Key Points

Question

Are the efficacy and safety of oral upadacitinib superior to subcutaneous dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD)?

Findings

This randomized, blinded, head-to-head comparator clinical trial of 673 patients with moderate-to-severe AD demonstrated clinically meaningful skin clearance and itch relief, with statistically significant superiority for upadacitinib compared with dupilumab. There were no new safety signals reported for either upadacitinib or dupilumab.

Meaning

Upadacitinib provides superior and more rapid skin clearance and itch relief with tolerable safety compared with dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe AD.

Abstract

Importance

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory skin disease with an unmet need for treatments that provide rapid and high levels of skin clearance and itch improvement.

Objective

To assess the safety and efficacy of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe AD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Heads Up was a 24-week, head-to-head, phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, double-dummy, active-controlled clinical trial comparing the safety and efficacy of upadacitinib with dupilumab among 673 adults with moderate-to-severe AD who were candidates for systemic therapy. The study was conducted from February 21, 2019, to December 9, 2020, at 129 centers located in 22 countries across Europe, North and South America, Oceania, and the Asia-Pacific region. Efficacy analyses were conducted in the intent-to-treat population.

Interventions

Patients were randomized 1:1 and treated with oral upadacitinib, 30 mg once daily, or subcutaneous dupilumab, 300 mg every other week.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was achievement of 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI75) at week 16. Secondary end points were percentage change from baseline in the Worst Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (weekly average), proportion of patients achieving EASI100 and EASI90 at week 16, percentage change from baseline in Worst Pruritus NRS at week 4, proportion of patients achieving EASI75 at week 2, percentage change from baseline in Worst Pruritus NRS (weekly average) at week 1, and Worst Pruritus NRS (weekly average) improvement of 4 points or more at week 16. End points at week 24 included EASI75, EASI90, EASI100, and improvement of 4 points or more in Worst Pruritus NRS from baseline (weekly average). Safety was assessed as treatment-emergent adverse events in all patients receiving 1 or more dose of either drug.

Results

Of 924 patients screened, 342 (183 men [53.5%]; mean [SD] age, 36.2 [14.4] years) were randomized to receive upadacitinib and 331 were randomized to receive dupilumab (192 men [58.0%]; mean [SD] age, 36.3 [13.8] years); demographic and disease characteristics were balanced among treatment groups. At week 16, 248 patients receiving upadacitinib (72.4%) and 207 patients receiving dupilumab (62.6%) achieved EASI75 (P = .007). All ranked secondary end points also demonstrated the superiority of upadacitinib vs dupilumab, including improvement in Worst Pruritus NRS as early as week 1 (mean [SE], 32.0% [1.8%] vs 8.9% [1.8%]; P < .001), achievement of EASI75 as early as week 2 (152 [44.3%] vs 60 [18.2%]; P < .001), and achievement of EASI100 at week 16 (97 [28.4%] vs 26 [7.9%]; P < .001). Rates of serious infection, eczema herpeticum, herpes zoster, and laboratory-related adverse events were higher for patients who received upadacitinib, whereas rates of conjunctivitis and injection-site reactions were higher for patients who received dupilumab.

Conclusions and Relevance

During 16 weeks of treatment, upadacitinib demonstrated superior efficacy vs dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, with no new safety signals.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03738397

This randomized clinical trial assesses the safety and efficacy of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is characterized by a chronic and relapsing nature, eczematous morphology, and intense pruritus.1,2 It is driven by proinflammatory mediators, such as interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-13, IL-22, IL-31, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), that transduce signals via the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway.3,4 Dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the shared IL-4 receptor subunit α of IL-4 and IL-13 receptors, is approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD; however, fewer than half of patients achieve clear or almost clear skin after 16 weeks of dupilumab monotherapy, with maximal responses achieved after week 12.5 Thus, there is a need for additional treatment options that provide improved clinical responses to a greater proportion of patients and in a more rapid manner.

Upadacitinib is an oral, reversible, small molecule JAK inhibitor engineered to have increased selectivity for JAK1 vs JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2, with the intention of improving efficacy and safety for an improved benefit-risk profile compared with other, less-selective JAK inhibitors.6 Upadacitinib is approved in the United States, European Union, and other countries to treat moderately or severely active rheumatoid arthritis, and is being developed for the treatment of AD and other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.6 Results from 1 phase 2b7 and 3 pivotal phase 3 clinical trials (Measure Up 1, Measure Up 2, and AD Up)8,9 demonstrated that once-daily upadacitinib (15 or 30 mg) is a well-tolerated and effective treatment option for patients with moderate-to-severe AD. Here, we assess the safety and efficacy of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe AD.

Methods

Study Design

Heads Up (NCT03738397) was a 24-week, head-to-head, phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, double-dummy, active-controlled clinical trial comparing the safety and efficacy of upadacitinib with dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe AD. This clinical trial was conducted from February 21, 2019, to December 9, 2020, at 129 centers located in 22 countries across Europe, North and South America, Oceania, and the Asia-Pacific region. Heads Up had a 35-day screening period, a 24-week double-blinded treatment period, and a 12-week follow-up visit or the option to enter an open-label upadacitinib extension study. Independent ethics committees or institutional review boards approved the trial protocol, informed consent form(s), and recruitment materials before patient enrollment. This clinical trial was conducted in accord with the International Conference for Harmonisation guidelines, applicable regulations, and the Declaration of Helsinki.10 Patients provided written informed consent before screening. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline (trial protocol in Supplement 1).

Patients

Eligible patients were adults aged 18 to 75 years with diagnosed AD using the Hanifin and Rajka criteria11 who were candidates for systemic therapy (inadequate response to topical treatments for AD, documented use of systemic treatment for AD, or topical treatments for AD otherwise medically inadvisable) and who had moderate-to-severe disease (defined as ≥10% of body surface area affected by AD, Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI] ≥16, validated Investigator’s Global Assessment for AD score ≥3 at screening and baseline visits, and weekly average Worst Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale [NRS] score ≥4 at baseline). Prior use of JAK inhibitors or dupilumab was prohibited. eTable 1 in Supplement 2 has complete patient eligibility criteria.

Clinical Trial Procedures

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 30 mg of upadacitinib via extended-release tablet administered orally once daily until week 24 or 300 mg of dupilumab administered as a subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks after a loading dose of 600 mg, starting at week 2 and until week 22 (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Rescue therapy, defined as any topical or systemic immunomodulatory treatment initiated for AD, could be given at any time per investigator discretion. Patients who received rescue therapy were considered nonresponders for binary end points after the initiation of rescue therapy.

Efficacy Parameters

Efficacy was assessed as upadacitinib superiority compared with dupilumab, with the primary end point being 75% improvement in EASI (EASI75) at week 16. Ranked secondary end points were: percentage change from baseline in Worst Pruritus NRS, achievement of EASI100 and EASI90 at week 16, percentage change from baseline in Worst Pruritus NRS at week 4, achievement of EASI75 at week 2, percentage change from baseline in Worst Pruritus NRS at week 1, and Worst Pruritus NRS improvement of 4 points or more at week 16. Additional unranked end points were assessed at week 24, including achievement of EASI75, EASI90, and EASI100, as well as improvement of 4 points or more in Worst Pruritus NRS. The Worst Pruritus NRS end points were based on weekly averages of daily pruritus scores. Dermatology Life Quality Index and Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure data were not collected after baseline in this study.

Safety Parameters

Safety was assessed as treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in all patients who received 1 or more dose of study drug through follow-up (30 days after the last dose of upadacitinib or 84 days after the last dose of dupilumab); a TEAE was defined as any adverse event (AE) that began or worsened in severity after initiation of upadacitinib or dupilumab. All AEs presented were treatment-emergent, unless otherwise noted.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted on an intent-to-treat basis. The primary approach for evaluating categorical end points was NRI-C (Nonresponder Imputation incorporating Multiple Imputation [MI] to handle missing data due to COVID-19). The initial NRI approach was revised to NRI-C because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have prevented visits owing to logistical restrictions; additional details regarding the NRI-C approach are outlined in the eMethods in Supplement 2. Multiplicity-adjusted results were obtained via a hierarchical testing procedure, controlling the overall type I error rate of all primary and ranked secondary end points at the 2-sided 0.05 level (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Results

Patient Disposition

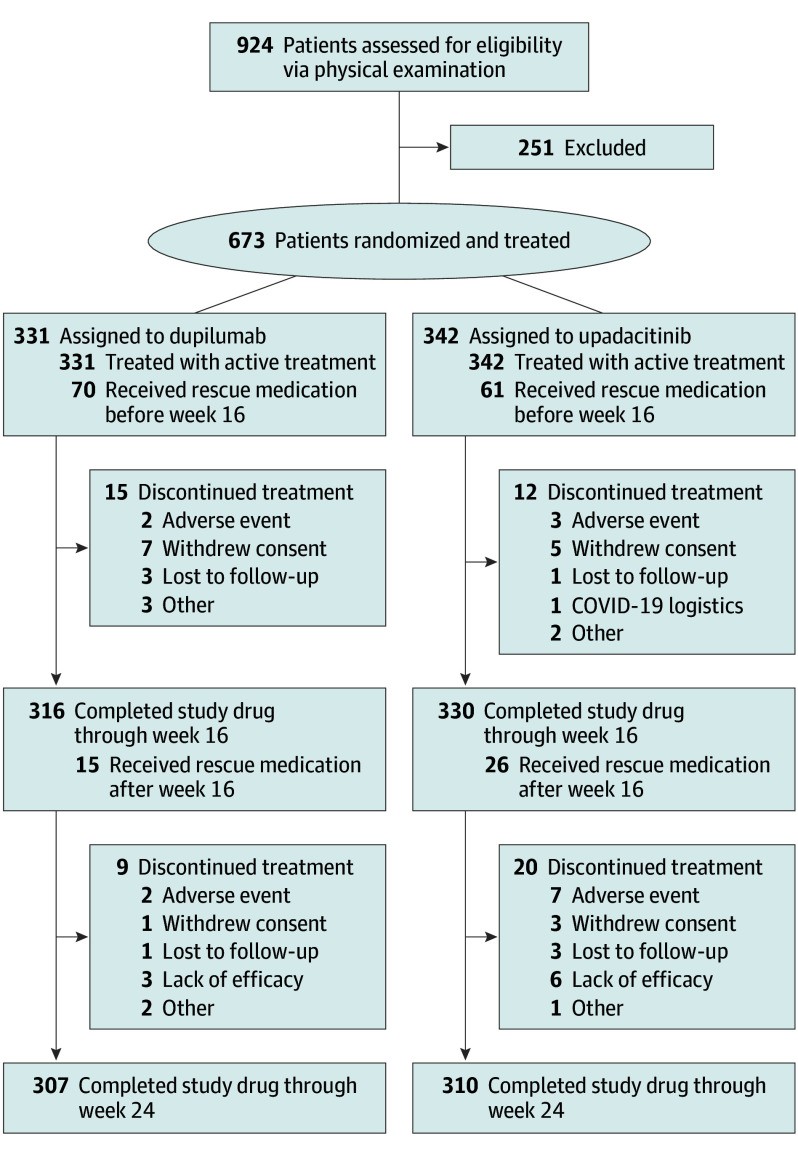

A total of 924 patients were screened, of whom 251 were excluded and 673 were enrolled and treated; 342 (183 men [53.5%]; mean [SD] age, 36.2 [14.4] years) received upadacitinib, and 331 (192 men [58.0%]; mean [SD] age, 36.3 [13.8] years) received dupilumab. The number of patients who discontinued treatment was low overall; 310 (90.6%) completed upadacitinib treatment, and 307 (92.7%) completed dupilumab treatment (Figure 1); 330 patients (96.5%) completed 16 weeks of upadacitinib treatment, and 316 patients (95.5%) completed 16 weeks of dupilumab treatment. Eighty-seven upadacitinib-treated patients (25.4%) and 85 dupilumab-treated patients (25.7%) received rescue therapy and were considered nonresponders for visits after receiving rescue therapy.

Figure 1. Patient Disposition Through Week 24.

CONSORT diagram for patient enrollment, randomization, and discontinuation. The primary reason for discontinuation is listed. EASI indicates Eczema Area and Severity Index.

Demographic and baseline characteristics were balanced among the upadacitinib-treated and dupilumab-treated groups, including key measures of disease activity: mean (SD) EASI (31.0 [12.6] and 29.2 [11.6], respectively) and proportion of patients with severe validated Investigator’s Global Assessment for AD (173 [50.6%] and 172 [52.0%], respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Disease Characteristics of Patientsa.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab, 300 mg (n = 331) | Upadacitinib, 30 mg (n = 342) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 192 (58.0) | 183 (53.2) |

| Female | 139 (42.0) | 159 (46.5) |

| Age, mean (SD) [range], y | 36.3 (13.81) [18-76] | 36.2 (14.42) [18-76] |

| Age group, y | ||

| <40 | 223 (67.4) | 228 (66.7) |

| ≥40 to <65 | 94 (28.4) | 98 (28.7) |

| ≥65 | 14 (4.2) | 16 (4.7) |

| Disease duration since diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 25.5 (14.8) | 23.6 (14.8) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 75.5 (18.6) | 78.8 (22.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 25.97 (5.80) | 26.94 (6.53)b |

| BSA, mean (SD), % | 45.4 (22.7) | 48.7 (23.9) |

| vIGA-AD score | ||

| 3 (Moderate) | 159 (48.0) | 169 (49.4) |

| 4 (Severe) | 172 (52.0) | 173 (50.6) |

| EASI, mean (SD) | 29.2 (11.6) | 31.0 (12.6) |

| Worst Pruritus NRS [weekly average], mean (SD) | 7.5 (1.7) | 7.4 (1.6) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); BSA, body surface area; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; vIGA-AD, validated Investigator’s Global Assessment.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics assessed upon entry to Heads Up (study M16-046).

Data shown for 341 patients.

Efficacy Outcomes

The proportion of patients who achieved EASI75 at week 16 was significantly greater for patients receiving upadacitinib than those receiving dupilumab (248 [72.4%] vs 207 [62.6%]; adjusted difference, 9.7% (95% CI, 2.6%-16.7%; P = .007) (Table 2), thereby meeting the primary end point of EASI75 at week 16 for superiority of upadacitinib compared with dupilumab. The response rate was calculated using the NRI-C approach. The results based on NRI-C were consistent with those based on NRI-NC (the traditional NRI approach), given that the number of patients with missing values owing to COVID-19 for the primary end point was low (1.6% [11 of 673]) (eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 2). Most patients in both treatment groups did not receive rescue therapy (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Primary and Ranked Secondary End Points.

| End point | Time point | Dupilumab, 300 mg (n = 331) | Upadacitinib, 30 mg (n = 342) | Difference | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary end point | |||||

| Achievement of EASI75a | Week 16 | 207 (62.6) [57.4 to 67.8] | 248 (72.4) [67.6 to 77.2] | 9.7 | .007 |

| Secondary end points in order of ranking | |||||

| % Change from baseline in worst pruritus NRSb | Week 16 | −49.6(2.0) [–53.5 to −45.7] | −67.8 (1.9) [–71.5 to −64.0] | −18.21 | <.001 |

| No. | 239 | 252 | |||

| Achievement of EASI100a | Week 16 | 26 (7.9) [5.0 to 10.8] | 97 (28.4) [23.6to 33.2] | 20.4 | <.001 |

| Achievement of EASI90a | Week 16 | 133 (40.3) [35.0 to 45.6] | 211 (61.6) [56.4 to 66.8] | 21.2 | <.001 |

| % Change from baseline in Worst Pruritus NRSb | Week 4 | −32.4 (2.3) [–36.9 to −27.9] | −60.4 (2.2) [–64.7 to −56.1] | −28.0 | <.001 |

| No. | 297 | 327 | |||

| Achievement of EASI75a | Week 2 | 60 (18.2) [14.0 to 22.4] | 152 (44.3) [39.1 to 49.6] | 26.1 | <.001 |

| % Change from baseline in Worst Pruritus NRSb | Week 1 | −8.9 (1.8) [–12.5 to −5.3] | −32.0 (1.8) [–35.4 to −28.5] | −23.0 | <.001 |

| No. | 314 | 331 | |||

| Worst Pruritus NRS improvement ≥4 pointsa,c | Week 16 | 117 (36.4) [31.1 to 41.6] | 188 (56.1) [50.8 to 61.5] | 19.8 | <.001 |

| No. | NA | 323 | 334 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: EASI75, 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index; NA, not applicable; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale.

No. (%) [95% CI].

Least-squares mean (SE) [95% CI].

Analyzed for patients with Worst Pruritus NRS of 4 points or higher at baseline.

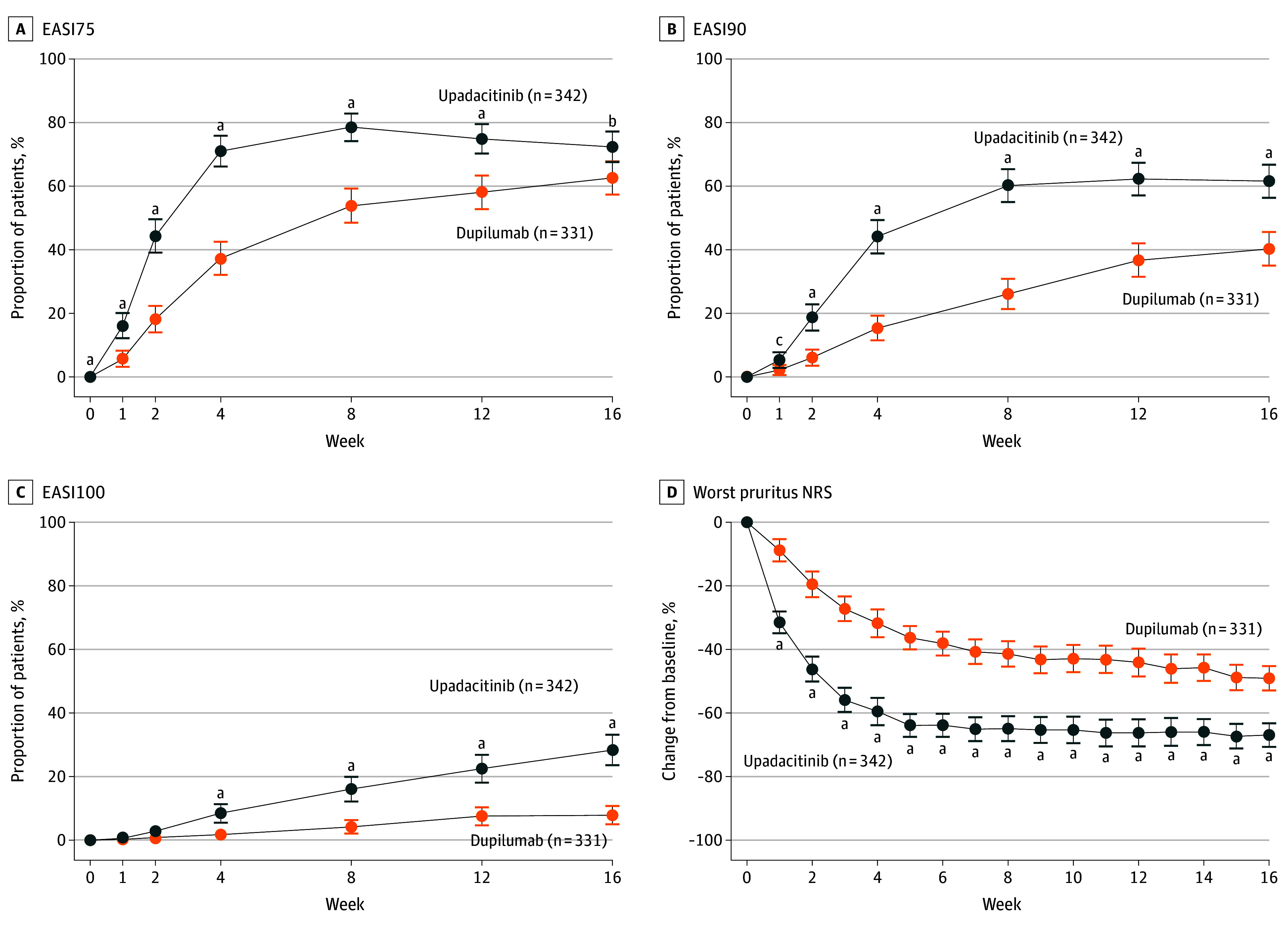

Onset of action was more rapid for upadacitinib, with the proportion of patients achieving EASI75 at week 2 significantly greater for those receiving upadacitinib compared with those receiving dupilumab (152 of 342 [44.3%] vs 60 of 331 [18.2%]; P < .001) (Table 2). Significantly greater proportions of patients achieved high levels of efficacy (EASI90 and EASI100) at week 16 with upadacitinib compared with dupilumab (EASI90, 211 [61.6%] vs 133 [40.3%]; P < .001; EASI100, 97 [28.4%] vs 26 [7.9%]; P < .001). The mean (SD) percentage improvement from baseline Worst Pruritus NRS was significantly greater for upadacitinib-treated patients compared with dupilumab-treated patients as early as week 1 (32.0% [1.8%] vs 8.9% [1.8%]; P < .001) and week 4 (60.4% [2.2%] vs 32.4% [2.3%]; P < .001), and significant differences were maintained through week 16 (67.8% [1.9%] vs 49.6% [2.0%]; P < .001). Furthermore, the proportion of patients achieving a clinically meaningful improvement in itch (Worst Pruritus NRS improvement ≥4 points from baseline) at week 16 was higher for those who received upadacitinib compared with those who received dupilumab (188 of 344 [56.1%] vs 117 of 323 [36.4%]; P < .001). Thus, the study met all ranked secondary efficacy end points, demonstrating that upadacitinib achieved significantly greater improvements in both investigator- and patient-reported outcomes compared with dupilumab.

Numerically greater proportions of upadacitinib-treated vs dupilumab-treated patients achieved EASI75 as early as week 1 (55 of 342 [16.1%] vs 19 of 331 [5.8%]) and at week 4 (243 of 342 [71.1%] vs 123 of 331 [37.3%]) (Figure 2A). Similar differences were observed for achievement of EASI90 at week 2 (64 of 342 [18.8%] vs 20 of 331 [6.1%]) and week 8 (206 of 342 [60.2%] vs 86 of 331 [26.1%]) (Figure 2B). Positive differences between proportions of upadacitinib-treated vs dupilumab-treated patients for achievement of EASI100 were also observed at week 4 (29 of 342 [8.5%] vs 6 of 331 [1.8%]) and maintained through week 16 (97 of 342 [28.4%] vs 26 of 331 [7.9%]) (Figure 2C). In addition, upadacitinib-treated patients had significantly greater reductions than dupilumab-treated patients in mean (SE) Worst Pruritus NRS as early as week 1 (−32.0% [1.8%] vs −8.9% [1.8%]) and maintained through week 16 (−67.8% [1.9%] vs −49.6% [2.0%]) (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Efficacy Over Time.

A, Proportion of patients achieving 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI75) B, Proportion of patients achieving 90% improvement in EASI (EASI90). C Proportion of patients achieving 100% improvement in EASI (EASI100). D, Mean percentage change in Worst Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for patients treated with upadacitinib or dupilumab by nonresponder imputation incorporating multiple imputation to handle missing data due to COVID-19. Error bars indicate 95% CIs (synthetic result based on t test distribution from the PROC MIANALYZE procedure in SAS if there were missing data due to COVID-19 or was based on the normal approximation to the binomial distribution if there were no missing data due to COVID-19).

aP ≤ .001.

bP ≤ .01.

cP ≤ .05.

A greater proportion of upadacitinib-treated than dupilumab-treated patients achieved EASI75 (223 of 342 [65.3%] vs 203 of 331 [61.2%]; P = .29 for upadacitinib vs dupilumab without adjustment for multiplicity) at week 24 (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). In addition, EASI90 was achieved at week 24 by 194 of 342 upadacitinib-treated patients (56.6%) and EASI100 was achieved at week 24 by 95 of 342 upadacitinib-treated patients (27.8%), while EASI90 was achieved at week 24 by 164 of 331 dupilumab-treated patients (49.5%; P = .07 for upadacitinib vs dupilumab without adjustment for multiplicity) and EASI100 was achieved at week 24 by 45 of 331 dupilumab-treated patients (13.6%; P < .001 for upadacitinib vs dupilumab without adjustment for multiplicity). Upadacitinib-treated patients also had greater improvement from baseline in mean (SD) Worst Pruritus NRS than dupilumab-treated patients at week 24 (63.7% [2.8%] vs 54.9% [2.9%]; P = .03 for upadacitinib vs dupilumab without adjustment for multiplicity).

Safety Outcomes

The safety profile of upadacitinib in this study was consistent with that observed in 1 phase 2b7 and 3 pivotal phase 3 clinical trials (Measure Up 1, Measure Up 2, and AD Up)8,9 (Table 3). No new safety risks of upadacitinib were observed in this AD study compared with other AD studies. The 16-week incidence rates of TEAEs were 72.8% in upadacitinib-treated patients (249 of 342) and 65.0% in dupilumab-treated patients (215 of 331). The rates of serious TEAEs and AEs leading to study drug discontinuation were 2.9% (10 of 342) and 2.0% (7 of 342) for upadacitinib and 1.2% (4 of 331) and 1.2% (4 of 331) for dupilumab, respectively. One death due to influenza-associated bronchopneumonia was reported in a 40-year-old upadacitinib-treated patient.

Table 3. TEAEs Through Week 16 for All Patients Receiving 1 Dose or More of Study Drug.

| TEAE | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab, 300 mg (n = 331) | Upadacitinib, 30 mg (n = 342) | |

| AE | 215 (65.0) | 249 (72.8) |

| AE with reasonable possibility of being drug-relateda | 122 (36.9) | 153 (44.7) |

| Severe AE | 14 (4.2) | 25 (7.3) |

| SAE | 4 (1.2) | 10 (2.9) |

| SAE with reasonable possibility of being drug relateda | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.2) |

| AE leading to discontinuation of study drug | 4 (1.2) | 7 (2.0) |

| AE leading to deathb | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| AEs of special interest | ||

| Serious infections | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.1) |

| Opportunistic infection, excluding tuberculosis and herpes zosterc | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Herpes zoster | 3 (0.9) | 7 (2.0) |

| Active tuberculosis | 0 | 0 |

| Nonmelanoma skin cancerd | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Malignant neoplasm, excluding NMSC | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic disordere | 4 (1.2) | 10 (2.9) |

| Adjudicated gastrointestinal perforations | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia | 1 (0.3) | 7 (2.0) |

| Neutropenia | 2 (0.6) | 6 (1.8) |

| Lymphopenia | 0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Creatine phosphokinase elevation | 10 (3.0) | 23 (6.7) |

| Renal dysfunction | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events | 0 | 0 |

| Adjudicated venous thromboembolic events | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs reported by ≥5% in either treatment group | ||

| Acnef | 9 (2.7) | 55 (16.1) |

| Dermatitis atopic | 29 (8.8) | 24 (7.0) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 13 (3.9) | 22 (6.4) |

| Blood CPK level increased | 10 (3.0) | 23 (6.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 22 (6.6) | 20 (5.8) |

| Headache | 21 (6.0) | 14 (4.1) |

| Conjunctivitis | 29 (8.8) | 5 (1.5) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; NMSC, nonmelanoma skin cancer; SAE, serious AE; TB, tuberculosis; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

As assessed by investigator.

A 40-year-old woman who had bronchopneumonia associated with influenza A was found deceased at home on study day 70.

All opportunistic infections were eczema herpeticum.

Keratoacanthoma, no reasonable possibility of association with study drug according to the investigator.

Hepatic disorders: most were elevated transaminase levels.

Most acne events consisted primarily of inflammatory papules, pustules, and comedones, involving the face. All events were nonserious. None led to treatment discontinuation.

Through 16 weeks of treatment, the most frequently reported AE among patients treated with upadacitinib was acne (55 [16.1%]), whereas acne was reported by 9 patients treated with dupilumab (2.7%) (Table 3). All acne events were mild or moderate in severity, primarily involved the face and trunk, and did not result in scarring; none led to study drug discontinuation. The most frequently reported AE among patients treated with dupilumab was conjunctivitis (29 [8.8%]), whereas conjunctivitis was reported by 5 patients treated with upadacitinib (1.5%). All conjunctivitis cases were mild or moderate in severity, and none led to study drug discontinuation.

Among AEs of special interest, rates of serious infection (4 [1.1%] vs 2 [0.6%]), eczema herpeticum (1 [0.3%] vs 0%), and herpes zoster (7 [2.0%] vs 3 [0.9%]) were numerically higher for patients treated with upadacitinib than those treated with dupilumab, all at generally low levels (Table 3). Each of the serious infections was reported in a single patient. No eczema herpeticum or herpes zoster event was considered to be serious. All herpes zoster events were mild or moderate in severity, and none led to study drug discontinuation. Most herpes zoster events involved a single dermatome; 2 herpes zoster events involved 3 or more dermatomes, and 1 had ophthalmic involvement (periorbital skin) in the upadacitinib group.

The rate of hepatic disorders was higher among patients treated with upadacitinib than those treated with dupilumab (10 [2.9%] vs 4 [1.2%]) (Table 3). Most of the hepatic disorders were transaminase elevations that were mild or moderate in severity, transient, and reported as singular abnormalities without recurrence; none were serious, and 2 upadacitinib-treated patients discontinued study drug owing to transaminase elevation. Rates of anemia (7 [2.0%] vs 1 [0.3%]), neutropenia (6 [1.8%] vs 2 [0.6%]), and creatinine phosphokinase elevations (23 [6.7%] vs 10 [3.0%]) were higher for patients treated with upadacitinib than those treated with dupilumab, respectively. There was a single event of thrombocytopenia (grade 1 in severity) reported in a patient treated with upadacitinib. Most of these laboratory test–related AEs were mild or moderate in severity, transient, and reported as singular abnormalities without recurrence, with only 1 event deemed serious (decreased hemoglobin reported in the dupilumab-treated group); none of these events led to study drug discontinuation. No drug-induced liver injury or rhabdomyolysis events were reported.

One case of malignant neoplasm was reported in each treatment group: 1 breast carcinoma in a 68-year-old upadacitinib-treated patient (after week 16; eTable 6 in Supplement 2) and 1 keratoacanthoma in a 69-year-old dupilumab-treated patient. No cases of adjudicated venous thromboembolic events, major adverse cardiovascular events, active tuberculosis, or gastrointestinal perforation were reported in either treatment group. Safety data through the end of the monitoring period are summarized in eTable 6 in Supplement 2.

Five nonserious cases of COVID-19 were reported during the study—4 in the upadacitinib group and 1 in the dupilumab group. Treatment was temporarily interrupted for 3 upadacitinib patients and resumed after resolution of the infection. Treatment was not interrupted for the fourth upadacitinib patient or the dupilumab patient.

Discussion

To our knowledge, Heads Up is the first study directly comparing upadacitinib with dupilumab for AD and is now the sixth clinical trial examining upadacitinib for the indication. This study met the primary end point of EASI75 at week 16 and all ranked secondary end points, demonstrating superiority of upadacitinib vs dupilumab for the treatment of adults with moderate-to-severe AD. The most significant differences between upadacitinib and dupilumab were in the rapidity of onset and the ability to better achieve high levels of skin clearance (eg, EASI90 and EASI100). At week 24, upadacitinib-treated patients continued to show numerically better results compared with dupilumab-treated patients for measures of skin clearance and itch relief. Upadacitinib was generally safe and well tolerated with no new safety risks observed.

Despite the approval of dupilumab in recent years, there remains an unmet need for therapies that provide better efficacy outcomes, such as clear or almost clear skin, for patients with moderate-to-severe AD. Achievement of higher levels of efficacy in AD is associated with greater improvements in health-related quality of life.12 The relatively high proportions of patients treated with upadacitinib achieving EASI90 and EASI100 at week 16, reported here and elsewhere,7,8,9 may become important regarding future AD treatment goals. A similar shift has occurred in recent years with the treatment of patients with another chronic inflammatory skin disease, psoriasis, where treatment success shifted from 75% improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index to 90% and 100% improvement (PASI90 and PASI100, respectively). As the effectiveness of new drugs for psoriasis have improved, the higher relative improvement scores PASI90 and PASI100 have become the benchmark for systemic therapies, and we expect to see a similar trend in AD treatment benchmarks.

Treatment effect (including skin and itch improvement) was also experienced more rapidly with upadacitinib compared with dupilumab. Statistically significant skin improvement as measured by EASI75 was attained as early as week 2 with upadacitinib, and significantly higher rates of clinically meaningful improvements in itch were reported as early as week 1. It is well established that patients prefer treatments with a rapid onset of action.13,14,15 Upadacitinib-treated patients achieved significantly higher rates of the stringent skin improvement thresholds EASI90 and EASI100 compared with dupilumab.

Several key inflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of AD signal via JAK1, including IL-4 and IL-13 (epidermal barrier dysfunction), IL-22 (epidermal hyperproliferation), IL-31 (itch neuron stimulation), IFN-γ (lesion chronicity), and TSLP (TH2 cell differentiation).3,4,16 Dupilumab targets the shared IL-4 and IL-13 receptor. By selectively inhibiting JAK1, upadacitinib abrogates the signaling of a wider range of proinflammatory mediators, including IL-4, IL-13, IL-22, IL-31, IFN-γ, and TSLP. The simultaneous inhibition of multiple pathways may contribute to the efficacy and rapidity effects of upadacitinib compared with dupilumab.

The safety profile of upadacitinib in this study was consistent with that noted in 1 phase 2b trial7 and 3 pivotal phase 3 clinical trials (Measure Up 1, Measure Up 2, and AD Up),8,9 with no new safety risks observed. In contrast to previous studies of JAK inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, higher rates of acne were reported in studies of upadacitinib in patients with AD. Of note, acne has also been among the most frequently reported TEAEs for other JAK inhibitors in AD (abrocitinib and baricitinib); the mechanism underlying this AE is unclear.17,18,19 The rate of study drug discontinuation secondary to AEs was numerically higher with upadacitinib. Rates of serious infection, eczema herpeticum, herpes zoster, and laboratory-test–related AEs were numerically higher with upadacitinib, while the rates of conjunctivitis and injection-site reactions were numerically higher with dupilumab. No venous thromboembolic events, major adverse cardiovascular events, or gastrointestinal perforations were reported with either treatment. Overall, these observations were consistent with the known safety profile of each drug.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The data reported here are results through 24 weeks of treatment, with primary and ranked secondary end points at week 16. Longer-term data are being collected in a separate open-label extension study. Although not necessarily a limitation, this study evaluated both upadacitinib and dupilumab as monotherapy treatments, and patients who received any topical agent as rescue therapy were treated as nonresponders after receipt of rescue therapy. In real-world practice, many patients use systemic therapies in combination with topical therapies20; concomitant use of topical corticosteroids is addressed in a separate study of upadacitinib for AD.9

To maintain blinding, the monotherapy treatments of oral upadacitinib and subcutaneous dupilumab were each accompanied by a placebo for the opposite therapy, but there was no comparison against placebo as tested in the pivotal studies of these treatments. When dupilumab, 300 mg every 2 weeks, was given as monotherapy in SOLO1 and SOLO2, 51% and 44% of patients, respectively, achieved EASI75 at week 16 when compared with 15% and 12% for placebo, respectively.5 Higher response rates for dupilumab may have been observed in the present study owing to the lack of a placebo comparator and subsequent responder or efficacy assessor bias. However, this potential bias did not seem to impact response rates in the upadacitinib group; in the upadacitinib placebo-controlled monotherapy studies, Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2, 79.7% and 72.9% of patients treated with upadacitinib, 30 mg once daily, achieved EASI75 at week 16, respectively, compared with 16.3% and 13.3% for placebo, respectively.8

Conclusions

Overall, upadacitinib was well tolerated and provided superior efficacy compared with dupilumab after 16 weeks of treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe AD. Upadacitinib achieved higher levels of skin clearance and itch relief with a more rapid onset of action vs dupilumab. Upadacitinib is an effective treatment option for patients with moderate-to-severe AD and may help inform future treatment decisions.

Trial Protocol

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Graphical Approach for Multiplicity Adjustment

eTable 1. Eligibility Criteria

eTable 2. Number of Patients Becoming Responders After Implementation of the “Before-and-After” Imputation Rule

eTable 3. Distance From Adjacent EASI Scores to the Week 16 Analysis Window for EASI 75

eTable 4. Proportion of Patients Receiving 1 or More Rescue Therapy

eTable 5. Efficacy at Week 24 (Unranked)

eTable 6. Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Through End of Monitoring Period

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):345-360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell MD, Kuo FI, Smith PA. Targeting the Janus kinase family in autoimmune skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2342. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He H, Guttman-Yassky E. JAK inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(2):181-192. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0413-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. ; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators . Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335-2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parmentier JM, Voss J, Graff C, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of the JAK1 selectivity of upadacitinib (ABT-494). BMC Rheumatol. 2018;2:23. doi: 10.1186/s41927-018-0031-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Pangan AL, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(3):877-884. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2151-2168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reich K, Teixeira HD, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD Up): results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2169-2181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00589-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovener (Stockholm). 1980;60(92):44-47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverberg JI, Lei D, Yousaf M, et al. What are the best endpoints for Eczema Area and Severity Index and Scoring Atopic Dermatitis in clinical practice? a prospective observational study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(5):888-895. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitt J, Csötönyi F, Bauer A, Meurer M. Determinants of treatment goals and satisfaction of patients with atopic eczema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6(6):458-465. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06609.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverberg JI, Kantor RW, Dalal P, et al. A comprehensive conceptual model of the experience of chronic itch in adults. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(5):759-769. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0381-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Augustin M, Langenbruch A, Blome C, et al. Characterizing treatment-related patient needs in atopic eczema: insights for personalized goal orientation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(1):142-152. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung DY, Guttman-Yassky E. Deciphering the complexities of atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in treatment approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):769-779. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(8):863-873. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):255-266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30732-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson EL, Lacour JP, Spelman L, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(2):242-255. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis, section 2: management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Graphical Approach for Multiplicity Adjustment

eTable 1. Eligibility Criteria

eTable 2. Number of Patients Becoming Responders After Implementation of the “Before-and-After” Imputation Rule

eTable 3. Distance From Adjacent EASI Scores to the Week 16 Analysis Window for EASI 75

eTable 4. Proportion of Patients Receiving 1 or More Rescue Therapy

eTable 5. Efficacy at Week 24 (Unranked)

eTable 6. Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events Through End of Monitoring Period

Data Sharing Statement