Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- AFP

alpha‐fetoprotein

- APHE

arterial phase hyperenhancement

- CCA

cholangiocarcinoma

- CEUS

contrast‐enhanced ultrasound

- CT

computed tomography

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- LI‐RADS

Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System

- LR

Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NC

not categorizable

- TIV

tumor in vein

- US

ultrasound

Most hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) are hypervascular tumors and occur in cirrhotic liver. 1 These unique histological features of HCC lead to sensitive and specific imaging features and allow multiphasic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to be used as an initial diagnostic test. 2 , 3 The CT/MRI findings are interpreted using imaging diagnostic algorithms, namely, Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI‐RADS), for HCC diagnosis. 4 , 5 Liver biopsy could be considered for a definite diagnosis when the imaging results remain equivocal or patients do not have cirrhosis. 2 , 3 In this article, we discuss the diagnostic criteria of HCC and the role of LI‐RADS for imaging diagnosis of HCC.

Diagnosis of HCC

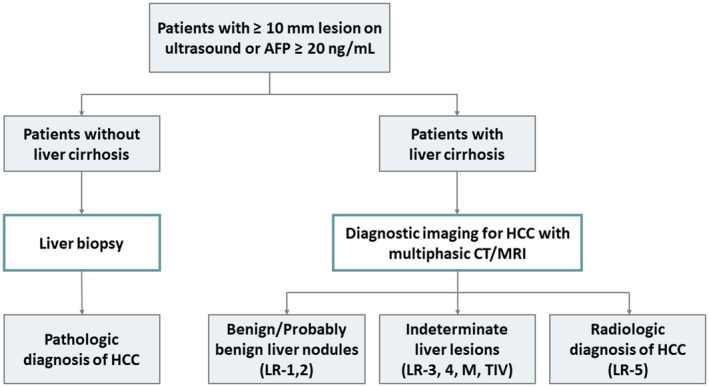

Unlike most solid cancers, the diagnosis of HCC can be established in patients with cirrhosis based on multiphasic CT or MRI without histological confirmation (Fig. 1). 2 , 3 The imaging hallmarks suggestive of HCC include nonrim arterial phase hyperenhancement (APHE), washout on portal venous and/or delayed phases, and capsule appearance in a lesion ≥1 cm. 4 , 5 Type of imaging modality (CT versus MRI), type of contrast for MRI (extracellular versus hepatobiliary contrast agents), presence of ascites, and size of the lesion may affect the performance of radiology test for the diagnosis of HCC. 6 CT is preferred over MRI in patients with large ascites or difficulty with holding breath because they introduce severe artifact on MRI. In contrast, for patients with renal disease, iodine allergy, or pregnancy, MRI would be a favorable diagnostic approach. In patients with hepatic decompensation (total bilirubin >2‐3 mg/dL), hepatobiliary contrast agents uptaken by the liver tend to be reduced, and CT or MRI using extracellular contrast agents (versus hepatobiliary contrast) may be preferable. In addition, the choice of imaging modality and type of contrast may be based on center expertise. Currently, a diagnostic liver biopsy is done selectively for patients whose HCC diagnosis remains indeterminate on contrast‐enhanced imaging or in patients without cirrhosis (Fig. 1). Liver biopsy is generally considered safe for HCC diagnosis because the risk of tumor seeding is low and does not influence the oncological course. 7 , 8

FIG 1.

Diagnostic algorithm of HCC. Once at‐risk patients have abnormal surveillance test results or clinical suspicion of HCC (liver lesions ≥1 cm or AFP ≥20 ng/mL), multiphasic CT or MRI is recommended as the initial diagnostic testing for patients with cirrhosis. The CT/MRI findings are interpreted using the LI‐RADS for HCC diagnosis. For patients without cirrhosis or for whom HCC diagnosis remains indeterminate on imaging, liver biopsy could be considered for a definite diagnosis.

LI‐RADS Criteria for HCC Diagnosis

LI‐RADS provides a comprehensive imaging algorithm for evaluation of abnormal liver lesions in patients with cirrhosis and is integrated into the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) 2018 HCC practice guidance. 4 , 5 Currently, LI‐RADS offers four individual imaging algorithms designed for different clinical contexts. CT/MRI LI‐RADS and contrast‐enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) LI‐RADS are the two algorithms used for imaging diagnosis of HCC.

LI‐RADS Criteria for CT and MRI

CT/MRI LI‐RADS for diagnosis of HCC can be applied only to multiphasic CT or MRI performed in patients with cirrhosis. 4 , 5 However, CT/MRI LI‐RADS should not be applied in patients with cirrhosis caused by congenital hepatic fibrosis or vascular disorders (e.g., hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, Budd‐Chiari syndrome) or in patients <18 years old because of potential false‐positive results and insufficient data. The major features suggestive of HCC include nonrim APHE, nonperipheral portal venous or delayed phase washout, enhancing capsule appearance, size of at least 1 cm, and threshold growth by ≥50% in ≤6 months. 4 , 5 Based on the presence/absence of the major features, as well as several additional ancillary features (e.g., restricted diffusion, corona enhancement, mosaic architecture, etc), the lesion can be divided into eight unique LI‐RADS categories that reflect the probability of HCC (Fig. 1).

Table 1 summarizes the categories of LI‐RADS and the recommended approaches. LI‐RADS (LR)‐NC (not categorizable) is applied when image omission or degradation precludes categorization. LR‐1 (definitely benign) and LR‐2 (probably benign) range from simple cysts to distinctive solid nodules, defined as small (<2 cm) nodules without any malignant features. Return to ultrasound (US)‐based surveillance at a routine 6‐month interval is recommended for LR‐1 observations. For LR‐2 observations, follow‐up CT or MRI in 6 months or less may be considered. LR‐3 (intermediate probability of HCC) includes some perfusion alterations that have a nodular shape with one or two malignant features. Because approximately 30% to 40% of LR‐3 observations are HCC, 9 such observations merit close monitoring with follow‐up CT or MRI in 3 to 6 months rather than returning to US‐based surveillance.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the Categories and the Recommended Approaches of LI‐RADS for CT and MRI

| Diagnostic Category | CT/MRI Criteria | Management Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| LR‐NC: Noncategorizable | Cannot be categorized because of image degradation or omission | Repeat or alternative diagnostic imaging in ≤3 months |

| LR‐1: Definitely benign | Simple cyst, solid nodule with characteristics features of hemangioma | Return to surveillance in 6 months |

| 0% HCC | ||

| 0% malignancy | ||

| LR‐2: Probably benign | <20 mm with no major features, LR‐M features, or ancillary features favoring malignancy | Return to surveillance in 6 months |

| 13% HCC | OR | |

| 14% malignancy | Consider repeat diagnostic imaging in ≤6 months | |

| LR‐3: Intermediate probability of HCC |

Nonrim APHE AND:

|

Repeat or alternative diagnostic imaging in 3‐6 months |

| 38% HCC |

No APHE AND:

|

|

| 40% malignancy | ||

| LR‐4: Probably HCC |

Nonrim APHE AND:

|

Multidisciplinary discussion for tailored workup

|

| 74% HCC |

No APHE AND:

|

|

| 80% malignancy | ||

| LR‐5: Definitely HCC |

Nonrim APHE AND:

|

HCC confirmed

|

| 94% HCC | ||

| 97% malignancy | ||

| LR‐M: Probably or definitely malignant, not specific for HCC |

Targetoid mass:

|

Multidisciplinary discussion for tailored workup

|

| 36% HCC |

Nontargetoid mass not meeting LR‐5 criteria AND no TIV, with ≥1 of the following:

|

|

| 93% malignancy | ||

| LR‐TIV: Malignancy with TIV | Unequivocal enhancing soft tissue in vein, regardless of visualization of parenchymal mass |

Multidisciplinary discussion for tailored workup

|

| 79% HCC | ||

| 92% malignancy |

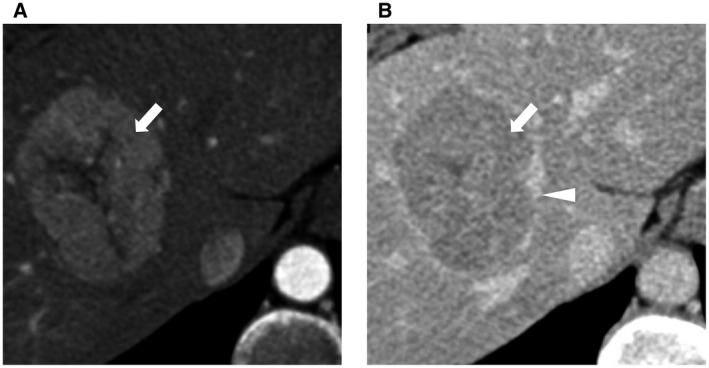

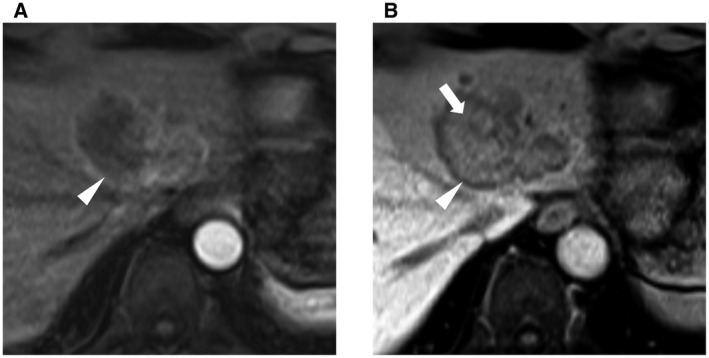

The LI‐RADS categories suggestive of malignancy include LR‐4 (probably HCC), LR‐5 (definitely HCC), LR‐M (probably or definitely malignant, not specific for HCC), and LR‐TIV (malignancy with tumor in vein). LR‐4 observations are defined as the presence of major features of HCC, but these features do not meet the stringent criteria of LR‐5 for HCC diagnosis. Multidisciplinary discussion for tailored workup is recommended for LR‐4 observations. Reasonable options include biopsy or repeated imaging in a short interval of around 3 months. A lesion is categorized as LR‐5 if it is ≥20 mm in size with APHE and has one or more of the other major features. For lesions between 10 and 19 mm, APHE plus either nonperipheral washout or threshold growth will qualify them as LR‐5 observations. An LR‐5 observation has 94% positive predictive value of being HCC (Fig. 2), 9 and biopsy is not needed in these cases to confirm the diagnosis. LR‐M observations are almost certainly malignant but may be another type of cancer that is not HCC, including intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), combined HCC‐CCA, and large or necrotic HCC with atypical imaging features (Fig. 3). As for LR‐TIV observations, although HCC is the most common hepatic tumor associated with macrovascular invasion, the differential diagnosis includes CCA and rarely other malignancies. Therefore, the AASLD guideline recommends selective biopsy strategies or repeated imaging for patients with LR‐M and LR‐TIV observations to establish the diagnosis. 2

FIG 2.

Features of a CT/MRI LR‐5 mass. Characteristic imaging features of HCC. (A) Nonrim APHE. (B) Nonperipheral portal venous or delayed phase washout (white arrow) and enhancing capsule appearance (white triangle).

FIG 3.

Features of a CT/MRI LR‐M targetoid mass. Biopsy‐proven intrahepatic CCA. (A) Rim APHE. (B) Peripheral washout (white triangle) and delayed central enhancement (white arrow).

LI‐RADS criteria for CEUS

CEUS involves the use of a microbubble contrast agent to improve the echogenicity of blood flow. The CEUS LI‐RADS algorithm also has the same eight LI‐RADS categories and is similar in concept to the CT/MRI LI‐RADS algorithm, despite some modifications according to its microbubble contrast agent. 4 , 5 For example, the characterization of washout on CEUS is different from CT/MRI, and threshold growth and enhancing capsule appearance are not major features for CEUS. Some studies show that CEUS is as accurate as CT/MRI for liver lesion characterization, and CEUS is considered when the initial modality for HCC diagnosis (CT/MRI) shows indeterminate findings (LR‐3 or LR‐4). 3 However, CEUS is not currently recommended in AASLD guidelines for HCC diagnosis because of insufficient data in the United States. 2

Conclusion

Imaging plays a critical role in HCC diagnosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. LI‐RADS can characterize abnormal liver lesions and allow radiological diagnosis of HCC in patients with cirrhosis. For patients without cirrhosis, liver biopsy is still required for diagnosis. It remains unclear whether patients with cirrhosis and LR‐3 or LR‐4 lesions are best served by biopsy or repeated or alternative imaging, and this is a critical area for future research. Recently, several attempts were made using cutting‐edge novel liquid biopsies to improve detection and diagnosis of HCC. 10 We envision that these novel approaches may complement current diagnostic algorithms for noninvasive diagnosis of HCC soon.

Potential conflict of interest: J.D.Y. consults for Exact Sciences. H.‐R.T. owns stock in CytoLumina Technologies Corp.

References

- 1. Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, et al. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:589‐604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;68:723‐750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines . Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182‐236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chernyak V, Fowler KJ, Kamaya A, et al. Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System (LI‐RADS) Version 2018: Imaging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in At‐Risk Patients. Radiology 2018;289:816‐830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang A, Singal AG, Mitchell DG, et al. Introduction to the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:1228‐1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roberts LR, Sirlin CB, Zaiem F, et al. Imaging for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Hepatology 2018;67:401‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuks D, Cauchy F, Fusco G, et al. Preoperative tumour biopsy does not affect the oncologic course of patients with transplantable HCC. J Hepatol 2014;61:589‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silva MA, Hegab B, Hyde C, et al. Needle track seeding following biopsy of liver lesions in the diagnosis of hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Gut 2008;57:1592‐1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Pol CB, Lim CS, Sirlin CB, et al. Accuracy of the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System in computed tomography and magnetic resonance image analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma or overall malignancy—a systematic review. Gastroenterology 2019;156:976‐986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahn JC, Teng P‐C, Chen P‐J, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells and their implications as a novel biomarker for diagnosis, prognostication, and therapeutic monitoring in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2020. Available at: 10.1002/hep.31165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]