Oral cancer is an aggressive disease, with an overall survival rate of 50%. Preinvasive histologic abnormalities such as tongue dysplasia represent an early stage of oral cancer; however, there are no treatments to prevent oral carcinoma progression. Here, we combined biomaterials loaded with an immunotherapeutic agent preventing oral cancer progression.

Abstract

Although the principle of systemic treatment to prevent the progression of oral premalignant lesions (OPL) has been demonstrated, there remains a lack of consensus about an optimal approach that balances clinical efficacy with toxicity concerns. Recent advances in cancer therapy using approaches targeting the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) including immune-checkpoint inhibitors indicate that these agents have significant clinically activity against different types of cancers, including oral cancer, and therefore they may provide an effective oral cancer prevention strategy for patients with OPLs. Our past work showed that systemic delivery of a monoclonal antibody to the programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint can inhibit the progression of OPLs to oral cancer in a syngeneic murine oral carcinogenesis model. Here we report a novel approach of local delivery of a PD-1 immune-checkpoint inhibitor loaded using a hydrogel, which significantly reduces the progression of OPLs to carcinomas. In addition, we detected a significant infiltration of regulatory T cells associated with oral lesions with p53 mutation, and a severe loss of expression of STING, which correlated with a decreased infiltration of dendritic cells in the oral lesions. However, a single local dose of PD-1 inhibitor was found to restore stimulator of interferon response cGAMP interactor 1 (STING) and CD11c expression and increase the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the TIME irrespective of the p53 mutational status. Overall, we provide evidence for the potential clinical value of local delivery of biomaterials loaded with anti–PD-1 antibodies to prevent malignant progression of OPLs.

Prevention Relevance:

Oral cancer is an aggressive disease, with an overall survival rate of 50%. Preinvasive histologic abnormalities such as tongue dysplasia represent an early stage of oral cancer; however, there are no treatments to prevent oral carcinoma progression. Here, we combined biomaterials loaded with an immunotherapeutic agent preventing oral cancer progression.

Introduction

Oral cancer represents the sixth most common cancer worldwide with approximately 630,000 new patients diagnosed annually, resulting in more than 350,000 deaths every year (1). More than 90% of head and neck cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC), many of which arise from the progression of oral premalignant lesions (OPL) through the accumulation of genomic alterations that arise as a result of the host's genetic predisposition to accumulation of DNA damage and environmental exposure to carcinogens including tobacco and alcohol (2–4).

Studies of the mutational landscape of non-HPV–associated head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) have demonstrated genomic alterations in TP53 in ∼85% of cases (5). Notably, high-risk TP53 mutations have been associated with poor survival and lack of response to chemotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer, suggesting that cancers of the oral cavity carrying high-risk TP53 mutations can be refractory to standard therapeutic approaches (6–10). Mutations in TP53 have been detected in approximately 30% of the OPLs, suggesting that these mutations arise early during oral tumor development and might influence the progression of OPLs, and their response to preventive strategies (11, 12).

The current standard treatments for OPLs include surgical excision and carbon dioxide laser ablation (13). Unfortunately, 0.13%–34% of these lesions still progress to oral cancer despite treatment (14). Given that treatment failure can also occur as a result of mucosal areas adjacent to the excised OPL proceeding down the multistep carcinogenesis pathway to oral cancer, systemic therapy approaches that can reach the entire mucosal field at risk have been thought to have value in this setting. Although this approach has been proven in principle with administration of retinoids, a recent clinical prevention trial in oral cancer using erlotinib did not improve cancer-free survival in high-risk patients with OPLs, suggesting that inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor is not sufficient to prevent oral cancer progression (15).

Immunotherapy, in the form of immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), such as PD-1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), has recently been introduced as a promising therapeutic option for patients with solid tumors, including oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC; refs. 16–19), which arises from OPLs through a multistep carcinogenesis process (20, 21).

A recent immunoprevention study demonstrated that PD-1 blockage reduces the incidence of OPLs in a carcinogen mouse model. This study used Trp53−/+ heterozygous mutant mice to accelerate OPLs in response to carcinogen. Systemic PD-1 treatment significantly reduced the incidence of malignant lesions with a high infiltration of activated cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, supporting the preventive potential of immune-checkpoint inhibition to contain oral cancer development (22). Furthermore, other studies using the same mouse model had demonstrated that cytokine levels are modulated in response to PD-1 treatment and this treatment also prevented oral lesion progression into carcinoma (23). In a more recent study, PD-1 blockade significantly reduced the formation of oral premalignant or carcinoma incidence in a 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4NQO) carcinogenesis mouse model. Moreover, PD-1 treatment reduced the infiltration of PD-1+ cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in peripheral lymph tissues and promoted T-cell activation (24). These studies strongly support that immune-checkpoint inhibition can potentiate the immune response and inhibit the progression of OPL to invasive cancers.

TP53 mutations are associated with development of oral cancer, but how these mutations in the epithelial cell compartment can affect the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) has yet to be fully defined. Therefore, we chose to use conditional mutant p53 mouse models in carcinogen-induced oral cancer to determine the impact of mutant p53 on neoplastic cells as well as the TIME. ICIs have to be approved for the treatment of OPLs because of the significant risk of potential systemic side effects due to parenteral administration in patients who do not have invasive cancer. Novel technologies to deliver cancer immunotherapy in a more controlled way could prolong and increase accumulation of immunotherapies within the TIME and reduce off-target adverse systemic effects (25). Recently developed delivery platforms for immunotherapies, including nanoparticles, implants, scaffolds, and biomaterials, could therefore, improve the efficacy and safety of immunotherapies to improve patient outcomes (26). Biomaterials allow for spatiotemporal control of delivery reducing off-target toxicity and improving drug efficacy. Lately, multidomain peptide (MDP) biomaterials have been developed and consist of self-assembled peptides that mimic the extracellular matrix by generating a nanofibrous network to create a hydrogel. The hydrogel can encapsulate drugs, cytokines, and growth factors and control their sustained release to permit a sustained payload release in in vivo settings (26–30). Although we have used this MDP to deliver a variety of small molecules and/or proteins in the past, reported for the first time here, we load the MDP hydrogel with anti–PD-1 immune-checkpoint inhibitor to enable local delivery with sustained release. To study the efficacy of local anti–PD-1 immunotherapy delivery to OPLs and define the role of mutant p53 in responsiveness to this treatment, we used a carcinogen, 4NQO, induced oral cancer development model in wild-type and mutant p53R172H mice that mimics the tobacco-mediated oral carcinogenesis observed in humans (31). In addition, we used MDP-based hydrogels as a novel biomaterial to control the payload delivery in a controlled manner, slowing the release of antibody locally. In this study, we monitored oral tumor development, analyzed immune cell infiltration in the premalignant lesions, and determined whether p53 mutations modulate the immunoprevention potential of ICIs.

Materials and Methods

Mouse models

We generated mice in which the endogenous p53R172H mutation was activated using K14Cre mice, which drives the activation of p53R172H mutant and floxed alleles in the oral epithelia. The following groups of mice were used: (i) mice with oral activation of p53R172H and deletion of the floxed wild-type p53 allele (K14Cre; p53R172H/flox); (ii) mice with two p53 wild-type alleles (K14Cre; p53wt/wt). Mouse genotyping and activation of conditional alleles were determined by PCR using genomic DNA purified from mouse tails as previously described (32–33).

To induce oral lesions, mice were exposed to the carcinogen (4NQO, 100 μg/mL) in the drinking water containing 1% sucrose (Fisher Scientific) for 8 weeks, and monitored for oral lesions. A stock solution of 4NQO (50 mg/mL) was prepared by dissolving 4NQO powder (Sigma-Aldrich) in DMSO, which was stored at −20°C until used. All comparative studies were conducted using littermates with the appropriate genotypes. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX).

Immunoprevention preclinical studies

In our study, we used 8–16-week-old mice and each mouse group consisted of seven mice and were distributed and treated as follows: K14Cre; p53 wild-type (5 females and 2 males) were treated with isotype IgG control-hydrogel; K14Cre; p53 wild-type (4 females and 3 males) were treated with PD1 gel; K14Cre; p53 R172H (4 females and 3 males*) were treated with isotype IgG control-hydrogel [*one male were dead during PD-1 treatment; unknown cause]; and K14Cre; p53 R172H (4 females** and 3 males**) were treated with PD-1 gel [**one male and one female were dead during PD-1 treatment; unknown cause]. Oral lesions were induced by 4NQO, as previously described. Four weeks after completion of the 4NQO treatment the mice were injected once in the tongue using 60 μL MDP hydrogel containing 300 μg anti–PD-1 (Bio Cell; cat. #BE0146) or IgG2a (Bio Cell; cat. #BE0089). Because tongue microscopic lesions cannot be visualized at 4 weeks after exposure to 4NQO, we decided to inject 20 μL in three distinct sites (two dorsal and one central tongue) to facilitate drug distribution within the tongue.

All animals underwent weekly examination of the oral cavity followed by necropsy for tissue retrieval five weeks after completion of treatment. Tumor-bearing mice were euthanized by CO2. Finally, oral tissues were surgically excised, measured, photographed, and formalin fixed for histopathologic studies.

Peptide synthesis

Reagents for peptide synthesis reagents were acquired from EMD Chemicals. Both manual synthesis (typically performed at 0.15 mmol scale) and an Apex Focus XC (Aapptec) automatic synthesizer (typically performed at 0.45 mmol scale) were used for synthesis of multidomain peptides K2(SL)6K2 (K2-MDP). Peptides were synthesized using standard F-MOC chemistry and solid-phase peptide synthesis methods described previously (34–37). All peptides were N-terminally acetylated and C-terminally amidated. Peptides were cleaved from solid-phase resin by shaking for 3 hours with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and protecting scavengers, in a 2:1:1:18 ratio of Milli-Q (MQ) H2O: triisopropylsilane (TIPS): anisole: TFA. Rotary evaporation was used to remove excess TFA, and trituration with cold diethyl ether yielded crude peptide. The peptide was pH adjusted to approximately 7.0, and dialyzed against MQ water for 5–7 days to remove small-molecule scavengers, TFA, and other contaminants using 100–500 Da MWCO dialysis tubing (Spectra/Por, Spectrum Laboratories Inc.). After dialysis, peptide solutions were pH adjusted to pH 7.2–7.4, after which 0.2-μm filters were used to sterile filter the solutions, which were frozen at −80°C and lyophilized to dried powder for storage at −20°C. Peptides were analyzed before and after dialysis by Autoflex MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Instruments) for confirmation of expected peptide mass.

Hydrogel preparation and drug loading

All chemicals not otherwise specified were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For preparation of sterile MDP hydrogels, 2% wt/vol solutions were dissolved in 298 mmol/L sucrose to support cytocompatibility. Anti–PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor antibodies and IgG isotype controls were purchased from Bio X Cell. Peptide stock solutions (K2-MDP) were first prepared at 4% wt/vol in 298 mmol/L sucrose. The target final loading concentrations of checkpoint inhibitor antibodies within the gels were 300 μg anti–PD-1 per 60 μL gel (5 μg/μL for PD-1) or the same loading concentration of respective isotype IgG for negative control tests. The antibody stocks were provided in PBS, a buffer that is compatible for peptide hydrogelation via phosphate anion cross-linking of charged peptide nanofibers.

The volume of antibody stock solution (usually provided at stock concentrations of ∼7–9 μg/μL) required to achieve the final desired dose in the gel was then calculated, typically requiring a mixing of 1 part 4% wt/vol peptide with 2–3 parts antibody stock solution (with any leftover volume supplemented with additional PBS). The final antibody-loaded hydrogel formulations were 0.75X PBS, 75 mmol/L sucrose, 1% wt/vol peptide (10 mg/mL, ∼5–6 mmol/L), 5 μg/μL PD-1 or isotype control.

Histology and IHC analysis

The tongues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature for at least 24 hours. Then, the tissue was transferred to 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Histologic sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or processed for IHC analysis. H&E staining was used for histopathologic analysis. Tongue lesions were diagnosed based on worse diagnosis based on the evaluation of the whole tongue and three slides per mouse were analyzed by a pathologist blinded to the treatment group. The oral lesions were classified as previously described (22). Slides were subjected to IHC staining with indicated antibodies. The primary antibodies used for IHC were CD8a (Synaptic Systems, 1:1,000, cat. # 361003), CD4 (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100, cat. #25229), FOXP3 (eBioscience, 1:100, cat. #14-5773-82), PD-1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100, cat. #84651S), CD11C (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:200, cat. #97585), and STING (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100, cat. #13647). Images were captured on a DMLA microscope equipped with a DFC310 FX camera (Leica Microsystems). We used 10× objective to take images and included 100 mm bar scale to frame 1 mm2 area. Next, the images were analyzed in a bigger screen, and a grid was superimposed to delimit area and facilitate immunostained cell quantification. We also consider subcellular staining marker like FOXP3 (nuclear) CD4, CD8, PD-1, CD11C (cell surface), and STING (intracellular). The quantification score was based on the number of positive stained cells per mm2 area. The low- and high-grade oral lesions were heterogeneous in length and width; therefore, IHC quantification scored as density of cells, defined as the number of positive cells per mm2. Quantification was evaluated by the same pathologist in the previous report (22).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software). All data are presented as mean ± standard error. Two-tailed Student t test, one-way ANOVA, and χ2 test were used to analyze the data. P values <0.05 were considered significant, defined *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Results

Biomaterial loaded with anti–PD-1 antibody significantly inhibits malignant progression of 4NQO-induced oral lesions

To evaluate the effect of a PD-1 immune-checkpoint inhibitor in preventing the transition of oral premalignant to carcinoma lesions, we exposed mutant p53R172H and p53 wild-type mice to carcinogen 4NQO (100 μg/mL) in drinking water for 8 weeks (Fig. 1A). After four weeks of carcinogen treatment termination, we evaluated the efficacy of local immunotherapy administration using MDP-based hydrogels as a novel biomaterial to control the payload release of anti–PD-1 antibody and isotype control IgG2a to reduce off-target toxicity in the oral cavity. We administrated a single dose of PD-1 antibody and isotype control IgG2a in hydrogel, and five weeks later mouse tongues were harvested, fixed, and processed to compare the incidence of both low-grade and high-grade lesions in the control and treated groups (Fig. 1A). During the collection of tissues, we observed relatively higher numbers of macroscopic lesions in the tongues of the mice treated with isotype control with the greatest number of macroscopic lesions seen in mutant p53R172H mice (Supplementary Fig. S1). Although male and female mice were used, we did not observe a difference in OPLs by sex. Next, blinded histopathologic analysis by independent individuals revealed that control and treatment groups developed low-grade lesions, consisting of mild and/or moderate dysplasia and high-grade lesions consisting of severe dysplasia and/or in situ carcinoma (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Experimental carcinogen-induced mouse model and local immunotherapy delivery reduces oral lesion incidence. A, Study timeline and end points for immunotherapy studies. B, Representative lesions and histopathology of 4NQO-induced oral lesions in the mouse tongue, scale ruler (mm). Photomicrographs show the histopathologic progression in this model system, mild, moderate, severe dysplasia, and carcinoma in situ. Scale bars, 200 and 50 μm, top and bottom panels, respectively. C, The square shows a magnification area of each histologic stage, and the table below the graph represents the incidence of normal, low-, and high-grade incidence of lesions after treatment in each mouse group (n = 5–7).

The histopathologic analysis revealed that p53 wild-type mice treated with PD-1 gel had a reduced lesion percentage (14.29%) in low and high-grade lesions and 71.42% of the mice were diagnosed with normal tissue. Wild-type mice treated with IgG control had relatively higher numbers of low and high-grade lesions (57.14 and 28.57% respectively) suggesting that treatment with the PD-1 antibody prevented or even eliminated the incidence of oral lesions (Fig. 1C). Moreover, mutant p53R172H mice treated with PD-1 gel showed a reduced frequency of high-grade lesions compared with control mice (20% vs. 60% respectively; Fig. 1C). Overall, these results strongly indicate that local immunotherapy delivery can prevent the malignant progression of OPLs in mutant and wild-type p53 mice. Furthermore, mutant p53R172H mice developed more high-grade lesions compared with wild-type mice and a significant increase in low-grade lesions even after PD-1 treatment, suggesting that mutant p53R172H accelerates carcinogen-induced oral tumor development than p53 wild-type mice and drives resistance to immunopreventive treatment (Fig. 1C). Finally, we can conclude the PD-1 treatment in p53 wild-type mice is more efficient compared with p53 mutant mice treated with isotype IgG control (Supplementary Fig. S2). Interestingly, we have confirmed experimentally that local and systemic delivery show very similar results. The results seen with delivery of a single PD-1 gel dose is comparable with those seen with eight anti–PD-1 doses systemically administrated in p53 wild-type mice as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. Finally, mice treated with intraperitoneal administration of anti–PD-1 showed a trend in weight loss at the end of the study; however, it was not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. S4).

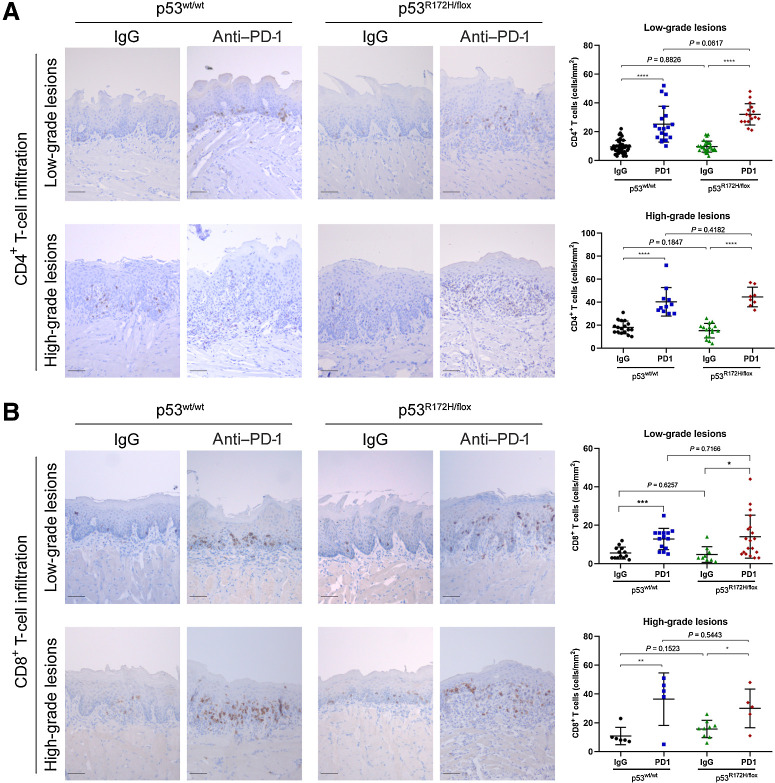

Increased infiltration of effector and cytotoxic T lymphocytes after local delivery of anti–PD-1

To determine the effect of anti–PD-1 treatment on the activation of the immune system, we stained tissue sections of oral lesions induced by 4NQO to detect the infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. We observed that wild-type and mutant p53 mice treated with IgG isotype control showed similar infiltration of CD4+ T cells in low- and high-grade oral lesions (Fig. 2A). This was surprising because we assumed that oncogenic p53R172H might prevent infiltration of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. However, an increased infiltration of CD4+ T cells was detected after PD-1 gel treatment in low- and high-grade oral lesions in wild-type and mutant p53R172H mice. As previously observed, there was no difference of CD4+ T-cell infiltration between wild-type and mutant p53 mice.

Figure 2.

Increased infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in oral lesions after anti–PD-1 treatment. A, Representative images of low- and high-grade oral lesions and IHC quantification signal of CD4+ T cells (right side graphs). B, Representative IHC images of infiltrating CD8+ T cells in oral lesions. A significant difference of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was detected between untreated and PD-1 treated mice groups. Immunostaining signal was defined as the number of positive cells per mm2. Right graphs: *, P < 0.05; **, P <0.01; ***, P <0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Next, immunostaining of CD8+ T cells showed that local delivery of PD-1 was associated with increased infiltration in low- and high-grade oral dysplasia demonstrating the efficacy of immune cells to infiltrate tumorigenic lesions (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, CD8+ T-cell infiltration was not affected by mutant p53R172H expressed in oral dysplasia or carcinoma, suggesting that oncogenic mutant p53 might affect an alternative pathway to disrupt tumor immunity in oral cancer.

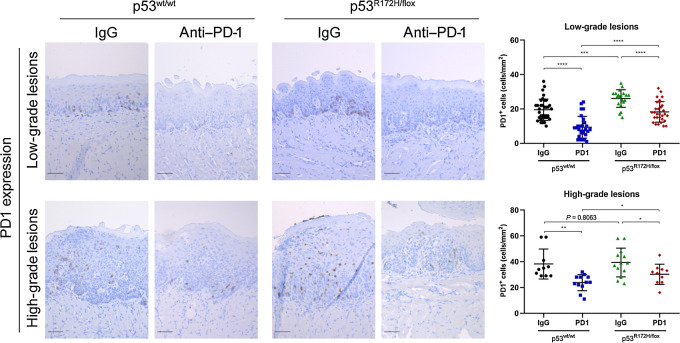

Foxp3 regulatory T-cell infiltration is altered in response to PD-1 blockage

To explore mechanisms of immunosuppression in OPLs, first we explored the levels of the immune-checkpoint inhibitor PD-1. Interestingly, after local delivery of anti–PD-1, we observed a significant reduction levels of PD-1 in low- and high-grade oral lesions; this was confirmed by immunostaining of PD-1 in oral lesions, in which high levels are detected in control-treated mice (Fig. 3). These results suggest that local delivery by hydrogels maintains anti–PD-1 antibody activity and the slow release by a single dose shows significant impact in the oral lesion microenvironment, which alters the infiltration of different immune cells.

Figure 3.

Local immunotherapy delivery reduced the expression of PD-1 levels in oral lesions. Immunotherapy significantly reduced the PD-1 levels in oral lesions of wild-type and mutant p53 mice. Immunostaining signal was defined as the number of positive cells per mm2. Right graphs: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Scale bar, 50 μm.

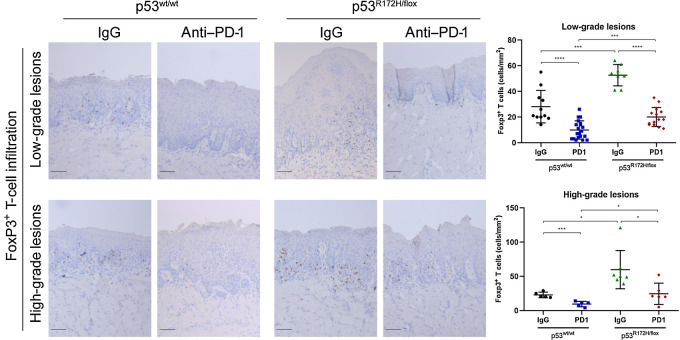

Regulatory T cells (Treg) are suppressors of antitumor responses by disrupting maturation of dendritic cells (DC) and preventing activation of CD4+ effector and CD8+ cytotoxic cells in the tumor microenvironment (38). To assess the role of PD-1 blockade on Treg infiltration in oral lesions, we conducted an IHC analysis with specific antibodies to Foxp3, a specific Treg marker. First, we noted that low-grade dysplasia has infiltration of Foxp3+ Tregs; nevertheless, it is significantly higher in premalignant lesions expressing mutant p53R172H, and strongly indicating that oncogenic activity of p53 might influence the environment to promote a higher infiltration of immune suppressor cells (Fig. 4). Similar results were observed in high-grade lesions (severe dysplasia and carcinoma). Furthermore, PD-1 gel treatment significantly reduced the number of Foxp3+ T cells in both low- and high-grade dysplasia, indicating that disruption of the PD-1/PD-L1 immunosuppression axis prevents infiltration of Foxp3+ cells.

Figure 4.

PD1 blockage reduced the infiltration of Foxp3+ T cells in low- and high-grade oral lesions. Mutant p53 mice showed a higher Foxp3+ T-cell infiltration compared with wild-type mice. PD-1 hydrogel reduced the numbers of positive Foxp3+ T cells in low- and high-grade oral lesions. Immunostaining signal was defined as the number of positive cells per mm2. Right graphs: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Scale bar, 50 μm.

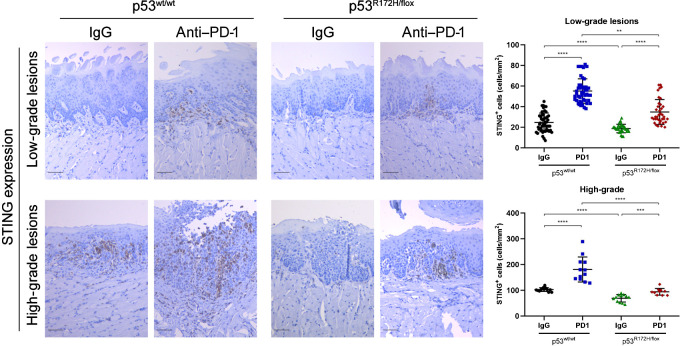

Local delivery of anti–PD-1 antibody restores STING expression and infiltration of CD11c DCs

The mechanism by which the immune system is alerted to the presence of a developing malignant lesions is by the classic “danger signals” such as type I interferons (IFN), which are induced early during tumor development and mediated by the cGAS–STING pathway (39–41). These cytokines activate DCs and promote induction of adaptive CD4 and CD8 T-cell antitumor immune responses (42). A defect or genetic alterations in the cGAS–STING pathway will impair interferon secretion preventing DC maturation, allowing transformation of premalignant cells to a tumorigenic phenotype. We analyzed the expression levels of STING by IHC, an important activator of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), which initiates the downstream signaling to produce type I interferons. In the IgG control–treated mice, the levels of STING were significantly lower in oral lesions expressing mutant p53R172H compared with wild-type p53. Interestingly, after PD-1 treatment, we observed a remarkable expression of STING in the low- and high-grade oral lesions of p53 wild-type mice (Fig. 5). In addition, we observed modest levels of STING staining in the oral dysplasia and carcinomas in mutant p53 mice, which was significantly lower than the intensity of STING staining when compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 5). The normal tongue epithelium exposed to 4NQO did not show any expression levels of STING; it was detected only in the OPLs (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 5.

Local delivery of anti–PD-1 increases STING protein levels in low- and high-grade lesions. Representative IHC images of STING expression in oral lesions. A, significant difference of STING expression was detected between untreated and PD-1 treated mice groups. Immunostaining signal was defined as the number of positive cells per mm2. Right graphs: **, P <0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Scale bar, 50 μm.

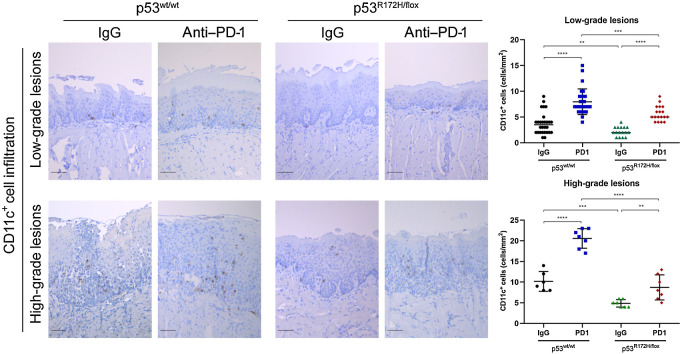

Furthermore, we stained oral lesions for CD11c, a specific DC marker. Strikingly, PD-1 inhibition was associated with a significantly higher degree of DC infiltrates in the low- and high-grade oral dysplasia of wild-type p53 mice when compared with control IgG-treated mice. Local delivery of the biomaterial loaded with PD-1 antibody was also beneficial in oral lesions from mutant p53R172H mice, but to a lesser extent than seen in p53 wt mice (Fig. 6). These data strongly suggest that mutant p53R172H disrupts the cGAS–STING pathways and is associated with a decreased infiltration of CD11c DCs.

Figure 6.

PD-1 blockage promoted recruitment of CD11c+ DCs into oral lesions of wild-type and mutant p53 mice. Representative IHC images of CD11c DCs in oral lesions. A significant difference of CD11+ cells was detected between untreated and PD1-treated mice groups. Immunostaining signal was defined as the number of positive cells per mm2. Right graphs: **, P <0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Discussion

We used a 4NQO oral carcinogenesis mouse model that allows the development of OPLs and oral cancers which consistently recapitulates histologic abnormalities observed in human carcinogenesis to examine the impact of a locally administered anti–PD-1 antibody-loaded hydrogel on the development of oral neoplastic lesions (31, 43). In our study, histopathologic analysis demonstrated that local delivery of loaded hydrogels with anti–PD-1 reduced the incidence of OPLs and carcinoma in p53 wild-type mice. Likewise, we observed a modest reduction of oral lesions in mutant p53R172H mice, suggesting that oncogenic p53 activates mechanisms of resistance to an inhibitor of the PD-1 immune checkpoint. Mice expressing mutant p53R172H have a higher incidence of high-grade lesions, strongly suggesting that oncogenic p53 has a role in immunosuppressive mechanisms that enable neoplastic progression.

In this study, we also examined the efficacy of local immunotherapy delivery by loading anti–PD-1 in nanofibrous biomaterials called MDP hydrogels that consist of polymerized multipeptide domain macromolecules. As previously reported, the MDP hydrogels mimic the native extracellular matrix of the body, and prolong the release of small-molecule drugs to achieve long-term drug delivery, and minimize side effects through localized and site-specific targeting of drug (36). We speculate that injection of this biomaterial into the tongue of mice generates an inflammatory response that might favor infiltration of immune cells, and together with the effect of the PD-1 blockage prevents Tregs to inactivate CD4 effector and CD8 cytotoxic T cells in the oral malignant lesions.

We observed an increased infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in low- and high-grade lesions after PD1 local blockade. We previously observed similar findings using the 4NQO carcinogen model in heterozygous p53 mice with loss of one p53 wt allele, with systemic administration (eight intraperitoneal injections) of anti–PD-1 antibodies, which led to an increased infiltration of activated T cells (22). Other studies using anti–PD-1 in mouse oral cancer models observed similar results in which PD1 blockade reduces OPL incidence and increase production of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen and lymph nodes and circulation levels (24); or showed a temporal increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in mice treated with anti–PD-1 in secondary lymph nodes (23).

In aggregate, these findings indicate that early genomic alteration in the p53 gene of oral epithelial cells promotes immunosuppressive pathways that disrupt antitumor immunity mechanisms, preventing the activation of adaptive immune response. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in the numbers of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes in oral dysplasia or carcinoma in mutant and wild-type p53 mice, suggesting that immunosuppressive mechanisms might qualitatively impair the effector and cytotoxic function of infiltrated T cells, rather than decrease their number.

Tregs (CD4+, CD25+, Foxp3+) negatively regulate tumor immunity, leading to tumor growth in mice through multiple suppressive mechanisms (44–46). The transcription factor Foxp3 is a phenotypic marker that correlates with tumor immunosuppression and worse prognosis (46, 47). Moreover, studies have shown that anti-CD25 immunotherapy can induce tumor rejection in mice and humans. In our study, we observed high infiltration of Foxp3+ Tregs in low-grade OPLs, with significantly higher numbers of Treg in oral lesions expressing mutant p53R172H, indicating that Tregs may be important immune cell population in early as well as later stages of oral neoplastic progression. Moreover, hydrogel/anti–PD-1 treatment dramatically reduced FoxP3+ Tregs in oral dysplasia and carcinoma, suggesting that local delivery and slow antibody release provide an efficient therapy to block PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. A recent study using an orthotopic oral cancer mouse model showed that a lower dose of intratumoral of immunotherapy showed similar effects as systemic delivery of a higher dose. Furthermore, intratumoral injection led to higher distribution of the antibody in the tumor and cervical lymph nodes, but less in the spleen, a secondary lymphoid organ. This approach enhanced the recruitment and infiltration lymphoid and myeloid immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, resulting in a significant tumor volume reduction. These results demonstrate that local delivery of immunotherapeutic agents might represent a novel approach to improve efficacy with favorable tumor response (48).

The elimination phase of cancer immunoediting is best described as an updated version of cancer immunosurveillance, in which the innate and adaptive immune systems work together to detect the presence of a developing tumor and destroy it before it becomes highly immunosuppressive. One of the mechanisms by which the immune system is alerted to the presence of a developing tumor is the production and secretion of type I interferons, which is regulated by the cGAS–STING pathway (39). In our study, OPLs with mutant p53R172H showed a dramatic decrease in expression of STING, a critical signaling molecule in the activation of interferon production. PD-1 blockade rescued the STING expression to a greater degree in lesions expressing wild-type p53 as compared with mice expressing oncogenic p53, providing direct evidence of the role of mutant p53R172H in OPL progression, and suggest that STING expression is relatively low in the early stages of oral cancer development and throughout cancer progression in mutant p53R172H mice.

Interestingly, a single dose of local immune-checkpoint inhibitory antibody delivery (anti–PD-1-hydrogel) also promotes a significantly higher number of DCs infiltrating into oral dysplasia, especially in wild-type p53 mice compared with mutant p53R172H mice. DCs have a critical role in linking innate and adaptive immunity. They have a key role in capturing and presenting antigens in the form of MHC II receptors to T cells, stimulating them to develop into effector T cells. In this role, DCs have a significant role in the tumor microenvironment, surrounding tumors and providing signals to other immune cells that stimulate or suppress T-cell activation. Tumor-tolerant DCs are one reason that nascent tumors can escape immune surveillance (49). DCs can also have prognostic value in treating patients. Potent DCs are required for a strong antitumor immune response after chemotherapy or radiation. There is a great degree of variability in the location and number of DCs in tumors (50). Studies have shown that tumors with DCs expressing low levels of CD86 and greater levels of IL10, generally are resistant to therapy and have a poor outcome (51). All of these reasons make DC stimulation or prevention of DC tolerance potential good strategies for tumor immune prevention.

Although ICIs can induce robust antitumor immune responses, their systemic delivery can induce cytokine release syndrome and abnormal liver function (52). To minimize off-tissue effects, biomaterials like multipeptide domain hydrogels are delivery systems designed for local and sustained release in vivo as demonstrated in this and other studies (25). Therefore, we have developed a novel method to locally deliver immunotherapy in a mouse oral cancer model using a novel biomaterial (hydrogel). The novel local anti–PD-1 delivery is relevant because a single dose using biomaterials that regulate a slow antibody release for weeks reduces the incidence of lesions to progress into carcinomas. We have demonstrated that a single PD-1 gel delivery shows similar therapeutic effect as eight doses of anti–PD-1 by systemic delivery. This approach could eliminate the need for repeated systemic administration of the anti–PD-1 immune-checkpoint inhibitory antibody. In clinical practice, local immunotherapy administration in patients with OPLs could potentially decrease the cost and reduce unnecessary and undesirable systemic side effects in patients with oral leukoplakia.

Authors' Disclosures

D.G. Leach reports grants from National Science Foundation during the conduct of the study; in addition, D.G. Leach has a patent for hydrogel delivery of sting immunotherapy for treatment of cancer, serial no. 62/520,834 pending. S. Young reports a patent for 62/950,718 pending and a patent for 62/520,834 pending. A.G. Sikora reports other support from SQZ, other support from Pelican, and other support from Tessa Therapeutics outside the submitted work. J.D. Hartgerink reports a patent 20200146975 pending. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Mrs. Nancy L. De Anda Research Foundation (to J.N. Myers) and NIH R21DE027794 (to J.D. Hartgerink, A.G. Sikora, and S. Young).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of publication fees. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Prevention Research Online (http://cancerprevres.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Contributions

Y. Shi: Formal analysis, validation, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft. T. Xie: Conceptualization, validation, investigation, and methodology. D.G. Leach: Resources, investigation, methodology, and writing–review and editing. B. Wang: Investigation and methodology. S. Young: Conceptualization, resources, writing–review and editing. A.A. Osman: Investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. A.G. Sikora: Conceptualization, investigation, writing–review and editing. X. Ren: Investigation. J.D. Hartgerink: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. J.N. Myers: Conceptualization, resources, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, investigation, writing–original draft, and project administration. R. Rangel: Conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, validation, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Vigneswaran N, Williams MD. Epidemiologic trends in head and neck cancer and aids in diagnosis. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2014;26:123–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Califano J, van der RP, Westra W, Nawroz H, Clayman G, Piantadosi S, et al. Genetic progression model for head and neck cancer: implications for field cancerization. Cancer Res 1996;56:2488–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Califano J, Westra WH, Meininger G, Corio R, Koch WM, Sidransky D. Genetic progression and clonal relationship of recurrent premalignant head and neck lesions. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:347–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ernani V, Saba NF. Oral cavity cancer: risk factors, pathology, and management. Oncology 2015;89:187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou G, Liu Z, Myers JN. TP53 mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and their impact on disease progression and treatment response. J Cell Biochem 2016;117:2682–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poeta ML, Manola J, Goldwasser MA, Forastiere A, Benoit N, Califano JA, et al. TP53 mutations and survival in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2552–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perrone F, Bossi P, Cortelazzi B, Locati L, Quattrone P, Pierotti MA, et al. TP53 mutations and pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant cisplatin and fluorouracil chemotherapy in resected oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:761–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neskey DM, Osman AA, Ow TJ, Katsonis P, McDonald T, Hicks SC, et al. Evolutionary action score of TP53 identifies high-risk mutations associated with decreased survival and increased distant metastases in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 2015;75:1527–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Osman AA, Neskey DM, Katsonis P, Patel AA, Ward AM, Hsu TK, et al. Evolutionary action score of tp53 coding variants is predictive of platinum response in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res 2015;75:1205–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sandulache VC, Michikawa C, Kataria P, Gleber-Netto FO, Bell D, Trivedi S, et al. High-risk TP53 mutations are associated with extranodal extension in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:1727–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ogmundsdottir HM, Bjornsson J, Holbrook WP. Role of TP53 in the progression of pre-malignant and malignant oral mucosal lesions. A follow-up study of 144 patients. J Oral Pathol Med 2009;38:565–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braakhuis BJ, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH. A genetic progression model of oral cancer: current evidence and clinical implications. J Oral Pathol Med 2004;33:317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yardimci G, Kutlubay Z, Engin B, Tuzun Y. Precancerous lesions of oral mucosa. World J Clin Cases 2014;2:866–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warnakulasuriya S, Ariyawardana A. Malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia: a systematic review of observational studies. J Oral Pathol Med 2016;45:155–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. William WN Jr., Papadimitrakopoulou V, Lee JJ, Mao L, Cohen EE, Lin HY, et al. Erlotinib and the risk of oral cancer: the erlotinib prevention of oral cancer (EPOC) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr., Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1856–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr., Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, et al. Nivolumab vs investigator's choice in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: 2-year long-term survival update of CheckMate 141 with analyses by tumor PD-L1 expression. Oral Oncol 2018;81:45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen EEW, Soulieres D, Le Tourneau C, Dinis J, Licitra L, Ahn MJ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019;393:156–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, Soulieres D, Tahara M, de Castro G Jr., et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019;394:1915–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Economopoulou P, Kotsantis I, Psyrri A. The promise of immunotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: combinatorial immunotherapy approaches. ESMO Open 2017;1:e000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Whiteside TL. Head and neck carcinoma immunotherapy: facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang J, Xie T, Wang B, William WN Jr., Heymach JV, El-Naggar AK, et al. PD-1 Blockade prevents the development and progression of carcinogen-induced oral premalignant lesions. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2017;10:684–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levingston CA, Young MRI. Local immune responsiveness of mice bearing premalignant oral lesions to pd-1 antibody treatment. Cancers (Basel) 2017;9:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Y, Li Q, Li X, Ma D, Fang J, Luo L, et al. Blockade of PD-1 effectively inhibits in vivo malignant transformation of oral mucosa. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1388484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Riley RS, June CA-O, Langer R, Mitchell MJ. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019;18:175–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leach DG, Young S, Hartgerink JD. Advances in immunotherapy delivery from implantable and injectable biomaterials. Acta Biomater 2019;88:15–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leach DG, Newton JM, Florez MA, Lopez-Silva TL, Jones AA, Young S, et al. Drug-mimicking nanofibrous peptide hydrogel for inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2019;5:6755–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leach DG, Dharmaraj N, Lopez-Silva TL, Venzor JR, Pogostin BH, Sikora AG, et al. Biomaterial-facilitated immunotherapy for established oral cancers. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2021;7:415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leach DG, Dharmaraj N, Piotrowski SL, Lopez-Silva TL, Lei YL, Sikora AG, et al. STINGel: controlled release of a cyclic dinucleotide for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2018;163:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moore AN, Hartgerink JA-O. Self-assembling multidomain peptide nanofibers for delivery of bioactive molecules and tissue regeneration. Acc Chem Res 2017;50:714–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kanojia D, Vaidya MM. 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide induced experimental oral carcinogenesis. Oral Oncol 2006;42:655–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caulin C, Nguyen T, Longley MA, Zhou Z, Wang X-J, Roop DR. Inducible activation of oncogenic K-ras results in tumor formation in the oral cavity. Cancer Res 2004;64:5054–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh Y-A, Liu G, Rao VA, Parant JM, et al. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell 2004;119:861–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dong H, Paramonov SE, Aulisa L, Bakota EL, Hartgerink JD. Self-assembly of multidomain peptides: balancing molecular frustration controls conformation and nanostructure. J Am Chem Soc 2007;129:12468–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aulisa L, Dong H, Hartgerink JD. Self-assembly of multidomain peptides: sequence variation allows control over cross-linking and viscoelasticity. Biomacromolecules 2009;10:2694–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li IC, Moore AN, Hartgerink JD. “Missing tooth” multidomain peptide nanofibers for delivery of small molecule drugs. Biomacromolecules 2016;17:2087–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lopez-Silva TL, Leach DG, Azares A, Li IC, Woodside DG, Hartgerink JD. Chemical functionality of multidomain peptide hydrogels governs early host immune response. Biomaterials 2020;231:119667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ohue Y, Nishikawa H. Regulatory T (Treg) cells in cancer: can treg cells be a new therapeutic target? Cancer Sci 2019;110:2080–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Woo S-R, Fuertes Mercedes B, Corrales L, Spranger S, Furdyna Michael J, Leung Michael YK, et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of immunogenic tumors. Immunity 2014;41:830–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ng KW, Marshall EA, Bell JC, Lam WL. cGAS–STING and cancer: dichotomous roles in tumor immunity and development. Trends Immunol 2018;39:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khoo LT, Chen L-Y. Role of the cGAS–STING pathway in cancer development and oncotherapeutic approaches. EMBO Rep 2018;19:e46935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Diamond MS, Kinder M, Matsushita H, Mashayekhi M, Dunn GP, Archambault JM, Lee H, et al. Type I interferon is selectively required by dendritic cells for immune rejection of tumors. J Exp Med 2011;208:1989–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hawkins BL, Heniford BW, Ackermann DM, Leonberger M, Martinez SA, Hendler FJ. 4NQO carcinogenesis: a mouse model of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 1994;16:424–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Greene M, Sehon AH, Sehon AH. Immunosuppressor T cells in tumor bearing host. Immunol Commun 1975;4:201–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2006;6:295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chaudhary B, Elkord E. Regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment and cancer progression: role and therapeutic targeting. Vaccines (Basel) 2016;4:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Facciabene A, Motz GT, Coukos G. T-regulatory cells: key players in tumor immune escape and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 2012;72:2162–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang ZA-O, Wu VH, Allevato MM, Gilardi M, He YA-O, Luis Callejas-Valera JA-O, et al. Syngeneic animal models of tobacco-associated oral cancer reveal the activity of in situ anti-CTLA-4. Nat Commun 2019;10:5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vicari AP, Caux C, Fau-Trinchieri G, Trinchieri G. Tumour escape from immune surveillance through dendritic cell inactivation. Semin Cancer Biol 2002;12:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hegmans JP, Aerts JG. Immunomodulation in cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2014;17:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zeid NA, Konrad Muller H. S100 positive dendritic cells in human lung tumors associated with cell differentiation and enhanced survival. Pathology 1993;25:338–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vonderheide RH, Khalil M, Stumacher MS, Bajor DL, Hutnick NA, Sullivan P, et al. Clinical activity and immune modulation in cancer patients treated with CP-870,893, a novel CD40 agonist monoclonal antibody. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:876–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]