Abstract

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that cause illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and the 2019 novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19). Currently, there is no analyzed data to examine the outbreak of COVID-19 by continent and no determination of prevalence trends; this article reviews COVID-19 epidemiology and immunology. Original research, reviews, governmental databases, and treatment guidelines are analyzed to present the epidemiology and immunology of COVID-19. Reports from patients who were COVID-19 infected showed typical symptoms of neutrophilia, lymphopenia, and increased systemic inflammatory proteins of IL-6 and C reactive protein (CRP). These observations agree with the results of severe conditions of MERS or lethal cases of SARS, in which there is an increased presence of neutrophils and macrophages in the airways. Additionally, analyzed data showed that Europe (49.37%), the Americas (27.4%), and Eastern Mediterranean (10.07%) had the most cumulative total per 100,000 population confirmed cases, and Africa (6.9%), Western Pacific (3.46%), and South-East Asia (2.72%) had the lowest cumulative total per 100,000 population confirmed cases. In general, the trend lines showed that the number of confirmed cases (cumulative total) and deaths (cumulative total) would decrease eventually.

Abbreviation list: MERS, Middle east respiratory syndrome; SARS, Severe acute respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV, Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SARS-CoV, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, C reactive protein; WHO, World health organization; PHEIC, Public health emergency of international concern; ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; PAMPs, Pathogen-associated molecular patterns; PRRs, Pattern recognition receptors; TLR-3, Toll-like receptors 3; RIG-I, Retinoic acid-inducible gene I; MDA5, Melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5; CXCL10, C-X-C motif chemokine 10; MCP-1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; IP-10, Interferon gamma-induced protein 10; MIP, Macrophage inflammatory protein; ADE, Antibody-dependent enhancement; FcγR, Fcγ receptors; ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome; HLH, Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

Keywords: Coronaviruses, COVID-19, Epidemiology, Immunology

Introduction

In December 2019, unidentified pneumonia emerged in Wuhan, China, where many of the original patients had visited the seafood market of Wuhan. The isolation of the related virus from patients and subsequent molecular analyses indicated a 2019 novel coronavirus infection, which was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1,2,70]. The explosive growth of COVID-19 infection in January 2020 necessitated that the WHO declare this outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) [3,4].

Unfortunately, international travel spread the virus worldwide, and 192,284,207 confirmed cases, including 4,136,518 deaths, were reported by the WHO on 23 July 2021. After the shocking health threat from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), a significant negative impact was felt on affected countries' economies. Searches on SARS-CoV showed a ‘bat’ origin and the transmission to humans via Himalayan palm civets (Paguma larvata) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) [[5], [6], [7], [8],71]. Afterward, the well-known Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) emerged with rare transmission to humans with a higher fatality rate. Alpha and beta coronaviruses dispersed in China are mainly and naturally carried in bats. The study of the genetic diversity and molecular evolution of these coronaviruses has gained intense interest [[9], [10], [11]].

Due to the many human casualties caused by the COVID-19 in a short time around the world, many scientists sought to find the infection's mechanism and to collect the following demographic data. There is, however, no analyzed data to study the course of the disease and its prevalence trend. Therefore, this study reviewed COVID-19 epidemiology and immunology using original research, reviews, governmental databases, and treatment guidelines.

Epidemiology of COVID-19

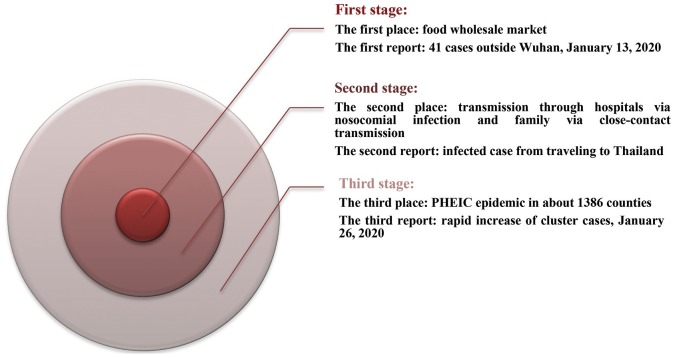

The COVID-19 epidemic started with the first announcement on Feb. 20, 2020, of the fatalities (2239 cases) in China, including 75 cases on the mainland, 68 in Hong Kong, 10 in Macao, 26 in Taiwan, and the confirmed reports (1200 cases) elsewhere [12]. Three stages can roughly be observed from the epidemiology of COVID-19 (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Three stages of COVID-19 epidemiology.

Total information

In the first stage, the epidemiologic analysis showed close contact was the key factor in-person-to-person transmission [13,14]. In the second stage, the reported cases outside Wuhan, in Beijing City and Guangdong indicated the spread of the virus, with the total number of infected cases rising to 205. Then 29 provinces of China and six countries conveyed 846 confirmed reports with an increase of 20 times faster than the first stage. Even though Wuhan's lock-down was implemented, more than 5 million people had already left Wuhan due to the Chinese New Year. In the third stage, 50–80% of all confirmed cases were clustered around Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Shandong on Feb. 10, 2020 [15]. When the numbers increased 240 times and reached 9826 confirmed cases, the WHO declared PHEIC. About 44,730 infected cases and 16,067 suspected cases were recorded in 1386 counties and regions in China on Feb. 11, 2020 [16]. In this stage, the fatality rate was high in China (1114 reported deaths) and low outside China (one fatality in the Philippines). With the growth of new clinical definitions for diagnosis, the confirmed cases bounded to 14,840 in China. In contrast, 60,329 reported cases were recognized in 25 countries, with a 1471 times increase since the last report [15].

Regrettably, as of Feb. 11, 2020, 1716, medical-related staff from 422 medical institutions were infected. Among them, 64% were infected in Wuhan city and 23.3% in the rest of Hubei [17]. Preliminary evaluation of the dynamics of COVID-19 transmission indicated the basic reproductive number of about 1.4–3.9 for COVID-19 [18]. The R0 of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV was 2.3–3.7 and 0.50–0.92 respectively in the absence of interventions [19]. The weekly operational reports of the WHO until July 23, 2021is given in Table 1 . The July 23, 2021 report of the WHO showed 192,284,207 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 4,136,518 deaths.

Table 1.

A short list of weekly WHO reports about COVID-19 ending Feb. 8, 2021.

| Date of report | Confirmed cases | Deaths | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dec. 7, 2020 | 66,243,918 | 1,528,984 | 1. WHO calls for global solidarity to maintain HIV services. |

| 2. WHO and the Iraqi Governorate of Ninewa has established an isolation unit at Hamam Aleel Field Hospital to treat suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19. | |||

| 3. As of Dec. 4, 2020, The Solidarity Response Fund has raised or committed more than US$ 238 million. | |||

| 4. WHO announced the recent launch of the Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan (SPRP) Monitoring and Evaluation Dashboard. | |||

| Dec. 14, 2020 | 70,461,926 | 1,599,704 | 1. Landmark alliance launches in Africa to fight COVID-19 misinformation. |

| 2. Nepal enhances laboratory capacity for COVID-19 and influenza. | |||

| 3.'WHO's Contingency Fund for Emergencies (CFE) provided $8.9 million for COVID-19 preparedness and response worldwide. | |||

| Dec. 21, 2020 | 75,704,857 | 1,690,061 | 1. PAHO prepares for COVID-19 vaccine deployment. |

| 2. Joint Intra-Action Review carried out in the Republic of Moldova in collaboration with the Ministry of Health Labour and Social Protection. | |||

| 3. WHO and IFRC sign a memorandum of understanding based on the EMT Initiative. | |||

| Jan. 11, 2021 | 88,828,387 | 1,926,625 | 1. As of Dec. 18, 2020, The Solidarity Response Fund has raised or committed more than US$ 240 million. |

| 2. Islamic Republic of Iran tackles COVID-19 by enhancing primary health care. | |||

| 3. WHO Country Office in Montenegro supports COVID-19 response and continuity of essential health services. | |||

| Jan. 19, 2021 | 93,956,883 | 2,029,084 | 1. WHO supports the installation of public address systems at 50 remote health centers in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. |

| 2. WHO SEAR countries gear up for massive vaccination campaign – this time for COVID-19 virus. | |||

| 3. US$ 50 million Iran COVID-19 Emergency Response Project (ICERP) scales up nationwide response to the epidemic. | |||

| Jan. 26, 2021 | 98,925,221 | 2 127,294 | 1. WHO works with Romania’s Ministry of Health and health professionals in the country to make telemedicine. |

| 2. WHO Afghanistan continues to strengthen COVID-19 testing capacity across the country. | |||

| 3. Vaccination Deployment Readiness map was launched on the Partners Platform. | |||

| Feb. 1, 2021 | 102,399,513 | 2, 217,005 | 1. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) launched a mobile application, MedPPE. |

| 2. WHO-led UN Crisis-Management Team coordinating 23 UN entities across nine areas of work. | |||

| 3. Mauritius conducts a COVID-19 vaccine simulation exercise before the national vaccine roll-out. | |||

| Feb. 8, 2021 | 105,394,301 | 2,302,302 | 1. WHO-led UN Crisis-Management Team coordinating 23 UN entities across nine areas of work. |

| 2. WHO launches EARS, an AI-powered public-access social listening tool. | |||

| 3. Countries submit vaccination plans for consideration of the next round of allocation. |

Geographic distribution, confirmed cases, and related deaths

Globally, over 192 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported by the WHO until July 23, 2021. The updated data from confirmed cases and related deaths worldwide can be found on the WHO website. Since the first reports of cases from Wuhan at the end of 2019, cases have been reported in all continents except Antarctica. The number of confirmed cases and related deaths are reported in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Geographic distribution, confirmed cases and related deaths as of July 23, 2021.

| WHO Region | Country | Cases - cumulative total | CCT | CNR (7D) | CNRPP | CNR (24 h) | Deaths - cumulative total | DCT | DNR (7D) | DNRPP | DNR (24 h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Algeria | 158,213 | 360.8 | 8307 | 18.94 | 1208 | 4008 | 9.14 | 113 | 0.26 | 14 |

| Angola | 41,405 | 125.98 | 875 | 2.66 | 178 | 977 | 2.97 | 26 | 0.08 | 4 | |

| Benin | 8324 | 68.66 | 80 | 0.66 | 80 | 107 | 0.88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Botswana | 97,657 | 4152.74 | 11,524 | 490.04 | 5755 | 1375 | 58.47 | 101 | 4.29 | 47 | |

| Burkina Faso | 13,537 | 64.76 | 7 | 0.03 | 0 | 169 | 0.81 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Burundi | 6128 | 51.54 | 326 | 2.74 | 110 | 8 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cabo Verde | 33,452 | 6016.69 | 272 | 48.92 | 57 | 297 | 53.42 | 3 | 0.54 | 0 | |

| Cameroon | 81,871 | 308.41 | 404 | 1.52 | 0 | 1332 | 5.02 | 2 | 0.01 | 0 | |

| Central African Republic | 7147 | 147.98 | 5 | 0.1 | 0 | 98 | 2.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chad | 4965 | 30.23 | 6 | 0.04 | 0 | 174 | 1.06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Comoros | 4014 | 461.59 | −58 | −6.67 | 3 | 147 | 16.9 | 1 | 0.11 | 0 | |

| Congo | 13,117 | 237.71 | 184 | 3.33 | 0 | 176 | 3.19 | 4 | 0.07 | 0 | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 49,386 | 187.22 | 387 | 1.47 | 98 | 324 | 1.23 | 5 | 0.02 | 2 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 47,174 | 52.67 | 1963 | 2.19 | 308 | 1021 | 1.14 | 37 | 0.04 | 1 | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 8848 | 630.66 | 20 | 1.43 | 0 | 123 | 8.77 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Eritrea | 6480 | 182.72 | 98 | 2.76 | 7 | 32 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Eswatini | 21,880 | 1885.94 | 1187 | 102.31 | 144 | 735 | 63.35 | 37 | 3.19 | 5 | |

| Ethiopia | 278,105 | 241.91 | 662 | 0.58 | 146 | 4363 | 3.8 | 13 | 0.01 | 3 | |

| Gabon | 25,309 | 1137.11 | 64 | 2.88 | 0 | 163 | 7.32 | 1 | 0.04 | 0 | |

| Gambia | 7161 | 296.32 | 551 | 22.8 | 0 | 197 | 8.15 | 9 | 0.37 | 0 | |

| Ghana | 100,250 | 322.63 | 2136 | 6.87 | 276 | 819 | 2.64 | 13 | 0.04 | 1 | |

| Guinea | 24,823 | 189.02 | 438 | 3.34 | 13 | 195 | 1.48 | 10 | 0.08 | 0 | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 4117 | 209.2 | 119 | 6.05 | 9 | 74 | 3.76 | 4 | 0.2 | 0 | |

| Kenya | 195,111 | 362.85 | 4091 | 7.61 | 801 | 3826 | 7.12 | 80 | 0.15 | 15 | |

| Lesotho | 12,679 | 591.85 | 526 | 24.55 | 49 | 357 | 16.66 | 19 | 0.89 | 8 | |

| Liberia | 5404 | 106.85 | 98 | 1.94 | 0 | 148 | 2.93 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Madagascar | 42,631 | 153.95 | 114 | 0.41 | 3 | 941 | 3.4 | 5 | 0.02 | 0 | |

| Malawi | 46,417 | 242.64 | 4919 | 25.71 | 952 | 1410 | 7.37 | 109 | 0.57 | 21 | |

| Mali | 14,528 | 71.74 | 31 | 0.15 | 3 | 530 | 2.62 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mauritania | 23,223 | 499.46 | 1036 | 22.28 | 130 | 517 | 11.12 | 14 | 0.3 | 1 | |

| Mauritius | 3388 | 266.4 | 1024 | 80.52 | 207 | 19 | 1.49 | 1 | 0.08 | 0 | |

| Mayotte | 19,465 | 7134.87 | 14 | 5.13 | 5 | 174 | 63.78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mozambique | 105,866 | 338.71 | 11,133 | 35.62 | 2153 | 1221 | 3.91 | 164 | 0.52 | 31 | |

| Namibia | 114,400 | 4502.33 | 5044 | 198.51 | 495 | 2665 | 104.88 | 395 | 15.55 | 45 | |

| Niger | 5594 | 23.11 | 39 | 0.16 | 0 | 195 | 0.81 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Nigeria | 170,306 | 82.62 | 1232 | 0.6 | 184 | 2130 | 1.03 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Réunion | 34,615 | 3866.25 | 1320 | 147.43 | 0 | 266 | 29.71 | 10 | 1.12 | 0 | |

| Rwanda | 61,375 | 473.86 | 9750 | 75.28 | 1309 | 704 | 5.44 | 88 | 0.68 | 11 | |

| Saint Helena | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 2417 | 1102.85 | 17 | 7.76 | 0 | 37 | 16.88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Senegal | 54,820 | 327.4 | 6550 | 39.12 | 523 | 1256 | 7.5 | 47 | 0.28 | 10 | |

| Seychelles | 17,541 | 17835.83 | 307 | 312.16 | 0 | 79 | 80.33 | 11 | 11.18 | 0 | |

| Sierra Leone | 6206 | 77.8 | 84 | 1.05 | 5 | 117 | 1.47 | 4 | 0.05 | 1 | |

| South Africa | 234,2330 | 3949.39 | 89,090 | 150.21 | 14,858 | 68,625 | 115.71 | 2653 | 4.47 | 433 | |

| South Sudan | 10,917 | 97.53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 117 | 1.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Togo | 14,801 | 178.78 | 375 | 4.53 | 0 | 140 | 1.69 | 6 | 0.07 | 0 | |

| Uganda | 91,355 | 199.72 | 2275 | 4.97 | 193 | 2483 | 5.43 | 234 | 0.51 | 58 | |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 609 | 1.02 | 100 | 0.17 | 100 | 21 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Zambia | 189,731 | 1032.05 | 7602 | 41.35 | 1158 | 3196 | 17.38 | 205 | 1.12 | 34 | |

| Zimbabwe | 93,421 | 628.55 | 14,549 | 97.89 | 2301 | 2870 | 19.31 | 452 | 3.04 | 61 | |

| Americas | Anguilla | 113 | 753.23 | 2 | 13.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 1277 | 1304.01 | 10 | 10.21 | 2 | 42 | 42.89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Argentina | 479,8851 | 10617.92 | 96,194 | 212.84 | 14,632 | 102,818 | 227.49 | 2568 | 5.68 | 437 | |

| Aruba | 11,271 | 10556.73 | 86 | 80.55 | 15 | 109 | 102.09 | 1 | 0.94 | 0 | |

| Bahamas | 13,781 | 3504.44 | 446 | 113.42 | 0 | 274 | 69.68 | 13 | 3.31 | 0 | |

| Barbados | 4302 | 1497 | 89 | 30.97 | 10 | 48 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Belize | 13,865 | 3486.93 | 252 | 63.38 | 49 | 332 | 83.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 0 | |

| Bermuda | 2535 | 4070.79 | 8 | 12.85 | 0 | 33 | 52.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | 465,351 | 3986.55 | 7139 | 61.16 | 1174 | 17,546 | 150.31 | 201 | 1.72 | 41 | |

| Bonaire | 1661 | 7941.67 | 25 | 119.53 | 2 | 17 | 81.28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Brazil | 19,473,954 | 9161.65 | 264,225 | 124.31 | 54,517 | 545,604 | 256.68 | 8210 | 3.86 | 1424 | |

| British Virgin Islands | 2210 | 7308.93 | 279 | 922.71 | 0 | 23 | 76.07 | 19 | 62.84 | 0 | |

| Canada | 1,424,715 | 3774.86 | 2884 | 7.64 | 495 | 26,512 | 70.25 | 54 | 0.14 | 4 | |

| Cayman Islands | 629 | 957.09 | 9 | 13.69 | 2 | 2 | 3.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chile | 160,4713 | 8394.52 | 10,217 | 53.45 | 1859 | 34,792 | 182 | 585 | 3.06 | 181 | |

| Colombia | 4,679,994 | 9197.58 | 114,622 | 225.27 | 11,244 | 117,482 | 230.89 | 3145 | 6.18 | 351 | |

| Costa Rica | 395,667 | 7767.13 | 8945 | 175.59 | 1532 | 4925 | 96.68 | 83 | 1.63 | 10 | |

| Cuba | 308,599 | 2724.55 | 45,513 | 401.82 | 7745 | 2137 | 18.87 | 411 | 3.63 | 65 | |

| Curaçao | 12,962 | 7899.18 | 509 | 310.19 | 79 | 126 | 76.79 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Dominica | 209 | 290.31 | 10 | 13.89 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Dominican Republic | 338,902 | 3124.12 | 2758 | 25.42 | 611 | 3931 | 36.24 | 24 | 0.22 | 2 | |

| Ecuador | 478,615 | 2712.77 | 5893 | 33.4 | 0 | 30,752 | 174.3 | 8880 | 50.33 | 0 | |

| El Salvador | 84,144 | 1297.28 | 1781 | 27.46 | 1292 | 2529 | 38.99 | 59 | 0.91 | 10 | |

| Falkland Islands (Malvinas) | 60 | 1722.65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| French Guiana | 29,419 | 9849.61 | 705 | 236.04 | 134 | 170 | 56.92 | 7 | 2.34 | 1 | |

| Grenada | 165 | 146.64 | 2 | 1.78 | 0 | 1 | 0.89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Guadeloupe | 17,982 | 4494.11 | 173 | 43.24 | 0 | 278 | 69.48 | 4 | 1 | 0 | |

| Guatemala | 344,221 | 1921.35 | 16,466 | 91.91 | 3364 | 10,029 | 55.98 | 195 | 1.09 | 13 | |

| Guyana | 21,733 | 2763.07 | 510 | 64.84 | 65 | 515 | 65.48 | 12 | 1.53 | 1 | |

| Haiti | 19,762 | 173.31 | 135 | 1.18 | 0 | 523 | 4.59 | 11 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| Honduras | 284,187 | 2869.24 | 7198 | 72.67 | 1501 | 7535 | 76.08 | 179 | 1.81 | 28 | |

| Jamaica | 51,542 | 1740.6 | 629 | 21.24 | 138 | 1167 | 39.41 | 31 | 1.05 | 4 | |

| Martinique | 14,964 | 3987.58 | 2157 | 574.79 | 0 | 102 | 27.18 | 4 | 1.07 | 0 | |

| Mexico | 2,693,495 | 2089.07 | 76,668 | 59.46 | 15,198 | 237,207 | 183.98 | 1700 | 1.32 | 397 | |

| Montserrat | 21 | 420.08 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nicaragua | 7313 | 110.39 | 269 | 4.06 | 0 | 194 | 2.93 | 1 | 0.02 | 0 | |

| Panama | 425,599 | 9863.78 | 6995 | 162.12 | 1144 | 6723 | 155.81 | 62 | 1.44 | 7 | |

| Paraguay | 447,146 | 6269.1 | 6090 | 85.38 | 879 | 14,446 | 202.54 | 380 | 5.33 | 52 | |

| Peru | 2,097,811 | 6362.43 | 11,928 | 36.18 | 1798 | 195,429 | 592.71 | 677 | 2.05 | 97 | |

| Puerto Rico | 142,359 | 4976.1 | 1259 | 44.01 | 180 | 2566 | 89.69 | 7 | 0.24 | 1 | |

| Saba | 7 | 362.13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Saint Barthélemy | 1057 | 10692.97 | 5 | 50.58 | 0 | 1 | 10.12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 557 | 1047.15 | 13 | 24.44 | 0 | 3 | 5.64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Saint Lucia | 5496 | 2993.02 | 57 | 31.04 | 12 | 87 | 47.38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Saint Martin | 2523 | 6526.29 | 51 | 131.92 | 0 | 30 | 77.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Saint Pierre and Miquelon | 28 | 483.18 | 2 | 34.51 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 2266 | 2042.55 | 8 | 7.21 | 3 | 12 | 10.82 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sint Eustatius | 20 | 637.15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sint Maarten | 2695 | 6284.69 | 39 | 90.95 | 8 | 34 | 79.29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Suriname | 24,490 | 4174.68 | 774 | 131.94 | 55 | 625 | 106.54 | 28 | 4.77 | 5 | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 36,626 | 2617.1 | 1390 | 99.32 | 272 | 1003 | 71.67 | 40 | 2.86 | 3 | |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 2459 | 6351.05 | 15 | 38.74 | 1 | 18 | 46.49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| United States of America | 33,875,385 | 10234.17 | 231,856 | 70.05 | 0 | 604,546 | 182.64 | 1376 | 0.42 | 0 | |

| United States Virgin Islands | 4286 | 4104.38 | 167 | 159.92 | 37 | 33 | 31.6 | 1 | 0.96 | 0 | |

| Uruguay | 379,613 | 10928.11 | 1909 | 54.96 | 237 | 5905 | 169.99 | 51 | 1.47 | 9 | |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 295,746 | 1040.04 | 7647 | 26.89 | 1019 | 3426 | 12.05 | 99 | 0.35 | 18 | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | Afghanistan | 143,439 | 368.47 | 4388 | 11.27 | 256 | 6357 | 16.33 | 285 | 0.73 | 32 |

| Bahrain | 268,092 | 15755.52 | 473 | 27.8 | 0 | 1381 | 81.16 | 2 | 0.12 | 0 | |

| Djibouti | 11,628 | 1176.92 | 6 | 0.61 | 0 | 155 | 15.69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Egypt | 283,862 | 277.39 | 372 | 0.36 | 0 | 16,465 | 16.09 | 40 | 0.04 | 0 | |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 3,623,840 | 4314.46 | 159,785 | 190.24 | 20,313 | 88,063 | 104.85 | 1471 | 1.75 | 226 | |

| Iraq | 1,526,943 | 3796.24 | 60,414 | 150.2 | 8106 | 18,101 | 45 | 394 | 0.98 | 81 | |

| Jordan | 762,706 | 7475.21 | 3020 | 29.6 | 0 | 9922 | 97.24 | 50 | 0.49 | 0 | |

| Kuwait | 388,881 | 9106.07 | 6797 | 159.16 | 0 | 2255 | 52.8 | 81 | 1.9 | 0 | |

| Lebanon | 552,328 | 8092.19 | 2901 | 42.5 | 0 | 7888 | 115.57 | 6 | 0.09 | 0 | |

| Libya | 227,433 | 3309.9 | 12,865 | 187.23 | 732 | 3322 | 48.35 | 73 | 1.06 | 13 | |

| Morocco | 566,356 | 1534.4 | 16,512 | 44.74 | 0 | 9498 | 25.73 | 80 | 0.22 | 0 | |

| occupied Palestinian territory, including east Jerusalem | 344,717 | 6757.28 | 372 | 7.29 | 0 | 3859 | 75.65 | 6 | 0.12 | 0 | |

| Oman | 289,042 | 5660.14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3498 | 68.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pakistan | 998,609 | 452.08 | 17,402 | 7.88 | 2158 | 22,928 | 10.38 | 239 | 0.11 | 40 | |

| Qatar | 224,834 | 7803.88 | 923 | 32.04 | 196 | 600 | 20.83 | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 514,446 | 1477.7 | 8321 | 23.9 | 1162 | 8130 | 23.35 | 95 | 0.27 | 15 | |

| Somalia | 15,162 | 95.4 | 77 | 0.48 | 0 | 781 | 4.91 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sudan | 37,138 | 84.69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2776 | 6.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 25,849 | 147.7 | 35 | 0.2 | 0 | 1905 | 10.89 | 3 | 0.02 | 0 | |

| Tunisia | 555,997 | 4704.42 | 29,510 | 249.69 | 0 | 17,913 | 151.57 | 904 | 7.65 | 0 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 667,080 | 6744.72 | 10,726 | 108.45 | 1547 | 1910 | 19.31 | 25 | 0.25 | 3 | |

| Yemen | 6997 | 23.46 | 30 | 0.1 | 0 | 1371 | 4.6 | 5 | 0.02 | 0 | |

| Europe | Albania | 132,797 | 4614.53 | 168 | 5.84 | 34 | 2456 | 85.34 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Andorra | 14,464 | 18719.99 | 225 | 291.21 | 85 | 127 | 164.37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Armenia | 228,382 | 7707.19 | 1271 | 42.89 | 221 | 4579 | 154.53 | 21 | 0.71 | 4 | |

| Austria | 650,776 | 7311.22 | 2529 | 28.41 | 421 | 10,523 | 118.22 | 1 | 0.01 | 0 | |

| Azerbaijan | 339,274 | 3346.17 | 1473 | 14.53 | 212 | 4999 | 49.3 | 9 | 0.09 | 1 | |

| Belarus | 437,664 | 4631.7 | 6552 | 69.34 | 1069 | 3365 | 35.61 | 68 | 0.72 | 10 | |

| Belgium | 1,112,161 | 9652.13 | 7896 | 68.53 | 1 | 25,217 | 218.85 | 8 | 0.07 | 2 | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 205,384 | 6260.15 | 117 | 3.57 | 39 | 9673 | 294.84 | 8 | 0.24 | 2 | |

| Bulgaria | 423,440 | 6091.36 | 643 | 9.25 | 121 | 18,189 | 261.66 | 26 | 0.37 | 2 | |

| Croatia | 362,305 | 8927.8 | 956 | 23.56 | 176 | 8245 | 203.17 | 11 | 0.27 | 0 | |

| Cyprus | 95,307 | 10732.71 | 6850 | 771.39 | 1046 | 398 | 44.82 | 15 | 1.69 | 4 | |

| Czechia | 1,672,140 | 15636.33 | 1557 | 14.56 | 207 | 30,347 | 283.78 | 12 | 0.11 | 0 | |

| Denmark | 309,420 | 5313.97 | 5951 | 102.2 | 805 | 2542 | 43.66 | 2 | 0.03 | 0 | |

| Estonia | 132,262 | 9952.17 | 519 | 39.05 | 83 | 1271 | 95.64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Faroe Islands | 958 | 1960.5 | 44 | 90.04 | 0 | 1 | 2.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Finland | 102,042 | 1846.82 | 2450 | 44.34 | 412 | 978 | 17.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| France | 5,813,457 | 8938.37 | 95,742 | 147.21 | 21,769 | 110,566 | 170 | 104 | 0.16 | 10 | |

| Georgia | 398,081 | 9979.03 | 13,694 | 343.28 | 2460 | 5656 | 141.78 | 140 | 3.51 | 20 | |

| Germany | 3,752,592 | 4512.13 | 10,811 | 13 | 2089 | 91,492 | 110.01 | 155 | 0.19 | 34 | |

| Gibraltar | 4704 | 13962.19 | 218 | 647.06 | 33 | 94 | 279.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Greece | 469,042 | 4375.98 | 18,530 | 172.88 | 2601 | 12,875 | 120.12 | 56 | 0.52 | 5 | |

| Greenland | 85 | 149.72 | 19 | 33.47 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Guernsey | 908 | 1408.45 | 47 | 72.9 | 4 | 17 | 26.37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Holy See | 26 | 3213.84 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hungary | 809,101 | 8281.89 | 376 | 3.85 | 85 | 30,020 | 307.28 | 5 | 0.05 | 0 | |

| Iceland | 6967 | 1913.31 | 249 | 68.38 | 0 | 30 | 8.24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ireland | 289,139 | 5824.2 | 8355 | 168.3 | 1188 | 5026 | 101.24 | 8 | 0.16 | 0 | |

| Isle of Man | 2821 | 3317.57 | 1072 | 1260.7 | 182 | 29 | 34.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Israel | 857,554 | 9907.57 | 7040 | 81.34 | 365 | 6457 | 74.6 | 12 | 0.14 | 0 | |

| Italy | 4,302,393 | 7213.76 | 24,074 | 40.36 | 5056 | 127,920 | 214.48 | 80 | 0.13 | 15 | |

| Jersey | 7077 | 6565.18 | 1837 | 1704.14 | 215 | 69 | 64.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Kazakhstan | 568,915 | 3029.9 | 27,022 | 143.91 | 0 | 8538 | 45.47 | 365 | 1.94 | 0 | |

| Kosovo [1] | 107,911 | 6009.53 | 71 | 3.95 | 28 | 2255 | 125.58 | 1 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 155,005 | 2375.85 | 8713 | 133.55 | 1127 | 2227 | 34.13 | 73 | 1.12 | 10 | |

| Latvia | 138,344 | 7251.97 | 303 | 15.88 | 44 | 2549 | 133.62 | 8 | 0.42 | 0 | |

| Liechtenstein | 3174 | 8191.6 | 13 | 33.55 | 0 | 58 | 149.69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lithuania | 280,541 | 10040.51 | 969 | 34.68 | 245 | 4409 | 157.8 | 5 | 0.18 | 1 | |

| Luxembourg | 73,309 | 11708.68 | 677 | 108.13 | 94 | 821 | 131.13 | 2 | 0.32 | 0 | |

| Malta | 33,198 | 6451.68 | 1364 | 265.08 | 166 | 420 | 81.62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Monaco | 2744 | 6992.15 | 89 | 226.79 | 16 | 33 | 84.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Montenegro | 100,854 | 16057.97 | 243 | 38.69 | 0 | 1624 | 258.57 | 3 | 0.48 | 0 | |

| Netherlands | 1,827,273 | 10496.99 | 61,457 | 353.05 | 6301 | 17,789 | 102.19 | 16 | 0.09 | 3 | |

| North Macedonia | 155,981 | 7486.92 | 115 | 5.52 | 16 | 5489 | 263.47 | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | |

| Norway | 135,234 | 2519.46 | 1358 | 25.3 | 265 | 799 | 14.89 | 3 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| Poland | 2,881,948 | 7592.44 | 707 | 1.86 | 108 | 75,235 | 198.21 | 30 | 0.08 | 4 | |

| Portugal | 943,244 | 9161.35 | 23,044 | 223.82 | 3622 | 17,248 | 167.52 | 61 | 0.59 | 16 | |

| Republic of Moldova | 258,365 | 6404.74 | 599 | 14.85 | 128 | 6236 | 154.59 | 17 | 0.42 | 4 | |

| Romania | 1,082,057 | 5598.15 | 518 | 2.68 | 104 | 34,266 | 177.28 | 12 | 0.06 | 1 | |

| Russian Federation | 6,078,522 | 4165.24 | 170,523 | 116.85 | 23,811 | 152,296 | 104.36 | 5428 | 3.72 | 795 | |

| San Marino | 5107 | 15048.03 | 13 | 38.31 | 0 | 90 | 265.19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Serbia | 719,462 | 10386.79 | 1369 | 19.76 | 228 | 7095 | 102.43 | 17 | 0.25 | 3 | |

| Slovakia | 392,259 | 7187.03 | 225 | 4.12 | 40 | 12,534 | 229.65 | 10 | 0.18 | 0 | |

| Slovenia | 258,467 | 12332.26 | 421 | 20.09 | 69 | 4761 | 227.16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Spain | 4,249,258 | 8977.44 | 155,222 | 327.94 | 17,218 | 81,194 | 171.54 | 76 | 0.16 | 3 | |

| Sweden | 109,6341 | 10615.65 | 2434 | 23.57 | 582 | 14,651 | 141.86 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Switzerland | 708,703 | 8188.73 | 3636 | 42.01 | 5 | 10,329 | 119.35 | 1 | 0.01 | 0 | |

| Tajikistan | 14,761 | 154.77 | 316 | 3.31 | 0 | 117 | 1.23 | 6 | 0.06 | 0 | |

| The United Kingdom | 5,602,325 | 8252.55 | 321,223 | 473.18 | 39,315 | 128,980 | 189.99 | 387 | 0.57 | 84 | |

| Turkey | 5,563,903 | 6597.06 | 56,448 | 66.93 | 9586 | 50,761 | 60.19 | 346 | 0.41 | 52 | |

| Turkmenistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ukraine | 2,247,419 | 5138.87 | 3814 | 8.72 | 763 | 52,811 | 120.76 | 109 | 0.25 | 21 | |

| Uzbekistan | 122,786 | 366.86 | 4406 | 13.16 | 738 | 819 | 2.45 | 30 | 0.09 | 5 | |

| South-East Asia | Bangladesh | 1,146,564 | 696.2 | 62,642 | 38.04 | 6364 | 18,851 | 11.45 | 1386 | 0.84 | 166 |

| Bhutan | 2470 | 320.11 | 72 | 9.33 | 12 | 2 | 0.26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Democratic People's Republic of Korea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| India | 31,293,062 | 2267.61 | 266,233 | 19.29 | 35,342 | 419,470 | 30.4 | 6939 | 0.5 | 483 | |

| Indonesia | 3,082,410 | 1126.93 | 301,607 | 110.27 | 49,071 | 80,598 | 29.47 | 9201 | 3.36 | 1566 | |

| Maldives | 76,454 | 14143.9 | 718 | 132.83 | 0 | 218 | 40.33 | 2 | 0.37 | 0 | |

| Myanmar | 258,870 | 475.78 | 40,131 | 73.76 | 5506 | 6459 | 11.87 | 1923 | 3.53 | 326 | |

| Nepal | 676,708 | 2322.52 | 12,132 | 41.64 | 1982 | 9679 | 33.22 | 173 | 0.59 | 18 | |

| Sri Lanka | 291,298 | 1360.36 | 9238 | 43.14 | 0 | 3902 | 18.22 | 257 | 1.2 | 0 | |

| Thailand | 467,707 | 670.07 | 85,800 | 122.92 | 14,575 | 3811 | 5.46 | 712 | 1.02 | 114 | |

| Timor-Leste | 10,281 | 779.78 | 232 | 17.6 | 54 | 26 | 1.97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Western Pacific | American Samoa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Australia | 32,427 | 127.17 | 911 | 3.57 | 159 | 915 | 3.59 | 3 | 0.01 | 0 | |

| Brunei Darussalam | 311 | 71.09 | 29 | 6.63 | 2 | 3 | 0.69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cambodia | 70,419 | 421.19 | 5808 | 34.74 | 811 | 1188 | 7.11 | 163 | 0.97 | 20 | |

| China | 120,000 | 8.16 | 461 | 0.03 | 82 | 5630 | 0.38 | 23 | 0 | 4 | |

| Cook Islands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Fiji | 21,361 | 2382.86 | 7475 | 833.85 | 918 | 161 | 17.96 | 87 | 9.71 | 15 | |

| French Polynesia | 19,234 | 6847.08 | 176 | 62.65 | 39 | 145 | 51.62 | 1 | 0.36 | 1 | |

| Guam | 8231 | 4876.91 | 26 | 15.41 | 14 | 143 | 84.73 | 1 | 0.59 | 0 | |

| Japan | 857,799 | 678.23 | 26,606 | 21.04 | 5282 | 15,106 | 11.94 | 92 | 0.07 | 9 | |

| Kiribati | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 4119 | 56.61 | 1027 | 14.12 | 256 | 5 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.01 | 0 | |

| Malaysia | 964,918 | 2981.27 | 84,136 | 259.95 | 13,034 | 7574 | 23.4 | 961 | 2.97 | 134 | |

| Marshall Islands | 4 | 6.76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Micronesia (Federated States of) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mongolia | 152,539 | 4653.01 | 9411 | 287.07 | 0 | 755 | 23.03 | 48 | 1.46 | 0 | |

| Nauru | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| New Caledonia | 131 | 45.88 | 2 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| New Zealand | 2499 | 51.82 | 53 | 1.1 | 20 | 26 | 0.54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Niue | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Northern Mariana Islands (Commonwealth of the) | 188 | 326.63 | 1 | 1.74 | 0 | 2 | 3.47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Palau | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Papua New Guinea | 17,524 | 195.86 | 99 | 1.11 | 0 | 192 | 2.15 | 6 | 0.07 | 0 | |

| Philippines | 1,530,266 | 1396.47 | 39,614 | 36.15 | 5828 | 26,891 | 24.54 | 577 | 0.53 | 17 | |

| Pitcairn Islands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Republic of Korea | 185,733 | 362.27 | 10,687 | 20.84 | 1630 | 2066 | 4.03 | 15 | 0.03 | 3 | |

| Samoa | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Singapore | 63,791 | 1090.38 | 939 | 16.05 | 170 | 36 | 0.62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Solomon Islands | 20 | 2.91 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tokelau | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tonga | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tuvalu | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vanuatu | 3 | 0.98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Viet Nam | 78,269 | 80.41 | 35,981 | 36.96 | 7125 | 370 | 0.38 | 163 | 0.17 | 0 | |

| Wallis and Futuna | 454 | 4036.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 62.24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | Other | 764 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Total (Global) | 192,284,207 | 2466.908864 | 3,533,643 | 45.33485 | 483,475 | 4,136,518 | 53.06943 | 68,246 | 0.875562 | 8366 | |

CCT: Cases - cumulative total per 100,000 population, CNR (7D): Cases - newly reported in last seven days, CNRPP: Cases - newly reported in last seven days per 100,000 population, CNR (24 h): Cases - newly reported in last 24 h, DCT: Deaths - cumulative total per 100,000 population, DNR (7D): Deaths - newly reported in last seven days, DNRPP: Deaths - newly reported in last seven days per 100,000 population, DNR (24 h): Deaths - newly reported in last 24 h.

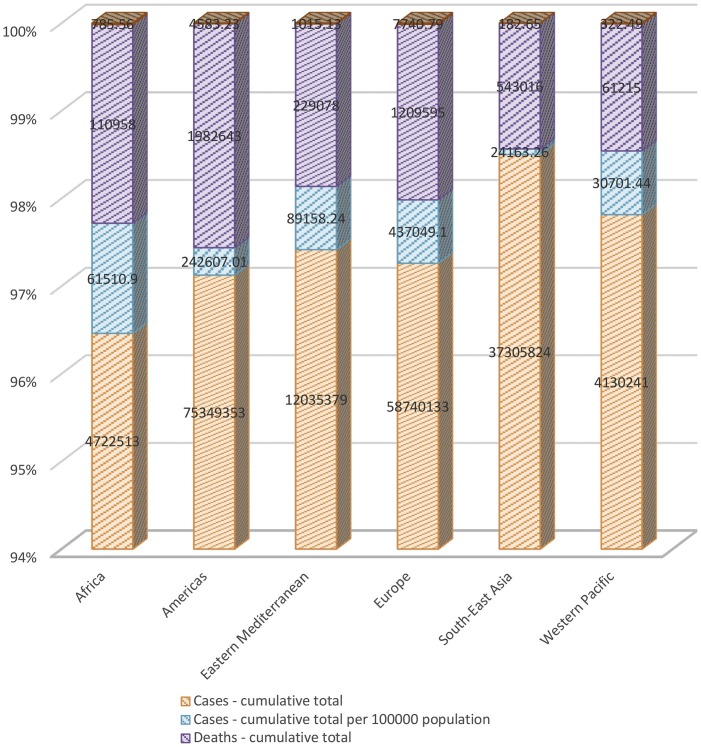

Table 3 shows that Europe (49.37%), the Americas (27.4%), and Eastern Mediterranean (10.07%) had the most cumulative total per 100,000 population confirmed cases until July 23, 2021, Africa (6.9%), Western Pacific (3.46%), and South-East Asia (2.72%) had the lowest cumulative total per 100,000 population confirmed cases. Until July 23, 2021, Europe (45.35%), the Americas (27.24%), and Africa (9.89%) had the most newly reported cases in the last seven days per 100,000 population confirmed cases. In the same period, Western Pacific (8.18%), Eastern Mediterranean (6.3%), and South-East Asia (3.01%) had the lowest newly reported cases in the last seven days per 100,000 population confirmed cases. Furthermore, Europe (52.91%), the Americas (31.32%), and Eastern Mediterranean (6.93%) had the most cumulative total per 100,000 population death cases until July 23, 2021, Africa (5.36%), Western Pacific (2.2%), and South-East Asia (1.24%) had the lowest cumulative total per 100,000 population death cases. Until July 23, 2021, the Americas (60.46%), Africa (17.18%), and Europe (7.14%) had the most newly reported death cases in the last seven days per 100,000 population. In the same period, Western Pacific (5.82%), Eastern Mediterranean (5.44%), and South-East Asia (3.92%) had the lowest newly reported death cases in the last seven days per 100,000 population.

Table 3.

Global distribution of confirmed cases and related deaths until July 23, 2021.

| WHO Region | Cases - cumulative total | CCT | CNR | CNRPP | Cases - newly reported in last 24 h | Deaths - cumulative total | DCT | DNR | DNRPP | Deaths - newly reported in last 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 4,722,513 | 61510.9 | 190,877 | 2000.1 | 33,821 | 110,958 | 785.56 | 4884 | 50.01 | 807 |

| Americas | 75,349,353 | 242,607 | 937,013 | 5504.45 | 121,309 | 1,982,643 | 4583.23 | 29,119 | 175.92 | 3161 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 12,035,379 | 89158.24 | 334,929 | 1273.74 | 34,470 | 229,078 | 1015.13 | 3760 | 15.85 | 410 |

| Europe | 58,740,133 | 437049.1 | 1,068,577 | 9164.82 | 145,599 | 1,209,595 | 7740.79 | 7749 | 20.79 | 1112 |

| South-East Asia | 37,305,824 | 24163.26 | 778,805 | 608.82 | 112,906 | 543,016 | 182.65 | 20,593 | 11.41 | 2673 |

| Western Pacific | 4,130,241 | 30701.44 | 223,442 | 1653.71 | 35,370 | 61,215 | 322.49 | 2141 | 16.95 | 203 |

| Total | 192,283,443 | 885,190 | 3,533,643 | 20205.64 | 483,475 | 4,136,505 | 14629.85 | 68,246 | 290.93 | 8366 |

CCT: Cases - cumulative total per 100,000 population, CNR: Cases - newly reported in last seven days, CNRPP: Cases - newly reported in last seven days per 100,000 population, DCT: Deaths - cumulative total per 100,000 population, DNR: Deaths - newly reported in last seven days, DNRPP: Deaths - newly reported in last seven days per 100,000 population.

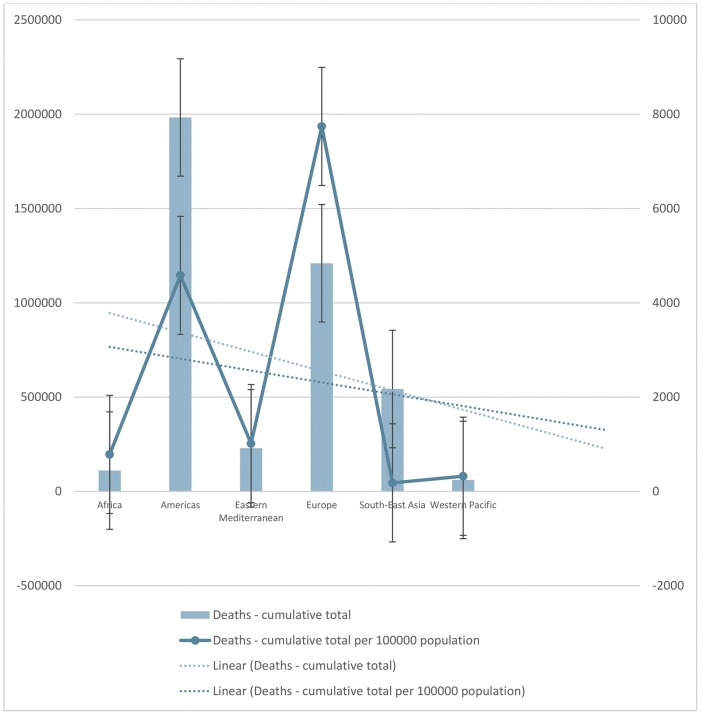

Notably, the confirmed cases-cumulative and confirmed cases-cumulative total per 100000 population in Africa, Eastern Mediterranean, Western Pacific, and Europe exhibited a raised trend in comparison to confirmed cases in the Americas and South-East Asia where the trend showed a fall. Concurrently, a similar trend for the death cases were also observed for all these continents (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

The number of cumulative total confirmed cases and death cases, also, the number of cumulative total confirmed cases and death cases per 100,000 population, until July 23, 2021.

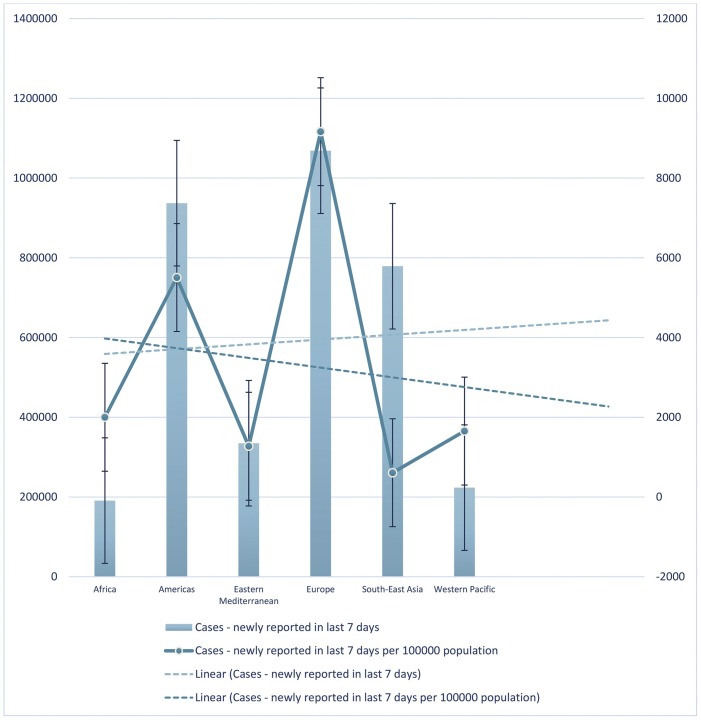

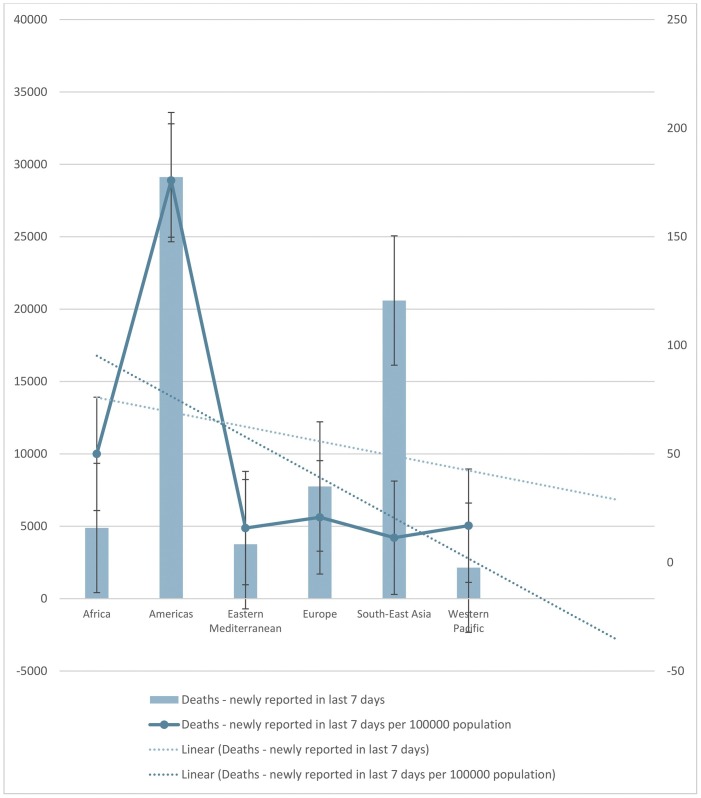

The trend lines in Fig. 3 shows that until July 23, 2021, the number of newly cumulative total cases and cumulative total cases per 100000 population in the last seven days increased and decreased, respectively. In this period, Europe had the highest and South-East Asia had the lowest number of newly cumulative total cases and cumulative total cases per 100000 population in the last seven days.

Fig. 3.

The number of newly cumulative total cases and cumulative total cases per 100,000 population in the last seven days until July 23, 2021.

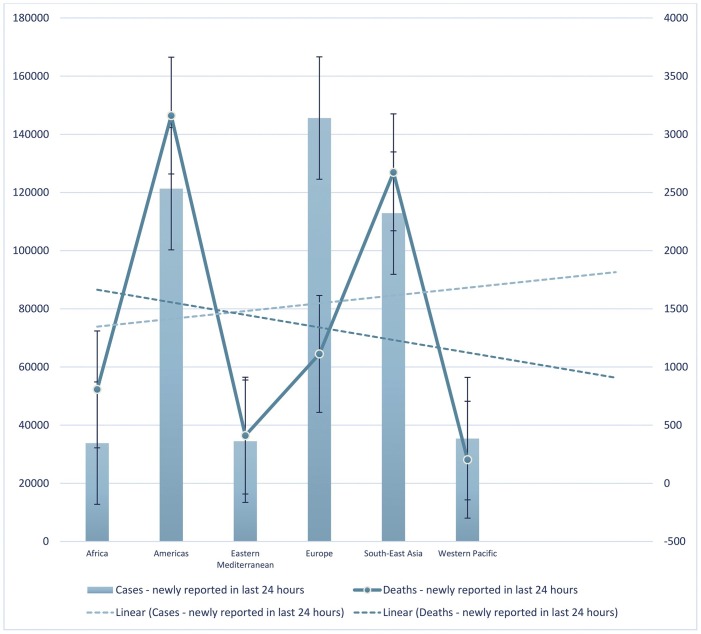

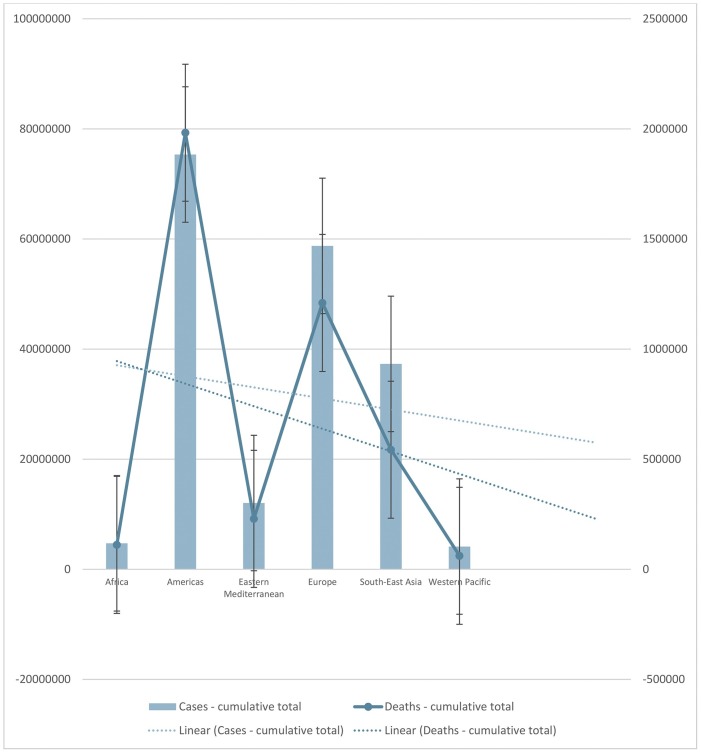

The trend line in Fig. 4 shows that until July 23, 2021, the number of newly reported cases in the last 24 h increased, and the number of newly reported deaths in the last 24 h decreased. Europe had the highest number of newly reported cases in the last 24 h while the Americas had the highest number of newly reported deaths in the last 24 h. Africa had the lowest number of newly reported cases, while the Western Pacific had the lowest number of newly reported deaths in the last 24 h. The trend line in Fig. 5 shows that until July 23, 2021, the number of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100,000 population decreased. Americas had the highest number of newly cumulative total deaths, Europe had the highest cumulative total deaths per 100,000 population. The Western Pacific had the lowest number of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100,000 population. The trend line shows that until July 23, 2021, the number of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100,000 population decreased in the last seven days. Americas had the higher number of newly cumulative total deaths and the highest cumulative total death per 100,000 population in the last seven days. Until July 23, 2021, Western Pacific had the lowest number of newly cumulative total deaths, but Eastern Mediterranean had the lowest cumulative total deaths per 100,000 population in the last seven days (Fig. 6 ). Furthermore, the trend line shows that until July 23, 2021, the number of newly cumulative total confirmed and deaths cases decreased. Although Americas had the higher number of newly cumulative total confirmed and death cases, Western Pacific had the lowest number of newly cumulative total confirmed and death cases until July 23, 2021 (Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 4.

Depicts the number of newly reported cases and deaths in the last 24 hours until July 23, 2021. The trend lines showed an increase and decrease of the newly reported cases and deaths, respectively in the last 24 hours.

Fig. 5.

The number of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100000 population until July 23, 2021. The trend lines showed a decrease of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100000 population.

Fig. 6.

The number of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100,000 population in the last seven days until July 23, 2021. The trend line shows that the number of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100,000 population decreased in the last seven days. The number of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100000 population in the last seven days until July 23, 2021. The trend lines showed a decrease of newly cumulative total deaths and cumulative total deaths per 100000 population in the last seven days.

Fig. 7.

The number of newly cumulative total confirmed and deaths cases until July 23, 2021. The trend lines showed a decrease of newly cumulative total confirmed and deaths cases.

Immunology of COVID-19

Most infected people (more than 80%) will develop mild to moderate illness without symptoms and recover without hospitalization, but less than 20% of infected patients have severe symptoms and are critically ill [20,21]. Presently, there is incomplete evidence on host factors affecting individual outcomes in COVID-19. Fever, dry cough, and tiredness are the most common symptoms; less common symptoms include aches and pains, sore throat, diarrhea, conjunctivitis, headache, loss of taste or smell, skin rash, and discoloration fingers or toes [22,23].

The first line of immunological defense against COVID-19, as with SARS-CoV-2 infection, is the innate immune system. The development of COVID-19 infection is thought to occur from a complex interplay between multiple pathophysiological mechanisms as with SARS-CoV-2, where the mechanisms regulate SARS-CoV-2 infection and contribute to specific tissue damage in organs [24]. There are various immunity pathways mediated during SARS-CoV-2 infection, which are related to innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and autoimmunity. Pathological findings in tissue samples of patients with COVID-19 provide valuable information about our understanding of pathophysiology and the development of evidence-based treatment regimens [25].

Infection mechanisms and immune evasion

To find the escape mechanism of COVID-19 from the host’s immune response, one may extrapolate knowledge of SARS-CoV counterparts and MERS-CoV. Remarkably, COVID-19 has almost 80% RNA sequence homology in common with SARS-CoV, and 50% with MERS-CoV [17], with COVID-19 demonstrating different genomic regions compared to SARS-CoV. The viral spike protein bonded to the host cell receptor is longer than other related coronaviruses, particularly SARS-CoV with about 30 amino acids [26]. Thus, similar immune evasion strategies may be used by all coronaviruses. Nevertheless, undiscovered mechanisms may also be employed by COVID-19 [27]. Both SARS-CoV and COVID-19 use the host cell receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), to start the infection [28]. The ACE2 is found on surfactant generating type 2 alveolar cells and on related cells in the airways, which serves as an entry for viruses into the body [[29], [30], [31]]. High ACE2 expression is also observed on the intestinal epithelium [32].

Expression of ACE2

The expression of ACE2 on cardiac and vascular endothelial cells may elucidate cardiovascular complications in patients [16]. It is not evident whether and how the SARS-CoV-2 can also infect immune cells containing monocytes/macrophages and T cells. On monocytes and macrophages, the expression of ACE2 is not ubiquitously observed, and for SARS-CoV-2 this may offer a mechanism of entry into immune cells. Immune complexes, including other receptors and/or phagocytosis of the virus, are also apparent [[33], [34], [35]]. The expression of type I interferon (T1IFN) and signals of downstream modification responses into an ‘anti-viral state’, consequently encourages infection control and pathogen clearance [36]. Initially, immune cells find a virus-related infection from pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are then activated and cause the activation of the immune cell. SARS-CoV, COVID-19, and MERS-CoV are among the RNAs viruses, which the endosomal RNA PRRs distinguish, including toll-like receptors 3 (TLR-3) and sensors of cytoplasmic RNA, namely retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) [[37], [38], [39]].

Pathogen clearance and recovery have emerged due to activation and priming of innate and adaptive immune responses. The suppression of these mechanisms by COVID-19 in some cases to escape recognition by the immune system is seen in more severe infections and worse prognosis [[40], [41], [42], [43]].

To some extent, the novel coronaviruses may also discharge these mechanisms inducing T cell apoptosis [44,45]. Lymphocytes may also become exhausted due to pro-inflammatory cytokine expression by native immune cells engaged in the lungs and trigger hyper-inflammation during a cytokine storm [46,47].

Hyper inflammation

In some cohort studies, the key results were associated with negative consequences in COVID-19, as in SARS or MERS, as hyper-inflammation with more severe disease was suggested. Among 99 patients infected by COVID-19, the report showed the typical symptoms with percentages of 38, 35, and 52 related to neutrophilia, lymphopenia, and increased systemic inflammatory proteins of IL-6 CRP, respectively [48]. A study involving 41 individuals with severe disease terminating in an intensive care unit (ICU) admission or death presented with interconnected neutrophilia and lymphopenia [20]. In another study, substantial leukopenia (11.8%), lymphopenia (77.6%), thrombopenia (41.2%), anemia (48.2%), hypofibrinogenemia (22.4%), and hypo-albuminemia (78.8%) was reported among 85 cases of death from COVID-19 [49]. These observations agree with the results of severe conditions of MERS or lethal cases of SARS in which the presence of neutrophils and macrophages were increased in the airways [49,50]. Other studies of severe clinical phenotypes and ICU dependency of patients have presented a link with higher levels of plasma from innate chemokines, definitely the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10), and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP-)1 A/CCL3 [51,52]. This is a condition previously described in SARS and MERS inflammation with poor consequences.

Enhanced activation of the innate immune system contributes to morbidity and mortality in COVID-19, contradictory to immune evasion mechanisms, including expression activation of T1IFN, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. One probable description is that the endothelial induction, vascular cell damage, and cell death have resulted from replicating the COVID-19 virus. Cell deaths are due to inflammation, including necrosis or pyroptosis in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, recruitment, and activation of immune cells [53]. It is proposed that uninfected immune cells recruited to the infection site show inflammatory responses of unwell and robust control, leading to damage of tissues and systemic inflammation [54].

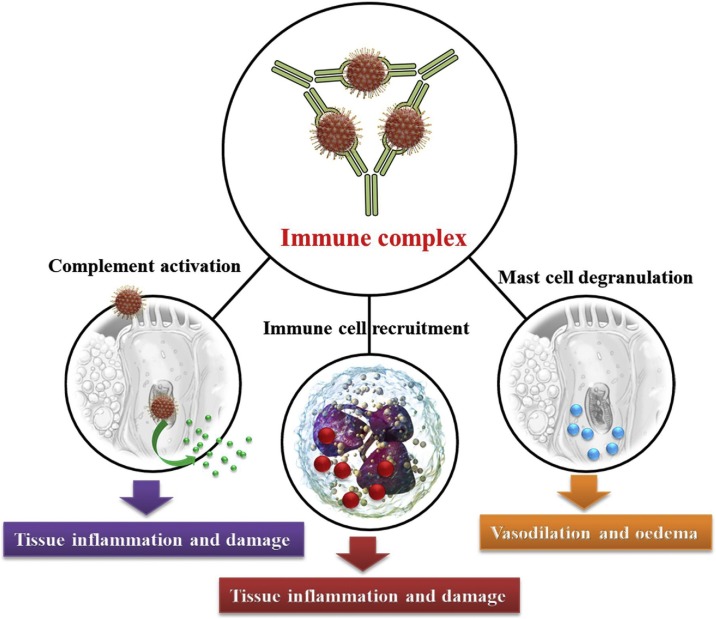

The other probable explanation relates to the production of neutralizing antibodies against coronaviruses in the early stages of damaged organs. The phenomenon of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) increases damage throughout viral infections. It should be noted that the promotion of virus particle uptake is connected to immune system complexes in binding to Fcγ receptors (FcγR). Viral replication in immune cells and immune complexes are both mediated inflammatory responses in the damaged tissues of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Fig. 8 ) [46,55]. The histopathologic reports of tissues from COVID-19 patients showed the advanced features associated with immune complex-mediated vasculitis, including monocyte infiltration, thickening of blood vessels, and hemorrhage [[56], [57], [58]].

Fig. 8.

A schematic illustration of inflammatory mechanisms in complex immune vasculitis.

Generally, patients with severe symptoms of COVID-19 experience cytokine storm, lymphopenia, and often lymphatic tissue atrophy, specifically lymph nodes [59,60]. This cytokine storm corresponds to the reports of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), inspiring cell death and hypo-cellularity of lymphatic organs [[61], [62], [63]].

Effective host factors

The available data associated with age is insufficient, but children seemingly do not progress to severe indicators or difficulties associated with COVID-19. This is surprising as children are prone to viral infections comprising seasonal coronaviruses (75%) before four years. Nonetheless, increasing age leads to antibody decrease, especially over sixty years [64]. It can diminish the effective response of immune systems to COVID-19 in the elderly, as the reactivity is restricted to anti-seasonal coronavirus and anti-SARS antibodies with increased inflammation and complications.

The other age-dependent mechanism may be allied with live vaccinations (e.g., BCG). Vaccines protect the target antigen, which leads to non-specific heterologous effects due to the induction of innate immune mechanisms—individuals who receive BCG vaccinations as infants in response to S. aureus or Candida spp. produce increased pro-inflammatory IL-1β and TNF-α levels and reduced infection-related mortality [38].

Conversely, immune responses in a non-homogenous manner may also contribute to inflammation complications. Normally in adults, T cells do not have a memory of antigens they have not been exposed to, but cross-reactive memory T cells lead to slender responses by preferring clones with high affinity. The feature of immune senescence is due to the limited memory T cell repertoires, associated with disease progression and damage of T cell-mediated infections of hepatitis and virulent mononucleosis [65,66]. Lately it has been recommended that in children and young women, a higher expression of ACE2 is expected, which decreases with age. In contrast, the lowest expression is seen in chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, in reverse correlation with risk for severe disease and negative effects [66].

Immune modulating treatment

According to earlier SARS, MERS studies, and COVID-19 cohort studies, the determinants of old age, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obesity, male, coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and kidney disease are among the most reported risk factors [67]. It is noteworthy that in China and Italy, the suppression of the immune system was not acknowledged among these risk factors [68]. However, immune suppression and its associated functions may enhance virus spread.

Moreover, the infected cases receiving immune-modulating treatment may be prone to secondary infections due to the association of COVID-19 with lymphopenia. Some immune-modulating drugs can defend against viral infections. Unrestrained treatment termination of immune-modulating drugs may cause disease flares in autoimmune/inflammatory conditions or organ rejection. As evident, the risk for a viral infection is increased. Thus, international communities recommend treatment continuation in the absence of symptoms and modifications of current treatment regimens with clinical service monitoring [68,69].

Conclusion

The outbreak of COVID-19 has caused concern around the world, and it is not evident whether and how SARS-CoV-2 can also infect immune cells. Different studies reported neutrophilia, lymphopenia, leukopenia, thrombopenia, anemia, hypofibrinogenemia, hypo-albuminemia, and increased systemic inflammatory proteins of IL-6 CRP. In severe conditions of MERS or lethal cases of SARS, neutrophils and macrophages are increased in the airways. The analysis of available data can help authorities in deciding how to control the virus worldwide. Thus, this study collected and analyzed data from articles and databases. Various researchers in different parts of the world analyze the available data to predict the prevalence of coronavirus in different countries; still, no analysis has been published that can predict the situation and future peaks. Following the review and analyzing of the published data on the WHO website and the data generated from the reported cases and trend lines, this study predicts that the number of confirmed cases (cumulative total) and deaths (cumulative total) caused due to coronavirus in different continents would decrease eventually. Intriguingly, although, the trend lines indicating that the number of confirmed cases (newly reported in the last 24 hours and last seven days) would increase, the number of deaths cases (newly reported in the last 24 hours and last seven days) will decrease in the long run. In the future, additional analyses based on the updated data and information are essential to confirm the prediction of this study.

Funding

The current study does not received any funding.

Declaration of conflicting interests

There was no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to the Pasteur Institute of Iran for providing research conditions.

References

- 1.Jiang S., Shi Z., Shu Y., Song J., Gao G.F., Tan W., et al. A distinct name is needed for the new coronavirus. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10228):949. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30419-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheikhpour M. The current recommended drugs and strategies for the treatment of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:933. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S262936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) Global research and innovation forumAccess date: July 23, 2021, URL: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum.

- 5.Saif L.J. Coronaviruses of domestic livestock and poultry: interspecies transmission, pathogenesis, and immunity. Nidoviruses. 2007:279–298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drexler J.F., Gloza-Rausch F., Glende J., Corman V.M., Muth D., Goettsche M., et al. Genomic characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus in European bats and classification of coronaviruses based on partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences. J Virol. 2010;84(21):11336–11349. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00650-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saif L.J. 2007. Coronaviruses of domestic livestock and poultry: interspecies transmission, pathogenesis, and immunity; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drexler J.F., Drexler J.F., Gloza-Rausch F., Glende J., Corman V.M., Muth D., Goettsche M., et al. Genomic characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus in European bats and classification of coronaviruses based on partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences. J Virol. 2010;84(21):11336–11349. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00650-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afelt A., Lacroix A., Zawadzka-Pawlewska U., Pokojski W., Buchy P., Frutos R. Distribution of bat-borne viruses and environment patterns. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;58:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohan S.V., Hemalatha M., Kopperi H., Ranjith I., Kumar A.K. SARS-CoV-2 in environmental perspective: occurrence, persistence, surveillance, inactivation and challenges. Chem Eng J. 2021;405:126893. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fong S.J., Dey N., Chaki J. Springer; 2020. Artificial intelligence for coronavirus outbreak. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siordia J.A., Jr Epidemiology and clinical features of COVID-19: a review of current literature. J Clin Virol. 2020:104357. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakshmi Priyadarsini S., Suresh M. Factors influencing the epidemiological characteristics of pandemic COVID 19: a TISM approach. Int J Healthc Manag. 2020;13(2):89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halaji M., Farahani A., Ranjbar R., Heiat M., Dehkordi F.S. Emerging coronaviruses: first SARS, second MERS and third SARS-CoV-2: epidemiological updates of COVID-19. Infez Med. 2020;28(suppl 1):6–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surveillances V. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—china, 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2(8):113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen L., Li X., Chen M., Feng Y., Xiong C. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(6):1097–1100. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binnicker M.J. Emergence of a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the importance of diagnostic testing: why partnership between clinical laboratories, public health agencies, and industry is essential to control the outbreak. Clin Chem. 2020;66(5):664–666. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y., Xu J., Li H., Cao B. A novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a call for action. Chest. 2020;157(4):e99–e101. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J., Xie W., Wang Y., Xiong Y., Chen S., Han J., et al. A comparative overview of COVID-19, MERS and SARS. Int J Surg. 2020;81:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kronbichler A., Effenberger M., Eisenhut M., Lee K.H., Shin J.I. Seven recommendations to rescue the patients and reduce the mortality from COVID-19 infection: an immunological point of view. Autoimmun Rev. 2020:102570. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadbeigi M., Koshkohi S.A., Meskini M. An overview on wearing the face mask to avoid transmission of coronavirus disease 2019. Rev Med Microbiol. 2020;31(4):221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammadi M., Meskini M., do Nascimento Pinto A.L. 2019 Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) overview. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01258-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Eijk L.E., Binkhorst M., Bourgonje A.R., Offringa A.K., Mulder D.J., Bos E.M., et al. COVID‐19: immunopathology, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment options. J Pathol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/path.5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paland N., Pechkovsky A., Aswad M., Hamza H., Popov T., Shahar E., et al. The immunopathology of COVID-19 and the Cannabis paradigm. Front Immunol. 2021;12:327. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.631233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wan Y., Shang J., Graham R., Baric R.S., Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou H., Chen X., Hu T., Li J., Song H., Liu Y., et al. A novel bat coronavirus closely related to SARS-CoV-2 contains natural insertions at the S1/S2 cleavage site of the spike protein. Curr Biol. 2020;30(11):2196–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu Y., Li J., Pang Z. Recent insights for the emerging COVID-19: drug discovery, therapeutic options and vaccine development, Asian. J Pharm Sci. 2021;16(1):4–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verdecchia P., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakkundi N.V. Surfactant therapy and SP-D in managing COVID-19 ARDS–therapeutic role possible. J PeerScientist. 2020;3(2):e1000029. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verdecchia P., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Internal Med. 2020;76:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegler C.G., Allon S.J., Nyquist S.K., Mbano I.M., Miao V.N., Tzouanas C.N., et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020;181(5):1016–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035. e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AbdelMassih A.F., Ramzy D., Nathan L., Aziz S., Ashraf M., Youssef N.H., et al. Possible molecular and paracrine involvement underlying the pathogenesis of COVID-19 cardiovascular complications. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab. 2020;9(3):121. doi: 10.1097/XCE.0000000000000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu H., Cheng P., Waliany S., Chang A., Witteles R.M., et al. Cardiovascular complications in patients with COVID-19: consequences of viral toxicities and host immune response. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22(5):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01292-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo J., Wei X., Li Q., Li L., Yang Z., Shi Y., et al. Single‐cell RNA analysis on ACE2 expression provides insights into SARS‐CoV‐2 potential entry into the bloodstream and heart injury. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(12):9884–9894. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosking M.P., Flynn C.T., Whitton J.L. Type I IFN signaling is dispensable during secondary viral infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(8):e1005861. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedrich C.M. COVID-19–considerations for the paediatric rheumatologist. Clin Immunol. 2020:108420. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Felsenstein S., Hedrich C.M. SARS-CoV-2 infections in children and young people. Clin Immunol. 2020:108588. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eswaran N., Krishna S. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): pathogenesis, immune responses, and treatment options. Asian J Res Infect Dis. 2020:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thevarajan I., Nguyen T.H., Koutsakos M., Druce J., Caly L., van de Sandt C.E., et al. Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case report of non-severe COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):453–455. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazzoni A., Salvati L., Maggi L., Capone M., Vanni A., Spinicci M., et al. Impaired immune cell cytotoxicity in severe COVID-19 is IL-6 dependent. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(9) doi: 10.1172/JCI138554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melenotte C., Silvin A., Goubet A.-G., Lahmar I., Dubuisson A., Zumla A., et al. Immune responses during COVID-19 infection. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1807836. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1807836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwasaki A., Yang Y. The potential danger of suboptimal antibody responses in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):339–341. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0321-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wyllie A.H. Apoptosis: an overview. Br Med Bull. 1997;53(3):451–465. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aghagoli G., Marin B.G., Katchur N.J., Chaves-Sell F., Asaad W.F., Murphy S.A. Neurological involvement in COVID-19 and potential mechanisms: a review. Neurocrit Care. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-01049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asrani P., Hassan M.I. SARS-CoV-2 mediated lung inflammatory responses in host: targeting the cytokine storm for therapeutic interventions. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476(2):675–687. doi: 10.1007/s11010-020-03935-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang L., Yin Z., Hu Y., Mei H. Controlling cytokine storm is vital in COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:3158. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.570993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ponti G., Maccaferri M., Ruini C., Tomasi A., Ozben T. Biomarkers associated with COVID-19 disease progression. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2020;57(6):389–399. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2020.1770685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du Y., Tu L., Zhu P., Mu M., Wang R., Yang P., et al. Clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan. A retrospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1372–1379. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dandekar A.A., Perlman S. Immunopathogenesis of coronavirus infections: implications for SARS. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(12):917–927. doi: 10.1038/nri1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelsven S., de la Fuente-Sandoval C., Achim C.L., Reyes-Madrigal F., Mirzakhanian H., Domingues I., et al. Immuno-inflammatory changes across phases of early psychosis: the impact of antipsychotic medication and stage of illness. Schizophr Res. 2020;226:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawamoto D., Amado P.P.L., Albuquerque-Souza E., Bueno M.R., Vale G.C., Saraiva L., et al. Chemokines and cytokines profile in whole saliva of patients with periodontitis. Cytokine. 2020;135:155197. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X., Cao R., Zhang H., Liu J., Xu M., Hu H., et al. The anti-influenza virus drug, arbidol is an efficient inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6(1):1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0169-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez F.O., Combes T.W., Orsenigo F., Gordon S. Monocyte activation in systemic Covid-19 infection: assay and rationale. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102964. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Can A., Coskun H. The rationale of using mesenchymal stem cells in patients with COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome: what to expect. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2020;9(11):1287–1302. doi: 10.1002/sctm.20-0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Becker R.C. Springer; 2020. COVID-19-associated vasculitis and vasculopathy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Almashat S.A. Vasculitis in COVID-19: a literature review. J Vasc. 2020;6(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prasad A. Looking beyond the cutaneous manifestations of covid 19, part 2: the pathology and Pathogenesis—a review. Asian J Res Dermatol Sci. 2020:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soy M., Keser G., Atagündüz P., Tabak F., Atagündüz I., Kayhan S. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: pathogenesis and overview of anti-inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2085–2094. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang Y., Liu J., Zhang D., Xu Z., Ji J., Wen C. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: the current evidence and treatment strategies. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1708. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soy M., Atagündüz P., Atagündüz I., Sucak G.T. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a review inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04636-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henderson L.A., Canna S.W., Schulert G.S., Volpi S., Lee P.Y., Kernan K.F., et al. On the alert for cytokine storm: immunopathology in COVID‐19. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(7):1059–1063. doi: 10.1002/art.41285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wei A., Ma H., Zhang L., Li Z., Zhang Q., Wang D., et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis resulting from a cytokine storm triggered by septicemia in a child with chronic granuloma disease: a case report and literature review. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-1996-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Age-related susceptibility to coronavirus infections: role of impaired and dysregulated host immunity. J Clin Invest. 2020 doi: 10.1172/JCI144115. Oct 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shaw E.R., Su H.C. The influence of immune immaturity on outcome after virus infections. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(2):641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Varadé J., Magadán S., González-Fernández Á. Human immunology and immunotherapy: main achievements and challenges. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020:1–24. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00530-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lai C.-C., Liu Y.H., Wang C.-Y., Wang Y.-H., Hsueh S.-C., Yen M.-Y., et al. Asymptomatic carrier state, acute respiratory disease, and pneumonia due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): facts and myths. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53(3):404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.D’Antiga L. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients: the facts during the third epidemic. Liver Transplant. 2020;26(6):832–834. doi: 10.1002/lt.25756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Borba M.G.S., Val F.F.A., Sampaio V.S., Alexandre M.A.A., Melo G.C., Brito M., et al. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e208857. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghosh S., Bornman C., Zafer M.M. Antimicrobial Resistance Threats in the emerging COVID-19 pandemic: Where do we stand? J Infect Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alhouri A., Salloum A., Harfouch R.M., Ghosh S. Antimicrobial Resistance Threats in the emerging COVID-19 pandemic: Where do we stand? J Infect Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]