Abstract

Context:

Healthcare workers (HCWs) face a potential risk of acquiring different bloodborne pathogens, by occupational exposure to contaminated blood and body fluids. Hepatitis B vaccine is a safe, effective method of conferring long-term protection against HBV infection.

Aims:

The study aimed to assess the adherence and effectiveness of HBV vaccination among HCWs at Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt.

Settings and Design:

A prospective descriptive study was carried out between June 2019 and December 2019 at Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt.

Methods and Material:

All HCWs with anti-HBs levels below 10 mIU/mL were advised to receive 3 doses of recombinant HBV vaccine, at 0, 1, and 6 months. The anti-HBs levels were checked 3 months after the third dose of the HBV vaccine.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS) program for windows (version 16).

Results:

A total of 442 healthcare providers were included. Most of them completed the 3 doses of the vaccine (81.7%), 10.2% refused the vaccine, while 0.9% and 7.2% received 1 and 2 doses, respectively. Odds of vaccination were the highest (88.1%, 273/310) among nurses (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2.6–5.2; P ≤ 0.001). The overall anti-HBs positivity of 97% (350/361) was observed. The main reasons for not being vaccinated included the fear of vaccine side effects 25/81 (30.9%) and lack of trust in the vaccine effectiveness 18/81 (22.2%).

Conclusions:

The outcome of the present study emphasizes the need to apply alternative and innovative measures to build a positive attitude toward the HBV vaccine among HCWs.

Keywords: Blood-borne pathogens, health personnel, hepatitis B vaccines, hepatitis B virus

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a public health problem worldwide with over 350 million carriers globally. Egypt is a region of intermediate prevalence for HBV infection with prevalence rate ranges from 3 to 11%.[1] Long-term complications include chronic active hepatitis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and cirrhosis.[2] Hepatitis B vaccine is the mainstay in the prevention of HBV infection. It is a safe, effective, and well-established method of conferring long-term protection against HBV infection.[3]

Healthcare workers (HCWs) (physicians, nurses, and technicians) face a potential risk of acquiring different bloodborne pathogens, particularly hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV/HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), by occupational exposure to contaminated blood and body fluids while taking care of their patients.[4,5] These occupational exposures could be through needle stick injuries or accidental splashing of blood and body fluids, leading to contact with mucous membranes.[6]

In Egypt, Mass Vaccination Program against HBV was initiated in 1992 with a compulsory schedule at 2, 4, and 6 months of age, therefore many HCWs at our hospital haven't received any previous vaccination.[7]

Due to the scarcity of the studies about HBV vaccination among HCWs as well as the lack of studies assessing the response, we found it valuable to conduct this study. The HBV vaccine was provided by the hospital free of cost to all the HCWs. The vaccine schedule was given to the HCWs to get the vaccine issued from the pharmacy department and administered by the injection room staff in the outpatient department of the hospital. Brochures were issued to all categories of HCWs, highlighting the importance, necessity, and availability of HBV vaccine.

AIM OF WORK

The study aimed to assess the adherence and effectiveness of HBV vaccination among HCWs at Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt.

Type of the study

A prospective descriptive study was carried out between June 2019 and December 2019 at Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt.

Study setting

Gastrointestinal Surgical Center of Mansoura is a 170-bed teaching hospital serving as a tertiary care surgical center. An infection control team with full-time nurses was maintained in our hospital. The team also acts as an advisory body to the medical staff, analyzing the epidemiology of the infections, improving the appropriate use of antimicrobials and provides adequate training for HCWs.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

Only those HCWs with anti-HBs levels less than 10 mIU/mL who were involved in direct patient care (physicians, nurses, and technicians), carried out invasive procedures, and, consequently, liable to come in contact with blood and body fluids were enrolled for the study. The HCWs who do not come in direct contact with the patient were excluded from the study.

Study population

Of the total of 442 HCWs who participated in the study, 75 (17%) were physicians, 310 (70.1%) were nurses, and 57 (12.9%) were technicians. The physicians belonged to the category of consultants working in various subspecialties of the hospital. The technicians belonged to the specialties of operating room, endoscopy, radiology, and laboratory.

Demographic data of all participants, vaccination history, and attitude toward vaccination including the reasons for taking/not taking the vaccine were assessed using a questionnaire prepared by the infection control department, completed and administered by each participant for data analysis.

Operational definitions

Adherence which is “the extent to which a health care provider corresponds with agreed vaccination recommendations.” Completeness of all 3 doses is a measure of adherence. Anti-HBs titre is used to evaluate the effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccine and titres of >10 mIU/ml which is considered protective.[7,8]

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

All HCWs with anti-HBs levels below 10 mIU/mL were advised to receive 3 doses of yeast-derived recombinant HBV vaccine, GeneVac-B (Serum institute, India) at 0, 1, and 6 months of 1 mL (20 mg/mL) intramuscularly (in the deltoid muscle) each. The anti-HBs levels were checked 3 months after the third dose of the HBV vaccine.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS) program for windows (version 16). Quantitative data were presented in mean and standard deviation (SD). Chi-square or Fisher Exact test was used for testing the significance of categorical data; as appropriate. Crude OR and their 95% CI were calculated.

Forward Waled logistic regression analysis was used to assess the effect of independent factors on outcome rates and adjusted odds ratio and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated, P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

Informed consents were obtained from all participants. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mansoura University, Egypt. The final approval from the ethics committee ( Institutional review board) was obtained on 29th June 2020. Code: R.20.06.889.

RESULTS

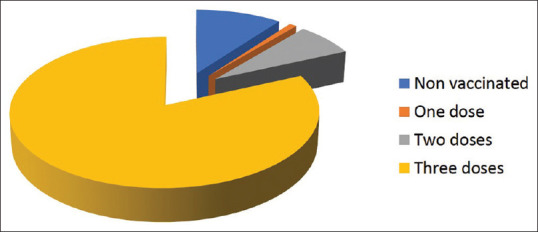

A total of 442 health care providers (HCP) were included in the study. Their age ranged from 24 to 58 with a mean of 30.9 (±6.4). The majority of them completed the 3 doses of the vaccine (81.7%), 10.2% refused the vaccine, while 0.9% and 7.2% received 1 and 2 doses, respectively [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of vaccination among healthcare workers

Immunization with the full series (3 doses) of HBV vaccine was significantly higher among female participants than among male participants (258 [86.9%] of 297 females vs. 103 [71%] of 145 males; P = ≤0.001) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with compliance

| Total | Compliant n (%) | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 442 | 361 (81.7) | ||

| Age (years): | ||||

| <30 | 244 | 207 (84.8) | 1 (r) | |

| 30 & more | 198 | 154 (77.8) | 0.8 (0.4-1.0) | |

| Sex: | ||||

| Male | 145 | 103 (71.0) | 1 (r) | |

| Female | 297 | 258 (86.9) | 2.7 (1.7-4.4)*** | |

| Job: | ||||

| Doctors | 75 | 46 (61.3) | 1 (r) | 1 (r) |

| Nurses | 310 | 273 (88.1) | 4.7 (2.6-5.2)*** | 4.7 (2.6-8.3)*** |

| Technicians | 57 | 42 (73.7) | 1.7 (0.8-3.7) | 1.7 (0.8-3.7) |

COR=crude odds ratio, AOR=adjusted odds ratio, CI=confidence interval r=reference category. *,**,*** significant compare to the reference category at P≤0.05, ≤0.01 & ≤0.001; respectively

Odds of vaccination were the highest (88.1%, 273/310) among nurses (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2.6–5.2; P ≤ 0.001), followed by (73.7%, 42/57) among technicians (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.8–3.7) compared with physicians (61.3%, 46/75, reference group) [Table 1].

Among the compliant group of HCWs, the overall anti-HBs positivity of 97% (350/361) was observed, whereas 3% (11/361) of them remained anti-HBs negative 3 months after receiving the third dose of HBV vaccine. The seroconversion rates among technicians (95.2%, 40/42), nurses (97.1%, 265/273), and physicians (97.8%, 45/46) were comparable [Table 2].

Table 2.

Seroconversion and its associated factors among compliant (n=361)

| Total | Responders n (%) | COR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 361 | 350 (97.0) | |

| Age (years): | |||

| <30 | 207 | 197 (95.2) | 1 (r) |

| 30 & more | 154 | 153 (99.4) | 7.7 (1.0-61.3) |

| Sex: | |||

| Male | 103 | 100 (97.1) | 1 (r) |

| Female | 258 | 250 (96.9) | 0.9 (0.2-3.6) |

| Job: | |||

| Doctors | 46 | 45 (97.8) | 1 (r) |

| Nurses | 273 | 265 (97.1) | 0.7 (0.1-6.0) |

| technicians | 42 | 40 (95.2) | 0.2 (0.4-1.1) |

COR=crude odds ratio, CI=confidence interval, r=reference category

The reasons for not being vaccinated or not receiving the full course of the vaccine included the fear of vaccine side effects 25/81 (30.9%), lack of trust in the vaccine effectiveness 18/81 (22.2%), fear of injection 14/81 (17.3%), natural immunity by initial Hbs titre ≥10 mIU/mL 10/81 (12.3%), lack of time 9/81 (11.1%), and existing health issues 5/81 (6.2%) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Reasons for non-compliance among healthcare workers at Mansoura Gastrointestinal surgical center (n=81)

| Causes | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Fear of vaccine side effects | 25 (30.9%) |

| Lack of trust in the vaccine effectiveness | 18 (22.2%) |

| Fear of injection | 14 (17.3%) |

| Natural Immunity by initial Hbs titre ≥10 mIU/mL | 10 (12.3%) |

| Lack of time | 9 (11.1%) |

| Assuming contraindications due to pregnancy and lactation | 5 (6.2%) |

| Total | 81 (100%) |

DISCUSSION

Vaccination of HCWs is a critical component of the infection control program in healthcare settings. Complete adherence of HCWs to the full 3 doses of HBV vaccine can provide a protective antibody level of 10 mIU/ml or more up to 10 years, therefore eliminating the need for a booster dose before this period. Currently, the compliance of HCWs to the immunization program against HBV had been a matter of concern.[9]

In this study, we examined the adherence and effectiveness of HBV vaccination among healthcare workers at Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt. In the present study, the hepatitis B vaccination coverage rate was 81.7% higher than those in previously published studies where rates ranged from 49.6–60%.[10,11] However, it was comparable to several studies where rate ranged from 82–85.3%.[12,13,14,15,16]

The high vaccination coverage rate observed in our study can be explained by the adequate awareness of HCWs about the hazard of contracting infection and risk perception of subsequent complications.

Interestingly, among various professional groups, physicians emerged as the most noncompliant of HCWs in this study compared with 73.7% of technicians and 88.1% of nurses. Although several studies have reported lower compliance rates among physicians, ranging from 32% to 52.9%.[9,17] The compliance rate of 61.3% observed among physicians in this study is much lower compared to those of 88.0% and 98.6%, respectively.[18,19]

A negligent behavior for HBV vaccine and other infection control measures is widely reported among physicians.[9] It was hard to explain, considering their continuous participation in surgical procedures, placement of central venous catheters, and insertion of other invasive devices.

However, the burden of hospital work, longer schedule of recombinant HBV vaccine requiring 6 months to complete, lack of initiative, could be the underlying factors of non-vaccination among physicians.[9]

The overall seroconversion after vaccination (anti-HBs levels 10 mIU/mL) was achieved in 97.1% (350/361) of the compliant HCWs, while 3% (11/361) of them failed to achieve an adequate response to HBV vaccine (non-responders). The anti-HBs positivity rate of more than 90–95% and non-response rate of 5–10% among healthy HBV vaccines was reported in several studies.[9,20,21]

Moreover, our results revealed that the main causes for not being vaccinated included the fear of vaccine side effects 25/81 (30.9%), lack of trust in the vaccine effectiveness 18/81 (22.2%), fear of injection 14/81 (17.3%), natural immunity by initial Hbs titre ≥10 mIU/mL 10/81 (12.3%), lack of time 9/81 (11.1%), and existing health issues 5/81 (6.2%).

Similarly, in a study by Papagiannis et al. (2016), 30% of the unvaccinated health professionals declared fear over HBV vaccine safety.[22] Therefore, the use of targeted educational programs tailored to the needs of healthcare workers and specifically designed vaccination program in which infection control practitioners would take the initiative and approach the healthcare workers at their workplace can further increase vaccination coverage.[23]

CONCLUSION

The outcome of the present study indicates that the odds of non-compliance are higher among physicians. These results emphasize the need to apply alternative and innovative measures including an accelerated 3-week hepatitis B vaccination given on days 0, 7, and 21 providing protective immunity in a relatively shorter period which could be a reasonable option for physicians.[24] Although the 3-week approach has limited value in our study, lack of time is a well-recognized cause of non-compliance among physicians. Also, by approaching the physicians at their workplace and the use targeted education program about the importance of vaccination and its protective role.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient (s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the HCWs of Mansoura Gastroenterology Surgical Center for participating in this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khaled IAEA, Mahmoud OM, Saleh AF, Bioumie EE. Prevalence of HBV genotypes among Egyptian hepatitis patients. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:4353–7. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters MG. Hepatitis B virus infection: What is current and new. Top Antivir Med. 2019;26:112–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das S, Ramakrishnan K, Behera SK, Ganesapandian M, Xavier AS, Selvarajan S. Hepatitis B vaccine and immunoglobulin: Key concepts. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7:165–71. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2018.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beltrami EM, Williams IT, Shapiro CN, Chamberland ME. Risk and management of blood-borne infections in health care workers. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:385–407. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.3.385-407.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishimaru T, Wada K, Smith DR. A consensus for occupational health management of healthcare workers infected with human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and/or hepatitis C virus. J Occup Health. 2017;59:304–8. doi: 10.1539/joh.16-0275-OP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasin J, Fisseha R, Mekonnen F, Yirdaw K. Occupational exposure to blood and body fluids and associated factors among health care workers at the University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Environ Health Prev Med. 2019;24:18. doi: 10.1186/s12199-019-0769-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salama II, Sami SM, Said ZNA, El-Sayed MH, El Etreby LA, Rabah TM, et al. Effectiveness of hepatitis B virus vaccination program in Egypt: Multicenter national project. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2418–26. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i22.2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chathuranga L, Noordeen F, Abeykoon A. Immune response to hepatitis B vaccine in a group of health care workers in Sri Lanka. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e1078–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panhotra B, Saxena AK, Al-Hamrani HA, Al-Mulhim A. Compliance to hepatitis B vaccination and subsequent development of seroprotection among health care workers of a tertiary care center of Saudi Arabia. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33:144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batra V, Goswami A, Dadhich S, Kothari D, Bhargava N. Hepatitis B immunization in healthcare workers. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:276–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Q, Wang F, Zheng H, Zhang G, Miao N, Sun X, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among health care workers in China. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinelli MIS, Moreira TdNF, Paulino ÉRC, da Rocha MCP, Graciani FB, de Moraes-Pinto MI. Immune status and risk perception of acquisition of vaccine preventable diseases among health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:858–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.04.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vranckx R, Jacques P, De Schrijver A, Moens G. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage in Belgian health care workers. Infection. 2004;32:278–81. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-2204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.FitzSimons D, Hendrickx G, Lernout T, Badur S, Vorsters A, Van Damme P. Incentives and barriers regarding immunization against influenza and hepatitis of health care workers. Vaccine. 2014;32:4849–54. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroffolini T, Coppola R, Carvelli C, D'Angelo T, De Masi S, Maffei C, et al. Increasing hepatitis B vaccination coverage among healthcare workers in Italy 10 years apart. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:275–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanase M, Murata K, Mikami S, Nozaki Y, Masaki N, Mizokami M. Hepatitis B virus vaccination-related seroprevalence among health-care personnel in a Japanese tertiary medical center. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:1330–7. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fatusi A, Esimai A, Onayade A, Ojo O. Aceptance of hepatitis B vaccine by workers in a Nigerian teaching hospital. East Afr Med J. 2000;77:608–12. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v77i11.46734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyawali P, Rice P, Tilzey A. Exposure to blood borne viruses and the hepatitis B vaccination status among healthcare workers in inner London. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55:570–2. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.8.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manso VF, Castro KF, Matos SM, Junqueira ALN, Souza SB, Sousa MM, et al. Compliance with hepatitis B virus vaccination and risk of occupational exposure to blood and other body fluids in intensive care department personnel in Brazil. Am J Infect Control. 2003;31:431–4. doi: 10.1067/mic.2003.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubba A, Taylor P, Graneek B, Strobel S. Non-responders to hepatitis B vaccination: A review. Commun Dis Public Health. 2003;6:106–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu AS, Cheung RC, Keeffe EB. Hepatitis B vaccines. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:283–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papagiannis D, Tsimtsiou Z, Chatzichristodoulou I, Adamopoulou M, Kallistratos I, Pournaras S, et al. Hepatitis B virus vaccination coverage in medical, nursing, and paramedical students: A cross-sectional, multi-centered study in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:323. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saltoğlu N, Inal AS, Tasova Y, Kandemir O. Comparison of the accelerated and classic vaccination schedules against Hepatitis B: Three-week Hepatitis B vaccination schedule provides immediate and protective immunity. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2003;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris AM, Hepatitis B. In: CDC Yellow Book: Health Information For International Travel. Brunette GW, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 2020. pp. 223–9. [Google Scholar]