Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to evaluate self-care practices, sociodemographic and clinical factors that affect self-care and patient education among women with breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL).

Patients and methods

This descriptive, cross-sectional study included a total of 102 women with BCRL (median age: 59 years; range, 35 to 80 years) who received lymphedema (LE) treatment at least once between July 2014 and May 2016. A Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics Form and the Lymphedema Self-care Survey were used to collect data via face-to-face interviews.

Results

The median LE self-care practices score for women was 10 (range, 5 to 14). A total of 39.1% of the women implemented regular self-care. A statistically significant relationship was found between the score for perceived benefit of LE self-care and the score for self-care practice. No statistically significant difference was found among the self-care scores of the women with LE in terms of sociodemographic and clinical factors, except for education status. A total of 90.2% of the women with LE received self-care education, mostly from a physical therapy specialist and a physiotherapist. There was a statistically significant difference among self-care scores between patients who were educated and uneducated about LE.

Conclusion

It is recommended that healthcare professionals should educate patients diagnosed with breast cancer to reduce LE risk and promote the implementation of self-care practices following the breast cancer surgery. Interventions should be made to increase the perceived benefits and reduce the perceived barriers and burden towards self-care behaviors to prevent and manage LE.

Keywords: Breast cancer, education of patient lymphedema, self-care

Introduction

Breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) is a potential side effect of breast cancer treatment characterized by swelling of the arm, shoulder, hand, breast, and trunk on the same side as the breast cancer treatment.[1] The overall incidence of lymphedema (LE) ranges from 6 to 56% at two years of follow-up.[2-6] Although LE can be managed with effective treatment, there is still no cure.[7] Complete decongestive therapy is a primary evidence-based treatment for LE that involves six components, namely manual lymphatic drainage, multi-layer compression bandaging, compression garments, exercise, skin care, and self-care practices. Complete decongestive therapy consists of two steps that involve intense decongestive treatment and self-care of the patient.[7,8]

Patients should take lifelong responsibility for their self-care, irrespective of the type of the volume reduction LE treatment. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines self-care as “the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a healthcare provider”.[9] Healthcare professionals cannot provide and maintain social health alone. Maintenance of social health can be achieved, if people are assisted with individual-specific self-care activities. Therefore, self-care is important in chronic diseases such as LE.[10] Lymphedema self-care in patients involves manual lymphatic drainage, skin care, exercising, wearing compression garments, weight control, self-observation, and preventing and managing infections.[11,12]

Self-care education is important for women with BCRL. A study reported that most of women received self-care education during the LE treatment, and 65% of them thought it was adequate, but 29% did not.[11] In the same study, most of the patients reported LE therapists and physicians as an education resource. Lymphedema management requires a multidisciplinary team approach involving physical therapy specialists, physiotherapists, and nurses specialized in this area.[11]

The number of studies on self-care practices is limited,[11,13,14] and no study has been conducted on the self-care practices of women with LE in Turkey, yet. In the present study, therefore, we, for the first time, aimed to evaluate self-care practices, sociodemographic and clinical factors that affect self-care, and patient education among women with BCRL which would guide future studies and provide a basis for interventional studies. In addition, we aimed to investigate whether there was a relationship between the self-care perception and the self-care practice of women with BCRL and whether there was a difference between the score of self-care practices of women with BCRL who received and did not receive self-care education?

Patients and Methods

This descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted at the LE outpatient clinic of Ege University, Faculty of Medicine located in the western Turkey between July 2014 and May 2016. In our center, a physician and a nurse are available and patients diagnosed with LE receive education from the nurses. A total of 102 women with BCRL (median age: 59 years; range, 35 to 80 years) who received LE treatment at least once, were aged ≥20 years, and completed breast cancer treatment at least six months ago were included. Those who were still under breast cancer treatment and LE treatment-naïve patients were excluded from the study. A written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The study protocol was approved by the Dokuz Eylül University Non-Interventional Researchs Ethics Committee (Approval no. 1893-GOA/2015/14-38). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

A Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics Form and the Lymphedema Self-care Survey were used to collect data.

The Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics Form was developed by the researchers and consisted of 15 questions. The sociodemographic characteristics part includes seven questions, such as patient age, educational status, profession, and social security. The clinical characteristics part includes eight questions regarding chronic diseases, stage at breast cancer diagnosis, treatment after diagnosis, time after LE diagnosis, and LE-affected body part.

The Lymphedema Self-care Survey was developed based on the literature and Ridner’s Lymphedema Self-care Survey, consisting two sections.[11,15-20] Section A includes eight multiple-choice questions and one open-ended question on LE self-care practices. The first question includes 15 items regarding LE self-care practices implemented within the last 24 h. These items are answered by marking “Yes” (1 point) or “No” (0 point), and the Item 13 and Item 15 are scored in reverse. The total is calculated to give an LE self-care score, with the highest score is 15, and the lowest 0. Higher scores are associated with better self-care practices. The second question assessing the perceived benefits of doing LE self-care practices is scored from 0 (not useful) to 10 (very useful). Also, Section A includes multiple-choice questions related to maintaining self-care practices regularly, reasons not to implement self-care regularly, receiving assistance for self-care practices, time spent on self-care, the easiest and the hardest parts of self-care practices, and self-care enablers. Section B consists of two questions asking patients whether they received LE self-care education and who gave it, if the answer is “Yes”.

After the initial development of the survey, four healthcare professionals specialized in LE, including a physician, a nurse, and a physiotherapist were asked for their opinions and necessary changes were made accordingly. A pilot study was carried out with 10 individuals who met the sampling criteria. No changes were made to the survey, as there were no suggestions following the pilot study. Patients that participated in the pilot study were not included in the sample.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS version 20.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data were expressed in median (min-max) or number and frequency. The normality of the test was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk’s test. The test result showed that the data set did not meet the normality assumption.[21] The difference between the groups in terms of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics according to the scores of LE self-care was evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests. After the Kruskal-Wallis test, as an advance analysis, the Mann-Whitney U test with the Bonferroni correction was used to examine which group caused significance. The Pearson correlation analysis was used to measure the correlation between LE self-care score and perception of benefit of LE self-care practices. A p value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of all participants, 38% (n=39) were university graduates, 46.1% (n=47) were housewives, 73.5% (n=75) were married, 33.3% (n=34) had children to take care of, 43.1% (n=44) had chronic diseases, and 66.7% (n=68) had LE only on one arm. The median time after diagnosis of LE was 31 (range, 5 to 180) months (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of sociodemographic and clinical variables.

| Characteristics | n | % | Median | Min-Max |

| Age (year) | 59.0 | 35-80 | ||

| Education status | ||||

| Literate | 8 | 7.80 | ||

| Primary education | 36 | 35.30 | ||

| High school | 19 | 18.60 | ||

| At least university graduate | 39 | 38.30 | ||

| Profession | ||||

| Housewife | 47 | 46.10 | ||

| Retired | 21 | 20.60 | ||

| Public servant | 13 | 12.70 | ||

| Other | 21 | 20.60 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 34 | 33.30 | ||

| Unemployed | 68 | 66.70 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 75 | 73.50 | ||

| Single | 27 | 26.50 | ||

| Average income level | ||||

| Income and expenses are equal | 52 | 51.00 | ||

| Income is less than expenses | 36 | 35.30 | ||

| Income is higher than expenses | 14 | 13.70 | ||

| Have children to take care of | ||||

| No | 68 | 66.70 | ||

| Yes | 34 | 33.30 | ||

| Any other chronic diseases | ||||

| No | 58 | 56.90 | ||

| Yes | 44 | 43.10 | ||

| Chronic diseases | ||||

| Hypertension | 11 | 10.80 | ||

| Hypothyroid | 11 | 10.80 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 | 5.80 | ||

| Osteoporosis | 6 | 5.80 | ||

| Other | 10 | 9.90 | ||

| Stage at breast cancer diagnosis | ||||

| Stage 1 | 13 | 12.70 | ||

| Stage 2 | 50 | 49.00 | ||

| Stage 3 | 36 | 35.40 | ||

| Stage 4 | 3 | 2.90 | ||

| Treatment after diagnosis with breast cancer | ||||

| in addition to surgery and chemotherapy | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 95 | 93.13 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 57 | 55.88 | ||

| Targeted therapy | 13 | 12.70 | ||

| Type of surgery for breast cancer | ||||

| Breast-conserving surgery (lumpectomy) | 37 | 36.30 | ||

| Total mastectomy | 33 | 32.30 | ||

| Modified radical mastectomy | 32 | 31.40 | ||

| Lymphedema affected body part | ||||

| An arm | 68 | 66.70 | ||

| A hand and an arm | 22 | 21.60 | ||

| A hand | 9 | 8.70 | ||

| Both arms | 2 | 2.00 | ||

| Both hands | 1 | 1.00 | ||

| Min: Minimum; Max: Maximum. | ||||

All women kept their arms clean, 92.2% (n=94) protected their arms from any cuts, and 89.2% (n=91) observed their arms for any injuries and changes. The median score for LE self-care practices was 10 (range, 5 to 14) out of 15, in which 39.2% (n=40) reported that they implemented self-care practices regularly (Table 2).

Table 2. The distribution of self-care practices and reasons not to implement regular self-care for women with BCRL (n=102).

| Yes | No | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Self-care practices | ||||||

| Engage in regular self-care practices | 40 | 39.2 | 62 | 60.8 | ||

| Keep the arm clean | 102 | 100.0 | 0 | 00.0 | ||

| Apply moisturizing products (lotion, cream, and spray, etc.) | 59 | 58.7 | 43 | 42.2 | ||

| Wear gloves while doing housework or gardening | 39 | 38.2 | 63 | 61.8 | ||

| Wear compression garments during the day | 42 | 41.2 | 60 | 58.8 | ||

| Protect the skin from the sun by wearing a high factor sun cream | 32 | 31.4 | 70 | 68.6 | ||

| Avoid injuries or cuts | 94 | 92.2 | 8 | 7.8 | ||

| Avoid lifting or carrying heavy objects | 81 | 79.4 | 21 | 20.6 | ||

| Do daily arm exercises | 75 | 73.5 | 27 | 26.5 | ||

| Apply manual lymphatic drainage massage | 32 | 31.4 | 70 | 68.6 | ||

| Follow scars or changes on the affected arm | 91 | 89.2 | 11 | 10.8 | ||

| Watch their diet | 59 | 58.7 | 43 | 42.2 | ||

| Do not wear tight clothing | 88 | 86.3 | 14 | 13.7 | ||

| Do not use bandaging at night | 99 | 97.1 | 3 | 2.9 | ||

| Measure arm circumference | 15 | 14.7 | 87 | 85.3 | ||

| Do not implement any self-care practices | 0 | 00.0 | 102 | 100.0 | ||

| Engage in regular self-care practices | 40 | 39.2 | 62 | 60.8 | ||

| n | % | |||||

| Reasons not to implement regular self-care (n=62) | ||||||

| Fatigue | 22 | 35.5 | ||||

| There is nobody to help | 19 | 30.6 | ||||

| Do not want to do anything | 17 | 27.4 | ||||

| Lack of time | 12 | 19.4 | ||||

| Do not know how to care for the affected arm | 9 | 14.5 | ||||

| Do not believe in benefits of self-care | 8 | 12.9 | ||||

| Limited mobility owing to lymphedema | 7 | 11.3 | ||||

| Forgetting or feeling lazy | 6 | 9.7 | ||||

| Have another disease | 2 | 3.2 | ||||

| BCRL: Breast cancer-related lymphedema. | ||||||

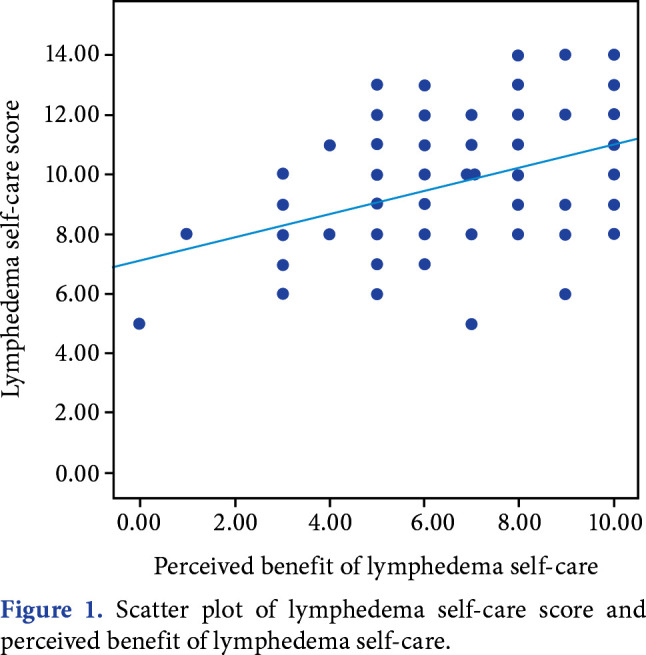

The median score for the perceived benefits of doing self-care behaviors was 7 (range, 0 to 10) out of 10. A statistically significant moderate positive relationship was found between the scores for perceived benefits of LE self-care and self-care practice (r=0.408; p=0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scatter plot of lymphedema self-care score and perceived benefit of lymphedema self-care.

Half of the women (52%, n=53) did not receive any help during LE self-care practices, 26.5% (n=27) of them received help from a family member, and 21.5% (n=22) of them from her husband. Of the women who received help, 34.7% (n=17) were reminded to do their exercises and 28.4% (n=14) received help with wearing compression garments. Of the women who did not receive any help during LE self-care practices, 52.8% (n=28) reported that any support would make self-care easier. The median time per day spent on self-care was found 20 (range, 5 to 60) min. A total of 41.2% (n=42) of the women reported avoiding sleeping on the affected side, and 18.6% (n=19) reported that wearing compression garments, 17.6% (n=18) reported that preventing affected arm from injury, 11.8% (n=12) reported that doing arm exercises, 5.9% (n=6) reported compression bandage application, and 4.9% (n=5) manual lymphatic drainage were the most difficult parts of LE self-care. According to the patients, the easiest LE self-care practices were respectively keeping the arm clean (62.7%, n=64), moisturizing the skin (19.6%, n=20), the arm exercises (11.8%, n=12), protection of the arm (3%, n=3), and wear compression garment (3%, n=3). Women reported that self-care became easier, when someone helped with the housework (48%, n=49), received self-care education (23.5%, n=24), and they had someone to remind them to self-care regularly (22.5%, n=23), while 4.9% (n=5) of women reported that there was no need for any facilitator.

No statistically significant difference was found among the scores of LE self-care practices according to age groups, having children to take care of, the existence of any chronic diseases, employment status, marital status, and LE-affected body part (p>0.05). A statistically significant difference was found among the scores of LE self-care practices in terms of educational status, which through advance analysis was associated with the literate group (z(1-2)=-2.089, p(1-2)=0.037; z(1-3)=-2.541, p(1-3)=0.011; z(1-4)=-2.827, p(1-4)=0.005), suggesting that the self-care score of this group was lower than other groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of scores of lymphedema self-care practices according to selected sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (n=102).

| Characteristics | n | % | Median | Min-Max | Test | p |

| Age (year) | 0.486* | 0.627 | ||||

| <65 | 70 | 68.6 | 10 | 6-14 | ||

| >65 | 32 | 31.4 | 10 | 5-14 | ||

| Educational status | 8.116** | 0.041 | ||||

| Literate | 8 | 7.8 | 8 | 5-12 | ||

| Primary education | 36 | 35.3 | 10 | 6-13 | ||

| High school | 19 | 18.6 | 10 | 5-14 | ||

| College degree or more | 39 | 38.3 | 10 | 7-14 | ||

| Employment status | 1.116* | 0.776 | ||||

| Employed | 34 | 33.3 | 10 | 6-13 | ||

| Unemployed | 68 | 66.7 | 10 | 6-14 | ||

| Marital status | 1.049* | 0.423 | ||||

| Married | 75 | 73.5 | 10 | 5-14 | ||

| Single | 27 | 26.5 | 10 | 6-14 | ||

| Have children to take care of | 1.039* | 0.402 | ||||

| No | 68 | 66.7 | 10 | 7-14 | ||

| Yes | 34 | 33.3 | 10 | 5-14 | ||

| Chronic disease | 1.149* | 0.163 | ||||

| No | 58 | 56.9 | 9 | 6-14 | ||

| Yes | 44 | 43.1 | 10 | 5-14 | ||

| Lymphedema affected body part | 3.883** | 0.144 | ||||

| An arm | 68 | 66.7 | 10 | 5-14 | ||

| A hand and an arm | 24 | 23.6 | 9 | 7-14 | ||

| A hand | 10 | 9.7 | 11 | 8-14 | ||

| Min: Minimum; Max: Maximum; t: Independent groups t-test; Z: Mann-Whitney U test; KW: Kruskall-Wallis test. | ||||||

Of all the women, 90.2% (n=92) received LE self-care education, 63.8% (n=65) of whom received that education after the occurrence of LE. The LE self-care education sources of women were mainly physical therapy specialist (91.3%, n=84) and physiotherapist (67.4%, n=62). Women who received LE self-care education had higher LE self-care scores than women who did not (p=0.031). No significant difference was found among the LE self-care practice scores in terms of the period of receiving self-care education (Table 4).

Table 4. Distribution of self-care education of women with lymphedema (n=102).

| Characteristics | n | % | Median | Min-Max | Test | p |

| Received self-care education | -2.018 | 0.031 | ||||

| Yes | 92 | 90.2 | 10 | 5-14 | ||

| No | 10 | 9.8 | 8 | 5-12 | ||

| Period of self-care education | -.274 | 0.780 | ||||

| Before the onset of lymphedema | 27 | 26.4 | 10 | 5-14 | ||

| After the onset of lymphedema | 65 | 63.8 | 10 | 6-14 | ||

| Education sources (after breast cancer surgery) | ||||||

| Physical therapy specialist | 84 | 91.3 | ||||

| Physiotherapist | 62 | 67.4 | ||||

| Surgeon | 25 | 27.2 | ||||

| Nurse | 13 | 14.1 | ||||

| Medical oncologist | 5 | 5.4 | ||||

| Min: Minimum; Max: Maximum; Z: Mann-Whitney U test. | ||||||

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated self-care practices, sociodemographic and clinical factors affecting self-care, and patient education among women with BCRL. The study findings can be discussed in three categories: LE self-care practices; sociodemographic and clinical factors that affect LE self-care; and LE self-care education.

Less than half of the women with BRCL wore the compression garments, while 79% and 76% of the women with BRCL reported wearing compression garments in two previous studies.[11,14] This low ratio in our study may be associated with the data collection time, as it is very unpleasant to wear compression garments in high temperatures during the summer months. In our study, 73.5% of the women exercised, compared to 58%[14] and 60%[11] in previous reports. This higher ratio could be to compensate for the lower use of compression garments for manual lymphatic drainage. In addition, compression garments for LE are not covered by social security and more than half of the women consider they are expensive. The rate of manual lymphatic drainage massage in our study is consistent with a previous study where 39% of the women were prescribed self-lymphatic drainage massage.[14]

In our study, the ratio of those who regularly cared for LE was 39.2%, whereas it was 69% in a similar study.[14] The most important, but difficult aspect of self-care is regular implementation, as it is affected by various factors such as culture, habits, motivation, and skills.[22] Women have a higher likelihood of engaging in poor self-care practices based on their traditional sex roles as wives, mothers, and homemakers.[15] In a United States study, reasons to not to implement self-care practices regularly were based on lack of information, fatigue, and not believing in the perceived benefits of self-care.[11] Similar to our findings, in a qualitative study, it was found that not having someone to help was one of the reasons for not implementing self-care practices regularly.[22,23] This result can be explained by the fact that non-working women stay home alone during the day.

In the current study, the perceived benefit of LE self-care was high and a medium-level positive significant relationship was found among perceived benefit of self-care and self-care practices. Similarly, in a qualitative study, it was found that beliefs of the benefits of self-care were helpful for the success of LE self-care.[13]

In a study, 35% of the women received help with LE self-care; 12% were assisted with massage, 9% were reminded to implement self-care practices and received emotional support.[11] In our study, most of the women who did not receive any help reported that any help would make self-care easier for them, in agreement with a qualitative study found that women lacked support with self-care.[23] Consistent with the literature, our findings suggest that emotional and social support in self-care are important in facilitating self-care.

Several studies have emphasized that women do not dedicate enough time to self-care practices, and time constraints are defined as one of the self-care barriers.[11,13,15,24] In our study, women did not spend enough time on self-care practices, as they prioritized caring for family members and doing housework and they did not have anybody to support them with self-care practices.

Self-care enablers were defined as having someone to do housework, receiving LE self-care education, and having someone to regularly remind about self-care practices. Repetitive motions in housework prevent the lymphatic flow. A study indicated that women did not prioritize self-care owing to housework and family responsibilities.[15] Therefore, having someone to do housework would make self-care practices easier.

In the present study, no statistically significant difference was found among the self-care scores of the women with LE in terms of age, marital status, existence of any chronic diseases, employment status, having children to take care of, or LE-affected body area. Different from our findings, a qualitative study determined that women could not prioritize their own needs and spare time away from their family, indicating that being married and having children negatively affect self-care.[15] Existence of chronic diseases and older age can cause the development and progression of LE.[25] Obsty and Armer’s[26] systematic review emphasized the existence of chronic diseases and older age as LE self-care barriers, unlike our findings. This difference could be associated with the respect and care for the elderly in Turkish culture. In our study, patients with a low education profile had a lower self-care score, compared to those with a high education profile. Similar to our findings, the literature suggests that individuals with a higher education profile implement self-care practices more often.[27,28]

In our study, most of the women received LE self-care education similar to another study in which 94% of the women received this education.[11] This high ratio is associated with the sampling criteria of receiving LE treatment at least once; however, 10% of the patients did not receive education. This result indicates that healthcare professionals do not provide sufficient education to prevent the occurrence of BCRL.

In our study, most of the women received education from a physical therapy specialist and a physiotherapist. Another study found that 39% of patients received self-care education from LE therapists. In another study conducted in Turkey in 46 nurses, 51.2% of LE education was provided by nurses and physicians in surgical clinics.[29] This result may be related to lack of knowledge of healthcare professionals about LE.

The self-care practices score of the patients who received LE self-care education was higher than for those who did not receive education. Similar to our findings, studies examining the adaptation to self-care practices indicate that having adequate information on self-care positively affects and enables adoption and maintenance of self-care.[13,24,26,30]

The limitation of this study was the lack of a reliable and valid assessment scale for assessing LE self-care.

In conclusion, our study examined self-care practices and education in women with BCRL and found that skin care was the most commonly applied LE self-care practice. The LE self-care practice score was higher in the women who received self-care education than those who did not receive, and the education was mostly given by a physical therapy specialist or physiotherapist. Based on these findings, we recommend for healthcare professionals to educate patients diagnosed with breast cancer to reduce LE risk and promote the implementation of self-care practices following the surgery and to periodically repeat education and interventions in LE outpatient clinics to increase self-care practices in long-term follow-ups.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Financial Disclosure: The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

References

- 1.Hamolsky D. Medical Surgical Nursing Assestment and Management of Clinical problems. 9. Canada: Mosby; 2014. Nursing Management Breast Disorders; pp. 1238–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Şimşir Atalay N, Taflan Selçuk S, Ercidoğan Ö, Akkaya N, Sarsan A, Yaren A, et al. Meme cerrahisi ve aksiller diseksiyon uygulanan meme kanserli hastalarda üst ekstremite problemlerinin sıklığı ve yaşam kalitesine etkisi. Türk Fiz Tıp Rehab Derg. 2011;57:186–192. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adriaenssens N, Verbelen H, Lievens P, Lamote J. Lymphedema of the operated and irradiated breast in breast cancer patients following breast conserving surgery and radiotherapy. Lymphology. 2012;45:154–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, Hayes S. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:500–515. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Instute (NCI) (2015) Lymphedema (PDQ®)-Health Professional Version [online]. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/ side-effects/lymphedema/lymphedema-hp-pdq#section/ all?redirect=true [Accessed: October, 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soyder A, Taştaban E, Özbaş S, Boylu Ş, Özgün H. Frequency of early-stage lymphedema and risk factors in postoperative patients with breast cancer. J Breast Health. 2014;10:92–97. doi: 10.5152/tjbh.2014.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasinski BB, McKillip Thrift K, Squire D, Austin MK, Smith KM, Wanchai A, et al. A systematic review of the evidence for complete decongestive therapy in the treatment of lymphedema from 2004 to 2011. PM R. 2012;4:580–601. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harmer V. Breast cancer-related lymphoedema: implications for primary care. Harmer V. Breast cancer-related lymphoedema: implications for primary care. Br J Community Nurs 2009;14:S15-6, 18-9. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2009.14.Sup5.44505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webber D, Guo Z, Mann S. Self-care in health: We can define it, but should we also measure it. SelfCare. 2013;4:101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Self-Medication Industry-WSMI (2010) The story of self-care and self-medication 40 years of progress, 1970-2010. France [online]. Available at: http://www.wsmi.org/wp-content/data/pdf/storyofselfcare_brochure.pdf. [Accessed: February, 2016]

- 11.Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Kidd N. Breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema self-care: education, practices, symptoms, and quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:631–637. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0870-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridner SH, Fu MR, Wanchai A, Stewart BR, Armer JM, Cormier JN. Self-management of lymphedema: a systematic review of the literature from 2004 to 2011. Nurs Res. 2012;61:291–299. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31824f82b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeffs E, Ream E, Shewbridge A, Cowan-Dickie S, Crawshaw D, Huit M, et al. Exploring patient perception of success and benefit in self-management of breast cancer-related arm lymphoedema. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown JC, Cheville AL, Tchou JC, Harris SR, Schmitz KH. Prescription and adherence to lymphedema self-care modalities among women with breast cancer-related lymphedema. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1962-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radina ME, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Making self-care a priority for women at risk of breast cancer-related lymphedema. J Fam Nurs. 2014;20:226–249. doi: 10.1177/1074840714520716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Best practıce for the management of lymphoedema. Available at: https://www.lympho.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Best_practice.pdf. [Accessed: May, 2018]

- 17.Güler Demir S. Meme kanseri nedeniyle ameliyat olan hastalarda kendi kendine lenfödem yönetimi. Meme Sağlığı Dergisi. 2008;4:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayrovitz HN. The standard of care for lymphedema: current concepts and physiological considerations. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7:101–108. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2009.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dine JL, Austin MK, Armer JM. Nursing education on lymphedema self-management and self-monitoring in a South African oncology clinic. J Cult Divers. 2011;18:126–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins W, Gilliam T. Lymphedema a selfcare guide. UNC Health Care-UNC Cancer Care. 2014 Available at: https://unclineberger.org/patientcare/support/ccsp/documents/2017lymphedemaselfcareguide_blackandwhite . [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 6th ed. Boston: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riegel B, Jaarsma T, Strömberg A. A middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2012;35:194–204. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e318261b1ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridner SH, Rhoten BA, Radina ME, Adair M, Bush-Foster S, Sinclair V. Breast cancer survivors' perspectives of critical lymphedema self-care support needs. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2743–2750. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridner SH, McMahon E, Dietrich MS, Hoy S. Home-based lymphedema treatment in patients with cancer-related lymphedema or noncancer-related lymphedema. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:671–680. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.671-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy D. Reducing the risk of upper limp lymphedema. Royal Collage of Nursing. London. 2011. Available at: https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-004138. [Accessed: February, 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostby PL, Armer JM. Complexities of adherence and post-cancer lymphedema management. J Pers Med. 2015;5:370–388. doi: 10.3390/jpm5040370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodríguez-Gázquez Mde L, Arredondo-Holguín E, Herrera-Cortés R. Effectiveness of an educational program in nursing in the self-care of patients with heart failure: randomized controlled trial. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2012;20:296–306. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692012000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasanpour-Dehkordi A. Self-care concept analysis in cancer patients: An evolutionary concept analysis. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:388–394. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.191753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gül A, Erdim L. Meme kanseri ameliyatından sonra lenfödemin önlenmesinde hemşirelerin eğitim yaklaşımı. Meme Sağlığı Dergisi. 2009;5:82–86. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherman KA, Koelmeyer L. Psychosocial predictors of adherence to lymphedema risk minimization guidelines among women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1120–1126. doi: 10.1002/pon.3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]