Abstract

Tissue-resident innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) help sustain barrier function and respond to local signals. ILCs are traditionally classified as ILC1, ILC2 or ILC3 on the basis of their expression of specific transcription factors and cytokines [1]. In the skin, disease-specific production of ILC3-associated cytokines interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-22 in response to IL-23 signalling contributes to dermal inflammation in psoriasis. However, it is not known whether this response is initiated by pre-committed ILCs or by cell-state transitions. Here we show that the induction of psoriasis in mice by IL-23 or imiquimod reconfigures a spectrum of skin ILCs, which converge on a pathogenic ILC3-like state. Tissue-resident ILCs were necessary and sufficient, in the absence of circulatory ILCs, to drive pathology. Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) profiles of skin ILCs along a time course of psoriatic inflammation formed a dense transcriptional continuum —even at steady state—reflecting fluid ILC states, including a naive or quiescent-like state and an ILC2 effector state. Upon disease induction, the continuum shifted rapidly to span a mixed, ILC3-like subset also expressing cytokines characteristic of ILC2s, which we inferred as arising through multiple trajectories. We confirmed the transition potential of quiescent-like and ILC2 states using in vitro experiments, single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (scATAC-seq) and in vivo fate mapping. Our results highlight the range and flexibility of skin ILC responses, suggesting that immune activities primed in healthy tissues dynamically adapt to provocations and, left unchecked, drive pathological remodelling.

Main

In healthy individuals, most effector skin ILCs are ILC2s [2, 3], producing cytokines IL-5 and IL-13. ILC3s occur in human and mouse psoriatic skin [4, 5, 6], and their numbers decrease in response to therapeutic compounds [5], suggesting that they contribute to pathogenesis. It remains unknown how and when the numbers of ILC2s and ILC3s shift during disease progression. Some reports indicate that ILCs may switch or mix effector programs [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14], but it is unknown whether ILC3s increase in psoriatic inflammation by expansion [15, 16], by conversion of ILC2s, by differentiation of tissue-resident ILC progenitors [17, 18], by recruitment of circulating cells [19, 20, 21], or by a combination of these mechanisms.

Skin ILCs initiate inflammatory response

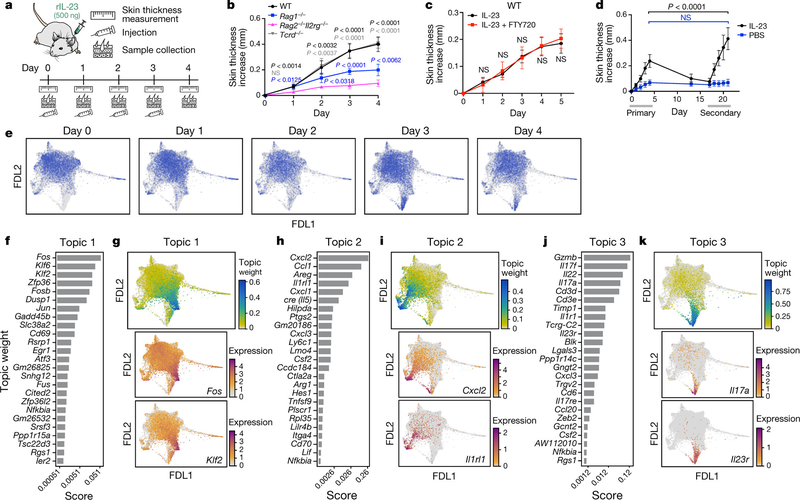

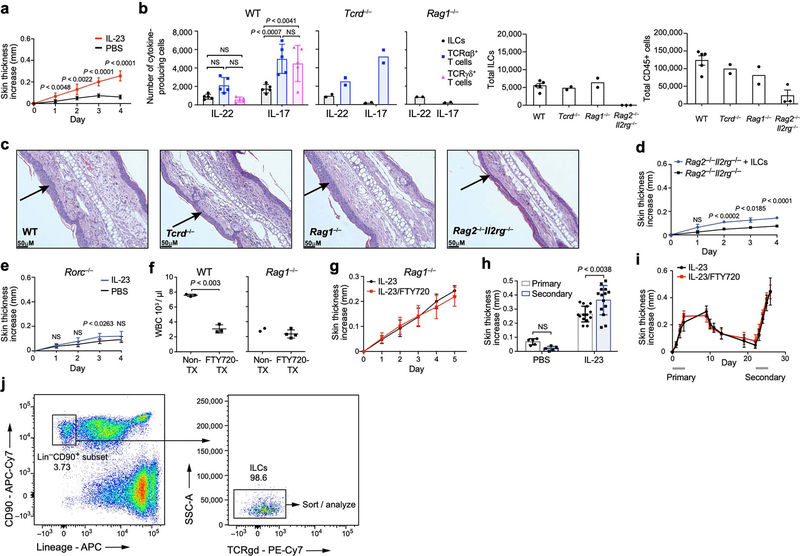

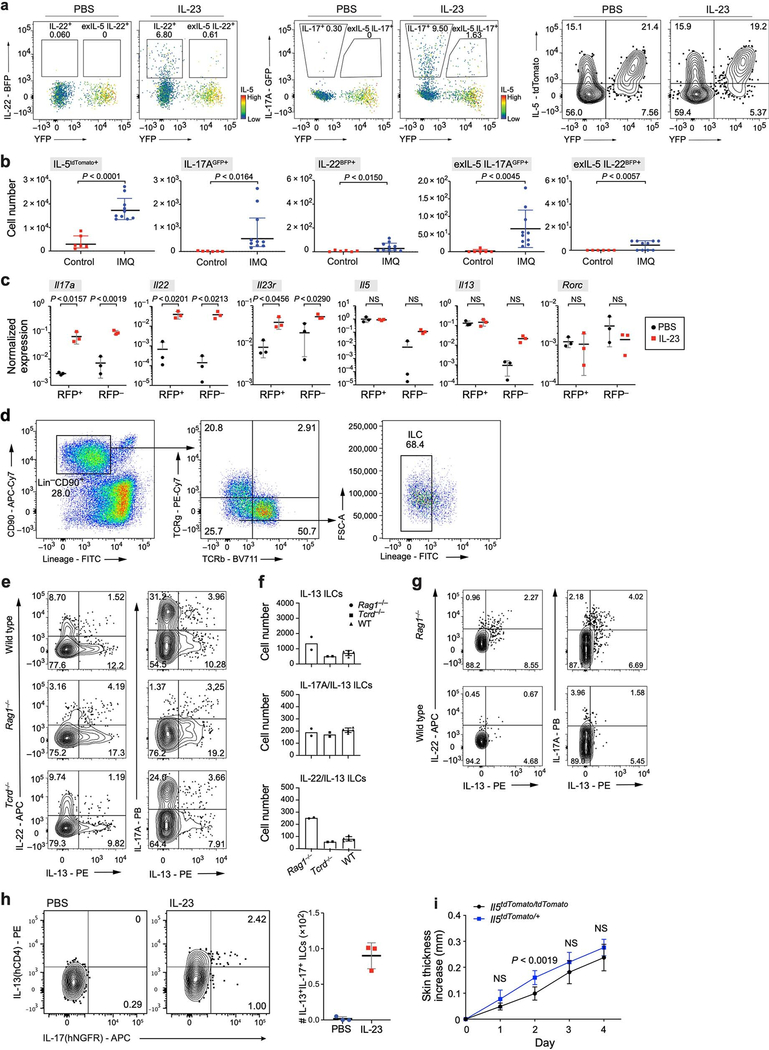

We used a mouse model of psoriasis, with subcutaneous injection of IL-23—a crucial signal and therapeutic target [22]—leading to inflammation and skin thickening (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1a). Whereas in the absence of all lymphocytes (in Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice), the response was minor and probably the result of tissue injury, there was a marked response in mice with ILCs but deficient in T cells and B cells (Rag1−/− mice) (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1b, c). IL-17A expression was lower in Rag1−/− mice than in wild-type mice, suggesting that T cells provide additional cues. γδ T cells are implicated in longer-term disease models [6, 23], but mice lacking γδ T cells (Tcrd−/−) responded similarly to the wild-type mice in our model (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1b). Furthermore, skin ILCs adoptively transferred from untreated wild-type mice into Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice conferred significant IL-23-induced skin thickening (Extended Data Fig. 1d). This response required RORγ, a master regulator of ILC3s, T helper 17 (TH17) cells and γδ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 1e). Thus, ILCs were sufficient to drive a psoriatic response to IL-23.

Fig. 1: Skin ILCs drive IL-23–induced pathology.

a, Study overview. rIL-23, recombinant IL-23. b–d, Tissue-resident ILCs are sufficient to drive IL-23–induced inflammation. Increase in skin thickness over time in wild-type (WT) (black), Rag1−/− (blue), Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− (magenta) and Tcrd−/− (grey) mice (b; n = 7 mice per group, 2 independent experiments), wild-type mice with (red) and without (black) FTY720 treatment (c; n = 6 mice per group, no significant difference), and wild-type mice during primary and secondary IL-23 challenge (black) (n = 8 mice) or saline control (blue) (PBS) (d; n = 5 mice, 2 independent experiments). Data are mean ± s.d.; P values determined by repeated measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Geisser–Greenhouse correction, Bonferroni adjusted. In b, Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− are a negative control group. NS, not significant. e, ScRNA-seq profiles of cells (dots), highlighted by time point (panel title, dots in blue, versus grey for other time points) in a force-directed layout (FDL) embedding of a k-nearest-neighbours graph. f–l, Topic modelling of ILC scRNA-seq data infers functional programs. For topic 1 (f, g), topic 2 (h, i) and topic 3 (j, k), genes are ranked by a score distinguishing each topic from others (f, h, j), and cells are coloured by topic weight (top) or normalized expression (log-transformed scTransform-corrected counts) of topic-associated genes (middle and bottom) (g, i, k).

To assess the involvement of circulatory versus tissue-resident ILCs, we compared control mice with mice treated with FTY720, which have limited T-cell egress and trafficking of circulatory, induced ILC2s [20]. Both wild-type and Rag1−/− FTY720-treated mice had reduced circulating total white blood cells but exhibited no additional phenotypic differences upon IL-23 administration (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 1f, g). Inflammation and skin thickness, which resolved after initial IL-23 injections, significantly worsened upon rechallenge with secondary injections, even with FTY720 co-treatment during primary injections (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 1h, i), suggesting that the heightened secondary response was not owing to earlier ILC recruitment. Thus, similar to a type 2 inflammation model [16], ILCs resident in tissue were sufficient to drive inflammation.

Topic modelling of scRNA-seq time course

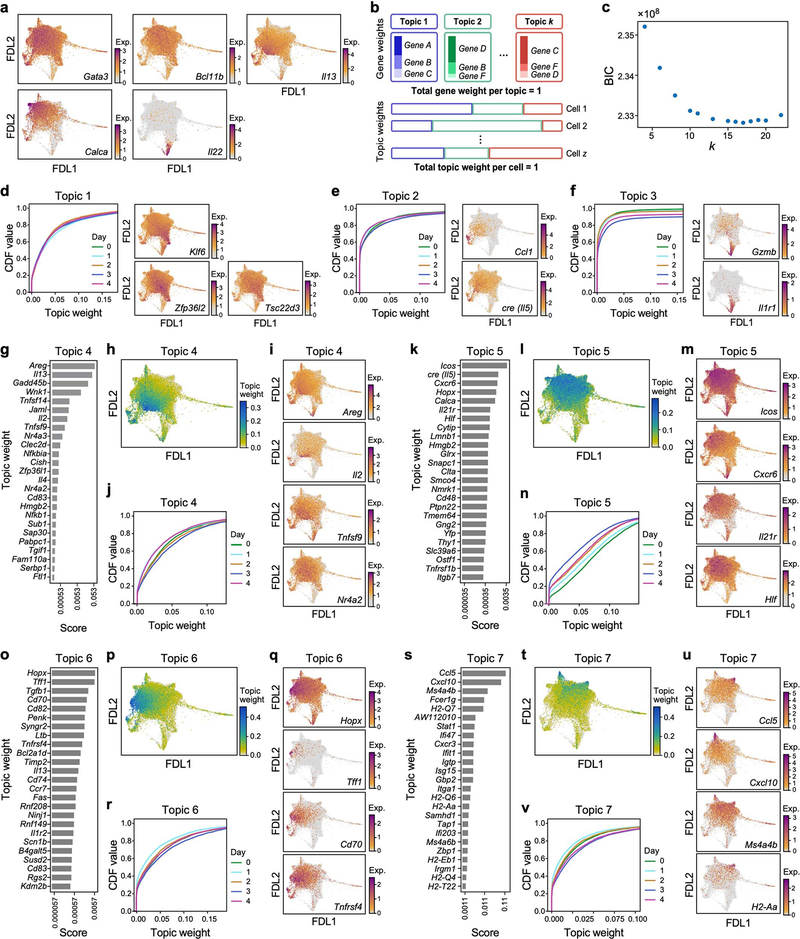

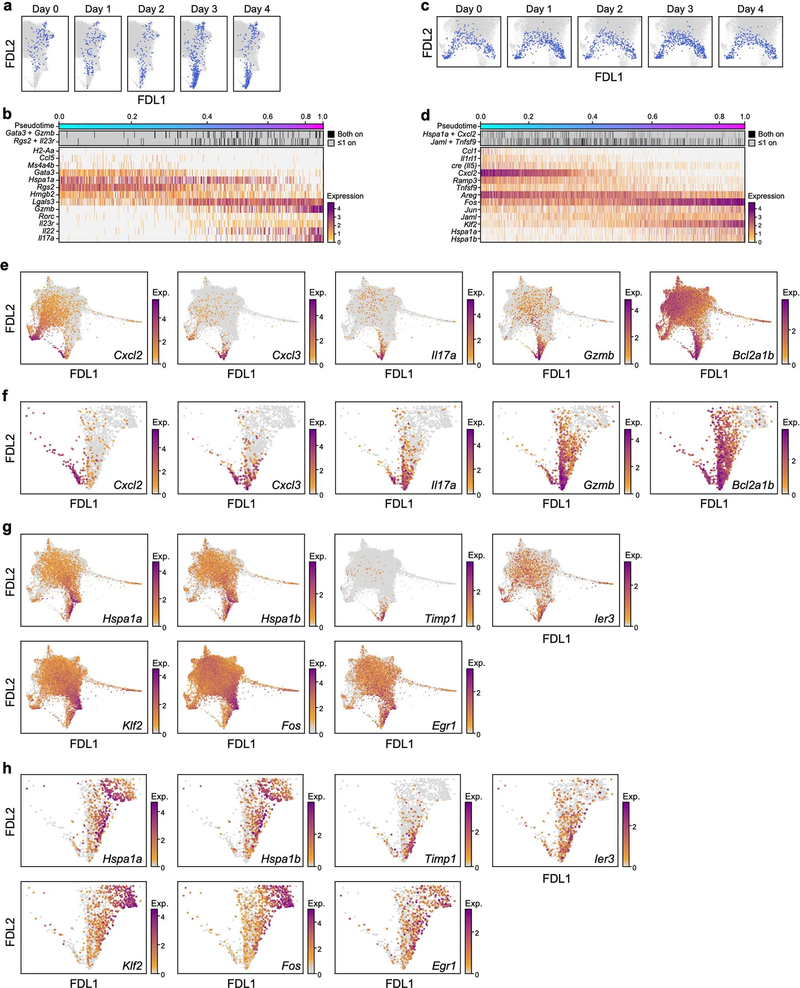

To investigate transcriptional dynamics during psoriasis initiation, we collected scRNA-seq profiles of skin ILCs from IL-5 fate-reporter mice before induction (day 0) and every day for four days of IL-23 treatment (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1j). Cells spanned a transcriptional continuum, embedded as a ‘cloud’ with ‘extensions’, including one that emerged after induction (Fig. 1e, Methods). Many key genes, aside from broadly expressed transcription factors required in ILC2s [24] (Gata3 and Bcl11b), exhibited complex patterns (Extended Data Fig. 2a). We used latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) [25], a probabilistic grade-of-membership model [26, 27], to capture continuous and composite states across time points. LDA represents each cell as a mixture of de novo inferred ‘topics’ or programs [28], modelled as distributions over genes (Extended Data Fig. 2b).

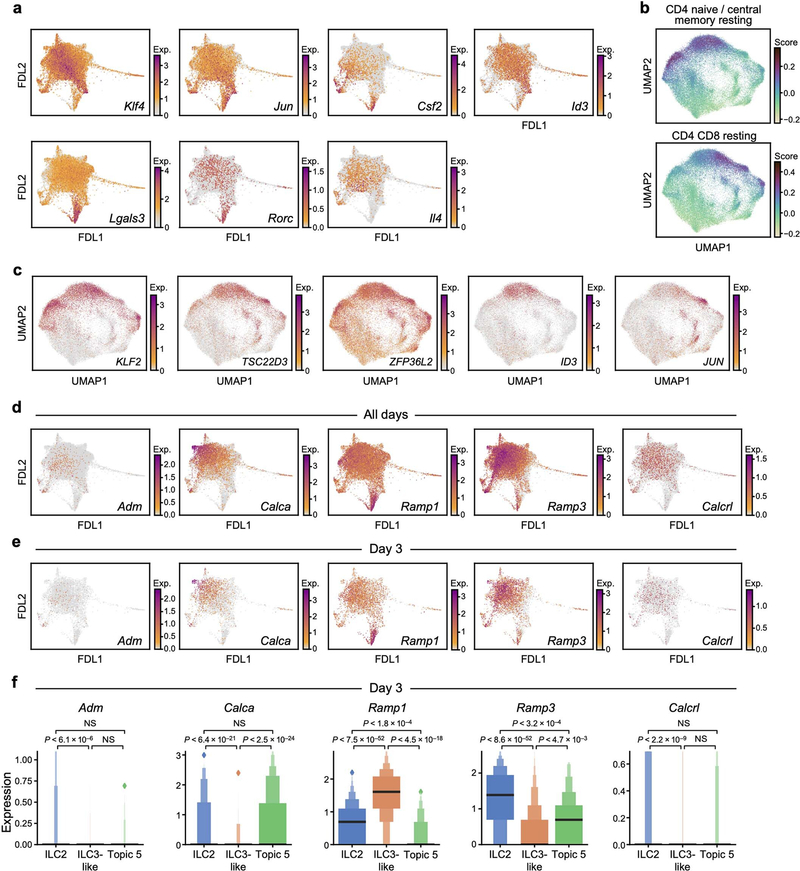

Our 17-topic model coherently captured distinct functional programs (Fig. 1f–k, Extended Data Figs. 2-4, Methods). Topic 1, ‘quiescent-like’, highlights genes characteristic of resting, naive and central-memory T cells [29], including transcription factors associated with T cell and B cell quiescence (Klf2 [30], Klf4 [30] and Zfp36l2 [31]), the TH17 repressor Tsc22d3 [32], and Id3 [33], which is associated with regulatory ILCs (Fig. 1f, g, Extended Data Figs. 2d, 5a–c). Topic 2, ‘ILC2’, features genes associated with ILC2 and TH2 cells [1] (Il5, detected using a cre reporter, and Il1rl1, which encodes the IL-33 receptor ST2) and chemokine genes (Cxcl2 and Ccl1) (Fig. 1h, i, Extended Data Fig. 2e). Topic 3, ‘ILC3-like’, is induced in a time-dependent manner and enriched in proinflammatory, ILC3- and TH17-associated genes [1] (Il22, Il17a, Il23r, Il1r1, Gzmb, Lgals3 and Csf2); cells scoring high in topic 3 also preferentially expressed Rorc, which encodes RORγ (Fig. 1j, k, Extended Data Figs. 2a, f, 5a). γδ and pan–T cell markers in topic 3 (for example, Trgc2, also known as Tcrg-C2, and Cd3d) have previously been observed in ILC3s [34, 35]. Topic 4, ‘Il2-high’, includes Il2 [36], other ILC2-associated genes (Il13, Areg and Il4), and T-cell-associated genes (Tnfsf9, which encodes 4–1BB ligand [37]) (Extended Data Figs. 2a, g–j, 5a). Topic 5, ‘Calca-high’, was downregulated over time and features the ILC2 regulator Icos and Cxcr6, as well as Calca, which encodes CGRP—a neuropeptide that suppresses ILC2 responses [38] —whose receptor component Ramp1 was upregulated in ILC3-like cells (Extended Data Figs. 2a, k–n, 4, 5d–f). Topics 6 and 7 feature other immune functions (for example, the major histocompatibility class II genes, H2-Aa and H2-Eb1) (Extended Data Fig. 2o–v). Some topics (8–10) are dominated by essential cellular functions (Extended Data Fig. 3a–f), possibly reflecting biological activation [35].

ILC3-like cells may arise via many paths

ILC3-like cells (topic 3 high) emerged and increased rapidly after IL-23 induction (Extended Data Fig. 4) from 0.6% of ILCs before induction to 2.1% by day 1 and 9.7% by day 3. This is unlikely to be solely the result of expansion, which we estimate would require a cell-cycle period of about 13 h—half that observed in rapidly expanding ILCs [35]—and would lead to higher-than-observed ‘proliferation-related’ topic 17 weights (Extended Data Fig. 3s, Methods). ILC3-like cells also express other topics, suggesting partial maintenance of pre-existing features as they activate the ILC3-like program (Extended Data Fig. 4).

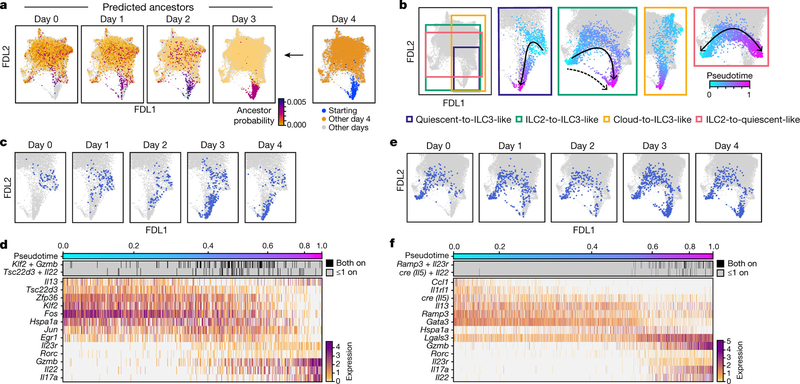

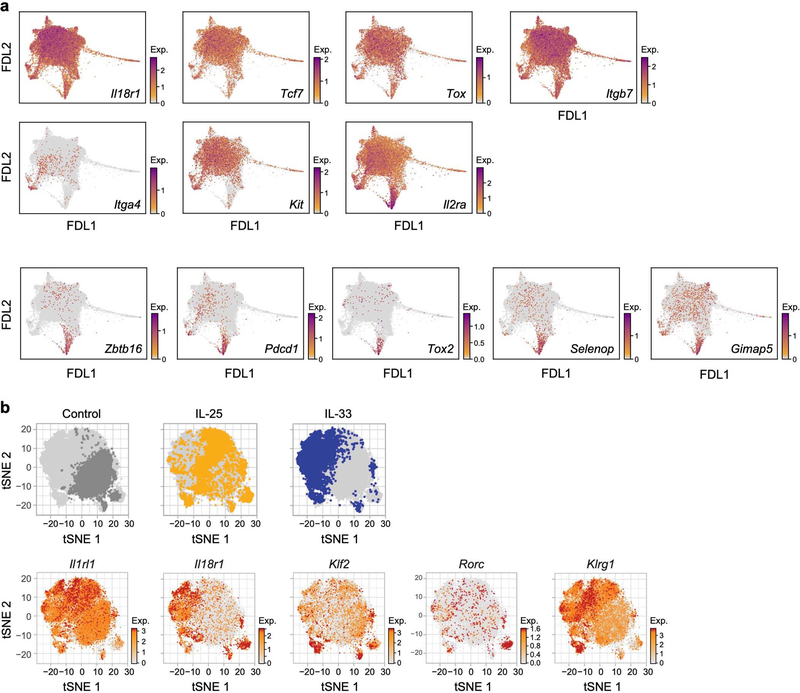

To infer which cells at each time point give rise to ILC3-like cells at day 4, we performed optimal-transport analysis using Waddington-OT [39], which predicted that ILC3-like cells arise through different trajectories, spanning a broad set of cells across the continuum (Fig. 2a). Hence, we adapted URD, our directed-diffusion method [40] to infer pseudotime-based trajectories [41] across all time points (Fig. 2b–f, Extended Data Fig. 6a–d, Methods). In agreement with Waddington-OT, these results predicted that ILC3s arise from multiple states: (1) quiescent-like cells, via intermediate states displaying combined expression of topic 1 genes with topic 3 genes (for example, Klf2 with Gzmb, and Tsc22d3 with Il22) (quiescent-to-ILC3-like trajectory, Fig. 2b–d); (2) ILC2s, via two routes, through the cloud (Fig. 2b, centre, solid arrow) or a sparse, short path (Fig. 2b, centre, dashed arrow) distinguished by high chemokine expression (Cxcl2 and Cxcl3) (ILC2-to-ILC3-like trajectory, Fig. 2b, e, f, Extended Data Fig. 6e, f); and (3) a Ccl5-high subset of topic −7-high cells (cloud-to-ILC3-like trajectory, Fig. 2b, Extended Data Figs. 2s–v, 6a, b). Trajectories through the cloud expressed heat-shock-protein genes (Hspa1a and Hspa1b; Fig. 2b–f, Extended Data Fig. 6a-d, g, h). For context, we examined tissue-specific expression of genes previously associated with ILC precursors [17, 18, 42, 43, 44], which featured in ILC3-like cells (Zbtb16, Pdcd1, Tox2 and Gimap5), in ILC2s (Kit and Itga4), or more broadly (Il18r1, Tcf7 and Tox) (Extended Data Fig. 7). The heterogeneity of ILC3-like cells may reflect their diverse origins; for example, those originating from ILC2s are the first to appear, and express different genes from those derived from quiescent-like cells (Il17a, Gzmb and Bcl2a1b versus Timp1, Hspa1a and Hspa1b) (Fig. 2c, e, Extended Data Fig. 4, 6e–h). State transitions may also occur at steady state. For example, a pre-induction ILC2-to-quiescent-like trajectory, which may be bidirectional, may create alternative paths to ILC3-like activation (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 6c, d). Overall, the analyses indicate that IL-23 triggered ILC3-like activation across a spectrum of skin ILCs.

Fig. 2: Convergent transitions to ILC3-like cells.

a, Optimal transport predicts that ILC3-like cells arise from a broad range of skin ILCs. FDL embedding (as in Fig. 1e, but excluding proliferating cells) with cells for each day (0–3) coloured by the estimated probability that they are ancestors (low, orange; high, purple; grey for other days) of day-4 ILC3-like cells. In the day −4 panel (right): day −4 ILC3-like, blue; day −4 not-ILC3-like, orange; cells from days 0–3, grey. b–f, Multiple simultaneous inferred trajectories leading to ILC3-like cells. b, FDL embedding (as in a) of cells coloured by pseudotime (early, cyan; late, fuchsia) if they are part of the inferred trajectory (other cells in grey) for (left to right): quiescent-to-ILC3-like, ILC2-to-ILC3-like, cloud-to-ILC3-like, and ILC2-to-quiescent-like trajectories. Arrows indicate trajectory directions; dashed arrow indicates secondary, sparse ILC2-to-ILC3-like trajectory. c–f, For the quiescent-to-ILC3-like trajectory: FDL embedding (as in a) with cells in the trajectory highlighted in blue for each day (panel title, all other cells in grey), (c), and heatmap of co-expression (top) and normalized expression (bottom) of trajectory-associated genes (rows) in cells (columns) ordered by pseudotime (color bar, top) (d). Analogous plots are shown for the ILC2-to-ILC3-like trajectory (e, f).. Expression of Cre reports Il5 activity.

Chromatin evidence of ILC3-like potential

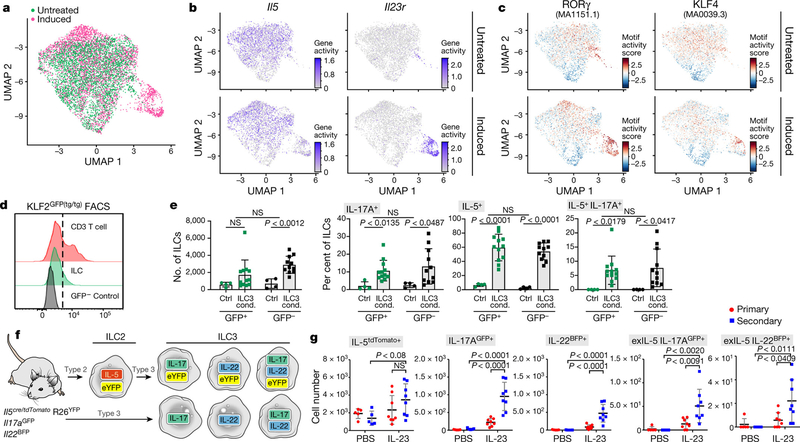

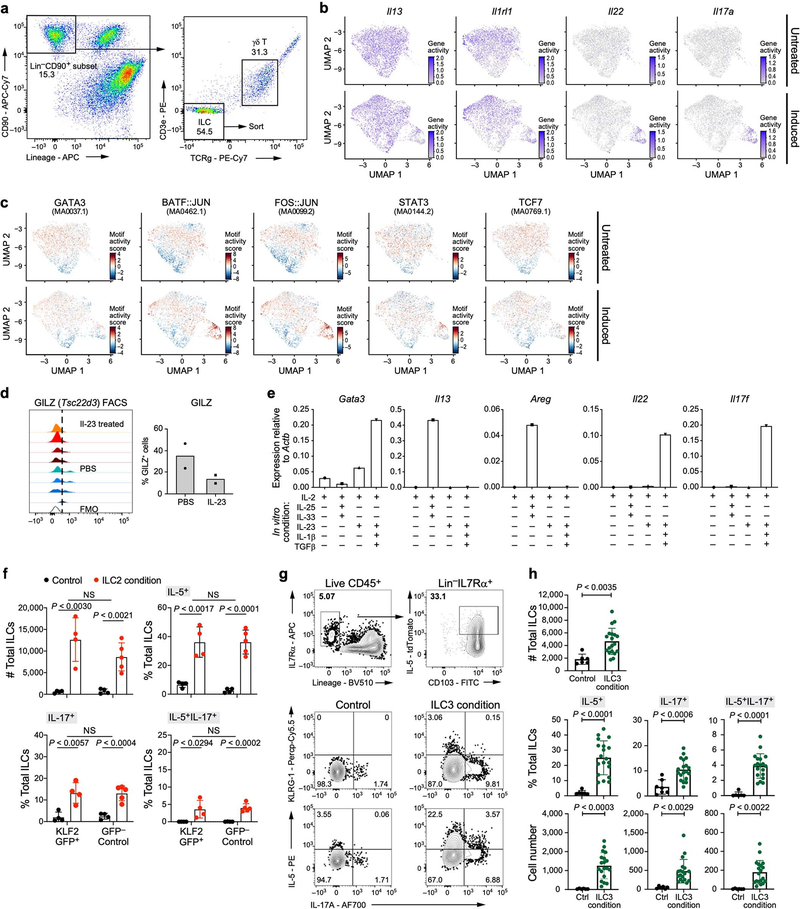

To test whether chromatin displays a capacity for transitions before stimulation, we performed scATAC-seq on ILCs from naive and IL-23-induced (day 4) mice (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 8a, Methods). Similar to results from scRNA-seq, gene ‘activity’, quantified on the basis of loci accessibility [45], indicated that ILC2-specific genes (Il5, Il13 and Il1rl1) were active in cells both before and after induction, whereas at ILC3-specific gene loci (Il23r, Il22 and Il17a), more cells exhibited activity after induction (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 8b). By contrast, binding sites for transcription factors associated with ILC3s and TH17 cells (RORγ, BATF [46, 47] and STAT3 [46]) were accessible in cells before induction (as were binding sites for the ILC2- and TH2-associated transcription factor GATA3), even in cells with inactive ILC3 genes. The accessibility of these sites increased after induction, as did accessibility at binding sites for TCF7, which is associated with ILC precursor cells (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 7a, 8c). Consistent with quiescent-like topic 1, for which we also validated GILZ production (encoded by Tsc22d3), binding sites for KLF4 were accessible, concurrent (after induction) with increased accessibility of binding sites for ILC3-associated transcription factors (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 8c, d). Thus, ILC2-biased and quiescent-like skin ILCs exhibited the potential for ILC3-like responses.

Fig. 3. Skin ILCs from naive mice have ILC2 and ILC3-like potential.

a–c, Accessible chromatin at ILC2- and ILC3-related loci, assayed by scATAC-seq. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) embedding of profiles (dots) coloured by treatment condition (day-0 untreated, green; day −4 IL-23 induced, pink) (a) or accessibility in untreated (top) or IL-23-induced (bottom) mice of ILC-associated gene loci (activity scores) (b) and transcription factor binding sites (per-cell motif activity scores; Methods) (c). JASPAR motif IDs are shown in parentheses. d, e, KLF2-producing ILCs become ILC3-like cells in vitro. d, Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) profiles of KLF2-GFP+ CD3 T cells and skin ILCs from KLF2GFP(tg/tg) mice, and GFP+ skin ILCs from wild-type control mice. Cells are pre-gated as live CD45+lin−IL7Rα+ ILCs. e, Numbers (leftmost panel) of KLF2GFP+ or KLF2GFP− skin ILCs cultured in control (ctrl) or ILC3-inducing (ILC3 cond.) conditions, and percentages (right three panels) of these cells producing IL-5, IL-17 or both IL-5 and IL-17, by intracellular staining after 2.5 h of stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (n = 4 wells (control), n = 12 wells (GFP+) and n = 11 wells (GFP−); 3 independent experiments). Error bars are mean ± s.d.; P values determined by unpaired, two-tailed t-test. f, g, In vivo validation of ILC2-to-ILC3-like trajectories. f, Possible reporter outcomes for ILC3-like cells with (top) or without (bottom) an ILC2-to-ILC3 transition, using an IL-5 fate IL-17AGFP IL-22BFP reporter mouse. g, Numbers of cells producing IL-5, IL-22 and IL-17A, including among cells previously producing IL-5 (exIL-5, YFP+), with and without IL-23 primary and secondary treatments (n = 5 mice (PBS control), n = 8 mice (IL-23); 2 independent experiments). Error bars are mean ± s.d.; P values determined by two-way ANOVA.

ILC3-like potential validated in vitro

Skin ILCs rapidly expressed genes associated with ILC2s or ILC3s when stimulated in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 8e). To further validate the ILC3-like transition potential of quiescent-like cells, we cultured KLF2+ and KLF2− skin ILCs (from KLF2–GFP reporter mice; Fig. 3d, Methods) under ILC3-inducing, ILC2-inducing or control conditions. Cells in ILC3- or ILC2-inducing (but not control) conditions produced substantial amounts of IL-5 and IL-17A (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 8f). We also confirmed the ILC3-like transition potential of IL-5-producing skin ILCs in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 8g, h). These results support the predicted trajectories leading to ILC3-like cells.

Fate mapping confirmed ILC2 to ILC3 transition

To test the model in vivo, we used IL-5 fate-reporter mice crossed with both IL-22-IRES-sgBFP and IL-17-IRES-GFP mice. At least 10% of ILC3s producing IL-22 (or IL-17A) on day 4 after IL-23 induction had previously produced, but were not currently producing, IL-5, a fraction (designated ‘exIL-5’) that further increased following rechallenge (Fig. 3f, g, Extended Data Fig. 1j, 9a). In an alternative psoriasis model, imiquimod [48] induced more IL-17A production and IL-17A-expressing exIL-5 cells, but fewer IL-22-expressing cells (Extended Data Figs. 1j, 9b). Alternative ILC2 tracing by IL-13 fate-reporter mice (Methods) showed that IL-13 fate-mapped cells had similar expression of genes associated with ILC2s (Il5 and Il13) before and after IL-23 induction, but significantly higher expression of Il17a, Il22, Il23r and Rorc after induction (Extended Data Fig. 9c). Finally, we validated IL-23-induced cells producing both IL-13 and IL-17A or both IL-13 and IL-22 using intracellular staining and Il13Smart/SmartIl17aSmart/Smart reporter mice (Extended Data Fig. 9d–h, Methods). IL-13 was produced in at least 11% of cells producing IL-22 in wild-type and Tcrd−/− mice (57% of IL-22 producing cells in Rag1−/− mice), with similar patterns for IL-17A, with or without stimulation with PMA and ionomycin . These results validated in vivo the ILC effector transitions and the adoption of mixed ILC2–ILC3 states.

Conclusion

We combined longitudinal scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, in vitro experiments and in vivo fate mapping in mouse models of psoriasis to characterize skin ILCs and their potential transitions. We inferred that they exist in continuously varying states, underlining the limitations of experimental and computational analyses that treat ILCs as discrete types. Tissue-resident ILCs, including quiescent-like cells and ILC2s, responded to IL-23 by activating a convergent, pathology-inducing ILC3-like program, characterized by co-production of IL-13 and IL-22 or of IL-13 and IL-17A. Such partially committed, flexible cell states may enhance tissue resilience, consistent with studies of haematopoiesis [49, 50], with the probabilities of cell-fate transitions shifting upon stress-inducing perturbations.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6, Tcrd−/− and Rosa26flox-STOP-flox YFP (R26YFP) Ai3(RCL-EYFP) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Rag1−/− and Rag2−/−IL2rg−/− mice were purchased from Taconic Biosciences. Il5cre/tdTomato (Red5 (R5)) were from the of R.M.L. laboratory. KLF2-GFPtg/tg mice [51] were provided by K. Hogquist. The IL-5 fate reporter in this work was generated by crossing Red5 mice with R26YFP, IL-17-IRES-eGFP (Il17aGFP) (ref. [52]) and IL-22-IRES-sgBFP (Il22BFP) mice generated in our laboratory. The IL-22-IRES-sgBFP mouse was generated by integrating an IRES-sgBFP reporter into the 3′ UTR of the Il22 gene on chromosome 10 to faithfully report IL-22 expression without disruption of IL-22 expression itself. In brief, a targeting vector was generated in the plasmid pEasyFlox in which a 2.9-kb short arm of the Il22 gene was followed by IRES (640 bp), the gene encoding BFP (735 bp), a floxed neomycin gene for selection and a long arm encoding the 3′ end of Il22. This vector was then transfected into LC-1 cells, an albino C57BL/6 embryonic stem cell line derived in our lab. After the addition of G418, clones were screened for correct orientation and insertion of the construct by PCR. One clone was selected for injection into C57BL/6 blastocysts and then injected into pseudopregnant CD-1 mice. Putative chimaeric mice were screened by their white coat colour and then identified by PCR of tail DNA. Chimeric males were bred to C57BL/6 females to obtain mice with a germ-line transmitted heterozygous BFP reporter gene. We further crossed heterozygotes to generate mice homozygous for the reporter. To maximize Cre recombination and increase the signal of R26YFP positive cells, we used homozygous Il5cre/tdTomato mice. We observed little to no difference in IL-23 induced skin thickening (Extended Data Fig. 9i). Il13Smart (Smart13; B6.129S4(C)-Il13tm2.1Lky/J; 031367) [53] mice and Il17aSmart (Smart17; B6.129S4-Il17atm1.1Lky/J; 032406) [54] mice were generated as previously described and intercrossed to generate Il13Smart/SmartIl17Smart/Smart mice for experiments. Il13YetCre (YetCre-13, C.129S4(B6)-Il13tm1(YFP/cre)Lky/J; 017353) mice were generated as previously described [55] and backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for at least 8 generations. R26RAi14RFP (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J; 00714) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and crossed to Il13YetCre/YetCre mice to generate Il13YetCre/+;R26RAi14RFP/+ mice.

All mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility at Yale University or University of California, San Francisco or University of Würzburg (ZEMM). Age- and sex-matched littermates between 10 and 14 weeks of age were used for all experiments. Unless otherwise specified, mice were randomly assigned to different experimental groups and each cage contained mice of all different experimental groups. Both male and female mice were used in experiments. Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Yale University, University of California, San Francisco, or local authorities for the University of Würzburg (ZEMM). Preliminary experiments were tested to determine sample sizes, taking available resources and ethical use into account.

Psoriasis model

The psoriasis model in this study is based on recombinant IL-23 subcutaneous injections [22] or imiquimod treatment [48]. For the IL-23 model, 500 ng IL-23 in 20 μl (provided by Abbvie or purchased from R&D Systems for scRNA-seq experiments) was injected daily into the dermis of the ear of anaesthetized mice on each of 4 consecutive days. As a control, 20 μl PBS was used with the same injection intervals. For the second challenge experiment, we waited 14 days, monitoring skin thickness before repeating the 4-day injection regimen. Skin thickness was measured daily with calipers. When indicated, FTY720 (1 mg kg−1) was dissolved in PBS and administered intraperitoneally on day −1, 1 and 3 of the experiment. Skin tissue was collected on day 5 for histology imaging, flow cytometry analysis or cell sorting. For the imiquimod model, 5% imiquimod cream was applied topically on both ears of each treated mouse for 10 days. Skin tissue was collected on day 10 for flow cytometry.

Isolation of skin lymphocytes

Ventral and dorsal dermal sheets of ears were separated, minced and incubated in RPMI medium containing 0.4 mg ml−1 Liberase TM (Roche Diagnostics) and 60 ng μl−1 DNaseI (Sigma). After digestion, the suspension was passed through and further mechanically disrupted with a syringe plunger and a 70-μm cell strainer. Lymphocytes were enriched by gradient centrifugation in 27.5% Optiprep solution (Sigma) and RPMI medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Spleens were mechanically disrupted using a syringe plunger in complete RPMI. Cells were filtered through 70-μm nylon mesh and washed.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies and ILCs were defined as CD45.2+CD90.2+, lin− (CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, B220, NK1.1, Ter119, Gr1 and FcεRIa) and TCRβ−TCRγ−CD3ε−. For experiments with Il13Smart/SmartIl17aSmart/Smart and Il13YetCre/+;R26RAi14RFP/+ mice, ILCs were defined as CD45.2+CD90.2+IL-7Ra+ and lin− (CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8α, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, NK1.1, F4/80, Gr-1, CD49b, FcεRIa and Ter119). For analyses of ex vivo IL-13 and IL-17A production, cells were stained using anti-human CD4 (clone RPA-T4, 1:20, Biolegend) and anti-human CD271 (also known as NGFR) (Clone ME20.4, 1:20, Biolegend), respectively. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were re-stimulated for 6 h at 37 °C with PMA (Sigma, 50 ng ml−1) and ionomycin (Sigma, 1 μg ml−1) with Golgistop (BD Bioscience) added after an initial 2 h of stimulation. Single-cell suspensions used for intracellular staining without PMA and ionomycin stimulation were treated for 2 h with Golgistop. Next, cells were fixed and stained with BS Cytofix/Cytoperm reagent (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Intracellular cytokines were stained with antibodies to IL-13, IL-17A and IL-22. Total ILCs were sorted as live, CD45+CD90+lin− (CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, B220, NK1.1, Ter119, Gr1, FcεRIa), CD3ε−TCRγ− cells into PBS, 0.2% FBS. ILCs from KLF2-GFPtg/tg reporter and Red5 reporter for in vitro cultures were sorted as live, CD45+IL-7Rα+lin− (CD3ε, CD5, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, B220, NK1.1, Ter119, Gr1, FcεRIa, TCRβ, TCRγ) and GFP+ or GFP− for KLF2 expression, or CD103+ for IL-5 expression in Red5 mice. Antibody list, clones, catalogue numbers and dilutions used for staining are provided in Supplementary Table 1. BD FACSDiva 7 software was used to collect raw data files from all flow cytometry experiments. All resultant data files were analysed using FlowJo version 9 or newer.

Cell culture of sorted ILC subsets

For in vitro experiments measuring gene expression, 5,000 ILCs were cultured per well of a 96-well round bottom plate in Click’s medium with 10 ng ml−1 IL-2 (R&D Systems) and 25 ng ml−1 IL-25 (R&D Systems) with 10 ng ml−1 IL-33 (R&D Systems) or 25 ng ml−1 IL-23 with 10 ng ml−1 TGFβ (R&D Systems) and 10 ng ml−1 IL-1β (R&D Systems). Cells were collected for RNA extraction, reverse transcription with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Thermofisher; 18080044) and quantitative real-time PCR (rtPCR) after 5 days of culture at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

For polarization and FACS analysis of IL-5+ or KLF2GFP-positive sorted ILCs, cells were seeded onto mitomycin-C-treated OP9-DL1 feeder cells. Approximately 50 cells per well were cultured in 96-well plates at 5% CO2 in 200 μl RPMI 1640 (GlutaMAX Supplement; ThermoFisher Scientific; 61870010) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich, F7524–500ML), 1× penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco; 10378016) and 50 nM 2-mercaptoethanol (ThermoFisher Scientific; 31350010). Cells were cultured in the presence of 25 ng ml−1 IL-2 (PeproTech; 212– 12), IL-7 (PeproTech; 217–17) and SCF (Peprotech; 250–03) and further complemented with 10 ng ml−1 IL-1β (PeproTech; 211–11B), IL-23 (eBioscience; 14–8231-63), IL-18 and 2 ng ml−1 rhTGFbeta (PeproTech; 100–21) for ILC3 polarization or 10 ng ml−1 IL-33 (Biolegend; 580506) and IL-25 (R&D; 1399-IL-025/CF) for ILC2 polarization on day 9 for another 7 days. Three days after sorting and then every other day, 100 μl of medium was replaced with fresh medium containing cytokines. FACS analysis was performed on day 16 after 2.5 h of PMA and ionomycin re-stimulation in the presence of monensin and brefeldin A.

Preparation of OP9 feeder cell layer

OP9-/DL1 feeder cells were grown in 1× MEM Alpha (Gibco; 12561–056) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (Sigma-Aldrich; F7524–500ML), 1× penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco; 10378016) and 50 nM 2-mercaptoethanol (ThermoFisher Scientific; 31350010). OP9-/DL1 cells were grown until 80–90% confluent and treated with 10 μg ml−1 mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich; M0503–2MG) for 1.5 h. Cells were washed four times with PBS and detached with trypsin–EDTA (Gibco; 10378016) at 37 °C for 2–3 min. Cells were resuspended in fresh complete T cell culture medium, and cell concentration was adjusted to seed approximately 30,000–35,000 cells in 100 μl of medium per well of a 96-well round bottom plate.

Adoptive ILC transfer

Total skin ILCs were purified by FACS and collected in PBS with 5% serum. Cells were washed twice with 1× PBS and injected (10,000 cells per mouse in 100 μl) into the retro-orbital vein of anaesthetized Rag2−/−IlL2rg−/− mice. IL-23 injection experiments were performed 14 days after transfer.

RNA extraction and rtPCR

RNA from in vitro cultures was isolated with RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and rtPCR was performed using KAPA Probe Fast qPCR Master Mix 2x Kit (Kapa Biosystems) with TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) in a StepOne cycler (Applied Biosystems). The cycle threshold (CT) values from duplicate rtPCR reactions were extracted from the StepOne cycler to Excel and were analysed with the relative quantification ΔCT method. RNA from IL-13 fate-mapped and not fate-mapped ILCs were sorted from Il13YetCre/+;R26RAi14RFP mice as CD45.2+CD90.2+RFP+lin− or CD45.2+CD90.2+RFP−lin−, respectively. Cells were sorted directly into RLT Plus Lysis Buffer using a MoFlo XDP (Beckman Coulter). RNA extraction was done using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen; 74034) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and reverse transcribed using the SuperScript Vilo Master Mix (Invitrogen; 11754). The resulting cDNA was used as template for rtPCR with Power SYBR Green reagent (Applied Biosystems; 4367689) using the primers as indicated in (Supplementary Table 2) on a StepOnePlus cycler. Samples were analysed by the ΔCT method using Rps17 for normalization using StepOne software (Applied Biosystems).

Single-cell RNA-seq

Skin ILCs were isolated from ears of IL-5 fate reporter mouse from naive mice (day 0) and at daily intervals thereafter along a four-day time course of IL-23 treated mice (1,2,3, and 4 days post-injection; n = 5 mice per group). Total skin ILCs were sorted as CD45.2+CD90.2+lin−TCRγ−CD3ε−. To reduce batch effects, while maintaining a reasonable experimental workflow, IL-23 injections were staggered, such that single-cell suspensions with subsequent sorting were collected in two rounds: one for day 0 and day 1, and another for days 2, 3 and 4. Sorted cells were washed with PBS, 0.04% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and processed for droplet-based 3′ end massively parallel scRNA-seq: sorted ILCs were encapsulated into droplets, and libraries were prepared using Chromium Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits V3 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (10x Genomics). scRNA-seq libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Nextseq 550, using a 75 cycle High Output kit.

cre dial-out PCR

To quantify cre, as a proxy for Il5 expression, a cre-specific primer was selected approximately 200 bp upstream from the polyA signal motif (AAUAAA) for the cre that was used to generate the mouse in this study. Primers were ordered from Genewiz: cre primer: 5′-GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTGGTGTGTCCATCCCTGAAAT −3′, P7-index primer: 5′-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAT [index]GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTG −3′, P5 primer: 5′-AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTC −3′.

PCR was conducted with 20 μl reaction consisting of 2 μl dilute template, 2 μl of 10 μM P5 primer, 2 μl of 1 μM of cre primer, 2 μl of 10 μM P7-index primer, 2 μl H2O and 10 μl of Q5 High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs) using the following PCR program: 98 °C for 30 s, 22 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 68 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, followed by 72 °C for 50 s and hold at 12 °C. Libraries were then pooled equally by volume, purified by MinElute (Qiagen), and eluted in 35 μl double distilled water. Purified libraries were loaded on Blue Pippin for size selection of 400–520 nucleotides. Tapestation D1000 was used for quality control after size selection. Qubit HS DNA was used to quantify the library. The library was sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq with a V3 150 cycle kit with the following setting: Read1: 28; Read2: 125; I7 Index: 8; I5 Index: 0

Dial-out PCR analysis

The dedup tool from UMI-tools v1.0.0 [56] was used to remove PCR duplicates, with the–‘per-cell’ flag and the default method. Deduplicated reads aligned to cre were then tallied for each cell.

Sanger sequencing of YFP cDNA

YFP was amplified from 10x Genomics whole transcriptome amplification with P5 primer and YFP primer (5′-GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCTCGTGACCACCTTCGG −3′), followed by Sanger Sequencing with P5 and YPF primer. The Sanger sequencing result was then compared to the vector sequence used in the generation of the mice. The obtained sequence later used for alignment can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

scRNA-seq data analysis Reference genome

To incorporate the fluorescent reporters into the reference genome for alignment, we added the sequences of Yfp, tdTomato, Gfp and Bfp to the mm10 reference genome provided by CellRanger (mm10 version 3.0.0, Ensembl 93). Yfp sequence was obtained by Sanger sequencing as described above. We checked that Yfp counts appeared relatively independent of whether Gfp and Bfp were in the reference. tdTomato was not positioned close enough to the 3′ end of the transcript to be mapped robustly, and Il5 has relatively low expression; hence, we used dial-out experiments with cre, as described above, to assess expression in the scRNA-seq libraries. Gfp was represented in the reference by the eGFP sequence and bGH terminator in the pBigT-IRES-GFP plasmid (https://www.addgene.org/browse/sequence/229542/), and the Bfp sequence was obtained from Gfp by substituting the sequence of BFP (https://www.addgene.org/browse/sequence_vdb/6363/) for eGFP. We could not confidently map reads to Gfp or Bfp, likely due, at least partly, to the large similarity in those sequences; hence, Il17a and Il22 mapped transcripts were used to quantify transcriptional expression of those genes, without any reporter transcripts. We did not use counts from tdTomato, Gfp, or Bfp fluorescent proteins in the downstream scRNA-seq analysis.

Initial data processing and quality control

Gene counts were obtained by aligning reads to the modified mm10 genome using the CellRanger software (v1.3) (10x Genomics), wrapped by scCloud (v0.9.1) [57]. Counts for cre were obtained separately by dial-out as described above. We performed quality control (QC) processing steps multiple times, initially and again after clustering and removing clusters unlikely to be ILCs. The numbers reported represent the final QC iteration, after exclusion of non-ILC cell clusters, as described below.

To remove doublets and poor-quality cells, cells were excluded from subsequent analysis if they were outliers in their sample of origin in terms of number of genes, number of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), or their joint distribution, retaining 94% (6,059), 96.6% (6,200), 91.2% (4,272), 96.7% (6,645) and 92.8% (5,051) of cells at time points 0–4, respectively. The accepted range for number of genes detected per cell was 500–3,000 for time points 0 and 1, and 700–3,300 for time points 2–4. The accepted range for number of UMIs detected per cell was 1,000–10,000 for time points 0 and 1, and 1,500–11,000 for time points 2–4. Cells were further excluded if they were outliers across remaining cells in all samples in terms of percentage of mitochondrial genes (>15%), eliminating another 3.7% of the remaining cells, resulting in 27,185 retained high-quality cell profiles.

Normalization

To normalize gene counts, we used the SCTransform function from Seurat v3, setting the ‘vars.to.regress’ parameter to the percentage of mitochondrial genes and defaults for other parameters [45]. This function is a wrapper for the variance-stabilizing function vst in the sctransform package [58], which performs regularized negative binomial regression, using cellular sequencing depth as a covariate and pooling information across genes to avoid overfitting the generalized linear model. The corrected counts returned by this function (the counts slot of the SCT assay) were used in place of raw counts in downstream processing, except for in topic modeling. Similarly, natural log of (x+1), where x is the corrected counts (data slot), was used in place of the more typical log transcripts per million for normalized expression downstream. Finally, the mean-centred Pearson residuals (scale.data slot) were used in place of more typical z-scored expression data in downstream computation of the k-nearest-neighbours graph.

Determination of variable genes

Variable gene selection was performed automatically within the call to SCTransform via selection of the top 3,000 genes, ranked by residual variance.

Initial dimensionality reduction, clustering and visualization

To cluster and remove cells unlikely to be ILCs, we computed a principal components analysis on scaled variable genes, as determined above, using Seurat’s RunPCA function, and visualized it by computing a UMAP using Seurat’s RunUMAP function on the top 30 principal components. We also computed the k-nearest neighbour graph on the top 30 principal components, using Seurat’s FindNeighbors function with default parameters (that is, k.param = 20), and in turn used Seurat’s FindClusters function (algorithm = ‘leiden’) to compute clusters based on the graph.

Removal of non-ILC clusters

On the basis of expression of marker genes across clusters, we determined that two very distinct clusters were unlikely to be ILCs. Cells from one small, distinct cluster of 109 cells had unique, high expression of genes associated with the extracellular matrix and collagen, including Sparc, Dcn, Gcn, Bgn, Col3a1 and Col1a2. Another, even smaller distinct cluster of eight cells had specific, high expression of Lyz2. Cells from these putative non-ILC clusters were removed, and the QC and normalization steps were repeated.

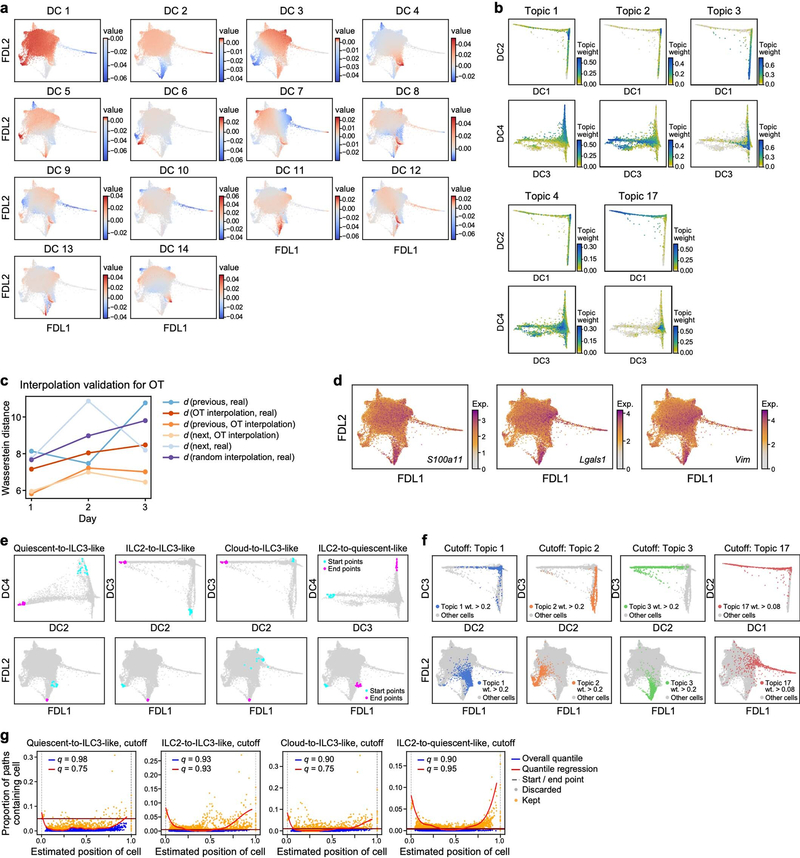

Force-directed layout embedding and diffusion maps

We computed a 30-nearest-neighbour graph with scanpy’s pp.neighbours function (v1.4.4.post1) [59] on the top 20 principal components of the Pearson residuals of the scTransformed data, for all cells and variable genes. Moreover, 14 diffusion components were calculated using scanpy’s diffmap function (visualized in Extended Data Fig. 10a, b). A force-directed layout embedding was obtained by scanpy’s draw_graph function, which is a wrapper for ForceAtlas2 (v0.3.5) [60] (https://github.com/bhargavchippada/forceatlas2) with initial random state 0 and default parameters. FDL1 and FDL2 indicate the two components of the embedding in all FDL visualizations.

Topic modelling

Topic modelling results were obtained by fitting an LDA model [25], also known as a ‘grade-of-membership’ model [26, 27, 61], to the raw counts matrix, restricted to cells that passed quality control and to non-ubiquitous genes (expressed in ≤97% of cells). The model does not use any prior information about gene programs or cell types. Fitting of the LDA model was performed with the CountClust Bioconductor package (v1.12.0) [27], which is a wrapper for the maptpx package (v1.9.2) [62]. We fit models for a varying number K of topics, ranging from K = 4 to K = 22, (with tolerance parameter tol=0.1). The number K = 17 was selected as the minimizer of the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Extended Data Fig. 2c). This choice also struck a good balance between capturing coherent signals and avoiding overfitting, although we see mild signs of both under- and overfitting the data, which did not impact the overall analysis. For example, Topic 7 spans two distinct arms in the FDL embedding (Extended Data Fig. 2t), with the association driven by relatively few genes, such as Ms4a4b (Extended Data Fig. 2u). There were also overlaps between topics in the cloud, such as between topics 9, 10 and 11 (Extended Data Fig. 3c, e, g). These features could not be jointly addressed by selection of K, and might be mitigated only by applying topic modelling ad hoc to different subsets of the data separately or by employing more complex, computationally demanding hierarchical models, such as hierarchical topic models [63].

Gene scores were calculated via CountClust’s ExtractTopFeatures function, selecting the top 200 genes per cluster, allowing sharing of genes between clusters, using the Poisson model for the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, and options = ‘min’ (selecting features that maximize the minimum KL divergence of topic compared to all others). That is, to select the genes representative of topic k, we first calculated, for all other topics l and each gene g, the KL divergence KLg(k, l) = θk,g log(θk,g /θl,g) + θl,g − θk,g between the topic-gene weights θk,g and θl,g (interpreted as Poisson intensities). Then, we ranked genes by sorting the minimum among all other clusters of these KL divergences, Dg(k) = minl≠k KLg(k, l), in descending order, and picked the top 200 genes. These minimum KL divergences are also the scores reported in Fig. 1 and Extended Data Figs. 2, 3. On the basis of high weights of cell-cycle-associated genes, such as Stmn1, Mki67 and Birc5, topic 17 was identified as a cell-proliferation program (Extended Data Fig. 3), and we denote by ‘proliferating cells’ those with a weight for topic 17 above 0.08. Downstream results are not sensitive to the exact threshold. A negative association between Il2ra and the weights for topic 1 was determined by calculating Spearman’s ρ with the scipy.stats.spearmanr function (v.1.3.2) [64], using the topic weights and the log-normalized scTransform-corrected expression values for Il2ra as inputs.

Enhanced box plots

The box plots in Extended Data Fig. 3u and 5f are obtained by calculating a geometric sequence of quantiles to base 2, that is, the 75th, 87.5th, 93.75th, 96.875th and 98.4375th percentiles of each visualized distribution, and similarly the 25th, 12.5th, 6.25th, 3.125th and 1.5625th percentiles. The quantiles are visualized by successively smaller rectangles, with the height of each rectangle representing the quantile. The median is represented by a black line. For the sake of clearer presentation, the range is cropped to the 98.5th percentile. Significance annotations are based on a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test with continuity correction in both cases. For the box plots in Extended Data Fig. 5f, the plots comprise sets of cells on day 3 whose weight for topics 2, 3, and 5 are larger than cut-offs of 0.2, 0.2 and 0.175, respectively, which were determined by inspection of the FDL visualization. We note that the determination of significance was not sensitive to this particular choice of cut-offs. The topic 2- and topic 3-high sets intersected in 8 cells that were removed from each to render all three of the above sets disjoint.

Optimal transport

Optimal transport (OT) plans between time points were calculated with the Waddington-OT package (v1.0.8) [39] on the basis of the scTransform Pearson residuals of the variable genes. Since Waddington-OT can be sensitive to the proliferation rates of cells, to simplify the analysis, and because no time point was enriched for proliferating cells, we excluded proliferating cells in this analysis. Similarly, owing to the absence of cells with strong markers for cell growth or cell death, we chose unbalancedness parameters as follows: lambda1 = 10, lambda2 = 50, and growth_iters = 1. The remaining parameters were set to: epsilon = 0.05 and local_pca = 10. The resulting transport maps were validated by interpolation between all consecutive triples of time points as in ref. [39] with Waddington-OT’s compute_validation_summary function, using default parameters (Extended Data Fig. 10c). The Wasserstein-2 distances between the actual distribution of cells at the midpoints of the triples and an OT-based interpolation at the same time point were consistently smaller than the ones between the actual distribution and a random interpolation based on the previous and next time points.

To obtain putative precursors to cells expressing the ILC3-like topic (topic 3), first, cells with a topic weight of at least 0.2 for topic 3 at day 4 were chosen as end points, and the empirical probability distribution over these cells was pulled back with the OT plans. Then, the ancestor probability was plotted separately for each previous day (Fig. 2a).

Directed pseudotime

To calculate pseudotime trajectories between two sets of cells, we broadly followed the URD methodology [40], simulating directed random walks between two sets of cells at a time. First, we selected starting and end point sets, striking a compromise between the putative predecessors predicted by Waddington-OT, the main axes of variation in the data, and biological and immunological interpretability of the resulting sets. The main axes of variation and biological interest were identified as quiescent-like cells (as captured by both topic 1 and DC4), ILC2-like cells (topic 2, DC3), ILC3-like cells (topic 3, DC2), and the cloud (itself including variation).

In detail, cell sets were selected as follows: for each main cell state of interest except the cloud (that is, expressing quiescent-like, ILC2 or ILC3-like topics), a diffusion component was identified whose extreme values are indicative of that cell state. 20 cells with an extremal diffusion component from either day 0 or day 4 were selected as start and end points according to the time-directionality of the desired path (Supplementary Table 4, Extended Data Fig. 10a, b, f). For example, for the quiescent-to-ILC3-like path (Fig. 2b), 20 day −0 cells maximizing DC4 were selected for the start point and 20 day −4 cells minimizing DC2 for the end point. For the start set in the cloud (Fig. 2b, cloud-to-ILC3-like), cells were chosen that minimize DC2, but excluding cells with a topic weight of ≥>0.2 for topics 1, 2 or 3, to pick those that most resemble induced ILC3-like cells but do not fall into any of the other considered sets of interest (Extended Data Fig. 10e). In all cases except for the cloud, a selection procedure based on topics instead of DCs led to similar results, but was slightly worse in capturing extremal cells in the FDL visualization. In the case of the cloud, the selection based on DC2 was more stable in restricting the choice to a subregion of the FDL visualization than a comparable selection by the weights for topic 3. For these two reasons, the selection was performed based on DCs instead of topics. Though the Waddington-OT results (Fig. 2a) suggest certain other sub-regions of the cloud might have as high a probability for being predecessor cells as the chosen starting sets, such as the cells at the top right corner in the FDL visualization (Fig. 2a; day 0 and 1) with high weights for topics 9 and 10 (Extended Data Fig. 3c, e), we did not specifically use cells in this sub-region as a starting point. Genes differentially expressed by cells in this region, compared to all cells (by either CountClust or a more fine-grained differential expression analysis restricted to cells in the cloud using MAST [65]), such as S100a11, Lgals1, and Vim (Extended Data Fig. 10d), are generally related to the regulation of cell cycle progression and cell migration. Moreover, this sub-region is already well-captured by the cloud starting position we selected (Extended Data Fig. 10e).

Second, an overall distance measure (initial pseudotime) from the set of end point cells was obtained by averaging (over all endpoint cells) the pseudotime output of scanpy’s dpt function with that cell set as the root. This deviates from the URD approach of a stochastic breadth-first search and was chosen because of its simpler implementation at no obvious disadvantage in terms of pseudotime estimation.

Third, a weighted transition matrix was constructed by biasing the edge weights of the 30-nearest-neighbours graph, described above, towards lower distances to the end points. This was achieved by multiplying the neighbourhood entries for each cell with a sliding logistic function, as in URD [40], down-weighting transitions to cells with larger initial pseudotime than the cell under consideration. The shape parameters of the logistic curve were calculated as in URD with optimal.cells.forward = 10 and optimal.cells.backward = 20. Finally, the matrix was re-normalized to correspond to a Markov random walk.

Fourth, a number of random walks was simulated according to the weighted transition matrix, starting at a cell chosen uniformly at random in the start set, and terminating once a cell in the end set was hit. The positions of cells in each walk were normalized to lie between 0 and 1 and then averaged over all runs that contained a specific cell to obtain a directed pseudotime estimate for that cell. The number of random walks was chosen to ensure that the relative change in the Euclidean norm between the position estimates after 1,000 simulations was less than 0.05.

Fifth, since some cells are never visited by these walks and some are visited very rarely, cells were considered to be part of a specific trajectory only if they occurred in sufficiently many walks. Specifically, cells were filtered by an overall quantile cut-off, discarding all cells with in-walk frequencies below a threshold, as well as by performing a non-parametric quantile regression of in-walk frequency occurrence against estimated path position using cubic regression splines with 20 knots (Extended Data Fig. 10g, R packages splines, v3.6.1 and quantreg, v5.51), discarding cells below a second quantile cut-off if their positions were between 0.01 and 0.99. The quantile cut-offs for each path were chosen so that enough cells around both the start and end points were selected while simultaneously avoiding selection of too large a part of the neighbourhood graph. The resulting number of cells in each path are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

Finally, pseudotime visualizations in the FDL embedding (Fig. 2b) were obtained by selecting all cells exceeding the quantile cut-offs and colouring selected cells according to their mean position estimate, with the remaining cells shown in grey. Arrows were manually added to highlight the directionality of the trajectory. Visualizations by day in the FDL embedding (Fig. 2c, e, Extended Data Fig. 7a, c) show the same cells, colouring all selected cells for each day, with remaining cells again shown in grey. The heat maps (Fig. 2d, f, Extended Data Fig. 7b, d) were generated by sorting the selected cells according to their directed pseudotime estimate and reporting normalized gene expression. Genes for each path were selected on the basis of (1) how well their expression levels were correlated with pseudotime, (2) the fact that they were differentially expressed for the start or the end point, and (3) biological interpretability.

Differentially expressed genes near trajectory endpoints

To investigate phenotypic differences between cells near the ILC3-like endpoints of the trajectories found by directed diffusion, we performed differential expression analysis on subsets constructed as follows. We defined a base set of ILC3-like cells as those cells with a topic 3 weight >0.2. Next, we compared the cells within this base set that were selected for each of the three trajectories (originating from cloud, ILC2s, and quiescent-like cells, respectively) with their complement in the base set (that is, all other cells in the base set), yielding three pair-wise comparisons. For example, cells selected for the quiescent-to-ILC3-like trajectory with a topic 3 weight >0.2 were compared to any other cells with a topic 3 weight >0.2. Differential expression analysis was performed with a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test using scanpy’s “rank_genes_groups” function. Subsequently, genes were retained if the fraction of expressing cells within the considered group was ≥0.2, the fraction of expressing cells in the other group was ≤0.95, and the fold-change between groups was at least 1.5. We considered genes with a Bonferroni-adjusted P value of less than 0.05 significant and report the results in Supplementary Table 5 for all genes and in Extended Data Fig. 7e, g for select genes, along with zoomed in versions (Extended Data Fig. 7f, h), where the plotted area is restricted to the visible subsection of the FDL plot around the cells with highest topic 3 weight, capturing more than 90% of the cells with topic 3 weight >0.2.

Computation of doubling time

To estimate the doubling time required for ILC3-like cells to emerge as a result only of expansion, we made the assumption that the total number of ILCs in the ear skin is non-decreasing between day 0 and day 1. Then, we calculated an upper bound to the required doubling time in hours as 24/log2(fraction of ILC3-like cells at day 1 divided by the fraction of ILC3-like cells at day 0), where cells were classified as ILC3-like by a topic 3 cut-off of >0.2.

Data from previous single-cell RNA-seq studies

We obtained scRNA-seq data of human T cells (Extended Data Fig. 5b, c) from lung, lymph nodes, bone marrow and blood from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), accession GSE126030 [29]. UMAP coordinates and topic modelling data were provided in the source data file associated with ref. [29]. Data from each individual sample in that study were merged and only those cells with provided UMAP coordinates were retained without further filtering. Transcript counts were normalized by cell and then transformed to natural log of (1 + 10,000 × UMI count). Significant genes for two resting topics, CD4 naive/central memory and CD4 CD8 resting, were obtained from the source data file for Fig. 4 of ref. [29]. These were subsequently used to calculate the signature scores plotted in Extended Data Fig. 5b with scanpy’s score_genes function, using default arguments. We then selected genes to visualize from our LDA results (Fig. 1f), determined their human orthologues with the Ensembl project’s Biomart database (Ensembl v.101) [66], and plotted their expression (Extended Data Fig. 5c).

For the comparison to lung-resident ILCs (Extended Data Fig. 6a), processed scRNA-seq data was obtained from a previous study [35] (accession GSE102299) without any change to processing, using the same expression values as previously reported. In particular, log-transformed normalized gene expression levels, referred to as log TPX, were calculated by calling Seurat’s LogNormalize() function with the scale set to reflect the expected number of UMIs in each condition. That is, for cells in condition c and sample i, the scale.factor argument was set to 10,000 × (wc,i/meanj(wPBS,j)), where wc,i is the mean number of UMIs per cell in condition c and sample i, and mean j denotes the mean over all PBS control samples j.

scATAC-seq

Skin ILCs were isolated from ears of wild-type naive mice (day 0) and IL-23 treated mice (day 4) with n = 10 mice per group. Total skin ILCs were sorted (approximately 60,000 cells per group) as CD45.2+CD90.2+lin−TCRγ−CD3ε−. After sorting, cells were immediately washed and resuspended in 1 ml CryoStore CS10 freezing media (StemCell Technologies) followed by cryopreservation at −80 °C with cooling rate of 1 °C min−1 using Mr Frosty (Nalgene). For scATAC-seq, cells were thawed, washed and lysed for 3 min on ice according to the low input protocol recommendations by 10x Genomics (CG000169-Rev C). For single-cell library preparation, the 10x Genomics Chromium Controller and the 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell ATAC Library & Gel Bead Kit (1000111) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (CG000168-Rev B). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Nextseq 550, using a Nextseq High Output kit and sequenced to a depth of around 130 million reads per sample (approximately 5,000–6,000 cells per sample) with paired-end reads according to the recommendations by 10x Genomics.

scATAC-seq data analysis Initial data processing and QC

Fastq files were demultiplexed from the sequencer base call files using CellRanger ATAC mkfastq (v1.1.0) from 10x Genomics. Peak-barcode matrices were obtained by aligning reads to mm10 (cellranger-atac reference v1.1.0, mm10) using CellRanger ATAC count. Demultiplexing, alignment and peak calling were performed using cellranger_workflow in Cumulus (v0.10.0) [57] in Terra (https://app.terra.bio/), a wrapper of CellRanger. Filtering for barcode multiplets was performed with the scATAC Barcode Multiplet cleanup tool (v_1.0) from 10x Genomics. Filtering was performed on each channel separately, as recommended.

Peak-barcode matrices from two channels (untreated and IL-23 induced) were then pooled using CellRanger ATAC aggr, normalizing input libraries per depth. All analyses described below were performed on the aggregated dataset.

The depth-normalized, aggregated, filtered dataset was analysed with Signac [67] (v0.1.6; https://github.com/timoast/signac), a Seurat [45] extension for the analysis of scATAC-seq data, run with random number generator seed set as 1234. Cells that appeared as outliers in QC metrics (peak_region_fragments ≤ 2,500 or peak_region_fragments ≥ 60,000 or blacklist_ratio ≥ 0.02 or nucleosome_signal ≥ 5 or pct_reads_in_peaks ≤ 35 or TSS.enrichment ≤ 2), or non-ILC cells (appearing as separate clusters, expressing fibroblast and skin cell markers like collagen or keratin genes) were excluded from further analysis. After initial processing and filtering, our dataset included 4,281 ILCs from naive mice and 4,153 ILCs from IL-23 treated mice.

Normalization and dimensionality reduction

The aggregated dataset was processed with latent semantic indexing [68], that is, datasets were normalized using term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF), then singular value decomposition (SVD), run on all binary features, was used to embed cells in low-dimensional space. UMAP was then applied for visualization, using the first 30 dimensions of the SVD space.

Gene-activity matrix and differential motif-activity analysis

A gene-activity matrix was calculated as the chromatin accessibility associated with each gene (extended to include 2 kb upstream of the transcription start site) as described in the vignette ‘Analyzing adult mouse brain scATAC-seq’ (version: 12 November 2019; https://satijalab.org/signac/articles/mouse_brain_vignette.html). Motif-activity analysis was performed with Signac’s wrapper of ChromVAR [69], as described in the vignette ‘Motif analysis with Signac’ (https://satijalab.org/signac/articles/motif_vignette.html), using a combined motif-position frequency matrix including JASPAR2018 [70] (http://jaspar.genereg.net/) motif-position frequency matrices for from both human (species = 9606) and mouse (species = 10090) transcription factors Figure 3c and Extended Data Fig. 8b display selected per-cell motif activity scores resulting from ChromVAR, with the associated Jaspar IDs. Gene-activity and motif-activity scores were visualized with Signac’s FeaturePlot, with a maximum cut-off value set at the 99th quantile (max.cutoff = q99).

Statistical analysis

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment. Statistical analysis of non-single-cell experiments was performed using GraphPad Prism 9. For all bar graphs, mean ± s.d. are shown. P values <0.05 were considered significant; FlowJo 9.0 (or more recent versions) (Treestar) was used to analyse flow cytometry data. All sample sizes and statistical tests used are detailed in the figure legends. In addition to unpaired two-tailed Welch t-test, multiple comparisons were made with repeated measures two-way ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse correction, using Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Characterization of skin immune cells upon IL-23 induction.

a, Increase in ear skin thickness is significantly greater in response to IL-23 treatment than PBS vehicle. Increase in ear thickness (mean ± s.d.) following treatment with IL-23 (red, n = 10 mice) or PBS vehicle (black, n = 10 mice). Data from 2 independent experiments; repeated measures two-way ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse correction, Bonferroni adjusted. b, c, Immune cell composition and skin phenotype in different mouse genotypes (corresponding to the experiment in Fig. 1b). b, Left three panels: number of cells producing IL-22 or IL-17 among ILCs (black dots, bars), αβ T cells (blue squares, bars) and γδ T cells (pink triangles, bars) in wild-type, Tcrd−/− (lacking γδ T cells), and Rag1−/− (lacking all T cells and B cells) mice. Right two panels: number of total ILCs or total CD45+ cells in wild-type, Tcrd−/−, Rag1−/− and Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− (lacking T cells, B cells, and ILCs) mice. n = 5 WT, n = 3 Rag2−/−Il2rg−/−, n = 2 Tcrd−/−, n = 2 Rag1−/− mice; statistics given for WT, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni adjustment. Experiments were repeated with similar results. c, Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of ear sections from wild-type, Tcrd−/−, Rag1−/− and Rag2−/−Il2−/− mice. Arrows indicate acanthosis. Representative micrographs of two independent experiments. d, Increase in skin thickness (mean ± s.d.) over time in Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice with (blue) or without (black) intravenously transferred ILCs. n = 4 mice for each group, pooled from 3 experiments; repeated measures two-way ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse correction, Bonferroni adjusted. e, IL-23-induced inflammation is dependent on Rorc. Increase in ear thickness (mean ± s.d.) following treatment with IL-23 (blue, n = 9 mice) or PBS vehicle (black, n = 8 mice) in Rorc−/− mice. Data pooled from 2 experiments; repeated measures two-way ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse correction, Bonferroni adjusted. f, FTY720 blocks white blood cell circulation. Total circulatory white blood cell (WBC) numbers (mean ± s.d.) in untreated (non-Tx) and FTY720-treated (FTY720-Tx) wild-type (n = 3 mice for each group) and Rag1−/− mice (n = 2 mice non-Tx, n = 4 mice FTY720-Tx). Unpaired two-tailed Welch t-test for wild-type mice. g, IL-23-dependent increase in ear skin thickness does not require circulating cells. Increase in skin thickness (mean ± s.d.) over time following IL-23 treatment in FTY720-treated (red) and untreated (black, non-Tx) Rag1−/− mice (Methods). n = 4 Rag1−/− non-Tx, n = 8 Rag1−/− FTY720-Tx mice; data from 2 independent experiments; difference not significant; repeated measures two-way ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse correction, Bonferroni adjusted. h, A secondary challenge with IL-23 increases susceptibility. Increase in skin thickness (mean ± s.d.) owing to primary (white) or secondary (blue) challenges by either IL-23 (n = 14 mice) or saline control (PBS) (n = 5 mice). Data from 2 independent experiments;, repeated measures two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni adjusted. i, FTY720 treatment does not impact increased susceptibility to a secondary IL-23 challenge. Increase in skin thickness (mean ± s.d.) over time in mice treated initially with either IL-23 (black) or IL-23 and FTY720 (red) and subsequently with IL-23 (Methods). Bottom bars (grey): period of primary (left) and secondary (right) challenges. n = 6 IL-23 only, n = 6 IL-23 and FTY720. j, Gating strategy on CD45+ cells for sorting total skin ILCs for scRNA-seq and IL-5 fate mapping experiments. ILCs are defined as CD90.2+ and Lin− (CD3e, CD4, CD8, TCRβ, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, B220, NK1.1, Ter119, Gr1, FcεRIa), followed by exclusion of TCRγδ+ cells.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Topic modelling of scRNA-seq time course.

a, Localized expression of ILC-associated genes. FDL embedding (as in Fig. 1e) with cell profiles (dots), coloured by normalized expression (log-transformed scTransform-corrected counts) of selected genes. b, LDA topic modelling schematic in the context of single-cell gene expression. Topics (top) consist of genes (middle), weighted (bar height, colour gradient) according to their importance in the topic. Cell transcription profiles (bottom rows) are characterized by the contribution (bar length) of each topic (colour); a cell can have multiple topics. c, In our analysis, K = 17 is optimal according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Plot of BIC for selected choices for the number K of topics. d–f, Additional plots for topics 1–3, as in Fig. 1f–k. d, For ‘quiescent-like’ topic 1, plot (left) of the empirical cumulative distribution functions (eCDF) of topic weights, grouped and coloured by time point and cropped to the overall 95th percentile of the topic weights, and FDL plots (right) of cells, coloured by normalized expression (colour bar; low, grey; high, maroon) of topic-associated genes. Analogous plots are shown for ‘ILC2’ topic 2 (e) and ‘ILC3-like’ topic 3 (f). g–v, LDA model results for topics 4–7. For ‘Il2-high’ topic 4, bar plot of top scoring genes, ranked by a score (logarithmic scale) of how well the gene distinguishes this topic from other topics (g); FDL plot (as in a) of cells, coloured by topic weight (colour bar; low, grey; high, teal) (h) or by normalized expression (colour bar; low, grey; high, maroon) of topic-associated genes (i); eCDF plots of topic weights (as in d) (j). Analogous plots shown for topics 5 (k–n), 6 (o–r) and 7 (s–v).

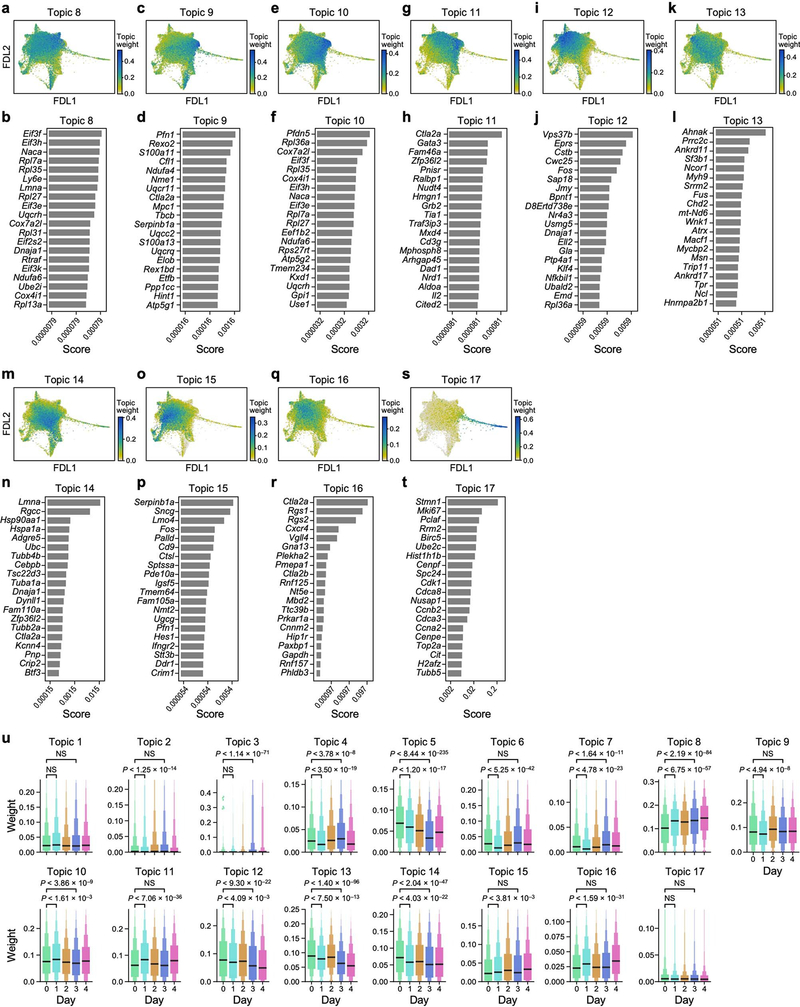

Extended Data Fig. 3. More topic modelling results, including topics 8–17 and changes in topic score distributions across time points.

a–t, LDA model results for topics 8–17 (Methods). For topic 8: FDL embedding (as in Fig. 1e) of scRNA-seq profiles (dots), coloured by topic weight (colour bar; low, grey; high, teal) (a); bar plot of top scoring genes (y axis), ranked by a score (x axis, logarithmic scale) that represents how well the gene distinguishes this topic from other topics (b). Analogous plots shown for topics 9–17 (c–t). u, Distributions of topic weights at each time point. For each topic, topic weights at each time point (colour) were plotted as enhanced box plots, indicating median (black bar) and geometric progression of quantiles (progressively decreasing box widths for 75th, 87.5th, 93.75th, 96.875th and 98.4375th percentiles, and analogously for 25th, 12.5th, 6.25th, 3.125th and 1.5625th percentiles), cropped at the 98.4375th percentile. Bonferroni-adjusted P values, determined by a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test with continuity correction, or no significance (NS, P > 1%). n = 5,290 for day 0, n = 6,051 for day 1, n = 6,525 for day 3.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Dynamic changes in topic weights highlight rapid induction of ILC3-like (topic −3-high) cells.

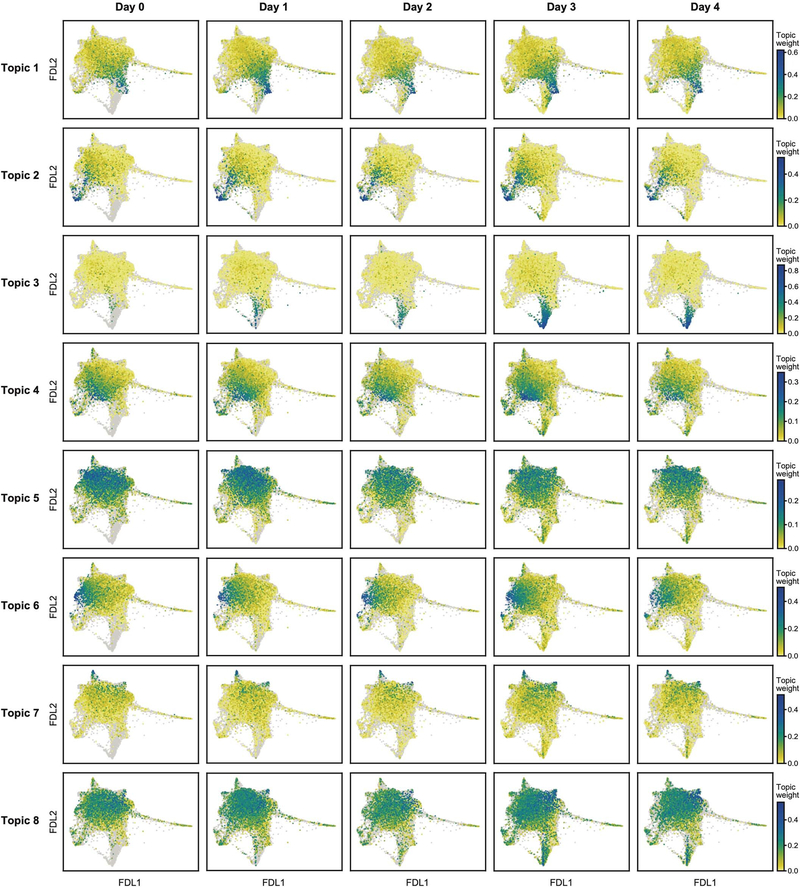

FDL embedding (as in Fig. 1e) of scRNA-seq profiles (dots), for each day (columns), with profiles coloured by topic weight (colour bar; low, yellow; high, teal; cells from other days shown in grey), for topics 1–8 (rows) (out of 17 topics; Methods). To highlight the difference between cells with low topic weight in a specific day compared to cells from other days, this colour legend differs from that used in Fig. 1g, i, k, Extended Data Figs. 2h, l, p, t, 3a, c, e, g, i, k, m, o, q, s, in the very low-weight region (here yellow instead of grey).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Expression of other topic-related genes, comparison of mouse skin ILCs to resting human T cells, and expression patterns of CGRP-signalling genes.

a, FDL embedding (as in Fig. 1e) of scRNA-seq profiles (dots) coloured by normalized expression (colour bar; low, grey; high, maroon) of selected genes (panels) associated with topic 1 (Klf4, Jun and Id3), topics 2 and 3 (Csf2), topic 3 (Lgals3 and Rorc) and topic 4 (Il4). b, c, Genes associated with quiescent-like topic 1 were also observed in resting human T cells. UMAP embedding of scRNA-seq profiles (dots) of human T cells [29], coloured by scores (colour bar; low, yellow; mid, teal; high, purple) for gene signatures associated with CD4 or CD8 resting, naive and central memory T cells (b), or by log(TP10k) (log of (1 + transcript counts scaled to 10,000 per cell)) gene expression (colour bar; low, grey; high, maroon) for topic-1-associated genes (c) (Methods). d–f, CGRP-signalling genes have distinct patterns of differential expression in cells enriched in topics 2, 3 or 5. FDL embedding (as in Fig. 1e) of cells from all time points (d) or from only day 3 (e), coloured by normalized expression (colour bar; low, grey; high, maroon) of CGRP-associated genes (panel labels). Ramp1 and Calcrl form a receptor for CGRP, encoded by Calca (which also encodes calcitonin or katacalcin, depending on splicing and processing), whereas Ramp3 and Calcrl form a receptor for adrenomedullin (Adm), and a weak-affinity receptor for CGRP. f, Normalized expression of each gene (panels) on day 3 is shown for non-overlapping subsets of cells with relatively high weights for ‘ILC2’ topic 2, ‘ILC3-like’ topic 3, or ‘Calca-high’ topic 5 (Methods). Enhanced box plots indicate geometric progression of quantiles (that is, 50th, 75th and 87.5th percentiles, as in Extended Data Fig. 3u), cropped at the 98.5th percentile. Bonferroni-adjusted P values between two distributions were determined by a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test with continuity correction. n = 632 for ILC2s, n = 224 for ILC3-like cells, n = 38 for topic −5-high cells.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Additional analysis of skin ILC trajectories and of differential gene expression in ILC3-like cells originating along different trajectories.

a–d, Additional visualizations for trajectories identified by directed diffusion (as in Fig. 2b). For the cloud-to-ILC3-like trajectory: FDL embedding (as in Fig. 2a) with cells (dots) in the trajectory highlighted in blue for each day (panel title, cells not inferred to be in the trajectory or from other days in gray) (a), and heat map of co-expression (top) and normalized expression (bottom; colour bar: low, grey; high, burgundy) of trajectory-associated genes (rows) in cells (columns), ordered by pseudotime (colour bar, top) (b). Analogous plots are shown for the potentially bidirectional ILC2-to-quiescent-like trajectory (c, d). e–h, Distinct trajectories leading to ILC3-like cells are characterized by differentially expressed genes (Methods). FDL embedding (as in Fig. 1e) including all cells (e), and cropped to focus on ILC3-like cells (f), shows cell profiles (dots), coloured by normalized expression (colour bar: low, grey; high, maroon) of genes (panels) more highly expressed by ILC3-like cells in the ILC2-to-ILC3-like trajectory (as in Fig. 2b, e–f) than by other ILC3-like cells, including Bcl2a1b, which is specifically low in quiescent-like cells, compared to other ILCs. Analogous plots are shown for genes with higher expression in the quiescent-to-ILC3-like trajectory, compared to other ILC3-like cells (g, h). P values in Supplementary Table 4.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Skin ILC similarities to and differences from mouse bone marrow and lung ILC precursors.

a, ILC-precursor markers have distinctive expression patterns in skin ILCs. While IL-18Rα+ST2− ILC2s were identified as precursors in lung [17, 18], most skin ILCs express Il18r1 but not Il1rl1, (as in Fig. 1i), and Klf2 is highest in quiescent-like cells (as in Fig. 1g). FDL embedding (as in Fig. 1e) shows cell profiles (dots) from all time points, coloured by normalized expression (log-transformed scTransform-corrected counts, Methods; colour bar; low, grey; high, maroon) of precursor-associated genes, including those that are broadly expressed in skin ILCs (top row, Il18r1, Tcf7, Tox and Itgb7), highly expressed in topic-2-high (‘ILC2’) cells (middle row, Itga4 and Kit), lowly expressed in topic-1-high (‘quiescent-like’) cells (middle row, negative marker Il2ra, which encodes CD25), or highly expressed in topic-3-high (‘ILC3-like’) cells (bottom row, Zbtb16, Pdcd1, Tox2, Selenop and Gimap5). Note that integrin proteins encoded by Itgb7 and Itga4 form the heterodimeric integrin receptor α4β7. b, Klf2 expression is associated with high Il18r1 and low Il1rl1 expression in lung ILCs [35], both in steady state and in induced ‘inflammatory ILC2s’ [7]. t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (tSNE) of lung-resident ILCs (dots), coloured by experimental condition (top row: PBS control, dark grey; orange, IL-25 stimulation; blue, IL-33 stimulation; light grey, cells from other conditions), and by logTPX (Methods) normalized expression (bottom row: colour bar: low, grey; high, red) of genes used to delineate lung precursors [17] (Il18r1 and Il1rl1), ‘quiescent-like’ topic 1-associated Klf2, ILC3-required transcription factor Rorc, and IL-25-induced ‘inflammatory-ILC2’ marker Klrg1.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Potential for skin ILCs to transition to ILC3-like states is highlighted by chromatin accessibility and in vitro stimulation.

a–c, Single-cell ATAC-seq profiles reveal accessible chromatin at ILC2-, ILC3- and quiescence-associated loci (Methods). a, Gating strategy on CD45+ cells used to sort total ILCs for scATAC-seq. ILCs are defined as CD90.2+ and lin− (CD4, CD8, TCRβ, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, B220, NK1.1, Ter119, Gr1, FcεRIa), followed by additional exclusion of CD3e+ and TCRγδ+ cells. b, UMAP embedding shows scATAC-seq profiles (dots) from untreated (top) or IL-23-induced (bottom) mice, coloured by chromatin accessibility (colour bar; low, grey; high, violet) at the promoter and gene loci of ILC2 genes (Il13 and Il1rl1) and ILC3 genes (Il22 and Il17a). c, UMAP embedding (as in b) shows profiles from untreated (top) or IL-23–induced (bottom) mice, coloured by motif activity score (colour bar: low, blue; high, red; Methods) for the ILC-associated transcription factors GATA3 (JASPAR motif code: MA0037.1, required for ILC2), BATF–JUN (MA0462.1, required for ILC3), FOS–JUN (MA0099.2, associated with ‘quiescent-like’ topic 1), STAT3 (MA0144.2, TH17-reponse regulator), and precursor-associated TCF7 (MA0769.1). d, Protein measurements validate reduced post-induction production of Tsc22d3 (associated with ‘quiescent-like’ topic 1, encoding the transcription factor GILZ). Left, distributions of protein levels, measured by flow cytometry following intracellular staining of GILZ in skin ILCs from mice treated with IL-23 (top 4 tracks, red), compared with PBS (lower 4 tracks, blue) and fluorescence minus one (FMO) control (bottom track, clear). n = 4 mice for both groups, representative data from 2 experiments. Right, proportion of Gilz+ cells (average values of two independent experiments) in control and IL-23-treated mice. e–h, In vitro validation of ILC2 and ILC3-like potential. e, Cultured skin ILCs from untreated mice express type 2- (Gata3, Il13 and Areg) and type 3- (Il22 and Il17f) associated genes (panels), when appropriately stimulated. Relative expression was measured by rtPCR on total cDNA extracted from ILCs cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-2 and ILC2-inducing cytokines (IL-25 and IL-33) or ILC3-inducing cytokines (IL-1β, IL-23 and TGFβ). Two biological replicates pooled for RNA extraction and rtPCR, n = 1 for each gene. f, Numbers (top left) of KLF2GFP+ or KLF2GFP− skin ILCs cultured in control or ILC2-inducing conditions (IL-25 and IL-33), and percentages of these cells producing IL-5, IL-17 or both IL-5 and IL-17, based on intracellular staining after 2.5 h of PMA and ionomycin stimulation (Methods). Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments (n = 4 wells control and GFP− ILC2 induced, n = 5 GFP+ induced; unpaired two-tailed t-test). g, FACS plots showing the sorting strategy for the isolation of IL-5-producing (tdTomato+) skin ILC2s from Il5cre/tdTomato (Red5) mice (top row) and analysis of the production of KLRG-1, IL-17A and IL-5 in tdTomato+ skin ILCs (remaining panels), cultured in control or ILC3-inducing conditions (IL-1β, IL-23, IL-18 and TGFβ), based on intracellular staining after 2.5 h of PMA and ionomycin stimulation (Methods). The lack of cells producing both KLRG-1 and IL-17A suggests that ‘inflammatory ILC2s’ do not underlie an ILC2-to-ILC3-like transition. h, Numbers (top) of IL-5tdTomato+ skin ILCs cultured in control or ILC3-inducing conditions (as in g), and percentages (middle row) and numbers (bottom row) of these cells producing IL-5, IL-17 or both, based on intracellular staining after 2.5 h of PMA and ionomycin stimulation (Methods). Data are pooled from three independent experiments; n = 6 control, n = 19 treated wells; error bars are mean ± s.d.; unpaired, two-tailed t-test. ILCs from KLF2-GFPtg/tg reporter and Red5 reporter for in vitro cultures were sorted as live CD45+IL-7Rα+lin− (CD3ε, CD5, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, B220, NK1.1, Ter119, Gr1, FcεRIa, TCRβ, TCRγ) GFP+ or GFP− for KLF2 expression, or CD103+ for IL-5 expression in Red5 mice.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Reporter mouse systems confirm ILC2-to-ILC3-like transition of committed IL-5+ ILC2s, and mixed ILC2–ILC3 state.