This is an executive summary of the update of the 2002 and 2007 American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM) hemodynamic support guidelines for pediatric and newborn septic shock.

THE PATIENT POPULATION, INTERVENTION OF INTEREST, COMPARATOR, AND OUTCOMES OF INTEREST QUESTION ADDRESSED: IS THERE NEW INFORMATION SUPPORTING CHANGING THE 2007 RECOMMENDATIONS?

Since 2007, there has been a major effort in the United States to test the first-hour recommendations in pediatric academic centers in the American Academy of Pediatrics collaborative Septic Shock consortium which is dedicated to quality improvement in septic shock recognition and treatment. There have been four studies conducted in tertiary pediatric emergency departments that have examined adherence to ACCM/Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) guidelines for sepsis resuscitation in the first hour (1–4). Together, these studies demonstrated incomplete adherence to recommended goals for administration of IV fluids, antibiotics, and vasoactive agents. Subsequent quality-directed efforts from these studies showed improvement in both process metrics (e.g., decreased time to administration of IV fluids, antibiotics, and peripheral vasoactive agents) and outcome metrics, including hospital and PICU length of stay and mortality. Importantly, all quality improvement studies were predicated on rapid identification of patients with suspected septic shock to trigger rapid clinician evaluation and implementation of appropriate resuscitation efforts. Multiple elements have been incorporated into trigger tools with success by several institutions (5, 6); however, there has been notable variation in the algorithms used at each institution, and none have sufficient evidence to fully endorse as a specific tool. Given the complexity of resource allocation and implementation, it appears reasonable that each institution could locally develop their trigger tool while further studies refine the derivation and validation of an optimally sensitive and specific sepsis trigger tool.

From the best practice model standpoint, Paul et al (4) implemented a hospital-wide quality improvement initiative to improve compliance with all five elements of the ACCM/PALS guidelines first-hour recommendations: 1) recognition, 2) establishing IV access, 3) starting IV fluids and resuscitation as needed, 4) administering antibiotics, and 5) starting vasoactive agents if needed. Achievement of 100% compliance required a number of human interaction interventions including use of time clocks set to have time going from 0 to 60 minutes rather than from 60 to 0 minutes, that resulted in an increase in number of cases between death occurrences (p < 0.05) with an overall reduction in hospital mortality from 4.0% to 1.7%.

Han et al (7) analyzed the international Global Sepsis Initiative database which included children from “resource-rich” settings in Europe, North America, and South America in order to derive “three-element” bundles associated with improved outcomes. The first-hour/emergency department three-element bundle included 1) reversal of shock defined by normal blood pressure and capillary refill less than 3 seconds, 2) provision of antibiotics, and 3) provision of Dextrose 10 g/dL and sodium containing IV fluid infusion. The stabilization /PICU three-element bundle included 1) reversal of shock defined by maintaining normal mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus central venous pressure (CVP) (MAP – CVP) for age as means to measure perfusion pressure and central venous oxygen saturation at right atrial/vena cava junction level (Scvo2) greater than 70%, 2) timely provision of the appropriate antibiotic to which the organism is sensitive and source control, and 3) maintenance of effective tidal volumes between 6 and 8 mL/kg in children mechanically ventilated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Reversal of shock was associated with use of the 2007 ACCM/PALS guidelines in both the resuscitation and stabilization bundles.

Ventura et al (8) demonstrated that resuscitation of fluid refractory septic shock with peripheral epinephrine infusion, until central access was attained, reduced mortality from 20% to 7% compared with peripheral dopamine. Use of peripheral epinephrine was associated with maintenance of higher blood pressures and fewer episodes of nosocomial infection compared with dopamine.

KEY NEW RECOMMENDATIONS

The major new recommendation in the current update is that hemodynamic support of septic shock now be addressed at the institutional level and at the caregiver level.

BUNDLES IN NEW ACCM GUIDELINES

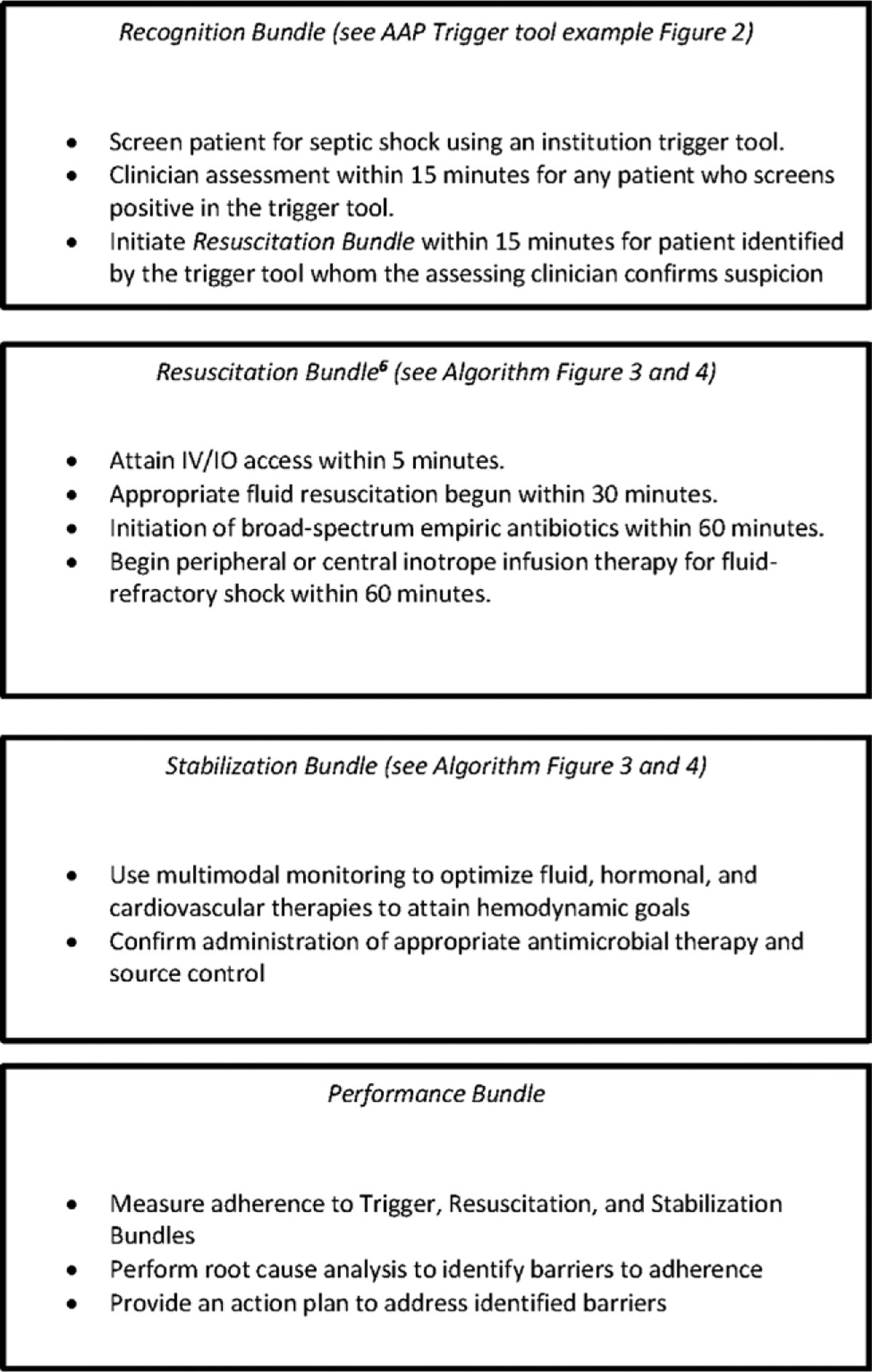

The new guidelines recommend that each institution implement their own adopted or home-grown bundles that include the following:

“Recognition bundle” containing a trigger tool for rapid identification of patients with suspected septic shock at that institution,

“resuscitation and stabilization bundle” to drive adherence to consensus best practice at that institution, and

“performance bundle” to monitor, improve, and sustain adherence to that best practice and to identify and overcome perceived barriers to the pursuit of best practice principles.

The new guidelines provide examples of each bundle (Fig. 1) for consideration and review by each hospital’s expert committee.

Figure 1.

Example of recognition, resuscitation, stabilization, and performance bundles. IO = intraosseous line.

We recommend that each institution develop a “recognition bundle” to optimize identification of patients at risk for septic shock that is based on vital sign abnormalities and high-risk criteria.

The “recognition bundle” should contain the following:

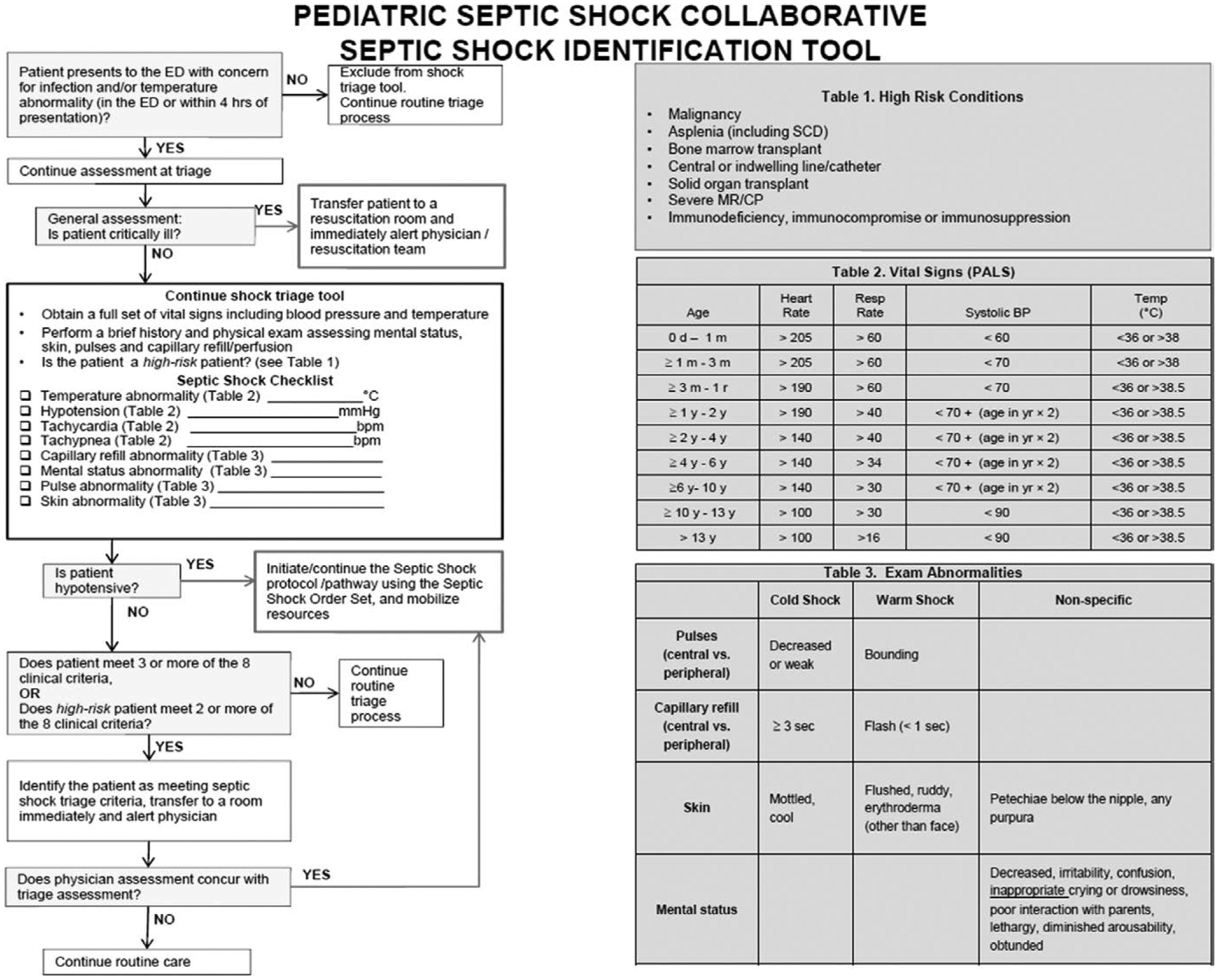

A trigger tool (example given in Fig. 2) for rapid identification of patients with suspected septic shock. Elements that are recommended for use in a trigger tool include vital signs, physical examination, and at-risk populations.

Rapid clinician assessment within 15 minutes for any patient that is identified by the trigger tool.

Activation of a sepsis “resuscitation bundle” within 15 minutes for patients with suspected septic shock.

Figure 2.

American Academy of Pediatrics trigger tool for early septic shock recognition. BP = blood pressure, CP = cerebral palsy, ED = emergency department, PALS = Pediatric Advanced Life Support, SCD = sickle cell disease.

We recommend that each institution also develop or adopt a first-hour “resuscitation and stabilization bundle” to optimize time to completion of first hour and stabilization tasks when a patient with suspected septic shock is identified. The resuscitation bundle is done to drive adherence to consensus best practice.

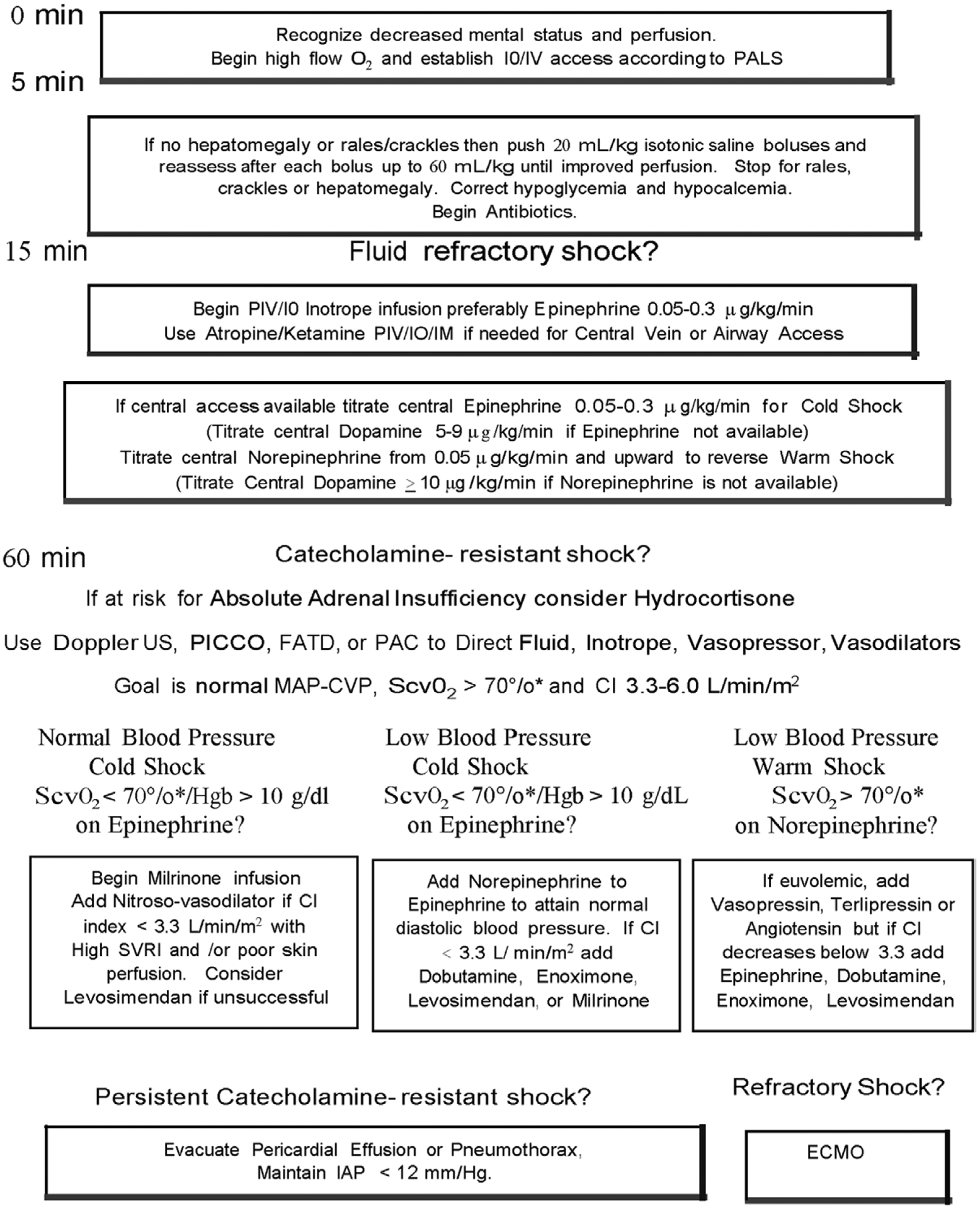

The resuscitation bundle (examples in Figs. 3 and 4) may contain the following:

Intraosseous line or IV access within 5 minutes of diagnosis.

Appropriate fluid resuscitation initiated within 30 minutes of diagnosis.

Initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics within 60 minutes of diagnosis.

Blood culture if it does not delay antibiotic administration.

Appropriate use of peripheral or central inotrope within 60 minutes of diagnosis.

Figure 3.

American College of Critical Care Medicine algorithm for time sensitive, goal-directed stepwise management of hemodynamic support in infants and children during resuscitation and stabilization. Proceed to next step if shock persists. 1) First-hour goals—restore and maintain heart rate thresholds, capillary refill less than or equal to 2 s, and normal blood pressure in the first hour/emergency department. 2) Subsequent ICU goals—if shock not reversed, proceed to restore and maintain normal perfusion pressure (mean arterial pressure [MAP] minus central venous pressure [CVP]) for age, central venous oxygen saturation at right atrial/vena cava junction level (Scvo2) greater than 70% (*except congenital heart patients with mixing lesions for whom this is too high), and cardiac index (CI) > 3.3 < 6.0 L/min/m2 in PICU. ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenator, FATD = femoral artery thermodilution catheter, Hgb = hemoglobin, IM = intramuscular, IO = intraosseous line, PAC = pulmonary artery catheter, PALS = Pediatric Advanced Life Support, PICCO = pulse index contour cardiac output catheter, PIV = peripheral IV line, SVRI = systemic vascular resistance index, US = ultrasound.

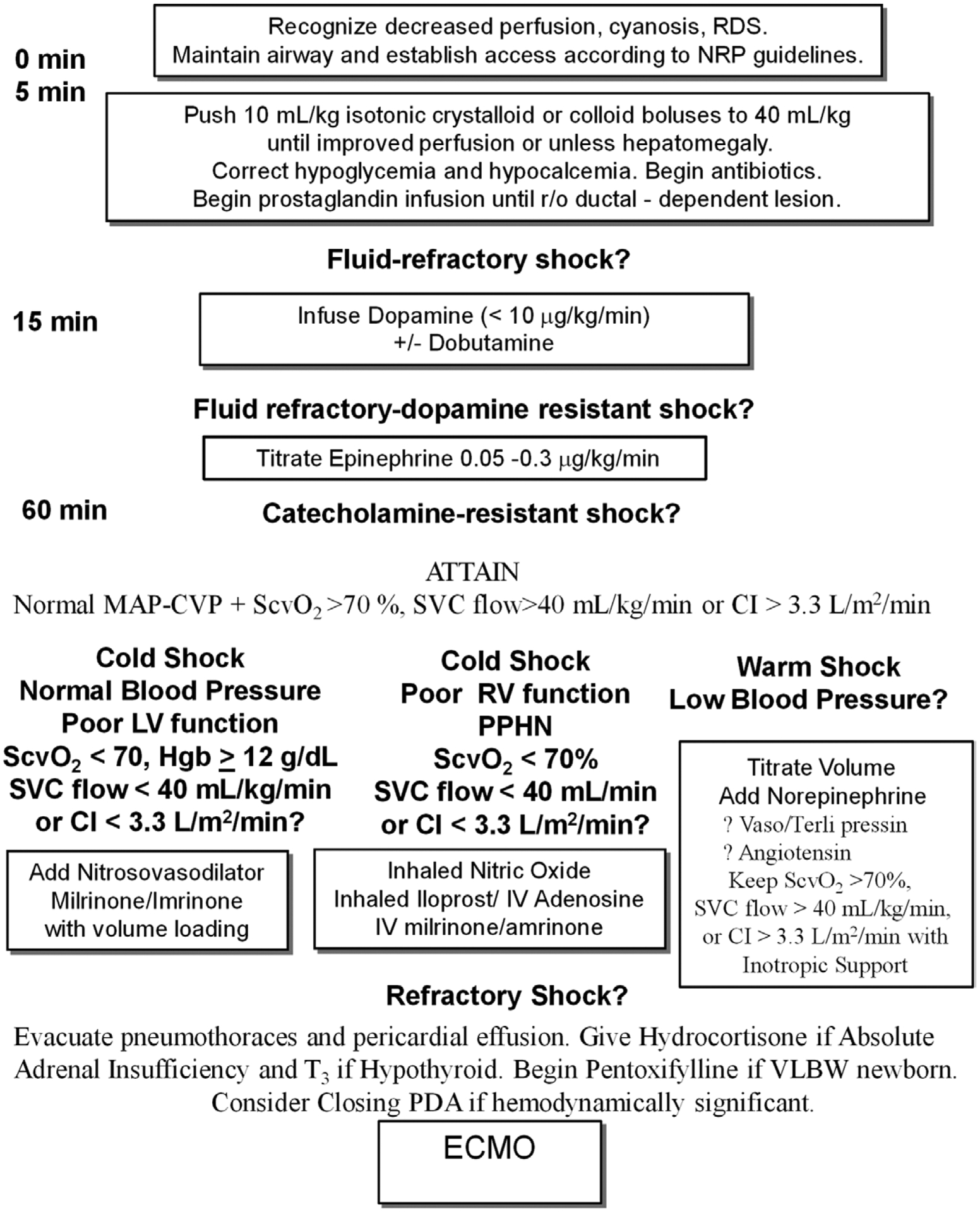

Figure 4.

American College of Critical Care Medicine Algorithm for time sensitive, goal-directed stepwise management of hemodynamic support in newborns during resuscitation and stabilization. Proceed to next step if shock persists. 1) First-hour goals—restore and maintain heart rate thresholds, capillary refill less than or equal to 2 s, and normal blood pressure in the (first hour) and 2) subsequent ICU goals—restore normal perfusion pressure (mean arterial pressure [MAP] minus central venous pressure [CVP]), pre- and postductal oxygen saturation difference less than 5%, and either central venous oxygen saturation at right atrial/vena cava junction level (Scvo2) greater than 70% (*except in congenital heart patients with mixing lesions), superior vena cava (SVC) flow greater than 40 mL/kg/min or cardiac index (CI) greater than 3.3 L/min/m2 in NICU. ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenator, LV = left ventricle, NICU = neonatal ICU, NRP = neonatal resuscitation program, PDA = patent ductus arteriosus, PPHN = persistent pulmonary hypertension, RDS = respiratory distress syndrome, RV = right ventricle, T3 = tri-iodothyronine, VLBW = very low birth weight.

The stabilization bundle (examples in Figs. 3 and 4) may contain the following:

Multimodal monitoring to guide fluid, hormonal, and cardiovascular therapies to attain a normal MAP – CVP for age (55 + 1.5 × age in yr) as a measure of adequate perfusion pressure, Scvo2 greater than 70% and/or cardiac index 3.3–6.0 L/min/m2.

Administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy and source control.

We recommend that each institution develop or adopt a “performance bundle” to identify barriers to attaining the recognition, resuscitation, and stabilization bundle goals.

The “performance bundle” should contain the following:

Measurement of adherence and achievement of goals and individual components.

Ways to monitor, improve, and sustain adherence to best practice.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Davis served as an expert witness regarding a patient who herniated post-operatively. Dr. Aneja received funding from UpToDate royalties. Dr. Relvas participates in AAP PrepICU (editorial board member). Dr. Williams participates in American Academy of Pediatrics (guidelines committee work). Dr. Yeh participates in American Academy of Pediatrics (guidelines committee work). Dr. Brierley received funding from Astellas Pharmaceuticals Speakers Bureau (regarding antifungals in the ICU). He participates as a member in the American Academy of Pediatrics, Academic Pediatric Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Dr. de Caen participates in the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and the American Heart Association. Dr. Cheifetz received funding from Philips (medical advisor) and Ikaria (medical advisor). He participates in various volunteer activities for AARC and ATS, and he has served as an expert witness for testimony for medical malpractice cases. Dr. Choong participates as an Executive Member of the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and is an employee of the Hamilton Health Sciences. Dr. Conway participates as Chair of Section on Pediatric Critical Care Medicine for the AAP. He has served as an expert witness for pediatric Critical Care Medicine/ED defense cases. Dr. Cornwell received grant funding from the Coulter Foundation. He participates in the Society of Pediatric Research. Dr. Doctor received funding from consulting for Novartis, Galera Pharmaceuticals, and Terumo BCT. Dr. Fortenberry participates in AAP, Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. He served as an expert witness for review of PICU cases and testimony in support of physicians providing PICU care. Dr. Greenwald served as an expert witness for testimony regarding course of illness and risk of mortality. Dr. Hall serves as the Editor for the ATS Online Journal Club. Dr. Irazuzta participates in the National Institutes of Health. Dr. van der Jagt received grant funding from University of Rochester (employee/faculty). She participates in NYS Emergency Medical Services for Children Advisory Committee (Vice-Chair), University of Rochester School of Medicine (faculty), AHA Pediatric Advanced Life Support Advanced Life Support Writing Group (member), IPSO National Expert Advisory Committee (member), FAAP, Sr. Fellow Society of Hospital Medicine, and Fellow College of Pediatricians. Dr. Jeffries participates in AAP, Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Society, and ACC. Dr. Kache participates on the Global health Educators Committee In Association of Pediatric Program Directors and on the Global Health Education Subcomittee in Consortium of Universities for Global Health. Dr. Kon participates as the President-elect for the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. He disclosed that he is a government employee. He has served as an expert witness for pediatric critical care and bioethics. Dr. Maclaren received funding from UpToDate (royalties). He participates in the Asia-pacific Chapter of ELSO (Chair) and the Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Society (Vice President). Dr. Maul received funding from consulting for Mallinkrodt, Thoratec, and Alung. He received grant funding. He participates in ASAIO (editor) and ELSO (committee member). Dr. Odetola participates as a member of the Sub-Board of Critical Care Medicine, American Board of Pediatrics. Dr. Parbuoni participates in the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and California Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Dr. Reuter-Rice received funding from J & B Learning (textbook royalties). She received grant funding from RWJK. She participates in PNCB- IPN, AAN, and ISONG. Dr. Schnitzler participates in Sociedad Argentina de Terapia Intensiva, Sociedad Argentina de Calidad en Asistencia Sanitaria, and Instituto Técnico de Acreditación de Establecimientos Sanitarios. Dr. Torres received funding from Abbott Point of Care (speaker). He served as an expert witness for the defense paid for his time. Dr. Weiss received funding from honoraria to grand rounds lectures from Thermo Fisher Scientific (but content of lecture was solely his own responsibility). He participates in AAP and Shock Society. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

The American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM), which honors individuals for their achievements and contributions to multidisciplinary critical care medicine, is the consultative body of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) that possesses recognized expertise in the practice of critical care. The College has developed administrative guidelines and clinical practice parameters for the critical care practitioner. New guidelines and practice parameters are continually developed, and current ones are systematically reviewed and revised.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cruz AT, Perry AM, Williams EA, et al. : Implementation of goal-directed therapy for children with suspected sepsis in the emergency department. Pediatrics 2011; 127:e758–e766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsen GY, Mecham N, Greenberg R: An emergency department septic shock protocol and care guideline for children initiated at triage. Pediatrics 2011; 127:e1585–e1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul R, Neuman MI, Monuteaux MC, et al. : Adherence to PALS sepsis guidelines and hospital length of stay. Pediatrics 2012; 130:e273–e280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul R, Melendez E, Stack A, et al. : Improving adherence to PALS septic shock guidelines. Pediatrics 2014; 133:e1358–e1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz AT, Williams EA, Graf JM, et al. : Test characteristics of an automated age- and temperature-adjusted tachycardia alert in pediatric septic shock. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012; 28:889–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sepanski RJ, Godambe SA, Mangum CD, et al. : Designing a pediatric severe sepsis screening tool. Front Pediatr 2014; 2:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han Y, Carcillo J, Espinosz V, et al. ; Vanguard Centers of Global Pediatric Sepsis Initiative: Quality improvement analysis of the global pediatric sepsis initiative registry: Simplified clinical bundle recommendations for industrialized developing and developed nation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014; 15:15–1624389709 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ventura AM, Shieh HH, Bousso A, et al. : Double-blind prospective randomized controlled trial of dopamine versus epinephrine as first-line vasoactive drugs in pediatric septic shock. Crit Care Med 2015; 43:2292–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]