Abstract

In this work, we establish that cocaine binding to the Fab fragment of a recombinant humanized anti-cocaine mAb (h2E2) can be directly and easily quantitated using simple and inexpensive absorption and fluorescence measurements, employing dyes typically used for differential scanning fluorimetry, DASPMI and SYPRO Orange. For concentrated samples of the Fab fragment, absorbance spectroscopy employing these dyes reveals the number of cocaine sites present, using either DASPMI (by measuring the increase in dye absorbance) or SYPRO Orange (by measuring the change in dye maximal absorbance wavelength). Interestingly, we observed that cocaine binding to the Fab fragment had a much different effect on the SYPRO Orange dye absorbance than previously reported for the intact h2E2 mAb, resulting in a large decrease in the total dye absorbance for the Fab fragment, in contrast to previous results with the intact h2E2 mAb. For dilute samples of Fab fragment, a dye fluorescence emission spectroscopy assay was developed to quantitate the number of cocaine (and other high affinity cocaine metabolites) binding sites via the ligand-induced decrease in fluorescence emission of both of these extrinsic dyes. The difference in the cocaine titrations for the high affinity (Kd < 30 nM) ligands, cocaine, cocaethylene and benzoyl ecgonine and the low affinity (Kd > 30 μM) ligands, norcocaine, ecgonine methyl ester, and ecgonine were obvious using this assay. These simple, direct, and inexpensive techniques should prove useful for evaluation of other small molecule antigen binding Fab fragments, enabling quantitation and rapid biochemical assessments necessary for determining Fab fragment suitability for in vivo uses and other assays and experiments.

Keywords: Monoclonal antibody, Fab fragment, cocaine antigen binding, absorption spectroscopy, DASPMI rotor dye, fluorescence spectroscopy

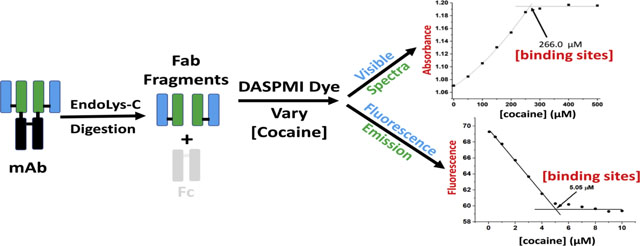

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are very useful experimental and diagnostic tools, as well as very important therapeutic drugs for treating many different diseases. These antibodies are large proteins of about 150 kDa, and consist of heavy and light chains, with the heavy chains forming the Fc constant region, and both the light chain and part of the heavy chain forming the two Fab (fragment antigen-binding) regions that bind the antigen/ligand specific for that antibody. There are several reasons for proteolytically cleaving the antibody to form the Fc and two Fab fragments, including separating the physiological functions of the Fc fragment from the antigen binding capability of the antibodies, as well as making the antigen binding part of the antibody smaller and thus more able to reach some antigen sites in bodily tissues. The latter reason is very important for some anti-cancer mAbs which have limited accessibility to their tumor targets because of their large size, which limits their distribution in the body. These properties increase the need for, and the utility of, Fab fragments of antibodies and other smaller antibody-like constructs such as nanobodies.

The FDA has not approved any small molecule antagonist-based pharmacotherapies for the treatment of cocaine use disorders (Vocci and Ling, 2005). However, a few vaccines and mAbs directed against cocaine have shown some promise for this purpose. Our laboratory developed a high affinity anti-cocaine mAb, h2E2, which also binds the active metabolite of cocaine, cocaethylene (CE), and one of the inactive metabolites, benzoyl ecgonine (BE), with high (nM) affinity (Norman et al., 2014; Wetzel et al., 2014; Wetzel et al., 2017; Kirley and Norman, 2021). We also developed several methodologies for the structural characterization of the mAb and its fragments (Kirley and Norman, 2015; Kirley et al., 2016a; Kirley et al., 2016b; Kirley and Norman, 2018). In addition, we have devised several ways to characterize the function (cocaine and cocaine metabolite binding) of the intact mAb and fragments, including ligand-induced intrinsic (tyrosine and tryptophan) mAb fluorescence quenching (Kirley and Norman, 2015) and extrinsic fluorescent dyes and differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) (Kirley et al., 2020) to quantitate ligand binding to this mAb and its Fab fragment. Interestingly, non-reducing SDS-PAGE can be used to qualitatively detect ligand-induced stabilization of the intact mAb and its ligand-binding fragments (Kirley and Norman, 2020a) and to monitor mAb Fab fragment sub-domain stabilization by cocaine and its metabolites (Kirley and Norman, 2020b).

We showed that two fluorescent dyes commonly used for measuring the denaturation of proteins with the differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) technique, DASPMI and SYPRO Orange, can be added directly to the intact, undiluted, formulated for clinical use h2E2 mAb and used to monitor cocaine and cocaine metabolite binding via changes observed using visible absorption spectroscopy of the dyes upon addition of these ligands (Kirley and Norman, 2021). However, no assessment of this dye absorbance technique was made for suitability for analysis of the Fab fragment that is derived from this antibody by proteolysis. Assays that rapidly and easily quantitate small molecule ligand (antigen) binding of generated Fab fragments at both high and low Fab fragment protein concentrations are very useful. Large amounts of Fab fragments needed for in vivo experiments can thus be assessed, as well as smaller amounts of Fab fragments generated for biochemical assays. In this study, we extended the use of two fluorescent dyes commonly employed for measuring the denaturation of proteins with the differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) technique, DASPMI and SYPRO Orange to the quantitative analysis of cocaine (and other high affinity ligands) binding to the Fab fragment of the anti-cocaine h2E2 mAb. We used both an adapted absorbance technique for high concentrations of the Fab fragment, and a novel fluorescence technique for low concentrations of the Fab fragment. In both cases, we report that the number of high affinity cocaine binding sites present can be quantitated directly and easily, allowing quantitative assessment of the binding ability of the produced Fab fragment in a simple, rapid, and inexpensive way. The experimental and therapeutic action, and therefore the “function” of this h2E2 anti-cocaine mAb and its Fab fragment is due to its high affinity binding of cocaine, thereby sequestering cocaine in the blood stream and out of the brain. Therefore, a rapid method to measure cocaine binding would be a useful adjunct to treatment utilizing this mAb. We report here that although the methods described do not allow measurement of ligand binding affinities (Kd values), and therefore do not discriminate between different high affinity ligands (cocaine, cocaethylene and benzoyl ecgonine), the data obtained is very useful to assess the ability of mAb Fab fragments (and other chemically or genetically modified h2E2 mAb proteins) to bind cocaine with high affinity, which is the sole therapeutic purpose and “function” of this anti-cocaine mAb. This is important to establish that proteolytic, chemical, genetic, or other potential modifications have not destroyed the ability of the mAb or mAb fragments to bind cocaine with high affinity. This is crucial for the usage and the interpretation of the experimental and therapeutic results obtained with these Fab fragments or modified antibodies in both in vivo and in vitro experiments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The generation, production, and purification of the h2E2 anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody was previously described (Norman et al., 2014), and the recombinant h2E2 mAb produced was used as supplied by the manufacturer, Catalent PharmaSolutions, Inc. (Madison, WI). The manufacturer supplied h2E2 mAb used in this study was approximately 20 mg/ml (19.94 mg/ml) of purified h2E2 mAb in its formulation buffer (10 mM histidine, 10% sucrose, pH=6.0, containing 0.01% polysorbate 80). The Fab fragment was generated in large quantities by scaling up a published proteolysis and Fab purification procedure (Kirley and Norman, 2015) 10-fold, yielding approximately 100 mg of pure Fab from 200 mg of pure h2E2 mAb digested with Endoproteinase Lys-C. The purity of the obtained Fab preparation was confirmed by SDS-PAGE, and the pure Fab fragment was quantified using the extinction coefficient for the Fab fragment calculated from its amino acid sequence (73,965 cm−1M−1, equivalent to an absorbance of 1.612 at 280 nm for a 1.0 mg/ml solution of Fab protein).

For all h2E2 mAb ligands used in this study, 10 mM ligand stock solutions were made in distilled water from solids obtained from Research Triangle Institute (RTI): CE, cocaethylene (RTI batch 9885-1022-125B); COC, cocaine (RTI batch 14201-12A); BE, benzoyl ecgonine (RTI batch 7474-1022-85A); NC, norcocaine (RTI batch 7778-1022-36G), EME, ecgonine methyl ester (RTI batch 8542-1022-8A); and EG, ecgonine (RTI batch 7593-1022-183A). SYPRO Orange 5000X dye stock was from Invitrogen/Life technologies, and the solid 4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide dye (4-Di-ASP iodide, DASPMI) was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Invitrogen/Life Technologies catalog # D-288). The 20 mM DASPMI stock dye solution was made by dissolution of the solid dye in dry DMSO (dye FW=366.24 g/mol). The SYPRO Orange and DASPMI DMSO dye stock solutions were stored light protected at −20°C.

2.2. Methods

The absorbance scans and measurements were performed at 21°C using a micro 1.0 cm path length quartz cell (100 μL sample volume) in a Beckman DU 800 spectrophotometer, scanning from 650 nm to 350 nm in 0.5 nm increments. All absorbance samples contained a final concentration of 11.6 mg/ml (259.2 μM) Fab fragment in 20 mM MOPS, 40 mM NaCl, pH=7.4, with varying concentrations (0–500 μM) of cocaine or cocaine metabolites, containing either a 1:500 dilution of stock commercial 5000X SYPRO Orange dye, or 25 μM of DASPMI dye. For the DASPMI dye measurements, the maximum dye absorbance at 448 nm was normalized by the dye absorbance at the isosbestic wavelength, 478 nm, to correct for any small differences in concentrations due to pipetting variabilities (no isosbestic wavelength was observed for the SYPRO Orange dye). Cocaine or other ligands were added to the solutions of Fab fragment, and the samples mixed and allowed to incubate at 22°C for at least 5 minutes before the absorbance spectra were measured, since no changes in results were observed using longer pre-measurement incubation times.

The fluorescence of diluted Fab fragment (5.0 μM Fab) or diluted intact h2E2 mAb (2.5 μM mAb, both containing 5.0 μM of cocaine binding sites) was measured in 20 mM MOPS, 200 mM NaCl, pH=7.4 at 21°C using a micro (0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) fluorescence quartz cell (200 μL sample volume, in a 4UV5X5X33 cuvette in a A23 cuvette mount (the cuvette and cuvette mount were purchased from fireflysci.com) in a Hitachi F-2000 fluorescence spectrophotometer. For the Fab/DASPMI dye measurements, the dye (10 μM) was excited at 460 nm and the emission quantitated at 610 nm, while for the Fab/SYPRO Orange dye measurements, the dye (a 1:1000 dilution of the 5000X commercial stock solution) was excited at 480 nm and the emission quantitated at 610 nm. Cocaine or other ligands were added to the solutions of Fab fragment or intact mAb, and the samples mixed and allowed to incubate at 22°C for at least 5 minutes before the fluorescence was measured, since no changes in results were observed using longer pre-measurement incubation times.

The choice of dye concentrations utilized in this study was broadly based on the absolute absorbances obtained with these dyes at the concentrations used in the absorbance assays - resulting in an absorbance maximum measured of just under 1.0 for the DASPMI dye, and maximal absorbances around 0.25 for Sypro Orange (see Figure 2A). We chose not to use a higher concentration of Sypro Orange dye than a 1:500 dilution of the commercial stock, since that was shown to be sufficient for these experiments (the Sypro Orange dye solution concentration is proprietary, so it is not possible to know the molar ratio of dye to protein for the Sypro orange dye experiments). Lower concentrations of Sypro Orange would result in too low absorbances for the dye at saturating concentrations of cocaine for accurate assessment. Regarding the DASPMI dye, the concentration used for the fluorescence assays was assessed from 10–100 μM, with very similar results in this dye concentration range. The concentration of DASPMI dye used to generate the fluorescence data in Figures 3 and 4 was 10 μM, which maintained a 2X molar excess of DASPMI dye over moles of cocaine binding sites present, to ensure that there was sufficient dye to occupy the reporting binding site(s) for the dye on the protein.

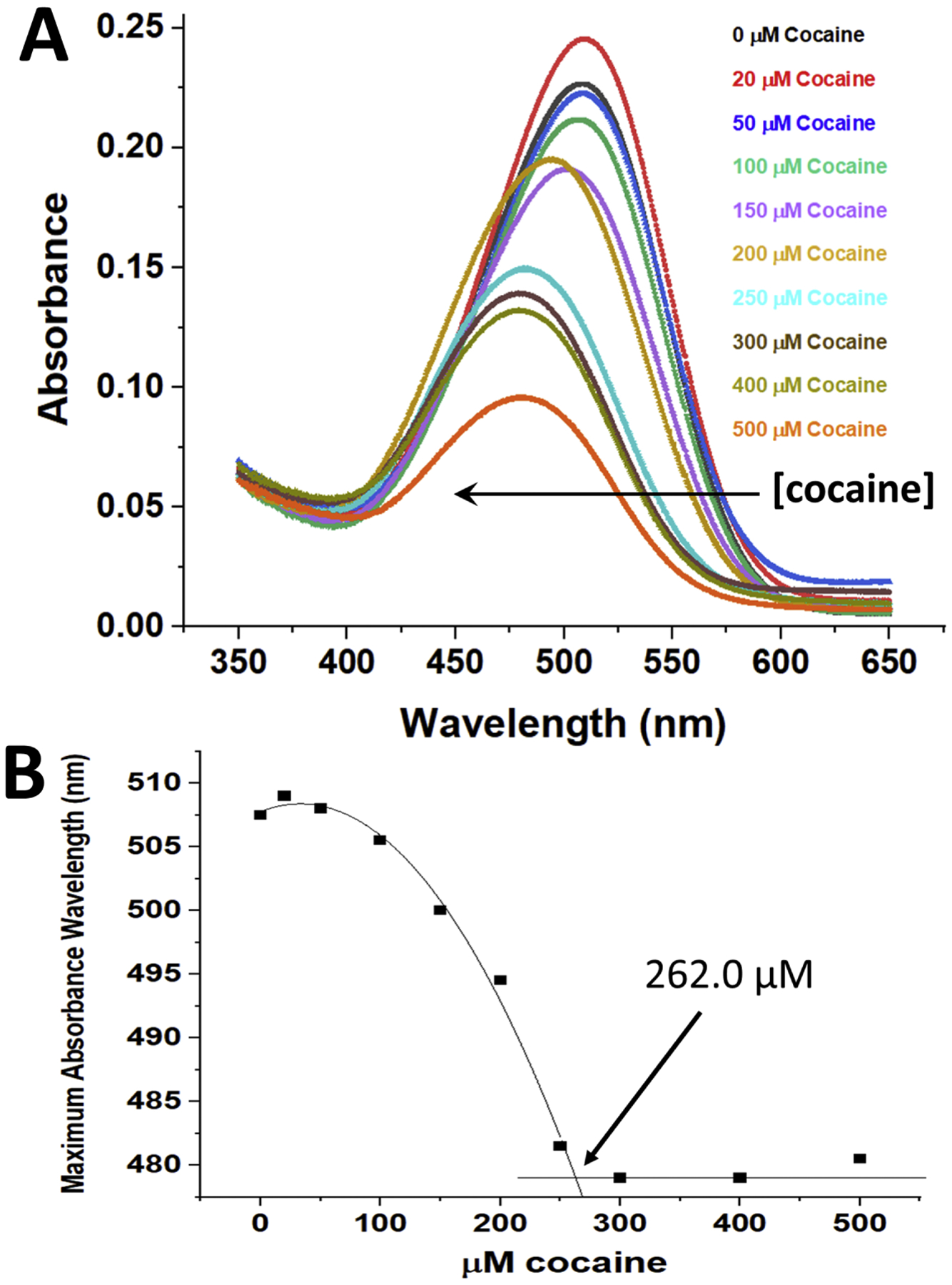

Figure 2. The effect of cocaine binding (0–500 μM) at 21°C on the absorbance of a 1:500 dilution of SYPRO Orange dye in the presence of 11.6 mg/ml Fab fragment (259.2 μM of cocaine binding sites).

Panel A - The Fab fragment in buffer plus SYPRO Orange dye was incubated with varying concentrations of cocaine, and the absorbance spectra of the samples recorded from 650 – 350 nm, blanked versus distilled water. An arrow parallel to the X-axis indicates the decrease in the dye absorbance wavelength maximum observed with increasing concentrations of added cocaine (plotted and quantitated in Figure 2B). Panel B – The data shown in Panel A were used to show the dependence of the maximum absorbance wavelength of the dye on cocaine concentration. A straight line fit to data in Figure 1B at concentrations above the stoichiometric level and a second order polynomial fit to the data below the stoichiometric level of cocaine were calculated, and the intersection of these fits yielded the experimentally determined concentration of functional cocaine binding sites (262.0 μM).

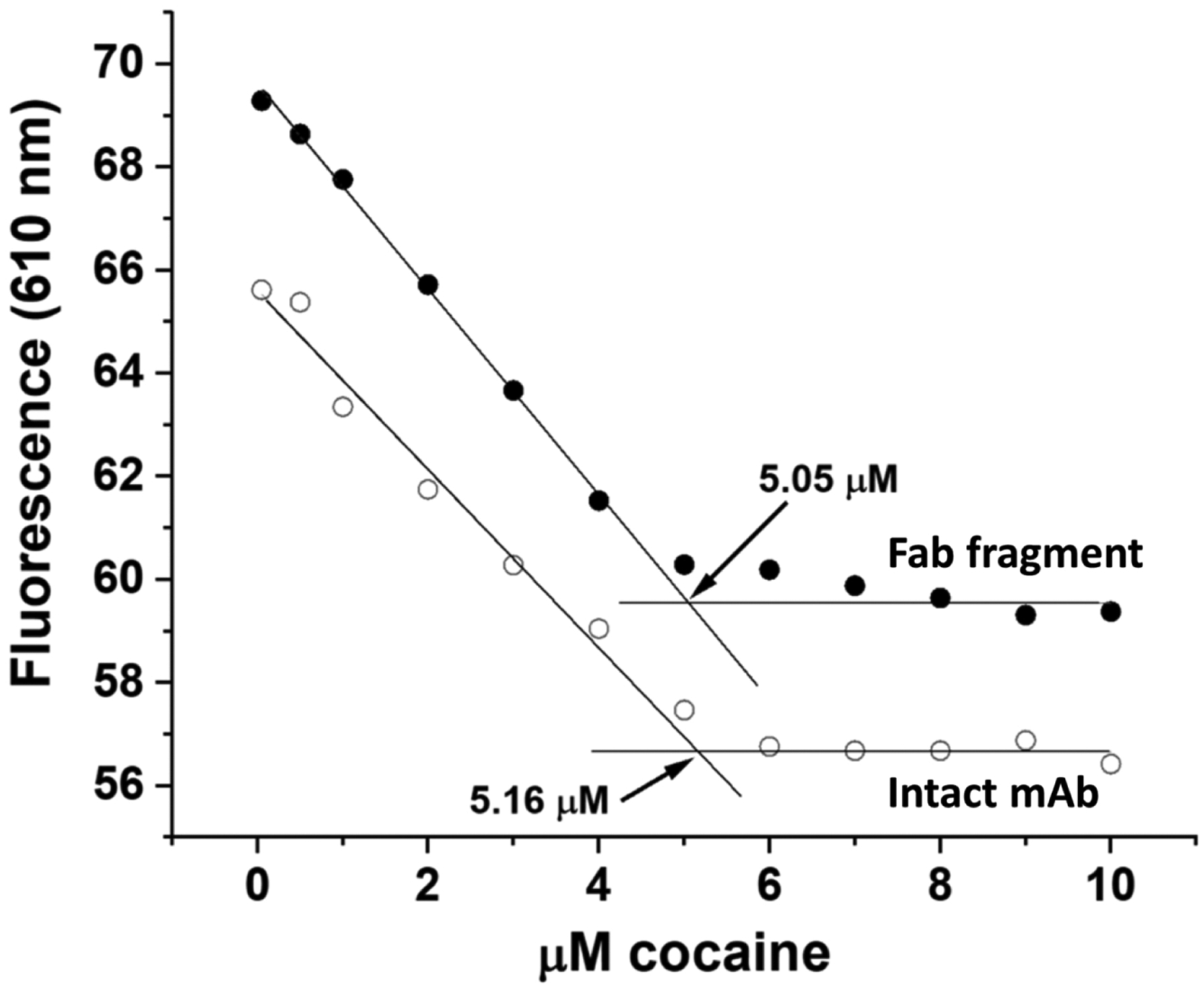

Figure 3. Fluorescence cocaine titrations of the Fab fragment and the intact h2E2 mAb utilizing 10 μM DASPMI dye at 21°C.

Either 5.0 μM Fab fragment (filled circles) or 2.5 μM intact mAb (open circles) were titrated with 0 – 10 μM cocaine and the fluorescence emission at 610 nm (excitation at 460 nm) was plotted. Straight line fitting was done to data in Figure 3B at concentrations above the stoichiometric level (slope fixed at 0) and below the stoichiometric level, and the intersection of these straight line fits yielded the experimentally determined concentrations of functional cocaine binding sites (in this experiment, 5.05 μM for the Fab fragment and 5.16 μM for the intact mAb).

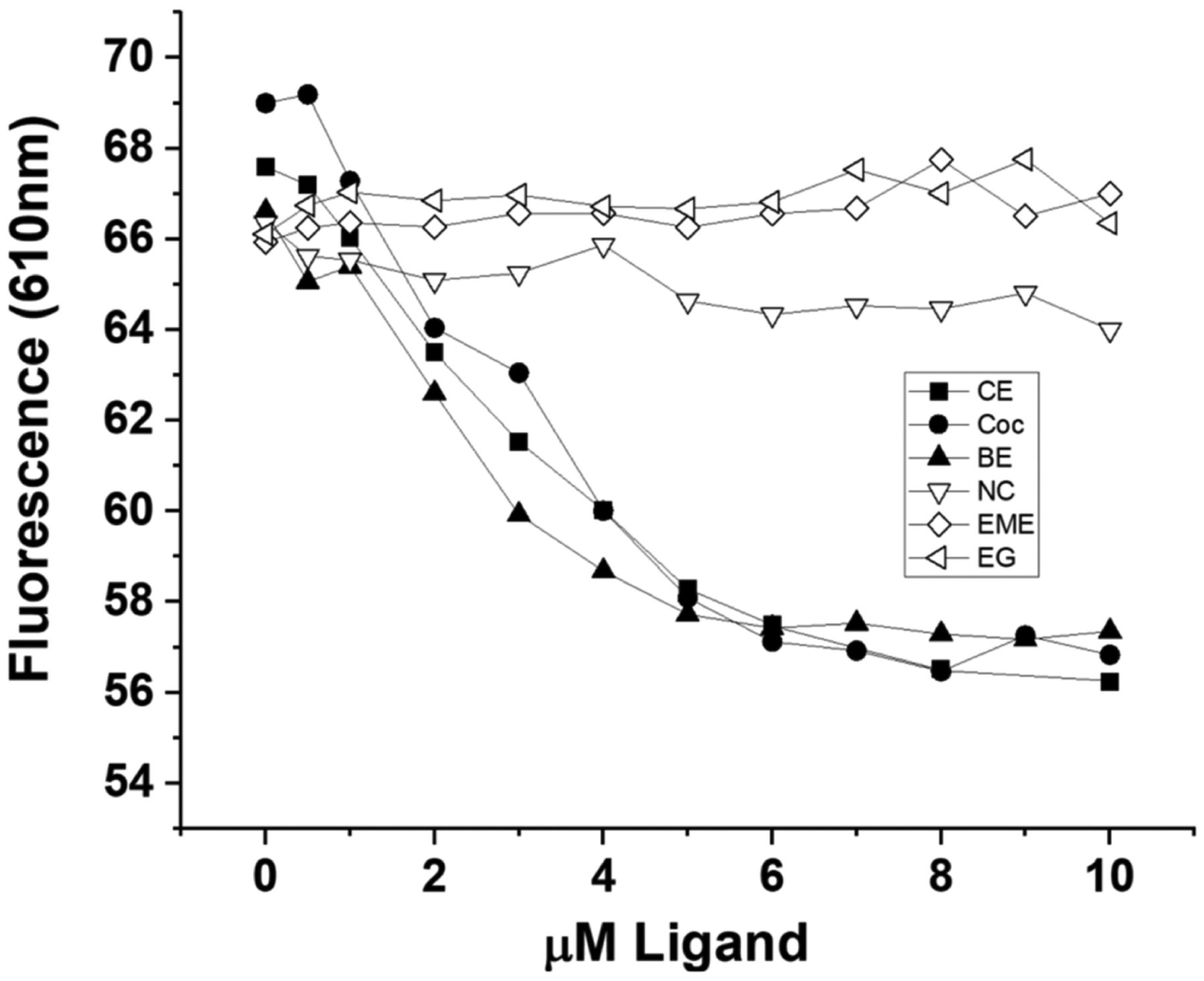

Figure 4. Fluorescence titrations of the Fab fragment with cocaine and 5 cocaine metabolites utilizing 10 μM DASPMI dye at 21°C.

5.0 μM Fab fragment was titrated with 0 – 10 μM cocaine or cocaine metabolite and the dye fluorescence emission at 610 nm (excitation at 460 nm) was plotted. Filled symbols are data for the high affinity ligands, while the open symbols are data for the low affinity ligands. The higher affinity ligands, cocaethylene (CE), cocaine (Coc), and benzoylecgonine (BE) caused a dose dependent decrease in DASPMI dye fluorescence, while the lower affinity ligands, norcocaine (NC), ecgonine methyl ester (EME) and ecgonine (EG), gave rise to no dose-dependent change in dye fluorescence in this ligand concentration range.

Control experiments demonstrated no change in either DASPMI or Sypro Orange dye absorbance or fluorescence under these conditions when adding the concentrations of cocaine used in this study in the absence of the anti-cocaine mAb and its Fab fragment. The choice of linear vs polynomial fits used to analyze the data in the Figures was an empirical one, with the data being fit to several functions to determine which one described the experimental data the best. The straight line slope was forced to zero in the saturated phase since all the experiments performed indicated that there was no further change in dye absorbance (i.e., absorbance amplitude for DASPMI dye, and maximum absorbance wavelength for Sypro Orange dye) or fluorescence amplitude (both dyes) after all the cocaine binding sites were fully occupied. This was confirmed by increasing the maximal concentration of cocaine used in the fluorescence assay from 10 μM to 500 μM – in the absence of protein, the slope of the DASPMI fluorescence intensity vs [cocaine] after saturation of the cocaine binding sites remained at zero even up to this very high cocaine concentration. However, we did also perform linear regression fitting of the data from the saturating concentrations of cocaine allowing the slope of the fitted straight line to vary, and obtained a nearly identical calculated number of binding sites in these experiments.

3. Results

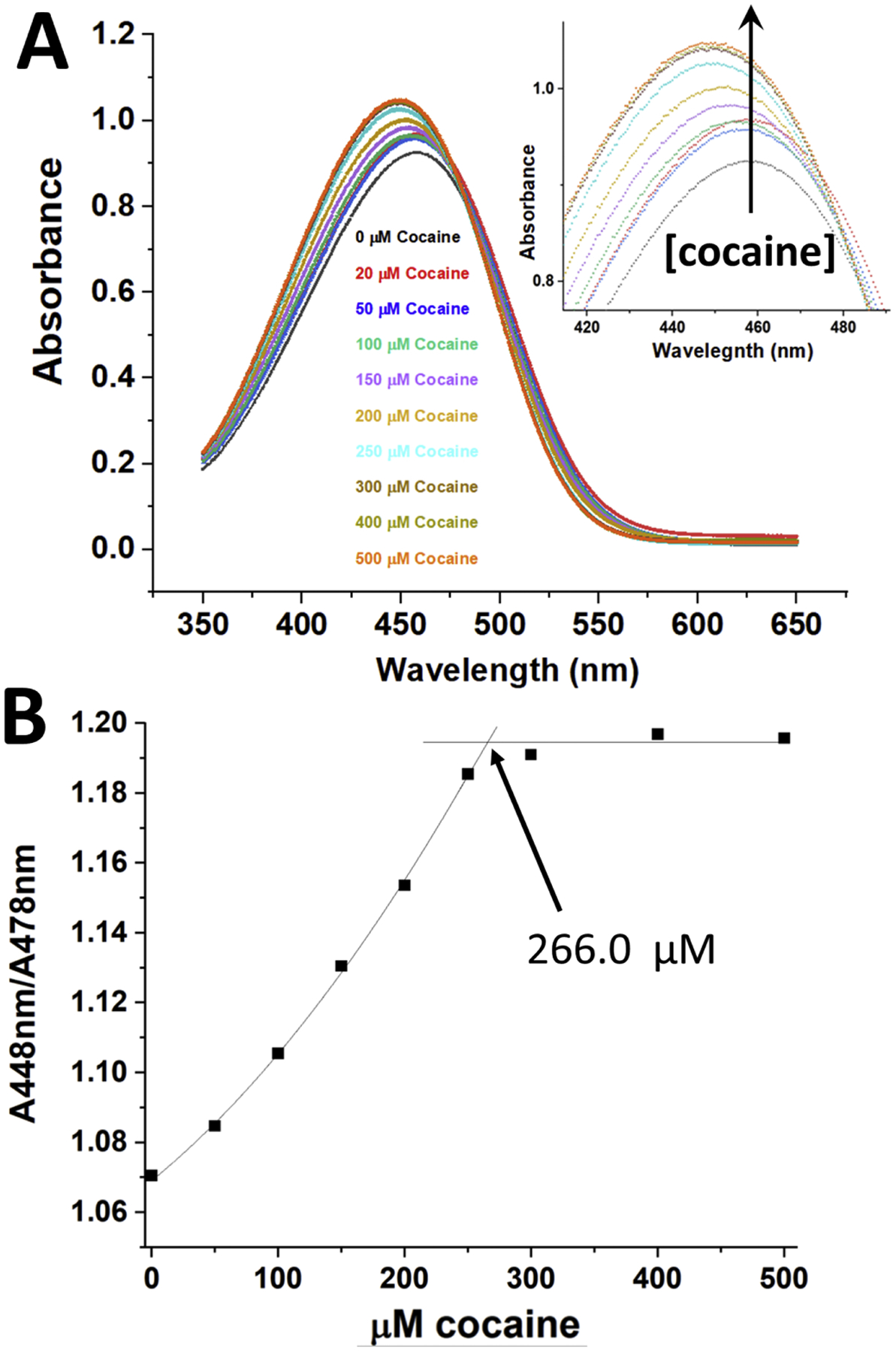

Figure 1A shows the effect of different concentrations of cocaine (0–500 μM) on the absorbance of 25 μM DASPMI dye in the presence of 11.6 mg/ml Fab (equivalent to 259.2 μM Fab/cocaine binding sites, assuming all Fab molecules are functional). A small decrease in absorbance wavelength maximum was observed with increasing concentrations of cocaine, in addition to an increase in the absorption of the DASPMI dye at 448 nm (see Figure 1A inset). Figure 1B shows the relationship of the absorbance at the wavelength maximum for the Fab fragment saturated with cocaine, at 448 nm (normalized for small pipetting variations by dividing by the isosbestic point absorbance at 478 nm) for the data in Figure 1A. A straight line fit to the data in Figure 1B at concentrations above the stoichiometric level (300–500 μM cocaine, with zero slope) and a second order polynomial fit to the data below the stoichiometric level of cocaine (0–250 μM) were calculated, and the intersection of these extrapolated fits yields the experimentally determined concentration of functional Fab cocaine binding sites, which for this experiment was 266.0 μM. This is very close to the calculated number of theoretical binding sites based on absorbance (280 nm) and calculated concentration of Fab fragment (259.2 μM). Thus, this assay indicates that all (266.0/259.2 μM, 102.6%) the binding sites on the Fab fragment are functional (i.e., bind cocaine).

Figure 1. The effect of cocaine binding (0–500 μM) at 21°C on the absorbance of 25 μM DASPMI dye in the presence of 11.6 mg/ml Fab fragment (259.2 μM of cocaine binding sites).

Panel A - The Fab fragment in buffer plus DASPMI dye was incubated with varying concentrations of cocaine, and the absorbance spectra of the samples recorded from 650 – 350 nm, blanked versus distilled water. The inset shows an expansion of the region of spectral change for the different concentrations of cocaine. An arrow perpendicular to the X-axis indicates the direction of increasing cocaine concentrations added. Panel B – The data shown in Panel A were used to generate this plot, showing the dependence of the absorbance at the wavelength maximum for the mAb saturated with cocaine (448 nm) divided by (normalized to) the isosbestic point absorbance at 478 nm. A straight line fit to data in Figure 1B at concentrations above the stoichiometric level and a second order polynomial fit to the data below the stoichiometric level of cocaine were calculated, and the intersection of these fits yielded the experimentally determined concentration of functional cocaine binding sites (266.0 μM).

Figure 2A shows the effect of different concentrations of cocaine (0–500 μM) on the absorbance of a 1:500 dilution of the SYPRO Orange dye in the presence of 11.6 mg/ml Fab (equivalent to 259.2 μM Fab and cocaine binding sites, if all Fab molecules are functional). A large decrease in absorbance with higher concentrations of cocaine is noted for the Fab fragment, which was not observed when essentially the same experiment was performed with the intact h2E2 mAb ((Kirley and Norman, 2021), see Figure 2A). In addition, a decrease in the SYPRO Orange absorbance wavelength maximum is observed (which was also observed with the intact mAb (Kirley and Norman, 2021)), but consistent with previous results using the intact mAb, no isosbestic point wavelength is present for the SYPRO Orange dye, and no linear or monotonic increase or decrease at a single wavelength is obvious, unlike the DASPMI dye (Figure 1). Figure 2B shows the relationship of the maximum absorbance wavelength observed for the SYPRO Orange dye to the cocaine concentration added (0–500 μM). A straight line fit to the data in Figure 2B at concentrations above the stoichiometric level (300–500 μM cocaine, with zero slope) and a second order polynomial fit to data below the stoichiometric level of cocaine (0–250 μM) were calculated, and the intersection of these fits yields the experimentally determined concentration of functional cocaine binding sites from this SYPRO Orange data, which was calculated to be 262.0 μM, compared to the 259.2 μM theoretical concentration of Fab binding sites. Thus, this assay also indicates that all (262.0/259.2 μM, 101.1%) the binding sites on the Fab fragment bind cocaine.

It is desirable to have a similar simple assay that can quantitate ligand binding for much lower concentrations of Fab fragment, so preliminary experiments were performed using dye fluorescence for both DASPMI and SYPRO Orange dyes, as well as using 0.2 ml sample volumes in both 96 well plates and in small volume fluorescence cuvettes (0.5 × 0.5 cm quartz mini cuvettes). It was found that the data obtained using the SYPRO Orange dye tended to have more scatter, as did the data obtained using either dye and 96 well plates. Multiple types of 96 well plates, including black plates with clear bottoms, were utilized and measurement of the dye fluorescence emission from both the top and bottom of these plates were evaluated, but no improvement in data variability was observed in the plate assays (data not shown). Therefore, the experiments shown in Figures 3 and 4 were performed on 200 μL samples, using the DASPMI dye and the mini cuvettes.

The number of cocaine binding sites was quantitated by fluorescence measurements using the DASPMI dye, for both the Fab fragment, and the intact h2E2 mAb, as shown in Figure 3. The number of cocaine binding sites using 5.0 μM Fab or 2.5 μM intact mAb (both should have 5.0 μM cocaine binding sites, if fully functional) were determined as shown in Figure 3 by the intersection of 2 straight line fits, using data below the stoichiometric amount (0–4 μM cocaine) and data above the stoichiometric amount of cocaine (7–10 μM cocaine, slope set to zero), as shown in the figure. The data shown in Figure 3 is representative of 4 such sets of cocaine titrations, yielding calculated numbers of cocaine binding sites of 5.29 ± 0.20 μM for the Fab data, and 4.91 ± 0.31 μM for the intact mAb data (mean ± standard deviations), demonstrating that both the Fab fragment and the starting, intact h2E2 anti-cocaine mAb are fully functional in term of their antigen (cocaine) binding capabilities, as measured by this novel fluorescence assay.

We also evaluated this fluorescence method for the ability to measure binding of high affinity (cocaethylene (CE), cocaine (Coc), and benzoylecgonine (BE)) ligands (approximate Kds of 1, 4 and 20 nM, respectively (Kirley and Norman, 2015)) versus much lower affinity ligands (norcocaine (NC), ecgonine methyl ester (EME) and ecgonine (EG), which all have high μM Kds (Kirley et al., 2020)). Thus, titration of 5.0 μM Fab with 0–10 μM of these 6 ligands is shown in Figure 4. The high affinity ligands (filled symbols in the figure) all caused a very similar dose-dependent decrease in fluorescence emission of the DASPMI dye, while the 3 low affinity ligands unsurprisingly showed essentially no concentration-dependent change in dye fluorescence up to 10 μM ligand (which is substantially below the Kds for these low affinity ligands). We note that norcocaine has the highest affinity of these 3 low affinity ligands (about 55 μM (Kirley et al., 2020)), and does give slightly different results than the other 2 very low affinity ligands.

4. Discussion

The h2E2 humanized anti-cocaine mAb we have developed for prophylactic treatment of cocaine use disorders is in late stage pre-clinical development. We are also evaluating the Fab fragment of this mAb for its possible efficacy in treating acute cocaine overdose. Thus, there is a need to generate large amounts of functionally active Fab fragments for in vivo studies, as well as for protein structural studies, such as crystallization of the Fab fragment for X-ray crystal structure studies (Tan et al., 2019). We have experience measuring the binding of cocaine and its metabolites both quantitively and qualitatively to this mAb and to its fragments, using a variety of methodologies (Kirley and Norman, 2015; Wetzel et al., 2017; Kirley and Norman, 2018; Kirley and Norman, 2020b; Kirley and Norman, 2020a; Kirley et al., 2020). In this study, we utilized the ligand-induced changes in both the visible absorbance and the fluorescence emission of two dyes commonly used in differential scanning fluorimetry assays to monitor protein unfolding, DASPMI (a rotor dye (Wong et al., 2016)) and SYPRO Orange (a solvatochromatic dye (Layton and Hellinga, 2010; Layton and Hellinga, 2011; Shi et al., 2013)), to quantitatively measure the number of functional ligand binding sites in the Fab fragment generated by proteolysis of the h2E2 mAb with Endoproteinase Lys-C.

The absorbance of the DASPMI dye in the presence of a high concentration of Fab fragment increases when cocaine or a cocaine metabolite is added, and this increase in absorbance is a function of the number of ligand binding sites occupied, until are sites are fully occupied with ligand (Figure 1). This may be due to the interconversion of two dye-Fab species by the binding of cocaine, since an isosbestic point is observed in the absorbance spectra at 478 nm. This allows accurate determination of the concentration of binding sites present, permitting assessment of the functionality of the Fab fragment directly as it is purified in concentrated form, using simple and widely available absorption spectroscopy.

In contrast, the absorbance of the SYPRO Orange dye does not undergo a monotonic change in absorption at a given wavelength, but rather a spectral shift, from ≈ 507 nm in the absence of ligand to ≈ 481 nm when saturated with a high affinity ligand (Figure 2). This change in maximum absorbance wavelength can be used to quantitate the number of ligand binding sites (Figure 2B). Interestingly, we observed that using the Fab fragment and the SYPRO Orange dye, there is a large decrease in the absorbance of the dye upon titration with cocaine (see Figure 2A), which was not observed in a previous study when doing the essentially the same experiment with the intact h2E2 mAb ((Kirley and Norman, 2021), Figure 2A), suggesting that, unlike the DASPMI dye, the SYPRO Orange dye also bound to sites on the Fc part of the antibody. This is consistent with earlier differential scanning fluorimetry results, demonstrating that the SYPRO Orange dye bound to the Fc fragment, while the DASPMI dye did not (Kirley et al., 2020). Control cocaine titration experiments done in the absence of mAb and its Fab fragment indicated that that the amplitude of the Sypro Orange visible absorbance was much (about 10x) lower in the absence of any protein (analogous to the even larger increase in this dye’s fluorescence when it binds to hydrophobic regions of proteins). This likely explains the large decrease in this dye’s absorption observed when the Fab fragment is titrated with cocaine (see Figure 2A) – the binding of cocaine is displacing the Sypro Orange dye bound to the Fab fragment, and thereby decreasing the total visible absorbance of the dye. Nonetheless, the calculated number of cocaine binding sites using both the DASPMI and the SYPRO Orange absorbance methods were consistent with all the Fab fragment cocaine binding sites being functional (Figures 1B and 2B).

The development of a fluorescence-based assay using either one of these dyes allows the same determination of functional antigen binding sites using much lower concentrations of Fab protein. For reasons which are not apparent, although both dyes resulted in similar results, i.e., a ligand concentration-dependent decrease in dye emission intensity (see Figure 3 for the DASPMI results), the data obtained using the SYPRO Orange dye consistently exhibited more scatter (data not shown). Therefore, the DASPMI dye was used to further characterize the binding of cocaine to both the Fab fragment, and the intact mAb. As shown in Figure 3, this assay gave accurate values for the number of cocaine binding sites present in both the intact mAb and the Fab fragment.

We also evaluated this fluorescence assay for the determination of the number of sites of binding sites of several cocaine metabolites. There are 2 groups of such metabolites, those shown previously to be high affinity ligands for the antibody (cocaine itself (Coc, Kd ≈ 4 nM), cocaethylene (CE, Kd ≈ 1 nM), and benzoylecgonine (BE, Kd ≈ 20 nM)) (Kirley and Norman, 2015), and those metabolites shown previously to be low affinity ligands for the antibody, (norcocaine (NC), ecgonine methyl ester (EME) and ecgonine (EG), which all have high μM Kds (Kirley et al., 2020)). In Figure 4 it is obvious that this fluorescence assay as designed here can be used for the high affinity ligands, but not for the low affinity ligands. This is because the cocaine concentration range used only extended to 10 μM, which is far lower than the Kds for the low affinity ligands, and thus, in contrast to the high affinity ligands, these concentrations would not even come close to saturating the binding sites. We did not attempt to use much higher concentrations of these low affinity ligands in this assay, since the information obtained in Figure 4 is the needed information to evaluate the h2E2 mAb Fab fragment – i.e., the number of binding sites for the high affinity ligands (including cocaine), and the lack of high affinity binding for the other cocaine metabolites.

In conclusion, we report simple, fast, direct, and inexpensive techniques based on ligand-induced changes in extrinsic dye absorption and fluorescence to quantitate cocaine and high affinity cocaine metabolite binding to both high and low concentrations of the Fab fragment of the h2E2 anti-cocaine mAb. The sensitivity of this fluorescence assay was not high as some other fluorescence based methods. The likely reason for this is the relatively low fluorescence quantum yield for the Sypro Orange and DASPMI dyes, which were found to be effective for this assay. However, we have obtained usable data for the Fab fragment and the intact mAb using only 1 μM of cocaine binding sites and the DASPMI assay system, so this methodology can achieve 5 times more sensitive detection than that shown in Figure 3. Regardless of the fluorescence assay sensitivity limitations, these methods should prove useful for biochemical evaluation of some other small molecule binding Fab fragments and intact mAbs, permitting easy assessment of the produced Fab fragments and mAbs needed for in vivo applications.

Highlights.

Cocaine binding of mAb Fab fragments quantitated by extrinsic visible dye absorption

Functional Fab small molecule ligand binding sites are easily and rapidly measured

A novel DASPMI-based dye fluorescence antigen/ligand binding assay was developed

These simple methods may be applicable to other small-molecule mAbs and Fab fragments

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant U01DA039550. We are grateful to Catalent PharmaSolutions, Inc. (Madison, WI) for providing the recombinant humanized h2E2 anti-cocaine mAb protein expressed using their GPex® technology.

Abbreviations

- Fab

Fragment antigen-binding

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- h2E2

humanized anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody

- DASPMI

(4-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-methylpyridinium iodide

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- CE

cocaethylene

- COC

cocaine

- BE

benzoyl ecgonine

- NC

norcocaine

- EME

ecgonine methyl ester

- EG

ecgonine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interests

Dr. Norman is named as a co-inventor on a portfolio of patents for the matter and use of the h2E2 humanized anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody.

References

- Kirley TL, Greis KD and Norman AB, 2016a, Selective disulfide reduction for labeling and enhancement of Fab antibody fragments. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 480, 752–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirley TL, Greis KD and Norman AB, 2016b, Structural characterization of expressed monoclonal antibodies by single sample mass spectral analysis after IdeS proteolysis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 477, 363–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirley TL and Norman AB, 2015, Characterization of a recombinant humanized anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody and its Fab fragment. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 11, 458–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirley TL and Norman AB, 2018, Unfolding of IgG domains detected by non-reducing SDS-PAGE. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 503, 944–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirley TL and Norman AB, 2020a, Ligand binding to a humanized anti-cocaine mAb detected by non-reducing SDS-PAGE. Biochemistry and biophysics reports 23, 100795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirley TL and Norman AB, 2020b, Multi-domain unfolding of the Fab fragment of a humanized anti-cocaine mAb characterized by non-reducing SDS-PAGE. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 533, 580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirley TL and Norman AB, 2021, Ligand binding to a humanized anti-cocaine mAb measured by dye absorption spectroscopy. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 535, 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirley TL, Norman AB and Wetzel HN, 2020, A novel differential scanning fluorimetry analysis of a humanized anti-cocaine mAb and its ligand binding characteristics. J Immunol Methods 476, 112676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton CJ and Hellinga HW, 2010, Thermodynamic analysis of ligand-induced changes in protein thermal unfolding applied to high-throughput determination of ligand affinities with extrinsic fluorescent dyes. Biochemistry 49, 10831–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton CJ and Hellinga HW, 2011, Quantitation of protein-protein interactions by thermal stability shift analysis. Protein Sci 20, 1439–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman AB, Gooden FC, Tabet MR and Ball WJ, 2014, A recombinant humanized anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody inhibits the distribution of cocaine to the brain in rats. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 42, 1125–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S, Semple A, Cheung J and Shameem M, 2013, DSF method optimization and its application in predicting protein thermal aggregation kinetics. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 102, 2471–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Zhou M, Ahrendt AJ, Duke NEC, Tabaja N, Ball WJ, Kirley TL, Norman AB, Joachimiak A, Schiffer M, Wilton R and Pokkuluri PR, 2019, Structural analysis of free and liganded forms of the Fab fragment of a high-affinity anti-cocaine antibody, h2E2. Acta crystallographica. Section F, Structural biology communications 75, 697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocci F and Ling W, 2005, Medications development: successes and challenges. Pharmacol Ther 108, 94–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel HN, Tabet MR, Ball WJ and Norman AB, 2014, The effects of a humanized recombinant anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody on the disposition of cocaethylene in mice. International immunopharmacology 23, 387–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel HN, Webster RP, Saeed FO, Kirley TL, Ball WJ and Norman AB, 2017, Characterization of a recombinant humanized anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody produced from multiple clones for the selection of a master cell bank candidate. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 487, 690–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JJ, Wright SK, Ghozalli I, Mehra R, Furuya K and Katayama DS, 2016, Simultaneous High-Throughput Conformational and Colloidal Stability Screening Using a Fluorescent Molecular Rotor Dye, 4-(4-(Dimethylamino)styryl)-N-Methylpyridinium Iodide (DASPMI). Journal of biomolecular screening 21, 842–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]