Abstract

Although approved as an alcohol-abuse drug, disulfiram (DSF) exhibited potential anticancer activity when chelated with copper (Cu). However, the low level of intrinsic Cu, toxicity originated from exogenous Cu supplementation, and poor stability of DSF in vivo severely limited its application in cancer treatment. Herein, we proposed an in situ DSF antitumor efficacy triggered system, taking advantages of Cu-based metal-organic framework (MOF). In detail, DSF was encapsulated into Cu-MOF nanoparticles (NPs) during its formation, and the obtained NPs were coated with hyaluronic acid to enhance the tumor targetability and biocompatibility. Notably, DSF loaded Cu-MOF NPs maintained stability and integrity without Cu2+ leakage in blood circulation, thus showing excellent biosafety. Once accumulating at tumor site, NPs were internalized into tumor cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis and released DSF and Cu2+ simultaneously in the hyaluronidase-enriched and acidic intracellular tumor microenvironment. This profile lead to in situ chelation reaction between DSF and Cu2+, generating toxic DSF/Cu complex against tumor cells. Both in vitro and in vivo results demonstrated the programmed degradation and recombination property of Cu-based MOF NPs, which facilitated the tumor-specific chemotherapeutic effects of DSF. This system provided a promising strategy for the application of DSF in tumor therapy.

KEY WORDS: Disulfiram, Copper, Metal-organic framework, Hyaluronic acid, Lysosomal escape, DSF/Cu complex, In situ, Antitumor therapy

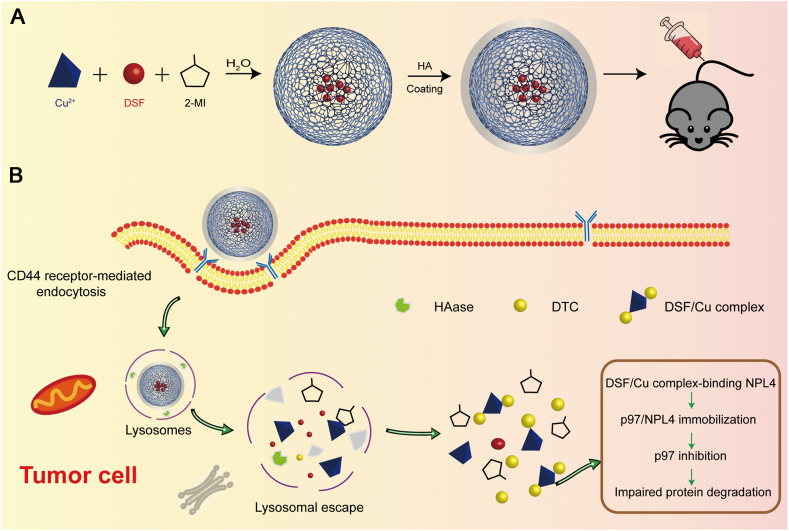

Graphical abstract

Hyaluronic acid-modified Cu-MOF nanoparticles are internalized by tumor cells, and decomposed under hyaluronidase and low pH conditions in the lysosome. DSF/Cu complex is generated in situ, enhancing the antitumor efficacy.

1. Introduction

Despite increasing advances in cancer treatment, development of ideal chemotherapeutic strategies with improved efficacy and reduced toxicity remains challenging. In recent years, investigation on repurposing drugs, such as aspirin and metformin1, 2, 3, 4, has demonstrated promising potential in antitumor research. Among them, disulfiram (DSF), an alcohol-abuse drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)5,6, exhibits effective antitumor potency in a copper-dependent manner7, 8, 9, 10. In detail, the dithiocarbamate (DTC) moieties of DSF chelates bivalent metals, especially copper ions (Cu2+), to form DSF/Cu complex11,12. It has been reported that this complex can strongly bind nuclear protein localization 4 (NPL4) and induce its aggregation6. Therefore, the p97-NPL4-ubiquitin fusion degradation protein 1 (UFD1) pathway is severely damaged, leading to erroneous proteins accumulation within tumor cells and cell death11,13.

Considering the anticancer activity of DSF is significantly relied on the concentration of Cu2+, and the endogenous biodistribution of Cu2+ is anfractuous, Cu2+ supplementation can be used for maximizing the effect of DSF. However, this systemic Cu administration may induce Cu content imbalance, and result in heavy metal poisoning for cancer patients without a copper deficiency. Furthermore, the low water solubility, poor stability, as well as the rapid metabolism, of DSF hinder its application in vivo13,14. Accordingly, co-delivery and simultaneous release of DSF together with Cu at tumor site to generate DSF/Cu complex in situ is a potential strategy to improve the chemotherapeutic efficacy.

Recently, nanotechnology-based DSF or DSF/Cu delivery systems have been explored and achieved potential therapeutic efficacy6,15. Nevertheless, DSF and Cu2+ entrapped in different formulations or administered through DSF/Cu complex ex situ may be not quite convenient for therapy. Nano-sized metal-organic frameworks (MOF), which are composed of metal ions and organic ligands16,17, attracted our great interest. Until now, Zn, Fe and Mg-based MOFs with excellent biocompatibility, drug loading capacity and controllable surface functionality have been utilized as a potential carrier for drug delivery10,18, 19, 20, 21. These drug-loaded MOF are usually synthesized by the "one-pot method”, which is simple and time-saving6. More importantly, they can maintain stable under neutral conditions, but disintegrate in the acidic tumor microenvironment, leading to selectively drug release at target site10,22, 23, 24, 25. Consequently, it is desirable to take advantages of Cu-based MOF to encapsulate DSF for cancer chemotherapy, which can deliver both Cu2+ and DSF into tumor, and thus trigger in situ toxicity against tumor cells. It should be mentioned that MOF are often synthesized in alkaline conditions or organic solvents, and thus drugs that are unstable or insoluble under these conditions are not suitable to be incorporated by MOF. Fortunately, the property of DSF provided it the adaptivity of using Cu-MOF delivery strategy.

Furthermore, the systemic half-life time, chemical stability, safety consideration and targeting biodistribution of MOF system should be also considered24. As a natural polysaccharide, hyaluronic acid (HA) has been widely used for modifying nanocarriers to improve the water solubility, biocompatibility, and tumor targetability26, 27, 28. In particular, HA exhibited strong affinity with CD44 receptor that is overexpressed on surface of various tumor cells, making it a potential molecule for application in a cancer targeting therapy29. Thus, HA-modified Cu-MOF might be a good candidate for enhanced DSF-based antitumor therapy.

In this investigation, we designed multileveled in situ triggered DSF-loaded HA-modified Cu-MOF nanoparticles (DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs), constructed from Cu ion and 2-methyl imidazole (2-MI). DSF was encapsulated under mild conditions during the MOF forming process, and HA decoration was achieved via electrostatic interaction (Scheme 1A). DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs with active tumor targeting ability remained stable and prolonged circulation in blood. Once arriving at tumor site, they would be internalized by tumor cells through CD44 receptor-mediated endocytosis, and decomposed under hyaluronidase (HAase) and low pH conditions in the lysosome. As a result, DSF and Cu2+ were simultaneously released in the intracellular tumor microenvironment and generated toxic DSF/Cu complex, which bond NPL4 target in the p97 pathway in the tumor cells, thus eventually inducing cell death (Scheme 1B). In summary, this system possessed Cu2+ self-supplying property, reduced systemic toxicity and enhanced DSF-based antitumor efficacy.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of (A) the preparation of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF and (B) generation of DSF/Cu complex in situ in tumor cell for antitumor therapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Copper chloride dihydrate (CuCl2·2H2O) was purchased from Guangfu Technology Development Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). 2-MI and sodium diethydithiocarbamate trihydrate were purchased from the Aladdin Reagent Co. (Shanghai, China). DSF was obtained from Adamas-Beta Co. (Shanghai, China). HA (molecular weight: 8 kDa) was ordered from Bloomage Freda Biopharm Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China). N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) was purchased from Zhiyuan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Chloroform was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Acetonitrile was purchased from Tianjin Siyou Fine Chemical Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Simulated body fluid (SBF) and copper detection kit were purchased from Leagene Biotech. Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Sulforhodamine B (SRB) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (USA). Lysosomal red fluorescent probe was obtained from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). Live and dead viability/cytotoxicity assay kit was obtained from Yeasen Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Cell lines and animals

The murine mammary 4T1 cancer cells and human normal stem cells (L02 cell line) were supported by Key Laboratory of Targeting Therapy and Diagnosis for Critical Diseases in Henan Province. 4T1 cells were cultured in 1640 medium (Solarbio, Beijing, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and penicillin (100 U/mL) at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The L02 cells were cultured in the Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) medium (Solarbio, Beijing, China) supplemented with similar supplements and cultured as above methods.

Female BALB/c mice (18–22 g, No. DW201910075) and female SD rats (180–200 g, No. 410975200100016238) were obtained from Henan Province Experimental Animal Center (Henan, China). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines, and with the approval, of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China.

2.3. Synthesis of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs

Initially, CuCl2·2H2O (0.5 mmol) was dissolved in 6.3 mL of H2O (pH 9, adjusted by NaOH). After that, 60 μL of chloroform including 0.25 mmol of DSF was put into the CuCl2 solution with stirring. Then, 10 mL of H2O (pH 9) containing 15 mmol of 2-MI was added dropwise to the mixed solution of above. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. Unreacted disulfiram was removed by centrifugal washing at least three times (12,000 rpm 15 min, TGL-16G, Shanghai Anting Scientific Instrument Factory, Shanghai, China) with DMF, and the precipitate was placed in an oven and dried at 60 °C to obtain DSF@Cu-MOF NPs. Subsequently, an appropriate amount of dried DSF@Cu-MOF NPs was dispersed in a certain amount of H2O (pH 9) by an ultrasonic cell pulverizer. HA was added into the above solution at a mass ratio of 1:2 (DSF@Cu-MOF: HA) under stirring. The mixed solution was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After that, the resultant solution was dialyzed by using a dialysis bag with a cut-off molecular weight of 60 kDa for 12 h to remove excess HA. Finally, the dialyzed solution was lyophilized to obtain DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs.

2.4. Characterization

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were obtained with a Q400 scanning electron microscope (FEI, USA). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained with a Tecnai G2 F20 S-TWIN TMP field emission transmission electron microscope (FEI, USA). Energy-dispersive spectra (EDS) was carried out by using a GENESIS energy disperse spectroscopy (EDAX, USA). The particle sizes and zeta potentials were characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Zetasizer Nano ZS-90, Malvern, UK). Fourier transform infrared resonance (FT-IR) spectra were obtained on Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was performed on the AXIS Supra X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were recorded on X'Pert-Pro MPD X-ray powder diffractometer (Panalytical, Holland).

2.5. In vitro degradation evaluation

To investigate the disintegration property of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs and combination profile of DSF with Cu in tumor cells, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs were dissolved in an appropriate amount of ultrapure water (pH 5.6) and then added HAase (Sigma–Aldrich, USA) at a concentration of 150 U/mL. The mixed solution was shaken at 37 °C and 100 rpm/min, and 2 mL of the mixed solution was taken at different times (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h) for particle size and zeta potential measurement. Among them, appropriate samples taken at 2 and 4 h were also used for TEM. In order to investigate that DSF can combine with Cu2+ to generate DSF/Cu complex at the tumor site, HA/Cu-MOF NPs and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs were respectively placed in SBF solutions (2 mg/mL, 8 mL) with shaking at 37 °C and 100 rpm. After 24 h, the mixed liquid was removed and centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 15 min, Shanghai Anting Scientific Instrument Factory). The precipitate was dissolved in absolute ethanol and analyzed by an ultra-violet-visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometer (UV-2550 Shimadzu).

2.6. Serum stability evaluation

In order to examine the serum stability, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs were dispersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and shaken at 100 rpm (37 °C). 2 mL of sample was taken out at different time points (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h) for particle size measurement. At the same time, the UV–Vis spectrophotometer was utilized to test the absorbance in order to determine whether DSF/Cu complex was generated.

2.7. In vitro drug release

In vitro release profiles of Cu2+, DSF and DSF/Cu complex from different formulations were studied using a dialysis method under conditions mimicking tumor microenvironment. Briefly, 1 mL of NPs dispersions were transferred into the dialysis bags (MWCO = 14 kDa), which were immersed in 20.0 mL of release medium (pH 5.6、pH 5.6 + HAase and pH 7.4) containing Tween 80 (0.5%, w/w) at 37 °C with constant shaking at 100 rpm. At predetermined time intervals (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h), 2 mL of sample was taken out for testing and replaced with 2 mL fresh medium. The amount of DSF and DSF/Cu complex was determined by HPLC (Waters e2695, Waters) at the wavelength of 218 and 423 nm, respectively. Cu2+ content was measured using UV spectrometry at an excitation wavelength of 433 nm by complexation with sodium diethydithiocarbamate trihydrate.

2.8. Cytotoxicity assays

The cytotoxicity of free CuCl2, free DSF, DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF NPs, and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs against 4T1 cells was measured by SRB assay. In brief, 4T1 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 8 × 103 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were incubated with series concentrations of free CuCl2, free DSF, DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF NPs, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs. Among them, the concentration of CuCl2 was designed according to DSF concentration at mole ratio of 1:1. In addition, the DSF concentration used in this experiment was set at 0.2, 1.0, 2.5, 5, 10 μmol/L. The corresponding concentration of HA/Cu-MOF in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF was 0.12, 0.6, 1.5, 3, 6 μg/mL. Cells treated with blank medium served as a control group. After incubation for 24 and 48 h, the cells were washed three times with PBS and the cell viability was analyzed with the SRB assay. The absorbance was measured on a microplate reader at λ = 515 nm.

For live and dead cell observations on a fluorescence microscope, 4T1 cells were seeded onto a 24-well plate at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well. After culture for 24 h, cells were incubated with free CuCl2, free DSF, DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF NPs, and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs. Herein, DSF and CuCl2 concentration used was 10 μmol/L. Cells treated with blank medium served as a control group. After incubation for 6 h, the cells were rinsed three times with PBS and co-stained with calcein-acetoxymethyl (AM) and propidium iodide (PI) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols. After 15 min of incubation, the cells were rinsed three times with PBS and taken photographs using fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510).

2.9. Cellular uptake

To investigate the cellular uptake of NPs, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC, Sigma–Aldrich, USA) was used as an imaging probe for the detections. The preparation method of FITC@Cu-MOF and FITC@HA/Cu-MOF is similar to the synthesis method of DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF. The detail methods were provided in Supporting Information. 4T1 cells were seeded into 24-well plates at 3 × 104 cells per well and cultured for 24 h. Then, the medium was discarded, and free FITC, FITC@Cu-MOF NPs, and FITC@HA/Cu-MOF NPs with an equivalent dose of 30 μg/mL FITC were added. Meanwhile, HA pretreated (HA: 5 mg/mL, 2 h) cells which were incubated with FITC@HA/Cu-MOF NPs were used as the control. At predetermined time points (0.5, 2, 4 and 6 h), the sample-containing medium was removed and washed several times with PBS. Subsequently, the cell lysosome and nucleus were labeled with the lysosomal red fluorescent probe (Beyotime, China) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) dye (Solarbio, Beijing, China) with 1 μg/mL, respectively. After staining, the excess dye was removed by washing several times with PBS. Cellular uptake was observed under the confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM, Leica TCS SP8, Germany).

For flow cytometry analysis, 4T1 cells were cultured into 12-well plates at 6 × 104 cells per well for cultured 24 h. Cells were treated with different samples as mention above. At predetermined time (0.5, 2, 4 and 6 h), samples were removed and washed several times with PBS. After that, the cells were collected for flow cytometry quantitative analysis (FACSAria Ⅲ, BD).

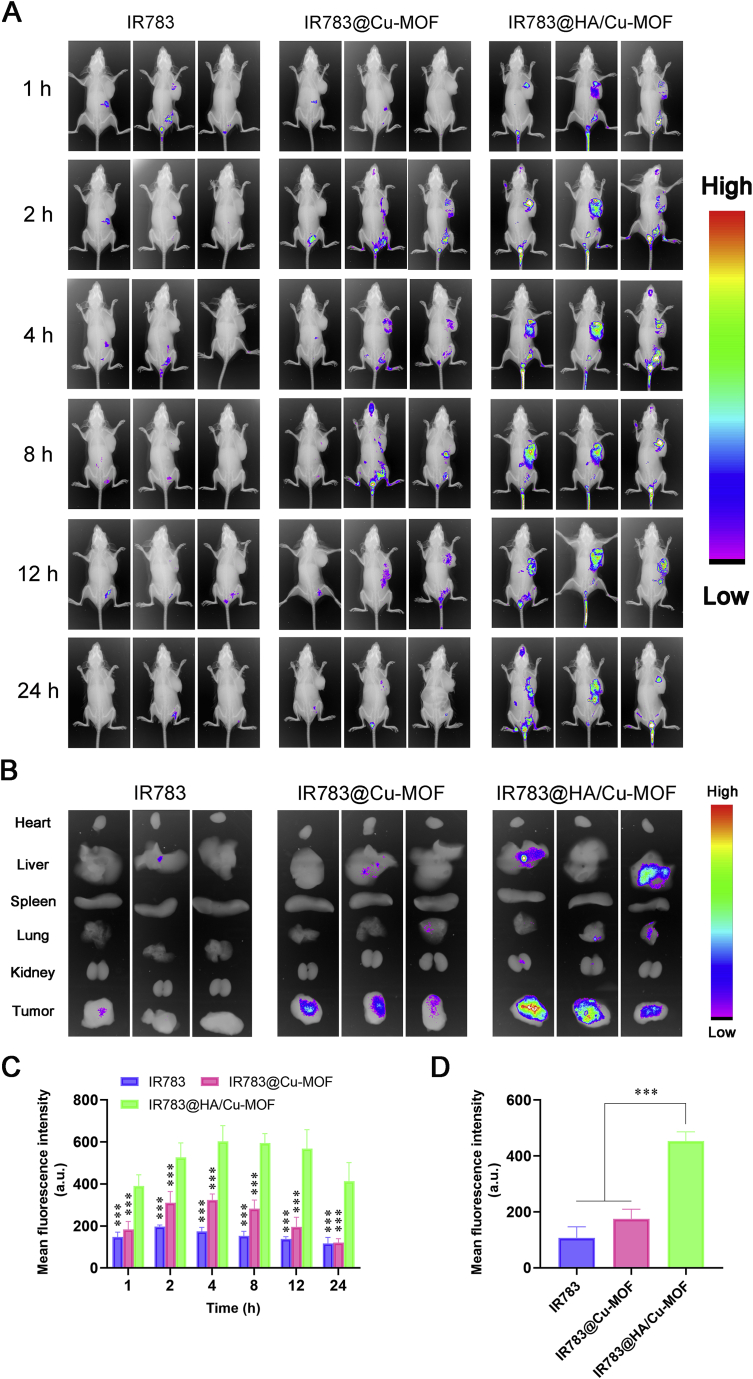

2.10. In vivo targetability evaluation

To investigate the targetability of NPs in vivo, IR783 (Sigma–Aldrich, USA) was used as an imaging probe for the detections. The detail preparation methods of IR783@Cu-MOF and IR783@HA/Cu-MOF were provided in Supporting Information. 4T1 (2 × 106) cells suspended in 200 μL of PBS were implanted subcutaneously into the lower part of the right upper limb of BALB/c mice. When the tumor volume reached around 200 mm3, mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 3) and treated with free IR783, IR783@Cu-MOF NPs, and IR783@HA/Cu-MOF NPs via tail intravenous administration (IR783, 0.5 mg/kg). The dosage of HA/Cu-MOF in IR783@HA/Cu-MOF used in this targeting experiment in vivo was 1.10 mg/kg. At designated time points (1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h) following injection, mice were anesthetized with 0.5% pentobarbital and imaged by in vivo imaging system FX PRO with a 720 nm excitation filter and an 830 nm long-pass emission filter (Kodak, USA). At 24 h, all mice were euthanized, and main organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) and tumors were collected for ex vivo fluorescence imaging.

2.11. In situ DSF/Cu complex formation

4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice model were established as above method in Section 2.10. When tumor volume reached around 200 mm3, mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 3). DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs (DSF: 3.75 mg/kg) were injected into mice via intravenous administration. Mice were sacrificed and tumors were harvested at 1, 4, 12, 24 and 36 h post-injection. The tumor tissue samples were homogenized after adding 1 mL of normal saline. Chloroform was used to extract DSF/Cu complex and evaporated to dryness under nitrogen at 30 °C. The residue was redissolved with mobile phase (H2O: acetonitrile = 20:80, v/v) and detected by HPLC at the wavelength of 423 nm after centrifugation.

2.12. Pharmacokinetics analysis

Pharmacokinetics for different formulations was evaluated by determining serum concentration of Cu2+, DSF and DSF/Cu complex in SD rats. SD rats were randomly divided into three groups (n = 3) and injected by DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF with equal Cu2+ at a dose of 4.31 mg/kg and DSF at 10 mg/kg via the tail vein. The serum was collected at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h after injection. The concentrations of Cu2+ were measured by copper detection kit. The concentrations of DSF and DSF/Cu complex were measured by HPLC. The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by PKSolver software.

2.13. In vivo antitumor efficacy

4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice model was established as above method. When tumor volume reached around 100 mm3, mice were randomly divided into six groups (n = 5). PBS, free CuCl2, free DSF, DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs were injected into different groups of mice via the tail vein with 200 μL each time. The dose of free CuCl2 was in accordance with that in DSF/Cu complex group (CuCl2: DSF, at a mole ratio of 1:1). While the others were treated with an equivalent dose of 3.75 mg/kg DSF. The initial day of administration was defined as Day 0, and the same administration was then repeated every 2 days over a 10 days therapeutic period. At Day 14, all mice were sacrificed. The tumor volume and body weights of mice were measured every 2 days. Tumor volumes were calculated with Eq. (1):

| Tumor volume = 0.5 × Length × Width2 | (1) |

After the mice were sacrificed, tumor tissues were chosen at random and sectioned. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining were performed for histological analysis.

2.14. Safety evaluation

The major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys) were stained with H&E to evaluate toxicity. Before the mice were sacrificed, blood samples were collected through eyeballs, and then the plasma samples were collected by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min (TGL16, Xiangyi Centrifuge Instrument Co., Ltd., Changsha, China). Subsequently, the hepatorenal function was assessed by the plasma detection for alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), glutamyl transferase (GGT), creatinine (CRE), urea nitrogen (URE) and uric acid (UA).

2.15. Statistical analysis

All the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis and comparisons were performed by using one-way ANOVA on IBM SPSS Statistics 25. ∗P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Preparation and characterization of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs

Cu-MOF was synthesized via one-pot method as described before22,23,25, which could be initially confirmed through the phenomenon of color changes from transparent light blue to dark brown (Supporting Information Fig. S1A–S1I). In this process, metal ion (Cu2+) and organic linkers (2-MI) self-assembled to form coordination polymers. Meanwhile, DSF was incorporated during the formation of Cu-MOF NPs, obtaining the hierarchical DSF@Cu-MOF NPs. It should be mentioned that Cu2+ can chelate with S atom in DSF to form DSF/Cu complex. However, compared with S atom, N atom has less electronegativity and is easier to give out coordination electrons, resulting in stronger coordination ability between 2-MI and Cu2+. If S and N atoms are present in the reaction system simultaneously, Cu2+ will preferentially coordinate with N atoms instead of S atoms, thus forming Cu-MOF rather than DSF/Cu complex22. TEM and SEM images of DSF@Cu-MOF (Fig. 1A and C) showed spherical shape with diameter of ∼313 nm, which were a little smaller than the particle size determined by DLS analysis (Fig. 1E). DSF@HA/Cu-MOF displayed a uniform spherical morphology with a thin film outside (Fig. 1B and D). Furthermore, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF solution remained clear and transparent even at 12 h, while DSF@Cu-MOF was quickly precipitated (Supporting Information Fig. S2). As Cu-MOF NPs was used as Cu2+ provider for in situ generation of DSF/Cu complex, the existence of Cu should be firstly verified. The XRD patterns of Cu-MOF in the 2θ range of 10°–60° was shown in Fig. 1G, and the characteristic peaks for it appeared in 2θ = 14.6°, 29.6°, and 34.7°, which suggested of successful synthesis and highly crystalline nature of Cu-MOF NPs. From the XPS spectrum (Fig. 1H), we found a clear distribution of Cu with two strong Cu2+ satellite peaks at 960 and 940 eV, indicating that the valence state of Cu2+ does not change during its complexation with 2-MI. In order to identify the efficient encapsulation of DSF, FT-IR analysis was performed in this study. It can be seen from Fig. 1I that the characteristic peaks at 1418 and 914 cm−1 corresponding to C S and C–S groups of DSF disappeared in the FT-IR spectra of DSF@Cu-MOF NPs, while remaining in that of DSF and DSF plus Cu-MOF NPs physical mixture. In addition, the other peaks were all similar among them. These results presumably demonstrated that DSF was successfully loaded into Cu-MOF NPs, rather than physically absorbed on the surface. In the DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs spectrum, the absorption peak at 1134 cm−1 is attributed to the O=C=O glycosidic bond, which is a typical characteristic of polysaccharides. This successfully proved that HA was wrapped on the surface of DSF@Cu-MOF NPs. Considering the water solubility and biocompatibility for application in vivo, we coated HA on the surface of DSF@Cu-MOF NPs. As shown in Fig. 1E and F, all MOF NPs possessed a narrow size distribution with an average size of 310 nm, and the zeta potential of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs changed from positive charges (Cu-MOFs NPs: 17 mV, DSF@Cu-MOF NPs: 16 mV) to negative potential (−25 mV), owing to the negative charged HA modification. Moreover, EDS spectra (Fig. 1J) also clearly showed the presence of Cu, S, N elements with corresponding characteristic peaks at 672.193, 2559.290, 944.806, 8037.670, and 8899.232 eV, respectively. This fully confirmed the existence of DSF in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs.

Figure 1.

Characterization of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF. TEM images of DSF@Cu-MOF (A) and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF (B). SEM images of DSF@Cu-MOF (C) and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF (D). (E) Particle sizes of Cu-MOF, HA/Cu-MOF, DSF@Cu-MOF, and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF measured by DLS (n = 3). (F) Zeta potentials of Cu-MOF, HA/Cu-MOF, DSF@Cu-MOF, and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF measured by DLS (n = 3). (G) XRD pattern of Cu-MOF. (H) XPS spectra of Cu-MOF in different binding-energy ranges. (I) FTIR spectrum of DSF, Cu-MOF, DSF + Cu-MOF, DSF@Cu-MOF, and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF. (J) EDS spectrum of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

The formation of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs primarily depended on the stirring time, and the ratio of DSF, Cu2+ and 2-MI. The ratio of Cu2+ and 2-MI affected the size of NPs and the internal cavity. It was found that the larger the ratio of Cu2+ and 2-MI and the longer the stirring time, the easier to form the DSF/Cu-MOF and the larger its particle size was. Moreover, the more amount of DSF added, the higher drug loading of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs was. Through our continuous optimization of drug loading conditions, we finally selected the best condition of stirring for 15 min in H2O (pH 9, adjusted by NaOH) and mole ratio of 0.5:1:30 (DSF: Cu:2-MI). The drug loading and encapsulation efficiency were optimized up to 54.17% and 86.67%, respectively.

3.2. In vitro degradation evaluation of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs and formation of DSF/Cu complex

Considering DSF is an effective metal chelator and its antitumor activity is originated from the complex of DSF/Cu30, 31, 32, 33, we examined the disintegration property of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs and combination profile of DSF with Cu in tumor cells. As can be seen in Fig. 2B and C, both particle size and zeta potential of DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs increased remarkably with extending incubation time in the simulated lysosomal condition. Among them, the particle size and zeta potential of DSF@Cu-MOF NPs changed more obviously, which may be caused by lacking the protection of HA and being directly exposed to the acidic environment. Meanwhile, TEM images (Fig. 2D‒G) exhibited that the morphology of DSF@Cu-MOF NPs was changed significantly at 2 and 24 h. However, the morphology of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs was relatively intact with a little deformation at 2 h, but completely decomposed to be irregular shape at 24 h, which was consistent with the results of DLS analysis. These phenomena might be because DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs would be disassembled under the acidic environment, following the degradation of HA outer shell by HAase, and finally release DSF as well as Cu2+ (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, the resultant products as above were obtained and the generation of DSF/Cu complex was further confirmed by UV–Vis spectroscopy. It was observed in the UV–Vis spectrum (Fig. 2H) that DSF@HA/Cu-MOF degradation products presented characteristic peaks around ∼260 and ∼420 nm, which corresponded to the absorption peaks of DSF together with Cu2+ mixture, indicating of the formation of DSF/Cu complex. On the contrary, there were no absorptions at ∼260 and ∼420 nm for HA/Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF, suggesting that DSF/Cu complex did not formed in these two groups.

Figure 2.

Degradation evaluation of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF in vitro. (A) Schematic illustration of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF degradation and DSF/Cu complexation in tumor cells. (B) Particle size change of DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF in buffer containing HAase (pH 5.6) (n = 3). (C) Zeta potential change of DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF in buffer containing HAase (pH 5.6) (n = 3). TEM images of DSF@Cu-MOF (D) and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF (E) after incubation in SBF solution (pH 5.6) containing HAase for 2 h, scale bar = 500 nm. TEM images of DSF@Cu-MOF (F) and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF (G) after incubation in SBF solution (pH 5.6) containing HAase for 24 h, scale bar = 500 nm. (H) UV–Vis spectrum of DSF/Cu complex, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF, degradation product of HA/Cu-MOF and degradation product of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Given that DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs were administered by tail vein injection, the serum stability was evaluated. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S3, the particle size and zeta potential of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs changed negligibly even at 24 h and slight DSF/Cu complex was detected after incubation with PBS (pH 7.4) containing 10% FBS. It signified that DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs possessed excellent serum stability and might maintain stable in systemic circulation.

3.3. In vitro drug release

In vitro release behaviors of Cu2+, DSF and DSF/Cu complex from DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF under different conditions were shown in Supporting Information Figs. S4–S6. In the medium of pH 7.4, negligible DSF, Cu2+ and DSF/Cu complex were detected in DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF groups, suggesting Cu-MOF might maintain stable and prevent drug leakage during systemic circulation. Under pH 5.6 condition without HAase, ∼44.91% DSF/Cu complex was formed in DSF@Cu-MOF group at 4 h, whereas few DSF, Cu2+ and DSF/Cu complex were observed in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF group. On the contrary, in the pH 5.6 medium containing HAase, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs displayed increasing release of DSF and DSF/Cu complex, and the cumulative release percentage of DSF/Cu complex reached ∼85.34% at 24 h (Supporting Information Fig. S6). In addition, free DSF combined with HA/Cu-MOF NPs and HA/Cu-MOF NPs alone were used as control to determine the protection effect of HA/Cu-MOF NPs on DSF. It was found that only in medium containing HAase, Cu2+ was liberated and achieved complexation with DSF. Meanwhile, free DSF combined with HA/Cu-MOF NPs showed free DSF release profile, which was different from that in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF group. These results indicated that HA modification improved the stability of Cu-MOF and facilitated in situ DSF/Cu complexation within tumor cells.

3.4. In vitro cytotoxicity and cellular uptake of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs

After confirming the successful complexation of DSF and Cu through DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, we further determined the antitumor activity in vitro. CD44 positive 4T1 cells34, 35, 36 and CD44-negative L02 cells35 were used in this study. Firstly, we tested the formulation for possible side effects and biosafety on L02 cells and 4T1 cells. It showed a high survival rate up to ∼99% at 5 μg/mL of HA/Cu-MOF NPs after 24 h, and even maintained ∼92% at 150 μg/mL of HA/Cu-MOF NPs after 48 h (Fig. 3A and B), suggesting the superior biocompatibility and safety of our designed drug carrier. In addition, the cytotoxicity of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs against 4T1 cells was evaluated by SRB assay. As demonstrated in Fig. 3C and D, DSF and CuCl2 alone exhibited negligible toxicity to 4T1 cells, even at the corresponding concentration of 10 μmol/L of DSF. In comparison, more cells were killed after treatment with DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, DSF@Cu-MOF NPs and DSF/Cu mixture, and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs demonstrated the most excellent antitumor effect. Meanwhile, IC50 values shown in Supporting Information Table S1 were consistent with the results as above. Moreover, we tested cell viability based on calcium AM (green) and PI (red) staining of cancer cells treated with DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs. In Fig. 3E, ∼46% of 4T1 cells were survived after cotreatment with DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, as indicated by the strong green staining of live cells. For the other control groups, cell viability was influenced slightly, thus presenting green fluorescence of live cells. The result was concurrent with that of cytotoxicity analysis.

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity and cellular uptake studies of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF in vitro. (A) Cell viability of 4T1 and L02 cells after incubation with various concentrations of HA/Cu-MOF for 24 h (n = 6). (B) Cell viability of 4T1 and L02 cells after incubation with various concentrations of HA/Cu-MOF for 48 h (n = 6). (C) In vitro cytotoxicity of free DSF, DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF, and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF against 4T1 cells at different concentrations of DSF for 24 h (n = 6). (D) In vitro cytotoxicity of free DSF, DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF, and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF against 4T1 cells at different concentrations of DSF for 48 h (n = 6). (E) Fluorescence microscopy images of calcium AM (green) and PI (red) stained 4T1 cells treated under different conditions for 24 h, and the corresponding quantitative analysis of green fluorescence intensity (n = 5), scale bar = 100 μm. (F) CLSM images of 4T1 cells incubated with different formulations for 0.5, 2, 4 and 6 h. Cell nuclei was stained with DAPI (blue fluorescence). Lysosome was stained with lysosomal red fluorescence probe (red fluorescence), scale bar = 20 μm. (G) Flow cytometry analysis of 4T1 cells incubated with different agents for 0.5, 2, 4 and 6 h. (H) The average cellular green fluorescence intensity of each group in (F, n = 3). (I) The cell uptake ratio of each group in (G, n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, compared to FITC@HA/Cu-MOF.

In order to explore the reason for excellent anticancer activity of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, HA/Cu-MOF NPs was labeled with FITC to visualize its cellular uptake process. CLSM images and flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 3F‒I) demonstrate that HA/Cu-MOF NPs could be easily internalized by 4T1 cells with strong fluorescence and reached up to 89% uptake at 6 h, which was more than that for free FITC and Cu-MOF NPs group. This result is possibly owing to the vital role of HA in facilitating CD44 receptor-mediated recognition and endocytosis34,37, 38, 39, 40. Furthermore, we used HA pretreated cancer cells as the control, and found that the fluorescence intensity was inferior to that of untreated one, further indicating the targeting ability caused by the outer HA shells.

As DSF/Cu complex was formed by the released DSF and Cu2+ from DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs and produced anticancer potency in nucleus, the lysosomal escape of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs was considered very crucial. It can be seen from Fig. 3F that yellow fluorescent signals, resulting from the overlap of green fluorescence (HA/Cu-MOF NPs) and red fluorescence (lysosome), appeared after 4 h incubation, which indicated this system was endocytosed through lysosome pathway. However, this overlap decreased with time prolonged, and more green fluorescent intensity was elevated in cytoplasm compared with that in free FITC and Cu-MOF NPs groups. The above phenomenon signified that HA/Cu-MOF NPs not only promoted the internalization efficiency, but also accelerated the NPs to escape from the lysosome and exerted their tumor cell inhibition effects. The lysosomal escape property of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs is attributed to the proton sponge effect of 2-MI. After DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs enter the acid lysosome, they will decompose and release Cu2+, DSF and 2-MI. According to reports in the literature41, 42, 43, free 2-MI can capture a large number of protons and cause Cl‒ influx, leading to osmotic swelling of the lysosome. Finally, the lysosome was ruptured to release the endocytosed drugs into the cytoplasm.

3.5. In vivo targeting ability of HA/Cu-MOF NPs

The prerequisite for great anticancer efficacy is the excellent targeting ability of drug carriers. To evaluate the tumor accumulation behavior of HA/Cu-MOF NPs in vivo, non-invasive near-infrared optical imaging technology was used to monitor its biodistribution in real time. Fig. 4A displayed that free IR783 and IR783@Cu-MOF NPs were eliminated rapidly after injection, while IR783@HA/Cu-MOF NPs showed a prolonged circulation time. More importantly, enhanced fluorescent intensity at tumor site was observed in IR783@HA/Cu-MOF NPs than that in the other two groups, and the fluorescent signals still maintained strong even at 24 h, suggesting that HA modification can improve the retention time and active targetability of NPs. The corresponding semi-quantitative analysis results in Fig. 4C are consistent with the phenomenon as above. In addition, this result was further verified by the ex vivo imaging (Fig. 4B) of major organs (tumor, heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) and semi-quantitative analysis (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, we monitored the in situ formation of DSF/Cu complex at predetermined time points by measuring the intratumoral concentration of DSF/Cu using the HPLC method. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S8, intratumoral concentration of DSF/Cu complex was much higher in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF group than that in DSF/Cu complex and DSF@Cu-MOF groups. The cumulative accumulation reached maximum at 12 h post-injection, which was accordant with the phenomenon of in vivo imaging. In a word, HA/Cu-MOF NPs hold promising potentials in selectively delivering drugs into tumor tissue and facilitating DSF/Cu complexation in situ.

Figure 4.

Biodistribution and tumor targeting ability of HA/Cu-MOF. (A) In vivo fluorescence imaging of 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice at different times (1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h) after tail vein injection of free IR783, IR783@Cu-MOF and IR783@HA/Cu-MOF (Ex: 720 nm, Em: 830 nm). (B) Ex vivo fluorescence imaging of tumor tissues and major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) from 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice at 24 h post-injection. (C) Semi-quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity from the tumor site of 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice in (A, n = 3). (D) Semi-quantitative analysis of the fluorescence intensity from tumor tissue in (B, n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, compared to IR783@HA/Cu-MOF.

3.6. Pharmacokinetics evaluation of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs

In vivo pharmacokinetics study of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs was performed on SD rats (n = 3), and DSF/Cu complex as well as DSF@Cu-MOF NPs were used as control. The concentration of DSF and DSF/Cu complex in plasma were measured simultaneously. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S9 and Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3, minute DSF/Cu complex were detected in both DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF groups, indicating that Cu-based MOF NPs prevented premature formation of DSF/Cu complex in the systemic circulation. On the contrary, area under the curve (AUC) of DSF in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs reached as high as 546.15 ± 15.42 μg·h/mL, which was much higher than that in DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF/Cu complex groups. In addition, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs prolonged the mean retention time (MRT) of DSF, even compared with DSF@Cu-MOF NPs, further laying the foundation for tumor targeting except the active targeting ability of HA.

Moreover, negligible Cu2+ was detected in all groups (DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF NPs and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, Supporting Information Fig. S10). For DSF/Cu complex, it was because Cu2+ had already chelated with DSF before injection. For DSF@Cu-MOF NPs and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, it suggested that no Cu2+ leakage occurred during blood circulation and further confirmed the stability of these Cu-based MOF NPs, which was consistent with the results of serum stability and in vitro drug release study.

3.7. In vivo antitumor efficacy of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs

Inspired by the superior targetability and excellent 4T1 cells inhibition, we further evaluated the antitumor effect of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs in vivo. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into 6 groups as follows: PBS, free CuCl2, free DSF, DSF/Cu complex, DSF@Cu-MOF and DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, and injected via intravenous administration. During the treatment period, formulations were administered every other day for 6 times (Fig. 5A). Tumor volume change curve (Fig. 5B) shows that DSF or CuCl2 alone group presented almost no tumor inhibition effect as expected. DSF/Cu complex and DSF@Cu-MOF group exhibited a little better but still slight antitumor potency, due to quick clearance and non-targeting biodistribution in the body. On the contrary, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs suppressed tumor growth significantly, with a great tumor inhibition ratio of 86% after treatment, which was attributed to HA-mediated active targeting property. Moreover, mice were sacrificed at the endpoint of the experiment, and tumor tissues were harvested. From Fig. 5D and E, tumor tissues in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs group were the smallest and lightest among all groups, which was consistent with the trend of tumor volume change. Meanwhile, H&E staining and TUNEL assay for studying tumor cell apoptosis were also performed. As shown in Fig. 5F and G, highest cellular apoptosis of ∼62% and most serious malignant necrosis with intercellular blank as well as fragmentation occurred in the DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs group, although apparent cell apoptosis was observed in DSF/Cu complex and DSF@Cu-MOF group. Such superior antitumor efficacy might be owing to the programmed process as follows: (1) DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs selectively delivered both DSF and Cu ion to tumor site, retained their stability and facilitated them enter tumor cells via CD44-mediated endocytosis; (2) DSF and Cu2+ were simultaneously released from DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs responding to the overexpressed HAase and acidic intracellular tumor microenvironment26,41,44,45; (3) Toxic DSF/Cu complex was generated in situ within tumor cells, bond NPL4 and induced its aggregation, thus disrupting UFD1 pathway and effectively killing tumor cells11,46.

Figure 5.

In vivo anticancer activity of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF. (A) Schematic illustration of the administration design. (B) Tumor growth curve of 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice throughout the therapeutic experiment (n = 5). (C) Body weight curves of 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice throughout the therapeutic experiment (n = 5). (D) Pictures of the excised tumors at the endpoint of treatment. (E) Weight of the excised tumors at the endpoint of treatment (n = 5). (F) H&E and TUNEL staining of tumor sections, scale bars represent 600 and 300 μm, respectively. (G) The quantitative analysis of green fluorescence intensity in the TUNEL assay (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, compared to DSF@HA/Cu-MOF.

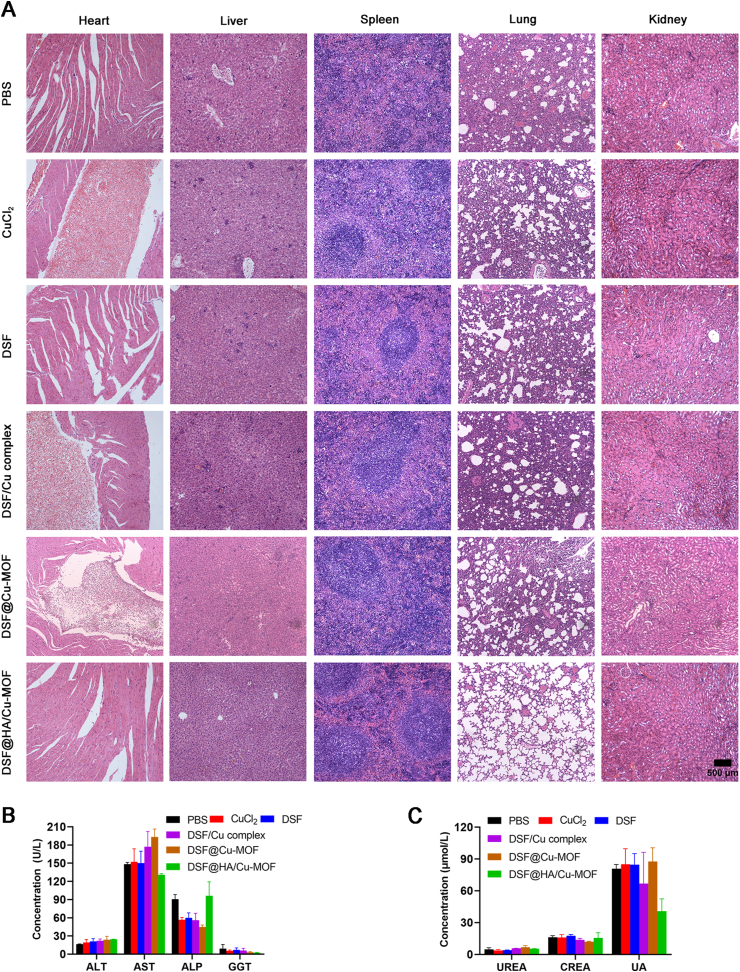

3.8. Safety evaluation of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs

Considering high levels of Cu2+ might result in heavy metal poisoning47,48 the biosafety of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs was also evaluated. As can be seen, neither noticeable body weight drop nor abnormality in the tissue sections (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney, Fig. 6A) were found in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs treatment group, but CuCl2, DSF/Cu complex and DSF@Cu-MOF groups demonstrated visible cardiotoxicity. Meanwhile, H&E stained images showed alveolar collapse except for DSF@HA/Cu-MOF group, probably due to the toxicity of Cu2+ and tumor invasion near lungs. Although Cu2+ also existed in DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, HA coating endued the NPs with superior biocompatibility, tumor-targeting ability and localized in-situ DSF/Cu complex formation within tumor cells. As a result, DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs prevented premature leakage of Cu2+ or DSF and non-targeting biodistribution in normal tissues compared with other groups. In addition, hematological and biochemical analysis of the serum (Fig. 6B and C), such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), blood urea nitrogen (UREA), and creatinine (CREA) at the end of antitumor studies showed negligible damage on renal and hepatic functions49. These results demonstrate that DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs with great tumor inhibition potency possessed excellent biosafety in vivo.

Figure 6.

In vivo biosafety evaluation of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF. (A) H&E staining of main organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney) at the end of therapeutic experiment, scale bar = 500 μm. (B) and(C) Levels of typical biochemical markers of the liver (B) and renal (C) function (n = 3).

4. Conclusions

In summary, we developed an in situ triggered DSF-loaded HA-modified Cu-MOF NPs for repurposing DSF in antitumor treatment. This system could preserve the stability of DSF and prevent the leakage of Cu ions in blood circulation, and simultaneously deliver both of them into tumor site. In the intracellular tumor microenvironment, DSF and Cu2+ was triggered to release from DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs and successfully achieve complexation in situ, leading to tumor cells death without affecting nearby normal cells. In vitro and in vivo studies confirmed the powerful antitumor potency of DSF@HA/Cu-MOF NPs, compared to DSF alone, which demonstrated no chemotherapeutic effects. Our work provides a promising strategy of chelation-initiated toxic complex generation in specific local site for elevated DSF-based anticancer treatment with reduced side effects.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972893), Key Program for Basic Research of Universities in Henan province (19zx005, China), Chinese Postdoctoral Funding Association (2018M640686 and 2019T120651, China), Youth talent promotion project in Henan province (2019HYTP017, China), Training program for young key teachers in Henan Province (2020GGJS019, China).

Author contributions

Lin Hou and Huijuan Zhang designed the research and wrote the manuscript. Lin Hou and Yanlong Liu carried out the experiments and performed data analysis. Wei Liu and Hongling Zhang participated part of the experiments. Mervat Balash provided experimental drugs and quality control. Yi Zhang and Zhenzhong Zhang conducted the experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.01.013.

Contributor Information

Yi Zhang, Email: yizhang@zzu.edu.cn.

Huijuan Zhang, Email: zhanghuijuan4@163.com.

Zhenzhong Zhang, Email: zhangzz_pharm@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cha J.H., Yang W.H., Xia W.Y., Wei Y.K., Chan L.C., Lim S.O. Metformin promotes antitumor immunity via endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation of PD-L1. Mol Cell. 2018;71:606–620. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai X.Y., Yan J., Fu X.H., Pan Q.M., Sun D.N., Xu Y. Aspirin inhibits cancer metastasis and angiogenesis via targeting heparanase. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6267–6278. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekino N., Kano M., Matsumoto Y., Sakata H., Akutsu Y., Hanari N. Antitumor effects of metformin are a result of inhibiting nuclear factor kappa B nuclear translocation in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:1066–1074. doi: 10.1111/cas.13523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun D.N., Liu H.C., Dai X.Y., Zheng X.L., Yan J., Wei R.R. Aspirin disrupts the mTOR-Raptor complex and potentiates the anti-cancer activities of sorafenib viamTORC1 inhibition. Cancer Lett. 2017;406:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bista R., Lee D.W., Pepper O.B., Azorsa D.O., Arceci R.J., Aleem E. Disulfiram overcomes bortezomib and cytarabine resistance in down-syndrome-associated acute myeloid leukemia cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:22–35. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0493-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu W.C., Yu L.D., Jiang Q.Z., Huo M.F., Lin H., Wang L.Y. Enhanced tumor-specific disulfiram chemotherapy by in situ Cu2+ chelation-initiated nontoxicity-to-toxicity transition. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:11531–11539. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b03503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y., Wang L.H., Zhang H.T., Wang Y.T., Liu S., Zhou W.L. Disulfiram combined with copper inhibits metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma through the NF-kappaB and TGF-beta pathways. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:439–451. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMahon A., Chen W., Li F. Old wine in new bottles: advanced drug delivery systems for disulfiram-based cancer therapy. J Control Release. 2020;319:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majera D., Skrott Z., Chroma K., Merchut-Maya J.M., Mistrik M., Bartek J. Targeting the NPL4 adaptor of p97/VCP segregate by disulfiram as an emerging cancer vulnerability evokes replication stress and DNA damage while silencing the ATR pathway. Cells. 2020;9:469–486. doi: 10.3390/cells9020469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng X.Y., Pan Q.Q., Zhang B.Y., Wan S.Y., Li S., Luo K. Highly Stable, coordinated polymeric nanoparticles loading copper(II) diethyldithiocarbamate for combinational chemo/chemodynamic therapy of cancer. Biomacromolecules. 2019;20:2372–2383. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.9b00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skrott Z., Mistrik M., Andersen K.K., Friis S., Majera D., Gursky J. Alcohol-abuse drug disulfiram targets cancer via p97 segregate adaptor NPL4. Nature. 2017;552:194–199. doi: 10.1038/nature25016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou L.L., Yang L., Yang C.L., Liu Y., Chen Q.Y., Pan W.L. Membrane loaded copper oleate PEGylated liposome combined with disulfiram for improving synergistic antitumor effect in vivo. Pharm Res. 2018;35:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s11095-018-2414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhuo X.Z., Lei T., Miao L.L., Chu W., Li X.W., Luo L.F. Disulfiram-loaded mixed nanoparticles with high drug-loading and plasma stability by reducing the core crystallinity for intravenous delivery. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;529:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L., Jiang Y., Jing G.H., Tang Y.L., Chen X., Yang D. A novel UPLC‒ESI-MS/MS method for the quantitation of disulfiram, its role in stabilized plasma and its application. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;937:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He H.C., Markoutsa E., Li J., Xu P.S. Repurposing disulfiram for cancer therapy viatargeted nanotechnology through enhanced tumor mass penetration and disassembly. Acta Biomater. 2018;68:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vahed T.A., Naimi-Jamal M.R., Panahi L. Alginate-coated ZIF-8 metal-organic framework as a green and bioactive platform for controlled drug release. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019;49:570–576. [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Y.Z., Zhang W., Guo T., Zhang G., Qin W., Zhang L. Drug nanoclusters formed in confined nano-cages of CD-MOF: dramatic enhancement of solubility and bioavailability of azilsartan. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lian X.Z., Huang Y.Y., Zhu Y.Y., Fang Y., Zhao R., Joseph E. Enzyme-MOF nanoreactor activates nontoxic paracetamol for cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57:5725–5730. doi: 10.1002/anie.201801378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan S.S., Cheng Q., Zeng X., Zhang X.Z. A Mn(III)-sealed metal-organic framework nanosystem for redox-unlocked tumor theranostics. ACS Nano. 2019;13:6561–6571. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b00300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S.X., Wang K.K., Shi Y.J., Cui Y.N., Chen B.L., He B. Novel biological functions of ZIF-NP as a delivery vehicle: high pulmonary accumulation, favorable biocompatibility, and improved therapeutic outcome. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26:2715–2727. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min H., Wang J., Qi Y.Q., Zhang Y.L., Han X.X., Xu Y. Biomimetic metal-organic framework nanoparticles for cooperative combination of antiangiogenesis and photodynamic therapy for enhanced efficacy. Adv Mater. 2019;31 doi: 10.1002/adma.201808200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng H.Q., Zhang Y.N., Liu L.F., Wan W., Guo P., Nystrom A.M. One-pot synthesis of metal-organic frameworks with encapsulated target molecules and their applications for controlled drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:962–968. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang D.D., Wu H.H., Zhou J.J., Xu P.P., Wang C.L., Shi R.H. In situ one-pot synthesis of MOF-polydopamine hybrid nanogels with enhanced photothermal effect for targeted cancer therapy. Adv Sci. 2018;5:1800287. doi: 10.1002/advs.201800287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X.R., Shi Z.Q., Tong R.L., Ding S.P., Wang X., Wu J. Derivative of epigallocatechin-3-gallatea encapsulated in ZIF-8 with polyethylene glycol–folic acid modification for target and pH-responsive drug release in anticancer research. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4:4183–4192. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L., Wan S.S., Li C.X., Xu L., Cheng H., Zhang X.Z. An adenosine triphosphate-responsive autocatalytic fenton nanoparticle for tumor ablation with self-supplied H2O2 and acceleration of Fe(III)/Fe(II) conversion. Nano Lett. 2018;18:7609–7618. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao Z.G., Zhang B.H., Liang T.X.Z., Ding J., Min Q.H., Zhu J.J. Promoting oxidative stress in cancer starvation therapy by site-specific startup of hyaluronic acid-enveloped dual-catalytic nanoreactors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:18995805. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b06034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amorim S., Costa D.S., Freitas D., Reis C.A., Reis R.L., Pashkuleva I. Molecular weight of surface immobilized hyaluronic acid influences CD44-mediated binding of gastric cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16058. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34445-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y.Q., Zheng Y.T., Lai X.Y., Chu Y.H., Chen Y.M. Biocompatible surface modification of nano-scale zeolitic imidazolate frameworks for enhanced drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2018;8:23623–23628. doi: 10.1039/c8ra03616k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X.Q., Cai S.S., He Y.M., Zhang M., Cao J., Mei H. Enzyme-triggered deshielding of nanoparticles and positive-charge mediated lysosomal escape for chemo/photo-combination therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7:4758–4762. doi: 10.1039/c9tb00685k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Fu S.Y., Wang L.H., Wang F.Y., Wang N.N., Cao Q. Copper improves the anti-angiogenic activity of disulfiram through the EGFR/Src/VEGF pathway in gliomas. Cancer Lett. 2015;369:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu B., Wang S.Y., Li R.W., Chen K., He L.L., Deng M.M. Disulfiram/copper selectively eradicates AML leukemia stem cells in vitro and in vivo by simultaneous induction of ROS-JNK and inhibition of NF-kappaB and Nrf 2. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2797. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y.P., Zhang K.F., Wang Y.W., Li M.G., Sun X.X., Liang Z.H. Disulfiram chelated with copper promotes apoptosis in human breast cancer cells by impairing the mitochondria functions. Scanning. 2016;38:825–836. doi: 10.1002/sca.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falls-Hubert K.C., Butler A.L., Gui K., Anderson M., Li M., Stolwijk J.M. Disulfiram causes selective hypoxic cancer cell toxicity and radio-chemo-sensitization viaredox cycling of copper. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;150:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.01.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang D.S., Zhang W.J., Wang A.T., Su H.T., Zhong H.J., Qi X.R. Treating metastatic triple negative breast cancer with CD44/neuropilin dual molecular targets of multifunctional nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2017;137:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y.S., Zhao Y., Lan J.S., Kang Y.N., Zhang T., Ding Y. Reduction-sensitive CD44 receptor-targeted hyaluronic acid derivative micelles for doxorubicin delivery. Int J Nanomed. 2018;13:4361–4378. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S165359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skandalis S.S., Gialeli C., Theocharis A.D., Karamanos N.K. Advances and advantages of nanomedicine in the pharmacological targeting of hyaluronan-CD44 interactions and signaling in cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2014;123:277–317. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800092-2.00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song L., Pan Z., Zhang H.B., Li Y.X., Zhang Y.Y., Lin J.Y. Dually folate/CD44 receptor-targeted self-assembled hyaluronic acid nanoparticles for dual-drug delivery and combination cancer therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:6835–6846. doi: 10.1039/c7tb01548h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun C.Y., Zhang B.B., Zhou J.Y. Light-activated drug release from a hyaluronic acid targeted nanoconjugate for cancer therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7:4843–4853. doi: 10.1039/c9tb01115c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wickens J.M., Alsaab H.O., Kesharwani P., Bhise K., Amin M.C.I.M., Tekade R.K. Recent advances in hyaluronic acid-decorated nanocarriers for targeted cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22:665–680. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X.D., He F., Xiang K.Q., Zhang J.J., Xu M.Z., Long P.P. CD44-targeted facile enzymatic activatable chitosan nanoparticles for efficient antitumor therapy and reversal of multidrug resistance. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:883–895. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen T.T., Yi J.T., Zhao Y.Y., Chu X. Biomineralized metal-organic framework nanoparticles enable intracellular delivery and endo-lysosomal release of native active proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:9912–9920. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b04457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan F., Feng X.C., Yang X.J., Sun W.T., Jin Y., Liu H.F. A simple and powerful co-delivery system based on pH-responsive metal-organic frameworks for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2017;122:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pack D.W., Putnam D., Langer R. Design of imidazole-containing endosomolytic biopolymers for gene delivery. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;67:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ren S.Z., Zhu D., Zhu X.H., Wang B., Yang Y.S., Sun W.X. Nanoscale metal-organic-frameworks coated by biodegradable organosilica for pH and redox dual responsive drug release and high-performance anticancer therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:20678–20688. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b04236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong K., Wang Z.Z., Zhang Y., Ren J., Qu X.G. Metal-organic framework-based nanoplatform for intracellular environment-responsive endo/lysosomal escape and enhanced cancer therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:31998–32005. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b11972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen W., Yang W., Chen P.Y., Huang Y.Z., Li F. Disulfiram copper nanoparticles prepared with a stabilized metal ion ligand complex method for treating drug-resistant prostate cancers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:41118–41128. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b14940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghimire S., McCarthy P.C. Capture of Pb2+ and Cu2+ metal cations by neisseria meningitidis-type capsular polysaccharides. Biomolecules. 2018;8:23–31. doi: 10.3390/biom8020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y., Zhao H.J., Yang X., Mu M.Y., Zong H., Luo L. Excessive Cu2+ deteriorates arsenite-induced apoptosis in chicken brain and resulting in immunosuppression, not in homeostasis. Chemosphere. 2020;239:124758. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hou L., Yan Y.S., Tian C.Y., Huang Q.X., Fu X.J., Zhang Z. Single-dose in situ storage for intensifying anticancer efficacy viacombinatorial strategy. J Control Release. 2020;319:438–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.