain that mediates its interaction with the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) hyaluronan (HA) and CS [49–51]. Our recent study identified that TSG-6 is expressed in the CNS, where it catalyzes the transfer of heavy chains (HCs) from Inter-a-Inhibitor (IαI, also known as ITI) onto HA, forming a specialized HA/HC/TSG-6 matrix within the glial scar, but the role of this specialized matrix within the glial scar remains to be established [48, 52–56]. This specific HA/HC/TSG-6 matrix has previously been shown to be monocyte-adhesive in other tissues and is believed to be present in most, if not all, inflammatory processes [57, 58]. These TSG-6 modified HA matrices bind inflammatory cells, and the interaction of these cells with this matrix modulates their responses, which are central to pathological inflammation [59–65]. The main objective of this study was to investigate the role TSG-6, a constituent of the glial scar, has in astrogliosis after a PBI. Given the well-characterized anti-inflammatory role of TSG-6 in other sites, the premise of this study was that TSG-6 could participate in the formation of an immunosuppressive environment within the glial scar. Our findings show that TSG-6 null mice present a more severe inflammatory response and increased glial scar deposition after injury when compared to littermate control mice. This increased inflammatory response in TSG-6 null mice was correlated with an enlarged area of astrogliosis beyond the injury site.

Results

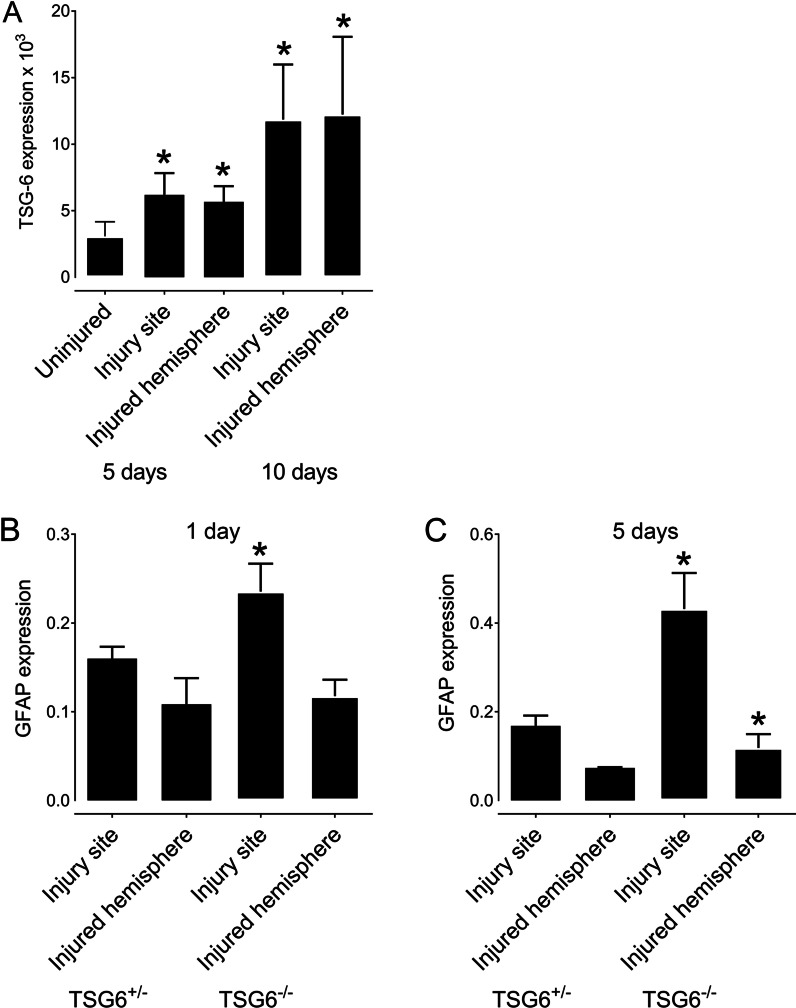

TSG-6 expression after PBI

In this study, transgenic Tsg-6 null mice (Tnfip6Δ/Δ), hereafter referred to as Tsg-6−/− mice, and heterozygous mice, hereafter referred to as Tsg-6+/− mice, were used to investigate the role of TSG-6 in the glial scar. In order to investigate whether TSG-6 is present in the glial scar after brain injury, we analyzed the expression profile of Tsg6 in the injury site and injured hemisphere before and after a PBI in Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 1A). There was a twofold increase in Tsg-6 expression 5 days after injury when compared to uninjured mice. There was a further increase in Tsg-6 expression over time after injury, with expression increasing two fold from 5 to 10 days after injury (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, we did not find a difference in the expression levels of Tsg-6 between the injury site and the remaining hemisphere, indicating that Tsg-6 expression is not contained solely to the injury site (Fig. 1A). Therefore, there is also an increase in Tsg-6 expression in the surrounding tissue after injury. No Tsg-6 expression was identified in any of the samples from Tsg-6−/− mice confirming that these mice are indeed null for Tsg-6.

Fig. 1.

TSG-6 and GFAP expression after PBI. TSG-6 and GFAP mRNA expressions were quantified in the injury site and the injured hemisphere after PBI. A TSG+/− mice were subjected to PBI, and the injury site and remaining injured hemisphere were collected 5 and 10 days after injury for analysis of TSG-6 expression. B, C TSG+/− and TSG-6−/− mice were subjected to PBI, and the injury site and remaining injured hemisphere were collected 1 day (B) and 5 days (C) after injury for analysis of GFAP expression. * = p ≤ 0.05 comparing TSG-6−/+ and TSG-6−/− mice

Analysis of astrocyte recruitment after PBI

We assessed the level of astrogliosis in the injury site and in the remaining injured hemisphere by quantifying the levels of GFAP+ astrocytes using real-time PCR (Fig. 1B, C). For such, we isolated mRNA from the injury site and remaining injured hemisphere 1 and 5 days after injury of Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice. Both Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice presented an increase in the levels of GFAP expression in the injury site when compared to the remaining injured hemisphere, which corroborates literature [36, 63, 64]. Tsg-6−/− mice showed a significant increase in GFAP levels within the injury site at both 1 and 5 days post-injury when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 1B, C). This data indicates that Tsg-6−/− mice have more astrocytes in the injury site when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice. At 5 days after injury, there was a significant increase in GFAP expression in the injured hemisphere of Tsg-6−/− mice compared to Tsg-6+/− mice, indicating that Tsg-6−/− mice present astrogliosis beyond the injury site at 5 days post-injury.

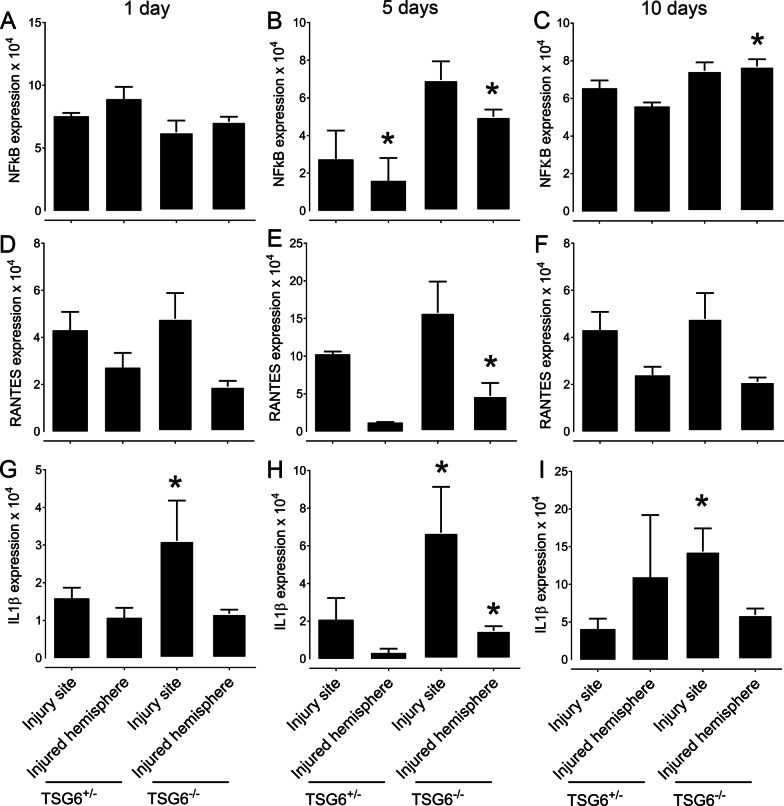

The effect of TSG-6 on the secretion of inflammatory markers after PBI

The inflammatory response was also assessed in Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice 1, 5 and 10 days post-injury by quantifying the expression levels of NFκB, Rantes and IL1β (Fig. 2). Higher expression levels of NFκB, Rantes and IL1β were detected in Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice during the acute phase after injury. Specifically, a ~ 2.5-fold and threefold increase in NfκB expression was found in the injury site and remaining injured hemisphere, respectively, in Tsg-6−/− mice compared to Tsg-6+/− mice 5 days after injury (Fig. 2B). 10 days after injury there was still a significant increase in NfκB expression in the surrounding hemisphere of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 2C). No significant differences were found in the expression of NfκB between Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice 1 day after injury (Fig. 1A). The levels of Ccl5 (Rantes) were also assessed 1, 5 and 10 days post-injury. There was a significant increase in the expression of Rantes in the injured hemisphere of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (a four fold increase) 5 days after injury; however, no difference was found between Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice 1 and 10 days post-injury (Fig. 2D–F). IL1β levels were increased in the injury site of TSG-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice at 1 day post-injury (Fig. 2G). At 5 days post-injury a threefold and fourfold increase in the expression of IL1β were noted in the injury site and remaining injured hemisphere, respectively, of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 2H). At 10 days post-injury, a 2.5-fold increase in the expression of IL1β was noted in the injury site of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 2I).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of inflammatory markers after PBI. NFκB, RANTES and IL1β mRNA expressions were quantified in the injury site and the injured hemisphere after PBI. TSG+/− mice and TSG-6−/− mice were subjected to PBI and the injury site and remaining injured hemisphere were collected 1, 5 and 10 days after injury. mRNA was extracted and subjected to real-time PCR analysis for NFκB (A–C), RANTES (D–F) and IL1β (G–I) mRNA expression. * = p ≤ 0.05 comparing TSG-6−/+ and TSG-6−/− mice

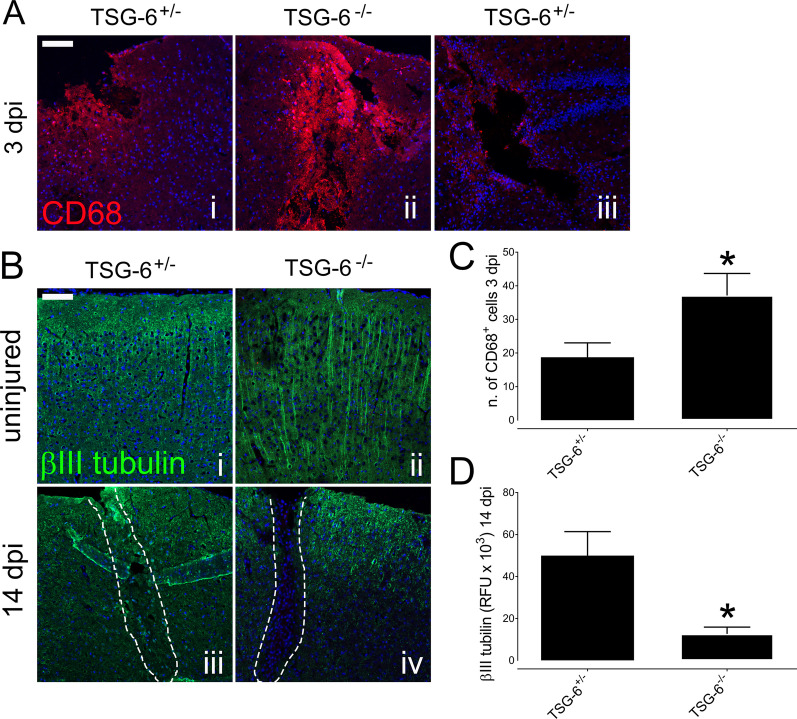

The effect of TSG-6 on the activation of microglia and infiltration of macrophages into the injury site after PBI

In order to assess the inflammatory response in Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice, we also evaluated the number of CD68+ cells present within the injury site at 3 days post-injury (Fig. 3A, C). CD68 is routinely used as a marker for macrophages and activated microglia. There was a significant increase in the number of CD68+ cells in and around the injury site of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 3A panels i and ii). Importantly, even when analyzing deeper regions of the injury site of Tsg-6+/− mice, the level of CD68+ cell infiltration was not as intense as that observed in Tsg-6−/− mice (Fig. 3A panel iii). The combined number of CD68+ cells in the injury site and within a range of 100 μm from the wound edge was counted from images obtained from 2 different sections from at least 5 mice from each experimental point (Fig. 3C). A two fold increase in CD68+ cells was found in Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of inflammatory cell infiltration and neuronal cell loss after PBI. The distribution of macrophages and activated microglia was evaluated within the injury site of TSG+/− and TSG-6−/− mice 3 days post-injury (dpi) by anti-CD68 immunostaining (red) (A). Neuronal cells were immunostained with anti-β III tubulin (green) in the equivalent area of uninjured TSG+/− (i) and TSG-6−/− (ii) mice and within the injury site of TSG-6−/+ (iii) and TSG-6−/− (iv) mice 14 days post-injury (dpi). The number of CD68+ cells was counted in the injury site and within 100 μm of the wound edge of TSG-6−/+ and TSG-6−/− mice 3 days post-injury (C). The relative fluorescent units (RFU) of anti-β III tubulin staining were quantified in and around the injury site of TSG-6−/+ and TSG-6−/− mice 14 days post-injury (D). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar represents 100 μm. * = p ≤ 0.05 comparing TSG-6−/+ and TSG-6−/− mice

Correlation between increased inflammatory response and neuronal damage

In order to verify whether the increased inflammatory response observed in Tsg-6−/− mice correlates with neuronal loss, the distribution of neurons in and around the injury site was analyzed in Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice 14 days post-injury (Fig. 3B). For such, β III tubulin was used as a tissue-specific marker for identifying neurons within injured and non-injured brains. The distribution of β III tubulin can be seen in the equivalent region of uninjured Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 3 B panels i and ii). A significant increase in the area devoid of β III tubulin staining can be observed in and around the injury site of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice 14 days post-injury (Fig. 3B iii and iv). The relative fluorescence units (RLU) were quantified from an image of the injury site captured from at least 3 mice per experimental point. There was a fourfold decrease in β III tubulin staining in and around the injury site of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice 14 days post-injury (Fig. 3D).

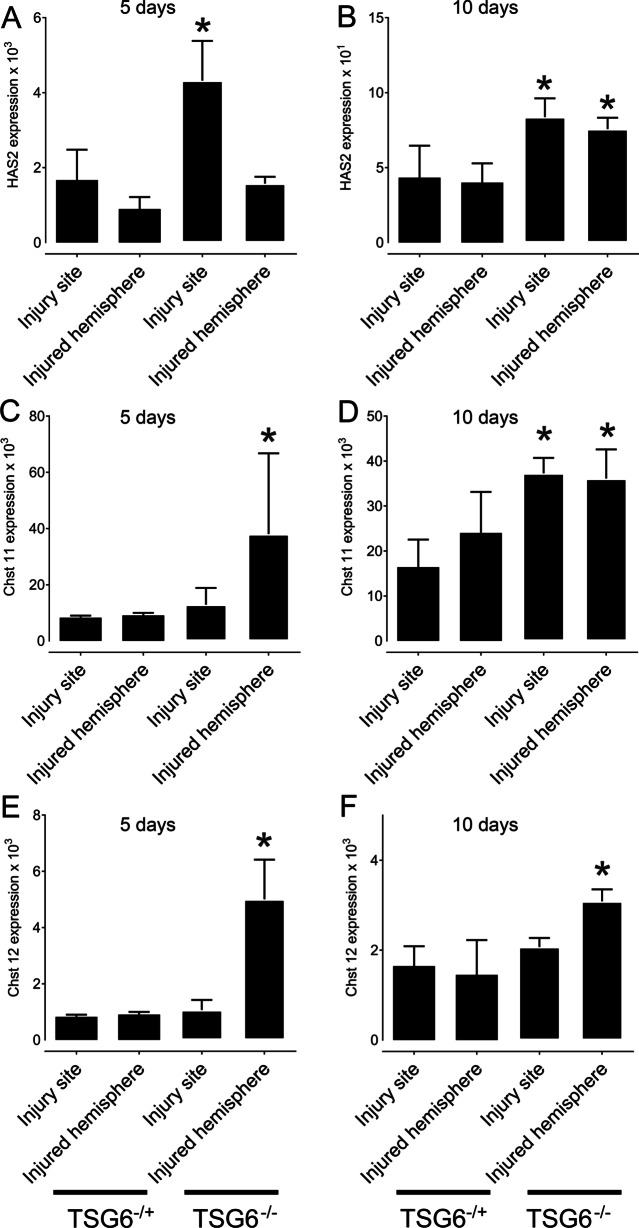

The effect of TSG-6 on the secretion of glial scar components after PBI

We also evaluated glial scar secretion within the injury site and injured hemisphere by evaluating the expression levels of the biosynthetic enzymes responsible for HA and CS chain elongation, specifically hyaluronan synthase 2 (Has2), carbohydrate (chondroitin 4) sulfotransferase (chst 11) and carbohydrate (chondroitin 4) sulfotransferase 12 (chst 12) (Fig. 4). Has2 expression increased in the injury site when compared to the remaining injured hemisphere 5 days post injury in both Tsg-6+/− and Tsg-6−/− mice, confirming the numerous previously published reports showing that HA is an integral component of the glial scar [17, 66–68]. Interestingly, there was a twofold increase in Has2 expression in the injury site of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice 5 days after injury, indicating that there is a higher rate of glial scar production in Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 4A). At 10 days post-injury, Has2 expression was still increased by twofold in Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice, but at this time point there was also an increase in Has2 expression in the remaining injured hemisphere of Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 4B). Thus, at 10 days after injury, in Tsg-6−/− mice, the expression of glial scar components was no longer limited to the injury site, but was also present within the remaining injured hemisphere. Interestingly, this was also true for the expression of Chst11 and Chst12, which showed a five fold and four fold increase, respectively, within the injured hemisphere of Tsg-6−/− mice at 5 days post injury when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 4C, E). The increase in Chst11 and Chst12, in both the injury site and injured hemisphere, was maintained through to 10 days post-injury (Fig. 4D, F).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of glial scar extracellular matrix components after PBI. HAS2, Chst 11 and Chst 12 mRNA expression levels were quantified in the injury site and the injured hemisphere after PBI. TSG+/− and TSG-6−/− mice were subjected to PBI, and the injury site and remaining injured hemisphere were collected 5 and 10 days after injury. mRNA was extracted and subjected to real-time PCR analysis for HAS2 (A, B), Chst11 (C, D) and Chst 12 (E, F) mRNA expression. * = p ≤ 0.05 comparing TSG-6−/+ and TSG-6−/− mice

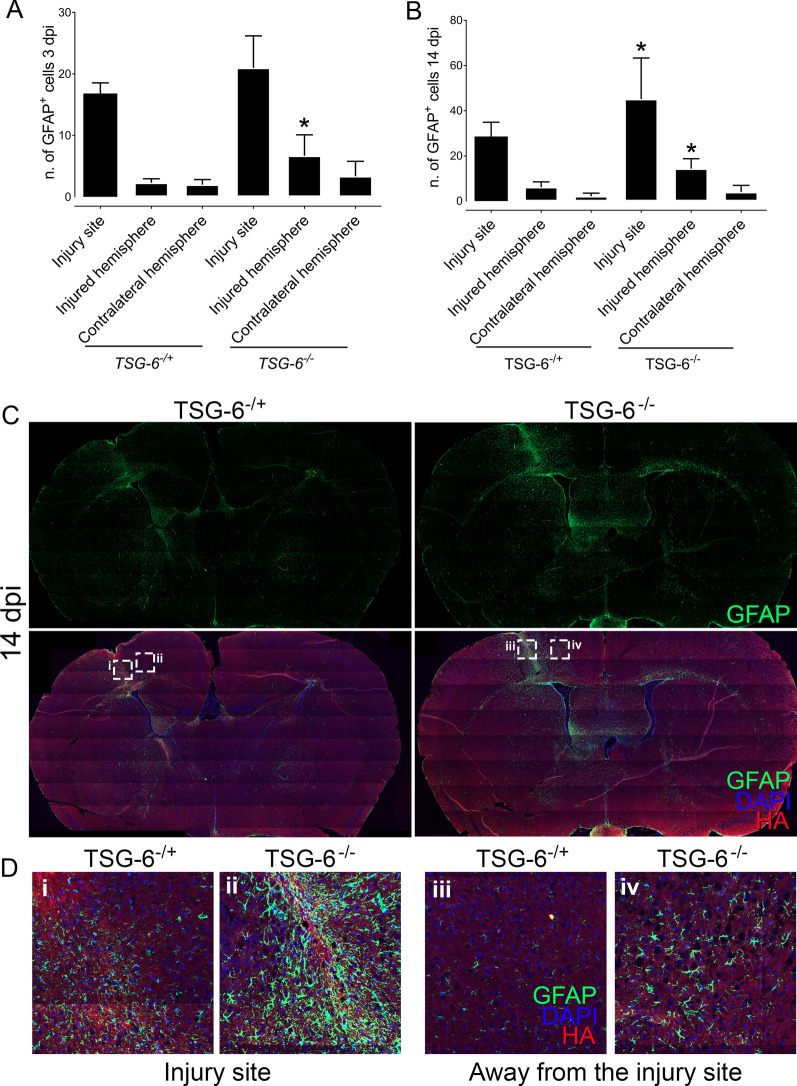

The effect of TSG-6 on astrocyte activation and recruitment after PBI

In order to further investigate the process of astrogliosis in Tsg-6+/− and Tsg-6−/− mice, injured brains were harvested and processed for histology. Sections were stained for GFAP in order to assess the distribution of astrocytes in and around the injury site, and, also, throughout the remaining brain tissue. The number of astrocytes (GFAP+ cells) was counted within the injury site, throughout the injured hemisphere, and, also, throughout the contralateral hemisphere 3 and 14 days post-injury (Fig. 5A, B). At 3 and 14 days post-injury there was a significant increase in the number of astrocytes within the injury site when compared to the injured hemisphere and contralateral hemisphere in both Tsg-6+/− and Tsg-6−/− mice. At 3 days post-injury there was no significant difference between the number of astrocytes within the injury site between Tsg-6+/− and Tsg-6−/− mice; however, there was a significant increase in the number of astrocytes within the injured hemisphere in Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 5A). At 14 days post-injury there was a significant increase in the number of astrocytes within the injury site and injured hemisphere in Tsg-6−/− mice when compared to Tsg-6+/− mice (Fig. 5B, D). The increase in astrocytes can be seen beyond the injury site in Tsg-6−/− mice (Fig. 5C, D panel iv).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of astrocyte activation and recruitment after PBI. Brain sections from TSG-6+/− and TSG-6−/− mice were analyzed by immunofluorescence. Astrocytes were identified with anti-GFAP (green) and the glial scar with HABP (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Z-stacks were captured of the entire brain section using the tilling mode, and images were stitched together using Zen software. Thereafter, the number of astrocytes was counted within the injury site, within the injured hemisphere and in the contralateral hemisphere of brains 3 (A) and 14 dpi (B) in a double blinded manner. The distribution of astrocytes throughout the brain sections shows that in TSG-6−/− mice the increase in astrocytes is not restricted to the injury site (C). Magnified images of the areas demarcated in (C) can be seen in (D). At least 3 mice were analyzed per genotype for each time point. * = p ≤ 0.05 comparing TSG+/− and TSG-6−/− mice

Discussion

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) are well established as major extracellular matrix components in the central nervous system [69]. Over a decade ago, Silver et al. identified that CSPGs within the glial scar inhibit axonal growth, and this triggered a great deal of interest in targeting CS within the scar tissue as a means to promote axonal regeneration [32, 70–72]. Over the years, strategies utilizing the enzymes chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) and ChAC have been used to remove the CS component of the glial scar as a means to promote axonal growth and regeneration [50, 73–77]. Many studies have shown that specifically removing CS within the glial scar is enough for axons to grow across the injury site [32, 70, 78, 79]. However, significant regeneration was never observed in these studies, and many groups found limited or no improvement after targeting CS within the glial scar [70]. One unique characteristic of TSG-6 is its known ability to bind to a number of ligands including HA, CS and core proteins of proteoglycans (i.e. versican and aggrecan), forming specific HA/HC/TSG-6 and/or CS/HA/HC/TSG-6 matrices with immunosuppressive characteristics [61, 80–84]. Our previous study suggests these HA/HC/TSG-6 matrices are also present within the glial scar [48]. Therefore, given that TSG-6 directly binds to both HA and CS to form specific anti-inflammatory matrices, the ChABC and ChAC treatments used over the years to target the glial scar as a means to promote regeneration would also have removed TSG-6, a known anti-inflammatory molecule that is also a component of the glial scar [82]. The loss of TSG-6 by these treatments could, in part, explain why significant functional recovery was never obtained after ChABC and/or ChAC treatments.

To explore the role of TSG-6 in TBI, specifically in astrogliosis, we compared the differences in injury outcomes in Tsg-6−/− and Tsg-6+/− mice after PBIs. Our data show an increase in TSG-6 expression in the injured hemisphere of Tsg-6+/− mice after TBI. This increase in expression of TSG-6 after CNS insults supports our earlier findings in a rat model that astrocytes secrete high levels of TSG-6 upon injury, which aids in the formation of a specialized HA/HC/TSG-6 matrix as part of an inflammatory response [48]. Since TSG-6 is known for having anti-inflammatory properties, to further study whether high levels of TSG-6 serve a purpose of rapidly suppressing inflammation after injury, we performed similar penetrating injuries in Tsg-6−/− mice. We used immunofluorescence and RNA expression analyses of inflammatory and glial scar markers to elucidate the outcome during the acute phase and chronic phase of TBI. During the acute phase after injury, the observed increase in astrocyte activation, inflammatory cell infiltration and expression of inflammatory cytokines in Tsg-6−/− mice indicate that the loss of TSG-6 results in a greater inflammatory response. Moreover, during the chronic phase of injury, unrestricted inflammatory response was observed throughout the injured hemisphere and was not limited to the injury site, as is seen after normal glial scar formation. Thus, injured Tsg-6−/− mice appear to experience more severe tissue damage than their Tsg-6+/− counterpart, both within and around the injury site. Thus, the loss of TSG-6 allows the damage to spread from the injury site to neighboring healthy tissues. We postulate that the cause of such widespread damage is due to the lack of the specialized HA-TSG6 or HA/HC/TSG-6 matrix, which could possibly serve to stabilize the glial scar and form an immunosuppressive environment, thereby protecting adjacent tissue from further damage. This hypothesis is further supported by the increase in CSPG and HA biosynthesis, both glial scar components, in Tsg-6−/− mice. Specifically, these mice show increased Has2, Chst11 and Chst12 expression levels in tissues collected after the onset of glial scarring, and, also, during the chronic phase of astrogliosis, indicating an increase in scar tissue formation. This increase in expression was not only observed at the injury site, but also throughout the whole injured hemisphere, suggesting that the tissue damage spreads beyond the injury site in the absence of TSG-6. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the loss of TSG-6 leads to a more severe inflammatory response and, consequently, increased scarring after TBI. Thus, our results support the hypothesis put forward by many groups over the past decade that preventing the formation of the glial scar leads to inflammation and damage beyond the injury site. We also provide experimental evidence that shows that the glial scar functions to restrict the damage to the injury site. Importantly, these findings should be taken into account when attempts are made to disrupt the glial scar as a means to promote neuronal regeneration, since preventing formation of the glial scar may not have the beneficial outcomes as previously presumed.

Conclusion

Our results show that TSG-6 has an anti-inflammatory role in the glial scar. Our study further supports the hypothesis that the glial scar forms a protective border surrounding the injury site thereby preventing the spread of inflammation and damage beyond the injury site.

Methods

TSG6 null (TSG6−/−) or heterozygous (TSG6+/−) mice and animal maintenance

Transgenic Tsg-6 null mice (Tnfip6Δ/Δ), herein referred to as Tsg-6−/− mice, and heterozygous mice, herein referred to as Tsg-6+/− mice, were maintained as previously described [56]. Our previously published work demonstrated that Tsg-6+/− mice present a similar distribution of astrocytes throughout the brain to wild-type (wt) mice [48]. Moreover, Tsg-6+/− mice have previously been shown not to display a phenotype and present similar TSG-6 expression levels as wt mice, and were therefore used as littermate controls in our study [56]. Experimental procedures for handling the mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), University of Houston under protocol 16-036.

Brain injury

Mice (7 to 8 weeks old) were anesthetized with ketamine (80–100 mg/kg—Vedco INC, Catalog# 07-890-8598) and xylazine (5–10 mg/kg, Akorn INC, Catalog# 07-808-1947) by IP injection and allowed to go into full anesthetic state. A sterile surgical drill (Precision Tools, Model Craft PPV2237) was used to make a hole of approximately 1.5 mm in diameter in the skull over the right frontal cortex at the stereotaxic coordinates AP: 1.0 mm, ML: 1.5 mm, and DV: 1.5 mm, according to Franklin and Paxinos (85). A 30-gauge needle (Exel, Catalog# 26437) was then used to make a puncture wound at a depth of 2 mm. After injury, the skin at the surgical site was closed with two sutures. The area was then cleaned with 70% ethanol, and mice were placed on a heating pad and monitored until they regained consciousness prior to being transferred to a clean cage. All surgeries were carried out at the same time of day to minimize bias. Mice were monitored daily and did not show any decrease in weight ≥ 15% when compared to their pre-surgical weight. Mice were euthanized, as outlined below, at 1, 3 and 5 days post injury to study the acute effects of brain injury, and at 10 and 14 days to study long-term/chronic effects. Five mice per experimental group were used for the real-time PCR analysis and at least seven mice per experimental group were used for immunofluorescence analysis.

Perfusion fixation and brain tissue processing

Brain samples were collected at 1, 3, 5, 10, and 14 days post injury for immunofluorescence analyses. Briefly, mice were initially injected with a lethal dose of combined anesthetics containing 200 mg of ketamine and 40 mg xylazine. Final dosage received was 3 mg of ketamine and 0.6 mg of xylazine per mouse. Once mice were under deep anesthesia, abdominal and thoracic excisions were performed to expose the heart, which was used to perfuse 2% formalin (Fisher Scientific, Catalog# SF100-4) throughout the whole body via a gravity-driven flow system for whole body fixation. Subsequently, the brain was isolated from the skull and further immerse fixed for 2 days in 2% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Catalog# 15710). For cryosection processing, brains were immersed in 30% sucrose for 2 days, embedded in OCT embedding medium (Fisher Healthcare, Catalog# 4585) and frozen. Sections 10 μm thick were obtained, mounted on superfrost slides (VWR, Catalog# 48311-703) and stored at − 20 °C until use.

Immunofluorescence

Upon use, the slides were heated at 65 °C for 30 min and, subsequently, sections were washed with PBS to remove tissue freezing medium. Sections were then treated with 0.1% glycine (Fisher Chemical, Catalog# G46-500), blocked with 5% FBS (Seradigm, Catalog# 3100-500) and permeabilized with 0.1% saponin prepared in PBS. Sections were then incubated with the primary antibodies anti-Tenascin (Abcam, Ab108930), anti-GFAP (Abcam, Ab4647), anti-CD68 (Abcam, Ab31630) and anti-β III tubulin (Covance, PRB-435P-100). Sections were washed and incubated with appropriate secondary donkey antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488 (Life Technologies) or Alexa Fluor® 555 (Life Technologies) for one hour at 18 °C. For HA staining, tissues were incubated with biotinylated HA binding protein (385911, Millipore) followed by NeutrAvidin®Alexa 555 (Life Technologies). The tissues were then washed and nuclei stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich). Sections were mounted in Prolong®Gold (Molecular Probes) and imaged using a ZEISS LSM 800 Confocal microscope with Airyscan. Secondary controls were done with a goat IgG isotype control (ab37388; Abcam) in place of the primary antibody and did not yield any significant staining (results not shown). For imaging, multiple z-stack tiles were captured of entire brain sections and frames were processed together into a single image (using the stitching mode followed by full orthogonal projection) using Zen Software (Zeiss). The number of GFAP+ and CD68+ cells in and around the injury site were counted by two independent investigators in a blinded manner and the relative Fluorescent intensity was measured using the Zen Software (Zeiss). At least 2 sections were scanned and analyzed from each animal for each set of antibodies and representative images shown in the figures.

RNA extraction from brains and real-time PCR analysis

Brains collected from injured mice at 1, 5 and 10 days post injury were used for RNA extraction. At least 5 mice were used per experimental group and each animal was analyzed separately. Briefly, mice were euthanized and brain tissue was immediately isolated from each mouse. Injury sites (A samples) were dissected from the rest of the injured right hemisphere, transferred into a labeled Eppendorf tube and immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen. The remaining right hemisphere brain tissue (B samples) from each animal was transferred into a different tube and frozen as described. The samples were kept at − 80 °C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated from these tissue samples using Trizol® Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and chloroform extraction (Sigma-Aldrich, Catalog# 650498). First strand cDNA was reverse transcribed using 1.5 to 2 μg of total RNA and the high capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, catalog# 4368814, lot 00593854), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR amplification was performed on 1 μg or 50 ng of the cDNA (1:5) using the PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems, Catalog# A25918) in a CXF Connect Real-time System from BIO-RAD, using an activation cycle of 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. A complete list of primers used in this study is shown in Table 1. Gene expression levels were normalized against Actb and Gapdh using the 2−ΔCt and/or 2−ΔΔCt methods.

Table 1.

Primers used for real time PCR analysis

| Gene (Mus musculus) | Accession number | Forward (5’ → 3’) | Reverse (5’ → 3’) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tenascin C (tnc) | NM_011607.3 | CCAGGGTTGCCACCTATTT | GTCTAGAGGATCCCACTCTACTT |

| Gfap | NM_001131020.1 | AACAACCTGGCTGCGTATAG | TCTCGAACTTCCTCCTCATAGAT |

| Tsg-6 /Tnfaip6 | NM_009398.2 | CCCACATGCAAAGGAGTGTG | TGAGCCGAATGTGCCAGTAG |

| Chst1 | NM_021439.2 | CACCCAGTCATGCGGAGGAA | GCAGGATGGCAGTGTTGGAT |

| Chst12 | NM_021528.3 | GAGCTGGAGAACGAAGAGTTT | CAGGAGGTACTGGATGAAGTTG |

| IL1β | NM_008361.4 | GTGCAAGTGTCTGAAGCAGC | CTCATCACTGTCAAAAGGTGGC |

| Cspg4 | NM_139001.2 | TCTACAGCTCCTGCCTCCTT | ATGTGGAGAACTGGAGCAGC |

| Ccl5 (Rantes) | NM_013653.3 | CCTCACCATATGGCTCGGAC | ACGACTGCAAGATTGGAGCA |

| Nfkb1 | NM_008689.2 | GTCACCCATGGCACCATAAA | CCTTCACCTTCAGTTTCCTTCTC |

| Has1 | NM_008215.2 | CTA TGC TAC CAA GTA TAC CTC G | TCT CGG AAG TAA GAT TTG GAC |

| Has2 | NM_008216.3 | CGG TCG TCT CAA ATT CAT CTG | ACA ATG CAT CTT GTT CAG CTC |

| Has 3 | NM_008217.4 | GAT GTC CAA ATC CTC AAC AAG | CCC ACT AAT ACA TTG CAC AC |

| Itih1 | CCA CCC CAT CGG TTT TGA AGT GTC T | TGC CAC GGG TCC TTG CTG TAG TCT | |

| Itih2 | ATG AAA AGA CTC ACG TGC TTT TTC | ATT TGC CTG GGG CCA GT | |

| Itih3 | TGA GGA GGT GGC CAA CCC ACT | CGC TTC TCC AGC AGC TGC TC | |

| Actb | NM_007393.5 | CACTGTCGAGTCGCGTCC | TCATCCATGGCGAACTGGTG |

| Gapdh | NM_001289726.1 | AACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTC | CCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATT |

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean. The difference between the two groups was compared by means of the Student’s t-test. p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism version 7 software package (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). * was used to indicate statistical differences of ≤ 0.05. Unless indicated otherwise, * indicates the statistical difference of Tsg-6−/− mice compared to Tsg-6+/− mice for each time point.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Denise Lerma, Nicole Grimmes and Garrett Elliot who contributed in the early stages of the study. The authors are in debt to Tarsis F. Gesteira and Yvette May Coulson- Thomas for their invaluable discussions and suggestions throughout the study. Transgenic Tsg-6 null mice (Tnfip6Δ/Δ) were kindly provided by Dr. Mark Lauer.

Abbreviations

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- TSG-6

TNF-stimulated gene-6

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- VIM

Vimentin

- CSPGs

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of Transcription 3

- HA

Hyaluronan

- GAGs

Glycosaminoglycans

- CNS

Central nervous system

- HC

Heavy chain

- ITI or IαI

Inter-alpha inhibitor

- hUMSCs

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

- PTX3

Pentraxin-3

- NFKB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer

- IL1β

Interleukin 1 beta

- Ccl5

Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 1 or Rantes

- HAS

Hyaluronan synthase

- Chst

Carbohydrate (chondroitin 4) sulfotransferase

Authors' contributions

VH and VJCT generated the hypothesis and experimental design. VJCT, KNM and MS contributed to the experimental design. KNM, MS, AN and VJCT conducted the experiments and helped with the data analysis. KNM and VJCT wrote the manuscript. KNM, MS, AN, SP, VH and VCT read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by start-up funds from the University of Houston to VJCT, The Mizutani Foundation grant to VJCT and the National Institute of Health/National Eye Institute R01 EY029289 to VJCT and Core grant P30 EY07551.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Experimental procedures for handling the mice and animal care were in accordance to regulations of the National Institute of Health and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Houston under protocols 16-025, 16-035, 16-036, 16-044.

Consent to publish

The authors grant their consent to publish the material presented herein.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hyder AA, Wunderlich CA, Puvanachandra P, Gururaj G, Kobusingye OC. The impact of traumatic brain injuries: a global perspective. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22:341–353. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2007-22502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bose P, Hou J, Thompson FJ. Traumatic brain injury (TBI)-induced spasticity: neurobiology, treatment, and rehabilitation. Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects. 2015. [PubMed]

- 3.Blennow K, Brody DL, Kochanek PM, Levin H, McKee A, Ribbers GM, et al. Traumatic brain injuries. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2016;2:1–19. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham DI, Mcintosh TK, Maxwell WL, Nicoll JAR. Recent advances in neurotrauma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:641–651. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.8.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaninotto ALC, Costa BT, Ferreira IS, French M, Paiva WS, Fregni F. Traumatic brain injury. In: Neuromethods. 2018.

- 6.Burda JE, Bernstein AM, Sofroniew MV. Astrocyte roles in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2016;275:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gugliandolo E, D’Amico R, Cordaro M, Fusco R, Siracusa R, Crupi R, et al. Neuroprotective effect of artesunate in experimental model of traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol. 2018;9:590. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovacs SK, Leonessa F, Ling GSF. Blast TBI models, neuropathology, and implications for seizure risk. Front Neurol. 2014;5:47. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharp DJ, Scott G, Leech R. Network dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:156–166. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fakhran S, Alhilali L. Neurodegenerative changes after mild traumatic brain injury. In: Concussion. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Nagahiro S, Mizobuchi Y. Current topics in sports-related head injuries: a review. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Jordan BD. The clinical spectrum of sport-related traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:222–230. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costanza A, Weber K, Gandy S, Bouras C, Hof PR, Giannakopoulos P, et al. Review: contact sport-related chronic traumatic encephalopathy in the elderly: clinical expression and structural substrates. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;27:570–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAllister T, McCrea M. Long-term cognitive and neuropsychiatric consequences of repetitive concussion and head-impact exposure. J Athl Train. 2017;52:309–317. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:7–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sofroniew MV. Astrogliosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a020420. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George N, Geller HM. Extracellular matrix and traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2018;96:573–588. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siracusa R, Fusco R, Cuzzocrea S. Astrocytes: role and functions in brain pathologies. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1114. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, Shao A, Yao Y, Tu S, Deng Y, Zhang J. Dual roles of astrocytes in plasticity and reconstruction after traumatic brain injury. Cell Commun Signal. 2020;18:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12964-019-0473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sofroniew MV. Reactive astrocytes in neural repair and protection. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:400–407. doi: 10.1177/1073858405278321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith PD, Coulson-Thomas VJ, Foscarin S, Kwok JCF, Fawcett JW. “GAG-ing with the neuron”: the role of glycosaminoglycan patterning in the central nervous system. Exp Neurol. 2015;274:100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGraw J, Hiebert GW, Steeves JD. Modulating astrogliosis after neurotrauma. J Neurosci Res. 2001;63:109–115. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20010115)63:2<109::AID-JNR1002>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawano H, Kimura-Kuroda J, Komuta Y, Yoshioka N, Li HP, Kawamura K, et al. Role of the lesion scar in the response to damage and repair of the central nervous system. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;349:169–180. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1336-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burda JE, Sofroniew MV. Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron. 2014;81:229–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sofroniew MV. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada S, Hara M, Kobayakawa K, Matsumoto Y, Nakashima Y. Astrocyte reactivity and astrogliosis after spinal cord injury. Neurosci Res. 2018;126:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies SJA, Goucher DR, Doller C, Silver J. Robust regeneration of adult sensory axons in degenerating white matter of the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2018;19:5810–5822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05810.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKeon RJ, Jurynec MJ, Buck CR. The chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans neurocan and phosphacan are expressed by reactive astrocytes in the chronic CNS glial scar. J Neurosci. 2018;19:10778–10788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10778.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada S, Nakamura M, Katoh H, Miyao T, Shimazaki T, Ishii K, et al. Conditional ablation of Stat3 or Socs3 discloses a dual role for reactive astrocytes after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2006;12:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitch MT, Doller C, Combs CK, Landreth GE, Silver J. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of glial scarring and progressive cavitation: In vivo and in vitro analysis of inflammation-induced secondary injury after CNS trauma. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8182–8198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08182.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogelaar CF, König B, Krafft S, Estrada V, Brazda N, Ziegler B, et al. Pharmacological suppression of CNS scarring by deferoxamine reduces lesion volume and increases regeneration in an in vitro model for astroglial-fibrotic scarring and in rat spinal cord injury in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0134371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:146–156. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galtrey CM, Fawcett JW. The role of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in regeneration and plasticity in the central nervous system. Brain Res Rev. 2007;54:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CM, Lin JW, Chen YC, Shen HH, Wei L, Yeh YS, Chiu WT. Hyaluronic acid inhibits the glial scar formation after brain damage with tissue loss in rats. Surg Neurol. 2009;72:S50–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gesteira TF, Coulson-Thomas YM, Coulson-Thomas VJ. Anti-inflammatory properties of the glial scar. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:1742. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.194710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voskuhl RR, Peterson RS, Song B, Ao Y, Morales LBJ, Tiwari-Woodruff S, et al. Reactive astrocytes form scar-like perivascular barriers to leukocytes during adaptive immune inflammation of the CNS. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11511–11522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1514-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wanner IB, Anderson MA, Song B, Levine J, Fernandez A, Gray-Thompson Z, et al. Glial scar borders are formed by newly proliferated, elongated astrocytes that interact to corral inflammatory and fibrotic cells via STAT3-dependent mechanisms after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12870–12886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2121-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faulkner JR. Reactive astrocytes protect tissue and preserve function after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2143–2155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myer DJ, Gurkoff GG, Lee SM, Hovda DA, Sofroniew MV. Essential protective roles of reactive astrocytes in traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2006;129:2761–2772. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitch MT, Silver J. CNS injury, glial scars, and inflammation: inhibitory extracellular matrices and regeneration failure. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bush TG, Puvanachandra N, Horner CH, Polito A, Ostenfeld T, Svendsen CN, et al. Leukocyte infiltration, neuronal degeneration, and neurite outgrowth after ablation of scar-forming, reactive astrocytes in adult transgenic mice. Neuron. 1999;23:297–308. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilhelmsson U. Absence of glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin prevents hypertrophy of astrocytic processes and improves post-traumatic regeneration. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5016–5021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0820-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pekny M, Johansson CB, Eliasson C, Stakeberg J, Wallén Å, Perlmann T, et al. Abnormal reaction to central nervous system injury in mice lacking glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:503–514. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pekny M. Astrocytic intermediate filaments: lessons from GFAP and vimentin knock-out mice. Prog Brain Res. 2001;132:23–30. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(01)32062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faulkner JR, Herrmann JE, Woo MJ, Tansey KE, Doan NB, Sofroniew MV. Reactive astrocytes protect tissue and preserve function after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2143–2155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrmann JE, Imura T, Song B, Qi J, Ao Y, Nguyen TK, et al. STAT3 is a critical regulator of astrogliosis and scar formation after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7231–7243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fan H, Zhang K, Shan L, Kuang F, Chen K, Zhu K, et al. Reactive astrocytes undergo M1 microglia/macrohpages-induced necroptosis in spinal cord injury. Mol Neurodegen. 2016;11:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0081-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coulson- Thomas VJ, Lauer ME, Soleman S, Zhao C, Hascall VC, Day AJ, et al. TSG-6 is constitutively expressed in adult CNS and associated with astrocyte-mediated glial scar formation following spinal cord injury. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:19939–19952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Milner CM, Day AJ. TSG-6: a multifunctional protein associated with inflammation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(10):1863–1873. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bradbury EJ, Moon LDF, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, et al. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002;416:636–640. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Massey JM, Hubscher CH, Wagoner MR, Decker JA, Amps J, Silver J, et al. Chondroitinase ABC digestion of the perineuronal net promotes functional collateral sprouting in the cuneate nucleus after cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4406–4414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5467-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carrette O, Nemade RV, Day AJ, Brickner A, Larsen WJ. TSG-6 is concentrated in the extracellular matrix of mouse cumulus oocyte complexes through hyaluronan and inter-alpha-inhibitor binding. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:301–308. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salustri A, Yanagishita M, Hascall VC. Synthesis and accumulation of hyaluronic acid and proteoglycans in the mouse cumulus cell-oocyte complex during follicle-stimulating hormone-induced mucification. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13840–13847. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)80077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salustri A, Yanagishita M, Underhill CB, Laurent TC, Hascall VC. Localization and synthesis of hyaluronic acid in the cumulus cells and mural granulosa cells of the preovulatory follicle. Dev Biol. 1992;151:541–551. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90192-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Camaioni A, Hascall VC, Yanagishita M, Salustri A. Effects of exogenous hyaluronic acid and serum on matrix organization and stability in the mouse cumulus cell-oocyte complex. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20473–20481. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(20)80750-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fulop C. Impaired cumulus mucification and female sterility in tumor necrosis factor-induced protein-6 deficient mice. Development. 2003;130:2253–2261. doi: 10.1242/dev.00422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stober VP, Johnson CG, Majors A, Lauer ME, Cali V, Midura RJ, et al. TNF-stimulated gene 6 promotes formation of hyaluronan-inter-α-inhibitor heavy chain complexes necessary for ozoneinduced airway hyperresponsiveness. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:20845–20858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.756627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lauer ME, Glant TT, Mikecz K, DeAngelis PL, Haller FM, Husni ME, et al. Irreversible heavy chain transfer to hyaluronan oligosaccharides by tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:205–214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.403998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Petrey AC, De La Motte CA. Thrombin cleavage of inter-α-inhibitor heavy chain 1 regulates leukocyte binding to an inflammatory hyaluronan matrix. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:24324–24334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.755660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hill DR, Rho HK, Kessler SP, Amin R, Homer CR, McDonald C, et al. Human milk hyaluronan enhances innate defense of the intestinal epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:29090–29104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.468629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baranova NS, Foulcer SJ, Briggs DC, Tilakaratna V, Enghild JJ, Milner CM, et al. Inter-α-inhibitor impairs TSG-6-induced hyaluronan cross-linking. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:29642–29653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.477422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kessler SP, Obery DR, De La Motte C. Hyaluronan synthase 3 null mice exhibit decreased intestinal inflammation and tissue damage in the DSS-induced colitis model. Int J Cell Biol. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Lim Y, Bendelja K, Opal SM, Siryaporn E, Hixson DC, Palardy JE. Correlation between mortality and the levels of inter-alpha inhibitors in the plasma of patients with severe sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:919–926. doi: 10.1086/377642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmidt EP, Overdier KH, Sun X, Lin L, Liu X, Yang Y, et al. Urinary glycosaminoglycans predict outcomes in septic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:439–449. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201511-2281OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coulson-Thomas VJ, Gesteira TF, Hascall V, Kao W. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells suppress host rejection: the role of the glycocalyx. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:23465–23481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.557447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.ˇ Olté LS, Mendichi R, Kogan G, Schiller J, Stankovská M, Arnhold J. Degradative action of reactive oxygen species on hyaluronan. 2006; Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Wight TN. Provisional matrix: a role for versican and hyaluronan [Internet]. Vols. 60–61, Matrix Biology. Elsevier B.V.; 2017 [cited 2021 Jan 15]. p. 38–56. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5438907/?report=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Cicanic M, Sykova E, Vargova L. Bral1: “Superglue” for the extracellular matrix in the brain white matter. Int J Biochem Cell. 2012;44:596–599. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dyck SM, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans: Key modulators in the developing and pathologic central nervous system. Exp Neurol. 2015;269:169–187. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McKeon RJ, Höke A, Silver J. Injury-induced proteoglycans inhibit the potential for laminin-mediated axon growth on astrocytic scars. Exp Neurol. 1995;136:32–43. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bradbury EJ, Carter LM. Manipulating the glial scar: chondroitinase ABC as a therapy for spinal cord injury. Brain Res Bull. 2011;84:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McKeon RJ, Schreiber RC, Rudge JS, Silver J. Reduction of neurite outgrowth in a model of glial scarring following CNS injury is correlated with the expression of inhibitory molecules on reactive astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3398–3411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03398.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Foerster AP. Spontaneous regeneration of cut axons in adult rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1982;210(4):335–356. doi: 10.1002/cne.902100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brückner G, Bringmann A, Härtig W, Köppe G, Delpech B, Brauer K. Acute and long-lasting changes in extracellular-matrix chondroitin-sulphate proteoglycans induced by injection of chondroitinase ABC in the adult rat brain. Exp Brain Res. 1998;121(3):300–310. doi: 10.1007/s002210050463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Filous AR, Miller JH, Coulson-Thomas YM, Horn KP, Alilain WJ, Silver J. Immature astrocytes promote CNS axonal regeneration when combined with chondroitinase ABC. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70(12):826–841. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moon LDF, Asher RA, Rhodes KE, Fawcett JW. Regeneration of CNS axons back to their target following treatment of adult rat brain with chondroitinase ABC. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:465–466. doi: 10.1038/87415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Elkin BS, Shaik MA, Morrison B. Chondroitinase ABC reduces brain tissue swelling in vitro. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(11):2277–2285. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Busch SA, Silver J. The role of extracellular matrix in CNS regeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klapka N, Hermanns S, Straten G, Masanneck C, Duis S, Hamers FPT, et al. Suppression of fibrous scarring in spinal cord injury of rat promotes long-distance regeneration of corticospinal tract axons, rescue of primary motoneurons in somatosensory cortex and significant functional recovery. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:3047–3058. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Milner CM, Tongsoongnoen W, Rugg MS, Day AJ. The molecular basis of inter-α-inhibitor heavy chain transfer on to hyaluronan: Figure 1. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:672–676. doi: 10.1042/BST0350672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Getting SJ, Mahoney DJ, Cao T, Rugg MS, Fries E, Milner CM, et al. The link module from human TSG-6 inhibits neutrophil migration in a hyaluronan- and inter-α-inhibitor-independent manner. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:51068–51076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baranova NS, Nilebäck E, Haller FM, Briggs DC, Svedhem S, Day AJ, et al. The inflammation-associated protein TSG-6 cross-links hyaluronan via hyaluronan-induced TSG-6 oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25675–25686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.247395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Higman VA, Briggs DC, Mahoney DJ, Blundell CD, Sattelle BM, Dyer DP, et al. A refined model for the TSG-6 link module in complex with hyaluronan: use of defined oligosaccharides to probe structure and function. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:5619–5634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.542357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martin J, Midgley A, Meran S, Woods E, Bowen T, Phillips AO, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene 6 (TSG-6)-mediated interactions with the inter-α-inhibitor heavy chain 5 facilitate tumor growth factor β1 (TGFβ1)-dependent fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:13789–13801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.670521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates (map) Boston: Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.