Abstract

Debate and scientific inquiries regarding airborne transmission of respiratory infections such as COVID-19 and influenza continue. Health authorities including the WHO and the US CDC have recognized the airborne transmission of COVID-19 in specific settings, although the ventilation requirements remain to be determined. In this work we consider the long-range airborne transmission as an extended short-range airborne route, which reconciles the link between short- and long-range airborne routes. The effective short-range distance is defined as the distance in short range at which long-range route has the same volumetric exposure value as that due to short-range route. Our data show that a decrease in ventilation rate or room volume per person, or an increase in the ratio of the number of infected to susceptible people reduces the effective short-range distance. In a normal breathing scenario with one out of five people infected and a room volume of 12 m3 per person to ensure an effective short-range distance of 1.5 m, a ventilation rate of 10 L/s per person is needed for a duration of 2 h. Our results suggest that effective environmental prevention strategies for respiratory infections require appropriate increases in the ventilation rate while maintaining a sufficiently low occupancy.

Practical implications

Demonstration of the long-range airborne route as an extended short-range airborne route suggests the significant role played by building ventilation in respiratory infection exposure. The reconciliation of short- and long-range airborne transmission suggests that the commonly observed dominance of close-contact transmission is a probable evidence of short-range airborne transmission, following a separate earlier study that revealed the relative insignificance of large droplet transmission in comparison with the short-range airborne-route. Existing ventilation standards do not account for respiratory infection control, and this study presents a possible approach to account for infection under new ventilation standards.

Keywords: Airborne transmission, Ventilation rate, Crowding, Indoor environment, COVID-19

Graphical Abstract

Nomenclature

Room area per person [m2]

Indoor droplet nuclei concentration [ppm]

Corrected indoor droplet nuclei concentration at mouth [ppm]

Initial droplet nuclei concentration [ppm]

Droplet nuclei diameter after evaporation [m]

Volumetric exposure at long range corrected at mouth [μL]

Volumetric exposure at short range considering evaporation [μL]

Volumetric exposure at short range corrected at mouth [μL]

- H

Room height [m]

- I

Number of infected people [-]

Droplet deposition rate [s−1]

Exhaled droplet number [-]

Air exchange rate per second [s−1]

- N

Total number of occupants [-]

Inhalation flow rate [m3·s−1]

Ventilation rate per person [m3·s−1]

Time [s]

- Ttalk

Time required for counting from “1” to “100” [s]

- Tcough

Time between two coughs for asthma patients [s]

Total volume of the room [m3]

Room volume per person [m3]

Total volumetric generation rate [m3·s−1]

Volumetric generation rate by a single source patient [m3·s−1]

Droplet volume at a distance of 0 [m3]

Droplet volume at a distance of x [m3]

Short-range distance [m]

Effective short-range distance at time t [m]

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread globally. The possible long-range airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in specific settings has been recognized by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization (WHO) since July 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020a), which has significant implications regarding interventions. For this reason, enhancing building ventilation has been widely recommended by most health authorities and professional engineering societies (e.g., ASHRAE, 2020; REHVA, 2020). However, ambiguity or inconsistency existed in the health authorities’ recommendations regarding the potential for airborne transmission, as the possible dominant role of the short-range airborne route (Li, 2021) has only been recognized for COVID-19 since April/May 2021 (World Health Organization, 2021, US CDC, 2021). It is widely accepted that SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted via close contact (Zhang et al., 2020). Epidemiological studies of outbreaks do not distinguish between large droplets and short-range airborne transmission. To our best knowledge, no direct evidence of short-range airborne transmission exists so far. The question that arises is how to reconcile the co-existence of the long-range airborne route and close contact route.

However, the SARS-CoV-2 virus is not the only case. Significant confusion and debate remain over the role of long-range airborne transmission in other respiratory infections. The most characteristic example is probably the Alaska plane influenza outbreak (Moser et al., 1979). The outbreak involved a plane with a 56-seat passenger compartment, delayed for 4.5 h due to engine failure. Intake of outdoor air was only made possible through intermittent opening of the doors and through the movement of the passengers in and out of the plane, as the outdoor temperature was low (1.7 °C). Rudnick and Milton (2003) estimated that the ventilation rate was only 0.08 L/s to 0.4 L/s per passenger using hypothetical outdoor air exchange rates. Eventually, 72% of the 54 passengers on board were infected. Systematic reviews such as Li et al. (2007) considered that the outbreak showed sufficient evidence for the airborne transmission of influenza, whereas others such as Brankston et al. (2007) did not. The latter author did, however, suggest that influenza “may be transmitted by the airborne route under certain experimental conditions.” He noted that “this leaves open the possibility that influenza could be an opportunistic airborne pathogen, although this is not proven by the current literature.”

Studies conducted in a jail by Hoge et al. (1994), in hospitals by Menzies et al. (2000), in a restaurant by Li et al. (2021) and using mice by Schulman and Kilbourne (1962) all demonstrated a correlation between the ventilation rate and the infection rate for respiratory infections. Using mathematical modeling of multi-route infection, Gao et al. (2016) showed that the relative contribution of the long-range airborne route is a function of the ventilation flow rate. A sufficiently large ventilation flow rate significantly reduces the contribution of the long-range airborne route, making it very small, whereas a small ventilation flow rate leads to a relatively high contribution of the long-range airborne route. These early studies clearly implied that for some respiratory infections, it is possible that long-range airborne transmission can become absent or non-observable when the ventilation rate is sufficiently high. Consequently, it has to be recognized that long-range airborne transmission is likely to occur when the ventilation rate is below a certain unknown threshold.

Infectious aerosols are mostly respiratory in origin, i.e., their droplets are expired during the respiratory activities of the infected. The infection risk will obviously be the greatest when the infected person and the susceptible person are in close contact. Liu et al. (2017) proposed that in addition to the traditional large droplet route, a short-range airborne route could play an important role. Chen et al. (2020) further showed that the short-range airborne route mechanistically dominated the exposure to respiratory infection during close contact.

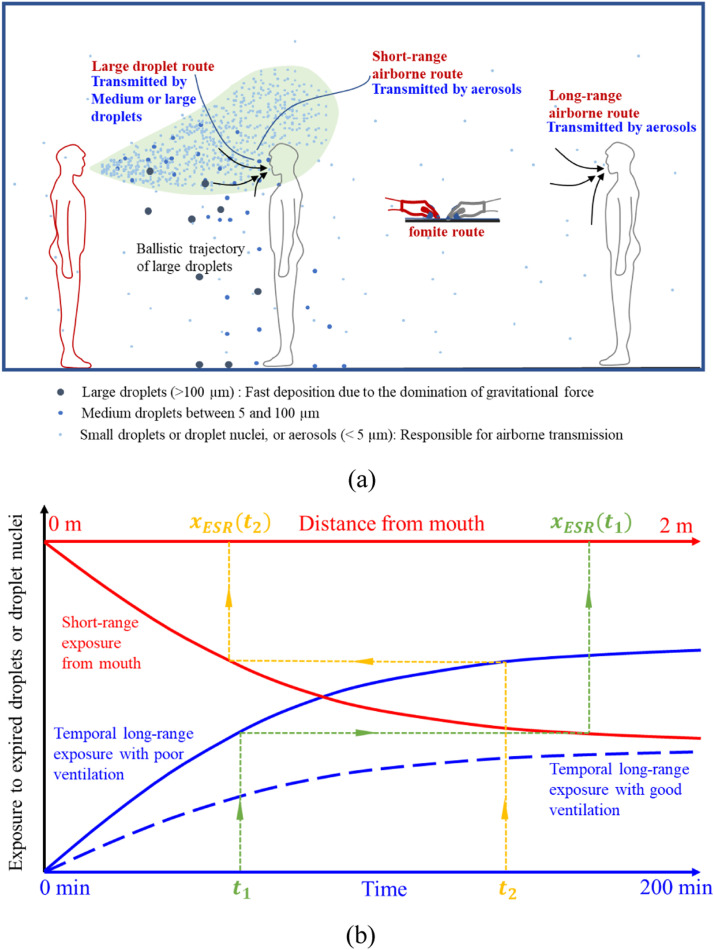

The long- and short-range airborne routes need to be considered together to investigate the possibility of long-range airborne transmission under certain circumstances. This strategy will in turn lead to a new method for exploring short-range airborne transmission. Consider the spatial concentration profile from the mouth of the infected. As can be seen in Fig. 1(a), there is a continuous reduction in the concentration of the expired jet, and at some distance, the expired jet becomes so indistinguishable that the expired flow merges into the background room flow. Because the room average concentration is a function of the source strength and of the ventilation rate, one can assume that when the ventilation rate is sufficiently low, the room average concentration can become as high as when there is direct exposure to the expired air in close contact. Fig. 1(b) shows two scenarios of increase in the room average concentration of the expired droplet nuclei in the case of good and poor ventilation, respectively. Additionally, it shows the average exposure to expired droplets due to their inhalation at close distance. When the ventilation rate is low, the long-range exposure can be identical to that at close distance. This distance is referred to as the effective short-range distance of the long-range exposure, or in short effective distance, which connects the time needed for the long-range exposure with the distance during the short-range exposure. Using the concept of effective distance, it is also possible to measure the effectiveness of ventilation.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of (a) the close contact transmission and long-range airborne route in a room (modified from Wei and Li, 2016), and (b) the proposed bridging approach for the long- and short-range airborne exposure of expired droplets from the infected. The effective short-range distance of the long-range exposure for an exposure duration is shown for two exposure cases.

In this paper, we use a simple macroscopic mass balance model for the droplet nuclei in a room, and a simple exposure model for the short-range airborne route. The goal is to demonstrate when and how the extended short-range airborne transmission, i.e., long-range airborne transmission, occurs under poor ventilation for an airborne infection that is normally transmitted by non-long-range routes under good ventilation.

2. Methods

2.1. Long-range airborne exposure

A simple exposure model was used for estimating the long-range airborne route, as shown in Fig. 2. We consider N persons gathered in a room (height H = 3 m), with the average room volume per person being , among whom I ( ) are infected. The room is ventilated at a rate of per person. Assume that one infected person appears in the room at time zero (t = 0) and is in close contact with one susceptible person, while the remaining susceptible people experience long-range airborne exposure. Following the method described in Li and Chen (2003), the temporal room droplet nuclei concentration is governed by the following macroscopic mass balance equation. In this equation, we ignore resuspension and other sinks and assume the outdoor droplet nuclei concentration is zero. The droplet nuclei are assumed to be fully and evenly mixed in the room.

| (1) |

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the ventilation and the macroscopic droplet nuclei concentration model (N = 4, I = 1).

The analytical solution of the equation becomes:

| (2) |

where is the indoor droplet nuclei concentration (ppm); is time (s); is the air exchange rate per second given by ; is the total volumetric generation rate of droplets by the infected people in the room; is the total volume of the room calculated as ; is the droplet deposition rate (the deactivation rate can be included, but is not considered in this study as it depends on the virus); is the initial indoor droplet nuclei concentration (ppm). Note that the air exchange rate throughout the room is the same as that for a single person ().

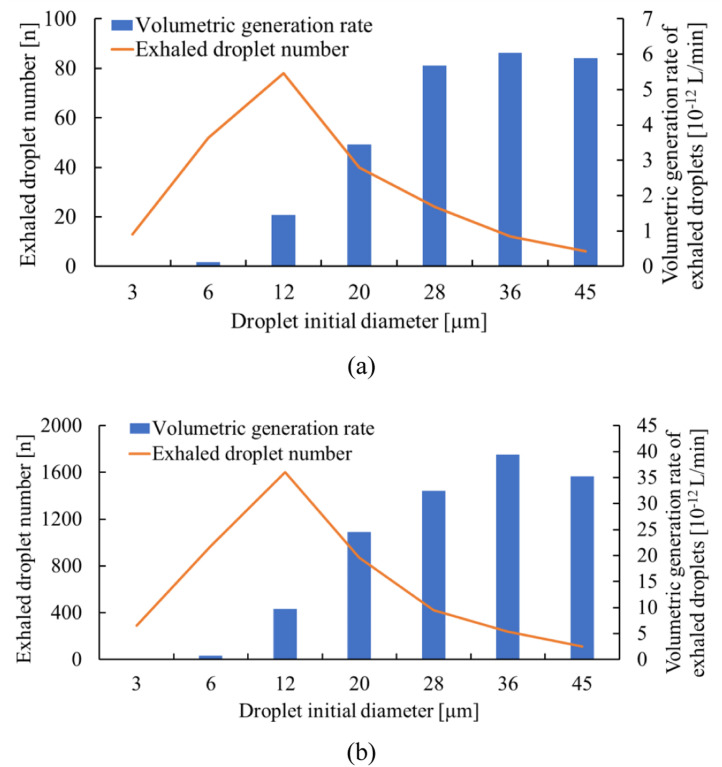

The volumetric generation rate of droplets containing infectious pathogens from a single source patient () was calculated based on the injected droplet number during prolonged talking (counting from “1” to “100”) and coughing as in Duguid (1946). The above droplet size distribution covers a wide range of droplet sizes and was chosen to facilitate comparison with exposure to short-range airborne route, although the distribution differs slightly from a more recent study (Somsen et al., 2020). Assuming that it takes T talk = 100 s (the time required for enunciating a number was taken as approximately 1 s (Gupta et al., 2010)) to finish counting, for talking can be calculated as the total exhaled droplet volume divided by the time duration of the respiratory activity. Note that the time duration for talking is only an estimation, and bias may exist between individuals with different talking behaviors. Numbers containing more syllables also require longer time for pronunciation (e.g., “ninety-nine” vs. “two”). The average talking speed of 1 s per number was adopted considering the compensation between numbers with fewer and more syllables. However, the treatment of coughing differs from that of talking. Although a single cough only takes approximately 0.5 s (Gupta et al., 2009), T cough = 306.4 s was adopted here, corresponding to the coughing frequency of asthma patients (Hsu et al., 1994). The intuition behind this is that people can talk continuously, but continuous coughing is unlikely. Therefore, we assumed that the droplets or virus generated during a single cough were distributed across a longer period until the next cough occurred.

Because the situation we studied here is extended short-range airborne exposure in a larger space, we took droplets with an initial diameter of <15 µm into consideration (<5 µm after full evaporation to their final size) in the long range, which can follow the airstream and travel long distances after evaporation. The environmental conditions included air temperature and humidity and were set at 25 °C, 50%, respectively. Fig. 3 shows the distribution of initially exhaled droplet number and volumetric generation rate per person for talking and coughing, respectively. As the droplet volume is proportional to the cube of the droplet diameter, peak values appear at different sizes. The overall generation rate, , is the product of the number of infected people (I) and of the generation rate per person () as shown in Eq. (3). For simplicity, the droplets were assumed to be expired continuously by the infected people.

| (3) |

where is the exhaled droplet number; is the droplet nuclei diameter after complete evaporation.

Fig. 3.

Volumetric generation rate of droplets and exhaled droplet number distribution during a) talking; b) coughing.

Three representative sizes from 3 µm to 12 µm were considered in the long range. The final droplet nuclei size after evaporation was 32.5% of their initial diameter (0.975–3.9 µm corresponding to 3–12 µm) (Wei and Li, 2015). The volumetric generation rate and indoor droplet nuclei concentration were calculated for each droplet diameter during talking and coughing, and the overall indoor concentration was the sum of concentrations under each droplet size.

We considered that before the presence of the infected individual, the initial indoor droplet nuclei concentration was zero ( ppm). Therefore, Eq. (2) is simplified as follows:

| (4) |

For comparison purposes, the calculated room average concentration of droplet nuclei was corrected to the corresponding initial droplet size at the mouth. Let be the corrected concentration at the mouth. The suggested correction is reasonable as we compared the volumetric inhalation of droplets at the mouth of the target, resulting in:

| (5) |

The volumetric exposure in the unit of μL for long-range airborne transmission can then be calculated as:

| (6) |

where is the inhalation flow rate, which is the same as that of the short-range exposure described in Chen et al. (2020). Thus, the exposure to the long-range airborne route depends on the droplet nuclei removal rate (, ), the room volume per person (), and the number of infected versus susceptible people (I, N). Compared with the commonly used Wells-Riley model, our model does not directly estimate the infection risk, but rather compare the long-range exposure to the short-range exposure. The existing Wells-Riley equation is not applicable to the short-range airborne (inhalation) exposure.

2.2. Short-range airborne exposure

The short-range airborne exposure (within 2 m) during talking and coughing was calculated by Chen et al. (2020) and details of the model can be found therein, while a brief description is provided in Supplementary Material. The short-range exposure was estimated at room conditions of 50% RH and 25 ℃.

Note that droplet evaporation is an ongoing process during short-range transport (<2 m), which means that droplets evaporate and change in size along the journey and may not have entirely evaporated to their final diameter when reaching 2 m. However, for the long-range airborne route, it was assumed that droplets had evaporated to their final diameter and become droplet nuclei. To be consistent with the long-range airborne exposure and facilitate comparison, the short-range exposure was also corrected to the initial droplet size at the target mouth as illustrated in Eq. (7). Droplets with initial diameter smaller than 50 µm and 12 µm were considered in the calculation of short-range and long-range exposure, respectively.

| (7) |

where is the short-range exposure after being corrected to the initial droplet size at the mouth; is the droplet volume at the distance of zero (unevaporated); is the droplet volume at the distance of x after evaporation; is the initial short-range volumetric exposure considering evaporation. Refer to the Supplementary Material or Chen et al. (2020) for short-range exposure calculation.

2.3. Droplet deposition rate

A size-dependent droplet deposition rate is required for the calculation of long-range exposure as illustrated in Eq. (1). The particle deposition rate changes with the diameter, but exhibits a flat shape at approximately 0.1–0.3 µm where the minimum value appears (Lai, 2002). Nearly all existing studies have considered droplet sizes of approximately 10 µm, which can well encompass the size range in this study (final droplet nuclei size <5 µm in the long range). We considered a linear fitting function using existing experimental data (Howard-Reed et al., 2003, Thatcher et al., 2002, Chao et al., 2003, Thatcher and Layton, 1995) for droplets smaller than 10 µm (R 2 = 0.7435). As seen in Fig. 4, the discrepancies increase for droplet sizes larger than 5 µm.

| (8) |

where is the size of the final droplet nucleus.

Fig. 4.

A summary of the droplet deposition rate data for particles smaller than 10 µm in the literature, and a simple fitted equation.

2.4. Effective short-range distance

The value of short-range exposure is a function of distance, and value rate of long-range exposure is a function of time. As illustrated by the orange and green lines in Fig. 1(b), each time span corresponds to a specific exposure value in the long range, and for that exposure value, a unique distance can be found on the short-range exposure curve. This distance is referred to as the effective short-range distance, or in short, effective distance at time t, denoted as to avoid confusion with the real distance x in the short range. Eventually, exposure at long range after a certain period is comparable to a short-range exposure scenario at the effective distance . Exposure in the short range here was defined as exposure to a talking person (i.e., counting from 1 to 100, lasting approximately 100 s, as a typical close contact interaction) or a person coughing once. Data fitting using a polynomial function was carried out for short-range talking (R2 = 0.9933) and coughing (R2 = 0.9876), and the fitted curve was used to find the effective distance. Once the spatial and temporal correspondence was found, an effective distance-versus-time figure could be readily drawn. Distances smaller than 0 m or greater than 2 m were considered invalid and excluded from the figure.

3. Results

3.1. Ventilation rate per person

To investigate the influence of the ventilation rate, it was assumed that I = N (all occupants were infected) with a constant room volume per person of 12 m3 under normal breathing. For simplicity, we first assumed that all occupants were present in the room at time t = 0. Fig. 5(a)-(b) allows a direct comparison of the spatial exposure profile due to the short-range airborne route and the temporal exposure profile due to the long-range airborne route, expressed in two sets of axes colored in red and blue respectively. To avoid a negative infinity in the logarithmic scale, long-range exposure is plotted starting from t = 1 min instead of zero. The left and right axes of the figures representing volumetric exposure are adjusted to the same range for comparison. The temporal exposure in the long range rises at a declining rate, and the spatial exposure due to inhalation within 2 m decays as we move away from the source mouth. Although the differences presented for each ventilation rate are minimal initially, they widen as time evolves.

Fig. 5.

Long- and short-range airborne exposure with different ventilation rates for a) talking; b) coughing. Effective short-range distances with different ventilation rates for c) talking; d) coughing. = 12 m3, I = N. Note: LR represents long-range and SR represents short-range.

The influence of the ventilation rate on the effective distance during talking and coughing is shown in Fig. 5(c)-(d). It is remarkable that coughing leads to much greater effective distances than talking within the same time length. This is primarily attributed to the more significant exposure load in the short range. Second, although a single cough is powerful, the time-averaged number of droplets is small due to the relatively low frequency of coughing, resulting in a weaker source strength in the long range.

The effective distance-versus-time figure directly provides us with a threshold safe period in a large space as long as a threshold distance for close contact is given. For instance, if 1.5 m is taken as the critical distance for social distancing, a room ventilated with 20 L/s per person will be safe for approximately 40 min during talking, and for approximately 100 min if the patients are coughing. Similarly, the curves intersect at 2 m at the top of the figures, to the left of which is the safe period given a critical social distance of 2 m. Note that the safe period may not in fact be safe in reality, as it was developed based on our predefined short-range interaction scenario with the assumption that there was no exposure beyond a certain threshold distance. Increasing the threshold distance would decrease the safe period, requiring a higher ventilation rate.

A lower ventilation rate leads to a shorter effective distance, with the effect being more prominent during coughing. During talking, the effect of the ventilation rate increasing is not obvious within a short period. However, it becomes increasingly important as time evolves, implying the necessity of increasing the ventilation rate where people are likely to stay longer. Unfortunately, after an excessively long time (over 200 min), the effect is extremely limited. The effective short-range distance decreases below 1 m even when the ventilation rate is 20 L/s for both talking and coughing. Note that in the case of very poor ventilation the long-range airborne exposure risk exists for all of the people in the room, which is different from the face-to-face close contact case in which normally only one susceptible person is involved.

3.2. Room volume per person

We considered all occupants to be infected (I = N) and investigated the effect of room volume per person. For our idealized room, when the ventilation rate per person () was fixed, any change in crowdedness (i.e., change in volume per occupied occupant ) did not lead to a change in the steady state-concentration of an inert gas such as CO2 (see Eq. (4); for inert gas, K = 0), but did affect the air change rate or the time constant of the system . As expired particles are our target pollutant here, the particle deposition coefficient K is a constant for a specific particle size, whereas the effective ventilation rate changes as the crowdedness changes. A smaller volume per person would lead to a smaller effective ventilation rate, and thus a greater steady-state concentration of the particles.

We consider the situation with a constant ventilation rate per person of = 5 L/s for different crowdedness values as shown in Fig. 6(a)-(b). As can be seen, the room volume per person has a much more prominent effect than the ventilation rate, as the decrease in reduces both and at the same time, whereas the decrease in only reduces . A decrease in significantly increases the long-range exposure at all times, whereas the effect of changing the ventilation rate is only observable at longer periods as shown in Fig. 5. The effect of a wider range of crowdedness is plotted in Fig. 6(c)-(d). The strategy of controlling transmission by increasing the room volume per person is obviously more effective than increasing the ventilation rate, especially during coughing. Taking 1.5 m as the threshold, a rather crowded space with can guarantee safety for merely 10 min when talking, whereas for , it can do so for at least 50 min

Fig. 6.

Long- and short-range airborne exposure with different room volume per person for (a) talking; (b) coughing. Effective short-range distances under different volume per person for c) talking; d) coughing. = 5 L/s, I = N. LR represents long-range and SR represents short-range.

3.3. Multiple infected individuals

In the above discussion we assumed that all occupants were infected (I = N) for a parametric study. Such a scenario only applies when N is infinitely large. In a room with only one infected person under a constant ventilation rate per person , an increase in the number of total occupants (N) would increase the overall ventilation in the room; hence, the steady-state concentration would decrease. The relative values of I and N as shown in Eq. (4) become crucial. Letting = 12 m3, = 5 L/s and N = 5, the effects of multiple infected individuals are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Long- and short-range airborne exposure with different numbers of infected people for a) talking; b) coughing. Effective short-range distances with different numbers of infected people for c) talking; d) coughing. = 12 m2, = 5 L/s, N = 5. LR represents long-range and SR represents short-range.

Rather than the absolute numbers of sources and targets, it is their proportion that matters. The results in Fig. 7 may also be interpreted as the percentage of infected people (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100% corresponding to I = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 respectively) under a constant ventilation rate and room volume per person, as shown by Eq. (4). Intuitively, a larger percentage of infected people causes greater exposure due to an overall higher droplet generation rate. The effectiveness of decreasing the number of infected sources is evidently greater that of either increasing the ventilation rate or decreasing the crowdedness; see Fig. 7(c)-(d). However, it is the least feasible strategy in practice. If we could precisely screen out and pinpoint and isolate infected individuals, there would never be any transmission to begin with. As shown in Fig. 7(c), for the normal case with one infected source talking, an adequate environment ( = 12 m2, = 5 L/s) can guarantee safety (threshold distance 1.5 m) for approximately 1.5 h according to our model.

3.4. Case studies

3.4.1. Alaska airplane case study

An analysis of the Alaska airplane outbreak case (Moser et al., 1979), as mentioned in the Introduction section, was carried out here, implementing our newly developed model to investigate the possibility of extended short-range airborne transmission. One of the total 54 passengers was the infected source. Rudnick and Milton (2003) estimated that the ventilation rate was only approximately 0.08 L/s to 0.4 L/s per passenger. There were approximately 3 m3 of compartment space per seat with the cabin height being 2 m. The airplane was delayed for 4.5 h due to engine failure. Based on the above information, the relationship between effective short-range distance versus time is shown in Fig. 8. The lower and upper bound of the ventilation rate per person are drawn in two separate figures.

Fig. 8.

Effective short-range distances for the Alaska airplane outbreak case for a ventilation rate of a) 0.08 L/s per person; b) 0.4 L/s per person. The blue dot dashed lines in (a) and (b) represent the effective short-range distances at the end of the period.

According to our data, the effective short-range distance is 1.0–1.2 m for talking at t = 270 min. For a ventilation rate of 0.08 L/s, the effective short-range distance is 1.86 m for coughing, whereas for a ventilation rate of 0.4 L/s the distance is greater than 2 m and is not shown in the figure. The probability of the infected source having close contact with all of those who became infected (72% of the other passengers) during this period must be low, although Brankston et al. (2007) argued that passengers could freely move around in the cabin. Our data shown here imply it is highly possible that extended short-range airborne transmission occurred.

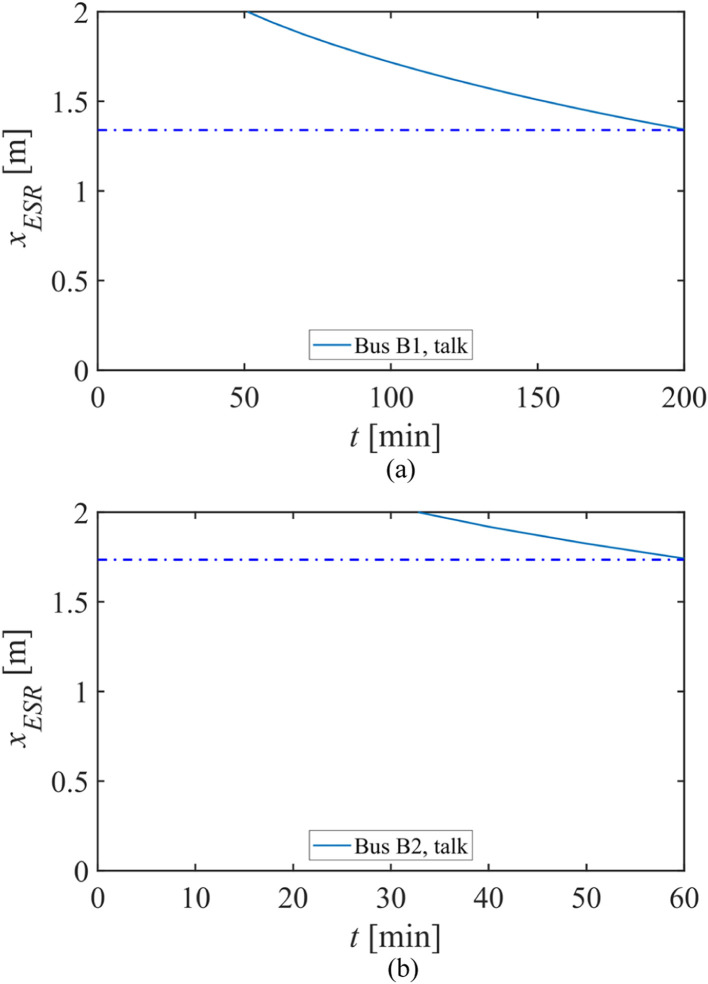

3.4.2. Hunan buses case study

The enclosed and crowded indoor environments in long-route coach buses usually experience high infection risk of respiratory diseases (Yang et al., 2020). Ou et al. (2021) investigated an outbreak of COVID-19 on two buses in Hunan province, China in January 2020, and a detailed field measurement of ventilation was also carried out. The infected source took bus B1 from Changsha to City D (duration of 3 h and 20 min), and then bus B2 from City D to Village H (duration of 1 h). Bus B1 was a larger bus, with 46 passengers in total, a ventilation rate per person of 1.72 L/s and a room area per person of 0.6 m2. Bus B2 was smaller with 17 passengers, a ventilation rate per person of 3.22 L/s and a room area per person of 0.72 m2. Eventually, eight travelers from B1 (seven when the source was present, one on the return trip) and two from B2 were infected. With the information provided, the effective short-range distances for the two buses are shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Effective short-range distances for the Hunan buses outbreak case on a) bus B1; b) bus B2. The blue dot-dashed lines in (a) and (b) represent the effective short-range distances at the end of the trip.

Regarding talking, the effective short-range distances on B1 and B2 are 1.34 m and 1.74 m at the end of the trip, respectively, which are smaller than the maximum measured distance between the source and the target (9.46 m for B1 and 2.33 m for B2). Therefore, we suggest that extended short-range airborne transmission occurred on bus B1. However, the same conclusion cannot be applied to B2 as the measured distance cannot rule out the possibility of close contact exposure. Nevertheless, poor ventilation, limited room area and longer exposure duration contributed to the higher infection rate observed on bus B1.

3.4.3. Guangzhou Restaurant X case study

A COVID-19 outbreak case in a Guangzhou restaurant (Restaurant X) in early January 2020 was reported by Li et al. (2021) and details can be found therein. Our model was utilized here again for case verification. There were 21 people, including the source infected person, in the contaminated ABC area (i.e., the area with Tables A–C), with a room volume per person of 4.84 m3. According to the onsite measurement data, an average ventilation rate of 0.9 L/s per person was provided. The infected source dined at Table A, and three individuals at Table B and two individuals at Table C were infected. In Li et al. (2021), the measured distances between the source and the three individuals of Table B are 1.4 m, 2.0 m and 2.4 m, respectively. For the two cases of Table C, the measured distances are 3.6 m and 4.6 m. The common dining time for Tables A and B was 53 min, and that for Tables A and C 75 min. Short-range effective distances for the individuals at Tables B and C are illustrated in Fig. 10. Different initial times were considered for exposure based on the arrival and departure time of the individuals.

Fig. 10.

Effective short-range distances for the Guangzhou Restaurant X outbreak case at a) Table B; b) Table C. The blue dot-dashed lines in (a) and (b) represent the effective short-range distances at the end of the period.

It can be seen from Fig. 10(a) that at t = 53 min, the effective short-range distance is 1.96 m. At time t = 75 min in Fig. 10(b), the value is 1.77 m. Additionally, leveraging Big Data tools, the researchers were able to view the CCTV records to check if any close contacts occurred, and to identify all of the close contacts of the infected using artificial intelligence techniques. After careful analysis of the CCTV video records, no other routes were observed that can explain this outbreak. A recent study by Zhang et al. (2021) further analyzed the video records and concluded that surface and close contact routes can be excluded from this outbreak. Therefore, we are relatively confident in concluding that extended short-range airborne transmission occurred among the three tables. Our results also indicate that a greater interpersonal distance (i.e., 2 m) should be implemented during the pandemic.

4. Discussion

4.1. Extended short-range airborne transmission explains how usually non-airborne diseases might be transmitted

The principal result of our study is that the extended short-range airborne route can occur in poorly ventilated and/or crowded environments in which normally only non-long-range airborne infection would occur under good ventilation. We have demonstrated that the extended short-range airborne mechanism adequately explains the Alaska plane outbreak of influenza, the Hunan buses outbreak of COVID-19, and the Guangzhou restaurant outbreak of COVID-19. The ventilation rate in all of these analyzed cases is lower than the range of 8–10 L/s per person commonly suggested by professional societies. Our results suggest that influenza or COVID-19 are normally non-long-range airborne diseases when sufficient ventilation is provided, but long-range airborne transmission occurs when the ventilation is insufficient. This in turn suggests the probable existence of short-range airborne transmission. Hence, we may hypothesize that the influenza or SARS-CoV-2 viruses can be transmitted by the short-range airborne route. This may have significant implications for the debate around transmission routes.

It may be useful to reinterpret the concept of obligate, preferential or opportunistic airborne transmission as suggested by Roy and Milton (2004). “Prevailing thought has focused on determining whether an infectious agent has ‘true’ airborne transmission. We find it more useful to classify the aerosol transmission of diseases as obligate, preferential, or opportunistic, on the basis of the agent’s capacity to be transmitted and to induce disease through fine-particle aerosols and other routes.” Roy and Milton (2004) defined obligate airborne transmission as “an infection that, under natural conditions, is initiated only through aerosols deposited in the distal lung”, preferential as “caused by agents that can naturally initiate infection through multiple routes but are predominantly transmitted by aerosols deposited in distal airways” and opportunistic as “infections that naturally cause disease through other routes (e.g., the gastrointestinal tract) but that can also initiate infection through the distal lung and may use fine-particle aerosols as an efficient means of propagating in favorable environments.” Here we considered crowded or poorly ventilated spaces as “favorable environments” for infection transmission, which the viruses use to their advantage to infect a person.

Our work suggests that airborne transmission can be considered as a spectrum of very close-range, short-range, long-range and very long-range. The three main parameters that determine the probability or risk of airborne infection are source strength, survival of virus and infection dose. Obviously, the risk of infection will be higher at very close range and lower at very long range. A weak source strength, a high ventilation dilution, a fast decay of virus and a high infection dose will diminish the very long-range or even the long-range airborne transmission. In this continuous spectrum, airborne transmission is not a question of “yes” or “no,” but “how much” or “under what conditions.” For windy outdoor environments where ventilation dilution is effective, the long-range airborne risk should be negligibly low. In enclosed spaces, sufficiently high ventilation and low occupancy become crucial.

Numerous studies have been conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, aiming to provide more insights in our understanding of the role of airborne transmission. SARS-CoV-2 was found to remain viable in aerosols for 3 h (Van Doremalen et al., 2020) and the RNA copies were detected in air in healthcare facilities (Feng et al., 2021), implying the potential for airborne transmission. The aerosol persistence results in Somsen et al. (2020) indicate that better ventilation substantially reduces the airborne time, and a laser light-scattering experiment shows a much quicker decay for larger droplets (Stadnytskyi et al., 2020). Reports of some outbreak cases during COVID-19 also provide probable evidence for airborne transmission (Miller et al., 2021, Li et al., 2021). Similar risk analysis was done by others (e.g., Smith et al., 2020), while our study mainly contributes by quantifying the ventilation requirements under specific conditions.

The extended short-range airborne transmission route itself is not new, but it serves as a novel concept that facilitates understanding of the airborne transmission of respiratory infections. The extended short-range airborne route is equivalent to the long-range airborne route. However, as we have demonstrated, this concept can explain the continuum of the short- and long-range airborne transmission of respiratory infections. The concept proved useful in interpreting the three observed outbreaks in the above case studies. If the continuum of the short- and long-range airborne transmission is widely accepted, the concept of extended short-range airborne transmission may become obsolete. However, other existing concepts such as the effective distance may still be useful for conceptual understanding of the airborne transmission route.

4.2. Appropriate prevention strategies require increasing ventilation rate and maintaining social distance

Our results strongly underline the significance of improving ventilation and maintaining social distancing in many indoor environments where most respiratory infection outbreaks occur, such as aged care homes, households and schools. Additionally, in indoor spaces where occupants tend to exercise heavily (i.e., with strong droplet generation rate), such as gyms, rehearsal rooms or dancing rooms, prevention strategies are even more urgently required due to higher emission rate (Buonanno et al., 2020).

Better ventilation reduces the risk of airborne transmission (Li et al., 2007). However, existing studies do not offer a quantitative ventilation rate for diminishing the long-range airborne transmission. Differently, in our approach we considered respiratory infections, for which there is not yet strong evidence of long-range airborne transmission even during a sufficiently long period for some of the most common diseases, e.g., influenza and COVID-19. Based on the avoidance of extended short-range airborne transmission for an equivalent short-range distance of 1.5 m with one infected source out of five people, we obtained that for a given room volume per person of 12 m3, a ventilation rate of 10 L/s per person (i.e., 3 air-changes per hour), was sufficient for at least 2 h, although for cases with distinct time and social distance requirements, the value may change accordingly.

Another conclusion was that the effect of a change in the room volume per person on airborne exposure is more significant than a change in the ventilation rate. Although increasing the ventilation rate was recommended by many studies and many institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing and avoiding close contact had a more prominent effect, which justifies the policy of home quarantine and lockdown. Similar findings have been found for other diseases. For example, Leung et al. (2004) and Reinhard et al. (1997) found an association between the risk of transmission of tuberculosis and overcrowded households. In a systematic review by the WHO an association was found between crowding and infection (Shannon et al., 2018). Finally, during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the basic reproduction number was as high as 3.0–3.6 for outbreaks in crowded schools (Lessler et al., 2009), while in general it was 1.3–1.7 (Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza, 2010).

In reality, poor ventilation often occurs simultaneously with overcrowding when few or no adjustments are made according to the number of occupants, especially for indoor spaces with central air conditioning systems. These two factors can usually be correlated, but are not equivalent. The worst combination of overcrowding and poor ventilation leads to the highest rates of pneumococcal disease (Hoge et al., 1994). The combined risk of overcrowding and a poorly ventilated environment may be referred to as a “pulling close” effect, in which people can be effectively in close contact even though they are far apart.

People tend to associate an airborne disease with extreme infectivity and even fear, probably due to historical reasons. Public health officials attempt to counter this by reassuring the public that a disease is not airborne so as to not to cause panic and fear, which would destabilize the community. Nevertheless, if not supported by evidence, such an assumption can produce adverse consequences by neglecting the importance of building ventilation and overcrowding as shown during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic that even World Health Organization (2020b) suggested that SARS-CoV-2 is not airborne. Aerosol transmission should be considered in precautionary control strategies for effective mitigation of SARS-CoV-2 (Tang et al., 2020). The extended short-range airborne route can be controlled by improving ventilation and decreasing occupancy (Morawska et al., 2020). Public health officials should endeavor to educate the public about the reality of transmission, which for the long-range airborne transmission case is not something to fear for most respiratory infections such as COVID-19 and influenza. To eliminate the extended short-range airborne route, the most effective intervention is to ensure sufficient room ventilation and low occupancy density.

4.3. Limitations of the study

This study has the following limitations. First, exposure in the volumetric unit μL was used, and droplets with initial diameter smaller than 3 µm were not considered. The investigation was mainly carried out from an engineering perspective. In general, different diseases have different biological characteristics in terms of quanta generation rate, critical exposure dose, virus infectivity and survival. This limitation poses the necessity for interdisciplinary collaboration. Second, it was assumed that the droplet nuclei were fully and evenly mixed in the indoor environment, which may be only applicable to rooms with mixing ventilation mode, but may not be applicable in some other cases with uneven air distribution (i.e., displacement ventilation, personalized ventilation, etc.). The pattern of indoor airflow is known to affect the infection risk (Qian et al., 2008), and proper installations of air-cleaning devices are crucial for practicality (Mui et al., 2009). We have focused on ventilation and deposition here. The effect by filtration and virus deactivation can be considered in a similar manner. Third, inhalation was considered merely through the mouth instead of the nose, although nasal inhalation may be more common. In the cases analyzed, the source patient may not be generating droplets continuously through talking or coughing.

5. Conclusions

Long-range airborne transmission is possible in crowded and poorly ventilated spaces, even for a disease that is restricted to non-long-range airborne transmission under good ventilation. We refer to this as the “extended short-range airborne” route. A short-range effective distance was suggested to connect the time in the long-range airborne route and the distance in the short-range airborne route. The results showed that a decrease in either the ventilation rate or the room volume per person, or an increase in the number of infected people, would reduce the respective distances. In a normal breathing scenario with one out of five people infected and a given room volume per person of 12 m3, to ensure an effective short-range distance of 1.5 m, we obtained that a ventilation rate of 10 L/s per person is needed to maintain safety for 2 h. Therefore, appropriate prevention strategies require increasing the ventilation rate and maintaining social distance simultaneously.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wenzhao Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Hua Qian: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration. Nan Zhang: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Fan Liu: Investigation. Li Liu: Investigation, Project administration. Yuguo Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a General Research Fund (grant number 17202719) and Collaborative Research Fund (grant number C7025-16G), both provided by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong SAR Government.

Editor: Dr. R Teresa

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126837.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- ASHRAE., 2020. COVID-19 (CORONAVIRUS) PREPAREDNESS RESOURCES. American Society of Heating, Ventilating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers. 〈https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/resources〉 (accessed 2 August 2021).

- Brankston G., Gitterman L., Hirji Z., Lemieux C., Gardam M. Transmission of influenza A in human beings. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007;7:257–265. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonanno G., Stabile L., Morawska L. Estimation of airborne viral emission: quanta emission rate of SARS-CoV-2 for infection risk assessment. Environ. Int. 2020;141 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao C.Y., Wan M.P., Cheng E.C. Penetration coefficient and deposition rate as a function of particle size in non-smoking naturally ventilated residences. Atmos. Environ. 2003;37:4233–4241. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Zhang N., Wei J., Yen H.L., Li Y. Short-range airborne route dominates exposure of respiratory infection during close contact. Build. Environ. 2020;176 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid J.P. The size and the duration of air-carriage of respiratory droplets and droplet-nuclei. Epidemiol. Infect. 1946;44:471–479. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400019288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B., Xu K., Gu S., Zheng S., Zou Q., Xu Y., Yu L., Lou F., Yu F., Jin T., Li Y., Sheng J., Yen H.L., Zhong Z., Wei J., Chen Y. Multi-route transmission potential of SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare facilities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;402 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Wei J., Lei H., Xu P., Cowling B.J., Li Y. Building ventilation as an effective disease intervention strategy in a dense indoor contact network in an ideal city. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J.K., Lin C.H., Chen Q. Flow dynamics and characterization of a cough. Indoor Air. 2009;19:517–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J.K., Lin C.H., Chen Q. Characterizing exhaled airflow from breathing and talking. Indoor Air. 2010;20:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge C.W., Reichler M.R., Dominguez E.A., Bremer J.C., Mastro T.D., Hendricks K.A., Musher D.M., Elliott J.A., Facklam R.R., Breiman R.F. An epidemic of pneumococcal disease in an overcrowded, inadequately ventilated jail. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;331:643–648. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409083311004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Reed C., Wallace L.A., Emmerich S.J. Effect of ventilation systems and air filters on decay rates of particles produced by indoor sources in an occupied townhouse. Atmos. Environ. 2003;37:5295–5306. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J.Y., Stone R.A., Logan-Sinclair R.B., Worsdell M., Busst C.M., Chung K.F. Coughing frequency in patients with persistent cough: assessment using a 24 h ambulatory recorder. Eur. Resp. J. 1994;7:1246–1253. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07071246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A.C.K. Particle deposition indoors: a review. Indoor Air. 2002;12:211–214. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2002.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessler J., Reich N.G., Cummings D.A.T., New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Swine Influenza Investigation Team Outbreak of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) at a New York City school. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:2628–2636. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C.C., Yew W.W., Tam C.M., Chan C.K., Chang K.C., Law W.S., Wong M.Y., Au K.F. Socio-economic factors and tuberculosis: a district-based ecological analysis in Hong Kong. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2004;8:958–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Hypothesis: SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission is predominated by the short‐range airborne route and exacerbated by poor ventilation. Indoor Air. 2021;31:921–925. doi: 10.1111/ina.12837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Chen Z. A balance-point method for assessing the effect of natural ventilation on indoor particle concentrations. Atmos. Environ. 2003;37:4277–4285. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Leung G.M., Tang J.W., Yang X., Chao C.Y., Lin J.Z., Lu J.W., Nielsen P.V., Niu J., Qian H., Sleigh A.C., Su H.J., Sundell J., Wong T.W., Yuen P.L. Role of ventilation in airborne transmission of infectious agents in the built environment-a multidisciplinary systematic review. Indoor Air. 2007;17:2–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Qian H., Hang J., Chen X., Cheng P., Ling H., Wang S., Liang P., Li J., Xiao S., Wei J., Liu L., Cowling B.J., Kang M. Probable airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a poorly ventilated restaurant. Build. Environ. 2021;196 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Li Y., Nielsen P.V., Wei J., Jensen R.L. Short‐range airborne transmission of expiratory droplets between two people. Indoor Air. 2017;27:452–462. doi: 10.1111/ina.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies D., Fanning A., Yuan L., FitzGerald J.M. Hospital ventilation and risk for tuberculous infection in Canadian health care workers. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000;133:779–789. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-10-200011210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S.L., Nazaroff W.W., Jimenez J.L., Boerstra A., Buonanno G., Dancer S.J., Kurnitski J., Marr L.C., Morawska L., Noakes C. Transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 by inhalation of respiratory aerosol in the Skagit Valley Chorale superspreading event. Indoor Air. 2021;31:314–323. doi: 10.1111/ina.12751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska L., Tang J.W., Bahnfleth W., Bluyssen P.M., Boerstra A., Buonanno G., Cao J., Dancer S., Floto A., Franchimon F., Haworth C., Hogeling J., Isaxon C., Jimenez J.L., Kurnitski J., Li Y., Loomans M., Marks G., Marr L.C., Mazzarella L., Melikov A.K., Miller S., Milton D.K., Nazaroff W., Nielsen P.V., Noakes C., Peccia J., Querol X., Sekhar C., Seppänen O., Tanabe S., Tellier R., Tham K.W., Wargocki P., Wierzbicka A., Yao M. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised? Environ. Int. 2020;142 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser M.R., Bender T.R., Margolis H.S., Noble G.R., Kendal A.P., Ritter D.G. An outbreak of influenza aboard a commercial airliner. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1979;110:1–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mui K.W., Wong L.T., Wu C.L., Lai A.C. Numerical modeling of exhaled droplet nuclei dispersion and mixing in indoor environments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;167:736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou, C., Hu, S., Luo, K., Yang, H., Hang, J., Cheng, P., Hai, Z., Xiao, S., Qian, H., Xiao, S., Jing, X., Xie, Z., Ling, H., Liu, L., Gao, L., Deng, Q., Cowling, B.J., Li, Y., 2021. Insufficient ventilation led to a probable long-range airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on two buses. submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Qian H., Li Y., Nielsen P.V., Hyldgaard C.E. Dispersion of exhalation pollutants in a two-bed hospital ward with a downward ventilation system. Build. Environ. 2008;43:344–354. [Google Scholar]

- REHVA., 2020. COVID-19 Guidance. 〈https://www.rehva.eu/activities/covid-19-guidance〉 (accessed 2 August 2021).

- Reinhard C., Paul W.S., Mcauley J.B. Epidemiology of pediatric tuberculosis in Chicago, 1974 to 1994: a continuing public health problem. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1997;313:336–340. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199706000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy C.J., Milton D.K. Airborne transmission of communicable infection-the elusive pathway. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:1710–1712. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick S.N., Milton D.K. Risk of indoor airborne infection transmission estimated from carbon dioxide concentration. Indoor Air. 2003;13:237–245. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2003.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman J.L., Kilbourne E.D. Airborne transmission of influenza virus infection in mice. Nature. 1962;195:1129–1130. doi: 10.1038/1951129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, H., Allen, C., Clarke, M., Dávila, D., Fletcher-Wood, L., Gupta, S., Keck, K., Lang, S., Ludolph, R., Kahangire, D.A., World Health Organization, 2018. WHO Housing and health guidelines: web annex A: report of the systematic review on the effect of household crowding on health.

- Smith S.H., Somsen G.A., Van Rijn C., Kooij S., Van Der Hoek L., Bem R.A., Bonn D. Aerosol persistence in relation to possible transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Phys. Fluids. 2020;32 doi: 10.1063/5.0027844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somsen G.A., van Rijn C., Kooij S., Bem R.A., Bonn D. Small droplet aerosols in poorly ventilated spaces and SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Lancet Resp. Med. 2020;8:658–659. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30245-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnytskyi V., Bax C.E., Bax A., Anfinrud P. The airborne lifetime of small speech droplets and their potential importance in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:11875–11877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006874117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Mao Y., Jones R.M., Tan Q., Ji J.S., Li N., Shen J., Lv Y., Pan L., Ding P., Wang X., Wang Y., Maclntyre C.R., Shi X. Aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2? Evidence, prevention and control. Environ. Int. 2020;144 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher T.L., Lai A.C., Moreno-Jackson R., Sextro R.G., Nazaroff W.W. Effects of room furnishings and air speed on particle deposition rates indoors. Atmos. Environ. 2002;36:1811–1819. [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher T.L., Layton D.W. Deposition, resuspension, and penetration of particles within a residence. Atmos. Environ. 1995;29:1487–1497. [Google Scholar]

- US CDC., 2021. Scientific Brief: SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. Updated May 7, 2021. 〈https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/sars-cov-2-transmission.html〉. (accessed 2 August 2021).

- Van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I., Lloyd-Smith J.O., De Wit E., Munster V.J. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Li Y. Enhanced spread of expiratory droplets by turbulence in a cough jet. Build. Environ. 2015;93:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Li Y. Airborne spread of infectious agents in the indoor environment. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016;44:S102–S108. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2020a. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions - Scientific Brief, 9 July 2020. 〈https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions〉 (accessed 2 August 2021).

- World Health Organization, 2020b. Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations - Scientific brief, 29 March 2020. 〈https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations〉 (accessed 2 August 2021).

- World Health Organization, 2021. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted? Updated 30 April 2021. 〈https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted〉 (accessed 2 August 2021).

- Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:1708–1719. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Ou C., Yang H., Liu L., Song T., Kang M., Lin H., Hang J. Transmission of pathogen-laden expiratory droplets in a coach bus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020;397 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Chen X., Jia W., Jin T., Xiao S., Chen W., Hang J., Ou C., Lei H., Qian H., Su B., Li J., Liu D., Zhang W., Xue P., Liu J., Weschler L.B., Xie J., Li Y., Kang M. Evidence for lack of transmission by close contact and surface touch in a restaurant outbreak of COVID-19. J. Infect. 2021;83:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Jia W., Lei H., Wang P., Zhao P., Guo Y., Dung C.H., Bu Z., Xue P., Xie J., Zhang Y., Cheng R., Li Y. Effects of human behavior changes during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on influenza spread in Hong Kong. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material