Abstract

Background

In 2019, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) incorporated the terminology “shared clinical decision-making” (SDM) into recommendations for two adult vaccines.

Objective

To assess among general internal medicine physicians (GIMs) and family physicians (FPs) nationally (1) attitudes about and experience with ACIP SDM recommendations, (2) knowledge of insurance reimbursement for vaccines with SDM recommendations, (3) how SDM recommendations are incorporated into vaccine forecasting software, and (4) physician and practice characteristics associated with not knowing how to implement SDM.

Design

Survey conducted in October 2019–January 2020 by mail or internet based on preference.

Participants

Networks of GIMs and FPs recruited from American College of Physicians (ACP) and American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) who practice ≥ 50% in primary care. Post-stratification quota sampling performed to ensure networks similar to ACP and AAFP memberships.

Main Measures

Responses on 4-point Likert scales (attitudes/experiences), true/false options (knowledge), and categorical response options (forecasting). Multivariable modeling with outcome of “not knowing how to implement SDM” conducted.

Key Results

Response rate was 64% (617/968). Most physicians strongly/somewhat agreed SDM requires more time than routine recommendations (90%FP; 95%GIM, p = 0.02) and that they need specific talking points to guide SDM discussions (79%FP; 84%GIM, p = NS). There was both support for SDM recommendations for certain vaccines (81%FP; 75%GIM, p = 0.06) and agreement that SDM creates confusion (64%FP; 76%GIM, p = 0.001). Only 41%FP and 43%GIM knew vaccines recommended for SDM would be covered by most health insurance. Overall, 38% reported SDM recommendations are displayed as “recommended” and 23% that they did not result in any recommendation in forecasting software. In adjusted multivariable models, GIMs [risk ratio 1.44 (1.15–1.81)] and females [1.28 (1.02–1.60)] were significantly associated with not knowing how to implement SDM recommendations

Conclusions

To be successful in a primary care setting, SDM for adult vaccination will require thoughtful implementation with decision-making support for patients and physicians.

KEY WORDS: shared decision-making, vaccination, ACIP

INTRODUCTION

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is a federal advisory committee charged with developing recommendations for vaccines for US civilian populations.1 ACIP has used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) process since 2010 in order to systematically evaluate the quality of evidence related to particular recommendations, the values and preferences of the people affected, and the balance of health benefits and risks.2 In 2018, ACIP expanded the GRADE process to include the use of Evidence to Recommendation frameworks to elucidate additional factors considered in vaccine recommendations, including implementation considerations, and to facilitate transparency, consistency, and communication of recommendations.3 In the recent past, two categories of vaccination recommendations had been stipulated: category A recommendations (also called “routine”) were made for all persons in an age- or risk-based group and category B recommendations (also called “permissive”) were made for individual clinical decision-making. The category B recommendation was previously used only for hepatitis B vaccination in adults ≥ 60 years of age with diabetes mellitus4 and for serogroup B meningococcal (MenB) vaccination in adolescents and young adults.5 More recently, in June of 2019, ACIP incorporated the term “shared clinical decision-making” into new recommendations for the use of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in adults 27–45 years of age and the use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) among immunocompetent patients ≥ 65 years of age.6,7 The change in terminology was intended to clarify the intent of previous category B recommendations rather than a change in the intended policy. This terminology has now been extended to the use of MenB for adolescents and young adults and the use of hepatitis B vaccine for adults 60 years and older with diabetes mellitus.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the key difference between the current “routine,” “catch-up,” and “risk-based” recommendations compared to shared clinical decision-making recommendations is that the default should be to vaccinate based on indication for the first three.8 In contrast, the decision about whether or not to vaccinate based on a shared clinical decision-making recommendation should be “informed by the best available evidence of who may benefit from vaccination; the individual’s characteristics, values, and preferences; the health care provider’s clinical discretion; and the characteristics of the vaccine being considered.”8

The use of the category “shared clinical decision-making” (abbreviated as SDM) by ACIP in their recommendations for adult vaccines is new, while at the same time SDM is a term that has been used in the context of many other types of decisions in adult care in recent years. Previous literature has identified substantial physician knowledge gaps about the benefits and risks of specific adult vaccines9–12 as well as lack of familiarity with SDM13 in general which may pose barriers to implementation of SDM for adult vaccination. Therefore, we sought to assess among nationally representative samples of general internal medicine providers (GIMs) and family physicians (FPs) (1) attitudes about and experience with ACIP SDM recommendations for vaccination; (2) knowledge of insurance reimbursement for vaccines with SDM recommendations; (3) how SDM recommendations are being incorporated into vaccine forecasting software (automated process for determining the recommended vaccinations needed for an individual) in electronic health records (EHRs); and (4) provider and practice characteristics associated with reporting not knowing how to implement SDM as intended by ACIP.

METHODS

From October 2019 to January 2020, we administered surveys to national networks of GIMs and FPs who had previously agreed to participate in surveys about vaccine policy issues. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this study as exempt research.

Study Setting and Population

We surveyed members of networks of GIMs and FPs recruited from the memberships of the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) as part of the Vaccine Policy Collaborative Initiative, a rapid survey mechanism to assess physician attitudes about vaccine policy issues. Physicians were eligible if they spent ≥ 50% of their time in primary care practice. To facilitate rapid responses, networks representing the membership of the ACP and AAFP were established prior to the implementation of this survey using a quota sampling approach in which we invited approximately 4000 randomly selected physicians from each organization to participate in the network for a 2-year period. Upon acceptance of the invitation to participate, physicians were placed into cells representing the distribution of physicians by US region, practice geographic location, and type of practice until quotas were achieved. Pre-recruitment in this manner allows surveys to be conducted rapidly and with a higher response rate because participants are familiar with the research organization and are anticipating the survey request. We have previously demonstrated that survey responses from network physicians are similar to those of physicians randomly sampled from American Medical Association comprehensive physician databases with respect to reported demographic characteristics, practice attributes, and attitudes about vaccination issues.14 Networks15 are re-recruited every 2 years using the same mechanism, thereby ensuring they continue to reflect characteristics of the relevant national organization. Further information about the rationale and methodology for our approach is available from previous publications.14,15

Survey Design

We designed the survey in collaboration with CDC content experts and with input from a survey expert (co-author L.C.) using question formats used in multiple previously fielded surveys with minor modifications to reflect the specific subject of this survey. A national advisory panel of 3 ACP members and 4 AAFP physicians pre-tested and provided feedback on the survey, and modifications were made to ensure comprehension and face validity of questions. The survey was then pilot tested among 70 GIMs and FPs and modified further based on examination of response distributions. We used 4-point Likert scales (strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree) to assess physicians’ attitudes about and experience with ACIP SDM recommendations in general (without respect to any specific vaccine). Questions about provider knowledge of insurance coverage offered “true,” “false,” and “don’t know” response options. We provided categorical response options regarding how SDM recommendations are incorporated into forecasting software in EHRs.

Survey Administration

Depending on physician preference, the survey was administered through the Internet or via US mail. We sent the Internet group an initial e-mail with up to 8 e-mail reminders and the mail group an initial mailing and up to 2 additional mail reminders. Non-respondents in the Internet group were also sent up to 2 mail surveys in case of problems with e-mail. Because initial GIM response rates were low, all GIM non-respondents received one additional mailed survey in a hand-written envelope. We patterned the administration protocol on Dillman’s Tailored Design Method16 which recommends multiple contacts with replacement questionnaires and variation of contact methods to achieve a high response rate.

Statistical Analysis

We pooled Internet and mail surveys for analyses because studies have found that physician attitudes are similar when obtained by different methods.16–18 We compared respondents with non-respondents using t tests or Wilcoxon’s tests for continuous variables, as appropriate, and Pearson’s chi-squared tests for categorical variables. When responses for both specialties were similar, combined results are presented, whereas when statistically significant differences existed, results are presented by specialty. A multivariable analysis was conducted with the outcome of strongly/somewhat agreeing with the statement “I do not know how to implement shared clinical decision-making as intended by the ACIP.” We used a log-binomial to calculate relative risks. Independent variables included characteristics of both physician (specialty, age, and gender) and practice (practice setting, census location, region of the country, level of decision-making regarding the purchasing and handling of vaccines for the practice, and number of providers in the practice). All variables were retained in the final multivariable model. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The overall response rate was 64% (617/968), 71% (336/474) among FPs and 57% (281/494) among GIMs. Overall, (Table 1) compared with non-respondents, respondents were more likely to be female (50% vs 38%), were on average 2 years younger, had a median of 6 vs 5 providers in their practice, and were more likely to be from a university, hospital, or public site (25% vs 17%).

Table 1.

Comparison of Respondents and Non-respondents and Additional Characteristics of Respondents and Their Practices

| Results by specialty | Total respondents vs non-respondents | p value, chi-square test, respondents vs non-respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | FP respondents (N = 336) | GIM respondents (N = 281) | Total respondents (N = 617) | Total non-respondents (N = 351) | |

| Provider gender, % (n) | |||||

| Female | 47 (158) | 54 (150) | 50 (308) | 38 (132) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 53 (176) | 46 (130) | 50 (306) | 62 (218) | |

| Mean (SD) provider age in years | 56.4 (8.0) | 52.8 (10.5) | 54.8 (9.4) | 56.7 (9.1) | 0.002* |

| Practice setting, % (n) | |||||

| Private practice | 59 (199) | 74 (209) | 66 (408) | 78 (270) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital or clinic | 29 (97) | 21 (58) | 25 (155) | 17 (58) | |

| HMO | 12 (39) | 5 (14) | 9 (53) | 5 (19) | |

| Practice location, % (n) | |||||

| Suburban | 62 (208) | 72 (199) | 67 (407) | 68 (236) | 0.19 |

| Urban | 36 (121) | 16 (45) | 27 (166) | 23 (81) | |

| Rural | 2 (7) | 12 (32) | 6 (39) | 9 (31) | |

| Practice region, % (n) | |||||

| South | 34 (115) | 31 (87) | 33 (202) | 36 (126) | 0.08 |

| Midwest | 26 (87) | 22 (63) | 24 (150) | 26 (93) | |

| West | 25 (84) | 23 (66) | 24 (150) | 17 (60) | |

| Northeast | 15 (50) | 23 (65) | 19 (115) | 21 (72) | |

| Practice-level decision-making, % (n) | |||||

| Larger system level | 52 (170) | 41 (115) | 47 (285) | 43 (149) | 0.28 |

| Independent | 48 (159) | 59 (165) | 53 (324) | 57 (196) | |

| Median (IQR) number of providers in practice | 6.0 (3.0–12.0) | 6.0 (3.0–12.0) | 6.0 (3.0–12.0) | 5.0 (2.0–10.0) | 0.002† |

| Proportion of privately insured patients in practice, % (n) | |||||

| 0–24 | 29 (92) | 18 (46) | 24 (138) | – | – |

| 25–49 | 32 (101) | 43 (113) | 37 (214) | – | – |

| ≥ 50 | 40 (127) | 39 (101) | 39 (228) | – | – |

| Proportion of Medicaid patients in practice, % (n) | |||||

| 0–24 | 78 (246) | 91 (235) | 84 (481) | – | – |

| 25–49 | 13 (41) | 7 (17) | 10 (58) | – | – |

| ≥ 50 | 9 (29) | 2 (6) | 6 (35) | – | – |

| Proportion of Medicare Part B patients in practice, % (n) | |||||

| 0–24 | 54 (166) | 32 (84) | 44 (250) | – | – |

| 25–49 | 34 (106) | 43 (111) | 38 (217) | – | – |

| ≥ 50 | 12 (38) | 25 (65) | 18 (103) | – | – |

| Patient race/ethnicity in practice, % (n) | |||||

| ≥ 10% Black/African American | 45 (146) | 55 (144) | 49 (290) | – | – |

| ≥ 10% Hispanic | 45 (146) | 48 (127) | 46 (273) | – | – |

| ≥ 10% Asian/Pacific Islander | 17 (55) | 29 (77) | 23 (132) | – | – |

FP family physician, GIM general internist, IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation

*t test

†Wilcoxon test

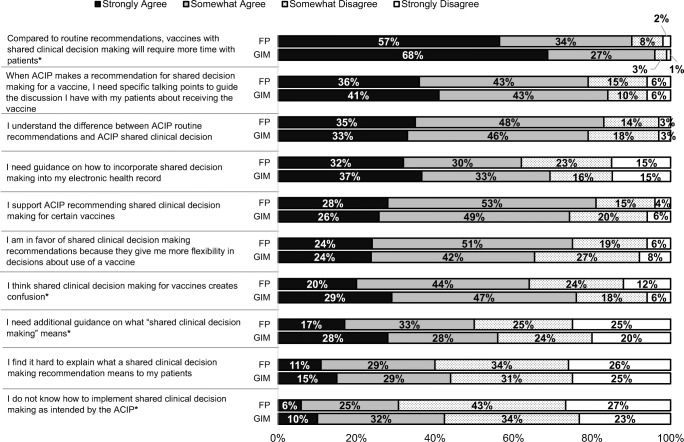

Attitudes about and Experience with ACIP SDM Recommendations

The vast majority of physicians strongly/somewhat agreed that SDM would require more time with patients than routine recommendations (90% of FPs and 94% of GIMs), that they need specific talking points to guide SDM discussions regarding vaccinations, and that they understand the difference between routine and SDM recommendations (Fig. 1). A majority (62% of FPs and 70% of GIMs) also strongly/somewhat agreed that they needed guidance on how to incorporate these types of recommendations into an EHR. There were somewhat contradictory responses about attitudes regarding SDM recommendations: for example, roughly similar response patterns were seen for support of SDM recommendations for certain vaccines and for agreeing that SDM recommendations for vaccines create confusion. Of note, GIMs were significantly more likely than FPs to agree that SDM would require more time with patients, that SDM creates confusion, that they need additional guidance on what SDM means, and that they do not know how to implement SDM as intended by ACIP.

Fig. 1.

How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements about ACIP recommendations for shared clinical decision about adult vaccinations in general? (FP n = 336, GIM n = 281). Some percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding. *p < 0.05 for comparison between specialties—GIM more likely to agree for all responses. FP = family medicine, GIM general internal medicine.

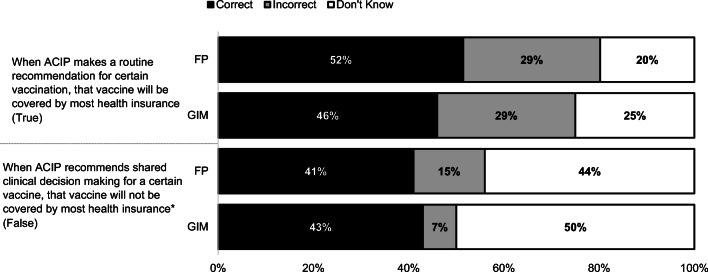

Knowledge of Insurance Reimbursement for Vaccines with SDM Recommendations

Roughly half of physicians in both specialties knew that when ACIP makes a routine vaccine recommendation for a particular vaccine, it will be covered by most health insurance; only 42% knew that this was also true for vaccines recommended for SDM and almost half of physicians reported not knowing the answer to this question (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Based on your current knowledge, please answer whether each of the following statements is true, false, or you don’t know. (FP: n = 336, GIM: n = 281). *p < 0.05 for comparison between FP and GIM. Some percentages do not add up to 100% due to rounding. FP family medicine, GIM general internal medicine.

Incorporation of SDM Recommendations into Vaccine Forecasting Software

Although 18% of respondents did not know how SDM recommendations are incorporated into forecasting software within their EHR, 38% reported that such recommendations are displayed as “recommended” while only 3% reported a specific prompt for a SDM conversation (Fig. 3). Almost a quarter reported that SDM recommendations do not result in a displayed recommendation at all.

Fig. 3.

When vaccination is based on shared clinical decision-making (example: serogroup B meningococcal vaccination of adolescents), how is this incorporated into the vaccine forecasting software in your electronic health record? (FP + GIM combined, n = 617). FP family medicine, GIM general internal medicine, EHR electronic health record.

Provider and Practice Characteristics Associated with Reporting Not Knowing How to Implement SDM

In adjusted multivariable models (Table 2), GIMs and female physicians were significantly more likely to report they did not know how to implement SDM recommendations as intended by ACIP. There was a trend for older physicians to be more likely to agree that they did not know how to implement SDM recommendations (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.00–1.13 per 5-year increase in age) but this had borderline statistical significance (p = 0.051).

Table 2.

Bivariable and Multivariable Associations with Agreeing That “I do not know how to implement shared clinical decision making as intended by the ACIP” (n = 600)

| Variable | Category | Strongly/somewhat disagree (N = 384) | Strongly/somewhat agree (N = 216) | Bivariable p value | Multivariable RR (95% CI) | Multivariable p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice specialty | FM | 60% (229) | 47% (101) | 0.002 | Ref. | 0.002 |

| GIM | 40% (155) | 53% (115) | 1.44 (1.15–1.81) | |||

| Provider gender | Female | 47% (178) | 54% (117) | 0.07 | 1.28 (1.02–1.60) | 0.03 |

| Male | 53% (204) | 46% (98) | Ref. | |||

| Provider age in years | 54.5 (9.2) | 55.4 (9.6) | 0.26 | 1.06 (1.00–1.13) per 5 years | 0.051 | |

| Practice setting | Hospital or clinic | 27% (103) | 21% (45) | 0.23 | 0.80 (0.59–1.05) | 0.22 |

| HMO | 9% (35) | 8% (18) | 1.08 (0.68–1.57) | |||

| Private practice | 64% (246) | 71% (152) | Ref. | |||

| Practice census location | Rural | 7% (26) | 6% (13) | 0.73 | 0.89 (0.53–1.33) | 0.22 |

| Urban-non-inner | 67% (258) | 65% (138) | Ref. | |||

| Urban-inner | 26% (99) | 29% (61) | 1.23 (0.95–1.56) | |||

| Practice region of country | Midwest | 24% (94) | 25% (54) | 0.61 | 0.86 (0.64–1.14) | 0.31 |

| Northeast | 19% (74) | 17% (37) | 0.79 (0.56–1.07) | |||

| South | 31% (119) | 36% (77) | Ref. | |||

| West | 25% (97) | 22% (48) | 0.78 (0.57–1.05) | |||

| Decision-making at practice | Independent | 52% (197) | 53% (114) | 0.79 | Ref. | 0.48 |

| Larger system level | 48% (181) | 47% (100) | 1.09 (0.86–1.36) | |||

| Number of providers in practice | 6.0 (3.0–13.0) | 6.0 (3.0–12.0) | 0.24* | 0.99 (0.96–1.00) per 5 providers | 0.18 |

RR risk ratio, Ref. referent group, HMO health maintenance organization, FP family physician, GIM general internist, CI confidence interval

*Wilcoxon test

DISCUSSION

This manuscript is the first to report attitudes and experiences of primary care physicians who care for adults regarding the terminology of ACIP vaccine recommendations based on shared clinical decision-making. Our findings demonstrate mixed reactions with the majority of physicians being supportive of such recommendations for certain vaccines, but also expressing concerns about them taking more time to discuss with patients, creating confusion for patients, and the need for specific talking points to guide their discussions with patients. Physicians also reported they need guidance about how to incorporate these recommendations into their clinical decision-making software. Nearly all currently report that their vaccine forecasting software does not generate a specific prompt for a shared decision-making conversation and close to 40% say that SDM recommendations currently display as “recommended.” Approximately one-third of physicians reported they do not know how to implement SDM for vaccinations.

Since our results reflect the attitudes of primary care physicians who address a broad range of health care issues, they should be understood in the context of how SDM has been incorporated into primary care practice as a whole. Shared decision-making was identified in the IOM 2001 report “Crossing the Quality Chasm”19 as a key mechanism for improving the quality of US health care. SDM requires a discussion of options about a particular medical decision as well as risks and benefits of different options with the incorporation of the patient’s preferences and values about the options before a shared decision is made between provider and patient.20 It has become common for professional societies and groups involved in generating screening and treatment guidelines to recommend SDM, and reimbursement from Medicare for certain procedures has been made contingent on SDM.21–23 However, although there is broad agreement about the importance of patient involvement in clinical decisions as a key tenet of “patient-centered care,”20 there is a great deal of variation in how shared decision-making is carried out. There is also considerable controversy about the type of decisions that rise to the level of importance to justify the SDM process.24 Much of the literature about SDM and evidence of its effectiveness25 revolves around the use of decision support tools or decision aids to guide discussions about preference-sensitive choices for decisions with major clinical or financial consequences. Examples of such decisions would include therapeutic decisions for various cancers, decisions regarding long-term medication use for prevention of coronary heart disease, decisions to use expensive radiological screening for lung cancer, or decisions about different surgical interventions. The use of decision aids to provide specific information on the options and outcomes relevant to a particular person’s health status has been shown to improve the quality of SDM, cause less decisional regret, and result in less confusion among patients when compared to reliance on the spoken word without a decision aid.25–27

It is not practical to engage in SDM for every decision that occurs in the course of a primary care visit24 and choices to engage in what are potentially lengthy SDM discussions mean that, in the course of a limited visit, other, potentially more important, issues can be neglected. Some28,29 have proposed that SDM behavior be modified based on the complexity of the decision29 or be reserved for decisions for which there is clinical equipoise30 or where patient preference is particularly relevant.31 A recent opinion piece argued that SDM in practice should be realized by greater specificity for decision choices in professional guidelines, the use of decision aids for consequential choices, and prioritizing decisions requiring SDM.24

Our data are consistent with previous SDM literature in identifying the additional time SDM will take as the most frequently endorsed concern on the part of physicians.13,28,32,33 The mean visit duration for an adult primary care visit is 21.6 min.34 Studies have demonstrated that the complexity of adult visits, as assessed by mean number of diagnoses, medications, and number of different clinical items discussed, has increased over time to a much greater extent than visit duration has, resulting in less available time to address any individual issue.34,35 Given the number of potential decisions to be made during a visit, it is not surprising that physicians need help in making SDM as efficient as possible. This is certainly reflected in our data by the 80% of our respondents who reported that when ACIP makes a recommendation for SDM for a vaccine, they need for specific talking points to guide the discussion they have with their patient about whether the patient should receive the vaccine. Decision aids are a central component of SDM but do not presently exist for the relevant adult vaccinations. Multiple previous surveys have demonstrated substantial physician knowledge gaps about specific adult vaccines9–12; decision aids could bridge this gap and reduce the time needed for discussion. In our study, substantial numbers of physicians reported needing additional guidance on what SDM means and how to explain it to patients as well as not knowing how to implement SDM, corresponding to previous literature demonstrating lack of self-efficacy or familiarity with SDM as major barriers to implementation of such recommendations.13

Our data also demonstrate that most physicians either do not know or are wrong about insurance coverage for different types of ACIP recommendations. A previous national survey of primary care physician demonstrated that when physicians think a vaccine is not covered, they are less likely to recommend it to patients, underlining the importance of improving physician knowledge of vaccine coverage.10

Importantly, a large percentage reported that their EHR forecasting software would indicate that a vaccination recommended for SDM would appear as a recommended vaccine without differentiation from a routine vaccine recommendation, potentially entirely circumventing the idea of SDM. Since practices may use standing orders allowing nurses or advanced practice providers to administer adult vaccinations without the involvement of a physician,36–38 even if physicians were aware of a SDM recommendation for a particular vaccine, they might not be involved in the decision to administer the vaccine. This has important implications for the implementation of SDM vaccine guidelines in the primary care setting.

Our data showed some significant differences between GIMs and FPs, with GIMs demonstrating higher levels of concerns about the additional time SDM could take, confusion it might cause to patients, and lack of understanding of what SDM means and how to implement it in practice. Concerns about time could be related to the higher level of complexity on average of patients seen by internists vs family physicians39 which could make them more reticent to add an additional SDM discussion to an already overburdened primary care visit. There may be a higher level of familiarity with SDM among FPs because they see higher proportions of adolescents and young adults and the MenB recommendations for “individual decision-making” have been active for this group for the past 5 years. There may also be training differences between the specialties related to how patient perspectives are incorporated into medical recommendations. Differences may also reflect different practice styles, which has been noted in other national surveys by our group.40,41 The gender differences we noted in level of comfort with implementation of SDM were unexpected and do not appear to be related to gender or age differences by specialty. Although many studies have described higher levels of adherence to clinical guides and provision of preventive care among female physicians, we are not aware of data directly related to comfort with implementation of SDM with which to compare our data.42–53

There are important strengths and limitations to these data. We surveyed large, nationally representative samples of GIMs and FPs and achieved high response rates. Nonetheless, responses of our sentinel physicians may not be fully generalizable. Previous work has demonstrated the survey methods described here yield similar responses to the most commonly employed method of sampling physicians nationally using the AMA Masterfile.14 Non-respondents may have different views than respondents, although our high response rates help to mitigate against this source of bias. Finally, our data are based on self-reported attitudes and experiences and may not reflect actual clinical practice.

Our data highlight the challenges SDM recommendations for adult vaccination pose for primary care physicians given the increasing expectations for SDM for multiple clinical decisions, the complexity of the patients they are seeing, and the limited time they have for primary care visits. Given the fact that physicians’ knowledge about changing vaccine recommendations, insurance coverage for vaccines with different types of recommendations, and the risks and benefits for patient subgroups is likely to be limited based on previous data from national surveys,9–12 the development of decision support tools for specific vaccine decisions will be important in guiding SDM vaccine discussions. Our data also emphasize the need for decision software to be aligned with SDM recommendations; if not aligned, such systems may default to either routine recommendations or indicate a vaccine is not recommended. Shared decision-making may be an important goal to strive for in primary care, but if it is a frequently used recommendation strategy for future vaccines, it will pose challenges for providers. To be feasible and successful in a primary care setting, SDM for vaccine use will require thoughtful implementation with decision-making support for patients and physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Amy Mullins, MD, and Bellinda Schoof, MHA, from the AAFP and Selam Wubu, MPH, and Darilyn Moyer, MD, from the ACP for collaborating in the establishment of the sentinel networks in family medicine and general internal medicine. We would also like to thank all family physicians and general internists in the networks for participating and responding to this survey.

Funding

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, grant 1U01IP000849-03. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation

None.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Walton LR, Orenstein WA, Pickering LK. The history of the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Vaccine. 2015;33(3):405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. GRADE Evidence Tables - Recommendations in MMWR. 2016; https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recs/GRADE/table-refs.html.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated Framework for Development of Evidence-Based Recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. 2018; https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6745a4.htm?s_cid=mm6745a4_w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of Hepatitis B Vaccination for Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). 2011; https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6050a4.htm. [PubMed]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of Serogroup B Meningococcal Vaccines in Adolescents and Young Adults: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. 2015; https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6441a3.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Adults: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6832a3.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine and 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6846a5.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP Shared Clinical Decision-Making Recommendations. 2020; https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/acip-scdm-faqs.html.

- 9.Hurley LP, Allison MA, Pilishvili T, et al. Primary Care Physicians’ Struggle with Current Adult Pneumococcal Vaccine Recommendations. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):94–104. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurley LP, Lindley MC, Allison MA, et al. Primary care physicians’ perspective on financial issues and adult immunization in the Era of the Affordable Care Act. Vaccine. 2017;35(4):647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurley LP, Allison MA, Dooling KL, et al. Primary care physicians’ experience with zoster vaccine live (ZVL) and awareness and attitudes regarding the new recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV) Vaccine. 2018;36(48):7408–7414. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurley LP, Lindley MC, Harpaz R, et al. Barriers to the Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccine. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(9):555–560. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravel K, Légaré F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:16–16. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crane LA, Daley MF, Barrow J, et al. Sentinel physician networks as a technique for rapid immunization policy surveys. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31(1):43–64. doi: 10.1177/0163278707311872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brtnikova M, Crane LA, Allison MA, Hurley LP, Beaty BL, Kempe A. A method for achieving high response rates in national surveys of U.S. primary care physicians. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Don A, Dillman JDS, Christian LM. Internet, Phone, Mail and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Desgin Method. 4. Hoboken: Wiley; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMahon SR, Iwamoto M, Massoudi MS, et al. Comparison of e-mail, fax, and postal surveys of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):e299–303. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkeson LR, Adams AN, Bryant LA, Zilberman L, Saunders KL. Considering Mixed Mode Surveys for Questions in Political Behavior: Using the Internet and Mail to Get Quality Data at Reasonable Costs. Polit Behav. 2011;33(1):161–178. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9121-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. 2001; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/ doi: 10.17226/10027.

- 20.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared Decision Making — The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merchant FM, Dickert NW, Jr, Howard DH. Mandatory Shared Decision Making by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for Cardiovascular Procedures and Other Tests. Jama. 2018;320(7):641–642. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knoepke CE, Allen LA, Kramer DB, Matlock DD. Medicare Mandates for Shared Decision Making in Cardiovascular Device Placement. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcome. 2019;12(7):e004899. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.004899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). 2015.

- 24.Beach MC, Sugarman J. Realizing Shared Decision-making in Practice. Jama. 2019;322(9):811–812. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(1):Cd001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Couët N, Desroches S, Robitaille H, et al. Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expect. 2015;18(4):542–561. doi: 10.1111/hex.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braaf S, Rixon S, Williams A, Lieu D, Manias E. Pharmacist-patient medication communication during admission and discharge in specialty hospital settings: implications for person centered healthcare. 2015;4(2):16.

- 28.Pieterse AH, Stiggelbout AM, Montori VM. Shared Decision Making and the Importance of Time. Jama. 2019;322(1):25–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braddock CH, III, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed Decision Making in Outpatient PracticeTime to Get Back to Basics. Jama. 1999;282(24):2313–2320. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitney SN, McGuire AL, McCullough LB. A Typology of Shared Decision Making, Informed Consent, and Simple Consent. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(1):54–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wennberg JE, O'Connor AM, Collins ED, Weinstein JN. Extending the P4P agenda, part 1: how Medicare can improve patient decision making and reduce unnecessary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(6):1564–1574. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):291–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD006732–CD006732. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao A, Shi Z, Ray KN, Mehrotra A, Ganguli I. National Trends in Primary Care Visit Use and Practice Capabilities, 2008-2015. Ann Family Med. 2019;17(6):538–544. doi: 10.1370/afm.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbo ED, Zhang Q, Zelder M, Huang ES. The increasing number of clinical items addressed during the time of adult primary care visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2058–2065. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0805-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bridges CB, Hurley LP, Williams WW, Ramakrishnan A, Dean AK, Groom AV. Meeting the Challenges of Immunizing Adults. Vaccine. 2015;33:D114–D120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modlin JBD, Clover R, et al. Use of Standing Orders Programs to Increase Adult Vaccination Rates. 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hurley L, Lindley MC, Allison MA, et al. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020. Room for Improvement: Primary Care Physicians’ Use of Evidence-Based Strategies to Increase Adult Vaccination Uptake. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Manns BJ, et al. Comparison of the Complexity of Patients Seen by Different Medical Subspecialists in a Universal Health Care System. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184852–e184852. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kempe A, Hurley LP, Cardemil CV, et al. Use of Immunization Information Systems in Primary Care. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(2):173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurley LP, Bridges CB, Harpaz R, et al. U.S. physicians’ perspective of adult vaccine delivery. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):161–161. doi: 10.7326/M13-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim C, McEwen LN, Gerzoff RB, et al. Is Physician Gender Associated With the Quality of Diabetes Care? Diabetes Care. 2005;28(7):1594–1598. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berthold HK, Gouni-Berthold I, Bestehorn KP, Böhm M, Krone W. Physician gender is associated with the quality of type 2 diabetes care. J Intern Med. 2008;264(4):340–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumhäkel M, Müller U, Böhm M. Influence of gender of physicians and patients on guideline-recommended treatment of chronic heart failure in a cross-sectional study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(3):299–303. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen MR, Urban N. Physician gender and screening: do patient differences account for differences in mammography use? Women Health. 1997;26(1):29–39. doi: 10.1300/J013v26n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frank E, Dresner Y, Shani M, Vinker S. The association between physicians’ and patients’ preventive health practices. CMAJ. 2013;185(8):649–653. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frank E, Harvey LK. Prevention advice rates of women and men physicians. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5(4):215–219. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.4.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franks P, Bertakis KD. Physician gender, patient gender, and primary care. J Women’s Health (2002) 2003;12(1):73–80. doi: 10.1089/154099903321154167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franks P, Clancy CM. Physician gender bias in clinical decisionmaking: screening for cancer in primary care. Med Care. 1993;31(3):213–218. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kruger J, Shaw L, Kahende J, Frank E. Health care providers’ advice to quit smoking, National Health Interview Survey, 2000, 2005, and 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E130. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lurie N, Slater J, McGovern P, Ekstrum J, Quam L, Margolis K. Preventive care for women. Does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;329(7):478–482. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308123290707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith AW, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. U.S. primary care physicians’ diet-, physical activity-, and weight-related care of adult patients. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Leary ST, Riley LE, Lindley MC, et al. Immunization Practices of U.S. Obstetrician/Gynecologists for Pregnant Patients. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(2):205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]