Abstract

Objectives:

Given the need to understand e-cigarette retail and its impact, we examined sociodemographic, tobacco and marijuana use, and e-cigarette retail experiences as correlates of (1) past 30-day e-cigarette use, (2) past 30-day advertising/media exposure, and (3) point-of-sale age verification among young adults.

Methods:

We analyzed baseline survey data (September-December, 2018) among 3006 young adults (ages 18–34) in 6 metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, San Diego, Seattle) in a 2-year longitudinal study.

Results:

In this sample (Mage = 24.6, 42.3% male, 71.6% white, 11.4% Hispanic), 37.7% (N = 1133) were past 30-day e-cigarette users; 68.6% (N = 2062; non-users: 66.0%, users: 72.9%) reported past 30-day e-cigarette-related advertising/media exposure. Among e-cigarette users, vape shops were the most common source of e-cigarettes (44.7%) followed by online (18.2%). Among users, 34.2% were “almost always” asked for age verification. In multilevel logistic regression, e-cigarette use and advertising/media exposure were correlated (and both correlated with being younger). E-cigarette use also correlated with other tobacco product and marijuana use (and being male and white). Infrequent age verification correlated with commonly purchasing e-cigarettes online (and being older and black).

Conclusions:

Increased efforts are needed to reduce young adult advertising/media exposure and increase retailer compliance among retailers, particularly online and vape shops.

Keywords: tobacco control, tobacco policy, alternative tobacco products, e-cigarettes, retail marketing, point-of-sale

E-cigarettes have become an increasingly prominent public health controversy globally and domestically.1 Despite some literature indicating that e-cigarettes may deliver fewer harmful chemicals than traditional cigarettes and potentially support cessation efforts,2–4 e-cigarettes contain chemicals that may increase risks of addiction and disease.5 E-cigarette use is disproportionately prevalent among young adults.5 However, the existing literature regarding e-cigarette use among young adults is limited by little consideration of multilevel influences on use (eg, individual tobacco/substance use history, tobacco retail and marketing context,6 tobacco control environment7). In particular, the tobacco retail environment and related marketing – which aim to expand markets, attract new users, promote continued use, and shape perceptions of products and their use8–13 – are critical considerations that inform regulatory policy.

E-cigarettes are sold in traditional tobacco retailers (eg, convenience stores, food, liquor, and mass merchandise channels), vape shops, other specialty tobacco shops, and online.14 Traditional tobacco retailers account for about half of sales;14 in particular, the proportions of convenience stores selling e-cigarettes range from 73% to 86%.15,16 Vape shops (ie, stores that exclusively sell e-cigarettes and related products, eg, e-liquids) account for ~19% of sales;14 vape shops are unique retail settings because of the diversity of the products they sell and the promotional strategies used (eg, experimenting and socializing at tasting bars).17,18 Tobacco/smoke/head shops that specialize in tobacco products and accessories (eg, hookah tobacco/pipes, blunt wraps, bongs) also sell e-cigarettes.19 Online sources account for ~28% of e-cigarette dollar sales.14

Beyond being a source of e-cigarettes, retail serves as a major source of advertising. Prior research indicates that young people are most likely to see advertisements at retail stores (68%), followed by the Internet (41%, including social media20), television (38%), and newspapers/magazines (24%).21 Such advertising is designed to influence how and why consumers use e-cigarettes22–24 (eg, perceptions of safety or use for cessation of combustibles,18,22,23,25 social use, to achieve a “buzz,” for entertainment22,23) and has been shown to impact young adults’ perceptions and use of e-cigarettes.26,27

Tobacco control policies have a role in regulating the retail environment, and thus, also e-cigarette and other tobacco use. At the federal level, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finalized a rule in 2016 extending the Center for Tobacco Products’ regulatory authority to cover e-cigarettes, including retail and marketing (eg, packaging, advertising, promotion, sale).28 State and local policies (eg, cigarette taxation, smoke-free air policies) are also critical in addressing tobacco and e-cigarette use.7 There have been a number of advances in tobacco control, such as the federal increase of minimum legal sales age for tobacco in 2020, prior state and local implementation of such policies, and sales restrictions on flavored tobacco products at local, state, and federal levels.29–31 Notably, there are vast differences at the state and local level regarding the progressiveness of tobacco control policies (eg, how restrictive legislation is on retail and marketing), how tobacco control policies are implemented,32 and inclusion of e-cigarettes in such policies.30 Moreover, given high co-use of e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and marijuana33,34 and the implications of marijuana in e-cigarette/vaping-associated lung injuries,35 the policy and marijuana retail environment in states where non-medical retail is legalized are also important contextual factors.31

Age verification at point-of-sale is a critical component of regulatory efforts aimed at tobacco prevention.7 Federal regulations require age verification with a photograph ID for anyone under age 27 to purchase tobacco. A 2018 study of age verification in tobacco and vape shops in California documented higher rates of age verification violations (49.8%) and underage sales (44.7%) among tobacco and vape shops relative to other types of retailers (eg, liquor stores, convenience stores); moreover, age verification rates were lower for sales of e-cigarettes versus cigarettes.36 Our prior research documented similarly low rates of age verification among vape shops in 6 metropolitan areas.37 Furthermore, one study found that roughly two-thirds of online e-cigarette vendors have no age verification processes in place.38

The current paper examines sociodemographics, tobacco and marijuana use, and e-cigarette retail experiences as correlates of (1) past 30-day e-cigarette use, (2) past 30-day exposure to e-cigarette advertising/media, and (3) frequency of age verification upon purchasing e-cigarette products. Based on the aforementioned literature, we hypothesized that other tobacco and marijuana use would be positively associated with e-cigarette use, e-cigarette use would be associated with greater odds of advertising/media exposure, and that most commonly purchasing e-cigarette products online and at vape or tobacco shops would be associated with less frequent age verification.

METHODS

Study Design

We analyzed baseline survey data (collected in September-December 2018) among 3006 young adults in the Vape shop Advertising, Place characteristics and Effects Surveillance (VAPES) study. The VAPES study examines the vape shop retail environment and its impact on e-cigarette and tobacco use among young adults aged 18–34 (as defined by the US Census Bureau).39 VAPES focuses on 6 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs: Atlanta, GA; Boston, MA; Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN; Oklahoma City, OK, San Diego, CA; Seattle, WA) selected for their variation in terms of state policies regarding tobacco control (Supplementary Table 1).30 At baseline, California had the strongest tobacco control; Georgia had the weakest;32 this gradient also applied to e-cigarettes.30 California and Washington also had retail markets for non-medical marijuana use at the time of assessment.31

This longitudinal survey, launched in fall 2018, consisted of individual assessments every 6 months for 2 years (September-December; March-May), with the mid-year assessments (in March-May) consisting of brief assessments of only key variables (eg, tobacco use).

Participants and Recruitment

Potential participants were recruited via social media. Participant eligibility criteria were: (1) being 18–34 years old; (2) residing in a zip code contained in one of the 6 MSAs; and (3) being English speaking. Purposive, quota-based sampling also was used to ensure sufficient proportions of the sample representing e-cigarette and cigarette users (roughly one-third each) to examine changes among e-cigarette and cigarette use over time (eg, transitions from single product use to co-use to non-use); we anticipated overlap in the e-cigarette and cigarette users (~50%).40,41 The sample also was intended to contain about equal numbers of men and women and 40% racial/ethnic minority to explore use within subgroups.

To obtain this sample, ads posted on Facebook and Reddit targeted individuals: (1) using indicators reflecting those within the eligible age range and locations (within 15 miles of their respective MSAs); (2) by identifying work groups or activities of interest that appeal to young adults, for example, targeting those who followed, “liked,” or were group members of pages related to sports/athletics, entertainment, arts, lifestyle, technology, fashion, and music (eg, hip-hop), as well as tobacco-related interests (eg, Marlboro, Juul, other e-cigarettes, Swisher Sweets); and (3) by posting advertisements including images of young adults of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds socializing in bars and/or out-door spaces, young adult professionals in professional work settings, etc. Tag lines for ads included “Help Emory University researchers learn more about what young adults in your city think about tobacco products!” “Communities of young adults: Researchers at Emory University want to know your world!” or “Smok’n? Vape’n? Researchers at Emory University want to know your thoughts!”

Potential participants who clicked on an ad were directed to a webpage with a study description and consent form. Individuals who consented were screened for eligibility. This screener included questions regarding sex, race, ethnicity, and past 30-day use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes to facilitate reaching recruitment targets of subgroups in each MSA (ie, limiting participation among specific subgroups once their target enrollment was reached). Subgroup enrollment was capped by MSA (ie, Boston and Minneapolis survey enrollment eventually closed to women and non-users of e-cigarettes and cigarettes; Atlanta enrollment closed to women and male non-users; Seattle enrollment closed to women). Eligible individuals allowed to advance were then routed to complete the online baseline survey (administered via SurveyGizmo). Participants were notified that 7 days after completing the baseline survey they would be asked to confirm their participation by clicking a “confirm” button included in an email sent to them. The email reiterated study procedures and timeline. Once participants clicked “confirm,” they were enrolled into the study and emailed a $10 Amazon e-gift card.

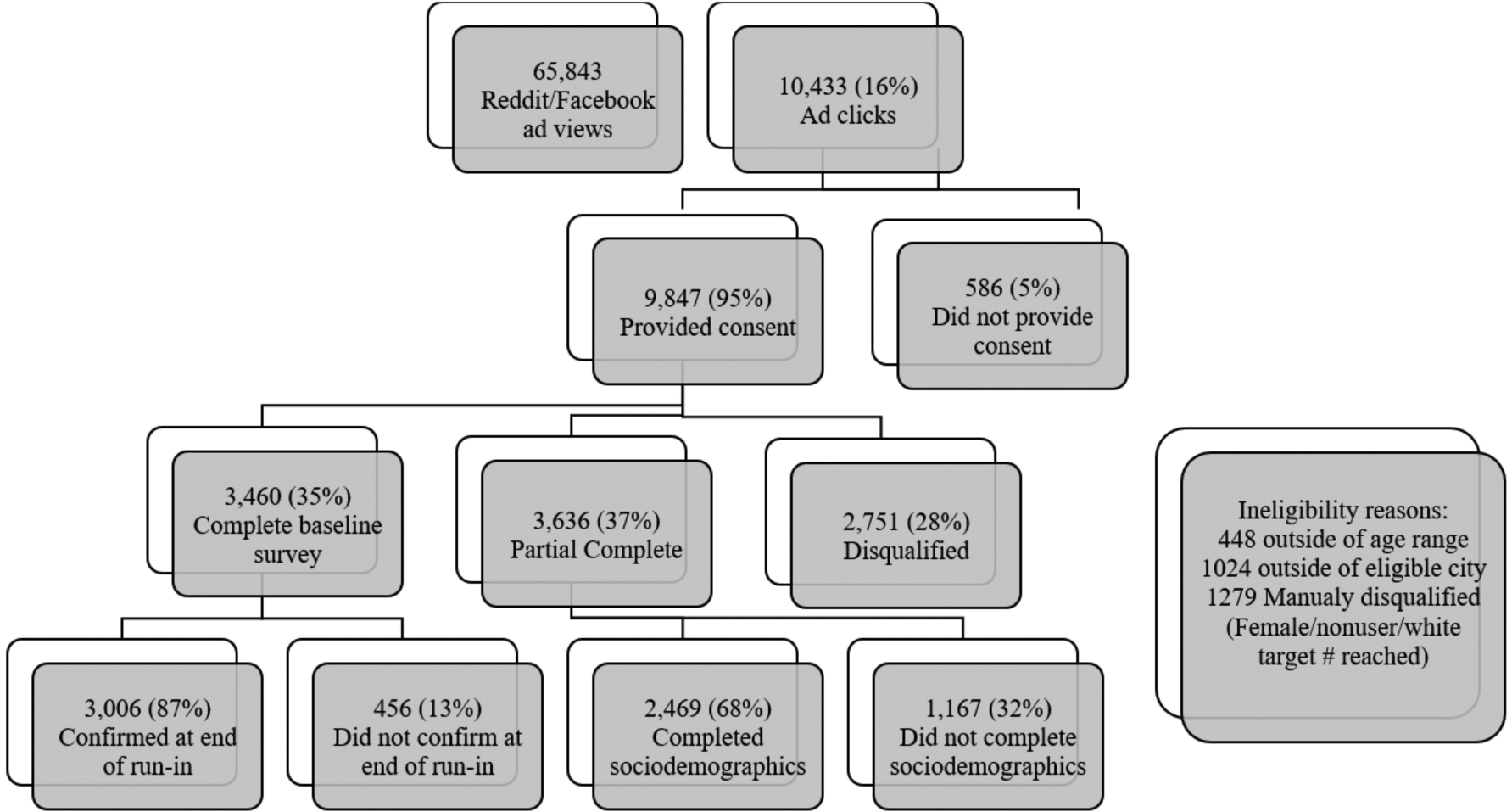

The participant flowchart is included in Figure 1. The duration of the recruitment period ranged from 87 to 104 days across MSAs (< 90 days for Atlanta, Boston, and Minneapolis; > 90 days for Seattle, San Diego and Oklahoma City). Of the 10,433 Facebook and Reddit users who clicked on ads, 9847 consented, of which 2751 (27.9%) were not allowed to advance because they were either: (1) ineligible (N = 1427) and/or (2) excluded to reach subgroup target enrollment (N = 1279). Of those allowed to advance to the survey, the proportion of completers versus partial completers was 48.8% (3460/7096) versus 51.2% (3635/7096). Partial completes were deemed ineligible for the remainder of the study; the majority of partial completers (N = 2469, 67.9%) completed only the initial sociodemographic section of the survey (Supplementary Table 2 contains data regarding completers vs non-completers). Of the 3460 who completed the baseline survey, 3006 (86.9%) confirmed participation at the 7-day follow-up (Supplementary Table 2 contains data regarding confirmers vs non-confirmers). Confirmation response rates varied from 83% (Seattle MSA) to 91% (Boston MSA).

Figure 1.

Participant Recruitment Flowchart

Measures

Sociodemographics.

Participants were asked to report their age, sex, sexual orientation (heterosexual/straight, gay/lesbian/homosexual, bisexual, other), race, ethnicity, whether they were born in or outside the US, highest level of educational attainment, current employment status, relationship status, and whether they had children (under age 18) in their home.

Tobacco and marijuana use.

Participants were asked to report whether they had used the following drugs in their lifetime: e-cigarettes, cigarettes, hookah/waterpipe, little cigars/cigarillos, large cigars, smokeless tobacco, or marijuana. For those indicating lifetime use, they were asked to indicate frequency of use in the past 6 months; users in the past 6 months were asked to report the number of days they used the product in the past 30 days. Participants were able to refuse responding to marijuana-related assessments. Lifetime and past 30-day use were operationalized as dichotomous variables (yes vs no).

Among lifetime e-cigarette users, we assessed age at first use, age at first regular use (with the option to indicate never regular use). Among past 30-day users, we assessed average puffs per day on days used, whether they typically used e-liquids containing nicotine salt, whether they used open or closed tank systems, and rechargeable or disposable devices.

E-cigarette advertising/media exposure.

All participants were asked: “During the past 30 days, how many times you have you seen ads/promotions, coupons, or discounts for a vape shop, buying an e-cigarette device or vaporizer, or buying e-liquids or e-juices? 0 times; 1–2 times; 3–5 times; 6–10 times; > 10 times.” We also asked: “During the past 30 days, how many times have you seen reviews or recommendations for vape shops, e-cigarette devices or vaporizers, or e-liquids or e-juices?” and used the same response options. We then dichotomized these 2 variables as any exposure versus none and created an aggregate variable indicating any exposure to ads/promotions, coupons, discounts, reviews, or recommendations (ie, “e-cigarette advertising/media exposure”) versus no exposure; this latter variable was used as an outcome in multivariable regression analyses. We then asked: “Where did you see any of the above mentioned ads, reviews, or promotions? (Check all that apply.): billboards; retailers [inside/outside]; TV; radio; magazines/newspapers; direct mail; email; social media sites; blogging sites; other sources.”

E-cigarette purchase locations.

E-cigarette ever users were asked: “Where did you first purchase an e-cigarette? vape shop; online via a site connected to a local vape shop; online via a vendor not connected to a local vape shop; gas station; convenience store; grocery store; pharmacy; tobacco specialty store (eg, smoke shop); liquor store; other (specify); or never purchased an e-cigarette.” Past 30-day users were asked: “Where do you most commonly purchase e-cigarettes and e-liquids?” and were given the same response options. Given the small numbers, pharmacies and liquor stores were combined with “other;” we aggregated online (whether connected to a local vape shop or not) and collapsed convenience stores and gas stations (referent group).

Age verification.

Past 30-day e-cigarette users were asked: “When you buy e-cigarettes, how frequently are you asked to provide an ID to verify your age? never; rarely; sometimes; often; or almost always.” For multivariable regression analyses, this variable was dichotomized as “never/rarely/sometimes” asked to provide age verification versus “often/almost always” (referent group).

Data Analysis

To characterize subsamples across the MSAs, chi-square tests, t-tests, and ANOVA were used to explore differences in sociodemographic, tobacco and marijuana use, and e-cigarette retail experiences across MSAs. Primary outcomes were grouped: (1) past 30-day e-cigarette use (yes vs no); (2) past 30-day e-cigarette advertising/media exposure (yes vs no); and (3) frequency of age verification among e-cigarette users (< often vs often/almost always). For each outcome, we conducted bivariate analyses and then multilevel logistic regression modeling to examine covariates (ie, sociodemographic variables) and predictors of interest in relation to the primary outcomes. For the outcome of past 30-day e-cigarette use, predictors of interest included e-cigarette advertising/media exposure and past 30-day use of cigarettes, other tobacco, and marijuana. For the outcome of past 30-day e-cigarette advertising/media exposure, predictors of interest included past 30-day use of e-cigarettes, cigarettes, other tobacco product, and marijuana; we also modeled this outcome among e-cigarette users and included most common e-cigarette purchase location as a predictor. For the age verification outcome, predictors of interest included most common e-cigarette purchase location and sociodemographics.

Multilevel models were used to take into account hierarchical structure of the data (individuals nested in 6 MSAs).42–44 We examined whether MSA or strength of state tobacco control policies were associated with outcomes. However, intra-class correlations (ICCs) were low (range: 0.003 to 0.020); the recruitment strategy was not intended to yield representative samples across MSAs, and the number of MSAs also limit the extent to which tobacco control context would explain individual-level variation. Models did not include all sociodemographics due to multicollinearity (ie, US-born vs foreign-born correlated with race/ethnicity so only race/ethnicity included; age correlated with education, employment, relationship status, and children in the home so only age was included). All descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26;45 multilevel regression modeling was conducted using R version 4.0.0.46

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics across MSAs

Sociodemographics.

On average, participants were 24.56 years old (SD = 4.72), 42.3% male, 68.4% heterosexual, 71.6% white, and 11.4% Hispanic; 73.3% had ≥ bachelor’s degrees, and 62.4% were single. Sociodemographic differences across MSAs were identified (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographics and Past 30-day Tobacco and Marijuana Use among Young Adults in 6 US MSAs Assessed September-December 2018, N = 3006

| Variables | Total N = 3006 |

San Diego N = 474 |

Boston N = 575 |

MSP N = 543 |

Seattle N = 502 |

OKC N = 319 |

Atlanta N = 593 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | p | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||

| Age, M (SD) | 24.56 (4.72) | 24.84 (4.99) | 24.40 (4.56) | 23.78 (4.44) | 24.39 (4.65) 25.43 (4.87) | 24.86 (4.75) | < .001 | |

| Male, N (%)* | 1271 (42.3) | 205 (43.2) | 240 (41.7) | 233 (42.9) | 219 (43.6) | 125 (39.2) | 249 (42.0) | < .001 |

| Sexual minority, N (%) | 950 (31.6) | 115 (24.3) | 191 (33.2) | 218 (40.1) | 200 (39.8) | 91 (28.5) | 135 (22.8) | < .001 |

| Race, N (%) | < .001 | |||||||

| White | 2151 (71.6) | 315 (66.5) | 425 (73.9) | 447 (82.3) | 368 (73.3) | 255 (79.9) | 341 (57.5) | |

| Black | 159 (5.3) | 13 (2.7) | 21 (3.7) | 20 (3.7) | 13 (2.6) | 8 (2.5) | 84 (14.2) | |

| Asian | 367 (12.2) | 67 (14.1) | 82 (14.3) | 32 (5.9) | 54 (10.8) | 16 (5.0) | 116 (19.6) | |

| Other | 329 (11.0) | 79 (16.7) | 47 (8.2) | 44 (8.1) | 67 (13.4) | 40 (12.6) | 52 (8.7) | |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 343 (11.4) | 118 (24.9) | 53 (9.2) | 34 (6.3) | 47 (9.4) | 30 (9.4) | 61 (10.3) | < .001 |

| Foreign born, N (%) | 286 (9.5) | 43 (9.1) | 61 (10.6) | 36 (6.6) | 38 (7.6) | 18 (5.6) | 90 (15.2) | < .001 |

| Education ≥ bachelor’s degree, N (%) | 2203 (73.3) | 339 (71.5) | 458 (79.7) | 395 (72.7) | 322 (64.1) | 208 (65.2) | 481 (81.1) | < .001 |

| Employment, N (%) | < .001 | |||||||

| Student | 825 (27.4) | 145 (30.6) | 204 (35.5) | 129 (23.8) | 106 (21.1) | 53 (16.6) | 188 (31.7) | |

| Unemployed | 244 (8.1) | 47 (9.9) | 33 (5.7) | 30 (5.5) | 53 (10.6) | 38 (11.9) | 43 (7.3) | |

| Full-time | 1202 (40.0) | 170 (35.9) | 222 (38.6) | 222 (40.9) | 202 (40.2) | 151 (47.3) | 235 (39.6) | |

| Part-time | 735 (24.5) | 112 (23.6) | 116 (20.2) | 162 (29.8) | 141 (28.1) | 77 (24.1) | 127 (21.4) | |

| Relationship status, N (%) | < .001 | |||||||

| Single | 1876 (62.4) | 295 (62.2) | 391 (68.0) | 353 (65.0) | 301 (60.0) | 144 (45.1) | 392 (66.1) | |

| Married/living with partner | 1089 (36.2) | 173 (36.5) | 178 (31.0) | 183 (33.7) | 194 (38.6) | 170 (53.3) | 191 (32.2) | |

| Other | 41 (1.4) | 6 (1.3) | 6 (1.0) | 7 (1.3) | 7 (1.4) | 5 (1.6) | 10 (1.7) | |

| Children in the home, N (%) | 611 (20.3) | 108 (22.8) | 71 (12.3) | 90 (16.6) | 115 (22.9) | 124 (38.9) | 103 (17.4) | < .001 |

| Past 30-day tobacco and marijuana use, N (%) | ||||||||

| E-cigarettes | 1133 (37.7) | 171 (36.1) | 188 (32.7) | 217 (40.0) | 247 (49.2) | 134 (42.0) | 176 (29.7) | < .001 |

| Cigarettes | 808 (26.9) | 117 (24.7) | 129 (22.4) | 159 (29.3) | 195 (38.8) | 86 (27.0) | 122 (20.6) | < .001 |

| Hookah | 278 (9.2) | 40 (8.4) | 37 (6.4) | 52 (9.6) | 46 (9.2) | 27 (8.5) | 76 (12.8) | .010 |

| Little cigars/cigarillos | 378 (12.6) | 52 (11.0) | 51 (8.9) | 75 (13.8) | 85 (16.9) | 44 (13.8) | 71 (12.0) | .003 |

| Large cigars | 213 (7.1) | 31 (6.5) | 39 (6.8) | 40 (7.4) | 29 (5.8) | 30 (9.4) | 44 (7.4) | .497 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 105 (3.5) | 27 (5.7) | 18 (3.1) | 13 (2.4) | 17 (3.4) | 10 (3.1) | 20 (3.4) | .103 |

| Marijuana | 1178 (39.2) | 190 (40.1) | 227 (39.5) | 214 (39.4) | 277 (55.2) | 95 (29.8) | 175 (29.4) | < .001 |

Note.

All p-values indicate omnibus tests (per ANOVA and chi-square) across MSAs.

87 reported “other” sex.

Tobacco and marijuana use characteristics.

Supplementary Table 3 shows lifetime prevalence of tobacco and marijuana use. Table 1 shows past 30-day tobacco and marijuana use prevalence. Lifetime and past 30-day e-cigarette use prevalence was 57.7% (N = 1735) and 37.7% (N = 1133), respectively. Lifetime and past 30-day cigarette use was 61.8% and 26.9%; lifetime and past 30-day marijuana use prevalence was 70.7% and 39.2%.

To characterize e-cigarette user profiles further, 394 participants (13.1% of the total sample, 34.8% of the 1133 past 30-day users) used e-cigarettes exclusively, not other tobacco products or marijuana. Among past 30-day e-cigarette users, 50.4% (N = 570) reported past 30-day use of cigarettes, 17.7% (N = 201) hookah, 25.3% (N = 287) little cigars/cigarillos, 13.2% (N = 150) smokeless tobacco, and 59.8% (N = 678) used marijuana. Considering e-cigarette and cigarettes, 19.0% (N = 571) were past 30-day users of both products, 18.7% (N = 562) used e-cigarettes but not cigarettes, and 7.9% (N = 237) used cigarettes but not e-cigarettes. Considering e-cigarettes and marijuana, 22.6% (N = 678) were past 30-day users of both, 15.1% (N = 455) used e-cigarettes but not marijuana, and 16.6% (N = 500) used marijuana but not e-cigarettes.

With regard to e-cigarette use history and characteristics, among lifetime e-cigarette users, age of first use was 20.44 (SD = 4.25), and age of first regular use was 21.56 (SD = 4.28). Among past 30-day e-cigarette users, the average number of days used in the past 30 days was 17.65 (SD = 11.94, with 75.8% reporting use on ≥ 5 days), and the average number of puffs per day was 33.40 (SD = 34.99). Also, 27.1% (N = 307) typically used e-liquids containing nicotine salt, 67.5% (N = 765) typically used open system e-cigarette devices, and 93.5% (N = 1059) used rechargeable devices (Supplementary Table 3).

E-cigarette advertising/media exposure.

About two-thirds of participants (68.6%; 66.0% in non-users vs 72.9% in users; Table 2) reported past 30-day exposure to ads, promotions, coupons, or discounts (63.8%) or reviews/recommendations (38.2%), with statistically significant differences across MSAs (range: Minneapolis = 65.6%, Oklahoma City = 75.9%; p = .032; Supplementary Table 3). Promotions were most commonly seen on social media (43.4%), at retailers (31.7%), on bill-boards (20.3%), and in print media (ie, magazines/newspapers, 12.7%).

Table 2.

Bivariate Analyses Examining Correlates of Past 30-day E-cigarette Use, E-cigarette Advertising/Media Exposure and Point-of-Sale Age Verification (Almost Always or Often vs Never, Rarely or Sometimes) among Young Adults in 6 US MSAs Assessed September-December 2018, N = 3006

| Total | Past 30-day e-cigarette use | Advertising/media exposure | Frequency of age verification at point-of-salea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | Almost always or often | Never, rarely or sometimes | |||||

| N = 3006 (100%) |

N = 1873 (62.3%) |

N = 1133 (37.7%) |

N = 944 (31.4%) |

N = 2062 (68.6%) |

N = 554 (48.9%) |

N = 579 (51.1%) |

||||

| Variables | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | p | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | p | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | p |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||

| Age, M (SD) | 24.56 (4.72) | 24.95 (4.64) | 23.91 (4.78) | < .001 | 24.90 (4.75) | 24.40 (4.69) | .007 | 23.04 (4.34) | 24.74 (5.02) | < .001 |

| Male, N (%)b | 1271 (42.3) | 735 (39.2) | 536 (47.3) | < .001 | 391 (41.4) | 880 (42.7) | .809 | 262 (47.3) | 274 (47.3) | .812 |

| Sexual minority, N (%) | 950 (31.6) | 548 (29.3) | 402 (35.5) | < .001 | 282 (29.9) | 668 (32.4) | .167 | 218 (39.4) | 184 (31.8) | .008 |

| Race, N (%) | < .001 | .009 | .091 | |||||||

| White | 2151 (71.6) | 1299 (69.4) | 852 (75.2) | 668 (70.8) | 1483 (71.9) | 429 (77.4) | 423 (73.1) | |||

| Black | 159 (5.3) | 116 (6.2) | 43 (3.8) | 62 (6.6) | 97 (4.7) | 14 (2.5) | 29 (5.0) | |||

| Asian | 367 (12.2) | 277 (14.8) | 90 (7.9) | 129 (13.7) | 238 (11.5) | 45 (8.1) | 45 (7.8) | |||

| Other | 329 (11.0) | 181 (9.7) | 148 (13.1) | 85 (9.0) | 244 (11.8) | 66 (11.9) | 82 (14.2) | |||

| Hispanic, N (%) | 343 (11.4) | 188 (10.0) | 155 (13.7) | .002 | 93 (9.9) | 250 (12.1) | .069 | 73 (13.2) | 82 (14.2) | .629 |

| Foreign born, N (%) | 286 (9.5) | 208 (11.1) | 78 (6.9) | < .001 | 108 (11.4) | 178 (8.6) | .015 | 44 (7.9) | 34 (5.9) | .169 |

| Education ≥ bachelor’s degree, N (%) | 2203 (73.3) | 1489 (79.5) | 714 (63.0) | < .001 | 694 (73.5) | 1509 (73.2) | .847 | 353 (63.7) | 361 (62.3) | .633 |

| Employment, N (%) | < .001 | .410 | .014 | |||||||

| Student | 825 (27.4) | 531 (28.4) | 294 (25.9) | 259 (27.4) | 566 (27.4) | 166 (30.0) | 128 (22.1) | |||

| Unemployed | 244 (8.1) | 154 (8.2) | 90 (7.9) | 85 (9.0) | 159 (7.7) | 37 (6.7) | 53 (9.2) | |||

| Full-time | 1202 (40.0) | 780 (41.6) | 422 (37.2) | 384 (40.7) | 818 (39.7) | 193 (34.8) | 229 (39.6) | |||

| Part-time | 735 (24.5) | 408 (21.8) | 327 (28.9) | 216 (22.9) | 519 (25.2) | 158 (28.5) | 169 (29.2) | |||

| Relationship status, N (%) | .473 | .391 | .480 | |||||||

| Single | 1876 (62.4) | 1182 (63.1) | 694 (61.3) | 602 (63.8) | 1274 (61.8) | 349 (63.0) | 345 (59.6) | |||

| Married/living with partner | 1089 (36.2) | 668 (35.7) | 421 (37.2) | 327 (34.6) | 762 (37.0) | 196 (35.4) | 225 (38.9) | |||

| Other | 41 (1.4) | 23 (1.2) | 18 (1.6) | 15 (1.6) | 26 (1.3) | 9 (1.6) | 9 (1.6) | |||

| Children in the home, N (%) | 611 (20.3) | 348 (18.6) | 263 (23.2) | .002 | 186 (19.7) | 425 (20.6) | .566 | 112 (20.2) | 151 (26.1) | .019 |

| Past 30-day use, N (%) | ||||||||||

| E-cigarettes | 1133 (37.7) | -- | -- | -- | 307 (32.5) | 826 (40.1) | < .001 | -- | -- | |

| Cigarettes | 808 (26.9) | 237 (12.7) | 571 (50.4) | < .001 | 228 (24.2) | 580 (28.1) | .022 | 257 (46.4) | 314 (54.2) | .008 |

| Other tobacco products | 661 (22.0) | 191 (10.2) | 470 (41.5) | < .001 | 191 (20.2) | 470 (22.8) | .116 | 222 (40.1) | 248 (42.8) | .346 |

| Marijuana | 1178 (39.2) | 500 (26.7) | 678 (59.8) | < .001 | 364 (38.6) | 814 (39.5) | .663 | 357 (64.4) | 321 (55.4) | .002 |

| Past 30-day ad/media exposure, N (%) | ||||||||||

| Ads, promotions, coupons, discounts | 1918 (63.8) | 1180 (63.0) | 738 (65.1) | .238 | -- | -- | -- | 354 (63.9) | 384 (66.3) | .392 |

| Reviews or recommendations | 1149 (38.2) | 551(29.4) | 598 (52.8) | < .001 | -- | -- | 288 (52.0) | 310 (53.5) | .600 | |

| Either of the above | 2062 (68.6) | 1236 (66.0) | 826 (72.9) | < .001 | -- | -- | 409 (73.8) | 417 (72.0) | .494 | |

| Most common purchase location, N (%)ƚ | N = 935 | -- | N = 245 | N = 690 | N = 486 | N = 449 | ||||

| Gas station/convenience store | 139 (14.8) | -- | -- | 44 (18.0) | 95 (13.8) | .050 | 82 (16.9) | 57 (12.7) | .020 | |

| Online | 206 (22.0) | -- | -- | 40 (16.3) | 166 (24.1) | 90 (18.5) | 116 (25.8) | |||

| Vape shop | 506 (54.1) | -- | -- | 136 (55.5) | 370 (53.6) | 265 (54.5) | 241 (53.7) | |||

| Tobacco specialty shop | 84 (9.0) | -- | -- | 25 (10.2) | 59 (8.6) | 49 (10.1) | 35 (7.8) | |||

Note.

p-values indicate omnibus tests (per t-tests and chi-square).

Among past 30-day e-cigarette users.

87 reported “other” sex.

Among past 30-day e-cigarette users who reported purchasing e-cigarettes (excluding “other” purchase locations), N = 935.

E-cigarette purchase locations.

Among lifetime e-cigarette users, the majority had purchased e-cigarettes (52.1%, N = 904) and/or e-liquid in their lifetime (52.2%, N = 906; Supplementary Table 3). The most common place of first e-cigarette purchase among lifetime e-cigarette users was vape shops (28.0%). Past 30-day e-cigarette users most commonly purchased vape products from vape shops (44.7%), followed by online (18.2%; 13.8% via websites connected to local vape shops; 4.4% via websites not connected to local vape shops), gas stations/convenience stores (12.3%), and tobacco specialty stores (7.4%). Vape shops were most prominent in Oklahoma City (44.6% first purchase among lifetime users and 59.7% most commonly purchase among past 30-day users) and least prominent in Boston and San Diego (26.6% and 24.6% first purchase among lifetime users and 33.5% and 34.5% most commonly purchase among past 30-day users; ps < .001), which parallels the retail environment in those MSAs.47

Age verification.

Notably, 17.6% of past 30-day e-cigarette users reported never being asked for age verification upon purchase, 14.9% rarely, 18.6% sometimes, 14.7% often, and 34.2% almost always (Table 2). Given that, at the time of data collection, federal regulations required age verification with a photograph ID for anyone under age 27 to purchase tobacco products, we also conducted these analyses restricting our sample to those under the age of 27; the proportions representing those who reported never, rarely, sometimes, often, and almost always asked for age verification were 16.3%, 13.0%, 16.6%, 15.8%, and 38.3%, indicating a slightly greater proportion indicating never/rarely (29.3% vs. 22.7% other responses).

“Never” was most frequently reported in Oklahoma City and San Diego (26.1% and 21.6%, respectively), and “almost always” was least frequently reported in these same MSAs (28.4% and 28.1%, respectively). Almost always was reported most frequently by participants in Minneapolis-St. Paul (41.5%, p = .026; Supplementary Table 3).

Bivariate and Multivariate Analyses

E-cigarette use.

In bivariate analyses (Table 2), statistically significant correlates of past 30-day e-cigarette use included being younger (p < .001), male (p < .001), sexual minority (p < .001), white (p < .001), non-Hispanic (p = .002), born in the US (p < .001), with less than a bachelor’s degree (p < .001), employed part-time (p < .001), in households with children, and past 30-day users of cigarettes and marijuana (ps < .001), as well as e-cigarette advertising/media exposure (ps < .001). In the multilevel binary regression model (Table 3), past 30-day e-cigarette use was correlated with e-cigarette advertising/media exposure (p = .004) and cigarette, other tobacco, and marijuana use (ps < .001), as well as being younger (p < .001), male (p = .038), and white (vs black or Asian, ps < .05). Acknowledging that e-cigarette use and advertising/media exposure are likely to be correlated, but the relationship potentially being bidirectional, we also modeled e-cigarette use without including e-cigarette advertising/media exposure; other findings did not change significantly.

Table 3.

Multilevel Regression Models Indicating Correlates of Past 30-day E-cigarette Use, Past 30-day E-cigarette Advertising/Media Exposure, and Past 30-day E-cigarette Users’ Reports of Age Verification at Point-of-Sale

| E-cigarette use | Advertising/media exposure | Infrequent age verification at point-of-sale in e-cigarette usersb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p |

| Intercept | 1.04 | 0.60, 1.79 | .893 | 3.55 | 2.20, 5.72 | < .001 | 0.08 | 0.04, 0.19 | < .001 |

| Sociodemographics | |||||||||

| Age | 0.93 | 0.91, 0.95 | < .001 | 0.98 | 0.96, 0.99 | .007 | 1.09 | 1.06, 1.13 | < .001 |

| Male (ref = female)a | 1.21 | 1.01, 1.45 | .038 | 1.03 | 0.87, 1.21 | .753 | 1.01 | 0.76, 1.35 | .927 |

| Sexual minority (ref = heterosexual) | 1.00 | 0.82, 1.21 | .971 | 1.12 | 0.93, 1.34 | .226 | 0.76 | 0.56, 1.03 | .081 |

| Race (ref = White) | |||||||||

| Black | 0.51 | 0.33, 0.81 | .004 | 0.76 | 0.53, 1.07 | .114 | 2.53 | 1.16, 5.50 | .019 |

| Asian | 0.57 | 0.42, 0.77 | < .001 | 0.83 | 0.65, 1.07 | .146 | 1.14 | 0.67, 1.93 | .641 |

| Other | 0.91 | 0.68, 1.22 | .518 | 1.27 | 0.96, 1.68 | .092 | 1.21 | 0.80, 1.83 | .365 |

| Hispanic (ref = non-Hispanic) | 1.13 | 0.85, 1.50 | .385 | 1.12 | 0.86, 1.46 | .413 | 1.13 | 0.75, 1.70 | .560 |

| Past 30-day ad/media exposure | 1.33 | 1.09, 1.62 | .004 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Past 30-day use | |||||||||

| E-cigarettes (ref = no) | -- | -- | -- | 1.30 | 1.07, 1.58 | .008 | -- | -- | -- |

| Cigarettes (ref = no) | 4.64 | 3.75, 5.73 | < .001 | 1.14 | 0.92, 1.41 | .222 | -- | -- | -- |

| Other tobacco products (ref = no) | 3.27 | 2.61, 4.09 | < .001 | 1.02 | 0.82, 1.27 | .878 | -- | -- | -- |

| Marijuana (ref = no) | 2.56 | 2.13, 3.09 | < .001 | 0.88 | 0.73, 1.05 | .162 | -- | -- | -- |

| Most common purchase location | |||||||||

| (ref = Gas station/convenience store) | |||||||||

| Online | -- | -- | -- | § | -- | -- | 1.57 | 1.00, 2.48 | .050 |

| Vape shop | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.23 | 0.83, 1.83 | .308 |

| Tobacco specialty shop | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .098 | 0.55, 1.77 | .957 |

Note.

ICCs for the null models for each outcome: past 30-day ENDS use = .020, advertising/media exposure = .003, and age verification = .011.

ICCs for the full models for each outcome: past 30-day ENDS use = .003, advertising/media = .004, and age verification = .001.

R2s for the null models for each outcome: past 30-day ENDS use = .020, advertising/media = .003, and age verification = .011.

R2s for the full models for each outcome: past 30-day ENDS use = .348, advertising/media = .023, and age verification = .089.

Those reporting “other” sex were excluded from these analyses.

Never, rarely or sometimes asked for age verification among past 30-day e-cigarette users who reported purchasing e-cigarettes (excluding “other” purchase locations) compared to those reporting almost always or often (referent), N = 903.

E-cigarette advertising/media exposure.

In bivariate analyses (Table 2), self-reported past 30-day e-cigarette advertising/media exposure was associated with being younger (p = .007), white (p = .009), born in the US (p = .015), and e-cigarette users (p < .001) and cigarettes (p = .022); it was also associated with most commonly purchasing e-cigarettes online (p = .050). Note also that bivariate analysis, not shown, indicated that those most commonly purchasing e-cigarettes online were the oldest on average; those most commonly purchasing at gas stations/convenience stores were the youngest (p = .001). In the multilevel binary regression model (Table 3), past 30-day e-cigarette advertising/media exposure was associated with being younger (p = .007) and e-cigarette use (p = .008). As noted above, to acknowledge the likely bi-directional association between e-cigarette use and e-cigarette advertising/media exposure, we also modeled advertising/media exposure: (1) among e-cigarette non-users only; other results remained similar; and (2) among past 30-day e-cigarette users only in which we also included common e-cigarette purchase location; this model indicated that the only statistically significant correlate of advertising/media exposure was purchasing e-cigarettes online (OR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.27, 3.60, p = .004).

Age verification.

In bivariate analyses (Table 2), frequency of age verification among past 30-day e-cigarette users was more likely to be reported as never/rarely/sometimes (vs often/almost always) among those who were older (p < .001), sexual minorities (p = .008), employed full-time (p = .014), married/living with a partner (p = .010), with children in the home (p = .003), cigarette users (p = .008), and marijuana users (p = .002), as well as those most commonly purchasing e-cigarettes online or in vape shops (vs in gas stations/convenience stores or tobacco specialty shops; p = .020). Note that those most commonly purchasing at gas stations/convenience and tobacco specialty shops were the most likely to report almost always/often being asked for age verification (59.0% and 58.3%, respectively), whereas those shopping online and at vape shops were less likely to report almost always/often being asked for age verification (43.7% and 52.4%, respectively; p = .020).

In the multilevel binary regression model (Table 3), predictors of infrequent (< often) age verification included older age (p < .001), being black (vs white, p = .019), and most commonly purchasing e-cigarettes online (vs at gas stations/convenience stores, p = .050). We also modeled this outcome restricting our sample to those under the age of 27; findings were similar.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we examined correlates of e-cigarette use, e-cigarette advertising/media exposure, and experiences of age verification upon e-cigarette purchase within this sample. Findings regarding age verification warrant particular attention. Approximately one-fourth of e-cigarette users indicated never or rarely being asked for age verification (even when restricting our sample to those under 27 years old), and only one-third reported almost always being asked for age verification. Moreover, reporting infrequent age verification was associated with most commonly purchasing e-cigarettes online (vs at gas stations/convenience stores) and being black. Note that reporting almost always/often being asked for age verification was more prominent among those most commonly purchasing at gas stations/convenience and tobacco specialty shops (~ 60%) versus online or at vape shops (43.7% and 52.4%, respectively). Consistent with self-reports from young adults in the current survey, prior research has documented similarly high rates of ID check failures with underage decoys (ages 18–20) at vape/smoke shops in California36 and to mystery shoppers (under age 27) at vape shops in the 6 MSAs.37 A limitation to this study is that we did not ask specifically if participants had a registered account for the website or retail venue where they made repeat purchases, which may have inflated the rates of noncompliance with age verification for online or retail sales. Regardless, the online retail and advertising environment poses among the greatest challenges in regulation enforcement.48,49 Our findings support previous literature and suggests that vape shops may, in fact, have higher violation rates than tobacco shops.

Results provide further support for the positive association between e-cigarette use and e-cigarette advertising/media exposure, as previous research demonstrates.26,27 Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot assume the direction of the relationship – that is, whether e-cigarette users are exposed to more advertising or if more advertising may lead to e-cigarette use. However, we conjecture that this association is bi-directional. In addition, e-cigarette users may be more likely to recall advertising exposure, given its greater potential relevance to e-cigarette users. Among past 30-day e-cigarette users, advertising/media exposure was associated with most commonly purchasing e-cigarettes online (vs at gas stations and/or convenience stores). These findings highlight concerns about advertising exposure among e-cigarette users and the potential reach of such advertising online, particularly drawing on the literature that indicates that exposure to tobacco advertising and access to tobacco retail may undermine quit attempts.50,51

Also note that e-cigarette advertising/media exposure was reported by the majority of both non-users (66.0%) and that advertising/media exposure also was associated with being younger, albeit the average difference between those exposed versus not exposed was 0.5 years (and a wide confidence interval). Nonetheless, this highlights related ongoing concerns about youth e-cigarette use and initiation, as recent regulations and legislation aim to curb the epidemic.29,30,32,52

Consistent with national data, past 30-day e-cigarette use was associated with being younger, male, and white,53 as well as use of cigarettes, other tobacco products, and marijuana.40,41 Despite the sampling strategy not intentionally targeting marijuana users, this sample included more marijuana users than e-cigarette or cigarette users, which is not surprising given the: (1) high prevalence of young adult marijuana use in general (22.1% in 2018) versus e-cigarettes (7%) and cigarettes (19.1%);54,55 and (2) high rates of co-use of e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and marijuana.40,41

This study has limited generalizability to other young adults in the included MSAs or across the US more broadly. Notably, the use prevalence in this sample (37.7%, 26.9%, and 39.2% for e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and marijuana respectively) should not be interpreted as estimates of use in these MSAs, as our sampling design aimed to achieve a sample with approximately one-third being past 30-day e-cigarette users and cigarette users, respectively. Similarly, the rates of e-cigarette advertising/media exposure across the sample should be interpreted cautiously, and more appropriately, be examined as the proportions of e-cigarette users and nonusers exposed, respectively. Age verification frequency was asked only among e-cigarette users, but should nonetheless be interpreted cautiously, as our sample may be more representative of those who purchase cigarettes more commonly online or in vape shops, given our recruitment strategy (eg, social media, targeting people following/liking e-cigarette vendors with social media pages). One also should note that the subsamples recruited across MSAs were different with regard to sociodemographic profiles and tobacco/marijuana use profiles, as well as differences in the broader tobacco control environments and marijuana legislation across MSAs. However, the ICCs across all multilevel models were low, indicating that MSAs accounted for little effect on the outcomes in this study.42–44 Other limitations include the use of self-report assessments (and potential for biased reports) and the cross-sectional nature of these analyses (which precludes determining the directionality of the associations documented). However, this initial analysis of our sample is designed to set a foundation for all other papers produced from this study, which will leverage the longitudinal data and be able to address causal associations, conduct other more sophisticated analyses, and capture potential natural experiments.

Current findings have implications for research and practice. Research is needed to assess age verification practices among brick-and-mortar and online retailers using a variety of methods (eg, mystery shoppers, observational studies) to improve estimated rates of noncompliance and to take into account factors not accounted for in this study (eg, online retail accounts). Establishing differential rates between store types is important, as more localities consider restricting sales to specialty tobacco shops with higher rates of ID check failures and underage sales violations. Advanced methods to assess (or manipulate) retail, advertising, and media exposures in the context of longitudinal surveys (and controlled experiments) are needed to determine the directionality and magnitudes of associations on behavioral outcomes (eg, e-cigarette initiation, continued use, cessation). In practice, additional surveillance and enforcement efforts are needed to address underage access to tobacco products, and ultimately, youth use prevention; for example, California’s Stop Tobacco Access to Kids Enforcement (STAKE) program assists local law enforcement agencies by providing grants and tobacco enforcement training.

Conclusion

Our findings reaffirm the literature indicating high exposure to e-cigarette advertising/media among young adult users and non-users. Given that young adults’ experience with e-cigarette retail and advertising likely has reciprocal effects on their use, such environmental exposures must be addressed. Moreover, persons in this sample indicated experiencing poor compliance among e-cigarette vendors with regard to age verification, particularly online and in vape shops. Unfortunately, the online retail and advertising environment poses among the greatest challenges in regulation enforcement.48,49

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS FOR TOBACCO REGULATION.

Findings indicate: (1) high e-cigarette advertising/media exposure among young adults; (2) poor retailer compliance with regard to age verification for e-cigarette purchase; and (3) online vendors and vape shops are 2 prominent sources of advertising exposure and potential underage access to e-cigarettes. Thus, surveillance is critical in ensuring compliance with regulations, particularly those related to advertising/media exposure and access among young people. The online retail and advertising environment poses among the greatest challenges in regulation enforcement, underscoring the need to advance methods for surveillance in this context.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by the US National Cancer Institute (R01CA215155-01A1; PI: Berg). Dr. Berg is also supported by other US National Cancer Institute funding (R01CA179422-01; PI: Berg; R01CA239178-01A1; MPIs: Berg, Levine), the US National Institutes of Health/Fogarty International Center (1R01TW010664-01; MPIs: Berg, Kegler), and the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/Fogarty International Center (D43ES030927-01; MPIs: Berg, Marsit, Sturua). Dr. Pulvers is supported by funding from the US National Institutes of Health (SC3GM122628; PI: Pulvers; R01 CA190347; MPIs: Strong and Pierce), the California Tobacco Related Disparities Research Program (27IP-0041; PI: Pulvers; 28IP-0022S; PI: Oren), and the US Department of Health and Human Services (3GM1226290FK0105-01-00; PI: Fernando Sañudo). Dr. Sussman’s research activities are supported by a California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program Award (TRDRP Grant #26IR-0016) and a National Cancer Institute and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) Award (NCI/FDA Grant #U54CA180905). Dr. Ma is supported by funding from the US National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD013901; PI: Ma). Dr. Henriksen is supported by other NCI funding (5R01CA067850-17; PI: Henriksen; 1R01CA217165; PI: Henriksen; 1P01CA0225597; MPI: Henriksen, Luke, Ribisl).

Footnotes

Human Subjects Approval Statement

This study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB00097895).

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Contributor Information

Carla J Berg, Department of Prevention and Community Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States..

Xuejing Duan, Biostatistics and Epidemiology Consulting Service, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington, DC, United States..

Betelihem Getachew, Department of Behavioral, Social and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States..

Kim Pulvers, Department of Psychology, California State University San Marcos, San Marcos, CA, United States..

Natalie D. Crawford, Department of Behavioral, Social and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States..

Steve Sussman, Departments of Preventive Medicine and Psychology, and School of Social Work, University of Southern California, Alhambra, CA, United States..

Yan Ma, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Milken Institute School of Public Health, Washington, DC, United States..

Carla Jones-Harrell, Department of Behavioral, Social and Health Education Sciences, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States..

Lisa Henriksen, Stanford Prevention Research Center, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, United States..

References

- 1.Kennedy RD, Awopegba A, De Leon E, Cohen JE. Global approaches to regulating electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(2):116–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malas M, van der Tempel J, Schwartz R, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(10):1926–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Bullen C, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016(9):CD010216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-cigarettes National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Available at: http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/reports/2018/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes.aspx. Published 2018. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 6.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. Published 2012. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 8.Hanewinkel R, Isensee B, Sargent JD, Morgenstern M. Cigarette advertising and adolescent smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(10):CD003439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ringold DJ, Weitz B. The American Marketing Association definition of marketing: moving from lagging to leading indicator. J Public Policy Mark. 2007;26(2):251–260. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilpin EA, White MM, Messer K, Pierce JP. Receptivity to tobacco advertising and promotions among young adolescents as a predictor of established smoking in young adulthood. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1489–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton S, Clark L, Jackson K. The association between seeing retail displays of tobacco and tobacco smoking and purchase: findings from a diary-style survey. Addiction. 2012;107(1):169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Truth Initiative. E-cigarettes: Facts, Stats and Regulations. Washington, DC: The Truth Initiative; 2019. https://www.truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/e-cigarettes-facts-stats-and-regulations. Published 2019. Accessed April 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribisl K, D’Angelo H, Feld AL, et al. Disparities in tobacco marketing and product availability at the point of sale: results of a national study. Prev Med. 2017;105:381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schleicher NC, Johnson T, Rigdon J, et al. California Tobacco Retail Surveillance Study, 2017. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Public Health; 2017. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/DCDIC/CTCB/CDPH%20Document%20Library/Research-andEvaluation/SurveyInstrumentsTrainingManualsAndProtocols/CaliforniaTobaccoRetailSurveillanceStudt2017-CTRSS%206-4.pdf. Published December 22, 2017. Accessed December 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YO, Kim AE. ‘Vape shops’ and ‘E-Cigarette lounges’ open across the USA to promote ENDS. Tob Control. 2014;24(4):410–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong AY, Eaddy JL, Morrison SL, et al. Using the Vape Shop Standardized Tobacco Assessment for Retail Settings (V-STARS) to assess product availability, price promotions, and messaging in New Hampshire vape shop retailers. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(2):174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovenco DP. Smoke shop misclassification may cloud studies on vape shop density. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(8):1025–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheney M, Gowin M, Wann TF. Marketing practices of vapor store owners. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):e16–e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marynak K, Gentzke A, Wang TW, et al. Exposure to electronic cigarette advertising among middle and high school students – United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(10):294–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg CJ. Preferred flavors and reasons for e-cigarette use and discontinued use among never, current, and former smokers. Int J Public Health. 2016;61(2):225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Getachew B, Payne J, Vu M, et al. Perceptions of alternative tobacco products, anti-tobacco media, and tobacco regulation among young adults: a qualitative study. Am J Health Behav. 2018;42(4):118–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JGL, Orlan EN, Sewell KB, Ribisl KM. A new form of nicotine retailers: a systematic review of the sales and marketing practices of vape shops. Tob Control. 2018;27(e1):e70–e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berg CJ, Escoffery C, Bundy L, et al. Cigarette users interest in using or switching to electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) or smokeless tobacco for harm reduction, cessation, or novelty. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Fagan P, et al. E-cigarette advertising exposure, explicit and implicit harm perceptions, and e-cigarette use susceptibility among nonsmoking young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(1):127–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen-Sankey JC, Unger JB, Bansal-Travers M, et al. E-cigarette marketing exposure and subsequent experimentation among youth and young adults. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20191119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Food and Drug Administration. Tobacco Products: Vaporizers, E-Cigarettes, and other Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS). https://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/labeling/productsingredientscomponents/ucm456610.htm. Published 2019. Accessed May 1, 2020.

- 29.Vazquez M, Klein B. Trump administration moves to ban flavored e-cigarettes. https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/11/politics/donald-trump-vape-e-cigarette-flavors/index.html. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 30.Public Health Law Center. U.S. E-Cigarette Regulations – 50 State Review (2019). Public Health Law Center. https://publichealthlawcenter.org/resources/us-e-cigarette-regulations-50-state-review.m Published 2019. Accessed May 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Public Health Law Center. Commercial Tobacco and Marijuana. https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/commercial-tobacco-control/commercial-tobacco-and-marijuana. Published 2020. Accessed May 1, 2020.

- 32.American Lung Association. State of Tobacco Control, 2018. Chicago, IL: American Lung Association; 2018. https://www.bhthechange.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/state-of-tobacco-control.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed May 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, et al. Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003–2012. Addict Behav. 2015;49:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schauer GL, King BA, Bunnell RE, et al. Toking, vaping, and eating for health or fun: marijuana use patterns in adults, U.S., 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navon L, Jones CM, Ghinai I, et al. Risk factors for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) among adults who use e-cigarette, or vaping, products – Illinois, July-October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roeseler A, Vuong TD, Henriksen L, Zhang X. Assessment of underage sales violations in tobacco stores and vape shops. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(8):795–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berg CJ, Barker DC, Meyers C, et al. Exploring the point-of-sale among vape shops across the US: audits integrating a mystery shopper approach. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020. February 28;ntaa041. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams RS, Derrick J, Liebman AK, et al. Content analysis of age verification, purchase and delivery methods of internet e-cigarette vendors, 2013 and 2014. Tob Control. 2018;27(3):287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Census Bureau. 2018. National and State Population Estimates. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2018/pop-estimates-national-state.html. Published December 19, 2018. Accessed December 21, 2020.

- 40.Buu A, Hu YH, Wong SW, Lin HC. Comparing American college and noncollege young adults on e-cigarette use patterns including polysubstance use and reasons for using e-cigarettes. J Am Coll Health. 2020;68(6):610–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bluestein M, Kelder S, Perry CL, Perez A. Exploring associations between the use of alcohol and marijuana with e-cigarette use in a U.S.A. nationally representative sample of young adults. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2019;13(1):30–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aveyard P, Markham WA, Cheng KK. A methodological and substantive review of the evidence that schools cause pupils to smoke. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2253–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aveyard P, Markham WA, Lancashire E, et al. The influence of school culture on smoking among pupils. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(9):1767–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bovaird JA, Shaw LH. Multilevel structural equation modeling. In Laursen B, Little TD, Card NA, eds. Hand-book of Developmental Research Methods. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012:501–518. [Google Scholar]

- 45.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2019. https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/release-notes-ibm%C2%AE-spss%C2%AE-statistics-260. Published April 9, 2019. Accessed December 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hornik K. The R FAQ: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Indianapolis, IN: The R Foundation; 2020. https://www.r-project.org/. Published 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berg CJ, Schleicher N, Johnson T, et al. Vape shop identification, density and place characteristics in six metropolitan areas across the US. Prev Med Rep. 2020;19:101137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams RS, Derrick J, Ribisl KM. Electronic cigarette sales to minors via the internet. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(3):e1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguyen H, Dennehy CE, Tsourounis C. Violation of US regulations regarding online marketing and sale of e-cigarettes: FDA warnings and retailer responses. Tob Control. 2020;29(e1):e4–e9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pulakka A, Halonen JI, Kawachi I, et al. Association between distance from home to tobacco outlet and smoking cessation and relapse. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1512–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoek J, Gifford H, Pirikahu G, et al. How do tobacco retail displays affect cessation attempts? Findings from a qualitative study. Tob Control. 2010;19(4):334–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA, FTC take action against companies misleading kids with e-liquids that resemble children’s juice boxes, candies and cookies. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-ftc-take-action-against-companies-misleading-kids-eliquids-resemble-childrens-juice-boxes. Published 2018. Accessed April 2, 2020.

- 53.Vallone DM, Cuccia AF, Briggs J, et al. Electronic cigarette and JUUL use among adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(3):277–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, SAMHSA; 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29393/2019NSDUHFFRPDFWHTML/2019NSDUHFFR1PDFW090120.pdf. Published September 2020. Accessed December 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dai H, Leventhal AM. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014–2018. JAMA. 2019;322(18):1824–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.