Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Punctate ischemic lesions noted on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) are associated with poor functional outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Whether these lesions increase long-term risk of stroke is poorly understood.

Methods:

We pooled individual patient data from the Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage (ATACH-2) trial, and the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation phase 3 trial (MISTIE III). We included subjects with a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The exposure was a DWI lesion. The primary outcome was any stroke, defined as a composite of ischemic stroke or recurrent ICH, while secondary outcomes were incident ischemic stroke and recurrent ICH. Using multivariate Cox regression analysis, we evaluated the risk of stroke.

Results:

Of 505 ICH patients with MRI, 466 were included. DWI lesions were noted in 214 (45.9%) subjects, and 34 incident strokes (20 ischemic stroke and 14 recurrent ICH) were observed during a median follow up of 324 days (interquartile range, 91- 374). Presence of a DWI lesion was associated with a 6.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.2-11.6) absolute increase in risk of all stroke (hazard ratio [HR], 2.6; 95% CI, 1.2-5.7). Covariate adjustment with Cox regression models also demonstrated this increased risk. In the secondary analyses, there was an increased risk of ischemic stroke (HR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.1-11.0), but not recurrent ICH (HR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.6-5.1).

Conclusions:

In a heterogeneous cohort of ICH patients, presence of a DWI lesion was associated with a 2.5-fold heightened risk of stroke among ICH survivors. This elevated risk persisted for ischemic stroke, but not for recurrent ICH.

Keywords: Intracerebral hemorrhage, magnetic resonance imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging, ischemic stroke

Acute vascular events are the second most common cause for hospital readmission after an index intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH).1, 2 In fact, patients with ICH face a 3- to 6-fold heightened risk of ischemic stroke in the first year.3, 4 Punctate ischemic lesions are observed on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) in up to 40% of patients with DWI in the acute phase, and in nearly a third of patients even after 1 month.5-7 DWI lesions have been ascribed to ICH-mediated hypercoagulability and acute blood pressure fluctuations, but emerging evidence supports underlying cerebral small vessel disease as the likely prevailing mechanism.8 A recent meta-analysis showed that hematoma location or underlying etiology (hypertension vs. amyloid angiopathy) did not influence the prevalence of DWI lesions after ICH.9 From a prognostic standpoint, DWI lesions are linked to major disability or death after ICH, particularly among patients with a deep hematoma.10, 11 While these lesions are believed to be ischemic in origin, whether they portend a higher risk of future stroke is poorly understood. We hypothesized that presence of a DWI lesion is associated with a higher risk of stroke among ICH survivors, and sought to study this relationship using prospective data from two ICH cohorts.

Methods

Data Availability

De-identified MISTIE III and ATACH-2 trial data are available at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke data archive. To gain access, requesters will need to submit a proposal and sign a data-access agreement.

Study Design

We pooled individual patient-level data from patients with ICH enrolled in two clinical trials, the Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage (ATACH-2) trial,12, 13 and the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation phase 3 trial (MISTIE III).14 An ethics committee approved the trial protocols at each enrolling site, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant or the legal surrogate. The study was also approved by the institutional review board of Weill Cornell Medicine. This study was performed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting observational studies (Online Only Supplemental Files).15

Study Source and Patient Population

MISTIE III was a randomized, controlled, open-label, blinded endpoint trial that found image guided, minimally invasive surgery followed by gentle thrombolytic irrigation of the catheterized intracerebral hemorrhage clot decreased mortality, but was neutral on the primary endpoint of improved functional outcome in patients with moderate to large ICH, compared to standard medical management.14 ATACH-2 was a randomized, multicenter, open-label trial to determine the relative efficacy of intensive versus standard blood pressure management initiated within 4.5 hours after symptom onset and continued for the next 24 hours in patients with spontaneous supratentorial ICH.12 The trial found no difference in the primary endpoint of death or major disability at 90 days. In this study, we included all ICH patients who had an available magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed during hospitalization for ICH.

Measurements

Patients enrolled in the MISTIE III trial had one of two protocolized MRI scans obtained during hospitalization, on day of randomization or, if not available, then at 7-10 days after randomization. 16 MRI scans in the ATACH-2 trial were obtained at the discretion of the treating physicians.17 The MRI scans were typically performed on 1.5T to 3.0T scanners with gradient recalled echo or susceptibility-weighted imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging with apparent diffusion coefficient mapping, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences. Neuroimaging data was adjudicated centrally within each trial by a panel of trained radiologists and neurologists, blinded to the intervention and outcome. Neuroimaging data obtained for this study included DWI lesions, cerebral microbleeds, and leukoaraiosis. Fazekas score was used to grade white matter hyperintensities.18 The scores in the periventricular and deep areas were added to obtain the total Fazekas score. Moderate to severe leukoaraiosis was then defined as a total score between 3 and 6 in both cohorts.19 This method of quantifying white matter hyperintensities has been previously shown to have good inter-rater reliability (90% agreement, Cohen κ 0.73) for white matter hyperintensities using the Fazekas scale.20

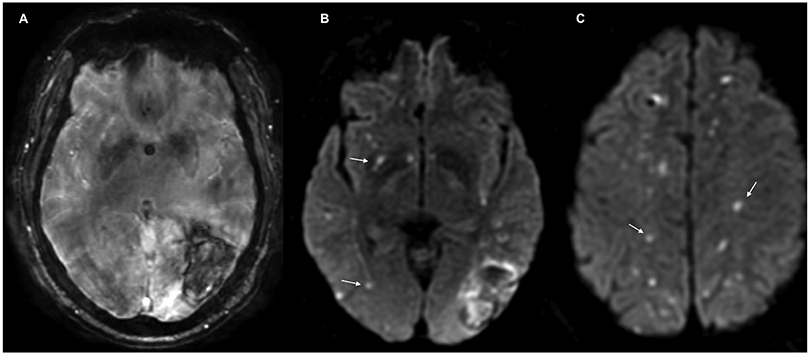

The exposure in our study was presence of a DWI lesion, defined as a high-signal intensity lesion on DWI, with a corresponding low-signal intensity on apparent diffusion coefficient mapping, excluding a 1cm rim immediately surrounding the hematoma (Figure 1). Lesions without corresponding hypointense signals on the apparent diffusion coefficient were not adjudicated. All MRI images in the MISTIE III cohort were reviewed independently by three trained investigators blinded to clinical and outcome data; disagreements were adjudicated by a third blinded reviewer. The mean interrater agreement for all markers in 10% of randomly selected MRI scans was 0.82. Similarly, the ATACH-2 investigators have previously demonstrated excellent inter-rater agreement for the presence of DWI lesions (kappa=0.82, p<0.001).21

Figure 1:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of an Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Susceptibility weighted angiography (SWAN) showing the hematoma (Panel A), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences showing hyperintense lesions (Panels B and C).

The primary outcome was any stroke, defined as a composite of ischemic stroke or recurrent ICH, while secondary outcomes were incident ischemic stroke and recurrent ICH. The outcomes were defined as new focal neurological deficits with neuroimaging confirmation of infarct or hemorrhage. These events were reported as adverse events by the enrolling site investigators, and adjudicated by the safety events committee within each trial. Additionally, in the MISTIE III cohort, recurrent intracranial hemorrhage events included catheter tract hemorrhage, subdural and subarachnoid hemorrhage, and tissue or intraventricular hemorrhage. For this analysis, we only considered tissue or intraventricular hemorrhage as recurrent ICH. Finally, in the pooled cohort, ICH events that occurred in the first 14 days were excluded due to concerns that they were likely related to surgical intervention or fibrinolysis. Only outcomes occurring after MRI were considered in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were described using standard descriptive statistics. Pearson Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables; the Student’s t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test were used for continuous variables depending on the normality of distribution. Kaplan-Meier statistics were used to estimate the incidence of stroke among participants with and without DWI lesions. To examine the association between DWI lesions and stroke, we used Cox regression analysis.

Given that there were 34 stroke outcomes, we built 4 different models adjusting for 3 covariates at a time, chosen a priori, so as to prevent over fitting of the model. The first model included age, admission ICH volume, and hematoma location; the second included age, atrial fibrillation, and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack; and the third had age, leukoaraiosis, and microbleeds. In the fourth model, we included hypertension, race, and intraventricular hemorrhage. These covariates were chosen based on their known associations with the occurrence of DWI lesions, and their demonstrated link to ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. 10,22 Similarly, secondary analyses were performed ensuring not to overfit the Cox regression models. Log-log plots were constructed to ensure that the proportional hazard assumption was not violated. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp. Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2019). The threshold for statistical significance was p<0.05.

Results

Study Population

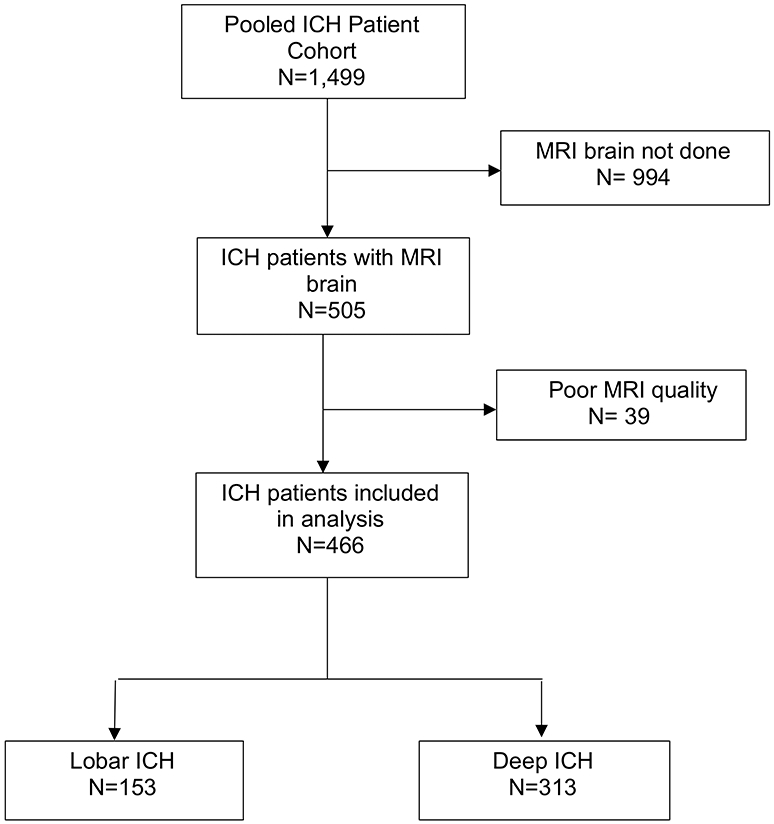

The pooled cohort included a total of 1,499 ICH patients, of whom 505 had an MRI scan (Figure 2). Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients who received an MRI scan and those who did not in the two trials, is shown in Supplemental Tables I and II. Among the 466 ICH patients included in the final analysis, 153 (32.8%) had a lobar ICH and 313 (67.2%) had a deep ICH. The mean age of the cohort was 61 years (standard deviation, 12.4); there were 183 females (39.3%). Baseline characteristics of ICH patients in the ATACH-2 and MISTIE III trials are shown in Table 1. DWI lesions were observed in 214 patients (46.4%), of which 71 (33.1%) were lobar, 50 (23.4%) were deep, and 93 (43.5%) were both lobar and deep. Compared to patients without DWI lesions, those with these lesions more often had hypertension, prior anticoagulant medication use, larger ICH volumes, intraventricular hemorrhage, and leukoaraiosis (Table 2).

Figure 2:

Flowchart Showing Patient Selection

Abbreviations: DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of ICH Patients, Stratified by Study Cohort

| Characteristic | ATACH-2 (n=178) |

MISTIE IIIb (N = 288) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61.5 (12.9) | 60.6 (12.3) |

| Female | 67 (37.6) | 116 (40.8) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 63 (35.6) | 175 (61.2) |

| Black | 33 (18.6) | 54 (18.9) |

| Other | 81 (45.8) | 59 (19.9) |

| Hypertension | 135 (75.8) | 279 (97.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 37 (20.8) | 90 (31.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 54 (30.3) | 111 (38.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (1.1) | 18 (6.3) |

| Prior ischemic stroke | 32 (17.9) | 8 (2.8) |

| Prior antiplatelet therapyb | NA | 95 (33.2) |

| Prior anticoagulation therapyb | NA | 19 (6.6) |

| Glasgow Coma Scalea | 15 (14-15) | 10 (8-13) |

| Hematoma volume, baseline, mLa | 10.9 (5.8-22.5) | 41.8 (30.9-53.2) |

| Presence of IVH | 40 (22.5) | 122 (42.7) |

| ICH location | ||

| Lobar | 42 (23.6) | 111 (38.8) |

| Deep | 136(76.4) | 177 (61.2) |

| Ictus to MRI, daysa | 1.5 (0.5-4.8) | 2 (1-7) |

| DWI lesions | 46 (25.8) | 168 (58.7) |

| Presence of cerebral microbleeds | 113 (63.5) | 118 (40.9) |

| Leukoaraiosis, moderate to severec | 163 (91.5) | 82 (28.7) |

Abbreviations: DWIHL, diffusion-weighted imaging hyperintense lesions; INR, international normalized ratio; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; mL, millilitres; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

All values represented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

indicates data presented as median (interquartile range)

Data were available for286 patients in MISTIE III for some of the variables.

moderate to severe leukoaraiosis was defined as a combined periventricular and deep white matter score >3

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of ICH Patients, Stratified by Presence of DWI Lesions

| Characteristic | DWI Lesions (n=214) |

No DWI Lesions (N = 252) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 59.9 (12.0) | 61.9 (12.7) | 0.13 |

| Female | 79 (36.9) | 104 (41.3) | 0.23 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 113 (2.8) | 125 (49.6) | <0.001 |

| Black | 54 (25.2) | 34 (13.5) | |

| Other | 47 (22.0) | 93 (36.9) | |

| Hypertension | 201 (93.9) | 215 (85.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 66 (30.8) | 61 (24.2) | 0.25 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 77 (35.9) | 88 (34.9) | 0.23 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10 (4.6) | 10 (3.9) | 0.75 |

| Prior ischemic stroke | 40 (18.2) | 33 (12.9) | 0.11 |

| Prior antiplatelet therapyb | 50 (29.8) | 45 (36.9) | 0.14 |

| Prior anticoagulation therapyb | 7 (4.2) | 12 (10.2) | 0.04 |

| Glasgow Coma Scalea | 10 (8-13) | 14 (11-15) | <0.001 |

| Hematoma volume, baseline, mLa | 36.9 (25.2-52.0) | 26.2 (8.9-39.3) | <0.001 |

| Presence of IVH | 88 (41.1) | 74 (29.4) | <0.001 |

| ICH location | |||

| Lobar | 73 (34.1) | 80 (31.7) | 0.63 |

| Deep | 141 (65.9) | 172 (68.3) | |

| Ictus to MRI, daysa | 2 (1-7) | 1.2 (0.5-5.5) | 0.11 |

| Presence of cerebral microbleeds | 104 (48.5) | 127 (50.4) | 0.99 |

| Leukoaraiosis, moderate to severec | 99 (46.3) | 146 (55.1) | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: DWIHL, diffusion-weighted imaging hyperintense lesions; INR, international normalized ratio; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; mL, millilitres; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

All values represented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

indicates data presented as median (interquartile range)

data available on 300 patients only

moderate to severe leukoaraiosis was defined as a combined periventricular and deep white matter score >2

Primary Outcome

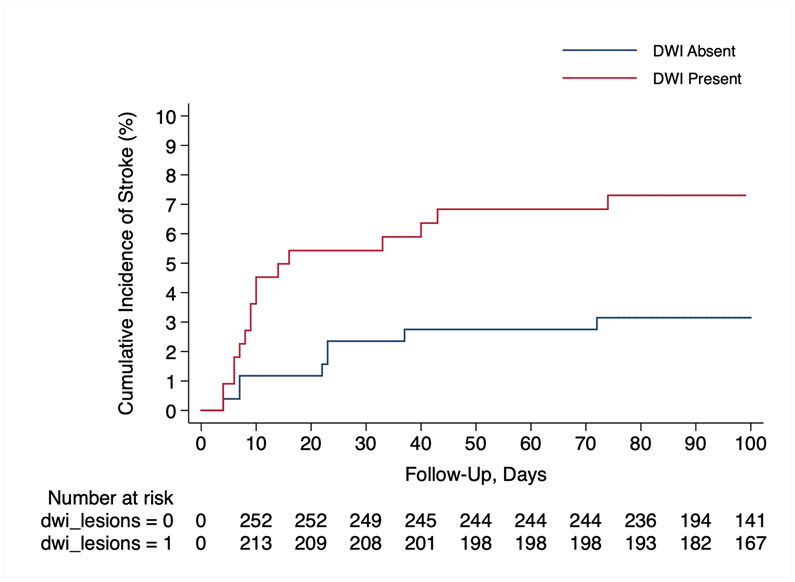

During a median follow up of 324 days (interquartile range, 91-374), there were 34 incident strokes. In the unadjusted Cox analysis, presence of a DWI lesion was associated with a 6.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.2-11.6) absolute increase in risk of all stroke (hazard ratio [HR], 2.6; 95% CI, 1.2-5.7) (Figure 3). We used 4 multivariate Cox regression models to assess composite stroke outcomes ensuring that the models were not over fitted; first, after adjusting for age, ICH volume, and hematoma location, presence of a DWI lesion was associated with an increased risk of stroke (hazard ratio [HR], 2.5; 95% CI, 1.1-5.5). Second, we controlled for age, atrial fibrillation, and prior stroke (HR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.2-5.6), and third, age, leukoaraiosis, and cerebral microbleeds were included (HR, 2.5 95% CI, 1.1-5.4). Lastly, in the fourth model, covariates included hypertension, presence of intraventricular hemorrhage, and Black race (HR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.1-5.1). Since amyloid angiopathy and superficial siderosis are markers of ICH recurrence risk, we performed 2 post hoc analyses using these covariates. However, this information was only available in the MISTIE III cohort. Using modified Boston criteria, 43 patients met criteria for “probable CAA” and 176 had “possible CAA”. Cortical superficial siderosis was noted in 38 (13%) of patients. We additionally adjusted for age, lobar ICH, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (HR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.4-4.4), and similarly, age, lobar ICH, and cortical superficial siderosis (HR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.3-4.0).

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve Showing Risk of an Ischemic Stroke Among ICH Patients with and without DWI Lesions.

Abbreviations: DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage.

Secondary Outcomes

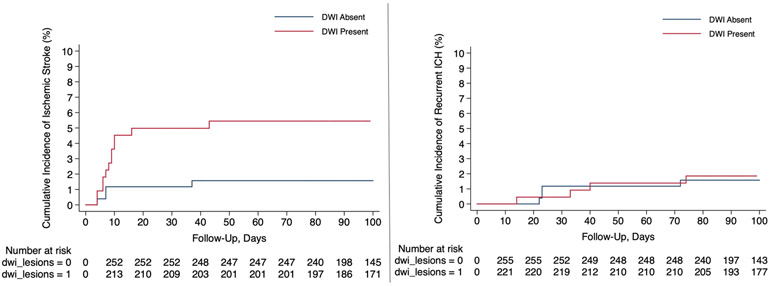

There were 20 incident ischemic strokes. In the unadjusted Cox analysis, presence of a DWI lesion was associated with a higher risk of ischemic stroke (HR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.2-11.4) (Figure 4). We constructed 4 different multivariate Cox regression models adjusting for 2 covariates at a time to make sure the models were not over fitted. DWI lesions were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke in all 4 models- (i) age and ICH volume, (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.2-12.4); (ii) age and hematoma location (HR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.2-11.1); (iii) age and atrial fibrillation (HR, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.3-11.8); and (iv) hypertension and black race (HR 3.4; 95% CI, 1.1-10.5). We observed 14 recurrent ICH events occurred during follow-up. Given the low number of outcome events, we could not include any covariates in the models. In the unadjusted Cox regression analysis, the risk of recurrent ICH was similar regardless of the DWI lesion status (HR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.6-5.1).

Figure 4:

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves Showing Risk of Stroke Subtypes Among ICH Patients with and without DWI Lesions; Risk of Ischemic Stroke (Left Panel) and Risk of Recurrent ICH (Right Panel).

Abbreviations: DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage.

Discussion

In a large prospective cohort of ICH patients, presence of a DWI lesion was associated with a heightened risk of subsequent stroke. This increased risk was observed for ischemic stroke, but not for recurrent ICH.

Several prior studies have evaluated factors associated with DWI lesions, and the influence of these lesions on functional outcomes.6, 10, 23 However, the long-term implications of these lesions from the standpoint of future stroke events is not well documented and poorly understood. In a small cohort study of 97 ICH patients with a follow-up of 42 months, DWI lesions were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke; one significant caveat was that there were only 5 ischemic strokes and 1 recurrent ICH event, which precluded adjusting for covariates.24 Additionally, the study included patients with small hematomas (median ICH volume of 6.1 mL). In the context of these limitations, our study using pooled prospective data on small and large ICHs, from two large randomized trials with blinded assessment of exposure and outcomes, provides important findings to further implicate DWI lesions as risk markers for future ischemic events among ICH survivors.

We and others have shown that pre-existing cerebral small vessel disease likely plays a key role in the incidence of DWI lesions after ICH, as evidenced by the strong independent associations with cerebral microbleeds and white matter hyperintensities.10, 11 Furthermore, imaging markers of small vessel disease are linked to future ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.22 The present study had only 34 outcome events which prevented a comprehensive evaluation of all possible vascular risk factors and interactions. Additionally, the lack of association between DWI lesions and risk of recurrent ICH needs to be interpreted cautiously due to a low event rate, attributable to the higher proportion of deep ICHs in our study. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that DWI lesions may aid in the early identification of the subset of ICH patients at high risk of subsequent ischemic events. Larger prospective confirmation of our results could help tailor existing secondary stroke prevention therapies after ICH. For instance, in the MRI sub study of the REstart or STop Antithrombotics Randomised Trial (RESTART), resumption of antiplatelet therapy had a non-significant trend toward lower ICH recurrence among patients with a significant burden of white matter hyperintensities.25 Similar trends were observed in a small multicenter randomized trial in patients without prior ICH, where aspirin use suggested possible benefit in reducing the incidence of covert brain infarction, compared to no antiplatelet therapy.26

Our study has several important limitations. First, inclusion of data from clinical trials with stringent inclusion criteria may limit generalization to a broad population with ICH. This may explain the younger age and race-specific differences noted in our study. Second, although the study had nearly 500 ICH patients with MRI scans and prospectively adjudicated outcomes, the low number of events, as stated previously, limited the number of covariates in the Cox models, but it is reassuring that regardless of the combination of covariates, the HR remained the same. However, given that there were very few recurrent ICH events (n=14), we could not perform multivariate analyses to assess the relationship between DWI lesions and recurrent ICH. Third, we lacked information on antithrombotic medication use after ICH, a proven therapy for secondary stroke prevention.27 Fourth, given the highly selective nature of the trial cohorts, majority of the patients in our study had hypertensive ICH and not cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related ICH; the composite stroke risk therefore may be an underestimation since amyloid angiopathy is independently associated with recurrent ICH.28 On a similar note, due to the overwhelming majority of hypertensive ICHs very few patients had cortical superficial siderosis, an independent predictor of ICH recurrence, and prevented inclusion as a covariate in the multivariate analyses. Finally, underestimation of the frequency of DWI lesions is a possibility due to variability in timing of MRI scans across the trials. Additionally, our study may be subject to confounding by indication, in that MRI scans were performed in patients perceived to have less severe ICH or better outcomes, and were largely performed immediately after presentation (Supplemental Tables I and II).

Conclusions

In a large prospective cohort of ICH patients, presence of a DWI lesion in the acute phase of ICH was associated with an increased risk of subsequent ischemic stroke. Further study of the link between DWI lesions and subsequent ischemic stroke may yield new strategies for improving long-term recovery after ICH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank the patients involved in the ATACH-2 and MISTIE III trials, their families, and the investigators and coordinators who cared for them.

Funding/Support:

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the corresponding author (K23NS105948) and Dr. Hanley (U01NS080824 and U24TR001609). The NIH also funded the two trials (MISTIE III U01-NS080824, and ATACH-2 U01-NS062091 and NS073344). The funding entities had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosures:

AG reports non-financial support from GE Healthcare and non-financial support from Siemens Medical Solutions outside the submitted work. CI has served on the scientific advisory board for Broadview Ventures. GJF is supported by the NIH (K76AG059992, R03NS112859), the American Heart Association (18IDDG34280056), the Yale Pepper Scholar Award (P30AG021342) and the Neurocritical Care Society Research Fellowship. KNS reports grants by the NIH (U24NS107215, U24NS107136, RO1NR018335, and U01NS106513), AHA, Bard, Biogen, Hyperfine, Novartis, personal fees from Zoll, Alva, and Ceribell outside the submitted work. JNG reports personal fees from Portola, CSL Behring, Octapharma, Phillips, personal fees and non-financial support from NControl and Takeda, and grants from Pfizer outside the submitted work. DFH is supported by the NIH (U01NS080824 and U24TR001609), and reports personal fees from Op2Lysis, personal fees from BrainScope and Neurotrope, and non-financial support from Genentech outside the submitted work. HK reports serving as co-PI for the NIH-funded ARCADIA trial (NINDS U01NS095869) which receives in-kind study drug from the BMS-Pfizer Alliance for Eliquis® and ancillary study support from Roche Diagnostics, serving as Deputy Editor for JAMA Neurology, serving as a steering committee member of Medtronic's Stroke AF trial (uncompensated), serving on an endpoint adjudication committee for a trial of empagliflozin for Boehringer-Ingelheim, and having served on an advisory board for Roivant Sciences related to Factor XI inhibition. WCZ is supported by the NIH (1U01NS080824, U01NS106513, R01 NS102583), and receives consulting fees from C.R. Bard, Inc. and Portola Pharmaceuticals outside of the area of work commented on here. JNG has received research support from NIH, Pfizer, Octapharma, and consulting fees from Phillips, CSL Behring, Portola, and NControl. All remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ATACH-2

Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage (ATACH-2) trial

- DWI

diffusion-weighted imaging

- ICH

intracerebral hemorrhage

- MISTIE III

Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation phase 3 trial

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

Footnotes

Supplemental Materials:

1. Supplemental Tables I and II

2. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist

References

- 1.Liotta EM, Singh M, Kosteva AR, Beaumont JL, Guth JC, Bauer RM, Prabhakaran S, Rosenberg NF, Maas MB, Naidech AM. Predictors of 30-Day Readmission after Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Single-Center Approach for Identifying Potentially Modifiable Associations with Readmission. Crit Care Med. 2013;2762–2769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen T, Liu B, Wan X, Zhang X, Zhang J, Zhou X, Lau AYL, Zhang Y. Risk Factors Associated with 31-Day Unplanned Readmission in 50,912 Discharged Patients after Stroke in China. BMC Neurol. 2018;218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casolla B, Moulin S, Kyheng M, Henon H, Labreuche J, Leys D, Bauters C, Cordonnier C. Five-Year Risk of Major Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Events after Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2019;1100–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murthy SB, Diaz I, Wu X, Merkler AE, Iadecola C, Safford MM, Sheth KN, Navi BB, Kamel H. Risk of Arterial Ischemic Events after Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2020;137–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimberly WT, Gilson A, Rost NS, Rosand J, Viswanathan A, Smith EE, Greenberg SM. Silent Ischemic Infarcts Are Associated with Hemorrhage Burden in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Neurology. 2009;1230–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg RK, Liebling SM, Maas MB, Nemeth AJ, Russell EJ, Naidech AM. Blood Pressure Reduction, Decreased Diffusion on MRI, and Outcomes after Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;67–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon RS, Burgess RE, Wing JJ, Gibbons MC, Shara NM, Fernandez S, Jayam-Trouth A, German L, Sobotka I, Edwards D, et al. Predictors of Highly Prevalent Brain Ischemia in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2012;199–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prabhakaran S, Naidech AM. Ischemic Brain Injury after Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Critical Review. Stroke. 2012;2258–2263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulanger M, Schneckenburger R, Join-Lambert C, Werring DJ, Wilson D, Hodel J, Zuber M, Touze E. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Hyperintensities in Subtypes of Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2018:STROKEAHA118021407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidwell CS, Rosand J, Norato G, Dixon S, Worrall BB, James ML, Elkind MS, Flaherty ML, Osborne J, Vashkevich A, et al. Ischemic Lesions, Blood Pressure Dysregulation, and Poor Outcomes in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurology. 2017;782–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy SB CS, Gupta A, Shoamanesh A, Navi BB, Avadhani R, Gruber J, Li Y, Greige T, Lioutas V, Norton C, et al. A Pooled Analysis of Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Lesions in Patients With Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. JAMA Neurol, 2020;77(11):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qureshi AI, Palesch YY, Barsan WG, Hanley DF, Hsu CY, Martin RL, Moy CS, Silbergleit R, Steiner T, Suarez JI, et al. Intensive Blood-Pressure Lowering in Patients with Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1033–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein J, Brouwers H, Romero J, McNamara K, Schwab K, Greenberg S, Rosand J. Score-It: The Spot Sign Score in Restricting ICH Growth Horizontal Line an ATACH-II Ancillary Study. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2012;20–25 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanley DF, Thompson RE, Rosenblum M, Yenokyan G, Lane K, McBee N, Mayo SW, Bistran-Hall AJ, Gandhi D, Mould WA, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Minimally Invasive Surgery with Thrombolysis in Intracerebral Haemorrhage Evacuation (MISTIE III): A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Blinded Endpoint Phase 3 Trial. Lancet. 2019;1021–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;573–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MISTIE-III Study Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan. http://braininjuryoutcomes.com/images/MISTIE3/MISTIE_III_Protocol_SAP.pdf. Accessed on July 10, 2019.

- 17.Qureshi AI, Palesch YY. Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage (ATACH) II: Design, Methods, and Rationale. Neurocrit Care. 2011;559–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR Signal Abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's Dementia and Normal Aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;351–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morotti A, Shoamanesh A, Oliveira-Filho J, Schlunk F, Romero JM, Jessel M, Ayres A, Vashkevich A, Schwab K, Cassarly C, et al. White Matter Hyperintensities and Blood Pressure Lowering in Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Secondary Analysis of the ATACH-2 Trial. Neurocrit Care. 2020;180–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoamanesh A, Catanese L, Romero JR, Lau H, Babikian VL, Benavente OR, Kase CS, Pikula A. High Prevalence of Cerebral Microbleeds in Inner City Young Stroke Patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;733–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveira-Filho J, Ay H, Shoamanesh A, Park KY, Avery R, Sorgun M, Kim GM, Cougo PT, Greenberg SM, Gurol ME. Incidence and Etiology of Microinfarcts in Patients with Ischemic Stroke. J Neuroimaging. 2018;406–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson D, Ambler G, Lee KJ, Lim JS, Shiozawa M, Koga M, Li L, Lovelock C, Chabriat H, Hennerici M, et al. Cerebral Microbleeds and Stroke Risk after Ischaemic Stroke or Transient Ischaemic Attack: A Pooled Analysis of Individual Patient Data from Cohort Studies. Lancet Neurol. 2019;653–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buletko AB, Thacker T, Cho SM, Mathew J, Thompson NR, Organek N, Frontera JA, Uchino K. Cerebral Ischemia and Deterioration with Lower Blood Pressure Target in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurology. 2018;e1058–e1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang DW, Han MK, Kim HJ, Yun SC, Jeon SB, Bae HJ, Kwon SU, Kim JS. New Ischemic Lesions Coexisting with Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurology. 2012;848–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Shahi Salman R, Minks DP, Mitra D, Rodrigues MA, Bhatnagar P, du Plessis JC, Joshi Y, Dennis MS, Murray GD, Newby DE, et al. Effects of Antiplatelet Therapy on Stroke Risk by Brain Imaging Features of Intracerebral Haemorrhage and Cerebral Small Vessel Diseases: Subgroup Analyses of the Restart Randomised, Open-Label Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019;643–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maestrini I, Altieri M, Di Clemente L, Vicenzini E, Pantano P, Raz E, Silvestrini M, Provinciali L, Paolino I, Marini C, et al. Longitudinal Study on Low-Dose Aspirin Versus Placebo Administration in Silent Brain Infarcts: The SILENCE Study. Stroke Res Treat. 2018;7532403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;e344–e418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charidimou A, Imaizumi T, Moulin S, Biffi A, Samarasekera N, Yakushiji Y, Peeters A, Vandermeeren Y, Laloux P, Baron JC, et al. Brain Hemorrhage Recurrence, Small Vessel Disease Type, and Cerebral Microbleeds: A Meta-Analysis. Neurology. 2017;820–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified MISTIE III and ATACH-2 trial data are available at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke data archive. To gain access, requesters will need to submit a proposal and sign a data-access agreement.