Abstract

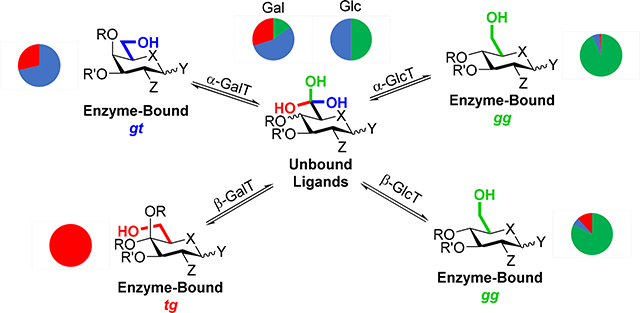

Carbohydrate side chain conformation is an important factor in the control of reactivity at the anomeric center, ie, in the making and breaking of glycosidic bonds, whether chemically or, for hydrolysis, by glycoside hydrolases. In nature glycosidic bond formation is catalyzed out by glycosyltransferases (GTs), glycoside phosphoryases, and transglycosidases. By analysis of 118 crystal structures of sugar nucleotide dependent (Leloir) GTs, 136 crystal structures of glycoside phosphorylases, and 54 crystal structures of transglycosidases bound to hexopyranosides or their analogs at the donor site (−1 site), we determined that most enzymes that catalyze glycoside synthesis, be they GTs, glycoside phosphorylases or transglycosidases, restrict their substrate side chains to the most reactive gauche,gauche (gg) conformation to achieve maximum stabilization of the oxocarbenium ion-like transition state for glycosyl transfer. The galactose series deviates from this trend, with α-galactosyltransferases preferentially restricting their substrates to the second-most reactive gauche,trans (gt) conformation, and β-galactosyltransferases favoring the least reactive trans,gauche (tg) conformation. This insight will help progress the design and development of improved, conformationally-restricted GT inhibitors that take advantage of these inherent side chain preferences.

Keywords: glycosyltransferase, glycoside hydrolase, glycoside phosphorylase, transglycosidase, inhibitor, oxocarbenium ion, conformational analysis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Glycosyltransferases (GTs) and transglycosidases are enzymes that catalyze the formation of glycosidic bonds,1–4 a pivotal transformation in carbohydrate chemistry and the glycosciences in general.5–8

To bring about glycosidic bond formation GTs stabilize oxocarbenium ion-like transition states (TSs) for displacement of phosphate-based leaving groups from the anomeric position of their substrates (glycosyl donors) by alcohols (glycosyl acceptors) with either inversion or retention of configuration. In this they closely resemble the glycoside hydrolases (GHs), which cleave glycosidic bonds through oxocarbenium ion-like TSs by displacement of an alcohol by water,9, 10 albeit the intimate details the details of GT mechanisms are the subject of ongoing debate.1, 11 As the GTs are prime drug targets given their key involvement in multiple disease states including cancer, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and in bacterial processes such as cell wall biosynthesis,12–15 a more complete understanding of the fine details of their mechanisms is necessary to facilitate improved inhibitor design.

Glycoside phosphorylases are enzymes that catalyze the reversible displacement of a glycosidic linkage with a phosphate group. Based on their amino acid sequences, these enzymes are categorized into either GT families (such as glycogen and starch phosphorylases) or GH families (sucrose and maltose phosphorylases, among others).16, 17 Transglycosidases are a group of enzymes that, while formally classified as GHs due to their amino acid sequences, catalyze glycoside formation rather than hydrolysis with retention of configuration.18

The mechanistic parallels between GTs, glycoside phosphorylases, transglycosidases, and GHs extend to chemical glycosylation, for which by far the most common approach involves displacement of a leaving group from the anomeric center of a glycosyl donor by an acceptor alcohol through oxocarbenium ion-like transition states.9, 19–26 In chemical glycosylation and hydrolysis, the conformation of the donor side chain is one of the many factors that influence the reactivity of glycosyl donors, it having been established that donors with the gauche,gauche (gg) conformation are more reactive than those with the gauche,trans (gt) conformation, which in turn are more reactive than their counterparts with the trans,gauche (tg) conformation (Figure 1).27,28

Figure 1.

The staggered conformations of pyranoside side chains and their approximate population in free solution in the gluco- and galactopyranosides and in the N-acetylneuraminic acids

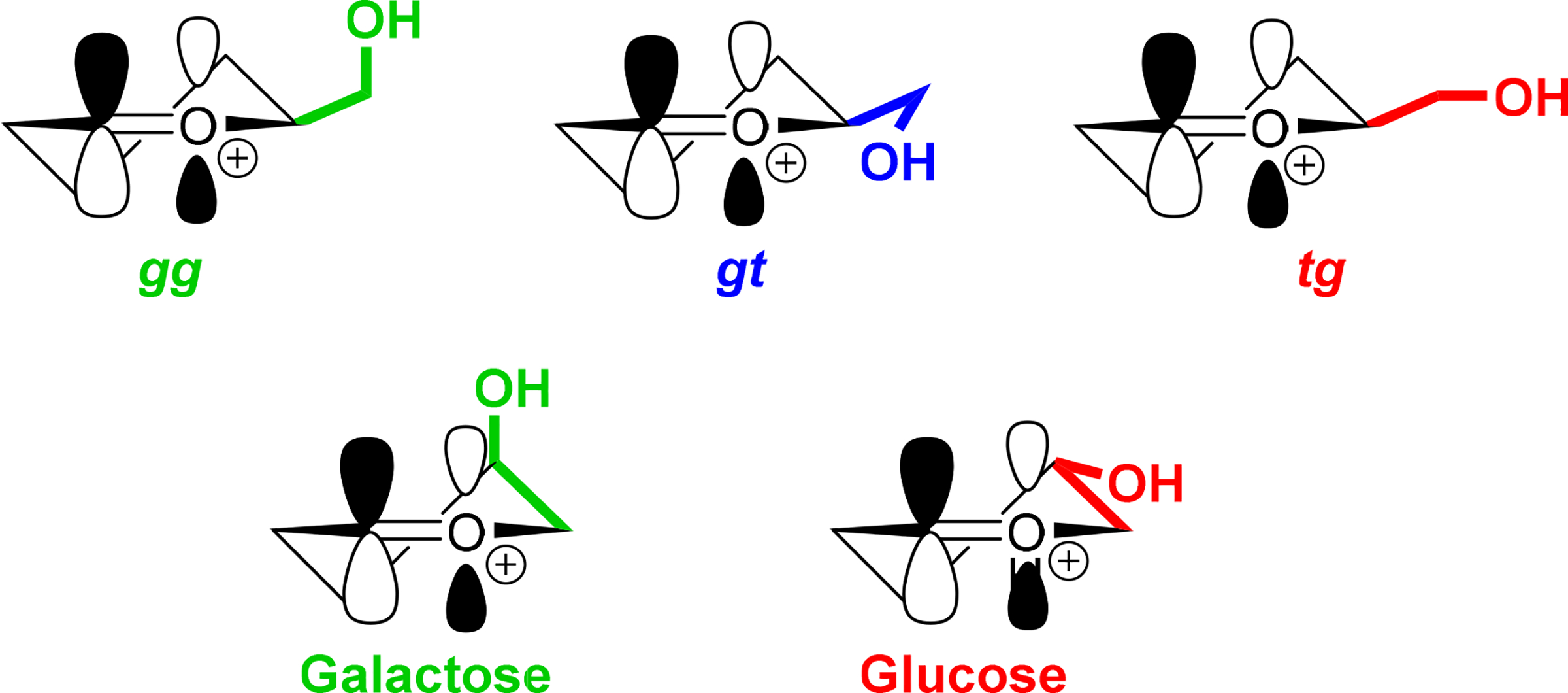

The influence of glycosyl donor side chain conformation on reactivity is considered to arise from the interplay of the C-O bond in the side chain with the partial positive charge at the anomeric center in the glycosylation transition state. The tg conformation is understood to be electron withdrawing and so to destabilize transition state energies, while the gg conformation provides electrostatic stabilization to the partial positive charge at the anomeric center; the gt conformation is intermediate between the tg and gg conformers in its impact.29–33 The influences of the gg and tg conformers on positive charge at the transition state are more easily understood by comparison with the directly analogous axial and equatorial C-O bonds at the 4-position of galactopyranosyl and glucoopyranosyl donors, respectively, with the latter being the less reactive of the two (Figure 2).34, 35 Electrostatic stabilization of the positively charged transition state by an ideally located substrate side chain has also been demonstrated for purine nucleoside phosphorylase by Schramm and coworkers.36

Figure 2.

Spatial relationships of side chain and C-4 hydroxyl groups with the oxocarbenium π* orbital

By examination of the extensive crystallographic database available in the PDB of GTs bound to hexopyranosides at the donor site we show here that glucosyltransferases typically restrict donor side chains to the reactivity enhancing gg conformation, while galactosyltransferases favor the gt and even tg conformations. We also examine the glycoside phosphorylases and transglycosidases, and find that they too make use of the restriction of side chain conformation to facilitate reactions passing through oxocarbenium ion-like transition states. Side chain restriction by GTs, glycoside phosphorylases, and transglycosidases closely resembles that employed by the GHs,37 and appears to be a broad general phenomenon that can in principle be applied to the design of improved and more selective inhibitors.

Results and Discussion

Because of the available crystallographic data, we focused on the Leloir GTs, which catalyze displacement of nucleotidyl mono- or diphosphates from the anomeric position of the donor, and on glycoside phosphorylases, as opposed to the non-Leloir GTs employing polyprenyl phosphates and pyrophosphates, for which insufficient crystallographic data is available. Leloir GTs are broadly grouped into two classes, inverting and retaining, according to the stereochemical outcome of the substitution process they catalyze. In the inverting GTs the nucleophilic acceptor alcohol directly displaces the departing phosphate from the anomeric center in an SN2-like manner (Figure 3), functioning analogously to the inverting GHs. The retaining GTs are considered to achieve substitution by an SNi mechanism (Figure 3), as for the most part they lack a suitably placed internal nucleophile for the type of double inversion with the intermediacy of a covalent glycosyl enzyme adduct that is operative in the retaining GHs. Computational and mass spectrometric studies nevertheless support the formation of a glycosyl-enzyme adduct in a limited number of cases.38, 39 The transglycosidases, on the other hand, employ a comparable mechanism to that of retaining GHs, forming an enzyme-bound covalent intermediate in a classic Koshland double displacement.18 Despite these differences, glycosidic bond formations by each of the inverting and retaining GTs, the glycoside phosphorylases, and the transglycosidases pass through transition states with significant oxocarbenium ion character and so positive charge at the anomeric center.

Figure 3.

Approximate transition states for inverting and retaining GTs illustrated for D-glucose with the gg side chain conformation.

Applying the same strategy as for the GHs, we used the Carbohydrate Active Enzymes database (CAZy, http://www.cazy.org)40 to search the PDB for crystal structures of glycosyltransferases, glycoside phosphorylases, and transglycosidases containing hexopyranosides or corresponding analogs bound at the donor subsite of the enzyme, manually inspecting each individual structure to avoid errors such as incorrect binding site identification. The Privateer software41 was used to validate each of the glycoside-based structures, with a minimum allowable Real Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC) of 0.8.42 To minimize crystallographic errors in the data set,43 we limited the resolution of included crystal structures to ≤ 2.50 Å. This cutoff is more relaxed than the ≤ 2.00 Å one previously applied for the GHs, but is necessary in order to obtain a sufficiently large data set: comparison between data limited by a 2.00 Å cutoff and that applying the 2.50 Å cutoff reveals no significant difference and justifies the use of the more relaxed limit. Accordingly, all subsequent discussions refer to the larger data set. By these criteria, a total of 118 crystal structures of Leloir GTs with carbohydrate-based ligands bound in the donor site were located and are summarized in Table 1, with the raw data compiled in Table S1. For each category of enzyme, Table 1 shows the distribution of bound staggered and eclipsed side chain conformations, along with the number of crystal structures showing hydrogen bonding between the side chain hydroxyl group and the enzyme. Structures with multiple chains in the unit cell were listed as one entry if the side chain conformation of the ligand in each active site was the same; when this was not the case, the entries were classed as ambiguous and not considered further. As, unlike the GHs,44 actual transition state analogs of GTs have proven to be elusive,15, 45, 46 the vast majority of ligands are simple glycosides.

Table 1.

Side chain conformations of ligands bound to Leloir glycosyltransferasesa

| Enzyme Function | gg | gt | tg | Eclipsed | Total | H-bonding to O6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Galactosyltransferase | - | 6 (5) | 2 (2) | - | 8 (7) | 8 (7) |

| β-Galactosyltransferase | - | - | 8 (3) | - | 8 (3) | 8 (3) |

| α-N-Acetyl Galactosaminyltransferase | 1 (−) | 2 (2) | 5 (2) | - | 8 (4) | 8 (4) |

| α-Glucosyltransferase | 30 (15) | 3 (3) | 1 (−) | 3 (1) | 39 (19)b | 37 (18) |

| β-Glucosyltransferase | 10 (6) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | - | 12 (8) | 12 (8) |

| α-N-Acetyl Glucosaminyltransferase | 4 (2) | 1 (−) | 1 (−) | 1 (−) | 7 (2) | 6 (2) |

| β-N-Acetyl Glucosaminyltransferase | 10 (6) | 4 (3) | - | 2 (−) | 16 (9) | 14 (7) |

| α-N-Acetyl Hexosaminyltransferasec | 1 (−) | 1 (−) | - | - | 2 (−) | 2 (−) |

| α-Mannosyltransferase | - | - | 1 (−) | - | 1 (−) | 1 (−) |

| β-Mannosyltransferase | 2 (2) | - | - | - | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| α-Valeniolyltransferase | 1 (−) | 1 (1) | - | - | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Heptosyltransferase | 2 (−) | - | - | - | 2 (−) | 2 (−) |

| α-Sialyltransferase | 9 (7) | - | 1 (−) | 1 (−) | 11 (7) | 7 (6) |

| Total | 70 (38) | 19 (15) | 20 (8) | 2 (−) | 118 (62) | 109 (58) |

Data are listed at the 2.50 Å cutoff, with those for the 2.00 Å cutoff given in parentheses

Two structures bear ambiguous side chain conformations

These enzymes act on both glucosides and galactosides

α- and β-Glucosyltransferases and β-N-acetyl glucosaminyltransferases show moderate to strong preference for binding their ligands at the donor site in the gg conformation (77%, 83%, and 63% gg, respectively; Scheme 1). Here, it is informative to consider the different CAZy families encompassed by the α-glucosyltransferases and β-N-acetyl glucosaminyltransferases (Table S4). Thus, in the latter case, while the overall side chain population distribution is a ~2:1 mix of gg and gt conformers, the crystal structures featuring the gg conformation all belong to GT families 2 and 41, while those favoring the gt conformation are predominantly members of GT family 13, indicating a family-specific influence on side chain binding. Interestingly, all three GT13 structures hold the catalytic aspartic acid directly above the ring instead of in the typical syn or anti positions, sterically disfavoring the gg conformation;47, 48 a similar observation was made for the GH116 glucoside hydrolases, whose members also favor the gt conformation.37 These trends are nicely illustrated by the natural substrate UDP-α-N-acetylglucosamine 2, as shown in Scheme 2. Turning to the α-glucosyltransferases, GT families 20, 44, and 88 show high selectivity for the gg conformation, while families 4 and 24 bind their substrates in the gt conformation, though the limited sample size restricts the conclusions that can be drawn. Notwithstanding the small sample size for the mannosyltransferases, the population trends closely resemble those found in the corresponding GHs and stand in stark contrast with the roughly 1:1 gg to gt ratio observed both in solution and in the carbohydrate binding domains of lectins. Collectively, the data suggest that glucosyl- and likely β-mannosyltransferases exploit the same phenomenon as the corresponding GHs to gain additional transition state stabilization.

Scheme 1.

Bound and unbound side chain populations of UDP-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-α-glucose (1) as exemplified by E. coli trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (PDB ID 1UQT)

Scheme 2.

Bound and unbound side chain conformations of UDP-α-N-acetyl glucosamine (2), exemplified in the S. aureus TarP and rabbit N-acetyl glucosaminyltransferase 1 (PDB structures (a) 6H21 and (b) 1FOA)

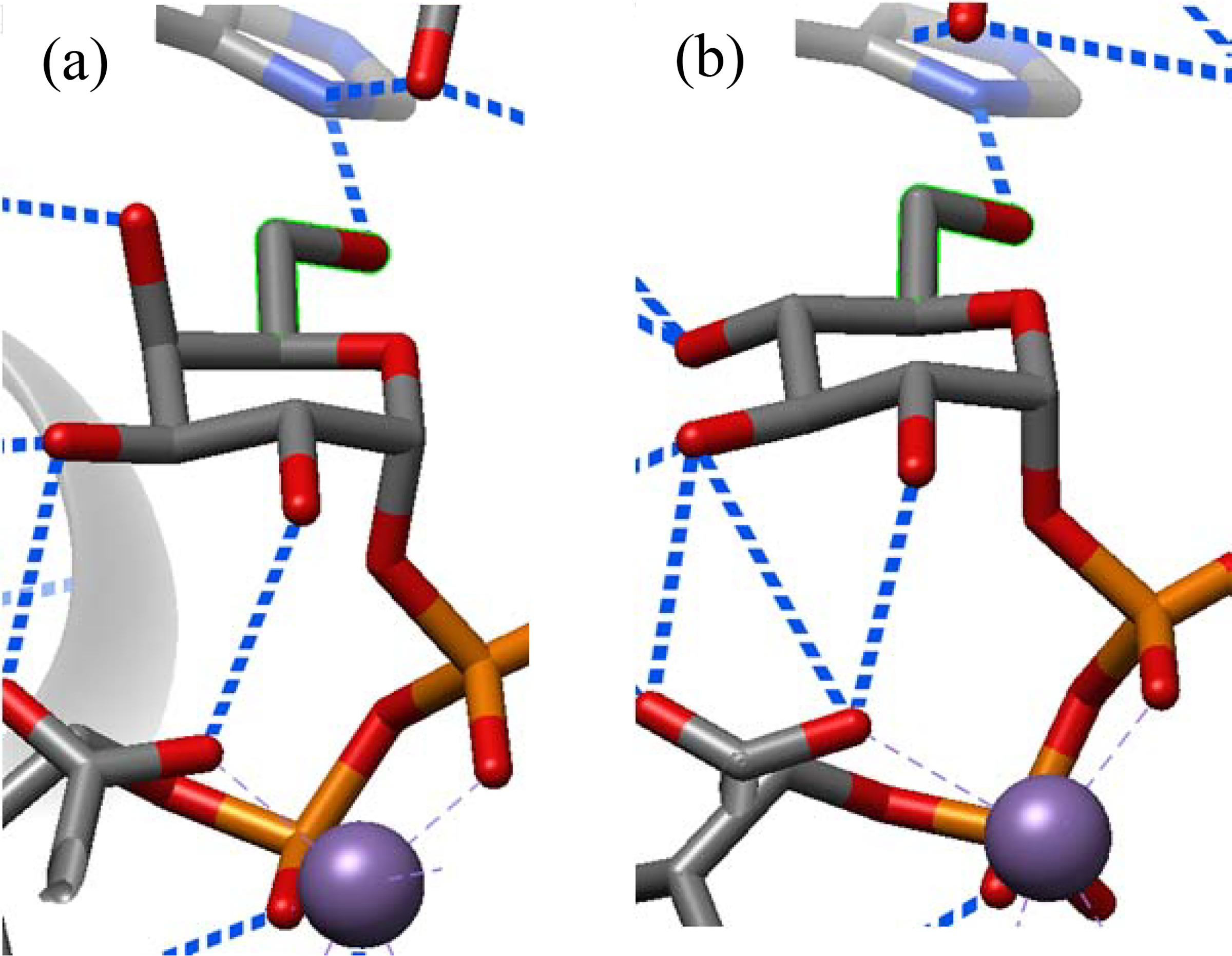

As with the GHs, the α-galactosyltransferases follow a different pattern (Table 1), which must stem in part from the higher energy of the gg conformation in free galactose as is evident from its relatively minimal population in solution. Thus, 75% of α-galactosyltransferases bind their ligand side chains in the gt conformation, which parallels the high gt preference of α-galactosidases. The α-N-acetyl galactosaminyltransferases show a small preference for binding their ligands in the tg conformations. A study of the bound conformations of UDP-α-galactopyranose, UDP-α-glucopyranose and UDP-α-C-galactopyranose in the vicinity of the donor sites of the homologous glycosyltransferases α-(1→3)-N-acetyl galactosaminyltransferase (GTA) and α-(1→3)-galactosyltransferase (GTB), and their chimera, is revealing.49 Lowary and coworkers show that, for each of these enzymes, the donor binds in a stepwise manner, anchoring first by the UDP group and then by rotating the pyranoside ring to place it directly above the pyrophosphate moiety in the conformation required for catalytic activity and denoted as the tucked under conformation. As is clear from Figure S1 and from Table S5, which show the side chain conformations of ligands bound in all non-tucked under conformations, only when UDP-α-galactopyranose is correctly placed in the donor site in the tucked under conformation does the enzyme restrict side chain conformation by H-bonding (Figure 4a). Four structures containing UDP-α-C-galactopyranose are not correctly located in the donor site for transfer, do not have the tucked under conformation of the pyrophosphate, and do not exhibit protein-side chain H-bonding. Four structures with bound UDP-α-glucopyranose hold the side chain in the gg conformation by H-bonding, but in an alternate orientation within the binding pocket; a further structure has UDP-α-glucopyranose correctly located in the binding pocket for transfer, with the tucked under conformation of the pyrophosphate, and the side chain held in the gt conformation consistent with the pattern for a galactose-processing enzyme (Figure 4b). Clearly, GTB has evolved to capture the side chain in a suitable conformation for transition state stabilization once the natural substrate is correctly poised for glycosyl transfer in the catalytically active tucked under conformation.

Figure 4.

Partial structures of (a) UDP-α-galactopyranose (PDB ID 5C1G) and (b) UDP-α-glucopyranose (PDB ID 5C8R) in the donor site of GTB with the tucked under conformation of the pyrophosphate and the side chain restricted to the gt conformation by H-bonding.

In accordance with the binding preferences exhibited by the β-galactosidases, all eight crystal structures of β-galactosyltransferases hold the side chain in the tg conformation (Table 1), standing in stark contrast with the high selectivity for the gt conformation observed for galactosyl substrates bound to alternate sites and to the corresponding lectins (vide infra). The switch in the side chain conformation from gt to tg on going from the retaining α-galactosyltransferases to the inverting β-galactosyltransferases is illustrated in Scheme 3 for the common natural substrate UDP-α-galactose (3).

Scheme 3.

Contrasting binding preferences of α- and β-galactosyltransferases exemplified by (a) cow α-galactosyltransferase and (b) mouse β-galactosyltransferase (PDB structures (a) 2VS5 and (b) 1YRO).

Finally, the sialyltransferases show high preference for binding of the substrate side chain in the gg conformation, which is the predominant conformation in free solution. This raises the possibility that these enzymes have simply evolved to bind the most stable conformation, which coincidentally provides optimal stabilization to the TS. Lectins for other higher-carbon sugars are also known to bind their ligands with the side chain in the conformation that is strongly preferred in solution.33, 50 It is possible that, when suitable structures eventually become available, GTs for the synthesis of sialic and/or ulosonic acid-containing bacterial capsular polysaccharides, particularly those carrying pseudaminic acids or Kdo residues,51–53 may bind their ligands in different conformations to the strongly disarming tg conformation preferred in solution (Figure 5).54, 55 In this respect, it is of interest that docking of CMP β-Kdo into the crystallographically characterized active site of the β-Kdo GT from the multidomain WbbB protein involved in the biosynthesis of the Raoultella terrigena lipopolysaccharide O-antigen favors a 2,6B conformation of the pyranose ring with the side chain held in the gt conformation by H-bonding to the protein.56

Figure 5.

Solution side chain conformations of CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid (4) and CMP-Kdo (5)

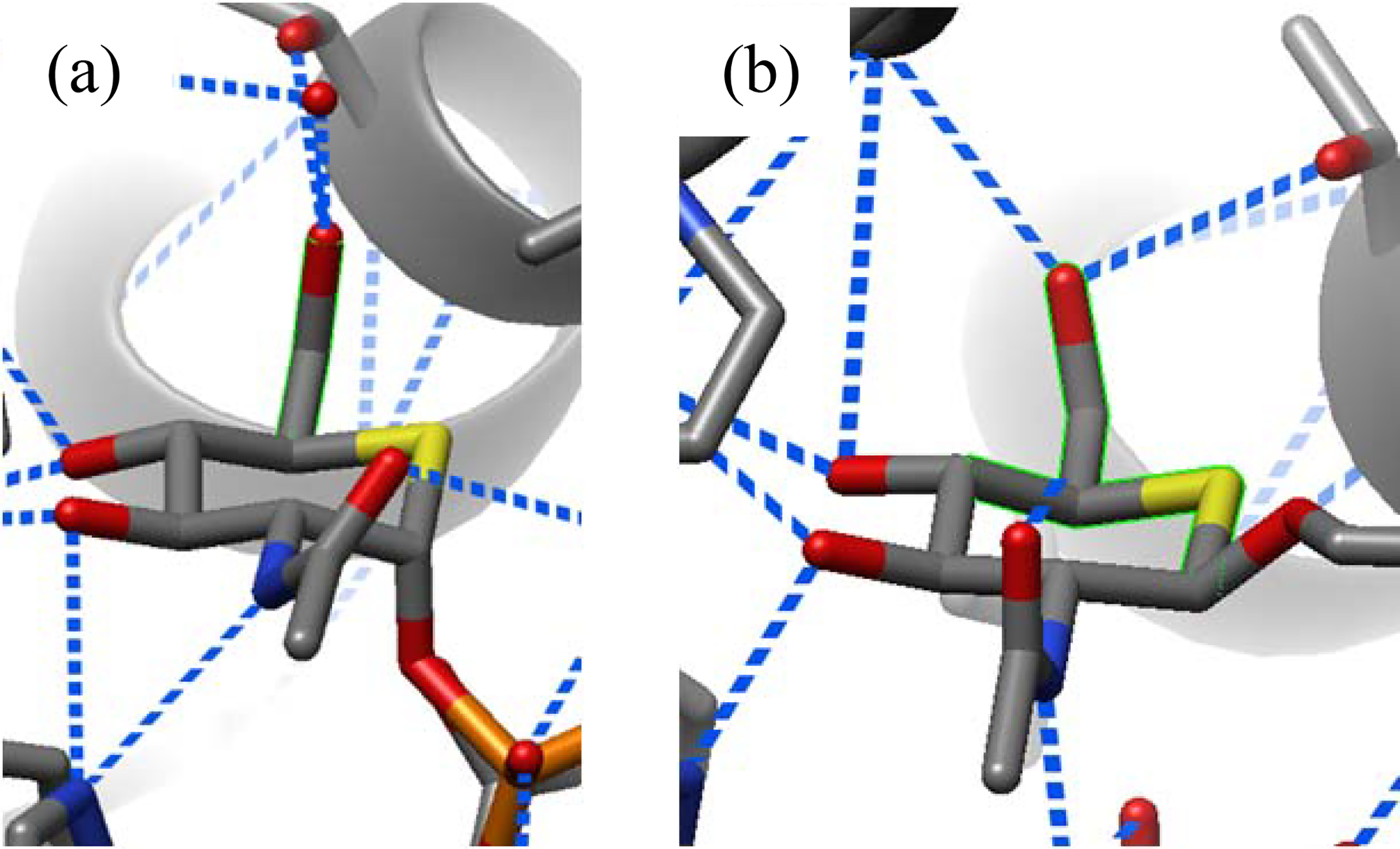

Overall, the data suggest that restriction of side chain conformation by the GTs takes place on binding of the substrate in a conformation primed for transfer and presumably continues through the transition state to product release. This pattern of initial side chain conformational restriction at the level of the enzyme-substrate complex, with maintenance through the transition state, is directly analogous to that seen in the GHs.37 Because of the relative absence of true transition state inhibitors for the GTs, snapshots of the processing of substrates by GTs, while employing crystallography to reveal the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-product complexes, use computations to visualize the transition state complex.57, 58 Such computations typically do not focus on the conformation of the substrate side chain nor reveal the extent to which it is restricted by hydrogen bonding to the GT.38, 57–60 Nevertheless, crystallographic studies on cognate enzyme-substrate and enzyme-product complexes are informative, particularly as both reveal a common conformation of the side chain. For example, such a study of the human O-GlcNAc transferase, an inverting GT, by the Vocadlo and Walker groups,61 reveals that both substrate (Figure 6a) and product (Figure 6b) analogs based on the 5-thia-GlcNAc skeleton are bound with the side chain in the gg conformation.

Figure 6.

Partial structures of (a) UDP-5S-GlcNAc donor (PDB ID 4GYY) and (b) a thioglycopeptide product (PDB ID 4GZ3) complexed to human O-GlcNAc transferase

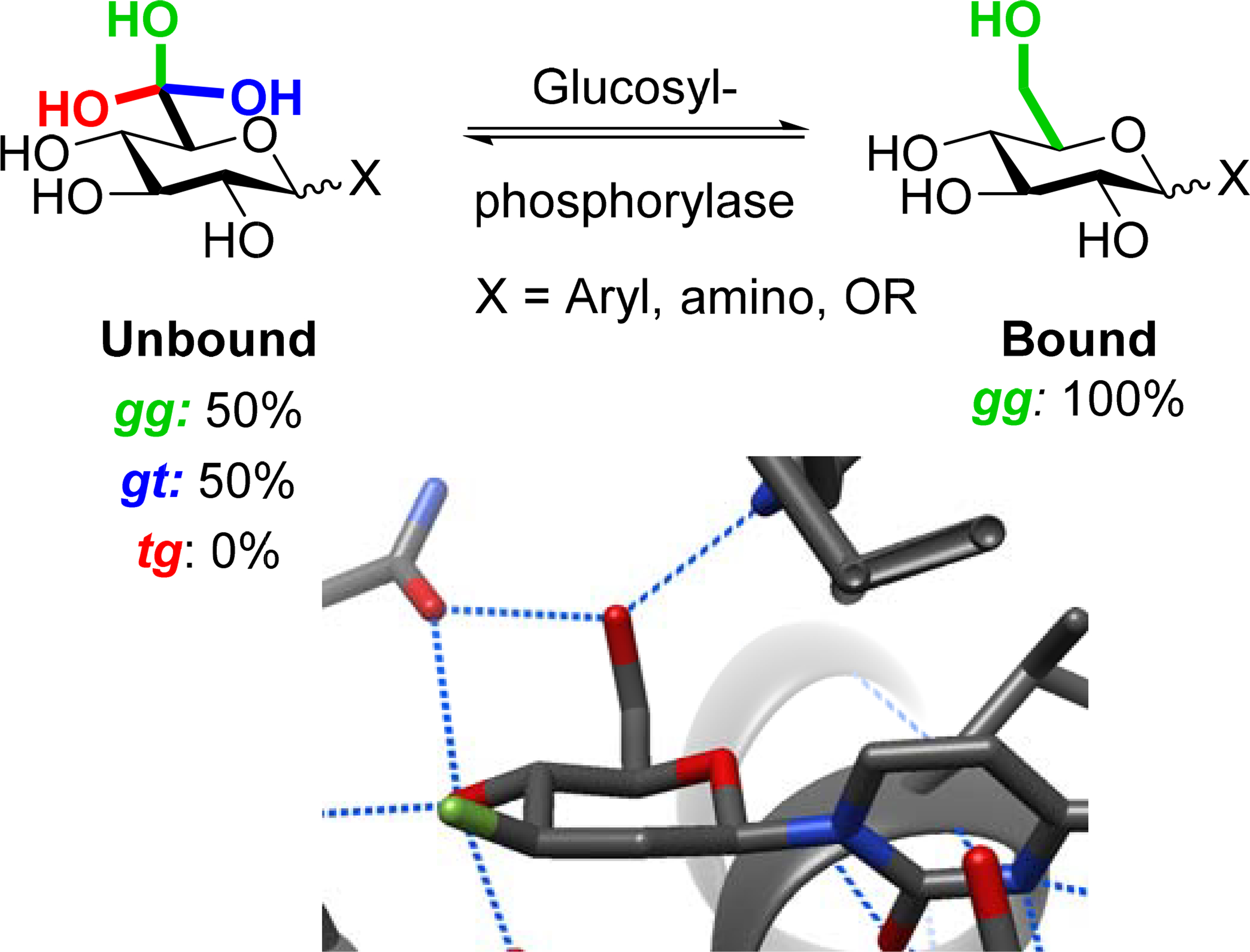

Turning to the glycoside phosphorylases, which catalyze both phosphorolytic cleavage of glycosidic linkages and glycosylation of anomeric phosphate-bearing donors, we located 136 crystal structures of hexopyranoside ligands bound to the donor subsite. In every non-ambiguous crystal structure located, the ligand side chain is restricted to the gg conformation through hydrogen-bonding with the enzyme, which is in stark contrast with the side chain populations of glucosides observed in free solution (Table 2 and Scheme 4). Clearly these enzymes have evolved to take advantage of the increased reactivity imposed by the gg conformation as an adjunct to catalysis.

Table 2.

Side chain conformations of ligands bound to glycoside phosphorylasesa

| Enzyme Function | gg | gt | tg | Eclipsed | Total | H-bonds to O6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Glucoside Phosphorylase | 126 (66) | - | - | - | 126 (66) | 126 (66) |

| β-Glucoside Phosphorylase | 3 (2) | - | - | - | 4 (2)b | 4 (2) |

| α-Mannoside Phosphorylase | 6 (5) | - | - | - | 6 (5) | 6 (5) |

| Total | 135 (73) | - | - | - | 136 (73) | 136 (73) |

Data are listed at the 2.50 Å cutoff, with those for the 2.00 Å cutoff given in parentheses

One structure bears an ambiguous side chain conformation

Scheme 4.

Bound and unbound side chain populations of non-hydrolyzable glucose derivatives as exemplified by rabbit muscle glycogen phosphorylase (PDB ID 3L7D)

Our CAZy-assisted search of the PDB for transglycosidases carrying substrates at the −1 site, conducted analogously and with the same constraints as that for GT-substrate complexes, unearthed a total of 54 structures. These are comprised of mainly α-glucosyl transglycosidases with a smaller number of β-glucosyl transglycosidases and trans-sialidases, with high preference (71%, 74%, and 100% respectively) for binding the ligand with the gg conformation of the side chain. Only five structures were identified bound with the gt conformation of the side chain, three with an eclipsed conformation, and none with the tg conformation (Table 3). Not surprisingly in view of their evolutionary relationship, this pattern closely resembles that found in the α- and β-glucosidases and differs significantly from that in the free sugars (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Side chain conformations of ligands bound to transglycosidasesa

| Enzyme Function | gg | gt | tg | Eclipsed | Total | H-bonds to O6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Glucoside transglycosidase | 29 (15) | 4 (2) | - | 2 (−) | 41 (21)b | 29 (16) |

| β-Glucoside transglycosidase | 7 (6) | 1 (1) | - | 1 (1) | 9 (8) | 6 (5) |

| Trans-sialidase | 4 (4) | - | - | - | 4 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Total | 40 (25) | 5 (3) | - | 3 (1) | 54 (33) | 37 (23) |

Data are listed at the 2.50 Å cutoff, with those for the 2.00 Å cutoff given in parentheses

Six structures bear ambiguous side chain conformations

Like the retaining GHs, the transglycosidases offer the possibility of characterization of the covalent enzyme-bound substrate intermediate between the two steps. Cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase, for which the covalently trapped intermediate has been studied crystallographically by Dijkstra and coworkers, is a case in point.62 In the covalently bound 4-deoxymaltotriose the residue β-linked to the nucleophilic aspartate in the −1 site has the side chain held in the gg conformation by hydrogen bonding to the protein (PDB 1CXL). Sufficiently well-resolved structures at the level of the enzyme substrate complex employ γ-cyclodextrin (PDB 1D3C)63 and maltobiose (PDB 1PJ9),64 whose side chains are both bound in the gg conformation in the −1 site. An acarbose-derived inhibitor is also bound in the −1 site with the side chain in a conformation that is formally analogous to the gg conformation in a saturated pyranose ring (PDB 1KCK).65 Thus, reinforcing the general notion that side chain restriction begins at the level of the enzyme-substrate complex, inverting cyclodextrin glycosyltransferases bind their substrates, transition states, and covalent intermediates all with the gg conformation (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Partial structures of (a) a cyclodextrin substrate, (b) an inhibitor, and (c) a covalent intermediate in the −1 site of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferases, all with gg side chain conformations.

As a control, analogously to the preceding GH study, we examined the side chain conformations of ligands bound to alternate subsites of the GTs, glycoside phosphorylases, and transglycosidases (Table 4), again curating the data by Privateer analysis. Although the data set is more limited than that developed for the GHs, it is readily apparent that differences in global side chain populations exist for ligands bound in GT donor sites and alternate sugar binding sites for α- and β-glucosides as well as for the β-galactosides. Together with the obvious differences in side chain population between the donor site-bound ligands and free sugars (Figure 1),28, 66–68 it is clear that GTs, glycoside phosphorylases, and transglycosidases employ restriction of donor side chain conformation as a means of transition state optimization. In passing we note the more diverse populations adopted by ligand side chains in alternate GT binding sites do not preclude any other site from preferentially binding a specific conformation. Thus, Hindsgaul and coworkers previously demonstrated preferential recognition of acceptor alcohols on conformational restriction of the side chain to the gg conformation by N-acetylglucosamine transferase V.69, 70

Table 4.

Comparison of side chain conformations at donor sites of Leloir GTs, glycoside phosphorylases, and transglycosidases with those at alternate sitesa

| Sugar | Position | gg | gt | tg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Galactosides | Leloir Donor Site | - | - | 8 (3) |

| Alt. Sites | - | 16 (14) | - | |

| α-Glucosides | Leloir Donor Site | 30 (15) | 3 (3) | 1 (−) |

| Phos. Donor Site | 126 (66) | - | - | |

| Transglycos. −1 Site | 29 (15) | 4 (2) | - | |

| Alt. Sites | 46 (19) | 28 (18) | 1 (−) | |

| β-Glucosides | Leloir Donor Site | 10 (6) | - | 1 (1) |

| Phos. Donor Site | 3 (2) | - | - | |

| Transglycos. −1 Site | 7 (6) | 1 (1) | - | |

| Alt. Sites | 26 (21) | 18 (11) | 2 (2) | |

| α -Mannosides | Leloir Donor Site | - | - | 1 (−) |

| Phos. Donor Site | 6 (5) | - | - | |

| Alt. Site | 1 (1) | - | - | |

| β-Mannosides | Leloir Donor Site | 2 (2) | - | - |

| Alt. Site | 2 (1) | - | - |

Data are listed at the 2.50 Å cutoff, with those for the 2.00 Å cutoff given in parentheses

Side chain restriction at the level of the enzyme-substrate complex by the GHs, GTs, glycoside phosphorylases, and transglycosidases is consistent with Namchuk and Withers’ kinetic analysis of A. faecalis β-glucosidase, which showed that enzyme-ligand H-bonding interactions involving the side chain hydroxymethyl group provide substantial ground state stabilization in contrast to H-bonding interactions with the ring hydroxyl groups, which mainly impact the transition state.71 In effect, the entropic penalty for restricting the conformation of the side chain is paid in the form of ligand preorganization at the level of the enzyme-substrate complex, such that the contribution of the C6-O6 bond to increased transition state affinity is mainly enthalpic, consistent with Wolfenden’s proposals.44, 72, 73 Note that substrate preorganization in this manner is distinct from the more familiar concept of substrate binding in a high energy conformation in which the reactive groups are preorganized for bond formation.74–77 With the side chain preorganized into the gg, and to a lesser extent the gt conformation, it can be expected to stabilize the transition state for glycosyl transfer comparably to the axial C4-O4 bond in galactosyl substrates.

The recognition of side chain conformation as a contributing factor to transition state stabilization by GTs opens up a new avenue for the development of a next generation of inhibitors designed to take advantage of the inherent binding preference of the glycosyltransferases. A clue as to how this might be achieved is provided by the E. coli heptosyltransferase WaaC, which processes the natural substrate78 ADP-L-glycero-β-D-manno-heptose (6) ten times more effectively than the side chain isomer ADP-D-glycero-β-D-manno-heptose (7).79 Crystallographic studies by Ducruix and coworkers revealed that the substrate analog ADP-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-L-glycero-β-D-gluco-heptose, whose side chain is predicted to take up the gg conformation in free solution,80 is bound in the active site with its side chain held in the gg conformation by hydrogen bonding to lysine 192 (Figure 8).81 The less effective substrate with the D-glycero-D-manno- configuration on the other hand is predicted to adopt the gt conformation of the side chain in solution,80 which, if maintained at the transition state, necessarily places the hydroxymethyl group uncomfortably close to Lys 192. Alternatively, rotation of the side chain in the D-glycero-D-manno- isomer into the gg conformation so as to pick up the H-bond to Lys 192 and provide additional transition state stabilization would place the hydroxymethyl group in a disfavored 1,5-syn-relationship to the C4-O4 and in proximity to Asp 261.

Figure 8.

Solution conformations of (a) ADP-L-glycero-β-D-manno-heptose (6) and (b) ADP-D-glycero-β-D-manno-heptose (7) and (c) ADP-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-L-glycero-β-D-gluco-heptose bound to E. coli WaaC (PDB ID 2H1H) in the gg conformation.

A further example of the effectiveness of side chain conformational control in Nature is provided by the natural glycosidase inhibitors castanospermine (8) and 1-deoxynojiromycin (9) (Figure 9). The former, whose side chain is locked in the gg conformation by the ethylene bridge has fourfold greater affinity for the Thermotoga maritima β-glucosidase than the latter,82 whose side chain is freely rotating in the solution phase but which is restricted to the gg conformation when bound to glycosidases.37, 83 Clearly, depending on the targeted enzyme, it should be possible to design improved and possibly more selective inhibitors by incorporation of side chain conformation biasing elements such as the fused ring in 8, or even by adding a simple methyl or substituted methyl group as in 6.

Figure 9.

Glycosidase inhibitors (a) castanospermine 8 and (b) 1-deoxynojiromcyin 9 and (c) 9 bound to T. maritima β-glucosidase in the gg conformation (PDB ID 2J77)

Conclusion

We demonstrate that GTs, glycoside phosphorylases, and transglycosidases mimic their GH counterparts in the restriction of substrate side chain conformations. Glucosyltransferases show a strong tendency for binding their substrates in the gg conformation, thereby maximizing transition state stabilization. α-Galactosyltransferases restrict their substrates predominantly to the second-most stabilizing gt conformation, avoiding the energetic penalty of the gg conformation in galactosyl pyranosides, while β-galactosyltransferases bind their substrates in the least reactive tg conformation. The restriction of side chain conformation in course of glycosidic bond formation and/or cleavage by the respective enzymes, although not without occasional exceptions, is therefore a broad general principle of which consideration should inform the design of improved and more selective inhibitors. For example, the locking of side chain in a given inhibitor to the gg conformation will enhance selectivity for glucose and mannose processing enzymes over galactose processing enzymes, while restriction to either the gt or tg conformations will achieve the opposite effects and could even provide selectivity between the different classes of galactose processing enzyme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

We thank the NIH (GM62160) for support of this work. Graphics were generated using UCSF Chimera, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from NIH P41-GM103311.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Additional information on Privateer analysis, table of raw crystal structure data, table of bound side chain conformations for each family, and table of families encompassed by each enzyme category. This information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

References

- 1.Ardèvol A; Iglesias-Fernández J; Rojas-Cervellera V; Rovira C, The Reaction Mechanism of Retaining Glycosyltransferases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breton C; Fournel-Gigleux S; Palcic MM, Recent Structures, Evolution and Mechanisms of Glycosyltransferases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012, 22, 540–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang A; Singh S; Phillips GN; Thorson JS, Glycosyltransferase Structural Biology and its Role in the Design of Catalysts for Glycosylation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 800–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bissaro B; Monsan P; Fauré R; O’Donohue MJ, Glycosynthesis in a Waterworld: New Insight into the Molecular Basis of Transglycosylation in Retaining Glycoside Hydrolases. Biochem. J. 2915, 467, 17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hecht S, Bioorganic Chemistry: Carbohydrates. Oxford University Press: New York, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hung S-C; Zulueta MML, Glycochemical Synthesis: Strategy and Applications. John Wiley & Sons Inc: New Jersey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krasnova L; Wong C-H, Oligosaccharide Synthesis and Translational Innovation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3735–3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walt DR; Aoki-Kinoshita KF; Bendiak B; Bertozzi CR; Boons G-J; Darvill A; Hart GW; Kiessling LL; Lowe J; Moon R; Paulson J; Sasisekharan R; Varki AP; Wong C-H Transforming Glycoscience: A Roadmap for the Future; National Research Council: Washington, DC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies GJ; Planas A; Rovira C, Conformational Analyses of the Reaction Coordinate of Glycosidases. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colombo C; Bennet AJ, Probing Transition State Analogy in Glycoside Hydrolase Catalysis. Adv. Phys. Org. Chem. 2017, 51, 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Withers SG; Davies GJ, The Case of the Missing Base. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 952–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauvage E; Terrak M, Glycosyltransferases and Transpeptidases/Penicillin-Binding Proteins: Valuable Targets for New Antibacterials. Antibiotics 2016, 5, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tedaldi L; Wagner GK, Beyond Substrate Analogues: New Inhibitor Chemotypes for Glycosyltransferases. MedChemComm 2014, 5, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kajimoto T; Node M, Synthesis of Glycosyltransferase Inhibitors. Synthesis 2009, 3179–3210. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Videira PA; Marcelo F; Grewal RK, Glycosyltransferase Inhibitors: A Promising Strategy to Pave a Path from Laboratory to Therapy. Carbohydr. Chem. 2018, 43, 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakai H; Kitaoka M; Svensson B; Ohtsubo K. i., Recent Development of Phosphorylases Possessing Large Potential for Oligosaccharide Synthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitaoka M; Hayashi K, Carbohydrate-Processing Phosphorolytic Enzymes. Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 2002, 14, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bissaro B; Monsan P; Fauré R; O’Donohue, Michael J, Glycosynthesis in a Waterworld: New Insight into the Molecular Basis of Transglycosylation in Retaining Glycoside Hydrolases. Biochem. J. 2015, 467, 17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crich D, Mechanism of a Chemical Glycosylation Reaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1144–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zechel DL; Withers SG, Glycosidase Mechanisms: Anatomy of a Finely Tuned Catalyst. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adero PO; Amarasekara H; Wen P; Bohé L; Crich D, The Experimental Evidence in Support of Glycosylation Mechanisms at the SN1–SN2 Interface. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 8242–8284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Artola M; Wu L; Ferraz MJ; Kuo C-L; Raich L; Breen IZ; Offen WA; Codée JDC; van der Marel GA; Rovira C; Aerts JMFG; Davies GJ; Overkleeft HS, 1,6-Cyclophellitol Cyclosulfates: A New Class of Irreversible Glycosidase Inhibitor. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 784–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danby PM; Withers SG, Glycosyl Cations versus Allylic Cations in Spontaneous and Enzymatic Hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10629–10632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shamsi Kazem Abadi S; Tran M; Yadav AK; Adabala PJP; Chakladar S; Bennet AJ, New Class of Glycoside Hydrolase Mechanism-Based Covalent Inhibitors: Glycosylation Transition State Conformations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10625–10628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park Y; Harper KC; Kuhl N; Kwan EE; Liu RY; Jacobsen EN, Macrocyclic Bis-thioureas Catalyze Stereospecific Glycosylation Reactions. Science 2017, 355, 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colombo C; Bennet AJ, The Physical Organic Chemistry of Glycopyranosyl Transfer Reactions in Solution and Enzyme-catalyzed. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 53, 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hexopyranose side chains take up three staggered conformations: gauche,gauche (gg), gauche,trans (gt), and trans,gauche (tg), where the first and second terms denote the C6-O6 bond position relative to the C5-O5 and C4-C5 bonds respectively.

- 28.Bock K; Duus JO, A Conformational Study of Hydroxymethyl Groups in Carbohydrates Investigated by 1H NMR Spectroscopy. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 1994, 13, 513–543. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraser-Reid B; Wu Z; Andrews CW; Skowronski E; Bowen JP, Torsional Effects in Glycoside Reactivity: Saccharide Couplings Mediated by Acetal Protecting Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1434–1435. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dharuman S; Crich D, Determination of the Influence of Side-Chain Conformation on Glycosylation Selectivity Using Conformationally Restricted Donors. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 4535–4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen HH; Nordstrøm LU; Bols M, The Disarming Effect of the 4,6-Acetal Group on Glycoside Reactivity: Torsional or Electronic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9205–9213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crich D; Sun S, Direct Synthesis of β-Mannopyranosides by the Sulfoxide Method. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 1198–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moumé-Pymbock M; Furukawa T; Mondal S; Crich D, Probing the Influence of a 4,6-O-Acetal on the Reactivity of Galactopyranosyl Donors: Verification of the Disarming Influence of the trans–gauche Conformation of C5–C6 Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14249–14255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen HH; Bols M, Stereoelectronic Substituent Effects. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006, 39, 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith D; Woerpel K, Electrostatic Interactions in Cations and Their Importance in Biology and Chemistry. Org. Biomol. Chem 2006, 4, 1195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schramm VL, Transition States and Transition State Analogue Interactions with Enzymes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1032–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quirke JCK; Crich D, Glycoside Hydrolases Restrict the Side Chain Conformation of their Substrates to Gain Additional Transition State Stabilization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16965–16973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rojas-Cervellera V; Ardèvol A; Boero M; Planas A; Rovira C, Formation of a Covalent Glycosyl–Enzyme Species in a Retaining Glycosyltransferase. Chem. Eur, J. 2013, 19, 14018–14023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soya N; Fang Y; Palcic MM; Klassen JS, Trapping and Characterization of Covalent Intermediates of Mutant Retaining Glycosyltransferases. Glycobiology 2011, 21, 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lombard V; Golaconda Ramulu H; Drula E; Coutinho PM; Henrissat B, The Carbohydrate-active Enzymes Database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 42, D490–D495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agirre J; Iglesias-Fernández J; Rovira C; Davies GJ; Wilson KS; Cowtan KD, Privateer: Software for the Conformational Validation of Carbohydrate Structures. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 833–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hudson KL; Bartlett GJ; Diehl RC; Agirre J; Gallagher T; Kiessling LL; Woolfson DN, Carbohydrate–Aromatic Interactions in Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15152–15160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agirre J; Davies GJ; Wilson KS; Cowtan K, Carbohydrate Anomalies in the PDB. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 303–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gloster TM; Davies GJ, Glycosidase Inhibition: Assessing Mimicry of the Transition State. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 305–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qian X; Palcic MM, Glycosyl Transferase Inhibitors. In Carbohydrates in Chemistry and Biology. Part II: Biology of Saccharides, Ernst B; Hart GW; Sinaÿ P, Eds. Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2000; Vol. 3, pp 293–312. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zechel DL; Withers SG, Glycosyl Transferase Mechanisms. In Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry, Barton DHR; Nakanishi K; Meth-Cohn O, Eds. Pergamon: Oxford, 1999; Vol. 5, pp 279–314. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heightman TD; Vasella AT, Recent Insights into Inhibition, Structure, and Mechanism of Configuration-Retaining Glycosidases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 750–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nerinckx W; Desmet T; Piens K; Claeyssens M, An Elaboration on the Syn–anti Proton Donor Concept of Glycoside Hydrolases: Electrostatic Stabilisation of the Transition State as a General Strategy. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 302–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gagnon SML; Meloncelli PJ; Zheng RB; Haji-Ghassemi O; Johal AR; Borisova SN; Lowary TL; Evans SV, High Resolution Structures of the Human ABO(H) Blood Group Enzymes in Complex with Donor Analogs Reveal That the Enzymes Utilize Multiple Donor Conformations to Bind Substrates in a Stepwise Manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 27040–27052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McMahon CM; Isabella CR; Windsor IW; Kosma P; Raines RT; Kiessling LL, Stereoelectronic Effects Impact Glycan Recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2386–2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knirel YA; Sheelev SD; Perepelov AV, Higher Aldulosonic Acids: Components of Bacterial Glycans. Mendeleev, Commun. 2011, 21, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zunk M; Kiefel MJ, The Occurrence and Biological Significance of the α-Keto-Sugars Pseudaminic Acid and Legionaminic Acid within Pathogenic Bacteria. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 3413–3421. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kosma P, Recent Advances in Kdo-Glycoside Formation. Carbohydr. Chem. 2017, 42, 116–164. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dhakal B; Crich D, Synthesis and Stereocontrolled Equatorially Selective Glycosylation Reactions of a Pseudaminic Acid Donor: Importance of the Side-Chain Conformation and Regioselective Reduction of Azide Protecting Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15008–15015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ngoje P; Crich D, Stereocontrolled Synthesis of the Equatorial Glycosides of 3-Deoxy-D-manno-oct-2-ulosonic Acid (KDO): Role of Side Chain Conformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 7760–7764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ovchinnikova OG; Mallette e.; Koizumi A; Lowary TL; Kimber MS; Whitfield C, Bacterial β-Kdo Glycosyltransferases Represent a New Glycosyltransferase Family (GT99). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, E3120–E3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lira-Navarrete E; Iglesias-Fernández J; Zandberg WF; Compañón I; Kong Y; Corzana F; Pinto BM; Clausen H; Peregrina JM; Vocadlo DJ; Rovira C; Hurtado-Guerrero R, Substrate-Guided Front-Face Reaction Revealed by Combined Structural Snapshots and Metadynamics for the Polypeptide N-Acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8206–8210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albesa-Jové D; Sainz-Polo MA; Marina A; Guerin ME, Structural Snapshots of α−1,3-Galactosyltransferase with Native Substrates: Insight into the Catalytic Mechanism of Retaining Glycosyltransferase. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14853–14857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gómez H; Rojas R; Patel DJ; Tabak LA; Lluch JM; Masgrau L, A Computational and Experimental Study of O-Glycosylation. Catalysis by Human UDP-GalNAc Polypeptide:GalNAc Transferase-T2. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 2645–2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bobovská A; Tvaroska I; Kóna J, A Theoretical Study on the Catalytic Mechanism of the Retaining α−1,2-Mannosyltransferase Kre2p/Mnt1p: the Impact of Different Metal Ions on Catalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 4201–4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lazarus MB; Jiang J; Gloster TM; Zandberg WF; Whitworth GE; Vocadlo DJ; Walker S, Structural Snapshots of the Reaction Coordinate for O-GlcNAc Transferase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 966–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uitdehaag JCM; Mosi R; Kalk KH; van der Veen BA; Dijkhuizen L; Withers SG; Dijkstra BW, X-ray Structures Along the Reaction Pathway of Cyclodextrin Glycosyltransferase Elucidate Catalysis in the α-Amylase Family. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999, 6, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uitdehaag JCM; Kalk KH; van der Veen BA; Dijkhuizen L; Dijkstra BW, The Cyclization Mechanism of Cyclodextrin Glycosyltransferase (CGTase) as Revealed by a γ-Cyclodextrin-CGTase Complex at 1.8-Å Resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 34868–34876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leemhuis H; Rozeboom HJ; Dijkstra BW; Dijkhuizen L, Improved Thermostability of Bacillus circulans Cyclodextrin Glycosyltransferase by the Introduction of a Salt Bridge. Proteins 2004, 54, 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leemhuis H; Uitdehaag JCM; Rozeboom HJ; Dijkstra BW; Dijkhuizen L, The Remote Substrate Binding Subsite −6 in Cyclodextrin-glycosyltransferase Controls the Transferase Activity of the Enzyme via an Induced-fit Mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 1113–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rao VSR; Qasba PK; Balaji PV; Chandrasekaran R, Conformation of Carbohydrates. Harwood Academic Publishers: Amsterdam, 1998; p 359. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grindley TB, Structure and Conformation of Carbohydrates. In Glycoscience: Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Fraser-Reid B; Tatsuta K; Thiem J, Eds. Springer: Berlin, 2001; Vol. 1, pp 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marchessault RH; Perez S, Conformations of the Hydroxymethyl Group in Crystalline Aldohexopyranoses. Biopolymers 1979, 18, 2369–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Srivastava OP; Hindsgaul O; Shoreibah M; Pierce M Recognition of Oligosaccharide Substrates by N-Acetylglucosaminetransferase-V. Carbohydr. Res. 1988, 179, 137–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lindh I; Hindsgaul O, Synthesis and Enzymatic Evaluation of Two Conformatinally Restricted Trisaccharide Analogues as Substrates for N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Namchuk MN; Withers SG, Mechanism of Agrobacterium β-Glucosidase: Kinetic Analysis of the Role of Noncovalent Enzyme/Substrate Interactions. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 16194–16202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wolfenden R; Snider M; Ridgway C; Miller B, The Temperature Dependence of Enzyme Rate Enhancements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 7419–7420. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Snider MJ; Gaunitz S; Ridgway C; Short SA; Wolfenden R, Temperature Effects on the Catalytic Efficiency, Rate Enhancement, and Transition State Affinity of Cytidine Deaminase, and the Thermodynamic Consequences for Catalysis of Removing a Substrate “Anchor”. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 9746–9753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Page MI; Jencks WP, Entropic Contributions to Rate Accelerations in Enzymic and Intramolecular Reactions and the Chelate Effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1971, 68, 1678–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Menger FM, Enzyme Reactivity from an Organic Perspective. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993, 26, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Campbell AP; Tarasow TM; Massefski W; Wright PE; Hilvert D, Binding of a High-Energy Substrate Conformer in Antibody Catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA 1993, 90, 8663–8667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Preiswerk N; Beck T; Schulz JD; Milovník P; Mayer C; Siegel JB; Baker D; Hilvert D, Impact of Scaffold Rigidity on the Design and Evolution of an Artificial Diels-Alderase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 8013–8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gronow S; Oertelt C; Ervelä E; Zamyatina A; Kosma P; Skurnik M; Holst O, Characterization of the Physiological Substrate for Lipopolysaccharide Heptosyltransferases I and II. J. Endotoxin Res. 2001, 7, 263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zamyatina A; Gronow S; Oertelt C; Puchberger M; Brade H; Kosma P, Efficient Chemical Synthesis of the Two Anomers of ADP-L-glycero- and D-glycero-D-manno-Heptopyranose Allows the Determination of the Substrate Specificities of Bacterial Heptosyltransferases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 4150–4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pirrone MG; Gysin M; Haldimann K; Hobbie SN; Vasella A; Crich D, Predictive Analysis of the Side Chain Conformation of the Higher Carbon Sugars: Application to the Preorganization of the Aminoglycoside Ring 1 Side Chain for Binding to the Bacterial Ribosomal Decoding A Site. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 16043–16059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grizot S; Salem M; Vongsouthi V; Durand L; Moreau F; Dohi H; Vincent S; Escaich S; Ducruix A, Structure of the Escherichia coli Heptosyltransferase WaaC: Binary Complexes with ADP and ADP-2-Deoxy-2-fluoro Heptose. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 363, 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gloster TM; Madsen R; Davies GJ, Dissection of Conformationally Restricted Inhibitors Binding to a β-Glucosidase. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 738–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gloster TM; Meloncelli P; Stick RV; Zechel D; Vasella A; Davies GJ, Glycosidase Inhibition: An Assessment of the Binding of 18 Putative Transition-State Mimics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2345–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.