Abstract

Chronic back and neck pain are highly prevalent conditions that are among the largest drivers of physical disability and cost in the world. Recent clinical practice guidelines recommend use of non-pharmacologic treatments to decrease pain and improve physical function for individuals with back and neck pain. However, delivery of these treatments remains a challenge because common care delivery models for back and neck pain incentivize treatments that are not in the best interests of patients, the overall health system, or society. This narrative review focuses on the need to increase use of non-pharmacologic treatment as part of routine care for back and neck pain. First, we present the evidence base and summarize recommendations from clinical practice guidelines regarding non-pharmacologic treatments. Second, we characterize current use patterns for non-pharmacologic treatments and identify potential barriers to their delivery. Addressing these barriers will require coordinated efforts from multiple stakeholders to prioritize evidence-based non-pharmacologic treatment approaches over low value care for back and neck pain. These stakeholders include patients, health care providers, health care organizations, administrators, payers, policymakers and researchers.

Introduction

Chronic back and neck pain are highly prevalent conditions that are among the largest drivers of physical disability and cost in the world.1 In fact, back and neck pain accounted for $134.5 billion of U.S. health care spending in 2016,2 This was the highest health care spending for any of the 154 medical conditions included in the study, led by private insurance (57.2%), then public insurance (33.2%), and out of pocket payments (9.2%).2 The majority of physical disability and cost is associated with chronic back and neck pain conditions, which are the focus of this review.

Traditionally, most care for back and neck pain begins with a patient visiting a primary care provider (PCP).3 For decades, usual medical care for spine pain (whether an acute or chronic condition) has focused on standard treatments and technologies prescribed by primary care providers or procedures that require referral. Recently the effectiveness of this medically driven approach has been questioned in the literature.4 Further, increasing evidence indicates that prescription medicine such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids, radiological/advanced imaging techniques, and invasive therapies such as spinal fusion and epidural injections have risks that can outweigh benefits to individual patients.4

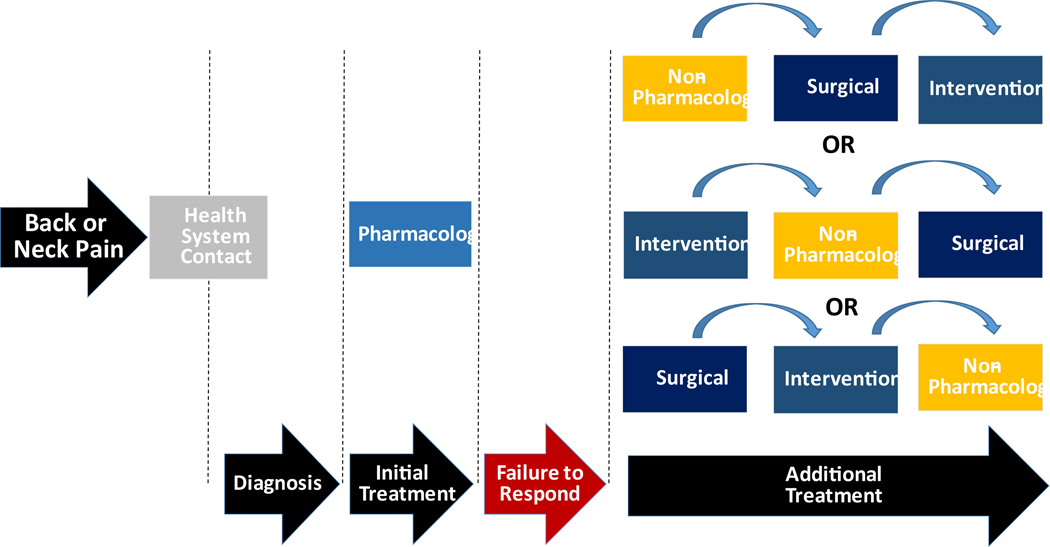

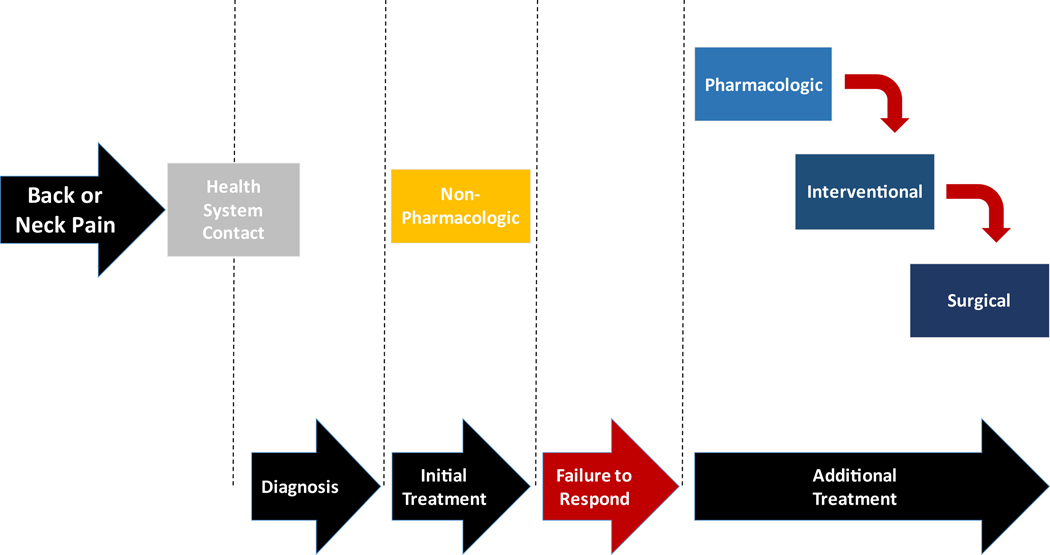

Other available data suggests that non-pharmacologic treatments are underutilized for back and neck pain. For example, the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey indicated 21.5 % of new visits for chronic MSK included opioid prescriptions while only 10.0% included a prescription for physical therapy.5 This is consistent with earlier research showing that a prescription for opioids was received by 20% of patients visiting a medical doctor for acute or chronic pain.6 Conversely, evidence from observational studies demonstrates that early exposure to specific non-pharmacologic providers has the benefit of decreasing risk of future opioid use for back and neck pain.7–11 Unfortunately, most healthcare systems are not structured to deliver non-pharmacologic treatments early in care episodes. That is, many existing health care systems have been designed to consider pharmacologic treatments to be primary interventions, while considering conservative treatments as secondary interventions that are made available only to those who fail primary treatments. As a result, there is notable variability in the sequencing of non-pharmacologic, interventional, or surgical treatments (Figure 1A). A delivery system in better alignment with current clinical practice guidelines would structure delivery of non-pharmacologic treatment as a primary offering (Figure 1B). After non-pharmacologic treatments are trialed, secondary treatments such as pharmacologic, interventional, and surgical treatments would be considered in a stepped, progressive manner for those still experiencing symptoms (Figure 1B). Structuring care in this manner has been successfully piloted, demonstrating that first contact with a non-pharmacologic provider (i.e. physical therapist, chiropractor, or acupuncturist) can result in less opioid use when compared to first contact with a primary care physician provider.7 Since the vast majority of care tends to be conservative (i.e. up to 98% of those receiving treatment12), redesigned care pathways that emphasize increased exposure to non-pharmacologic pain treatments have high potential to positively impact individual and population health by providing viable alternatives to opioids as a first choice in pain management.

Figure 1.

A. Generic Care Pathway for Musculoskeletal Pain Conditions (Current State)

A. Generic Care Pathway for Musculoskeletal Conditions (Future State)

Such a change in care delivery seems to be a relatively simple one to execute, but there is ample evidence suggesting otherwise. Current management practices are characterized by approaches that emphasize pharmacologic, interventional, or surgical treatments over non-pharmacologic treatments.13 Therefore, this narrative review focuses on the continued need to systematically increase use of non-pharmacologic treatment as part of routine care for back and neck pain. First, we present the evidence base by summarizing recommendations from clinical practice guidelines regarding non-pharmacologic treatments. Second, we characterize current use patterns for non-pharmacologic treatments and identify potential barriers to their delivery. It is beyond the scope of this review to consider all barriers, so we focused on those that if adequately addressed would most likely improve delivery of non-pharmacologic treatments for individuals with back and neck pain.

Evidence Base for Non-Pharmacologic Treatments

Non-pharmacologic treatments have been the topic of several high quality evidence syntheses over the past 5 years. Selected examples include a systematic review supporting the aforementioned American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guidelines for Low Back Pain14 and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Comparative Effectiveness Reviews for Low Back Pain15 and Chronic and Back and Neck Pain.16 Collectively the existing evidence supports shifts in care that de-medicalize these conditions,4,17 consider principles of value based care,18 and de-incentivize pharmacological, interventional, and surgical approaches that carry high risk profiles with no commensurate improvement in experiencing better outcomes.19

Clinical practice guidelines

The existing literature investigating the effectiveness of non-pharmacologic treatments is quite robust for neck and back pain, allowing many organizations to develop guidelines accordingly. Examples representing commonly-cited guidelines endorsed by national governing bodies and physicians groups include the American College of Physicians20, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidelines for low back pain and sciatica21, the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative for treatment of neck pain-associated disorders22, and the Bone and Joint Decade Task Force on neck pain and its associated disorders.23 Table 1 provides a general summary recommendations from these guidelines, as well as treatment effects and strength of evidence ratings reported in recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses for different low back pain and neck pain treatments. A notable finding from these reviews is that, with few exceptions, treatment effects for pain related (i.e. pain intensity, pain interference) and functional outcomes are largely equivocal across different non-pharmacological treatment options and when compared to other pharmacologic, interventional, and surgical treatments. However, in some cases the risk of harm is greater for pharmacologic, interventional, and surgical treatments. Therefore, clinical practice guidelines advocating for non-pharmacologic treatments are primarily driven by reducing the risk of harm, not necessarily by larger treatment effects for pain related outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of Example Clinical Practice Guidelines and Systematic Review Findings for Select Non-Pharmacologic and Pharmacologic Treatments for Low Back Pain and Neck Pain

| Recommendation† | Clinical Practice Guidelines | Effects and Strength of Evidence†† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Back | Neck | Low Back | Neck | |||

| ACP | NICE | CCGI | BJDTF | |||

| Education and self-care | ||||||

| Advice to remain active | Combined | Primary | Secondary | Secondary | Small*74 | Small*22 |

| Education | Combined | Primary | Secondary | Secondary | Small*74 | Small*75 |

| Superficial heat | Primary (a) | NR | Secondary | NR | Moderate74 | None22 |

| Non-pharmacologic therapy | ||||||

| Therapeutic exercise | Primary (c) | Primary | Primary | Primary | Small*74 | Small74 |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | Primary (c) | Combined | NR | Secondary | Small*74 | None76 |

| Spinal manipulation | Primary | Combined | Secondary | Primary | Small74 | Small*77 |

| Myofascial therapies | Primary (a) | Combined | Secondary | NR | Small74 | Small74 |

| Acupuncture | Primary | NR | Secondary | Primary | Small74 | Small74 |

| Yoga | Primary (c) | Primary | Secondary | -- | Small-moderate*74 | Small78 |

| Mindfulness-based strategies | Primary (c) | NR | -- | -- | None74 | Small74 |

| Multidisciplinary rehabilitation | Primary (c) | Secondary | -- | -- | Small74 | None79 |

| Pharmacologic therapy | ||||||

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Primary (a) Secondary (c) | Primary | -- | NR | Small*24 | None*80 |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants | Primary (a) | NR | -- | Secondary (a) | Small*24 | -- |

| Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | NR | NR | -- | -- | None*24 | -- |

| Opioids | Secondary (c)** | Secondary (a)** | -- | -- | Small*24 | None23 |

ACP = American College of Physicians24; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence21; CCGI = Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative22; BJDTF = Bone and Joint Decade Task Force23;

Recommendations specific to acute pain (a) or chronic pain (c);

Effect sizes are small (standard mean difference (SMD) of 0.2 to 0.5), moderate (SMD of >0.5 to 0.8) or none over placebo or usual care, all with low quality evidence (additional evidence is needed before concluding either that the findings are stable or that the estimate of effect is close to the true effect)74 unless denoted

,which indicates moderate quality evidence (findings are likely to be stable, but some doubt remains).74 Clinical guideline endorsed as first line care (Primary), second line care (Secondary), as part of combined treatment with active treatments (Combined), not recommended (NR), or not referenced or too little evidence exists to make recommendations (--).

Limited use in select patients or use with caution, refer to guideline for more information.

Collectively the assembled guidelines recommend the following non-pharmacologic options: advice and education (back pain), therapeutic exercise (back and neck pain), psychological or cognitive-behavioral therapies (back pain), spinal manipulation (back and neck pain), massage (neck pain), acupuncture (back pain), yoga (back pain), and mindfulness-based strategies (back pain). When benefits for non-pharmacologic treatments have been identified in these evidence syntheses, the benefit is typically observed in short-term follow up of pain and functional outcomes (i.e. 3 months or earlier).

The guidelines included in Table I also provide recommendations for when to consider pharmacologic treatments for back and neck pain. For example, use of pharmacological therapies beyond NSAIDs is recommended only in specific circumstances. In patients for whom conservative treatments failed, opioids are recommended only if the potential benefits outweigh the risks for individual patients and after a discussion of known risks and benefits.

Current guideline recommendations vary somewhat in ways that can affect clinical decision making for neck and back pain. For example, the American College of Physician guideline recommends non-pharmacological approaches before any prescription medications24 while others focus on first providing safer pharmaceutical alternatives to opioids.25 However, collectively they show strong convergence towards the use of non-pharmacologic treatments for individuals with back and neck pain.

Characterizing Delivery of Non-Pharmacologic Treatments

Use patterns

Many different provider types deliver non-pharmacologic treatments. Since 2002, trends in the use of a number of non-pharmacologic therapies in the United States have been measured on an approximate quinquennial basis as part of the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey, in partnership with the National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Therapies surveyed include chiropractic, yoga, massage therapy, progressive relaxation, guided imagery and acupuncture. Use of guided imagery and acupuncture have remained approximately the same from 2002–2012 (ranging from 1–2% of US adults), while use of massage therapy fluctuated between 5–8% and use of yoga increased from 5 to nearly 10%.26 More recent data looked at trends from 2012 to 2017 in those non-pharmacologic approaches most commonly utilized, including yoga, meditation and chiropractic.27 Use of all three therapies increased over the five year period, with the largest increase in meditation (4.1% to 14.2%), followed by yoga (9.5% to 14.3%) and chiropractic (9.1% to 10.3%) as some of the most utilized.27 These findings are consistent with utilization of physical therapy, with use rates ranging from 7–14% for patients with musculoskeletal conditions such as low back and neck pain.28–30 We recognize that other therapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness can also be used in the treatment of back and neck pain. However, utilization data on these therapies is not readily available.

The trend data above is consistent with other studies demonstrating that despite a strong convergence in practice guidelines recommendations, the use of non-pharmacologic treatments has not greatly increased in the past 10 years.13 For example, during a period of increasing opioid prescription rates across the United States, the rate of physical therapy prescriptions remained stable at about 10%.29 Further, a recently published study shows patients report that medical physicians are more likely to prescribe opioids (27%) rather than refer to providers of chiropractic (18.4%) or acupuncture (5.3%) services.31 The lack of increased uptake for non-pharmacologic treatments despite a strong supporting evidence base suggests that a shift needs to be made in how care is structured, so that it is easier to deliver these treatments to patients with back and neck pain.

Barriers to delivery of non-pharmacologic treatments

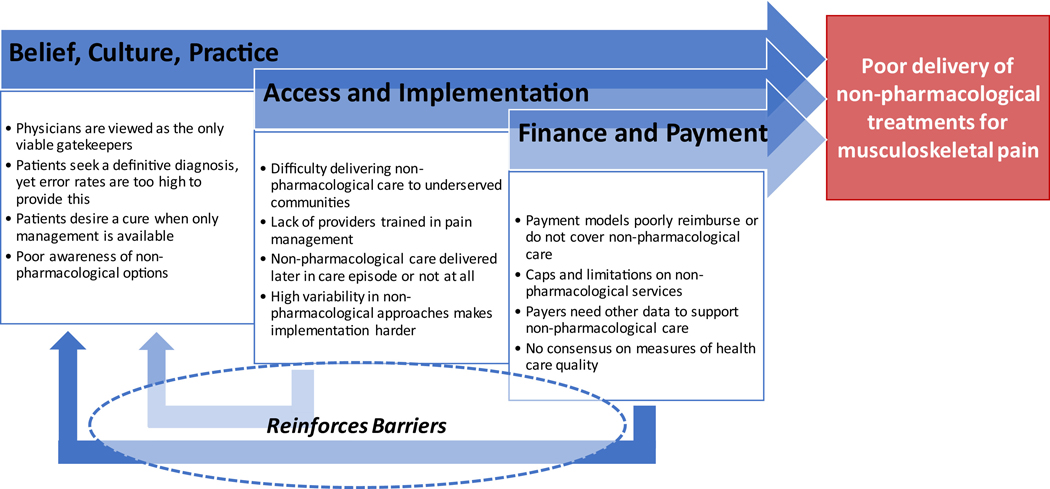

Slow uptake of evidence and poor adherence to clinical guidelines is not unique to back and neck pain, but rather reflects a common problem in health care. For example, a recent study found that among patients at risk for heart disease and not already taking a statin, only 59.2% were offered a statin by their physician, despite clinical practice guidelines encouraging use of the drug.32 Among patients undergoing treatments for different types of cancers, adherence to established practice guidelines varied based on cancer type (range 54–99%) and treatment modality (adherence ranged from 40 to 92%).33 Poor adherence to or slow uptake of clinical practice guidelines for back and neck pain may have the seemingly banal consequences of receiving unhelpful or potentially unwarranted care. However, we have come to better understand that unhelpful or unwarranted care for back and neck pain can lead to serious consequences like opioid use disorder (OUD), interventional and surgical procedures that carry adverse event risks, persistent disability, and avoidable high costs.13 Increased awareness of these consequences has created urgency among health systems to identify and address barriers to delivery of guideline-adherent non-pharmacological treatments.19 Consistent with the nature of back and neck pain, barriers to delivery of non-pharmacologic care are complex. In this review we describe barriers in three categories: 1) belief, culture, and practice; 2) access and implementation; and 3) financial and payment (Figure 2). Although we present these categories as distinct, many of the barriers discussed are interconnected and could fit multiple categories. Moreover, as well-designed studies assessing barriers to care are limited, we present these challenges as they are described in the existing literature, and provide insights based on our perspectives regarding current health care policy and delivery.

Figure 2.

Barriers that Impeded Delivery of Non-Pharmacologic Care for Musculoskeletal Conditions

Belief, culture, and practice barriers

A fundamental barrier to non-pharmacologic care is that seeking consultation and reassurance from a physician when in pain is embedded in our medical care culture and learned behaviors. However, recent evidence from observational studies suggests that for back and neck pain, seeking the care of a physician first could result in higher costs and increased risk of unwarranted care escalation when compared to first seeking care from a non-physician provider (e.g., physical therapist, chiropractor).34–36 These same studies show similar patient outcomes between care delivered by physicians and non-physicians. As a result, some payers and many states have eliminated administrative and regulatory barriers to direct access to non-pharmacologic services, like physical therapy, for back and neck pain. While these steps represent an advancement toward better integration of non-pharmacologic care, deeply rooted health care seeking behaviors and medical culture have limited progress toward models that encourage non-physician providers in frontline care roles.

Primary care providers and patients are often resistant to change in practice patterns for low back and neck pain. Primary care providers cite barriers to practice change that includes short consultation times preventing exploration of non-pharmacologic options, the need for diagnostic imaging prior to treatment trials, and guideline recommendations that are seen as constraints against providing care unique to their patient.37,38 Patients are a second source of resistance to changing established practice patterns. 39,40 The patient’s desire for a definitive diagnosis prior to receiving back and neck pain treatment contributes to high rates of early imaging. Current guidelines do not recommend routine imaging studies for back or neck pain, yet they are highly valued by patients. Further, patients value prognosis and treatment recommendations personalized to their unique circumstances, rather than reliance on more generic clinical guidelines. Patients’ expectations that physicians are the gatekeepers to effective pain relief are also difficult to change. Many individuals with musculoskeletal pain value a definitive diagnosis, with the belief that knowing the underlying pathology will necessarily result in treatment that provides effective pain relief.39,40 However, there is now convincing evidence that pathology and pain-related disability are not well-correlated, and in many cases a definitive diagnosis is not possible for individuals with spine pain.4 At the very least a definitive diagnosis is often not needed to begin a trial of non-pharmacologic care to determine if a favorable response will occur. However, it remains an uphill battle in changing peoples’ perceptions that seeing a physician first for a definitive diagnosis may not be the most cost-effective approach for back and neck pain.

Providing guideline adherent care often requires a collaborative relationship between patient and provider and current health care encounters are not structured to allow for such collaboration. Some health care providers view the evolution of pain care toward more collaborative, value-based models as a threat to autonomy or the hierarchical structure of medical care. Conversely, others see it as an opportunity to gain help in managing a patient population with complex needs that may benefit from the integration of care from multiple medical disciplines. However, even among those who are aware of and support the use of non-pharmacological options, changing long-standing views and behaviors systematically for all provider types is challenging.

Finally, patients and providers have the perception that experiencing pain precludes good health and well-being. To meet this expectation, consumers are provided with many treatment options like opioids and surgery that promise quick, effort-free, and absolute pain relief.41 Unfortunately, many of the available treatments option do not deliver on this promise.14,42 The public may view treatments like medication and surgery as the only viable options for pain management, and have poor awareness of the potential benefits of non-pharmacological treatments. Public education campaigns can potentially be effective in driving uptake of non-pharmacological treatments if they are modeled after those that were used to successfully improve general expectations of back pain management. 43 A classic example is a public advertisement campaign in Australia that used radio and printed advertisements, outdoor billboards, posters, seminars, workplace visits, and publicity articles to successfully modify beliefs and health care utilization related to low back pain.43 However, depending on the country these media campaigns were implemented - not all had similar positive effects and existing public campaign models would have to be modified to specifically advocate for use of non-pharmacologic treatments.

Access and implementation barriers

Overall, access to and insurance coverage of non-pharmacologic care is highly variable.44 In an analysis of Medicare beneficiaries accessing care for persistent musculoskeletal pain between 2007 and 2014, use of some non-pharmacologic providers was low: only 13.9 % used physical therapy and 1.8% used mental health services.30 Chiropractic care was utilized by approximately 35% of Medicare beneficiaries with a spine condition.45 The rates of chiropractic were relatively higher than the physical therapy and mental health services, but still not high enough to be considered guideline adherent. Compounding the access issue, health care delivery is poorly designed to address back and neck pain in the most vulnerable populations, exacerbating existing inequalities within health care. For instance, many areas hardest hit by the opioid crisis are rural and underserved communities, the same communities that are unlikely to have access to many guideline-supported non-pharmacological treatments.46 Specifically, these communities may have too few primary care providers, pain management specialists and trained behavioral health professionals, which creates both challenges for health care access and limits integration of services. In rural areas or areas with severely limited provider options, many patients cannot afford the time and cost of traveling to treatment. Indeed data in the aforementioned analysis of Medicare beneficiaries indicated that different strategies may be used to enhance access depending on whether in a rural or metropolitan area.30

Telehealth can reduce disparities in access to high quality pain care. One benefit of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is that telehealth services and capabilities for back and neck pain have expanded tremendously.47 Proof of concept for this type of care delivery in back and neck pain comes from behavioral interventions for knee osteoarthritis emphasizing pain coping skills. These interventions have been successfully delivered through telehealth and their effectiveness has been demonstrated in controlled trials.48,49 However, the favorable payment and regulatory environments that have allowed these services to flourish during a pandemic face an uncertain post-pandemic future, creating questions around whether telehealth will remain a common or preferred pain management strategy.

Finance and payment barriers

Predominant health care payment models in the US actively, although perhaps unintentionally, discourage the use of evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments.44 A recent meeting of payers, health care systems, and policymakers concluded that fee-for-service payment models fundamentally misalign reimbursement with high value care for musculoskeletal pain, creating one of the most significant barriers to implementation of guideline-adherent, non-pharmacological pain care.50 For example, fee-for-service models poorly support care coordination and conversations with patients about their goals and needs, a critical component of effective chronic pain care. Additionally, many payers poorly reimburse or altogether do not cover many non-pharmacologic therapies (e.g., yoga, acupuncture, cognitive behavioral therapies), despite evidence of their effectiveness.44 This creates little incentive for health care systems to invest in offering or scaling these treatments, especially when doing so would increase costs for the payer in the short term.51 Fee-for-service arrangements also create perverse incentives for overuse, which can contribute to wasteful spending in cases where high levels of health care use are not advised by clinical practice guidelines (e.g., acute pain management with a favorable prognosis).52–54 Utilization management can reduce the risk of overuse, but creates additional access and payment restrictions that can adversely affect patients such as pre-authorization requirements, limits on direct access to non-physician providers, and arbitrary benefit caps on services commonly used for pain management, notably physical therapy and chiropractic care.44 In contrast to non-pharmacologic care, pharmacologic management has far fewer access and payment barriers despite evidence of marginal effectiveness and recommendations against its use as front line care. These fewer barriers are due, in part, to the relatively low costs of pain medications compared to non-pharmacological treatments.51 However, this approach does not consider the extremely high societal cost of opioids, which has been estimated at $50 Billion annually in the US.55

Value-based payment models for back and neck pain, which provide payment for quality outcomes rather than volume of services, would encourage use of the most effective treatments and minimize perverse incentives that drive high volume, potentially wasteful care.18 Although value-based payment models have become commonplace for some conditions and populations, they are not widely established for the management of back and neck pain. The U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs (VA) Whole Health Program is one notable example.56 While the Whole Health program is not specific to pain management, it does emphasize self-care within the broader context of well-being, and incorporates a full range of conventional and non-pharmacologic health approaches, such as stress reduction, yoga, tai chi, mindfulness, nutrition, acupuncture, and health coaching. Not coincidentally, many of these services are well aligned with practice guideline recommendations for back and neck pain. Unlike many employer-based health plans, the VA is responsible for lifelong care of the Veteran which provides significant incentives and resources to deliver high value non-pharmacological treatments that optimize long-term health and well-being.

Future Directions

Daniel Cherkin, PhD noted during the Role of Nonpharmacological Approaches to Pain Management Workshop convened in 2018 by the National Academies that there is an opportunity to move from “a thousand points of blight to a thousand points of light”.13 Given the evidence accumulated and convergence in current practice guidelines, individuals with back and neck pain present an unprecedented opportunity for health care transformation.17 As progress is made to address barriers to the delivery of non-pharmacologic treatments, there are several emergent issues worth highlighting that will influence the future of non-pharmacologic care.

Belief, practice, and culture

It is hoped that accumulating more data will continue to shape provider and payer beliefs about non-pharmacologic care. In the meantime, existing data potentially has a role to play in facilitating wider, more consistent insurance coverage of non-pharmacologic treatments. A recent investigation of United States commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare Advantage health plans noted high variability in coverage policies for non-pharmacologic treatments.44 For example, in treatments with strong evidence support; physical therapy and chiropractic care were covered in 85%+ of included health plans while acupuncture and psychologic interventions were, respectively, not widely covered or coverage information was not available. The variability in coverage observed in this study was not linked to evidence supporting the non-pharmacological treatment and instead attributed to factors like absence of best practice models, difficulty of updating policies to include new options, and existing economic incentives.44 This example shows that while compelling data are necessary to shape payer beliefs, they alone are not sufficient to change coverage or health care practices about non-pharmacologic treatments.

In addition, direct comparisons of non-pharmacologic to pharmacologic, interventional, and surgical treatments are needed to foster change in entrenched clinical practices that emphasize pharmacologic, interventional, and surgical treatments. The evidence on such comparisons is very small currently but likely to grow. Recently published randomized trials using usual medical care comparators support this assertion. One trial reported that patients undergoing physical therapy had a small improvement in function and pain compared to usual medical care for sciatica,58 while another trial indicated adding chiropractic care to usual medical care for back pain improved 6-week function and pain ratings.59 Since usual medical care often includes non-pharmacologic options these trials cannot be interpreted as direct comparisons to pharmacologic, intervention, or surgical approaches. Direct comparisons are rarer, but a prior randomized trial did compare surgical decompression to physical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis and reported similar 24-month outcomes for self-reported function.60 Another randomized trial compared open discectomy to individualized non-operative care for confirmed lumbar disk herniation and signs of radiculopathy, and also reported similar 24-month outcomes for self-reported bodily pain and function.61 However, both of these trials noted high cross-over rates for the randomized treatment arms highlighting the difficulty of generating direct comparisons of non-pharmacologic and medical treatments even in a highly controlled trial.60,61 To date, this emerging literature is favorable to non-pharmacologic treatments as being at least equally effective in comparison to usual medical care. Similar findings from highly controlled trials would help to positively shift provider beliefs about non-pharmacologic treatment and provide better indications of their use by medical practitioners.

Finally, another way to positively impact beliefs, practice, and culture is to change the model for provider training towards a multi-disciplinary approach to patient care given that no one discipline has the full range of skills necessary to autonomously manage the broad spectrum of back and neck pain. To be successful, such models will require first contact care by a clinician who is well-trained to evaluate, triage and manage care for a large majority of pain patients. It has been proposed that we fill this role with the “primary spine practitioner”, licensed health care providers such as doctors of chiropractic, doctoral level physical therapists, or medical doctors with specific expertise in the guideline-concordant diagnosis and management of spine-related disorders.62 Such models will not solve all back and neck pain management problems, but if properly situated in a health system, they could limit unnecessary variability in early care encounters and ensure that escalation to interventional and surgical treatments is done in a measured fashion.63

Access and implementation

Wider implementation of successful models is a first step towards enhancing exposure to non-pharmacologic treatments. For example, promising observational data shows that early delivery of non-pharmacologic treatments can reduce long term opioid exposure.7–11 However, several caveats limit translation of these data into practice. For instance, long term opioid use is not a problem in all countries and is not always indicative of a poor outcome. Further, the importance of timing and/or dosing of non-pharmacologic treatments and their impact on health related quality of life outcomes is unknown.64 Protocols describing randomized clinical trials that will address these issues include; sequencing of different non-pharmacological treatments65, comparisons of high and low dosage of spinal manipulation66, sequencing of spinal manipulation and exercise67, and comparative effectiveness of different care pathways emphasizing non-pharmacologic care.68 In the next 5 years these trials will provide data to inform future implementation of non-pharmacologic treatments. Finally, none of these early delivery models have been evaluated in low resource areas or rural areas so their value is unknown in areas where overall increased access to care is needed. There are compelling models to follow for implementation of care in low resource areas. For example, a randomized trial reported that literacy adapted cognitive behavioral therapy or patient education resulted in better pain and function outcomes than usual care for individuals with chronic pain that were at or below the poverty line and with low reading levels.69

Implementation frameworks are also helpful, since the unique aspects of individual health systems may make adoption of any one specific pain management model difficult. Instead of being prescriptive, frameworks offer guidance on how care should be delivered and allow for flexibility in adoption. One framework that has been proposed for transforming back pain care recommends choosing one of three levels of care - foundational, individualized, and specialized.63 Each of these care levels offers specific components and opportunities for personalization. For instance, foundational care includes patient education to reduce threat of back pain and would be widely applied as a core component of all care episodes. Individualized care could then be layered on top of foundational care by delivering services tailored to specific patient needs (e.g. psychologically informed treatment for those with high pain-associated distress70,71). Specialized care would represent the highest intensity of care for back and neck pain by including a wider range of medical specialties including interventional and surgical consultation. This framework is specifically designed to provide flexibility in how health systems can deliver this level of care based on a given environment. Another important aspect of this proposed framework is that care pathways are structured around guideline recommendations so that care escalation is coordinated and supported by evidence (e.g. specialized care is only delivered to individuals most indicated for interventional and surgical care).63 Another example of a recently proposed implementation framework combines elements of stepped (i.e. comprehensive interventions only offered to those with inadequate response to simple care) and stratified care models (i.e. level of care determined by risk of prolonged disability).72 The purpose of this particular framework is also to provide initial care options that are personalized to individual needs (in contrast to traditional stepped care models where all individuals receive the same initial care), while escalating care to interventional treatments only when it is likely to result in more effective care for the management of back pain.72 This new hybrid model has not yet undergone widespread implementation and testing but the proposed framework has the potential provide personalized care that is guideline adherent, includes robust exposure to non-pharmacologic treatments, and minimizes the risk of unwarranted escalation of care.

A final issue to consider is the number of non-pharmacologic treatments available for implementation. As depicted in Table 1, multiple non-pharmacologic treatments have sufficient evidence to be recommended for use in back or neck pain. Unfortunately, there are no data indicating which of these might be the “best choice” for universally recommended implementation. This issue presents a challenge to health systems, because it creates uncertainty in determining which particular treatments are to be offered for delivery. Conversely, it also presents an opportunity for health systems to invest in a few key services based on patient choice, provider availability, or local regulatory environment. Those working towards implementation of non-pharmacologic treatments need to balance what is a reasonable amount of treatments to offer with the amount that can actually be delivered at scale to meet the demands of “front-line” pain management.

Finance and payment

Despite compelling data supporting the benefits and potential cost-savings of non-pharmacologic care, health care payers and purchasers report additional data is needed to support benefit designs that appropriately prioritize non-pharmacological care. Outstanding questions include information on who would benefit or not benefit from specific treatments, how many patients would seek non-pharmacological care if more widely available, how comorbidities influence treatment effectiveness, and which treatments are most effective.50 While we argue that the current state of the evidence is sufficient to support greater uptake of non-pharmacologic treatment approaches, we agree that these data are needed to advance value-based payment models that emphasize quality of care over volume of care. Such models provide an opportunity to better compensate providers for key components of pain care that are currently ignored in fee-for-service models, such as care navigation, coordination of services, and many integrative approaches like acupuncture, nutritional interventions and behavioral health services.56

Before widespread adoption of the models we note above is possible, health care systems and payers must work collaboratively to ensure their financial viability, develop frameworks to measure and report outcomes, and build will among providers and administrators.73 Success of these models is also predicated on the ability to appropriately measure and track quality of care, which would require consensus on how to measure quality of care for back or neck pain. Multi-stakeholder efforts to define quality and establish thresholds for what is considered high quality care will be critical for moving these payment models from concept to practice.

Limitations of this Review

We have not included a systematic or exhaustive review of all clinical practice guidelines, so this paper may not represent the full gamut of recommendations that have been made for these treatments. Further, Table 1 provides a general overview of clinical guideline recommendations for illustrative and comparative purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for a thorough review of these guidelines when making clinical decisions.

Conclusion

The current system of care delivery for back and neck pain promotes and incentivizes treatments that may frequently not be in the best interests of patients, the overall health system, or society.17,19 In this review we outline current guideline-concordant recommendations for these pervasive conditions and identify barriers that, if overcome, would allow for changes to occur that improve implementation of non-pharmacologic care. Like back and neck pain conditions, these barriers are complex, and include issues related to beliefs, culture, access, and payment. Similarly complex solutions will be required and in all likelihood an “all hands on deck” approach of collaboration will be needed to overcome these barriers. That is, contributions from patients, health care providers, health care organizations, administrators, payers, policymakers and researchers will be needed to steer routine care delivery away from low value care for back and neck pain and towards evidence-based non-pharmacologic treatment approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors (SZG, TAL, and CMG) have read the journal’s policy on conflicts of interest and have no competing interests or conflicts of interest to report.

The authors (SZG, TAL, and CMG) have read the journal’s authorship agreement and agree to its terms. Each of the authors have contributed to this paper intellectually, included a final review and approval of the submitted manuscript. The authors acknowledge Robert Edwards for his helpful suggestions from a review of an earlier version of this manuscript. This paper has not been submitted anywhere else for publication.

The authors acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health while preparing this manuscript (SZG and TAL: UH3AT00970 and CMG: UH3AT009761).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Steven Z. George, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham NC (USA), 200 Morris Street, Durham NC 27701.

Trevor A. Lentz, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham NC (USA), 200 Morris Street, Durham NC 27701.

Christine M. Goertz, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Durham NC (USA), 200 Morris Street, Durham NC 27701.

References

- 1.Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet (London, England). 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, et al. US Health Care Spending by Payer and Health Condition, 1996–2016. Jama. 2020;323(9):863–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart LG, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC. Physician office visits for low back pain. Frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a U.S. national survey. Spine. 1995;20(1):11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet (London, England). 2018;391(10137):2368–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman DE, Carlesso LC, Nahin RL. Management of Patients with a Musculoskeletal Pain Condition that is Likely Chronic: Results from a National Cross Sectional Survey. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daubresse M, Chang HY, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000–2010. Med Care. 2013;51(10):870–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazis LE, Ameli O, Rothendler J, et al. Observational retrospective study of the association of initial healthcare provider for new-onset low back pain with early and long-term opioid use. BMJ open. 2019;9(9):e028633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun E, Moshfegh J, Rishel CA, Cook CE, Goode AP, George SZ. Association of Early Physical Therapy With Long-term Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients With Musculoskeletal Pain. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e185909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karmali RN, Skinner AC, Trogdon JG, Weinberger M, George SZ, Hassmiller Lich K. The Association Between the Supply of Nonpharmacologic Providers, Use of Nonpharmacologic Pain Treatments and High-risk Opioid Prescription Patterns Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Persistent Musculoskeletal Pain. Medical care. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horn ME, George SZ, Fritz JM. Influence of Initial Provider on Health Care Utilization in Patients Seeking Care for Neck Pain. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes. 2017;1(3):226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Childs JD, Fritz JM, Wu SS, et al. Implications of early and guideline adherent physical therapy for low back pain on utilization and costs. BMC health services research. 2015;15:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim LH, Vail D, Azad TD, et al. Expenditures and Health Care Utilization Among Adults With Newly Diagnosed Low Back and Lower Extremity Pain. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. The Role of Nonpharmacological Approaches to Pain Management: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Annals of internal medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. In: Noninvasive Treatments for Low Back Pain. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. In: Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchbinder R, van Tulder M, Oberg B, et al. Low back pain: a call for action. Lancet (London, England). 2018;391(10137):2384–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lentz TA, Harman JS, Marlow NM, George SZ. Application of a Value Model for the Prevention and Management of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain by Physical Therapists. Physical therapy. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traeger AC, Buchbinder R, Elshaug AG, Croft PR, Maher CG. Care for low back pain: can health systems deliver? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2019;97(6):423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.In: Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management. London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, et al. The Treatment of Neck Pain-Associated Disorders and Whiplash-Associated Disorders: A Clinical Practice Guideline. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(8):523–564 e527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, et al. The Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: executive summary. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trends in the use of complementary health approaches in the United States: 2002–2012. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/research/trends-in-the-use-of-complementary-health-in-the-unitedstates-20022012. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- 27.Clarke TCB PM; Black LI; Stussman BA; Nahin RL. Use of Yoga, Meditation, and Chiropractors Among US Adults Aged 18 and Over. 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter SK, Rizzo JA. Use of outpatient physical therapy services by people with musculoskeletal conditions. Physical therapy. 2007;87(5):497–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng P, Kao MC, Karayannis NV, Smuck M. Stagnant Physical Therapy Referral Rates Alongside Rising Opioid Prescription Rates in Patients With Low Back Pain in the United States 1997–2010. Spine. 2017;42(9):670–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karmali RN, Skinner AC, Trogdon JG, Weinberger M, George SZ, Hassmiller Lich K. The association between the supply of select nonpharmacologic providers for pain and use of nonpharmacologic pain management services and initial opioid prescribing patterns for Medicare beneficiaries with persistent musculoskeletal pain. Health services research. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goertz CM, Long CR, English C, Meeker WC, Marchiori DM. Patient-Reported Physician Treatment Recommendations and Compliance Among U.S. Adults with Low Back Pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2021. March;27(S1):S99–S105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradley CK, Wang TY, Li S, et al. Patient-Reported Reasons for Declining or Discontinuing Statin Therapy: Insights From the PALM Registry. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8(7):e011765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heins MJ, de Jong JD, Spronk I, Ho VKY, Brink M, Korevaar JC. Adherence to cancer treatment guidelines: influence of general and cancer-specific guideline characteristics. European Journal of Public Health. 2016;27(4):616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denninger TR, Cook CE, Chapman CG, McHenry T, Thigpen CA. The Influence of Patient Choice of First Provider on Costs and Outcomes: Analysis From a Physical Therapy Patient Registry. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2018;48(2):63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pendergast J, Kliethermes SA, Freburger JK, Duffy PA. A comparison of health care use for physician-referred and self-referred episodes of outpatient physical therapy. Health services research. 2012;47(2):633–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frogner BK, Harwood K, Andrilla CHA, Schwartz M, Pines JM. Physical Therapy as the First Point of Care to Treat Low Back Pain: An Instrumental Variables Approach to Estimate Impact on Opioid Prescription, Health Care Utilization, and Costs. Health services research. 2018;53(6):4629–4646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slade SC, Kent P, Patel S, Bucknall T, Buchbinder R. Barriers to Primary Care Clinician Adherence to Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Metasynthesis of Qualitative Studies. The Clinical journal of pain. 2016;32(9):800–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bishop FL, Dima AL, Ngui J, et al. “Lovely Pie in the Sky Plans”: A Qualitative Study of Clinicians’ Perspectives on Guidelines for Managing Low Back Pain in Primary Care in England. Spine. 2015;40(23):1842–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim YZ, Chou L, Au RT, et al. People with low back pain want clear, consistent and personalised information on prognosis, treatment options and self-management strategies: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy. 2019;65(3):124–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou L, Ranger TA, Peiris W, et al. Patients’ perceived needs for medical services for non-specific low back pain: A systematic scoping review. PloS one. 2018;13(11):e0204885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee TH. Zero Pain Is Not the Goal. Jama. 2016;315(15):1575–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Systemic Pharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Annals of internal medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suman A, Armijo-Olivo S, Deshpande S, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of mass media campaigns for the management of low back pain. Disability and rehabilitation. 2020:1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heyward J, Jones CM, Compton WM, et al. Coverage of Nonpharmacologic Treatments for Low Back Pain Among US Public and Private Insurers. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weigel PA, Hockenberry JM, Wolinsky FD. Chiropractic use in the Medicare population: prevalence, patterns, and associations with 1-year changes in health and satisfaction with care. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2014;37(8):542–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Institute of Medicine Committee on Advancing Pain Research C, Education. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eccleston C, Blyth FM, Dear BF, et al. Managing patients with chronic pain during the COVID-19 outbreak: considerations for the rapid introduction of remotely supported (eHealth) pain management services. Pain. 2020;161(5):889–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennell KL, Ahamed Y, Jull G, et al. Physical Therapist-Delivered Pain Coping Skills Training and Exercise for Knee Osteoarthritis: Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis care & research. 2016;68(5):590–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bennell KL, Nelligan R, Dobson F, et al. Effectiveness of an Internet-Delivered Exercise and Pain-Coping Skills Training Intervention for Persons With Chronic Knee Pain: A Randomized Trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lentz T, Goertz C, Sharma I, Gonzalez-Smith J, Saunders R. Managing Multiple Irons in the Fire: Continuing to Address the Opioid Crisis and Improve Pain Management during a Public Health Emergency. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2020: 10.1056/CAT.1020.0208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goertz CM, George SZ. Insurer Coverage of Nonpharmacological Treatments for Low Back Pain-Time for a Change. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michaleff ZA, Zadro JR, Traeger AC, O’Keeffe M, Décary S. Overcoming Overuse Part 2: Defining and Quantifying Health Care Overuse for Musculoskeletal Conditions. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2020;50(11):588–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Keeffe M, Traeger AC, Michaleff ZA, Décary S, Garcia AN, Zadro JR. Overcoming Overuse Part 3: Mapping the Drivers of Overuse in Musculoskeletal Health Care. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2020;50(12):657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zadro JR, Décary S, O’Keeffe M, Michaleff ZA, Traeger AC. Overcoming Overuse: Improving Musculoskeletal Health Care. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2020;50(3):113–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oderda GM, Lake J, Rüdell K, Roland CL, Masters ET. Economic Burden of Prescription Opioid Misuse and Abuse: A Systematic Review. Journal of pain & palliative care pharmacotherapy. 2015;29(4):388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole Health in the Whole System of the Veterans Administration: How Will We Know We Have Reached This Future State? Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, NY). 2019;25(S1):S7–s11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gewandter JS, McDermott MP, Mbowe O, et al. Navigating trials of personalized pain treatments: we’re going to need a bigger boat. Pain. 2019;160(6):1235–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fritz JM, Lane E, McFadden M, et al. Physical Therapy Referral From Primary Care for Acute Back Pain With Sciatica : A Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goertz CM, Long CR, Vining RD, Pohlman KA, Walter J, Coulter I. Effect of Usual Medical Care Plus Chiropractic Care vs Usual Medical Care Alone on Pain and Disability Among US Service Members With Low Back Pain: A Comparative Effectiveness Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(1):e180105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delitto A, Piva SR, Moore CG, et al. Surgery versus nonsurgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2015;162(7):465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. Jama. 2006;296(20):2441–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goertz CM, Weeks WB, Justice B, Haldeman S. A proposal to improve health-care value in spine care delivery: the primary spine practitioner. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2017;17(10):1570–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.George SZ, Goertz C, Hastings SN, Fritz JM. Transforming low back pain care delivery in the United States. Pain. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.George SZ, Goode AP. Physical therapy and opioid use for musculoskeletal pain management: competitors or companions? Pain reports. 2020;5(5):e827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skolasky RL, Wegener ST, Aaron RV, et al. The OPTIMIZE study: protocol of a pragmatic sequential multiple assessment randomized trial of nonpharmacologic treatment for chronic, nonspecific low back pain. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2020;21(1):293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Long CR, Lisi AJ, Vining RD, et al. Veteran Response to Dosage in Chiropractic Therapy (VERDICT): Study Protocol of a Pragmatic Randomized Trial for Chronic Low Back Pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass). 2020;21(Suppl 2):S37–s44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fritz JM, Sharpe J, Greene T, et al. Optimization of Spinal Manipulative Therapy Protocols: A Factorial Randomized Trial Within a Multiphase Optimization Framework. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.George SZ, Coffman CJ, Allen KD, et al. Improving Veteran Access to Integrated Management of Back Pain (AIM-Back): Protocol for an Embedded Pragmatic Cluster-Randomized Trial. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass). 2020;21(Suppl 2):S62–s72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thorn BE, Eyer JC, Van Dyke BP, et al. Literacy-Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Versus Education for Chronic Pain at Low-Income Clinics: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2018;168(7):471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Keefe FJ, Main CJ, George SZ. Advancing Psychologically Informed Practice for Patients With Persistent Musculoskeletal Pain: Promise, Pitfalls, and Solutions. Physical therapy. 2018;98(5):398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Main CJ, George SZ. Psychologically informed practice for management of low back pain: future directions in practice and research. Physical therapy. 2011;91(5):820–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kongsted A, Kent P, Quicke JG, Skou ST, Hill JC. Risk-stratified and stepped models of care for back pain and osteoarthritis: are we heading towards a common model? Pain reports. 2020;5(5):e843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jayakumar PODJM-H O.;Japinga M.;Mather C.; McClellan MB; Bozic K. Critical Considerations For Condition-Based Alternative Payment Models: A Multi-stakeholder Perspective. In. Health Affairs Blog 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. In: Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review Update. Rockville (MD)2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu H, Cote P, Southerst D, et al. Does structured patient education improve the recovery and clinical outcomes of patients with neck pain? A systematic review from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Spine J. 2016;16(12):1524–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shearer HM, Carroll LJ, Wong JJ, et al. Are psychological interventions effective for the management of neck pain and whiplash-associated disorders? A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Spine J. 2016;16(12):1566–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wong JJ, Shearer HM, Mior S, et al. Are manual therapies, passive physical modalities, or acupuncture effective for the management of patients with whiplash-associated disorders or neck pain and associated disorders? An update of the Bone and Joint Decade Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders by the OPTIMa collaboration. Spine J. 2016;16(12):1598–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li Y, Li S, Jiang J, Yuan S. Effects of yoga on patients with chronic nonspecific neck pain: A PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(8):e14649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, van Tulder M, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for neck and shoulder pain among working age adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Day RO, Pinheiro MB, Ferreira ML. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(7):1269–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]