INTRODUCTION

The Shared Savings Program (SSP) is Medicare’s largest accountable care organization (ACO) initiative. Until recently, ACOs joining the SSP could select from four track options, each with varying levels of financial rewards and risk. Eighty percent chose Track 1, where they shared a small percentage of the savings with Medicare when they reduced their annual costs below a benchmark but were not penalized if they fell short.1 In an effort to increase financial accountability, Medicare launched “Pathways to Success” in December 2019, requiring current Track 1 ACOs to transition to downside risk in as little as 1 year.2,3 It is important to note that SSP participation is voluntary. Because many Track 1 ACOs may not be ready to take on the possibility of having to repay Medicare millions, they could opt to leave the SSP instead. Given that Track 1 ACOs generated over 90% of the net savings realized by the SSP last year, the program’s financial performance could suffer if a large exodus occurs.4

METHODS

To understand how ACO exit could affect SSP financial performance, we conducted an observational study. Using data from the SSP ACO Public Use File, we identified Track 1 ACOs that contracted with Medicare between 2012 and 2016. Next, we fit a multivariable logistic regression model to estimate an ACO’s odds of exiting the SSP from 2013 through 2017, adjusting for its leadership structure (obtained from the Leavitt Partners ACO Database), contract start date, number of aligned beneficiaries, and whether or not it ever earned a shared savings payment. We sorted these ACOs into deciles based on their predicted probability of SSP exit. For those that were still active in the SSP at the end of 2017, we fit a linear mixed model with random slopes to estimate an ACO’s spending as a function of time. We then predicted spending over years 2019 to 2022, assuming that the ACO remained in the SSP. To calculate SSP financial performance, we summed total savings for ACOs with predicted spending below their benchmark plus the sum of predicted spending above their benchmark for those that exceeded it. Finally, we recalculated SSP financial performance for a range of possible ACO exit rates.

RESULTS

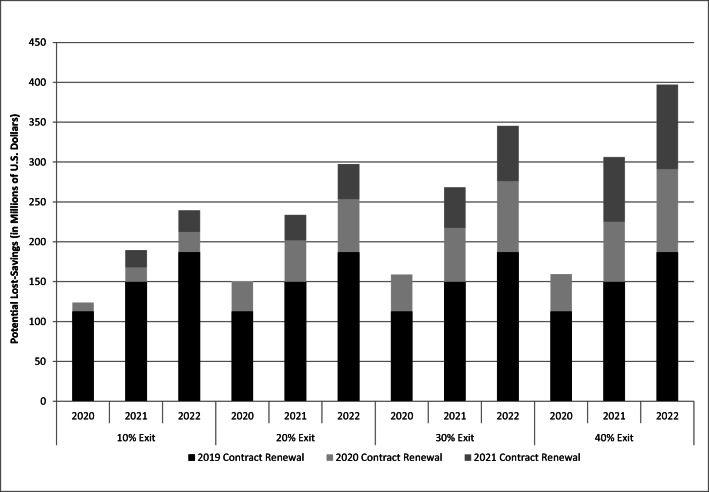

Of the 392 Track 1 ACOs that contracted with Medicare between 2012 and 2016, nearly 80% were still active at the end of 2016. Among the subset that faced contract renewal in 2019, 40% are known to have exited the SSP.5 Based on these organizations’ prior spending, Medicare stands to lose $75.8 million in savings during the first year after their exit. By 2022, Track 1 ACOs that exited in 2019 could cost the SSP $186.9 million in lost savings. In Figure 1, the lost savings from Track 1 ACOs that exited in 2019 are combined with projected lost savings from Track 1 ACOs facing contract renewal in 2020 and 2021 over a range of possible exit rates. If the exit rate observed in 2019 continues, the SSP could suffer $396.8 million in lost savings by 2022.

Figure 1.

. Potential savings lost to the SSP from Track 1 ACO exit. Estimated probability of exit calculated from logistic regression model (C-statistic = 0.824).

DISCUSSION

Our study highlights a potential unintended consequence of Medicare’s efforts to increase financial accountability in the SSP. While provocative, our study has several limitations. First and foremost, insofar as a participating organization is an ACO “in name only,” its exit would be good for the SSP. However, emerging data show meaningful engagement in care redesign among a substantial number of Track 1 ACOs. Second, some of the projected lost savings from exiting ACOs could be partly offset by organizations that remain if they are able to achieve greater efficiency. Third, exit rates in later years could be much lower than 40%, as organizations gain more familiarity with new SSP rules. Despite these limitations, our study has important policy implications. Care redesign (and the savings that result from it) takes time. Requiring Track 1 ACOs to take on risk too early in their accountable care journey could lead many of them to exit the SSP. In fact, survey results from the National Association of ACOs suggest that as many as 70% of SSP participants would rather exit the program than risk financial penalties.6 Such an exodus could not only hurt performance but also the older adults cared for by exiting ACOs.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 536 kb)

Funding

Dr. Hollingsworth is supported by AHRQ Grants R01HS024525 and R01HS024728 and NIA Grant 1R01AG068074.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nicholas M. Moloci, Email: nmoloci@umich.edu.

Yajuan Si, Email: yajuan@umich.edu.

Edward C. Norton, Email: ecnorton@umich.edu.

Andrew M. Ryan, Email: amryan@umich.edu.

John M. Hollingsworth, Email: kinks@med.umich.edu.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program. 2019 Shared Savings Program Fast Facts. 2019:2. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/ssp-2019-fast-facts.pdf. Accessed on Sept 14, 2019.

- 2.Verma S. Pathways To Success: A New Start For Medicare’s Accountable Care Organizations. Health Affairs Blog. 2018 (August 9, 2018).

- 3.Verma S. More ACOs Taking Accountability Under MSSP Through ‘Pathways To Success’ | Health Affairs. Health Affairs Blog. 2019.

- 4.Castellucci MDV. Medicare ACOs saved CMS millions, but many could drop out as the program gets retooled. Modern Healthcare 2018.

- 5.Chernew ME, de Loera-Brust A, Rathi V, McWilliams JM. MSSP Participation Following Recent Rule Changes: What Does It Tell Us? | Health Affairs. In. www.healthaffairs.org. Vol 2019. Health Affairs Blog 2019.

- 6.National Association of ACOs. Press Release May 2 2018. National Association of ACOs Web site. https://www.naacos.com/press-release-may-2-2018. Published 2018. Accessed Dec 10, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 536 kb)