Abstract

Background

The interaction between COVID-19, non-communicable diseases, and chronic infectious diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis is unclear, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries in Africa. South Africa has a national HIV prevalence of 19% among people aged 15–49 years and a tuberculosis prevalence of 0·7% in people of all ages. Using a nationally representative hospital surveillance system in South Africa, we aimed to investigate the factors associated with in-hospital mortality among patients with COVID-19.

Methods

In this cohort study, we used data submitted to DATCOV, a national active hospital surveillance system for COVID-19 hospital admissions, for patients admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection between March 5, 2020, and March 27, 2021. Age, sex, race or ethnicity, and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, chronic cardiac disease, chronic pulmonary disease and asthma, chronic renal disease, malignancy in the past 5 years, HIV, and past and current tuberculosis) were considered as risk factors for COVID-19-related in-hospital mortality. COVID-19 in-hospital mortality, the main outcome, was defined as a death related to COVID-19 that occurred during the hospital stay and excluded deaths that occurred because of other causes or after discharge from hospital; therefore, only patients with a known in-hospital outcome (died or discharged alive) were included. Chained equation multiple imputation was used to account for missing data and random-effects multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess the role of HIV status and underlying comorbidities on COVID-19 in-hospital mortality.

Findings

Among the 219 265 individuals admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and known in-hospital outcome data, 51 037 (23·3%) died. Most commonly observed comorbidities among individuals with available data were hypertension in 61 098 (37·4%) of 163 350, diabetes in 43 885 (27·4%) of 159 932, and HIV in 13 793 (9·1%) of 151 779. Tuberculosis was reported in 5282 (3·6%) of 146 381 individuals. Increasing age was the strongest predictor of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. Other factors associated were HIV infection (adjusted odds ratio 1·34, 95% CI 1·27–1·43), past tuberculosis (1·26, 1·15–1·38), current tuberculosis (1·42, 1·22–1·64), and both past and current tuberculosis (1·48, 1·32–1·67) compared with never tuberculosis, as well as other described risk factors for COVID-19, such as male sex; non-White race; underlying hypertension, diabetes, chronic cardiac disease, chronic renal disease, and malignancy in the past 5 years; and treatment in the public health sector. After adjusting for other factors, people with HIV not on antiretroviral therapy (ART; adjusted odds ratio 1·45, 95% CI 1·22–1·72) were more likely to die in hospital than were people with HIV on ART. Among people with HIV, the prevalence of other comorbidities was 29·2% compared with 30·8% among HIV-uninfected individuals. Increasing number of comorbidities was associated with increased COVID-19 in-hospital mortality risk in both people with HIV and HIV-uninfected individuals.

Interpretation

Individuals identified as being at high risk of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality (older individuals and those with chronic comorbidities and people with HIV, particularly those not on ART) would benefit from COVID-19 prevention programmes such as vaccine prioritisation as well as early referral and treatment.

Funding

South African National Government.

Introduction

The first case of COVID-19 in South Africa was documented on March 5, 2020. By March 27, 2021, 1 545 431 cases had been reported and the cumulative incidence was 2592·0 cases per 100 000 people.1 Meta-analyses have reported in-hospital mortality rates between 15% and 24%, with substantial global and temporal heterogeneity.2, 3, 4 Worldwide, studies have linked COVID-19-related mortality to older age, male sex, and underlying medical conditions, including cardiac disease, diabetes, cancer, chronic pulmonary disease, obesity, and kidney disease.2, 3, 5, 6 Race or ethnicity and poverty were associated with increased risk of death in COVID-19 cases in large population cohorts and meta-analyses.7, 8, 9

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for research articles published between Dec 1, 2019, and May 5, 2021, without language restrictions, using three sets of search terms: “COVID-19”, “risk factors”, and “mortality”; “HIV”, “COVID-19”, and “mortality”; and “TB”, “COVID-19”, and “mortality”. Pooled together, we identified 2786 published papers. Additionally, we searched medRxiv for research articles published between April 25, 2020, and May 5, 2021, without language restrictions, using two sets of search terms: “HIV”, “COVID-19”, and “mortality”; and “TB”, “COVID-19”, and “mortality”. Pooled together, we identified 7744 preprints. Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, studies have identified older age, male sex, and presence of underlying comorbidities, including heart disease and diabetes, as risk factors for severe disease and death. Very few studies, however, have been carried out in low-income and middle-income countries in Africa, many of which have high poverty rates, insufficient access to health care, and high prevalence of chronic communicable diseases, such as HIV and tuberculosis. Data are also scarce from settings with limited access to HIV treatment programmes. Early small cohort studies, mainly from high-income countries, were not conclusive on whether HIV or tuberculosis are risk factors for disease severity and death in patients with COVID-19. Large population cohort studies from South Africa's Western Cape province and the UK have found people living with HIV to have a moderately increased risk of COVID-19-associated mortality. Of these studies, only the Western Cape study presented data on mortality risk associated with presence of high viral load or immunosuppression, and found similar levels of severity irrespective of these factors. Recent meta-analyses have confirmed the association of HIV with COVID-19 mortality. No studies reported on the interaction between HIV infection and non-communicable comorbidities on COVID-19-associated mortality

Added value of this study

Among a large national cohort of almost 220 000 individuals admitted to hospital with COVID-19 in a setting with 19% HIV prevalence among people aged 15–49 years and 0·7% tuberculosis prevalence, we found that along with age, sex, and non-communicable comorbidities, HIV and tuberculosis were associated with a moderately increased risk of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. We found increasing risk of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality among people with HIV not on antiretroviral therapy compared with those on antiretroviral therapy. Among people with HIV, the prevalence of non-communicable comorbidities was high (29·2%) and the effect of increasing numbers of comorbidities on COVID-19 in-hospital mortality was similar in people with HIV and HIV-uninfected individuals. Our study included 13 793 people with HIV from all provinces in the country with varying levels of access to HIV treatment programmes.

Implications of all the available evidence

The evidence suggests that people with HIV and patients with tuberculosis should be prioritised for COVID-19 prevention and treatment programmes, particularly those with additional comorbidities. Increasing age and presence of chronic underlying illness are important additional factors associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in a middle-income African setting. The completeness of data is a limitation of this national surveillance system, and additional data are needed to confirm these findings.

Characterisation of populations at increased risk of COVID-19 mortality is important for prioritisation of interventions, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries, where resources are limited. However, available data on risk factors for severe COVID-19, including mortality, are mostly from high-income countries. High poverty rates, insufficient access to health care, and high prevalence of chronic communicable diseases, such as HIV and tuberculosis, probably affect the burden of COVID-19 and disease severity in low-income and middle-income countries.10

South Africa is a middle-income country with coinciding epidemics of non-communicable diseases and chronic infectious diseases (HIV and tuberculosis). In 2020, the prevalence of HIV among people aged 15–49 years was 19%,11 and tuberculosis prevalence was 0·7% for all ages.12 In 2019, 7·5 million people were estimated to be living with HIV in South Africa, of whom 2·3 million (31%) were eligible for, but not receiving, treatment.13

An understanding of whether HIV and tuberculosis are associated with mortality among patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 is of huge importance for South Africa, and other countries in the region with large HIV and tuberculosis epidemics, to guide public health action around prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Early single-centre cohort studies14, 15 and meta-analyses16, 17 from high-income countries with relatively small numbers of people living with HIV did not find HIV to be a risk factor for severe COVID-19. Larger population cohorts18, 19, 20 and more recent meta-analyses21, 22, 23 found people with HIV to have an increased population risk of COVID-19-associated mortality. The interaction between non-communicable comorbidities, HIV infection, and COVID-19 in-hospital mortality is not well described.

We aimed to examine the association between HIV infection, tuberculosis, non-communicable comorbidities, and in-hospital mortality among patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection using data from a national surveillance programme in South Africa.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This cohort study was done in South Africa, which is administratively divided into nine provinces. South Africa has a dual health system, with a publicly funded district health system that serves approximately 84% of the population and a private health system largely funded by private health insurance schemes.24

In the absence of existing national COVID-19 hospital surveillance systems, the National Institute for Communicable Diseases established DATCOV as a national surveillance system for COVID-19 hospital admissions on April 1, 2020.25 DATCOV was adopted for national implementation by the South African Government on July 15, 2020, and by October, 2020, full coverage of all hospitals had been achieved. By March 27, 2021, 393 public-sector hospitals and 251 private-sector hospitals had reported COVID-19 admissions on DATCOV. Further details about the DATCOV surveillance system, including its implementation, data management, and data quality assurance, are described in the appendix (p 1).

The Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) at the University of the Witwatersrand (Johannesburg, South Africa) approved the project protocol as part of a national surveillance programme (M160667). In South Africa, surveillance for notifiable medical conditions such as COVID-19 requires health facilities to submit data on all cases of emerging pathogens to national authorities. As such, individual consent for inclusion of their data to DATCOV is waivered. All personal identifying information was delinked for our analysis and stored in a secure server.

Potential risk factors and covariates

Age, sex, race or ethnicity, and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, chronic cardiac disease, chronic pulmonary disease and asthma, chronic renal disease, malignancy in the past 5 years, obesity, HIV, and past and current tuberculosis) were considered as potential risk factors for COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. Data on comorbidities (including HIV status, antiretroviral therapy (ART) status, and CD4 cell count and viral load in the past 12 months), obtained from patients' written and electronic hospital records, were submitted to DATCOV by the hospitals. The DATCOV team did not independently verify these data or access laboratory records to obtain these data. The date of the most recent CD4 cell count or viral load was not documented. The level of virological control or immunosuppression was assessed based on last available viral load or CD4 cell count result within the past year and categorised as virologically suppressed (HIV RNA <1000 copies per mL) or viraemic (HIV RNA ≥1000 copies per mL), and immune reconstituted (CD4 count ≥200 cells per μL) or immunosuppressed (CD4 count <200 cells per μL).26 CD4 cell count is no longer routinely measured in all patients, in accordance with South African HIV care guidelines.27

COVID-19 in-hospital mortality was defined as a death related to COVID-19 that occurred during the hospital stay and excluded deaths that occurred because of other causes or after discharge from hospital. Because the main outcome of the study was COVID-19 in-hospital mortality, all analyses included patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who had a known in-hospital outcome (ie, discharged alive or died) at the time of data extraction (March 27, 2021).

Statistical analysis

We analysed DATCOV data from patients admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection between March 5, 2020, and March 27, 2021. For the main analysis, to account for incomplete or missing data on selected variables, we used multivariate imputation by chained equation (MICE) and generated ten complete imputed datasets that were used for subsequent analyses. Variables analysed by use of MICE included sex, race or ethnicity, month of admission, and the following comorbidities: HIV infection, tuberculosis infection, hypertension, diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease and asthma, malignancy in the past 5 years, chronic cardiac disease, and chronic renal disease. ART status, HIV viral load, and CD4 cell counts were also incomplete and were conditionally imputed only among HIV-positive patients (either with observed or imputed HIV status). Complete variables included in the imputation process were age, province, health sector (ie, public or private), and in-hospital outcome (ie, discharged alive or died). Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables, and continuous variables were expressed as mean with SD or median and IQR on the imputed datasets.

We implemented three post-imputation random-effect (on admission facility) multivariable logistic regression models: first, to compare people with HIV and individuals who were HIV-uninfected; second, to determine the factors associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality, including ART status, HIV viral load, and CD4 cell count among HIV-positive individuals; and, third, to evaluate the combined effect of multiple non-HIV comorbidities on COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. A combined comorbidity variable categorised none, one, two, and three or more comorbidities among factors that were individually significantly associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in the third model. We evaluated the effect of multiple comorbidities among all patients and among people with HIV and HIV-uninfected patients separately through stratification by HIV infection status. In addition, we assessed the potential differential effect (through the inclusion of an interaction term) of multiple or individual comorbidities on COVID-19 in-hospital mortality between people with HIV and HIV-uninfected individuals.

A random effect on admission facility was included for all analyses to account for potential differences in the service population and the quality of care at each facility. For each multivariable model, we assessed all variables that were significant at p values of less than 0·2 in the univariate analysis (to evaluate lack of significance in the univariate analysis after adjusting for potential confounders) and excluded non-significant factors (p≥0·05) with manual backward elimination. Pairwise interactions were assessed by inclusion of product terms for all variables remaining in the final multivariable additive model. We implemented several sensitivity analyses separately, analysing risk factors for COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in the public and private sectors using post-imputation random-effect multivariable logistic regression models. We also reported the univariate and multivariate association of all covariates evaluated in the analyses described previously with HIV infection and COVID-19 in-hospital mortality using non-imputed data. The statistical analysis was implemented using Stata (version 15). We followed STROBE guideline recommendations.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

From March 5, 2020, to March 27, 2021, 229 154 individuals were admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and reported to DATCOV. Of these patients, 219 265 had a known in-hospital outcome and were included in analyses (appendix p 5). The percentage of missing data for the imputed variables varied and was highest for obesity (163 570 [74·6%]), race or ethnicity (73 389 [33·5%]), and for HIV-specific variables including HIV diagnosis (67 486 [30·8%]), being on ART (5715 [41·4%] of 13 793 known HIV-positive individuals), viral load (12 077 [87·6%] of 13 793), and CD4 cell count (11 023 [79·9%] of 13 793; appendix pp 6–7). Obesity was excluded from the analysis due to the high proportion of missing data.

South Africa experienced a first wave of SARS-CoV-2 infection, peaking at 10 086 admissions per week in July, 2020, and a second wave peaking at 17 976 admissions per week in January, 2021 (appendix p 8).

The median age of patients admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 54 years (IQR 40–66), and 121 937 (55·7%) of 218 827 patients were female (appendix p 6). Among 145 876 patients with available race information, 114 571 (78·5%) were Black (appendix p 6). The public sector accounted for 113 856 (51·9%) of 219 265 hospital admissions reported to DATCOV (appendix p 7). 176 272 (80·4%) of 219 265 hospital admissions were recorded by hospitals in four provinces (Western Cape, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, and Eastern Cape; appendix p 7).

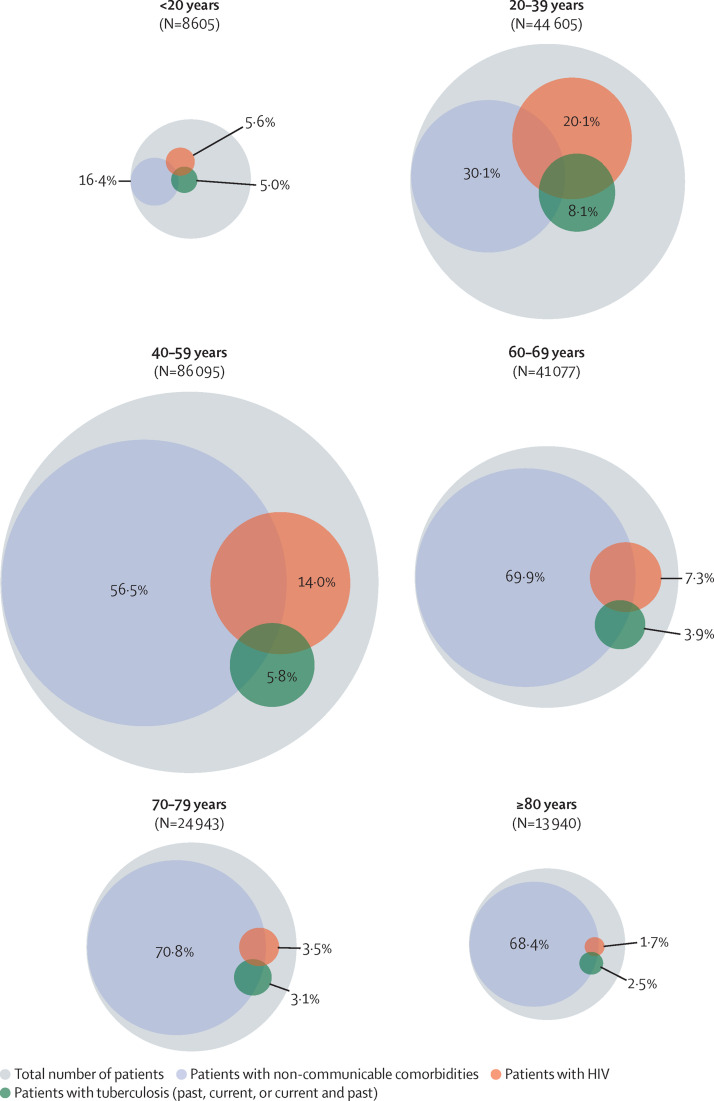

After multiple imputation, the estimated proportion of individuals reporting at least one comorbidity was 60·5% (95% CI 59·8–61·2). The most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (38·6%), diabetes (29·0%), and HIV (11·7%). The prevalence of non-communicable comorbidities increased with age, whereas HIV and tuberculosis were most prevalent in individuals aged 20–59 years (figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Estimated prevalence of comorbid conditions in patients admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection by age

The percentage of patients within each age group is expressed over the total number of patients included in the analysis (n=219 265). Circle size is proportional to the number of patients represented. Inner circles represent a subpopulation (with prevalence expressed as percentage) of the outer circle. Overlapping circles represent co-infections and comorbidities.

Of 151 779 (69·2%) patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 who had available data on HIV, 13 793 (9·1%) were HIV positive (appendix pp 6–7). HIV prevalence was 20·4% in the public sector and 2·2% in the private sector (table 1 ; age-specific HIV prevalence for public and private sector is presented in the appendix p 9). A subset of the 13 793 people with HIV had ART (8078 [58·6%]), viral load (1716 [12·4%]), and CD4 cell count (2770 [20·1%]) information available. 7484 (92·6%) of 8078 patients were receiving ART, and 443 (25·8%) of 1716 were viraemic (HIV RNA ≥1000 copies per mL), and 1080 (39·0%) of 2770 were immunosuppressed (CD4 count <200 cells per μL) based on the last available test.

Table 1.

Characteristics of people with HIV and HIV-uninfected people admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, South Africa (n=219 265)

| People with HIV (n=13 793) | People without HIV (n=137 986) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) unimputed | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) unimputed | p value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) imputed | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) imputed | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 8884/83 607 (10·6%) | 74 723/83 607 (89·4%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Male | 4893/68 090 (7·2%) | 63 197/68 090 (92·8%) | 0·75 (0·72–0·78) | <0·0001 | 0·75 (0·71–0·80) | <0·0001 | 0·78 (0·75–0·80) | <0·0001 | 0·73 (0·70–0·75) | <0·0001 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| <20 | 227/5067 (4·5%) | 4840/5067 (95·5%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| 20–39 | 4616/28 833 (16·0%) | 24 217/28 833 (84·0%) | 5·08 (4·35–5·92) | <0·0001 | 5·60 (4·42–7·09) | <0·0001 | 5·20 (4·32–6·26) | <0·0001 | 5·29 (4·39–6·38) | <0·0001 |

| 40–59 | 6851/62 529 (11·0%) | 55 678/62 529 (89·0%) | 4·03 (3·46–4·70) | <0·0001 | 6·88 (5·43–8·71) | <0·0001 | 4·26 (3·60–5·03) | <0·0001 | 5·42 (4·59–6·40) | <0·0001 |

| 60–69 | 1574/28 957 (5·4%) | 27 383/28 957 (94·6%) | 1·37 (1·17–1·61) | <0·0001 | 2·69 (2·10–3·45) | <0·0001 | 1·53 (1·29–1·81) | <0·0001 | 1·97 (1·65–2·35) | <0·0001 |

| 70–79 | 435/17 487 (2·5%) | 17 052/17 487 (97·5%) | 0·58 (0·48–0·69) | <0·0001 | 0·97 (0·73–1·28) | 0·82 | 0·66 (0·54–0·82) | 0·0005 | 0·80 (0·64–0·99) | 0·040 |

| ≥80 | 90/8906 (1·0%) | 8816/8906 (99·0%) | 0·26 (0·20–0·33) | <0·0001 | 0·41 (0·27–0·61) | <0·0001 | 0·30 (0·22–0·42) | <0·0001 | 0·33 (0·23–0·48) | <0·0001 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White | 55/10 499 (0·5%) | 10 444/10 499 (99·5%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Black | 10 680/68 961 (15·5%) | 58 281/68 961 (84·5%) | 11·37 (8·61–15·02) | <0·0001 | 8·71 (6·19–12·27) | <0·0001 | 13·07 (9·96–17·17) | <0·0001 | 8·87 (6·80–11·58) | <0·0001 |

| Mixed | 210/5917 (3·5%) | 5707/5917 (96·5%) | 2·72 (1·98–3·73) | <0·0001 | 2·03 (1·38–2·99) | 0·0003 | 2·43 (1·73–3·42) | <0·0001 | 1·75 (1·26–2·44) | 0·0017 |

| Indian | 43/6588 (0·7%) | 6543/6588 (99·3%) | 0·60 (0·39–0·90) | 0·015 | 0·50 (0·30–0·83) | 0·0072 | 0·70 (0·45–1·09) | 0·11 | 0·54 (0·35–0·86) | 0·010 |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||

| No | 8042/98 473 (8·2%) | 90 431/98 473 (91·8%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 3857/50 770 (7·6%) | 46 913/50 770 (92·4%) | 0·51 (0·49–0·54) | <0·0001 | 0·75 (0·70–0·81) | <0·0001 | 0·58 (0·55–0·60) | <0·0001 | 0·87 (0·83–0·92) | <0·0001 |

| Diabetes | ||||||||||

| No | 8954/111 449 (8·0%) | 102 495/111 449 (92·0%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 2669/37 305 (7·2%) | 34 636/37 305 (92·8%) | 0·44 (0·42–0·47) | <0·0001 | 0·55 (0·51–0·59) | <0·0001 | 0·53 (0·50–0·55) | <0·0001 | 0·62 (0·58–0·66) | <0·0001 |

| Chronic cardiac disease | ||||||||||

| No | 10 284/142 253 (7·2%) | 131 969/142 253 (92·8%) | 1 (ref) | .. | .. | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 293/3374 (8·7%) | 3081/3374 (91·3%) | 0·79 (0·69–0·90) | <0·0001 | .. | .. | 1·12 (1·00–1·25) | 0·044 | 1·41 (1·24–1·60) | <0·0001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease or asthma | ||||||||||

| No | 9943/137 862 (7·2%) | 127 919/137 862 (92·8%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 975/9626 (10·1%) | 8651/9626 (89·9%) | 0·79 (0·73–0·85) | <0·0001 | 0·85 (0·75–0·96) | 0·0093 | 0·93 (0·87–0·99) | 0·021 | 0·89 (0·82–0·97) | 0·0063 |

| Chronic renal disease | ||||||||||

| No | 9982/141 708 (7·0%) | 131 726/141 708 (93·0%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 541/3746 (14·4%) | 3205/3746 (85·6%) | 0·93 (0·84–1·02) | 0·13 | 1·72 (1·47–2·02) | <0·0001 | 1·26 (1·16–1·38) | <0·0001 | 1·88 (1·69–2·09) | <0·0001 |

| Malignancy in the past 5 years | ||||||||||

| No | 10 284/144 246 (7·1%) | 133 962/144 246 (92·9%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 154/985 (15·6%) | 831/985 (84·4%) | 1·78 (1·47–2·16) | <0·0001 | 1·35 (1·04–1·75) | 0·022 | 2·15 (1·86–2·48) | <0·0001 | 1·98 (1·59–2·46) | <0·0001 |

| Tuberculosis | ||||||||||

| Never | 7807/138 842 (5·6%) | 131 035/138 842 (94·4%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Past | 1207/2960 (40·8%) | 1753/2960 (59·2%) | 4·81 (4·41–5·24) | <0·0001 | 4·88 (4·22–5·64) | <0·0001 | 4·24 (3·92–4·59) | <0·0001 | 3·55 (3·20–3·95) | <0·0001 |

| Current | 360/954 (37·7%) | 594/954 (62·3%) | 9·44 (7·99–11·15) | <0·0001 | 7·35 (6·07–8·92) | <0·0001 | 6·42 (5·55–7·42) | <0·0001 | 5·55 (4·64–6·65) | <0·0001 |

| Current and past | 745/1259 (59·2%) | 514/1259 (40·8%) | 7·98 (6·97–9·12) | <0·0001 | 6·84 (5·39–8·70) | <0·0001 | 14·30 (13·05–15·66) | <0·0001 | 11·19 (9·98–12·54) | <0·0001 |

| Health sector | ||||||||||

| Private | 2057/94 167 (2·2%) | 92 110/94 167 (97·8%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Public | 11 736/57 612 (20·4%) | 45 876/57 612 (79·6%) | 21·86 (16·78–28·46) | <0·0001 | 6·51 (5·22–8·12) | <0·0001 | 17·89 (14·90–21·48) | <0·0001 | 13·59 (11·51–16·04) | <0·0001 |

| Province | ||||||||||

| Western Cape | 4178/34 530 (12·1%) | 30 352/34 530 (87·9%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Eastern Cape | 1898/20 468 (9·3%) | 18 570/20 468 (90·7%) | 1·74 (0·97–3·13) | 0·062 | 0·25 (0·18–0·36) | <0·0001 | 1·45 (0·89–2·35) | 0·13 | 0·65 (0·50–0·84) | 0·0010 |

| Free State | 866/10 453 (8·3%) | 9587/10 453 (91·7%) | 1·23 (0·61–2·50) | 0·56 | 0·32 (0·22–0·48) | <0·0001 | 1·10 (0·61–1·96) | 0·76 | 0·74 (0·55–1·01) | 0·059 |

| Gauteng | 1603/35 337 (4·5%) | 33 734/35 337 (95·5%) | 0·37 (0·21–0·66) | 0·0007 | 0·23 (0·16–0·33) | <0·0001 | 0·38 (0·24–0·61) | <0·0001 | 0·76 (0·59–0·98) | 0·034 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 3321/30 459 (10·9%) | 27 138/30 459 (89·1%) | 1·76 (0·99–3·12) | 0·052 | 0·46 (0·33–0·63) | <0·0001 | 1·65 (1·04–2·64) | 0·035 | 1·50 (1·17–1·92) | 0·0014 |

| Limpopo | 469/5790 (8·1%) | 5321/5790 (91·9%) | 2·97 (1·45–6·09) | 0·0030 | 0·27 (0·18–0·42) | <0·0001 | 1·88 (1·04–3·39) | 0·036 | 0·74 (0·55–1·01) | 0·059 |

| Mpumalanga | 612/5173 (11·8%) | 4561/5173 (88·2%) | 5·79 (2·61–12·84) | <0·0001 | 0·25 (0·15–0·41) | <0·0001 | 3·27 (1·73–6·18) | <0·0001 | 1·64 (1·17–2·30) | 0·0039 |

| North West | 722/7196 (10·0%) | 6474/7196 (90·0%) | 1·11 (0·44–2·81) | 0·82 | 0·24 (0·14–0·43) | <0·0001 | 1·30 (0·62–2·71) | 0·49 | 1·07 (0·73–1·57) | 0·73 |

| Northern Cape | 124/2373 (5·2%) | 2249/2373 (94·8%) | 1·28 (0·43–3·77) | 0·66 | 0·26 (0·12–0·57) | 0·0007 | 0·88 (0·37–2·06) | 0·76 | 0·75 (0·48–1·20) | 0·23 |

| Outcome | ||||||||||

| Discharged alive | 10 386/117 675 (8·8%) | 107 289/117 675 (91·2%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Died in hospital | 3407/34 104 (10·0%) | 30 697/34 104 (90·0%) | 0·83 (0·79–0·87) | <0·0001 | 1·23 (1·15–1·33) | <0·0001 | 0·86 (0·82–0·90) | <0·0001 | 1·25 (1·18–1·33) | <0·0001 |

Data are n/N (%) unless otherwise stated. OR=odds ratio.

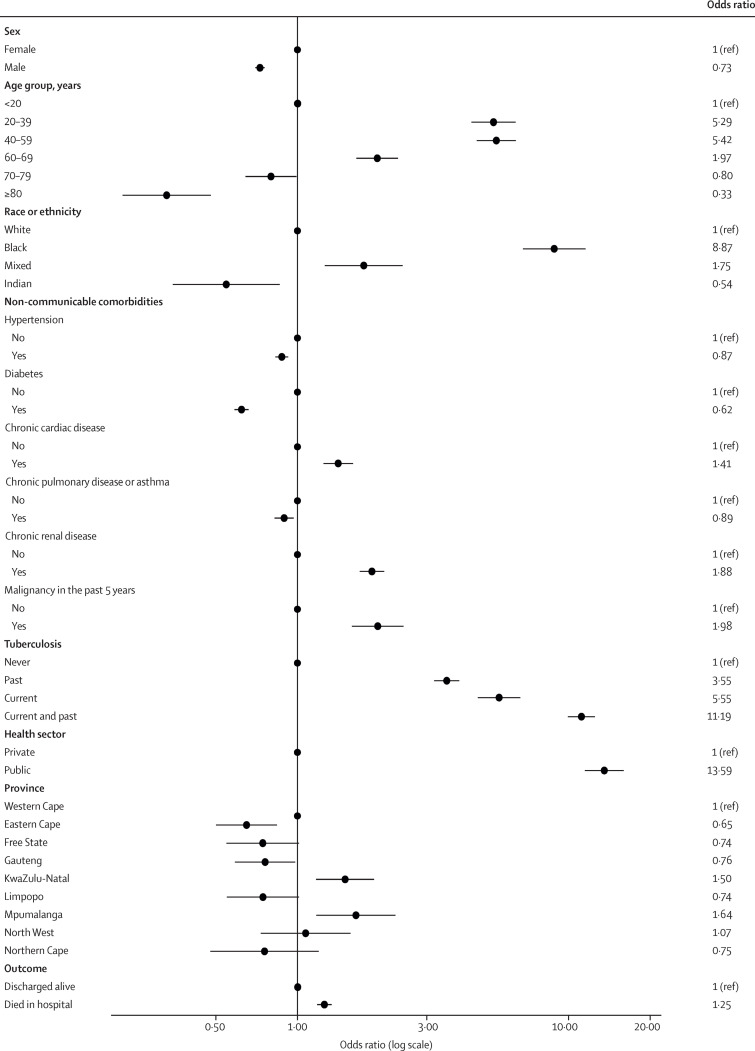

Compared with HIV-uninfected patients admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection, those with HIV were more likely to be aged 20–39 years, 40–59 years, and 60–69 years compared with younger than 20 years; be Black or mixed race compared with White race; be admitted in the public health sector; have comorbid chronic cardiac disease, chronic renal disease, malignancy in the past 5 years, current tuberculosis, past tuberculosis, and past and current tuberculosis; and die in hospital. People with HIV were less likely to be aged 70–79 years and 80 years or older; be male; be of Indian ancestry; and to have comorbid hypertension, diabetes, and chronic pulmonary disease or asthma (table 1; figure 2 ). HIV prevalence among patients with COVID-19 varied, with lower prevalence in the Eastern Cape and Gauteng provinces and higher prevalence in the KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga provinces (table 1).

Figure 2.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with HIV infection

Dots represent adjusted odds ratios and error bars represent 95% CIs. See table 1 for 95% CI values.

Of the 219 265 patients with recorded outcomes, 168 228 (76·7%) were discharged alive and 51 037 (23·3%) died. The unadjusted in-hospital case fatality ratio for people with HIV was 3407 (24·7%) of 13 793 compared with 30 697 (22·2%) of 137 986 for HIV-uninfected individuals.

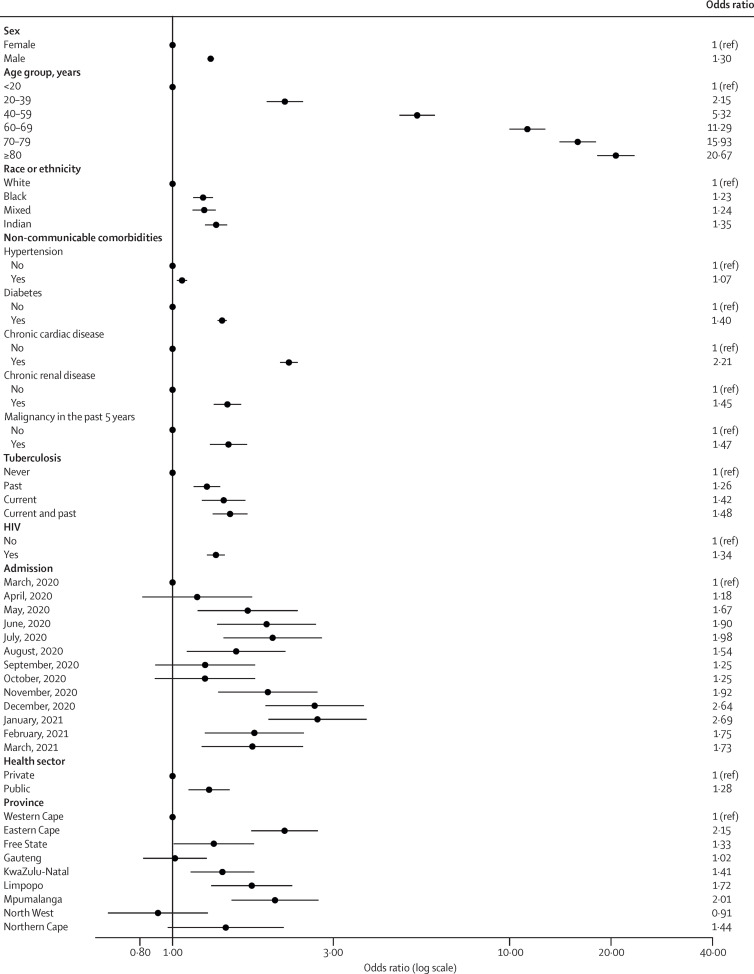

Factors statistically associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality were increasing age 20–39 years, 40–59 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years, and 80 years or older, compared with younger than 20 years; male sex; Black, mixed race, and Indian ancestry compared with White race; having comorbid hypertension, diabetes, chronic cardiac disease, chronic renal disease, malignancy in the past 5 years, HIV, past tuberculosis, current tuberculosis or both past and current tuberculosis; and being admitted in the public health sector. COVID-19 in-hospital mortality increased each month of the epidemic to the peak of the first wave in July, 2020, then decreased between waves and increased again to the peak of the second wave in January, 2021. COVID-19 in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in Eastern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga, compared with Western Cape (table 2 ; figure 3 ). The unimputed multivariate analysis showed similar findings (table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality among patients admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, South Africa (n=219 265)

| Case fatality ratio | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) unimputed | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) unimputed | p value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) imputed | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) imputed* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 26 466/121 937 (21·7%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Male | 24 490/96 890 (25·3%) | 1·32 (1·29–1·34) | <0·0001 | 1·32 (1·27–1·37) | <0·0001 | 1·32 (1·29–1·34) | <0·0001 | 1·30 (1·27–1·33) | <0·0001 |

| Age, years | |||||||||

| <20 | 300/8605 (3·5%) | 1 (ref) | <0·0001 | 1 (ref) | <0·0001 | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| 20–39 | 3516/44 605 (7·9%) | 2·38 (2·11–2·70) | <0·0001 | 2·60 (2·02–3·28) | <0·0001 | 2·38 (2·11–2·70) | <0·0001 | 2·15 (1·90–2·44) | <0·0001 |

| 40–59 | 16 285/86 095 (18·9%) | 6·88 (6·11–7·76) | <0·0001 | 6·90 (5·45–8·74) | <0·0001 | 6·88 (6·11–7·76) | <0·0001 | 5·32 (4·71–6·00) | <0·0001 |

| 60–69 | 14 412/41 077 (35·1%) | 15·08 (13·38–17·01) | <0·0001 | 14·41 (11·36–18·28) | <0·0001 | 15·08 (13·38–17·01) | <0·0001 | 11·29 (9·99–12·76) | <0·0001 |

| 70–79 | 10 509/24 943 (42·1%) | 20·75 (18·38–23·42) | <0·0001 | 20·85 (16·40–26·49) | <0·0001 | 20·75 (18·38–23·42) | <0·0001 | 15·93 (14·06–18·04) | <0·0001 |

| ≥80 | 6015/13 940 (43·1%) | 24·85 (21·96–28·12) | <0·0001 | 28·89 (22·62–36·89) | <0·0001 | 24·85 (21·96–28·12) | <0·0001 | 20·67 (18·19–23·48) | <0·0001 |

| Race or ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 2689/12 661 (21·2%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Black | 28 602/114 571 (25·0%) | 0·77 (0·73–0·81) | <0·0001 | 1·21 (1·13–1·30) | <0·0001 | 0·79 (0·74–0·84) | <0·0001 | 1·23 (1·15–1·32) | <0·0001 |

| Mixed | 2310/10 053 (23·0%) | 0·92 (0·85–0·99) | 0·022 | 1·31 (1·18–1·44) | <0·0001 | 0·89 (0·83–0·96) | 0·0037 | 1·24 (1·15–1·34) | <0·0001 |

| Indian | 2014/8591 (23·4%) | 1·08 (1·00–1·17) | 0·046 | 1·32 (1·20–1·46) | <0·0001 | 1·07 (0·99–1·14) | 0·078 | 1·35 (1·25–1·45) | <0·0001 |

| Hypertension | |||||||||

| No | 19 123/102 252 (18·7%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 19 668/61 098 (32·2%) | 1·92 (1·87–1·97) | <0·0001 | 1·16 (1·11–1·21) | <0·0001 | 2·03 (1·97–2·08) | <0·0001 | 1·07 (1·03–1·10) | 0·0004 |

| Diabetes | |||||||||

| No | 22 742/116 047 (19·6%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 14 707/43 885 (33·5%) | 1·92 (1·87–1·98) | <0·0001 | 1·42 (1·36–1·48) | <0·0001 | 2·01 (1·96–2·06) | <0·0001 | 1·40 (1·36–1·45) | <0·0001 |

| Chronic cardiac disease | |||||||||

| No | 32 498/145 854 (22·3%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | ..ç |

| Yes | 1564/4178 (37·4%) | 1·95 (1·82–2·09) | <0·0001 | 1·22 (1·11–1·34) | <0·0001 | 3·47 (3·28–3·66) | <0·0001 | 2·21 (2·08–2·35) | <0·0001 |

| Chronic renal disease | |||||||||

| No | 32 009/145 095 (22·1%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 1785/4121 (43·3%) | 2·56 (2·39–2·74) | <0·0001 | 1·68 (1·50–1·89) | <0·0001 | 2·68 (2·51–2·87) | <0·0001 | 1·45 (1·33–1·60) | <0·0001 |

| Malignancy in the past 5 years | |||||||||

| No | 33 136/147 659 (22·4%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 439/1143 (38·4%) | 2·04 (1·80–2·32) | <0·0001 | 1·75 (1·48–2·08) | <0·0001 | 2·24 (2·02–2·49) | <0·0001 | 1·47 (1·29–1·66) | <0·0001 |

| Tuberculosis | |||||||||

| Never | 31 276/141 099 (22·2%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Past | 759/3001 (25·3%) | 0·93 (0·85–1·02) | 0·12 | 1·12 (0·95–1·30) | 0·17 | 1·16 (1·07–1·26) | 0·0006 | 1·26 (1·15–1·38) | <0·0001 |

| Current | 258/993 (26·0%) | 1·08 (0·93–1·25) | 0·33 | 1·58 (1·30–1·92) | <0·0001 | 1·04 (0·90–1·20) | 0·59 | 1·42 (1·22–1·64) | <0·0001 |

| Current and past | 307/1288 (23·8%) | 0·98 (0·85–1·14) | 0·80 | 2·05 (1·59–2·64) | <0·0001 | 1·14 (1·03–1·27) | 0·013 | 1·48 (1·32–1·67) | <0·0001 |

| HIV | |||||||||

| No | 30 697/137 986 (22·2%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Yes | 3407/13 793 (24·7%) | 0·84 (0·80–0·88) | <0·0001 | 1·29 (1·20–1·39) | <0·0001 | 0·86 (0·82–0·90) | <0·0001 | 1·34 (1·27–1·43) | <0·0001 |

| Admission | |||||||||

| March, 2020 | 45/400 (11·3%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| April, 2020 | 185/1449 (12·8%) | 1·26 (0·88–1·79) | 0·21 | 0·83 (0·48–1·43) | 0·51 | 1·26 (0·88–1·79) | 0·21 | 1·18 (0·81–1·72) | 0·38 |

| May, 2020 | 1072/5787 (18·5%) | 1·89 (1·37–2·61) | 0·0001 | 1·12 (0·68–1·84) | 0·66 | 1·89 (1·37–2·61) | 0·0001 | 1·67 (1·19–2·35) | 0·0033 |

| June, 2020 | 3698/18 209 (20·3%) | 2·22 (1·62–3·06) | <0·0001 | 1·39 (0·85–2·26) | 0·19 | 2·22 (1·62–3·05) | <0·0001 | 1·90 (1·36–2·66) | 0·0002 |

| July, 2020 | 8335/38 226 (21·8%) | 2·43 (1·77–3·34) | <0·0001 | 1·45 (0·89–2·37) | 0·13 | 2·43 (1·77–3·34) | <0·0001 | 1·98 (1·42–2·77) | 0·0001 |

| August, 2020 | 3707/19 671 (18·8%) | 2·00 (1·46–2·75) | <0·0001 | 1·19 (0·73–1·95) | 0·49 | 2·00 (1·45–2·75) | <0·0001 | 1·54 (1·10–2·16) | 0·012 |

| September, 2020 | 1314/8851 (14·8%) | 1·51 (1·09–2·08) | 0·013 | 0·94 (0·57–1·55) | 0·80 | 1·51 (1·09–2·08) | 0·013 | 1·25 (0·89–1·76) | 0·20 |

| October, 2020 | 1167/7735 (15·1%) | 1·45 (1·05–2·00) | 0·024 | 0·95 (0·57–1·57) | 0·84 | 1·45 (1·05–2·00) | 0·024 | 1·25 (0·89–1·76) | 0·20 |

| November, 2020 | 2506/11 110 (22·6%) | 2·17 (1·58–2·99) | <0·0001 | 1·63 (0·99–2·68) | 0·053 | 2·17 (1·58–2·99) | <0·0001 | 1·92 (1·37–2·69) | 0·0002 |

| December, 2020 | 10 621/39 582 (26·8%) | 2·98 (2·17–4·09) | <0·0001 | 1·94 (1·19–3·17) | 0·0081 | 2·98 (2·17–4·09) | <0·0001 | 2·64 (1·89–3·69) | <0·0001 |

| January, 2021 | 15 264/52 019 (29·3%) | 3·33 (2·42–4·57) | <0·0001 | 1·86 (1·14–3·04) | 0·013 | 3·32 (2·42–4·56) | <0·0001 | 2·69 (1·92–3·76) | <0·0001 |

| February, 2021 | 2380/11 940 (19·9%) | 2·00 (1·45–2·75) | <0·0001 | 1·34 (0·81–2·20) | 0·25 | 2·00 (1·45–2·75) | <0·0001 | 1·75 (1·25–2·45) | 0·0012 |

| March, 2021 | 737/4235 (17·4%) | 1·71 (1·23–2·37) | 0·0013 | 1·47 (0·87–2·46) | 0·15 | 1·71 (1·23–2·36) | 0·0014 | 1·73 (1·22–2·43) | 0·0020 |

| Health sector | |||||||||

| Private | 19 763/105 409 (18·7%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Public | 31 274/113 856 (27·5%) | 1·99 (1·70–2·33) | <0·0001 | 1·50 (1·28–1·75) | <0·0001 | 1·99 (1·70–2·33) | <0·0001 | 1·28 (1·12–1·48) | 0·0005 |

| Province | |||||||||

| Western Cape | 9739/45 341 (21·5%) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. |

| Eastern Cape | 9334/28 671 (32·6%) | 2·32 (1·79–3·01) | <0·0001 | 1·94 (1·51–2·49) | <0·0001 | 2·32 (1·79–3·01) | <0·0001 | 2·15 (1·71–2·70) | <0·0001 |

| Free State | 2627/11 759 (22·3%) | 1·14 (0·83–1·56) | 0·43 | 1·19 (0·89–1·59) | 0·24 | 1·14 (0·83–1·56) | 0·43 | 1·33 (1·01–1·74) | 0·044 |

| Gauteng | 11 938/59 548 (20·0%) | 0·76 (0·60–0·98) | 0·033 | 1·15 (0·90–1·47) | 0·28 | 0·76 (0·60–0·98) | 0·033 | 1·02 (0·82–1·26) | 0·88 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 10 411/42 712 (24·4%) | 1·45 (1·13–1·86) | 0·0040 | 1·41 (1·11–1·80) | 0·0056 | 1·45 (1·13–1·86) | 0·0040 | 1·41 (1·13–1·75) | 0·0021 |

| Limpopo | 2431/8110 (30·0%) | 1·98 (1·44–2·72) | <0·0001 | 1·32 (0·95–1·82) | 0·095 | 1·98 (1·44–2·72) | <0·0001 | 1·72 (1·30–2·27) | 0·0001 |

| Mpumalanga | 2209/8287 (26·7%) | 2·27 (1·62–3·20) | <0·0001 | 1·43 (0·99–2·06) | 0·060 | 2·27 (1·62–3·20) | <0·0001 | 2·01 (1·50–2·71) | <0·0001 |

| North West | 1651/11 343 (14·6%) | 0·73 (0·49–1·09) | 0·12 | 1·18 (0·79–1·76) | 0·43 | 0·73 (0·49–1·09) | 0·12 | 0·91 (0·64–1·27) | 0·57 |

| Northern Cape | 697/3494 (19·9%) | 1·32 (0·84–2·08) | 0·23 | 1·43 (0·85–2·40) | 0·18 | 1·32 (0·84–2·08) | 0·23 | 1·44 (0·97–2·14) | 0·073 |

OR=odds ratio.

Chronic pulmonary disease and asthma variable excluded in the final multivariate model due to being not significant.

Figure 3.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality

Dots represent adjusted odds ratios and error bars represent 95% CIs. See table 2 for 95% CI values.

A sensitivity analysis of risk factors for COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in the public and private sectors (appendix pp 10–11) confirmed increased association of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality with age, male sex, race, and comorbidities. Divergent findings in the health sector analysis included hypertension being associated with COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in the private but not the public sector; a stronger effect of age, sex, race, and comorbidities in the private sector; and a stronger effect of province and month of admission in the public sector, with a significant difference in COVID-19 in-hospital mortality observed only at the peak of the second wave in the private sector.

When adjusting for age, sex, race or ethnicity, health sector, province, month of admission, non-communicable diseases, and past or current tuberculosis, compared with HIV-negative individuals, people with HIV not on ART were more likely to die in hospital than those on ART; people with HIV with a history of immune suppression (CD4 count <200 cells per μL) were more likely to die in hospital than those with CD4 counts of 200 cells or more per μL; and people with HIV with a history of a viral load of 1000 copies per mL or more were more likely to die in hospital than those with a viral load of less than 1000 copies per mL (table 3 ).

Table 3.

Effect of ART, CD4 cell count, and HIV viral load on COVID-19 in-hospital mortality among people with HIV admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, South Africa

| Case fatality ratio unimputed | Case fatality ratio (95% CI) imputed | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) imputed | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) imputed* | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) imputed* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART status | ||||||||

| HIV negative | 30 697/137 986 (22·2%) | 23·1% (22·9–23·3) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 0·77 (0·72–0·82) | <0·0001 |

| HIV positive on ART | 2046/7484 (27·3%) | 24·6% (23·8–25·4) | 0·85 (0·80–0·90) | <0·0001 | 1·30 (1·22–1·39) | <0·0001 | 1 (ref) | .. |

| HIV positive not on ART | 192/594 (32·3%) | 28·1% (25·2–31·1) | 0·99 (0·86–1·15) | 0·98 | 1·89 (1·60–2·23) | <0·0001 | 1·45 (1·22–1·72) | <0·0001 |

| CD4 count | ||||||||

| HIV negative | 30 697/137 986 (22·2%) | 23·1% (22·9–23·3) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 1·06 (0·93–1·20) | 0·37 |

| HIV positive CD4 count, ≥200 cells per μL | 368/1690 (21·8%) | 19·7% (17·7–21·7) | 0·64 (0·57–0·73) | <0·0001 | 0·95 (0·83–1·08) | 0·37 | 1 (ref) | .. |

| HIV positive CD4 count, <200 cells per μL | 380/1080 (35·2%) | 32·2% (29·9–34·5) | 1·23 (1·09–1·38) | 0·0023 | 2·19 (1·92–2·49) | <0·0001 | 2·31 (1·82–2·93) | <0·0001 |

| Viral load | ||||||||

| HIV negative | 30 697/137 986 (22·2%) | 23·1% (22·9–23·3) | 1 (ref) | .. | 1 (ref) | .. | 0·83 (0·76–0·90) | 0·0002 |

| HIV positive viral load, <1000 HIV RNA copies per mL | 316/1273 (24·8%) | 24·7% (23·0–26·4) | 0·86 (0·78–0·94) | 0·0029 | 1·21 (1·11–1·32) | 0·0002 | 1 (ref) | .. |

| HIV positive viral load, ≥1000 HIV RNA copies per mL | 128/443 (28·9%) | 25·2% (21·0–29·4) | 0·85 (0·69–1·05) | 0·13 | 1·88 (1·53–2·31) | <0·0001 | 1·55 (1·20–2·01) | 0·0029 |

Model adjusted for age, sex, race or ethnicity, health sector, province, month of admission, non-communicable comorbidities, and past or current tuberculosis. ART=antiretroviral therapy. OR=odds ratio.

Output from the same model but with different reference categories to assess the effect of the predictors compared with HIV-uninfected individuals (model 1) or individuals on ART, with high CD4 count, or with low viral load (model 2).

Among people living with HIV, the prevalence of other comorbidities was 29·2% compared with 30·8% among HIV-uninfected individuals. In a multivariable model adjusting for age, sex, race or ethnicity, HIV (for the non-stratified model on HIV status only), health sector, province, and month of admission, there were increasing odds of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality for individuals with multiple non-HIV comorbidities, irrespective of HIV status (table 4 ). There was no statistical evidence of interaction between the presence of other multiple comorbidities and HIV infection status on COVID-19 in-hospital mortality (table 4). No interaction was found for individual comorbidities and HIV infection status on COVID-19 in-hospital mortality (appendix p 12).

Table 4.

Effect of single or multiple non-communicable comorbidities on COVID-19 in-hospital mortality among patients admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, South Africa

| Case fatality ratio unimputed | Case fatality ratio (95% CI) imputed | Adjusted OR (95% CI) imputed* | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any individual | |||||

| Comorbid condition | |||||

| No comorbidity | 2507/15 469 (16·2%) | 15·6% (15·3–15·9) | 1 (ref) | .. | |

| One comorbidity | 3764/14 402 (26·1%) | 24·1% (23·7–24·6) | 1·34 (1·28–1·39) | <0·0001 | |

| Two comorbidities | 3477/10 137 (34·3%) | 31·7% (31·2–32·2) | 1·66 (1·59–1·74) | <0·0001 | |

| Three or more comorbidities | 1353/3317 (40·8%) | 41·5% (40·7–42·3) | 2·40 (2·28–2·53) | <0·0001 | |

| HIV-negative individuals | |||||

| Comorbid condition | |||||

| No comorbidity | 2074/12 993 (16·0%) | 15·6% (15·3–15·9) | 1 (ref) | .. | |

| One comorbidity | 3277/12 586 (26·0%) | 24·3% (23·8–24·8) | 1·34 (1·28–1·40) | <0·0001 | |

| Two comorbidities | 3082/8962 (34·4%) | 32·0% (31·4–32·6) | 1·66 (1·58–1·74) | <0·0001 | |

| Three or more comorbidities | 1159/2858 (40·6%) | 41·5% (40·4–42·5) | 2·39 (2·24–2·54) | <0·0001 | |

| HIV-positive individuals | |||||

| Comorbid condition | |||||

| No comorbidity | 341/2073 (16·4%) | 15·6% (14·6–16·6) | 1 (ref) | .. | |

| One comorbidity | 384/1524 (25·2%) | 23·2% (21·9–24·5) | 1·34 (1·20–1·49) | <0·0001 | |

| Two comorbidities | 292/932 (31·3%) | 29·4% (27·7–31·0) | 1·67 (1·48–1·90) | <0·0001 | |

| Three or more comorbidities | 143/352 (40·6%) | 41·9% (40·0–43·8) | 2·46 (2·22–2·73) | <0·0001 | |

| Interaction effect of multiple comorbidities with HIV infection (HIV-negative is the reference group) | |||||

| Comorbid condition | |||||

| No comorbidity | NA | NA | 1 (ref) | .. | |

| One comorbidity | NA | NA | 1·00 (0·89–1·12) | 0·98 | |

| Two comorbidities | NA | NA | 1·01 (0·89–1·15) | 0·88 | |

| Three or more comorbidities | NA | NA | 1·03 (0·90–1·17) | 0·65 | |

Comorbid conditions included were a combination of hypertension, chronic cardiac or renal disease, diabetes, malignancy in the past 5 years, and past or current tuberculosis. NA=not applicable.

Model adjusted for age, sex, race or ethnicity, HIV (for the non-stratified model on HIV status only), health sector, province, and month of admission.

Discussion

Among a large cohort of patients admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a high HIV and tuberculosis prevalence setting, although age was the strongest predictor of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality, we found that HIV and tuberculosis were associated with a moderately increased risk of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality, similar to the increased risk associated with other underlying conditions such as diabetes, chronic renal disease, and malignancy in the past 5 years.

This cohort included 13 793 people with HIV and 5282 patients with tuberculosis, and in addition 2312 patients co-infected with SARS-CoV-2, HIV, and tuberculosis. Describing mortality risk among these groups is important because studies have shown that among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, those who also had HIV and tuberculosis had altered T-cell functions and were at risk of more severe disease.28 Large population cohorts from the Western Cape province of South Africa18 and the UK19, 20 and more recent meta-analyses21, 22, 23 found people with HIV to have an increased risk of COVID-19 mortality, with increased in-hospital mortality reported in the Western Cape18 and UK19 studies. Our study, however, could not conclude that HIV is a risk factor at the population level.

We describe an increased risk of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in people with HIV not on ART, with increasing HIV-associated immunosuppression, and with higher viral load, although missing data limited inference. Few studies have explored the effect of the association between ART status, increased immunosuppression, and viraemia on COVID-19 mortality among people with HIV. A Western Cape public sector study found no association with the presence of high viral load or immunosuppression, using latest CD4 cell count and viral load assessment within the past 18 months through linkage with laboratory information systems. This finding could be explained by the fact that our study used a larger dataset over a longer time period, including data from the private sector, and from other provinces with different levels of access to care and treatment and different HIV and tuberculosis burden.

The HIV prevalence in our study was 2·2% in the private sector and 20·4% in the public sector, due to socioeconomic differences in the populations served by each sector. The lower prevalence of HIV (11·7%) in individuals admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection in our study, than in the population among adults (19%), is probably because of the over-representation of private sector COVID-19 admissions and possible under-reporting of comorbidities in the public sector.

The prevalence of other comorbidities, including tuberculosis, malignancy in the past 5 years, and chronic cardiac and renal disease, was high among people with HIV included in our analysis. This high prevalence could be due to antiretroviral drugs. For example, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, which is part of the first-line ART regimen in South Africa, has new or worsening renal failure as one of its side-effects29 and other antiretroviral drugs have side-effects that include hyperlipidaemia, cardiac disease, diabetes, and liver disease.30 Additionally, because people with HIV who are on ART live longer, the risk of developing non-communicable diseases increases with age. HIV-positive people with immunosuppression are also more likely to develop tuberculosis and HIV-related malignancies.31 Increasing numbers of comorbidities were associated with increased risk of COVID-19 mortality, possibly because of poorer overall health status, more compromised immunity, and presence of chronic inflammatory state, which could create a pathway for severe COVID-19.31 The effect was similar in people with HIV and HIV-uninfected individuals.

Age was the strongest predictor of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality, as is reported in meta-analyses.32, 33 In our cohort, 67% of patients who died were younger than 70 years. A review of 27 countries showed a greater proportion of deaths in low-income and middle-income countries occur at younger age, with people younger than 70 years constituting 63% of deaths attributed to COVID-19 in low-income and middle-income countries on average, versus 13% in high-income countries.34 Lower recovery rates in middle-aged people are thought to be driven by high prevalence of pre-existing conditions in younger people in low-income and middle-income countries, and limited access to hospitals and intensive care.34, 35 In low-income and middle-income countries, younger people with comorbidities should also be prioritised for vaccination along with older people.

Although increasing age was the strongest predictor, male sex, non-White race, and chronic underlying illness were associated with increased COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in our study population, as reported in meta-analyses.2, 3, 5, 6 For non-communicable diseases, immune function impairment, severe hypoxaemia, inflammatory activation, and hypercoagulability might be contributory mechanisms for increased mortality.36 Increased mortality associated with non-White race could be related to burden of infection and prevalence of comorbidities in non-White races. Race as a potential proxy for poverty has been shown in other studies as an additional risk factor for higher COVID-19 in-hospital mortality7, 8, 9 and has been suggested to be related to structural discrimination towards marginalised populations, translating to inequities in the delivery of care and barriers to accessing care.7

The COVID-19 in-hospital mortality rate of 23·3% observed among patients in our analysis was at the upper bounds of the range of 15% and 24% reported in meta-analyses.2, 3, 4 Observed variation in case fatality ratios at different times during the epidemic and between regions and health sectors might be a result of population demographics and prevalence of comorbidities, varying population levels of COVID-19, changes in admission practices, the severity of illness in admitted cases, limited access to care, higher numbers of admissions overwhelming services, improved care and treatment options as the pandemic progressed, health services' effectiveness, and completeness of death reporting.8, 37, 38

The main strengths of this analysis are that DATCOV is nationally representative across all provinces, has 100% coverage of hospitals in the public and private health sector in South Africa, and contains close to 220 000 hospital admissions for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

There were several limitations related to the study population and data completeness. Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection reported to DATCOV had COVID-19 symptoms, were admitted for isolation, developed nosocomial COVID-19, or tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 incidentally during admission for unrelated reasons. We were not able to exclude patients admitted for isolation and those with incidental findings because of incomplete data on reason for admission to DATCOV, and this might have introduced bias. Although probably a result of high pressure for hospital beds, such individuals would have made up a small proportion of included cases.

Hospitals reported a small number of deaths (219; appendix p 5) from causes other than COVID-19; however, we have little information on the process used by the hospital for classification of cause of death other than that it is done by the attending clinician. It is possible that other deaths reported to DATCOV have not undergone similar review and might have been misclassified as COVID-19 deaths. It is also possible that some COVID-19 admissions have not been reported to the surveillance system.

Patients who were transferred to other hospitals and had no further records of admission, and those still in hospital at the time of the analysis were excluded. We do not know whether the case fatality ratio among excluded patients would differ from that of included patients, possibly introducing biases. However, given the small number of the excluded patients (1·8%), the effect of biases would be limited.

Private-sector hospital admissions are over-represented because of a lower threshold for admission to private hospitals, resulting in similar proportions of patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospitals in the public and private sector even though they serve 84% and 16% of the population, respectively. This might explain why the HIV prevalence in the overall cohort (11·7%) was lower than the population prevalence of HIV in South Africa (14%).11 However, HIV prevalence among patients aged 20–59 years admitted to hospitals in the public sector was similar to the population HIV prevalence in this age group (appendix p 9).

Data quality in a surveillance system is dependent on the information submitted by health-care institutions. Data on comorbidities were submitted to DATCOV by the hospital based on information contained in the patient's written or electronic hospital record, and were not independently verified because there are no systematic information systems that would verify pre-existing comorbidities. We used multiple imputation to address missing data; however, the validity of the imputed data relies on the assumption that data were missing at random. Fields with the highest proportion of incomplete data included race (33·5%) and comorbidities (25·5–32·2%). The level of control of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, using objective measures such as glycated haemoglobin, was not consistently reported. Other data have shown that individuals with poorly controlled non-communicable diseases were at greater risk of COVID-19 mortality.39

The most recent CD4 cell count and viral load results in the past year were submitted by the hospital based on information contained in the patients' hospital records and not obtained from laboratory information systems. These fields had a high degree of missing data, which is an important limitation given that this analysis focuses on outcomes in people with HIV. Moreover, the hospital did not record the date of the CD4 cell count and viral load tests, so we are not able to calculate the median time between the test and COVID-19 hospital admission, or to be certain that the status of immunosuppression or viraemia had not changed, which might also have introduced measurement bias. It must be noted that DATCOV is a new surveillance system that has not yet been developed to link to other data sources and allow, for example, linkage of laboratory records to the hospital record.

This study confirmed age as the strongest predictor of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in South Africa, as well as sex, race, and comorbid disease. The demonstration of modest increases in COVID-19 in-hospital mortality for individuals with HIV and tuberculosis (particularly those who were not on ART) are important, given the high prevalence of these diseases in South Africa. People with HIV, particularly those with additional comorbidities, would benefit from COVID-19 prevention programmes such as vaccine prioritisation, as well as early referral and treatment programmes that include prioritising linkage and retention to HIV care, ART adherence, virological suppression, and subsequent immune restoration. The increased case fatality ratio in the public sector, in certain provinces, and during the peaks of the epidemic require further interrogation for resources and support to be directed where they are found to be required, ahead of a possible resurgence of cases.

For the DATCOV author group see https://www.nicd.ac.za/diseases-a-z-index/covid-19/surveillance-reports/daily-hospital-surveillance-datcov-report/

Data sharing

Data used in this manuscript are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this Article, after de-identification (text, tables, figures, and appendices), will be shared with investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by an independent review committee (learned intermediary) identified for this purpose. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement. The request will have to be approved by the South African National Department of Health.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

DATCOV, as a national surveillance system, is funded by the South African National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) and the South African National Government. No additional funding was obtained towards the completion of this analysis and the development of this manuscript. We acknowledge the support and contribution from the following organisations: NICD, the South African National Department of Health, the nine provincial departments of health, the Hospital Association of Southern Africa, and the private hospital groups and public sector hospitals that submitted data to DATCOV. Health professionals who submitted data are acknowledged and are listed as the DATCOV author group. We also acknowledge the DATCOV team (Rebone Kai, Simphiwe Dyasi, Tracy Arendse, Beverley Cowper, Kholofelo Skhosana, Felicia Malomane, Monwabisi Blom, Akhona Mzoneli, Salaminah Mhlanga, Bracha Chiger, Busisiwe Ali, Siphamandla Mzobe, Linamandla Qekeleshe, Caroline Magongwa, Caroline Mudara, Lovelyn Nnaji, Richard Welch, Noel Mfongeh, Pinky Manana, Yongama Mangwane, Mami Mokgosana, Thobile Buthelezi, Portia Makwene, and Murray Dryden); the Partners in Performance team (Christo Greyling, David Spade, Winrie Kruger, Supriya Soorju, and Ryan Hudson); and the ComUnity team (Gareth Jane, David Prosser, Tina Hay, Kelello Moloi, and George Ulloa). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributors

DS, SG, and WJ contributed to the literature search. WJ, MM, and CC contributed to the study design and data collection. WJ, PM, and ST contributed to data analysis, and creation of tables and figures. WJ, ST, PM, and MM verified all the underlying data in the study. WJ, ST, CC, TK, SW, and LB contributed to data interpretation and writing. WJ drafted the manuscript and all other authors contributed scientific inputs equally to drafts of the manuscript. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Contributor Information

DATCOV author group: