Abstract

Companion animals are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection and sporadic cases of pet infections have occurred in the United Kingdom. Here we present the first large-scale serological survey of SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies in dogs and cats in the UK. Results are reported for 688 sera (454 canine, 234 feline) collected by a large veterinary diagnostic laboratory for routine haematology during three time periods; pre-COVID-19 (January 2020), during the first wave of UK human infections (April–May 2020) and during the second wave of UK human infections (September 2020–February 2021). Both pre-COVID-19 sera and those from the first wave tested negative. However, in sera collected during the second wave, 1.4% (n = 4) of dogs and 2.2% (n = 2) of cats tested positive for neutralising antibodies. The low numbers of animals testing positive suggests pet animals are unlikely to be a major reservoir for human infection in the UK. However, continued surveillance of in-contact susceptible animals should be performed as part of ongoing population health surveillance initiatives.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Serology, Dogs, Cats, Animal disease surveillance

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019 (Wu et al., 2020) and rapidly spread around the world. The main route of transmission remains human-to-human. However, there is evidence that the virus can infect animals (Prince et al., 2021) and it is important that we remain vigilant of such infections; particularly in companion animals with whom humans often have close contact.

Although initially there were only sporadic cases of infection in cats and dogs (Garigliany et al., 2020; Newman et al., 2020; Sit et al., 2020), there are now numerous reports of infection detected by RT-PCR or virus isolation (Barrs et al., 2020; Decaro et al., 2021; Hamer et al., 2021; Ruiz-Arrondo et al., 2021; Sailleau et al., 2020), including in the UK (Hosie et al., 2021). Evidence of infection of cats and dogs has also been provided by the detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in several studies worldwide (Fritz et al., 2021; Michelitsch et al., 2020, 2021; Patterson et al., 2020a; Stevanovic et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Experimental infections have shown that cats and, to a lesser extent, dogs are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 and that cats can transmit the virus to other cats (Bosco-Lauth et al., 2020; Halfmann et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Infections in companion animals appear to have occurred as a result of human-to-animal transmission; however, the reported transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from farmed mink to in-contact humans, cats and dogs (Oude Munnink et al., 2021; van Aart et al., 2021) and the detection of the virus in stray dogs and cats (Dias et al., 2021; Villanueva-Saz et al., 2021), suggest it is important to continue surveillance in companion animals. Here we conducted a survey of SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies in cats and dogs attending UK veterinary practices.

2. Methods

2.1. Samples

Canine and feline sera used in this study were obtained from the UK Virtual Biobank, which uses health data from commercial diagnostic laboratories participating in the Small Animal Veterinary Surveillance Network (SAVSNET) to target left over diagnostic samples in the same laboratories for enhanced phenotypic and genomic analyses (Smith et al., 2021). All samples were residual sera remaining after routine diagnostic testing and were sent by one contributing laboratory based on convenience within the following parameters: samples were requested from UK cats and dogs collected over two time periods; March and April 2020 (during the first wave in humans) for both cats and dogs, then September 2020 to February 2021 for dogs, and January 2021 for cats (during the second wave in humans). Serum samples collected from the same laboratory in early January 2020 were also tested as pre-COVID-19 controls. All samples were linked to electronic health data for that sample (species, breed, sex, postcode of the submitting veterinary practice, date received by the diagnostic laboratory) held in the SAVSNET database, using a unique anonymised identifier. Data on SARS-CoV-2 exposure or symptoms was not available. Ethical approval to collect electronic health data (SAVSNET) and physical samples from participating laboratories (National Virtual Biobank) was granted by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Liverpool (RETH000964).

2.2. Neutralising antibody detection in serum samples

Serum samples were screened for SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies using the plaque reduction neutralisation test (PRNT) as previously described (Patterson et al., 2020a), with the SARS-CoV-2/human/Liverpool/REMRQ0001/2020 isolate cultured in Vero E6 cells (Patterson et al., 2020b). Briefly, sera were heat inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min and stored at −20 °C until use. DMEM containing 2% FBS was used to dilute sera ten-fold followed by serial two-fold dilution. SARS-CoV-2 at 800 plaque forming units (PFU)/ml was added to diluted sera and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The virus/serum mixture was then inoculated onto Vero E6 cells, incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and overlaid as in standard plaque assays (Rossi et al., 2015). Cells were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, fixed with 10% formalin and stained with 0.05% crystal violet solution. PRNT80 was determined by the highest dilution with 80% reduction in plaques compared to the control. Samples with detectable neutralising antibody titre were repeated as technical replicates for confirmation. Where titres differed between technical replicates, the lowest dilution was reported.

3. Results

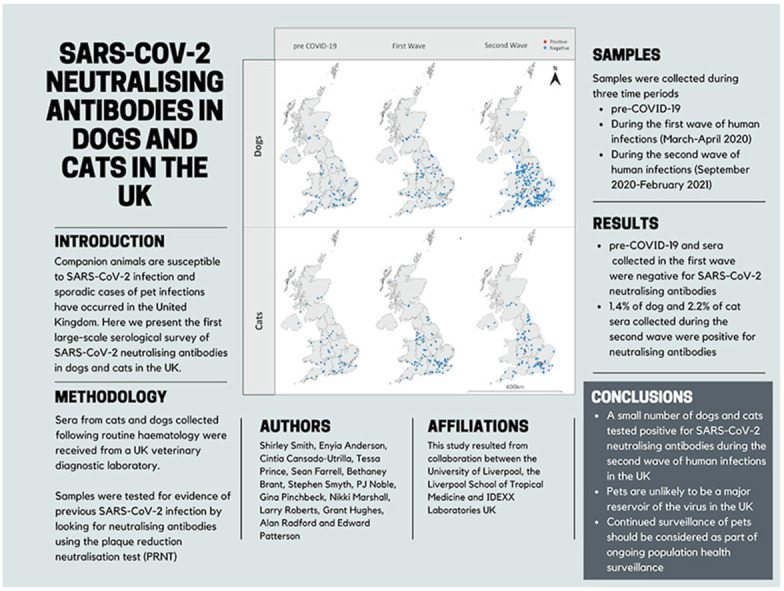

A total of 732 samples were received from the diagnostic laboratory and tested for SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies. Linking of data to the samples found that 22 samples were duplicates (duplicate samples gave the same result in each replicate and are therefore reported as one sample). Seven samples were from animals with non-UK postcodes, two samples did not have species data, two samples were received as dogs but were actually from cats and were collected outside the two time periods of cat sample collection and eleven samples were missing postcodes; these samples were excluded. Results are therefore reported for 688 sera (454 canine, 234 feline) of which 558 (372 dogs, 186 cats) were collected during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and 130 (82 dogs, 48 cats) were collected from animals before the first confirmed human case in the UK (21st January 2020 (Lillie et al., 2020)) - pre-COVID-19 samples; these samples were distributed across the UK (Fig. 1 ). Of the dog sera collected during the pandemic, 0/85 (0%) collected in March/April 2020 and 4/287 (1.4%) collected September 2020–February 2021 tested positive for neutralising antibodies with titres of 1:20 (n = 2) and 1:80 (n = 2). In cats, 0/96 (0%) sera collected in March/April 2020 tested positive for neutralising antibodies and 2/90 (2.2%) collected in January 2021 tested positive with titres of 1:40 and 1:80. Pre-COVID-19 sera from both dogs (n = 82) and cats (n = 48) tested negative for neutralising antibodies. Positive samples in dogs were collected in November 2020 (n = 1), January 2021 (n = 2) and February 2021 (n = 1) and were collected in Kent, Buckinghamshire, Worcestershire and Yorkshire, respectively (Fig. 1). The two positive cats were collected in January 2021; one in Birmingham and the other in London (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic map showing the location of samples for which testing of SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies is reported. Red dots indicate samples that were positive for SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies using PRNT80. Blue dots indicate samples that were negative. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

Studies of companion animals have shown that they can be infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Prince et al., 2021). In the UK, there have been sporadic reports of infection in cats and dogs, including one that tested 387 cats showing respiratory signs using RT-PCR and found one cat to be positive for the virus (Hosie et al., 2021; Ferasin et al., 2021). However, there has been no large scale sero-survey of infection. Here we show that a small proportion of UK dogs and cats, sampled at a time of active human transmission, tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies.

Sera from two time points during the pandemic were analysed. Sera collected during March and April 2020 (first wave) from both cats and dogs were negative for neutralising antibodies. Previous studies using European samples have shown a low level of infection, highest in Italy, where 3.3% (15/451) of dog sera and 5.8% (11/191) cat sera collected between March and May 2020 had measurable neutralising antibody titres (Patterson et al., 2020a). These samples were purposefully collected from regions of Italy with a high prevalence of infection in humans, in some cases from households known to contain recently diagnosed human cases. Our results in contrast, are more consistent with a survey from a similar population of cats in Germany, that found 0/221 samples collected in April and May of 2020 to be positive for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies using ELISA (Michelitsch et al., 2020), and with a survey in the Netherlands in April–May 2020, that found 0.4% of cats and 0.2% of dogs to be seropositive (Zhao et al., 2021a). The lack of positive samples from March–April 2020 in the UK, that we report here, likely reflects the selection criteria of the animals assayed (undergoing routine haematological testing and not selected based on location), and the relatively low rate of human disease at the time compared to Italy.

In sera collected during the second wave of the pandemic, 4/287 (1.4%) dogs and 2/90 (2.2%) cats tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies. Positive dog samples were collected in November 2020 and January and February of 2021. Positive cat samples were collected in January 2021. This is again broadly in line with a recent German survey conducted from September 2020 to February 2021, showing a seroprevalence of 1.36% (increased from 0.69% earlier in the pandemic), that the authors concluded corresponded with the rise of reported cases in the human population, and was suggestive of ongoing transmission from owners to their cats (Michelitsch et al., 2021). The detection of neutralising antibodies in dogs and cats during the second wave in this study also likely reflects the increased numbers of humans that had been infected. However, it is unknown whether the main variant circulating in the UK human population during the second wave (B.1.1.7) has altered transmissibility to cats and dogs as it does in humans (Davies et al., 2021). Whilst there is some work in model species testing new variants in e.g. hamsters (Nunez et al., 2021; Oa Donnell et al., 2021), to our knowledge none of the early experimental infections performed in cats and dogs using the original SARS-CoV-2 have been repeated with newer variants.

Cats and dogs can be infected with other coronaviruses, leading to the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies detected in this study may result from previous infection with a different virus. We and others have previously demonstrated a lack of cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and samples containing antibodies to feline coronavirus (FCoV), canine enteric coronavirus (CeCoV) and canine respiratory coronavirus (CRCoV) (Michelitsch et al., 2020; Patterson et al., 2020a; Stevanovic et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). The reverse has also been demonstrated whereby cat or dog samples containing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 did not react with known feline or canine coronavirus antigens (Michelitsch et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021b). Here we also tested samples from UK cats and dogs collected before the human index case in the UK (21st January 2020 (Lillie et al., 2020)). All pre-COVID-19 samples were negative for SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies. Although there are no recent sero-surveys of cat and dog coronaviruses in the UK (Addie and Jarrett, 1992; Priestnall et al., 2006; Stavisky et al., 2010), FCoV, CeCoV and CRCoV are considered to be endemic. Furthermore, a recent serological survey in the Netherlands testing for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies also found 71% of cat and 40% of dog pandemic sera to have antibodies to other known cat or dog coronaviruses (Zhao et al., 2021a). If cross-reactivity of SARS-CoV-2 with antibodies to cat and dog coronaviruses was occurring in the study reported here, this would be apparent in the pre-COVID-19 samples. We would also expect to see higher numbers of animals with SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies in the pandemic samples, again suggesting that antibodies produced following infection by endemic cat and dog coronaviruses do not cross-react with SARS-CoV-2.

Here we made use of samples collected from a commercial diagnostic laboratory contributing data to a voluntary national surveillance scheme (SAVSNET) to efficiently test for evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK cats and dogs. The major limitations of such a system are the relatively sparse data available for each sample such that individual animals, that are not identifiable, may have been sampled twice or have come from the same household. In addition, such samples lack detailed information on the health of the animals and whether they were from a COVID-19-positive household. However, acquiring such samples from the UK Virtual Biobank, offers a responsive resource for studying national patterns of disease in UK pets (Smith et al., 2021).

We report here the detection of a low level of SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies in dogs and cats during the second wave of human infections in the UK. The use of a neutralisation assay will not detect animals that have sero-converted but not produced neutralising antibodies (such that might test positive by ELISA but not by PRNT). Indeed, other studies have shown that sera positive by ELISA for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies may not have detectable neutralising antibodies (Michelitsch et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021b). As such, our results may underestimate the number of animals exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

We and others report that cats and dogs can become infected with SARS-CoV-2, likely through their interactions with humans. Although animal-to-animal transmission has been reported, for example on mink farms and in experimental infections (Bosco-Lauth et al., 2020; Halfmann et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020; van Aart et al., 2021; Oreshkova et al., 2020), the small numbers of companion animals testing positive in the field in the UK and elsewhere suggest that pets are not currently acting as a significant reservoir for infection, and that the pandemic will be controlled by measures largely focussed on minimising human-to-human transmission. Current UK guidance is that COVID-19 positive humans should limit contact with their pets. Studies like that presented here strongly argue for continued surveillance of in-contact, susceptible animal species, particularly with the emergence of new variants, which will help determine whether in the future, more targeted control measures are needed for pet animals, particularly in regions that are gaining control of infection in their human populations.

Funding

SLS, ADR, PJN and GLP were supported by funding from Dogs Trust. GLH was supported by the BBSRC (BB/T001240/1 and BB/V011278/1), a Royal Society Wolfson Fellowship (RSWF∖R1∖180013), the NIH (R21AI138074), the UKRI (20197 and 85336), and the NIHR (NIHR2000907). GLH and TP are affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at University of Liverpool in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the University of Oxford. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health or Public Health England. EIP and GLH were supported by the EPSRC (V043811/1) and UKRI-BBSRC COVID rolling fund (BB/V017772/1). CCU was supported by the Medical Research Council (N013514/1). Funding sources had no involvement in the design or conduct of the study or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:NM and LR are employed by IDEXX Laboratories. All other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Addie D.D., Jarrett J.O. Feline coronavirus antibodies in cats. Vet. Rec. 1992;131:202–203. doi: 10.1136/vr.131.9.202-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrs V.R., Peiris M., Tam K.W.S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 in quarantined domestic cats from COVID-19 households or close contacts, Hong Kong, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:3071–3074. doi: 10.3201/eid2612.202786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco-Lauth A.M., Hartwig A.E., Porter S.M., et al. Experimental infection of domestic dogs and cats with SARS-CoV-2: pathogenesis, transmission, and response to reexposure in cats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:26382–26388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2013102117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N.G., Abbott S., Barnard R.C., et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science. 2021:372. doi: 10.1126/science.abg305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaro N., Vaccari G., Lorusso A., et al. Possible human-to-dog transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Italy, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27:1981–1984. doi: 10.3201/eid2707.204959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias H.G., Resck M.E.B., Caldas G.C., et al. Neutralizing antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 in stray animals from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PloS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferasin L., Fritz M., Ferasin H., et al. Myocarditis in naturally infected pets with the British variant of COVID-19. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.18.435945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz M., Rosolen B., Krafft E., et al. High prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in pets from COVID-19+ households. One Health. 2021;11:100192. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garigliany M., Van Laere A.S., Clercx C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 natural transmission from human to cat, Belgium, March 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:3069–3071. doi: 10.3201/eid2612.202223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann P.J., Hatta M., Chiba S., et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in domestic cats. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:592–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer S.A., Pauvolid-Correa A., Zecca I.B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infections and viral isolations among serially tested cats and dogs in households with infected owners in Texas, USA. Viruses. 2021;13:938. doi: 10.3390/v13050938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie M.J., Epifano I., Herder V., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples from cats in the UK associated with human-to-cat transmission. Vet. Rec. 2021;188:e247. doi: 10.1002/vetr.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie P.J., Samson A., Li A., et al. Novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19): the first two patients in the UK with person to person transmission. J. Infect. 2020;80:578–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelitsch A., Hoffmann D., Wernike K., et al. Occurrence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in the domestic cat population of Germany. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8:772. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelitsch A., Schon J., Hoffmann D., et al. The second wave of SARS-CoV-2 circulation-antibody detection in the domestic cat population in Germany. Viruses. 2021;13:1009. doi: 10.3390/v13061009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman A., Smith D., Ghai R.R., et al. First reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in companion animals - New York, march-april 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69:710–713. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez I.A., Lien C.Z., Selvaraj P., et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 infection of Syrian hamster does not cause more severe disease, and naturally acquired immunity confers protection. mSphere. 2021 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00507-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oa Donnell K.L., Pinski A.N., Clancy C.S., et al. Pathogenic and transcriptomic differences of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants in the Syrian golden hamster model. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.07.11.451964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oreshkova N., Molenaar R.J., Vreman S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, The Netherlands, April and May 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.23.2001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oude Munnink B.B., Sikkema R.S., Nieuwenhuijse D.F., et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on mink farms between humans and mink and back to humans. Science. 2021;371:172–177. doi: 10.1126/science.abe5901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson E.I., Elia G., Grassi A., et al. Evidence of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in cats and dogs from households in Italy. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:6231. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson E.I., Prince T., Anderson E.R., et al. Methods of inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 for downstream biological assays. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;222:1462–1467. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestnall S.L., Brownlie J., Dubovi E.J., et al. Serological prevalence of canine respiratory coronavirus. Vet. Microbiol. 2006;115:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince T., Smith S.L., Radford A.D., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infections in animals: reservoirs for reverse zoonosis and models for study. Viruses. 2021;13:494. doi: 10.3390/v13030494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S.L., Russell-Lodrigue K.E., Killeen S.Z., et al. IRES-containing VEEV vaccine protects cynomolgus macaques from IE Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus aerosol challenge. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2015;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Arrondo I., Portillo A., Palomar A.M., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in pets living with COVID-19 owners diagnosed during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain: a case of an asymptomatic cat with SARS-CoV-2 in Europe. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021;68:973–976. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sailleau C., Dumarest M., Vanhomwegen J., et al. First detection and genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 in an infected cat in France. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020;67:2324–2328. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Wen Z., Zhong G., et al. Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS-coronavirus 2. Science. 2020;368:1016–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit T.H.C., Brackman C.J., Ip S.M., et al. Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;586:776–778. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2334-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.L., Afonso M.M., Roberts L., et al. A virtual biobank for companion animals: a parvovirus pilot study. Vet. Rec. 2021 doi: 10.1002/vetr.556. e556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavisky J., Pinchbeck G.L., German A.J., et al. Prevalence of canine enteric coronavirus in a cross-sectional survey of dogs presenting at veterinary practices. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;140:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevanovic V., Vilibic-Cavlek T., Tabain I., et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among pet animals in Croatia and potential public health impact. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021;68:1767–1773. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Aart A.E., Velkers F.C., Fischer E.A.J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in cats and dogs in infected mink farms. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1111/tbed.14173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Saz S., Giner J., Tobajas A.P., et al. Serological evidence of SARS-CoV-2 and co-infections in stray cats in Spain. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1111/tbed.14062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Zhang H., Gao J., et al. A serological survey of SARS-CoV-2 in cat in Wuhan. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2020;9:2013–2019. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1817796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Schuurman N., Li W., et al. Serologic screening of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in cats and dogs during first coronavirus disease wave, The Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27:1362–1370. doi: 10.3201/eid2705.204055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Yang Y., Gao J., et al. A serological survey of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in dogs in Wuhan. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1111/tbed.14024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]