Abstract

Chronic liver disease is one of the leading causes of death in the United States. Coagulopathy is often a sequela of chronic liver disease, however, the role and regulation of coagulation components in chronic liver injury remain poorly understood. Clinical and experimental evidence indicate that misexpression of the procoagulant factor VIII (FVIII) is associated with chronic liver disease. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism of FVIII-induced chronic liver injury progression remains unknown. This review provides evidence supporting a pathologic role for FVIII in the development of chronic liver disease using both experimental and clinical models.

Keywords: Factor VIII, Chronic Live Injury, Portal Hypertension, Cirrhosis, Hepatitis C, Hemophilia A

Abbreviations used in this paper: CLD, chronic liver disease; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FHF, fulminant hepatic failure; FVIII, Factor VIII; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LMAN1, Lectin, Mannose Binding 1; mRNA, messenger RNA; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NO, nitric oxide; VWF, von Willebrand factor

Summary.

Coagulopathy and chronic liver diseases are closely interconnected. In this review article we provide evidences of the role of procoagulant Factor VIII in chronic liver disease.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) is among the leading causes of death in the United States.1 CLD also is responsible for approximately 70% of the total number of liver transplants every year.2 In most forms of CLD, progressive injury damages the liver parenchyma leading to inflammation, vascular remodeling, fibrosis, and angiogenesis.3, 4, 5, 6 Without effective treatment, CLD can lead to end-stage liver disease and liver failure, which contributes to nearly 1 million deaths per year worldwide.7

Coagulopathy is often a sequela of CLD because the liver damage causes impaired coagulation.8,9 With the exception of von Willebrand factor (VWF), all other coagulation-related proteins (Factor I, II, V, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, and XIII, and tissue factor) are synthesized in the liver9 and, thus, both acute and chronic liver failure may impair the synthesis of coagulation factors.10,11 The onset of cirrhosis complications such as variceal bleeding, portal hypertension, or infection/sepsis also may impair the coagulation cascade further.12,13 Moreover, clinical studies in cirrhosis patients and experimental studies in mouse models of CLD have suggested that perturbation of the coagulation cascade promotes acute liver toxicity and CLD.9,10,14, 15, 16, 17 Thus, the association of liver injury with coagulation extends beyond the impact of liver disease on the synthesis of coagulation factors to include a role for coagulation factor activity in the initiation and progression of CLD.

End-stage CLD frequently is associated with clinical bleeding and decreased levels of most procoagulant factors, with the notable exceptions of Factor VIII (FVIII) and VWF, which are increased (until late in the disease).10 Emerging evidence suggests that FVIII is a critical mediator of coagulation in CLD.10,11 In this review, we aim to provide a balanced view of the roles of FVIII in CLD based on studies in both mice and human beings. In addition, we briefly address the potential therapeutic implications of these results and describe the potential challenges and knowledge gaps to be addressed by future studies.

Hepatic Synthesis, Secretion, and Clearance of FVIII

FVIII is a plasma glycoprotein that is synthesized primarily in the liver.18 Although a few studies have shown the contribution of hepatocytes in FVIII synthesis,18, 19, 20, 21 liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are the predominant site of FVIII synthesis.18,22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 Among other organs, lung,31 spleen,32,33 and lymphatic tissues34 also have been implicated to produce FVIII. Despite the fact that the identity of FVIII-secreting cells was a long-standing debate in the past, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells now are considered the chief source for the level of circulating FVIII.

Immunohistochemical staining of FVIII in the liver has confirmed its presence in the vessels around the intrahepatic large bile ducts (peribiliary vascular plexus) (Figure 1A). Factor VIII is synthesized as a 330-kilodalton single-polypeptide chain with a domain structure (A1-A2-B-A3-C1-C2) that circulates in the plasma as a heterodimeric protein consisting of a metal ion-linked light chain and heavy chain35 (Figure 1B). The heavy chain (90–220 kilodaltons) contains the A1-A2-B domains and is heterogenous as a result of limited proteolysis within the B domain. The light chain (80 kilodaltons) consists of the A3-C1-C2 domains.

Figure 1.

FVIII is synthesized in hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of FVIII in wild-type liver shows its localization in the liver. (B) Schematic showing the structure of FVIII protein and its different cleaved forms.

Upon synthesis, mature FVIII polypeptide translocates to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for glycosylation. Within the ER, FVIII interacts with a number of chaperone proteins, including calreticulin, calnexin, and the IgG-binding protein,36, 37, 38 which causes FVIII retention in the ER. Moreover, FVIII is prone to protein misfolding, which altogether results in its low level of expression at the cellular level.39,40 Unfolded FVIII accumulates in the ER lumen and activates ER stress-response genes, leading to oxidative stress and apoptosis.39 Antioxidants have been shown to improve FVIII secretion and thus prevent ER stress–induced oxidative damage and apoptosis.41 Analysis of secreted FVIII into the plasma has shown that ER protein Ire1α regulates the secretion efficiency of FVIII.39 Loss of Inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endoribonuclease 1α (IRE1α) has been linked to chronic liver injury,42 suggesting a potential link of misfolded FVIII protein in CLD.

FVIII trafficking from ER to the Golgi complex is facilitated through interaction with the Lectin, Mannose Binding 1 (LMAN1)/Multiple Coagulation Factor Deficiency 2, ER Cargo Receptor Complex Subunit (MCFD2) complex.43 Mice lacking LMAN1 have completely blocked FVIII secretion.23 Secreted FVIII is associated with VWF in the sinusoids and circulates in the bloodstream in an inactive form.44 VWF stabilizes the structure of FVIII, prevents the nonspecific binding of FVIII to platelets and endothelial cells, and acts as a cofactor for thrombin-catalyzed cleavage of the FVIII light chain.45 For a complete description of FVIII structure and its interaction with VWF, readers are referred to the studies by Chavin,46 Vehar et al,47 and Fay.48

Upon injury to the blood vessels, FVIII is activated and separates from VWF, which permits FVIII interaction with platelets.49 Activated FVIII interacts with coagulation factor IX, which promotes a chain of additional chemical reactions that form a blood clot.50 Activated protein C and Factor Xa (FXa) also are known to deactivate FVIII.51 For a detailed role of FVIII in coagulation, readers are referred to the studies by Chavin,46 Lenting et al,52 and Mazurkiewicz-Pisarek et al.53

The endocytic trafficking and clearance of FVIII recently has gained much attention.54, 55, 56 The removal of FVIII from the bloodstream requires the presence of specialized clearance receptors. Low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein is considered one of the chief FVIII clearance receptors that localizes to the hepatocyte membrane.55 The endothelial lectin C-Type Lectin Domain Family 4 Member M (CLEC4M) also is shown to regulate FVIII clearance in both a VWF-dependent and -independent manner.57,58 CLEC4M binds to FVIII and promotes its internalization via clathrin-coated pit, followed by endosomal trafficking and lysosomal degradation of FVIII.59,60 Similarly, stabilin-2, a scavenger receptor expressed on the sinusoidal endothelial cells of the liver, spleen, and lymphatics, functions as a clearance receptor of FVIII. Although the interaction of VWF–FVIII and stabilin-2 was identified through genetic wide association study (GWAS),61 the stabilin-2–deficient murine model showed mechanistic details of stabilin 2–FVIII–VWF interaction by regulation of the half-life of VWF–FVIII and the immune response to VWF–FVIII concentrates.62 Among other factors, a number of hepatocyte- and macrophage-expressed asialoglycoprotein receptors such as Sialic Acid Binding Ig Like Lectin 5 (SIGLEC5) and teroid Receptor RNA Activator 1 (SR-A1) also have been reported to promote FVIII clearence.63,64 Thus, the liver plays a predominant role in FVIII synthesis, trafficking, and degradation as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Hepatic synthesis, secretion, and clearance of FVIII. (A) Schematic diagram showing the synthesis, secretion, trafficking, and degradation of FVIII in the liver. Upon its synthesis in the sinusoidal endothelial cells, FVIII associates with VWF. Upon its activation, FVIII gets cleaved and dissociated from VWF. Activated FVIII interacts with Factor IX and platelets and promotes a blood clot formation. The removal of FVIII from the bloodstream is promoted by a specialized clearance receptor low-density lipoprotein-receptor–related protein (LRP) that localizes to the hepatocyte membrane. ASGPR, Asialoglycoprotein receptor; FIXa, Factor IXa; FX, Factor X; LDLR, Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor; PCa, protein C.

Relevance of FVIII in CLD

Factor VIII and Portal Hypertension

Portal hypertension is defined as the pathologic increase in hepatic sinusoidal pressure, which causes increased intrahepatic resistance to portal blood flow and an increase in hepatic venous pressure gradient (<10–12 mm Hg).65 Several clinical studies have confirmed that the plasma FVIII level increases during portal hypertension.66, 67, 68 Cirrhosis is considered one of the predominant causes of portal hypertension.69 Portal hypertension–related variceal bleeding is a typical finding in cirrhosis that frequently is associated with increased FVIII in the serum of patients with moderate varices.70

Blockage of blood flow or the presence of a blood clot in the portal vein can cause portal hypertension.71 FVIII levels are significantly higher in patients with primary extrahepatic portal vein obstruction,66 even in the absence of cirrhosis. Higher levels of FVIII also are associated with an increased risk for deep vein thrombosis66 and thrombophilia-induced idiopathic extrahepatic portal vein obstruction with portal hypertension.55 In addition, a high level of FVIII is considered a risk factor for portal vein thrombosis in patients with CLD, and in children with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction secondary to CLD.68 In mice undergoing partial portal vein ligation, a widely used model of portal hypertension,72 plasma FVIII levels are significantly higher than in sham-operated murine controls.72

Although the molecular mechanism of FVIII increase in portal hypertension remains unknown, there are several hypotheses for changes in FVIII levels in portal hypertension. Dysfunctional sinusoidal endothelial cells (the source of FVIII) may contribute to the extrahepatic increase in FVIII levels during portal hypertension.72 Another reason for FVIII increases in portal hypertension is a reduction in nitric oxide (NO) levels.73 Loss of NO/endothelial NO synthase activity is associated with increased hepatic resistance, dysfunctional sinusoidal endothelial cells, portal vein thrombosis, and subsequent development of portal hypertension.74,75 Several studies have shown that NO negatively regulates FVIII and VWF expression.76,77 In cirrhotic conditions, NO activity is reduced, leading to increased intrahepatic vascular resistance.76,77 Figure 3 shows the schematic of FVIII in portal hypertension.

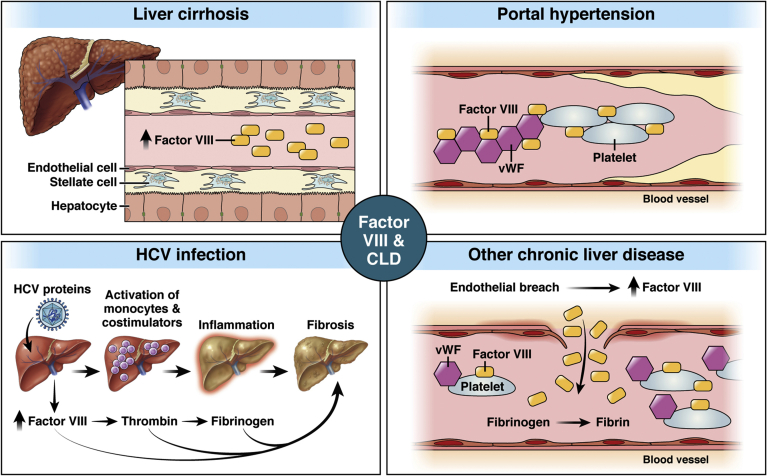

Figure 3.

The multifaceted role of factor VIII in chronic liver injury. (A) Schematic diagram showing the role of FVIII in various chronic liver disease models. In cirrhosis, the protein level of FVIII is increased in the plasma during advanced stages. In hepatitis C, FVIII expression is inhibited, leading to accumulation of fibrinogen and associated injury. In portal hypertension, FVIII increasingly is found to be increased and to form a complex with VWF in the plasma. In all other CLD models, an endothelial breach resulting from injury is associated with misexpression of FVIII in both liver and plasma.

Factor VIII and Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is characterized by persistent fibrosis and nodule formation leading to alteration of the normal lobular organization of the liver.78 Cirrhosis is one of the frequent clinical outcomes in all CLD (including viral infections, toxins, hereditary conditions, or autoimmune processes).65 Numerous clinical reports have confirmed a significant increase in plasma FVIII levels in cirrhotic patients, specifically during the advanced/late stages of cirrhosis.79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84

Although the exact reason for FVIII increase in cirrhosis is not known, there are several hypotheses for how FVIII levels are changed during cirrhosis. Cytokine release from the necrotic tissue of cirrhotic livers can lead to increased FVIII synthesis.11,12 Extrahepatic sites of FVIII synthesis85, 86, 87 (the spleen, kidney, lungs, and endothelium) also are speculated to be the cause of increased FVIII synthesis. Other possible causes of increased FVIII levels include abnormal protein production by the endothelium, misfolding of FVIII that interfere with its secretion,88 impaired catabolism of normal proteins,39 and factors regulating FVIII including increased hepatic VWF biosynthesis or decreased low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein expression or protein C deficiency.80,89

An increase in FVIII expression can occur as a result of impaired clearance of hemostatic complexes during advanced stages of cirrhosis.81 Among other factors, lipopolysaccharide90 recently was shown to be a potential trigger of FVIII release.75 Interestingly, despite a significant increase in protein level, the messenger RNA (mRNA) level of FVIII was reduced in these patients, suggesting a post-translational increase of the FVIII protein level in cirrhosis.91,92

Because cirrhotic patients frequently show higher FVIII, VWF antigen, and a FVIII-to–protein C ratio, FVIII has a significant potential to be used as a biomarker to independently predict new onset of ascites, variceal bleeding, and mortality in cirrhotic patients.79 Figure 3 shows the schematic of FVIII in liver cirrhosis.

Factor VIII and Hepatitis C

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a primary global health concern, with approximately 71 million chronically infected people.93 HCV infection can increase the risk of developing end-stage CLD and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).94 FVIII deficiency (hemophilia A) has been associated with HCV infections,95 predominantly resulting from exposure to virally contaminated blood. Patients with hemophilia infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HCV after treatment with a contaminated FVIII concentrate frequently developed cirrhosis and HCC.96,97

Although HCV infection is not known to induce the development of FVIII inhibitors,98 some patients with HCV–HIV co-infection showed decreased FVIII levels associated with the presence of a FVIII inhibitor95 when treated with interferon-α for hepatitis C.99 However, future research is needed to understand the mechanistic detail of inhibitor formation in viral hepatitis.

Acquired FVIII inhibitors (autoantibodies) are one of the most prominent autoantibodies that influence the clotting cascade.99 Although the development of inhibitors against FVIII has been observed in patients with HCV infection,95 whether FVIII inhibitor formation leads to progression or onset of acute and chronic hepatitis C is unknown. Future research consisting of both experimental and clinical studies is needed to better characterize the role of FVIII in hepatitis C pathogenesis, disease associations, and optimal disease management. Regardless of past HCV exposure, the current risk is essentially nonexistent with current FVIII products and FVIII replacement therapy is encouraged to prevent or treat bleeding.

Factor VIII and Fibrosis

Fibrosis refers to accumulation of scar tissue in the liver, which, if left untreated, can lead to cirrhosis and HCC.4 The coagulation cascade has been shown to influence fibrosis.15 Several studies have confirmed that hepatic inflammation and fibrosis are associated with increased expression of FVIII.15 Immunohistochemically, FVIII-related antigen, which was not observed in the healthy sinusoidal endothelial cells, was found to be localized in the capillaries within the pericellular fibrotic region.91 These results suggest that progression of fibrosis to cirrhosis is associated with the change in structural and immunohistochemical characteristics of the sinusoidal endothelial cells.100

Patients with hemophilia and chronic HCV infection show an increased rate of fibrosis progression with a Meta-analysis of Histological Data in Viral Hepatitis (Metavir) score of ≥3 on a transjugular liver biopsy specimen.101 Along with FVIII, increased α-fetoprotein levels, increasing age, and past HCV treatment are risk factors in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis.101 Although the mechanism of altered coagulation in fibrosis remains unknown, it is hypothesized that tissue ischemia, parenchymal extinction, and direct thrombin-mediated stellate cell activation via protease activated receptor 1 (PAR-1) causes changes in the coagulation cascade, including FVIII activation.15

Factor VIII and Other Models of CLD

Misexpression of FVIII also has been associated with other models of CLD such as drug-induced hepatic failure, alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver diseases, and HCC. Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) in human beings is known to cause a dramatic decrease in most hemostatic proteins, except FVIII, which shows a significant increase at the onset of the disease.102 One of the causes of FHF is acetaminophen overdose. However, when mice were treated with acetaminophen to produce FHF, contrary to the observation in human FHF, these mice manifested markedly reduced FVIII activity along with liver injury and death.103,104 A similar study performed in pigs also showed that acetaminophen overdose could change to a hypercoagulable state from a hypocoagulable state with a significant reduction in FVIII.105 In these models, VWF levels were only mildly reduced, as also shown in patients, suggesting that the hypocoagulation is not owing to the loss of VWF.

Alcoholic cirrhosis is a predominant cause of liver failure and liver-related mortality. Studies have shown a significant increase in FVIII in the sinusoidal cells106 of alcoholic cirrhosis patients, eventually leading to coagulation abnormalities.107 Despite the consistent increase in FVIII, not much is known about its role and regulation in alcoholic cirrhosis. Stress-induced FVIII synthesis and altered characteristics of sinusoidal endothelial cells may be the potential reasons FVIII increases in ALD.108

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common metabolic disorder with a global estimate of 25% of adults living with this disease throughout the world.109 NAFLD progression is associated with thrombotic vascular disease and hemostatic alterations.110 Studies also have shown that NAFLD-like conditions increase clotting factor levels in human beings, including the FVIII level as well as the VWF level,111 both of which are known to be associated with inflammation and acute-phase reactions. However, the mechanism and effect of the FVIII increase in NAFLD disease progression are not known.

Among other CLDs, acute liver failure also has been associated with an increase of plasma FVIII level.112,113 Table 1 summarizes the association of FVIII in CLDs from clinical studies.

Table 1.

Evidence in Support of a Role of FVIII in Chronic Liver Disease With Potential Mechanisms Involved

| Disease | Clinical evidence | Experimental evidence | Potential mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | ↑ Plasma FVIII levels in cirrhotic patients79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84 ↓ Hepatic FVIII mRNA level of FVIII during cirrhosis91,92 ↑ Plasma FVIII levels in cirrhosis without portal vein thrombosis81 ↓ Plasma FVIII levels cirrhotic with portal vein thrombosis81 |

Compromised clearance of hemostatic complexes81 Cytokine release from the necrotic tissue of cirrhotic liver11,12 Extrahepatic sites of FVIII synthesis85, 86, 87 Abnormal protein production/misfolding of FVIII88 and impaired catabolism39 LPS induced FVIII release75 Increased hepatic VWF biosynthesis or decreased level of LRP/protein C80,89 |

|

| Portal hypertension | ↑ Plasma FVIII levels in primary extrahepatic portal vein obstruction66 ↑ Plasma FVIII levels in thrombophilia-induced IEPVO, with portal hypertension55 ↑ Plasma FVIII in levels in PVT patients with CLD123 ↑ Plasma FVIII levels Children with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction68 |

↑ FVIII levels followed by portal vein ligation in murine models68 | Impaired function of sinusoidal endothelial cells74,75 Reduction in NO level76,77 |

| Hepatitis C | ↓ Plasma FVIII levels95 | Development of human FVIII inhibitor95 Hemophilia patients infected with HIV124,125 |

|

| Acute liver failure Acetaminophen-induced liver failure Drug-induced liver failure FHF |

↑ Plasma FVIII level112,113 ↓ Plasma FVIII103 ↓ Plasma FVIII has been associated with thioxanthenes,103 interferon,95 and fludarabine103 ↑ Plasma FVIII level102 |

A study performed in pigs showed that acetaminophen overdose leads to ↓ FVIII70 | Inhibitor formation99 |

| Other chronic liver injury models: Alcoholic cirrhosis NAFLD |

↑ FVIII in the sinusoidal cells106,107 ↑ FVIII level111 |

FVIII-deficient mice on a high-fat diet developed NAFLD phenotypes122 | |

| Hepatic fibrosis | ↑ FVIII level associated with liver fibrosis17 Hemophilia patients with chronic HCV infection showed reduced rate of fibrosis or liver disease progression73 FVIII-related antigen was found in the capillaries adjoining the pericellular fibrotic region100 |

Tissue ischemia, parenchymal extinction, and direct thrombin-mediated stellate cell activation via PAR-1 cleavage17 Coagulation cascade activity by activation of the hepatic stellate cells101 The structural and immunohistochemical changes of sinusoidal endothelial cells74 |

|

| Liver surgery | ↑ Plasma FVIII level during the intraoperative and early postoperative period41,43 ↑ FVIII level in patients undergoing liver transplant41,43,87 ↑ FVIII level in children undergoing liver transplant117 |

||

| Liver regeneration | ↑ FVIII plasma level92 ↓ FVIII mRNA expression in the liver92 |

Delay in the inactivation of plasma FVIII caused by increased VWF in plasma or decreased FVIII clearance in the liver92 Alteration of the intracellular trafficking pathway of FVIII and its rapid release from the storage sites after partial hepatectomy92 |

IEPVO, idiopathic extrahepatic portal vein obstruction; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LRP, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein; PAR-1, protease activated receptor 1; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

Factor VIII and Liver Surgery

In liver transplantation surgeries, substantial changes in coagulation components take place.114,115 Several studies have reported that during the intraoperative and early postoperative phase, the plasma FVIII level usually increases.114,115 Patients with end-stage liver disease undergoing liver transplantation consistently have higher FVIII levels than patients who survived had end stage liver disease but did not undergo treatments such as liver transplantation,116 consistent with the severity of their liver disease and criteria for transplantation based on the severity of end-stage liver disease. Studies have shown that FVIII levels also are increased in children undergoing liver transplantation.117

Factor VIII and Hemophilia A–Related Liver Disease

Hemophilia A is a rare X-linked recessive bleeding disorder caused by the deficiency or absence of FVIII.78,79 Because hemophilia etiology is heterogeneous (caused by different mutations in the F8 gene),80 it is difficult to study the pathophysiology of hemophilia A–associated comorbidities. However, there are several reports of liver morbidities associated with hemophilia A.76,81, 82, 83

Infection with HCV is the most common liver pathophysiology associated with hemophilia A (seen mostly in patients age ≥60 y), which causes significant morbidity and mortality. Because of the requirement of blood derivatives, several patients with hemophilia were exposed to HCV infection in the past, until HCV testing became widely available. In addition, because of the occasional development of cirrhosis and HCC, hemophilia patients also are considered for liver transplantation.118

Although hepatitis C infection is the leading cause of most hemophilia-associated liver injuries, co-infection with HIV (owing to contamination of the plasma donor pool) also has been reported to accelerate the progression to end-stage liver disease in patients with hemophilia.118,119

HCC is another comorbidity associated with hemophilia. Older hemophilia patients are at increased risk for HCV-associated HCC and HIV-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma,120 although the latter have been greatly reduced since the introduction of antiretroviral therapy in the mid-1990s. Age (>45 y), HCV or HIV infection, cirrhosis, and increased levels of α-fetoprotein are the risk factors for HCC development in hemophilia.120 HCC is considered an important cause of mortality in patients with hemophilia, with a standardized mortality ratio of 17.2 (95% CI, 5.2–35.9).121

Bleeding from esophageal varices as a result of the lack of FVIII is another serious clinical morbidity in hemophilia A.16,74 There are also increasing reports confirming the association of severe hemophilia A with the development of portal hypertension and age-induced organ injury.81 A few clinical reports have shown the development of chronic persistent hepatitis with early cirrhosis in hemophilia patients.82

End-stage liver disease in hemophilia patients worsens with age.121 However, liver biopsies are not performed routinely in these patients because of the increased risk of hemorrhage and the expense of a high dose of clotting factors. Thus, the pathophysiology of advanced liver diseases in hemophiliac patients remains largely unidentified.

Use of a Factor VIII–Deficient Murine Model to Study CLD

The FVIII-deficient murine model has been useful in studying the role and regulation of FVIII in CLDs. Using both a FVIII-deficient22 and LMAN-deficient23 (which impairs FVIII secretion) murine model, it was first shown that sinusoidal endothelial cells are the chief source of FVIII synthesis.

Loss of FVIII in mice was associated with low-grade hepatic inflammation. Expression of inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor-α, CD45, and Toll-like receptor 4 were increased in the livers of FVIII-deficient mice.22 Moreover, macrophage activation also was associated with FVIII loss, indicating that FVIII deficiency results in chronic inflammation in the liver, which could be the predominant cause for CLD progression in FVIII-deficient mice. A recent study also has shown the role of FVIII in NAFLD pathogenesis. The FVIII-deficient mice fed a high-fat diet developed hepatic steatosis, fibrosis, impaired energy metabolism, decreased platelet count, up-regulated de novo fatty acid synthesis, and lipid accumulation.122

FVIII deficiency also has been linked to liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Progressive loss of FVIII mRNA expression was shown to be associated with partial hepatectomy in mice.92 However, plasma FVIII showed a significant increase along with a reduction of mRNA expression in the liver.92 Increased FVIII protein in the plasma of the regenerating liver could be owing to a delay in the inactivation of plasma FVIII caused by increased VWF in plasma or decreased FVIII clearance in the liver. In addition, alteration of the intracellular trafficking of FVIII after a partial hepatectomy and the rapid release of FVIII from the storage sites also may contribute.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Studies over the past 2 decades have identified a prominent association of FVIII with CLDs. Several take-home messages have emerged from these provocative studies indicating the potential application of FVIII as a marker for inflammation, acute phase reactants, infection, and CLDs. Similarly, liver diseases with a reduced level of FVIII, such as acetaminophen-induced liver injury, hepatitis C, and acute liver failure, do benefit from FVIII replacement therapy with reduced bleeding risk, especially in patients with thrombocytopenia resulting from portal hypertension.

In considering the clinical implications of the findings related to FVIII in CLDs, it will be important to identify whether an increase in FVIII is an underlying cause or an effect of CLD-induced rebalanced hemostasis. FVIII, in many circumstances, exerts context-dependent effects in settings of both chronic injury and coagulation defects, thus it remains unclear whether the increase in FVIII during later stages of CLDs is owing to impaired trafficking/degradation, inflammation, or increased synthesis. Similarly, the role of other coagulation components such as VWF, factor IX, or platelets in FVIII regulation during CLDs are not completely understood.

Therefore, it is possible that utilization of mice with FVIII deficiency and overexpression may yield mechanistic insight into the exact role of FVIII in CLDs. In conclusion, FVIII appears to be a viable and attractive biomarker for CLD that may be used to predict CLD-induced cirrhosis and hepatic failure. With respect to FVIII and CLD, there is a true opportunity for creative translation of basic research to the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

TPS wrote the manuscript. SG helped in initial reference searching, TK helped with table making. MR provided guidance and suggestions for edits.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This was funded by a pilot grant (P3HVB) from Vascular Medicine Institute, University of Pittsburgh.

References

- 1.Lozano R., Naghavi M., Foreman K., Lim S., Shibuya K., Aboyans V., Abraham J., Adair T., Aggarwal R., Ahn S.Y., AlMazroa M.A., Alvarado M., Anderson H.R., Anderson L.M., Andrews K.G., Atkinson C., Baddour L.M., Barker-Collo S., Bartels D.H., Bell M.L., Benjamin E.J., Bennett D., Bhalla K., Bikbov B., Bin Abdulhak A., Birbeck G., Blyth F., Bolliger I., Boufous S., Bucello C., Burch M., Burney P., Carapetis J., Chen H., Chou D., Chugh S.S., Coffeng L.E., Colan S.D., Colquhoun S., Colson K.E., Condon J., Connor M.D., Cooper L.T., Corriere M., Cortinovis M., Courville De Vaccaro K., Couser W., Cowie B.C., Criqui M.H., Cross M., Dabhadkar K.C., Dahodwala N., De Leo D., Degenhardt L., Delossantos A., Denenberg J., Des Jarlais D.C., Dharmaratne S.D., Dorsey E.R., Driscoll T., Duber H., Ebel B., Erwin P.J., Espindola P., Ezzati M., Feigin V., Flaxman A.D., Forouzanfar M.H., Fowkes F.G.R., Franklin R., Fransen M., Freeman M.K., Gabriel S.E., Gakidou E., Gaspari F., Gillum R.F., Gonzalez-Medina D., Halasa Y.A., Haring D., Harrison J.E., Havmoeller R., Hay R.J., Hoen B., Hotez P.J., Hoy D., Jacobsen K.H., James S.L., Jasrasaria R., Jayaraman S., Johns N., Karthikeyan G., Kassebaum N., Keren A., Khoo J.P., Knowlton L.M., Kobusingye O., Koranteng A., Krishnamurthi R., Lipnick M., Lipshultz S.E., Lockett Ohno S., Mabweijano J., MacIntyre M.F., Mallinger L., March L., Marks G.B., Marks R., Matsumori A., Matzopoulos R., Mayosi B.M., McAnulty J.H., McDermott M.M., McGrath J., Memish Z.A., Mensah G.A., Merriman T.R., Michaud C., Miller M., Miller T.R., Mock C., Mocumbi A.O., Mokdad A.A., Moran A., Mulholland K., Nair M.N., Naldi L., Narayan K.M.V., Nasseri K., Norman P., O’Donnell M., Omer S.B., Ortblad K., Osborne R., Ozgediz D., Pahari B., Pandian J.D., Panozo Rivero A., Perez Padilla R., Perez-Ruiz F., Perico N., Phillips D., Pierce K., Pope C.A., Porrini E., Pourmalek F., Raju M., Ranganathan D., Rehm J.T., Rein D.B., Remuzzi G., Rivara F.P., Roberts T., Rodriguez De León F., Rosenfeld L.C., Rushton L., Sacco R.L., Salomon J.A., Sampson U., Sanman E., Schwebel D.C., Segui-Gomez M., Shepard D.S., Singh D., Singleton J., Sliwa K., Smith E., Steer A., Taylor J.A., Thomas B., Tleyjeh I.M., Towbin J.A., Truelsen T., Undurraga E.A., Venketasubramanian N., Vijayakumar L., Vos T., Wagner G.R., Wang M., Wang W., Watt K., Weinstock M.A., Weintraub R., Wilkinson J.D., Woolf A.D., Wulf S., Yeh P.H., Yip P., Zabetian A., Zheng Z.J., Lopez A.D., Murray C.J.L. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuppan D., Afdhal N.H. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838–851. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabo G., Petrasek J. Inflammasome activation and function in liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:387–400. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koyama Y., Brenner D.A. Liver inflammation and fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:55–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI88881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández M., Semela D., Bruix J., Colle I., Pinzani M., Bosch J. Angiogenesis in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2009;50:604–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulon S., Heindryckx F., Geerts A., Van Steenkiste C., Colle I., Van Vlierberghe H. Angiogenesis in chronic liver disease and its complications. Liver Int. 2011;31:146–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J., Murphy S.L., Kochanek K.D., Bastian B.A. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;64:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senzolo M., Burra P., Cholongitas E., Burroughs A.K. New insights into the coagulopathy of liver disease and liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7725–7736. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldwell S.H., Hoffman M., Lisman T., Macik B.G., Northup P.G., Reddy K.R., Tripodi A., Sanyal A.J., Bass N., Blei A.T., Fallon M., Gabriel D., Gines P., Grant P., Kowdley K., Lee S., Munoz S., Wanless I., Al-Osaimi A.M., Berg C.I., Balogun R., Bleck T., Bogdonoff D.L., Martoff A., Mintz P., Pruett T.L. Coagulation disorders and hemostasis in liver disease: pathophysiology and critical assessment of current management. Hepatology. 2006;44:1039–1046. doi: 10.1002/hep.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lisman T., Caldwell S.H., Burroughs A.K., Northup P.G., Senzolo M., Stravitz R.T., Tripodi A., Trotter J.F., Valla D.C., Porte R.J. Hemostasis and thrombosis in patients with liver disease: the ups and downs. J Hepatol. 2010;53:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kavanagh C., Shaw S., Webster C.R.L. Coagulation in hepatobiliary disease. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2011;21:589–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2011.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qamar A.A., Grace N.D. Abnormal hematological indices in cirrhosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:441–445. doi: 10.1155/2009/591317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russo F.P., Zanetto A., Campello E., Bulato C., Shalaby S., Spiezia L., Gavasso S., Franceschet E., Radu C., Senzolo M., Burra P., Lisman T., Simioni P. Reversal of hypercoagulability in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis after treatment with direct-acting antivirals. Liver Int. 2018;38:2210–2218. doi: 10.1111/liv.13873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luyendyk J.P., Schoenecker J.G., Flick M.J. The multifaceted role of fibrinogen in tissue injury and inflammation. Blood. 2019;133:511–520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-818211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anstee Q.M., Dhar A., Thursz M.R. The role of hypercoagulability in liver fibrogenesis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganey P.E., Luyendyk J.P., Newport S.W., Eagle T.M., Maddox J.F., Mackman N., Roth R.A. Role of the coagulation system in acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Hepatology. 2007;46:1177–1186. doi: 10.1002/hep.21779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muciño-Bermejo J., Carrillo-Esper R., Uribe M., Méndez-Sánchez N. Coagulation abnormalities in the cirrhotic patient. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:713–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wion K.L., Kelly D., Summerfield J.A., Tuddenham E.G.D., Lawn R.M. Distribution of factor VIII MRNA and antigen in human liver and other tissues. Nature. 1985;317:726–729. doi: 10.1038/317726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingerslev J., Christiansen B.S., Heickendorff L., Petersen C.M. Synthesis of factor VIII in human hepatocytes in culture. Thromb Haemost. 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zelechowska M.G., Van Mourik J.A., Brodniewicz-Proba T. Ultrastructural localization of factor VIII procoagulant antigen in human liver hepatocytes. Nature. 1985 doi: 10.1038/317729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biron-Andréani C., Bezat-Bouchahda C., Raulet E., Pichard-Garcia L., Fahre J.M., Saric J., Baulieux J., Schved J.F., Maurel P. Secretion of functional plasma haemostasis proteins in long-term primary cultures of human hepatocytes. Br J Haematol. 2004 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahs S.A., Hille M.T., Shi Q., Weiler H., Montgomery R.R. A conditional knockout mouse model reveals endothelial cells as the principal and possibly exclusive source of plasma factor VIII. Blood. 2014 doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-555151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Everett L.A., Cleuren A.C.A., Khoriaty R.N., Ginsburg D. Murine coagulation factor VIII is synthesized in endothelial cells. Blood. 2014 doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-554501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahani T., Covens K., Lavend’homme R., Jazouli N., Sokal E., Peerlinck K., Jacquemin M. Human liver sinusoidal endothelial cells but not hepatocytes contain factor VIII. J Thromb Haemost. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jth.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stel H.V., Van der Kwast T.H., Veerman E.C.I. Detection of factor VIII/coagulant antigen in human liver tissue. Nature. 1983 doi: 10.1038/303530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan J., Dinh T.T., Rajaraman A., Lee M., Scholz A., Czupalla C.J., Kiefel H., Zhu L., Xia L., Morser J., Jiang H., Santambrogio L., Butcher E.C. Patterns of expression of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor by endothelial cell subsets in vivo. Blood. 2016 doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-684688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Do H., Healey J.F., Waller E.K., Lollar P. Expression of factor VIII by murine liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999 doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webster W.P., Zukoski C.F., Hutchin P., Reddick R.L., Mandel S.R., Penick G.D. Plasma factor VIII synthesis and control as revealed by canine organ transplantation. Am J Physiol. 1971 doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.220.5.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumaran V., Benten D., Follenzi A., Joseph B., Sarkar R., Gupta S. Transplantation of endothelial cells corrects the phenotype in hemophilia A mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2005 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Follenzi A., Benten D., Novikoff P., Faulkner L., Raut S., Gupta S. Transplanted endothelial cells repopulate the liver endothelium and correct the phenotype of hemophilia A mice. J Clin Invest. 2008 doi: 10.1172/JCI32748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacquemin M., Neyrinck A., Hermanns M.I., Lavend’homme R., Rega F., Saint-Remy J.M., Peerlinck K., Van Raemdonck D., Kirkpatrick C.J. FVIII production by human lung microvascular endothelial cells. Blood. 2006 doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aronovich A., Tchorsh D., Katchman H., Eventov-Friedman S., Shezen E., Martinowitz U., Blazar B.R., Cohen S., Tal O., Reisner Y. Correction of hemophilia as a proof of concept for treatment of monogenic diseases by fetal spleen transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607012103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L., Xia S., Seifert J. Transplantation of spleen cells in patients with hemophilia A - A report of 20 cases. Transpl Int. 1994 doi: 10.1007/BF00327088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groth C.G., Hathaway W.E., Gustafsson Å., Geis W.P., Putnam C.W., Björkén C., Porter K.A., Starzl T.E. Correction of coagulation in the hemophilic dog by transplantation of lymphatic tissue. Surgery. 1974 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miao H.Z., Sirachainan N., Palmer L., Kucab P., Cunningham M.A., Kaufman R.J., Pipe S.W. Bioengineering of coagulation factor VIII for improved secretion. Blood. 2004 doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marquette K.A., Pittman D.D., Kaufman R.J. A 110-amino acid region within the A1-domain of coagulation factor VIII inhibits secretion from mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1995 doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swaroop M., Moussalli M., Pipe S.W., Kaufman R.J. Mutagenesis of a potential immunoglobulin-binding protein-binding site enhances secretion of coagulation factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 1997 doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pipe S.W., Morris J.A., Shah J., Kaufman R.J. Differential interaction of coagulation factor VIII and factor V with protein chaperones calnexin and calreticulin. J Biol Chem. 1998 doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang K., Wang S., Malhotra J., Hassler J.R., Back S.H., Wang G., Chang L., Xu W., Miao H., Leonardi R., Chen Y.E., Jackowski S., Kaufman R.J. The unfolded protein response transducer IRE1α ± prevents ER stress-induced hepatic steatosis. EMBO J. 2011 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang B., Cunningham M.A., Nichols W.C., Bernat J.A., Seligsohn U., Pipe S.W., McVey J.H., Schulte-Overberg U., De Bosch N.B., Ruiz-Saez A., White G.C., Tuddenham E.G.D., Kaufman R.J., Ginsburg D. Bleeding due to disruption of a cargo-specific ER-to-Golgi transport complex. Nat Genet. 2003 doi: 10.1038/ng1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malhotra J.D., Miao H., Zhang K., Wolfson A., Pennathur S., Pipe S.W., Kaufman R.J. Antioxidants reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress and improve protein secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dasgupta D., Nakao Y., Mauer A.S., Thompson J.M., Sehrawat T.S., Liao C.-Y., Krishnan A., Lucien F., Guo Q., Liu M., Xue F., Fukushima M., Katsumi T., Bansal A., Pandey M.K., Maiers J.L., DeGrado T., Ibrahim S.H., Revzin A., Pavelko K.D., Barry M.A., Kaufman R.J., Malhi H. IRE1A stimulates hepatocyte-derived extracellular vesicles that promote inflammation in mice with steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufman R.J., Malhotra J., Pipe S.W., Miao H. Anti-oxidants improve Factor VIII folding and secretion and reduce cell toxicity and inflammation in vivo in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leyte A., Verbeet M.P., Brodniewicz-Proba T., Van Mourik J.A., Mertens K. The interaction between human blood-coagulation Factor VIII and von Willebrand factor. Characterization of a high-affinity binding site on Factor VIII. Biochem J. 1989 doi: 10.1042/bj2570679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nesheim M., Pittman D.D., Giles A.R., Fass D.N., Wang J.H., Slonosky D., Kaufman R.J. The effect of plasma von Willebrand factor on the binding of human factor VIII to thrombin-activated human platelets. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17815–17820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chavin S.I. Factor VIII: structure and function in blood clotting. Am J Hematol. 1984 doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830160312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vehar G.A., Keyt B., Eaton D., Rodriguez H., O’brien D.P., Rotblat F., Oppermann H., Keck R., Wood W.I., Harkins R.N., Tuddenham E.G.D., Lawn R.M., Capon D.J. Structure of human factor VIII. Nature. 1984 doi: 10.1038/312337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fay P.J. Factor VIII structure and function. Int J Hematol. 2006 doi: 10.1532/IJH97.05113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Federici A.B. The factor VIII/von Willebrand factor complex: basic and clinical issues. Haematologica. 2003;88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lollar P., Knutson G.J., Fass D.N. Activation of porcine Factor VIII:C by thrombin and Factor Xa. Biochemistry. 1985 doi: 10.1021/bi00348a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hockin M.F., Jones K.C., Everse S.J., Mann K.G. A model for the stoichiometric regulation of blood coagulation. J Biol Chem. 2002 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lenting P.J., Van Mourik J.A., Mertens K. The life cycle of coagulation factor VIII in view of its structure and function. Blood. 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mazurkiewicz-Pisarek A., Płucienniczak G., Ciach T., Plucienniczak A. The factor VIII protein and its function. Acta Biochim Pol. 2016 doi: 10.18388/abp.2015_1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bovenschen N., Van Dijk K.W., Havekes L.M., Mertens K., Van Vlijmen B.J.M. Clearance of coagulation factor VIII in very low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice. Br J Haematol. 2004 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saenko E.L., Yakhyaev A.V., Mikhailenko I., Strickland D.K., Sarafanov A.G. Role of the low density lipoprotein-related protein receptor in mediation of factor VIII catabolism. J Biol Chem. 1999 doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Schooten C.J., Shahbazi S., Groot E., Oortwijn B.D., Van Den Berg H.M., Denis C.V., Lenting P.J. Macrophages contribute to the cellular uptake of Von Willebrand factor and factor VIII in vivo. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swystun L.L., Notley C., Georgescu I., Lai J.D., Nesbitt K., James P.D., Lillicrap D. The endothelial lectin clearance receptor CLEC4M binds and internalizes factor VIII in a VWF-dependent and independent manner. J Thromb Haemost. 2019 doi: 10.1111/jth.14404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swystun L.L., Notley C., Georgescu I., James P.D., Lillicrap D. The endothelial lectin receptor CLEC4M internalizes Factor VIII and Von Willebrand factor via a clathrin-coated pit-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swystun LL, Notley C, Sponagle K, James PD, Lillicrap D. The endothelial lectin CLEC4M is a novel clearance receptor for factor VIII (ISTH Congr Abstr). J Thromb Haemost. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Rydz N., Swystun L.L., Notley C., Paterson A.D., Riches J.J., Sponagle K., Boonyawat B., Montgomery R.R., James P.D., Lillicrap D. The C-type lectin receptor CLEC4M binds, internalizes, and clears von Willebrand factor and contributes to the variation in plasma von Willebrand factor levels. Blood. 2013 doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-457507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith N.L., Chen M.H., Dehghan A., Strachan D.P., Basu S., Soranzo N., Hayward C., Rudan I., Sabater-Lleal M., Bis J.C., De Maat M.P.M., Rumley A., Kong X., Yang Q., Williams F.M.K., Vitart V., Campbell H., Mälarstig A., Wiggins K.L., Van Duijn C.M., McArdle W.L., Pankow J.S., Johnson A.D., Silveira A., McKnight B., Uitterlinden A.G., Aleksic N., Meigs J.B., Peters A., Koenig W., Cushman M., Kathiresan S., Rotter J.I., Bovill E.G., Hofman A., Boerwinkle E., Tofler G.H., Peden J.F., Psaty B.M., Leebeek F., Folsom A.R., Larson M.G., Spector T.D., Wright A.F., Wilson J.F., Hamsten A., Lumley T., Witteman J.C.M., Tang W., O’Donnell C.J. Novel associations of multiple genetic loci with plasma levels of factor VII, factor VIII, and von Willebrand factor: the charge (cohorts for heart and aging research in genome epidemiology) consortium. Circulation. 2010 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.869156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swystun L.L., Lai J.D., Notley C., Georgescu I., Paine A.S., Mewburn J., Nesbitt K., Schledzewski K., Géraud C., Kzhyshkowska J., Goerdt S., Hopman W., Montgomery R.R., James P.D., Lillicrap D. The endothelial cell receptor stabilin-2 regulates VWF-FVIII complex half-life and immunogenicity. J Clin Invest. 2018 doi: 10.1172/JCI96400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pegon J.N., Kurdi M., Casari C., Odouard S., Denis C.V., Christophe O.D., Lenting P.J. Factor VIII and von Willebrand factor are ligands for the carbohydrate-receptor Siglec-5. Haematologica. 2012 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.063297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wohner N., Muczynski V., Mohamadi A., Legendre P., Proulle V., Aymé G., Christophe O.D., Lenting P.J., Denis C.V., Casari C. Macrophage scavenger receptor sr-ai contributes to the clearance of von Willebrand factor. Haematologica. 2018 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.175216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pinzani M., Rosselli M., Zuckermann M. Liver cirrhosis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martinelli I., Primignani M., Aghemo A., Reati R., Bucciarelli P., Fabris F., Battaglioli T., Dell’Era A., Mannucci P.M. High levels of factor VIII and risk of extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction. J Hepatol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Praktiknjo M., Trebicka J., Carnevale R., Pastori D., Queck A., Ettorre E., Violi F. Von Willebrand and Factor VIII portosystemic circulation gradient in cirrhosis: implications for portal vein thrombosis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020 doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beattie W., Magnusson M., Hardikar W., Monagle P., Ignjatovic V. Characterization of the coagulation profile in children with liver disease and extrahepatic portal vein obstruction or shunt. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.1080/08880018.2017.1313919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McConnell M., Iwakiri Y. Biology of portal hypertension. Hepatol Int. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9826-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kalambokis G.N., Oikonomou A., Christou L., Kolaitis N.I., Tsianos E.V., Christodoulou D., Baltayiannis G. von Willebrand factor and procoagulant imbalance predict outcome in patients with cirrhosis and thrombocytopenia. J Hepatol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iwakiri Y. Pathophysiology of portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yokoyama Y., Wawrzyniak A., Sarmadi A.M., Baveja R., Gruber H.E., Clemens M.G., Zhang J.X. Hepatic arterial flow becomes the primary supply of sinusoids following partial portal vein ligation in rats. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Almeida C.B., Souza L.E.B., Leonardo F.C., Costa F.T.M., Werneck C.C., Covas D.T., Costa F.F., Conran N. Acute hemolytic vascular inflammatory processes are prevented by nitric oxide replacement or a single dose of hydroxyurea. Blood. 2015;126:711–720. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-616250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiest R., Das S., Cadelina G., Garcia-Tsao G., Milstien S., Groszmann R.J. Bacterial translocation in cirrhotic rats stimulates eNOS-derived NO production and impairs mesenteric vascular contractility. J Clin Invest. 1999 doi: 10.1172/JCI7458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wiest R., Lawson M., Geuking M. Pathological bacterial translocation in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2014;60:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jilma B., Pernerstorfer T., Dirnberger E., Stohlawetz P., Schmetterer L., Singer E.A., Grasseli U., Eichler H.G., Kapiotis S. Effects of histamine and nitric oxide synthase inhibition on plasma levels of von Willebrand factor antigen. J Lab Clin Med. 1998 doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(98)90157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jilma B., Dirnberger E., Eichler H.G., Matulla B., Schmetterer L., Kapiotis S., Speiser W., Wagner O.F. Partial blockade of nitric oxide synthase blunts the exercise-induced increase of von Willebrand factor antigen and of factor VIII in man. Thromb Haemost. 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsochatzis E.A., Bosch J., Burroughs A.K. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bertaglia E., Belmonte P., Vertolli U., Azzurro M., Martines D. Bleeding in cirrhotic patients: a precipitating factor due to intravascular coagulation or to hepatic failure? Haemostasis. 1983;13:328–334. doi: 10.1159/000214772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sinegre T., Duron C., Lecompte T., Pereira B., Massoulier S., Lamblin G., Abergel A., Lebreton A. Increased factor VIII plays a significant role in plasma hypercoagulability phenotype of patients with cirrhosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 doi: 10.1111/jth.14011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fimognari F.L., De Santis A., Piccheri C., Moscatelli R., Gigliotti F., Vestri A., Attili A., Violi F. Evaluation of D-dimer and factor VIII in cirrhotic patients with asymptomatic portal venous thrombosis. J Lab Clin Med. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Valla D.C., Rautou P.E. The coagulation system in patients with end-stage liver disease. Liver Int. 2015 doi: 10.1111/liv.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baele G., Matthijs E., Barbier F. Antihaemophilic factor A activity, F VIII related antigen and Von Willebrand factor in hepatic cirrhosis. Acta Haematol. 1977 doi: 10.1159/000207893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Höfeier H., Klingemann H.G. Fibronectin and Factor VIII-related antigen in liver cirrhosis and acute liver failure. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1984 doi: 10.1515/cclm.1984.22.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Madeira C.L., Layman R.E., De Vera M.E., Fontes P.A., Ragni M.V. Extrahepatic factor VIII production in transplant recipient of hemophilia donor liver. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zanolini D., Merlin S., Feola M., Ranaldo G., Amoruso A., Gaidano G., Zaffaroni M., Ferrero A., Brunelleschi S., Valente G., Gupta S., Prat M., Follenzi A. Extrahepatic sources of factor VIII potentially contribute to the coagulation cascade correcting the bleeding phenotype of mice with hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2015 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.123117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shi Q., Fahs S.A., Kuether E.L., Cooley B.C., Weiler H., Montgomery R.R. Targeting FVIII expression to endothelial cells regenerates a releasable pool of FVIII and restores hemostasis in a mouse model of hemophilia A. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-272419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Poothong J., Pottekat A., Siirin M., Campos A.R., Paton A.W., Paton J.C., Lagunas-Acosta J., Chen Z., Swift M., Volkmann N., Hanein D., Yong J., Kaufman R.J. Factor VIII exhibits chaperone-dependent and glucose-regulated reversible amyloid formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Blood. 2020 doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tripodi A., Primignani M., Lemma L., Chantarangkul V., Mannucci P.M. Evidence that low protein C contributes to the procoagulant imbalance in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carnevale R., Raparelli V., Nocella C., Bartimoccia S., Novo M., Severino A., De Falco E., Cammisotto V., Pasquale C., Crescioli C., Scavalli A.S., Riggio O., Basili S., Violi F. Gut-derived endotoxin stimulates factor VIII secretion from endothelial cells. Implications for hypercoagulability in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Holestelle M.J., Geertzen H.G.M., Straatsburg I.H., van Gulik T.M., van Mourik J.A. Factor VIII expression in liver disease. Thromb Haemost. 2004 doi: 10.1160/TH03-05-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tatsumi K., Ohashi K., Taminishi S., Sakurai Y., Ogiwara K., Yoshioka A., Okano T., Shima M. Regulation of coagulation factors during liver regeneration in mice: mechanism of factor VIII elevation in plasma. Thromb Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shin E.C., Han J.W., Kang W., Kato T., Kim S.J., Zhong J., Kim S., Park S.H., Sung P.S., Watashi K., Park J.Y., Windisch M.P., Oh J.W., Wakita T., Han K.H., Jang S.K. 2020. The beginning of ending hepatitis C virus: a summary of the 26th International Symposium on Hepatitis C Virus and Related Viruses Viruses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Webster D.P., Klenerman P., Dusheiko G.M. Hepatitis C. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62401-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schreiber Z.A., Bräu N. Acquired factor VIII inhibitor in patients with hepatitis C virus infection and the role of interferon-α: a case report. Am J Hematol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/ajh.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhubi B., Mekaj Y., Baruti Z., Bunjaku I., Belegu M. Transfusion-transmitted infections in haemophilia patients. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2009 doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2009.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Papadopoulos N., Argiana V., Deutsch M. Hepatitis C infection in patients with hereditary bleeding disorders: epidemiology, natural history, and management. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018 doi: 10.20524/aog.2017.0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ragni M.V., Belle S.H., Im K.A., Neff G., Roland M., Stock P., Heaton N., Humar A., Fung J.F. Survival of human immunodeficiency virus-infected liver transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 2003 doi: 10.1086/379254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zeichner S.B., Harris A., Turner G., Francavilla M., Lutzky J. An acquired Factor VIII inhibitor in a patient with HIV and HCV: a case presentation and literature review. Case Rep Hematol. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/628513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mori T., Okanoue T., Sawa Y., Hori N., Ohta M., Kagawa K. Defenestration of the sinusoidal endothelial cell in a rat model of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ragni M.V., Moore C.G., Soadwa K., Nalesnik M.A., Zajko A.B., Cortese-Hassett A., Whiteside T.L., Hart S., Zeevi A., Li J., Shaikh O.S. Impact of HIV on liver fibrosis in men with hepatitis C infection and haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vorrink S., Zhou Y., Ingelman-Sundberg M., Lauschke V.M. Prediction of drug-induced hepatotoxicity using long-term stable primary hepatic 3D spheroid cultures in chemically defined conditions. Toxicol Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Famularo G., De Maria S., Minisola G., Nicotra G.C. Severe acquired hemophilia with factor VIII inhibition associated with acetaminophen and chlorpheniramine. Ann Pharmacother. 2004 doi: 10.1345/aph.1E100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Doering C.B., Parker E.T., Nichols C.E., Lollar P. Decreased factor VIII levels during acetaminophen-induced murine fulminant hepatic failure. Blood. 2003 doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee K.C.L., Baker L., Mallett S., Riddell A., Chowdary P., Alibhai H., Chang Y.M., Priestnall S., Stanzani G., Davies N., Mookerjee R., Jalan R., Agarwal B. Hypercoagulability progresses to hypocoagulability during evolution of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury in pigs. Sci Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09508-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Urashima S., Tsutsumi M., Nakase K., Wang J.-S., Takada A. Studies on capillarization of the hepatic sinusoids in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol. 1993 doi: 10.1093/alcalc/28.supplement_1b.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ragni M.V., Lewis J.H., Spero J.A., Hasiba U. Bleeding and coagulation abnormalities in alcoholic cirrhotic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1982 doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1982.tb04973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Beier J.I., Arteel G.E. Alcoholic liver disease and the potential role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and fibrin metabolism. Exp Biol Med. 2012 doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Loomba R., Sanyal A.J. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tripodi A., Fracanzani A.L., Primignani M., Chantarangkul V., Clerici M., Mannucci P.M., Peyvandi F., Bertelli C., Valenti L., Fargion S. Procoagulant imbalance in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lisman T., Leebeek F.W.G. Hemostatic alterations in liver disease: a review on pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and treatment. Dig Surg. 2007 doi: 10.1159/000103655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stravitz R.T., Lisman T., Luketic V.A., Sterling R.K., Puri P., Fuchs M., Ibrahim A., Lee W.M., Sanyal A.J. Minimal effects of acute liver injury/acute liver failure on hemostasis as assessed by thromboelastography. J Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Agarwal B., Wright G., Gatt A., Riddell A., Vemala V., Mallett S., Chowdary P., Davenport A., Jalan R., Burroughs A. Evaluation of coagulation abnormalities in acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Alonso-Madrigal C., Dobón-Rebollo M., Laredo-de-la-Torre V., Palomera-Bernal L., García-Gil F.A. Liver transplantation in hemophilia A and von Willebrand disease type 3: perioperative management and post-transplant outcome. Rev Esp Enfermedades Dig. 2018 doi: 10.17235/reed.2018.5204/2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bedreli S., Straub K., Achterfeld A., Willuweit K., Katsounas A., Saner F., Wedemeyer H., Herzer K. The effect of immunosuppression on coagulation after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2019 doi: 10.1002/lt.25476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yokoyama S., Bartlett A., Dar F.S., Heneghan M., O’Grady J., Rela M., Heaton N. HPB; Oxford: 2011. Outcome of liver transplantation for haemophilia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Werner M.J.M., de Meijer V.E., Adelmeijer J., de Kleine R.H.J., Scheenstra R., Bontemps S.T.H., Reyntjens K.M.E.M., Hulscher J.B.F., Lisman T., Porte R.J. Evidence for a rebalanced hemostatic system in pediatric liver transplantation: a prospective cohort study. Am J Transplant. 2019 doi: 10.1111/ajt.15748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ragni M.V., Devera M.E., Roland M.E., Wong M., Stosor V., Sherman K.E., Hardy D., Blumberg E., Fung J., Barin B., Stablein D., Stock P.G. Liver transplant outcomes in HIV(+) haemophilic men. Haemophilia. 2013 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Darby S.C., Sau W.K., Spooner R.J., Giangrande P.L.F., Hill F.G.H., Hay C.R.M., Lee C.A., Ludlam C.A., Williams M. Mortality rates, life expectancy, and causes of death in people with hemophilia A or B in the United Kingdom who were not infected with HIV. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Plug I., Van Der Bom J.G., Peters M., Mauser-Bunschoten E.P., De Goede-Bolder A., Heijnen L., Smit C., Willemse J., Rosendaal F.R. Mortality and causes of death in patients with hemophilia, 1992-2001: a prospective cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Philipp C. The aging patient with hemophilia: complications, comorbidities, and management issues. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010 doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mishra A., Arindkar S., Sahay P., Kumar J.M., Upadhyay P.K., Majumdar S.S., Nagarajan P. Evaluation of high-fat high-fructose diet treatment in factor VIII (coagulation factor)-deficient mouse model. Int J Exp Pathol. 2018 doi: 10.1111/iep.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lisman T., Bongers T.N., Adelmeijer J., Janssen H.L.A., De Maat M.P.M., De Groot P.G., Leebeek F.W.G. Elevated levels of von Willebrand factor in cirrhosis support platelet adhesion despite reduced functional capacity. Hepatology. 2006 doi: 10.1002/hep.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ragni M.V., Bontempo F.A. Increase in hepatitis C virus load in hemophiliacs during treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 1999 doi: 10.1086/315143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Eyster M.E., Kong L., Li M., Schreibman I.R. Long term survival in persons with hemophilia and chronic hepatitis C: 40 year outcomes of a large single center cohort. Am J Hematol. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ajh.24427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]