Abstract

Background

Clustering of chronic conditions is associated with high healthcare costs. Sustaining blood pressure (BP) control could be a strategy to prevent high-cost multimorbidity clusters.

Objective

To determine the association between sustained systolic BP (SBP) control and incident multimorbidity cluster dyads and triads.

Design

Cohort study of Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) linked to Medicare claims.

Participants

ALLHAT included adults with hypertension and ≥1 coronary heart disease risk factor. This analysis was restricted to 5234 participants with ≥ 8 SBP measurements during a 48-month BP assessment period.

Main Measures

SBP control was defined as <140 mm Hg at <50%, 50 to <75%, 75 to <100%, and 100% of study visits during the BP assessment period. High-cost multimorbidity clusters included dyads (stroke/chronic kidney disease [CKD], stroke/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], stroke/heart failure [HF], stroke/asthma, COPD/CKD) and triads (stroke/CKD/asthma, stroke/CKD/COPD, stroke/CKD/depression, stroke/CKD/HF, stroke/HF/asthma) identified during follow-up.

Key Results

Incident dyads occurred in 1334 (26%) participants and triads occurred in 481 (9%) participants over a median follow-up of 9.2 years. Among participants with SBP control at <50%, 50 to <75%, 75 to <100%, and 100% of visits, 32%, 23%, 23%, and 19% of participants developed high-cost dyads, respectively, and 13%, 9%, 8%, and 5% of participants developed high-cost triads, respectively. Compared to those with sustained BP control at <50% of visits, adjusted HRs (95% CI) for incident dyads were 0.66 (0.57, 0.75), 0.67 (0.59, 0.77), and 0.51 (0.42, 0.62) for SBP control at 50 to <75%, 75 to <100%, and 100% of visits, respectively. The corresponding HRs (95% CI) for incident triads were 0.69 (0.55, 0.85), 0.56 (0.44, 0.71), and 0.32 (0.22, 0.47).

Conclusions

Among Medicare beneficiaries in ALLHAT, sustained SBP was associated with a lower risk of developing high-cost multimorbidity dyads and triads.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-06623-w.

KEY WORDS: hypertension, systolic blood pressure, multimorbidity, aging, blood pressure control

Older adults with multimorbidity, defined as ≥ 2 chronic conditions, require more healthcare services and have higher healthcare costs compared to those without multimorbidity.1,2 While the total number of chronic conditions a person has is associated with healthcare utilization, clustering of certain conditions may also affect outcomes and costs.3,4 For example, annual spending for a beneficiary with the dyad cluster of stroke and chronic kidney disease (CKD) is more than fivefold higher compared to the average Medicare beneficiary.5,6 A triad cluster that includes stroke, CKD, and asthma is associated with sevenfold higher spending.

In addition to healthcare costs, multimorbidity is also associated with outcomes that are important to older adults including functional decline and reduced quality of life.7,8 Therefore, identifying treatment approaches to prevent high-cost multimorbidity clusters is an important patient-centered goal. Among Medicare beneficiaries, the five costliest dyad and triad clusters all include one or more chronic conditions that can result from end-organ damage related to high blood pressure (BP) including stroke, heart failure (HF), and chronic kidney disease (CKD).5,6 Antihypertensive medication has been shown to lower BP and prevent stroke and HF, and slow the progression of CKD.9,10 By preventing one or more of these hypertension-related chronic conditions, controlling BP has the potential to reduce the incidence of costly dyad and triad clusters.

Sustaining BP control at a greater percentage of visits over time has been shown to be associated with a slower progression of multimorbidity, delaying the age of onset of six or more chronic conditions by 8 years.11 The percentage of visits at which patients achieve BP control can easily be calculated, could be used to guide discussions with patients about treatment goals, and could be used as a performance measure for quality improvement. The purpose of the current analysis was to determine the association between the percentage of visits with sustained BP control and incident high-cost multimorbidity cluster dyads and triads in an observational analysis of a large hypertension clinical trial.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) linked to Medicare health insurance claims (Fig. 1).11 ALLHAT enrolled men and women aged 55 years or older who had hypertension and at least one additional coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factor between 1994 and 1998.12,13 CHD risk factors in ALLHAT included history of a myocardial infarction, stroke, left ventricular hypertrophy, history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, current cigarette smoking, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) < 35 mg/dL, or documentation of other atherosclerotic CVD. Participants were randomized to receive amlodipine, lisinopril, doxazosin, or chlorthalidone. In December 1999, the doxazosin arm was terminated early and participants in this arm were not eligible for the current analysis.14 The analytic cohort used for the current analysis was selected from 19,888 ALLHAT participants who were randomized to receive amlodipine, lisinopril, or chlorthalidone and who had Medicare parts A and B coverage at any time between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2010 (Supplemental Figure 1). To allow for identification of high-cost multimorbidity clusters in both inpatient and outpatient settings, only participants with Medicare Parts A and B coverage were eligible for the current analysis. Medicare is a health insurance program for US adults who are 65 years of age and older, those who receive disability benefits, or those receiving care for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Medicare Part A provides insurance coverage for inpatient, skilled nursing facility, and home health and hospice care, and Part B provides insurance for outpatient care. ALLHAT participants with Medicare Advantage, a managed care program, were not included because claims for individuals with this coverage are not complete.

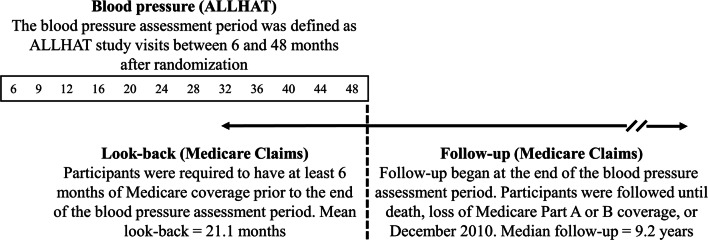

Figure 1.

Study design. Data from participants of the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) were linked to Medicare health insurance claims. ALLHAT data were used to determine sustained blood pressure (BP) control during the BP assessment period. Follow-up in Medicare claims began on the date corresponding to the end of the BP assessment period for each participant. The follow-up period was used to identify incident multimorbidity dyads and triads.

Among the 19,888 ALLHAT participants, we excluded 7685 participants who did not attend or have systolic BP (SBP) measurements at eight or more of the twelve ALLHAT visits during the BP assessment period, defined in the current analysis as study visits conducted between 6 and 48 months following randomization. Additionally, we excluded 1562 participants who died or had a nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or HF event prior to the beginning of follow-up because these events may impact BP or lead to changes in antihypertensive medication regimens and goals. We excluded an additional 4050 participants who did not have Medicare coverage in the six months prior to the beginning of follow-up to ensure that all participants had sufficient time to assess for prevalent chronic conditions in Medicare claims. For those with more than 6 months of Medicare coverage, all available claims prior to the beginning of follow-up were used (mean look-back period = 20.5 months).15 Lastly, we excluded 1357 participants with any of the individual chronic conditions included in the high-cost multimorbidity dyad or triad clusters prior to the beginning of follow-up (stroke, CKD, COPD, HF, asthma, or depression) resulting in a final analytic cohort of 5234 participants. This analysis of ALLHAT data was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Sustained Blood Pressure Control

BP was measured at each ALLHAT study visit which occurred every 3 months for the first 12 months after randomization, and then every 4 months thereafter through March 2002. Trained ALLHAT study staff followed a standardized protocol, measuring BP twice with a 30-s interval separation. The average of the two measures was calculated and used to define BP at each study visit. The BP goal in ALLHAT was an SBP <140 mm Hg and diastolic BP (DBP) <90 mm Hg. After excluding BP measurements obtained during the first three ALLHAT visits, we calculated the proportion of visits at which SBP was <140 mm Hg during the 6- to 48-month BP assessment period. BP measurements at baseline and 1 and 3 months following randomization were excluded because a high proportion of participants were having their antihypertensive medication titrated during this period. Sustained BP was defined based on SBP alone as isolated systolic hypertension is the most common form of hypertension among older adults and commonly targeted to reduce CVD outcomes in this population.16,17 Participants were categorized into four groups based on the proportion of visits with SBP <140 mm Hg: (1) less than 50%, (2) 50 to less than 75%, (3) 75 to less than 100%, and (4) 100% of visits. These categories were chosen as they are easy to calculate and may be more intuitive than estimates of mean SBP or visit-to-visit SBP variability. Therefore, sustained SBP control could be clearly communicated with patients and may provide a meaningful metric for reporting improvement over time.11,18

High-Cost Multimorbidity Clusters

High-cost multimorbidity clusters were defined a priori as the 5 condition clusters which have been previously reported to have had the highest mean Medicare fee-for-service per capita spending in 2010 (Text Box 1).5,6 The incidence of each individual chronic condition was defined by the presence of a claim indicating the participant received a service or treatment for the specific condition using ICD-9 codes available from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Chronic Conditions Warehouse and recommended by the CDC for defining multiple chronic conditions.19 The date of diagnosis was based on the first occurrence of an inpatient, skilled nursing facility, or home health claim, or the first occurrence of two or more outpatient claims. The incident date for the multimorbidity clusters was then defined as the date of occurrence of the second of any multimorbidity dyads or date of occurrence of the third condition for multimorbidity triads.

Text Box 1 High-cost multimorbidity dyads and triads. high-cost clusters defined as 5 conditions with highest mean per capita Medicare fee-for-service spending in 2010

| Dyads | Triads |

| 1. Stroke, chronic kidney disease | 1.Stroke, chronic kidney disease, asthma |

| 2. Stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2. Stroke, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| 3. Stroke, heart failure | 3. Stroke, chronic kidney disease, depression |

| 4. Stroke, asthma | 4. Stroke, chronic kidney disease, heart failure |

| 5. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease | 5. Stroke, heart failure, asthma |

Other Covariates

Information on other participant characteristics were obtained as part of ALLHAT data collection conducted before randomization.12 Age was calculated at the beginning of follow-up in Medicare claims. Race/ethnicity, sex, education level, and smoking status were obtained prior to randomization. Diabetes and hyperlipidemia were defined based on ICD-9 codes indicating a service or treatment for these conditions in Medicare claims prior to the beginning of follow-up. These covariates were chosen as known risk factors for several of the conditions included in the dyads and triads that commonly co-occur with hypertension. Diabetes and hyperlipidemia are known risk factors for CKD, HF, and stroke. Smoking history is a known CVD risk factor, as well as a risk factor for COPD and asthma.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics were calculated for participants overall and in each of the four categories of sustained BP control (<50%, 50 to <75%, 75 to <100%, and 100% of visits). We calculated the cumulative incidence for any high-cost multimorbidity dyad and triad by category of sustained BP control accounting for death as a competing event. Cox proportional hazards models were used to obtain hazard ratios (HRs) for the association of sustained SBP control with any high-cost dyad and triad, separately. For each participant, follow-up began on the date corresponding to the end of the BP assessment period. Time-to-event outcomes were censored upon death, loss of Medicare Part A or B coverage (e.g., enrollment in Medicare Advantage), or the end of Medicare follow-up (December 31, 2010). In the regression analysis, age at the beginning of follow-up, rather than follow-up time, was chosen as the time scale. With age as the time scale, estimation is conducted among participants with comparable age, not follow-up time. By comparing participants with observed study time at similar age, we account for age as a potential confounder.20,21 We conducted three progressively adjusted regression models. Model 1 included no covariates. Model 2 included sex, race, and education, and model 3 included sex, race, education and history of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking status at time of ALLHAT randomization as covariates. Also, we estimated the incidence of each of high-cost multimorbidity dyad and triad, separately, and repeated Cox proportional hazards models for each high-cost multimorbidity dyad and triad, separately. All analyses were performed with SAS Studio 9.4.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The mean age of ALLHAT participants included in the current analysis was 73.6 (standard deviation [SD]; 6.5) at the beginning of follow-up; 50.6% were non-Hispanic white, 28.2% non-Hispanic black, 13.5% Hispanic white, and 2.6% Hispanic black; and 43.7% were men. Overall, 29.7% had SBP control at <50% of visits, 29.5% at 50 to <75% of visits, 27.5% at 75 to <100%, and 13.2% had SBP control at 100% of visits. Characteristics overall and by percentage of visits with SBP <140 mm Hg are shown in Table 1. Participants with SBP control at a higher percentage of visits were younger and more likely to be men and have prevalent hyperlipidemia, and less likely to be non-Hispanic Black and have prevalent diabetes mellitus.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ALLHAT-Medicare Linked Participants, Overall and by Percentage of Visits with Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) < 140 mm Hg

|

Overall (n=5234) |

Percentage of visits with SBP < 140 mm Hg | p value | ||||

|

< 50% (n=1557) |

≥50 to <75% (n=1544) |

≥75 to <100% (n=1440) |

100% (n=693) |

|||

| Mean age (SD), years* | 73.6 (6.5) | 74.1 (6.5) | 73.9 (6.6) | 73.1 (6.4) | 72.5 (6.3) | <0.0001 |

| Race (n (%)) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2646 (50.6) | 759 (48.8) | 778 (50.4) | 750 (52.1) | 359 (51.8) | <0.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1474 (28.2) | 548 (35.2) | 431 (27.9) | 346 (24.0) | 149 (21.5) | |

| Hispanic white | 706 (13.5) | 113 (7.3) | 242 (15.7) | 220 (15.3) | 131 (18.9) | |

| Hispanic black | 136 (2.6) | 33 (2.1) | 33 (2.1) | 50 (3.5) | 20 (2.9) | |

| Other | 272 (5.2) | 104 (6.6) | 60 (3.9) | 74 (5.1) | 34 (4.9) | |

| Men (n (%)) | 2285 (43.7) | 607 (39.0) | 625 (40.5) | 711 (49.4) | 342 (49.4) | <0.0001 |

| Mean education level (SD), years | 11.0 (4.0) | 10.5 (4.0) | 11.1 (4.0) | 11.1 (4.0) | 11.3 (4.1) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n (%)) | 1738 (33.2) | 572 (36.7) | 503 (32.6) | 442 (30.7) | 221 (31.9) | 0.003 |

| Hyperlipidemia(n (%)) | 1769 (33.8) | 461 (29.6) | 527 (34.1) | 499 (34.7) | 282 (40.7) | <0.0001 |

| Current smoker** (n (%)) | 855 (16.3) | 241 (15.5) | 263 (17.0) | 234 (16.3) | 117 (16.9) | 0.67 |

*Age at the end of the BP assessment period

**Smoking status obtained at time of ALLHAT randomization

Incidence of High-Cost Multimorbidity Clusters

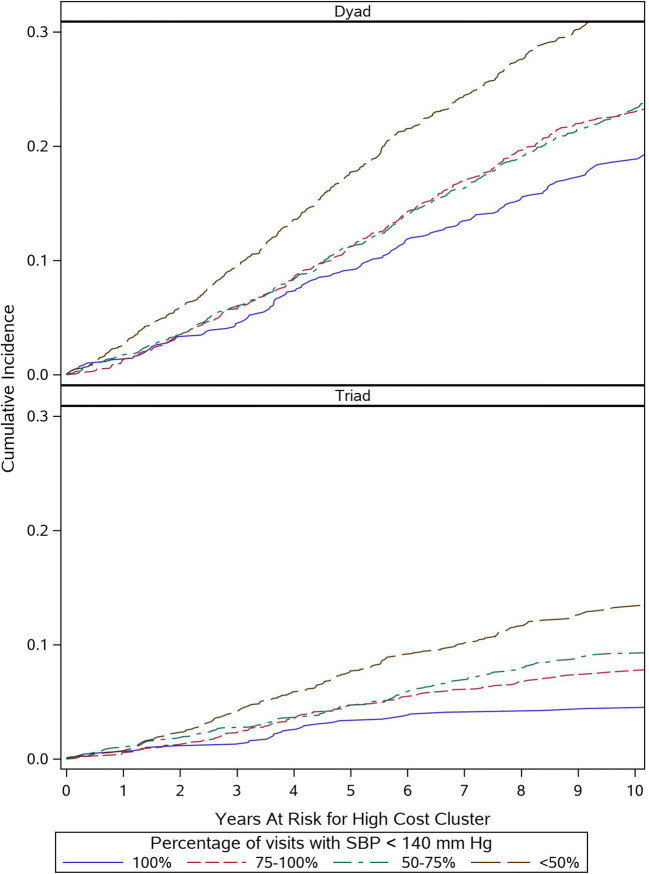

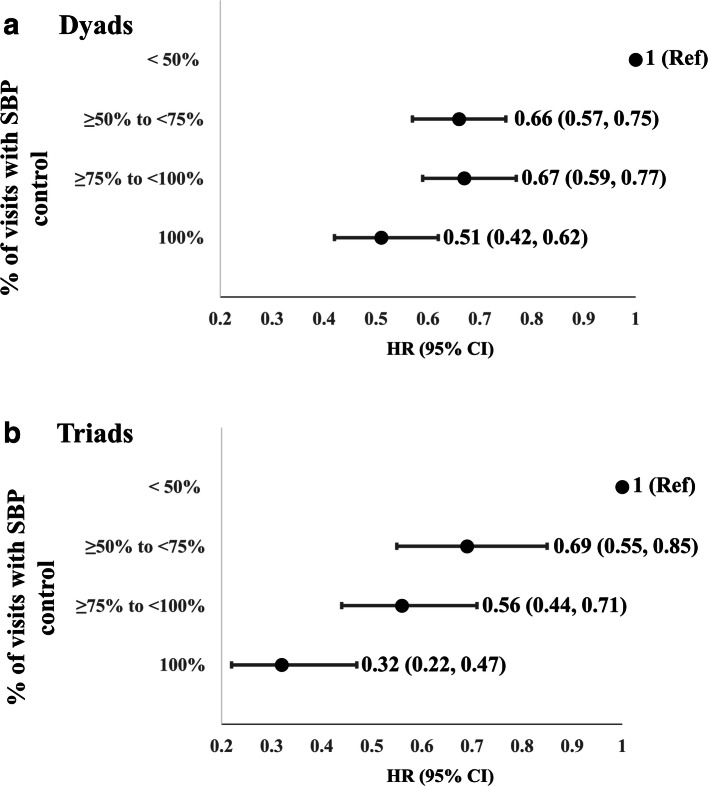

High-cost multimorbidity dyads occurred in 1334 (25.5%) and triads occurred in 481 (9.2%) of participants over a median follow-up of 9.2 years. The cumulative incidence of high-cost dyads and triads was lower among participants with controlled BP at a higher percentage of visits (Fig. 2). Compared to those with sustained BP control at <50% of visits, multivariable adjusted HRs (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) for the incidence of any high cost dyad were 0.66 (0.57, 0.75) for SBP control at 50 to <75%, 0.67 (0.59, 0.77) for SBP control at 75 to <100% of visits, and 0.51 (0.42, 0.62) for control at 100% of visits (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table 1). The corresponding HRs (95% CIs) for high-cost triads for greater SBP control were 0.69 (0.55, 0.85) for SBP control at 50 to <75%, 0.56 (0.44, 0.71) for SBP control at 75 to <100% of visits, and 0.32 (0.22, 0.47) for control at 100% of visits. The results of a subgroup analysis among non-smokers were consistent with the overall findings (results not shown).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of multimorbidity cluster dyads (a) and triads (b) relative to the start of Medicare follow-up.

Figure 3.

Multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for the development of high-cost multimorbidity dyads and triads by percentage of visits with systolic blood pressure control. Multivariable adjustment includes sex, race, education, history of diabetes and hyperlipidemia, and smoking status at time of ALLHAT randomization. N=5234. Additional models are displayed in Supplemental Table 1.

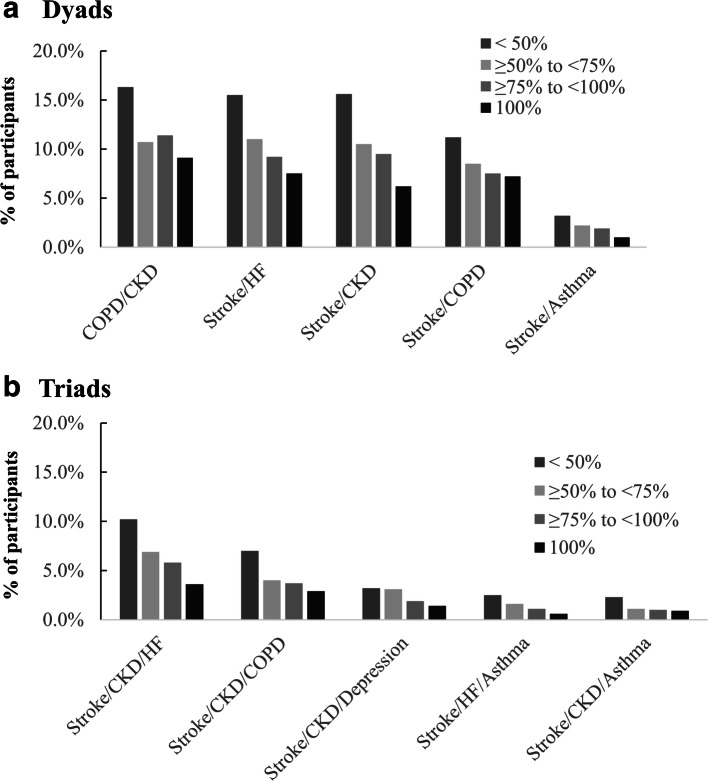

The incidence of individual high-cost dyads and triads was lower among participants with sustained BP control at a higher percentage of visits (Fig. 4; Supplemental Table 2). Multivariable adjusted HRs for the association between sustained BP control and each high-cost multimorbidity dyad and triad are displayed in Supplemental Table 3.

Figure 4.

Percentage of ALLHAT participants who developed each of the five high-cost multimorbidity cluster dyads (a) and triads (b) by level of sustained systolic blood pressure control during Medicare follow-up. CKD chronic kidney disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HF heart failure. N=5234.

DISCUSSION

Among ALLHAT participants with Medicare health insurance, sustained SBP was associated with a lower risk of developing high-cost multimorbidity dyads and triads. There was a graded pattern of lower risk for these multimorbidity clusters at a greater percentage of visits with SBP control. Therefore, maintaining SBP control at as many visits as possible, even if 100% control is not possible, may be a meaningful goal. The association between SBP control and multimorbidity was independent of age, race/ethnicity, sex, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking status. Although some multimorbidity clusters were more common than others, sustained SBP control was associated with a lower risk of each specific dyad and triad cluster assessed. Findings from the current study suggest that sustaining SBP control over time may be an effective strategy to prevent multimorbidity dyads and triads in older age. As antihypertensive medications are safe, effective, and inexpensive, sustaining SBP control among Medicare beneficiaries with hypertension may have the potential to reduce healthcare spending related to high-cost multimorbidity clusters.

Individual chronic conditions associated with high expenditures often result in a shift in care from outpatient settings to care provided in higher costs settings including hospitals and long-term care facilities.5 Additionally, these conditions often result in functional decline, limiting patients’ ability to self-manage chronic conditions and carry out activities of daily living.22,23 Stroke is an example of a condition in which patients often have high healthcare costs as well as high functional and caregiving needs.24–26 In the current analysis, stroke was included in the majority of dyads and triads we studied. In a prior analysis of ALLHAT follow-up data, compared to those with sustained BP control at <50% of visits, multivariable adjusted HRs (95% CI) for stroke were 0.83 (0.73, 0.94) for SBP control at 50 to <75%, 0.77 (0.66, 0.90) for SBP control at 75 to <100% of visits, and 0.72 (0.62, 0.83) for control at 100% of visits.18 Findings from the current study extend this prior finding to multimorbidity clusters that include potentially debilitating conditions such as HF, asthma or COPD, kidney disease, and depression. While it is unlikely that sustained BP control directly affects conditions such as depression or COPD, preventing hypertension-related chronic conditions would reduce the burden of multimorbidity clusters. As the need for high-cost care settings and functional support are highest among those with multiple chronic conditions, the benefit of sustained SBP control, which is an achievable goal for many patients, may be even greater than previously reported.

Findings from the current analysis provide additional information to support the importance of BP management in older adults. Recent hypertension treatment studies that have included older populations have focused on achieving predetermined BP goals. SBP control to 120 mm Hg versus 140 mm Hg has been shown to be associated with lower risk of CVD events, HF, incident mild cognitive impairment, and mortality.27–29 Additionally, current clinical practice guidelines recommend a SBP < 130 mm Hg.30 Less emphasis has been placed on the role of sustaining BP control over time. Among ALLHAT participants, maintaining an SBP < 140 mm Hg at <50%, 50 to <75%, 75 to <100%, and 100% of visits has been shown to correspond to mean SBP levels of approximately 150, 135, 130, and 125 mm Hg, respectively.18 The findings from the current study suggest that having sustained BP control is associated with lower risk for multimorbidity and that this may not be an “all-or-none” phenomenon in which treatment benefits only occur in those with SBP control at all visits. Therefore, supporting patients’ ability to maintain an SBP < 140 mm Hg at a higher percentage of visits may be one strategy to achieve recommended SBP goals and at the same time reduce the risk for multimorbidity. Describing BP in terms of percentage of visits controlled, rather than mean BP, may be easier to communicate with patients and may be a practical unit of measurement to target for improvement.

Findings from the current analysis also have implications for the triple aim of improving population health, aligning care with patients’ health goals, and reducing healthcare costs.31 There are currently 32 million US adults over the age of 65 years with hypertension.32 A recent analysis reported trends in BP control using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999–2000 until 2017–2018. Among US adults ≥ 75 years old, BP control increased over time, from 16.5% in 1999–2000 to 50.3% in 2013–2014. However, in the most recent calendar period, BP control among those ≥ 75 years old was only 36.5%, suggesting that renewed efforts to address BP among older adults are needed.33 Extending population health surveillance to measure BP control over time could be an approach to identifying and targeting those consistently above goal who are at risk for developing multimorbidity. Second, to better align treatment with patient health goals, findings from the current analysis could be used to support shared decision-making emphasizing the role of SBP in preventing multiple chronic conditions that impact function and quality of life.34 Additionally, we found disparities in SBP control by race. These findings are consistent with a prior ALLHAT study that investigated the associations of low median household income, Black race, and BP control. As multimorbidity is more common among Black US adults, improving SBP control may be a strategy for reducing disparities.35 Lastly, hypertension has been reported to be the most common chronic condition among Medicare beneficiaries with a prevalence of approximately 65%.5 Therefore, from a cost-saving perspective, even modest reductions in multimorbidity dyads and triads studied here may have the potential to reduce expenditures.

Several potential limitations of the current analysis should be considered. Although we used data from an existing clinical trial, this was an observational analysis. The association between the percentage of visits with SBP control and high-cost multimorbidity dyads and triads is likely related to participant factors in addition to SBP, such as health behaviors or physical activity that were not measured in ALLHAT or Medicare claims. A better understanding of the interaction between health behaviors, access and adherence to healthcare, and SBP control will be necessary to develop comprehensive treatment strategies to reduce multimorbidity. In order to have more precise estimates of SBP control and an adequate overlap between Medicare claims and ALLHAT SBP measures, we restricted the analyses to participants with 8 or more visits with SBP measurements during the BP assessment period, had 6 or more months of Medicare coverage during this time, and were free of prevalent high-cost conditions. Therefore, findings of the study may be generalizable to only healthier Medicare beneficiaries with treated hypertension. Furthermore, incident rates for the multimorbidity dyads and triads studied here have not been previously reported, making comparisons to the general Medicare population difficult. Despite these limitations that may affect the generalizability of the current findings, older adults taking antihypertensive medication remain a large population for which these findings may be relevant. In a separate analysis of publicly available data from the 2017–2018 cycle of NHANES, 33% of all Medicare beneficiaries ≥ 65 years of age met the ALLHAT criteria of hypertension plus one or more CHD risk factors.36 Lastly, diagnosis code-based definitions may result in underreporting of chronic conditions, especially early in the clinical course when conditions may be asymptomatic. Findings of lower risk of high-cost clusters may be limited to those with greater severity.

In conclusion, among ALLHAT study participants with Medicare health insurance, sustained SBP <140 mm Hg at a higher percentage of visits was associated with lower risk of developing the five costliest dyad and triad multimorbidity clusters. Having SBP control at a higher percentage of visits was associated with a lower risk for incident multimorbidity dyads and triads. By preventing high-cost multimorbidity dyads and triads, SBP control has the potential to reduce costs and improve health.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 33.1 kb)

Funding

Support was provided through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL133618) and the National Institute on Aging (R01AG062502) to C.B.B. This work was also supported by the Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (ADAPT), (CIN 13-410) at the Durham VA Health Care System.

Data Availability

The datasets can be requested through correspondence with the corresponding author and are available upon reasonable request to researchers who have the appropriate agreements with CMS and the ALLHAT coordinating center.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed here/in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:75–83. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2269–2276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowling CB, Plantinga L, Phillips LS, et al. Association of Multimorbidity with Mortality and Healthcare Utilization in Chronic Kidney Disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(4):704–711. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall RK, Zhou H, Reynolds K, Harrison TN, Bowling CBA. Novel Approach to Developing a Discordance Index for Older Adults With Chronic Kidney Disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(3):522–528. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions among Medicare Beneficiaries, Chartbook, 2012 Edition. Baltimore, MD. 2012.

- 6.Goodman RA, Ling SM, Briss PA, Parrish RG, Salive ME, Finke BS. Multimorbidity Patterns in the United States: Implications for Research and Clinical Practice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(2):215-220. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bowling CB, Deng L, Sakhuja S, Morey MC, Jaeger BC, Muntner P. Prevalence of Activity Limitations and Association with Multimorbidity Among US Adults 50 to 64 Years Old. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2390–2396. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makovski TT, Schmitz S, Zeegers MP, Stranges S, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity and quality of life: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;53:100903. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundstrom J, Arima H, Jackson R, et al. Effects of blood pressure reduction in mild hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2015;162(3):184–191. doi: 10.7326/M14-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowling CB, Sloane R, Pieper CF, et al. Association of sustained blood pressure control with multimorbidity progression among older adults J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Davis BR, Cutler JA, Gordon DJ, et al. Rationale and design for the Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) ALLHAT Research Group. American journal of hypertension. 1996;9(4 Pt 1):342–360. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(96)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):1967–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kent ST, Safford MM, Zhao H, et al. Optimal use of available claims to identify a Medicare population free of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(9):808–819. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin SS. Cardiovascular risks related to increased diastolic, systolic and pulse pressure. An epidemiologist's point of view. Pathol Biol (Paris). 1999;47(6):594–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franklin SS, Jacobs MJ, Wong ND, L'Italien GJ, Lapuerta P. Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle-aged and elderly US hypertensives: analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Hypertension. 2001;37(3):869–874. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.37.3.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowling CB, Davis BR, Luciano A, et al. Sustained blood pressure control and coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and mortality: An observational analysis of ALLHAT. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019;21(4):451–459. doi: 10.1111/jch.13515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, Parekh AK, Koh HK. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E66. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(1):72–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiebaut AC, Benichou J. Choice of time-scale in Cox's model analysis of epidemiologic cohort data: a simulation study. Stat Med. 2004;23(24):3803–3820. doi: 10.1002/sim.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowling CB, Sawyer P, Campbell RC, Ahmed A, Allman RM. Impact of chronic kidney disease on activities of daily living in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(6):689–694. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowling CB, Vandenberg AE, Phillips LS, McClellan WM, Johnson TM, 2nd, Echt KV. Older Patients' Perspectives on Managing Complexity in CKD Self-Management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(4):635–643. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06850616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for High-Need, High-Cost Patients - An Urgent Priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909–911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demaerschalk BM, Hwang HM, Leung G. US cost burden of ischemic stroke: a systematic literature review. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(7):525-533. [PubMed]

- 26.Dhamoon MS, Longstreth WT, Jr, Bartz TM, Kaplan RC, Elkind MSV. Disability Trajectories Before and After Stroke and Myocardial Infarction: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(12):1439–1445. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SPRINT MIND Investigators for the SPRINT Research Group Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, et al. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(6):553–561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SPRINT Research Group Wright JT, Jr., Williamson JD, et al. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–2116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Adults Aged >/=75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2673–2682. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection. Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol; 2017. p. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health. and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muntner P, Carey RM, Gidding S, et al. Potential US Population Impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA High Blood Pressure Guideline. Circulation. 2018;137(2):109–118. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muntner P, Hardy ST, Fine LJ, et al. Trends in Blood Pressure Control Among US Adults With Hypertension, 1999-2000 to 2017-2018. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of Patient Priorities-Aligned Decision-Making With Patient Outcomes and Ambulatory Health Care Burden Among Older Adults With Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Shahu A, Herrin J, Dhruva SS, et al. Disparities in Socioeconomic Context and Association With Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Outcomes in ALLHAT. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(15):e012277. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, [2020] [https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 33.1 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets can be requested through correspondence with the corresponding author and are available upon reasonable request to researchers who have the appropriate agreements with CMS and the ALLHAT coordinating center.