Abstract

Background

To implement clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), it is necessary for psychiatrists to deepen their understanding of the CPGs. The Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment (EGUIDE) project is a nationwide dissemination and implementation study of two sets of CPGs for schizophrenia and major depressive disorder (MDD).

Methods

A total of 413 psychiatrists (n = 212 in 2016; n = 201 in 2017) learned the two CPGs in the education program of the EGUIDE project, and clinical knowledge of these CPGs was evaluated at baseline and after the programs. To improve the correct answer rate for clinical knowledge after the programs, we revised the lecture materials associated with items that had a low correct answer rate in 2016 and used the revised lecture materials with the CPGs in 2017. The rates of correct answers after the programs between the 2016 and 2017 groups were compared.

Results

The correct answer rate of one item on the schizophrenia CPG and one item on the MDD CPG tended to be improved (S‐D5 and D‐C6) and that of one on the MDD CPG was significantly improved (D‐D3, P = 0.0008) in the 2017 group compared to those in the 2016 group.

Conclusions

We reported improvements in clinical knowledge of CPGs after the EGUIDE program in the 2017 group following revision of the lecture materials based on results from the 2016 group. These attempts to improve the degree of understanding of CPGs may facilitate the successful dissemination and implementation of psychiatric guidelines in everyday practice.

Keywords: clinical practice guidelines, degree of understanding, depression, dissemination, education, implementation, schizophrenia

Effective implementation and dissemination of CPGs for psychiatry is necessary, as research has shown that CPGs have minimal effects on clinical practice in the context of mental health pharmacotherapy. The EGUIDE project is a nationwide dissemination and implementation study of CPGs for psychiatry. We revealed that the clinical knowledge of CPGs improved the EGUIDE program. We also provided evidence for the effectiveness of lecture revisions, which further improved the clinical knowledge of the CPGs. This attempt to improve the clinical knowledge of CPGs can facilitate the successful dissemination and implementation of psychiatric guidelines in everyday practice.

Abbreviations

- APA

American Psychiatric Association

- CPGs

Clinical Practice Guidelines

- EGUIDE

Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

1. INTRODUCTION

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence as well as an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care. 1 Schizophrenia and major depressive disorder (MDD) are major psychiatric disorders, and international CPGs for these two disorders, such as those from the American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2 and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 3 have been published in multiple countries. In Japan, the “Guideline for Pharmacological Therapy for Schizophrenia” (CPG for schizophrenia) was developed by the Japanese Society of Neuropsychopharmacology in 2015, 4 and the “Treatment Guideline II: Major Depressive Disorder” (CPG for MDD) was published by the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders in 2016. 5 CPG dissemination and implementation strategies for psychiatric disorders have not been established to date, 6 and it is not only psychiatric disorders where CPGs are not sufficiently applied in clinical practice. 7 , 8 Multifactorial barriers related to knowledge, attitudes, and external factors in guideline implementation have been reported. 7 , 8 , 9

To disseminate and implement these two CPGs, the Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment (EGUIDE) project was started in 2016. 10 , 11 The EGUIDE project started with the cooperation of 22 hospitals, and as of 2020, more than 180 hospitals (44 universities) participated. In brief, education programs for psychiatrists regarding these two CPGs are provided throughout Japan. The efficacy of the EGUIDE project is evaluated using three quality indicators: the degree of understanding the guidelines, the degree of practice, and the prescribing behavior of each psychiatrist. The programs are reviewed every year based on the previous year's results to improve the degree of understanding of the guidelines. The final goal of the EGUIDE project is the successful implementation of psychiatric CPGs in everyday practice. Recently, we reported that clinical knowledge of the guidelines was significantly improved after participation in the education programs. 10 In the current study, we evaluated the effect of revision of the lecture materials on the knowledge of the guidelines after attending the educational program by comparing participant data from two years.

2. METHODS

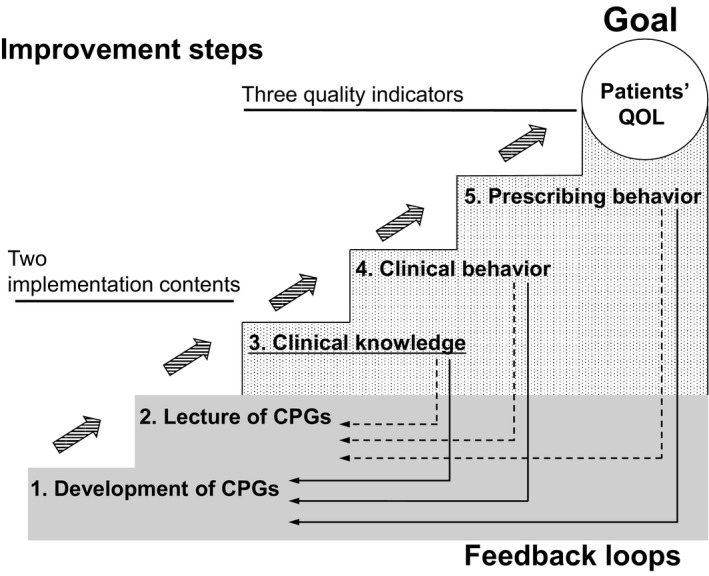

The EGUIDE project has two sets of implementation content, the development of the CPGs and lectures associated with the CPGs, and three quality indicators, clinical knowledge, clinical behavior, and prescribing behavior. 10 , 11 This study aimed to examine the effect of revision of the lecture materials on improvements in clinical knowledge in 2017 based on the feedback loop from evaluation of clinical knowledge following lectures on the CPGs (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The strategy of the EGUIDE project. The EGUIDE project has two sets of implementation content, the development of CPGs and the lectures associated with the CPGs, and three quality indicators, clinical knowledge, clinical behavior, and prescribing behavior. Striped arrows represent the flow of improvement steps. Dotted and solid arrows represent the flow of feedback loops

2.1. Participants

From October 2016 to March 2017, 212 psychiatrists participated in both the CPG for the schizophrenia program and the CPG for the MDD program. From October 2017 to March 2018, a new group of 201 psychiatrists took these two programs. 10

2.2. Assessment of clinical knowledge of schizophrenia and MDD CPGs

Clinical knowledge of the two CPGs was evaluated using a questionnaire at baseline and after the EGUIDE programs. Assessment measures on the questionnaire have been previously described. 10 A self‐administered questionnaire was created based on clinical questions of the guidelines. All items were described in Japanese and required checking correct or incorrect in the square for each question. Just before the class started and after the class ended, the participants completed a self‐administered questionnaire that assessed their knowledge of the clinical guidelines. The questionnaire for the CPG for schizophrenia consisted of seven parts (for a total of 37 questions), and the CPG for MDD consisted of eight parts (a total of 37 questions) (Table S1).

2.3. Revision of the lecture materials

The correct answer rates regarding clinical knowledge at baseline and after the EGUIDE program for the CPG for schizophrenia in the 2016 group are shown in Table S2, and those for the 2017 group are shown in Table S3. The correct answer rate regarding clinical knowledge at baseline and after the EGUIDE program for the CPG for MDD in the 2016 group is shown in Table S4, and those for the 2017 group are shown in Table S5.

In response to the low correct answer rate regarding clinical knowledge after the EGUIDE programs, we decided to revise the lecture materials for the purpose of increasing the correct answer rates. Therefore, we defined three categories based on the correct answer rates for the clinical knowledge items (category A: correct answer rates at baseline and after the program were over 90%; category B: correct answer rates were less than 90% at baseline and over 90% after the program; category C: correct answer rates at baseline and after the program were less than 90%). To examine improvements in the correct answer rates regarding clinical knowledge after the EGUIDE programs, we revised lecture materials related to the items in category C in 2016 and used the revised material in the lectures for the CPGs in 2017.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (ver. 4.0.0) with “exactRankTests” and “moments” packages. The normality of the clinical knowledge scores and participant age and professional experience were evaluated using the omnibus K‐squared test, Shapiro‐Wilk test, and Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test. The demographic differences between the two groups in age and professional experience were compared using Wilcoxon rank‐sum tests, and differences in gender were compared using Fisher's exact test. The total clinical knowledge scores at baseline and after the EGUIDE program were compared using the Wilcoxon signed‐rank tests in the 2016 and 2017 groups. The correct answer rates after the EGUIDE program for each item in the 2016 and 2017 groups were compared using Fisher's exact tests. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of participants

Of the 212 participants from October 2016 to March 2017, data for 168 participants (2016 group) were available. Of the 201 participants from October 2017 to March 2018, data for 176 (2017 group) were available. We excluded those who did not receive both of the programs, those who lacked data, and those who withdrew consent. The demographic characteristics of each group are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 33.9 ± 6.7 years (mean ± standard deviation) for the 2016 group and 33.7 ± 7.1 years for the 2017 group. The mean years of professional experience for each group were 4.9 ± 5.5 and 5.3 ± 6.6 years, respectively, and the male: female ratio of each group was 2.29 and 3.76, respectively. There were no significant differences between the 2016 and 2017 groups in age or years of professional experience (P = 0.52 and P = 0.15, respectively). However, there were significant differences in the gender ratio between the two groups (P = 0.049).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants

| 2016 group (N = 168) | 2017 group (N = 176) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (N) | Female (N) | Total (N) | Male (N) | Female (N) | Total (N) | ||

| Age (years) | 20~29 | 30 | 22 | 52 (31.0%) | 40 | 18 | 58 (33.0%) |

| 30~39 | 66 | 22 | 88 (52.4%) | 70 | 16 | 86 (48.9%) | |

| 40~49 | 16 | 6 | 22 (13.1%) | 21 | 3 | 24 (13.6%) | |

| Over 50 | 5 | 1 | 6 (3.6%) | 8 | 0 | 8 (4.5%) | |

| Professional experience (years) | 1~3 | 68 | 32 | 100 (59.5%) | 74 | 29 | 103 (58.5%) |

| 4~6 | 20 | 12 | 32 (19%) | 21 | 4 | 25 (14.2%) | |

| 7~9 | 11 | 3 | 14 (8.3%) | 15 | 1 | 16 (9.1%) | |

| Over 10 | 18 | 4 | 22 (13.1%) | 29 | 3 | 32 (18.2%) | |

N, number.

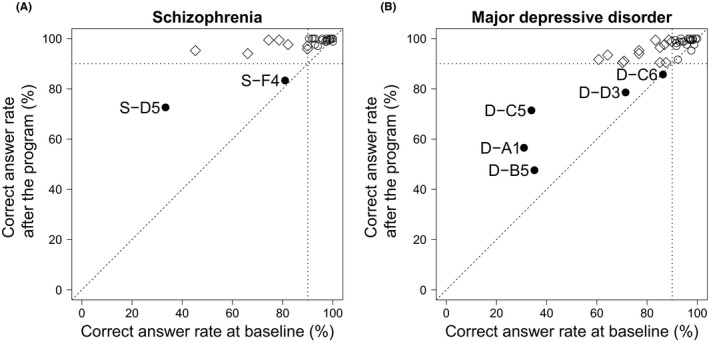

3.2. Clinical knowledge after the EGUIDE program in 2016

In the 2016 group, the total clinical knowledge scores on the CPG for schizophrenia at baseline and after the EGUIDE program were 33.6 ± 2.2 and 36.2 ± 1.0 points (P = 1.4 × 10−25). Although total scores improved after the program, the correct answer rates after the EGUIDE program of two questions did not reach over 90%, and these questions were classified as category 3 items: S‐D5 and S‐F4 (72.6% and 83.3%, respectively; Figure 2A, Additional file 1). The total clinical knowledge scores on the CPG for MDD at baseline and after the program were 31.0 ± 2.7 and 34.4 ± 1.8 points (P = 4.8 × 10−27). Although total scores improved after the program, the correct answer rates after the EGUIDE program on five questions did not reach over 90%, and these questions were classified as category 3 items: D‐A1, D‐B5, D‐C5, D‐C6, and D‐D3 (56.5%, 47.6%, 71.4%, 85.7%, 78.6%, respectively; Figure 2B, Additional file 3).

FIGURE 2.

Correct answer rates for each question regarding clinical knowledge in the 2016 group. (A) The x‐axis represents correct answer rates for each question at baseline. The y‐axis represents correct answer rates for each question after the CPG for the schizophrenia program. ● Category A: correct answer rates were over 90% at baseline and after the program (S‐A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, C1, C2, C3, D1, D2, D3, D4, E1, E4, E6, F1, F2, F3, G2, G3, G4, G5, G6, G7, and S‐G8). ◇ Category B: correct answer rates were less than 90% at baseline and over 90% after the program (S‐A4, E2, E3, E5, F5, F6, and S‐G1). ○ Category C: correct answer rates were less than 90% at baseline and after the EGUIDE program (S‐D5 and S‐F4). (B) The x‐axis represents correct answer rates for each question at baseline. The y‐axis represents correct answer rates for each question after the CPG for the MDD program. ● Category A: correct answer rates were over 90% at baseline and after the program (D‐A3, A4, A5, B1, B3, B4, C2, C3, C4, D1, E1, E2, E3, G2, G3, H1, H2, H3, and D‐H4). ◇ Category B: correct answer rates were less than 90% at baseline and over 90% after the program (D‐A2, A6, B2, C1, C7, D2, D4, F1, F2, F3, F4, G1, and D‐G4). ○Category C: correct answer rates were less than 90% at baseline and after the EGUIDE program (D‐A1, B5, C5, C6, and D‐D3)

3.3. Improvement of lectures for 2017

Based on the results of the 2016 group after the EGUIDE programs, lecture materials were revised for the 2017 group, with particular attention paid to questions with low correct answer rates: two questions for the schizophrenia CPG and five questions for the MDD CPG.

For S‐D5, an additional slide was created that emphasized not combining psychotropics such as mood stabilizers, anxiolytics, and antidepressants with antipsychotics in the lecture on the management of recurrence or relapse in schizophrenia. For S‐F4, emphasis was placed on the idea that modified electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be effective in patients with treatment‐resistant schizophrenia when clozapine is not available at the end of the lecture on the management of treatment‐resistant schizophrenia. For D‐A1, the need to accurately confirm the diagnostic criteria was emphasized in the lecture on the diagnosis of MDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5). For D‐B5, an additional slide was created, which emphasized that adverse effects of antidepressants should be carefully considered with not only children and elderly patients with MDD but also pregnant patients with MDD in the lecture on treatment of MDD. For D‐C5, it was emphasized that patient preference should be prioritized (eg, antidepressant use is not always necessary) in the management of mild depression. For D‐C6, the notion that antidepressants may be effective in patients with prior good treatment response to antidepressants and/or multiple depressive episodes was added to the lecture materials. For D‐D3, in the lecture on moderate/severe depression, an additional slide was created, which emphasized that, if necessary, benzodiazepines can be used for a short period of time.

3.4. Effects of revised lecture materials on clinical knowledge after the EGUIDE program in 2017

In the 2017 group, the total clinical knowledge scores at baseline and after the EGUIDE program with the CPG for schizophrenia were 33.2 ± 2.5 and 36.4 ± 0.8 points, respectively (P = 4.0 × 10−27). To examine the effect of the revised lecture materials on the correct answer rates after the EGUIDE program with the CPG for schizophrenia, we compared of the correct answer rates for the two category C items between the 2016 group and the 2017 group (S‐D5: 72.6% in 2016, 82.4% in 2017, P = 0.038; S‐F4: 83.3% in 2016, 86.4% in 2017, P = 0.45; Table 2). The improvement on S‐D5 did not reach statistical significance when corrected for multiple testing of two items (P > 0.025).

TABLE 2.

Correct answer rates regarding clinical knowledge after the EGUIDE program with the CPG for schizophrenia

| Schizophrenia | Items | 2016 (%) | 2017 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management of recurrence or relapse of schizophrenia | ||||

| Do not use psychotropics other than antipsychotics [correct] | S‐D5 | 72.6 | 82.4 | 0.038 |

| Management of treatment‐resistant schizophrenia | ||||

| Modified electroconvulsive therapy is recommended [correct] | S‐F4 | 83.3 | 86.4 | 0.45 |

The rates of correct answers after the EGUIDE program for each item were compared using Fisher's exact tests. The P‐values are boldfaced (P < 0.05). The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.025 for correction of multiple testing of two items.

Similarly, the total clinical knowledge scores at baseline and after the EGUIDE program with the CPG for MDD were 31.4 ± 2.6 and 34.8 ± 1.6 points, respectively (P = 2.3 × 10−27). To examine the effect of the revised lecture materials on the correct answer rates after the EGUIDE program with the CPG for MDD, we compared the correct answer rates on the five category C items between the 2016 group and the 2017 group (D‐A1: 56.5% in 2016, 60.8% in 2017, P = 0.44; D‐B5: 47.6% in 2016, 51.1% in 2017, P = 0.52; D‐C5: 71.4% in 2016, 65.9% in 2017, P = 0.30; D‐C6: 85.7% in 2016, 93.2% in 2017, P = 0.033; D‐D3: 78.6% in 2016, 89.2% in 2017, P = 8.0 × 10−3; Table 3). The difference in the correct answer rate on D‐C6 after the EGUIDE program did not reach statistical significance when corrected for multiple testing of five items (P > 0.01), but the rate exceeded 90%. The correct answer rates on D‐D3 after the EGUIDE program were significantly improved (P < 0.01) and rose to approximately 90%.

TABLE 3.

Correct answer rates regarding clinical knowledge after the EGUIDE program with the CPG for major depressive disorder

| Major depressive disorder | Items | 2016 (%) | 2017 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis of major depressive disorder (DSM‐5) | ||||

| Depressed mood and a loss of interest or pleasure most of the day, nearly every day should be present over the same two‐week period for the diagnosis [incorrect] | D‐A1 | 56.5 | 60.8 | 0.44 |

| Treatment of major depressive disorder | ||||

| The safety of antidepressants during pregnancy has not been not determined, so more attention to adverse effects should be paid when antidepressants are administered to young people than to the elderly [incorrect] | D‐B5 | 47.6 | 51.1 | 0.52 |

| Management of mild depression | ||||

| Antidepressants are not recommended when patients expect to receive psychotherapy [correct] | D‐C5 | 71.4 | 65.9 | 0.3 |

| Antidepressant use should be avoided when patients have multiple depressive episodes [incorrect] | D‐C6 | 85.7 | 93.2 | 0.033 |

| Recommended treatment for moderate/severe depression | ||||

| Combination of antidepressants and benzodiazepines or atypical antipsychotics with adequate doses and duration [incorrect] | D‐D3 | 78.6 | 89.2 | 8.0 × 10‐3 |

The rates of correct answers after the EGUIDE program for each item were compared using Fisher's exact tests. The P‐values are boldfaced (P < 0.05) and underlined (P < 0.01). The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.01 for correction of multiple testing of five items.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of the EGUIDE project is the successful implementation of CPGs for psychiatrists in everyday practice. This study evaluated clinical knowledge after revision of lecture materials in the context of a feedback loop. As a result, the total clinical knowledge scores after the EGUIDE program significantly increased in both the 2016 and 2017 groups. Among the category C items in 2016, the revised lecture materials sufficiently affected item D‐D3, which was a question about the combination of antidepressants and benzodiazepines or atypical antipsychotics in the treatment for moderate/severe depression. Our findings suggest that revising lecture materials improved clinical knowledge.

The EGUIDE project is a nationwide dissemination and implementation study for the CPGs for schizophrenia and MDD. We collected outcomes on participants in three quality indicators: the degree of understanding the guidelines, the degree of practice, and the prescribing behavior. The EGUIDE project has multiple dissemination methods and evaluation methods, each of which is improved by feedback loops and progresses step by step. To our knowledge, the EGUIDE is the first project to provide dissemination and implementation and to evaluate multiple quality indicators of CPGs in the psychiatric field.

In a meta‐analysis examining the impact of guidelines on clinical practice in psychiatry, including psychosis and MDD, Nguyen and colleagues found that CPGs frequently had minimal or insubstantial effects on clinical practice in the context of mental health pharmacotherapy. 12 In Japan, prescribing behaviors that did not follow CPGs have been repeatedly reported in the treatment of schizophrenia and MDD. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Taken together, these results suggest that it is not easy for psychiatrists to prescribe according to the CPGs and that additional trials may be needed for the successful implementation of CPGs in clinical practice. Personal factors, such as lack of awareness and/or familiarity with guidelines, have been determined to be a major factor in the barrier to CPG implementation. 7 , 8 Therefore, the supply of proper educational materials is essential to raise awareness of and increase familiarity with the CPGs. 8 Attempts to improve the degree of understanding of the treatment guidelines by revising lecture materials of educational programs each year will help to facilitate the successful implementation of psychiatric guidelines to everyday practice because knowledge influences attitudes and attitudes impact practice behavior. Item D‐D3, which showed an improvement among the clinical knowledge items, was a question regarding the combination therapy of benzodiazepines and antipsychotics with antidepressants for MDD. In Japan, polypharmacy with benzodiazepines for MDD is a serious problem, 15 so it is very meaningful to improve the correct answer rate on a clinical knowledge item that does not recommend this. Our aim is to achieve optimized treatment in psychiatry and further studies to investigate prescription patterns after EGUIDE programs will be necessary.

There are several limitations in the current study. The participants were recruited from various facilities across Japan, and they had not received common training at each facility prior to attending the EGUIDE project, although there were no significant differences in age or years of professional experience between the 2016 and 2017 groups. We have not proven lasting effects of our educational program. Now are collecting data every year by self‐evaluation as to long‐term practical degree. We are also collecting data on whether or not their prescriptions have been changed. We are planning to report these data in the future. Our sample size was small, limiting the ability to generalize the results to the approximately 14 000 psychiatrists in Japan. Correlations between the degree of understanding the guidelines and the degree of practice and prescribing behavior in the present study were not shown since the EGUIDE project was started in 2016 and is still in progress. There were still several questions with low correct answer rates in the 2017 group after the EGUIDE programs, suggesting that further revisions of the lecture materials will be needed. It is possible that the effective revision of the lecture materials was the addition of slides. We considered that other causes of low correct answer rates after the EGUIDE program were that the training materials were difficult to understand, the questions on the clinical knowledge test are not suitable, and the imprint of past lectures prevented interference with the EGUIDE program. Furthermore, not all of our questions regarding clinical knowledge of the guidelines may have real clinical implications. Based on the above, we will continue to discuss the opinions from the participants and the instructing psychiatrist of the EGUIDE project and consider improvements.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we reported improvements in clinical knowledge of the CPGs after the EGUIDE program in the 2017 group by revision of the lecture materials based on the results from the 2016 group. Achieving a good understanding of psychiatric treatment guidelines is an important step in raising awareness and increasing familiarity with these guidelines. The attempts to improve the degree of understanding of the treatment guidelines may facilitate the successful dissemination and implementation of psychiatric guidelines to everyday practice in the future.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SN and NH were involved in data collection and data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MN, RE, HE, YT, MT, TO, TN, KM, and JM were involved in the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. NY‐F, TK, HH, TT, YY, RF, HM, SO, TN, YK, AM, EK, KO, and AH contributed to the interpretation of the data and data collection. KW and KI were involved in the study design and contributed to the interpretation of the data. RH supervised the entire project, collected the data, and was involved in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to and approved the final article.

APPROVAL OF THE RESEARCH PROTOCOL BY AN INSTITUTIONAL REVIEWER BOARD

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (A2017‐105) and each participating university, hospital and clinic.

INFORMED CONSENT

All participants provided their written informed consent. Public availability of raw data was not planned in the research protocol approved by an Institution Reviewer Board. We did not obtain informed consent of the public availability.

Animal Studies: n/a.

REGISTRY AND THE REGISTRATION NO. OF THE STUDY/TRAIL

Trial registration: Effectiveness of Guideline for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment, UMIN000022645, Registered 15 June 2016, https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi‐open‐bin/ctr/ctr.cgi?function=brows&action=brows&recptno=R000026044&type=summary&language=J

Supporting information

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

Numata S, Nakataki M, Hasegawa N, et al. Improvements in the degree of understanding the treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and major depressive disorder in a nationwide dissemination and implementation study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2021;41:199–206. 10.1002/npr2.12173

Numata, Nakataki, and Hasegawa contributed equally to this work.

Funding information

This study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Number JP 18dk0307060, the AMED under Grant Number JP 19dk0307083, the Health and Labor Science Research Grants (H29‐Seishin‐Ippan‐001, 19GC1201), the Japanese Society of Neuropsychopharmacology and the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions (ie, we did not obtain informed consent on the public availability of raw data).

REFERENCES

- 1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines ; Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Psychiatry Association . Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . The treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition)‐National Clinical Practice Guideline. 2010.

- 4. Japanese Society of Neuropsychopharmacology . Guideline for Pharmacological Therapy for Schizophrenia. Tokyo: Igakusyoin; 2015. (in Japanese) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Japanese Society of Mood Disorders . Treatment Guideline Ⅱ: Major Depressive Disorder. Tokyo: Igakusyoin; 2016. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bighelli I, Ostuzzi G, Girlanda F, Cipriani A, Becker T, Koesters M, et al. Implementation of treatment guidelines for specialist mental health care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD009780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation‐a scoping review. Healthcare. 2016;4(3):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaigl G, Täumer E, Merz K, Zöscher S, Wagner S, Kösters M, et al. Multifactorial barriers in the implementation of schizophrenia and psychosocial therapies guidelines: a quantitative study across different professions. Schizophr Res. 2021;228:425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takaesu Y, Watanabe K, Numata S, Iwata M, Kudo N, Oishi S, et al. Improvement of psychiatrists' clinical knowledge of the treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and major depressive disorders using the 'Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in Psychiatric Treatment (EGUIDE)' project: A nationwide dissemination, education, and evaluation study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73:642–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ichihashi K, Hori H, Hasegawa N, Yasuda Y, Yamamoto T, Takashi T et al. Prescription patterns in patients with schizophrenia in Japan: first‐quality indicator data from the survey of “Effectiveness of Guidelines for Dissemination and Education in psychiatric treatment (EGUIDE)” project. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2020;40(3):281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nguyen T, Seiler N, Brown E, O'Donoghue B. The effect of Clinical Practice Guidelines on prescribing practice in mental health: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ito H, Koyama A, Higuchi T. Polypharmacy and excessive dosing: psychiatrists' perceptions of antipsychotic drug prescription. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:243–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Uchida H, Suzuki T, Mamo DC, Mulsant BH, Tsunoda K, Takeuchi H, et al. Survey of benzodiazepine and antidepressant use in outpatients with mood disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:244–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Onishi Y, Hinotsu S, Furukawa TA, Kawakami K. Psychotropic prescription patterns among patients diagnosed with depressive disorder based on claims database in Japan. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakagawa A, Williams A, Sado M, Oguchi Y, Mischoulon D, Smith F, et al. Comparison of treatment selections by Japanese and US psychiatrists for major depressive disorder: a case vignette study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69:553–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang SY, Chen LY, Najoan E, Kallivayalil RA, Viboonma K, Jamaluddin R, et al. Polypharmacy and psychotropic drug loading in patients with schizophrenia in asian countries: fourth survey of research on Asian prescription patterns on antipsychotics. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72:572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takahashi T, Otsubo T, Kunisawa S, Noriko S, Imanaka Y. Factors associated with high‐dose antipsychotic prescriptions in outpatients with schizophrenia: an analysis of claims data from a Japanese prefecture. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2020;40(3):224–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Usuki M, Kamiura Y, Okubo R, Yamanouchi Y. National database study on the use of long‐acting antipsychotic injections and hospital readmission proportions in patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74:211–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions (ie, we did not obtain informed consent on the public availability of raw data).