TOP 10 TAKE-HOME MESSAGES FOR ADULTS WITH HEART FAILURE

This document describes performance measures for heart failure that are appropriate for public reporting or pay-for-performance programs.

The performance measures are from the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America heart failure guideline update and are selected from the strongest recommendations (Class 1 or 3).

Quality measures are also provided that are not yet ready for public reporting or pay for performance but might be useful for clinicians and healthcare organizations for quality improvement.

A new safety measure (laboratory monitoring for patients treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists) is paired with a new treatment measure (mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction).

Other additions to the performance measures include the new medication sacubitril/valsartan and use of cardiac resynchronization therapy.

To address frequent lack of titration of heart failure medications, 2 new performance measures are included based on dose, either reaching 50% of the recommended dose (e.g., beta blocker or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor antagonist/angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor) or documenting that such a dose was not tolerated or otherwise inappropriate.

For all measures, if the clinician determines the care is inappropriate for the patient, that patient is excluded from the measure.

For all measures, patients who decline treatment or care are excluded.

A patient-centered discussion of the benefits and risks of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator treatment remains a performance measure.

To reflect the increasing importance of patient-reported outcome measures, 2 patient-reported outcomes quality measures were added that use heart failure patient-reported outcomes questionnaires currently accepted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

PREAMBLE

The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) performance measurement sets serve as vehicles to accelerate translation of scientific evidence into clinical practice. Measure sets developed by the ACC/AHA are intended to provide practitioners and institutions that deliver cardiovascular services with tools to measure the quality of care provided and identify opportunities for improvement.

Writing committees are instructed to consider the methodology of performance measure development (1,2) and to ensure that the measures developed are aligned with ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. The writing committees also are charged with constructing measures that maximally capture important aspects of care quality, including timeliness, safety, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and patient-centeredness, while minimizing, when possible, the reporting burden imposed on hospitals, practices, and practitioners.

Potential challenges from measure implementation may lead to unintended consequences. The manner in which challenges are addressed is dependent on several factors, including the measure design, data collection method, performance attribution, baseline performance rates, reporting methods, and incentives linked to these reports.

The ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures (Task Force) distinguishes quality measures from performance measures. Quality measures are those metrics that may be useful for local quality improvement but are not yet appropriate for public reporting or pay for performance programs (uses of performance measures). New measures are initially evaluated for potential inclusion as performance measures. In some cases, a measure is insufficiently supported by the guidelines. In other instances, when the guidelines support a measure, the writing committee may feel it is necessary to have the measure tested to identify the consequences of measure implementation. Quality measures may then be promoted to the status of performance measures as supporting evidence becomes available.

P. Michael Ho, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA Chair, ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2019, the Task Force convened the writing committee to begin the process of revising the existing performance measures set for heart failure that was released in 2011 (3). The writing committee also was charged with the task of developing new measures to evaluate the care of patients in accordance with the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update (4).

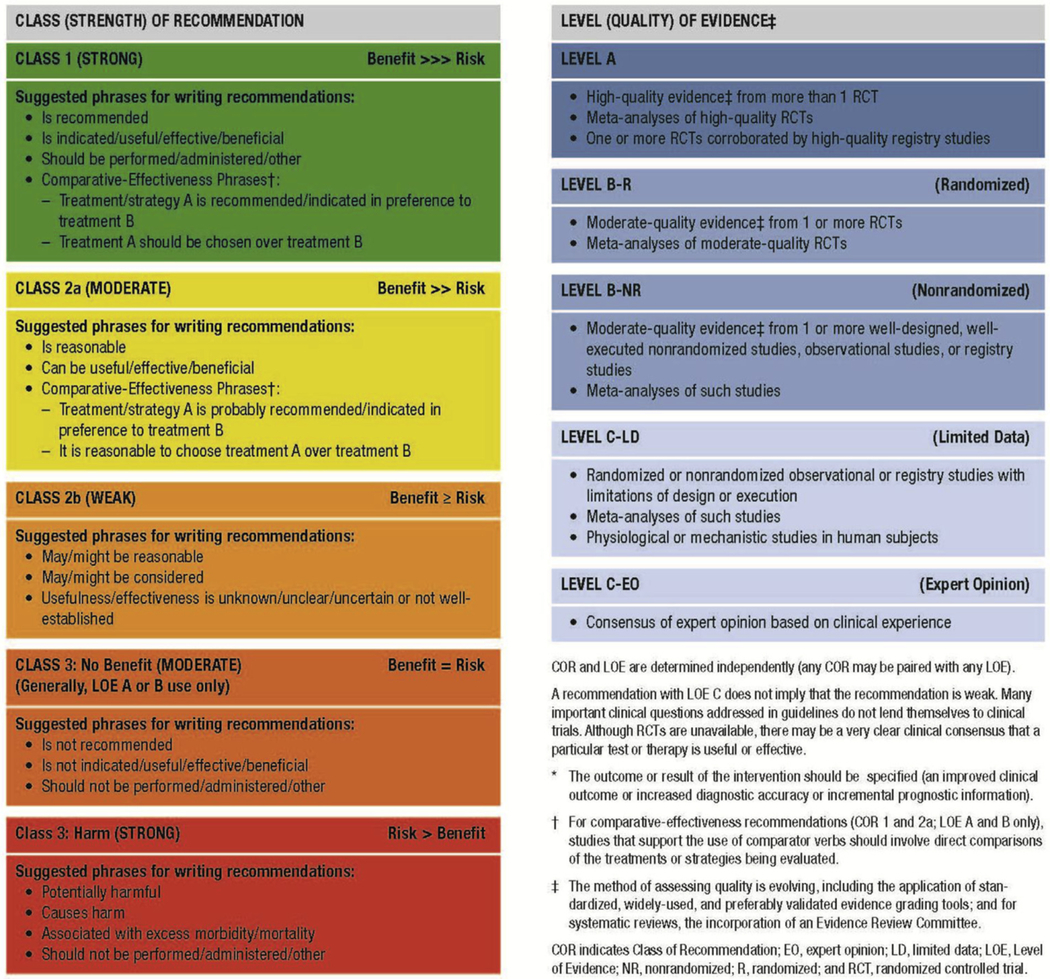

This updated performance measure set addresses in-hospital and continuing care in the outpatient setting. All Class 1 (strong) and 3 (no benefit or harmful, process to be avoided) guideline-recommended processes were considered for inclusion as performance measures. The current Class of Recommendation and Level of Evidence guideline classification scheme used by the ACC and AHA in their clinical guidelines is shown in Table 1. The value (benefit and cost) of a process of care was also considered. If high-quality, published, cost-effectiveness studies indicate that a Class 1 guideline recommendation for a process of care is considered a poor value by ACC/AHA standards, then it was not included as a performance measure (5). There were no Class 1 recommended processes of care judged to be of poor value. All ACC/AHA clinical practice guideline recommendations (including Class 2) were considered as potential quality measures. Ultimately, we selected measures based on their importance for health, existing gaps in care, ease of implementation, potential duplication with other performance measure lists, and risk for unintended consequences.

TABLE 1.

Applying Class of Recommendation and Level of Evidence to Clinical Strategies, Interventions, Treatments, or Diagnostic Testing in Patient Care* (Updated May 2019)

|

The writing committee developed a comprehensive heart failure measure set that includes 18 measures: 13 performance measures, 4 quality measures, 1 structural measure, and 2 rehabilitation performance measures (from the 2018 ACC/AHA performance measures for cardiac rehabilitation (6)), as reflected in Table 2 and Appendix A. The performance measures for heart failure included in the measure set are summarized in Table 2, which provides information on the measure number, measure title, and care setting. The measure specifications (Appendix A) provide information included in Table 2 and more detailed information including, the measure description, numerator, denominator (i.e., denominator exclusions and exceptions), rationale for the measure, clinical practice guideline that supports the measure, measurement period, source of data, and attribution.

TABLE 2.

ACC/AHA 2020 Heart Failure Clinical Performance, Quality and Structural Measures

| Measure No. | Measure Title | Care Setting | Attribution | Measure Domain | COR/LOE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Measures | ||||||

| PM-1 | LVEF assessment | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Diagnostic | COR: 1, LOE: C; COR: 2a, LOE: C | |

| PM-2 | Symptom and activity assessment | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Monitoring | COR: 1, LOE: C | |

| PM-3 | Symptom management | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | See measure rationale in Appendix A for details | |

| PM-4 | Beta-blocker therapy for HFrEF | Outpatient, Inpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: A; COR: 1, LOE: B | |

| PM-5 | ACE inhibitor or ARB or ARNI therapy for HFrEF | Outpatient, Inpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: A; COR: 1, LOE: B-R | |

| PM-6 | ARNI therapy for HFrEF | Outpatient, Inpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: B-R | |

| PM-7 | Dose of beta-blocker therapy for HFrEF | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: A | |

| PM-8 | Dose of ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI therapy for HFrEF | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: A; COR: 1, LOE: B-R | |

| PM-9 | MRA therapy for HFrEF | Outpatient, Inpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: A; COR: 1, LOE: B | |

| PM-10 | Laboratory monitoring in new MRA therapy | Outpatient, Inpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Monitoring | COR: 1, LOE: A | |

| PM-11 | Hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate therapy for HFrEF in those self-identified as Black or African American | Outpatient, Inpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: A | |

| PM-12 | Counseling regarding ICD implantation for patients with HFrEF on guideline- directed medical therapy | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: A | |

| PM-13 | CRT implantation for patients with HFrEF on guideline-directed medical therapy | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 1, LOE: A; COR: 1, LOE: B | |

| Quality Measures | ||||||

| QM-1 | Patient self-care education | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Self-Care | COR: 1, LOE: B | |

| QM-2 | Measurement of patient-reported outcome-health status | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Monitoring | See measure rationale in Appendix A for details | |

| QM-3 | Sustained or improved health status in heart failure | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Outcome | See measure rationale in Appendix A for details | |

| QM-4 | Postdischarge appointment for patients with heart failure | Inpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Treatment | COR: 2a, LOE: B | |

| Structural Measure | ||||||

| SM-1 | Heart failure registry participation | Outpatient, Inpatient | Facility | Structure | COR: 2a, LOE: B | |

|

Rehabilitation Performance Measures Related to Heart Failure (From the 2018 ACC/AHA performance measures for cardiac rehabilitation (6)) | ||||||

| Rehab PM-2 | Exercise training referral for HF from inpatient setting | Inpatient | Facility | Process | COR: 1, LOE: A | |

| Rehab PM-4 | Exercise training referral for HF from outpatient setting | Outpatient | Individual practitioner, Facility | Process | COR: 1, LOE: A | |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; COR, class of recommendation; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; HF, heart failure; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LOE, level of evidence; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; PM, performance measure; QM, quality measure; and SM, structural measure.

The writing committee recognized that the 2018 ACC/AHA performance measures for cardiac rehabilitation have been published that address heart failure (6). The cardiac rehabilitation measure set includes performance measures for exercise training referral for inpatients and outpatients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (Table 2). These rehabilitation measures also should be considered heart failure–related ACC/AHA performance measures.

A comprehensive list of contraindications to care is not provided. Instead, it is expected that clinical judgment will be used to determine if a contraindication exists. For example, certain patients with heart failure and congenital heart disease would not qualify for certain treatment measures and should be excluded from the denominator if documented by the clinician.

Although the measures are published as a set, their implementation can be individualized. It is not expected that all measures will be adopted simultaneously. Although all the measures are considered valuable in improving care, we recognize that organizations may only be able to focus on a limited number of measures. When implementing any measure that involves patient input, it is important to consider the patient’s health literacy and adapt data collection accordingly. Performance measures are a critical step in addressing disproportionately lower quality of care and potentially worse health status and outcomes among an underserved population.

1.1. Scope of the Problem

Heart failure is a major and growing public health problem in the United States with significant morbidity, mortality, and associated cost. A detailed discussion of the scope of the problem and opportunities to improve the quality of care that is provided to patients with this condition is available in the ACCF/AHA 2013 heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) and 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update (4).

1.2. Disclosure of Relationships With Industry and Other Entities

The Task Force makes every effort to avoid actual, potential, or perceived conflicts of interest that could arise as a result of relationships with industry or other entities (RWI). Information about the ACC/AHA policy on RWI can be found online. All members of the writing committee, as well as those selected to serve as peer reviewers of this document, were required to disclose all current relationships and those existing within the 12 months before the initiation of this writing effort. ACC/AHA policy also requires that the writing committee chair and at least 50% of the writing committee have no relevant RWI. Writing committee members are excluded from voting on sections to which their specific RWI may apply.

Any writing committee member who develops new RWI during his or her tenure on the writing committee is required to notify staff in writing. These statements are reviewed periodically by the Task Force and by members of the writing committee. Writing committee member and peer reviewer RWI, which are pertinent to the document, are included in the appendixes: Appendix B for relevant writing committee RWI and Appendix C for comprehensive peer reviewer RWI. Additionally, to ensure complete transparency, the writing committee members’ comprehensive disclosure information, including RWI not relevant to the present document, is available online. Disclosure information for the Task Force is also available online.

The work of the writing committee was supported exclusively by the ACC and the AHA without commercial support. Members of the writing committee volunteered their time for this effort. Meetings of the writing committee were confidential and attended only by writing committee members and staff from the ACC, AHA, and the Heart Failure Society of America, which served as a collaborator on this project.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Literature Review

In developing the updated heart failure measure set, the writing committee reviewed evidence-based guidelines and statements that would potentially impact the construct of the measures. The clinical practice guidelines and scientific statements that most directly contributed to the development of these measures are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Associated ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines and Other Clinical Guidance Documents

| Clinical Practice Guidelines |

|---|

| 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update (4) |

| 2016 ESC heart failure diagnosis and treatment guidelines (8) |

| 2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) |

| 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS ventricular arrhythmias and prevention of sudden cardiac death guideline (9) |

| Performance Measures |

| 2011 ACCF/AHA/PCPI heart failure performance measurement set (3) |

| 2018 ACC/AHA performance measures for cardiac rehabilitation (6) |

| 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for optimization of heart failure treatment (10) |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HFSA, Heart Failure Society of America; HRS, Heart Rhythm Society; and PCPI, Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement.

2.2. Definition and Selection of Measures

The writing committee considered a number of additional factors, which are listed in Table 4. The potential impact, appropriateness for public reporting and pay for performance, validity, reliability, and feasibility were considered. The writing committee examined available information on current gaps in care. The term “heart failure” refers to stage C or D heart failure unless otherwise stated (4).

TABLE 4.

ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures: Attributes for Performance Measures (11)

| 1. Evidence Based | |

|---|---|

| High-impact area that is useful in improving patient outcomes | a) For structural measures, the structure should be closely linked to a meaningful process of care that, in turn, is linked to a meaningful patient outcome. b) For process measures, the scientific basis for the measure should be well established, and the process should be closely linked to a meaningful patient outcome. c) For outcome measures, the outcome should be clinically meaningful. If appropriate, performance measures based on outcomes should adjust for relevant clinical characteristics through the use of appropriate methodology and high-quality data sources. |

| 2. Measure Selection | |

| Measure definition | a) The patient group to whom the measure applies (denominator) and the patient group for whom conformance is achieved (numerator) are clearly defined and clinically meaningful. |

| Measure exceptions and exclusions | b) Exceptions and exclusions are supported by evidence. |

| Reliability | c) The measure is reproducible across organizations and delivery settings. |

| Face validity | d) The measure appears to assess what it is intended to. |

| Content validity | e) The measure captures most meaningful aspects of care. |

| Construct validity | f) The measure correlates well with other measures of the same aspect of care. |

| 3. Measure Feasibility | |

| Reasonable effort and cost | a) The data required for the measure can be obtained with reasonable effort and cost. |

| Reasonable time period | b) The data required for the measure can be obtained within the period allowed for data collection. |

| 4. Accountability | |

| Actionable | a) Those held accountable can affect the care process or outcome. |

| Unintended consequences avoided | b) The likelihood of negative, unintended consequences with the measure is low. |

Reproduced with permission from Thomas et al (6). Copyright © 2018, American Heart Association, Inc., and American College of Cardiology Foundation.

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; and AHA, American Heart Association.

3. ACC/AHA HEART FAILURE MEASURE SET

3.1. Discussion of Changes to 2011 Heart Failure Measure Set

After reviewing the existing clinical practice guidelines, and the 2011 ACCF/AHA/PCPI heart failure performance measurement set (3), the writing committee discussed which measures required revision to reflect updated science related to heart failure and identified which guideline recommendations could serve as the basis for new performance or quality measures. The writing committee also reviewed existing publicly available measure sets.

These subsections serve as a synopsis of the revisions that were made to previous measures and a description of why the new measures were created for both the inpatient and outpatient setting.

3.1.1. Retired Measures

The writing committee decided to retire the left ventricular ejection fraction assessment measure used in the inpatient setting due to >97% of use (12) (Table 5). Left ventricular ejection fraction assessment in the outpatient setting was retained.

TABLE 5.

Retired Heart Failure Measures From the 2011 Set (3)

| Measure No. | Care Setting | Measure Title | Rationale for Retiring the Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Inpatient | LVEF assessment | Inpatient documentation of LVEF is at >97% (12). |

LVEF indicates left ventricular ejection fraction.

3.1.2. Revised Measures

The writing committee reviewed and made changes to the patient self-care education, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker therapy for left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and postdischarge appointment measures, as summarized in Table 6. Table 6 provides information on the updated measures including the care setting, title, and a brief rationale for revisions made to the measures.

TABLE 6.

Revised Heart Failure Measures

| Measure No. | Measure Title | Description of Revision | Rationale for Revision |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Patient self-care education | Moved from Performance Measure to Quality Measure | Concern regarding the accuracy of self-care education documentation; limited evidence of improved outcomes with better documentation. |

| 7 | ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy for LVSD | Added ARNI | 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update (4) made this revision to the recommendation. |

| 9 | Postdischarge appointment | Moved from Performance Measure to Quality Measure and included a time limit of 7 d | 2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) lists postdischarge appointment from 7–14 d as a Class 2a recommendation. |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; HF, heart failure; and LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

3.1.3. New Measures

The writing committee created 7 new performance measures (PM 6–11, 13), 2 quality measures (QM 2, 3), and 1 structural measure (SM-1) (Table 7). Six of the new performance measures were based on Class 1 guideline recommendations for therapies known to prolong survival. An additional performance measure (PM-10, measurement of potassium after a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist prescription) is also guideline recommended and included as a safety measure to accompany prescription for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (PM-9). Two new measures based on dose were created (PM-7 and PM-8). These were chosen because of the gap between doses used in practice and those shown to provide survival benefit in clinical trials. They were designed to apply only to those patients without demonstrated intolerance at higher doses.

TABLE 7.

New Heart Failure Measures

| Measure No. | Care Setting | Measure Title | Rationale for Creating New Measure | Rationale for Designating as a Quality Measure Versus a Performance Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM-6 | Outpatient, Inpatient | ARNI therapy for HFrEF | Important outcome benefit with large existing gap in care | N/A |

| PM-7 | Outpatient | Dose of beta-blocker therapy for HFrEF | Important outcome benefit and large existing gap in care | N/A |

| PM-8 | Outpatient | Dose of ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI therapy for HFrEF | Important outcome benefit and large existing gap in care | N/A |

| PM-9 | Outpatient, Inpatient | MRA therapy for HFrEF | Important outcome benefit and large existing gap in care | N/A |

| PM-10 | Outpatient, Inpatient | Laboratory monitoring in new MRA therapy | Important outcome benefit and large existing gap in care | N/A |

| PM-11 | Outpatient, Inpatient | Hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate therapy for HFrEF in those self-identified as Black or African American | Important outcome benefit and large existing gap in care | N/A |

| PM-13 | Outpatient | CRT implantation for patients with HFrEF on guideline-directed medical therapy | Important outcome benefit and large existing gap in care | N/A |

| QM-2 | Outpatient | Measurement of patient-reported, outcome-health status | Important outcome that is rarely measured | Best method of implementation is unclear |

| QM-3 | Outpatient | Sustained or improved health status in heart failure | Important outcome that is rarely measured | Needs validated risk-adjustment |

| SM-1 | Outpatient, Inpatient | Heart failure registry participation | Registries are a useful structure for measuring performance | Additional data needed to determine the impact of registry participation on quality |

ACE indicates angiotensin–converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; N/A, not applicable; PM, performance measure; QM, quality measure; and SM, structural measure.

For more detailed information on each measure’s construct, refer to the specifications in Appendix A.

4. AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

There are multiple ways that cardiac rehabilitation and exercise prescriptions can be implemented (13). Further studies are needed to determine if there are differences in the magnitude of outcome improvements by approach. Similarly, although patient-reported outcomes are considered an important metric, the best way to measure these needs additional research. Two surveys are well validated: The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (14) and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (15). However, risk-adjustment is required to fairly compare groups for use as an outcome measure. The collection of the measure (process of care) does not require risk-adjustment but will benefit from additional research to understand optimal timing of collection of patient-reported outcomes, including frequency and relation to the clinic visit. Finally, data supporting sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors are emerging for heart failure treatment; however, with additional trials ongoing and having not been integrated into guideline recommendations at the time of generation of the measure set, the writing committee was unable to include them in the measure set.

ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures

P. Michael Ho, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA Chair‡

H. Vernon Anderson, MD, FACC‡

Ankeet S. Bhatt, MD, MBA§

Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA, FHFSA§

Sandeep Das, MD, MPH, FACC§

Joao F. Monteiro Ferreira, MD, PhD, FACC‡

Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, FACC, FAHA, FHFSA, Ex Officio§

Stacy Garcia, RT(R), RN, BSN, MBA-HCM‡

Michael E. Hall, MD, MS, FACC, FAHA§

Hani Jneid, MD, FACC, FAHA§

Patricia A. Keegan, DNP, APRN, NP-C‡‖

Christopher Lee, PhD, RN, FAHA, FHFSA§

Leo Lopez, MD, FACC, FAHA‡

Jeffrey W. Olin, DO, FACC, FAHA§

Manesh R. Patel, MD, FACC§

Faisal Rahman, BM BCh‡

Matthew Roe, MD, FACC‡‖

Katherine B. Salciccioli, MD§

Alex Sandhu, MD, MS‡‖

Randal J. Thomas, MD, MS, FACC, FAHA‡‖

Siqin Kye Ye, MD, MS‡‖

Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA‡

‡American College of Cardiology Representative.

§American Heart Association Representative.

‖Former Task Force member; current member during the writing effort.

STAFF

American College of Cardiology

Athena Poppas, MD, FACC, President

Cathleen Gates, Interim Chief Executive Officer

John S. Rumsfeld, MD, PhD, FACC, Chief Science and Quality Officer

Lara Slattery, Division Vice President, Clinical Registry and Accreditation

Grace Ronan, Team Lead, Clinical Policy Publication

Timothy W. Schutt, MA, Clinical Policy Analyst

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association

Abdul R. Abdullah, MD, Director, Guideline Science and Methodology

Rebecca L. Diekemper, MPH, Guideline Advisor, Performance Measures

American Heart Association

Robert A. Harrington, MD, FAHA, President

Nancy Brown, Chief Executive Officer

Mariell Jessup, MD, FAHA, Chief Science and Medical Officer

Radhika Rajgopal Singh, PhD, Vice President, Office of Science, Medicine, and Health

Paul St. Laurent, DNP, RN, Senior Science and Medicine Advisor

Melanie Shahriary, RN, BSN, Senior Manager, Performance Metrics, Quality and Health IT

Jody Hundley, Production and Operations Manager, Scientific Publications, Office of Science Operations

APPENDIX A. HEART FAILURE MEASURE SET

Performance Measures for Heart Failure

SHORT TITLE: PM-1 Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Assessment (Outpatient Setting)

PM-1: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Assessment (Outpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure for whom the quantitative result of prior (any time in the past) LVEF assessment, using any imaging modality, is available in the medical record | |

| Numerator | Patients for whom the quantitative* results of prior (any time in the past) LVEF assessment, using any imaging modality, is available in the medical record (includes note documentation) *Single value or numerical range |

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not evaluating LVEF (e.g., comfort care only) Documentation of patient reason(s) for not evaluating LVEF (e.g., patient refusal) |

| Measurement Period | 12 mo |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient |

| Rationale | |

| Evaluation of LVEF in patients with heart failure provides important information that is required to appropriately direct treatment. Several pharmacological therapies have demonstrated efficacy in slowing disease progression and improving survival in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction (3). Although most patients have an LVEF recorded, this remains a performance measure because knowledge of LVEF is required to determine eligibility for appropriate heart failure care. Patients post-heart transplant or with an LVAD are excluded, because these patients were excluded from clinical treatment trials for low LVEF heart failure. | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. A 2-dimensional echocardiogram with Doppler should be performed during initial evaluation of patients presenting with HF to assess ventricular function, size, wall thickness, wall motion, and valve function. (Class 1, Level of Evidence: C) 2. Repeat measurement of EF and measurement of the severity of structural remodeling are useful to provide information in patients with HF who have had a significant change in clinical status; who have experienced or recovered from a clinical event; or who have received treatment, including GDMT, that might have had a significant effect on cardiac function; or who may be candidates for device therapy. (Class 1, Level of Evidence: C) 3. Radionuclide ventriculography or magnetic resonance imaging can be useful to assess LVEF and volume when echocardiography is inadequate. (Class 2a, Level of Evidence: C) | |

ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; EF, ejection fraction; EHR, electronic health record; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HF, heart failure; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and PM, performance measure.

SHORT TITLE: PM-2 Symptom and Activity Assessment (Outpatient Setting)

PM-2: Symptom and Activity Assessment (Outpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patient visits for those patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with quantitative results of an evaluation of both current level of activity and clinical symptoms documented | |

| Numerator | Patient visits with quantitative results of an evaluation of both current level of activity and clinical symptoms documented* *Evaluation and quantitative results documented can include:

The NYHA functional classification reflects a subjective assessment by a healthcare provider of the severity of a patient’s symptoms. Patients are assigned to one of the following classes:

|

| Denominator | All patient visits for those patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not evaluating both current level of activity and clinical symptoms (e.g., severe cognitive or functional impairment) Documentation of patient reason(s) for not evaluating both current level of activity and clinical symptoms |

| Measurement Period | 12 mo |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient |

| Rationale | |

| Initial and ongoing evaluations of patients with heart failure should include an assessment of symptoms and their functional consequences. These assessments serve as the basis for making treatment decisions, monitoring the effects of treatment, and modifying treatment as appropriate. Decreasing symptoms and improving function are 2 of the primary goals of heart failure treatment and represent important patient-centric outcomes for heart failure care. The ACC/AHA have not addressed PRO tool selection. However, the FDA has provided guidelines for an appropriate PRO tool (16) and, currently, 2 heart failure survey tools–the MLHFQ (15) and the KCCQ (14)–are considered qualified tools for FDA device use in heart failure (17). | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. A thorough history and physical examination should be obtained/performed in patients presenting with HF to identify cardiac and noncardiac disorders or behaviors that might cause or accelerate the development or progression of HF. (Class 1, Level of Evidence: C) 2. The NYHA functional classification gauges the severity of symptoms in those with structural heart disease. Although reproducibility and validity may be problematic (18), the NYHA functional classification is an independent predictor of mortality (19). It is widely used in clinical practice and research and for determining the eligibility of patients for certain healthcare services (7). However, NYHA functional class assessment is not reported in a significant number of patients in contemporary HF practices in the United States (20). 3. Evaluate general health status (see Figure 2, 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline) (7). Although no specific 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline recommendation is made regarding collection of NYHA or other quantitative result, knowledge of symptom status is needed to determine candidacy for appropriate HF treatments (7). | |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; EHR, electronic health record; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HF, heart failure; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PM, performance measure; and PRO, patient-reported outcome.

SHORT TITLE: PM-3 Symptom Management (Outpatient Setting)

PM-3: Symptom Management (Outpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patient visits for those patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure and with quantitative results of an evaluation of both level of activity and clinical symptoms documented in which patient symptoms have improved or remained consistent with treatment goals, or patient symptoms have worsened since last assessment and have a documented plan of care | |

| Numerator | Patient visits in which patient symptoms have improved or remained consistent with treatment goals since last assessment,* or patient symptoms have worsened since last assessment* and have a documented plan of care† *Examples of quantitative assessment:

|

| Denominator | All patient visits for those patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure and with quantitative results of an evaluation of both level of activity and clinical symptoms documented at the time of the encounter and at a prior time point 1 to 12 mo previously. |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | None |

| Measurement Period | 12 mo |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient |

| Rationale | |

| Heart failure significantly decreases HRQOL, especially in the areas of physical functioning and vitality (21,22). Lack of improvement in HRQOL after discharge from the hospital is a powerful predictor of rehospitalization and mortality (23,24). Women with heart failure have consistently been found to have worse HRQOL than men (22,25). Ethnic differences also have been found, with Mexican Hispanics reporting better HRQOL than other ethnic groups in the United States (26). Other determinants of poor HRQOL include depression, younger age, higher BMI, greater symptom burden, lower systolic blood pressure, sleep apnea, low perceived control, and uncertainty about prognosis (25,27–31). Objective data on symptoms and functional status from at least 2 time points are needed to decide if patients are benefitting from therapy. | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. Goals of treatment in heart failure are to improve health-related quality of life and symptoms (see Figure 3, 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline) (7). | |

ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; BMI, body mass index; EHR, electronic health record; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PM, performance measure; PRO, patient-reported outcome; VE/VCO2, ventilation and carbon dioxide; and VO2, oxygen consumption.

SHORT TITLE: PM-4 Beta-Blocker Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

PM-4: Beta-Blocker Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% who were prescribed beta-blocker therapy either within a 12-mo period when seen in the outpatient setting or at hospital discharge | |

| Numerator | Patients who were prescribed* beta-blocker therapy† either within a 12-mo period when seen in the outpatient setting or at hospital discharge *Prescribed may include:

|

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not prescribing beta-blocker therapy (e.g., intolerance) Documentation of patient reason(s) for not prescribing beta-blocker therapy (e.g., patient refusal) |

| Measurement Period | 12 mo |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient Inpatient |

| Rationale | |

| Beta blockers improve survival and reduce hospitalization for patients with stable heart failure and reduced LVEF (HFrEF) (7). Treatment should be initiated as soon as a patient is diagnosed with reduced LVEF and does not have prohibitively low systemic blood pressure, fluid overload, or recent treatment with an intravenous positive inotropic agent. Beta blockers have also been shown to lessen the symptoms of heart failure, improve the clinical status of patients, and reduce future clinical deterioration. Despite these benefits, use of beta blockers in eligible patients remains suboptimal (20). | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. Use of 1 of the 3 beta blockers proven to reduce mortality (e.g., bisoprolol, carvedilol, and sustained-release metoprolol succinate) is recommended for all patients with current or prior symptoms of HFrEF, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality (32–37). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) 2. Initiation of beta-blocker therapy is recommended after optimization of volume status and successful discontinuation of intravenous diuretics, vasodilators, and inotropic agents. Beta-blocker therapy should be initiated at a low dose and only in stable patients. Caution should be used when initiating beta blockers in patients who have required inotropes during their hospital course (38–40). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: B) | |

ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; EHR, electronic health record; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and PM performance measure.

SHORT TITLE: PM-5 Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor or Angiotensin Receptor Blocker or Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

PM-5: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor or Angiotensin Receptor Blocker or Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% who were prescribed ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI either within a 12-mo period when seen in the outpatient setting or at hospital discharge | |

| Numerator | Patients who were prescribed* ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI either within a 12-mo period when seen in the outpatient setting or at hospital discharge *Prescribed may include:

|

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not prescribing ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI (e.g., intolerance) Documentation of patient reason(s) for not prescribing ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI (e.g., patient refusal) |

| Measurement Period | ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI therapy initiated within a 12-mo period of being seen in the outpatient setting or from hospital discharge |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient Inpatient |

| Rationale | |

| Use of ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI therapy has been associated with improved outcomes in patients with reduced LVEF (7). Long-term therapy with ARBs has also been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality, especially in ACE inhibitor-intolerant patients (41–44). More recently, ARNI therapy has also been shown to more significantly improve outcomes (45), such that the newest guidelines recommend replacement of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with ARNI therapy in eligible patients (4). However, despite the benefits of these drugs, use of ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI remains suboptimal (20). | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update (4) 1. The clinical strategy of inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system with ACE inhibitors (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) (46–51), OR ARBs (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) (41–44), OR ARNI (Class 1, Level of Evidence: B-R) (45) in conjunction with evidence-based beta blockers (7,33,52), and aldosterone antagonists in selected patients (53,54), is recommended for patients with chronic HFrEF to reduce morbidity and mortality. | |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; EHR, electronic health record; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; HFSA, Heart Failure Society of America; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and PM, performance measure.

SHORT TITLE: PM-6 Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

PM-6: Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% who remained symptomatic at NYHA functional class II or class III despite ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy for a least 3 mo and were prescribed ARNI therapy either within a 12-mo period when seen in the outpatient setting or at hospital discharge | |

| Numerator | Patients who were prescribed* ARNI therapy either within a 12-mo period when seen in the outpatient setting or at hospital discharge *Prescribed may include:

|

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% after 3 mo of ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD NYHA class I and class IV |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not prescribing ARNI therapy (e.g., intolerant) Documentation of patient reason(s) for not prescribing ARNI therapy (e.g., patient refusal, cost) Documentation of system reason(s) for not prescribing ARNI therapy |

| Measurement Period | ARNI therapy initiated within a 12-mo period of being seen in the outpatient setting or from hospital discharge |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient Inpatient |

| Rationale | |

| In a large randomized clinical trial, an ARNI (valsartan/sacubitril) was compared with an ACE inhibitor (enalapril) in symptomatic patients with HFrEF. The ARNI reduced the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization significantly, by 20% (45). The benefit was seen to a similar extent for both death and heart failure hospitalization and was consistent across subgroups. Since the initial large randomized clinical trial with ARNI, there has been additional clinical trial evidence (55,56), meta-analyses (57), and observational clinical effectiveness studies (58), which further support the use of valsartan/sacubitril in replacement of ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy to reduce mortality and morbidity. | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update (4) 1. In patients with chronic symptomatic HFrEF NYHA class II or III who tolerate an ACE inhibitor or ARB, replacement by an ARNI is recommended to further reduce morbidity and mortality (45). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: ARNI: B-R) | |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; EHR, electronic health record; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; HFSA, Heart Failure Society of America; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; and PM, performance measure.

SHORT TITLE: PM-7 Dose of Beta-Blocker Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient Setting)

PM-7: Dose of Beta-Blocker Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% who were prescribed a guideline-recommended beta blocker (e.g., bisoprolol, carvedilol, or sustained-release metoprolol succinate) at a dose that is at least 50% of the target dose (see Table A for target doses) | |

| Numerator | Patients who were prescribed a guideline-recommended beta blocker at a dose that is at least 50% of the target dose (see Table A for target doses) |

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% who were prescribed a recommended beta blocker |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of intolerance of higher dose or medical reason(s) for not prescribing higher dose of beta blocker Documentation of patient reason(s) for not prescribing higher dose of beta blocker Documentation of system reason(s) for not prescribing higher dose of beta blocker |

| Measurement Period | Annually |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient |

| Rationale | |

| Use of guideline-recommended beta blockers has been proven to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with HFrEF, and studies have supported a dose-response relationship of beta blockers with improved outcomes (59–64). These findings suggest that, among HFrEF patients in whom target doses might be well tolerated, treating at less than the target dose may result in worse clinical outcomes. Despite guideline recommendations for clinicians to achieve target doses of beta blockers shown to be effective in major clinical trials, the percentage of patients achieving these doses is low and remains low over time (20,65,66). Treatment with a beta blocker should be initiated at very low doses, followed by gradual incremental increases in dose if lower doses have been well tolerated. Clinicians should make every effort to achieve the target doses of the beta blockers shown to be effective in major clinical trials (7). | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. Use of 1 of the 3 beta blockers proven to reduce mortality (e.g., bisoprolol, carvedilol, and sustained-release metoprolol succinate) is recommended for all patients with current or prior symptoms of HFrEF, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality (32–37). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for optimization of heart failure treatment (10) 1. After a diagnosis of heart failure is made, GDMT should be initiated and therapies should be adjusted no more frequently than every 2 weeks to target doses (or maximally tolerated doses). 2. To achieve the maximal benefits of GDMT in patients with chronic HFrEF, therapies must be initiated and titrated to maximally tolerated doses (33,45,60,67). | |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; EHR, electronic health record; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and PM, performance measure.

TABLE A.

Target Doses of Guideline-Directed Medical Therapies

| ACE Inhibitors | Target Dose | Total Daily Target Dose | 50% of Total Daily Target Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Captopril | 50 mg, three times daily | 150 mg | 75 mg |

| Enalapril | 10 mg, twice daily | 20 mg | 10 mg |

| Lisinopril | 20 mg, once daily | 20 mg | 10 mg |

| Ramipril | 10 mg, once daily | 10 mg | 5 mg |

| Perindopril | 8 mg, once daily | 8 mg | 4 mg |

| Trandolapril | 4 mg, once daily | 4 mg | 2 mg |

| Benazepril | 40 mg, once daily | 40 mg | 20 mg |

| Fosinopril | 40 mg, once daily | 40 mg | 20 mg |

| Quinapril | 20 mg, twice daily | 40 mg | 20 mg |

| ARB | |||

| Candesartan | 32 mg, once daily | 32 mg | 16 mg |

| Losartan | 100 mg, once daily* | 100 mg | 50 mg |

| Valsartan | 160 mg, twice daily | 320 mg | 160 mg |

| Irbesartan | 300 mg, once daily | 300 mg | 150 mg |

| Telmisartan | 80 mg, once daily | 80 mg | 40 mg |

| Olmesartan | 40 mg, once daily | 40 mg | 20 mg |

| Azilsartan | 80 mg, once daily | 80 mg | 40 mg |

| ARNI | |||

| Sacubitril/valsartan | 97/103 mg, twice daily | 194/206 mg | 98/102 mg† |

| Evidence-Based Beta-Blockers | |||

| Bisoprolol | 10 mg, once daily | 10 mg | 5 mg |

| Carvedilol | 25 mg, twice daily | 50 mg | 25 mg |

| Carvedilol extended release | 80 mg, once daily | 80 mg | 40 mg |

| Metoprolol succinate sustained release | 200 mg, once daily | 200 mg | 100 mg |

Sources for target doses include: 2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7), 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update (4), 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for optimization of heart failure treatment (10), and FDA-approved labels (68).

ACC/AHA Guidelines recommend losartan 150 mg as target dose. However, because current FDA-approved labeling has 100 mg as the maximal dose, the 100-mg dose is used in the performance measure.

The sacubitril 98 mg and valsartan 102 mg total daily dosing (49/51 mg twice daily) is considered fulfilling the 50% of target dosing criteria.

ACE indicates angiotensin–converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; and ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor.

SHORT TITLE: PM-8 Dose of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor, Angiotensin Receptor Blocker, or Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient Setting)

PM-8: Dose of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor, Angiotensin Receptor Blocker, or Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% who were prescribed an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI at a dose that is at least 50% of the target dose (see Table A for target doses) | |

| Numerator | Patients who were prescribed an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI at a dose that is at least 50% of the target dose (see Table A for target doses) |

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% who were prescribed an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of intolerance of higher dose or medical reason(s) for not prescribing higher dose of ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI Documentation of patient reason(s) for not prescribing higher dose of ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI Documentation of system reason(s) for not prescribing higher dose of ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI |

| Measurement Period | Annually |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient |

| Rationale | |

| Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system with ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI therapy has been proven to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with HFrEF, and studies have supported a dose-response relationship of these therapies with improved outcomes (42,50,69,70). These findings suggest that, among HFrEF patients in whom target doses might be well tolerated, treating at less than the target dose may result in worse clinical outcomes. Despite guideline recommendations for clinicians to achieve target doses of ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or ARNIs, the number of patients achieving these doses is low and remains low over time (20,65,66). | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update (4) 1. The clinical strategy of inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system with ACE inhibitors (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) (46–51), OR ARBs (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) (41–44), OR ARNI (Class 1, Level of Evidence: B-R) (45) in conjunction with evidence-based beta blockers (7,33,52), and aldosterone antagonists in selected patients (53,54), is recommended for patients with chronic HFrEF to reduce morbidity and mortality. 2. ACE inhibitors should be started at low doses and titrated upward to doses shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in clinical trials. 3. ARBs should be started at low doses and titrated upward, with an attempt to use doses shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in clinical trials. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for optimization of heart failure treatment (10) 1. After a diagnosis of heart failure is made, GDMT should be initiated and therapies should be adjusted no more frequently than every 2 weeks to target doses (or maximally tolerated doses). 2. To achieve the maximal benefits of GDMT in patients with chronic HFrEF, therapies must be initiated and titrated to maximally tolerated doses (33,45,60,67). | |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; EHR, electronic health record; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; HFSA, Heart Failure Society of America; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and PM, performance measure.

SHORT TITLE: PM-9 Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

PM-9: Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤35% who are NYHA class II through class IV despite attempts at treatment with beta blockers and ACE inhibitors, ARB, or ARNI | |

| Numerator | Patients who were prescribed* MRA either within a 12-mo period when seen in the outpatient setting or at hospital discharge *Prescribed may include:

|

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with a current or prior LVEF ≤35% who are NYHA class II-IV despite attempts at treatment with beta blockers and ACE inhibitors, ARB, or ARNI, and have Cr ≤2.5 mg/dL for men and ≤2.0 mg/dL for women (or estimated glomerular filtration rate >30 mL/min/1.73 m2) and K <5.0 mEq/L |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not prescribing MRA therapy Documentation of patient reason(s) for not prescribing MRA therapy |

| Measurement Period | 12 mo |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient Inpatient |

| Rationale | |

| MRA therapy improves outcome in patients with heart failure and reduced LVEF (7). Use of MRA therapy in those without contraindications was 33% among 150 primary care and cardiology practices in the CHAMP-HF registry demonstrating a moderate to large treatment gap (20). | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. Aldosterone receptor antagonists (or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists) are recommended in patients with NYHA class II-IV HF and who have LVEF of 35% or less, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality. Patients with NYHA class II HF should have a history of prior cardiovascular hospitalization or elevated plasma natriuretic peptide levels to be considered for aldosterone receptor antagonists. Creatinine should be 2.5 mg/dL or less in men or 2.0 mg/dL or less in women (or estimated glomerular filtration rate >30 mL/min/1.73 m2), and potassium should be less than 5.0 mEq/L. Careful monitoring of potassium, renal function, and diuretic dosing should be performed at initiation and closely followed thereafter to minimize risk of hyperkalemia and renal insufficiency (54,71,72). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) 2. Aldosterone receptor antagonists are recommended to reduce morbidity and mortality following an acute MI in patients who have LVEF of 40% or less who develop symptoms of HF or who have a history of diabetes mellitus, unless contraindicated (73). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: B) | |

ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; CHAMP-HF, CHAnge the Management of Patients with Heart Failure; Cr, creatinine; EHR, electronic health record; HF, heart failure; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NYHA, New York Heart Association; and PM, performance measure.

SHORT TITLE: PM-10 Laboratory Monitoring in New Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Therapy (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

PM-10: Laboratory Monitoring in New Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist Therapy (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure who were started on MRA therapy and had potassium and renal function checked within 1 wk of the patient initiation of the MRA prescription | |

| Numerator | Patients who had potassium and renal function checked within 1 wk of the patient initiation of the MRA prescription |

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure who filled a new prescription for MRA therapy |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | None |

| Measurement Period | 12 mo |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient Inpatient |

| Rationale | |

| The major risk associated with use of aldosterone receptor antagonists is hyperkalemia attributable to inhibition of potassium excretion, ranging from 2% to 5% in trials (54,72,73) to 24% to 36% in population-based registries (74,75). The development of potassium levels >5.5 mEq/L (approximately 12% in EMPHASIS-HF (72)) should trigger discontinuation or dose reduction of the aldosterone receptor antagonist unless other causes are identified. The development of worsening renal function should lead to careful evaluation of the entire medical regimen and consideration for stopping the aldosterone receptor antagonist (7). Close monitoring of serum potassium is required; potassium levels and renal function are most typically checked in 3 d and at 1 wk after initiating therapy and at least monthly for the first 3 mo (Table 17, 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline (7)). Despite the known risk of hyperkalemia with MRA initiation, the rate of measurement of potassium levels within 2 wk of initiation is low (76). Although the clinical guideline suggests checking in 3 d, this is not a formal recommendation. Thus, the writing committee chose a more conservative 7-d time period to allow patient and provider flexibility and acknowledge challenges with weekend and holiday laboratory assessments. | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. Aldosterone receptor antagonists (or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists) are recommended in patients with NYHA class II-IV HF and who have LVEF of 35% or less, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality. Patients with NYHA class II HF should have a history of prior cardiovascular hospitalization or elevated plasma natriuretic peptide levels to be considered for aldosterone receptor antagonists. Creatinine should be 2.5 mg/dL or less in men or 2.0 mg/dL or less in women (or estimated glomerular filtration rate >30 mL/min/1.73 m2), and potassium should be less than 5.0 mEq/L. Careful monitoring of potassium, renal function, and diuretic dosing should be performed at initiation and closely followed thereafter to minimize risk of hyperkalemia and renal insufficiency (54,71,72). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) 2. Inappropriate use of aldosterone receptor antagonists is potentially harmful because of life-threatening hyperkalemia or renal insufficiency when serum creatinine is greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or greater than 2.0 mg/dL in women (or estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2), and/or potassium greater than 5.0 mEq/L (74,75). (Class 3, Harm, Level of Evidence: B) | |

ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; EHR, electronic health record; EMPHASIS-HF, Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization And SurvIval Study in Heart Failure; HF, heart failure; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NYHA, New York Heart Association; and PM, performance measure.

SHORT TITLE: PM-11 Hydralazine/Isosorbide Dinitrate Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction in Those Self-Identified as Black or African American (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

PM-11: Hydralazine/Isosorbide Dinitrate Therapy for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction in Those Self-Identified as Black or African American (Outpatient and Inpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure and a current or prior ejection fraction ≤40% who are self-identified as Black or African American and receiving ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI therapy and beta-blocker therapy who were prescribed a combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate | |

| Numerator | Patients who were prescribed* hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate or fixed dose combination of hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate within a 12-mo period when seen in the outpatient setting or at hospital discharge *Prescribed may include:

|

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure (NYHA class III or class IV) with a current or prior LVEF ≤40% who are self-identified as Black or African American and receiving ACEI, ARB, or ARNI, and beta-blocker therapy |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not prescribing hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate therapy Documentation of patient reason(s) for not prescribing hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate therapy |

| Measurement Period | Hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate therapy initiated within a 12-mo period of being seen in the outpatient setting or from hospital discharge |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient Inpatient |

| Rationale | |

| The combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate is recommended to improve outcomes for patients self-identified as African American or Black, who have moderate-to-severe symptoms on optimal medical therapy (7). Use of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate in self-identified African American or Black candidates for therapy has been suboptimal (77). | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. The combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate is recommended to reduce morbidity and mortality for patients self-described as African Americans with NYHA class III-IV HFrEF receiving optimal therapy with ACE inhibitors and beta blockers, unless contraindicated (78,79). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) | |

ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; EHR, electronic health record; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; and PM, performance measure.

SHORT TITLE: PM-12 Counseling Regarding Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Implantation for Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction on Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy (Outpatient Setting)

PM-12: Counseling Regarding Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Implantation for Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction on Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy (Outpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with current LVEF ≤35% despite ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI and beta-blocker therapy for at least 3 mo who were counseled regarding ICD implantation as a treatment option for the prophylaxis of sudden death | |

| Numerator | Patients who were counseled* regarding ICD implantation as a treatment option for the prophylaxis of sudden death *Counseling should be specific to each individual patient and include documentation of a discussion regarding the risk of sudden and non-sudden death and the efficacy, safety, and risks of an ICD. This will allow patients to be informed of the risks and benefits of ICD implantation and better able to make decisions based on the valuation of sudden cardiac death versus other risks. |

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with current LVEF ≤35% despite ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI and beta-blocker therapy for at least 3 mo |

| Denominator Exclusions | Functional ICD in situ Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not providing counseling regarding ICD implantation as a treatment option for the prophylaxis of sudden death (e.g., significant comorbidities, limited life expectancy, up titration of medical therapy is ongoing with anticipated LVEF improvement) |

| Measurement Period | 12 mo |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient |

| Rationale | |

| ICDs prevent sudden death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias in select patients with HFrEF (7). However, frequent or inappropriate shocks from an ICD can lead to reduced quality of life. Patients may differ in the willingness to have an ICD implanted based on their preferences for quality and length of life. Given the significant risks and benefits of ICD implantation, eligible patients should be fully informed of this treatment option (7). Among 21,059 patients from 236 sites in the GWTG Registry, 23% received predischarge ICD counseling. Women were counseled less frequently than men, and racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive counseling than White patients (80). | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. ICD therapy is recommended for primary prevention of SCD to reduce total mortality in selected patients with nonischemic DCM or ischemic heart disease at least 40 days post-MI with LVEF of 35% or less and NYHA class II or III symptoms on chronic GDMT, who have reasonable expectation of meaningful survival for more than 1 year (81,82).† (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A) †Counseling should be specific to each individual patient and should include documentation of a discussion about the potential for sudden death and non-sudden death from HF or noncardiac conditions. Information should be provided about the efficacy, safety, and potential complications of an ICD and the potential for defibrillation to be inactivated if desired in the future, notably when a patient is approaching end of life. This will facilitate shared decision-making among patients, families, and the medical care team about ICDs (83). 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS ventricular arrhythmias and prevention of sudden cardiac death guideline (9) 1. Patients considering implantation of a new ICD or replacement of an existing ICD for a low battery should be informed of their individual risk of SCD and non-sudden death from HF or noncardiac conditions and the effectiveness, safety, and potential complications of the ICD in light of their health goals, preferences, and values (84–88). (Class 1, Level of Evidence: B-NR) | |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; EHR, electronic health record; GWTG, Get With The Guidelines; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HF, heart failure; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; HRS, Heart Rhythm Society; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PM, performance measure; and SCD, sudden cardiac death.

SHORT TITLE: PM-13 Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Implantation for Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction on Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy (Outpatient Setting)

PM-13: Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Implantation for Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction on Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy (Outpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with current LVEF ≤35%, LBBB, QRS duration ≥150 ms, NYHA class II,III, and IV, despite ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI and beta-blocker therapy for at least 3 mo who have undergone CRT implantation | |

| Numerator | Patients (meeting denominator criteria) who have undergone CRT implantation |

| Denominator | All patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure with current LVEF ≤35%, LBBB, QRS duration ≥150 ms, NYHA class II, III, and IV, despite ACE inhibitor, ARB, or ARNI and beta-blocker therapy for at least 3 mo |

| Denominator Exclusions | Heart transplant LVAD |

| Denominator Exceptions | Documentation of medical reason(s) for not undergoing CRT implantation (e.g., multiple or significant comorbidities, limited life expectancy) Documentation of patient reason(s) for not undergoing CRT implantation (e.g., refusal) |

| Measurement Period | 12 mo |

| Sources of Data | EHR data Administrative data/claims (inpatient or outpatient claims) Administrative data/claims expanded (multiple sources) Paper medical record |

| Attribution | Individual practitioner Facility |

| Care Setting | Outpatient |

| Rationale | |

| CRT has been shown to improve survival and symptoms among symptomatic patients with heart failure and LVEF ≤35%, LBBB, and QRS duration ≥150 ms (7). CRT implantation (not just counseling) is recommended as CRT improves both quantity and quality of life, unlike ICDs, where there is no symptomatic benefit. In the GWTG database from 2014, 26% of eligible patients had CRT in place, implanted, or prescribed (89). Women were less likely to receive CRT, and this disparity increased over time. Black patients were less likely than White patients to have CRT. | |

| Clinical Recommendation(s) | |

|

2013 ACCF/AHA heart failure clinical practice guideline (7) 1. CRT is indicated for patients who have LVEF of 35% or less, sinus rhythm, LBBB with a QRS duration of 150 ms or greater, and NYHA class II, III, or ambulatory IV symptoms on GDMT. (Class 1, Level of Evidence: A for NYHA class III/IV (90–93); Level of Evidence: B for NYHA class II (94,95)) | |

ACCF indicates American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACE, angiotensin–converting enzyme; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; EHR, electronic health record; GWTG, Get With The Guidelines; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; and PM, performance measure.

Quality Measures for Heart Failure

SHORT TITLE: QM-1 Patient Self-Care Education (Outpatient Setting)

QM-1: Patient Self-Care Education (Outpatient Setting)

| Measure Description: Percentage of patients age ≥18 y with a diagnosis of heart failure who were provided with self-care education during ≥1 visits within a 12-mo period | |