Abstract

Small changes to molecules can have profound effects on their pharmacological activity as exemplified by the addition of the two-carbon acetyl group to make drugs more effective by enhancing their pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic properties. N-acetyl-d,l-leucine is approved in France for vertigo and its l-enantiomer is being developed as a drug for rare and common neurological disorders. However, the precise mechanistic details of how acetylation converts leucine into a drug are unknown. Here we show that acetylation of leucine switches its uptake into cells from the l-type amino acid transporter (LAT1) used by leucine to organic anion transporters (OAT1 and OAT3) and the monocarboxylate transporter type 1 (MCT1). Both the kinetics of MCT1 (lower affinity compared to LAT1) and the ubiquitous tissue expression of MCT1 make it well suited for uptake and distribution of N-acetyl-l-leucine. MCT1-mediated uptake of a N-acetyl-l-leucine as a prodrug of leucine bypasses LAT1, the rate-limiting step in activation of leucine-mediated signalling and metabolic process inside cells such as mTOR. Converting an amino acid into an anion through acetylation reveals a way for the rational design of drugs to target anion transporters.

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Medicinal chemistry, Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics

Introduction

N-acetyl-dl-leucine has been used as an over-the-counter drug for the treatment of vertigo since 1957 (Tanganil, Laboratoires Pierre Fabre)1. Currently, N-acetyl-leucine is being intensively studied by both academia and industry as a promising treatment for several disorders with unmet medical needs including cerebellar ataxia2–4, cognition and mobility in the elderly5, lysosomal storage disorders6–9, migraine10 and restless legs syndrome11. Three multinational clinical trials are ongoing with the purified L-enantiomer for the treatment of Niemann-Pick disease type C, the GM2 gangliosidoses, and Ataxia-Telangiectasia12 (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03759639, NCT03759665, NCT03759678).

Given the promise of N-acetyl-l-leucine as a drug for treating many disease indications, there is intensifying interest in its mechanism of action. The current working hypothesis to reconcile the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data is that N-acetyl-l-leucine enters metabolic pathways, and its effects are mediated via its metabolic products13. Therefore, pharmacokinetic factors may be playing a major role to its mechanism of action and efficacy as a drug. Moreover, our recent findings that the enantiomers of N-acetyl-leucine (N-acetyl-l-leucine and N-acetyl-d-leucine) show unexpected and large differences in pharmacokinetics suggesting the involvement of differential binding sites provided by enzymes and transporters13.

Transporters exist in the membrane of all cells and are required for the uptake of small-molecule (100–500 Da) drugs that are not sufficiently hydrophobic to cross the membrane by simple passive diffusion14,15. As the major barrier to membrane crossing is the hydrophobic interior16, small, hydrophobic, neutral molecules can pass by passive diffusion (Fig. 1a), whereas hydrophilic molecules such as cations, anions and zwitterions, (including all α-amino acids) can only cross with the aid or solute carriers (SLC) transporters (Fig. 1a). Approximately 450 transporter-like genes are expressed in humans and are categorized into two major superfamilies: the solute carrier (SLC) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters15.

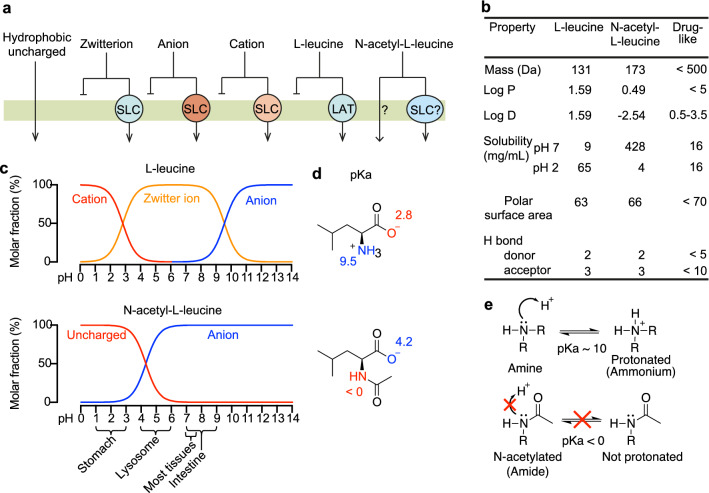

Figure 1.

The effects of N-acetylation on the chemical properties and pharmacological consequences of the drug N-acetyl-l-leucine. (a) Mechanisms of absorption illustrated by crossing a membrane by passive diffusion or carrier-mediated uptake. In general, hydrophobic uncharged molecules can cross lipid bilayer membranes through simple passive diffusion, whereas charged molecules including zwitterions (a positive and negative charge within the same molecule), anions and cations cannot cross membranes without a transporter. Over 400 Solute Carrier (SLC) transporters are known with broad but overlapping selectivities for substrate. l-leucine as an obligate zwitterion at all biologically relevant pH values has an absolute requirement for its carrier, the high-affinity l-type amino Acid Transporter (LAT1). In contrast, N-acetyl-l-leucine can exist as a neutral species and passively cross membranes at low pH, or as an anion recognized by other transporters. (b) Comparison of the physicochemical properties of l-leucine and N-acetyl-l-leucine relating to oral bioavailability. (c) Speciation curves for the protonation states of l-leucine and N-acetyl-l-leucine. The gross charge distribution of a molecule as a function of pH is calculated as well. The dominant species is indicated in several tissues relevant to drug absorption and distribution. (d) Chemical structures showing charge at pH 7 with the pKa of the amino and carboxylic acid groups labelled. (e) Lewis structures illustrating the effect of N-acetylation on the pKa of nitrogen atom. Resonance delocalization of the lone pair electrons in the amide greatly decreases the basicity of the nitrogen relative to the amine, making the molecule neutral or charged, respectively.

As transporters are often a rate-limiting step in drug absorption and distribution14,15, the objective of the present study was to explore uptake of N-acetyl-l-leucine. The strategy we used was to first analyze the physicochemical properties associated with good oral bioavailable drugs17 and how these are altered by N-acetylation of l-leucine. Our calculations show that at physiological pH, l-leucine is a zwitterion, whereas N-acetyl-l-leucine is present as mainly an anion. We then tested candidate organic anion transporters and found that N-acetyl-l-leucine is a translocated substrate for organic anion transporters OAT1 (SLC22A6) and OAT3 (SLC22A8) and the monocarboxylate transporter (MCT1; SLC16A1). These results provide a mechanistic explanation for why N-acetyl-l-leucine acts as a drug and its parent l-leucine is not.

Results

Acetylation alters physicochemical properties that alter membrane permeability

Several physicochemical parameters have been reported to correlate with the ability of small molecule drugs to cross membranes17–22. These physicochemical parameters relate to whether a small molecule can cross a membrane by passive diffusion, known in the field as being ‘drug-like’, or requires carrier-mediated transport (Fig. 1b)22. Therefore, it is instructive to compare the amino acid l-leucine with the modified amino acid N-acetyl-l-leucine to help understand how N-acetylation converts a l-leucine into a drug. Both molecules possess similar physicochemical parameters, except for log P, log D and solubility (Fig. 1b). Log P is the octanol:water partition coefficient for the neutral form of a compound. In contrast, log D considers the ionization state of a molecule in aqueous (biological) solution resulting from basic groups gaining a proton and acidic groups losing a proton, and as such is better correlated with passive diffusion across membranes21,22. For N-acetyl-l-leucine a log D of − 2.54 (Fig. 1b) and its speciation curve (Fig. 1c) resulting from the effect of acetylation on pKa (Fig. 1d) predicts a low rate of passive diffusion across membranes16,17,19,21 in the neutral environment of the intestine and would require a carrier, as for short-chain fatty acids23 and acidic drugs such as acetylsalicylic acid24.

Physicochemical properties necessitate a major role for carrier-mediated uptake

Passive diffusion of N-acetyl-leucine could occur across membranes in acidic conditions such as the stomach (Fig. 1c), but in environments with physiological and approximately neutral pH such as the intestine and tissues to which N-acetyl-leucine distributes13,25, carrier-mediated transport is required26. Moreover, pharmacokinetics following oral administration in mice revealed high levels of interference between the l- and d-enantiomers of N-acetyl-leucine13 suggestive of a specific and saturable binding site and carrier-mediated uptake. Therefore, we investigated candidate transporters for N-acetyl-leucine. Of the 450 possible transporters14 we narrowed them down to plausible candidates based on the physicochemical and steric effect of acetylation (Fig. 1a–e), reported structure–activity relationship, tissue and cell expression and their kinetic parameters (low affinity)14.

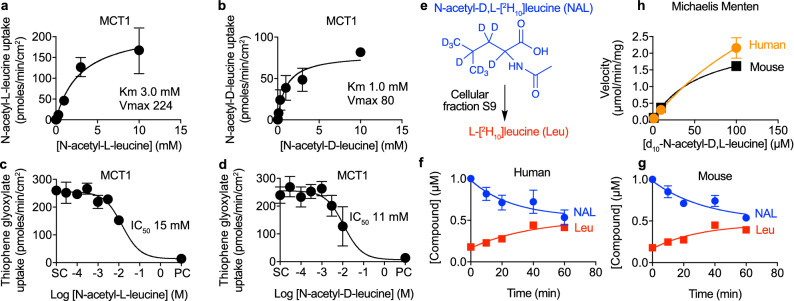

The leucine transporter LAT1 does not transport N-acetyl-l-leucine

We explored LAT1 (SLC7A5) as a candidate for N-acetyl-l-leucine transport as it is the main endogenous transporter for leucine in most cells27,28, 8 of the 9 essential amino acids and cysteine, as well as the amino acid-related drugs T3, T4, l-dopa, baclofen, melphalan, gabapentin and the dopamine precursor l-DOPA29,30. Further, LAT1 is well-characterized in terms of transport mechanism, substrate specificity and regulation29,31, is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues32 and is the rate-limiting step in leucine activation of mTORC133,34, which is responsible of cell growth and survival35, and could explain mechanistic pharmacology of N-acetyl-l-leucine2–8,10. However, we found that N-acetyl-leucine was not a substrate (Fig. 2a) nor an inhibitor of LAT1 (Fig. 2c), consistent with a previous study that used an indirect assay with radioactive leucine as a surrogate36. Small molecules can act as inhibitors if they interact with the substrate binding site without being translocated across the membrane26. This a component in the kinetics of transport, where binding precedes the conformational change that catalyses translocation of the substrate across the membrane.

Figure 2.

N-acetyl-l-leucine is not transported by either the l-type amino acid transporter (LAT1) nor the peptide transporter (PepT1). Concentration–response curves for the uptake of N-acetyl-l-leucine by (a) LAT1 and (b) PepT1. Concentration-inhibition curves for the inhibition of uptake of known substrates (c) gabapentin (10 µM) for LAT1 and (d) dipeptide Gly-Sar (50 µM) for PepT1. DMSO (0.5%) was the solvent control (SC) and the known inhibitor for the positive control (PC) was JPH203 (10 µM) for LAT1 and losartan (200 µM) for PepT1. Data were fit to either the Michaelis–Menten equation for uptake or the Hill equation for inhibition using the solvent control to define the top and the positive control inhibitor to define the bottom. Symbols represent the mean ± SEM, n = 3. When the error bars are smaller than the symbol, they are not visible.

The peptide transporter PepT1 does not transport N-acetyl-l-leucine

We next focused in on the effect of introducing an amide bond by acetylation (Fig. 1d), which sterically resembles the backbone of a di-peptide, an important recognition feature for peptide transporters. PepT1 (SLC15A1) was considered as a good transporter candidate based on it being well characterized, low affinity, and a popular target for the delivery of peptide-like prodrugs with an amino acid-like moiety designed to improve oral absorption and bioavailability of peptide-like drugs and prodrugs14,37–40. However, N-acetyl-l-leucine was not a substrate (Fig. 2b) but instead was an inhibitor of the peptide transporter PepT1, with an IC50 of 0.74 mM (Fig. 2d). The reason for negative values for N-acetyl-l-leucine uptake are unknown, but could be due to N-acetyl-l-leucine existing endogenously as a metabolite in cells, consistent with it being reported as a product of normal intermediary metabolism41, and could be resolved with stable or radiolabelled isotope uptake experiments. As most substrate-like inhibitors bind to the same binding site the inhibition is competitive and given that di-and tripeptides are present in the gut at high millimolar concentrations28, this level of inhibition would not be of pharmacological consequence as dietary peptides would outcompete N-acetyl-l-leucine at PepT1.

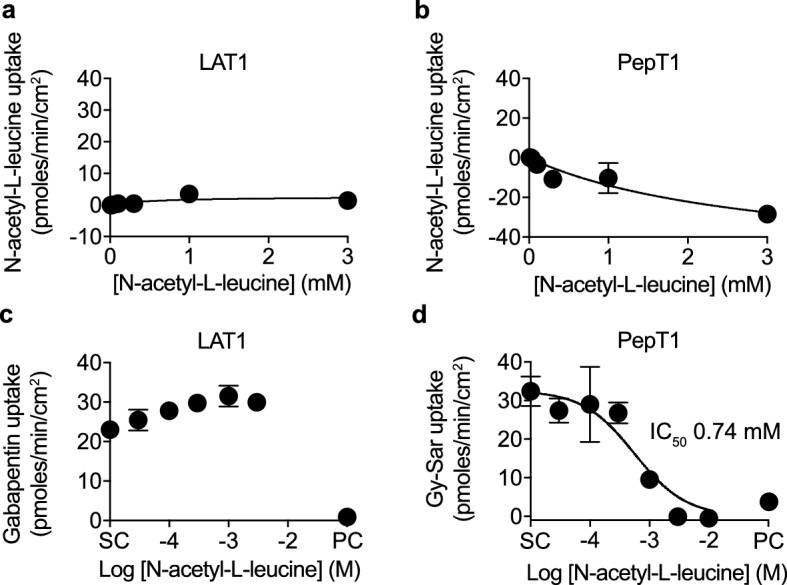

The organic anion transporter OAT transports N-acetyl-l-leucine

We then pursued the hypothesis that the salient chemical feature for carrier-mediated uptake was conversion of leucine from a zwitterion to an anion (Fig. 1c). Anion transporters are known to be of relevance in drug development for their roles in drug distribution, elimination and drug-drug interactions15,24. We considered members of the organic anion transporters (OATs) family as candidates based on their structure–activity relationships, kinetics, pattern of tissue expression and role in the pharmacokinetics of many drugs42–44. N-acetyl-l-leucine was a substrate of OAT1 (Fig. 3a) and OAT3 (Fig. 3b). Based on the ability of N-acetyl-l-leucine to inhibit the uptake of the known substrates chlorothiazide and estrone sulfate (Fig. 3c,d), it inhibited OAT1 with a IC50 of 6.2 mM (Fig. 3c) and OAT3 with an IC50 of 0.70 mM (Fig. 3d). The plots in Fig. 3 represent uptake by the overexpressed transporter because they are the difference between uptake in transporter-expressing cells and non-expressing cells at a given time point (Supplementary Fig. S1). Consistent with N-acetyl-l-leucine being a substrate, meaning the molecule had to bind before being transported, and that transport is less efficient than binding as the IC50 is less than the Km.

Figure 3.

N-acetyl-l-leucine is transported by organic anion transporters (OAT). Concentration–response curves for the uptake of N-acetyl-l-leucine by (a) OAT1 and (b) OAT3. Concentration-inhibition curves for the inhibition of uptake of known substrates (c) chlorothiazide for OAT1 (3 µM) and (d) estrone-3-sulfate for OAT3 (2 µM). DMSO (0.5%) was the solvent control (SC) and the known inhibitor diclofenac (100 µM) was the positive control (PC). Data were fit to either the Michalis-Menten equation for uptake or the Hill equation for inhibition using the solvent control to define the top and the positive control inhibitor to define the bottom. Symbols represent the mean ± SEM, n = 3. When the error bars are smaller than the symbol, they are not visible.

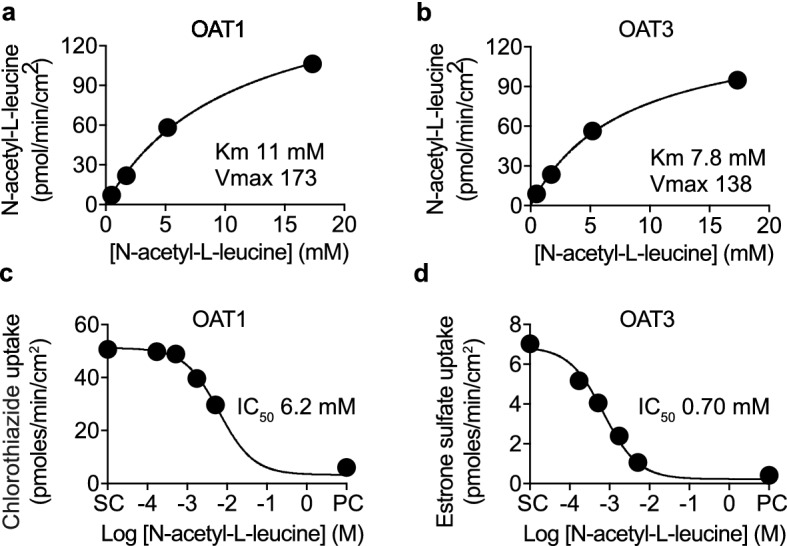

The monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 transports N-acetyl-l-leucine

We then reasoned that a major transporter for N-acetyl-l-leucine would recognize organic anions but should also be widely distributed in tissues and be accepted to have the right cellular directionality of transport to take up rather than excrete N-acetyl-l-leucine. One family of transporters stood out as a possibility was the proton-linked MCT family with 14 members, of which MCT1–MCT4 are well characterized14,45. MCT members are endogenously involved in the bidirectional movement (into and out of cells) of metabolites that perform signalling and energy/metabolic roles including ketone bodies and pyruvate, and uptake of small organic aliphatic acids produced by microbes from the gastrointestinal tract45. MCT family members play an essential role in the metabolism and pH regulation of cells by moving lactate into and out of cells45. As these metabolites are present in the micromolar to millimolar range, the kinetics of these transporter feature low affinity45. MCT family members are widely expressed at various tissues, including the intestine, brain, kidney and liver46, delivering various substrates, and a potential target for oral drug delivery as it possesses high transport capacity47,48. MCT1 (SLC16A1) is present in almost all tissues and is involved in several drugs and nutrients including salicylate, valproate, atorvastatin and γ-hydroxybutyrate, for both uptake and crossing the blood–brain barrier45.

We found that N-acetyl-l-leucine was a substrate of MCT1 with a Km of 3.0 mM (Fig. 4a) and an inhibitor of MCT1 (Fig. 4c) with an IC50 of 15 mM. As N-acetyl-leucine exhibits stereospecific effects for both its pharmacodynamics2–8,10 and pharmacokinetics13, we also explored transport of the D-enantiomer. N-acetyl-D-leucine was also a substrate, with Km of 1.0 mM (Fig. 4b), and an inhibitor of MCT1 with an IC50 of 11 mM (Fig. 4d). As both transport and inhibition require a binding step, a Km higher than the IC50 can be attributable to the slower kinetics of translocation, but the reverse order seemed odd. We rationalized this by assuming competitive inhibition at a common binding site and then taking into account the interaction between concentration and affinity as described mechanistically by the Cheng–Prusoff equation49, which yielded an affinity (Ki) of 4.3 mM for the l-enantiomer and 1.6 mM for the d-enantiomer, similar to the respective Km values. This enantiomeric selectivity during transport by MCT1 provides a mechanistic explanation for the lower bioavailability of the l-enantiomer when administered as a racemate which impacts its therapeutic efficacy13.

Figure 4.

Both enantiomers of N-acetyl-leucine are transported by the monocarboxylate transporter (MCT1) but only the l-enantiomer is metabolized. Concentration–response curves for the uptake of (a) N-acetyl-l-leucine and (b) N-acetyl-d-leucine. Concentration-inhibition curves for the inhibition of uptake of the known substrate (c, d) 2-thiophene glyoxylate (500 µM). DMSO (0.5%) was the solvent control (SC) and the known inhibitor phloretin (500 µM) was the positive control (PC). (e) Chemical structure of deuterated N-acetyl-d,l-leucine incubated with cellular fraction S9 from liver to determine metabolism using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. (f, g) Time courses for loss of deuterated N-acetyl-d,l-leucine (1 µM initial concentration) and appearance of deuterated L-leucine for extracts derived from human and mouse livers. Data are colour-coded according to the chemical structures and names shown in e with deuterated N-acetyl-d,l-leucine in blue and deuterated l-leucine in red. (h) Concentration versus initial velocities relationship for metabolism yielded a Km values of 216 and 69 µM and Vmax values of 6.8 and 2.6 µmol/min/mg protein for human and mouse, respectively. Data were fit to the Michalis–Menten equation for transporter uptake and metabolism or the Hill equation for transporter inhibition using the solvent control to define the top and the positive control inhibitor to define the bottom. Symbols represent the mean ± SEM, n = 3. When the error bars are smaller than the symbol, they are not visible.

N-acetyl-l-leucine is metabolized to l-leucine inside cells

As enantiomeric effects on pharmacokinetics13 could also be due to metabolism, we monitored the metabolism of a deuterated N-acetyl-dl-leucine incubated with S9 microsome fraction from liver (Fig. 4e) using liquid chromatography and mass spectroscopy. The time course revealed that the disappearance of 1 µM N-acetyl-dl-[2H10]leucine asymptotically approached 50% of the initial concentration (i.e., 0.5 µM) and correlated well with the appearance of l-leucine for both human (Fig. 4f) and mouse (Fig. 4g) fractions. Kinetic data fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation yielded a Km values of 216 and 69 µM and Vmax values of 6.8 and 2.6 µmol/min/mg protein for human and mouse, respectively (Fig. 4h). Asymmetric metabolism of the l-enantiomer relative to the d-enantiomer is consistent with previous reports of deacetylation of l but not d amino acids50–54. These metabolic results provide a mechanistic explanation for the faster clearance the l-enantiomer than the d-enantiomer after oral dosing of mice13, and are consistent with N-acetyl-l-leucine acting as prodrug, such as l-dopa, in which both uptake and metabolism are crucial components of its mechanism of action55.

Discussion

Based on previous studies and our current results, we propose a mechanism of action of N-acetyl-leucine in which it is taken up and distributed by anion transporters, primarily MCT1. From the l-enantiomer, the l-leucine will be expected to be mostly utilized in the cell that deacetylates it, based studies on the uptake and utilization of 14C-l-leucine56, with the important exception of the liver, which in contrast to all other amino acids does not metabolize leucine, but rather secretes it into the circulation for the use by other tissues, particularly skeletal muscle and the central nervous system57. MCT1-mediated uptake of N-acetyl-l-leucine provides a way to bypass the easily saturable uptake via LAT1 to deliver more leucine to tissues. Indeed, at the blood–brain barrier, LAT1 is not just limited by a low Km and saturation but also by competition by neural amino acids58, which has implications for the availability of amino acids to the central nervous system that are precursors for neurotransmitters. In contrast to the LAT1 system that is saturated by amino acids at normal blood levels (total ~ 2.4 mM)59, MCT1 can deliver leucine via the prodrug form N-acetyl-l-leucine without interference from, and disruption to, the uptake of other essential amino acids. Another aspect of transport by MCT1 is that for uptake by LAT1, leucine competes with other amino acids such as tyrosine and phenylalanine, which are precursors of neurotransmitters, and is thought to underlie the leucine toxicity in Maple Syrup Disease60. MCT1 provides a mechanism to signal via leucine by bypassing the normal uptake by LAT1, which is limited by glutamine in an amino acid-exchange model, and activate intracellular leucine sensors and activate powerful processes such as mTORC133,60. All uptake via MCT1-mediated uptake provides a mechanistic explanation for the apparent paradox in which N-acetyl-l-leucine is a prodrug of leucine but leucine per se is considerably efficacious in several neurological disorders8,57,61,62.

The kinetics of a transporter having high or low affinity has implications for exploiting transporters for the delivery of prodrugs48. In general, the affinities of transporters are considered to be of high affinity when Km < 0.5 mM, medium affinity when Km 0.5–5 mM and low affinity when Km 5–15 mM63. The Km for N-acetyl-leucine for MCT1 and the OATs places it in the medium affinity category, but it is in the range for other monocarboxylate metabolites such as pyruvate, lactate, acetoacetate, beta-hydroxybutyrate, which are in the 1–10 mM range45,64. The biochemical and evolutionary advantages and disadvantages of high affinity compared to low affinity have been the subject of intense theoretical and experimental studies, with one view being that they favour scarce or plentiful nutrients, respectively65. Far less attention has been given to drug transport, but the consequences can be profound in terms of how easily transporters are saturated and becoming limiting for the delivery of a compound, as will be discussed below.

The transport of N-acetyl-l-leucine by MCT1, OAT1 and OAT3 impacts on its pharmacokinetics. The lower affinity of MCT1 for N-acetyl-l-leucine relative to LAT1 for l-leucine prevents transporter saturation and enables operation in the linear region of the concentration-uptake curve. This can be illustrated by a numerical example comparing Km and compound concentrations for l-leucine and N-acetyl-leucine. Taking stomach volume of a fasted individual as the accepted standard of 0.25 L66 a 4-g dose would result in 122 mM l-leucine and 92 mM N-acetyl-l-leucine. For l-leucine the LAT1 transporter would be 50% saturated at 0.2 mM (its Km), 90% saturated at 2 mM and 99% saturated at 20 mM, corresponding to oral ingestion of 0.000656 g, 0.00656 g and 0.656 g, respectively. In contrast, N-acetyl-l-leucine, if transported by MCT1 with a Km of 3 mM it would be 50% saturated at 3 mM (its Km), 90% saturated at 30 mM and 99% saturated at 300 mM, corresponding to an oral ingestion of 0.149 g, 1.49 g and 14.3 g, respectively. OAT1 and OAT3 are involved mostly in drug and nutrient distribution rather than uptake from the gastrointestinal tract67. Moreover, based on their being primarily localized in the kidney and choroid plexus for the secretion of anionic waste and xenobiotics from the cerebrospinal fluid to the blood and urine67, the impact of OAT1 and OAT3 on N-acetyl-l-leucine would be removal from the body. However, given their higher Km values of 11 mM and 7.8 mM, respectively, OAT1 and OAT3 removal would be less effective than MCT1 uptake from the blood where N-acetyl-l-leucine levels peak in the 0.1–1 mM range13,68. The relative role of these competing organic anion transporters requires further experimentation.

The broader implication of transport via MCT1 relates to its ability to transport in two different modes. MCT1, like other MCT family members, can operate unidirectionally by taking a monocarboxylate and a proton across a membrane45, or bidirectionally in an antiport exchange mode where monocarboxylates are swapped, which is much faster than the unidirectional mode29,46. MCT1 catalyses either net transport of one monocarboxylate with one proton or the exchange of one carboxylate for another45. MCT1 can function as a symporter or co-transporter with exchanger functionality (downhill transport) and also perform tertiary active transport (uphill transport) in the presence of either a pH gradient or when functioning as an exchanger in an antiport mode if the co-transported substrate has a membrane gradient29,46.

The exchange mode of MCT1 transport has important implications for both the rare disorders for which it has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment and those under current study2–4. One of the common metabolic changes in lysosomal storage disorders such as Nieman-Pick disease type C is a metabolic shift toward the glycolytic pathway resulting in decrease in the efficiency of ATP synthesis and an increase in the metabolic monocarboxylate end product lactate8,69. Cells with high concentrations of lactate would be predicted to increase the uptake of N-acetyl-leucine through exchange mode, thereby delivering more drug to cells with metabolic dysfunction, and simultaneously lower intracellular lactate concentrations. Increased glycolysis and lactate production is also a feature in several neuropathological disorders including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s70–72 as well as in stroke and traumatic brain injury73. Moreover, cerebral ischemia can upregulate the expression of MCT1 in astrocytes47,74, again favouring delivery of drug into these cells. MCT1 provides a target for a unifying working hypothesis for how N-acetyl-l-leucine is effective in treating both rare and common diseases. The most wide-spread implication of this work is that it demonstrates the potential importance of organic anion families of transporters in drug mechanism of action47,48, in particular prodrugs created by acetylation which become acidic.

Methods

General chemicals

High pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade methanol and acetonitrile were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), and formic acid, acetic acid and ammonium formate were obtained from BDH Laboratory Supplies (Poole, UK). N-Acetyl-l-Leucine was obtained from Laboratories Pierre Fabre and dissolved directly to incubation buffer at the highest incubation concentration on the day of incubations. N-Acetyl-d-Leucine and all other chemicals were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Helsinki, Finland) at the highest purity available. Water was in-house freshly prepared with a Direct-Q3 (Millipore Oy, Espoo, Finland) purification system and UP grade (ultra-pure, 18.2 MΩ).

Human solute carrier (SLC) transporter-mediated cellular uptake and inhibition

Human OAT1 (SLC22A6) and OAT3 (SLC22A8) overexpressing HEK-293 cells and control cells without transfected transporter (Corning TransportoCellsTM) were plated to 24-well plates and cellular uptake of 10 to 100 μg/mL N-acetyl-l-leucine was measured in the absence and presence of transporter inhibitors. N-acetyl-l-leucine uptake into control cells was measured only without chemical inhibitors. Positive control substrates were incubated in parallel to demonstrate presence of active transport in each transporter transfected cell line. Cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco 4196, high glucose, without sodium pyruvate) supplemented with MEM non-essential amino acids and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were re-fed with fresh medium after attachment (4–6 h post-seeding). Cell were plated at a density of 4 × 105/well in 24-well plates coated with poly-d-lysine. Transporter assays were conducted in 400 µL of HBSS supplemented with 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4

Transport studies with human PepT1 (SLC15A1), LAT1 (SLC7A5) and MCT1 (SLC16A1) were conducted in MDCK-II cells expressing the human transporter or control cells expressing a vector with Green Fluorescence Protein. Cells were transfected using a proprietary, transient transfection system (OPTI-EXPRESSION Technology, BioIVT). The results from the control cells were used to correct for substrate permeation by routes other than the transporter being investigated in the study. That is, identical transport studies were conducted using cells expressing the transporter of interest and control cells which do not express the transporter, with the difference in uptake used to quantify transporter-mediated uptake. Specifically, Net Transporter Mediated Substrate Uptake (pmol/min/cm2) = (Cellular accumulation in the presence of the transporter) − (Mean cellular accumulation in the absence of the transporter). MDCK-II cells were maintained in DMEM with low glucose and 10% FBS. Cells were used at passages up to 40 were seeded at 60,000 ± 10,000 cells/well on 96-well plates approximately 24 h before transfection, and transport assays were performed approximately 48 h after transfection. Transport studies in MDCK-II cells were conducted in 96-well insert plates with permeable membrane (0.4 µm) and receiver tray (Millipore MultiScreen Filter 96-well).

Transport studies with PepT1 were conducted in 96-well cell culture plate with wells containing a monolayer of MDCK-II cells grown on a permeable support and a corresponding 96-well receiver tray. Cell plates are maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere prior to initiation of the transport experiment. Pre-incubation was conducted in HBSS, pH 7.4. The transport experiments were conducted in HBSS with Bis–Tris, pH 5.5, without phenol red. Both pre-incubation and incubation were conducted at 37 °C. All final assay solutions of probe substrate, reference inhibitor or test article contain 0.5% (v/v) DMSO (vehicle control). The culture plate insert (basal side) was washed with warm HBSS three times and then blotted dry. The culture plate wells (apical side) were washed with warm HBSS three times. 100 µL of 37 °C HBSS pH 7.4 pre-incubation buffer to the apical compartment as follows: for the probe substrate transport assay, the HBSS contains vehicle; for the reference inhibition assay, the HBSS contains the reference inhibitor at the required concentration; for the test article assays, the HBSS in each well contains test compound at the specified concentration. The plates were incubated at 37 °C with orbital shaking at approximately 60 rpm for the pre-incubation (30 min), aspirated and then 100 µL of the experimental buffer was added. For the transport assays the experimental buffer was HBSS with Bis–Tris, pH 5.5 with probe substrate at the required concentration and vehicle control (0.5% DMSO); reference inhibitor and the probe substrate at the required concentrations for the reference inhibition assay; and the test compound and the probe substrate at the required concentrations for the test compound assays. Assays were incubated at 37 °C with orbital shaking at ~ 60 rpm for 5 min. Then both the apical and the basal side of the permeable support were washed four times with ice-cold PBS. Cells were extracted by adding 60 µL acetronitrile:water (50:50) to each well followed by agitation on an orbital shaker at ~ 120 rpm for 15 min. Then a 30-µL sample was taken and mixed with 200 µL of scintillation fluid and scintillation counted (1450 Microbeta, Perkin-Elmer).

Transport studies with MCT1 were performed as described for PepT1 with the following modifications. Both the pre-incubation and uptake incubation were at ambient temperatures and the assay time was 1 min. To the 30-µL extracted sample 30 µL internal standard solution (200 nM carbutamide) to the extracted sample, and then frozen until analysis by Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). Transport studies with LAT1 were performed as described for PepT1 except that the experimental solutions were added to the basal compartment and the buffer was always HBSS pH 7.4.

The known probe substrates used as positive controls were 3 μM chlorothiazide for OAT1, 2 μM estrone-3-sulfate for OAT3, 10 µM [3H]gabapentin for LAT1, 50 µM [3H]Gly-Sar for PepT1, 500 µM thiophene-2-glyoxylic acid for MCT1. The known inhibitors used as controls for each transporter were 100 μM diclofenac for OAT1 and OAT3, 10 µM JPH203 for LAT1 and 200 µM losartan for PepT1. All incubations were in triplicate and contained 1% (OAT1 and OAT3) or 0.5% DMSO (LAT, PepT1 and MCT1). The duration of uptake was 5 min for OAT1 and OAT3, 3 min for LAT1 and PepT1 and 1 min for MCT1. Assays were performed at 37 °C with no shaking, except MCT1 at room temperature. To determine uptake due to the overexpressed transporter per se, uptake was taken as the difference between accumulation between transfected and nontransfected cells in parallel experiments at the same concentration and time. To terminate uptake the plate was placed on ice and cells washed twice with ice-cold transport buffer. To collect cells, they were detached with trypsin for 5 min, and samples of cell suspension transferred into an equal volume of ice-cold acetonitrile. Samples were stored at − 20 °C until analysis. In preparation for analysis, samples were centrifuged 20 min (4000 rpm) to separate the precipitated protein. Samples of supernatant were diluted 1:4 with phosphate buffered saline (OAT1, OAT3). Samples diluted with phosphate buffered saline were used for analysis of N-acetyl-L-leucine.

N-acetyl-leucine metabolism

N-acetyl-d,l-[2H10]leucine was obtained from ChiroBlock (Andresenstraße, Germany) and l-[2H10]leucine was obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Leicestershire, UK). N-acetyl-d,l-[2H10]leucine was incubated at 1 µM, 10 µM and 100 µM with pooled liver S9 fractions from human (mixed gender) and mouse (CD1) at 1.5 mg protein/mL in 300 µL buffer containing phosphate 100 mM, MgCl2 2 mM, pH 7.4 at 37 °C for 0, 10, 20, 40, 60 min. Reactions were terminated by addition of twofold volume of 75% acetonitrile and metabolites separated by liquid chromatography and quantified by mass spectroscopy using multiple reaction monitoring (Thermo Vantage UHPLC + Thermo TSQ Quantis triple quadrupole MS Waters HSS T3 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µm column with guard filter).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

N-acetyl-l-leucine, rosuvastatin, estrone-3-sulfate and chlorothiazide were separated and quantified using a Thermo Vanquish UPLC + Thermo Quantis triple quadrupole MS on a Waters Acquity HSS T3 (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm) column with guard filter. A sample of 4 µL was injected and compounds were eluted at 35 °C with a flow of 0.65 mL/min using a gradient of solvent A = 0.1% formic acid and solvent B = acetonitrile as follows (Time, A%): 0.0, 95; 0.5, 95; 2.5, 40; 3.5, 5; 4.5, 95.

Calculations

The IC50 value for the test item was determined by fitting the Hill equation in the following form:

where A% is the percent activity remaining (the mean cellular uptake observed in the solvent control sample set to 100% and the mean cellular uptake observed in the presence of the positive control inhibitor set to 0%), Top and Bottom are the upper and lower plateau of A%. [I] is the inhibitor concentration and IC50 is the inhibitor concentration where the remaining activity is at the midpoint between the Top and Bottom. To obtain robust IC50 fit with four test concentrations the Top and the Bottom levels were constrained to 100% and 0%, respectively. The solvent control and positive control inhibitors were also used in the curve fitting to the Hill equation as recommended as the most robust method when the test substance (N-acetyl-L-leucine in our case) could not be used at a sufficiently high concentration to provide complete inhibition75. In inhibition experiments, the IC50 is not equivalent to affinity because it is dependent on the concentrations of the substrate, the inhibitor and affinity; therefore, we assumed competitive inhibition, and calculated affinity of inhibition (Ki) with the Cheng-Prusoff equation49.

Enzyme kinetic data for N-acetyl-l-leucine uptake and metabolism was analysed by fitting the Michaelis–Menten equation to the data. V0 = Vmax. [S]/Km + [S], where V0 is initial velocity, [S] is substrate concentration, Vmax is maximum velocity and Km is substrate concentration at half Vmax. All fitting was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.4 software (GraphPad Software Inc). No weighting scheme was applied.

In silico chemical calculations

The physicochemical properties, pKa and the pH-dependent speciation curves for N-acetyl-l-leucine were performed with the online computational chemistry package Chemicalize (ChemAxon. https://chemicalize.com/app/calculation).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Janne Mannila of Admescope and Mark Warren of BioIVT for helpful insights and advice on solute transporters.

Author contributions

G.C.C., F.M.P. and A.G. conceptualized and designed the experiments. G.C.C. analysed the data and wrote the original draft manuscript which was then reviewed and edited with contributions from all the authors.

Funding

This study was financially supported by IntraBio (https://intrabio.com). The authors (GCC, MS, AG and FMP) were paid for consultancy work for IntraBio. Authors, acting in their capacity as consultants for IntraBio, played roles in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Competing interests

I have read the journal's policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: MS is Joint Chief Editor of the Journal of Neurology, Editor in Chief of Frontiers of Neuro-otology and Section Editor of F1000. He has received speaker’s honoraria from Abbott, Actelion, Auris Medical, Biogen, Eisai, Grünenthal, GSK, Henning Pharma, Interacoustics, Merck, MSD, Otometrics, Pierre-Fabre, TEVA, UCB. He is a shareholder of IntraBio. He acts as a consultant for Abbott, Actelion, AurisMedical, Heel, IntraBio and Sensorion. MF is a co-founder, shareholder, and Chairman of IntraBio. MP is a shareholder of IntraBio and has received consulting fees, honoraria, and research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. and Biomarin. TBE received honoraria for lecturing from Actelion and Sanofi Genzyme. CF is a consultant to IntraBio. GCC, AG and FP are cofounders, shareholders and consultants to IntraBio. IntraBio Ltd is the applicant for patents WO2018229738 (Treatment For Migraine), WO2017182802 (Acetyl-Leucine Or A Pharmaceutically Acceptable Salt Thereof For Improved Mobility And Cognitive Function), WO2019078915 and WO2018029658 (Therapeutic Agents For Neurodegenerative Diseases), WO2018029657 (Pharmaceutical Compositions And Uses Directed To Lysosomal Storage Disorders), and WO2019079536 (Therapeutic Agents For Improved Mobility And Cognitive Function And For Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases And Lysosomal Storage Disorders).

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-95255-5.

References

- 1.Neuzil E, Ravaine S, Cousse H. La N-acétyl-DL-leucine, médicament symptomatique de vertigineux. Bull. Soc. Pharm. Bordeaux. 2002;141:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strupp M, et al. Effects of acetyl-DL-leucine in patients with cerebellar ataxia: A case series. J. Neurol. 2013;260:2556–2561. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7016-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schniepp R, et al. Acetyl-DL-leucine improves gait variability in patients with cerebellar ataxia-a case series. Cerebellum Ataxias. 2016;3:8. doi: 10.1186/s40673-016-0046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalla R, Strupp M. Aminopyridines and acetyl-DL-leucine: new therapies in cerebellar disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019;17:7–13. doi: 10.2174/1570159X16666180905093535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platt F, Strupp M. An anecdotal report by an Oxford basic neuroscientist: Effects of acetyl-DL-leucine on cognitive function and mobility in the elderly. J. Neurol. 2016;263:1239–1240. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bremova T, et al. Acetyl-DL-leucine in Niemann-Pick type C: A case series. Neurology. 2015;85:1368–1375. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortina-Borja M, et al. Annual severity increment score as a tool for stratifying patients with Niemann-Pick disease type C and for recruitment to clinical trials. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2018;13:143. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0880-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaya E, et al. Acetyl-leucine slows disease progression in lysosomal storage disorders. Brain Commun. 2020 doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaya E, et al. Beneficial effects of acetyl-DL-leucine (ADLL) in a mouse model of Sandhoff disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:1050. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strupp M, Bayer O, Feil K, Straube A. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with and without aura with acetyl-DL-leucine: A case series. J. Neurol. 2019;266:525–529. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoser B, Schnautzer F, Bremova T, Strupp M. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with acetyl-DL-leucine: Accidental findings and a small case series. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019;26:694. doi: 10.1111/ene.13776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fields T, et al. A master protocol to investigate a novel therapy acetyl-L-leucine for three ultra-rare neurodegenerative diseases: Niemann-Pick type C, the GM2 gangliosidoses, and ataxia telangiectasia. Trials. 2021;22:84. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-05009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churchill GC, Strupp M, Galione A, Platt FM. Unexpected differences in the pharmacokinetics of N-acetyl-DL-leucine enantiomers after oral dosing and their clinical relevance. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0229585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Transporter Consortium et al. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2010;9:215–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keogh JP. Membrane transporters in drug development. Adv. Pharmacol. 2012;63:1–42. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398339-8.00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Missner A, Pohl P. 110 years of the Meyer-Overton rule: Predicting membrane permeability of gases and other small compounds. ChemPhysChem. 2009;10:1405–1414. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipinski CA. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2000;44:235–249. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8719(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camenisch G, Folkers G, van de Waterbeemd H. Review of theoretical passive drug absorption models: Historical background, recent developments and limitations. Pharm. Acta Helv. 1996;71:309–327. doi: 10.1016/S0031-6865(96)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gleeson MP, Hersey A, Montanari D, Overington J. Probing the links between in vitro potency, ADMET and physicochemical parameters. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrd3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leeson PD, Springthorpe B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2007;6:881–890. doi: 10.1038/nrd2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waring MJ. Defining optimum lipophilicity and molecular weight ranges for drug candidates: Molecular weight dependent lower logD limits based on permeability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:2844–2851. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Waterbeemd H, Camenisch G, Folkers G, Chretien JR, Raevsky OA. Estimation of blood-brain barrier crossing of drugs using molecular size and shape, and H-bonding descriptors. J. Drug Target. 1998;6:151–165. doi: 10.3109/10611869808997889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter A, Gutknecht J. Monocarboxylic acid permeation through lipid bilayer membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 1984;77:255–264. doi: 10.1007/BF01870573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhoff S, Ungell A-L, Zamora I, Artursson P. pH-Dependent passive and active transport of acidic drugs across Caco-2 cell monolayers. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005;25:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benard P, Cousse H, Bengone T, Germain C. Autoradiography in brain of Macaca fascicularis monkeys after injection of acetyl-DL-leucine [2-14C] (Tanganil) Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2001;26:71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03190379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugano K, et al. Coexistence of passive and carrier-mediated processes in drug transport. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:597–614. doi: 10.1038/nrd3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanai Y, et al. Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98) J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23629–23632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krehbiel CR, Matthews JC. Absorption of amino acids and peptides. In: D’Mello JPF, editor. Amino Acids in Animal Nutrition. CABI Publishing; 2003. pp. 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scalise M, Galluccio M, Console L, Pochini L, Indiveri C. The human SLC7A5 (LAT1): The intriguing histidine/large neutral amino acid transporter and its relevance to human health. Front. Chem. 2018;6:243. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares-da-Silva P, Serrão MP. High- and low-affinity transport of L-leucine and L-DOPA by the hetero amino acid exchangers LAT1 and LAT2 in LLC-PK1 renal cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2004;287:F252–261. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00030.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Amo EM, Urtti A, Yliperttula M. Pharmacokinetic role of L-type amino acid transporters LAT1 and LAT2. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008;35:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fagerberg L, et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:397–406. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicklin P, et al. Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell. 2009;136:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bröer S, Fairweather SJ. Amino acid transport across the mammalian intestine. Compr. Physiol. 2018;9:343–373. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pochini L, Scalise M, Galluccio M, Indiveri C. Membrane transporters for the special amino acid glutamine: Structure/function relationships and relevance to human health. Front. Chem. 2014;2:61. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagamori S, et al. Structure-activity relations of leucine derivatives reveal critical moieties for cellular uptake and activation of mTORC1-mediated signaling. Amino Acids. 2016;48:1045–1058. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2158-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawada K, Terada T, Saito H, Hashimoto Y, Inui KI. Recognition of L-amino acid ester compounds by rat peptide transporters PEPT1 and PEPT2. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;291:705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson BR, Shi J, Zhu H-J, Smith DE. Pharmacokinetics of gemcitabine and its amino acid ester prodrug following intravenous and oral administrations in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020;180:114127. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandsch M, Knütter I, Leibach FH. The intestinal H+/peptide symporter PEPT1: Structure-affinity relationships. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004;21:53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0928-0987(03)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubio-Aliaga I, Daniel H. Peptide transporters and their roles in physiological processes and drug disposition. Xenobiotica. 2008;38:1022–1042. doi: 10.1080/00498250701875254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bloch K, Borek E. Biological acetylation of natural amino acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1946;164:483. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)43087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koepsell H, Endou H. The SLC22 drug transporter family. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:666–676. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin L, Yee SW, Kim RB, Giacomini KM. SLC transporters as therapeutic targets: Emerging opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:543–560. doi: 10.1038/nrd4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nigam SK, et al. The organic anion transporter (OAT) family: A systems biology perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2015;95:83–123. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halestrap AP, Wilson MC. The monocarboxylate transporter family: Role and regulation. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:109–119. doi: 10.1002/iub.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enerson BE, Drewes LR. Molecular features, regulation, and function of monocarboxylate transporters: Implications for drug delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003;92:1531–1544. doi: 10.1002/jps.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puri S, Juvale K. Monocarboxylate transporter 1 and 4 inhibitors as potential therapeutics for treating solid tumours: A review with structure-activity relationship insights. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;199:112393. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang G, et al. Intestinal OCTN2- and MCT1-targeted drug delivery to improve oral bioavailability. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2020;15:158–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bloch K, Rittenberg D. The metabolism of acetylamino acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1947;169:467–476. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)30863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheffner AL, et al. Metabolic studies with acetylcysteine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1966;15:1523–1535. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(66)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neuhäuser M, Wandira JA, Göttmann U, Bässler KH, Langer K. Utilization of N-acetyl-L-tyrosine and glycyl-L-tyrosine during long-term parenteral nutrition in the growing rat. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1985;42:585–596. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.ImHaesook A, MeyerPaul D, Stegink LD. N-acetyl-L-tyrosine as a tyrosine source during total parenteral nutrition in adult rats. Pediatr. Res. 1985;19:514–518. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birnbaum SM, Levintow L, Kingsley RB, Greenstein JP. Specificity of amino acid acylases. J. Biol. Chem. 1952;194:455–470. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)55898-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gregori-Puigjané E, et al. Identifying mechanism-of-action targets for drugs and probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:11178–11183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204524109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee AJ, et al. A (14)C-leucine absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) study in adult Sprague-Dawley rat reveals β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate as a metabolite. Amino Acids. 2015;47:917–924. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-1920-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalogeropoulou D, Lafave L, Schweim K, Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ. Leucine, when ingested with glucose, synergistically stimulates insulin secretion and lowers blood glucose. Metabolism. 2008;57:1747–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eriksson T, Björkman S, Höglund P. Clinical pharmacology of thalidomide. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001;57:365–376. doi: 10.1007/s002280100320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith QR, Momma S, Aoyagi M, Rapoport SI. Kinetics of neutral amino acid transport across the blood-brain barrier. J. Neurochem. 1987;49:1651–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ananieva EA, Powell JD, Hutson SM. Leucine metabolism in T cell activation: mTOR signaling and beyond. Adv. Nutr. 2016;7:798S–805S. doi: 10.3945/an.115.011221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tighilet B, Leonard J, Bernard-Demanze L, Lacour M. Comparative analysis of pharmacological treatments with N-acetyl-DL-leucine (Tanganil) and its two isomers (N-acetyl-L-leucine and N-acetyl-D-leucine) on vestibular compensation: Behavioral investigation in the cat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015;769:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.te Vruchte D, Galione A, Strupp M, Mann M. Effects of N-acetyl-leucine and its enantiomers in Niemann-Pick disease type C cells. BioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/826222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brandsch M, Knütter I, Bosse-Doenecke E. Pharmaceutical and pharmacological importance of peptide transporters. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2008;60:543–585. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.5.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poole RC, Halestrap AP. Transport of lactate and other monocarboxylates across mammalian plasma membranes. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:C761–782. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.4.C761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levy S, Kafri M, Carmi M, Barkai N. The competitive advantage of a dual-transporter system. Science. 2011;334:1408–1412. doi: 10.1126/science.1207154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pade V, Stavchansky S. Link between drug absorption solubility and permeability measurements in Caco-2 cells. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998;87:1604–1607. doi: 10.1021/js980111k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.VanWert AL, Gionfriddo MR, Sweet DH. Organic anion transporters: Discovery, pharmacology, regulation and roles in pathophysiology. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2010;31:1–71. doi: 10.1002/bdd.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vibert N, Vidal PP. In vitro effects of acetyl-DL-leucine (Tanganil) on central vestibular neurons and vestibulo-ocular networks of the guinea-pig. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;13:735–748. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2000.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kennedy BE, et al. Adaptations of energy metabolism associated with increased levels of mitochondrial cholesterol in Niemann-Pick type C1-deficient cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:16278–16289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.559914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jha MK, et al. Metabolic Connection of inflammatory pain: pivotal role of a pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-pyruvate dehydrogenase-lactic acid axis. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:14353–14369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1910-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oláh J, et al. Increased glucose metabolism and ATP level in brain tissue of Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. FEBS J. 2008;275:4740–4755. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun S, Li H, Chen J, Qian Q. Lactic acid: No longer an inert and end-product of glycolysis. Physiology. 2017;32:453–463. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00016.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patet C, Suys T, Carteron L, Oddo M. Cerebral lactate metabolism after traumatic brain injury. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2016;16:31. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0638-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hashimoto T, Hussien R, Oommen S, Gohil K, Brooks GA. Lactate sensitive transcription factor network in L6 cells: Activation of MCT1 and mitochondrial biogenesis. FASEB J. 2007;21:2602–2612. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8174com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weimer M, et al. The impact of data transformations on concentration-response modeling. Toxicol. Lett. 2012;213:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).