Abstract

Background

Previous research showed acute psychedelic effects were associated with decreases in racial trauma (RT) symptoms among black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). Among samples comprised primarily of white participants, positive outcomes of psychedelic experiences have been mediated by increases in psychological flexibility. Therefore, we examined whether changes in psychological flexibility from before to after a psychedelic experience mediated the relationship between acute psychedelic effects and changes in RT symptoms among BIPOC.

Methods

This cross-sectional online survey study included 313 BIPOC (mean age = 33.1; SD = 11.2; female = 57%). A multiple linear regression analysis was used to examine the association between acute psychedelic effects and decreases in RT symptoms in a nonclinical setting; a path analysis was used to explore whether changes in psychological flexibility mediated this relationship.

Results

Acute insight and challenging effects were significantly (p < .001) associated with decreases in RT symptoms following a psychedelic experience. Increases in psychological flexibility partially mediated relationships between greater intensity of psychological insight and less intensity of challenging experiences and decreases in RT symptoms (ps<.001).

Conclusion

This research suggests psychedelics confer potential benefits in decreasing RT symptoms among BIPOC and psychological flexibility may be an important mediator of these effects. Future research should test this hypothesis in a longitudinal clinical trial among BIPOC.

Keywords: psychedelic, people of color, psychedelic experience, racial trauma, psychological flexibility

Introduction

Trauma and stressor-related disorders are a common mental health consequence following a traumatic event. 1 One form of trauma underrepresented in empirical investigations is racial trauma,2,3 defined as traumatization due to distressing experiences that can include physical or psychological threats to oneself or witnessing such threats to another based on race or ethnicity. 3 According to the US Department of Justice, many people of color (POC) have experienced some form of racial trauma in their lifetime. 4 The public health burden of trauma includes trauma symptoms that are significantly predicted by overt and subtle racial discrimination, 5 and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms or a PTSD diagnosis due to the cumulative effects of ongoing racial discrimination.6–8 Although several efficacious treatments exist for PTSD (eg, prolonged exposure 9 and cognitive processing therapy 10 ) existing treatment studies largely do not address the role of race or ethnicity. 11 Furthermore, evidence shows that treatment dropout rates are high among POC.12,13 Thus, the development of treatments for racial trauma is sorely lacking.

One emerging research area has examined the psychotherapeutic action of psychedelic compounds (eg, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD]). These substances have been administered in clinical trials14–17 and used in naturalistic settings18–20 as potential treatments for mental health problems. These substances act primarily as serotonin receptor (eg, 5-HT1A/2A/C) agonists, often producing profound changes in sensory perceptions, cognitions, behavior, and mood. 21 For example, recent clinical studies examining psychedelics administered with psychological support have demonstrated efficacy in decreasing symptoms of anxiety and depression,15,17,22–25 and several survey and observational studies have reported decreases in depression and anxiety occur following psychedelic use in ceremonial and recreational contexts.19,20,26,27 Although more research is needed, the beneficial effects of psychedelics appear to be associated with the intensity of acute subjective effects. For example, several published studies have shown the importance of the acute mystical-type (measured with the Mystical Experience Questionnaire [MEQ])28,29 and acute insight (measured with the Psychological Insight Questionnaire [PIQ] 30 ) in both healthy19,28,31,32 and clinical24,25,30,33,34 populations.

Although recent clinical trials have found positive effects of psychedelic-assisted therapy on mental health outcomes, samples are small and have lacked inclusion of POC. For example, out of 18 published randomized controlled trials on psychedelic-assisted therapy, the large majority of participants were non-Hispanic White (82%) with low percentages of POC (eg, 3% black; 2% Latina; 2% Asian; 5% Indigenous; 5% mixed race). 35 Although the lack of representation in these studies may have been related to lack of cultural inclusivity in the research community, stigma about mental health issues, or study recruitment methods, and the lack of POC in these studies substantially limits generalizability of findings. Because POC may also use licit and illicit substances to cope with the sequelae of racial trauma symptoms,36,37 they may seek out novel substances, including psychedelics, if they do not have access to empirically supported treatments or when those treatments have not been effective. Highlighting this phenomenon, a recent online survey study 21 examined how the use of psychedelics in the natural ecology affected subsequent psychopathology among a sample comprised solely of POC. Results showed significant and large reductions in the intensity of traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms from the 30 days before to the 30 days after a referent psychedelic experience. Additionally, there was a significant canonical correlation (Rc = 0.52, p < .001) between a dimension of the acute mystical-type and insight effects as well as acute challenging experiences (measured with the Challenging Experiences Questionnaire [CEQ] 38 ) and decreases in subsequent psychopathology.

Because the evidence presented above suggests that psychedelics can lead to beneficial outcomes when administered in clinical and naturalistic settings, and emerging evidence shows that psychedelic use is related to reductions in race-based trauma symptoms among POC, potential mediators of psychedelic effects on therapeutic outcomes could help increase understanding the mechanism underlying such effects. Previous studies suggest changes in the entropy of brain network connectivity, 39 the experience of awe/ego dissolution,40,41 and changes in psychological flexibility30,42–46 may mediate therapeutic outcomes following a psychedelic experience.

Psychological flexibility (measured by the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II [AAQ-II]47,48) is described as a set of psychological processes that help people manage stressors and engage in adaptive behaviors promoting value-driven action. 49 Thus, psychological flexibility is a transdiagnostic construct wherein people are believed to have the capacity to recognize and adapt to various contextual demands, shift their mindset or behaviors during individual and social experiences, maintain balance across important life domains, and learn to be open to, aware of, and committed to behaviors congruent with their values. 50 According to the model, well-being would be supported when an individual fully contacts the present moment as a conscious human, and changes or persists in value-driven behavior, despite negative feelings that may be present for them in each moment. 51 Conversely, dysfunctions in psychological functioning, including mental health problems such as race-based PTSD,6–8 could be theorized as the result of reduced psychological flexibility (or psychological inflexibility), in which individuals may struggle to maintain value congruent behavior in the face of challenging emotional responses related to past racial trauma. Importantly, psychological flexibility is a broad term that includes aspects of experiential avoidance, which is theoretically related to maladaptive responses to trauma through avoidance of thoughts and feelings related to the trauma. 1 Indeed, several PTSD symptom clusters (reexperiencing, avoidance, and physiological hyperarousal) have also been associated with higher AAQ-II scores (eg, Hosseini Ramaghani et al, 52 Meyer et al, 53 and Tull and Roemer 54 ), and thus, one could expect that symptoms of racial trauma and psychological flexibility might also be correlated.

To date, no study has yet looked at the relationship between psychological flexibility and the experience of race-based trauma. However, a recent investigation 30 explored whether psychological flexibility mediated the outcomes of psychedelics on depression and anxiety symptoms among a large primarily White sample of 985 online survey respondents who used psychedelics. Results indicated that the intensity of acute drug effects (ie, mystical-type and insightful effects) was significantly associated with decreases in depression/anxiety following the psychedelic experience, and a path analysis showed that increases in psychological flexibility fully mediated the effect of mystical-type and insightful experiences on decreases in depression and anxiety. Furthermore, a recent prospective study 55 found that psychological flexibility (measured with the AAQ-II47,48) improved from pre- to postpsychedelic experience and that these changes were correlated with decreases in depressive symptoms. Results also showed that the acute psychedelic effects (mystical experience and emotional breakthrough) were associated with greater improvements in psychological flexibility. 55 Another report 56 showed that psychological insight (measured with the PIQ 30 ) was significantly correlated with retrospectively reported increases in psychological flexibility that occurred from pre- to postpsychedelic experience. Although emerging evidence suggests that acute insight experiences may be highly correlated with therapeutic outcomes,23,30 it is important to consider that these effects usually occur in the context of a mystical-type experience and prior studies that have modeled this relationship have controlled for the moderate to large correlation between these variables. 30

Taken together, these findings suggest that psychological flexibility may be an important mediator of the acute effects of psychedelic drugs on therapeutic outcomes. Therefore, this study sought to examine psychological flexibility as a mediator of the relationship between acute psychedelic effects and changes in racial trauma symptoms among POC. Because prior research showed that acute psychedelic effects (mystical type, insight, and challenging) are associated with reductions in trauma symptoms in this population, 21 that psychedelic effects are associated with changes in psychological flexibility, 30 and that increases in psychological flexibility are associated with positive mental health outcomes.30,57 Firstly, we hypothesize (Hypothesis 1 [H1]) that a multiple linear regression model will show that acute psychedelic effects (mystical-type, challenging, and insight effects) will be associated with changes in racial trauma symptoms following a psychedelic experience. Secondly, we hypothesize that a path analysis model will show that acute psychedelic effects will be directly related to changes in psychological flexibility (H2), that changes in psychological flexibility will be directly related to changes in racial trauma symptoms (H3), and that psychological flexibility will mediate the relationships between acute psychedelic effects and changes in racial trauma symptoms (H4).

Methods

Procedure

The present study includes data from a larger cross-sectional, observational study among POC. 21 Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old, able to read and understand English, having used a psychedelic that produced psychoactive effects, experienced relief from racial discrimination after taking the psychedelic, and currently reside in Canada or the United States. During September of 2019, potential participants clicked an electronic advertisement sent directly from Qualtrics. Potential participants were recruited by the Qualtrics team as they were all members of their research panels. 21 They were then presented with the informed consent document and led to a secure online survey to complete their questionnaire. Eligible participants were asked to report their past racial trauma experiences, experience of psychedelic use and its acute and enduring effects, and mental health symptoms. After data cleaning (ie, “poor responder” detection, “bot” detection, and duplicate responses), we have included 313 participants as the final sample. There was no missing data because participants were required to respond to every item in order to continue in the survey. Qualtrics provided an incentive to their research participant panels for their time completing the survey. See the published primary outcomes paper for more details. 21

Measures

Demographics

Items queried participants to report their age, gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, income, level of education, and marital status.

General Ethnic Discrimination Scale

Seventeen multipart questions from the General Ethnic Discrimination Scale 58 examined the frequency and severity of discrimination that participants experienced in education, employment, legal, health care, or community settings due to one's race/ethnicity. Frequency of discrimination experiences were rated on a 6-point scale (from 1 = “Never” to 6 = “Almost all the time”). Instructions were modified to orient participants to report the frequency of racial discrimination before the psychedelic experience. Internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach's alpha = 0.95).

Psychedelic Experience Questionnaire

This 8-item questionnaire assessed the type of psychedelic used, the age of having the psychedelic experience, memory of the experiences, and self-reported dose and length of the psychedelic experience.

Psychological Insight Questionnaire

The 23-item PIQ30,56 was included and participants were oriented to think back on their psychedelic experience and then to rate their insights on a 6-point scale (from 0 = “No; not at all” to 5 = “Extremely/More than ever before in my life”). For this study, we used a total scale mean score and internal consistency reliability was excellent (Cronbach's alpha = 0.95).

Mystical Experience Questionnaire

The 30-item MEQ28,29 was included, and participants were oriented to think back their psychedelic experience and then to rate their mystical-type experience on a 6-point scale (from 0 = “None; not at all” to 5 = “Extremely/More than ever before in my life”). For this study, we used a total scale mean score, and internal consistency reliability was excellent (Cronbach's alpha = 0.96).

Challenging Experience Questionnaire

The 26-item CEQ 38 was included, and participants were oriented to think back to their psychedelic experience and then to rate their feelings of grief, fear, insanity, death, isolation, physical distress, or paranoia on a 6-point scale (from 0 = “No; not at all” to 5 = “Extremely/More than ever before in my life”). For this study, we used a total scale mean score and internal consistency reliability was excellent (Cronbach's alpha = 0.97).

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II

The 7-item AAQ-II47,48 was included as a measure of psychological flexibility to evaluate avoidance, emotional states, and perceptions of oneself on a 7-point scale (from 1 = “Never true” to 7 = “Always true”). For this study, we calculated the mean psychological flexibility change score from “before the psychedelic experience” to “after the psychedelic experience.” The sign of these scores was then reversed to aid in the interpretability of the findings (eg, + was changed to − such that a decrease in score would be interpreted as an increase in psychological flexibility). Internal consistency reliability was good (“before” measure: Cronbach's alpha = 0.89; “after” measure: Cronbach's alpha = 0.89).

Trauma Symptoms of Discrimination Scale

The 21-item Trauma Symptoms of Discrimination Scale 5 was included in this study to examine participants’ discriminatory distress about symptoms of trauma (ie, uncontrollable arousal, feelings of alienation, worries about future negative events, and perceiving others as dangerous) in the 30 days before and 30 days after the psychedelic experience. The participants were oriented to think back to their psychedelic experience and to rate the frequency of their experience of discriminatory distress regarding trauma on a 4-point scale (from 0 = “Never” to 3 = “Often”). For this study, we used a total scale score and calculated the average change in trauma symptoms from “30 days before the psychedelic experience” to “30 days after the psychedelic experience.” Internal consistency reliability for the total scale score was excellent (“before” measure: Cronbach's alpha = 0.96; “after” measure, Cronbach's alpha = 0.95).

Analytic Plan

Firstly, descriptive statistics for demographic and background characteristics for all study variables were calculated. Normality for all primary study variables was checked and no values for skewness or kurtosis fell outside an acceptable range. Pearson and point biserial correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships among all primary study variables (age, sex, acute insight, mystical-type, and challenging effects, trauma symptom change score, and psychological flexibility change score; race groups). Next, a regression analysis was used to test (H1): acute mystical-type, challenging, and insight experiences will be associated with trauma symptom change scores. A path analysis was then used to test hypothesized direct effects (H2-H3: Intensity of psychological insight, challenging, and mystical-type effects have a direct effect on changes in psychological flexibility, and changes in psychological flexibility have a direct effect on changes in trauma symptoms) and mediation effects (H4): Intensity of psychological insight, challenging, and mystical-type effects are indirectly related to changes in trauma symptoms via changes in psychological flexibility. The sum of ethnic discrimination events was included as a control variable in the regression and path analyses. Although race was considered as a control variable, it was uncorrelated with all other variables and thus was excluded from analyses. Analyses were conducted in SPSS v 27 59 and MPlus version 8.0 using maximum likelihood estimators. 60

Results

Respondent Characteristics

The sample for this study was recruited intentionally for diversity, with about one-half of the participants currently living in Canada, and the other half in the United States. Most participants reported their race as black or African heritage (32%), East Asian, South Asian, Asian American/Canadian (29%), with smaller proportions reporting their race was Native American or Indigenous Canadian (18%), or Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, other (21%). Most other demographic characteristics have been reported in the primary manuscript from this study. 21 Briefly, the average age in the sample was 33.1 (SD = 11.2), approximately one-half were female (57%), living with a partner or married (51%), and three-quarters reported annual household income equal to or greater than $35 000 (73%). Approximately equal proportions of participants reported they consumed LSD (36%), psilocybin/mushrooms (37%), or 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; 27%) during their psychedelic experience, and about one-half (∼56%) reported that they consumed a moderately high or high dose (see the published manuscript 21 for further demographic data).

Associations Between Acute Psychedelic Effects and Changes in Psychological Flexibility and Changes in Trauma Symptoms

A series of point-biserial correlations (Table 1) revealed that race subgroup was weakly related (range: −0.17 to 0.13) to the intensity of acute psychedelic effects (acute challenging, insight, and mystical-type effects), trauma symptom change scores, and psychological flexibility change scores. As Table 1 also shows, Pearson correlations revealed that the intensity of mystical-type and insight effects was strongly positively correlated with each other, and insight was weakly positively correlated with the intensity of challenging effects. Greater intensity of acute insight and mystical-type experiences was moderately positively correlated with changes in psychological flexibility and negatively correlated with decreases in trauma symptoms. Additionally, greater changes in psychological flexibility were associated with greater changes in trauma symptoms. A series of Pearson correlations also revealed that psychological flexibility was negatively correlated with number of trauma symptoms prior to the psychedelic experience (R = −0.66, p < .001), and after the psychedelic experience (R = −0.61, p < .001).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Variables (ie, Mystical-Type Experiences Score, Challenging Experiences Score, Psychological Insight Score, Trauma Symptom Change Score, Psychological Flexibility Change Score; Sum of Ethnic Discrimination Events, Race Groups; N = 313).

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological insight | 2.78 (1.01) | . | 0.72 | 0.21 | 0.36 | −0.36 | 0.47 | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.10 | −0.01 |

| 2. Mystical-type experiences | 3.03 (1.03) | 0.05 | 0.35 | −0.34 | 0.40 | 0.00 | −0.13 | 0.08 | 0.07 | ||

| 3. Challenging effects | 1.52 (1.17) | −0.24 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.10 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.01 | |||

| 4. Changes in psychological flexibility a | 0.93 (1.55) | −0.68 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | ||||

| 5. Changes in trauma symptoms | −8.64 (16.19) | −0.18 | 0.13 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.12 | |||||

| 6. Sum of lifetime discrimination | 31.95 (17.23) | 0.12 | −0.21 | 0.10 | 0.01 | ||||||

| 7. Race: black or African heritage | 0.32 (0.47) | −0.44 | −0.31 | −0.36 | |||||||

| 8. Race: Asian b | 0.29 (0.46) | −0.30 | −0.34 | ||||||||

| 9. Race: native/Indigenous c | 0.18 (0.38) | −0.24 | |||||||||

| 10. Race: native Hawaiian/PI d | 0.21 (0.41) | . |

Note. Bolded items were considered statistically significant (p < .001) and meaningful (r > 0.20).

The AAQ-II was originally developed as a measure of psychological inflexibility. Reduction in AAQ scores indicates an increase in psychological flexibility. However, to ease interpretation, we have calculated a positive change score to denote increases in psychological flexibility.

East Asian, South Asian, Asian American/Canadian.

Native American or Indigenous Canadian.

Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, other.

Abbreviation: AAQ-II, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II.

Regression Analysis

Table 2 shows data from the multiple linear regression controlling for the sum of ethnic discrimination events (M = 31.95; SD = 17.23; range: 0-85) and including acute mystical-type (M = 3.03; SD = 1.03; range: 0.37-5), challenging (M = 1.52; SD = 1.17; range: 0-5), and insight effects (M = 2.78; SD = 1.01; range: 0.17-5.0) as correlates of decreases in trauma symptoms from before to after the psychedelic experience (M = −8.64; SD = 16.19; range: −62 to 63). After controlling for the sum of ethnic discrimination events, the overall model was significant (p < .001), accounting for 23% of the variance in trauma symptom change scores (H1). Although accounting for a small amount of variance in this model, greater intensity of insight effects and less intensity of challenging effects were significantly associated with decreases in trauma symptoms (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Multiple Linear Regression Showing Significant Predictors of Changes in Trauma Symptoms From Before to After a Psychedelic Experience (N = 313).

| Variables | B | SE B | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 5.66 | 2.74 | |||

| Sum of lifetime discrimination | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.05 | −0.870 | .385 |

| Mystical-type effects | −1.72 | 1.15 | −0.11 | −1.50 | .135 |

| Psychological insight effects | –5.16 | 1.23 | −0.32 | −4.20 | p < .001 |

| Challenging experiences | 4.47 | 0.72 | 0.32 | 6.20 | p < .001 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.23 |

Note. The overall model was significant, F(4, 312) = 23.93, p < .001.

Path Analysis

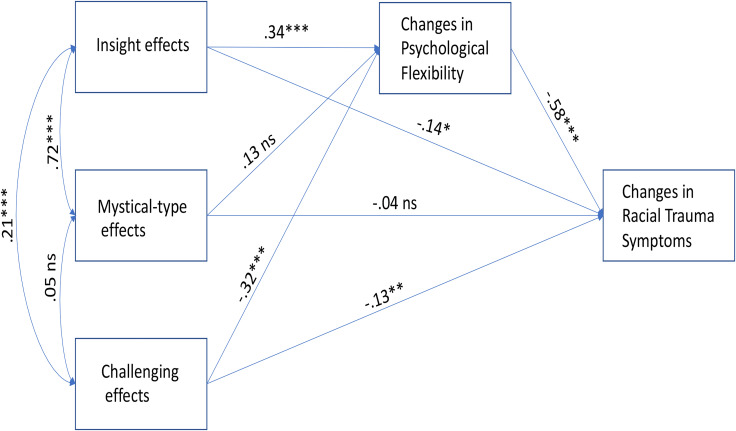

As shown in Figure 1, the path analysis controlling for the sum of ethnic discrimination events prior to the psychedelic experience revealed that greater mean intensity of acute insight effects and less intensity of challenging effects were directly related (insight: β = 0.34, p < .001; challenging: β = −0.32, p < .001) to mean increases in psychological flexibility (Mincrease = 0.93; SD = 1.55; range: −5.14 to 6; supporting H2), and mean changes in psychological flexibility were directly related (β = −0.58, p < .001) to mean changes in racial trauma symptoms (supporting H3). Findings also revealed indirect effects wherein changes in psychological flexibility mediated the relationships between the intensity of acute insight (β = 0.20, SE = 0.04, p < .001), and challenging (β = −0.18, SE = 0.03, p < .001) effects and mean changes in racial trauma symptoms (supporting H4). Model fit was excellent: χ2 = 1.865 (p = .394); root mean square error of approximation = 0.000 (90% CI: .00, .11); comparative fit index = 1.00; standardized root-mean-square residual = 0.008.

Figure 1.

Path analysis showing that changes in psychological flexibility mediate the relationship between acute psychedelic effects and changes in trauma symptoms among individual exposed to racial trauma (N = 313). ns = not significant, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Discussion

Several hypotheses were tested to examine the relationship between psychological flexibility and racial trauma symptoms in this sample of POC. Firstly, a multiple linear regression model found that acute psychedelic effects, specifically greater intensity of acute insight and lower intensity of challenging experience, were significant correlates of change in racial trauma symptoms (H1). Interestingly, mystical-type effects were not significantly related to the change in racial trauma symptoms, suggesting these may be less important for therapeutic benefits in POC or possibly less relevant specifically to racial trauma symptoms. It could also be related to the fact that approximately one-quarter of the sample reported using MDMA which is known to produce less intense mystical-type effects, 61 thus possibly attenuating this relationship in the sample.

Secondly, greater intensity of acute insight effects and lower intensity of challenging effects were directly related to changes in psychological flexibility, supporting the hypothesis that acute psychedelic effects directly impact changes in psychological flexibility (H2). These findings add to a growing literature indicating a central role for acute subjective effects of psychedelics in influencing subsequent mental health outcomes,24,25,33,62,63 and suggest that psychological flexibility may be an important factor related to those outcomes.30,45 Interestingly, there is also a small, but statistically significant, correlation between the intensity of challenging and insight effects in this sample. This relationship could be due to increases in negative emotional and physiological arousal that may accompany novel insights into one's past traumatic experiences. However, data from this study does not allow for causal inferences, and therefore, this hypothesis awaits further testing in clinical trials.

Thirdly, there was a direct relationship between psychological flexibility and changes in racial trauma symptoms, such that changes in psychological flexibility were related to changes in racial trauma symptoms (H3). These results suggest that consistent with other research,64,65 psychological flexibility may be a substantial factor contributing to mental health per se, apart from psychedelic use, and comprises an area for further study in its own right.

Fourthly, psychological flexibility mediated the relationships between acute psychedelic effects (ie, insight and challenging effects) and changes in racial trauma symptoms (H4). This finding supports models of psychedelics’ therapeutic efficacy being linked to increases in psychological flexibility and presents intriguing opportunities for incorporating psychological flexibility as a therapeutic target in psychedelic-assisted therapies.30,42,43 Although a number of neurobiological and psychological mechanisms of psychedelics’ therapeutic efficacy have been posited in the literature, there is as yet no consensus on how observed benefits of psychedelics can persist for months or years after the acute effects have subsided. The present results add to the emerging literature suggesting psychological flexibility could be an important mediator of psychedelics’ benefits that necessitates additional focused research. Furthermore, it adds to our understanding specifically of how psychological flexibility may be beneficial to POC in overcoming racial trauma.

Notable study limitations include potential recall bias in participants’ ability to accurately remember symptoms and psychedelic experiences that occurred months or sometimes years in the past. As the study was conducted using a cross-sectional online survey design, participant responses cannot be conclusively verified. Similarly, participant self-selection and computer literacy and availability may have impacted the accessibility of this research study. Additionally, because participants were purposively sampled to collect data from individuals reporting benefits in racial trauma symptoms after psychedelic use, we cannot determine the relative prevalence of such positive outcomes or characterize cases in which POC who used psychedelics may have experienced negative mental health outcomes. Furthermore, this study lacks multiple prospective assessments to measure changes in psychological flexibility or mental health symptoms over time, which is needed to make strong interpretations of mediational analyses. However, to partially overcome this limitation, we employed a quasiexperimental 1-group pretest/posttest design using “then-test” items to assess symptoms 1 month prior to and 1 month after the psychedelic experience. This type of design allows for cautious interpretation of temporality, although these data should be replicated in a prospective study. It is also possible that other confounding factors, such as halo effects and expectancies were related to outcomes reported in this study.

In addition to the limitations above, several concerns have been raised about the AAQ-II as a measure of psychological flexibility. Recent studies have explored the convergent and discriminant validity of the AAQ-II compared to other measures of psychological flexibility and experiential avoidance,66–68 suggesting the AAQ-II may be more strongly related to negative affect and personality constructs, than to features theorized as the core aspects of psychological flexibility. Secondly, there may be questionable face validity of the items included on the AAQ-II, such that they may be more related to psychopathology rather than psychological flexibility. Nevertheless, the AAQ-II remains a predominant measure of psychological flexibility, but further investigation of the validity of this assessment tool is warranted. Lastly, it is possible that the subjective indicators of the acute psychedelic state as measured by the MEQ, PIQ, and CEQ, are correlated with objective neurobiological changes that underlie shifts in psychological flexibility. These relationships should be explored in laboratory-based studies.

Conclusion and Implications

POC face substantial health disparities, including unique and often undertreated mental health challenges.69,70 Among these, trauma and racial trauma are particularly debilitating and difficult to treat.71–73 Psychedelic studies have also lacked inclusion of POC and little is known about the unique ways in which psychological processes may underlie the potential therapeutic effects of psychedelics in this population. Thus, despite the limitations noted above, the present study and related research on psychedelic benefits in POC 21 represent a promising path ahead for developing novel, tailored interventions for POC that incorporate the current wave of research and clinical interest in psychedelic-assisted therapies. Although psychedelic-assisted interventions may not directly impact systemic factors such as poverty, unemployment, and criminal justice inequity that greatly contribute to current mental health disparities,74,75 they do comprise a critical potential avenue for improving mental health outcomes in POC, which is urgently needed. This work also highlights a much-needed expansion of research efforts to include racial/ethnic and other minoritized populations in assessing psychedelics’ therapeutic potentials for underserved communities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: Drs Williams and Davis are board members of Source Research Foundation. This organization was not involved in the design/execution of this study or the interpretation or communication of findings.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for the study was provided by the University of Ottawa and the Canada Research Chairs Program (MTW). by the Effort for AKD, AGR, and NDS was provided from support from Tim Ferriss, Matt Mullenweg, Craig Nerenberg, Blake Mycoskie, and the Stevenand Alexandra Cohen Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval: This study (2019E0717) was deemed exempt from review by the Ohio State University human research protection program.

ORCID iDs: Alan K. Davis https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4770-8893

Yitong Xin https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5871-1137

References

- 1.APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter RT. Racism and psychological and emotional injury: recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. Couns Psychol 2007;35(1):13–105. doi: 10.1177/0011000006292033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams MT, Metzger I, Leins C, et al. Assessing racial trauma within a DSM-5 framework: the UConn racial/ethnic stress & trauma survey. Pract Innov 2018;3(4):242–260. doi: 10.1037/pri0000076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Justice. Hate crime statistics. Hate Crime Stat 2014. Available from: https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams MT, Printz DMB, DeLapp RCT. Assessing racial trauma with the trauma symptoms of discrimination scale. Psychol Violence 2018;8(6):735–747. doi: 10.1037/vio0000212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant-Davis T, Ocampo C. A therapeutic approach to the treatment of racist-incident-based trauma. J Emot Abuse 2006;6(4):1–22. doi: 10.1300/J135v06n04_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butts HF. The black mask of humanity: racial/ethnic discrimination and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2002;30(3):336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams MT, Malcoun E, Sawyer BA, et al. Cultural adaptations of prolonged exposure therapy for treatment and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans. Behav Sci Basel Switz 2014;4(2):102–124. doi: 10.3390/bs4020102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs DS, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59(5):715–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asmundson GJG, Thorisdottir AS, Roden-Foreman JW, et al. A meta-analytic review of cognitive processing therapy for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder. Cogn Behav Ther 2019;48(1):1–14. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2018.1522371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benuto LT, Bennett NM, Casas JB. Minority participation in randomized controlled trials for prolonged exposure therapy: a systematic review of the literature. J Trauma Stress 2020;33(4). doi: 10.1002/jts.22539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloitre M. Effective psychotherapies for posttraumatic stress disorder: a review and critique. CNS Spectr 2009;14(1 Suppl 1):32–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, et al. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry 2008;71(2):134–168. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.2.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Rucker J, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3(7):619–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Potential therapeutic effects of psilocybin. Neurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother 2017;14(3):734–740. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0542-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palhano-Fontes F, Barreto D, Onias H, et al. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychol Med 2019;49(4):655–663. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dos Santos RG, Osório FL, Crippa JAS, et al. Antidepressive, anxiolytic, and antiaddictive effects of ayahuasca, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): a systematic review of clinical trials published in the last 25 years. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2016;6(3):193–213. doi: 10.1177/2045125316638008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Johnson PS, et al. An online survey of tobacco smoking cessation associated with naturalistic psychedelic use. J Psychopharmacol Oxf Engl 2017;31(7):841–850. doi: 10.1177/0269881116684335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis AK, Barsuglia JP, Lancelotta R, et al. The epidemiology of 5-methoxy- N, N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) use: benefits, consequences, patterns of use, subjective effects, and reasons for consumption. J Psychopharmacol Oxf Engl 2018;32(7):779–792. doi: 10.1177/0269881118769063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis AK, So S, Lancelotta R, et al. 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) used in a naturalistic group setting is associated with unintended improvements in depression and anxiety. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2019;45(2):161–169. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2018.1545024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams M, Davis AK, Xin Y, et al. People of color in North America report improvements in racial trauma and mental health symptoms following psychedelic experiences. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 2020;28(3):215–226. 10.1080/09687637.2020.1854688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carhart-Harris RL, Roseman L, Bolstridge M, et al. Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms. Sci Rep 2017;7(1)13187. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13282-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, et al. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on Major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78(5):481–489. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2016;30(12):1165–1180. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2016;30(12):1181–1197. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos RG, Landeira-Fernandez J, Strassman RJ, et al. Effects of ayahuasca on psychometric measures of anxiety, panic-like and hopelessness in santo daime members. J Ethnopharmacol 2007;112(3):507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uthaug MV, van Oorsouw K, Kuypers KPC, et al. Sub-acute and long-term effects of ayahuasca on affect and cognitive thinking style and their association with ego dissolution. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2018;235(10):2979–2989. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4988-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrett FS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Validation of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2015;29(11):1182–1190. doi: 10.1177/0269881115609019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacLean KA, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2011;25(11):1453–1461. doi: 10.1177/0269881111420188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Context Behav Sci 2020;15:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffiths R, Richards W, Johnson M, et al. Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2008;22(6):621–632. doi: 10.1177/0269881108094300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Richards WA, et al. Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: immediate and persisting dose-related effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218(4):649–665. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2358-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roseman L, Nutt DJ, Carhart-Harris RL. Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Front Pharmacol 2018;8:974. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Romeu A, Davis AK, Erowid F, et al. Cessation and reduction in alcohol consumption and misuse after psychedelic use. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2019;33(9):1088–1101. doi: 10.1177/0269881119845793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michaels TI, Purdon J, Collins A, et al. Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: a review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:(245):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1824-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerrard M, Stock ML, Roberts ME, et al. Coping with racial discrimination: the role of substance use. Psychol Addict Behav 2012;26(3):550–560. doi: 10.1037/a0027711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurd NM, Varner FA, Caldwell CH, et al. Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Dev Psychol 2014;50(7):1910–1918. doi: 10.1037/a0036438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrett FS, Bradstreet MP, Leoutsakos J-MS, et al. The challenging experience questionnaire: characterization of challenging experiences with psilocybin mushrooms. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2016;30(12):1279–1295. doi: 10.1177/0269881116678781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carhart-Harris RL, Leech R, Hellyer PJ, et al. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Front Hum Neurosci 2014;8:20. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendricks PS. Awe: a putative mechanism underlying the effects of classic psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Int Rev Psychiatry Abingdon Engl 2018;30(4):331–342. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1474185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preller KH, Vollenweider FX. Phenomenology, structure, and dynamic of psychedelic states. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2018;36:221–256. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sloshower J, Guss J, Krause R, et al. Psilocybin-assisted therapy of major depressive disorder using acceptance and commitment therapy as a therapeutic frame. J Context Behav Sci 2020;15:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watts R, Luoma JB. The use of the psychological flexibility model to support psychedelic assisted therapy. J Context Behav Sci 2020;15:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabucedo P. The psychological flexibility model from a cultural perspective: an interpretative analysis of two Native American healing rituals. Int J Cult Ment Health 2017;10(4):367–375. doi: 10.1080/17542863.2017.1323935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuypers KPC, Riba J, de la Fuente Revenga M, et al. Ayahuasca enhances creative divergent thinking while decreasing conventional convergent thinking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016;233(18):3395–3403. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4377-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh Z, Thiessen MS. Psychedelics and the new behaviourism: considering the integration of third-wave behaviour therapies with psychedelic-assisted therapy. Int Rev Psychiatry Abingdon Engl 2018;30(4):343–349. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1474088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther 2011;42(4):676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KGet al. Measuring experiential avoidance: a preliminary test of a working model. Psychol Rec 2004;54(4):553–578. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gloster AT, Meyer AH, Lieb R. Psychological flexibility as a malleable public health target: evidence from a representative sample. J Context Behav Sci 2017;6(2):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.02.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30(7):865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hosseini Ramaghani NA, Rezaei F, Sepahvandi MA, Gholamrezaei S, Mirderikvand F. The mediating role of the metacognition, time perspectives and experiential avoidance on the relationship between childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2019;10(1):1648173. Published 2019 August 16. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1648173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyer EC, Morissette SB, Kimbrel NA, Kruse MI, Bird Gulliver S. Acceptance and action questionnaire –II scores as a predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among war veterans. Psychol Trauma: Theory, Res Pract Policy 2013;5(6):521–528. doi: 10.1037/a0030178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tull MT, Roemer L. Alternative explanations of emotional numbing of posttraumatic stress disorder: an examination of hyperarousal and experiential avoidance. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2003;25(3):147–154. 10.1023/A:1023568822462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Close JB, Hajien EC, Watts R, Roseman L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics and psychological flexibility—results of a prospective web-survey using the acceptance and Action Questionnaire II. J Contextual Behav Sci 2020;16(3):37–44. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.01.005 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis AK, Barrett FS, So S, et al. Development of the psychological insight questionnaire among a sample of people who have consumed psilocybin or LSD. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf, Engl) 2021;35(4):437–446. 10.1177/0269881120967878. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Twohig MP, Levin ME. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for anxiety and depression: a review. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017;40(4):751–770. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Corral I, et al. Conceptualizing and measuring ethnic discrimination in health research. J Behav Med 2006;29(1):79–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9029-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows IBM Corp; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide 8th ed. Muthén and Muthén; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmid Y, Gasser P, Oehen P, et al. Acute subjective effects in LSD- and MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2020;35(4):362–374. doi: 10.1177/0269881120959604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, et al. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2015;29(3):289–299. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths R, Johnson M. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157–164. doi: 10.2174/1874473708666150107121331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeBeer BB, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, et al. Psychological inflexibility predicts of suicidal ideation over time in veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2018;48(6):627–641. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meyer EC, La Bash H, DeBeer BB, et al. Psychological inflexibility predicts PTSD symptom severity in war veterans after accounting for established PTSD risk factors and personality. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 2019;11(4):383–390. doi: 10.1037/tra0000358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tyndall I, Waldeck D, Pancani L, Whelan R, Roche B, Dawson DL. The acceptance and action questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) as a measure of experiential avoidance: concerns over discriminant validity. J Contextual Behav Sci 2019;12:278–284. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rochefort C, Baldwin AS, Chmielewski M. Experiential avoidance: an examination of the construct validity of the AAQ-II and MEAQ. Behav Ther 2018;49(3):435–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ong CW, Pierce BG, Petersen JMet al. et al. A psychometric comparison of psychological inflexibility measures: discriminant validity and item performance. J Contextual Behav Sci 2020;18:34–47. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health 2010;100(5):933–939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lipson SK, Kern A, Eisenberg D, et al. Mental health disparities Among college students of color. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2018;63(3):348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Himle JA, Baser RE, Taylor RJ, et al. Anxiety disorders among African Americans, blacks of Caribbean descent, and non-hispanic whites in the United States. J Anxiety Disord 2009;23(5):578–590. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koo KH, Hebenstreit CL, Madden E, et al. PTSD Detection and symptom presentation: racial/ethnic differences by gender among veterans with PTSD returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. J Affect Disord 2016;189:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Santos MR, Russo J, Aisenberg G, et al. Ethnic/racial diversity and posttraumatic distress in the acute care medical setting. Psychiatry Interpers Biol Process 2008;71(3):234–245. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.3.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chow JC-C, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. Am J Public Health 2003;93(5):792–797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dumont DM, Allen SA, Brockmann BW, et al. Incarceration, community health, and racial disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2013;24(1):78–88. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]