Abstract

Objectives:

The literature on childhood-onset depression and future compromised vascular function is suggestive but limited. The objective of this study was to determine if arterial stiffness, a predictor of future cardiovascular disease (CVD), measured in young adulthood, is associated with childhood-onset depression.

Methods:

Cardiometabolic risk factors and pulse wave velocity (PWV), a measure of arterial stiffness, were cross-sectionally assessed in young adults with a history of childhood-onset depression (clinical diagnosis of major depressive episode or dysthymic disorder; N=294 probands; initially recruited via child mental health facilities across Hungary; mean age of first depressive episode=10.4 years), their never-depressed full biological siblings (N=269), and never-depressed controls (N=169). The mean ages of probands, siblings, and controls at the PWV visit were 25.6, 25.0, and 21.7 years, respectively, and 8.8% of the probands were in a current depressive episode.

Results:

Controlling for age, sex, age*sex, education, and family clusters, PWV (m/s) did not statistically differ across the groups (probands=7.01; siblings=6.98; controls=6.81). However, after adjusting for key covariates, there were several across-group differences in CVD risk factors: compared to controls, probands and siblings had higher diastolic blood pressure and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, probands had higher triglycerides, and siblings had higher body mass index (all p<0.05).

Conclusion:

We found limited evidence of an association between a history of childhood-onset depression and young adulthood arterial stiffness. However, our findings of elevated cardiovascular risk factors in those with childhood-onset depression suggest that pediatric depression may predispose to increased CVD risk later in life and warrants further investigation.

Keywords: childhood depression, arterial stiffness, major depressive episode, dysthymic disorder, cardiovascular risk

Introduction

Strong evidence indicates that major depressive disorder in middle-aged and older adults is linked to early and increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (1, 2). However, while depression that onsets very early in the lifespan, in childhood and adolescence, is also a common and disabling psychiatric condition worldwide (3), its association with early CVD is less established (4). Based on a review of existing evidence, the American Heart Association recently recommended that mood disorders, including major depressive disorder, among children and adolescents be considered a moderate-risk factor for early CVD and that having two or more cardiovascular risk factors may increase this pediatric group’s CVD risk from moderate to high (5). Furthermore, recent literature reviews suggest that depression and CVD may share a genetic vulnerability (2), and that molecular mechanisms, such as inflammation, also may link these two distinct clinical conditions (6) beyond traditional CVD risk factors.

Arterial stiffness, a measure of vascular aging and a strong predictor of future CVD events and mortality (7), has been extensively used as a surrogate marker of CVD risk in population-based studies of young adults (8, 9). Only a few studies, including from our group (10), have linked arterial stiffness to depression in adolescents and young adults (11–14). The literature on the association of childhood-onset depression with compromised vascular function is inconclusive (4) and is limited by small sample sizes (11, 12), questionable evaluation of depressive symptoms (10, 13–15), and cross-sectional study designs (12, 16).

We previously reported that, in adolescents with rigorously diagnosed childhood-onset depression (probands), rates of smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity were elevated compared to controls, independent of parental history of CVD (17). Furthermore, never-depressed siblings of probands, a group considered at high risk for depression (17, 18), had intermediate levels of these risk factors, suggesting that siblings may be at increased CVD risk compared to healthy, similarly aged, controls.

Building on our earlier longitudinal study (17), we sought to determine if childhood history of clinically diagnosed depression (major depressive episode or dysthymic disorder) would be cross-sectionally associated with premature arterial stiffness in young adulthood when study participants were, on average, 25 years old. We hypothesized that 1) probands with childhood-onset depression and their unaffected siblings would have stiffer arteries [i.e. higher pulse wave velocity (PWV), the gold standard measure of arterial stiffness (7)] in young adulthood compared to never-depressed controls; 2) unaffected siblings would exhibit an intermediate PWV phenotype, consistent with our prior finding of an intermediate CVD risk factor profile in this group (17); and 3) the relationship between childhood-onset depression and PWV would be independent of the overall burden of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, as assessed by the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) risk score. The PDAY score has previously been found to be elevated in adolescents with clinical depression (11) and to predict subclinical vascular disease in a population-based cohort of adolescents and young adults (19, 20).

Methods

Study Participants

The present study includes three groups of young adults: probands with a history of childhood-onset depression, their never-depressed full biological siblings, and healthy controls free of major psychiatric disorders. The probands and siblings were originally recruited between 1997 and 2006 as part of a genetic and subsequent longitudinal study of childhood depression (21, 22). Probands had to be 7- to 14- years of age at recruitment, were from 23 child mental health facilities across Hungary, and had to meet criteria for a major depressive episode (MDD) or dysthymic disorder diagnosis as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). At the time of original recruitment, probands were free of cognitive disabilities or major medical disorders and had at least one biological sibling between the ages of 7–17.9 years willing to participate. A subset of these probands and siblings who lived near three major universities and associated research sites– Medical University of Szeged, Semmelweis University in Budapest, and the Medical School at the University of Pécs, were contacted between 2010 and 2013 and invited to a follow-up visit (17). At this follow-up visit, healthy controls between the ages of 11–18 years, free of major psychiatric diagnoses, were recruited from public schools in the vicinity of the probands’ locations.

The current study (i.e., PWV visit), conducted from 2016 to 2019, entailed extensive CVD risk assessments, including arterial stiffness and involved the following groups: probands (N=298), never-depressed siblings of probands (N=275), and healthy controls (N=171). At the PWV visit, which was, on average, 15 years (range: 4–22) after initial MDD assessment, probands were, on average, 25 years old (range:18–32). Cardiometabolic risk factor and PWV data were obtained on 732 (98.4%) eligible participants (294 probands, 269 siblings, and 169 controls). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Pittsburgh and the participating Hungarian clinical research sites. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Data Collection

Anthropometric, cardiometabolic, and PWV data were collected during a morning clinic visit. Participants were asked to fast for at least eight hours and to refrain from caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco for one hour prior to a blood draw. Information on demographics, smoking status, physical activity, and medical history were obtained during a psychiatric interview at this visit.

Psychiatric Evaluation.

Psychiatric caseness was initially established during the original recruitment (1997–2006), when participants were children, using operational diagnostic criteria (21, 22) and semi-structured interviews including the Interview Schedule for Children and Adolescents (ISCA) (23). Diagnoses for the current study were derived via the semi-structured Interview Schedule for Young Adults – Follow-up Version (ISYA-FU), which collects information regarding symptoms since the participant’s last research evaluation, and is an age-appropriate modification of the ISCA (23). Participants were interviewed at all visits by trained clinicians. The interviewers also obtained sociodemographic, medical, and related information (see below) and determined the onset and offset dates of each episode of a participant’s major psychiatric disorders. For probands, the number of discrete episodes of depression were tallied (concurrent dysthymia and MDD were considered as one episode and MDD that remitted and was later followed by dysthymia were considered as two separate episodes). Percent of lifetime spent in depression was calculated by dividing the total duration of an individual’s depressive episodes (in days) by the age of the participant (in days) at study visit. Newly recruited siblings were administered an intake version of the ISYA, which collects information on lifetime and recent symptoms. Siblings who had a history of affective disorders or controls with any psychiatric disorders were not included in the present report.

Cardiovascular Risk Factors.

Waist circumference and body mass index (BMI) were measured using standard methodology. After a 5-minute rest, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP) and heart rate were assessed using an Omron M6 Blood Pressure Monitor with the participant in a sitting position; the mean of the three measurements was used for analysis.

Fasting blood draws were performed by a certified phlebotomist with the participant in a sitting position. Serum samples were processed, centrifuged, and then stored at −70ºC until analysis at the University Research Laboratory in Budapest, according to accepted international standards. Glucose, total cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were determined using standard enzymatic procedures: Bondar and Mead (1974 (24)), Allain (1974 (25)) and Bucolo (1973 (26)), respectively. HDL-cholesterol was measured using a two-reagent method with reagents obtained from Vital Diagnostics (Lincoln, RI). Previously reported intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV%) for these methods ranged from 1.8% to 3.5%; and inter-assay CV% from 2.6% to 6.7%. In 27 repeat samples from this study, we observed intra-assay CV% ranging from 2.9% to 4.8%. LDL cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald formula [LDL-c=(Cholesterol) – (HDL-c) –(Triglycerides/5)]; LDL-c was not calculated when triglycerides were >400 mg/dL (4.52 mmoles/L) (27).

Clinicians obtained participant’s medical history (diagnosis of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and medication use) and lifestyle behavior (past/current smoking, time spent on TV watching, sports) via a structured interview. Diabetes mellitus was considered present if the participant reported use of glucose lowering or insulin medication or had a fasting glucose >6.99 millimolar (mM). Hypertension was considered present if the participant reported use of BP lowering medication or had SBP ≥130 mmHg or DBP ≥85 mmHg. Extent of current smoking was based on the participant’s response to the question “How much do you smoke a day, on average?”. The possible responses were: none, less than ½ pack, ½ to 1 pack, 1 pack, 2 packs, and 3 or more packs, which were assigned values of 0, 0.25, 0.75, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 estimated packs/day, respectively. Participants also separately completed the 7-item version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), which has been validated in various countries (28).

The Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) risk score is a weighted score of cardiovascular risk factors specific to younger populations (age 15–34 years) (19). Points are assigned based on the following values for each risk factor: age in years 15–19=0, 20–24=5, 25–29=10, 30–34=15; gender male=0, female=−1; non-HDL-cholesterol <3.37 mM=0, 3.37–4.13 mM =2, 4.14–4.91 mM =4, 4.92–5.69 mM =6, ≥5.70 mM =8; HDL-cholesterol <1.04 mM =1, 1.04–1.54 mM =0, ≥1.55 mM =−1; smoking status non-smoker=0, smoker=1; BP normotensive=0, hypertensive=4; BMI (kg/m2) males ≤30=0, males >30=6, females ≤30=0, females >30=0; and diabetes status normoglycemic/nondiabetic=0, hyperglycemic/diabetic=5.

Arterial Stiffness.

Carotid-femoral PWV was measured using a non-invasive device (Complior Analyse, Alam Medical, Vincennes, France) in the supine position after a 10-minute rest (29). Simultaneous recordings of the pressure waveforms were obtained from the right common carotid and right femoral artery using mechanotransducers directly applied to the skin. PWV (m/s) was calculated as the distance traveled by the pressure wave between arterial sites of interest divided by the time delay (or transit time) between the respective waveforms. The distance between the sampling sites was measured over the surface of the body with a tape measure and calculated by the direct method (0.8 x direct measures between carotid and femoral arteries) (29). Three runs were performed and the mean used in analyses. All technicians were centrally trained and certified to perform research quality exams and technicians were re-certified annually. Intra-class correlations of 0.87–0.99 for between-technician comparisons and 0.98–0.99 for within-technician comparisons were attained.

Statistical Analyses

Group differences in demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, the PDAY score, and PWV were evaluated using ANCOVA and Chi-square test as appropriate. The non-independence of probands and siblings (i.e. family effects) were handled with population average methods [SURVEYFREQ, SURVEYREG, SURVEYLOGISTIC (SAS Institute Inc. 2016. Cary, NC:SAS Institute Inc.)]. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to assess group membership as a predictor of PWV controlling for main covariates (age, sex, education, and smoking) and family clusters (hypothesis 1) and additionally the PDAY score (hypothesis 3). The hypothesized linear group effect (hypothesis 2) was tested using a linear contrast. A sex by group and a smoking by group interaction term were included in separate regression modes to test whether the relationship between group membership and PWV varied by sex or smoking, respectively. The following additional variables known to be associated with depression or arterial stiffness were considered in multivariable models: LDL-cholesterol, heart rate, alcohol intake, and physical activity. Analyses including PDAY component variables on their own were analyzed as continuous variables; specifically, these were BMI, lipids, blood pressure and glucose. The PDAY score was treated as a continuous variable in models predicting PWV. Two sensitivity analyses were run; one excluding participants taking CVD related medication and a second limited to participants who overlapped in age at the PWV visit (age 20–23). In a secondary analysis within probands only the following exposures were evaluated in regard to PWV in separate models: 1) age at onset of 1st depressive episode, 2) # of depressive episodes and 3) % of lifetime in any depressive episodes. The site variable was forced in all models. Participants (n=15, 2%) with missing blood biomarker data were excluded from any analysis that used those variables.

Results

The mean ages of probands, siblings, and controls at the PWV visit were 25.6, 25.0, and 21.7 years, respectively (all group comparisons p<0.05 adjusted for family cluster; Table 1); age range across all participants was 18–44.6 years.

Table 1.

Study Population Characteristics at PWV Visit by Group Status (N=732)

| Proband (N=294) | Unaffected Sibling (N=269) | Control (N=169) | Group Effect | Pairwise Differences† (p<0.05) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, N (%) | 136 (46.3) | 146 (54.3) | 64 (37.9) | Χ2 =11.5** | SvC |

| Age, years | 25.6 (2.6) | 25.0 (5.0) | 21.7 (1.6) | F= 260.3*** | PvC, PvS, SvC |

| Education, years | 12.5 (2.6) | 12.9 (2.3) | 13.8 (1.7) | F=49.1*** | PvC, PvS, SvC |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.9 (5.5) | 25.2 (5.8) | 23.2 (3.7) | F=3.7* | SvC |

| Waist, cm | 84.5 (14.3) | 83.8 (13.7) | 79.8 (10.6) | F=2.8 | - |

| SBP, mmHg | 114 (13) | 113 (12) | 112 (12) | F=1.5 | - |

| DBP, mmHg | 74 (8) | 74 (8) | 70 (8) | F=3.9* | PvC, SvC |

| MAP, mmHg | 87.2 (9.1) | 86.6 (8.3) | 84.2 (8.2) | F=3.3* | PvC, SvC |

| Heart Rate, bpm | 74.2 (11.7) | 74.7 (11.0) | 73.0 (12.5) | F=0.2 | - |

| Lipids | |||||

| HDL-c, millimolar | 1.30 (0.35) | 1.32 (0.30) | 1.39 (0.33) | F=5.3** | PvC, SvC |

| Non-HDL-c, millimolar | 3.27 (0.85) | 3.12 (0.84) | 2.98 (0.79) | F=2.0 | - |

| LDL-c, millimolar | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.7) | F=2.5 | - |

| Triglycerides, millimolar | 1.14 (0.67) | 1.00 (0.57) | 0.93 (0.42) | F=6.0** | PvS, PvC |

| Glucose, millimolar | 5.0 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.8) | 5.0 (0.4) | F=1.4 | - |

| TV watching, hours/day | 1.2 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.4) | 0.6 (0.8) | F=5.3** | CvS |

| Sports, days/week | 1.6 (1.9) | 1.8 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.7) | F=2.9 | - |

| Smoking Status, N (%) | F=17.2*** | PvC, PvS, SvC | |||

| Never | 82 (27.9) | 119 (44.2) | 114 (67.5) | ||

| Past | 49 (16.7) | 43 (16.0) | 13 (7.7) | ||

| Current | 163 (55.4) | 107 (39.8) | 42 (24.9) | ||

| Smoking, packs/day | 0.53 (0.48) | 0.35 (0.41) | 0.16 (0.27) | F=19.9*** | PvC, PvS, SvC |

| Alcohol Use, N (%) | 7 (2.4) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | Χ2 =3.0 | - |

| Medication type | |||||

| For Diabetes Mellitus, N (%) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | Χ2 =0.4 | - |

| Psychotropic, N (%) | 16 (5.4) | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | Χ2 =14.4*** | PvC, PvS |

| Any Cardioactive‡, N (%) | 15 (5.1) | 7 (2.6) | 3 (1.8) | Χ2 =4.4 | - |

| PDAY Risk Score | 10.95 (4.59) | 9.09 (5.83) | 5.73 (3.49) | F=9.9*** | PvC, PvS |

| PWV, m/s | 7.01 (0.89) | 6.98 (0.87) | 6.81 (0.87) | F=0.2 | - |

Data are presented as mean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001 F-statistics adjusted for age, sex, age*sex, education, and family clusters except for age and sex (family clusters), and education (age, sex, age*sex, and family clusters). χ2 statistics adjusted for family clusters where possible (i.e. for rows with non-zero cells).

P=Proband, S=Siblings, C=Controls.

Any cardioactive medication included one unaffected sibling on lipid lowering medication; three probands, six siblings, and two controls on blood pressure lowering medication.

Probands had the onset of their first depressive episode on average at 10.4 years of age (SD=2.6 years). At the time of the PWV visit, 26 (8.8%) probands were in a current depressive episode: 18 met criteria for MDD, 5 for dysthymic disorder and 3 had both (double depression). One hundred and thirty-eight (46.9%) probands had one MDD episode, 33.0% had two episodes, and 20.0% had three or more episodes. Onset and offset dates were available for all episodes in 278 (95%) probands; median percent of life depressed was 6.8% and ranged from 0.2% to 68.0%.

By the PWV visit, 39 (14.5%) previously unaffected siblings were diagnosed with non-depressive disorders; 23 by the age of 14 and 13 in adolescence or adulthood. One (0.4%) had bipolar NOS episodes; 21 (7.8%), anxiety disorders; 9 (3.3%), externalizing/conduct disorders; 15 (5.6%), substance abuse or other major psychiatric disorder. In contrast 191 (65.0%) probands had non-depressive disorders in addition to MDD or dysthymic disorder (p<.001 for prevalence of non-depressive disorders in siblings versus probands).

A greater percentage of siblings were female (54.3%) as compared to controls (37.9%); male probands were younger than male siblings. Except for age, no sex by group differences were noted for cardiovascular risk factors.

PWV did not statistically differ by group status in unadjusted analyses, or when controlling for age, sex, age*sex, education, and family clusters (Table 1). There was no evidence of a linear trend in PWV across groups (F=0.06, p>0.8). Sex and smoking status did not moderate the relationship between PWV and group membership. When limiting analyses to probands and matched siblings, PWV did not differ between these two groups. Sensitivity analyses, excluding participants who were taking medication (n=25) and limited to participants with overlapping age (n=290) reached similar conclusions (data not shown). Neither age of onset, number of episodes, or percent of life depressed was associated with PWV, either unadjusted or adjusted for age, sex, age*sex, site and education (data not shown).

In unadjusted analyses, probands generally had a worse cardiovascular risk factor profile compared to siblings and controls, with siblings having an intermediate risk factor level; this included smoking status, education, lipids, BP, and the PDAY score (Table 1). After adjusting for age, sex, age*sex, and family cluster, this graded pattern only remained for education and smoking (for the latter also adjusting for education). Compared to controls, in adjusted analyses, probands and siblings had lower HDL-cholesterol and higher DBP, probands had higher triglycerides, and siblings had higher BMI (all p<0.05).

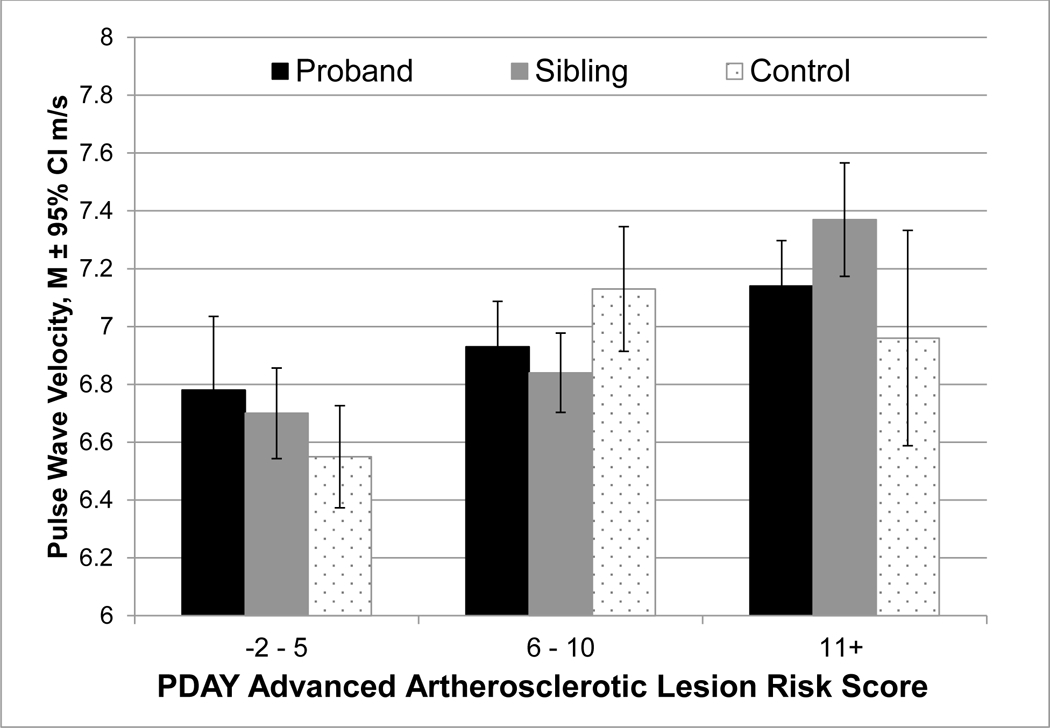

PDAY scores ranged from −2 to 24 (median=9) with higher PDAY scores in probands compared to siblings and controls, controlling for age, sex, age*sex, education, and family clusters (Table 1; p<0.001 for both comparisons). The PDAY score was associated with PWV overall (Pearson correlation=0.13, p=0.003) and across groups (Figure 1). In multiple regression analysis adjusting for family cluster, PDAY score components that were significantly associated with PWV were male sex, age, higher non-HDL-cholesterol and DBP, and lower HDL-cholesterol (data not shown).

Figure 1. Pulse Wave Velocity by PDAY Risk Score among Probands, Unaffected Siblings, and Controls.

PDAY=Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth

Discussion

We previously reported that adolescents with childhood-onset depression had elevated levels of behavioral CVD risk factors as compared to unaffected siblings and healthy controls (17). Specifically, they smoked more and were less physically active than siblings and controls, and were more likely to be obese than controls, even after accounting for parental history of CVD (17). The approximately 10-year follow-up of this unique pediatric sample with rigorously diagnosed childhood-onset depression, their never-depressed siblings, and heathy controls, extend these findings by having conducted a more complete cross-sectional assessment of cardiovascular risk in young adulthood. However, we found limited evidence that arterial stiffness, as measured via PWV, differs as a function of history of childhood-onset depression. The lack of across-group differences in PWV contrasts with our findings that probands and siblings had a worse cardiovascular risk factor burden than did controls, and that the PDAY score was associated with PWV across all groups.

The present study is one of the first to cross-sectionally examine, in a longitudinal cohort, the effects of clinically diagnosed depression in childhood on early vascular changes in young adults, before clinical events typically develop, and contributes to a sparse literature on this topic. In contrast to our findings, a small study (N=50) of 12- to 18- year olds from a general community in Australia reported that those with depression (evaluated via a diagnostic interview) had lower reactive hyperemia index and shorter pulse transit time (reflecting stiffer vessels) than age and sex matched healthy controls (11). However, that study used an indirect measure of arterial stiffness and did not control for traditional CVD risk factors. Yet, similar to our findings, in the Waloszek and colleagues’ study (11), adolescents with a depression disorder had elevated levels of triglycerides and higher PDAY scores as compared to non-depressed controls. In another small study of patients with depressive disorder recruited from outpatient psychiatric clinics (30 patients and 25 healthy controls; mean age=39.4 and 35.5 years, respectively), arterial stiffness was higher in patients receiving antidepressant treatment compared to healthy controls (13) but the participants were, on average, 10 years older than our study population. Finally, in another small cross-sectional study of young to midlife adults (N=62; mean age 33 years, range 20–46) with bipolar disorder, PWV was higher compared to age-based norms but only for the older half of the study population (>32 years old) (12). Collectively, these findings suggest that subclinical and clinical CVD may be more evident in older patients. Thus, one possible explanation for our null finding on PWV is that a longer latency period since onset of depression may be required for vascular dysfunction to manifest (4, 30). The cardiovascular effects of clinical depression in youth may be mediated by the short term and cumulative effects of behavioral (e.g. smoking and physical inactivity) and biological (e.g. hypertension and dyslipidemia) risk factors on the vasculature over a long-term course of illness (4, 31).

Findings are also mixed across studies that focused on depressive symptoms among youth with non-clinical depression (10, 14–16). Some studies have found that adolescents with depressive symptoms, as compared to adolescents without depressive symptoms, have stiffer arteries (10, 14) while other studies have not observed an association (15, 16). Notably, in a large longitudinal study of Australian youth (mean age=12 years), self-reported levels of depressive symptoms were not associated with arterial stiffness cross-sectionally, or longitudinally later during adolescence (15).

Another explanation for our null findings may be that the underlying pathology linking depression and CVD may be more atherosclerotic in nature, and that in young adulthood, early atherosclerotic changes may not be reflected as arterial stiffening (32). Indeed, we found that childhood-onset depression was associated with a worse lipid and smoking profile in young adulthood, two key etiological factors in atherosclerosis. Finally, although our findings that the number of episodes and percent of life spent in being depressed was not associated with PWV, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that our null PWV findings may be due to a Type II error resulting from our population potentially including probands with more mild and less severe depression.

We posited that unaffected siblings would be at higher risk for CVD than non-familial controls based on our prior findings (17) as well as evidence from others in the literature that CVD risk factors are increased in family members of individuals with depression (2, 33). For example, in a study of never depressed adolescents and young adults, having a parent with a positive history of depression was associated with higher blood pressure, insulin resistance, and arterial stiffness (33). In our study, siblings did not exhibit an intermediate phenotype for arterial stiffness, yet they did for some vascular risk factors, including the PDAY risk score, a measure of global cardiovascular risk factor burden (19). Although in adjusted analyses siblings were only at intermediate risk for smoking, they manifested a poorer cardiovascular risk profile than controls in terms of HDL-cholesterol, DBP, and BMI. Collectively, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the link between clinical depression and CVD may result from common risk factors or pathophysiology influenced by shared genetics (2, 6, 31).

There are several mechanisms by which a family history of depression may be associated with increased CVD susceptibility in unaffected siblings. These include 1) shared genetic risk and 2) shared environmental factors such as behavioral/lifestyle variables that may lead to downstream increased CVD risk factors (e.g., greater smoking rates and sedentary behavior which were demonstrated in our study population, Table 1) (2). A third mechanism is via pleiotropy. A review of the epidemiology literature by Penninx et al. (2) hypothesized that depression and CVD may share some genetic vulnerability. A more recent literature review exploring shared molecular mechanisms between depression and CVD suggests that depression and CVD may be two distinct clinical conditions linked by a shared mechanism, such as inflammation (6). Although our study design does not allow for direct testing of these hypotheses, our findings support the need for further research to elucidate potential mechanisms linking depression and CVD early in the lifespan.

One strength of our study is its unique sample of young adults with rigorously diagnosed childhood-onset depression, their never-depressed siblings, and healthy controls. The inclusion of the unaffected siblings has advantages relative to more standard case/control study designs; unaffected siblings serve as a proxy for similar genetic and familial exposures (compared to peers) and their inclusion allows us to examine an intermediate risk group. Other strengths are the inclusion of a reproducible and validated measure of arterial stiffness that is predictive of CVD events, and extensive assessments of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Limitations include a differential recruitment timetable for probands and controls, which may have introduced selection bias and a difference in age; however, sensitivity analyses limited to overlapping ages across groups did not alter results. Further, arterial stiffness was only measured once.

In conclusion, we did not find evidence of a link between a history of childhood-onset depression and arterial stiffness in young adulthood. Nevertheless, our prior and current findings of elevated cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents and young adults with a history of childhood-onset depression suggest that depression may predispose youth to increased CVD risk later in life and that enhanced cardiovascular risk prevention in this group may be warranted. This proposal is supported by the recent American Heart Association statement that major depressive disorder is a condition that may enhance cardiovascular risk in youth (5). Although children and adolescents do recover from their first depressive episode, a notable portion has recurrences as they grow into adulthood (34), which may contribute to future CVD risk. Thus, additional research is needed to determine which particular biobehavioral factors link these two major health conditions, and when in the life span the associations emerge and become detectable.

Highlights:

Pediatric depression was not associated with young adulthood arterial stiffness

Pediatric depression was associated with adverse young adulthood CVD risk factors

These risk factors include diastolic blood pressure, HDL-c and triglycerides

Childhood-onset depression may predispose youth to CVD risk later in life

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants and study staff including the University of Pittsburgh Ultrasound Research Lab for their contribution to this research.

Disclosures

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under award number R01 HL122648 (Kovacs and Matthews). Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interests to report

References

- 1.Nicholson A, Kuper H, Hemingway H. Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146 538 participants in 54 observational studies. European heart journal 2006;27(23):2763–74. Epub 2006/11/04. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penninx BW. Depression and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiological evidence on their linking mechanisms. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2017;74(Pt B):277–86. Epub 2016/07/28. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Mathers CD. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2011;377(9783):2093–102. Epub 2011/06/10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiedorowicz JG. Depression and cardiovascular disease: an update on how course of illness may influence risk. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014;16(10):492. Epub 2014/08/29. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0492-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein BI, Carnethon MR, Matthews KA, McIntyre RS, Miller GE, Raghuveer G, Stoney CM, Wasiak H, McCrindle BW, American Heart Association A, Hypertension, Obesity in Youth Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Y. Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder Predispose Youth to Accelerated Atherosclerosis and Early Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;132(10):965–86. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shao M, Lin X, Jiang D, Tian H, Xu Y, Wang L, Ji F, Zhou C, Song X, Zhuo C. Depression and cardiovascular disease: Shared molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Psychiatry Res 2020;285:112802. Epub 2020/02/10. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2010;55(13):1318–27. Epub 2010/03/27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhuiyan AR, Srinivasan SR, Chen W, Paul TK, Berenson GS. Correlates of vascular structure and function measures in asymptomatic young adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Atherosclerosis 2006;189(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira I, van de Laar RJ, Prins MH, Twisk JW, Stehouwer CD. Carotid stiffness in young adults: a life-course analysis of its early determinants: the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979) 2012;59(1):54–61. Epub 2011/11/10. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.110.156109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietz LJ, Matthews KA. Depressive symptoms and subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease in adolescents. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 2011;48(6):579–84. Epub 2011/05/18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waloszek JM, Byrne ML, Woods MJ, Nicholas CL, Bei B, Murray G, Raniti M, Allen NB, Trinder J. Early physiological markers of cardiovascular risk in community based adolescents with a depressive disorder. Journal of affective disorders 2015;175:403–10. Epub 2015/02/14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sodhi SK, Linder J, Chenard CA, Miller del D, Haynes WG, Fiedorowicz JG. Evidence for accelerated vascular aging in bipolar disorder. Journal of psychosomatic research 2012;73(3):175–9. Epub 2012/08/02. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanartas O, Sunbul M, Senkal Z, Durmus E, Kivrak T, Subasi N, Karaer G, Ergun S, Sari I, Sayar K. Increased arterial stiffness parameters in panic disorder patients in long term treatment period. Annals of general psychiatry 2016;15:14. Epub 2016/06/10. doi: 10.1186/s12991-016-0102-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujiwara H, Nakajima H, Inoue F, Kosaka K, Asano H, Yoshii K. Arterial stiffness in junior high school students: Longitudinal observations. Pediatrics international : official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society 2018;60(2):127–35. Epub 2017/12/13. doi: 10.1111/ped.13475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olive LS, Abhayaratna WP, Byrne D, Telford RM, Berk M, Telford RD. Depression, stress and vascular function from childhood to adolescence: A longitudinal investigation. General hospital psychiatry 2020;62:6–12. Epub 2019/11/19. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross AC, Kaizer AM, Ryder JR, Fox CK, Rudser KD, Dengel DR, Kelly AS. Relationships of Anxiety and Depression with Cardiovascular Health in Youth with Normal Weight to Severe Obesity. The Journal of pediatrics 2018;199:85–91. Epub 2018/05/15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rottenberg J, Yaroslavsky I, Carney RM, Freedland KE, George CJ, Baji I, Dochnal R, Gadoros J, Halas K, Kapornai K, Kiss E, Osvath V, Varga H, Vetro A, Kovacs M. The association between major depressive disorder in childhood and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in adolescence. Psychosomatic medicine 2014;76(2):122–7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao U, Chen LA. Characteristics, correlates, and outcomes of childhood and adolescent depressive disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009;11(1):45–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMahan CA, Gidding SS, Viikari JS, Juonala M, Kahonen M, Hutri-Kahonen N, Jokinen E, Taittonen L, Pietikainen M, McGill HC Jr., Raitakari OT. Association of Pathobiologic Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth risk score and 15-year change in risk score with carotid artery intima-media thickness in young adults (from the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study). The American journal of cardiology 2007;100(7):1124–9. Epub 2007/09/22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gidding SS, Rana JS, Prendergast C, McGill H, Carr JJ, Liu K, Colangelo LA, Loria CM, Lima J, Terry JG, Reis JP, McMahan CA. Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Risk Score in Young Adults Predicts Coronary Artery and Abdominal Aorta Calcium in Middle Age: The CARDIA Study. Circulation 2016;133(2):139–46. Epub 2016/03/31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamas Z, Kovacs M, Gentzler AL, Tepper P, Gadoros J, Kiss E, Kapornai K, Vetro A. The relations of temperament and emotion self-regulation with suicidal behaviors in a clinical sample of depressed children in Hungary. Journal of abnormal child psychology 2007;35(4):640–52. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiss E, Gentzler AM, George C, Kapornai K, Tamas Z, Kovacs M, Vetro A. Factors influencing mother-child reports of depressive symptoms and agreement among clinically referred depressed youngsters in Hungary. Journal of affective disorders 2007;100(1–3):143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherrill JT, Kovacs M. Interview schedule for children and adolescents (ISCA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;39(1):67–75. Epub 2000/01/19. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bondar RJ, Mead DC. Evaluation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides in the hexokinase method for determining glucose in serum. Clinical chemistry 1974;20(5):586–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CS, Richmond W, Fu PC. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clinical chemistry 1974;20(4):470–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucolo G, David H. Quantitative determination of serum triglycerides by the use of enzymes. Clinical chemistry 1973;19(5):476–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clinical chemistry 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2003;35(8):1381–95. Epub 2003/08/06. doi: 10.1249/01.Mss.0000078924.61453.Fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness C. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘establishing normal and reference values’. European heart journal 31(19):2338–50. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sternby NH, Fernandez-Britto JE, Nordet P. Pathobiological determinants of atherosclerosis in youth (PBDAY Study), 1986–96. Bull World Health Organ 1999;77(3):250–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaccarino V, Badimon L, Bremner JD, Cenko E, Cubedo J, Dorobantu M, Duncker DJ, Koller A, Manfrini O, Milicic D, Padro T, Pries AR, Quyyumi AA, Tousoulis D, Trifunovic D, Vasiljevic Z, de Wit C, Bugiardini R, Reviewers ESCSDG. Depression and coronary heart disease: 2018 position paper of the ESC working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation. European heart journal 2020;41(17):1687–96. Epub 2019/01/31. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McEniery CM, Yasmin, Hall IR, Qasem A, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR, Investigators A. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2005;46(9):1753–60. Epub 2005/11/01. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannie ZN, Williams C, Diesch J, Steptoe A, Leeson P, Cowen PJ. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile in young people at familial risk of depression. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science 2013;203(1):18–23. Epub 2013/05/25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovacs M, Obrosky S, George C. The course of major depressive disorder from childhood to young adulthood: Recovery and recurrence in a longitudinal observational study. Journal of affective disorders 2016;203:374–81. Epub 2016/06/28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]