Abstract

The role of triglycerides (TG) in coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) is controversial. The objective of this study was to explore the relationship between TG levels and prognosis in COVID‐19 patients and investigate the factors that affect TG. COVID‐19 patients were divided into normal or high TG level groups. Their demographic data, medical history, signs and symptoms, laboratory results, and final clinical results were analyzed retrospectively. A total of 174 patients were included. TG level was 1.6 (interquartile range [IQR]: 1.1‒2.1) mmol/L for all patients; 2.2 (IQR: 1.8‒2.7) mmol/L and 1.1 (IQR: 1.0–1.3) mmol/L in the high TG and control groups, respectively. Overall, 29 patients (16.7%) died during hospitalization, including 19 (23.1%) in the high TG group and 10 (11.5%) in the control group (absolute survival difference, 2.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2%‐5.1%), log‐rank χ 2 = 5.7, and p = .017). Serum ferritin, C‐reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and interleukin‐10 (IL‐10) levels were significantly higher in the high TG group compared to the control group. Pearson correlation analysis showed that TG was positively correlated with fasting blood glucose, leukocyte, serum ferritin, LDH, CRP, and IL‐10 levels. Multiple regression showed that serum ferritin and IL‐10 levels affected the TG level (R 2 = .095). The TG level in COVID‐19 patients is correlated to serum ferritin and IL‐10 levels, which reflects the activation of macrophages. It is suggested that COVID‐19 patients be monitored for elevated TG as both a prognostic indicator and potential therapeutic target for COVID‐19.

Keywords: COVID‐19, IL‐10, inflammation, macrophage, prognosis, serum ferritin, triglycerides

The triglycerides (TG) level in coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) patients is correlated to serum ferritin and IL‐10 levels, which reflects the activation of macrophages. It is suggested that COVID‐19 patients be monitored for elevated TG as both a prognostic indicator and potential therapeutic target for COVID‐19.

1. BACKGROUND

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19), is highly contagious and has resulted in a global pandemic that is causing significant damage to public health. The elderly and people with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and low immune function are more likely to have severe COVID‐19. 1

Some COVID‐19 patients have high triglyceride (TG) levels.2, 3 A comprehensive untargeted metabolomic and lipidomic approach has shown that TG levels are well‐correlated to the severity of the disease. 4 Research by Ehrlich et al. showed that elevated lipid metabolism may underline aspects of COVID‐19 pathogenesis, as fenofibrate reverses the metabolic changes induced by SARS‐CoV‐2, blocking viral replication. 5 On the contrary, research by Wang et al. showed a negative correlation between serum TG levels and the time from disease onset to positive‐to‐negative transmission (PTNT) in nucleic acid tests. This prompted the authors to suggest that patients with COVID‐19 receive high‐fat diets to increase serum TG levels and decrease the PTNT. 6

However, the role of TG in COVID‐19 is still unclear. Therefore, we retrospectively studied the characteristics of patients with different TG levels and analyzed the factors that affect TG levels, to preliminarily understand the pathophysiological mechanism of TG in COVID‐19.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients

Overall, 186 patients were diagnosed with COVID‐19 from February 9, 2020 to February 29, 2020 in three wards of Wuhan Tongji Hospital, China. All patients were confirmed positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleic acid by quantitative reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction. To avoid the effect of drugs on TG levels, 12 patients were excluded (one case was treated with hydroxychloroquine for chronic systemic lupus erythematosus, six cases were treated with statins, and six cases were treated with lopinavir and ritonavir tablets). Thus, 174 patients were included in the study. According to “The Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report,” 7 patients with TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L were included in the study and divided into two groups, high TG group (n = 78) and control group (n = 96). Information for all patients was retrospectively collected through the electronic medical record system, and included demographic characteristics, medical history, symptoms and signs, laboratory test results, SaO2 at the time of admission without oxygen, and final clinical outcomes. Laboratory examination during the course of the disease showed leukocyte and lymphocyte levels were at their minimum values and TG, serum ferritin, C‐reactive protein (CRP), interleukin (IL), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, creatine kinase, and fasting blood glucose levels were at their maximum values. Laboratory tests were carried out early morning in a fasted state, while the examination frequency was subject to disease changes throughout hospitalization. A total of 132 patients were tested for HbA1c, and no glucocorticoid drugs were used before the test. The diagnosis and treatment of COVID‐19 were based on the “New Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Program (Trial Seventh Edition)” 8 by the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Comorbidities were treated according to the corresponding guidelines. Nonsurvivors and a small number of survivors used antibacterial drugs and glucocorticoids. All patients had good compliance with the treatment. All patients were followed up until April 6, 2020. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University People's Hospital (No. 2020PHB110‐01), China.

2.2. Statistical analyses

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). One‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to calculate the difference between groups for continuous variables that fit normal distribution, and non‐parametric tests were used for non‐normally distributed continuous variables. The χ 2 test was applied to categorical variables. The log rank test was used for survival analysis to test the null hypothesis of no difference between the two groups. Simple regression and multiple linear regression were used to analyze the factors that affect TG. A value of p < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM).

3. RESULTS

The demographic baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1 and laboratory test data are shown in Table 2. All 174 patients enrolled in the study tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA. The patients had a median age of 66 (IQR: 54.7–72.0, range: 24–95) years, and a male to female ratio of 88/86. A total of 117 patients (67.2%) had comorbidities, among which hypertension (46.0%) was the most common, followed by diabetes (29.3%), and cardio‐cerebrovascular disease (17.2%). Eleven (6.3%) patients who received chronic hemodialysis for Stage 5 chronic kidney disease were infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 and received intermittent renal replacement therapy at the bedside (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of COVID‐19 patients

| Number (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total (n = 174) | High TG (n = 78) | Control (n = 96) | p‐value |

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 66.0 (54.7–72.0) | 63.0 (50.0–69.0) | 67.0 (57.0–73.0) | .151 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 88 (50.6) | 35 (44.9) | 53 (55.2) | .223 |

| Female | 86 (49.4) | 43 (55.1) | 43 (44.8) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 51 (29.3) | 27 (34.6) | 24 (25.0) | .182 |

| Hypertension | 80 (46.0) | 34 (43.6) | 46 (47.9) | .467 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 30 (17.2) | 12 (15.4) | 18 (18.8) | .687 |

| Pulmonary disease | 14 (8.0) | 7 (9.0) | 7 (7.3) | .782 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 10 (5.7) | 3 (3.8) | 7 (7.3) | .515 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14 (8.0) | 5 (6.4) | 9 (9.4) | .581 |

| Maintenance hemodialysis | 11 (6.3) | 4 (5.1) | 7 (7.3) | .756 |

| Signs and symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 114 (65.5) | 53 (67.9) | 61 (63.5) | .631 |

| Cough | 113 (64.9) | 49 (62.8) | 64 (66.7) | .634 |

| Fatigue | 74 (42.5) | 34 (43.6) | 40 (41.7) | .878 |

| Shortness of breath | 110 (63.2) | 54 (69.2) | 56 (58.3) | .871 |

| Myalgia | 30 (17.2) | 12 (15.4) | 18 (18.8) | .687 |

| Diarrhea | 21 (12.1) | 9 (11.5) | 12 (12.5) | .999 |

| Medication | ||||

| Abidol tablets (200 mg t.i.d.) | 174 (100) | 78 (100) | 96 (100) | 1.000 |

| Methylprednisolone sodium succinate (1–2 mg/kg/d injection for 3–5 days) | 58 (33.3) | 28 (35.9) | 30 (31.3) | .523 |

| Lianhua Qingwen (4 capsules t.i.d.) | 171 (98.3) | 76 (97.4) | 95 (99.0) | .588 |

| Mortality | 29 (16.7) | 19 (23.1) | 10 (11.5) | .023 |

| %SaO2 on admission, median (IQR) | 95.0 (90.0–97.0) | 95.0 (88.5–97.2) | 95.0 (90.0–97.0) | .498 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; TG, triglycerides; t.i.d., three times a day.

Table 2.

Comparison of laboratory parameters of COVID‐19 patients

| Median (IQR) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Normal range | Total (n = 174) | High TG (n = 78) | Control (n = 96) | p‐value |

| TG (mmol/L) | <1.7 | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | <.001 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 4.11–6.05 | 5.7 (5.1–7.1) | 6.0 (5.3–7.9) | 5.6 (5.0–6.5) | .321 |

| HbA1c (%) | 4.0–6.0 | 6.4 (5.8–7.2) | 6.5 (6.0–7.4) | 6.2 (5.8–6.6) | .069 |

| Leukocytes (×109/L) | 3.5–9.5 | 5.0 (4.1–6.1) | 5.1 (4.3–6.5) | 4.9 (3.8–5.9) | .115 |

| Lymphocytes (×109/L) | 1.1–3.2 | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | .066 |

| Serum ferritin (µg/L) | 30.0–400.0 | 654.7 (348.5–1400.7) | 798.5 (391.4–2093.8) | 566.0 (291.8–1153.9) | .001 |

| CK (U/L) | <190 | 73.0 (47.0–128.0) | 77.5 (45.5–126.3) | 69.0 (48.0–136.0) | .774 |

| LDH (U/L) | 135.0–225.0 | 286.0 (234.8–425.8) | 302.0 (238.0–473.5) | 278.0 (234.0–373.0) | .042 |

| CRP (mg/L) | <1.0 | 31.0 (5.3–100.1) | 39.8 (4.6–140.8) | 27.9 (7.3–67.5) | .035 |

| IL‐1β (pg/mL) | <5.0 | 5.0 (5.0–5.0) | 5.0 (5.0–5.0) | 5.0 (5.0–5.0) | .727 |

| IL‐2 (U/mL) | 223.0–710.0 | 714.0 (440.0–714.0) | 775.5 (421.5–1267.5) | 658.0 (440.0–1140.0) | .281 |

| IL‐6 (pg/mL) | <7.0 | 15.3 (4.0–54.8) | 20.4 (4.5–101.9) | 13.0 (3.4–40.5) | .583 |

| IL‐8 (pg/mL) | <62.0 | 12.9 (6.7–29.4) | 10.8 (6.4–22.5) | 12.8 (7.3–28.6) | .056 |

| IL‐10 (pg/mL) | <9.1 | 5.0 (5.0–7.6) | 5.0 (5.0–10.3) | 5.0 (5.0–6.2) | .045 |

| TNF‐α (pg/mL) | <8.1 | 9.2 (6.1–13.7) | 9.2 (5.8–14.0) | 9.2 (6.4–13.7) | .577 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 0.0–15.0 | 34.5 (17.0–62.0) | 33.0 (20.0–58.0) | 35.0 (17.0–63.0) | .659 |

| Fbg (g/L) | 2.0–4.0 | 5.2 (4.2–6.5) | 5.2 (3.9–6.6) | 5.3 (4.3–6.5) | .899 |

Abbreviations: CK, creatine kinase; CRP, C‐reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Fbg, fibrinogen; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; IL, interleukin; IQR, interquartile range; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TG, triglycerides; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor‐α.

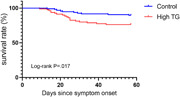

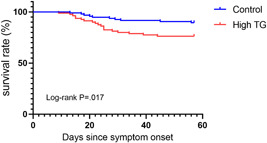

SaO2 without oxygen inhalation on admission was 95% (IQR: 90–97%) for all patients; 95.0% (88.5–97.2%) and 95.0% (90.0–97.0) in the high TG and control groups, respectively. There was no significant difference between the groups. Overall, 29 patients (16.7%) died during hospitalization, including 19 (23.1%) in the high TG group and 10 (11.5%) in the control group (absolute survival difference, 2.5% [95% CI: 1.2‐5.1%], log‐rank χ 2 = 5.7, and p = .017; Table 1 and Figure 1). All deceased patients were previously treated with mechanical ventilation.

Figure 1.

Comparison of survival rate between high TG group and control group. TG, triglycerides

Laboratory tests showed that the TG level was 1.6 (IQR: 1.1‒2.1) mmol/L for all patients; 2.2 (IQR: 1.8‒2.7) mmol/L and 1.1 (IQR 1.0–1.3) mmol/L in the high TG and control groups, respectively. Serum ferritin, LDH, CRP, and IL‐10 levels were significantly higher in the high TG group than in the control group (p < .05; Table 2).

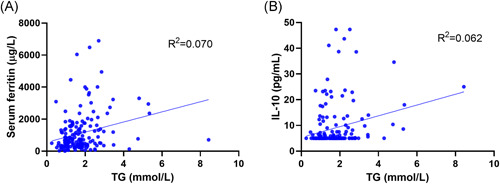

Pearson correlation analysis showed that the TG level was positively correlated with fasting blood glucose, leukocyte, serum ferritin, LDH, CRP, and IL‐10 levels (Table 3). To solve the problem of multicollinearity among related factors, we included them in multiple linear regression equations. The results showed that the factors influencing TG were serum ferritin and IL‐10 levels (R 2 = .095; Figure 2).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation analysis of TG in COVID‐19 patients

| Pearson's r | p‐value | |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting blood glucose | .156 | .043 |

| Leukocytes | .198 | .009 |

| Serum ferritin | .264 | .001 |

| LDH | .208 | .006 |

| CRP | .189 | .014 |

| IL‐10 | .249 | .001 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C‐reactive protein; IL‐10, interleukin‐10; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Figure 2.

Correlation between TG level and serum ferritin, and interleukin‐10 levels. TG, triglycerides

4. DISCUSSION

This study showed that patients with elevated TG levels had a higher mortality rate than those with normal levels. TG is degraded by lipoprotein lipase to produce free fatty acids, which can activate the nuclear factor‐κB pathway, leading to the high expression level of various proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐6, and monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1. 9 Elevated levels of triglyceride‐rich particles in the bloodstream may induce local inflammation and the activation of complement and coagulation cascades, ultimately promoting endothelial dysfunction.10, 11

In addition, TG may be related to the excessive activation of macrophages that causes the deterioration of COVID‐19 patients. In this study, regression analysis showed that TG levels were positively correlated with serum ferritin and IL‐10 levels. In the course of inflammatory diseases, infections, and malignant diseases, macrophages expressing CD163 obtain iron by clearing hemoglobin. As a result, the synthesis of ferritin in the cells increases, and its release into the blood also increases.12, 13 IL‐10 is derived from a variety of cells and is considered to be an inhibitor of inflammation and immunity. It can regulate the metabolism of macrophages by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1. 14 Many studies, including pathological studies, have shown that macrophage overactivation plays a key role in the inflammatory response and resulting organ damage in patients with severe COVID‐19.15, 16 Activated macrophages can inhibit lipoprotein lipase production to increase TG levels by releasing TNF‐α and IL‐1. 13 Therefore, we have reason to believe that the positive correlation between TG level, serum ferritin, and IL‐10 levels in patients with COVID‐19 may be due to macrophage activation, with the level of TG representing the degree of macrophage activation.

TG levels are affected by insulin resistance‐related diseases (such as type 2 diabetes and impaired fasting glucose), drugs, and diet. 7 Unfortunately, we did not evaluate insulin resistance by plasma insulin, HOMA‐R, and other indicators. We excluded familial hyperlipidemia, thereby also excluding the effects of hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, ritonavir, and lipid‐lowering drugs on TG, and 75.9% of the participants were tested for HbA1c. Pearson correlation analysis showed that the TG level was correlated with fasting blood glucose level (r = .156, p = .043) but multivariate regression analysis did not show this correlation.

4.1. Study strength and limitations

This study provides hints that TG metabolism is involved in the pathogenesis of COVID‐19 from a clinical perspective, suggesting that this approach can be targeted for prognosis and treatment. All the patients in this study were hospitalized before the global epidemic of COVID‐19. At that time, there was no effective intervention except oxygen therapy. The pathophysiological characteristics were more easily revealed in these patients as the natural progression of the disease could be analyzed in the absence of additional therapies. In other words, the lack of effective medication at the time presented with a unique opportunity in this small sample size retrospective research to reveal the relationship between TG and prognosis, serum ferritin, and IL‐10.

This study has limitations. First of all, this is a small sample size retrospective study conducted in a single geographical area Therefore, the results should be considered as preliminary findings. In particular, the small number of deaths leaves uncertainty whether elevated TG is an independent risk factor for death in COVID‐19 patients. Second, due to special circumstance, these patients could not be followed up long‐term outside the hospital. The follow‐up data is necessary to explore the relationship between inflammation and TG. Thus, larger trials with more prognostic indicators and long‐term follow‐up are needed to determine the relationship between TG and prognosis.

5. CONCLUSION

COVID‐19 patients with above normal TG levels have a higher mortality rate. The TG level in COVID‐19 patients is correlated to serum ferritin and IL‐10 levels, which reflects the activation of macrophages. It is suggested that COVID‐19 patients be monitored for elevated TG as both a prognostic indicator and potential therapeutic target for COVID‐19.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Peng Zhong and Zhenzhou Wang designed the study, wrote and revised the manuscript. Zhe Du reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical clearance for this study was granted by the Ethic Committee of Peking University People's Hospital. Because only the medical records were reviewed, this case series was exempted from signing the informed consent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the survey team members. This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Beijing municipality (7204321), Peking University People's Hospital Scientific Research Development Funds (2019‐02), and Youth Development Fund of Peking University School of Medicine (BMU2021PYB008).

Zhong P, Wang Z, Du Z. Serum triglyceride levels and related factors as prognostic indicators in COVID‐19 patients: a retrospective study. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2021;9:1055‐1060. 10.1002/iid3.469

Contributor Information

Zhenzhou Wang, Email: zhen_zhouwang@163.com.

Zhe Du, Email: drdz01@163.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data sets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934‐943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ouyang SM, Zhu HQ, Xie YN, et al. Temporal changes in laboratory markers of survivors and non‐survivors of adult inpatients with COVID‐19. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):20‐952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang Z, Du Z, Zhu F. Glycosylated hemoglobin is associated with systemic inflammation, hypercoagulability, and prognosis of COVID‐19 patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;164:108214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barberis E, Timo S, Amede E, et al. Large‐scale plasma analysis revealed new mechanisms and molecules associated with the host response to SARS‐CoV‐2. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(22):8623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ehrlich A, Uhl S, Ioannidis K, et al. The SARS‐CoV‐2 Transcriptional Metabolic Signature In Lung Epithelium. Social Science Electronic Publishing. 10.2139/ssrn.3650499 [DOI]

- 6. Wang L, Zhang Y, Cheng Y, et al. Serum triglyceride level and hypertension are highly associated with the recovery of COVID‐19 patients. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(10):6646‐6654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Cholesterol Education Program . NCEP Expert Panel on Detection E, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel I: Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143‐3421. [PubMed]

- 8. The Chinese novel coronavirus pneumonia diagnosis and treatment plan (trial version seven). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989.shtml. (Accessed May 2, 2021).

- 9. Boden G. Obesity, insulin resistance and free fatty acids. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18(2):139‐143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Twickler TB, Dallinga‐Thie GM, Cohn JS, Chapman MJ. Elevated remnant‐like particle cholesterol concentration: a characteristic feature of the atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype. Circulation. 2004;109(16):1918‐1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sullivan DR, Celermajer DS, Le Couteur DG, Lam CW. The vascular implications of post‐prandial lipoprotein metabolism. Clin Biochem Rev. 2004;25(1):19‐30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fardet L, Coppo P, Kettaneh A, Dehoux M, Cabane J, Lambotte O. Low glycosylated ferritin, a good marker for the diagnosis of hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1521‐1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michot JM, Hié M, Galicier L, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Rev Med Interne. 2013;34(2):85‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ip W, Hoshi N, Shouval DS, Snapper S, Medzhitov R. Anti‐inflammatory effect of IL‐10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science. 2017;356(6337):513‐519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Webb BJ, Peltan ID, Jensen P, et al. Clinical criteria for COVID‐19‐associated hyperinflammatory syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(12):e754‐e763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID‐19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):355‐362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.