Abstract

Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) belonging to Amaranthaceae, is known as “the crop of the future” because of its incredible nutritional quality. Amaranthus spp. (> 70) have a huge diversity in terms of their plant morphology, production and nutritional quality; however, these species are not well characterized at molecular level due to unavailability of robust and reproducible molecular markers, which is essential for crop improvement programs. In the present study, 13,051 genome-wide microsatellite motifs were identified and subsequently utilized for marker development using A. hypochondriacus (L.) genome (JPXE01.1). Out of those, 1538 motifs were found with flanking sequences suitable for primer designing. Among designed primers, 225 were utilized for validation of which 119 (52.89%) primers were amplified. Cross-species transferability and evolutionary relatedness among ten species of Amaranthus (A. hypochondriacus, A. caudatus, A. retroflexus, A. cruentus, A. tricolor, A. lividus, A. hybridus, A. viridis, A. edulis, and A. dubius) were also studied using 45 microsatellite motifs. The maximum (86.67%) and minimum (28.89%) cross-species transferability were observed in A. caudatus and A. dubius, respectively, that indicated high variability present across the Amaranthus spp. Total 97 alleles were detected among 10 species of Amaranthus. The averages of major allele frequency, gene diversity, heterozygosity and PIC were 0.733, 0.347, 0.06, and 0.291, respectively. Nei’s genetic dissimilarity coefficients ranged from 0.0625 (between A. tricolor and A. hybridus) to 0.7918 (between A. viridis and A. lividus). The phylogenetic tree grouped ten species into three major clusters. Genome-wide development of microsatellite markers and their transferability revealed relationships among amaranth species which ultimately can be useful for species identification, DNA fingerprinting, and QTLs/gene(s) identification.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-021-02930-5.

Keywords: Genome-wide microsatellites, Amaranth, Cross-species transferability, Amaranthaceae, Marker development

Introduction

The amaranth belonging to genus Amaranthus possesses more than 70 species which are distributed across diverse climatic conditions worldwide. Due to huge diversity in the genome, chromosome number (2n) in Amaranthus species varies from 28 to 68 in the diploid/tetraploid form (Das 2016). Based on its utility and characteristics, amaranth can be categorized as grain amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus L., A. caudatus L., and A. cruentus L.), vegetable amaranth (A. tricolor L.) and weedy amaranth (A. spinosus L., A. viridis L., A. retroflexus L., A. graecizans L., A. dubius Mart. ex Thell. etc.). In addition to its utility as grain and vegetable, Amaranthus spp. (A. tricolor and A. caudatus) are also used as an ornamental plant due to presence of attractive inflorescence (Das 2016). Amaranth is known as a potential pseudo-cereal as its grains contain higher amount of protein, essential amino acid lysine, calcium and iron compared to cereals, gluten-free quality and bread making rheological properties (Bhat et al. 2015; Das 2016; Pagi et al. 2017). A seed of grain amaranth is on average composed of 13.1–21% of crude protein; 5.6–10.9% of crude fat; 48–69% of starch; 3.1–5% of dietary fiber and 2.5–4.4% of ash (Bhat et al. 2015). The total ‘protein package’ of amaranth grain is very close to the levels recommended by FAO/WHO (Das 2016). Because of its nutritional quality and adaptability against a wide range of climatic condition, amaranth is also known as “the crop of the future” or “third millennium grain” (Martinez-Lopez et al. 2020).

On the basis of in vitro and in vivo studies, it was suggested that Amaranthus spp. possess nutraceutical and various pharmacological properties due to the presence of active phytochemical constituents (Alegbejo 2013; Peter and Gandhi 2017; Martinez-Lopez et al. 2020). Therefore, the importance of amaranth has been increased in pharmaceutical, cosmetics, food, and agro industries (Alegbejo 2013; Das 2016; Peter and Gandhi 2017).

Worldwide, grain amaranth is cultivated as a crop in some countries, even so proper documentation for production and productivity is still not available (Coelho et al. 2018). India is a one of the leading countries where grain amaranth is cultivated as a sole crop (Martinez-Lopez et al. 2020). In India, many crop improvement activities, especially for improvement in amaranth productivity have been carried out that resulted in the release of some amaranth varieties in the past two decades (Dua et al. 2009). However, still there is a need to explore amaranth diversity to aid in crop improvement programs (Dharajiya et al. 2021). Molecular marker-based characterization of germplasms to utilize them in crop improvement is a rapid and reliable method.

These days, many of the molecular marker technologies have been standardized and frequently used for crop improvement programs (Gelotar et al. 2019). Among the available molecular markers, microsatellites or simple sequence repeats (SSRs) (1–6 bp tandem repeat DNA sequences) are the most promising for genomic applications as they are dispersed randomly and ubiquitously throughout the genome, highly reproducible, highly polymorphic, and co-dominant in nature (Parita et al. 2018; Chaudhari et al. 2019). Microsatellites represent hyper-variable regions of the genome that arise because of replication slippage or unequal crossing over resulting into differences in the copy number within repeat motifs (Chandra et al. 2011). However, the regions flanking microsatellites are conserved and can be used to design locus specific SSR markers. They are suitable for a wide range of applications like genetic mapping, fingerprinting, germplasm characterization, confirmation of hybrids and marker-assisted breeding (Dharajiya et al. 2020). These microsatellites need to be isolated de novo from the species or closely related species. Genome-wide identification and development of microsatellite markers can provide tremendous support for enhancing breeding efficiency of breeders by adopting molecular breeding approach (Dharajiya et al. 2020).

Genome sequence of amaranth is available at National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). This information can be utilized for the genome-wide discovery of microsatellites, which may further facilitate understanding evolutionary relationships, genetic diversity, and genomic texture of Amaranthus species. Considering the above important facts, we have identified and characterized genome-wide microsatellite markers in A. hypochondriacus genome, validated those developed microsatellite markers in A. hypochondriacus, and assessed cross-species transferability of validated microsatellite markers to evaluate genetic relatedness among ten species of Amaranthus.

Materials and methods

Genome-wide microsatellites mining

The amaranth (A. hypochondriacus) genome (JPXE01.1) in FASTA format was downloaded from the NCBI database. Microsatellite motifs (1–6) were identified and flanking regions were downloaded. From 257,456 FASTA sequences (152.6 Mb), genome-wide SSR motifs were identified using MISA (MIcroSAtellite identification tool) script (Thiel et al. 2003; Beier et al. 2017). The minimum repeat unit was defined ten for mono-nucleotide repeat (MNR), six for di-nucleotide repeat (DNR), and five for all other motifs, including tri-nucleotide repeat (TNR), tetra-nucleotide repeat (TtNR), penta-nucleotide repeat (PNR), and hexa-nucleotide repeat (HNR). Flanking regions of SSR motifs (excluding MNR) were downloaded in FASTA-format sequence file along with sequence contig ID and the sequence file was allowed to search for all possible combinations of DNR, TNR, TtNR, PNR, and HNR.

Using primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3), primers (forward and reverse) were designed with standard parameters (Untergasser et al. 2012). The most important parameters for primer designing were an optimal annealing temperature of 57 °C, a target amplicon size of 100–300 bp, GC content of 45–65%, and an optimal primer length of 20 bp. The data obtained were transferred to a Microsoft Excel worksheet for further analysis and characterization of microsatellites. Developed markers having designed primer pairs were localized on chromosomes of A. hypochondriacus genome (GCA_000753965.2) by KASPspoon ver. 5.18.2 software (Alsamman et al. 2019) using default parameters.

Validation of SSR motifs

Among the designed primers (Supplementary file 1), total 225 primers (Supplementary file 2) were selected from DNR, TNR, TtNR, PNR, and HNR. These primers were amplified in two A. hypochondriacus genotypes namely, IC-35476 and IC-35540 for the validation of SSRs. The genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from the collected leaf samples using the CTAB procedure with minor modifications (Doyle 1991). The PCR amplification for each microsatellite locus was performed according to protocols described by Chen et al. (1997) with slight modification. A total reaction volume of 20 µl containing 50 ng gDNA, 10 pmol of primer pair, 200 µM each of dNTPs (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 0.4 U of Kapa Taq DNA polymerase (Kapa Biosystems, USA), and 2 µl of 10× buffer B (Kapa Biosystems, USA) was used for PCR amplification. The amplification of 225 primers was performed using standard PCR conditions (initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52 °C to 60° for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 60 s in each cycle followed by final product extension at 72 °C for 10 min) using a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany). The amplified PCR products were separated on the 3.0% agarose gel and after completion of the electrophoretic run, the gel was carefully taken out of the unit and photographed using FluroChem FC2 gel documentation system (Alpha Innotech Corporation, USA). A set of ten polymorphic primers (AH-SSR-V-13, 14, 16, 26, 28, 30, 31, 37, 58, and 72) was further validated in a population of A. hypochondriacus containing 24 genotypes as per above-mentioned method.

Cross-species transferability and diversity analysis

Leaf samples from 20 genotypes belonging eleven species of amaranth were collected and utilized for gDNA extraction using the CTAB procedure with minor modifications (Doyle 1991). The PCR was performed as above-mentioned conditions and reaction composition with 45 SSRs primer pairs (Supplementary file 3). The amplified products were separated on the 3.0% agarose gel and image was captured. Due to the poor amplification in three genotypes, 17 genotypes representing ten species of Amaranthus (Table 1; Fig. 1) were utilized for further analysis. The presence and absence of amplicons were recorded and molecular weight was determined by comparing ladder DNA of 50 bp/100 bp (Bangalore Genei Pvt. Ltd., India). The amplification of primers in particular species was observed and cross-species transferability (%) for all the species was analyzed by following formula. Transferability (%) = (Total no. of primers amplified in particular species/Total no. of primers used in the study) × 100. The major allele frequency, total no. of alleles, gene diversity (He), heterozygosity (Ho), and polymorphism information content (PIC) were calculated by PowerMarker software version 3.25 (Liu and Muse 2005). The dendrogram was constructed using genetic distance (Nei 1983) and the neighbor-joining (NJ) method.

Table 1.

Amaranthus genotypes considered for the transferability and diversity analysis

| Sr. no | Genotype | Species | Collected from | Type of species | Chromosome no. (2n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IC-38191 | A. hypochondriacus | Shimla | Grain | 32 |

| 2 | IC-38222 | A. hypochondriacus | Shimla | Grain | 32 |

| 3 | IC-469679 | A. hybridus | Thrissur | Wild | 32 |

| 4 | EC-198120 | A. cruentus | Shimla | Grain | 34 |

| 5 | IC-536675 | A. tricolor | Thrissur | Ornamental/vegetable | 34 |

| 6 | IC-536720 | A. lividus | Thrissur | Vegetable | 34 |

| 7 | IC-469735 | A. lividus | Thrissur | Vegetable | 34 |

| 8 | IC-541382 | A. lividus | Thrissur | Vegetable | 34 |

| 9 | IC-35672 | A. caudatus | Shimla | Grain | 32 |

| 10 | IC-38181 | A. caudatus | Shimla | Grain | 32 |

| 11 | IC-38219 | A. edulis | Shimla | Grain | 32 |

| 12 | IC-381195 | A. edulis | Shimla | Grain | 32 |

| 13 | NIC-22568 | A. viridis | Shimla | Vegetable | 34 |

| 14 | NIC-22569 | A. viridis | Shimla | Vegetable | 34 |

| 15 | IC-551458 | A. dubius | Thrissur | Vegetable | 32 |

| 16 | IC-551464 | A. dubius | Thrissur | Vegetable | 32 |

| 17 | IC-258249 | A. retroflexus | Shimla | Wild | 32 |

Shimla: ICAR-NBPGR Regional Station, Phagli, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh

Thrissur: ICAR-NBPGR Regional Station, Vellanikkara, KAU post, Thrissur, Kerala

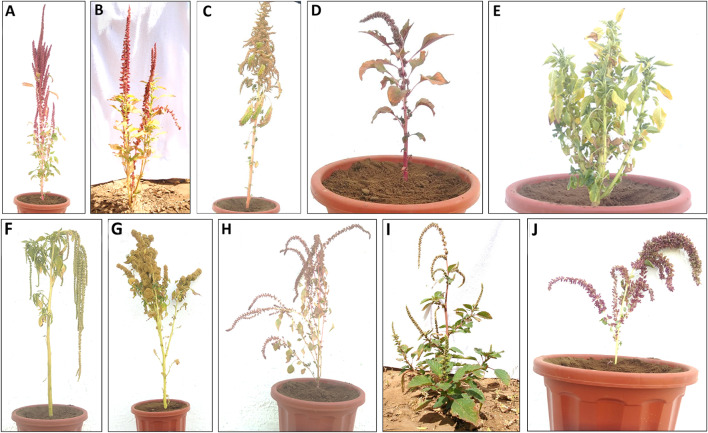

Fig. 1.

Amaranthus species used in the study. (Where, A A. hypochondriacus, B A. hybridus, C A. cruentus, D A. tricolor, E A. lividus, F A. caudatus, G A. edulis, H A. viridis, I A. dubius, and J A. retroflexus)

Results

Identification and characterization of microsatellite motifs

The identified motifs (13,051) were characterized as MNR, DNR, TNR, TtNR, PNR, and HNR based on the repeat unit length (Table 2). The most abundant repeat motif type was TNR (4319) followed by DNR (3939), MNR (2049), TtNR (1642), PNR (598), and HNR (504) representing 33.09%, 30.18%, 15.7%, 12.58%, 4.58%, and 3.86% of the total microsatellite motifs of A. hypochondriacus genome, respectively (Table 2). In A. hypochondriacus genome, on an average 14.25 microsatellite motifs/Mbp were found, among which TNR motifs (28.3 repeats/Mbp) were most abundant. The identified SSR motifs were also categorized on the basis of their repeat unit. AT (3502) was the most abundant followed by AAT (2256), A (1847) and ATC (1173) representing 26.83%, 17.29%, 14.15% and 8.99% of the total microsatellite motifs (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of microsatellite motifs identified in A. hypochondriacus genome

| Motif type | Motif code | Counts | Abundance (%) | Average length | Density (Counts/Mbp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono-nucleotide repeats | MNR | 2049 | 15.70 | 18.56 | 13.43 |

| Di-nucleotide repeats | DNR | 3939 | 30.18 | 20.92 | 25.81 |

| Tri-nucleotide repeats | TNR | 4319 | 33.09 | 18.82 | 28.30 |

| Tetra-nucleotide repeats | TtNR | 1642 | 12.58 | 18.83 | 10.76 |

| Penta-nucleotide repeats | PNR | 598 | 04.58 | 22.56 | 03.92 |

| Hexa-nucleotide repeats | HNR | 504 | 03.86 | 26.99 | 03.30 |

| Total | – | 13,051 | 100.0 | – | – |

| Average | – | – | 16.67 | 21.11 | 14.25 |

Table 3.

Most abundant microsatellite motifs in genome of A. hypochondriacus

| Motif sequence | Type of motif | Counts | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT | DNR | 3502 | 26.83 |

| AAT | TNR | 2256 | 17.29 |

| A | MNR | 1847 | 14.15 |

| ATC | TNR | 1173 | 8.99 |

| AAAT | TtNR | 944 | 7.23 |

| Others | – | 3329 | 25.51 |

| Total | – | 13,051 | – |

MNR mono-nucleotide repeats, DNR di-nucleotide repeats, TNR tri-nucleotide repeats, TtNR tetra-nucleotide repeats, PNR penta-nucleotide repeats, HNR hexa-nucleotide repeats

Out of total identified SSRs motif (13,051), 1538 motifs were found suitable for designing of primers from flanking region. Circos plot was generated to localize developed markers (1538) on chromosomes of A. hypochondriacus genome (Supplementary file 4). Among 1538 motifs, TNR (648) were most abundant motifs, followed by TtNR (451), DNR (212), PNR (128), and HNR (99) with representation of 42.13%, 29.32%, 13.78%, 8.32%, and 6.44% of total motifs, respectively (Table 4). The most abundant repeat motif(s) in DNR, TNR, TtNR, and PNR was AT/TA (161), AAT/ATT (127), AAAT/ATTT (95), and ATTTT/AAAAT (14), and AATATA, AGACAC, AGACAG, CTTTCC, GACACG (2), respectively (Table 4). However, in HNR, five motifs (AATATA, AGACAC, AGACAG, CTTTCC, and GACACG) were found abundant with equal frequency (two times each motif).

Table 4.

Characterization of microsatellite motifs used in primer designing

| Motif type | No | % | Motif sequence | No | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNR | 212 | 13.78 | AT/TA | 161 | 75.94 |

| TC/GA | 22 | 10.38 | |||

| AG/CT | 19 | 8.96 | |||

| TG/CA | 5 | 2.36 | |||

| AC/GT | 4 | 1.89 | |||

| Others | 1 | 0.47 | |||

| TNR | 648 | 42.13 | AAT/ATT | 127 | 19.6 |

| TAT/ATA | 105 | 16.2 | |||

| TAA/TTA | 83 | 12.81 | |||

| ATC/GAT | 49 | 7.56 | |||

| TGA/TCA | 47 | 7.25 | |||

| Others | 237 | 36.57 | |||

| TtNR | 451 | 29.32 | AAAT/ATTT | 95 | 21.06 |

| TTTA/TAAA | 58 | 12.86 | |||

| AATA/TATT | 53 | 11.75 | |||

| TTAT/ATAA | 53 | 11.75 | |||

| TTAA | 25 | 5.54 | |||

| Others | 167 | 37.03 | |||

| PNR | 128 | 8.32 | ATTTT/AAAAT | 14 | 10.94 |

| AATAA/TTATT | 7 | 5.47 | |||

| TATTT/AAATA | 6 | 4.69 | |||

| ATAAA/TTTAT | 5 | 3.91 | |||

| AAATT/AATTT | 5 | 3.91 | |||

| Others | 91 | 71.09 | |||

| HNR | 99 | 6.44 | AATATA | 2 | 2.02 |

| AGACAC | 2 | 2.02 | |||

| AGACAG | 2 | 2.02 | |||

| CTTTCC | 2 | 2.02 | |||

| GACACG | 2 | 2.02 | |||

| Others | 89 | 89.9 | |||

| Total | 1538 | – | – | 1538 | – |

DNR Di-nucleotide repeats, TNR Tri-nucleotide repeats, TtNR Tetra-nucleotide repeats, PNR Penta-nucleotide repeats, HNR Hexa-nucleotide repeats

Validation of microsatellite motifs

Total 119 primer pairs (52.89%) were amplified (with corresponding expected amplicon size) among 225 primer pairs used from developed primers. Circos plot was generated to localize validated markers (225) on chromosomes of A. hypochondiacus genome (Supplementary file 5). The validation of ten polymorphic primers in A. hypochondriacus population resulted in amplification of all the primers across the population with the total of 22 alleles and average of 2.2 alleles per primer (Supplementary file 6).

Cross-species transferability and genetic diversity analysis

Among the validated primers, 45 primers were utilized in the cross-species transferability and diversity analysis among 10 Amaranthus species (Supplementary file 7). Out of 45 primers, 12 were monomorphic and 33 were polymorphic across all the species used in the study. Polymorphic loci (33) yielded 85 alleles with an average of 2.57 alleles/locus. Among the primers utilized in transferability study, four primers viz., AH-SSR-V-30 (6), AH-SSR-V-61 (5), AH-SSR-V-26 (4) and AH-SSR-V-70 (4) produced more than three alleles per primer whereas eight primers, namely AH-SSR-V-28, AH-SSR-V-43, AH-SSR-V-118, AH-SSR-V-159, AH-SSR-V-180, AH-SSR-V-184, AH-SSR-V-185, AH-SSR-V-186, produced three alleles. The major allele frequency, gene diversity, heterozygosity and PIC ranged from 0.423 to 1, 0 to 0.694, 0 to 0.692, and 0 to 0.645, respectively. The averages of major allele frequency, gene diversity, heterozygosity and PIC were 0.733, 0.347, 0.06, and 0.291, respectively (Table 5). The primer AH-SSR-V-61 produced maximum PIC (0.645) followed by AH-SSR-V-26 (0.641), AH-SSR-V-30 (0.589), AH-SSR-V-43 (0.555), AH-SSR-V-159 (0.555), AH-SSR-V-186 (0.548), and AH-SSR-V-184 (0.546).

Table 5.

Description and variability parameters of primers used in transferability study

| Primer name | MAF | NA | NPA | He | Ho | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH-SSR-V-12 | 0.692 | 2 | 2 | 0.426 | 0.000 | 0.335 |

| AH-SSR-V-13 | 0.591 | 2 | 2 | 0.483 | 0.091 | 0.367 |

| AH-SSR-V-14 | 0.625 | 2 | 2 | 0.469 | 0.000 | 0.359 |

| AH-SSR-V-20 | 0.667 | 2 | 2 | 0.444 | 0.000 | 0.346 |

| AH-SSR-V-23 | 0.773 | 2 | 2 | 0.351 | 0.091 | 0.290 |

| AH-SSR-V-25 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-26 | 0.429 | 4 | 4 | 0.694 | 0.000 | 0.641 |

| AH-SSR-V-27 | 0.600 | 2 | 2 | 0.480 | 0.000 | 0.365 |

| AH-SSR-V-28 | 0.615 | 3 | 3 | 0.544 | 0.000 | 0.484 |

| AH-SSR-V-29 | 0.650 | 2 | 2 | 0.455 | 0.100 | 0.351 |

| AH-SSR-V-30 | 0.588 | 6 | 6 | 0.616 | 0.118 | 0.589 |

| AH-SSR-V-32 | 0.556 | 2 | 2 | 0.494 | 0.000 | 0.372 |

| AH-SSR-V-37 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-43 | 0.500 | 3 | 3 | 0.625 | 0.000 | 0.555 |

| AH-SSR-V-44 | 0.875 | 2 | 2 | 0.219 | 0.250 | 0.195 |

| AH-SSR-V-53 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-58 | 0.500 | 2 | 2 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.375 |

| AH-SSR-V-61 | 0.500 | 5 | 5 | 0.682 | 0.636 | 0.645 |

| AH-SSR-V-62 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-63 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-64 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-67 | 0.750 | 2 | 2 | 0.375 | 0.000 | 0.305 |

| AH-SSR-V-68 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-70 | 0.706 | 4 | 4 | 0.465 | 0.059 | 0.429 |

| AH-SSR-V-87 | 0.750 | 2 | 2 | 0.375 | 0.000 | 0.305 |

| AH-SSR-V-92 | 0.500 | 2 | 2 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.375 |

| AH-SSR-V-118 | 0.423 | 3 | 3 | 0.648 | 0.692 | 0.573 |

| AH-SSR-V-119 | 0.600 | 2 | 2 | 0.480 | 0.000 | 0.365 |

| AH-SSR-V-121 | 0.750 | 2 | 2 | 0.375 | 0.500 | 0.305 |

| AH-SSR-V-135 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-138 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-140 | 0.625 | 2 | 2 | 0.469 | 0.000 | 0.359 |

| AH-SSR-V-142 | 0.857 | 2 | 2 | 0.245 | 0.000 | 0.215 |

| AH-SSR-V-152 | 0.967 | 2 | 2 | 0.064 | 0.067 | 0.062 |

| AH-SSR-V-159 | 0.500 | 3 | 3 | 0.625 | 0.000 | 0.555 |

| AH-SSR-V-161 | 0.714 | 2 | 2 | 0.408 | 0.000 | 0.325 |

| AH-SSR-V-162 | 0.733 | 2 | 2 | 0.391 | 0.000 | 0.315 |

| AH-SSR-V-168 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-178 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-179 | 1.000 | 1 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| AH-SSR-V-180 | 0.636 | 3 | 3 | 0.529 | 0.000 | 0.473 |

| AH-SSR-V-184 | 0.471 | 3 | 3 | 0.623 | 0.118 | 0.546 |

| AH-SSR-V-185 | 0.667 | 3 | 3 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.449 |

| AH-SSR-V-186 | 0.500 | 3 | 3 | 0.620 | 0.000 | 0.548 |

| AH-SSR-V-187 | 0.667 | 2 | 2 | 0.444 | 0.000 | 0.346 |

| Total | – | 97 | 85 | – | – | – |

| Mean | 0.733 | 2.16 | 1.89 | 0.347 | 0.060 | 0.291 |

Mean % polymorphism: 73.33

MAF, major allele frequency; NA, total alleles; NPA, polymorphic alleles; He, gene diversity; Ho, heterozygosity; PIC, polymorphism information content

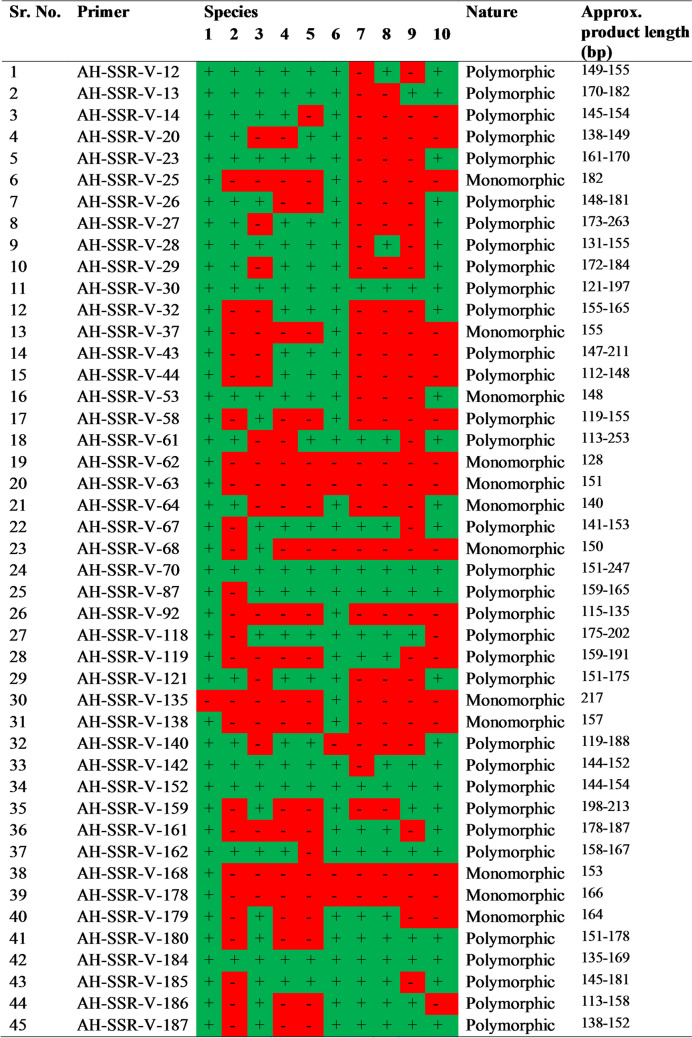

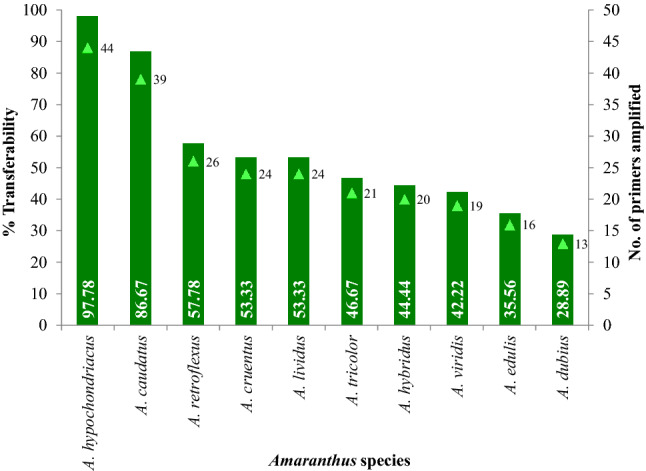

The maximum and minimum amplification of SSRs was observed in A. hypochondriacus and A. dubius, respectively (Fig. 2). Hence, the maximum cross-species transferability of SSRs was detected in A. caudatus (86.67%), followed by A. retroflexus (57.78%), A. cruentus (53.33%), A. lividus (53.33%), A. tricolor (46.67%), A. hybridus (44.44%), A. viridis (42.22%), A. edulis (35.56%), and A. dubius (28.89%) (Fig. 2). The detailed result of cross-species transferability is shown in Fig. 3. The difference in the amplicon size was also observed across the species. By considering the average length of amplicons/SSRs, maximum length was reported in A. hypochondriacus and A. caudatus followed by A. cruentus, A. lividus, A. retroflexus, A. hybridus, A. viridis, A. tricolor, A. dubius, and A. edulis.

Fig. 2.

Cross-species transferability of microsatellites developed from A. hypochondriacus

Fig. 3.

Cross-species amplification of 45 microsatellites validated and developed from A. hypochondriacus (Where, + in green color: amplification; − in red color: no amplification; 1: A. hypochondriacus, 2: A. hybridus, 3: A. cruentus, 4: A. tricolor, 5: A. lividus, 6: A. caudatus, 7: A. edulis, 8: A. viridis, 9: A. dubius, and 10: A. retroflexus)

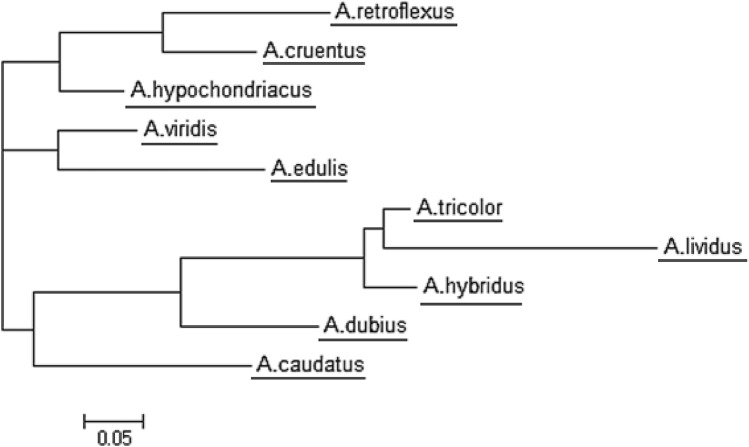

Total 97 alleles were used to assess genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships among 10 species of Amaranthus. Nei’s genetic dissimilarity coefficients (Nei 1983) ranged from 0.0625 (between A. tricolor and A. hybridus) to 0.7918 (between A. viridis and A. lividus). The phylogenetic tree was constructed to evaluate and understand evolutionary relationships among Amaranthus species. The phylogenetic tree grouped ten species into three major clusters (Fig. 4). The cluster I contained two species, namely A. viridis (vegetable) and A. edulis (grain). The cluster II contained three species viz., A. retroflexus (wild-ancestor of grain species), A. cruentus (grain), and A. hypochondriacus (grain). The cluster III possessed three vegetable species (A. tricolor, A. lividus, and A. dubius), A. hybridus (wild), and A. caudatus (grain). The results indicated that species A. hybridus and A. tricolor possessed maximum similarity, whereas A. viridis and A. lividus were most diverse species.

Fig. 4.

Dendrogram of Amaranthus species based on microsatellite markers

Discussion

Among various molecular markers used in determining evolutionary relationships in plants, microsatellites have attracted plant breeders due to several desired genetic characteristics (Kalia et al. 2011). The Amaranthus genus has extensive morphological diversity among and even within species. Moreover, there is the existence of different theories of evolutionary relations of grain amaranth and other amaranth species which created confusion that can be solved by evaluating genetic diversity analysis, preferably with molecular markers (SSRs, SNPs etc.). Genome-wide microsatellite markers can be very helpful in plant breeding due to their extensive abundance and genome coverage. Despite of the availability of genome sequences of A. hypochondriacus (Sunil et al. 2014; Clouse et al. 2016) and A. tuberculatus (Lee et al. 2009), there are no reports on development of genome-wide microsatellites in amaranth.

The most frequent repeat motif type in A. hypochondriacus genome was TNR. The TNRs as the most frequent SSRs have been already reported in other plants namely, Brachypodium spp. (Sonah et al. 2011), foxtail millet (Pandey et al. 2013), and Opium poppy (Celik et al. 2014). In A. hypochondriacus genome, the most prevalent repeat motif was AT followed by AAT. Similar patterns of SSRs prevalence has been also reported in Nicotiana spp. (Wang et al. 2018) and sorghum (Yonemaru et al. 2009). The validation of SSR markers in A. hypochondriacus population indicated their robustness in their application in amaranth.

The average alleles amplified per polymorphic motif were 2.57 with the maximum number of six alleles. The larger number of alleles in the marker is a promising sign for its utility. These primers can be useful in the molecular studies among Amaranthus spp. The major allele frequency, gene diversity, heterozygosity and PIC found in the present study are closer to previously published studies (Mallory et al. 2008; He and Park 2013; Wang and Park 2013; Suresh et al. 2014; Nguyen et al. 2019). In the present study, PIC values ranged from 0 to 0.64 which indicated that some loci are monomorphic and some loci are highly polymorphic which are capable to distinguish amaranth genotypes.

Genome-wide microsatellite markers have been developed and their cross-species/genera transferability has been previously reported in many plant species (Xiao et al. 2016; Kaldate et al. 2017; Dharajiya et al. 2020), but this is the first time, large no. of genome-wide SSR markers were developed in amaranth and their cross-species transferability was studied in ten Amaranthus spp. Cross-species transferability of genome-wide SSR markers ranged from 86.67 to 28.89% indicating extensive variability present across the amaranth species. In the past, cross-species transferability of genome-wide SSRs has been studied in other crops like, melon (Zhu et al. 2016), black pepper (Kumari et al. 2019), and lentil (Singh et al. 2020) with a wide range of transferability. The amplification of microsatellite markers indicated that flanking regions of amplified microsatellite motifs are conserved across Amaranthus spp.

The rates of variations in microsatellites are known to be more common as compared to the other regions of the genome and the repeat motif length has higher possibility to gain in size over losses in plants (Udupa and Baum 2001; Li et al. 2002). It has been reported that the cultivated rice (O. sativa L.) has higher number of repeats/molecular weight than the wild type (O. rufipogon) (Wang et al. 2008). Similarly, the higher average length of amplicons in A. hypochondriacus and A. cruentus as compared to that of A. retroflexus was observed. Moreover, A. retroflexus, A. cruentus, and A. hypochondriacus were also grouped in the same cluster. Hence, the results indicated that these grain (cultivated) species might have been evolved from A. retroflexus (wild). In past study, the number of repeats has been used in determining the evolutionary relationships in rice (Tiwari et al. 2014).

The results of genetic diversity analysis indicated that species A. hybridus and A. tricolor possessed maximum similarity whereas A. viridis and A. lividus were most diverse species. The phylogenetic tree grouped ten species into three major clusters. In the present study, A. viridis (vegetable) and A. edulis (wild) were grouped in the same cluster. A. retroflexus (wild), A. cruentus (grain), and A. hypochondriacus (grain) were in the same group indicating more genetic similarity. Suresh et al. (2014) analyzed genetic diversity among different Amaranthus spp. using eleven SSR markers and observed the similar pattern of clustering. In the present study, A. tricolor (vegetable), A. lividus (vegetable), A. dubius (vegetable), A. hybridus (wild), and A. caudatus (grain) were in the same cluster. Similarly, A. tricolor, A. hybridus, and A. caudatus are grouped in same cluster using 14 SSR markers (Oo and Park 2013). Among grain Amaranthus spp., A. caudatus grouped in different cluster, while A. cruentus and A. hypochondriacus grouped in same cluster. This is in agreement with the conclusion of Stetter et al. (2017) that A. caudatus is resulted from partial domestication from A. hybridus with gene flow from A. quitensis. It has been reported that A. cruentus and A. hypochondriacus could be domesticated from different geographical isolates of A. hybridus (Stetter and Schmid 2017; Viljoen et al. 2018). Our results were also supported by Suresh et al. (2014), where above-mentioned vegetable species were grouped in the same cluster. A. tricolor and A. lividus were grouped in the same cluster (Khaing et al. 2013). However, A. hybridus (wild) and A. caudatus (grain) were grouped in different cluster (Suresh et al. 2014). Variation in clustering might be possible due to use of different and less no. of SSR markers in previous study (Suresh et al. 2014). The species exhibiting similar morphological characters were categorized in the same cluster, which might be due to the similarity in the SSR loci from the time of evolutionary divergence.

Conclusion

By genome mining for microsatellites, 13,051 microsatellite motifs were identified and used for primer designing. Among designed primers (1538), 225 primers were validated in A. hypochondriacus and a large number of primers (119) were amplified. Cross-species transferability and evolutionary relatedness among ten species of Amaranthus were studied using 45 microsatellite motifs. Genome-wide development of SSR markers, their transferability, and relationships among species will be useful for identification of species, identification of QTLs, tagging of gene(s), marker-assisted breeding, confirmation of hybrids, etc., in vegetable, grain, ornamental, and wild species of amaranth.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the authorities of C. P. College of Agriculture, SDAU, Sardarkrushinagar, Gujarat, India, to avail facilities to conduct the research. The authors are also thankful to the Gujarat State Biotechnology Mission (GSBTM), Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, India for the financial assistance.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: KKT, NNP, MPP; Methodology: KKT, NNP, MPP; Formal analysis and investigation: NJT, DTD, HLB, PPB, BPG; Writing—original draft preparation: KKT, DTD; Writing—review and editing: KKT, DTD, NNP, MPP, SDS; Funding acquisition: KKT; Resources: NNP, MPP, SDS; Supervision: KKT, NNP, MPP, SDS.

Funding

The funding was provided by Gujarat State Biotechnology Mission (GSBTM), Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India (Grant no. 1362).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- Alegbejo JO. Nutritional value and utilization of Amaranthus (Amaranthus spp.)–a review. Bayero J Pure Appl Sci. 2013;6(1):136–143. doi: 10.4314/bajopas.v6i1.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alsamman AM, Ibrahim SD, Hamwieh A. KASPspoon: an in vitro and in silico PCR analysis tool for high-throughput SNP genotyping. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(17):3187–3190. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier S, Thiel T, Münch T, Scholz U, Mascher M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(16):2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A, Satpathy G, Gupta RK. Evaluation of nutraceutical properties of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. grains and formulation of value added cookies. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2015;3(5):51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Celik I, Gultekin V, Allamer J, Doganlar S, Frary A. Development of genomic simple sequence repeat markers in opium poppy by next-generation sequencing. Mol Breed. 2014;34(2):323. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0036-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Tiwari KK, Nagaich D, Dubey N, Kumar S, Roy AK. Development and characterization of microsatellite markers from tropical forage Stylosanthes species and analysis of genetic variability and cross-species transferability. Genome. 2011;54(12):1016–1028. doi: 10.1139/g11-064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari BA, Patel MP, Dharajiya DT, Tiwari KK. Assessment of genetic diversity in castor (Ricinus communis L.) using microsatellite markers. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia. 2019;16(1):61–69. doi: 10.13005/bbra/2721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Temnykh S, Xu Y, Cho YG, McCouch SR. Development of a microsatellite framework map providing genome-wide coverage in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Theor Appl Genet. 1997;95(4):553–567. doi: 10.1007/s001220050596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse JW, Adhikary D, Page JT, Ramaraj T, Deyholos MK, Udall JA, Fairbanks DJ, Jellen EN, Maughan PJ. The amaranth genome: genome, transcriptome, and physical map assembly. The Plant Genome. 2016;9(1):1–14. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2015.07.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho LM, Silva PM, Martins JT, Pinheiro AC, Vicente AA. Emerging opportunities in exploring the nutritional/functional value of amaranth. Food Funct. 2018;9(11):5499–5512. doi: 10.1039/C8FO01422A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S. Amaranthus: A promising crop of future. Singapore: Springer; 2016. p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Dharajiya DT, Shah A, Galvadiya BP, Patel MP, Srivastava R, Pagi NK, Solanki SD, Parida SK, Tiwari KK. Genome-wide microsatellite markers in castor (Ricinus communis L.): Identification, development, characterization, and transferability in Euphorbiaceae. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;151:112461. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dharajiya DT, Singh AK, Tiwari KK, Prajapati NN. Genetic diversity in amaranth and its close relatives. In: Adhikary D, Deyholos MK, Délano-Frier JP, editors. The amaranth genome. Compendium of plant genomes. Cham: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. Molecular techniques in taxonomy. Berlin: Springer; 1991. DNA protocols for plants; pp. 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Dua RP, Raiger HL, Phogat BS, Sharma SK. Underutilized crops: improved varieties and cultivation practices. New Delhi: NBPGR; 2009. p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Gelotar MJ, Dharajiya DT, Solanki SD, Prajapati NN, Tiwari KK. Genetic diversity analysis and molecular characterization of grain amaranth genotypes using inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2019;43(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s42269-019-0146-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Park YJ. Evaluation of genetic structure of amaranth accessions from the United States. Weed Turf Sci. 2013;2(3):230–235. doi: 10.5660/WTS.2013.2.3.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldate R, Rana M, Sharma V, Hirakawa H, Kumar R, Singh G, Chahota RK, Isobe SN, Sharma TR. Development of genome-wide SSR markers in horsegram and their use for genetic diversity and cross-transferability analysis. Mol Breed. 2017;37(8):103. doi: 10.1007/s11032-017-0701-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia RK, Rai MK, Kalia S, Singh R, Dhawan AK. Microsatellite markers: an overview of the recent progress in plants. Euphytica. 2011;177(3):309–334. doi: 10.1007/s10681-010-0286-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khaing AA, Moe KT, Chung JW, Baek HJ, Park YJ. Genetic diversity and population structure of the selected core set in Amaranthus using SSR markers. Plant Breed. 2013;132(2):165–173. doi: 10.1111/pbr.12027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R, Wankhede DP, Bajpai A, Maurya A, Prasad K, Gautam D, Rangan P, Latha M, John KJ, Bhat KV, Gaikwad AB. Genome wide identification and characterization of microsatellite markers in black pepper (Piper nigrum): a valuable resource for boosting genomics applications. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0226002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Thimmapuram J, Thinglum KA, Gong G, Hernandez AG, Wright CL, Kim RW, Mikel MA, Tranel PJ. Sampling the waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus) genome using pyrosequencing technology. Weed Sci. 2009;57(5):463–469. doi: 10.1614/WS-09-021.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Korol AB, Fahima T, Beiles A, Nevo E. Microsatellites: genomic distribution, putative functions and mutational mechanisms: a review. Mol Ecol. 2002;11(12):2453–2465. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Muse SV. PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):2128–2129. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory MA, Hall RV, McNabb AR, Pratt DB, Jellen EN, Maughan PJ. Development and characterization of microsatellite markers for the grain amaranths. Crop Sci. 2008;48(3):1098–1106. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2007.08.0457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Lopez A, Millan-Linares MC, Rodriguez-Martin NM, Millan F, Montserrat Paz S. Nutraceutical value of kiwicha (Amaranthus caudatus L.) J Funct Foods. 2020;65:103735. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Tajima F, Tateno Y. Accuracy of estimated phylogenetic trees from molecular data. J Mol Evol. 1983;19(2):153–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02300753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DC, Tran DS, Tran T, Ohsawa R, Yoshioka Y. Genetic diversity of leafy amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor L.) resources in Vietnam. Breed Sci. 2019;69(4):640–650. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.19050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oo WH, Park YJ. Analysis of the genetic diversity and population structure of amaranth accessions from South America using 14 SSR markers. Korean J Crop Sci. 2013;58(4):336–346. doi: 10.7740/kjcs.2013.58.4.336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pagi N, Prajapati N, Pachchigar K, Dharajiya D, Solanki SD, Soni N, Patel P. GGE biplot analysis for yield performance of grain amaranth genotypes across different environments in western India. J Exp Biol Agric Sci. 2017;5(3):368–376. doi: 10.18006/2017.5(3).368.376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey G, Misra G, Kumari K, Gupta S, Parida SK, Chattopadhyay D, Prasad M. Genome-wide development and use of microsatellite markers for large-scale genotyping applications in foxtail millet [Setaria italica (L.)] DNA Res. 2013;20(2):197–207. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parita B, Kumar SN, Darshan D, Karen P. Elucidation of genetic diversity among ashwagandha [Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal] genotypes using EST-SSR markers. Res J Biotechnol. 2018;13(10):52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Peter K, Gandhi P. Rediscovering the therapeutic potential of Amaranthus species: a review. Egypt J Basic Appl Sci. 2017;4(3):196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbas.2017.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Singh CK, Tribuvan KU, Tyagi P, Taunk J, Tomar RSS, Kumari S, Tripathi K, Kumar A, Gaikwad K, Yadav RK. Development, characterization, and cross species/genera transferability of novel EST-SSR markers in lentil, with their molecular applications. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2020;38(1):114–129. doi: 10.1007/s11105-019-01184-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonah H, Deshmukh RK, Sharma A, Singh VP, Gupta DK, Gacche RN, Rana JC, Singh NK, Sharma TR. Genome-wide distribution and organization of microsatellites in plants: an insight into marker development in Brachypodium. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e21298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetter MG, Schmid KJ. Analysis of phylogenetic relationships and genome size evolution of the Amaranthus genus using GBS indicates the ancestors of an ancient crop. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;109:80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetter MG, Müller T, Schmid KJ. Genomic and phenotypic evidence for an incomplete domestication of South American grain amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus) Mol Ecol. 2017;26(3):871–886. doi: 10.1111/mec.13974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunil M, Hariharan AK, Nayak S, Gupta S, Nambisan SR, Gupta RP, Panda B, Choudhary B, Srinivasan S. The draft genome and transcriptome of Amaranthus hypochondriacus: a C4 dicot producing high-lysine edible pseudo-cereal. DNA Res. 2014;21(6):585–602. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsu021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh S, Chung JW, Cho GT, Sung JS, Park JH, Gwag JG, Baek HJ. Analysis of molecular genetic diversity and population structure in Amaranthus germplasm using SSR markers. Plant Biosyst. 2014;148(4):635–644. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2013.788095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney R, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2003;106(3):411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari KK, Pattnaik S, Singh A, Sandhu M, Mithra SA, Abdin MZ, Singh AK, Mohapatra T. Allelic variation in the microsatellite marker locus RM6100 linked to fertility restoration of WA based male sterility in rice. Indian J Genet. 2014;74(4):409–413. doi: 10.5958/0975-6906.2014.00863.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udupa S, Baum M. High mutation rate and mutational bias at (TAA)n microsatellite loci in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Mol Genet Genom. 2001;265(6):1097–1103. doi: 10.1007/s004380100508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):e115–e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen E, Odeny DA, Coetzee MP, Berger DK, Rees DJ. Application of chloroplast phylogenomics to resolve species relationships within the plant genus Amaranthus. J Mol Evol. 2018;86(3):216–239. doi: 10.1007/s00239-018-9837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XQ, Park YJ. Comparison of genetic diversity among amaranth accessions from South and Southeast Asia using SSR markers. Korean J Med Crop Sci. 2013;21(3):220–228. doi: 10.7783/KJMCS.2013.21.3.220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MX, Zhang HL, Zhang DL, Qi YW, Fan ZL, Li DY, Pan DJ, Cao YS, Qiu ZE, Yu P, Yang QW, Wang XK, Li ZC. Genetic structure of Oryza rufipogon Griff. China Heredity. 2008;101(6):527–535. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2008.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yang S, Chen Y, Zhang S, Zhao Q, Li M, Gao Y, Yang L, Bennetzen JL. Comparative genome-wide characterization leading to simple sequence repeat marker development for Nicotiana. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):500. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4878-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Xia W, Ma J, Mason AS, Fan H, Shi P, Lei X, Ma Z, Peng M. Genome-wide identification and transferability of microsatellite markers between Palmae species. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1578. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.