Key Points

Question

What is the diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopic structures and patterns used in melanoma detection?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 studies including 22 796 skin lesions and 5736 melanomas, the structures with the highest sensitivity were irregular pigmentation (62%) and blue-white veil (61%), and the structures with highest specificity were pseudopods (97%) and shiny white structures (94%). Shiny white structures, pseudopods, irregular pigmentation, blue-white veil, and peppering were associated with the highest risk of melanoma.

Meaning

The findings of this study support the diagnostic importance of dermoscopic structures associated with melanoma detection and the importance of the overall pattern organization, suggesting a hierarchy in the significance of structures and patterns.

Abstract

Importance

Dermoscopy increases the diagnostic accuracy for melanoma. However, the accuracy of individual structures and patterns used in melanoma detection has not been systematically evaluated.

Objective

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of individual dermoscopic structures and patterns used in melanoma detection.

Data Sources

A search of Ovid Medline, Embase, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus, and Web of Science was conducted from inception to July 2020.

Study Selection

Studies evaluating the dermoscopic structures and patterns among melanomas in comparison with nonmelanoma lesions were included. Excluded were studies with fewer than 3 patients, studies in languages other than English or Spanish, studies not reporting dermoscopic structures per lesion type, and studies assessing only nail, mucosal, acral, facial, or metastatic melanomas or melanomas on chronically sun-damaged skin. Multiple reviewers applied these criteria, and 0.7% of studies met selection criteria.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses reporting guideline and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline were followed. Guidelines were applied via independent extraction by multiple observers. Data were pooled using a random-effects model.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The prespecified outcome measures were diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity) and risk (odds ratio [OR]) of melanoma for the following dermoscopic structures/patterns: atypical dots/globules, atypical network, blue-white veil, negative network, off-centered blotch, peripheral-tan structureless areas, atypical vessels (eg, linear irregular, polymorphous), pseudopods, streaks, regression (ie, peppering, scarlike areas), shiny white structures, angulated lines, irregular pigmentation, and a multicomponent pattern.

Results

A total of 40 studies including 22 796 skin lesions and 5736 melanomas were evaluated. The structures and patterns with the highest ORs were shiny white structures (OR, 6.7; 95% CI, 2.5-17.9), pseudopods (OR, 6.7; 95% CI, 2.7-16.1), irregular pigmentation (OR, 6.4; 95% CI, 2.0-20.5), blue-white veil (OR, 6.3; 95% CI, 3.7-10.7), and peppering (OR, 6.3; 95% CI, 2.4-16.1). The structures with the highest specificity were pseudopods (97.3%; 95% CI, 94.3%-98.7%), shiny white structures (93.6%; 95% CI, 85.6%-97.3%), peppering (93.4%; 95% CI, 81.9%-97.8%), and streaks (92.1%; 95% CI, 88.4%-94.7%), whereas features with the highest sensitivity were irregular pigmentation (62.3%; 95% CI, 31.2%-85.8%), blue-white veil (60.6%; 95% CI, 46.7%-72.9%), atypical network (56.8%; 95% CI, 43.6%-69.2%), and a multicomponent pattern (53.7%; 95% CI, 40.4%-66.4%).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis support the diagnostic importance of dermoscopic structures associated with melanoma detection (eg, shiny white structures, blue-white veil), further corroborate the importance of the overall pattern, and may suggest a hierarchy in the significance of these structures and patterns.

This systematic review and meta-analysis assesses the diagnostic accuracy of individual dermoscopic structures and patterns, as defined by standardized dermoscopy terminology, used in melanoma detection.

Introduction

Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer in the US and is responsible for most skin cancer–related deaths.1 Although therapeutic advances for the treatment of melanoma have been made, prevention and early detection remain the most cost-effective methods to decrease mortality.2,3 Dermoscopy is a noninvasive technique that allows for the visualization of subsurface skin structures otherwise invisible to the naked eye. It is well established that dermoscopy increases the diagnostic accuracy (DA) for melanoma, and its use is recommended by several skin cancer screening guidelines.4,5,6 Studies have evaluated the DA of dermoscopic algorithms and structures with high specificity for melanoma7,8,9,10; however, to date, existing knowledge has not been systematically evaluated and synthesized. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the DA of individual dermoscopic structures and patterns, as defined by standardized dermoscopy terminology, used in melanoma detection.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the DA of dermoscopic structures and patterns used in melanoma detection. The systematic review was conducted with guidance from the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews Manual,11 and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guideline checklists. It was critically appraised using the AMSTAR-2 tool for systematic reviews including randomized and nonrandomized studies of health care interventions.12,13,14

Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed by an academic health science librarian (J.M.R.) in consultation with the research team (N.M.W., N.J.) and was reviewed by a medical librarian using the Peer Review for Electronic Search Strategies tool.15 The search strategy was written for Ovid Medline and translated using each database’s syntax, controlled vocabulary, and search fields. MeSH terms, Emtree terms, and text words were used for dermoscopy and melanoma and their synonyms. We searched Ovid Medline (Including Epub-Ahead-of-Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily), Embase (Elsevier, Embase.com), Cochrane CENTRAL (Cochrane Library, Wiley), Scopus (Elsevier), and the Web of Science platform (Clarivate: Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Social Science & Humanities, Emerging Sources Citation Index, BIOSIS Citation Index, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Russian Science Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index, Zoological Record). We also searched trials registries Clinicaltrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform for trials with reported results. Furthermore, we reviewed the studies included in systematic reviews on related topics.16,17 No language, date, or other limits were applied. All databases were searched between July 13 and 16, 2020. Full search strategies are given in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement. All database records were downloaded to EndNote X9 (Clarivate) and uploaded to web-based software for deduplication, screening, and full-text evaluation (Covidence; Veritas Health Innovation). We did not contact any study authors, manufacturers, or other experts. The Retraction Watch database and journal websites were checked for retractions of included studies. Full citations of included studies can be found in eAppendix 2 in the Supplement and excluded studies with reason for exclusion can be found in eAppendix 3 in the Supplement.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies evaluating dermoscopic structures and patterns used in melanoma detection in patients of all ages, ethnicities, and skin types were included. Studies were required to document the frequency of at least 1 structure and/or pattern used in melanoma detection in comparison with other benign or malignant nonmelanoma lesions (eg, nevi, seborrheic keratoses, and keratinocyte carcinomas). Studies were required to provide data that allowed for the calculation of an odds ratio (OR) or DA (sensitivity and specificity) of each dermoscopic structure or pattern. Excluded were studies with fewer than 3 patients, studies in languages other than English or Spanish, studies that did not report dermoscopic structures independently, and studies assessing only nail, mucosal, acral, facial, or metastatic melanomas or melanomas on chronically sun-damaged skin.

The primary outcome measure was the DA of the following structures or patterns: atypical dots and/or globules, atypical network, angulated lines, blue-white veil, negative network, off-centered blotch, peripheral-tan structureless area, atypical vessels (eg, polymorphous, linear irregular), pseudopods, streaks, regression structures (scarlike areas, peppering/granularity), shiny white structures, irregular pigmentation, and multicomponent pattern. Given the variability of terminology with dermoscopy, only features with identical vocabulary or synonymous descriptors were included (Table 1). In ambiguous cases, the standardized dermoscopy terminology study by Kittler et al18 was referenced.

Table 1. Definitions of Melanoma-Specific Patterns and Structures18.

| Melanoma-specific structure (metaphoric terminology) | Definition | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Atypical dots and/or globules | Atypical dots: brown to black round structures (<0.1 mm in diameter) that are distributed in any distribution other than the center of the lesion or on the network lines. Atypical globules: round to oval-shaped pigmented clods (>0.1 mm in diameter) with variability in color, size, shape, or spacing, and distributed in an asymmetric fashion. | While atypical dots and globules can be assessed independently, the majority of studies in this analysis combined the structures into 1 group. |

| Atypical network | Gridlike pattern consisting of interconnecting pigmented lines surrounding hypopigmented holes. Lines are of differing colors, thicknesses, and spacing; there is asymmetry in the distribution within the lesion, and may have a gray color. The holes can have varying diameters. | NA |

| Blue-white veil | An irregularly shaped area of blue hue with an overlying whitish ground-glass haze. | NA |

| Irregular pigmentation | Asymmetry in the distribution of colors/pigmentation within the lesion. | While this pattern was considered by some studies to be similar to an off-center blotch, several studies reporting irregular pigmentation separated it from off-center blotches. Therefore, irregular pigmentation and off-centered blotch were assessed independently in this meta-analysis. |

| Multicomponent pattern | Presence of 3 or more dermoscopic structures within a single lesion. | NA |

| Negative network | Serpiginous interconnecting hypopigmented lines that surround elongated and curvilinear globules. | NA |

| Off-center blotch | One or more hyperpigmented structureless areas located off center. | NA |

| Peripheral tan structureless areas | Homogeneous light brown area devoid of any definable structures located at the lesion periphery. | NA |

| Regression structures | Regression structures include scarlike areas and peppering. | While both scarlike areas and peppering are features of regression, some studies categorized these features into 3 separate subgroups: regression, scarlike areas, and peppering. |

| Scarlike areas/depigmentation | White area that is whiter than the surrounding normal skin. | |

| Peppering or granularity | Fine blue-gray dots. | |

| Shiny white structures/streaks | Short, bright, white lines distributed in a parallel or orthogonal orientation. These lines can only be appreciated with polarized dermoscopy. | Formerly known as crystalline structures. |

| Streaks/radial streaming | Radial linear extensions at the lesion edge. | As most studies describing pseudopods also had a separate category labeled streaks, we categorized the features into 2 groups: streaks and pseudopods. |

| Pseudopods | Bulbous projections extending from the lesion, either directly associated with a network or a solid tumor. | |

| Vascular structures | ||

| Polymorphous/atypical vessels | Polymorphous pattern: 2 or more vessel shapes within the lesion (eg, dotted, linear irregular, corkscrew). | As most of the included studies combined polymorphous and atypical vessels into 1 category, we also merged these classifications. |

| Linear irregular vessels | Linear irregular or serpentine vessels: Linear vessels with multiple bends. |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Data Extraction

Two authors (N.M.W., K.D.R.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all English and Spanish citations produced via the search strategy and used the noted criteria to analyze the articles that would advance to full-text screening. The full texts of all potentially eligible studies were then scrutinized and cross-checked by 2 authors (N.M.W., K.D.R.) independently. Disagreements were resolved by reevaluation and consensus discussion. There were no cases in which a third author (N.J.) was required to resolve a disagreement. Each author independently extracted data from eligible studies using a spreadsheet. Collected data included author, publication year, country, number of participating centers, funding, study design, number of patients, sex, age, sample size, number of melanomas, clinical and histopathologic characteristics of the melanomas (eg, anatomic site, histologic subtypes, and Breslow depth), dermoscopic structures and/or patterns, and number and type of nonmelanoma lesions (eg, nevi, seborrheic keratoses, and keratinocyte carcinomas).

Methodological Quality Assessment

The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool19 was applied independently by 2 authors (N.M.W., K.D.R.) to assess the quality of the studies reporting DA, and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) tool20 was applied independently to assess the quality of observational studies reporting ORs.

Using the QUADAS-2 tool, a total of 4 domains were evaluated for risk of bias (ie, low, high, or unclear) and concerns regarding applicability (ie, low, high, or unclear). The 4 domains were patient selection, index test (ie, dermoscopy), reference standard (ie, histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma), and flow and timing of patients. Each study had an overall judgment for risk of bias (ie, low or at risk of bias) and concern regarding applicability (ie, low or having concerns regarding applicability). A study judged as low on all domains relating to risk of bias or applicability was considered to have an overall low risk of bias or low concern regarding applicability. In contrast, a study judged as high or unclear in 1 or more domains was considered at risk of bias or having concerns regarding applicability.

Using the NOS tool, the following 8 domains were analyzed: adequacy of case definition, representativeness of cases, selection of controls, definition of controls, comparability of cases and controls, ascertainment of exposure, same method of ascertainment for cases and controls, and nonresponse rate. For cases to be considered adequate and representative, histopathologic diagnoses of melanoma were required, with cases included based on consecutive recruitment from specified clinics over a defined time period. Likewise, adequate control selection was met if the study selected controls randomly or consecutively from the same clinical site. Satisfactory control definition was based on an explicitly stated benign histopathologic diagnosis or digital monitoring. Comparability was estimated by similar age and sex ratios among cases and controls. Passable exposure ascertainment was based on multiple dermoscopists and/or reviewers blinded to diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were completed using Stata, version 4.11 (StataCorp) and R, version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). For each meta-analysis, the Cochran Q statistic test was calculated to assess the heterogeneity of studies, which was defined by the value of I2. When I2 was greater than 25%, studies were considered to have significant heterogeneity and the random-effects model was applied. Forest plots were created demonstrating the pooled value with its 95% CI. A 2-tailed P < .05 was deemed statistically significant. Publication bias was examined using the Egger test based on a linear regression model.21

Results

Literature Search and Included Studies

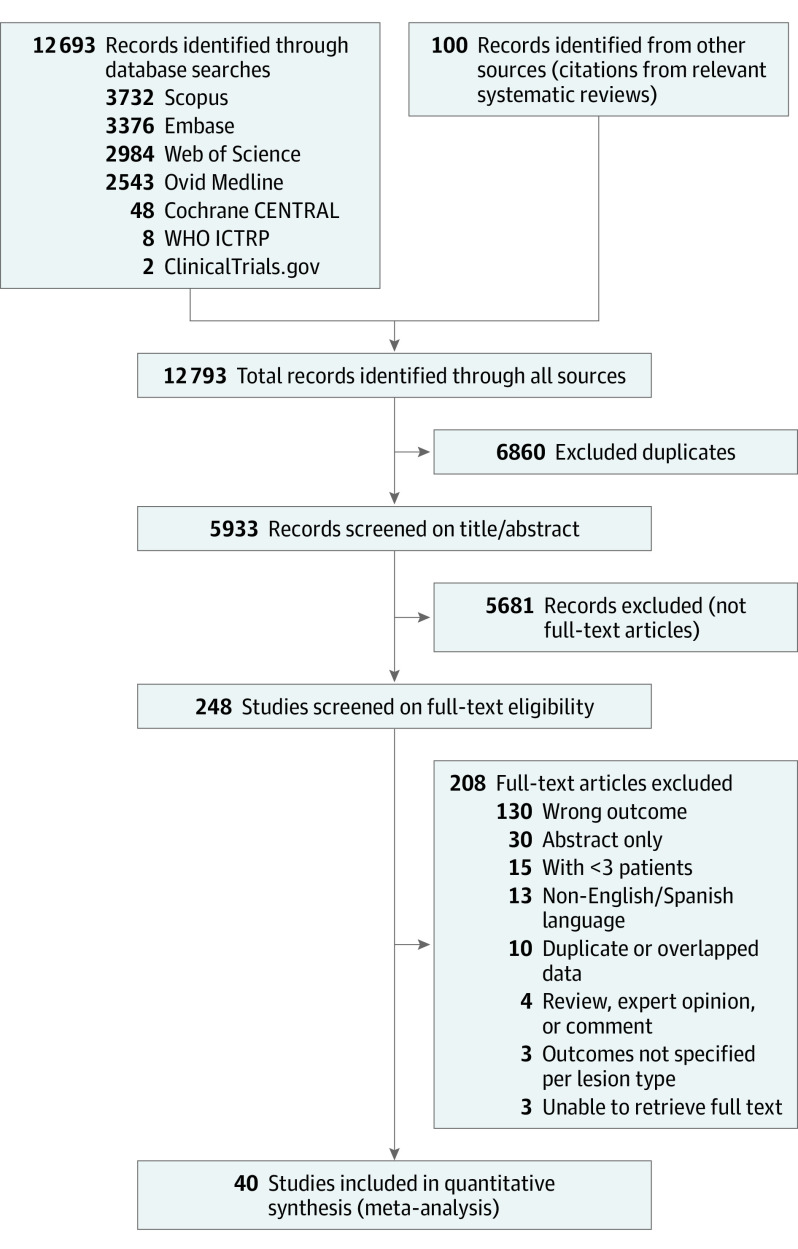

Database searching retrieved a total of 5933 unique records, with 248 studies undergoing full-text screening; 40 studies including 22 796 skin lesions and 5736 melanomas were evaluated. The screening history is shown in the Figure, and characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 2. Most studies were nonrandomized and retrospective. The number of melanomas varied between studies (range, 13-1541). Most melanomas were invasive, and were located on the trunk and extremities; and when specified, superficial spreading melanoma was the most common histologic subtype. Although most studies included invasive and in situ melanomas, not all studies stratified the structures into these 2 categories. Overall, an atypical network was the most reported dermoscopic structure (19 studies [47.5%]), followed by streaks (18 [45.0%]), atypical dots/globules (17 studies [42.5%]), atypical/polymorphous vessels (17 studies [42.5%]), and regression (17 [42.5%]).

Figure. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Flow Diagram.

WHO ICTRP indicates World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform.

Table 2. Main Characteristics of the 40 Eligible Studies.

| Source | Center, No. | Funding | Study type, participants, No. | Patient ages | Melanomas | Nonmelanomas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included, No. | Features | Included, No. | Features | |||||

| Annessi et al,7 2007 Italy | 1 | None | Prospective, 195 | Mean (all): 43 | 96 | Sites: trunk, limbs; 25% in situ; 75% SSM; Breslow, mean: 0.3 mm | 102 | Clark nevi (67% junctional, 33% compound) |

| Arevalo et al,22 2008 Australia | 1 | NA | Retrospective, NA | NA | 341 | All subtypes except LM and LMM | 3026 | Benign melanocytic lesions |

| Argenziano et al,23 2004 Italyb | 1 | NA | Retrospective, 517 | Median (all): 34 | 150 | 11% in situ | 381 | 31% BCC; 25% dermal/congenital nevi; 19% Clark nevi; 11% SK; 5% Spitz; 4% Bowen; 4% SCC; 2% sebaceous hyperplasia |

| Balagula et al,24 2012 US | 2 | None | Prospective, NA | NA | 20 | 15% in situ; 20% metastasis | 36 | Benign biopsied melanocytic lesions |

| Bassoli et al,25 2018 Italy | 1 | Italian Ministry of Health | Retrospective, NA | NA | 71 | Sites: lower limbs; invasive tumors all <1 mm; 51% in situ | 176 | 51% Nevi; 37% Spitz; 13% nonmelanocytic lesions |

| Benati et al,26 2015 Italy | 2 | None | Retrospective, 83 | Mean (all): 40.4 | 28 | Sites: trunk; Breslow, mean (SD): 0.58 mm (0.40) | 55 | 71% Common nevi; 29% Spitz |

| Blum et al,27 2003 Germany | 1 | NA | Retrospective, 205 | Median (SD) (all): 39.2 (17.3) (range, 1-86) | 75 | Breslow, mean: 0.86 mm (0.01-3.50); 16% in situ | 179 | 36% Common nevi; 54% dysplastic; 11% other benign nevi |

| Borsari et al,28 2018 Italy | 1 | Italian Ministry of Health | Retrospective, 314 | Median (cases): 63 (IQR, 49-73) | 120 | Sites: back; 100% in situ | 213 | 78% Common acquired nevi; 22% Spitz |

| Borsari et al,29 2020 Italy | 6 | None | Retrospective, NA | All, mean (SD): 52.8 (15) | 107 | Sites: trunk, limbs; Breslow, mean: 0.4 mm; 57% in situ, 30% nevus-associated | 133 | 97% Common acquired nevi; 3% Spitz |

| Braun et al,30 2007 Switzerland | 2 | NA | Retrospective, NA | NA | 170 | 61% in situ; 31% < 1 mm; 8% > 1 mm | 170 | Nevi (65% low-grade dysplastic; 33% high-grade dysplastic; 1% compound) |

| Carrera et al,8 2016 Multiple | 12 | Various grantsa | Retrospective, NA | NA | 1541 | NA | 4064 | Nevi |

| Costa et al,31 2013 Spainb | 1 | Various grantsc | Retrospective, 42 | Median (all): 54.8 (13-79) | 15 | Sites: limbs, trunk, soles; Breslow, mean (SD): 4.5 (4.5) mm) (range, 0.8-22) | 15 | Melanocytic nevi |

| Di Stefani et al,32 2010 Austria | 1 | NA | Retrospective, NA | NA | 400 | Breslow, mean: 0.87 mm | 400 | Melanocytic nevi |

| Farnetani et al,33 2019 Italy | 2 | Italian Ministry of Health | Retrospective, 50 | Mean (all): 46.7 (24-80); mean (cases): 50.8; mean (controls): 43.6 | 21 | Sites: trunk, limbs | 29 | 93% Common nevi; 7% Spitz nevi |

| Fikrle et al,34 2006 Czech Republic | 1 | Internal Grant Agency of the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic | Retrospective, 161 | Age range (all): 14-82 | 60 | Breslow, mean: 0.47 mm (0.1-1.0); 33% in situ | 120 | 56% Common nevi; 44% atypical nevi |

| Haenssle et al,9 2010 Germany | 1 | Cancer Society of Lower Saxony | Prospective, 688 | Mean (all): 42 | 127 | Breslow, mean: 0.57 mm; 39% in situ | 777 | Biopsied nonmelanomas (common/dysplastic nevi, Spitz, SK, SL, pigmented BCC, pigmented DF) |

| Lallas et al,35 2018 Greece | 3 | NA | Retrospective, 1285 | Mean (all): 45.9 (9-91) | 427 | Sites: trunk, limbs; Breslow, mean: 0.49 mm; 76% in situ | 858 | 36% Excised nevi; 31% nonexcised nevi; 12% Spitz nevi; 11% BCC; 8% SK; 3% Bowen |

| Liebman et al,36 2012 US | 1 | None | Retrospective, NA | NA | 154 | NA | 384 | 50% BCC; 26% SCC; 14% LPLK; 11% AK |

| Mandel et al,37 2018 Italy | 1 | Italian Ministry of Health | Retrospective, 55 | Mean (SD) (all): 45.6 (16.7) | 21 | Sites: breast; Breslow, median: 0.4 mm; 57% in situ | 34 | 88% Common nevi; 12% Spitz nevi |

| Mansur et al,38 2011 Brazil | 1 | None | Retrospective, 137 | Median (all): 45 | 84 | Breslow, median: 0.53 mm; 48% in situ | 135 | 59% Atypical nevi; 41% common nevi |

| Menzies et al,39 1996 Australia | 1 | NA | Retrospective, NA | NA | 62 | 82% SSM; 15% LMM; 3% NM | 159 | 43% Dysplastic nevi; 19% benign acquired nevi; 9% SK; 8% ephelides/SL; 6% pigmented BCC; 6% other nevi |

| Menzies et al,40 2008 Australia | Various | NA | Retrospective, NA | NA | 105 | 76% SSM; 7% NM; 12% nevus-associated; 100% hypo/amelanotic; Breslow, median: 0.76 mm | 392 | 43% Benign melanocytic lesions (nevi, SL, ephelides); 57% nonmelanocytic lesions |

| Menzies et al,41 2013 Australia | Various | None | Retrospective, NA | NA | 52 | Pigmented NM; Breslow, median: 2.7 mm | 138 | Pigmented nodular nonmelanomas (54% nodular benign melanocytic lesions; 46% nodular nonmelanocytic lesions) |

| Menzies et al,41 2013 Australia | Various | None | Retrospective, NA | NA | 31 | Hypomelanotic/amelanotic NM; Breslow, median: 2.7 mm | 99 | Amelanotic/hypomelanotic nodular nonmelanomas (11% amelanotic benign lesions; 29% hypomelanotic benign melanocytic lesions; 31% amelanotic nonmelanocytic lesions; 28% hypomelanotic nonmelanocytic lesions) |

| Merkel et al,42 2016 US | 1 | IDP Foundation | Retrospective, 109 | Cases, mean (SD): 51.8 (18.3); controls, mean (SD): 38.0 (13.7) | 13 | Sites: breast, chest; 77% SSM; 23% LM; Breslow, median: 0.37 mm (0.15-1.96); 62% in situ | 104 | Melanocytic nevi (65% nevi with no/mild atypia; 25% moderate atypia; 10% severe atypia) |

| Mun et al,43 2016 Australia | 1 | None | Retrospective, 65 | Cases, mean: 59.4 (range, 32-84) | 22 | Sites: trunk, limbs; 55% SSM; 45% NM; Breslow, mean (SD): 3.4 mm (4.0); 14% in situ | 100 | 63% Common nevi; 6% congenital nevi; 5% IDN |

| Nilles et al,44 1994 Germany | 1 | NA | Retrospective, NA | NA | 72 | 78% SSM; 11% LMM | 188 | 69% Common nevi; 14% atypical; 12% Spitz nevi |

| Panasiti et al,45 2009 Italy | 1 | None | Retrospective, 907 | NA | 33 | NA | 291 | 73% Common nevi; 25% dysplastic nevi; 1% Spitz |

| Pizzichetta et al,46 2004 Italy | 5 | NA | Retrospective, 151 | All, mean (SD): 47 (17.5); cases, mean (SD): 50 (16.7) | 44 | Sites: trunk, limbs; 100% hypo/amelanotic; 66% < 1 mm; 34% > 1 mm | 55 | Hypo/amelanotic lesions (45% BCC; 18% DF; 15% Bowen; 15% SK; 7% SCC) |

| Pizzichetta et al,47 2015 Italy | 15 | None | Retrospective, 457 | Cases, median: 61 (range, 21-92); controls, median: 46 (range, 11-95) | 75 | Sites: trunk, limbs; 100% NM; Breslow, median: 3.4 mm (0.05-11) | 289 | Nonmelanocytic lesions (29% SK; 13% BCC); benign melanocytic lesions (29% compound/dermal nevi; 28% blue nevi) |

| Pizzichetta et al,48 2013 Italy | 11 | None | Retrospective, 679 | All, mean (SD): 43 (17); cases, mean (SD): 54 (17) | 205 | Sites: trunk, limbs; 23% in situ | 474 | 46% Melanocytic nevi; 29% Spitz/Reed nevi; 24% DF |

| Püspök-Schwarz et al,49 1997 Austria | 1 | NA | Retrospective, NA | NA | 25 | Breslow, mean: 0.82 mm (0.3-3.0) | 25 | Pigmented BCC |

| Sakakibara et al,50 2010 Japan | 1 | NA | Retrospective, NA | Mean (cases): 65 (18-94) | 102 | 27% in situ; 50% > 2 mm | 639 | 40% SK; 33% DN⁄CN; 19% BCC; 2% SCC; 6% Bowen |

| Seidenari et al,51 2010 Italy | 1 | NA | Retrospective, 255 | All, mean (SD): 50.6 (17.4) | 170 | Sites: trunk, limbs; Breslow, mean (SD): 1.5 mm (2.4); 50% in situ | 85 | Nevi |

| Shitara et al,52 2014 Spain | 1 | Various grantsd | Retrospective, NA | NA | 125 | Sites: head, limbs, trunk; 55% SSM; 37% LMM; Breslow, mean: 1.7 mm; 45% in situ; 48% < 1 mm | 520 | 59% Nevi; 9% SK; 7% AK; 4% SL; 2% LPLK; 18% other |

| Skvara et al,53 2005 Austria | 2 | Austrian Federal Bank Grant 9952 | Retrospective, 297 | Mean (all): 39 | 63 | 14% Nevus-associated; Breslow, median: 0.4 mm (0.17-0.28); 49% in situ | 262 | Melanocytic nevi |

| Stanganelli et al,54 2012 Italy | 35 | NA | Retrospective, 315 | Mean (all): 52 (3-88) | 71 | Sites: scalp; 34% SSM; 27% LM; 6% NM; Breslow, median: 1.6 mm (0.12-12); 24% in situ | 78 | Melanocytic nevi |

| Steiner et al,55 1993 Austria | 1 | NA | Retrospective, NA | NA | 80 | Breslow, mean: 1.39 mm (0.4-2.6); 19% in situ, 31% < 1 mm | 61 | Common nevi (junctional nevi, compound nevi, dermal nevi) |

| Verzi et al,56 2018 US | 1 | IDP Foundation | Retrospective, NA | Median (all): 38; median (cases): 51; median (controls): 37 | 144 | Sites: trunk, limbs | 1363 | 82% dysplastic nevi; 13% common nevi; 2% SL; 2% Spitz |

| Xu et al,57 2009 US | 3 | National Institutes of Health (NIH) | Retrospective, NA | NA | 175 | 100% invasive | 425 | 75% dysplastic nevi (mild/moderate atypia); 25% nevocellular nevi |

| Zalaudek et al,58 2013 Italy | 5 | None | Retrospective, 65 | Mean (cases): 51.2 (20-74); mean (controls): 26.8 (6-56) | 39 | Sites: lower limbs; Breslow, median: 0.4 mm; 72% hypopigmented | 26 | Spitz nevi (54% hypopigmented) |

Abbreviations: AK, actinic keratosis; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; DF, dermatofibroma; DN, dysplastic nevus; IDN, intradermal nevus; IQR, interquartile range; LM, lentigo maligna; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; LPLK, lichen planus like keratosis; NA, no data available; NM, nodular melanoma; SK, seborrheic keratosis; SL, solar lentigo; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma.

This research was funded in part through National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA008748. The research at the Melanoma Unit in Barcelona is partially funded by grants 12/00840 and PI15/00716 from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, the CIBER de Enfermedades Raras of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the AGAUR 2014_SGR_603 of the Catalan Government, a grant from Fundació La Marató de TV3, 201331-30, and grant CE_CIP-ICT-PSR-13-7 from the European Commission under the 7th Framework Programme (Diagnoptics).

Data from this eligible study were not included in the meta-analysis.

The research at the Melanoma Unit in Barcelona is partially funded by Grant 09/1393 from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, Spain; by the CIBER de Enfermedades Raras of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain; by the AGAUR 2009 SGR 1337 of the Catalan Government, Spain; by the European Commission under the 6th Framework Programme, Contract no: LSHC-CT-2006-018702 (GenoMEL); and by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (CA83115).

The research at the Melanoma Unit in Barcelona is partially funded by grants from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias P.I. 09/01393 and P.I. 12/00840, Spain; by the CIBER de Enfermedadesraras of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain; by the AGAUR 2009 Sgr1337 of the Catalan government, Spain; and by the European Commission under the 6th Framework Programme, Contract nr: lSHC-CT-2006-018702 (genoMEl).

Histopathologic characteristics (eg, depth and subtype), number of patients, and patient characteristics (eg, mean [SD] age, skin type, and percentage of men and women) varied between studies and were not consistently reported. Therefore, overall summary data are not available. Additionally, specific structures (eg, angulated lines) with a small amount of data were excluded from the final analysis.

Quality Assessment

The risks of bias of the DA and nonrandomized observational studies are summarized in eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement. Using the QUADAS-2 tool, most studies reported low risk of bias with regard to the index test (ie, dermoscopy). However, risk of bias in terms of patient selection, flow and timing, and reference standard (ie, histopathologic diagnosis) were mostly high or unclear owing to a lack of consecutive or random enrollment of patients or if control lesions were not histopathologically diagnosed (ie, assumed benign with digital monitoring). In addition, most studies had low applicability concerns with the reference standard but high applicability concerns with patient selection and the index test (ie, studies assessing lesions on special locations, such as breast), or including few expert dermoscopists. Using the NOS tool, most case-control studies obtained relatively high quality scores with low risk of bias in selection and exposure. However, most of these studies did not account for confounders such as age, sex, and anatomic sites, limiting comparability.

Using the Egger test, of the 16 dermoscopic structures and patterns used in melanoma detection, we found a significant risk of publication bias across the studies for 6 structures (atypical network [Egger Z=3.462; P < .001], pseudopods [Egger Z=4.2453; P < .001], streaks [Egger Z=2.2903; P = .02], regression [Egger Z=2.1053; P = .04], scarlike areas [Egger Z=2.2344; P = .03], and peppering [Egger Z=4.6081; P < .001]) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Most structures demonstrated strong heterogeneity (>75%); for example, scarlike areas (l2 = 76.0%) and multicomponent pattern (l2 = 96.6%), and other structures demonstrated moderate heterogeneity (25%-75%); for example, pseudopods (l2 = 70.3%), linear irregular vessels (l2 = 61.0%), and peripheral-tan structureless areas (l2 = 50.4%). The combined analysis of linear irregular vessels and polymorphous/atypical vessels (l2 = 35.8%) as well as the combined analysis of streaks and pseudopods (l2 = 38.1%) also demonstrated moderate heterogeneity. The exact values of heterogeneity for each structure are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Diagnostic Accuracy and Odds Ratio of Each Melanoma-Specific Dermoscopic Structure and/or Pattern From Highest to Lowest Sensitivity.

| Structure | No. of studies (lesions) | % (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | l2, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Irregular pigmentation | 5 (1226) | 62.3 (31.2-85.8) | 78.6 (57.6-90.8) | 6.4 (2.0-20.5) | 87.9 |

| Blue-white veil | 17 (10 128) | 60.6 (46.7-72.9) | 79.7 (71.8-85.9) | 6.3 (3.7-10.7) | 89.0 |

| Atypical network | 19 (11 787) | 56.8 (43.6-69.2) | 71.8 (59.9-81.3) | 3.3 (2.4-4.5) | 83.8 |

| Multicomponent pattern | 9 (12 299) | 53.7 (40.4-66.4) | 82.4 (72.2-89.4) | 5.6 (2.4-13.0) | 96.6 |

| Atypical dots and/or globules | 17 (5497) | 49.7 (37.8-61.8) | 73.0 (61.8-81.9) | 2.7 (1.8-4.1) | 85.1 |

| Regression | 17 (10 542) | 48.1 (32.1-64.5) | 83.6 (69.7-91.9) | 4.6 (3.0-6.9) | 84.8 |

| Regression and peppering | 21 (11 739) | 44.9 (32.0-58.4) | 86.5 (77.3-92.4) | 4.7 (3.3-6.8) | 88.7 |

| Off-center blotch | 16 (12 850) | 42.1 (29.6-55.6) | 84.1 (74.6-90.5) | 3.8 (2.7-5.5) | 85.8 |

| Peripheral tan structureless area | 12 (8285) | 37.5 (22.3-55.7) | 76.1 (65.6-84.2) | 2.0 (1.3-3.0) | 50.4 |

| Peppering | 7 (7112) | 36.8 (19.1-58.9) | 93.4 (81.9-97.8) | 6.3 (2.4-16.1) | 91.6 |

| Negative network | 8 (7011) | 34.5 (30.5-38.7) | 70.8 (47.0-86.8) | 1.3 (0.7-2.4) | 79.2 |

| Scarlike areas | 8 (7328) | 31.3 (16.9-50.5) | 89.1 (83.7-92.9) | 4.4 (2.7-7.2) | 76.0 |

| Shiny white structures | 9 (9687) | 30.5 (15.8-50.7) | 93.6 (85.6-97.3) | 6.7 (2.5-17.9) | 95.2 |

| Linear irregular vessels | 5 (1806) | 23.2 (9.7-46.0) | 86.8 (74.3-93.7) | 2.1 (1.3-3.6) | 61.0 |

| Linear irregular vessels and polymorphous/atypical vessels | 18 (11 284) | 22.1 (14.6-32.1) | 81.6 (83.7-91.9) | 2.3 (1.7-3.1) | 35.8 |

| Polymorphous/atypical vessels | 17 (11 505) | 21.9 (13.3-33.8) | 89.0 (83.6-93.0) | 2.4 (1.7-3.4) | 80.6 |

| Streaks | 18 (11 035) | 21.1 (14.0-30.4) | 92.1 (88.4-94.7) | 3.1 (2.2-4.5) | 77.5 |

| Streaks and pseudopods | 18 (11 035) | 19.3 (13.9-26.2) | 83.8 (91.0-95.7) | 3.4 (2.6-4.6) | 38.1 |

| Pseudopods | 7 (6751) | 15.4 (8.8-25.6) | 97.3 (94.3-98.7) | 6.7 (2.7-16.1) | 70.3 |

Meta-analyzed Results

The sensitivities, specificities, and ORs of dermoscopic structures and patterns used in melanoma detection were analyzed by meta-techniques. The dermoscopic structures and patterns included in our meta-analysis were atypical dots and/or globules,7,9,26,28,33,34,35,37,40,41,42,43,46,47,54,55,57 atypical network,7,8,9,28,29,33,34,35,37,38,40,42,43,45,47,48,53,54,55 blue-white veil,7,8,28,33,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,46,47,51,53,54 irregular pigmentation,33,37,40,44,47 multicomponent pattern,8,22,27,29,34,35,47,48,53 negative network,8,33,37,38,39,42,48,58 off-center blotch,7,8,22,27,29,33,34,35,37,38,41,42,43,47,53,54 peripheral-tan structureless areas,7,8,27,34,38,40,42,43,47,51,53,54 regression structures7,8,9,25,27,28,33,34,35,37,42,43,46,47,51,53,54 including scarlike areas8,38,39,40,41,44,51,55 and peppering,8,30,37,38,40,51,55 shiny white structures,8,24,32,33,36,43,47,52,56 pseudopods,8,38,39,41,49,53,55 streaks,7,8,9,28,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,47,49,53,54,55 polymorphous/atypical vessels,7,8,9,28,33,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,47,50,53,54 and linear irregular vessels.40,41,46,50,54 The results are summarized in Table 3 with forest plots presented in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

The structures and patterns with the highest sensitivity were irregular pigmentation (62.3%; 95% CI, 31.2%-85.8%), blue-white veil (60.6%; 95% CI, 46.7%-72.9%), atypical network (56.8%; 95% CI, 43.6%-69.2%), and a multicomponent pattern (53.7%; 95% CI, 40.4%-66.4%). Irregular pigmentation was considered to be similar to an off-centered blotch by some studies, but other studies separated the 2 terms33,47; therefore these features were assessed independently in this meta-analysis. Notably, our systematic review identified only 5 studies for irregular pigmentation. Its OR estimates were largely dispersed from 1.08 to 23.86 (eTable 3 in the Supplement) with 4 of 5 data points falling outside of the funnel (eTable 4 in the Supplement), leading to a pooled estimate with a wider 95% CI.

The features with the highest specificity were pseudopods (97.3%; 95% CI, 94.3%-98.7%), shiny white structures (93.6%; 95% CI, 85.6%-97.3%), peppering (93.4%; 95% CI, 81.9%-97.8%), and streaks (92.1%; 95% CI, 88.4%-94.7%). The structures and patterns with the highest risk of melanoma when present in the lesion were shiny white structures (OR, 6.7; 95% CI, 2.5-17.9), pseudopods (OR, 6.7; 95% CI, 2.7-16.1), irregular pigmentation (OR, 6.4; 95% CI, 2.0-20.5), blue-white veil (OR, 6.3; 95% CI, 3.7-10.7), and peppering (OR 6.3; 95% CI, 2.4-16.1).

Discussion

Dermoscopy is a cost-effective tool in the diagnosis of melanoma. Its use has been associated with increases in the DA for melanoma, improvements in the benign-to-malignant ratio, and decreases in the number of unnecessary skin biopsies.59 Based on level of experience, different reasoning approaches are involved in the differentiation of nevi from melanoma (eg, pattern analysis, simplified algorithms). Regardless of the approach, most melanomas manifest a disorganized pattern and reveal at least 1 melanoma-specific structure under dermoscopy. In contrast, nevi tend to present an overall organized pattern without melanoma-specific structures. In this study, we affirmed the diagnostic importance of dermoscopic structures associated with melanoma detection and further supported the importance of the overall pattern of a lesion.

A total of 40 studies including 22 796 skin lesions and 5736 melanomas were systematically reviewed to assess the DA of dermoscopic structures and patterns used in melanoma detection. As expected, the dermoscopic structures associated with melanoma detection tended to have higher specificity compared with sensitivity, with each structure yielding a specificity greater than 70%. The structures with the highest specificity for the diagnosis of melanoma were pseudopods, shiny white structures, peppering, and streaks, all of which demonstrated a high specificity compared with sensitivity. In contrast, the structures and patterns with the highest sensitivity were irregular pigmentation, blue-white veil, atypical network, and a multicomponent pattern. The 4 structures with the highest specificities in our study previously demonstrated a poor to fair level of interobserver agreement in the study by Carrera et al,8 and the overall pattern (eg, irregular pigmentation and multicomponent pattern) demonstrated the highest levels of discriminatory power and interobserver agreement.8 In our study, irregular pigmentation was defined as an asymmetric distribution of pigment; however, other studies consider it to be similar to an off-center blotch and do not report these features independently. This discrepancy, as well as the overall lack of data for irregular pigmentation, may be a factor in the variability seen in our analysis, further emphasizing the importance of using standardized, agreed-on dermoscopic terminology. Nonetheless, these findings support previous observations regarding the overall pattern (ie, organization of colors or structures) over individual structures,60,61,62,63,64 with a disorganized or asymmetric pattern frequently being included as a key feature in different dermoscopy algorithms.65,66,67,68

As in prior studies, our results suggest that these dermoscopic structures are significantly associated with melanoma diagnosis, with the exception of a negative network, which did not meet statistical significance. A possible explanation for this finding is that a negative network can be seen in dysplastic and Spitz nevi, as reported by Zalaudek et al.58 Yet several studies69,70,71 have reported that a negative network may be a factor associated with nevus-associated melanomas and is 2.5 times more common in nevus-associated melanomas compared with de novo melanomas.

The structures and patterns with the highest ORs for melanoma were shiny white structures, pseudopods, irregular pigmentation, blue-white veil, and peppering, each of which yielded a greater than 6-fold risk for melanoma. This finding is consistent with the study by Roh et al72 published after our search in July 2020, which found that melanoacanthomalike melanomas (n = 33) had a significantly higher prevalence of blue-white veil, pseudopods, streaks, atypical network, and atypical vessels compared with melanoacanthomas (n = 77).

Although we were not able to explore the association between dermoscopic structures and melanoma subtype, previous studies have shown that the presence or absence of specific structures may be associated with some subtypes. For instance, studies consisting only of nodular melanomas have reported an association with blue-white veil and atypical vessels.41 The study by Sgouros et al73 found that irregular blue structureless areas and atypical vessels (ie, dotted and linear irregular) were associated with NM compared with nonmelanoma nodular lesions. Conversely, in situ melanomas may lack these structures and commonly present with an atypical network or regression.28

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the heterogeneity of studies may limit the strength of the results (ie, some studies adjusted for different sets of covariates and not all studies provided fully adjusted effect estimates; thus we had to pool raw data for the meta-analysis). Second, most structures and patterns demonstrated significant heterogeneity across studies, as further evidenced by wide 95% CIs in Table 3, which may be a factor in the uncertainty of our results. Third, more than half of the included studies were conducted at centers located in Europe, in particular Italy, which may be considered another limitation of this study. The quality of some studies was classified as unclear. In addition, although there was a consensus in terminology in 2016,18 the criteria used for defining dermoscopic structures differed between studies. Therefore, future studies should attempt to standardize lesion features and variables to better elucidate possible associations, and ideally follow a prospective interventional design.

Conclusions

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis support the diagnostic importance of dermoscopic structures and patterns associated with melanoma detection. Knowledge of their validity measures, such as DA (sensitivity, specificity) and risk (OR), may not only assist clinicians during the evaluation of skin lesions but also suggest a hierarchy in the significance of these structures and patterns. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of melanoma is usually rendered when the lesion is evaluated as a whole and these features are examined together; thus the more structures that are present in a lesion, the higher the odds the lesion is melanoma. To improve both sensitivity and specificity for melanoma and reduce the amount of misclassification, clinicians should continue to develop their diagnostic skills via additional training and dermoscopy education.

eTable 1. Risk of Bias With the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) Scale

eTable 2. Risk of Bias With the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)

eTable 3. Funnel Plots of the Melanoma-Specific Dermoscopic Structures and/or Patterns

eTable 4. Annotated Forest Plots of the Melanoma-Specific Dermoscopic Structures and/or Patterns

eAppendix 1. Database Search Strategies

eAppendix 2. Full Citations of Included Studies

eAppendix 3. Full Citations of Excluded Studies With Reason for Exclusion

References

- 1.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: melanoma of the skin. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html

- 2.Hirst NG, Gordon LG, Scuffham PA, Green AC. Lifetime cost-effectiveness of skin cancer prevention through promotion of daily sunscreen use. Value Health. 2012;15(2):261-268. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tromme I, Legrand C, Devleesschauwer B, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis in melanoma detection: A transition model applied to dermoscopy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;67:38-45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts CG, Dieng M, Morton RL, Mann GJ, Menzies SW, Cust AE. Clinical practice guidelines for identification, screening and follow-up of individuals at high risk of primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(1):33-47. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al. ; Cochrane Skin Cancer Diagnostic Test Accuracy Group . Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011902.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Australian Cancer Network Melanoma Guidelines Revision Working Party . Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma in Australia and New Zealand. The Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network, Sydney and New Zealand Guidelines Group, Wellington; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annessi G, Bono R, Sampogna F, Faraggiana T, Abeni D. Sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of three dermoscopic algorithmic methods in the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic lesions: the importance of light brown structureless areas in differentiating atypical melanocytic nevi from thin melanomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(5):759-767. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrera C, Marchetti MA, Dusza SW, et al. Validity and reliability of dermoscopic criteria used to differentiate nevi from melanoma: a web-based International Dermoscopy Society Study. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(7):798-806. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haenssle HA, Korpas B, Hansen-Hagge C, et al. Seven-point checklist for dermatoscopy: performance during 10 years of prospective surveillance of patients at increased melanoma risk. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(5):785-793. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soyer HP, Smolle J, Leitinger G, Rieger E, Kerl H. Diagnostic reliability of dermoscopic criteria for detecting malignant melanoma. Dermatology. 1995;190(1):25-30. doi: 10.1159/000246629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JPT, Lasserson T, Chandler J, et al. Standards for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews. February 24, 2021. Accessed June 23, 2021. https://community.cochrane.org/mecir-manual

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336-341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carapeba MOL, Alves Pineze M, Nai GA. Is dermoscopy a good tool for the diagnosis of lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma? a meta-analysis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:403-414. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S208717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pampena R, Lai M, Lombardi M, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features associated with difficult-to-recognize variants of cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(4):430-439. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kittler H, Marghoob AA, Argenziano G, et al. Standardization of terminology in dermoscopy/dermatoscopy: results of the third consensus conference of the International Society of Dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1093-1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. ; QUADAS-2 Group . QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529-536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Published 2019. Accessed December 18, 2020.

- 21.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arevalo A, Altamura D, Avramidis M, Blum A, Menzies S. The significance of eccentric and central hyperpigmentation, multifocal hyper/hypopigmentation, and the multicomponent pattern in melanocytic lesions lacking specific dermoscopic features of melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(11):1440-1444. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.11.1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, Corona R, et al. Vascular structures in skin tumors: a dermoscopy study. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(12):1485-1489. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balagula Y, Braun RP, Rabinovitz HS, et al. The significance of crystalline/chrysalis structures in the diagnosis of melanocytic and nonmelanocytic lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(2):194.e1-194.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassoli S, Kyrgidis A, Ciardo S, et al. Uncovering the diagnostic dermoscopic features of flat melanomas located on the lower limbs. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):e217-e218. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benati E, Argenziano G, Kyrgidis A, et al. Melanoma and naevi with a globular pattern: confocal microscopy as an aid for diagnostic differentiation. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(5):1232-1238. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blum A, Soyer HP, Garbe C, Kerl H, Rassner G, Hofmann-Wellenhof R. The dermoscopic classification of atypical melanocytic naevi (Clark naevi) is useful to discriminate benign from malignant melanocytic lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(6):1159-1164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borsari S, Pampena R, Benati E, et al. In vivo dermoscopic and confocal microscopy multistep algorithm to detect in situ melanomas. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(1):163-172. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borsari S, Peccerillo F, Pampena R, et al. The presence of eccentric hyperpigmentation should raise the suspicion of melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2802-2808. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun RP, Gaide O, Oliviero M, et al. The significance of multiple blue-grey dots (granularity) for the dermoscopic diagnosis of melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(5):907-913. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costa J, Ortiz-Ibañez K, Salerni G, et al. Dermoscopic patterns of melanoma metastases: interobserver consistency and accuracy for metastasis recognition. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(1):91-99. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Stefani A, Campbell TM, Malvehy J, Massone C, Soyer HP, Hofmann-Wellenhof R. Shiny white streaks: An additional dermoscopic finding in melanomas viewed using contact polarised dermoscopy. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51(4):295-298. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farnetani F, Scope A, Mazzoni L, et al. A comparative dermoscopic and reflectance confocal microscopy study of naevi and melanoma with negative pigment network. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(12):2273-2282. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fikrle T, Pizinger K. Dermatoscopic differences between atypical melanocytic naevi and thin malignant melanomas. Melanoma Res. 2006;16(1):45-50. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000195700.42766.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lallas A, Longo C, Manfredini M, et al. Accuracy of Dermoscopic Criteria for the Diagnosis of Melanoma In Situ. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(4):414-419. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liebman TN, Rabinovitz HS, Dusza SW, Marghoob AA. White shiny structures: dermoscopic features revealed under polarized light. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(12):1493-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandel VD, Bombonato C, Pampena R, et al. Integration of dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy for distinguishing melanomas from nevi of the breast area. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):940-946. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mansur MA, Rezze GG. Dermoscopic findings of radial streaming, blue hue and vascular structures as a tool to differentiate doubtful nevi and early melanomas: a comparative study. Surg Cosmetic Dermatol. 2011;3(4):276-281. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menzies SW, Ingvar C, McCarthy WH. A sensitivity and specificity analysis of the surface microscopy features of invasive melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1996;6(1):55-62. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199602000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menzies SW, Kreusch J, Byth K, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of amelanotic and hypomelanotic melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(9):1120-1127. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.9.1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menzies SW, Moloney FJ, Byth K, et al. Dermoscopic evaluation of nodular melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(6):699-709. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merkel EA, Martini MC, Amin SM, Lee CY, Gerami P. Evaluation of dermoscopic features for distinguishing melanoma from special site nevi of the breast. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(2):364-370. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mun JH, Ohn J, Kim WI, Park SM, Kim MB. Dermoscopy of melanomas on the trunk and extremities in Asians. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nilles M, Boedeker RH, Schill WB. Surface microscopy of naevi and melanomas—clues to melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(3):349-355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb02932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panasiti V, Devirgiliis V, Curzio M, et al. The reticular point of view in dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(4):605-610. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pizzichetta MA, Talamini R, Stanganelli I, et al. Amelanotic/hypomelanotic melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(6):1117-1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05928.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pizzichetta MA, Kittler H, Stanganelli I, et al. ; Italian Melanoma Intergroup . Pigmented nodular melanoma: the predictive value of dermoscopic features using multivariate analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(1):106-114. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pizzichetta MA, Talamini R, Marghoob AA, et al. Negative pigment network: an additional dermoscopic feature for the diagnosis of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4):552-559. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Püspök-Schwarz M, Steiner A, Binder M, Partsch B, Wolff K, Pehamberger H. Statistical evaluation of epiluminescence microscopy criteria in the differential diagnosis of malignant melanoma and pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Melanoma Res. 1997;7(4):307-311. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199708000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakakibara A, Kamijima M, Shibata S, Yasue S, Kono M, Tomita Y. Dermoscopic evaluation of vascular structures of various skin tumors in Japanese patients. J Dermatol. 2010;37(4):316-322. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00828.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seidenari S, Ferrari C, Borsari S, et al. Reticular grey-blue areas of regression as a dermoscopic marker of melanoma in situ. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(2):302-309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09821.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shitara D, Ishioka P, Alonso-Pinedo Y, et al. Shiny white streaks: a sign of malignancy at dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(2):132-137. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skvara H, Teban L, Fiebiger M, Binder M, Kittler H. Limitations of dermoscopy in the recognition of melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(2):155-160. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.2.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanganelli I, Argenziano G, Sera F, et al. Dermoscopy of scalp tumours: a multi-centre study conducted by the International Dermoscopy Society. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(8):953-963. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steiner A, Binder M, Schemper M, Wolff K, Pehamberger H. Statistical evaluation of epiluminescence microscopy criteria for melanocytic pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(4):581-588. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70225-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verzi AE, Quan VL, Walton KE, et al. The diagnostic value and histologic correlate of distinct patterns of shiny white streaks for the diagnosis of melanoma: a retrospective, case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(5):913-919. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu J, Gupta K, Stoecker WV, et al. Analysis of globule types in malignant melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(11):1245-1251. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zalaudek I, Kittler H, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, et al. “White” network in Spitz nevi and early melanomas lacking significant pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(1):56-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terushkin V, Warycha M, Levy M, Kopf AW, Cohen DE, Polsky D. Analysis of the benign to malignant ratio of lesions biopsied by a general dermatologist before and after the adoption of dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(3):343-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(5):679-693. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dolianitis C, Kelly J, Wolfe R, Simpson P. Comparative performance of 4 dermoscopic algorithms by nonexperts for the diagnosis of melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(8):1008-1014. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carli P, Quercioli E, Sestini S, et al. Pattern analysis, not simplified algorithms, is the most reliable method for teaching dermoscopy for melanoma diagnosis to residents in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):981-984. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosendahl C, Cameron A, McColl I, Wilkinson D. Dermatoscopy in routine practice - ‘chaos and clues’. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(7):482-487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, Cameron A, Kittler H. Diagnostic accuracy of dermatoscopy for melanocytic and nonmelanocytic pigmented lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(6):1068-1073. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jaimes N, Marghoob AA. Triage amalgamated dermoscopic algorithm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):1551-1552. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luttrell MJ, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Fink-Puches R, Soyer HP. The AC Rule for melanoma: a simpler tool for the wider community. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(6):1233-1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nachbar F, Stolz W, Merkle T, et al. The ABCD rule of dermatoscopy: high prospective value in the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(4):551-559. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70061-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seidenari S, Pellacani G, Martella A. Acquired melanocytic lesions and the decision to excise: role of color variegation and distribution as assessed by dermoscopy. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(2):184-189. doi: 10.1097/00042728-200502000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cuevas RG, Villani A, Apalla Z, et al. Dermatoscopic predictors of melanoma arising in small- and medium-sized congenital nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(6):1703-1705. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reiter O, Kurtansky N, Nanda JK, et al. The differences in clinical and dermoscopic features between in situ and invasive nevus-associated melanomas and de novo melanomas. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(5):1111-1118. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shitara D, Nascimento M, Ishioka P, et al. Dermoscopy of naevus-associated melanomas. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(6):671-675. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roh D, Ha DL, Kim Y, et al. Comparison of dermoscopic features between melanoacanthomas and melanoacanthoma-like malignant melanomas in Korean patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;1203475420977470. doi:10.1177/1203475420977470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sgouros D, Lallas A, Kittler H, et al. Dermatoscopic features of thin (≤2 mm Breslow thickness) vs. thick (>2 mm Breslow thickness) nodular melanoma and predictors of nodular melanoma versus nodular non-melanoma tumours: a multicentric collaborative study by the International Dermoscopy Society. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(11):2541-2547. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Risk of Bias With the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) Scale

eTable 2. Risk of Bias With the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)

eTable 3. Funnel Plots of the Melanoma-Specific Dermoscopic Structures and/or Patterns

eTable 4. Annotated Forest Plots of the Melanoma-Specific Dermoscopic Structures and/or Patterns

eAppendix 1. Database Search Strategies

eAppendix 2. Full Citations of Included Studies

eAppendix 3. Full Citations of Excluded Studies With Reason for Exclusion